Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

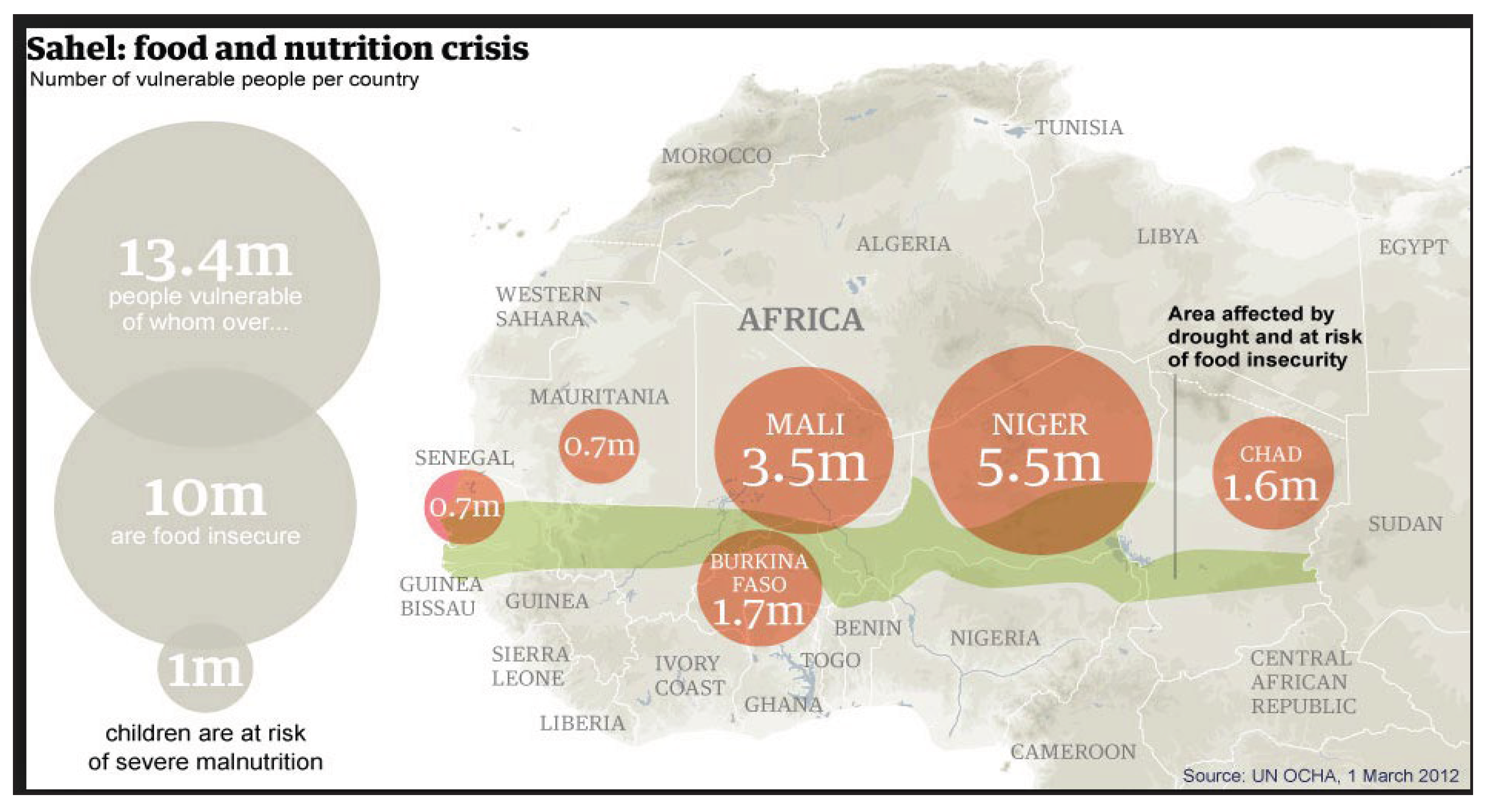

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

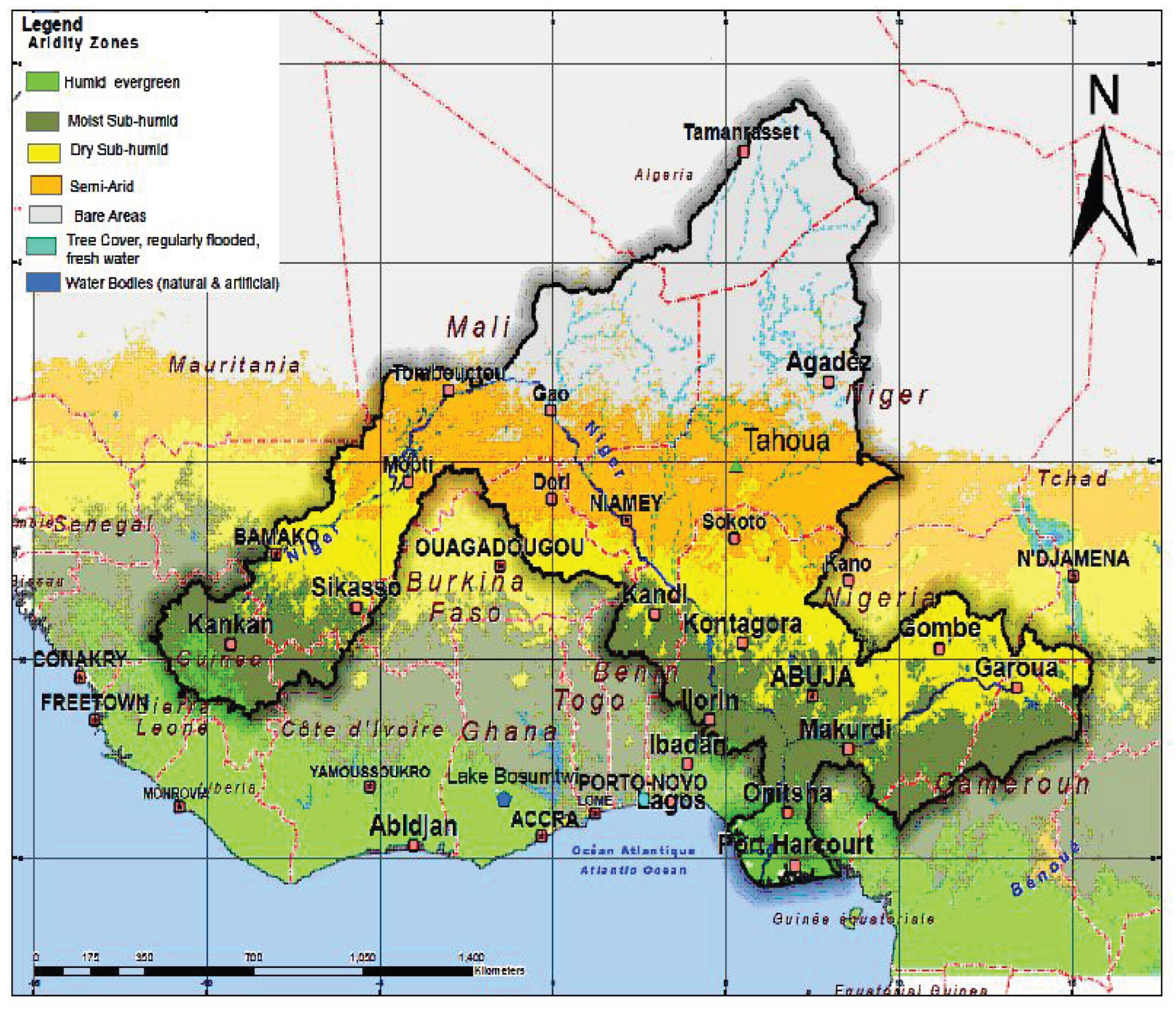

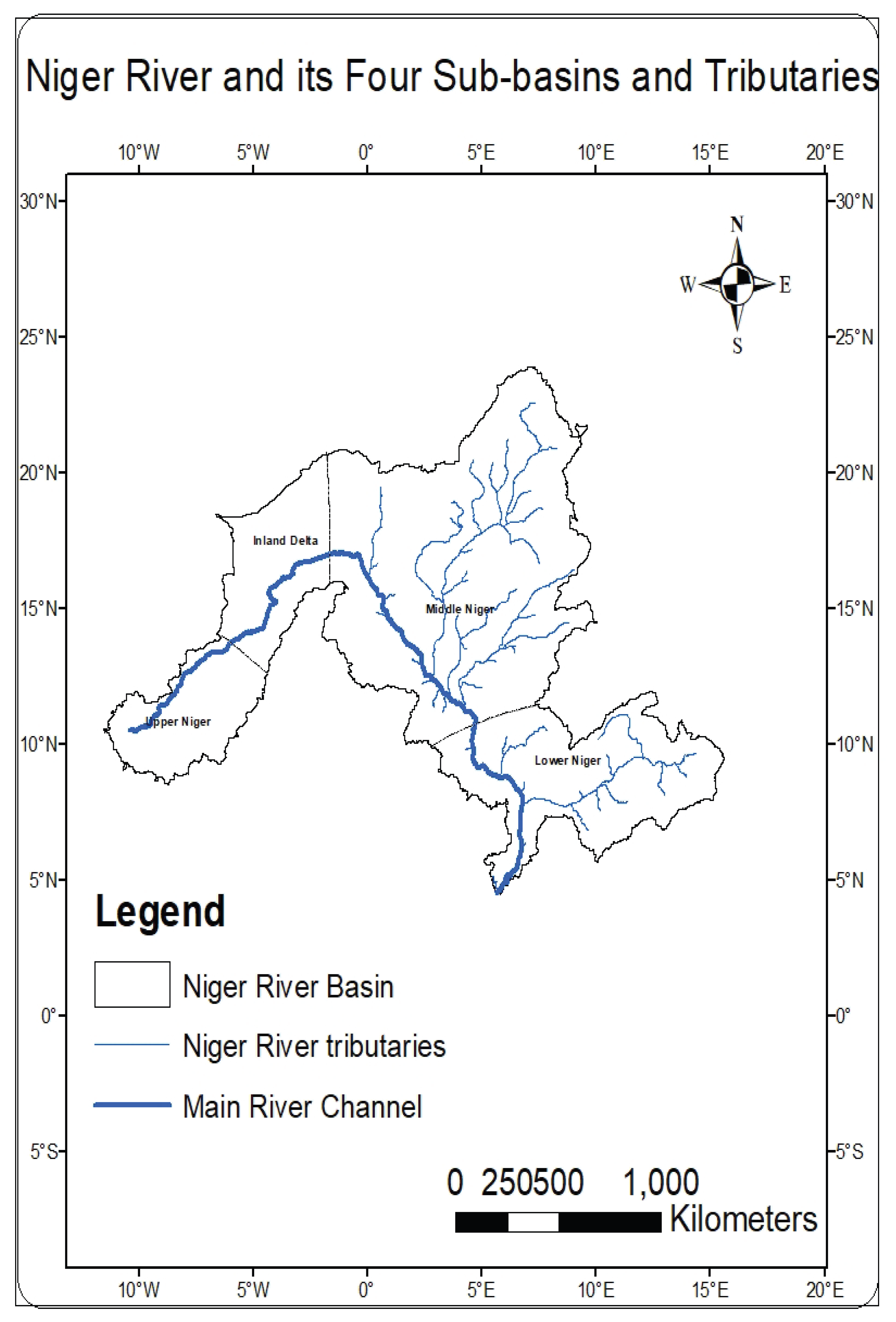

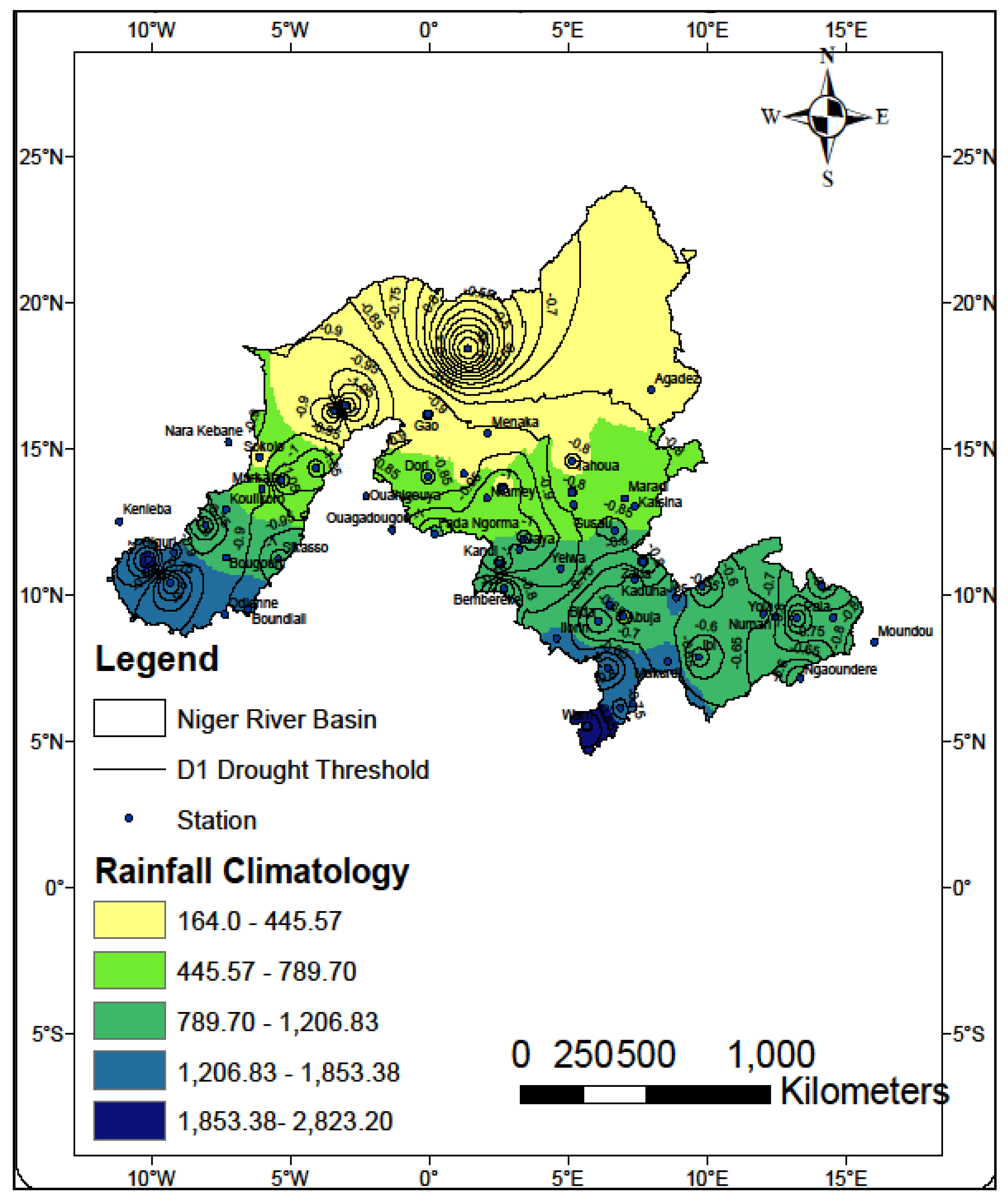

