Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Comparative Analysis and Evaluation of AI Algorithms in Agricultural Pest Detection

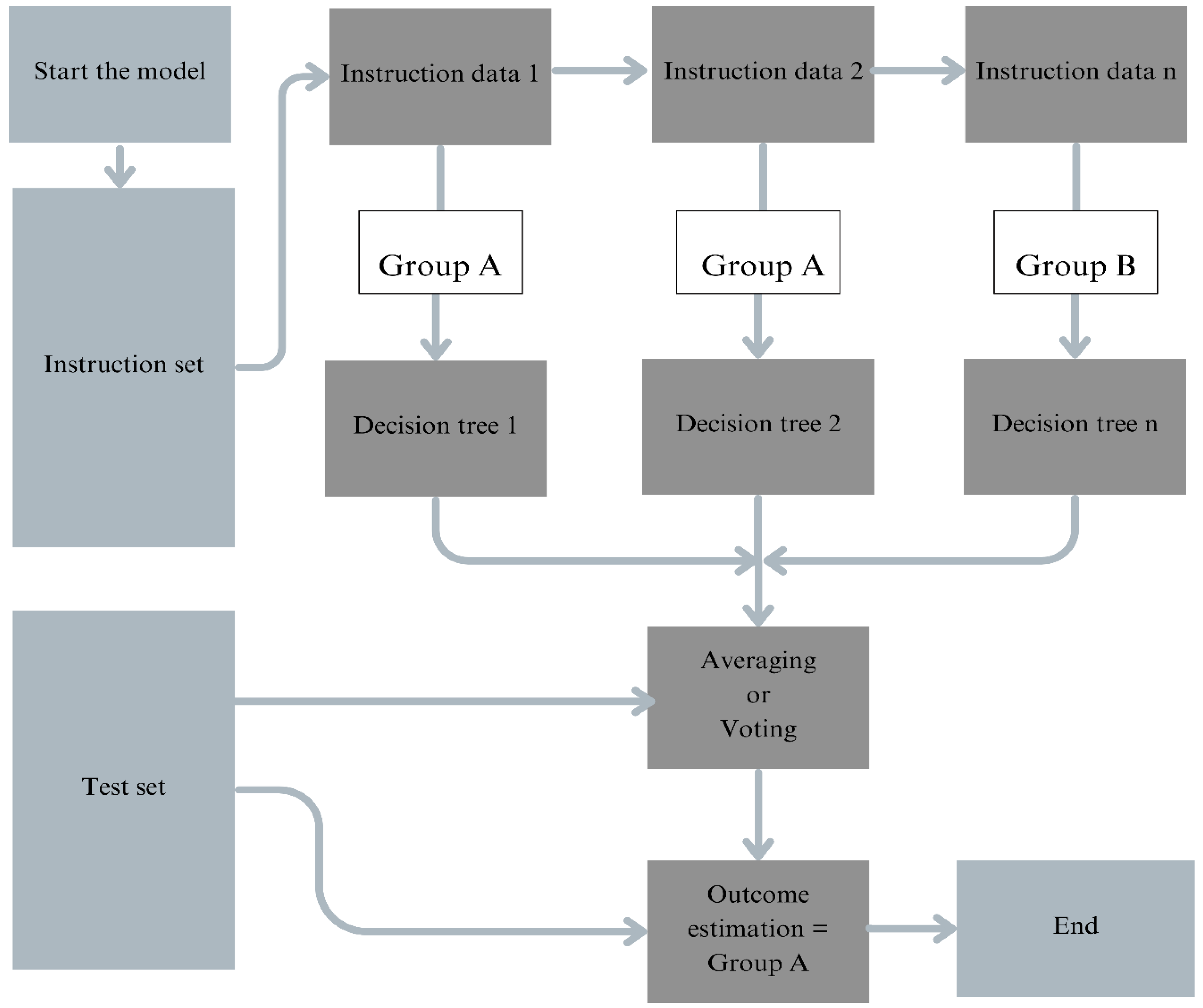

2.1. Random Forest

2.2. CNN

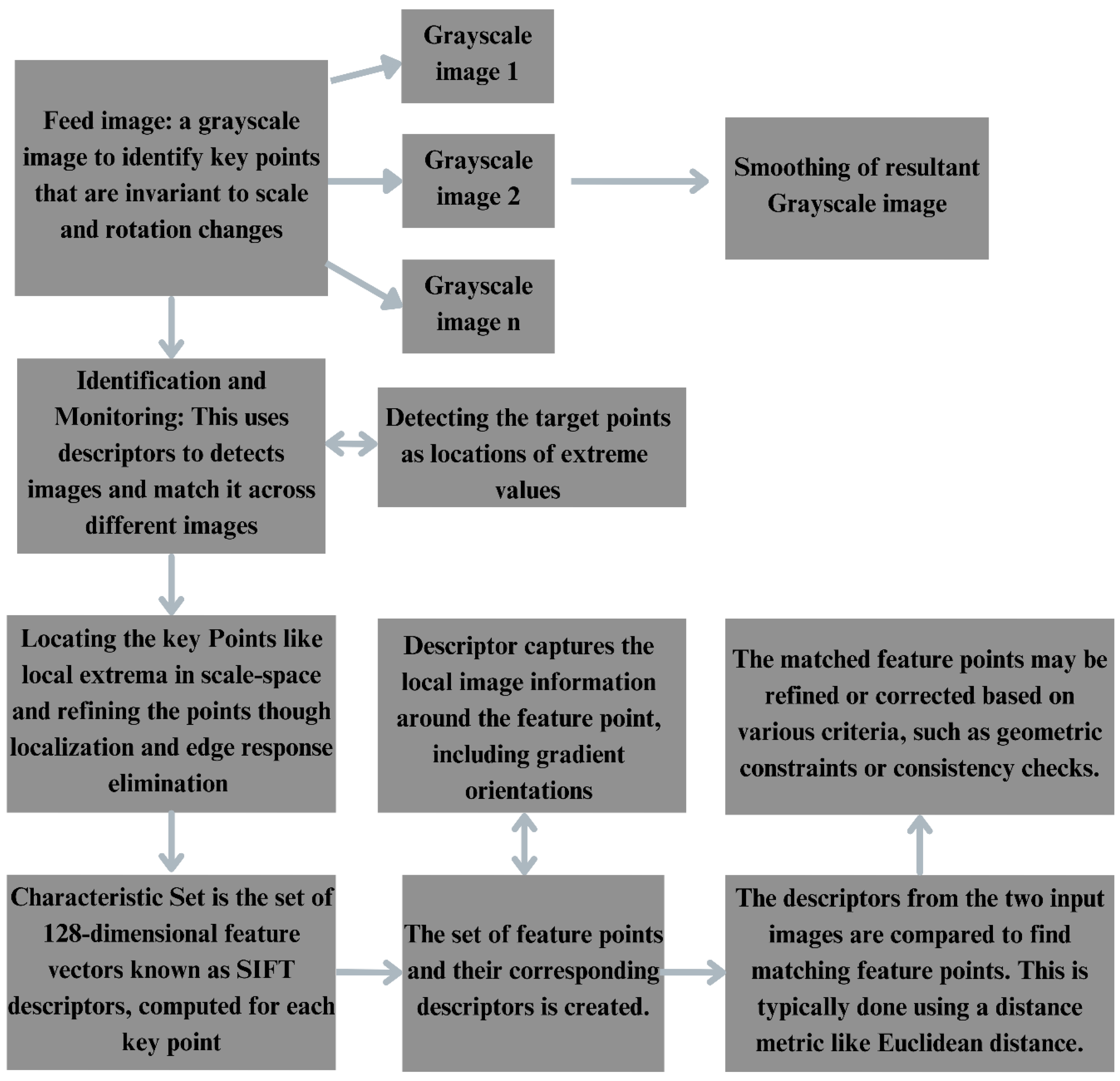

2.3. SIFT

2.4. HOG

2.5. RNN

2.6. GANs

2.7. SVM

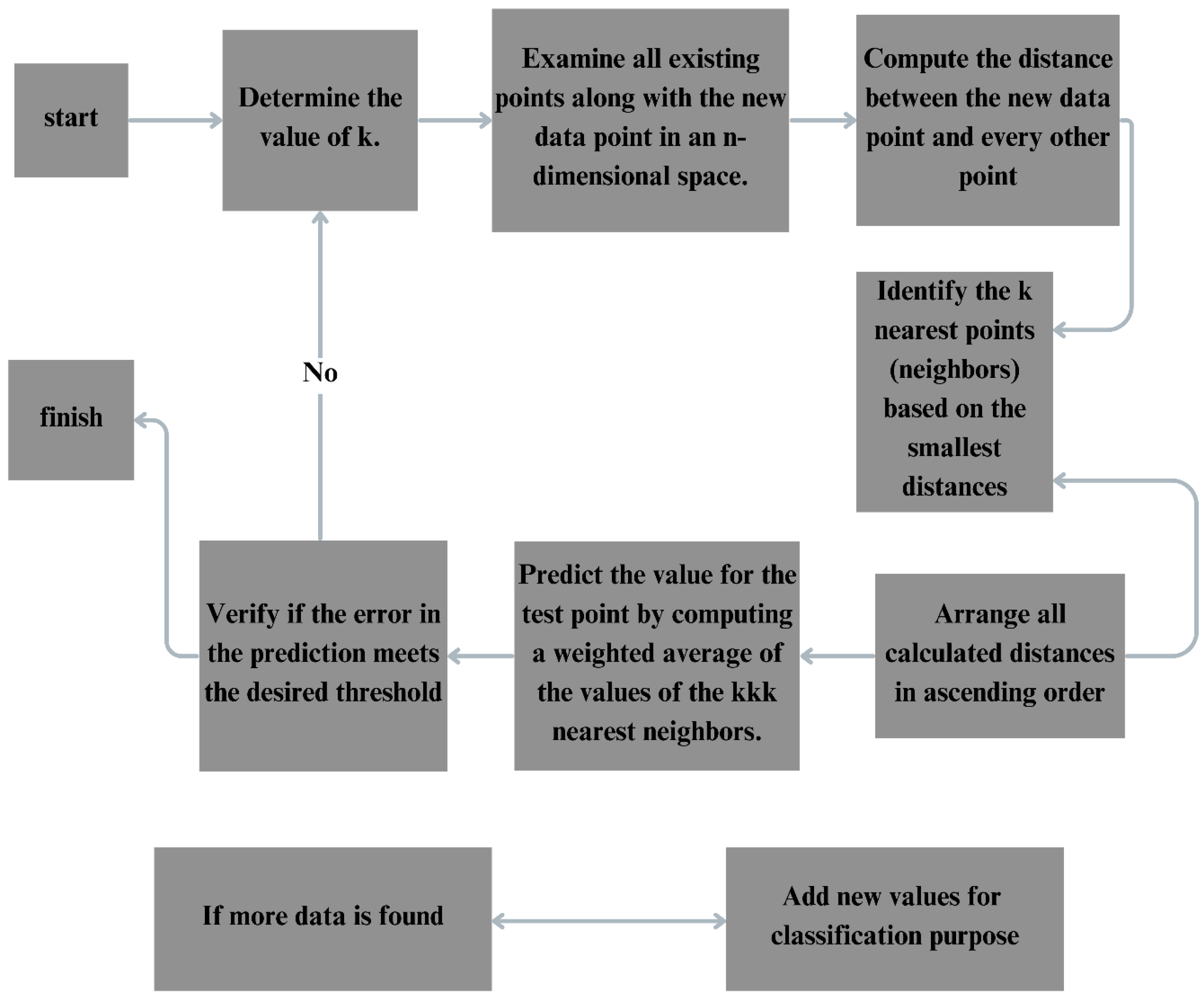

2.8. K-Nearest Neighbours

2.9. Transformer Networks

2.10. Naive Bayes

2.11. Gradient Boosting Machines

2.12. Support Vector Regressors

2.13. CNN-LSTM

2.14. Transfer Learning

2.15. Meta-Learning

3. Comparison of Performance Metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score)

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Confusion matrix | Specificity | Log Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forests | High (>85%): Indicates strong overall performance, especially on structured data. Handles missing data well and works well with imbalanced datasets. | High (>0.8): High recall shows that the model captures most of the positive