Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A systematic evaluation of multiple advanced ANN architectures for intrusion detection in IoMT environments, including standard feedforward networks, dual-branch models with addition and concatenation operations, and networks incorporating shortcut connections.

- Comprehensive assessment of autoencoder preprocessing for dimensionality reduction in intrusion detection, revealing critical trade-offs between feature compression and detection performance.

- Comparative analysis of three class imbalance mitigation strategies (SMOTE, weighted loss functions, and hybrid sampling) across different neural architectures, identifying optimal combinations for effective attack detection.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Machine Learning Approaches

2.2. Neural Network and Advanced Learning Approaches

2.3. IoMT-Specific Approaches

2.4. Research Gaps and Opportunities

- Most studies focus on either traditional machine learning or basic neural network structures, with limited exploration of advanced neural architectures specifically designed for healthcare intrusion detection.

- While class imbalance is acknowledged as a challenge, comprehensive comparisons of different balancing techniques and their impact on various neural network architectures are scarce.

- The interaction between dimensionality reduction techniques and different neural network designs remains underexplored, particularly in healthcare-specific contexts.

- The impact of feature normalization and channel number optimization on neural network performance for intrusion detection has received insufficient attention.

3. Methodology

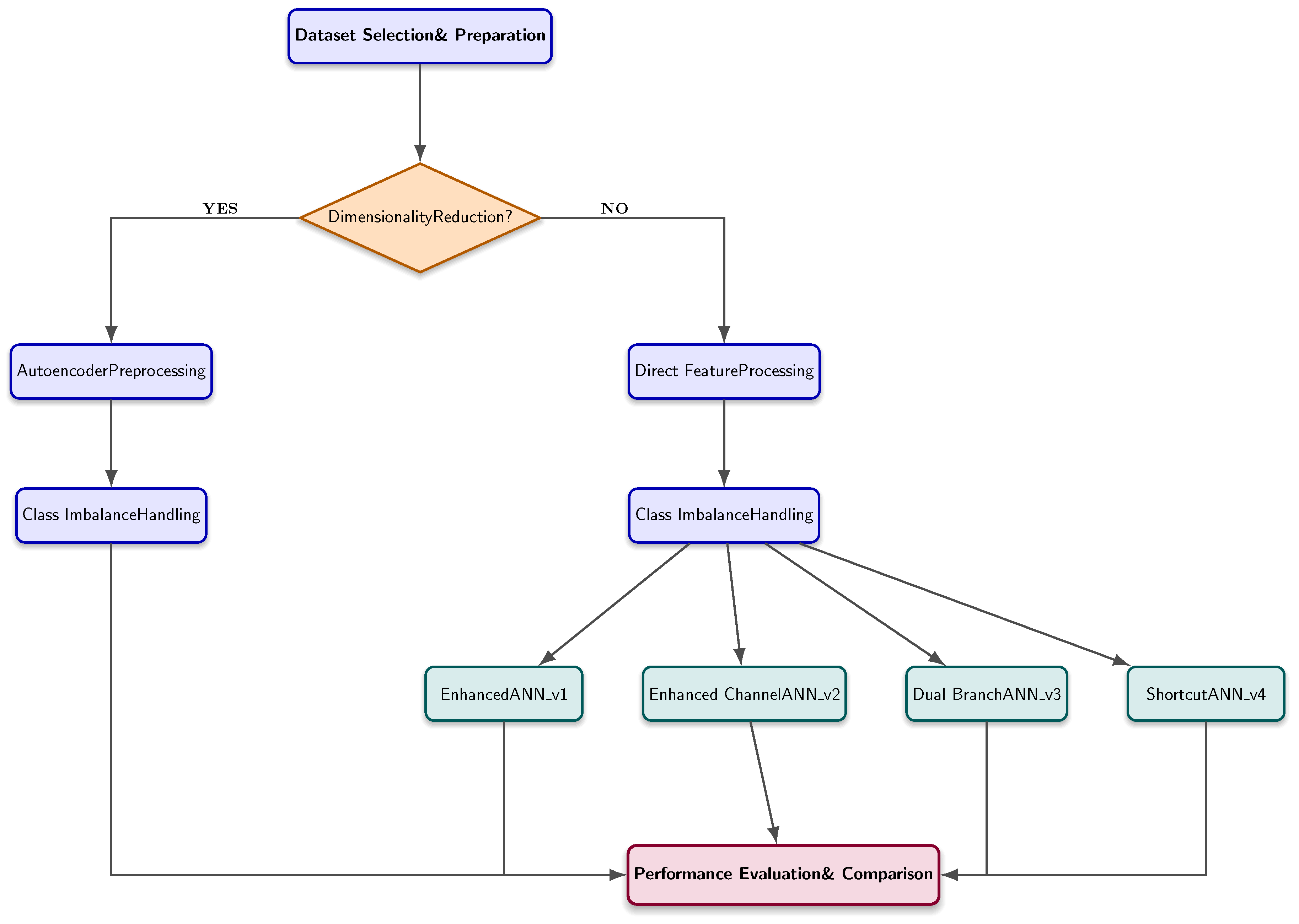

3.1. Research Design

- Dataset Selection and Preparation: We utilize the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset specifically designed for IoMT environments, performing initial cleaning and feature standardization.

-

Feature Processing: We implement two parallel processing paths:

