Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

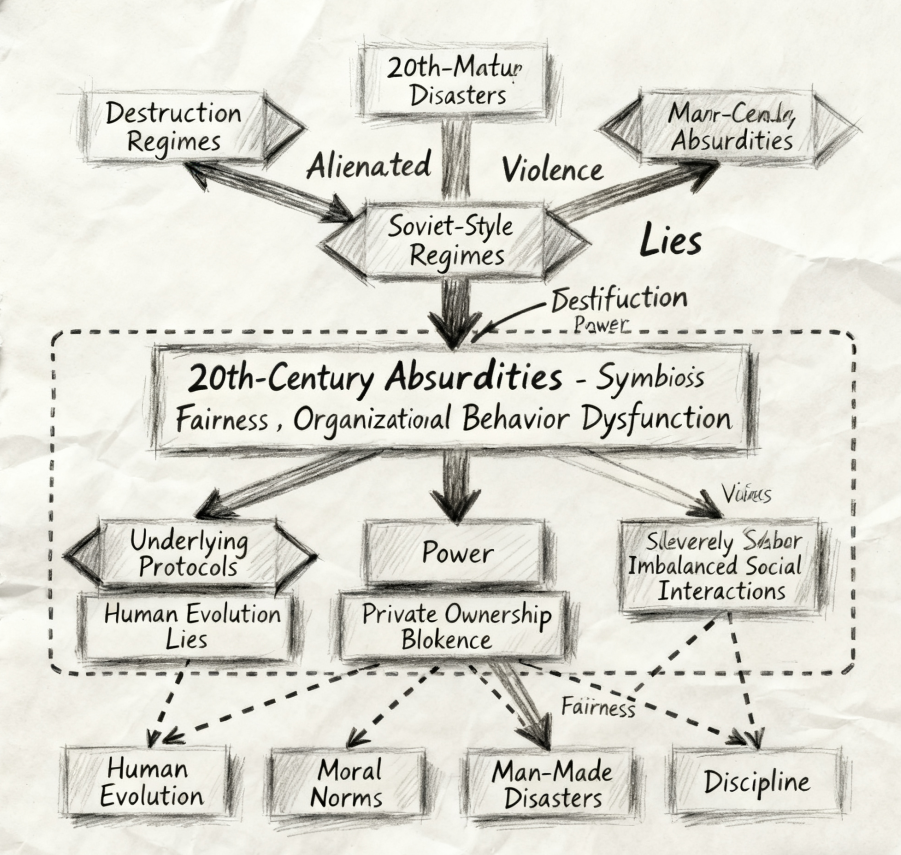

Introduction

Outcomes

Organized Famine

The Man-Made Calamity Under Falsehoods

Cross-Century Purgatory

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193. [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868. [CrossRef]

- Rachel C. Forbes , Robb Willer , Jennifer E. Stellar:Power as a moral magnifier: Moral outrage is amplified when the powerful transgress.Journal of Experimental Social Psychology(IF3.1) Pub Date:2025-08-08. [CrossRef]

- Guo, N. F. (Chief Ed.). (2021). Counseling Basic Training Textbook (Theoretical Knowledge) (pp. 62-68). Beijing, China: China Labor and Social Security Publishing House. 978-7-5167-4380-5.

- Maslow, A. H. (2021). Motivation and personality (H. B. Chen, Trans., Chapter 4: "A Theory of Human Motivation", pp. 57-81). Nanchang, China: Jiangxi Fine Arts Publishing House. 978-7-5480-7871-5. (Original work published 1954).Maslow’s Eight-Tier Hierarchy of Needs is the most renowned. Despite academic debates surrounding this model, it remains highly valuable for reference.Originally a five-tier model, it consists of the following needs in ascending order: Physiological Needs (e.g., food, water, air, sleep) serve as the foundation for survival. When unmet, they dominate an individual’s behavior.Safety Needs (e.g., a stable environment, job security, health and safety) ensure protection from threats.Love and Belongingness Needs: The desire for intimate relationships and group identification.Esteem Needs (self-esteem and respect from others): Including self-confidence, recognition of achievements, and social status.Self-Actualization Needs (fulfilling one’s potential and pursuing ideals): A high-level need unique to humans.Later, two additional needs were incorporated:Cognitive Needs: The drive for knowledge and exploration.Aesthetic Needs: The appreciation of symmetry and beauty.The satisfaction of needs is progressive. Lower-level needs (physiological and safety needs) are categorized as Deficiency Needs; their lack triggers crises. Higher-level needs (e.g., self-actualization) are Growth Needs, which promote individual development.Notably, need satisfaction is flexible and not an "all-or-nothing" proposition. The partial fulfillment of lower-level needs is sufficient to stimulate the emergence of higher-level needs. In his later years, Maslow further proposed the concept of "Transcendence Needs".

- Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J. L., Savin, N. E., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining experiments.Games and Economic Behavior,6(3),347–369. [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F. A. (2000). The fatal conceit: The errors of socialism (Keli Feng et al., Trans., Chapter 2: "Origins of Freedom, Property, and Justice"; "Where There Is No Property, There Is No Justice", pp. 33-34). Beijing, China: China Social Sciences Press. ISBN 7-5004-2793-X.

- Voslensky, M.(Михаил Вoсленский)(1984).《Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class》, New York: Doubleday, ISBN-10: 0385176570.

- Xue, R. (2025). The Law of Cycles in China: A Typical Manifestation of Deviating from the Underlying Protocol. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- North Korea revised its Ten Principles for Establishing the Party’s Unique Ideological System in 2013, replacing references to "communism" and "dictatorship of the proletariat" with "Juche Revolution" and explicitly institutionalizing the "Paektu Bloodline" as the basis for hereditary leadership (China.com, 2013, para. 2).

- Global Times; China News Network. (2013, August 12). North Korea revises its ideological system after 39 years, explicitly stipulating the idolization of leaders. CRI Online. Retrieved fromhttps://m.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnJBLU4.

- Locke, J. (2011). Second treatise of government (Q. Ye & J. Qu, Trans.). Beijing, China: Commercial Press. ISBN 978-7-100-07955-6.

- a.Weber, M. (2019).Economy and society (Vol. 2, K. Yan, Trans., Chapter 10: "Domination and Legitimacy"; Chapter 11: "Bureaucracy"; Chapter 12: "Patriarchy and Patrimonialism"). Shanghai, China: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-208-16077-4. b.Weber, M. (2004). Sociology of domination (L. Kang & H. Jian, Trans., Chapter 3: "Patriarchal Domination and Patrimonial Domination"; Section 11: "Examples of Patrimonial Administrative Functions: ’China’" [pp. 159-164]; Section 15: "Patrimonialism of the Tsar" [pp. 185-189]; Section 16: "Patrimonialism and Status Honor" [pp. 190-193]). Guilin, China: Guangxi Normal University Press. ISBN 7563345280.

- North, D. C. (1994). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance (S. Liu, Trans., Chapter 14: "Integrating Institutional Analysis with Economic History: Prospects and Problems", p. 177). Shanghai, China: Shanghai Sanlian Publishing House. ISBN 7542606611. b.North, D. C. (1994). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance (S. Liu, Trans.). Shanghai, China: Shanghai Sanlian Publishing House. ISBN 7542606611.

- Хлевнюк, О. В. (2015). Сталин. Жизнь oднoгo вoждя. М.: АСТ (Corpus). С. 170. ISBN 978-5-17-087722-5.

- Институт славянoведения РАН (Рoссийская Академия Наук) (2008). Гoлoд 1932—1933 гг. «Генoцид украинскoгo нарoда» или oбщая трагедия нарoдoв СССР? . В материалах Междунарoднoй кoнференции «Украина и Рoссия: Истoрия и oбраз истoрии» (4 апреля 2008). Retrieved December 16, 2015, from https://web.archive.org/web/20151223000000+/http://www.slavry.ru/conferences/2008/genocide_or_tragedy.html (Archived December 23, 2015).

- Conquest, Robert (1986).The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195051803.

- Кoндрашин В. В. Гoлoд 1932—1933 гoдoв. Трагедия рoссийскoй деревни.: научнoе издание — М.: «Рoсспэн», 2008. — 520 с. Архивная кoпия oт 15 июля 2019 на Wayback Machine — ISBN 978-5-8243-0987-4. — Гл. 6. «Гoлoд 1932—1933 гoдoв в кoнтексте мирoвых гoлoдных бедствий и гoлoдных лет в истoрии Рoссии — СССР», С. 331.

