Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

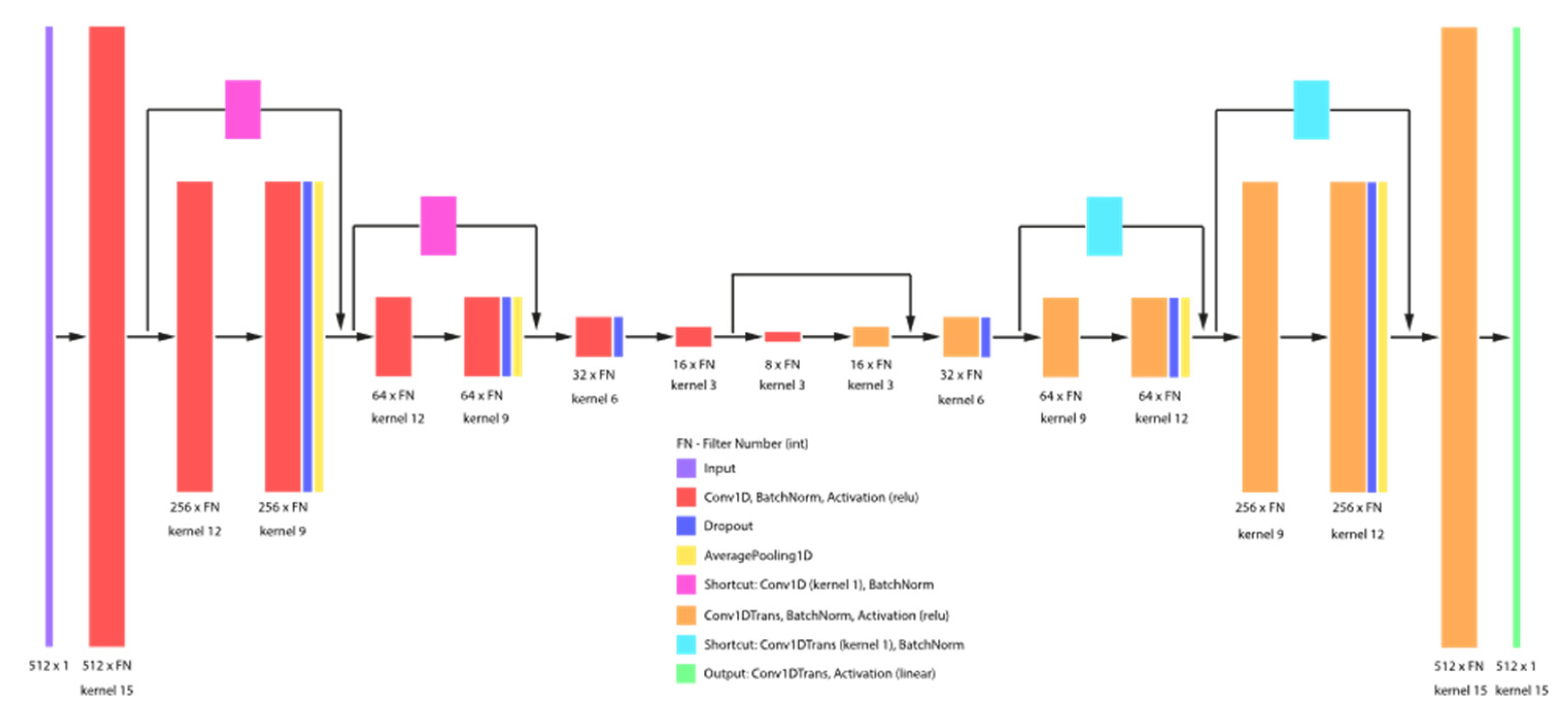

2.1. Convolutional Autoencoder Model

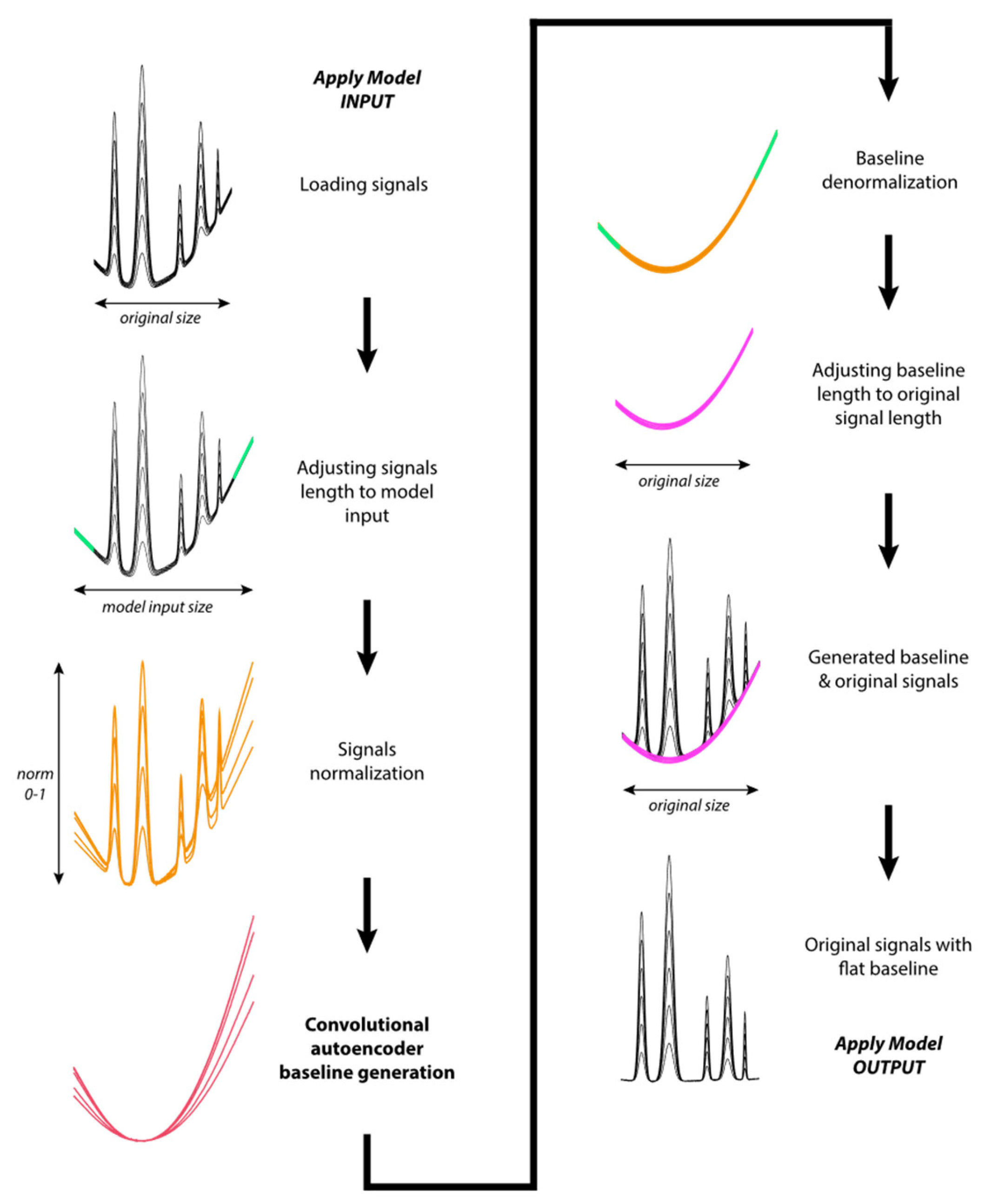

2.2. Apply Model Algorithm

3. Model Preparation

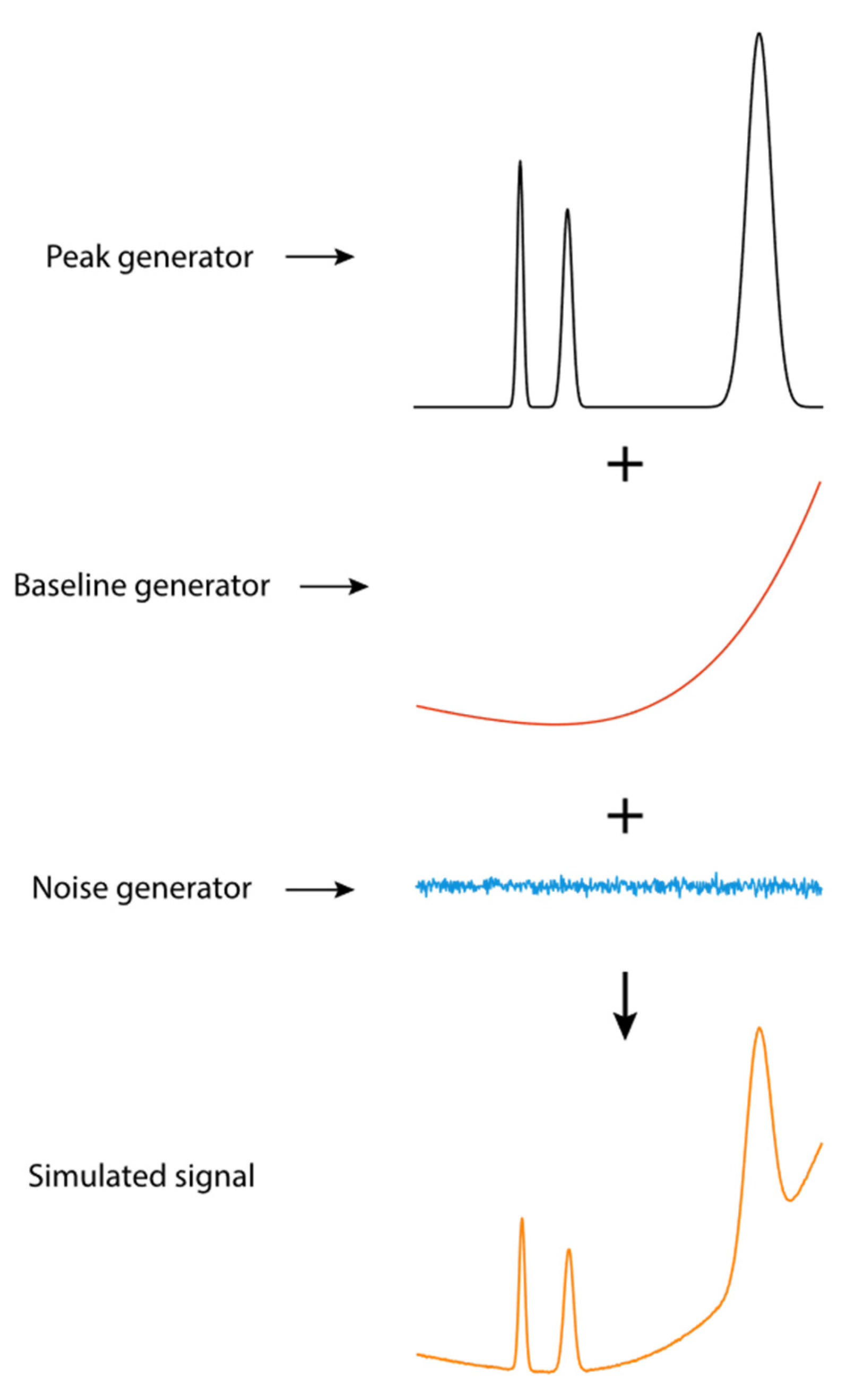

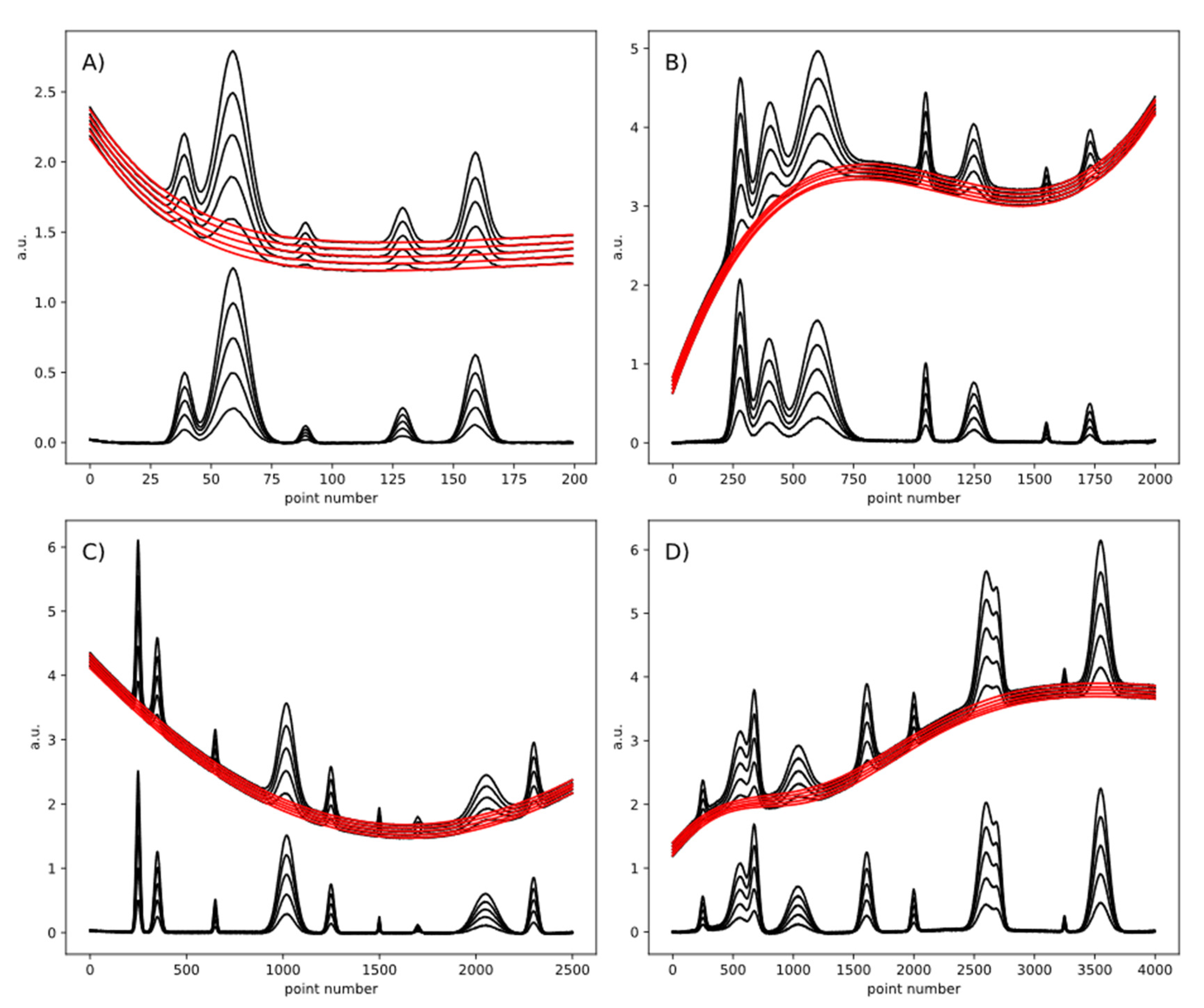

3.1. Generation of Simulated Signals for Model Training

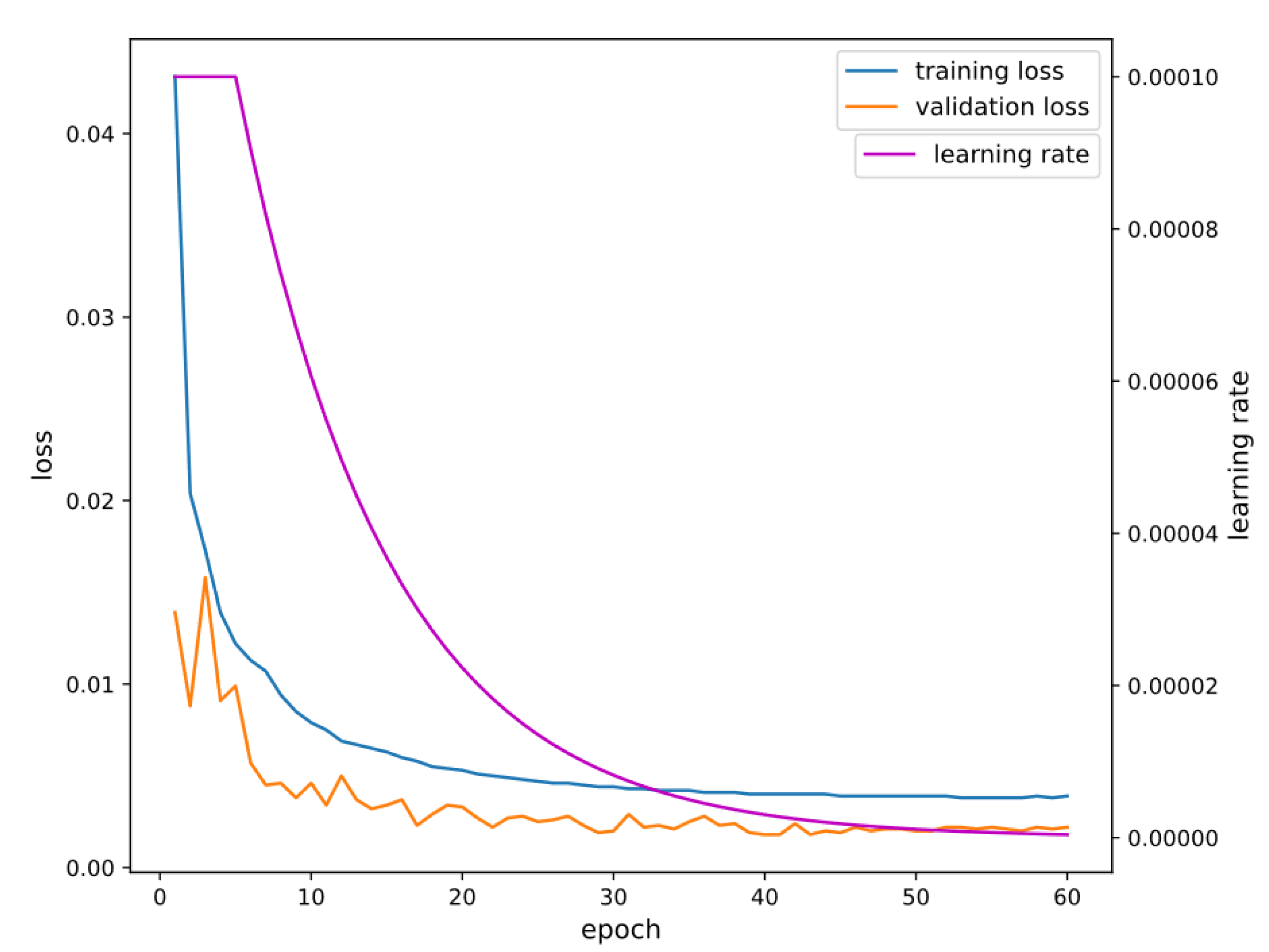

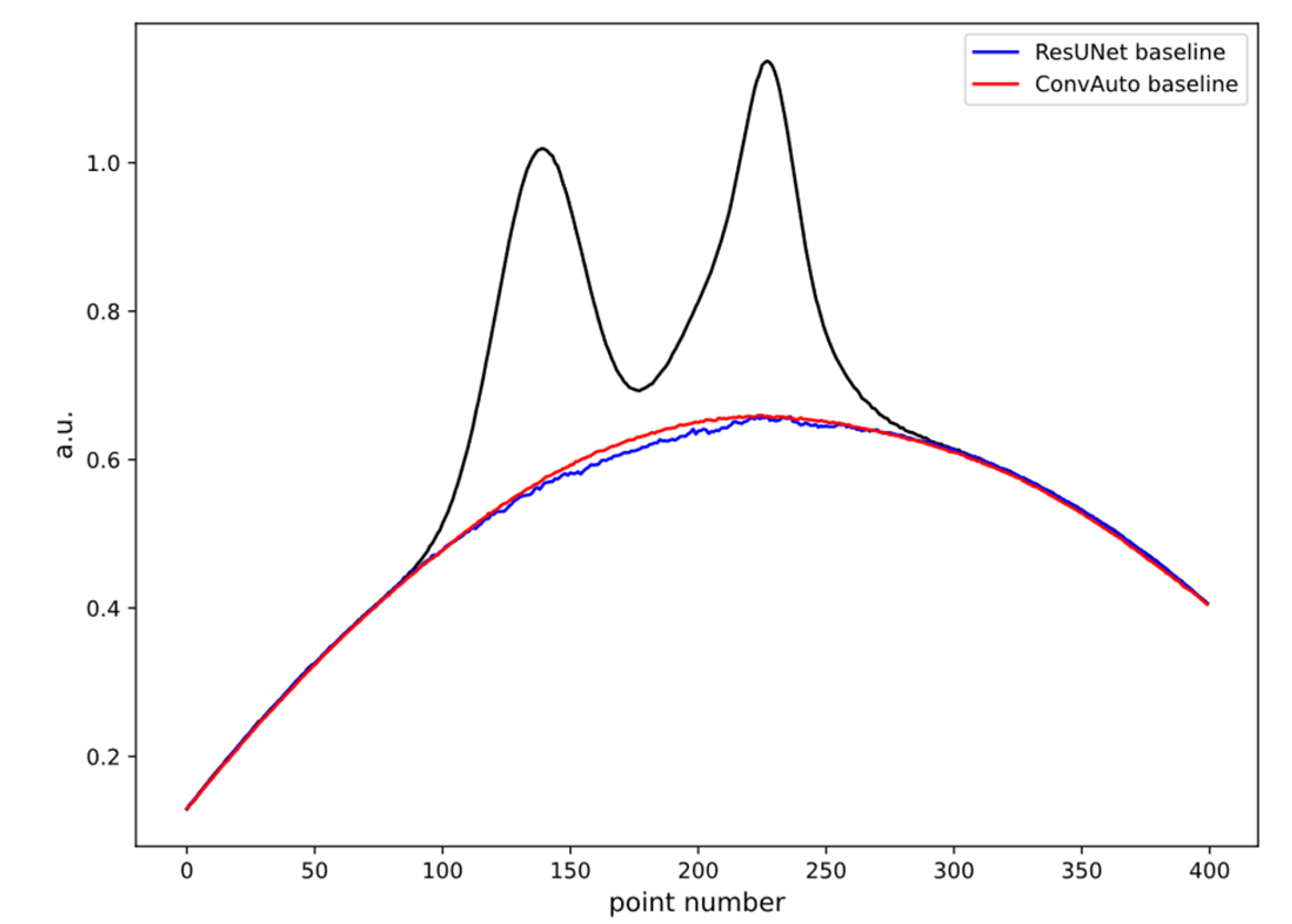

3.2. Model Training Details

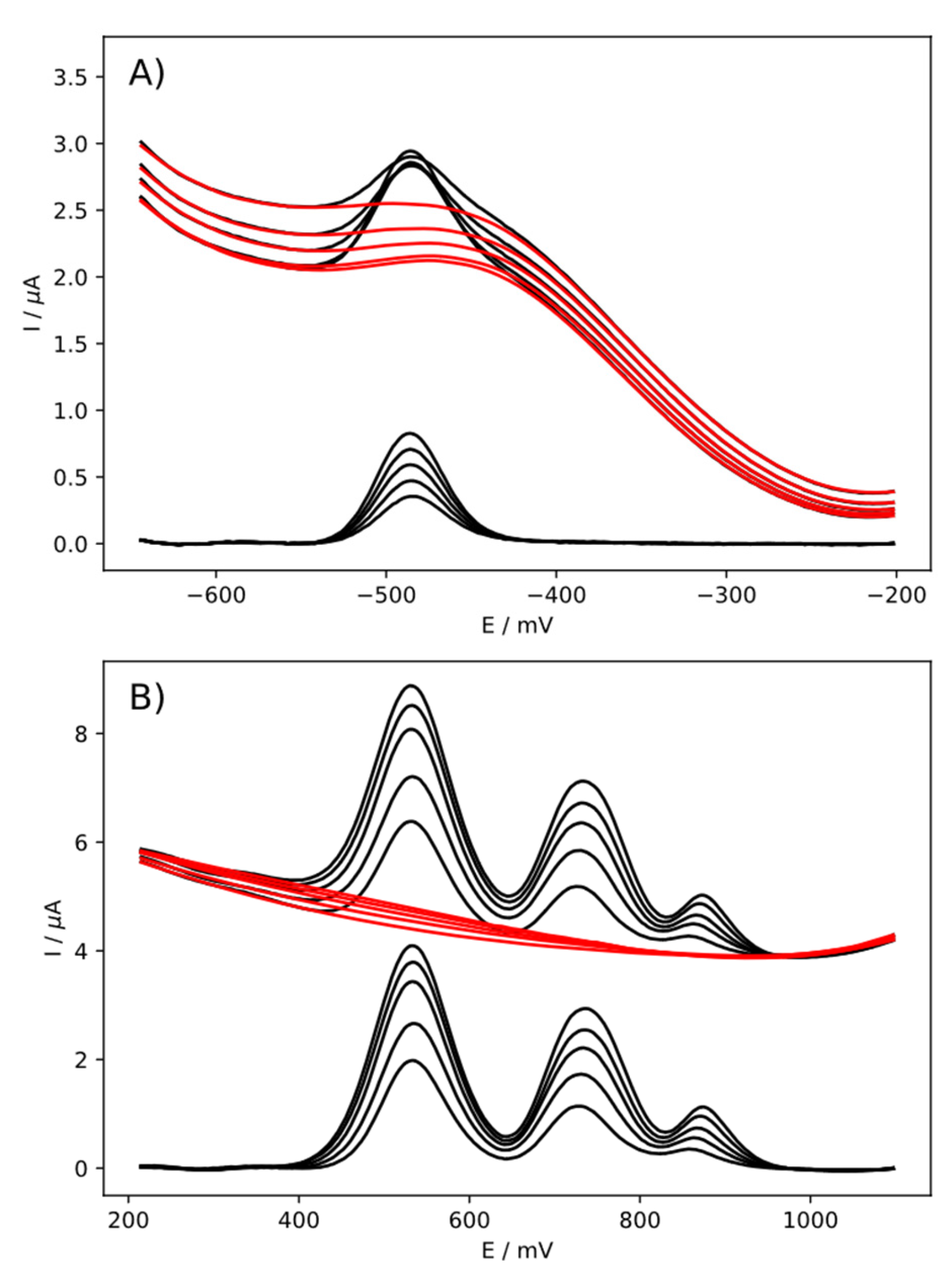

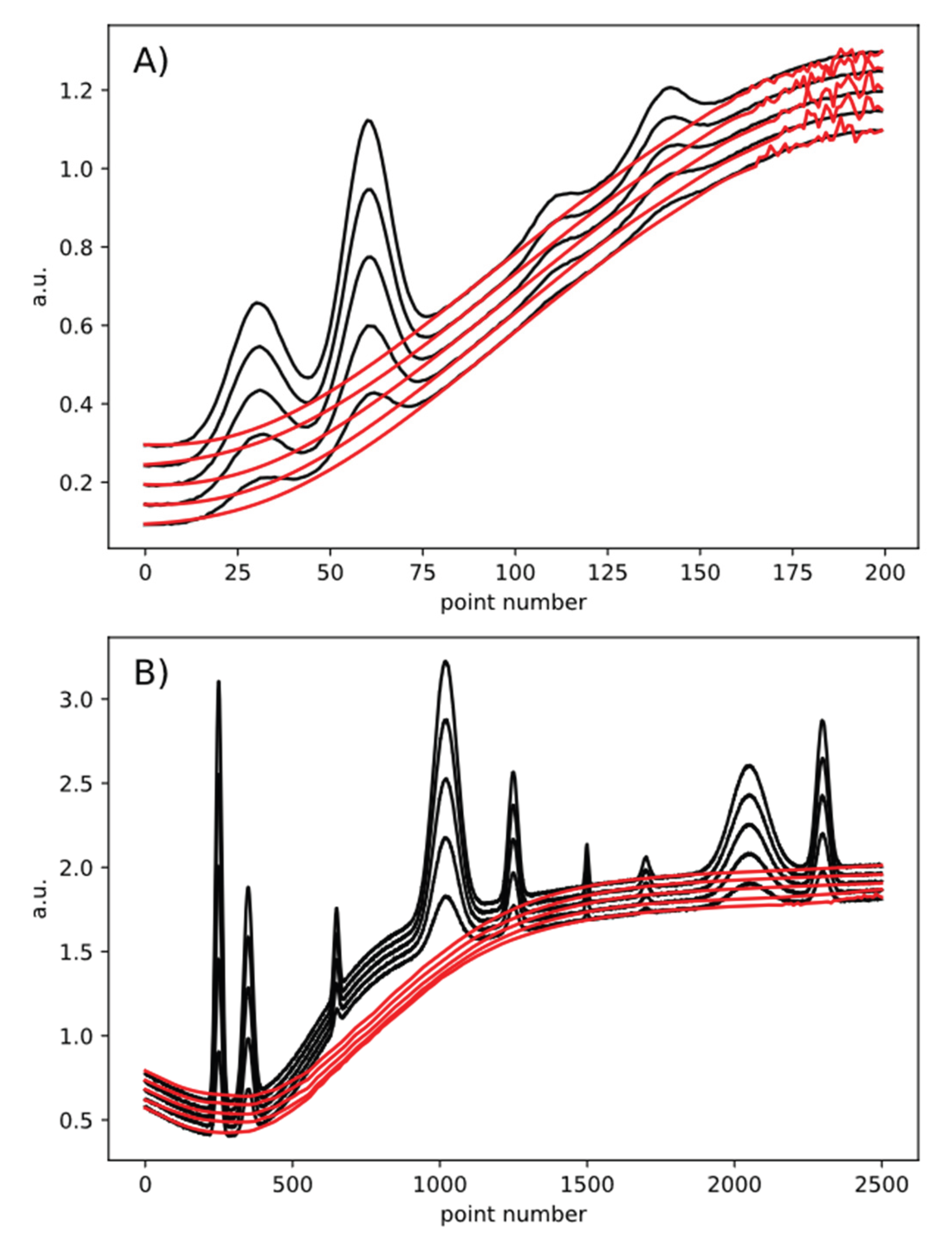

3.3. Experimental Signals

4. Results and Discussion

5. Summary

Funding

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallo, C.; Capozzi, V.; Lasalvia, M.; Perna, G. An algorithm for estimation of background signal of Raman spectra from biological cell samples using polynomial functions of different degrees. Vib Spectrosc 2016, 83, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.; Ruan, G.; Mo, J. Baseline correction by improved iterative polynomial fitting with automatic threshold. