1. Introduction

Anomaly detection is a critical issue in machine

learning, with applications in manufacturing, industrial process control,

medical diagnosis, cybersecurity, and disaster management [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The primary objective is to learn a

representation of normal operating conditions and identify deviations as

anomalies. Unlike standard supervised classification, anomaly detection is

characterized by severe class imbalance, where anomalies are rare, diverse, and

often scarcely labeled, while normal samples are abundant. However, despite

this abundance, labeling a sample as truly normal is often costly and

challenging. In many operational settings, normal labeling requires expert

review against process specifications, additional quality-control checks

(sometimes destructive or time-consuming), or prolonged observation to rule out

hidden faults. These steps consume engineer time and test resources and can

cause production downtime, making exhaustive normal labeling economically

impractical at scale. For instance, in automotive quality management, current

practice for windshield-wiper noise relies on expert assessment: after

controlled recordings, mel

frequency cepstral coefficients/spectrogram features are computed,

and an expert labels the noise types [

6].

Early efforts in one-class classification

introduced support vector data description (SVDD) and the one-class support

vector machine (OC-SVM) as core frameworks. SVDD learns a minimum-radius

hypersphere that encloses the normal training data, predicting observations

outside the decision boundary as anomalies [

7].

The OC-SVM learns a maximum-margin separator from the origin in feature space

to capture the support of the normal distribution [

8].

While these models produce compact, interpretable decision boundaries, they

generally require a clean set of normal samples and do not utilize unlabeled

data, thereby limiting their effectiveness when normal labeling is costly and

unlabeled observations are abundant.

Graph-based semi-supervised learning offers a

systematic approach to utilize unlabeled data by representing adjacency and

manifold structure. The basic concepts of spectral graphs and Laplacian

regularization define the cluster assumption through the concept of smoothness

across neighborhoods [

9,

10]. Recent studies

and applications in graph anomaly detection indicate extensive utilization

across nodes, edges, subgraphs, and whole graphs [

11,

12,

13].

SVDD has been extended using semi-supervised methods that utilize the structure

of unlabeled data while employing a small number of labeled normal observations

to guide the boundary. In order to leverage large unlabeled data without hard

pseudo-labels, a common practice is to enhance the SVDD objective with

manifold/graph regularization so that points connected on a similarity graph

remain close in the learned representation [

9,

10].

One SVDD variant, graph-based semi-supervised SVDD (S3SVDD), leverages

global/local geometric structure with limited labels by utilizing a

-nearest neighbor (

-NN) spectral graph and a Laplacian smoothness term

in the SVDD objective to exploit unlabeled data [

14].

Similarly, semi-supervised subclass SVDD proposes a new formulation that

utilizes global/local geometric structure with limited labels [

15]. Separately, a manifold-regularized SVDD for

noisy label detection was introduced, showing that incorporating a graph

Laplacian into the SVDD objective improves robustness to label noise while

still leveraging abundant unlabeled data [

16].

In addition, a semi-supervised convolutional neural network (CNN) with SVDD has

demonstrated practical viability in industrial monitoring [

17]. While traditional graph-based SVDD variants

have shown potential, these methods typically rely on fixed, pseudo-labeled

neighbor graphs (e.g.,

-NN with a chosen metric and

) and uniform edge weights, which can over-connect

across data density breaks, propagate contamination from suspect (anomalous)

neighbors, and require careful tuning [

9,

14,

18,

19,

20].

The introduction of deep learning has led to

significant advances in deep anomaly detection. Deep SVDD (DeepSVDD) extended

the SVDD framework by combining it with a deep encoder that maps data into a

latent representation enclosed by a hypersphere [

21].

Autoencoders and their variants have been widely adopted to learn

low-dimensional embeddings and reconstruction-based anomaly scores in

industrial and time-series contexts [

22,

23].

Additionally, self-supervised anomaly detection has emerged as a promising

direction by utilizing contrastive learning and related pretext objectives that

enhance representation quality under limited labels [

24,

25].

However, common deep anomaly detection methods often use objectives that are

indirectly aligned with the decision boundary (e.g., reconstruction error),

leverage unlabeled data using proxy tasks rather than task-aware constraints in

the decision boundary learner, and offer limited interpretability of decisions [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Motivated by the aforementioned challenges, this

paper presents Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep SVDD (GAR-DSVDD). Specifically,

we develop a semi-supervised Deep SVDD that trains a deep encoder and a

one-class hypersphere end-to-end, while exploiting unlabeled structures with a

center-pull regularizer on a learned graph. To build this graph, we introduce

an attention-weighted latent -NN mechanism that assigns label and score-aware

importance to neighbors, emphasizing prototypical normal observations and

down-weighting suspect or anomalous samples, thereby mitigating label scarcity

and limiting error propagation from contaminated edges. Unlike iterative

pseudo-labeling methods, our training uses unlabeled data directly through the

center-pull and graph smoothness regularizers, which stabilize optimization and

reduce computation. For safety-critical deployment, per-instance attention weights

provide transparent explanations over the top- neighbors. Comprehensive experiments on a

simulated dataset and an industrial windshield-wiper acoustics case study show

that GAR-DSVDD achieves superior detection of subtle anomalies compared with

classical and deep learning benchmarks, while reducing labeling effort and

operator subjectivity.

The remainder of the paper is structured as

follows. Section 2 reviews preliminaries

and notation for semi-supervised anomaly detection. Section 3 presents the proposed GAR-DSVDD

method. Section 4 describes the

experimental setup and reports results on simulated datasets and the

windshield-wiper acoustics case study, along with sensitivity analyses. Section 5 discusses findings, conclusions, and

potential future work directions.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Data and Basic Notation

Given a training dataset

that decomposes into two disjoint subsets: a small

set of labeled normal samples

and a large unlabeled set

, with

Let be the index set of labeled normal observations

and the unlabeled indices, with , , and label rate . The unlabeled pool is assumed predominantly

normal and may contain a small contamination of anomalies, upper-bounded by . Features are standardized by coordinate

(z-scoring). A learnable encoder maps each input to a latent representation, where denotes the encoder’s trainable parameters; we

write and collect latents as . We stack them row-wise in . We use for the Euclidean norm and for the standard inner product in . This setting follows the deep one-class paradigm:

the normal class is to be enclosed within a compact latent region while

avoiding pseudo-labels for the unlabeled pool. Instead, informs the latent geometry via a graph defined

over (details in §3).

Prior work motivating this formulation includes

Deep SVDD–style one-class modeling and graph-based semi-supervised learning

that leverages unlabeled geometry [

9,

10,

21].

2.2. Latent One-Class Score

We summarize the normal set by a latent center

and a soft margin (squared radius) used for score

calibration

Given latents

with

, the per-sample anomaly score is

A sample is more anomalous

as increases; the decision boundary is . Eq. (1) gives the deep “hypersphere” view of SVDD

in latent space, where summarizes the normal set and maps inputs to latents. The offset specifies the boundary tolerance (squared radius)

via a softplus parameterization, ensuring positivity and smooth gradients near

the boundary. The center is typically initialized as the mean of to stabilize early training. The score is

scale-aware: increasing relaxes the boundary, whereas decreasing tightens the enclosure, preserving the

boundary-level interpretation (distance to versus tolerance ). During training, is treated as a calibration constant, so choosing

a train-quantile threshold on f

is equivalent to thresholding the same quantile of .

3. Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep SVDD

We now detail GAR-DSVDD. The objective has three

parts: (i) a one-class enclosure on labeled normal observations, (ii) an

unlabeled neighbor-smoothness on squared distances over an attention-weighted

directed, row-normalized -NN graph, and (iii) standard parameter

regularization.

