Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Comprehensive and timely review: we present an up-to-date and in-depth survey of adversarial patch attacks and defenses, especially covering works published in the past two years. Compared with existing surveys, our work emphasizes both digital and physical attack settings across a wide range of vision tasks, ensuring timeliness and broader applicability.

- New taxonomy of patch attacks and defenses: we introduce a new, task-oriented taxonomy that systematically categorizes patch attack methods according to their downstream vision applications (e.g., classification, detection, segmentation) and defense mechanisms based on three major strategies. This unified framework provides an integrated perspective that bridges attack and defense research.

- Identification of challenges and future research directions: we summarize open challenges in developing patch-resilient vision systems and discuss promising directions such as adaptive defense frameworks, benchmark standardization, cross-modal robustness, and realistic physical-world evaluations.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Deep Neural Networks in Computer Vision

2.2. Vision-based tasks in ML

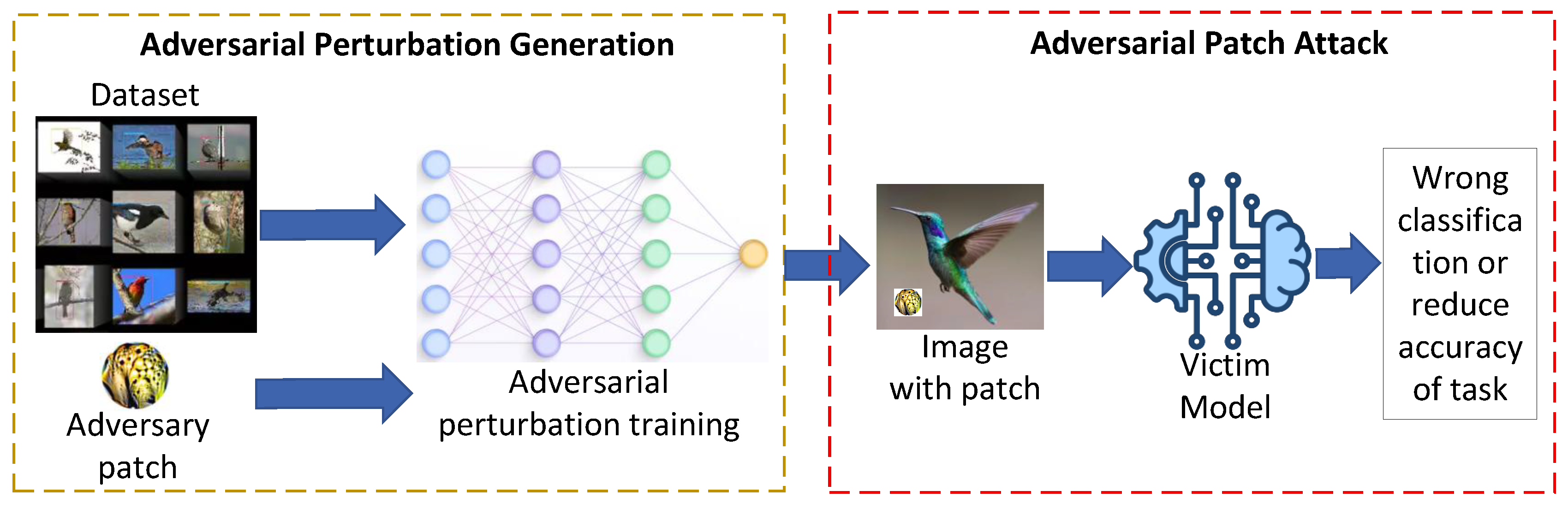

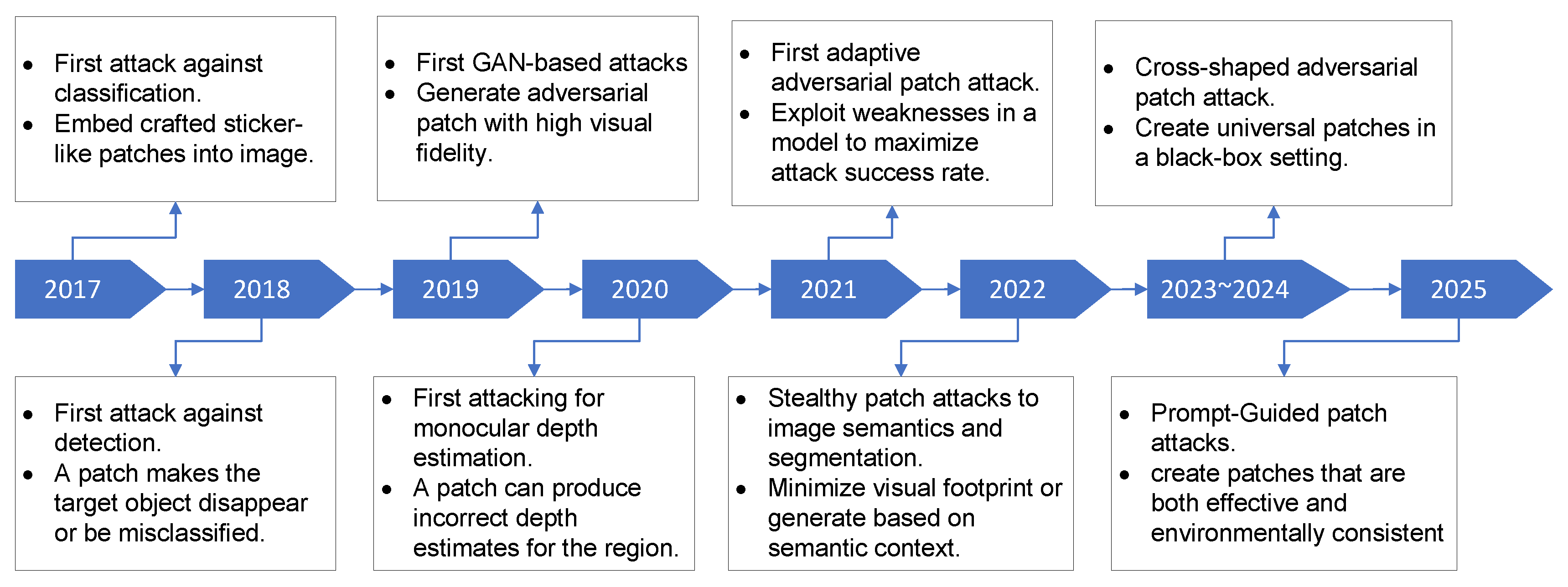

2.3. Adversarial Patch Attacks

- Locality: They affect only a specific region of the input rather than the entire image.

- Visibility: The modifications are usually perceptible to humans, yet remain effective against machine learning models.

- Transferability: A single patch can generalize across multiple inputs and sometimes across different models.

- Physical realizability: Adversarial patches can be printed and deployed in real-world settings, posing threats to autonomous driving, surveillance, and facial recognition.

- Reusability: Once generated, the same patch can be applied repeatedly to achieve consistent attack success.