- Direct Feature Processing: Original features are standardized and used directly for model training.

- Autoencoder Preprocessing: Features undergo dimensionality reduction through an autoencoder network before being fed to classification models.

-

Class Imbalance Handling: We implement and compare three distinct strategies:

- Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE)

- Weighted loss function approach

- Hybrid over-under sampling method

-

Neural Network Architecture Design: We implement five distinct ANN architectures:

- Standard ANN (baseline)

- Enhanced Channel ANN (ANN_v1)

- Dual-Branch Addition ANN (ANN_v2)

- Dual-Branch Concatenation ANN (ANN_v3)

- Shortcut Connection ANN (ANN_v4)

- Model Training and Validation: Each architecture is trained with consistent hyperparameters across multiple class balancing configurations, using evaluation at regular intervals to assess performance.

- Performance Evaluation: Models are evaluated using multiple metrics (AUC, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score) to provide a comprehensive assessment of their detection capabilities.

3.2. Dataset Description

- Spoofing attacks: Intercept communications between gateway and server, potentially exposing confidential patient information.

- Data injection attacks: Alter packets in transit, compromising data integrity.

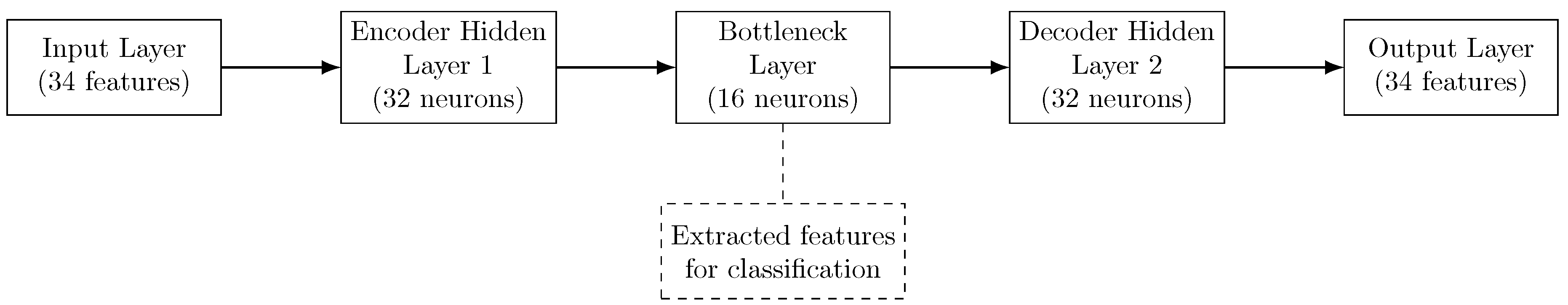

3.3. Autoencoder for Dimensionality Reduction

- Encoder: Compresses the 34-dimensional input features to a 16-dimensional bottleneck representation

- Decoder: Reconstructs the original 34-dimensional features from the bottleneck representation

3.4. Class Imbalance Strategies

3.4.1. Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE)

3.4.2. Hybrid Over-Under Sampling

3.4.3. Weighted Cross-Entropy Loss Function

3.5. Neural Network Architectures

3.5.1. Standard ANN (ANN)

- Input Layer: 34 features (most relevant network and biometric parameters)

- Hidden Layers: Seven fully-connected layers with dimensions [40, 40, 20, 10, 10, 10, 10]

