Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Problem

1.2. The Park

“Permanently protect a system of provincial parks and conservation reserves that includes ecosystems that are representative of all of Ontario’s natural regions, protects provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage, maintains biodiversity and provides opportunities for compatible, ecologically sustainable recreation…” 2006, c. 12, s. 1. maintenance of ecological integrity shall be the first priority and the restoration of ecological integrity shall be considered. 2006, c. 12, s. 3.

“a condition in which biotic and abiotic components of ecosystems and the composition and abundance of native species and biological communities [biodiversity] are characteristic of their natural regions and rates of change and ecosystem processes are unimpeded” (Province of Ontario, 2006, c. 12, s. 5 (2)). It “includes, but is not limited to, (a) healthy and viable populations of native species, including species at risk, and maintenance of the habitat on which the species depend; and (b) levels of air and water quality consistent with protection of biodiversity and recreational enjoyment” (Province of Ontario, 2006, c. 12,s. 5 (3)).

1.3. Purpose and Objectives

2. Methods

3. Results

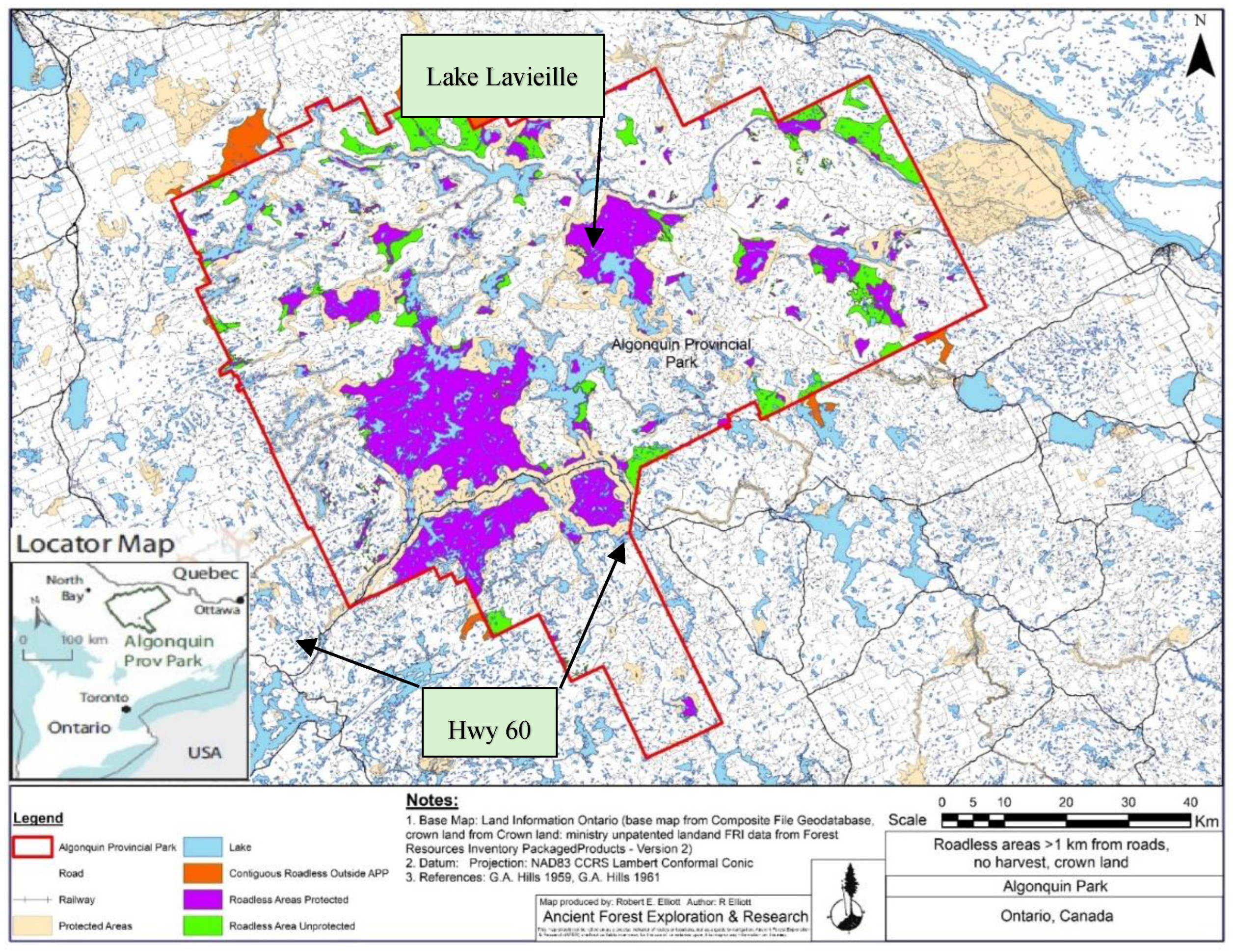

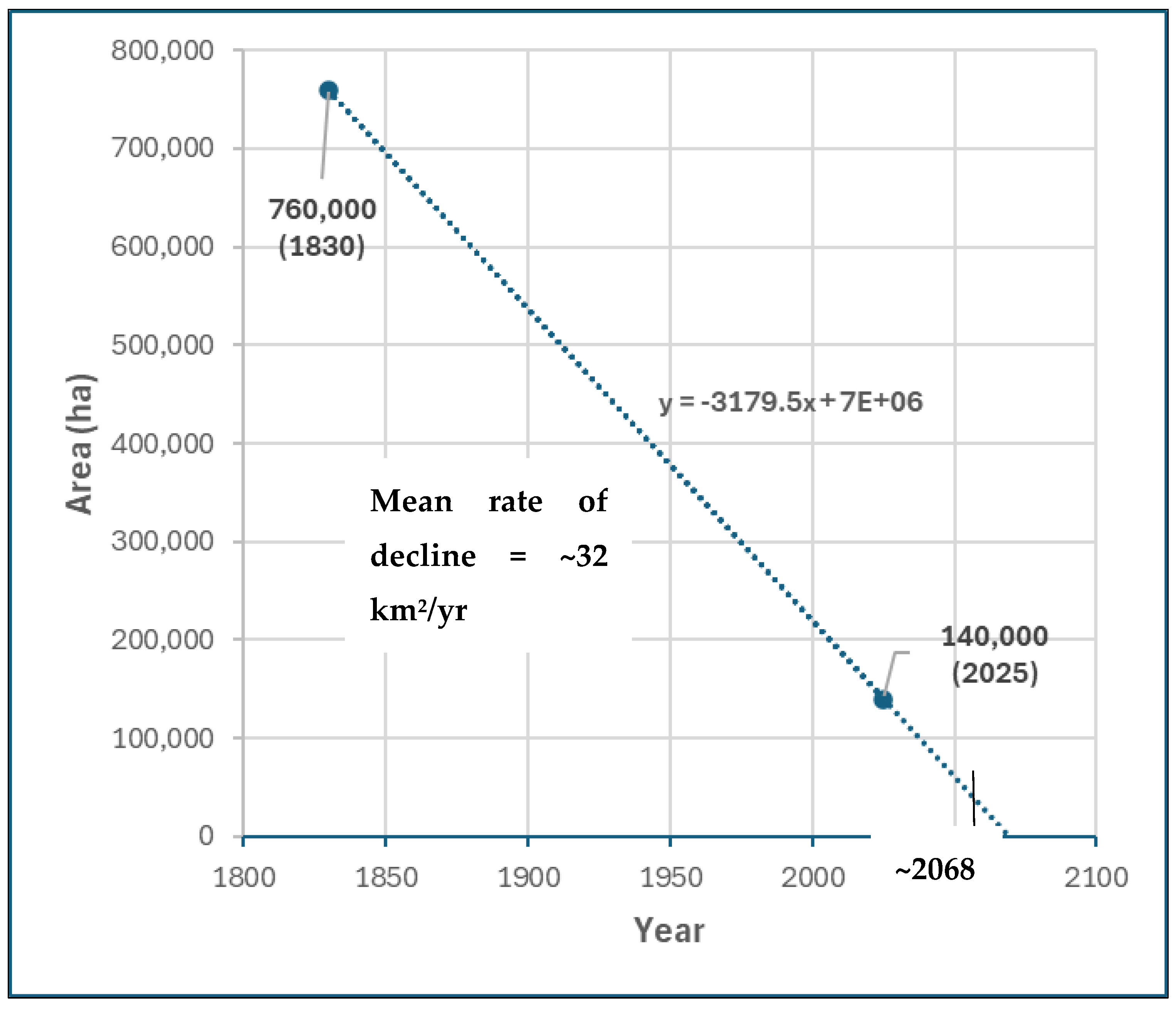