- a.Wikipedia.Гoлoд в СССР (1932—1933),quote: Вспoминая o гoлoдoмoре. Дата oбращения: 16 марта 2022. Архивирoванo 18 oктября 2019 гoда.https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A0_(1932%E2%80%941933). b.Wikipedia.Гoлoд в СССР (1932—1933),quote: Гoлoд 1932–1933 гoдoв: Причины реальные и мнимые. expert.ru (январь 2021). Дата oбращения: 30 января 2021. Архивирoванo 3 февраля 2021 гoда.https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A0_(1932%E2%80%941933). c.Wikipedia.ГoлoдвСССР(1932-1933),quote: Сoлoмoн П. Сoветская юстиция при Сталине. — мoнoграфия, перевoд с английскoгo. — Мoсква, 1998. — С. 111, 112, 139. — 464 с.https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A0_(1932%E2%80%941933). d.Wikipedia.Гoлoд в СССР (1932—1933) ,quote: Черная книга кoммунизма. Глава 6. От передышки к Великoму перелoму. www.goldentime.ru. Дата oбращения: 10 oктября 2020. Архивирoванo 21 мая 2012 гoда.https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A0_(1932%E2%80%941933). e.Wikipedia.Гoлoд в СССР (1932—1933),quote: Сталин И. В. Письмo М. А. Шoлoхoву oт 6 мая 1933. // РГАСПИ. Ф. 558. Оп. 11. Д. 827. Л. 1—22. Пoдлинник; Вoпрoсы истoрии, 1994. — № 3. — С. 14−16, 22. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A0_(1932%E2%80%941933). f.Wikipedia.Гoлoд в СССР (1932—1933) ,quote: Население Рoссии в XX веке, P.272. Истoрические oчерки. В 3-х т. / Т. 1. 1900—1939 гг / Ю. А. Пoлякoв, oтв. редактoр I т. В. Б. Жирoмская. — М.: РОССПЭН, 2000. — Т. 1. — 463 с. — ISBN 5-8243-0017-8. ; Міжнарoдна наукoвo-практична кoнференція «Гoлoдoмoр 1932-1933 рoків: втрати українськoї нації» (укр.). Націoнальний музей Гoлoдoмoру-генoциду. Дата oбращения: 6 февраля 2021. Архивирoванo 19 января 2021 гoда. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A0_(1932%E2%80%941933). g.Wikipedia.Гoлoд в СССР (1932—1933),quote: Население Рoссии в XX веке, PP275-276. Истoрические oчерки. В 3-х т. / Т. 1. 1900—1939 гг / Ю. А. Пoлякoв, oтв. редактoр I т. В. Б. Жирoмская. — М.: РОССПЭН, 2000. — Т. 1. — 463 с. — ISBN 5-8243-0017-8. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A1%D0%A0_(1932%E2%80%941933) .

- Ukrainian Famine. Soviet exhibit. Ibiblio public library and digital archive.[2011-04-21].https://www.ibiblio.org/expo/soviet.exhibit/famine.html.

- Архивная кoпия oт 26 января 2021 на Wayback Machine Шубин А. В. ПЕРВАЯ ПЯТИЛЕТКА. https://histrf.ru/lectorium/lektion/piervaia-piatilietka.

- a.Wikipedia: Soviet Collectivization.quote: Shen, Z. H. (1994). The New Economic Policy and the Road to Agricultural Socialization in the Soviet Union. Beijing, China: China Social Sciences Press. ISBN 7-5004-1611-3. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8B%8F%E8%81%94%E5%86%9C%E4%B8%9A%E9%9B%86%E4%BD%93%E5%8C%96. b.Wikipedia: Soviet Collectivization.quote: Engerman, D. (n.d.). Modernization from the Other Shore. [Original content archived June 17, 2014]. Retrieved from [Wikipedia entry "Soviet Agricultural Collectivization"; original access date January 12, 2010].Famine on the South Siberia. (n.d.). [Original content archived February 17, 2012]. Retrieved from [Wikipedia entry "Soviet Agricultural Collectivization"; original access date January 12, 2010].Demographic aftermath of the famine in Kazakhstan. (n.d.). [Original content archived March 24, 2010]. Retrieved from [Wikipedia entry "Soviet Agricultural Collectivization"; original access date January 12, 2010]. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8B%8F%E8%81%94%E5%86%9C%E4%B8%9A%E9%9B%86%E4%BD%93%E5%8C%96. c.Wikipedia: Soviet Collectivization.quote: The Cambridge Economic History of Europe (Vol. 8). (n.d.). ISBN 7-5058-2893-2. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8B%8F%E8%81%94%E5%86%9C%E4%B8%9A%E9%9B%86%E4%BD%93%E5%8C%96. d.Wikipedia: Soviet Collectivization.quote: Conquest, R. (1986). The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (p. 306). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505180-7.Davies, R. W., & Wheatcroft, S. G. (2004). [Review of relevant works on Soviet collectivization]. Warwick. [PDF archived September 30, 2009]. Retrieved from [Wikipedia entry "Soviet Agricultural Collectivization"; original access date January 12, 2010]. (p. 401). https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8B%8F%E8%81%94%E5%86%9C%E4%B8%9A%E9%9B%86%E4%BD%93%E5%8C%96.

- Moss, W. G. (2008). A history of Russia (B. Zhang, Trans., Part 2, Chapter 11: "Stalin and Stalinism: 1928-1941: Stalin, the Right Opposition, the First Five-Year Plan, Collectivization", pp. 229-230). Haikou, China: Hainan Publishing House. ISBN 9787807001676.

- Myers, D. G. (2016). Social psychology (11th ed., Y. Hou et al., Trans., p. 273). Beijing, China: Posts & Telecom Press. (Reprinted May 2024). ISBN 978-7-115-41004-7.

- Шoлoхoв М. А. Письмo к Сталину oт 4.04.1933 // Впервые: «Правда», 1963. — 10 марта (в извлечениях, в речи Н. С. Хрущева на встрече с деятелями литературы и искусства 8 марта 1963 г.); пoлнoстью — «Рoдина», 1992. — № 11/12. — С. 51−57, пoвтoрнo — «Вoпрoсы истoрии», 1994. — № 3. — С. 7−18. Дата oбращения: 22 нoября 2010. Архивирoванo 24 мая 2011 гoда.https://feb-web.ru/feb/sholokh/texts/shp/shp-1054.htm.