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2006, 82, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, Ł.; Ciepiela, F.; Jakubowska, M. Automatic baseline correction in voltammetry. Electrochim Acta 2014, 136, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Fang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Xie, W.; Zhang, H.; Wei, D.; Fu, W.; Pei, D. Investigation of a genetic algorithm based cubic spline smoothing for baseline correction of Raman spectra. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2016, 152, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- yin Dong, Z.; hang Yu, Z. ; Baseline correction using morphological and iterative local extremum (MILE). Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2023, 240, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, W. Automatic background correction method for laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochim Acta Part B At Spectrosc 2023, 208, 106763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Z.M.; He, P. Two-stage iteratively reweighted smoothing splines for baseline correction. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2022, 227, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, D.; Gui, W. Baseline correction for Raman spectra using penalized spline smoothing based on vector transformation. Analytical Methods 2018, 10, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, L.; Ciepiela, F.; Jakubowska, M.; Kubiak, W.W. ; Baseline correction in standard addition voltammetry by discrete wavelet transform and splines. Electroanalysis 2011, 23, 2658–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckstuhl, A.F.; Jacobson, M.P.; Field, R.W.; Dodd, J.A. Baseline subtraction using robust local regression estimation. J Quant Spectrosc Radiat Transf 2001, 68, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Gao Q.; Zhang Y. A robust baseline elimination method based on community information. Digital Signal Processing: A Review Journal 2015, 40, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, F.; Drescher, M. Background removal from rapid-scan EPR spectra of nitroxide-based spin labels by minimizing non-quadratic cost functions. J Magn Reson Open 2023, 16–17, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazet, V.; Carteret, C.; Brie, D.; Idier, J. Humbert B. Background removal from spectra by designing and minimising a non-quadratic cost function. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2005, 76, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dai, J.; Pan, T.; Chang, C.; So, H.C. Sparse Bayesian learning approach for baseline correction. