Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

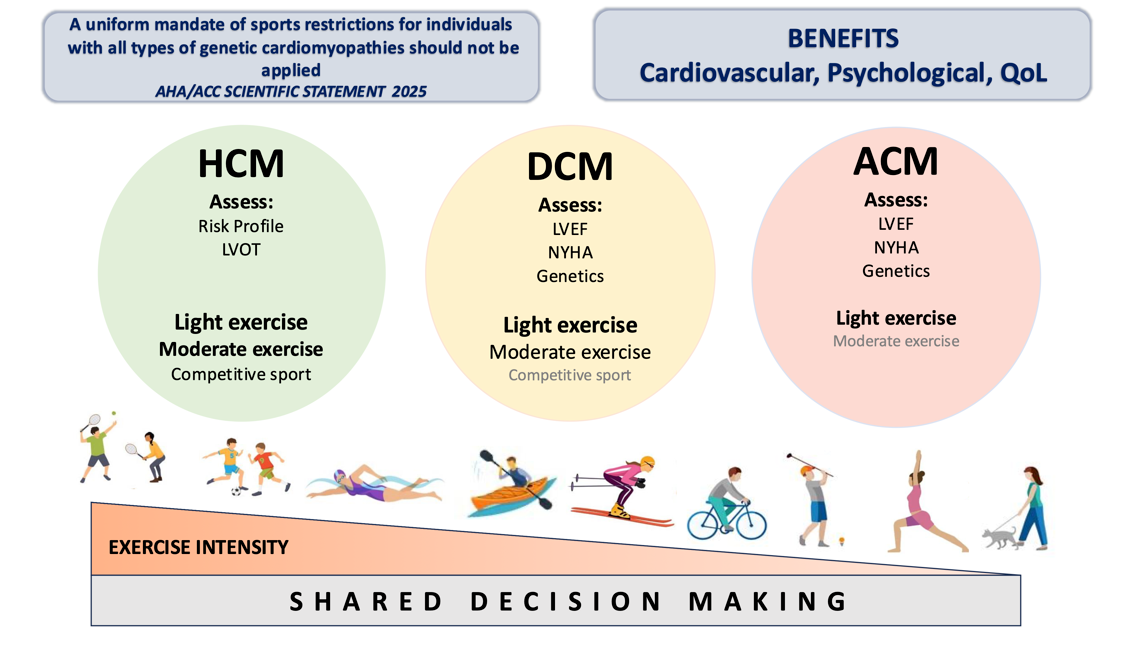

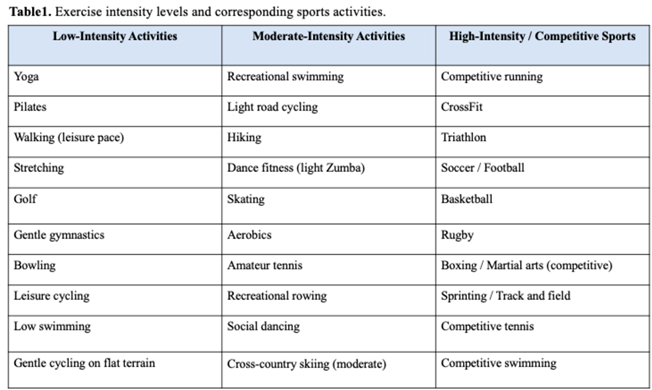

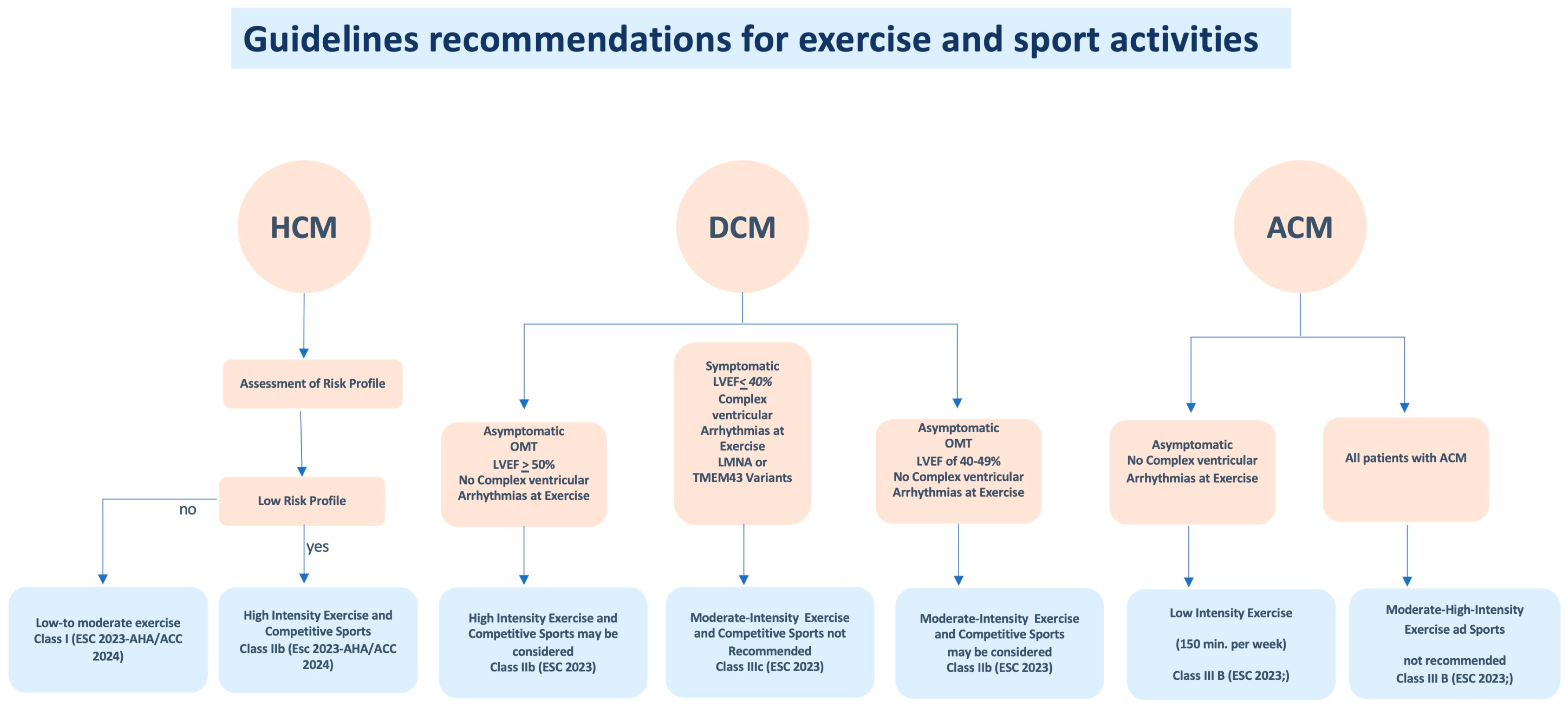

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)

Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM)

Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (ACM)