3.1. Latent Attention-Weighted -NN Graph

We construct a directed row-normalized graph

over the latent set

, where each latent is produced by the encoder

, and we stack them row-wise as

. For each node

, define the directed neighborhood

as the indices of the

-NN of

under a base metric (Euclidean by default). Each

candidate edge

carries a base affinity

, chosen as either a Gaussian kernel or a constant:

To emphasize true normal observations and suppress

suspect connections (possible anomalies), we compute score-aware attention on

each edge. With

heads, the per-head logits are

where

are linear projections (shared across pairs for

head

),

is the attention width,

is a contamination reducing coefficient, and

is the current one-class score (Eq. (1)). We

normalize within

using a temperature

-scaled softmax:

and aggregate heads by averaging

We integrate attention with the base affinity using

and then row-normalize the outgoing weights:

Edges outside

have weight

(

if

). Row-normalization preserves scale across

heterogeneous densities (outgoing weights sum to 1) and reduces error

propagation by down-weighting high-score (potentially anomalous) edges during

training. We compute attention weights without back-propagation and keep them

fixed between graph refreshes. Prior work motivating the attention graphs to

interpret unlabeled data geometry includes [

9,

10,

32].

To keep training tractable, we do not materialize a

full graph at every step. Instead, we rebuild a latent-space -NN index periodically and, for each mini-batch,

form edges as the union of (i) cached neighbors of the batch points and (ii)

within-batch -NN edges—preserving local geometry for the

smoother while keeping computation practical.

3.2. Unlabeled Geometry via Neighbor-Smoothness on Squared Distances

Unlabeled samples help create a smooth decision

boundary by discouraging sharp variations of

along high weight edges of the attention-weighted

graph (described in §3.1):

Penalizing differences of (rather than feature vectors) aligns the boundary

with high-density regions without collapsing representations and preserves the

simple one-class test rule on .

The derivatives of

are

and by the chain rule

so

and

During training, we rebuild the graph periodically

and hold fixed within each interval, so we do not

back-propagate through the weights in this term.

3.3. Labeled-Normal Enclosure

Labeled normal observations

anchor the hypersphere in latent space through a

distance-based objective:

where

,

is a latent center summarizing the normal set. and

weakly centers the hypersphere. This formulation

directly penalizes the squared distance of labeled normal observations from

yielding stable gradients and a simple coupling to

the encoder.

The gradients of

are

Since

, by the chain rule

3.4. Unlabeled Center-Pull

To stabilize training when the labeled normal set is small, we add a label-free pull of the

unlabeled latents toward the center . This acts on raw squared distances and complements the neighbor smoothness. The graph

term equalizes differences of along edges and is largely insensitive to the

global level of ; with few labelled observations this can cause

scale drift and a poorly calibrated score . Moreover, early graphs may include contaminated

edges (unlabeled anomalies can appear inside or near the hypersphere), so

smoothing alone can propagate their influence. The center-pull softly anchors

the mean of for the normal unlabeled pool, reducing drift and

reducing contamination while the graph term aligns local variations.

This imposes a global constraint by shrinking the

mean of over toward . Unlike —which is local and relative— fixes the overall scale and prevents drift when

labels are scarce, improving calibration of .

Since

, by the chain rule

3.5. GAR-DSVDD Objective Function

The total loss combines unlabeled geometry, labeled-normal

enclosure, and unlabeled center pull:

with

,

, and

as in Eqs. (3), (4), and (5), respectively, the

scalars

control the strengths of the graph regularizer and

unlabeled center pull.

Together, , , and play complementary roles: anchors the center using trusted labeled normals, preventing center

drift; enforces local consistency of squared distances on

the attention-weighted, row-normalized -NN graph, transferring structure from the

unlabeled pool without collapsing features; and imposes a global moment constraint on unlabeled

data, fixing the overall scale of and improving calibration of the score .

We train jointly using the AdamW optimizer. The

attention-weighted -NN graph is recomputed every epochs and held fixed within those intervals. No

gradients flow through the attention computation or through . At deployment, a testing observation can be labeled as an anomaly if its score exceeds a train-quantile threshold otherwise it will be considered as normal.

In summary, GAR-DSVDD combines a deep one-class

boundary with graph-based semi-supervision in a way that is both robust and

label-efficient. By regularizing squared distance (scores)—not features—over an

attention-weighted latent -NN graph, it aligns the decision boundary with the

data manifold without collapsing representations and preserves the simple

test-time rule . Score-aware attention selectively down-weights

suspicious neighbors, curbing over-smoothing from contaminated edges and

density breaks. In addition to this, local, edge-wise smoothing of , an unlabeled center-pull imposes a global moment

constraint that stabilizes the overall scale of the distance field, improving

score calibration when labeled normal observations are scarce. Because

unlabeled data enter only through these geometric regularizers (no

pseudo-labels), a small labeled set is enough to anchor the hypersphere while

the unlabeled pool shapes the boundary. Thus, the proposed method effectively

utilizes information from labeled and unlabeled observations for enhanced

anomaly detection in semi-supervised settings.

|

Algorithm: GAR-DSVDD (training) |

|

Inputs: , ; ; graph params ; weights ; refresh period T ; total epochs . |

Outputs: decision threshold .

Initiation: Compute for ; set . Build graph (t = 0): Compute latents for all data; form k-NN; compute multi-head attentions with temperature ; average to ; integrate via μ; row-normalize to obtain . -

For t = 1, …, Tepochs:

a) Forward on mini-batch : , and for attention/monitoring .

b) Loss: .

c) Backpropagation + AdamW updates for .

d) Graph refresh: if : recompute latents; rebuild k-NN, attentions and row normalize

Threshold selection: or via validation. |

Inference (testing)

Given xnew:

Compute latent . Score . Predict anomaly if otherwise normal.

|

(Note: is the attention softmax temperature; is the decision threshold).

4. Experiments

In order to evaluate the performance of the

proposed method, we apply it to a semi-supervised setting over a simulated

dataset to visualize behavior and an industrial case study in the domain of

industrial automotive quality management, where windshield wiper reversal noise

is detected.

4.1. Experimental Setup

Experiments are conducted on a simulated two-dimensional

dataset and a real industrial windshield-wiper acoustics dataset to

compare the proposed GAR-DSVDD against established methods, including DeepSVDD, OCSVM, classical SVDD, and S3SVDD. All deep models share the same encoder

capacity and optimization schedule for fairness. Threshold calibration follows

each method’s policy: for GAR-DSVDD and DeepSVDD, we use a train-quantile rule

at a fixed level over labeled-normal scores, whereas OCSVM, SVDD, and S3SVDD

use their native decision functions. Across both experiments, training follows

a semi-supervised setting: a small subset of labeled normal samples and a large

unlabeled pool that may include a small contamination of anomalies (bounded by ). We construct four disjoint partitions: labeled normal

observations, unlabeled, validation, and a held-out test set.

Performance is evaluated on the held-out test split

using four measures derived from the confusion counts—true positives (TP),

false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN).

Overall accuracy (fraction of correctly classified

instances):

Detection rate (also called recall or true positive

rate), measuring how many anomalies are correctly detected:

The F1 score summarizes the trade-off between

precision and detection rate under class imbalance. Define precision as

then

Balanced accuracy, averaging sensitivity (detection

rate) and specificity (true negative rate). First define specificity

then

For each dataset/seed, we test the directional

alternative : GAR-DSVDD >

benchmark on the F1 score using paired -tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests across seeds

and report their p-values.