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2020, 204, 104088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, P.H.C. A perfect smoother. Anal Chem 2003, 75, 3631–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, P.H.C.; Boelens, H.F.M. Baseline Correction with Asymmetric Least Squares Smoothing, Leiden University Medical Centre Report 2005. Available online: http://www.science.uva.nl/~hboelens/publications/draftpub/Eilers_2005.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Peng, J.; Peng, S.; Jiang, A.; Wei, J.; Li, C.; Tan, J. Asymmetric least squares for multiple spectra baseline correction. Anal Chim Acta 2010, 683, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.-J.; Park, A.; Ahn, Y.-J.; Choo, J. Baseline correction using asymmetrically reweighted penalized least squares smoothing. Analyst 2015, 140, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Yang, R. An improved PD-AsLS method for baseline estimation in EDXRF analysis. Analytical Methods 2021, 13, 2037–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.M.; Chen, S.; Liang, Y.Z. Baseline correction using adaptive iteratively reweighted penalized least squares. Analyst 2010, 135, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Tang, X.; Tong, A.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Lv, Y.; Tang, C.; Wang, J. Baseline correction for infrared spectra using adaptive smoothness parameter penalized least squares method. Spectroscopy Letters 2020, 53, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Tian, Y.; Zha, G.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Sun, W.; Li, C.M.; Wei, L.; Chen, P.; Cao, C. Microstrip isoelectric focusing with deep learning for simultaneous screening of diabetes, anemia, and thalassemia. Anal Chim Acta 2024, 1312, 342696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuyun, W.; Lin, F.; Pan, C.; Zhang, Q.; Tao, H.; Fan, M.; Xu, L.; Kong, K.V.; Chen, Y.; Lin, D.; Feng, S. Laser tweezer Raman spectroscopy combined with deep neural networks for identification of liver cancer cells. Talanta 2023, 264, 124753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, S.; Ciepiela, F.; Baś, B.; Jakubowska, M. Deep learning assisted distinguishing of honey seasonal changes using quadruple voltammetric electrodes. Talanta 2022, 241, 