- Output Layer: 2 neurons for binary classification

- Activation: ReLU for all hidden layers

3.5.2. Enhanced Channel ANN (ANN_v1)

- Input Layer: 34 features

- Hidden Layers: Seven fully-connected layers with dimensions [256, 256, 128, 64, 64, 64, 64]

- Output Layer: 2 neurons for binary classification

- Activation: ReLU for all hidden layers

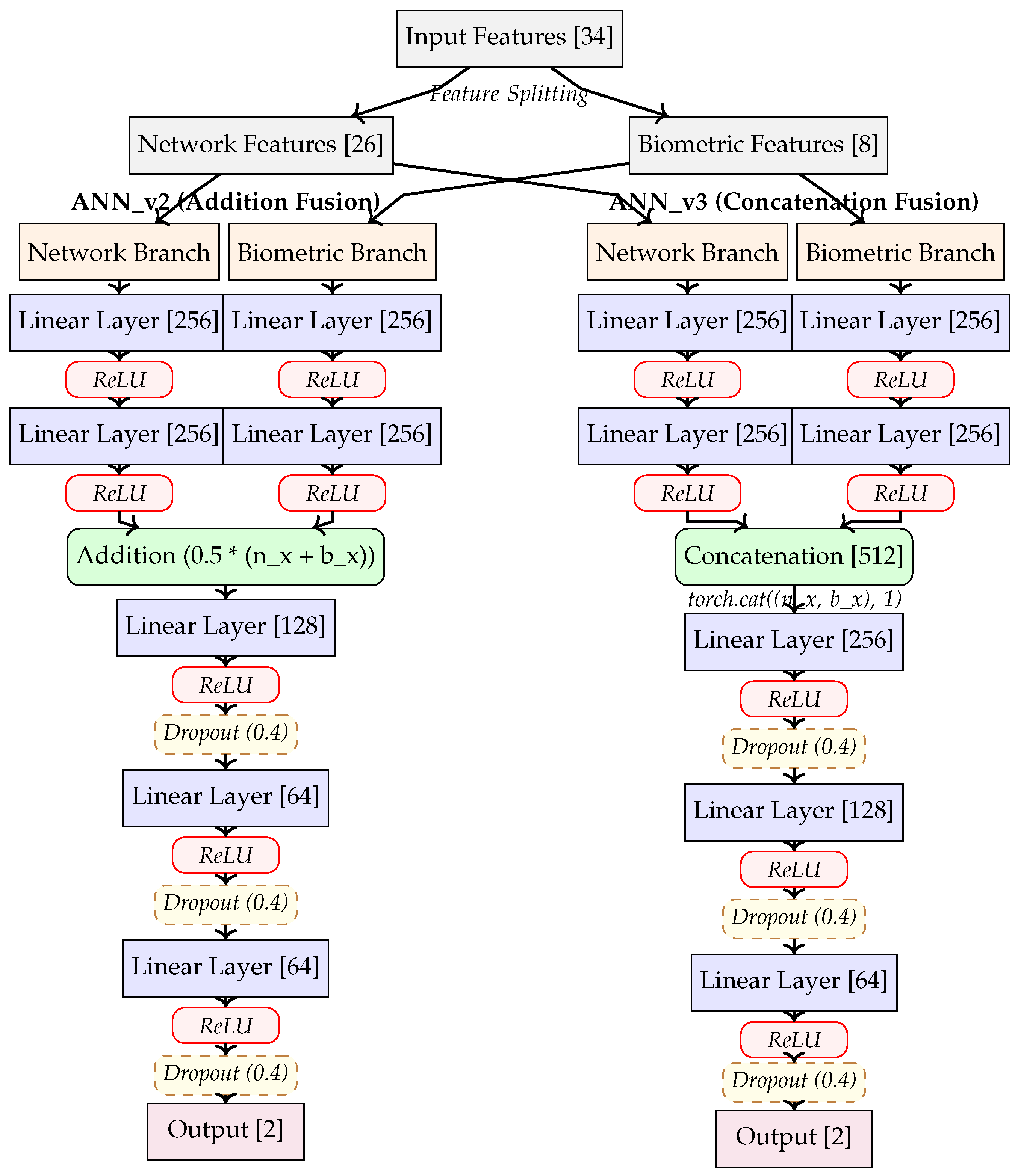

3.5.3. Dual-Branch Models (ANN_v2 and ANN_v3)

- Data Splitting: The 34-dimensional input is divided into network metrics (first 26 features) and biometric parameters (remaining 8 features)