4.2. Simulated Data

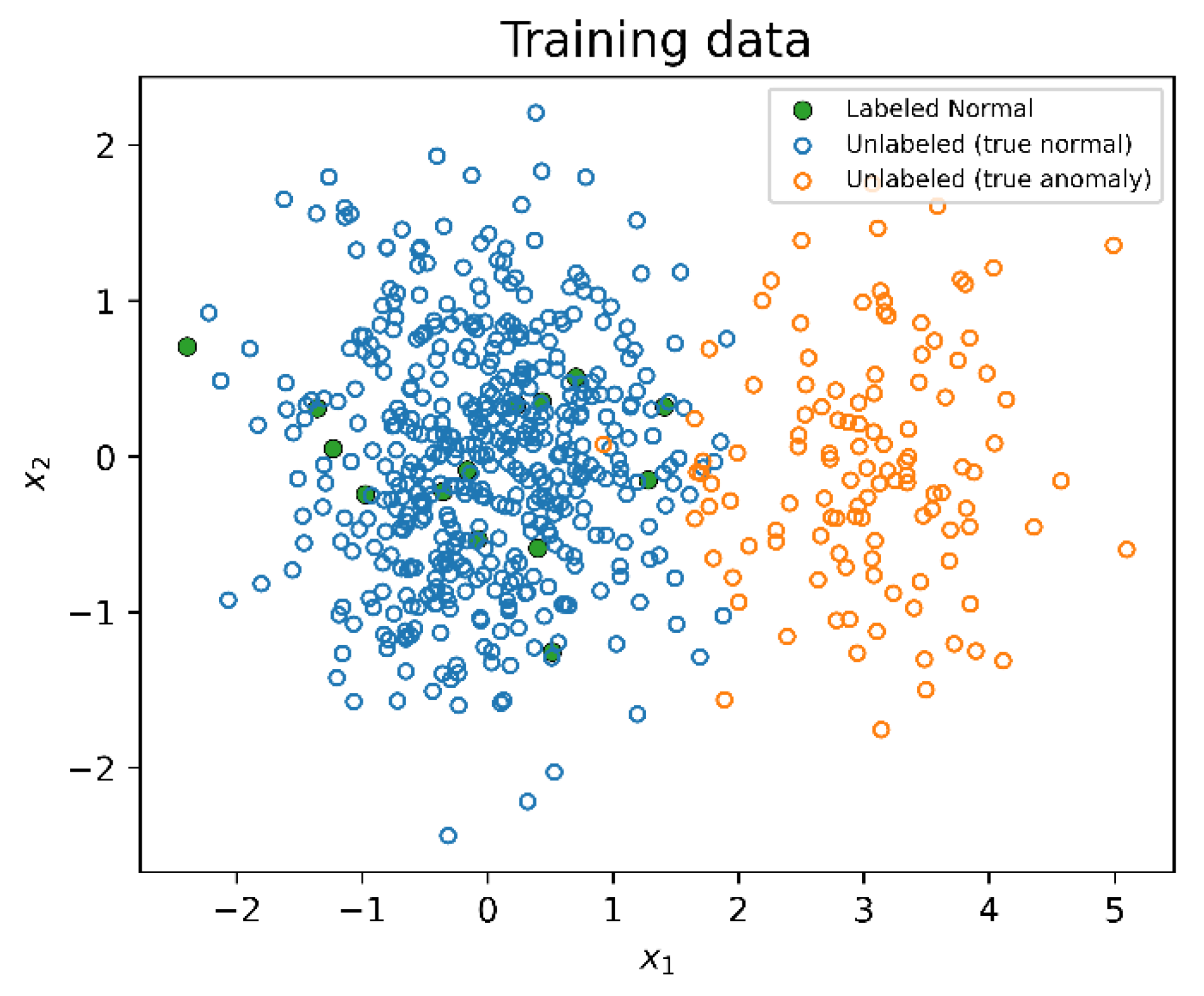

In the simulated study, we utilize a two-cluster,

two-dimensional dataset that has separable centers and evaluate it under a

semi-supervised setting. We draw

normal observations and

anomalies, label a small fraction of normal

observations

, set unlabeled contamination to

, and reserve

for validation and

for testing.

Figure

1 shows the training dataset used for the experiment, where labeled and

unlabeled observations are used to train GAR-DSVDD and S3SVDD, while the other

methods use labeled observations only. We carried out a total of 10

experiments, using different seeds when generating the data. The training set

for one of the experiments is illustrated in

Figure

1.

All deep methods share the same encoder for fairness: a two-layer MLP with hidden widths mapping with ReLU activations. Our method constructs a

latent -NN graph on with and attention weights ( heads, key dimension ). The attention-weighted graph is recomputed every

epochs and held fixed between refreshes; no

gradients flow through the attention computation. We optimize the objective in

Eq. (6) using AdamW for epochs with refresh rate and learning rate , graph regularizer strength , and unlabeled center pull strength . Lastly, we calibrate by setting it to the same train-quantile used for

threshold selection over labeled normals.

As for the remaining methods, DeepSVDD is trained

on labeled normal using the same applicable parameters of the proposed method,

OSCVM uses , SVDD uses radial basis function (RBF) kernel

parameter , and S3SVDD uses RBF kernel parameter with = 9. The deep methods use a train-quantile rule at

, and the native decision function is used for the

rest.

The performance results of the proposed methods

compared to benchmarking methods over all testing performance metrics for an

experiment are shown in

Table 1, whereas

Table 2 compares their F1 score over 10

different testing sets where the data was generated using different seeds.