2.1. Study Area

2.2. The Reanalysis Data

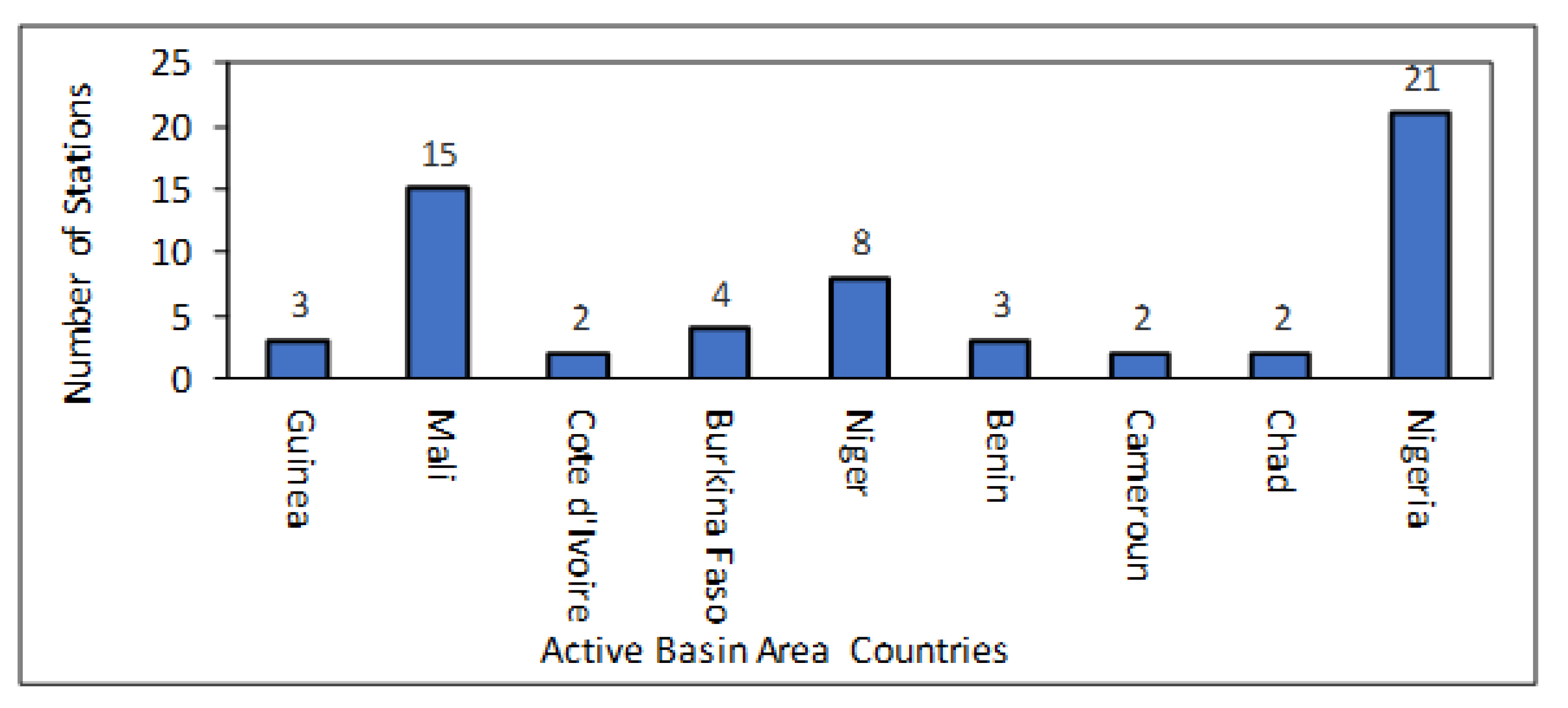

2.3. In-situ Observational Station and Ancillary Data

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Data Quality Control: Bias Correction of Reanalysis Dataset