cases. | High (>0.8): High recall shows that the model captures most of the positive cases. | Balanced: Many true positives and true negatives, with fewer false positives and negatives. | Balanced: Many true positives and true negatives, with fewer false positives and negatives. | Balanced: Many true positives and true negatives, with fewer false positives and negatives. | Balanced: Many true positives and true negatives, with fewer false positives and negatives. |

| CNNs | Very High (>90%): Excellent performance, especially in image-related tasks. Frequently used in computer vision, classification, and object detection. |

High (>0.85): Strong precision with few false positives in image classification. | High (>0.85): High recall captures most of the positive cases in the dataset. | High (>0.85): The model is balanced, with good precision and recall performance. | Dominated by True Positives: The model performs well in distinguishing between classes, with fewer misclassification | High (>0.9): Effective in identifying negative classes, minimizing false positives in image-based tasks. | Very Low (<0.15): Indicates that predictions are well-calibrated and close to actual values, which is common in well-trained CNNs. |

| RNNs | High (>85%): Good performance in sequential tasks, such as time-series or language. | Moderate (>0.7): Precision may be lower than in other models, as RNNs can struggle with false positives in noisy sequences. | Moderate (>0.7): Recall can be compromised due to issues with long-term dependencies or vanishing gradients. | Moderate (>0.75): Balanced, but may need improvement in handling long-term dependencies. | Imbalanced: RNNs may have more false positives or negatives due to difficulties with sequential data dependencies. | Moderate (>0.8): It is able to correctly identify negative cases, but the sequential nature can cause some issues with specificity. | Moderate (<0.3): The model's loss is moderate, suggesting that there may still be room for improvement in prediction accuracy. |