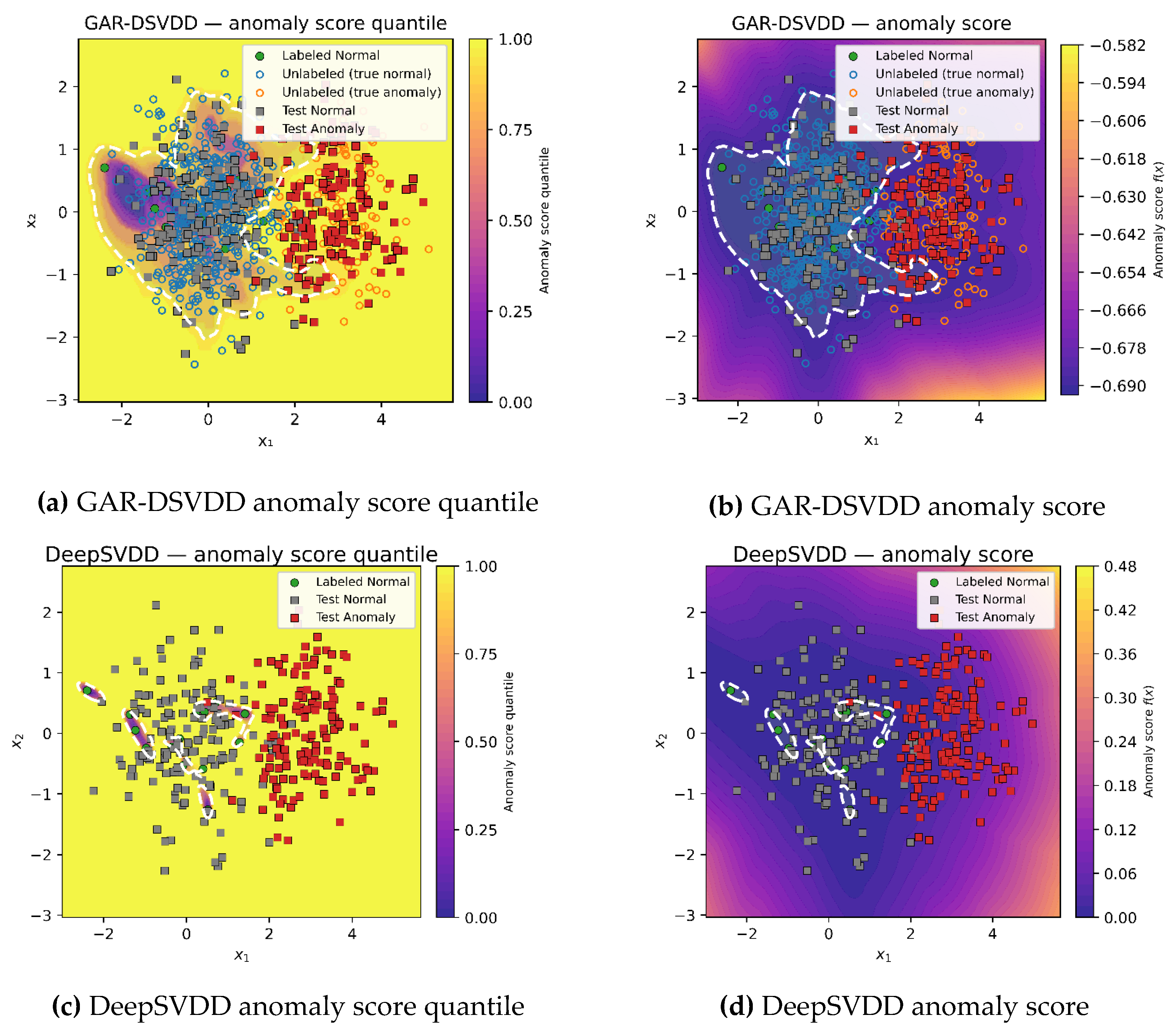

DeepSVDD trains only on labeled normal observations

and learns a tight hypersphere where many normal observations on low-density

areas fall outside it, thus, increasing false positive rate and reducing

overall accuracy, and F1 despite having high detection rate. OCSVM lacks

representation learning and geometry-aware regularization, thus constructing a

narrow decision boundary where detection rate remains high, but specificity and

overall accuracy suffer, leading to a lower F1 score. Since classical SVDD does

not utilize unlabeled-geometry guidance, it builds a decision boundary based on

labeled observation alone, thus, obtaining a tight hypersphere yielding to a

high false positive rate and reduced accuracy and F1 score. Incorporating a

fixed-weight graph S3SVDD shows similar performance to SVDD as fixed-weight

graph cannot truly suppress influence of suspect (anomalous) neighbors, thus,

assumes that most unlabeled observations are anomalous and constructs a narrow

hypersphere.

In contrast, the attention-weighted GAR-DSVDD

achieves the best F1 and balanced accuracy, among all other methods, by pairing

high detection and lower false positives. Attention down weights influence from

suspect neighbors in the unlabeled graph, limiting score dispersal from

contaminated (anomalous) points and keeping the boundary near density valleys.

The center pull regularizer on unlabeled observations prevents over smoothing

decision boundary, preserving overall accuracy, while labeled normal observations

ensure that the hypersphere is anchored to the normal region. Overall,

GAR-DSVDD yields a more robust hypersphere across all experiments.

The obtained anomaly score and its quantiles are

shown in

Figure 2. In the figure, the

quantile contour for the anomaly score is drawn to

indicate the decision boundary for the deep methods, where the native decision

boundary is shown for the shallow methods. Note that DeepSVDD and GAR-DSVDD use

a single hypersphere in latent space as its decision region based on the

learned quantile. In the figure, after the encoder’s nonlinear mapping back to

input space, this can look complex or even disconnected, despite being one

sphere in the learned latent space.

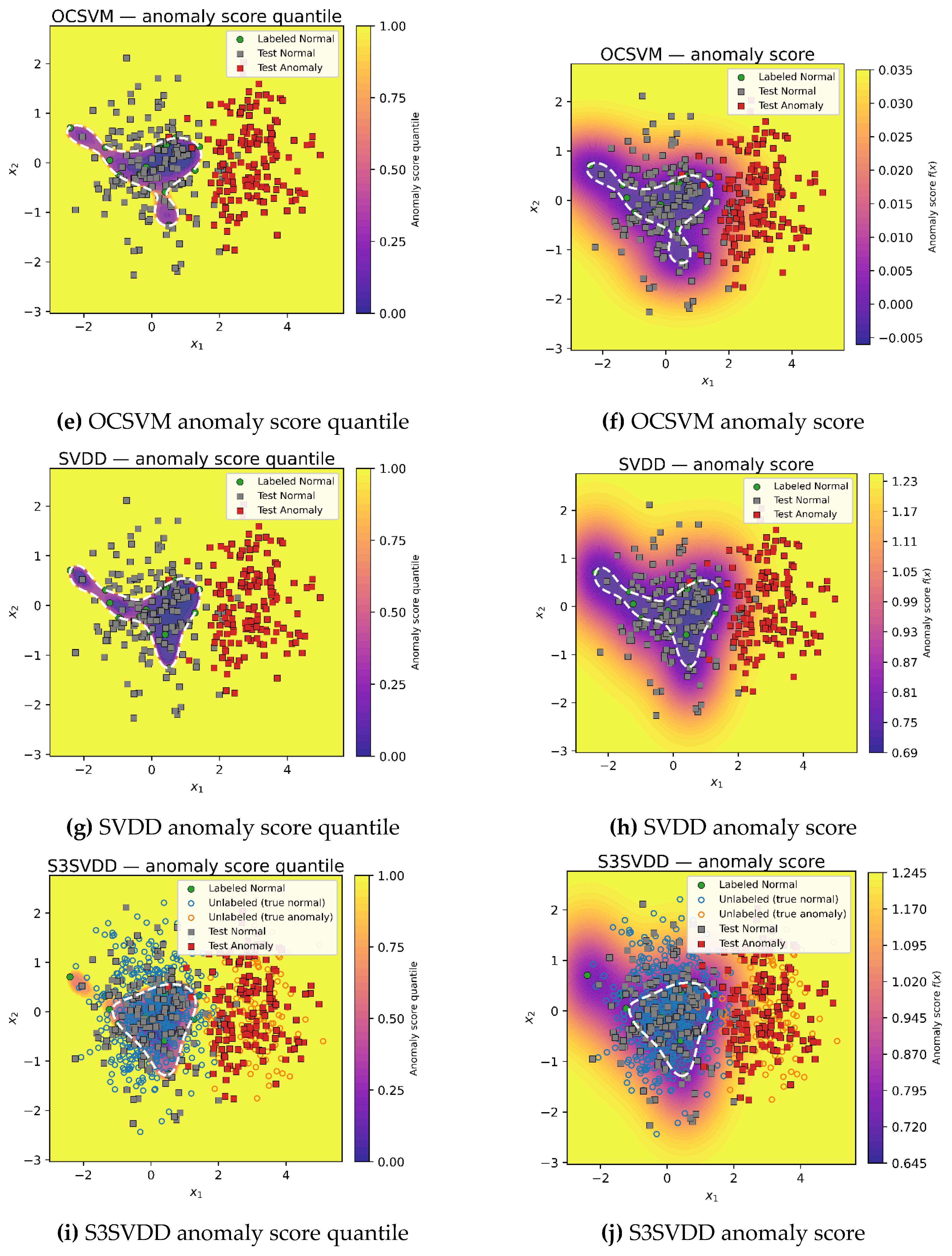

4.3. Case Study: Windshield-Wiper Acoustics

This section presents our case study on windshield

wiper acoustics. We analyzed windshield-wiper sound recordings gathered under

tightly controlled laboratory conditions. Each sample was captured from

production wiper assemblies inside an anechoic chamber while a sprinkler system

supplied water to replicate rainfall. To eliminate confounding noise sources,

the vehicle’s engine remained off, and the wiper motor was powered by an

external supply. A fixed in-cabin microphone recorded the acoustic pressure signal,

which was calibrated and expressed in decibels at a constant sampling rate.