- Specialized Processing: Each feature type is processed through dedicated network branches

- Different Fusion Mechanisms: The two models differ in how they combine branch outputs

Dual-Branch Addition ANN (ANN_v2)

- Network Branch: Two fully-connected layers [256, 256] with ReLU activation process the 26 network features

- Biometric Branch: Two fully-connected layers [256, 256] with ReLU activation process the 8 biometric features

- Fusion Mechanism: Element-wise addition of branch outputs multiplied by 0.5 (averaging operation)

- Shared Layers: Three layers [128, 64, 64] with ReLU activation and dropout (0.4)

- Output Layer: 2 neurons for binary classification

Dual-Branch Concatenation ANN (ANN_v3)

- Network Branch: Two fully-connected layers [256, 256] with ReLU activation process the 26 network features

- Biometric Branch: Two fully-connected layers [256, 256] with ReLU activation process the 8 biometric features

- Fusion Mechanism: Concatenation of branch outputs, resulting in a 512-dimensional feature vector

- Shared Layers: Three layers [256, 128, 64] with ReLU activation and dropout (0.4)

- Output Layer: 2 neurons for binary classification

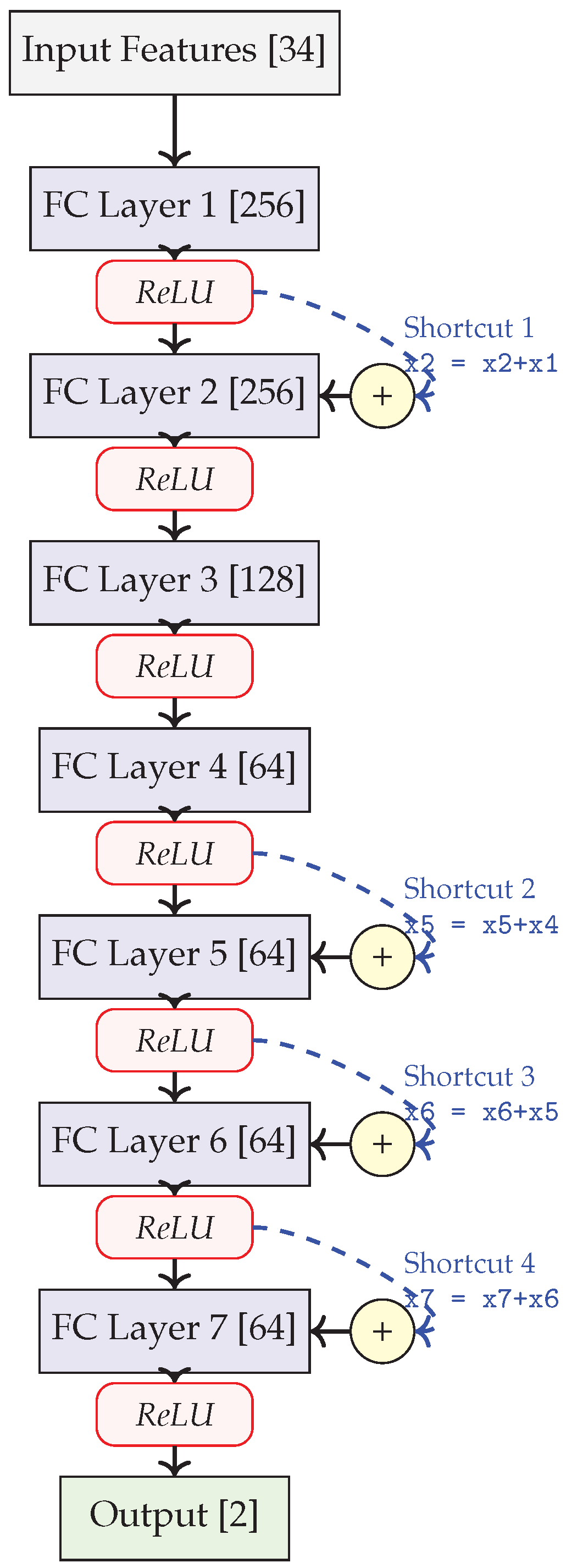

3.5.4. Shortcut Connection ANN (ANN_v4)

- Input Layer: 34 features (combined network and biometric parameters)

- Hidden Layers: Seven fully-connected layers with dimensions [256, 256, 128, 64, 64, 64, 64]