| GANs | N/A (Generative): GANs do not use traditional classification metrics. The focus is on generating realistic synthetic data. | N/A: Precision doesn't apply, as GANs generate rather than classify data. | N/A: Recall is not used as GANs do not perform classification tasks. | N/A: F1-score is not applicable in a generative setting. | Not applicable: GANs are designed for generation rather than classification, so confusion matrix doesn't apply. | N/A: Specificity is not directly applicable in generative tasks. | N/A: Log loss is not used, but metrics like Inception Score or FID are used to evaluate GAN performance. |

| Transformer Networks | High (>85%): Efficient for tasks like NLP and machine translation. Handles long-range dependencies very well. |

High (>0.8): Precision is strong, as the transformer is good at distinguishing between classes. | High (>0.8): High recall means the model captures most of the positive cases, especially in NLP tasks. | High (>0.85): Balanced performance with high precision and recall. | Balanced: The model excels in correctly classifying both positive and negative cases with minimal errors. | High (>0.9): Effective in correctly identifying negatives, minimizing false positives. | Low (<0.2): Log loss is low, indicating well-calibrated probabilities and strong performance in NLP tasks. |

| MobileNet | High due to computational efficiency and small size. High (Good) is >90% and Low (Poor) is <70% | Tasks with unbalanced class distribution, minority classes may perform less accurately. High (Good) is >0.8 and Low (Poor) <0.5 | Class imbalance can negatively impact recall for minority classes. Data augmentation can enhance recall by diversifying training data and mitigating overfitting. | Can achieve good F1-scores when the task requires a balance between precision and recall. | High Performance: Many true positives and true negatives with few false positives and false negatives. Low Performance: Few true positives/negatives with many false positives/negatives |

Above 0.9 indicates good true negative prediction and below 0.6 indicates many false positives | Lower is better. Close to 0 is rare but perfect. Less than 0.2 is very good and above 0.5 is poor prediction. |

| Inception | High (>90%): Excellent performance in image classification, specifically for hierarchical image recognition. | High (>0.85): Good at minimizing false positives in complex image tasks. | High (>0.85): Captures most positive cases with deep feature extraction. | High (>0.85): Well-balanced performance, combining high precision and recall. | Balanced: Few misclassifications with strong class separations. | High (>0.9): Effectively differentiates negative cases in complex image categories. | Very Low (<0.15): Predictions are well-calibrated, yielding highly accurate outputs. |

| DenseNet | High (>90%): Superior accuracy due to dense layer connectivity. | High (>0.85): Few false positives due to efficient feature reuse. | High (>0.85): Strong recall for detailed pattern recognition. | High (>0.85): Balanced precision and recall for deep classification tasks. | Dominated by True Positives and True Negatives: Efficient classification with dense connectivity. | High (>0.9): High specificity by reducing classification errors. | Very Low (<0.15): Log loss is low due to efficient learning with fewer parameters. |

| NASNet | High (>90%): Neural architecture search yields high-performing models for image tasks. | High (>0.85): Reduces false positives through optimized architecture search. | High (>0.85): High recall for many classes. | High (>0.85): Maintains balance between precision and recall. | Balanced: Architecture search minimizes classification errors. | High (>0.9): Excellent at identifying negative cases. | Very Low (<0.15): Optimized architectures result in well-calibrated predictions. |

| EfficientNet | High (>90%): Scales well across different sizes of image datasets. | High (>0.85): Efficient in reducing false positives using compound scaling. | High (>0.85): Captures most relevant features for classification. | High (>0.85): Balanced and optimized for precision and recall. | Balanced: Handles complex image categories effectively. | High (>0.9): Minimizes false negatives with compound scaling. | Very Low (<0.15): Log loss is minimal due to efficient parameterization. |

| SVMs | High (>85%): Strong performance in binary and multiclass classification. | High (>0.8): Good precision by maximizing the margin between classes. | Moderate (>0.7): Depends on kernel choice; may sacrifice recall for precision. | High (>0.8): Balanced if kernel tuning is appropriate. | Balanced: Optimal separation of classes with support vectors. | High (>0.9): Reduces false positives effectively. | Low (<0.25): Log loss is generally low for well-tuned models. |

| Naive Bayes | Moderate (>75%): Assumes feature independence, which may affect accuracy. | Moderate (>0.7): Precision is affected if class distributions are skewed. | Moderate (>0.7): Performs well for well-separated classes. | Moderate (>0.7): Works best with strong independence assumptions. | Imbalanced: Sensitive to class priors and distributions. | Moderate (>0.7): Specificity depends on the dataset's class balance. | Moderate (<0.4): Can suffer from poor probability estimation. |