Domain specialists reviewed the recordings and assigned ground-truth labels

covering reversal noise fault phenomena alongside normal operation. The dataset

consists of a total of 120 windshield wiper recordings, where 61 recordings are

for normal operations and 59 for faulty (anomalous) operations. These expert

annotations are treated as ground truth for evaluation.

Each observation is a single full recording

summarized as a fixed-length vector from recording descriptors, in line with

recent acoustic research for sound analysis. We compute 32 MFCCs to capture the

spectral envelope on a perceptual scale, together with first- and second-order

deltas to encode short-term dynamics; these cepstral families remain standard

and effective in contemporary studies. We also include a 12-bin chroma profile

to reflect tonal/resonant structure and simple spectral/temporal statistics—spectral

centroid, spectral bandwidth, spectral roll-off at 95%, root-mean-square (RMS)

energy, and zero-crossing rate (ZCR)—which are routinely used and compared in

modern journal work. For every multi-frame descriptor with

coefficients, we pool across time by concatenating

the per-coefficient mean and standard deviation, so each such descriptor

contributes

values; scalar descriptors contribute two values

(mean and standard deviation). Summing up all parts yields a

dimensional vector per recording of means and

standard deviations across time that we use for the reversal-noise dataset.

These choices (MFCCs with deltas, chroma, and spectral statistics with mean/std

pooling) align with recent papers documenting their efficacy and definitions

across environmental-sound, speech-emotion, smart-audio, and urban-acoustic

applications [

33,

34,

35].

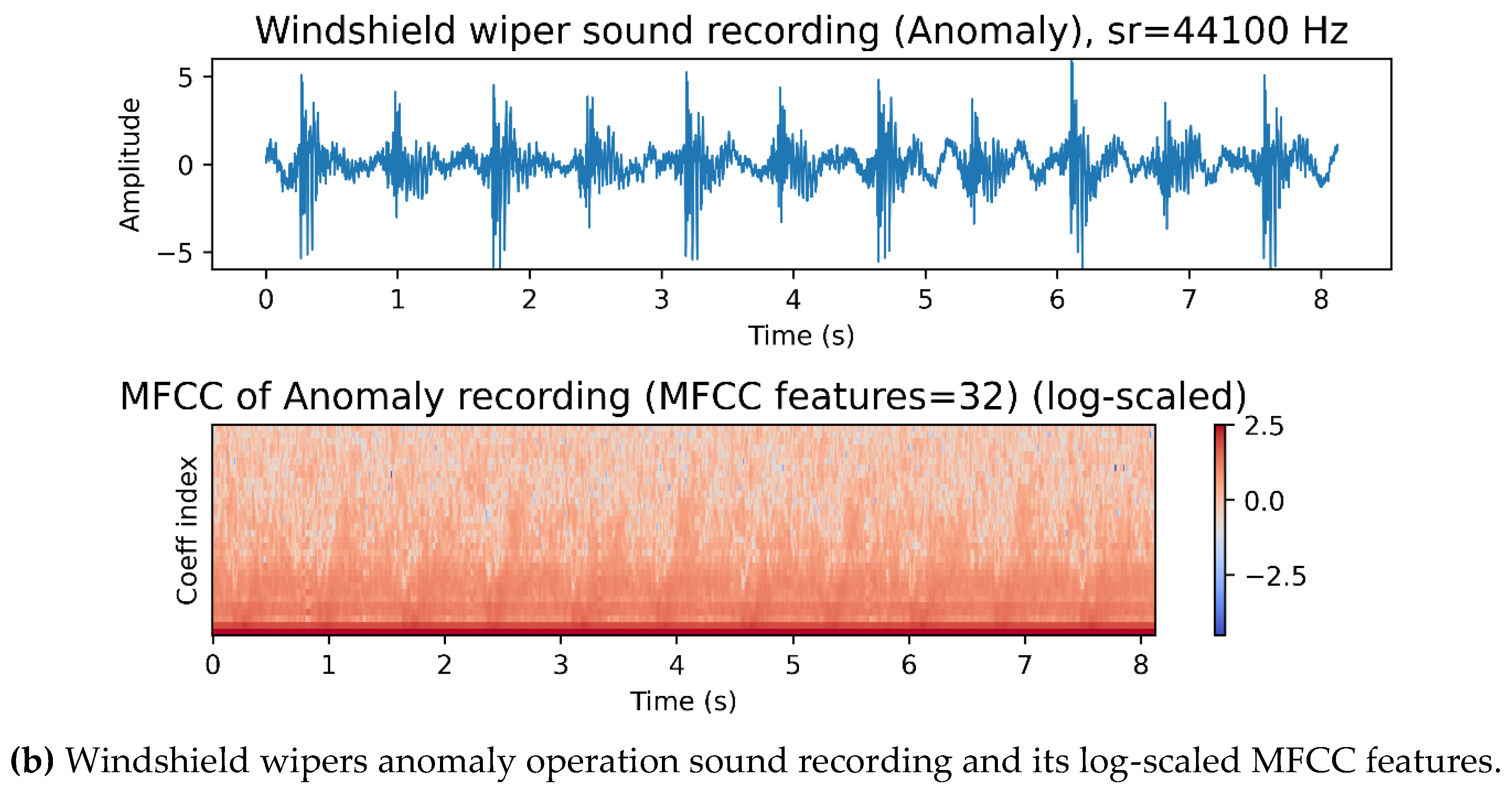

Figure 3 shows normal and anomaly operation

recordings of windshield wipers with their corresponding MFCC features on the

log scale.

Table 3 summarizes the feature

extraction methods used for acoustic analysis of the windshield wiper sound

recordings.

We follow the same semi-supervised protocol as in the simulated study: a small subset of labeled-normal clips is provided, and a large unlabeled pool may include mild anomaly contamination; the remainder is split into validation (for hyperparameter selection) and a held-out test set. Concretely, we use a 60/20/20 split for train/validation/test. Within the training portion, we label 10% of the normal observations () and place the rest into the unlabeled set with anomaly contamination ratio . All deep methods use the shared encoder : a two-layer MLP with ReLU activations. For our method, GAR-DSVDD, we build a latent -NN graph with and multi-head attention (8 heads, key dimension 32) over the encoder representations. The attention-weighted graph is recomputed every epochs and held fixed between refreshes; no gradients flow through the attention computation. The objective in Eq. (6) for 120 epochs using AdamW (learning rate ), graph regularizer strength , and unlabeled center pull strength . is calibrated by setting it to the same train-quantile used for threshold selection over labeled normals.

Benchmarks are configured to match their best settings from the wiper runs: DeepSVDD is trained on labeled normal observations with the same encoder/optimizer, soft-boundary objective regularizer value ; OCSVM uses with an RBF kernel ; SVDD uses an RBF kernel with ; and S3SVDD employs a NN graph with and RBF . The deep methods apply a train-quantile rule with , while OCSVM, SVDD, and S3SVDD use their native decision function.