2.4.2. Understanding the Climatology of Niger River Basin Based on Station Data

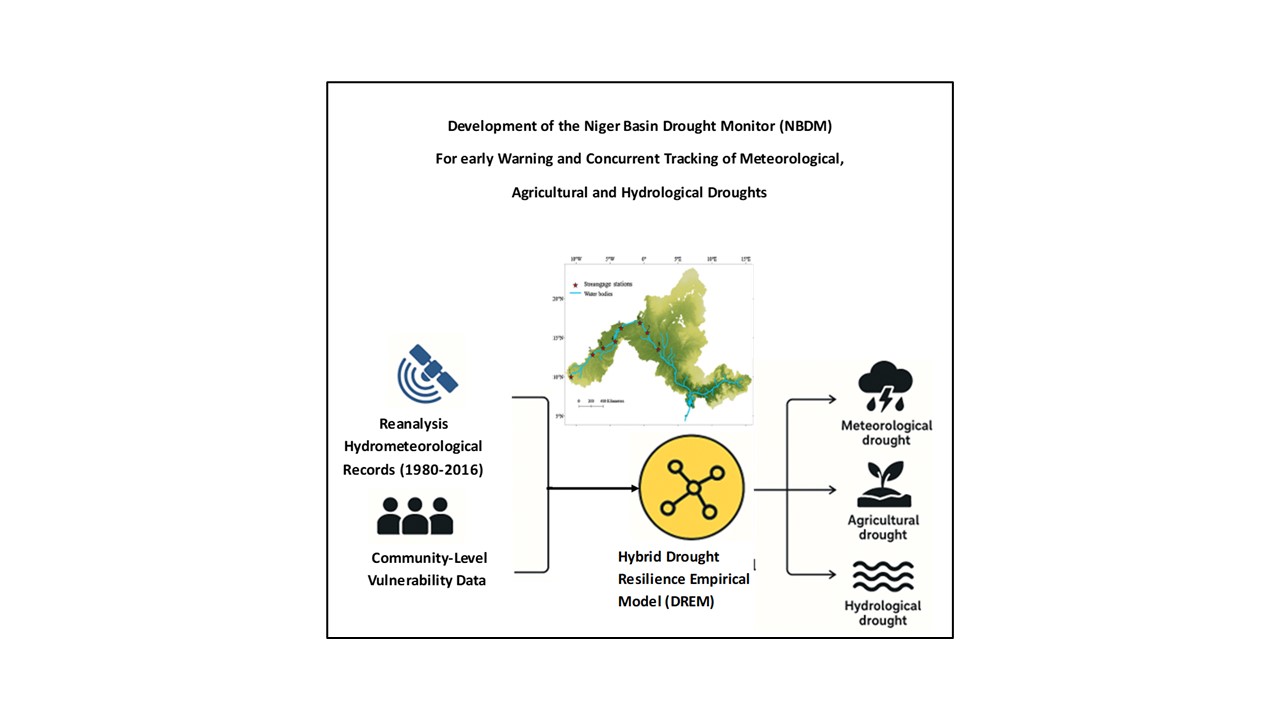

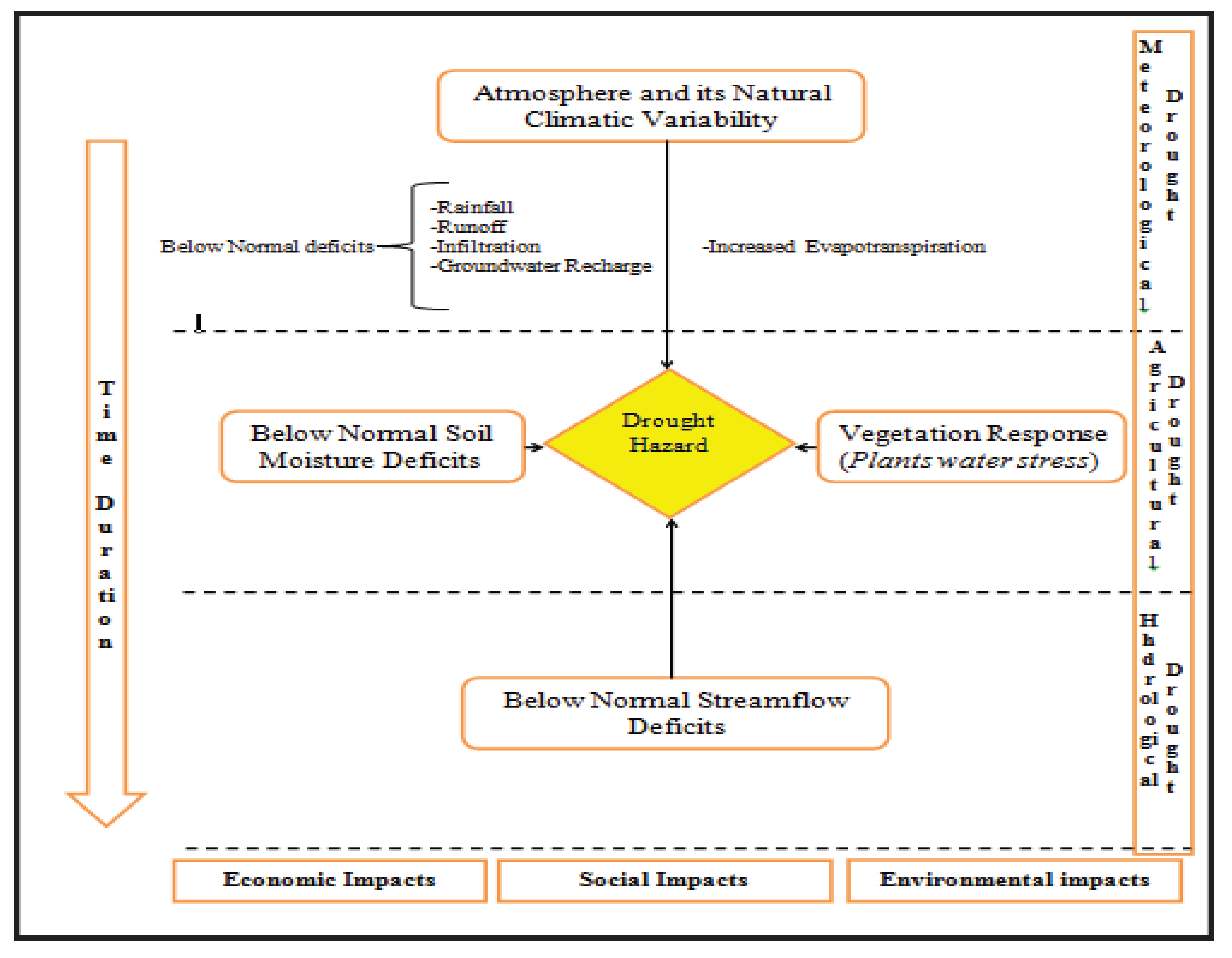

2.4.3. Conceptual Framework of Design of Niger Basin Drought Monitor (NBDM)

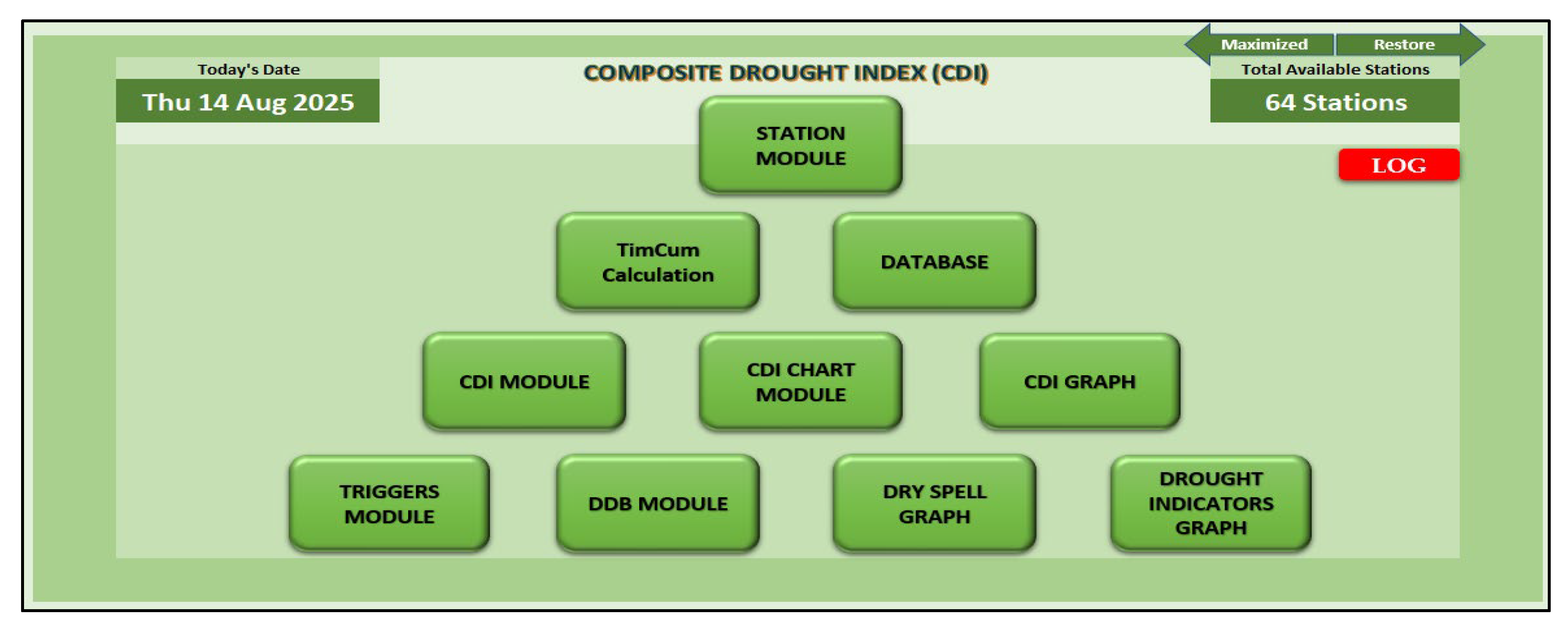

2.4.4. The Development Process of the Niger Basin Drought Monitor (NBDM)

2.4.5. Description of the General Methodological Framework of NBDM Development

- i.