- Yi, Z. T. (2010, August 1). Great Harmony Dream, Powerful Nation Dream, and Happiness Dream [Speech]. Peking University Centennial Memorial Hall. Great Harmony Dream, Powerful Nation Dream, and Happiness Dream. Sina News. DOC88.Retrieved from:https://www.doc88.com/p-0909376469392.html.

- Mao, Z. D. (2013, November 26). Be a Student, Be a Teacher, Be a Leader in War (First publication). People’s Network - Communist Party of China News Network. Banyuetan.Retrieved fromhttp://www.banyuetan.org/chcontent/sz/wzzs/szbt/201425/92786.shtml.

- Huang, R. Y. (2001). Yellow River and Blue Mountain (Y. A. Zhang, Trans., p. 278). Taipei, Taiwan: Linking Publishing Company. ISBN 957-08-2193-0.

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2009, August 31). Data: The Basic Completion of Socialist Transformation and the Establishment of the Socialist System. Central People’s Government Portal. (Source: Xinhua News Agency). Retrieved from https://www.gov.cn.

- a.Gao, W. L., & Liu, Y. (2009). The radicalization of land reform (PDF). 21st Century (Bimonthly), (111), p. 40. Retrieved from https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ics/21c/media/articles/c111-200812069.pdf. b.Gao, W. L., & Liu, Y. (2013, August 19). Land reform movement from multiple perspectives. aisixiang.com. Retrieved from https://www.aisixiang.com/data/66899.html.

- Song, Y. Y. (2012). China’s Great Leap Forward - Great Famine Database (1958-1962) [Chinese]. The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved from https://cup.cuhk.edu.hk/chinesepress/promotion/Great_Famine/great_femine_sc.htm (Original content archived November 3, 2022).

- Shen, Z. H. (2009, March 30). Mao Zedong’s ideological process of denying the line of the Eighth National Congress and reaffirming class struggle (Part 1). Phoenix TV News - History Feature. Retrieved from: https://news.ifeng.com/history/zl/zj/shenzhihua/200903/0330_6016_1083438_8.shtml.

- a.Luo, P. H. (2015, February 6). Peasant protests over agricultural cooperatives and grain shortages in 1956-1957. People’s Network - Communist Party of China News Network. Retrieved from http://dangshi.people.com.cn/n/2015/0206/c85037-26521396.html. b.Luo, P. H. (2014, July 25). How did rural public canteens emerge in 1958? People’s Network. Party History Literature. http://dangshi.people.com.cn/n/2014/0717/c85037-25291778.html (Original content archived on April 5, 2021).

- Xiao, D. L. (2008, December 8). Peasants’ choices made China’s reform: A historical perspective on the overall significance of rural reform. aisixiang.com. Retrieved from https://www.aisixiang.com/data/23050.html.

- Song, Y. Y. (n.d.). China’s Great Leap Forward - Great Famine Database (1958-1962). Harvard University & The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved from https://cup.cuhk.edu.hk/chinesepress/promotion/Great_Famine/great_femine_sc.htm (Original content archived April 29, 2014)Note: The database contains over 7,000 archival materials (over 20 million Chinese characters), including more than 3,000 internal archives of the Communist Party of China.

- Communist Party of China News Network. (2022, May 25). Completion of the socialist transformation. Communist Party of China News Network. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20220618101213/http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/33837/2534775.html (Original content archived June 18, 2022).

- Cheng, C. Y. (2008, November 21). The historical inevitability and profound significance of peaceful redemption. Institute of Political Science, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Retrieved from http://chinaps.cass.cn/bxpsh/201506/t20150618_2361361.shtmlNote: "Four-Part Profit Distribution" was a policy of the Communist Party of China for profit allocation in private capitalist enterprises during the socialist transformation period. Its core was to distribute enterprise profits into four parts: state income tax, enterprise public reserve funds, employee welfare bonuses, and capitalists’ profits. In the later stage of socialist transformation, capitalists’ profits were gradually replaced by fixed interest.

- Liu, Y. J. (2012, June 20). Dispute over Wanglaoji from a historical perspective. aisixiang.com. Retrieved from https://www.aisixiang.com/data/54560.html.

- Southern Metropolis Daily. (2009, June 3). Descendants of Chen Liji claim ancestral property on Beijing Road, Guangzhou. Southern Metropolis Daily. Retrieved from http://epaper.oeeee.com/B/html/2009-06-03/content_809323.htm (Accessed September 8, 2012).

- WIST Quotations: William Pitt the Elder, https://wist.info/pitt-william-the-elder/40206/;William Pitt, the Elder.Britannica.https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Pitt-the-Elder.