-

Shortcut Connections: Four identity shortcuts creating residual blocks

- −

- Layer 1 output added to Layer 2 output

- −

- Layer 4 output added to Layer 5 output

- −

- Layer 5 output (with previous shortcut) added to Layer 6 output

- −

- Layer 6 output (with previous shortcut) added to Layer 7 output

- Output Layer: 2 neurons for binary classification

- Activation: ReLU for all hidden layers

3.6. Training and Hyperparameter Settings

3.7. Evaluation Metrics

- Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC): Measures the model’s discrimination capability across all possible classification thresholds. AUC represents the probability that the classifier will rank a randomly chosen positive instance higher than a randomly chosen negative instance. Mathematically:where TPR is the true positive rate and FPR is the false positive rate at threshold t. AUC values range from 0.5 (random classification) to 1.0 (perfect classification). This metric is particularly valuable for imbalanced datasets as it is insensitive to class distribution.

-

Accuracy (ACC): The proportion of correctly classified instances among all instances:While intuitive, accuracy can be misleading in imbalanced datasets, as high accuracy can be achieved by simply classifying all instances as the majority class.

-

Precision (PR): The proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions:High precision indicates a low false positive rate, which is particularly important in intrusion detection systems where false alarms can lead to alert fatigue and reduced trust in the system.

-

Recall (RC): Also known as sensitivity or true positive rate, recall measures the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified:High recall indicates that the model successfully captures most attack instances, which is critical in security applications where missing an attack (false negative) can have severe consequences.

-

F1-score (F1): The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balance between these two potentially competing metrics:F1-score ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better performance. This metric is particularly useful when seeking a balance between precision and recall.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Impact of Neural Network Architecture

- Standard vs. Enhanced ANNs: The enhancement through increased channel numbers (ANN_v1) consistently improves performance, confirming that greater parametrization enables better feature learning for this task.

- Dual-Branch Architectures: The dual-branch models (ANN_v2 and ANN_v3) consistently achieve the highest performance across all balancing methods. The addition-based combination (ANN_v2) generally outperforms the concatenation approach (ANN_v3), suggesting that the summation of features from parallel branches provides more effective feature integration for intrusion detection.

- Shortcut Connections: The ANN_v4 model with shortcut connections shows comparable performance to ANN_v1, indicating that for this particular task and dataset size, shortcut connections do not provide substantial additional benefits over simply increasing channel numbers.

4.2. Effectiveness of Class Balancing Methods

- SMOTE: While SMOTE improves model performance compared to no balancing (not shown), it generally yields lower accuracy and precision compared to the other balancing methods. However, it maintains reasonably good recall, indicating its ability to identify attack instances.

- Hybrid Over-Under Sampling: This approach consistently outperforms SMOTE across all architectures, achieving better balance between precision and recall. The improved performance suggests that selective under-sampling of majority class instances combined with minority class duplication provides an effective balance for intrusion detection.

- Weighted Cross-entropy Loss Function: This method yields the highest overall performance, particularly when combined with the ANN_v2 architecture (0.9403 accuracy, 0.8716 F1-score). It demonstrates superior precision compared to other methods while maintaining competitive recall. This suggests that preserving the original data distribution while adjusting the learning objective is most effective for this task.

4.3. Impact of Dimensionality Reduction

- With SMOTE, the AE+ANN_v4 model achieves the highest precision (0.9383) among all SMOTE-based models, but with significantly lower recall (0.7485) compared to other ANN architectures.

- With the weighted cross-entropy loss function, the AE+ANN_v4 model shows similar trends: high precision (0.8705) but reduced recall (0.7463), resulting in lower overall F1-score (0.7909) compared to other ANN architectures.

4.4. Key Findings and Practical Implications

- Feature Normalization: Our experiments confirm that proper feature normalization is crucial for neural network performance in intrusion detection tasks. Standardization ensures consistent scaling across diverse network and biometric features, facilitating more effective learning.

- Architectural Considerations: Dual-branch neural network architectures with addition operations (ANN_v2) consistently outperform other designs except in precision which may be enhanced with experts reviewing alerts or post-filters to avoid false positives, suggesting that parallel processing paths with feature integration through addition is particularly effective for capturing the complex patterns indicative of network intrusions.

- Class Balancing Strategy: Weighted cross-entropy loss functions provide the most effective approach to addressing class imbalance for intrusion detection, outperforming both SMOTE and hybrid sampling strategies across most architectures. This suggests that maintaining the natural distribution of network traffic data while adjusting the learning objective is preferable to artificially altering the dataset distribution.