The performance of GAR-DSVDD and the existing methods overall performance metrics are presented in

Table 4.

Table 5 shows the F1 score over 10 different testing sets that were prepared using 10 different seeds for statistical validation.

Due to the extreme challenges represented by this dataset and the semi-supervised experiment settings with very few training labeled normal observation, all benchmarking methods perform poorly for anomaly detecting as they fail to utilize unlabeled observations in constructing their decision boundaries as indicated by the F1 and accuracy metrics. The decision boundary obtained by these methods tend to be very narrow, causing most testing observations to be detected as anomalies while increasing the false positive rates, as seen by the specificity metric for these methods.

In contrast, GAR-DSVDD maintains perfect detection while achieving a higher specificity by leveraging an attention-weighted latent -NN graph that weakens edges in mixed or uncertain neighborhoods, thus, effectively utilizing information from unlabeled observation. This reduces the graph-driven propagation of elevated scores into nearby normal observations, keeps the decision boundary aligned with low-density regions, and prevents the false positive rates that undermine the other methods. Furthermore, the learned neighbor attention weights serve as per-instance attributes, indicating which historical normal observations most influence a observation’s score. In an industrial setting, these attributions can streamline expert review and reduce the volume of fully verified normal labels required over time, aligning the method with label-efficiency needs in automotive quality control.