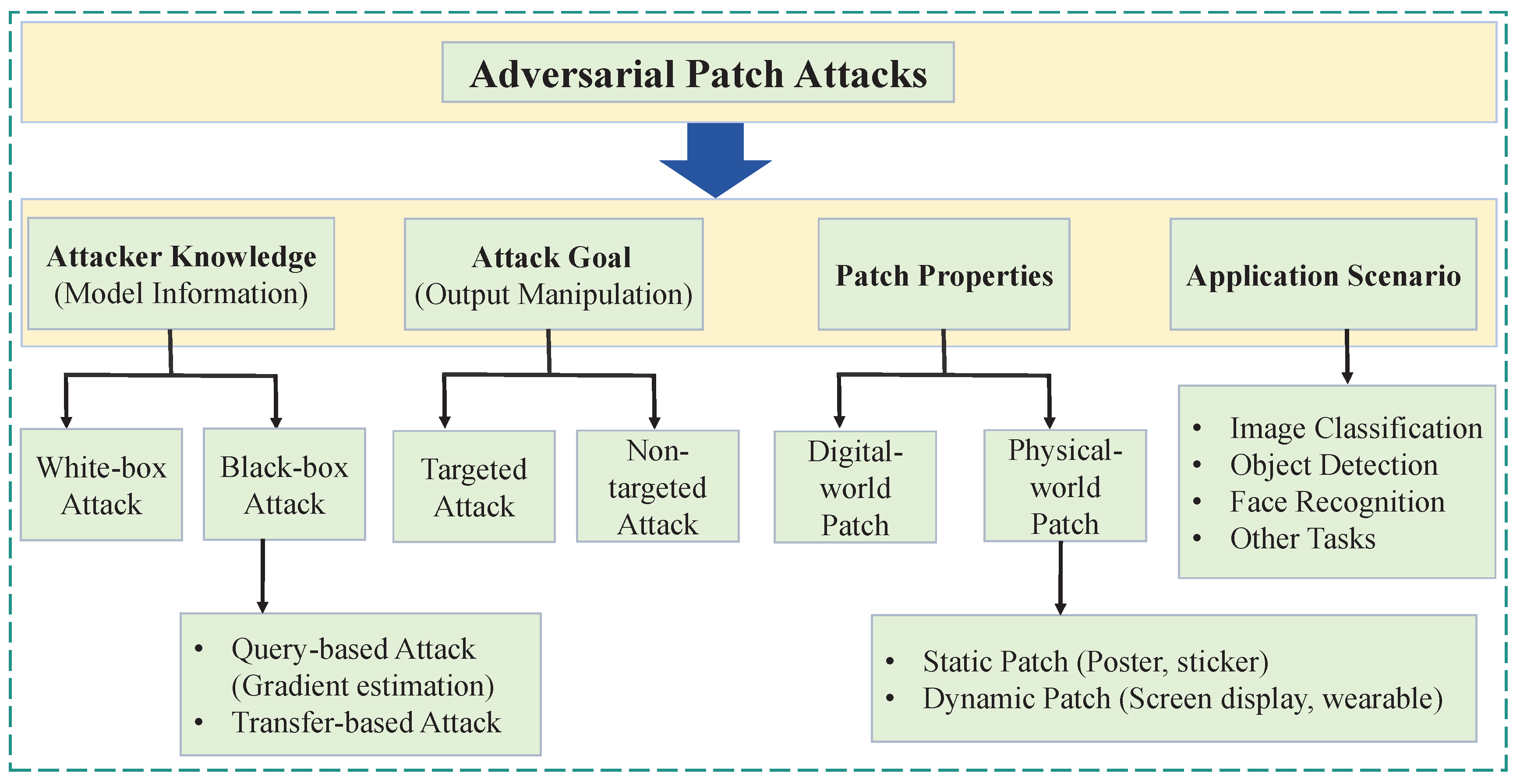

2.3.1. Attacker Knowledge

2.3.2. Attack Goal

2.3.3. Patch Properties

2.3.4. Application Scenario

2.4. Comparison with Other Attack Types

3. Taxonomy of Patch Attack Methods

3.1. Patch Attacks in Image Classification

3.2. Patch Attacks in Image Detection

3.3. Patch Attacks on Other Vision Tasks

4. Defense Methods Against Patch Attacks

4.1. Patch Localization and Removal-Based Defenses

4.2. Input Transformation and Reconstruction-based Defenses

| Ref. & Year | Defense Category | Method / Approach | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. [93], 2024 | Detection-based | Remove adversarial patches by leveraging their semantic independence and spatial heterogeneity | Patch-agnostic, Training-free, Effective across modalities |

| Ref. [95], 2024 | Detection-based | Uses an ensemble of explainable detectors to spot inconsistencies from adversarial patches and raise alerts. | Real-time detection, Explainability, Generalization to new attacks |

| Ref. [98], 2023 | Certified Defenses | Divide the binary into byte chunks and make the final decision by majority voting over chunk predictions. | Chunk-Based Smoothing, Certifiable Robustness, Majority Voting |

| Ref. [96], 2024 | Detection-based | It improves robustness to naturalistic adversarial patches by leveraging their aggressiveness and naturalness. | Targets naturalistic adversarial patches, Feature-level modulation, Improves precision and generalization |

| Ref. [97], 2025 | Detection-based | Detect adversarial patches using a binarized feature map ensemble generated with multiple saliency thresholds | Explicit patch detection, inpainting-based recovery, Low computational complexity |

| Ref. [99], 2024 | Detection-based & Pre-processing | A text-guided diffusion model detects and localizes adversarial patches by identifying distributional differences, then restores the image to remove the perturbations. | Utilizes diffusion models, few-shot tuning |

| Ref. [100], 2024 | Detection-based & Pre-processing | Analyze the visual and feature-level inconsistencies introduced by adversarial patches to locate and filter out adversarial regions | Dual Attack Resistance, High Generalization |

| Ref. [101], 2025 | Detection-based | Apply randomized Fourier-space sampling masks to enhance robustness to occlusion and adversarial perturbations. SAF (Split-and-Fill) Strategy | Fourier-based augmentation, edge-aware segmentation, and adaptive reconstruction. |