- The input data module: It comprises all the hydrometeorological monthly data used in the analysis, which includes precipitation, temperature soil moisture and streamflow. Hence, the database contains 60 stations with 4 different parameters as highlighted above.

- i.

- ii. The potential evapotranspiration (PET) computation module: It consists of two different approaches for computing the PET for the purpose of comparison of results. They are the Thornthwaite Method and Hargreaves and Samani method using Mean surface air temperature, maximum and minimum temperatures.

- i.

- The drought indicators standardization module: It uses percentile method to transform all input data into a standardized scale. To achieve this, two options were considered, the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) model approach [4], if the indicator measurement was in international system unit (i.e., S.I unit), or the Normal Curve Equivalent (NCE) method, if the unit of measurement of the indicator was in percentile. The SPI model was selected because of its widespread acceptance and recognition as the standard index for the monitoring of drought events [85].

- ii.

- The dry spell and Drought conditions triggers module: It comprises the various drought definition or drought initiation (onset) thresholds for each of the respective indices considered in this study, namely, SPI, SEPI, SMI, SFI and CDI. It also consists of the threshold(s) for the phase change or transition from dry spell to actual drought phase.

- ii.

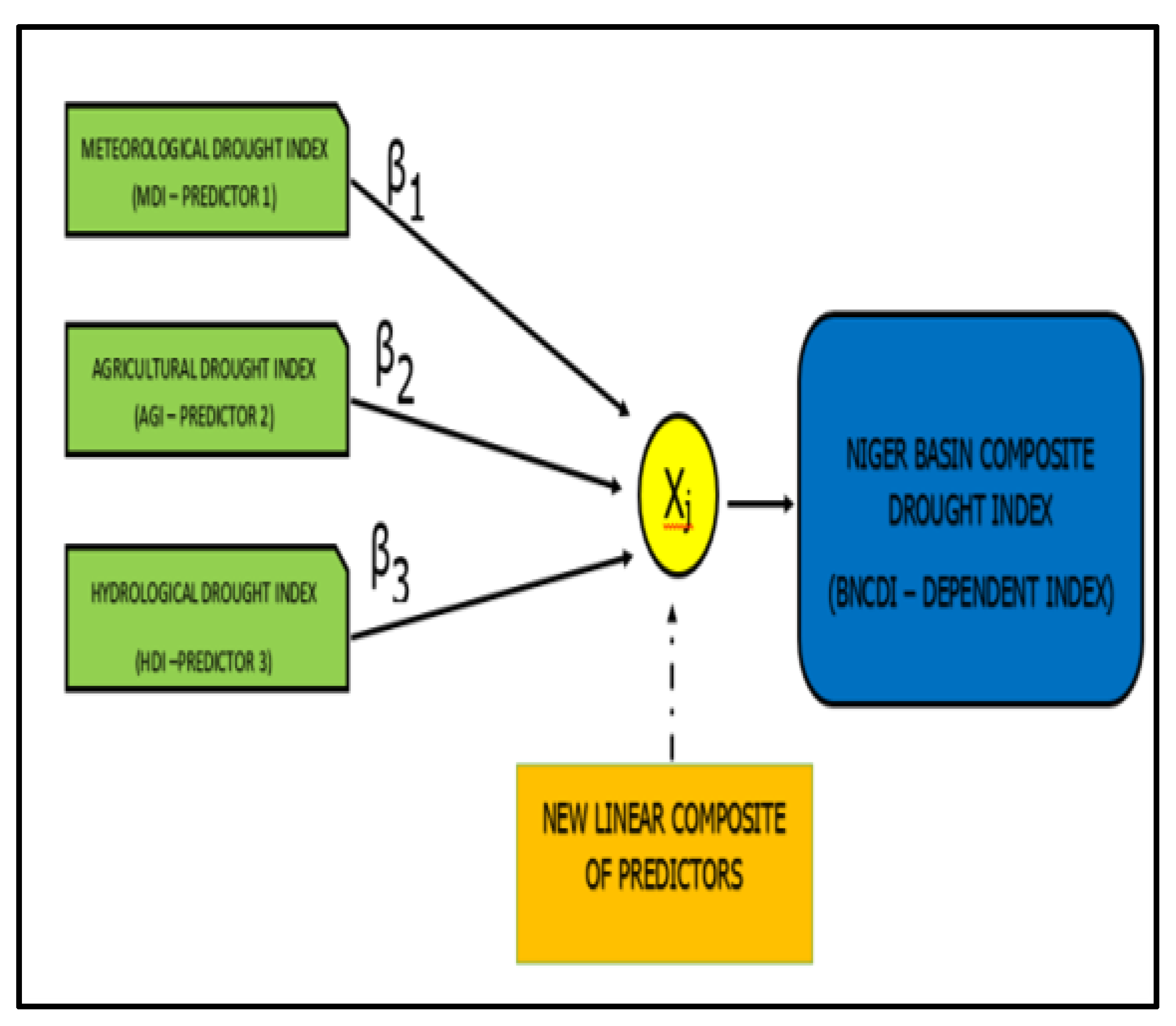

- iii. Objective Blend of Burden of Drought Indices (OBBDI) Module: It determines first the relative weight of the impacts of each type of droughts (i.e., meteorological, agricultural and hydrological droughts) on the society based on available drought disaster damage indicators, then, thereafter, established the OBBDDI hinged on the concept of drought disaster burden (DDB) resulting from exposure of the society to different biophysical forms of drought events.

- ii.

- iv. The last module is the integrated dry spell and drought detection module: It identifies and categorizes the severity of the detected drought events using the established thresholds.