| K-Nearest Neighbours | Moderate (>80%): Performance depends on choice of k and distance metric. | Moderate (>0.75): Precision depends on neighbor voting majority. | Moderate (>0.75): Recall varies with k-value and noise sensitivity. | Moderate (>0.75): Balanced performance for appropriate k and distance. | Imbalanced: Sensitive to outliers and noise. | Moderate (>0.8): Specificity depends on proper parameter tuning. | Moderate (<0.3): Log loss increases with poor neighbor choices. |

| CNN-LSTM | High (>85%): Combines spatial and temporal features for robust accuracy. | High (>0.8): Precision improves for spatiotemporal tasks like video classification. | High (>0.8): Recall is strong due to LSTM’s sequential modeling. | High (>0.8): Balanced F1-score by leveraging CNN for spatial and LSTM for sequential patterns. | Balanced: Good at both positive and negative classifications in sequence data. | High (>0.9): Effectively identifies negatives in spatiotemporal data. | Low (<0.25): Well-calibrated predictions due to combined architectures. |

| Attention Mechanisms | High (>90%): Enhances accuracy by focusing on relevant features. | High (>0.85): Reduces false positives by selectively attending to key information. | High (>0.85): Strong recall due to dynamic attention weights. | High (>0.85): Balanced precision and recall for tasks like machine translation. | Balanced: Few false positives/negatives due to effective weighting. | High (>0.9): Specificity improves with reduced noise influence. | Very Low (<0.15): Attention optimizes loss by emphasizing key inputs. |

| Ensemble Methods | High (>85%): Combines weak learners for superior accuracy. | High (>0.8): Reduces variance and bias, improving precision. | High (>0.8): High recall by aggregating multiple models. | High (>0.8): Balanced with reduced overfitting. | Balanced: Few false positives/negatives by combining predictions. | High (>0.9): Specificity improves by averaging predictions. | Low (<0.25): Loss is minimized through model aggregation. |

| Decision Trees | Moderate (>80%): Can overfit without pruning. | Moderate (>0.75): Precision varies with tree depth and splits. | Moderate (>0.75): Recall can be high, but prone to overfitting. | Moderate (>0.75): Balance depends on pruning and tree depth. | Imbalanced: High sensitivity to data splits. | Moderate (>0.8): Specificity depends on pruning. | Moderate (<0.3): High depth increases log loss. |

| Gradient Boosting Machines | High (>85%): Boosting improves weak learners for better accuracy. | High (>0.8): Precision is high, reducing false positives. | High (>0.8): High recall with iterative improvement. | High (>0.8): Balanced and robust to overfitting. | Balanced: Reduces misclassifications progressively. | High (>0.9): Specificity improves with boosting. | Low (<0.25): Loss decreases with boosting iterations. |

| Support Vector Regressors | High (>85%): Excellent for regression tasks with clear margins. | N/A: Precision not used in regression. | N/A: Recall is not applicable. | N/A: F1-score not relevant. | N/A: No confusion matrix for regression. | High (>0.9): Effectively distinguishes ranges of values. | Low (<0.25): Log loss correlates to margin fitting. |

| Gaussian Processes | High (>85%): Non-parametric, flexible model. | High (>0.8): Good precision for probabilistic outputs. | High (>0.8): Strong recall due to Bayesian inference. | High (>0.8): Balanced predictions with uncertainty quantification. | Balanced: Models full predictive distributions. | High (>0.9): Specificity from smooth function fitting. | Low (<0.25): Models uncertainty with low error. |