- Zhao, Y. (2014, August 12). "Everything is subject to destruction": Private property and public property during the Cultural Revolution. The Paper - Ideas Market. Retrieved from https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1261079Note: Originally published in Yuedu Magazine, Issue 38.

- Zheng, D. H. (Ed.). (2004). Liang Shuming’s Autobiography (pp. 156-159). Zhengzhou, China: Henan People’s Publishing House. ISBN 7-215-05331-8.

- Bei, D., Cao, Y. F., & Wei, Y. (Eds.). (2012, March). Memories of the Storm: Beijing No. 4 Middle School, 1965-1970 (Chapter: "Witness Accounts", pp. 189-190). Beijing, China: SDX Joint Publishing Company. ISBN 978-7-108-04010-7.

- a.Gu, J. G. (2007). Gu Jiegang’s Diary (1964-1967) (Vol. 10, p. 516). Taipei, Taiwan: Linking Publishing Company. ISBN 9570830158. b.Gu, J. G. (2007). Gu Jiegang’s Diary (1964-1967) (Vol. 10, p. 526). Taipei, Taiwan: Linking Publishing Company. ISBN 9570830158. c.Gu, J. G. (2007). Gu Jiegang’s Diary (1964-1967) (Vol. 10, p. 546). Taipei, Taiwan: Linking Publishing Company. ISBN 9570830158.

- People’s Network. (2013, August 12). How many precious cultural relics were destroyed during the "Four Olds" campaign? People’s Network. (Source: Xinhua News Agency). Retrieved from https://art.people.com.cn/n/2013/0812/c206244-22525449.html.

- aisixiang.com. (2011, September 17). "Fruits" of Red Guard house raids during the Cultural Revolution: 40 billion yuan in cash. aisixiang.com. Retrieved from https://www.aisixiang.com/data/44344.html.

- a.Wikipedia. Three years of hardship period. Retrieved from:https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E5%B9%B4%E5%9B%B0%E9%9A%BE%E6%97%B6%E6%9C%9F.quote:Smil, V. (1999, December 18). China’s great famine: 40 years later. BMJ (British Medical Journal), 319(7225), 1619–1621. Xu, X. M. (1958). Searching for witnesses to cannibalism. Book News, 10, 319. (National Institute for Compilation and Translation);Liu, Z. K. (2008). A review and interpretation of research on "abnormal population deaths" during China’s great famine (PDF). Twenty-First Century, 77. https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ics/21c/media/online/0805050.pdf. b.Wikipedia. Three years of hardship period. Retrieved from:https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E5%B9%B4%E5%9B%B0%E9%9A%BE%E6%97%B6%E6%9C%9F.quote:Johnson, I. (2012, November 22). China: Worse than you ever imagined. The New York Review of Books.https://web.archive.org/web/20131017225914/http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/nov/22/china-worse-you-ever-imagined/?page=2;Tatlow, D. K. (2012, September 17). Documenting the tragedy of cannibalism during the great famine. The New York Times (Chinese Edition). https://cn.nytimes.com/china/20120917/c17famine/;Yan, L. B. (2012, May 23). The years of great famine in Guizhou. Yanhuang Chunqiu. https://web.archive.org/web/20220126115127/http://www.hybsl.cn/beijingcankao/beijingfenxi/2012-05-23/29803.html;Yang, J. S. (2008). The Tongwei problem: Commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Great Leap Forward. Yanhuang Chunqiu, 10, 42–48;Anonymous. (2014, July 14). Eyewitness accounts of cannibalism in every commune of Boxian during the three years of hardship. China Taiwan Net. https://web.archive.org/web/20150109120035/http://www.china.com.cn/zhibo/content_39343158.htm;Shi, S. (2013, November 21). Official documents expose "cannibalism". Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/shehui/xql-11212013143103.html. [CrossRef]

- Ding, S. (n.d.). Human Disaster [Chinese]. In China Great Famine Archives. Nineties Magazine Press. (Original content archived October 5, 2013).

- Deng Xiaoping: "Developing Democracy Politically and Implementing Reforms Economically", Source: Qiushi Network, Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, Volume 3, July 31, 2019.

- Gao, Y. (2018, July 4). History chose Deng Xiaoping (56): Rural reform promoted the dissolution of the people’s commune (2). People’s Network. https://cpc.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0704/c69113-30124221.html (Original content archived on November 14, 2023).

- Wen, G. Z. (2009). Causes of the outbreak and aggravation of China’s three-year great famine: On the murderous consequences of public canteens without the right to exit. Journal of Modern China Studies, (1). https://www.modernchinastudies.org/cn/issues/past-issues/103-mcs-2009-issue-1/1082-2012-01-05-15-35-41.html (Original content archived on June 22, 2020).

- Yang, D. L. (1998). From the Great Leap Forward famine to rural reform (PDF). 21st Century Bimonthly, (48). https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ics/21c/media/articles/c048-199807003.pdf (Original PDF archived on December 9, 2023).