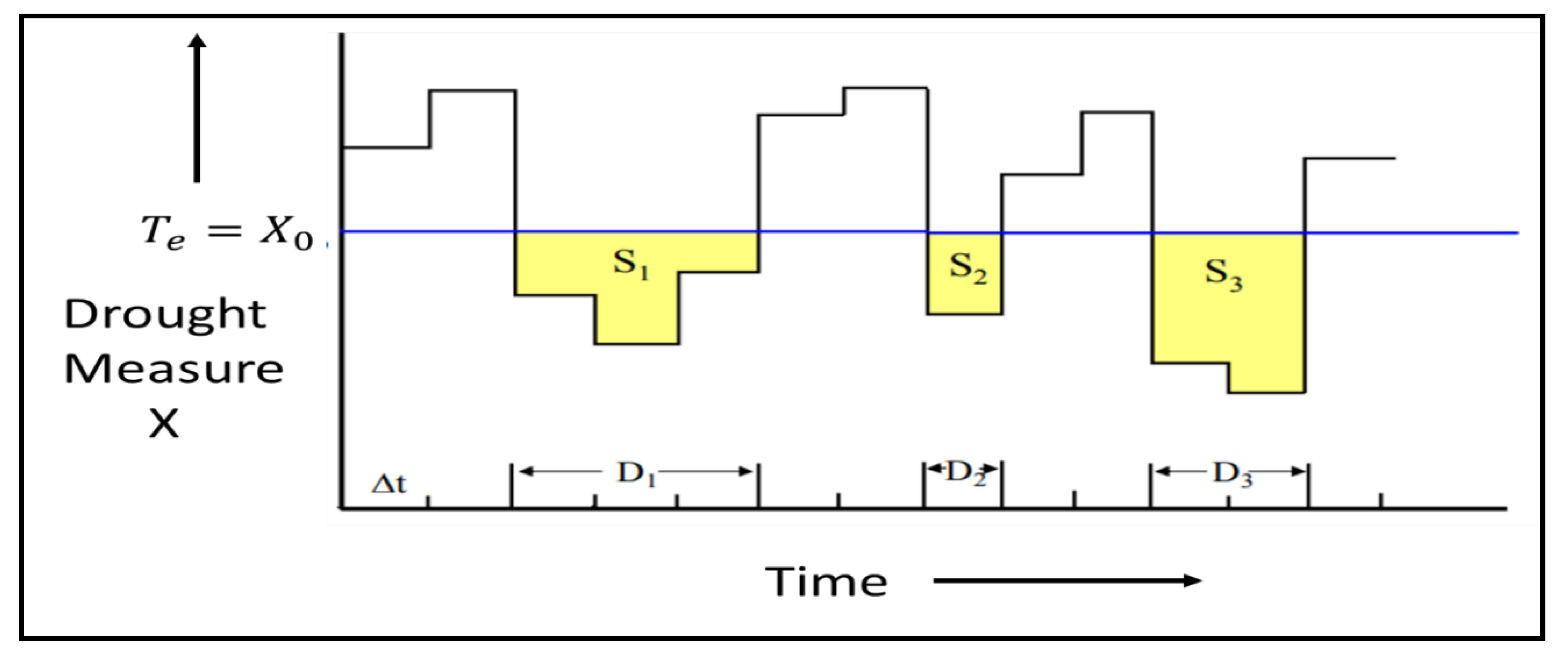

2.4.6. Determination of Percentile-based Drought Threshold

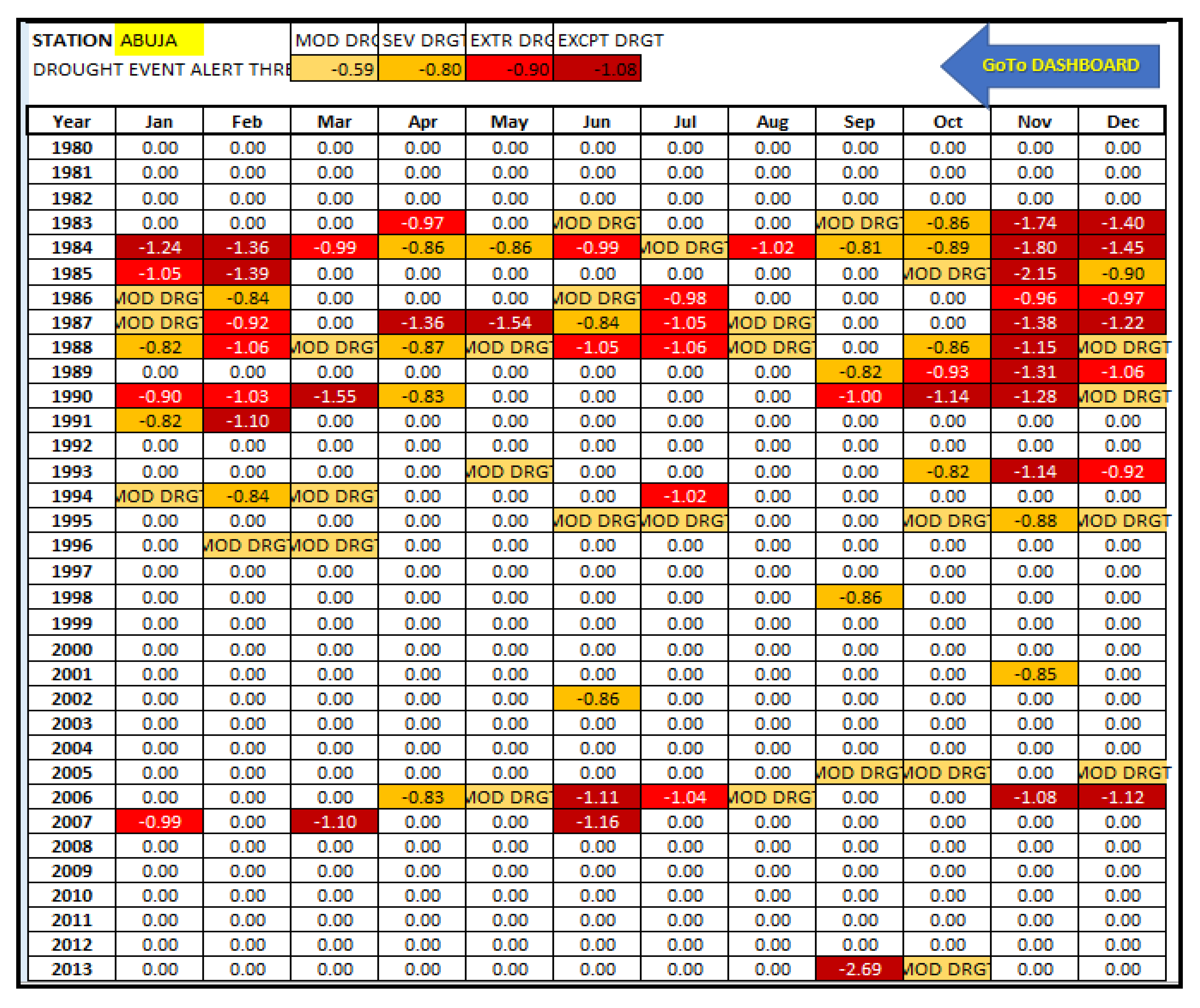

2.4.7. Operational Application of the Established Drought Definition Thresholds

2.4.8. NBDM As Visual Basic Application-Driven Drought Early Warning System (DEWS)

2.4.9. Evaluation of Performance of NBDM Outputs

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Development Outputs

3.2. Thresholds and Detection of Drought Onset and Cessation

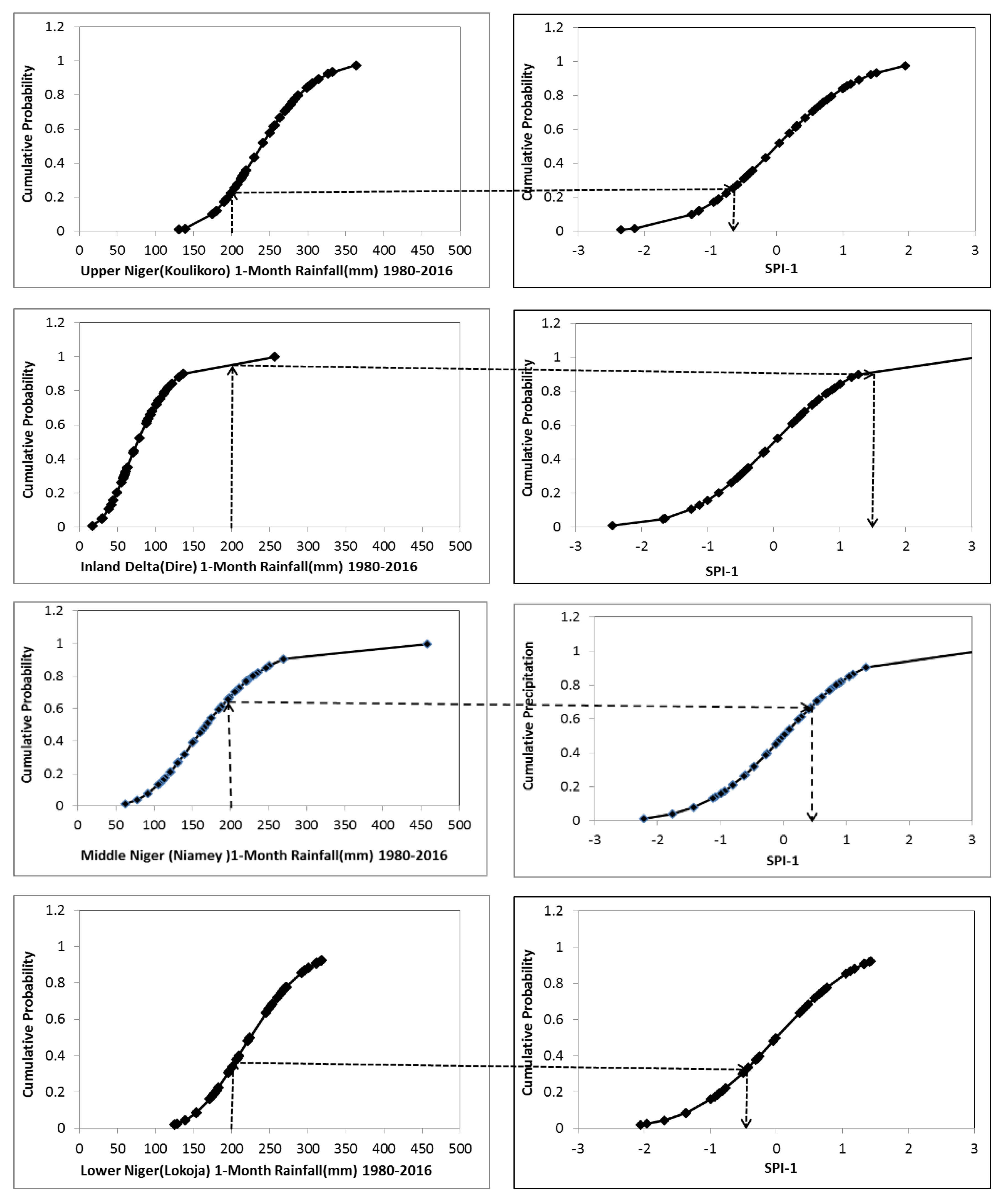

3.3. Equiprobability Transformation Analysis for Drought Detection

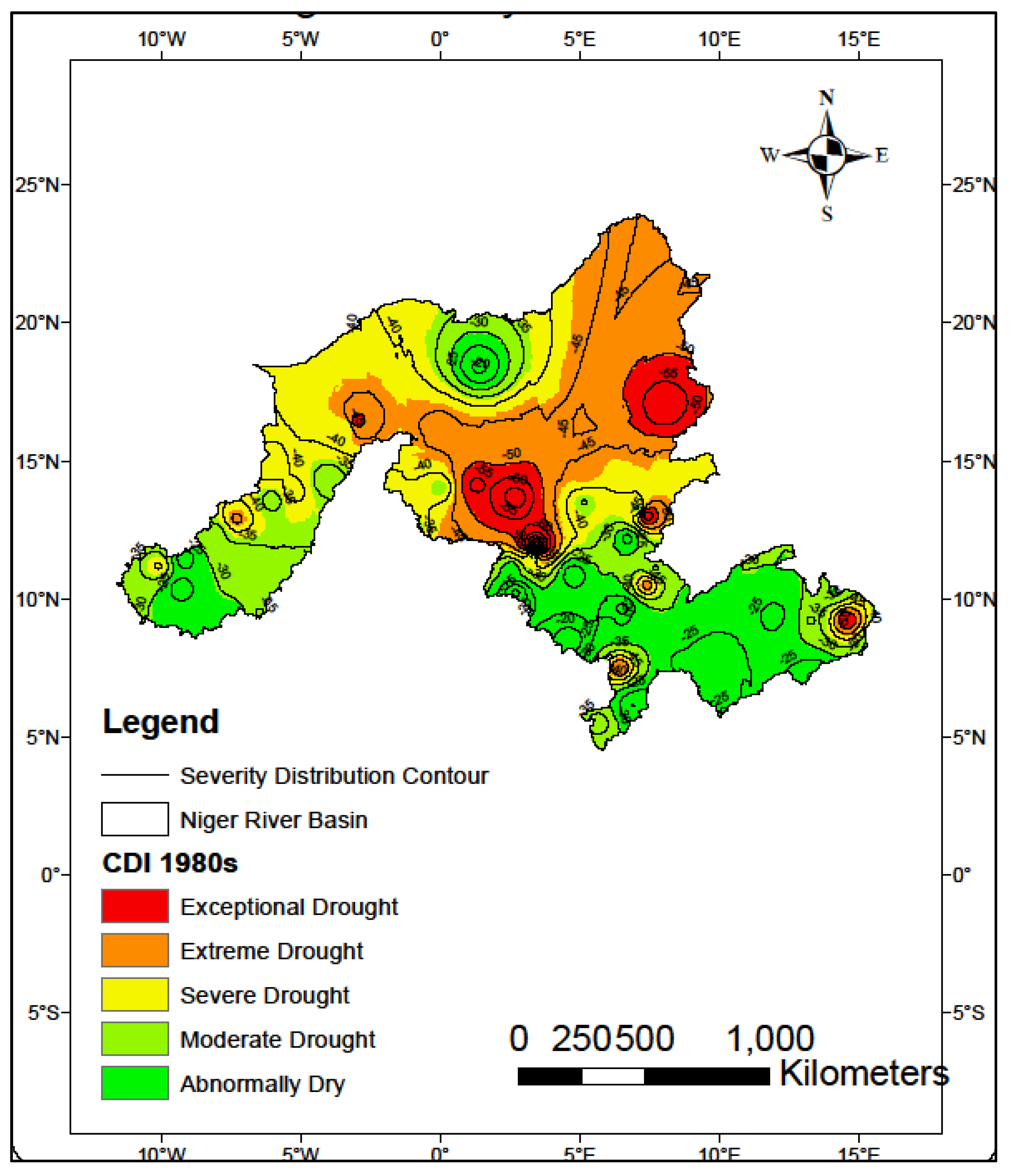

3.4. Spatial Characteristics of the Major Droughts of 1980s in the Niger Basin

3.5. Effectiveness in Early Detection and Cessation of Drought

3.6. NBDM-CDI Performance Evaluation

3.7. Calibration / Validation of Performance of NBDM CDI

3.7. Comparison Between USDM and NBDM

4. Conclusions

- i.

- The Niger Basin Drought Monitor (NBDM) has been developed to effectively integrates three hydrometeorological indicators, precipitation, soil moisture, and streamflow to provide a single ‘average’ drought designation at station level with the intent to have a composite drought index (CDI) that captures local drought conditions.

- ii.

- The percentile rank approach was used to transform first all input datasets into a standardized scale to which drought category thresholds and weights for each individual index was assigned. The CDI-based thresholds of range −0.26 to −1.19 for defining drought of moderate intensities were established and found to be consistently higher than the single variable SPI-based ones, implying earlier detection of any impending drought for a given rainfall deficit.

- iii.

- In terms of evaluation of the NBDM-CDI, high Nash Sutcliff Efficiency and index of agreement values show NBDM-CDI tracks soil moisture and streamflow drought well.

- iv.

- The model validation showed 67–100% success with historical drought events captured by NBDM-CDI and 62–77% with ENSO-related droughts captured by NBDM-CDI. Also, NBDM-CDI time series were further validated sub-basin-wise against the Standardized NDVI (SNDVI), the result further confirms the close relationship between soil moisture and vegetation health in arid and semi-arid areas.

- v.

- The NBDM offers a robust all-in-one drought early-warning tool for the basin region and therefore, being recommended for use as drought alert triggers in decision-making, and early warning in the Niger Basin.

Author Contributions

References

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland,2023 pp. 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Okpara J.N., Afiesimama E.A., Anuforom A.C., Owino A., Ogunjobi K.O. The applicability of standardized precipitation index: drought characterization for early warning system and weather index insurance in West Africa. Nat Hazard 2017, 89(2):555–583.

- Sarr B. Present and future climate change in the semi-arid region of West Africa: a crucial input for practical adaptation in agriculture. Atmos Sci Lett, 2012, 13:108–112. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1002/ asl. 368.

- Okpara, J. N., K. O. Ogunjobi and · E. A. Adefisan. Developing objective dry spell and drought triggers for drought monitoring in the Niger Basin of West Africa. Natural Hazards 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wilhite D. A. Drought monitoring, mitigation, and preparedness in the United States: an end-to-end approach, paper presented at the task force on socio-economic application of public weather services. WMO, Geneva, 2006.