4. Combination of Different Algorithms Used to Detect Specific Agricultural Crops

5. Optimization for Mobile Applications: Developing Lightweight AI Models for Real-Time Detection

5.1. Model Compression Techniques

5.2. Efficient Model Architectures

6. 3D-Printed Sensors and Devices for Precision Agriculture

6.1. Deep Learning for 3D Insect Detection and Monitoring In Plants

6.1.1. Design of a 3D Monitoring System

6.1.2. Insect Detection and Classification Using 3D Monitoring System

6.2. 3D-Printed Synthetic Skin for Mosquito Research

6.3. 3D-Printed Drones for Agricultural Pest Control

6.3.1. Design and production of the SoleonAgro drone for Trichogramma Egg Distribution

6.3.2. Advantages of 3D Printing for Lightweight and Durable Drones

7. Advancements in Agricultural Pest Detection and Management Using Complex Logic Gates

7.1. Sensor Systems

7.2. Image and Video Analysis

7.3. Autonomous Robots and Drones

7.4. Tools for Assessment of Data and Decision Support

8. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgement

References

- Xian, Tan Soo; Ngadiran, Ruzelita. Plant diseases classification using machine learning. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 1962(No. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demilie, Wubetu Barud. Plant disease detection and classification techniques: a comparative study of the performances. Journal of Big Data 2024, 11(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, Garima; Das, Majolica; Dey, Naiwrita. Plant disease detection using CNN. 2020 IEEE applied signal processing conference (ASPCON); IEEE, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Sk Mahmudul; et al. Identification of plant-leaf diseases using CNN and transfer-learning approach. Electronics 2021, 10.12, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulent, Justine; et al. Convolutional neural networks for the automatic identification of plant diseases. Frontiers in plant science 2019, 10, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Feng; et al. Research on image detection and matching based on SIFT features. 2018 3rd International conference on control and robotics engineering (ICCRE); IEEE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinini, Paolo; Prati, Andrea; Cucchiara, Rita. Real-time object detection and localization with SIFT-based clustering. Image and Vision Computing 2012, 30.8, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Rodríguez; Marcos, José. Computer vision for Pedestrian detection using Histograms of Oriented Gradients; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, Navneet; Triggs, Bill. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. 2005 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR'05); 2005; Vol. 1. Ieee. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Wei; Chen, Yupeng; Xue, Qiongying. Survey on research of RNN-based spatio-temporal sequence prediction algorithms. Journal on Big Data 2021, 3.3, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, N.; Karthick, T. A Hybrid Approach for Plant Disease Detection Using E-GAN and CapsNet. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 46.1, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yu; et al. A hybrid approach for rice crop disease detection in agricultural IoT system. Discover Sustainability 2024, 5.1, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Rajleen; Kang, Sandeep Singh. An enhancement in classifier support vector machine to improve plant disease detection. 2015 IEEE 3rd International Conference on MOOCs, Innovation and Technology in Education (MITE); IEEE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Kai-Ying; et al. Using SVM based method for equipment fault detection in a thermal power plant. Computers in industry 2011, 62.1, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Shahadat; et al. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Scientific Reports 2022, 12.1, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunk, Kashvi; et al. A brief review of nearest neighbor algorithm for learning and classification. 2019 international conference on intelligent computing and control systems (ICCS); IEEE, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ohagi, Masaya; Aizawa, Akiko. Pre-trained transformer-based citation context-aware citation network embeddings. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Matthew Chung Hai; et al. TETRIS: Template transformer networks for image segmentation with shape priors. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2019, 38.11, 2596–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanapriya, K.; Balasubramani, M. Recognition of unhealthy plant leaves using Naive Bayes classifier. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing, 2019; Vol. 561. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan, Adhe; Pading, Jonathan. Naive Bayes Method in Determining Diagnosis of Corn Plant Disease. Journal of Knowledge Engineering and Artificial Intelligence 2022, 1.1, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kiangala; Kahiomba, Sonia; Wang, Zenghui. An effective adaptive customization framework for small manufacturing plants using extreme gradient boosting-XGBoost and random forest ensemble learning algorithms in an Industry 4.0 environment. Machine Learning with Applications 2021, 4, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, P.; et al. Artificial flora algorithm-based feature selection with gradient boosted tree model for diabetes classification. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 2021, 14, 2789. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda, Yukimasa; Shibata, Shun; Mineno, Hiroshi. Multi-modal sliding window-based support vector regression for predicting plant water stress. Knowledge-Based Systems 2017, 134, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yankun; Shao, Xueguang; Cai, Wensheng. A consensus least squares support vector regression (LS-SVR) for analysis of near-infrared spectra of plant samples. Talanta 2007, 72.1, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tianyuan; et al. A hybrid CNN–LSTM algorithm for online defect recognition of CO2 welding. Sensors 2018, 18.12, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, Mahmoud; et al. A hybrid CNN-LSTM based approach for anomaly detection systems in SDNs. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Aydin; et al. Analysis of transfer learning for deep neural network based plant classification models. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2019, 158, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Xue; et al. Meta-learning shows great potential in plant disease recognition under few available samples. The Plant Journal 2023, 114.4, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, Iqbal H.; et al. Mobile data science and intelligent apps: concepts, AI-based modelling and research directions. Mobile Networks and Applications 2021, 26.1, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Yunbin. Deep learning on mobile devices: a review. Mobile Multimedia/Image Processing, Security, and Applications 2019, 2019 10993, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Otani, Tomoyuki; et al. Application of AI to mobile network operation. ITU Journal: ICT Discoveries, Special Issue 2017, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Wonsub; et al. Deep learning-based system development for black pine bast scale detection. Scientific reports 2022, 12.1, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, Ana Cláudia; et al. A systematic review on automatic insect detection using deep learning. Agriculture 2023, 13.3, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luker, Hailey A. A critical review of current laboratory methods used to evaluate mosquito repellents. Frontiers in Insect Science 2024, 4, 1320138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azfar, Saeed; et al. Monitoring, detection and control techniques of agriculture pests and diseases using wireless sensor network: a review. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2018, 9.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Architecture | Accuracy (%) | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|