4.3. Model Modification and Training-based Defenses

4.4. Task-Specific / Domain-Specific Defenses

4.5. Discussion and Insights

- Effectiveness vs. Generality. Localization and removal-based defenses are intuitive and computationally efficient, but their effectiveness strongly depends on the accuracy of patch detection. In contrast, reconstruction-based approaches using generative models are more general and attack-agnostic, yet they introduce higher computational costs that limit real-time applicability.

- Integration into Learning Pipelines. Model modification and training-based defenses are generally more robust, as they directly improve the resilience of the underlying neural network. However, such methods often require retraining or architectural changes, which may not be feasible in scenarios relying on pretrained or large-scale foundation models.

- Trade-off Between Robustness and Utility. Most defenses need to carefully balance adversarial robustness with preservation of clean image accuracy and efficiency. Over-aggressive patch suppression or reconstruction may harm benign inputs, reducing the utility of the model in practical settings.

5. Future Challenges and Research Directions

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DNN | Deep neural networks |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| ML | Machine Lerning |

| ViTs | Vision Transformers |

References

- Ota, K.; Dao, M.S.; Mezaris, V.; Natale, F.G.D. Deep learning for mobile multimedia: A survey. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM) 2017, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Seff, A.; Kornhauser, A.; Xiao, J. Deepdriving: Learning affordance for direct perception in autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2015, pp. 2722–2730.

- Liu, X.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y. A decentralized digital watermarking framework for secure and auditable video data in smart vehicular networks. Future Internet 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, P.; Esposito, M.; Raavi, M.; Zhao, C. AGFA-Net: Attention-Guided Feature-Aggregated Network for Coronary Artery Segmentation Using Computed Tomography Angiography. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 36th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI). IEEE, 2024, pp. 327–334.

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X.; Fieguth, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Pietikäinen, M. Deep learning for generic object detection: A survey. International journal of computer vision 2020, 128, 261–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Zeng, H.; Li, A.; Ngai, E.W. Deep learning in computer vision: A critical review of emerging techniques and application scenarios. Machine Learning with Applications 2021, 6, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Chen, S.; Xie, X.; Ma, L.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, X. An empirical study towards characterizing deep learning development and deployment across different frameworks and platforms. In Proceedings of the 2019 34th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE). IEEE, 2019, pp. 810–822.

- He, Y.; Meng, G.; Chen, K.; Hu, X.; He, J. Towards security threats of deep learning systems: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2020, 48, 1743–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, R.; Peng, X. BEWSAT: blockchain-enabled watermarking for secure authentication and tamper localization in industrial visual inspection. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Machine Vision and Applications (ICMVA 2025). SPIE, 2025, Vol. 13734, pp. 54–65.

- Xu, R.; Liu, X.; Nagothu, D.; Qu, Q.; Chen, Y. Detecting Manipulated Digital Entities Through Real-World Anchors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications. Springer, 2025, pp. 450–461.

- Lipton, Z.C. The mythos of model interpretability: In machine learning, the concept of interpretability is both important and slippery. Queue 2018, 16, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Dietterich, T. Benchmarking neural network robustness to common corruptions and perturbations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.12261 2019.

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and huffman coding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1510.00149 2015.

- Li, Y.; Xie, B.; Guo, S.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, B. A survey of robustness and safety of 2d and 3d deep learning models against adversarial attacks. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; He, P.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X. Adversarial examples: Attacks and defenses for deep learning. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2019, 30, 2805–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.06083 2017.

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Lu, K.; Song, D. Targeted backdoor attacks on deep learning systems using data poisoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.05526 2017.