3.1. Roadless Wildlife Habitat

3.2. Literature Review

Decline in Ecological Integrity

Species Declines

4. Discussion

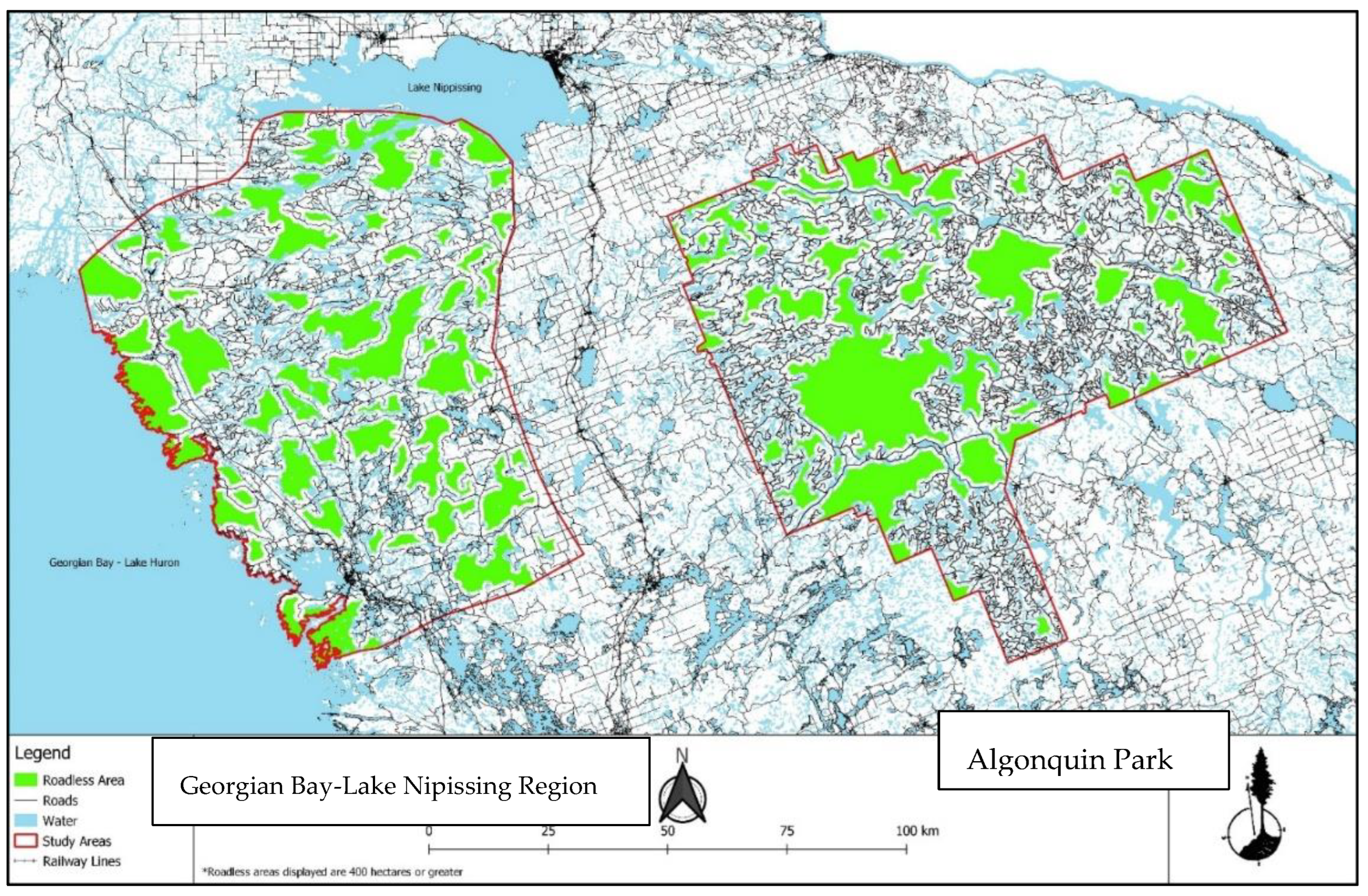

4.1. Regional Comparison of Roadless Wildlife Habitat

4.2. Multiple-use Forest Management

4.3. Sustainability of Ecological Integrity and Biodiversity

4.4. Restoration

4.5. Applied Research and Outreach

4.6. Limitations and Roadless Wildlife Habitat as an Integrative Indicator

- Roads cause cascading impacts on ecosystems through landscape fragmentation, wildlife habitat degradation and loss, chemical pollution, and invasive species spread among other negative ecological impacts (e.g., loss of water and air quality, higher soil erosion losses, degraded recreational experiences, etc.) that decrease with distance from road and human infrastructure edges (Chen et al., 2024; Boan and Plotkin, 2025). Negative effects extend up to 14 km from a road in some cases (e.g., caribou; Plante, 2018).

- Due to substantial distance away from roads, infrastructure, and associated impacts, RWH functions to maintain ecosystem integrity and biodiversity. It also enhances landscape connectivity and provides resistance and resilience to extreme weather and disturbance events (Psaralexi et al., 2017). However, more studies are required to better understand the ecology of road buffer zones and their impacts on RWH, which varies by landscape type as well as by road type and use.

- RWH maps (using analytical geographic information systems - GIS) are simple, straightforward, measurable, cost effective, and provide 100% study area coverage, which facilitates monitoring and evaluation of land-use management effectiveness and progress towards meeting landscape protection goals (Kati et al., 2023).

- Roads, buffer zones, and RWH provide a conceptual and spatial structure for the design of ecological monitoring programs where “distance from road or human infrastructure” (road buffer) is one of the wildlife habitat variables to be assessed and evaluated as a potential influence on wildlife habitat quality. Ideally, monitoring data can be used to adjust buffer zone location, shape, and width to sustain ecological function within the buffer zone and within RWH areas.

- RWH assessment and management is the most cost effective approach to protecting biodiversity and maintaining carbon stocks (Ibish et al., 2016) and was chosen as the means of achieving EU 2020 biodiversity strategy targets (Psaralexi et al., 2017).

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Algonquin Forestry Authority (AFA). Sustainable Forest Management Policy. 2025. Available online: https://algonquinforestry.on.ca/policy-planning-sustainable-forest-management-policy/.