| ResNet50 | ~95.61 | Deep architecture with skip connections |

| InceptionV3 | >98 | Multi-scale feature extraction |

| EfficientNetB0 | >98 | Scalable architecture with high efficiency |

| MobileNetV2 | ~97 | Lightweight model suitable for mobile applications |

| Custom CNN | Comparable to pre-trained models | Tailored design for specific datasets |

| Algorithm Name | Description | Sub-group implementations | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forests | Ensemble learning method combining decision trees | scikit-learn, XGBoost | Robustness to noise, interpretability | Classification, regression |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks for image-based tasks | VGG, ResNet, Inception, MobileNet, EfficientNet, ShuffleNet, SqueezeNet | Convolutional layers for extracting spatial features, pooling layers for down sampling | Image classification, object detection, image segmentation |

| SIFTs | Scale-Invariant Feature Transform for image-based tasks | OpenCV, scikit-image, VLFeat, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Ability to handle changes in scale and rotation, invariant to illumination changes | Object recognition, image matching, 3D reconstruction |

| HOG | Histogram of oriented gradients is a feature descriptor in computer vision and image processing | OpenCV, scikit-image | Captures local shape and appearance, robust to lighting changes, focuses on gradient orientation | Object detection, image feature extraction |

| RNNs | Recurrent Neural Networks for sequential data | LSTM, GRU, RNN, SimpleRNN, Bidirectional RNN | Ability to handle sequential data, memory cells for capturing temporal dependencies | Natural language processing, time series analysis, speech recognition |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks for data generation | DCGAN, StyleGAN, CycleGAN, Pix2Pix | Generative and discriminative models working together, ability to generate realistic data | Image generation, style transfer, data augmentation |

| SVMs | Support Vector Machines for classification and regression | LibSVM, scikit-learn | Kernel trick for mapping data into a higher-dimensional space | Classification, regression |

| K-Nearest Neighbours | Classifies data based on similarity to nearby points | scikit-learn, NLTK | Simple and intuitive, suitable for small datasets | Classification, regression |

| Transformer Networks | Designed for natural language processing, but applicable to image analysis | BERT, GPT, Vision Transformer, DETR, Mask R-CNN | Attention mechanism for capturing long-range dependencies, self-attention | Natural language processing, image classification, object detection |

| Naive Bayes | Probabilistic classifier based on Bayes' theorem | scikit-learn, NLTK | Simple and efficient, suitable for large datasets | Text classification, spam filtering |

| Gradient Boosting Machines | Ensemble learning method that combines multiple weak learners | XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost | Powerful performance, robustness | Classification, regression |

| Support Vector Regressors | SVMs for regression tasks | scikit-learn, LibSVM | Effective for regression problems, especially with complex relationships | Regression analysis |

| CNN-LSTM | Combining CNNs and LSTMs for sequential data | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Effective for tasks involving both spatial and temporal information | Video analysis, time series forecasting |

| Transfer Learning | Reusing pre-trained models on new tasks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Efficient training, improved performance on limited data | Image classification, object detection |

| Meta-Learning | Learning to learn, enabling models to adapt to new tasks quickly | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Faster adaptation to new tasks, improved generalization | Few-shot learning, continual learning |

| MobileNet | Lightweight CNN designed for mobile devices | MobileNetV1, MobileNetV2, MobileNetV3, MobileNetV4 | Efficient architecture, optimized for low-power devices | Mobile applications, embedded systems |

| Inception | Deep neural networks with multiple convolutional layers | InceptionV1, InceptionV2, InceptionV3, Inception-ResNet-v1, Inception-ResNet-v2 | Efficient use of computational resources, improved accuracy | Image classification, object detection |

| DenseNet | Network where each layer is connected to all preceding layers | DenseNet-121, DenseNet-169, DenseNet-201, DenseNet-264, DenseNet-BC | Efficient feature reuse, reduced overfitting | Image classification, object detection |

| NASNet | Neural architecture search network | NASNet-A, NASNet-B | Automatically discovers efficient architectures, tailored to specific tasks | Image classification, object detection |

| EfficientNet | Scaling methods for improving accuracy while maintaining efficiency | EfficientNet-B0, EfficientNet-B1, EfficientNet-B7, EfficientNet-B8, EfficientNet-L2 | Scaling techniques that balance depth, width, and resolution | Image classification, object detection |