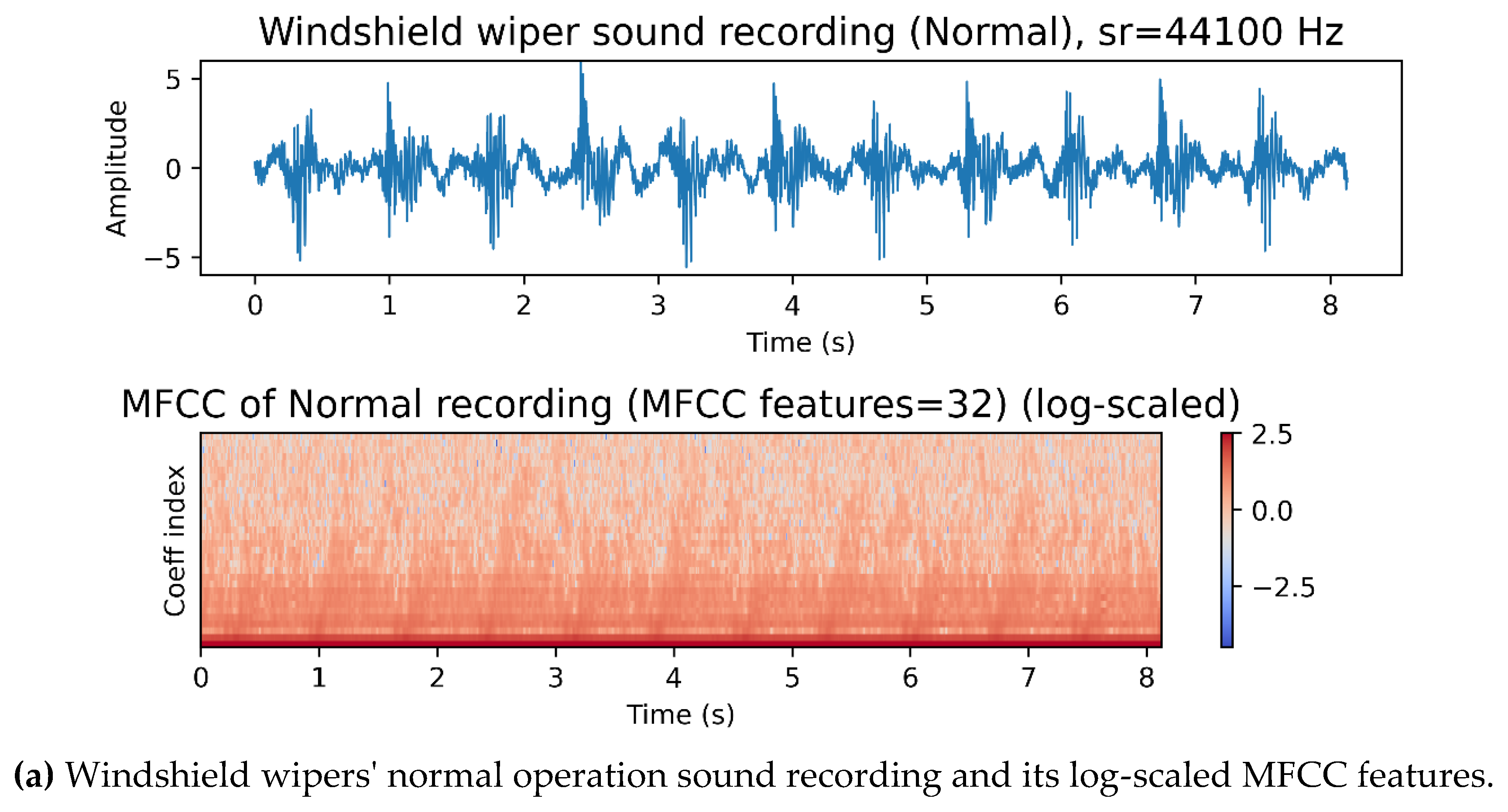

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

In this section, we perform sensitivity analysis over the simulated data. In

Table 6 and

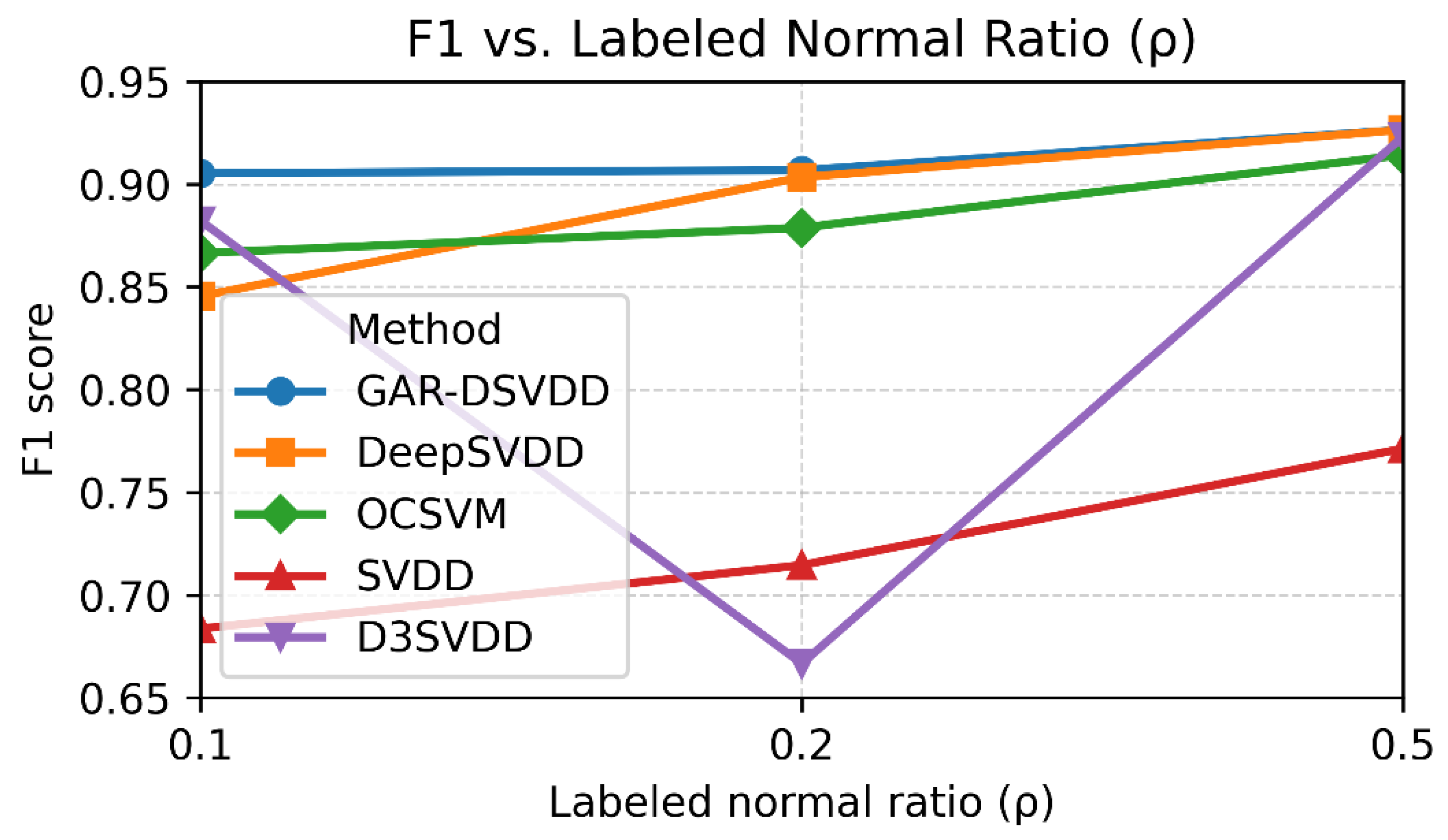

Figure 4 we show the effect of increasing the normal labeled observations ratio

over the F1 performance of the methods. Across labeled-normal ratios

, the results show a clear label-efficiency advantage for our semi-supervised GAR-DSVDD in the low-label setting, with supervised baselines gradually converging as ρ increases. With scarce labels, GAR-DSVDD leads, consistent with its attention-weighted graph regularization that leverages unlabeled structure while mitigating contamination. As the label budget grows to a moderate level, GAR-DSVDD remains best, but the gap narrows, particularly with DeepSVDD, which benefits directly from richer labeled evidence. OCSVM improves steadily with more labels yet trails the deep methods, while classical SVDD consistently lags despite incremental gains. S3SVDD exhibits non-monotonic behavior, sensitive to label density and split composition, but becomes more competitive with increased labeling ratio. In summary, when only a small portion of data can be labeled, our target operating point, GAR-DSVDD outperforms all alternatives; as labeling increases, purely supervised approaches like DeepSVDD catch up and have similar performance, whereas OCSVM and SVDD continue to benefit but remain behind, and S3SVDD’s competitiveness depends on the labeling setting.

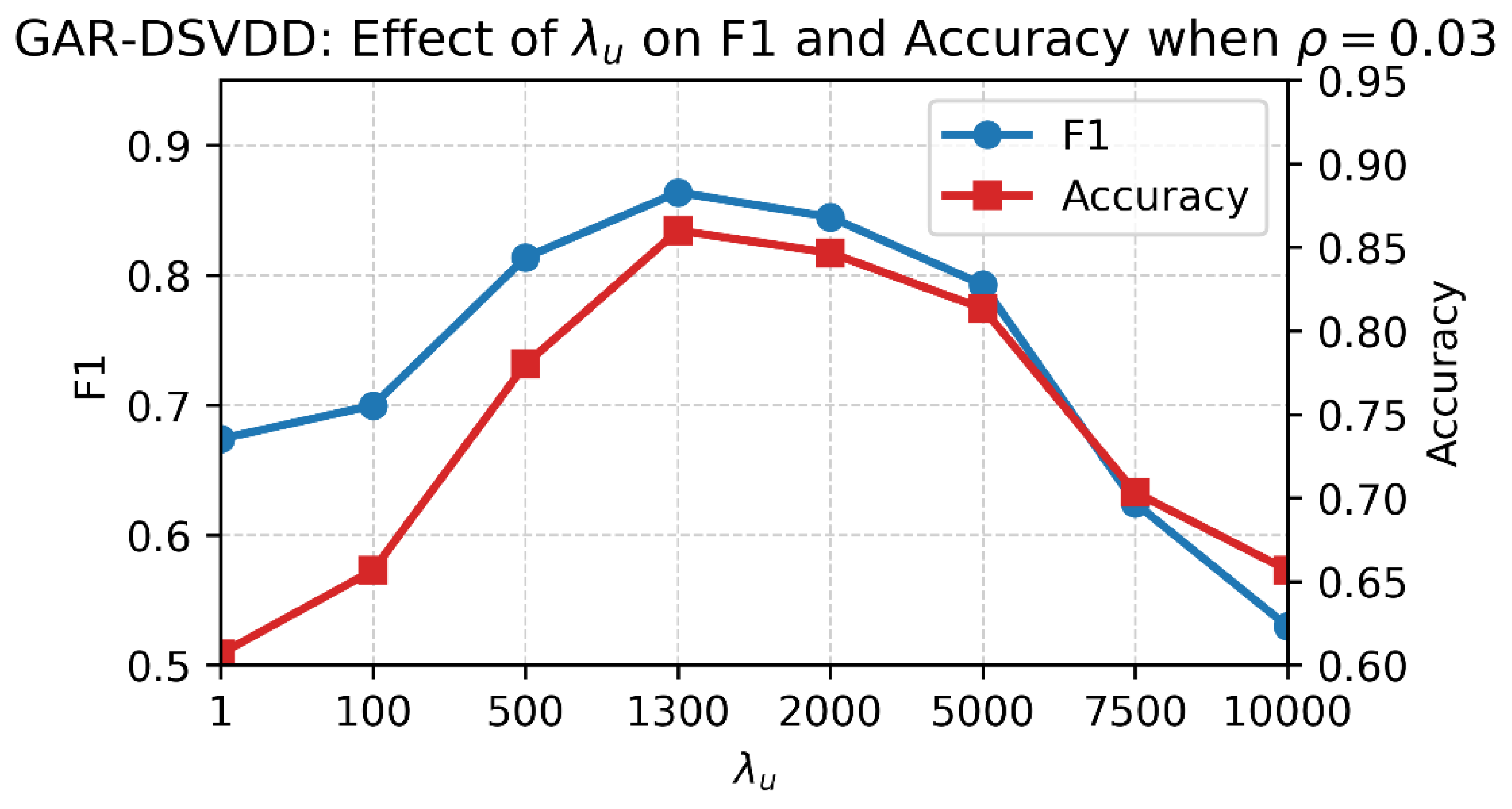

Moreover, by setting

, we analyze the effect of

on F1 and accuracy of GAR-DSVDD, as illustrated in

Figure 5. For small

, less importance is given to unlabeled geometry, thus, the unlabeled information is underutilized, leading to narrow decision boundary and underperforming results. Increasing

gives more importance to the graph-loss term (unlabeled geometry), which expands the decision boundary with consistent gains in performance. The performance is highest near

1300, where the boundary best balances the influence of labeled data information, unlabeled geometry, and central-pull term on unlabeled observations. At higher

values, excessive emphasis on unlabeled geometry over-smooths the graph structure, widening the decision boundary and allowing anomalous unlabeled observations to be included within the decision boundary, thereby degrading performance. These findings indicate that

should be carefully selected via validation to allow an optimal construction of the decision boundary that keeps anomalous unlabeled observations outside and expands enough to keep normal behavior observations inside.