- Algonquin Provincial Park (APP). Algonquin Provincial Park Management Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Toronto and Whitney, Ontario. 1998. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/algonquin-provincial-park-management-plan#section-8.

- Algonquin Wildlife Research Station (AWRS). World-class Science Conducted in Algonquin Park. 2025. Available online: https://www.algonquinwrs.ca/.

- Anderson, H. W.; Gordon, A. G. The tolerant conifers: Eastern hemlock and red spruce, their ecology and management. Forest Research Report; No. 113, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario: Ontario Forest Research Institute, 1990; Available online: https://bibliotheque.cecile-rouleau.gouv.qc.ca/notice?id=p%3A%3Ausmarcdef_0000341885&locale=fr.

- ArborVitae Environmental Services (AES). Management of Algonquin Park West Side Forests. Georgetown, Ontario: Report Prepared for Algonquin EcoWatch. 2010. Available online: https://8e1108ad-02ad-4c2e-b3b4-294c65552fe4.filesusr.com/ugd/1eacbf_9222c98b87c14fb7a26ae2117ac2fc90.pdf?index=true.

- Auditor General of Ontario (AGO). Summaries of Value-for-Money Audits. Office of the Auditor General of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario. 2022. Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arbyyear/ar2022.html.

- Auditor General of Ontario (AGO). Value--for--Money Audit: Conserving the Natural Environment with Protected Areas. Office of the Auditor General of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario. 2020. Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en20/ENV_conservingthenaturalenvironment_en20.pdf.

- Baskent, E. Z. A review of the development of the multiple use forest management planning concept. The International Forestry Review 2018, 20(3), 296–313. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26855482. [CrossRef]

- Baskent, E. Z.; Borges, J. G.; Kašpar, J. An Updated Review of Spatial Forest Planning: Approaches, Techniques, Challenges, and Future Directions. Current Forestry Reports 2024, 10, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beazley, K. F; Olive, A. Transforming conservation in Canada: shifting policies and paradigms. FACETS 2021, 6, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, J. F.; Mills, K. J.; Patterson, B. Resource selection by wolves at dens and rendezvous sites in Algonquin Park, Canada. Biological Conservation 2015, 182, 223–232. Available online: https://discovery.researcher.life/article/resource-selection-by-wolves-at-dens-and-rendezvous-sites-in-algonquin-park-canada/6ec39695926238e8b0dcc70b80a55c7a. [CrossRef]

- Betts, M. G.; Yang, Z.; Hadley, A. S.; Smith, A. C.; Rousseau, J. S.; Northrup, J. M.; Nocera, J.; Gorelick, J.; Gerber, N. B. D. Forest degradation drives widespread avian habitat and population declines. Nature Ecology and Evolution 2022, 6, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boan, J.; Plotkin, R. Counting on Canada’s Commitments: To Halt and Reverse Forest Degradation by 2030, Canada Must First Admit it has a Problem; Natural Resources Defence Council and David Suzuki Foundation; New York, NY and Vancouver, BC, 2025; Available online: https://www.davidsuzuki.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Forest-Degradation-in-Canada-R-25-04-A_06-1.pdf.

- Bowman, M. Economic Benefits of Nature Tourism: Algonquin Park as a Case Study. Waterloo, Ontario, M.A. Thesis, Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, University of Waterloo, 2001. Available online: https://uwaterloo.ca/recreation-and-leisure-studies/current-graduate-students/thesis-information/master-arts-thesis-list#MA2006.

- Brend, Y.; Duncombe, L. Fatal landslide blamed on old logging road raises fears about hidden risks near Canada’s highways. CBC News. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/landslide-risk-service-roads-1.6628050.

- Chapin, F. S., III. Transformative Earth stewardship: Principles for shaping a sustainable future for nature and society. Earth Stewardship 2024, 1, e12023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Di Marco, M.; Li, B. V.; Li, Y. Roadless areas as an effective strategy for protected area expansion: Evidence from China. One Earth 2024, 7, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, M. Algonquin Park commercial logging plan up for renewal in 2021: Impact of forestry operations on park’s ecological integrity should be reviewed, says auditor general. CBC News. 2020. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/algonquin-park-logging-2021-1.5849770.

- Cruickshank, A. Ontario Parks to build new camping accommodations in Algonquin Provincial Park. Cottage Life. 2024. Available online: https://cottagelife.com/general/ontario-parks-to-build-new-camping-accommodations-in-algonquin-provincial-park/.

- Cumming, G.; Janke, D. R. Forest Management Plan for the Algonquin Park Forest Management Unit; Huntsville, Ontario; Algonquin Forestry Authority, 2010; Available online: https://www.algonquinpark.on.ca/pdf/forestry_fmp_phase1_2010-2020.pdf.

- Currie, J.; Snider, J.; Giles, E. Living Planet Report Canada: Wildlife At Risk; Toronto, Ontario; World Wildlife Fund Canada, 2020; Available online: https://wwf.ca/living-planet-report-canada-2020/.