| Attention Mechanisms | Focusing on relevant parts of the image | Transformer models, custom implementations | Ability to focus on important features, improved performance | Image classification, object detection, natural language processing |

| Ensemble Methods | Combining multiple algorithms | Random Forest, AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting | Improved accuracy, robustness to overfitting | Various tasks, including classification and regression |

| Decision Trees | Simple, tree-based models for classification and regression | scikit-learn, XGBoost | Interpretability, easy to understand | Classification, regression |

| Gaussian Processes | Probabilistic models for regression and classification | GPy, scikit-learn | Non-parametric approach, flexible modelling | Regression, classification |

| Neural Networks | General-purpose machine learning models with multiple layers | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Flexibility, ability to learn complex patterns | Various tasks, including classification, regression, and generation |

| Autoencoders | Unsupervised learning models for feature extraction and dimensionality reduction | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Learning latent representations of data | Feature extraction, anomaly detection |

| Algorithm | Year | Algorithm Focus | Crop | Studies | Time span |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histogram of an Oriented Gradient (HOG) | 2024 | Detecting chili leaf disease using the HOG algorithm with Euclidean distance | Chili leaf disease | 640 | 2020-2024 |

| Transfer learning (TL); CNNs; ResNet-50; Vision transformer (ViT) | 2023 | Classification of potato plant leaf Disease using 3 different approaches |

Potato plant leaf disease | 100 | 2000-2024 |

| Region Proposal Network, Chan–Vese (CV) Algorithm, Transfer Learning Model | 2020 | Detection of multiple plant diseases using various deep-learning algorithms | Leaves with diseases such as black rot, bacterial plaque, and rust | 9 | 2000-2024 |

| CNN | 2019 | Detecting disease in corn crop using CNN model architecture | Corn/ Maze | 353 | 2014-2024 |

| SIFT | 2019 | Identification of Sunflower leaf disease using the SIFT point algorithm | Sunflower leaf | 10 | 2004-2024 |

| K-nearest neighbor (KNN), Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) | 2019 | Classification of diseases based on texture features extracted from segmented leaf images. | Tomatoes, Potatoes, Mango, Beans, Cotton, Citrus | 64 | 2010-2024 |

| Decision Trees, Texture and Color Features | 2018 | Classification of plant diseases using decision trees based on texture and color features extracted from the leaves. | Apple, Peach, Grapes | 438 | 2024 |

| K-means Clustering, Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 2017 | Segmenting disease-affected regions and classifying the disease based on color and texture features. | Cucumber, Mango and Grapes | 191 | 2000-2024 |

| YCbCr Color Space, Color-Based Segmentation | 2017 | Color-based segmentation and disease detection in Mango | Mango | 84 | 2000-2024 |

| K-means Clustering, Gabor Filters, SVM | 2017 | Image segmentation and texture feature extraction for disease detection in Citrus leaf | Citrus | 474 | 2017-2024 |

| RGB to HSI Conversion, Otsu Thresholding, Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 2017 | Disease detection based on color space conversion and texture analysis. | Various plants | 952 | 2022-2024 |

| K-means, Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 2017 | Image segmentation and feature extraction to classify the following plant leaf diseases based on texture and color features. | Grapes, Tomatoes, Cucumber | 222 | 2016-2024 |

| Image Segmentation, Neural Networks | 2017 | Automated recognition of plant diseases using image segmentation and neural networks to classify infected areas. | Cucumber and Pepper | 565 | 2024 |

| Fuzzy Logic, Image Processing | 2017 | Diagnosis of wheat leaf diseases using fuzzy logic-based decision-making to classify different leaf diseases. | Wheat | 891 | 2024 |

| Thresholding, Region Growing, Neural Networks | 2016 | Pepper leaf disease detection and classification through segmentation and neural network-based classification. | Pepper | 856 | 2022-2024 |

| CNN and k-means Clustering |

2015 | Potato and Pomegranate leaf Disease detection using image processing and machine learning |

Potato and Pomegranate leaf | 312 | 2000 - 2024 |

| Neural Networks, Image Processing Techniques | 2013 | Classification of diseases in grape leaves based on extracted features like texture. | Grapes | 12 | 2000-2024 |

| Color Transform (RGB to HSI, YCbCr), Thresholding, Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 2012 | Disease spot detection through color transformation and feature extraction to classify the following different plant leaf diseases. | Rice, Cucumber, Grapes | 75 | 2013-2014 |

| Thresholding, K-means Clustering, Region Growing | 2011 | Automatic disease detection in crop leaves by segmenting diseased areas using local thresholding and region growing methods. | Crop plants | 100 | 2000-2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).