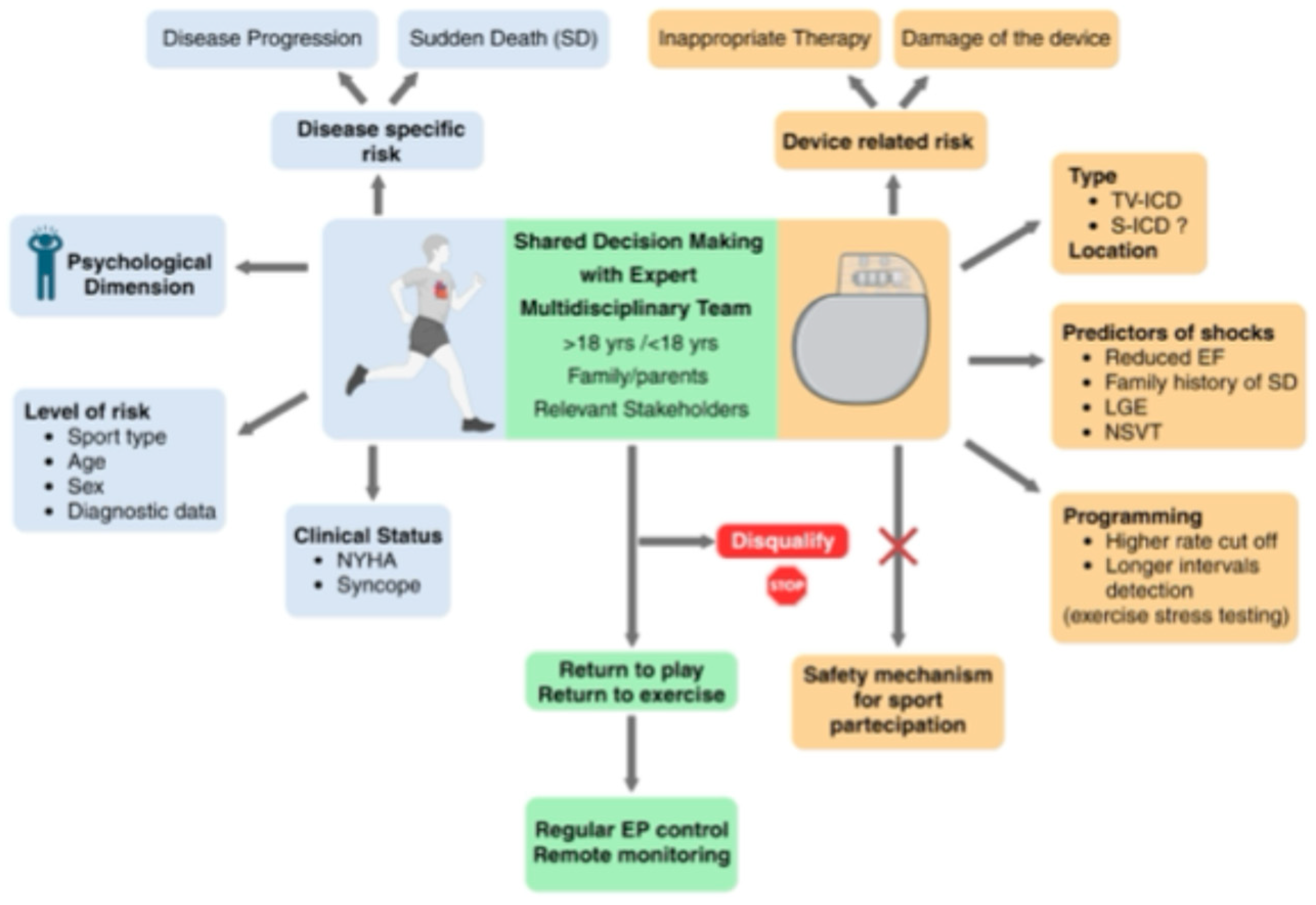

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator and Sport Activity

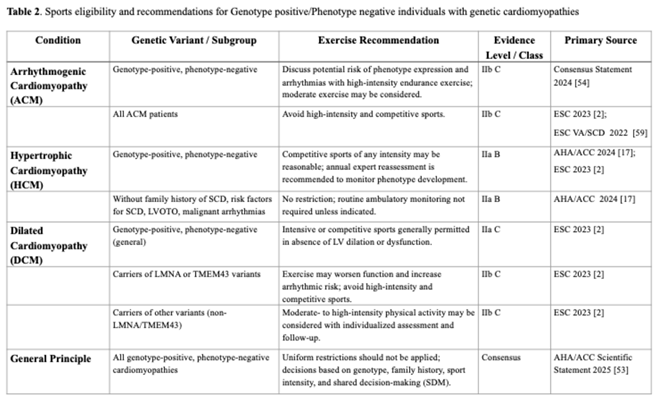

Sports Participation in Genotype-Positive/Phenotype-Negative Athletes with Genetic Cardiomyopathies