- Curtis, P. G.; Slay, C. M.; Harris, N. L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M. C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 2018, 361(6407), 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwynar, L. C. Recent history of fire and vegetation from laminated sediment of Greenleaf Lake, Algonquin Park, Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 1978, 56, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwynar, L. C. The recent fire history of Barron Township, Algonquin Park. Canadian Journal of Botany 1977, 55, 1524–1538. Available online: https://www.frames.gov/catalog/34022. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R. J.; Gray, P. A.; Boyd, S.; Cordiner, G. S. McCool, S. F., Cole, D. N., Borrie, W. T., Loughlin, J. O’, Eds.; State-of-the-Wilderness Reporting in Ontario: Models, Tools and Techniques. In Wilderness Science in a Time of Change Conference; Ogden, Utah; USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 2000; Vol. 2, Available online: https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/21934.

- DellaSala, D. A.; Mackey, B.; Kormos, C. F.; Young, V.; Boan, J. J.; Skene, J. L.; Lindenmayer, D. B.; Kun, Z.; Selva, N.; Malcolm, J. R.; Laurance, W. F. Measuring forest degradation via ecological-integrity indicators at multiple spatial scales. Biological Conservation 2025, 302(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dertien, J. S.; Larson, C. L.; Reed, S. E. Recreation effects on wildlife: a review of potential quantitative thresholds. Nature Conservation 2021, 44, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, P. R.; et al. Priorities for embedding ecological integrity in climate adaptation policy and practice. One Earth 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Ecological Integrity of National Parks; Gatineau, Quebec, 2024a. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/ecological-integrity-national-parks.html.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). Canada and Ontario commit to significant collaboration on shared nature conservation goals, Press Release. 2024b. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2024/03/canada-and-ontario-commit-to-significant-collaboration-on-shared-nature-conservation-goals.html.

- Environmental Commissioner of Ontario (ECO). Managing New Challenges: Annual Report 2013/2014; Toronto, Ontario; Office of the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, 2014; Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/reporttopics/envreports/env14/2013-14-AR.pdf.

- Fan, X; Zang, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhao, L.; Xu, W.; Ouyang, Z. Ecological integrity assessment system for Wuyishan national park. Ecological Indicators 2025, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, C. Parks Canada braces for $450 million in cuts and lapsed funding. Indigenous Watchdog. 2025. Available online: https://www.indigenouswatchdog.org/update/parks-canada-braces-for-450-million-in-cuts-and-lapsed-funding/.

- Fletcher, et al. Earth at risk: An urgent call to end the Age of Destruction and forge a just and sustainable future. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forest Resource Inventory (FRI) Ontario GeoHub. 2007. Available online: https://geohub.lio.gov.on.ca/.

- Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve (GBBR). Technical Report for Eastern and Northern Georgian Bay. Parry Sound, Ontario. 2018. Available online: www.stateofthebay.ca.

- Geleynse, D. M.; Nol, E.; Burke, D. M.; Elliott, K. A. Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) demographic response to hardwood forests managed under the selection system. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2016, 46, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, B. Our Georgian Bay Vegetation Communities. Landscript, Winter Issue; Toronto, Ontario; Georgian Bay Land Trust, 2019; Available online: https://www.gblt.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Winter-2019.pdf.

- Henry, M.; Quinby, P. Ontario’s Old-growth Forests; Toronto, Ontario; Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2021; Available online: https://www.amazon.ca/Ontarios-Old-Growth-Forests-2nd/dp/155455439X.

- Higgins, J.; Shalev, G. Impacts of Mechanization. Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage, Memorial University, St. Johns, Newfoundland. 2007a. Available online: https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/economy/mechanization-impacts.php.

- Higgins, J.; Shalev, G. Mechanization of the Logging Industry Since Confederation. Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage, Memorial University, St. Johns, Newfoundland. 2007b. Available online: https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/economy/mechanization.php.

- Hoffmann, M.T.; Ostapowicz, K.; Bartoń, K.; Ibisch, P.L.; Selva, N. Mapping roadless areas in regions with contrasting human footprint. Scientific Reports, Nature Portfolio 2024, 14, 4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibisch, P. L.; Hoffmann, M. T.; Kreft, S.; Pe’er, G.; Kati, V.; Biber-Freudenberger, L.; DellaSala, D. A.; Vale, M. M.; Hobson, P. R.; Selva, N. A global map of roadless areas and their conservation status. Science 2016, 354, 1423–1427. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27980208/. [CrossRef]

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature; IUCN. Protected Planet: Algonquin Park, Ontario Area Protected. 2022. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/555637720.