123213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Li, C.; Yan, C.; Min, H.; An, Y.; Liu, S. Interpretable deep learning-assisted laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy for brand classification of iron ores. Anal Chim Acta 2021, 1166, 338574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Date, Y.; Kikuchi, J. Application of a Deep Neural Network to Metabolomics Studies and Its Performance in Determining Important Variables. Anal Chem 2018, 90, 1805–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Xia, C.; Bai, Q.; Jin, L.; Shen, Y. An in silico scheme for optimizing the enzymatic acquisition of natural biologically active peptides based on machine learning and virtual digestion, Anal Chim Acta 2024, 1298, 342419. [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Zhao, W.; Yu, Q.; Qian, X.; Zhou, J.; Huo, X.; Tang, F. SR-Unet: A Super-Resolution Algorithm for Ion Trap Mass Spectrometers Based on the Deep Neural Network. Anal Chem 2023, 95, 17407–17415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, T.; Xu, J.; Luo, X.; Ying, Y. DeepSpectra: An end-to-end deep learning approach for quantitative spectral analysis. Anal Chim Acta 2019, 1058, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Ryu, J.; Joo, H.; Jung, H.T.; Kim, J. Finding Hidden Signals in Chemical Sensors Using Deep Learning. Anal Chem 2020, 92, 6529–6537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Luo, J.; Zeng, Q.; Dong, X.; Chen, J.; Zhan, C.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Y. Improvement in signal-to-noise ratio of liquid-state NMR spectroscopy via a deep neural network DN-Unet. Anal Chem 2021, 93, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantz, E.D. , Tiwari S., Watrous J.D., Cheng S., Jain M. Deep Neural Networks for Classification of LC-MS Spectral Peaks. Anal Chem 2019, 91, 12407–12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Adversarial nets for baseline correction in spectra processing. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2021, 213, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Q.; Guo, X.; Liu, M.; Kong, L.; Hui, M.; Dong, L.; Zhao, Y. Deep learning baseline correction method via multi-scale analysis and regression. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2023, 235, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemzadeh, M.; Martinez-Calderon, M.; Xu, W.; Chamley, L.W.; Hisey, C.L.; Broderick, N.G.R. Cascaded Deep Convolutional Neural