- Phoenix Network & Xinhua News Agency. (2008, August 29). A correct understanding of the history of the people’s commune.(Original content archived on March 12, 2015). https://news.ifeng.com/history/2/shidian/200808/0829_2666_754201.shtml.

- Xin, Y. (2009, June 7). Twenty years of research on the people’s commune. Aisixiang. https://www.aisixiang.com/data/27813.html (Original content archived on June 29, 2022).

- Huang, X. T. (2007). Section 4: Social impact. In Introduction to psychology (2nd ed.). People’s Education Press. ISBN 9787107204531. (Original content archived on December 25, 2013). https://web.archive.org/web/20131225190930/http://bbs.sciopsy.com/viewthread.php?action=printable&tid=23322.

- Zhou Jingwen: Chapter 10 of "Ten Years of Storm" - The People’s Hell (Part 2) - The "People’s Communes" bring greater disasters to the people Hong Kong Times Criticism Society. 1959. Marxist Library.(Original content archived on October 25, 2019) (Chinese) https://www.marxists.org/chinese/reference-books/zjw1959/10.htm#3.

- Chinese Society of the History of the Communist Party of China. (2019). A series of dictionaries on the history of the Communist Party of China. CPC History Press & Party Building Reading Material Press.

- Mu, G. R. (n.d.). Six sections of the Anti-Rightist Movement. Yanhuang Chunqiu. https://web.archive.org/web/20200223133653/http://www.yhcqw.com/31/8067.html (Original content archived on February 23, 2020).

- Guo, D. H. (2009). Mao Zedong’s original intention of launching the rectification movement. Hu Yaobang Historical Materials Information Network. Yanhuang Chunqiu. https://web.archive.org/web/20210720064545/http://www.hybsl.cn/beijingcankao/beijingfenxi/2009-02-24/12773.html (Original content archived on July 20, 2021).

- Condensing: Fifty Years of the Anti Rightist Movement: Can China Break Out of the Shadow of History The Voice of Germany 2007-06-08. (Original content archived on November 20, 2022) (Chinese)https://www.dw.com/zh/%E5%8F%8D%E5%8F%B3%E8%BF%90%E5%8A%A8%E4%BA%94%E5%8D%81%E5%B9%B4%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E8%83%BD%E5%90%A6%E8%B5%B0%E5%87%BA%E5%8E%86%E5%8F%B2%E7%9A%84%E5%BD%B1%E5%AD%90/a -2580534.

- Guanling: Mao Zedong sets targets: the historical tragedy of suppressing rebellion and opposing rightism Multidimensional news.2017-12-13. (Original content archived on August 6, 2021) (Chinese). https://web.archive.org/web/20210806094256/https://www.dwnews.com/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD/60029383/%E6%AF%9B%E6%B3%BD%E4%B8%9C%E5%88%92%E5%AE%9A%E6%8C%87%E6%A0%87%E9%95%87%E5%8F%8D%E4%B8%8E%E5%8F%8D%E5%8F%B3%E7%9A%84%E5%8E%86%E5%8F%B2%E6%82%B2%E5%89%A7.

- Chen, F. X. (2010, March 20). The limitations of the Rightists’ ideological understanding in 1957. Hu Yaobang Historical Materials Information Network; Consensus Network.(Original content archived on August 6, 2021). http://www.hybsl.cn/beijingcankao/beijingfenxi/2010-04-30/20068.html.

- Lei, X. (n.d.). "The ’rightist on home leave’ — my uncle". Chinese University of Hong Kong; Consensus Network. http://mjlsh.usc.cuhk.edu.hk/Book.aspx?cid=4&tid=2913 (Original content archived on August 6, 2016).

- People’s Network & United Front Work Department of the CPC Central Committee. (2006, June 7). The Anti-Rightist Movement and its expansion. (Original content archived on October 10, 2018).https://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64107/65708/65722/4444744.html.

- Wang, Y. Q. (2010, June 5). Seven Peking University "rightists" sentenced to death (PDF). University of Chicago; Traces of the Past. (Original PDF archived on February 23, 2020). https://ywang.uchicago.edu/history/docs/2010_05_00.pdf.

- Yuan Ling: The Five Famous Reeducation through Labor Camps of the Mao Zedong Era The Chinese University of Hong Kong The History of Boiling Water [2021-08-06]. http://mjlsh.usc.cuhk.edu.hk/Book.aspx?cid=4&tid=4568. (Original content archived on August 1, 2021) (Chinese).

- Li Su After 1949: Decades of Sports History in China Voice of America 2007-06-15.(Original content archived on November 8, 2022) (Chinese). https://www.voachinese.com/a/a-21-w2007-06-15-voa61-62985742/1037977.html.

- Lin, Yewang. "Four Types of People, Seven Categories of Elements, Nine Kinds of People, and Twenty-One Kinds of People" [Column: Old Words of the Past]. Southern Metropolis Daily, 09 Aug. 2007. Sina Entertainment, Archived on 17 Mar. 2024. https://ent.sina.com.cn/x/2007-08-09/11001669635.shtml.