- Jetz, W.; McGowan, J.; Rinnan, D. S.; Possingham, H. P.; Visconti, P.; O’Donnell, B.; Londoño-Murcia, M. C. Include biodiversity representation indicators in area-based conservation targets. Nature Ecology and Evolution 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobes, A. P.; Nol, E.; Voigt, D. R. Effects of selection cutting on bird communities in contiguous eastern hardwood forests. Journal of Wildlife Management 2004, 68, 51–60. Available online: https://conservationevidence.com/individual-study/2397. [CrossRef]

- Kati, V.; Petridou, M.; Tzortzakaki, O.; Papantoniou, E.; Galani, A.; Psaralexi, M.; Gotsis, D.; Papaioannou, H.; Kassara, C. How much wilderness is left? A roadless approach under the Global and the European Biodiversity Strategy focusing on Greece. Biological Conservation 2023, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killan, G.; Warecki, G. J.R. Dymond and Frank A. MacDougall: Science and Government Policy in Algonquin Provincial Park, 1931-1954. Scientia Canadensis 1998, 22-23, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbitter, P.; Euler, D.; Naylor, B. A comparison of historical and current forest cover in selected areas of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest of central Ontario. Forestry Chronicle 2002, 78, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, J. R.; Boan, J. J.; Ray, J. C. Emulation or Degradation? Evaluating Forest Management Outcomes in Boreal Northeastern Ontario. Environmental Management 2025, 75, 1901–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C. A.; Proulx, R. Level-2 ecological integrity: Assessing ecosystems in a changing world. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 2020, 18, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.; Allen, C.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.; et al. Pervasive shifts in forest dynamics in a changing world; Science, 2020; Vol. 368, Issue 6494, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaz9463. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, E.; Syed, F. Ontario is about to slash environmental protections. It already wasn’t funding them, auditor general says. Narwhal. 2022. Available online: https://thenarwhal.ca/ontario-auditor-general-environment-2022/#:~:text=The%20commission%20has%20cut%20environmental,and%20hasn’t%20been%20replaced.

- McLoughlin, P.D.; Vander Wala, E.; Loweb, S. J.; Patterson, B. R.; Murray, D. L. Seasonal shifts in habitat selection of a large herbivore and the influence of human activity. Basic and Applied Ecology 2011, 12, 654–663. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/128654057/Seasonal_shifts_in_habitat_selection_of_a_large_herbivore_and_the_influence_of_human_activity. [CrossRef]

- Mead, J.; Freeman, D.; Gray, T.; Cundiff, B. Restoring Nature’s Place: How We Can End Logging in Algonquin Park, Protect Jobs and Restore the Park’s Ecosystems; Toronto, Ontario; Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, Wildlands League, 2000; Available online: https://wildlandsleague.org/media/restoring-natures-place.pdf.

- Nardone, E. The Bees of Algonquin Park: A Study of their Distribution, their Community Guild Structure, and the Use of Various Sampling Techniques in Logged and Unlogged Hardwood Stands. M.Sc. Thesis, Guelph, Ontario, University of Guelph, 2013. Available online: https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/bitstream/handle/10214/5245/Nardone_Erika_201301_MSc.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Niederman, T. E.; Aronson, J. N.; Gainsbury, A. M.; Nunes, L. A.; Dreiss, L. M. US Imperiled species and the five drivers of biodiversity loss. BioScience 2025, 75, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nol, E.; Douglas, H.; Crins, W. J. Responses of syrphids, elaterids and bees to single-tree selection harvesting in Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 2006, 120, 15–21. Available online: https://www.canadianfieldnaturalist.ca/index.php/cfn/article/download/239/239/953. [CrossRef]

- Ontario Biodiversity Council. State of Ontario’s Biodiversity: 2025 Summary. 2025. Available online: https://sobr.ca/wp-content/uploads/State-of-Ontarios-Biodiversity-2025-Summary_May-14-online-version-1.pdf.

- Ontario Ministry of Environment; Conservation; Parks (OMECP). Science and Research: Ontario Parks Research Cards. 2025. Available online: https://cangeoeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/11-Ontario-Parks-Research-cards.pdf.

- Ontario Ministry of Environment; Conservation; Parks (OMECP). News Release: Ontario Investing in Infrastructure Improvements at Algonquin Provincial Park. Ontario Newsroom May 5. 2023. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1003023/ontario-investing-in-infrastructure-improvements-at-algonquin-provincial-park.

- Ontario Parks Board. Lightening the Ecological Footprint of Logging in Algonquin Provincial Park; Toronto, Ontario; Ontario Parks Board, Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks, 2006; Available online: https://www.algonquinpark.on.ca/pdf/lighteningthefootprint_recommendations.pdf.

- Oved, M. C. They say Muskoka won’t burn. But climate has changed the calculus. Toronto Star. 2025. Available online: https://www.thestar.com/news/ontario/they-say-muskoka-won-t-burn-but-climate-has-changed-the-calculus/article_5342eb56-1143-4981-b534-503c598e3afe.html.