Exercise Prescription and Rehabilitation in Cardiomyopathies

Conclusions

References

- Isath A, Koziol KJ, Martinez MW, Garber CE, Martinez MN, Emery MS, Baggish AL, Naidu SS, Lavie CJ, Arena R et al. Exercise and cardiovascular health: A state-of-the-art review. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023;79:44-52. Epub 2023 Apr 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, Arbustini E, Barriales-Villa R, Basso C, Bezzina CR, Biagini E, Blom NA, de Boer RA et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 1;44(37):3503-3626. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt B, Fonarow GC, Goldberg LR, Guglin M, Josephson RA, Forman DE, Lin G, Lindenfeld J, O'Connor C, Panjrath G et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation for Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Expert Panel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021 Mar 23;77(11):1454-1469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimers CD, Knapp G, Reimers AK. Does physical activity increase life expectancy? A review of the literature. J. Aging Res. 2012; 2012:243958. Epub 2012 Jul 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, Dumuid D, Virgara R, Watson A, Szeto K, O'Connor E, Ferguson T, Eglitis E et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023;57(18):1203-1209. Epub 2023 Feb 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, Coats AJ, Dalal HM, Lough F, Rees K, Singh S, Taylor RS. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2015;2(1):e000163. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson DF, Siebert DM, Kucera KL, Thomas LC, Maleszewski JJ, Lopez-Anderson M, Suchsland MZ, Harmon KG, Drezner JA. Etiology of Sudden Cardiac Arrest and Death in US Competitive Athletes: A 2-Year Prospective Surveillance Study. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2020;30(4):305-314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, Michieli P, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA. 2006;296(13):1593-601. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron BJ, Isner JM, McKenna WJ. 26th Bethesda conference: recommendations for determining eligibility for competition in athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. Task Force 3: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, myocarditis and other myopericardial diseases and mitral valve prolapse. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:880-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado D, Migliore F, Basso C, Thiene G. Exercise and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Herz. 2006;31(6):553-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han J, Lalario A, Merro E, Sinagra G, Sharma S, Papadakis M, Finocchiaro G. Sudden Cardiac Death in Athletes: Facts and Fallacies. J Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023;10:68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron BJ, Zipes DP. Introduction: eligibility recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities-general considerations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1318-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, Spirito P, Rakowski H, Towbin JA, Rowin EJ, Maron MS, Sherrid MV. Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022;79(4):372-389. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reineck E, Rolston B, Bragg-Gresham JL, Salberg L, Baty L, Kumar S, Wheeler MT, Ashley E, Saberi S, Day SM. Physical activity and other health behaviors in adults with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013;111(7):1034-9. Epub 2013 Jan 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivotto I, Maron BJ, Tomberli B, Appelbaum E, Salton C, Haas TS, Gibson CM, Nistri S, Servettini E, Chan RH, et al. Obesity and its association to phenotype and clinical course in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013; 62: 449-457.

- Fumagalli C, Maurizi N, Day SM, Ashley EA, Michels M, Colan SD, Jacoby D, Marchionni N, Vincent-Tompkins J, Ho CY et al. Association of Obesity With Adverse Long-term Outcomes in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(1):65-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ommen SR, Ho CY, Asif IM, Balaji S, Burke MA, Day SM, Dearani JA, Epps KC, Evanovich L, Ferrari VA, et al. AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR Guideline for the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(23):e1239-e1311. [CrossRef]

- Albulushi A, Al-Mahmeed W, Al-Hinai A, Al-Kindi S, Al-Lawati A, Al-Farsi S, Al-Awaidy A, Al-Busaidi N, Al-Hadhrami M, Al-Abri M et al. Review Article—Exercise and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Risks, Benefits, and Safety—A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2025;37(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir HL, Hasselberg NE, Sjaastad I, Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH, Stokke MK, Røe AT, Christensen G, Lunde IG, Andreassen K et al. Exercise Training in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Without Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2025;151(2):132–144. PMID: not available. [CrossRef]

- Sweeting J, Ingles J, Timperio A, Patterson J, Ball K, Semsarian C. Physical activity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: prevalence of inactivity and perceived barriers. Open Heart. 2016;3(2):e000484. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi S, Wheeler M, Bragg-Gresham J, Hornsby W, Agarwal PP, Attili A, Concannon M, Dries AM, Shmargad Y, Salisbury H et al. Effect of Moderate-Intensity Exercise Training on Peak Oxygen Consumption in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317:1349–1357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klempfner R, Kamerman T, Schwammenthal E, Nahshon A, Hay I, Goldenberg I, Dov F, Arad M. Efficacy of exercise training in symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: results of a structured exercise training program in a cardiac rehabilitation center. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015;22(1):13–19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampert R, Olshansky B, Link MS, Estes NAM, Ackerman MJ, Marcus F, Zipes DP, Maron BJ, Saarel EV, Lawless CE et al. Vigorous Exercise in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8(6):595–605. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu J, Gati S, Sharma S, Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Behr E, Elliott P, Day SM, Maron BJ, Lampert R et al. High intensity exercise programme in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized trial. Eur. Heart J. 2025;46(19):1803–1815. PMID: not available. [CrossRef]