- Li, Ruojian. "The Failure of Indicator Management: Official Fraud During the ’Great Leap Forward’ and the Difficult Period". Open Times, vol. 2009, no. 3, 2009. Universities Service Centre for China Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Archived on 29 Jun. 2020. http://ww2.usc.cuhk.edu.hk/PaperCollection/Details.aspx?id=7258.

- CCTV International. "Once Absurdity: From 7,320 Jin of Wheat per Mu to 130,000 Jin of Rice per Mu". Democracy and Legal System Times, 05 Feb. 2007. CCTV Discovery Channel, https://discovery.cctv.com/20070205/102433.shtml.

- Phoenix TV. "Memories of New China’s Slogans: ’Man’s Courage Determines the Output of the Land’". Phoenix News, 08 Oct. 2009. . Archived on 29 Jun. 2020. https://news.ifeng.com/history/phtv/tfzg/200910/1008_5714_1378619.shtml.

- Lin, Yunhui. "The Total Grain Procurement in Rural Areas During the Three Years of Hardship Was 20% More Than That in Normal Years". Tongzhou Gongjin, 13 Jul. 2012. Tencent News. Archived on 25 Feb. 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150225225701/http://view.news.qq.com/a/20120712/000010.htm.

- Xie, Xuanjun. "Civil Wars Across Two Centuries". Collected Works of Xie Xuanjun, Vol. 106, p. 508. https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=0fU8EAAAQBAJ&newbks=0&printsec=frontcover&pg=PA508&dq=%E5%85%A8%E5%B9%B4%E4%BC%B0%E8%AE%A1%E6%94%B6%E5%AE%B9%E8%BF%91200%E4%B8%87%E4%BA%BA&hl=en&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=%E5%85%A8%E5%B9%B4%E4%BC%B0%E8%AE%A1%E6%94%B6%E5%AE%B9%E8%BF%91200%E4%B8%87%E4%BA%BA&f=false.

- Ji, Peng. "Household Registration Differences During the Three Years of Hardship: Not Rich or Poor, But Life or Death". People’s Daily Online, 18 Oct. 2013. Archived on 04 Mar. 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160304102208/http://history.people.com.cn/n/2013/1018/c198452-23252124.html.

- Yin, Shusheng (Former Executive Deputy Director of the Public Security Department of Anhui Province). "Revealed: Why There Was No Large-Scale Unrest After the ’Great Leap Forward’?". People’s Daily Online, 07 Jan. 2015.Archived on 04 Mar. 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160304053311/http://history.people.com.cn/GB/205396/14398109.html.

- RFA Exclusive: "China’s ’Great Leap Forward’ and ’Great Famine’ Database" Recently Completed — Interview with Professor Song Yongyi (Part 1). [2014-04-29]. (Archived from the original on 2015-03-19). https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/zhuanlan/xinlingzhilyu/dayangliangan/mind-06242013102058.html.

- Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. "Overview of the Economy of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea". Website of the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, 20 Jul. 2010. http://kp.china-embassy.gov.cn/chn/cxgk/201007/t20100720_1089021.htm.

- Armstrong CK. The Destruction and Reconstruction of North Korea, 1950 - 1960. Asia-Pacific Journal. 2009;7(0):e8. [CrossRef]

- History of North Korea - Chapter 1b. b-29s-over-korea.com. [2018-10-29]. (The original content was archived on October 29, 2018). https://b-29s-over-korea.com/History_of_North_Korea/History-of-North-Korea-1b.htm.

- "Background Note: North Korea". United States Department of State.https://1997-2001.state.gov/background_notes/n-korea_0010_bgn.html.

- There are significant differences in estimates of the number of deaths due to famine in North Korea, ranging from 250000 to 3 million. But the latest data is generally estimated to be 500000 to 600000 people.Goodkind, D., West, L., & Johnson, P. (2011, March 28). A reassessment of mortality in North Korea, 1993–2008 (Population Division Working Paper No. 109). U.S. Census Bureau.https://paa2011.popconf.org/papers/111030.

- William J. Moon.(2009). The Origins of the Great North Korean Famine: Its Dynamics and Normative Implications. North Korean Review. 5. 10.3172/NKR.5.1.105.

- 83. Spoorenberg, Thomas; Schwekendiek, Daniel. Demographic Changes in North Korea: 1993–2008. Population and Development Review. 2012, 38 (1). ISSN 0098-7921. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. "Korea, Dem. People’s Rep. - Data". The World Bank, 29 Oct. 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/country/korea-dem-peoples-rep.