5. Conclusions

Identifying anomalies is a critical issue in applications such as manufacturing, industrial process control, cybersecurity, disaster management, and medical diagnosis, as they provide information about deviations from normal behaviour in critical environments [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Among available approaches, SVDD-based procedures remain attractive for their compact decision boundaries and test-time simplicity.

In this paper, we presented a GAR-DSVDD for semi-supervised anomaly detection. The method encloses labeled normal observations with a deep one-class boundary while propagating score-level smoothness over an attention-weighted latent -NN graph to leverage abundant unlabeled data. The attention mechanism reduces over-smoothing from questionable neighbors and respects local density breaks, improving specificity without sacrificing detection. Experiments on simulated data and a windshield-wiper acoustics case study demonstrate that GAR-DSVDD outperforms classical and deep baselines under scarce labels significantly.

Considering future work, many industrial datasets contain multiple normal classes (e.g., distinct operating conditions or product variants). Our current formulation targets a single normal class; extending it to multi-normal settings is a natural next step. One direction is to learn several hyperspheres using a shared encoder, where each hypersphere retains its corresponding normal class while discouraging overlapping with others; the graph attention can be made class-aware to limit cross-class leakage. Finally, online updates with periodic graph refresh and automatic selection of graph/attention hyperparameters would enhance robustness in evolving production environments.

Data Availability Statement

The industrial windshield wiper acoustic data presented in this study are available on reasonable requests from the corresponding author due to confidentiality. The code for the simulated dataset can be found at

https://github.com/alhinditaha/GAR-DSVDD.

Acknowledgments

The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

GenAI Usage Disclosure

No generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) technology was used for generating text, data or graphics, study design, or data collection, analysis or interpretation. GenAI tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI: GPT5) were solely used, under the authors’ supervision, to enhance readability and refine language (grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting). The paper has been carefully reviewed by the authors to ensure its accuracy and coherence.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AdamW |

Adaptive Moment Estimation with (decoupled) Weight decay |

| DeepSVDD |

Deep Support Vector Data Description |

| GAR-DSVDD |

Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep Support Vector Data Description |

|

-NN |

k-Nearest Neighbors |

| MFCC |

Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients |

| OCSVM |

One-Class Support Vector Machine |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| S3SVDD |

Graph-based Semi-Supervised Support Vector Data Description |

| SVDD |

Support Vector Data Description |

References

- Li, H.; Boulanger, P. A survey of heart anomaly detection using ambulatory Electrocardiogram (ECG). Sensors 2020, 20, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, T.J.; Alturkistani, O.; Baek, J.; Jeong, M.K. Multi-class support vector data description with dynamic time warping kernel for monitoring fires in diverse non-fire environments. IEEE Sensors Journal 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakong, W.; Kim, W. An adaptive policy-based anomaly object control system for enhanced cybersecurity. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 55281–55291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsaz, A. A modified convolutional neural network architecture for diabetic retinopathy screening using SVDD. Applied Soft Computing 2022, 125, 109102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Yin, H.; Lin, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, D. A relevant variable selection and SVDD-based fault detection method for process monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2022, 20, 2855–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, T.J.; Baek, J.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Jeong, M.K. Orthogonal binary singular value decomposition method for automated windshield wiper fault detection. International Journal of Production Research 2024, 62, 3383–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax, D.M.; Duin, R.P. Support vector data description. Machine learning 2004, 54, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Platt, J.C.; Shawe-Taylor, J.; Smola, A.J.; Williamson, R.C. Estimating the support of a high-dimensional distribution. Neural computation 2001, 13, 1443–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ghahramani, Z.; Lafferty, J.D. Semi-supervised learning using gaussian fields and harmonic functions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-03); 2003; pp. 912–919. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P.; Sindhwani, V. Manifold regularization: A geometric framework for learning from labeled and unlabeled examples. Journal of machine learning research 2006, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Xue, S.; Peng, H.; Zhou, C.; Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Sheng, Q.Z. Deep graph level anomaly detection with contrastive learning. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 19867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, J.; Xue, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, C.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Xiong, H.; Akoglu, L. A comprehensive survey on graph anomaly detection with deep learning. IEEE transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2021, 35, 12012–12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Tong, H.; An, B.; King, I.; Aggarwal, C.; Pang, G. Deep graph anomaly detection: A survey and new perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, P.; Nguyen, V.; Dinh, M.; Le, T.; Tran, D.; Ma, W. Graph-based semi-supervised support vector data description for novelty detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mygdalis, V.; Iosifidis, A.; Tefas, A.; Pitas, I. Semi-supervised subclass support vector data description for image and video classification. Neurocomputing 2018, 278, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, S.; Bai, Y. The manifold regularized SVDD for noisy label detection. Information Sciences 2023, 619, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Liu, C.; Desmet, W.; Gryllias, K. Semi-supervised CNN-based SVDD anomaly detection for condition monitoring of wind turbines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering; 2022; p. V001T001A019. [Google Scholar]

- Von Luxburg, U. A tutorial on spectral clustering. Statistics and computing 2007, 17, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelnik-Manor, L.; Perona, P. Self-tuning spectral clustering. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2004, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. A survey of large-scale graph-based semi-supervised classification algorithms. International Journal of Cognitive Computing in Engineering 2022, 3, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, L.; Vandermeulen, R.; Goernitz, N.; Deecke, L.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Binder, A.; Müller, E.; Kloft, M. Deep one-class classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2018; pp. 4393–4402. [Google Scholar]

- Pota, M.; De Pietro, G.; Esposito, M. Real-time anomaly detection on time series of industrial furnaces: A comparison of autoencoder architectures. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 124, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neloy, A.A.; Turgeon, M. A comprehensive study of auto-encoders for anomaly detection: Efficiency and trade-offs. Machine Learning with Applications 2024, 17, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, J.; Mo, S.; Jeong, J.; Shin, J. Csi: Novelty detection via contrastive learning on distributionally shifted instances. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 11839–11852. [Google Scholar]

- Hojjati, H.; Ho, T.K.K.; Armanfard, N. Self-supervised anomaly detection in computer vision and beyond: A survey and outlook. Neural Networks 2024, 172, 106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalapathy, R.; Chawla, S. Deep learning for anomaly detection: A survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.03407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; Shen, C.; Cao, L.; Hengel, A.V.D. Deep learning for anomaly detection: A review. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, L.; Kauffmann, J.R.; Vandermeulen, R.A.; Montavon, G.; Samek, W.; Kloft, M.; Dietterich, T.G.; Müller, K.-R. A unifying review of deep and shallow anomaly detection. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 109, 756–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Van Leeuwen, M. A survey on explainable anomaly detection. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 2023, 18, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, R.; Heskes, T. Autoencoders for Anomaly Detection are Unreliable. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Bu, F.; Kang, S.; Kim, K.; Yoo, J.; Shin, K. Rethinking reconstruction-based graph-level anomaly detection: limitations and a simple remedy. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 95931–95962. [Google Scholar]

- Velickovic, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. Stat 2017, 1050, 10–48550. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, A.; Garg, N.K. Environmental Sound Classification: A descriptive review of the literature. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2022, 16, 200115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanian, S.; Chen, T.; Adeleye, O.; Templeton, J.M.; Poellabauer, C.; Parry, D.; Schneider, S.L. Speech emotion recognition using machine learning—A systematic review. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2023, 20, 200266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannem, K.R.; Mengiste, E.; Hasan, S.; de Soto, B.G.; Sacks, R. Smart audio signal classification for tracking of construction tasks. Automation in Construction 2024, 165, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).