- Brown, T.B.; Mané, D.; Roy, A.; Abadi, M.; Gilmer, J. Adversarial patch. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.09665 2017.

- Wei, H.; Tang, H.; Jia, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Li, Z.; Satoh, S.; Van Gool, L.; Wang, Z. Physical adversarial attack meets computer vision: A decade survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024, 46, 9797–9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, F.; Zhao, J.; Nie, C. EAP: An effective black-box impersonation adversarial patch attack method on face recognition in the physical world. Neurocomputing 2024, 580, 127517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Bian, Y.; Munz, P.; Narayan, A. Adversarial patch attacks and defences in vision-based tasks: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.08304 2022.

- Wang, D.; Yao, W.; Jiang, T.; Tang, G.; Chen, X. A survey on physical adversarial attack in computer vision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14262 2022.

- Chakraborty, A.; Alam, M.; Dey, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Mukhopadhyay, D. A survey on adversarial attacks and defences. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology 2021, 6, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Chatterjee, S.; Portfleet, M.; Sun, Y. Understanding human behaviors and injury factors in underground mines using data analytics. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 2459–2462.

- Liu, A.; Liu, X.; Fan, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, A.; Xie, H.; Tao, D. Perceptual-sensitive gan for generating adversarial patches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 1028–1035.

- Kang, H.; Kim, H.; et al. Robust adversarial attack against explainable deep classification models based on adversarial images with different patch sizes and perturbation ratios. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 133049–133061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25.

- Rawat, W.; Wang, Z. Deep convolutional neural networks for image classification: A comprehensive review. Neural computation 2017, 29, 2352–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 779–788.

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 3431–3440.

- Taigman, Y.; Yang, M.; Ranzato, M.; Wolf, L. Deepface: Closing the gap to human-level performance in face verification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2014, pp. 1701–1708.

- Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. Facenet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 815–823.

- Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Song, L.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Dpatch: An adversarial patch attack on object detectors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.02299 2018.

- Song, D.; Eykholt, K.; Evtimov, I.; Fernandes, E.; Li, B.; Rahmati, A.; Tramer, F.; Prakash, A.; Kohno, T. Physical adversarial examples for object detectors. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX workshop on offensive technologies (WOOT 18), 2018.

- Yamanaka, K.; Matsumoto, R.; Takahashi, K.; Fujii, T. Adversarial patch attacks on monocular depth estimation networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 179094–179104.

- Mirsky, Y. Ipatch: A remote adversarial patch. Cybersecurity 2023, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Li, L.C.; Wang, Y.G.; Li, J. Cross-shaped adversarial patch attack. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2023, 34, 2289–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; An, S.; Cheng, S.; Shen, G.; Zhang, X. Hard-label black-box universal adversarial patch attack. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), 2023, pp. 697–714.

- Li, C.; Yan, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, T.; Liu, Z.; Su, H. Prompt-guided environmentally consistent adversarial patch. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10498 2024.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572 2014.

- Chen, P.Y.; Zhang, H.; Sharma, Y.; Yi, J.; Hsieh, C.J. ZOO: Zeroth Order Optimization based Black-box Attacks to Deep Neural Networks without Training Substitute Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security (AISec), 2017, pp. 15–26.

- Ilyas, A.; Engstrom, L.; Athalye, A.; Lin, J. Black-box adversarial attacks with limited queries and information. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2018, pp. 2137–2146.

- Bhagoji, A.N.; He, W.; Li, B.; Song, D. Practical black-box attacks on deep neural networks using efficient query mechanisms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 158–174.

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6199 2013.

- Papernot, N.; McDaniel, P.; Goodfellow, I.; Jha, S.; Celik, Z.B.; Swami, A. Practical black-box attacks against machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2017, pp. 506–519.

- Sharif, M.; Bhagavatula, S.; Bauer, L.; Reiter, M.K. Accessorize to a crime: Real and stealthy attacks on state-of-the-art face recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2016 acm sigsac conference on computer and communications security, 2016, pp. 1528–1540.

- Eykholt, K.; Evtimov, I.; Fernandes, E.; Li, B.; Rahmati, A.; Xiao, C.; Prakash, A.; Kohno, T.; Song, D. Robust Physical-World Attacks on Deep Learning Visual Classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018, pp. 1625–1634.