Networks as Improved Methods of Preprocessing Raman Spectroscopy Data. Anal Chem 2022, 94, 12907–12918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Son, Y.J.; Park, A.; Baek, S.J. Baseline correction using a deep-learning model combining ResNet and UNet, Analyst 2022, 4285–4292. [CrossRef]

- Baś, B.; Jakubowska, M.; Reczyński, W.; Ciepiela, F.; Kubiak, W.W. Rapidly renewable silver and gold annular band electrodes. Electrochim Acta 2012, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, Ł.; Sordoń, W.; Jakubowska, M. Voltammetric Determination of Ternary Phenolic Antioxidants Mixtures with Peaks Separation by ICA. J Electrochem Soc 2017, 164, H42–H48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Loss (MAE) | Metrics (RMSE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Train | 0.0039 | 0.0093 |

| Validate | 0.0022 | 0.0047 |

| Test | 0.0022 | 0.0051 |

| ConvAuto | ResUNet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | |

| SimSet 1 | 0.0034 | 0.0045 | 0.0023 | 0.0030 |

| SimSet 2 | 0.0192 | 0.0230 | 0.0114 | 0.0198 |

| SimSet 3 | 0.0102 | 0.0120 | 0.0119 | 0.0224 |

| SimSet 4 | 0.0198 | 0.0263 | 1.6839 | 1.7957 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).