- World Meteorological Organization. High level meeting on national drought policies. 2013. towards more drought resilient societies. Geneva, 11–15 March 2013 [online]. http://www.wmo.int/pages/prog/wcp/drought/hmndp/index.php (citation 20 Nov 2020).

- Benson, C. and Clay, E. The Impact of Drought on Sub-Saharan African Economies. World Bank Technical Paper No. 401, The World Bank, Washington DC, 1998, 80 p.

- Tarhule, A. Damaging Rainfall and Flooding: The Other Sahel Hazards 2005, Volume 72, pages 355–377.

- Boyd, E., Rosalind, J.C., Lamb, P.J., Tarhule, A., Lele M.I. & Brouder, A. Building resilience to face recurring environmental crisis in African Sahel. Nature, Climate Change, 2013, 3, 631–637.

- FAO. The Sahel crisis executive brief, 2012.

- UN-OCHA. Sahel Drought Crisis Humanitarian Update, 2011.

- Konapala, G., Mishra, A. K., Wada, Y. and Mann, M.E. Climate change will affect global water availability through compounding changes in seasonal precipitation and evaporation. Nature Communications 2020, 11(1) 3044 . [CrossRef]

- Condon, L.E., Atchley, A. L. and Reed M. Maxwell, R.M. Evapotranspiration depletes groundwater under warming over the contiguous United States. Nation Communications 2020, 11:873 . [CrossRef]

- Findell, K.L., Keys, P.W., Van Der Ent, R.J., Lintner, B. R., Berg, A. L., and Krasting, J. O. Rising Temperatures Increase Importance of Oceanic Evaporation as a Source for Continental Precipitation. Journal of Climate. Journal of climate 2019, vol 32. [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). State of Climate Services Report.2024.

- Tegegne, G., and Melesse, A.M. Quantifying Spatiotemporal Drought Dynamics Under Climate Change in the Abbay River Basin, Ethiopia. In: Melesse, A., Gessesse, B., Zewdie, W. (eds) Abbay River Basin. Springer Geography. Springer, Cham.2025 . [CrossRef]

- Wilhite D. A. Drought: a global assessment. Ed. Routledge, London, 2000.

- Li, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, F. Improved Agricultural Drought Monitoring with an Integrated Drought Condition Index in Xinjiang, China. Water 2024, 16, 325. [CrossRef]

- Fowé, T.; Yonaba, R.; Mounirou, L.A.; Ouédraogo, E.; Ibrahim, B.; Niang, D.; Karambiri, H.; Yacouba, H. From meteorological to hydrological drought: A case study using standardized indices in the Nakanbe River Basin, Burkina Faso. Nat. Hazards 2023, 119, 1941–1965.

- Le, H.M., et al., 2019. A Comparison of Spatial–Temporal Scale Between Multiscalar Drought Indices in the South-Central Region of Vietnam, Spatiotemporal Analysis of Extreme Hydrological Events. Elsevier 2019, pp. 143–169.

- Abubakar, Muhammad & Abdussalam, Auwal & Ahmed, Muhammad & Wada, Amina. (2024). Spatiotemporal variability of rainfall and drought characterization in Kaduna, Nigeria. Discover Environment 2024, 2. 72. 10.1007/s44274-024-00112-7.

- Dinsa, A.B., Wakjira, F.S., Demmiese, E. T., and Negash, T.T. Forecasting Seasonal Drought Using Spatio-SPI and Machine Learning Algorithm: The Case of Borana Plateau of Southern Oromia, Ethiop J Earth Sci Clim Change 2023, vol 14, issue 8.

- Agwata J. A review of some indices used for drought studies. Civil Environ Res 2014, 6: 14-21.

- Tsakiris, G., Pangalou, D. and Vangelis, H. Regional Drought Assessment Based on the Reconnaissance Drought Index (RDI). Water Resource Management 2007, 21:821–833.

- Palmer W. C. Meteorological drought. US Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau, Washington, DC, 1965, p 18.

- McKee T.B., Doesken NJ, Kleist J.The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In: Proceeding of the ninth conference on applied climatology. American meteorological society, Boston,1993, pp 179–184.

- Vicente-Serrano S.M., Begueria S, Lopaz-Moreno J. I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J Clim 2010, 23:1696–1718.