- Karmon, D.; Zoran, D.; Goldberg, Y. Lavan: Localized and visible adversarial noise. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018, pp. 2507–2515.

- Thys, S.; Van Ranst, W.; Goedemé, T. Fooling Automated Surveillance Cameras: Adversarial Patches to Attack Person Detectors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, 2019, pp. 0–7.

- Hingun, N.; Sitawarin, C.; Li, J.; Wagner, D. REAP: A Large-Scale Realistic Adversarial Patch Benchmark. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2023, pp. 12500–12509.

- Shrestha, S.; Pathak, S.; Viegas, E.K. Towards a robust adversarial patch attack against unmanned aerial vehicles object detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 3256–3263.

- Wang, X.; Li, W. Physical adversarial attacks for infrared object detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Consumer Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICCECE). IEEE, 2024, pp. 64–69.

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, B.; Li, L.; He, R.; Lyu, S. Invisible backdoor attack with sample-specific triggers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 16463–16472.

- Zhou, X.; Pan, Z.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. A data independent approach to generate adversarial patches. Machine Vision and Applications 2021, 32, 67.

- Wang, Z.; Huang, J.J.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, X.; Pan, Y.; Liu, L. Multi-patch adversarial attack for remote sensing image classification. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Web (APWeb) and Web-Age Information Management (WAIM) Joint International Conference on Web and Big Data. Springer, 2023, pp. 377–391.

- Huang, J.J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, T.; Luo, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wang, M. DeMPAA: Deployable multi-mini-patch adversarial attack for remote sensing image classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiliwalidi, K.; Yan, K.; Shi, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhou, J. Cost-effective and robust adversarial patch attacks in real-world scenarios. Journal of Electronic Imaging 2025, 34, 033003–033003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kolter, Z. On physical adversarial patches for object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.11897 2019.

- Wu, S.; Dai, T.; Xia, S.T. Dpattack: Diffused patch attacks against universal object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11679 2020.

- Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ma, K.K. Rpattack: Refined patch attack on general object detectors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.12469 2021.

- Hoory, S.; Shapira, T.; Shabtai, A.; Elovici, Y. Dynamic adversarial patch for evading object detection models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.13070 2020.

- Wang, Y.; Lv, H.; Kuang, X.; Zhao, G.; Tan, Y.a.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, J. Towards a physical-world adversarial patch for blinding object detection models. Information Sciences 2021, 556, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.; Chen, D.; Shi, R.; He, Y. Attention-Guided Digital Adversarial Patches on Visual Detection. Security and Communication Networks 2021, 2021, 6637936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Cheng, G.; Pei, L.; Li, H.; Han, J. Threatening patch attacks on object detection in optical remote sensing images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Jiang, T.; Zhou, W.; Li, C.; Yao, W.; Zhao, Y. Adversarial patch attacks against aerial imagery object detectors. Neurocomputing 2023, 537, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Zhang, D.; Dong, F.; Zhang, J.; Shafiq, M.; Gu, Z. Rust-style patch: A physical and naturalistic camouflage attacks on object detector for remote sensing images. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, F.; He, L. A unified framework for adversarial patch attacks against visual 3D object detection in autonomous driving. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2025.

- Zhu, W.; Ji, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, W. {TPatch}: A triggered physical adversarial patch. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), 2023, pp. 661–678.

- Wei, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hou, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, Z. Revisiting adversarial patches for designing camera-agnostic attacks against person detection. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 8047–8064. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, W.; Ji, X.; Xu, W. {CAPatch}: Physical Adversarial Patch against Image Captioning Systems. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), 2023, pp. 679–696.

- Jiang, K.; Chen, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, D.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Efficient decision-based black-box patch attacks on video recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 4379–4389.

- Liu, A.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Liang, S.; Tao, R.; Zhou, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Tao, D. {X-Adv}: Physical adversarial object attacks against x-ray prohibited item detection. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), 2023, pp. 3781–3798.

- Agrawal, K.; Bhatnagar, C. A black-box based attack generation approach to create the transferable patch attack. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1376–1380.