- Dimensionality Reduction Trade-offs: While autoencoders can simplify models through dimensionality reduction, the associated information loss typically reduces recall, which is particularly problematic for security applications where missing attack instances (false negatives) can have serious consequences.

- Optimal Configuration: The combination of ANN_v2 architecture with weighted loss function emerges as the most effective configuration for IoMT intrusion detection, achieving 94.03% accuracy and 0.8716 F1-score. This configuration offers an excellent balance between precision and recall, making it well-suited for real-world deployment.

4.5. Comparative Analysis with Previous Work

- Performance Improvement: Our dual-branch ANN architecture with addition operations (ANN_v2) combined with weighted loss function achieves an AUC of 0.8786 and an F1-score of 0.8716, representing relative improvements of 12.8% and 20.7% respectively over the best ELM model from [11].

- Architectural Sophistication: Moving beyond the single hidden layer constraint of ELM, our current work explores multi-layer architectures with various connectivity patterns, demonstrating that architectural design choices significantly impact detection performance.

- Dimensionality Reduction Analysis: While [11] work focused on direct classification of input features, this study provides critical insights into the trade-offs associated with autoencoder preprocessing, revealing that the information loss during dimensionality reduction compromises recall—a crucial metric for security applications.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Islam, S.R.; Kwak, D.; Kabir, M.H.; Hossain, M.; Kwak, K.S. The Internet of Things for health care: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2015, 3, 678–708.

- Alrawi, O.; Lever, C.; Antonakakis, M.; Monrose, F. Security analysis of IoT devices. ACM Transactions on Privacy and Security (TOPS) 2019, 22, 1–36.

- Osama, M.; Ateya, A.A.; Sayed, M.S.; Hammad, M.; Pławiak, P.; Abd El-Latif, A.A.; Elsayed, R.A. Internet of medical things and healthcare 4.0: Trends, requirements, challenges, and research directions. Sensors 2023, 23, 7435.

- Zarpelão, B.B.; Miani, R.S.; Kawakani, C.T.; de Alvarenga, S.C. A survey of intrusion detection in Internet of Things. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2017, 84, 25–37.

- Butun, I.; Morgera, S.D.; Sankar, R. A survey of intrusion detection systems in wireless sensor networks. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2013, 16, 266–282.

- Mujahid, M.; Mirdad, A.R.; Alamri, F.S.; Ara, A.; Khan, A. Software defined network intrusion system to detect malicious attacks in computer Internet of Things security using deep extractor supervised random forest technique. PeerJ Computer Science 2025, 11, e3103.

- Farhan, S.; Mubashir, J.; Haq, Y.U.; Mahmood, T.; Rehman, A. Enhancing network security: an intrusion detection system using residual network-based convolutional neural network. Cluster Computing 2025, 28, 251.

- Alrayes, F.S.; Zakariah, M.; Amin, S.U.; Khan, Z.I.; Alqurni, J.S. CNN Channel Attention Intrusion Detection System Using NSL-KDD Dataset. Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 79.

- Mitchell, R.; Chen, I.R. A survey of intrusion detection techniques for cyber-physical systems. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2014, 46, 1–29.

- Farnaaz, N.; Jabbar, M. Random forest modeling for network intrusion detection system. Procedia Computer Science 2016, 89, 213–217.

- Cherif, A. Intrusion Detection for Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) using Extreme Learning Machine. In Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Conference on Advanced Innovations in Smart Cities (ICAISC), 2025, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Hirasawa, K.; Hu, J.; Murata, J. Multi-branch structure of layered neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Neural Information Processing, 2002. ICONIP ’02., 2002, Vol. 1, pp. 243–247 vol.1. [CrossRef]

- Geirhos, R.; Jacobsen, J.H.; Michaelis, C.; Zemel, R.; Brendel, W.; Bethge, M.; Wichmann, F.A. Shortcut learning in deep neural networks. Nature Machine Intelligence 2020, 2, 665–673. [CrossRef]

- Diro, A.A.; Chilamkurti, N. Distributed attack detection scheme using deep learning approach for Internet of Things. Future Generation Computer Systems 2018, 82, 761–768.

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507.

- Hady, A.A. WUSTL-EHMS-2020 . https://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/ehms/index.html, 2020. [Online; accessed 20-October-2024].