- Aengevaeren VL, Gommans DHF, Dieker HJ, Timmermans J, Verheugt FWA, Bakker J, Hopman MTE, DE Boer MJ, Brouwer MA, Thompson PD, Kofflard MJM, Cramer GE, Eijsvogels TMH. Association between Lifelong Physical Activity and Disease Characteristics in HCM. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Oct;51(10):1995-2002. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelliccia A, Caselli S, Pelliccia M, Musumeci MB, Lemme E, Di Paolo FM, Maestrini V, Russo D, Limite L, Borrazzo C, Autore C. Clinical outcomes in adult athletes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a 7-year follow-up study. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(16):1008-1012. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelliccia A, Sharma S, Gati S, Bäck M, Börjesson M, Caselli S, Collet JP, Corrado D, Drezner JA, Halle M et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines on Sports Cardiology and Exercise in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(1):17–96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MRG, Wang L, Teekakirikul P, Christodoulou D, Conner L, DePalma SR, McDonough B, Sparks E et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(7):619–628. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloway CJ, Dass S, Cochlin LE, Rider OJ, Mahmod M, Snoeren NS, Karamitsos TD, Ariga R, Francis JM, Neubauer S. Exercise training in dilated cardiomyopathy improves rest and stress cardiac function without changes in cardiac high energy phosphate metabolism. Heart. 2012;98:1083–1090. [CrossRef]

- Mehani SH, Elnaggar RK. Correlation between changes in diastolic dysfunction and health-related quality of life after cardiac rehabilitation program in dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Adv. Res. 2013;4:189–200. [PubMed]

- Seo YG, Lim JY, Park JJ, Park SJ, Oh IY, Lee SY, Choi JO, Jeon ES, Kim JJ, Yoo BS et al. What Is the Optimal Exercise Prescription for Patients With Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Cardiac Rehabilitation? A Systematic Review. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2019;39:235–240. [CrossRef]

- Swank AM, Horton J, Fleg JL, Fonarow GC, Keteyian S, Goldberg L, Wolfel G, Handberg EM, Bensimhon D, Illiou MC et al. Modest Increase in Peak VO₂ Is Related to Better Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Heart Failure Patients. Circ. Heart Fail. 2012;5:579–585. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer M, Seyfarth T, Sandstede J, Landschütz W, Lipke C, Köstler H, von Kienlin M, Harre K, Hahn D. Effects of exercise training on myocardial energy metabolism and ventricular function assessed by phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy and MRI in dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;51:1883–1891. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolen KQ, Kemppainen J, Ukkonen H, Kalliokoski KK, Luotolahti M, Lehikoinen P, Hämäläinen H, Salo T, Airaksinen KEJ, Nuutila P et al. Exercise training improves biventricular oxidative metabolism and left ventricular efficiency in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;41(3):460–467. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Kayvanpour E, Ameling S, Umland B, Rücker B, Asatryan B, Keller T, Katus HA, Meder B. Personalized care in dilated cardiomyopathy: Rationale and study design of the active DCM trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2024;11:4400–4406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado D, Basso, Judge DP. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2017;121:784–802. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James CA, Bhonsale A, Tichnell C, Murray B, Russell SD, Tandri H, Tedford RJ, Judge DP, Calkins H. Exercise increases age-related penetrance and arrhythmic risk in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated desmosomal mutation carriers. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62(14):1290–1297. [CrossRef]

- Lie ØH, Dejgaard LA, Saberniak J, Rootwelt-Norberg C, Stokke MK, Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH. Harmful effects of exercise intensity and duration in patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2018;4:744–753. [CrossRef]