- Wei, X.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y. Infrared adversarial patches with learnable shapes and locations in the physical world. International Journal of Computer Vision 2024, 132, 1928–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, F.; Jiang, D.; Yan, K. Natural adversarial patch generation method based on latent diffusion model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.16401 2023.

- Lin, C.Y.; Huang, T.Y.; Ng, H.F.; Lin, W.Y.; Farady, I. Entropy-Boosted Adversarial Patch for Concealing Pedestrians in YOLO Models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 32772–32779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, L.; Lyu, S.; Feng, W. Mvpatch: More vivid patch for adversarial camouflaged attacks on object detectors in the physical world. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.17431 2023.

- Wang, S.; Li, W.; Xu, Z.; Yu, N. Learning from the Environment: A Novel Adversarial Patch Attack against Object Detectors Using a GAN Trained on Image Slices. In Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Conference on Electronic Engineering and Information Systems (EEISS). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–6.

- Zhou, D.; Qu, H.; Wang, N.; Peng, C.; Ma, Z.; Yang, X.; Gao, X. Fooling human detectors via robust and visually natural adversarial patches. Neurocomputing 2025, 616, 128915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Xu, G.; Jiang, W.; Ni, T.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, Y. Itpatch: An invisible and triggered physical adversarial patch against traffic sign recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12394 2024.

- Hu, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Gao, H.; Xu, H.; Mu, H.; Wang, Y. Physically structured adversarial patch inspired by natural leaves multiply angles deceives infrared detectors. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2024, 36, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Han, R.; Ma, J. RPAU: Fooling the eyes of UAVs via physical adversarial patches. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 25, 2586–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesti, F.; Rossolini, G.; Nair, S.; Biondi, A.; Buttazzo, G. Evaluating the robustness of semantic segmentation for autonomous driving against real-world adversarial patch attacks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2022, pp. 2280–2289.

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, K.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Digital-to-Physical visual consistency optimization for adversarial patch generation in remote sensing scenes. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiyatno, R.R.; Xu, A. Physical adversarial textures that fool visual object tracking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 4822–4831.

- Ranjan, A.; Janai, J.; Geiger, A.; Black, M.J. Attacking optical flow. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 2404–2413.

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, A.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Tao, D. Harnessing perceptual adversarial patches for crowd counting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2022, pp. 2055–2069.

- Tarchoun, B.; Ben Khalifa, A.; Mahjoub, M.A.; Abu-Ghazaleh, N.; Alouani, I. Jedi: Entropy-based localization and removal of adversarial patches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 4087–4095.

- Xu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Cai, K.; Nevatia, R. Patchzero: Defending against adversarial patch attacks by detecting and zeroing the patch. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 4632–4641.

- Xiang, C.; Valtchanov, A.; Mahloujifar, S.; Mittal, P. Objectseeker: Certifiably robust object detection against patch hiding attacks via patch-agnostic masking. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1329–1347.

- Jing, L.; Wang, R.; Ren, W.; Dong, X.; Zou, C. PAD: Patch-agnostic defense against adversarial patch attacks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 24472–24481.

- Bunzel, N.; Siwakoti, A.; Klause, G. Adversarial patch detection and mitigation by detecting high entropy regions. In Proceedings of the 2023 53rd Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W). IEEE, 2023, pp. 124–128.

- Hofman, O.; Giloni, A.; Hayun, Y.; Morikawa, I.; Shimizu, T.; Elovici, Y.; Shabtai, A. X-detect: Explainable adversarial patch detection for object detectors in retail. Machine Learning 2024, 113, 6273–6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. NAPGuard: Towards detecting naturalistic adversarial patches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 24367–24376.

- Victorica, M.B.; Dán, G.; Sandberg, H. Saliuitl: Ensemble Salience Guided Recovery of Adversarial Patches against CNNs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, 2025, pp. 20360–20369.

- Gibert, D.; Zizzo, G.; Le, Q. Certified robustness of static deep learning-based malware detectors against patch and append attacks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th ACM workshop on artificial intelligence and security, 2023, pp. 173–184.

- Kang, C.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ruan, S.; Chen, Y.; Su, H.; Wei, X. Diffender: Diffusion-based adversarial defense against patch attacks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2024, pp. 130–147.