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of artificial intelligence research 2002, 16, 321–357.

- Information.; Computer Science University of California, I. KDD Cup 1999 Data . http://kdd.ics.uci.edu/databases/kddcup99/kddcup99.html, Oct. 2007. [Online; accessed 19-October-2024].

- Zhang, J.; Zulkernine, M.; Haque, A. Random-Forests-Based Network Intrusion Detection Systems. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2008, 38, 649–659. [CrossRef]

- Hady, A.A.; Ghubaish, A.; Salman, T.; Unal, D.; Jain, R. Intrusion Detection System for Healthcare Systems Using Medical and Network Data: A Comparison Study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 106576–106584. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhang, S.; Yan, J.; Ai, X.; Dai, K. An efficient intrusion detection system based on support vector machines and gradually feature removal method. Expert Systems with Applications 2012, 39, 424–430. [CrossRef]

- Tesfahun, A.; Bhaskari, D.L. Intrusion Detection Using Random Forests Classifier with SMOTE and Feature Reduction. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Cloud & Ubiquitous Computing & Emerging Technologies, 2013, pp. 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Trivedi, B.H. Reducing Features of KDD CUP 1999 Dataset for Anomaly Detection Using Back Propagation Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2015 Fifth International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Technologies, 2015, pp. 247–251. [CrossRef]

- ZAIB, M.H. NSL KDD Dataset. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hassan06/nslkdd, 2024. [Online; accessed 19-July-2024].

- Kale, R.; Lu, Z.; Fok, K.W.; Thing, V.L.L. A Hybrid Deep Learning Anomaly Detection Framework for Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 8th Intl Conference on Big Data Security on Cloud (BigDataSecurity), IEEE Intl Conference on High Performance and Smart Computing, (HPSC) and IEEE Intl Conference on Intelligent Data and Security (IDS), 2022, pp. 137–142. [CrossRef]

- Albulayhi, K.; Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Alsuhibany, S.A.; Jillepalli, A.A.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Sheldon, F.T. IoT Intrusion Detection Using Machine Learning with a Novel High Performing Feature Selection Method. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5015. [CrossRef]

- Iwendi, C.; Anajemba, J.H.; Biamba, C.; Ngabo, D. Security of Things Intrusion Detection System for Smart Healthcare. Electronics 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, J.; Meher, S.K.; Souri, A.; Naik, B.; Vimal, S. Extreme learning machine and bayesian optimization-driven intelligent framework for IoMT cyber-attack detection. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 14866–14891.

- Nour, M. ToN_IoT Datasets. https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/toniot-datasets, 2024. [Online; accessed 19-July-2024].

- Alani, M.M.; Mashatan, A.; Miri, A. Explainable Ensemble-Based Detection of Cyber Attacks on Internet of Medical Things. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, Intl Conf on Cloud and Big Data Computing, Intl Conf on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech), 2023, pp. 0609–0614. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2002, 16, 321–357.

- Liu, X.Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Z.H. Exploratory undersampling for class-imbalance learning. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 2020, 39, 539–550.

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Doll’ar, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2017, pp. 2980–2988.

| Authors | Dataset | Methodology | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. [19] | KDD 1999 | Random Forest (RF) for anomaly detection | 95% accuracy, 1% false-positive rate |

| Li et al. [21] | KDD 1999 | Clustering, Ant Colony Algorithm, SVM | 98.62% accuracy, MCC of 0.861 |

| Shah et al. [23] | KDD 1999 | Information Gain (IG) for feature reduction | Improved model performance with reduced dataset |

| Tesfahun et al. [22] | KDD 1999 | Random Forest with IG | Enhanced generalization capacity |

| Kale et al. [25] | NSL-KDD, CIC-IDS2018, TON IoT | Three-stage deep learning framework (K-means, GANomaly, CNN) | 91.6% accuracy on NSL-KDD |

| Albulayhi et al. [26] | NSL-KDD | Feature selection using set theory | 99.98% classification accuracy |

| Iwendi et al. [27] | NSL-KDD | RF with Genetic Algorithm for feature optimization | 98.81% detection rate, 0.8% false alarm rate |

| Nayak et al. [28] | ToN_IoT | Bayesian Optimization and ELM | High precision and recall, but no class imbalance solution |

| Hady et al. [20] | Custom dataset WUSTL-EHMS-2020 (16,000 records) | Integration of medical and network data using EHMS testbed | Improved performance by 7% to 25%; SVM accuracy 92.46%, ANN AUC 92.98% |