- Wilhite, D. A., and Glantz, M. H. Understanding the drought phenomenon: the role of definitions. Water Int, 1985, 0:111–120.

- Keyantash, John. (2021). Indices for Meteorological and Hydrological Drought. Hydrological Aspects of Climate Change. 10.1007/978-981-16-0394-5_11.

- Sepulcre-Canto, G., Horion, S., Singleton, A., Carrao, H., and Vogt, J. Development of a Combined Drought Indicator to detect agricultural drought in Europe, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci.,2012, 12, 3519–3531. [CrossRef]

- Okpara J.N. and Tarhule A. Evaluation of drought indices in the Niger River Basin, West Africa. J Geogr Earth Sci 2015, 3(2):1–32.

- Bhalme HN, Mooley DA. Large scale droughts/floods and monsoon circulation. Monthly Weather Review 1980, 108(8): 1197–12.

- 2014; 33. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Climate Change Indicators in the United States, 2014.

- Zargar, A., R. Sadiq, B. Naser and F.I. Khan, A review of drought indices. Environmental Reviews 2011, 19:333–349.

- Heim Jr R.R. A Review of Twentieth Century Drought Indices Used in the United States. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 2002, 83(8): 1149-1165.

- Keyantash J.A., and Dracup J.A. The Quantification of Drought: An Evaluation of Drought Indices. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2002, 83: 1167-1180.

- Hayes, M., M. Svoboda, D. LeComte, K. Redmond, and P. Pasteris. Drought monitoring: new tools for the 21st century. In: Drought and Water Crises: Science, Technology, and Management Issues, Ed. D. Wilhite, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press 2005, pp. 53–69.

- Abaje I.B., Ati O.F., Iguisi E.O., Jidauna G. G. Droughts in the Sudano Sahelian ecological zone of Nigeria: implications for agriculture and water resources development. Glob J Hum Soc Sci, 2013, 13(2):12–23.

- Anderson, M.C. Hain, C., Pimstein, A., Mecikalski, J. R., and Kustas, W. P. Evaluation of Drought Indices Based on Thermal Remote Sensing of Evapotranspiration over the Continental United States. J. Climate, 2011, 24, 2025-2044. [CrossRef]

- Svoboda M, LeComte D, Hayes M, Heim R, Gleason K, Angel J, Rippey B, Tinker R, Palecki M, Stooksbury D., Miskus D., Stephens S. The drought monitor. Bull Am Meteor Soc.2002 83:1181–1189.

- He, X., Estes, L., Konar, M., Tian, D., Anghileri, D., Baylis, K. Integrated approaches to understanding and reducing drought impact on food security across scales. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2019, 40, 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Y., G. Gao, P. Q. Zhang and Yan, X. The modification of meteorological drought composite index and its application in Southwest China. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 2011, 22, 698–705. (in Chinese).

- Sepulcre-Canto, G., Horion, S., Singleton, A., Carrão, H., Vogt, J., 2012 Development of a Combined Drought Indicator to detect agricultural drought in Europe. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2012,12, 3519-3531.

- Balint, Z., Mutua, F., Muchri, P., & Omuto, C. T. Monitoring drought with the combined drought index in Kenya. Development in earth surface Processes,2013, Vol. 16, 341-355.

- Garba, I.; Abdourahamane, Z.S.; Mirzabaev, A. A Drought Dataset Based on a Composite Index for the Sahelian Climate Zone of Niger. Data 2023, 8, 28. https:// doi.org/10.3390/data8020028.

- Hayes, M., The Newsletter of the National Drought Mitigation Center, 2014.

- Bijaber, N., Hadani, D. Saidi, M., Svoboda, M.D. Wardlow, B.D., Hain, C.R., Poulseen, C.C. Yessef, M., and Rochd, A. Developing a Remotely Sensed Drought Monitoring Indicator for Morocco. Geosciences, 2018, 8, 55; [CrossRef]

- Nam, W. H., Tadesse, T., Wardlow, B. D., Hayes, M. J., Svoboda, M. D., Hong, E. M., . Developing the vegetation drought response index for South Korea (VegDRI-SKorea) to assess the vegetation condition during drought events. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2018, 39(5), 1548–1574.

- Pulwarty, R.S. and Sivakumar, M.V.K. Information systems in a changing climate: Early Warnings and drought risk management. Weather and Climate Extremes,2014, 3: 14-21.

- Oguntunde P. G., Abiodun B. J., Lischeid G., Abatan A. A. Droughts projection over the Niger and Volta River basins of West Africa at specific global warming levels. J Climatol 2020:1–12. https:// doi. org/ 10.1002/ joc. 6544.

- Quenum, G.M.L.D.,Klutse, N.A.,Alamuo, E.A., Lawin, E. A. Oguntunde, P.G. Precipitation variability in West Africa in the Context of Global Warming and Adaptation recommendations African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation, pp 1533-1554, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Quenum, G.M.L.D., Klutse, N.A.B., Dieng, D., Laux, P., Arnault, J., Kodja, J.D., Oguntunde, P.G. Identification of potential drought areas in west Africa under climate change and variability. Earth Syst. Environ., 2019 3, 429–444.

- Karavitis, C. A. Decision support systems for drought management strategies in metropolitan Athens. Water International 1999a 24(1), 10–21.

- Tadesse, T., J.F. Brown, and M.J. Hayes. A new approach for predicting drought-related vegetation stress: Integrating satellite, climate, and biophysical data over the U.S. central plains. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2005, 59(4):244–253.

- Tadesse, T., Haile, M., Senay, G., Knutson, C., and Wardlow, B.D. Building integrated drought monitoring and food security systems in sub-Saharan Africa. Natural Resources Forum 2008, 32(4):245–279.

- Masih I., Maskey, S., Muss, F.E.F., Trambaue, P. (2014) A review of droughts on the African continent: a geospatial and long-term perspective. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2014, 18:3635–3649.

- World Bank. The Niger River Basin: A Vision for Sustainable Management. Edited by Katherin George Golitzen, 2005.

- Tarhule, A., Zume, J.T., Grijsen, J., Talbi-Jordan, A., Guero, A., Dessouassi, R.Y., Doffou, H., Kone, S., Coulibaly, B., Harshadeep, N. R. Exploring temporal hydroclimatic variability in the Niger Basin (1901–2006) using observed and gridded data. Int J Climatol 2014, 35:520–539.

- Oladipo, E. O. A Comparative Performance Analysis of Three Meteorological Drought Indices. Int. Journal Climatology, 1985, 5, pp 655-664.

- Tommaso Abrate , Pierre Hubert and Daniel Sighomnou A study on hydrological series of the Niger River, Hydrological Sciences Journal 2013, 58:2, 271-279. [CrossRef]

- Niger Basin Snapshot. Adaptation to Climate Change in the Upper and Middle Niger River Basin, 2010.

- Namara R.E., Barry B., Owusu E.S., and Ogilvie A. An overview of the development challenges and constraints of the Niger Basin and possible intervention strategies, Colombo, Sri Lanka international water management institute (IWMI Working Paper 144), 2011, p 34.

- Sheffield, J., Wood, E.J.F., Chaney, N., Guan, K., Sardi, S., Yuan, X., Olang, L., Amani, A., Ali, A., Demuth, S., Ogallo, L. A drought monitoring and forecasting system for sub-sahara African water resources and food security. Bull Am Met Soc 2014, 95(6):861–882.

- Liang, X., E. F. Wood, and D. P. Lettenmaier. Surface soil moisture parameterization of the VIC-2L evaluation and modification. Global Planet. Change,1996, 13, 195–206.

- 2013; 65. African Water Cycle Monitor Tutorial, 2013.

- Seiler R.A., Hayes M., Bressan L. Using the standardized precipitation index for flood risk monitoring. Int J Climatol 2002, 22:1365–1376. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1002/ joc. 799.

- Abah, E.O., Ayodele, A.P., Precious, E., Noguchi, R., Omale, P.A. Drought Assessment over Northern Africa Using Multi-source Satellite Product. In: Ahamed, T. (eds) Remote Sensing Application II. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives 2024, vol 77. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Quagraine, K. A., Nkrumah, F., Klein, C., Klutse, N. A.B., and Quagraine, K. T. West African Summer Monsoon Precipitation Variability as Represented by Reanalysis Datasets. MDPI Journal of Climate 2020, 8, 111; [CrossRef]

- Zhan W., Guan K., Sheffield J., Wood E. F. Depiction of drought over sub-Saharan Africa using reanalysis precipitation data sets. J Geophys Res Atmos, 2016,121:10555–10574. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1002/ 2016JD0248 58.

- N’Tcha M’Po Yèkambèssoun, Lawin Agnidé Emmanuel, Oyerinde Ganiyu Titilope, Yao Benjamin Kouassi, Afouda Abel Akambi. Comparison of Daily Precipitation Bias Correction Methods Based on Four Regional Climate Model Outputs in Ouémé Basin, Benin. Hydrology,2016, Vol. 4, No. 6, pp. 58-71. [CrossRef]

- Wetterhall F., Pappenberger F., He, Y., Freer J., Cloke H. Conditioning model output statistics of regional climate model precipitation on circulation patterns. Nonlinear Proc Geophys 2012, 19:623–633.

- Fang, G.H., Yang J., Chen Y.N., Zammit C. Comparing bias correction methods in downscaling meteorological variables for a hydrologic impact study in an arid area in China. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2015, 19:2547–2559.

- Shrestha, M., Acharya, S.C., Shrestha, P.K. Bias correction of climate models for hydrological modelling–are simple methods still useful? Meteorol Appl 2017, 24:531–539.