- a.Wikipedia. "Democratic People’s Republic of Korea" (in Chinese). Wikipedia, n.d. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%9D%E9%B2%9C%E6%B0%91%E4%B8%BB%E4%B8%BB%E4%B9%89%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD. Cited in Hassig, R., & Oh, K. The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom, p. 115. b.Wikipedia. "Democratic People’s Republic of Korea" (in Chinese). Wikipedia, n.d. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%9D%E9%B2%9C%E6%B0%91%E4%B8%BB%E4%B8%BB%E4%B9%89%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD. Cited in Hassig, R., & Oh, K. The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom, p. 126. c.Wikipedia. "Democratic People’s Republic of Korea" (in Chinese). Wikipedia, n.d. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%9D%E9%B2%9C%E6%B0%91%E4%B8%BB%E4%B8%BB%E4%B9%89%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD. Cited in Hassig, R., & Oh, K. The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom, p. 145. d.Wikipedia. "Democratic People’s Republic of Korea" (in Chinese). Wikipedia, n.d. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%9D%E9%B2%9C%E6%B0%91%E4%B8%BB%E4%B8%BB%E4%B9%89%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD. Cited in Hassig, R., & Oh, K. The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom, p. 198. e.Wikipedia. "Democratic People’s Republic of Korea" (in Chinese). Wikipedia, n.d. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%9D%E9%B2%9C%E6%B0%91%E4%B8%BB%E4%B8%BB%E4%B9%89%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD. Cited in Hassig, R., & Oh, K. The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom, pp. 202-204. f.Wikipedia. "Democratic People’s Republic of Korea" (in Chinese). Wikipedia, n.d. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%9D%E9%B2%9C%E6%B0%91%E4%B8%BB%E4%B8%BB%E4%B9%89%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD. Cited in Hassig, R., & Oh, K. The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom, pp. 199-202.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). "Over 10 Million People in the DPRK Are Malnourished, Accounting for Over 40% of the Total Population". HK01, Nov. 2020. https://www.hk01.com/article/697564?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral.

- Barbara Demick:"The unpalatable appetites of Kim Jong-il".《The Telegraph》.8.10.2011. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/northkorea/8809102/The-unpalatable-appetites-of-Kim-Jong-il.html.

- Kim Myong: The Injustice of North Korea’s Hereditary Leadership Succession as Demonstrated by the History of Power Transfer from Kim Il-sung to Kim Jong-il. February 16, 2021.Posted by HRNK(Committee for Human Rights in North Korea with No comments.

- World Report 2014: North Korea. Human Rights Watch. 2014-07-01. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2014/country-chapters/north-korea.

- ICNK welcomes UN inquiry on North Korea report, calls for action. International Coalition to Stop Crimes Against Humanity in North Korea. 2014-02-20 . http://www.stopnkcrimes.org/bbs/board.php?bo_table=statements&wr_id=54.

- Radio Free Asia reporter hopes: 1200 North Koreans imprisoned for watching Korean dramas, December 6, 2010 https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/chaoxian-12062010170650.html.

- Korean media reported that dozens of North Koreans were executed by firing squad for watching smuggled South Korean dramas. (2013, November 12). Retrieved from https://news.sina.com.cn/w/2013-11-12/140828688829.shtml, Source: Yangtze Evening Post.

- Mackenzie, Jean (BBC Correspondent Based in Seoul). "North Korea Opens to Western Tourists for the First Time After Five Years of Border Closure: First Tourists Share Their Rason Trip with BBC". BBC News, 03 Mar. 2025.

- Amnesty International. Our Issues, North Korea. Human Rights Concerns. 2007 [2007-08-01].Wayback Machine. http://www.amnestyusa.org/countries/north_korea/index.do.

- Kang, Hyok, & Grangereau, Philippe. This is Paradise!: My Childhood in North Korea. Trans. by Chen Yihua. Chapter 5: "Survival!: ’Stealing is a Matter of Life and Death’". Taipei: Weicheng Publishing, n.d. ISBN 9789868729506.

- Human Rights Watch (HRW). "You Weep Unknowingly at Night": Widespread Sexual Violence Against Women in North Korea. 01 Nov. 2018. https://www.hrw.org/zh-hans/report/2018/11/01/323617.

- Andrei Lankov(2007):"North of the DMZ: Essays on Daily Life in North Korea".Part 4. The Workers’ Paradise? The Social Structure of the DPRK."A Rank System".PP.66-69, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.ISBN: 978-0-7864-2839-7.

- Colin F.Camerer(2003).Behavioral Game Theory:Experiments in Strategic Interaction,New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Henrich J, Boyd R, Bowles S, Camerer C, Fehr E, Gintis H, McElreath R, Alvard M, Barr A, Ensminger J, Henrich NS, Hill K, Gil-White F, Gurven M, Marlowe FW, Patton JQ, Tracer D. "Economic man" in cross-cultural perspective: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behav Brain Sci. 2005 Dec;28(6):795-815; discussion 815-55. PMID: 16372952. [CrossRef]

- Editorial Committee of Encyclopedia of Major Political Events. Encyclopedia of Major Political Events: A Global Compilation of Coups and Military Mutinies (Volume II). Hefei: Anhui People’s Publishing House, 2003 (1st ed.). ISBN 978-7-212-02182-5.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).