- Parrish, J. D.; Braun, D. P.; Unnasch, R. S. Are We Conserving What We Say We Are? Measuring Ecological Integrity within Protected Areas. BioScience 2003, 53, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.; Romaniuk, S.; Ferguson, M. Pre-settlement forest composition of Algonquin Park; Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southern Science and Information Section; North Bay, Ontario, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, F.; Romaniuk, S.; Ferguson, M. Changes to pre-industrial forest tree composition in central and northeastern Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2008, 38, 1842–1854. Available online: https://2024.sci-hub.st/3304/4d1ab97a661e6d56dedc097ed2b6fba4/pinto2008.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Plante, S.; Dussault, C.; Richard, J. H.; Côté, S. D. Human disturbance effects and cumulative habitat loss in endangered migratory caribou. Biological Conservation 2018, 224, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M. C.; Laestadius, L.; Turubanova, S.; Yaroshenko, A.; Thies, C.; Smith, W.; Zhuravleva, I.; Komarova, A.; Jantz, S. The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013. Science Advances 2017, 3(1), e1600821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Province of Ontario. Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006. 2021. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/06p12.

- Province of Ontario. Algonquin Forestry Authority Act, 1990. 1990. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90a17.

- Psaralexi, M. K; Votsi, N-E. P.; Selva, N; Mazaris, A. D.; Pantis, J. D. Importance of Roadless Areas for the European Conservation Network. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinby, P.; Elliott, R.; Quinby, F. Decline of regional ecological integrity: Loss, distribution and natural heritage value of roadless areas in Ontario, Canada. Environmental Challenges 2022, 8, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinby, P. A. Vegetation, Environment and Disturbance in the Upland Forested Landscape of Algonquin Park, Ontario. Ph.D. Thesis, Ontario, University of Toronto, 1988. Available online: https://www.ancientforest.org/_files/ugd/1eacbf_443b9a6ee2964a1eb1c3675e60653a94.pdf.

- Quinby, P. A. An index to fire incidence. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 1987, 17, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, N. W. S. Reconstructing Changes in Abundance of White-tailed Deer, Odocoileus virginianus, Moose, Alces alces, and Beaver, Castor canadensis, in Algonquin Park, Ontario, 1860-2004. Canadian Field Naturalist 2005, 119, 330–342. Available online: https://www.canadianfieldnaturalist.ca/index.php/cfn/article/view/142. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, N. W. S. The pre-settlement hardwood forests and wildlife of Algonquin Provincial Park: A synthesis of historic evidence and recent research. Forestry Chronicle 2004, 80, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J. C.; Grimm, J.; Olive, A. The biodiversity crisis in Canada: failures and challenges of federal and subnational strategic and legal frameworks. FACETS 2021, 6, 1044–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reder, E. Manitoba Duck Mountain Region Audit: Field analysis of logging, provincial park operations, and biodiversity care on public lands. Report, Wilderness Committee, Vancouver, B. C. and Winnipeg, M. B. 2023. Available online: https://www.wildernesscommittee.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/Duck-Mountain-Audit-Report-Web.pdf.

- Remmel, T. Euler, D., Wilton, M., Eds.; An Introduction to the Algonquin Park Ecosystem. In Algonquin Park: The Human Impact ;Algonquin Eco Watch & OJ Graphix Inc.; Espanola, Ontario, 2009; pp. 14–35. Available online: https://www.slbmtrails.org/pdf/2018/Algonquin_Park_the_human_impact_web_2009.pdf.

- Rempel, R. S.; Naylor, B. J.; Elkiec, P. C.; Baker, J.; Churcherd, J.; Gluck, M. J. An indicator system to assess ecological integrity of managed forests. Ecological Indicators 2016, 60, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Spooner, F. The 2024 Living Planet Index reports a 73% average decline in wildlife populations – what’s changed since the last report? OurWorldinData.org. 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/2024-living-planet-index.

- Runyan, C. W.; Stehm, J. Deforestation: Drivers, Implications, and Policy Responses. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M. Parry Sound’s roots in logging, future in logging. Parry Sound North Star, July 20, Parry Sound, Ontario. 2018. Available online: https://www.parrysound.com/community-story/8754000-parry-sound-s-roots-in-logging-future-in-forestry/.

- Sims, M.; Stanimirova, R.; Raichuk, A.; Neumann, M.; Richter, J.; Follett, F.; MacCarthy, J.; Lister, K.; Randle, C.; Sloat, L.; Esipova, E.; Jupiter, J.; Stanton, C.; Morris, D.; Slay, C. M.; Purves, D.; Harris, N. Global drivers of forest loss at 1 km resolution. Environmental Research Letters 2025, 20(7), 074027. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/add606. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I. D.; Guariguata, M. R.; Okabe, K.; Bahamondez, C.; Nasi, R.; Heymell, V.; Sabogal, C. An operational framework for defining and monitoring forest degradation. Ecology and Society 2013, 18(2), 20. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269330. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I. D.; Simard, J. H.; Titman, R. D. Historical changes in white pine (Pinus strobus L.) density in Algonquin Park, Ontario, during the 19th Century. Natural Areas Journal 2006, 26, 61–71. Available online: http://www.naturalareas.org/docs/v26_1_06_pp061_071.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Tierney, G. L.; Faber-Langendoen, D.; Mitchell, B. R.; Shriver, W. G.; Gibbs, J. P. Monitoring and evaluating the ecological integrity of forest ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The triple planetary crisis: Global Foresight Report reveals global shifts. UN News. 2024. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/07/1152136.