- Changnon, S. A. Detecting Drought Conditions in Illinois. Illinois State Water survey, Champaign, Circular, 1987, 169.

- Mishra, A. K., and V. P. Singh. A review of drought concepts, J. Hydrol., 2010, 391(1–2), 202–216. [CrossRef]

- Tallaksen, L.M. and Van Lanen, H.A.J. Hydrological Drought. Processes and Estimation Methods for Streamflow and Groundwater. Developments in Water Science, 2004, 48, Elsevier Science B.V., 579 pg.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ye, Z.; Lyu, J.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Drought Propagation in the Loess Plateau: A Geomorphological Perspective. Water 2025, 17, 2447. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Célia Gouveia, C., Camarero, J.J., Begueríae ,S., Trigo, R., López-Moreno,J. I., Azorín-Molina, C., Pasho, E, Lorenzo-Lacruz, J., Revueltoa, J., Morán-Tejeda, E , and Sanchez-Lorenzo, A. Response of vegetation to drought time-scales across global land biomes PNAS, 2013, vol. 110, no. 1, 52-57.

- IPCC Climate Change: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Watson, R.T. and the Core Writing Team (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, NY, USA,2001, 398 pp.

- Wilhite, D.A., Sivakumar, M.V.K, and Pulwarty, R. Managing drought risk in a changing climate: the role of national drought policy. Weather Clim Extremes, 2014, 3:4–13.

- Thornthwaite, C.W. and Mather, J.R. Instructions and tables for computing potential evapotranspiration and the water balance. Publ. Climatol.,1957, 10(3), 311pp.

- Vlahinić, M. (2004). Land reclamation and Agrohydrological Monograph of Popovo Polje. Department of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, 2004, Volume 6. Sarajevo. (In Bosnian).

- Čadro, S. Mirza Uzunović, M., Žurovec, J., and Žurovec, O. Validation and calibration of various reference evapotranspiration alternative methods under the climate conditions of Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Soil and Water Conservation Research, 2017, 5, 309–324.

- Hargreaves, G.H. and Samani, Z.A. (1985) Reference Crop Evapotranspiration from Temperature. Applied Engineering in Agriculture,1985, 1, 96-99. [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. Irrigation water requirements. Tech. Rel. 1970 No. 21, (rev. 1970) 88 pp.

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Standardized Precipitation Index User Guide. WMO-No. 1090.,2012.

- Nicholson S.E. Sub-saharan rainfall 1981–1984. J Clim Appl Meteorol 1985, 24:1388–1391.

- Yevjevich V. An objective approach to definitions and investigations of continental hydrologic droughts, Hydrology papers no. 23, Fort Collins: Colorado State University Natural Hazards, 1967, 1, 3.

- World meteorological organization (WMO). Experts agree on a universal drought index to cope with climate risks. Press release No. 872, 2009.

- Dracup, J.A., K.S. Lee, and E.G. Paulson, Jr. On the definitions of droughts. Water Resources Research, 1980.

- Ruqoyyah, S., Murni, S., & Fasha, L. H. Microsoft Excel VBA on mathematical resilience of primary school teacher education students. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2020, 1657(1), 012010. [CrossRef]

- Kulworatit, C. & Tuntiwongwanich, S. The use of digital intelligence and association analysis with data mining methods to determine the factors affecting digital safety among Thai adolescents. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change,2020, 14(2), 1120-1134.

- Guttman N. Accepting the standardized precipitation index: a calculation algorithm. J Am Water Resour As, 1999, 35(2):311–322.

- Wilhite, D. A., and Pulwarty, R. S. Drought and water crises: Integrating science, management, and policy (2nd ed.). CRC Press, 2017.

- Rao, G. S., Srinivas, V. V., & Subba Rao, M. Development of a composite drought index for agricultural impact assessment in India. Natural Hazards, 2013, 65(3), 1627–1647.

- Hao, Z., Zhang, J., & Yao, F. Integrated drought monitoring for agricultural drought in North China. Natural Hazards, 2014, 70(1), 799–815.

- Gebrehiwot, T., van der Veen, A., & Maathuis, B. Spatial and temporal assessment of drought in the Northern highlands of Ethiopia. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation, 2011.

- Hao, Z., and Singh, V. P. Drought characterization from a multivariate perspective: A review. Journal of Hydrology, 2015, 527, 668–678.

- Otkin, J. A., Anderson, M. C., Hain, C., & Svoboda, M. Examining the relationship between drought development and rapid changes in the Evaporative Stress Index. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 2018, 19(3), 787–802.

- Anderson, M. C., et al.. Monitoring rapid onset drought using thermal remote sensing and evapotranspiration data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2013, 138, 290–303.

- Diffenbaugh, N. S., Swain, D. L., & Touma, D. Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California. PNAS,2015, 112(13), 3931–3936.

- Sun, D. and Kafatos, M. Note on the NDVI-LST Relationship and the Use of Temperature-Related Drought Indices over North America. Geophysical Research Letters 2007, 34, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Pei, W., Fu, Q., Liu, D. and Li, T. A drought index for Rainfed agriculture: The Standardized Precipitation Crop Evapotranspiration Index (SPCEI). Hydrol. Processes 2019, 33(5): 803-815.

- Prihodko, L., and Goward, S. N. Estimation of air temperature from remotely sensed surface observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 60, 335–346.

- Boegh, E., Soegaard, H., Hanan, N., Kabat, P., & Lesch, L. A remote sensing study of the NDVI-Ts relationship and the transpiration from sparse vegetation in the Sahel based on high-resolution satellite data. Remote Sensing of Environment 1998, 69, 224–240.

- National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC). (2020). U.S. Drought Monitor. Retrieved from https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu.

- National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC). (2023). How the Drought Monitor is Made. https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu.

| Parameters | Record Period | Time scale | Spatial scale | Source |

| Precipitation | 1980–2016 | Daily | 0.25 x 0.25 | AFDM website |

| Temperature | 1980–2016 | Daily | 0.25 x 0.25 | AFDM website |

| Soil moisture | 1980–2016 | Daily | 0.25 x 0.25 | AFDM website |

| Streamflow | 1980–2016 | Daily | 0.25 x 0.25 | AFDM website |

| Category | Subjective Threshold | Objective Indices | Upper Niger ( Koulikoro) | Inland Delta ( Dire) | Middle Niger (Niamey) | Lower Niger ( Lokoja) |

| Mild Drought/ Abn Dry | 0 to -0.99 | SPI | (-0.49 to -0.78) | (-0.39 to -0.83) | (-0.59 to -0.74) | (-0.45 to -0.84) |

| CDI | (-0.43 to -0.81) | (-0.48 to -0.81) | (-0.08 to -0.82) | (-0.32 to -0.69) | ||

| Moderate Drought | (-1.0 to -1.49) | SPI | (-0.79 to -1.32) | (-0.84 to -1.34) | (-0.75 to -1.34) | (-0.85 to −1.25) |

| CDI | (-0.64 to -1.11) | (-0.72 to -1.08) | (-0.26 to -1.19) | (-0.56 to −0.99) | ||

| Severe Drought | (-1.50 to-1.99) | SPI | (-1.33 to −1.76) | (-1.35 to -1.50 | (-1.35 to −1.71) | (-1.26 to -1.49) |

| CDI | (-0.91 to -1.39 | (-0.99 to -1.45) | (-0.42 to −1.60) | (-0.94 to -1.72) | ||

| Extreme Drought | < -2.0 | SPI | (-177 to −1.81) | (-1.51 to -1.63) | (-1.72 to −1.86) | (-1.50 to −1.77) |

| CDI | (-1.09 to -1.58) | (-1.14 to -1.69) | (-0.58 to −1.76) | (-1.52 to −1.67) | ||

| Exceptional Drought | SPI | |||||

| CDI | (- 1.32 to -1.79) | (-1.28 to -1.85) | (-0.73 to −1.87) | (-1.12 to -1.96) |

| Sub- Basin | Index Models | R2 | NSE | PBIAS | MAE | d |

| Upper Niger | SEPI | 0.701 | 0.776 | -0.374 | 0.322 | 0.906 |

| SMI | 0.842 | 0.946 | 0.169 | 0.239 | 0.953 | |

| SFI | 0.922 | 0.977 | 0.071 | 0.149 | 0.978 | |

| Inland Delta | SEPI | 0.477 | -0.146 | -2.200 | 0.546 | 0.800 |

| SMI | 0.655 | 0.721 | 0.516 | 0.846 | 0.844 | |

| SFI | 0.683 | 0.928 | -0.070 | 0.165 | 0.898 | |

| Middle Niger | SEPI | 0.501 | -0.377 | -1.601 | 0.681 | 0.816 |

| SMI | 0.744 | 0.889 | 0.278 | 0.418 | 0.914 | |

| SFI | 0.79 | 0.935 | 0.234 | 0.332 | 0.932 | |

| Lower Niger | SEPI | 0.501 | 0.864 | -0.305 | 0.235 | 0.839 |

| SMI | 0.698 | 0.906 | 0.286 | 0.380 | 0.890 | |

| SFI | 0.736 | 0.899 | 0.302 | 0.412 | 0.910 |

| Country Drought Chronology Success ENSO Success Rate (%) Rate (%) |

| Cameroun 100 69 Chad 89 62 Nigeria 85 69 Niger 75 62 Benin 100 62 Burkina Faso 100 62 Cote d’Ivoire 100 62 Guinea 67 77 Mali 100 62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).