| Mohammed M. et al. [30] | WUSTL-EHMS-2020 | Ensemble learning and explainable AI with random over sampling | 99.96% accuracy and 0.998 F1 score |

| Cherif A. [11] | WUSTL-EHMS-2020 | Multiple neural network architectures with three class balancing approaches | Dual-branch model: 94.03% accuracy, 0.8716 F1-score with weighted loss |

| Measurement | Value |

| Size | 4.4 MB |

| Normal samples | 14,272 (87.5%) |

| Attack samples | 2,046 (12.5%) |

| Total number of samples | 16,318 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

| Learning rate | |

| Batch size | 64 |

| Weight decay | |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Loss function | Cross Entropy (standard or weighted) |

| Evaluation interval | 50 epochs |

| Maximum epochs | 200-500 (architecture dependent) |

| Model | Class Balancing Method | AUC | ACC | PR | RC | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN | SMOTE | 0.8491 | 0.8753 | 0.7427 | 0.8491 | 0.7783 |

| ANN_v1 | SMOTE | 0.8544 | 0.8983 | 0.7750 | 0.8544 | 0.8062 |

| ANN_v2 | SMOTE | 0.8766 | 0.8955 | 0.7721 | 0.8766 | 0.8096 |

| ANN_v3 | SMOTE | 0.8740 | 0.9032 | 0.7851 | 0.8740 | 0.8182 |

| ANN_v4 | SMOTE | 0.8554 | 0.9035 | 0.7839 | 0.8554 | 0.8129 |

| AE+ANN_v4 | SMOTE | 0.7485 | 0.9308 | 0.9383 | 0.7485 | 0.8085 |

| ANN | Hybrid | 0.8518 | 0.9179 | 0.8132 | 0.8518 | 0.8308 |

| ANN_v1 | Hybrid | 0.8577 | 0.9213 | 0.8201 | 0.8577 | 0.8373 |

| ANN_v2 | Hybrid | 0.8750 | 0.9323 | 0.8437 | 0.8750 | 0.8582 |

| ANN_v3 | Hybrid | 0.8671 | 0.9203 | 0.8163 | 0.8671 | 0.8387 |

| ANN_v4 | Hybrid | 0.8739 | 0.9151 | 0.8047 | 0.8739 | 0.8335 |

| AE+ANN_v4 | Hybrid | 0.7925 | 0.9059 | 0.7942 | 0.7925 | 0.7934 |

| ANN | Weighted cross-entropy Loss | 0.8588 | 0.9145 | 0.8049 | 0.8588 | 0.8283 |

| ANN_v1 | Weighted cross-entropy Loss | 0.8559 | 0.9197 | 0.8168 | 0.8559 | 0.8345 |

| ANN_v2 | Weighted cross-entropy Loss | 0.8786 | 0.9403 | 0.8650 | 0.8786 | 0.8716 |

| ANN_v3 | Weighted cross-entropy Loss | 0.8467 | 0.8161 | 0.6938 | 0.8467 | 0.7216 |

| ANN_v4 | Weighted cross-entropy Loss | 0.8534 | 0.8382 | 0.7096 | 0.8534 | 0.7431 |

| AE+ANN_v4 | Weighted cross-entropy Loss | 0.7463 | 0.9200 | 0.8705 | 0.7463 | 0.7909 |

| Study | Approach | Acc | F1 | AUC | PR | RC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cherif A. [11] | ELM (256) + SMOTE | 0.8444 | 0.7223 | 0.7789 | 0.6949 | 0.7789 |

| Cherif A. [11] | ELM (256) + Weighted cross-entropy Loss | 0.9305 | 0.8037 | 0.7404 | 0.9518 | 0.7404 |

| Hady et al. [20] | SVM with SMOTE | 0.9246 | Not reported | 0.8237 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Hady et al. [20] | ANN with SMOTE | 0.9040 | Not reported | 0.9342 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mohammed et al. [30] | Ensemble with random over-sampling | 0.9980 | 0.9980 | Not reported | 0.9980 | 0.9980 |

| Current study | ANN_v2 + Weighted Loss | 0.9403 | 0.8716 | 0.8786 | 0.8650 | 0.8786 |

| Current study | AE+ANN_v4 + SMOTE | 0.9308 | 0.8085 | 0.7485 | 0.9383 | 0.7485 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).