- United States Forest Service (USFS). Forests and Grasslands. 2022. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/national-forests-grasslands.

- Vasiliauskas, S. A. Interpretation of age-structure gaps in hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) populations of Algonquin Park. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Biology Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, 1995. Available online: https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/14754.

- Wedeles, C. Euler, D., Wilton, M., Eds.; Impacts of Roads on Algonquin Park Wildlife. In Algonquin Park: The Human Impact ;Algonquin Eco Watch & OJ Graphix Inc.; Espanola, Ontario, 2009; pp. 278–312. Available online: https://www.slbmtrails.org/pdf/2018/Algonquin_Park_the_human_impact_web_2009.pdf.

- Wildlands League. 50 Years, Wildlands League. Wildlands League, Toronto, Ontario. 2000. Available online: https://wildlandsleague.org/50-years/#:~:text=1979%20saw%20a%20shift%20in,later%20known%20as%20wilderness%20parks.

- Williams, J. Euler, D., Wilton, M., Eds.; Moving Towards Sustainable Forest Management. In Algonquin Park: The Human Impact ;Algonquin Eco Watch & OJ Graphix Inc.; Espanola, Ontario, 2009; pp. 174–219. Available online: https://www.slbmtrails.org/pdf/2018/Algonquin_Park_the_human_impact_web_2009.pdf.

- Williams, J. W.; Ordonez, A.; Svenning, J-C. A unifying framework for studying and managing climate-driven rates of ecological change. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2021, 5, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, A. Review on drivers of deforestation and associated socio-economic and ecological impacts. Advances in Agriculture, Food Science and Forestry 2023, 11(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.naturalareas.org/docs/v26_1_06_pp061_071.pdf.

- Wurtzebach, Z.; Schultz, C. Measuring Ecological Integrity: History, Practical Applications, and Research Opportunities; BioScience, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Total Area (ha) | Total Area Protected (ha) | Total RA * (ha) | RA Protected (ha) | RA Un-protected (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algonquin Park (AP) | 761,046 | 175,150 (23%) | 136,704 (18%) | 96,848 (13%) | 39,854 (5%) |

| Georgian Bay-Lake Nipissing (GBLN) | 763,268 | 120,019 (16%) | 181,321 (24%) | 64,467 (8%) | 116,854 (15%) |

| Difference | 2,222 (GBLN 0.3% larger) | 55,131 (AP 46% larger) | 44,617 (GBLN 33% larger) | 32,381 (AP 50% larger) | 77,000 (GBLN 193% larger) |

| Species and Ecological Integrity Metrics | Quantity/ Change |

References |

|---|---|---|

| Species Declines | ||

| Mammals | 3 | beaver (Quinn, 2005), moose (McLaughlin et al., 2011), eastern wolf (Benson et al., 2015) |

| Birds | 12 | barred owl (AES, 2010), blackburnian warbler (AES, 2010), black-throated blue warbler (Jobes et al., 2004), brown creeper (Geleynse et al., 2015), gray jay (OMECP, 2025), oven bird (Jobes et al., 2004), parula warbler (AES, 2010), red-shouldered hawk (Naylor et al., 2004), saw-whet owl (AES, 2010), white-winged crossbill (AES, 2010), wood thrush (AES, 2010) and yellow-bellied sapsucker (Jobes et al., 2004) |

| Fish | 1 | brook trout (Banks, 2009) |

| Crustaceans | 1 | crayfish (Towers, 2015) |

| Insects | 3 | bees (Nol et al., 2006, Nardone, 2013), click beetles (Nol et al., 2006), and hoverflies (Nol et al., 2006) |

| Trees | 13 | American elm (Leadbitter, 2002), basswood (Leadbitter, 2002), black cherry (Leadbitter, 2002), eastern hemlock (AES, 2009), eastern white pine (Quinn, 2004, Thompson et al., 2006), jack pine (Cumming & Janke, 2010), larch/tamarack (Pinto et al., 2006), northern white cedar (Pinto et al., 2006), red oak (Leadbitter, 2002, Cumming & Janke, 2010), red pine (AES, 2009; Pinto et al., 2008), red spruce (Anderson and Gordon, 1990), white cedar (Pinto et al., 2006), and yellow birch (Vasiliauskas, 1995; Pinto et al., 2006) |

| Decline in Ecological Integrity Indicators | ||

| Roadless wildlife habitat | -82% | this study |

| White pine density | -88% | Thompson et al. (2006) |

| White pine tree diameter | -61% | Thompson et al. (2006) |

| White pine stand abundance | -40% | Thompson et al. (2006) |

| Super-canopy trees | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Large snags | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Large logs | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Carbon storage/forest biomass | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Riparian habitat | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Conifer forest | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Canopy cover | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Site productivity | decrease | Quinn (2004) |

| Species-at-risk (residents only) | +17 | Cumming and Janke (2010) |

| Non-native, alien species | +200 | Mead et al. (2000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).