- Bosman LP, James CA, Cadrin-Tourigny J, Murray B, Tichnell C, Bhonsale A, Wang W, Crosson J, van der Heijden JF, Judge DP et al. Integrating Exercise Into Personalized Ventricular Arrhythmia Risk Prediction in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2022;15(2):e010221. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruwald AC, Marcus F, Estes NAM, Link MS, McNitt S, Polonsky B, Towbin JA, Moss AJ, Zareba W, Gear K et al. Association of competitive and recreational sport participation with cardiac events in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: results from the North American multidisciplinary study. Eur. Heart J. 2015;36:1735–1743. [CrossRef]

- Saberniak J, Hasselberg NE, Borgquist R, Platonov PG, Sarvari SI, Smith HJ, Ribe M, Holst AG, Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH. Vigorous physical activity impairs myocardial function in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and in mutation-positive family members. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014;16:1337–1344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz FM, Sanz-Rosa D, Roche-Molina M, Garcia-Prieto J, Garcia-Ruiz JM, Pizarro G, Jimenez-Borreguero LJ, Torres M, Bernad A, Ruiz-Cabello J et al. Exercise triggers ARVC phenotype in mice expressing a disease-causing mutated version of human plakophilin-2. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;65(14):1438–1450. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, James CA, Calkins H, Judge DP, Tichnell C, Murray B, Te Riele ASJM, Crosson J, Tandri H, Marcus FI et al. Exercise restriction is protective for genotype-positive family members of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy patients. Europace. 2020;22:1270–1278. [PubMed]

- Dei LL, Han J, Romano S, Sciarra L, Asimaki A, Papadakis M, Sharma S, Finocchiaro G. Exercise Prescription in Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy: Finding the Right Balance Between Risks and Benefits. J.Am. Heart Assoc. 2025 Jun 17;14(12):e039125. [CrossRef]

- Sawant AC, Bhonsale A, te Riele AS, Tichnell C, Murray B, Russell SD, Tandri H, Judge DP, Calkins H, James CA. Exercise has a disproportionate role in the pathogenesis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy in patients without desmosomal mutations. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001471. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa S, Koch K, Gasperetti A, Akdis D, Brunckhorst C, Fu G, Tanner FC, Ruschitzka F, Duru F, Saguner AM. Changes in Exercise Capacity and Ventricular Function in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy: The Impact of Sports Restriction during Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11(5):1150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant AC, Te Riele AS, Tichnell C, Murray B, Bhonsale A, Tandri H, Judge DP, Calkins H, James CA. Safety of American Heart Association-recommended minimum exercise for desmosomal mutation carriers. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:199-207. Epub 2015 Aug 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampert R, Olshansky B, Heidbuchel H, Lawless C, Saarel E, Ackerman M, Calkins H, Estes NA, Link MS, Maron BJ,et al. Safety of sports for athletes with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results of a prospective, multinational registry. Circulation. 2013;127:2021–2030. [CrossRef]

- Lampert R, Olshansky B, Heidbuchel H, Lawless CE, Saarel EV, Ackerman MJ, Calkins H, Estes NAM, Link MS, Marcus F et al. Safety of Sports for Athletes With Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators: Long-Term Results of a Prospective Multinational Registry. Circulation. 2017;135:2310–2312. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidbuchel H, Arbelo E, D'Ascenzi F, Borjesson M, Boveda S, Castelletti S, Miljoen H, Mont L, Niebauer J, Papadakis M, et al. EAPC/EHRA update of the Recommendations for participation in leisure-time physical activity and competitive sports in patients with arrhythmias and potentially arrhythmogenic conditions. Recommendations for participation in leisure-time physical activity and competitive sports of patients with arrhythmias and potentially arrhythmogenic conditions. Part 2: ventricular arrhythmias, channelopathies, and implantable defibrillators. Europace. 2021;23:147-148. [CrossRef]