- Lin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, K.; He, J. I don’t know you, but I can catch you: Real-time defense against diverse adversarial patches for object detectors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 on ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2024, pp. 3823–3837.

- Liu, X.; Shen, F.; Zhao, J.; Nie, C. Radap: A robust and adaptive defense against diverse adversarial patches on face recognition. Pattern Recognition 2025, 157, 110915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Kang, C.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ruan, S.; Chen, Y.; Su, H. Real-world adversarial defense against patch attacks based on diffusion model. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2025.

- Cai, J.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Xia, B.; Mao, Z.; Yuan, W. HARP: Let object detector undergo hyperplasia to counter adversarial patches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2023, pp. 2673–2683.

- Chen, Z.; Dash, P.; Pattabiraman, K. Jujutsu: A two-stage defense against adversarial patch attacks on deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2023, pp. 689–703.

- Yu, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Ma, H. Improving adversarial robustness against universal patch attacks through feature norm suppressing. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023.

- Zheng, Y.; Demetrio, L.; Cinà, A.E.; Feng, X.; Xia, Z.; Jiang, X.; Demontis, A.; Biggio, B.; Roli, F. Hardening RGB-D object recognition systems against adversarial patch attacks. Information Sciences 2023, 651, 119701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, N.; Guesmi, A.; Hanif, M.A.; Ouni, B.; Shafique, M. Oddr: Outlier detection & dimension reduction based defense against adversarial patches. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.12084 2023.

- Liang, J.; Yi, R.; Chen, J.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, H. Securing autonomous vehicles visual perception: Adversarial patch attack and defense schemes with experimental validations. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024.

- Chattopadhyay, N.; Guesmi, A.; Shafique, M. Anomaly unveiled: Securing image classification against adversarial patch attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 929–935.

- Strack, L.; Waseda, F.; Nguyen, H.H.; Zheng, Y.; Echizen, I. Defending against physical adversarial patch attacks on infrared human detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 3896–3902.

- Wu, H.; Yunas, S.; Rowlands, S.; Ruan, W.; Wahlström, J. Adversarial detection: Attacking object detection in real time. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–7.

| Task Category | Ref. & Year | Method / Approach | Key Characteristics | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Segmentation | Ref. [85], 2022 | Extends the Expectation Over Transformation (EOT) paradigm to semantic segmentation. Adversarial patches are printed on billboards and deployed in outdoor driving experiments. | Semantic segmentation (SS), digital and physical attack. | mIoU (mean Intersection-over-Union), ASR(Attack Success Rate) |

| Face recognition | Ref. [48], 2016 | White-box optimization of adversarial patterns. Differentiable end-to-end pipeline through the face-recognition model. | Physically realizable (printed, wearable eyeglass frames). Inconspicuous. | ASR, Dodging results, Impersonation results |

| Remote sensing | Ref. [86], 2024 | Self-supervised harmonization module integrated into patch generation. Aligns patch appearance with background imaging environment. | digital-to-physical visual inconsistency. Self-supervised. Harmonization-guided optimization | ASR, FLOPs |

| Object Tracking | Ref. [87], 2019 | Optimize visually inconspicuous poster textures. Apply Expectation Over Transformation (EOT) for physical robustness. | Inconspicuous / natural-looking textures. Works against regression-based trackers | Success rate of evasion, Visual imperceptibility |

| Optical Flow Estimation | Ref. [88], 2019 | Extend adversarial patch attacks to optical flow networks. Analyze encoder–decoder vs. spatial pyramid architectures. | Patch attacks propagate errors beyond attack region. Patches can distort object motion | End Point Error (EPE), relative degradation. |

| Crowd Counting | Ref. [89], 2022 | Perceptual Adversarial Patch (PAP) framework. Uses adaptive crowd density weighting to capture invariant scale features. | Model-shared perceptual features. Effective in both digital and physical world. | Mean Absolute Error (MAE). Mean Squared Error (MSE). |

| X-ray Detection | Ref. [74], 2023 | Shape-based (not texture) adversarial generation to handle X-ray color/texture fading. Policy-based reinforcement learning to find worst-case placements inside luggage under heavy occlusion. | Texture-free, geometry-driven adversarial agents (metal objects). Designed for physical realizability (3D-printable). | ASR, Detection accuracy / mAP drop |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).