- Tobert KE, Bos JM, Cannon BC, Ackerman MJ. Outcomes of Athletes With Genetic Heart Diseases and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators Who Chose to Return to Play. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022;97(11):2028-2039. Epub 2022 Aug 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olshansky B, Atteya G, Cannom D, Heidbuchel H, Saarel EV, Anfinsen OG, Cheng A, Gold MR, Müssigbrodt A, Patton KK, et al. Competitive athletes with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators-How to program? Data from the Implantable Cardioverter- Defibrillator Sports Registry. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(4):581-587. [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Baggish AL, Levine BD, Ackerman MJ, Day SM, Dineen EH, Guseh Ii JS, La Gerche A, Lampert R, Martinez MW, et al. Clinical Considerations for Competitive Sports Participation for Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025;85(10):1059-1108. Epub 2025 Feb 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampert R, Chung EH, Ackerman MJ, Arroyo AR, Darden D, Deo R, Dolan J, Etheridge SP, Gray BR, Harmon KG, et al. 2024 HRS expert consensus statement on arrhythmias in the athlete: Evaluation, treatment, and return to play. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21(10):e151-e252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron BJ, Daimee U, Olshansky B. Outcomes of sports participation for patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: data from the ICD Sports Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020; 75(11): 305.

- Chorin E, Lampert R, Bijsterveld NR, Knops RE, Wilde AAM, Heidbuchel H, Krahn A, Goldenberg I, Rosso R, Viskin D, ey al. Safety of Sports for Patients with Subcutaneous Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (SPORT S-ICD): study rationale and protocol. Heart Rhythm O2. 2024; 5(3):182- 188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez MW, Ackerman MJ, Annas GJ, Baggish AL, Day SM, Harmon KG, Kim JH, Levine BD, Putukian M, Lampert R. Sports Participation by Athletes With Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024; 83(8): 865-868.

- Paldino A, Rossi M, Dal Ferro M, Tavcar I, Behr E, Sharma S, Papadakis M, Sinagra G, Finocchiaro G. Sport and Exercise in Genotype positive (+) Phenotype negative (−) Individuals: Current Dilemmas and Future Perspectives. Eur.J.Prev. Cardiol. 2023; 30: 871-883.

- Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, Winkel BG, Behr ER, Blom NA, Charron P, Corrado D, Dagres N, de Chillou C, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur. Heart J. 2022;43:3997-4126. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan A.C. Schoonvelde, Georgios M. Alexandridis, Laura B. Price, Arend F.L. Schinkel, Alexander Hirsch, Peter-Paul Zwetsloot, Janneke A.E. et al. Family screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Initial cardiologic assessment, and long-term follow-up of genotype-positive phenotype-negative individuals. MedRxiv preprint, 2024 Nov 1. [CrossRef]

- Andreassen K, Rixon C, Hansen MH, Hauge-Iversen IM, Zhang L, Sadredini M, Erusappan PM, Sjaastad I, Christensen G, Haugaa KH, et al. Beneficial effects of exercise initiated before development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in genotype-positive mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2023;324(6):H881-H892. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mierzynska A, Sadowski K, Piotrowicz R, Klopotowski M, Wolszakiewicz J, Lech A, Wit kowski A, Smolis-Bak E, Kowalik I and Pi otrowska D. Psychological well-being and ill ness perception in hypertrophic cardiomy-opathy patients undergoing hybrid cardiac re habilitation. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2023; 30: 125. 253.

- Wasserstrum Y, Barbarova I, Lotan D, Kuperstein R, Shechter M, Freimark D, Segal G, Klempfner R, Arad M. Efficacy and safety of exercise rehabilitation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol. 2019 Nov;74(5):466-472. Epub 2019 Jun 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chichagi F, Ghanbari-Mardasi K, Shirsalimi N, Sheikh M, Hakim D. Physical cardiac rehabilitation effects on cardio-metabolic outcomes in the patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2024 Dec 15;14(6):330-341. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peretto G, Maranta F, Cianfanelli L, Sala S, Cianflone D. Outcomes of inflammatory cardiomyopathy following cardiac rehabilitation. J. Cardiovasc. Med. (Hagerstown). 2023; 24: 59-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Gutiérrez KG, Calderón-Fernández A, Suarez-Jimenez HC, Mendoza- Gonzalez AS, Manjarrez-Granados EA, Cuevas-Cueto DF, Bátiz-Armenta F, Márquez-Valdez AR. Cardiac Rehabilitation in Advanced Dilated Cardiomyopathy Within a Resource-Limited Setting. JACC Case Rep. 2025 Sep 17;30(28):105293. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).