1. Introduction

Automated manufacturing environments have almost completely replaced manual assembly lines in all areas of the industrial ecosystem, from machinery and vehicle manufacturing to the chemical and energy sectors. This transition extends to other sectors including food, textiles, and various other manufacturing industries. For this reason, productivity has increased drastically, thus improving the added value of these sectors and generating wealth and progress. However, the number of accidents with damage to human life and/or economic losses in the industrial sector is among the highest among all sectors of economic activity (see [

1,

2] with data from the industrial sector in the United States and the European Union). The potential social and economic impact of this unsafe conditions is very high. For example, in 2024, the industrial sector in the European Union represented a 19% share of the total gross value added [

3], whereas in the United States the manufacturing industry represented a 10% of the total gross domestic product [

4]. These data can easily be extrapolated to the world economy if it is taken into account that the United States and the European Union represent 26% and 14% of the world economy, respectively.

A significant percentage of accidents occur within automated manufacturing lines. These lines are characterized by complex high-speed interactions of different heavy industrial elements. Therefore, the consequences of accidents are potentially serious, both from a human and material perspective. Currently, all new machines operating on European territory must comply with functional safety standards that guarantee the safe and correct operation of their components, so it is required to comply with the essential health and safety requirements (EHSRs) of the Machinery Directive 2006/42/EC. To that end, safety is designed according to a series of standards harmonized with the previous directive, mainly ISO 13849-1 [

5] (safety of mechanical, hydraulic and pneumatic products) and IEC 62061 [

6] (safety of electrical, electronic or programmable electronic systems and products). An equivalent regulatory framework exists in the United States, where machinery safety is governed by Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations (29 CFR 1910) and the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) B11 series of standards, defining the requirements for machine safeguarding and risk reduction. However, in many cases, these measures have limited effectiveness as they can be easily overridden/avoided by operators with insufficient training and subject to careless operation. The most relevant consequence is that an operator can remain inside the safety perimeter of the assembly line when the production cycle starts. This invasion, whether partial or total, involves the creation of an illegitimate (unsafe) scenario with potentially fatal consequences for people’s lives. There is another group of consequences derived from the possible reconfiguration of the scenario by changing the position of some components or including new objects. These are also illegitimate scenarios that may affect the reliability and integrity of the industrial process, with potentially very relevant economic consequences. Every illegitimate scenario should be identified in a robust way, although current safety measures do not cover it. To overcome this, we propose designing a deep learning (DL)-based parallel safety system capable of detecting the aforementioned situations and enhancing traditional safety measures already existing in the manufacturing cells. The logical interaction between traditional safety devices (e.g., doors, light curtains, emergency stops) and the proposed system can be seen in

Figure 1. When the safety signal is broken in any of the classic devices, the machine will enter into a safe state. Additionally, when the safety circuit is closed, the AI system can interrupt it when detecting illegitimate scenarios that have bypassed standard safety measures. The proposed system is consistent with the ISO 12100:2010, which defines the general principles for machinery design, risk assesment, and risk reduction. This standard specifies that complementary protective measures involving additional equipment may have to be implemented when there’s still remaining risk for persons. In this context, the proposed artificial intelligence (AI)-based parallel monitoring system can be regarded as an additional protective measure: it operates independently of the certified functional safety chain and provides early detection of illegitimate scenarios such as human presence or foreign objects inside manufacturing cells.

In this work, we have developed a supervised DL methodology based on contrastive learning (CL) that is capable of synthesizing the information that characterizes the normal operation state of an industrial facility and discriminating, with absolute certainty, the presence of workers within it. By modeling the latent space distribution of the safe scenarios by means of Bayesian clustering, and without performing any additional fine-tuning, the system is also able of detecting potentially unsafe scenarios caused by the presence of anomalous objects that were not seen during the learning process. As a result, through uncertainty quantification, the proposed AI safety system is able to detect any type of unexpected situation that may happen during the production phase of the cell. In order to assess the model’s performance in uncertain situations and provide explainability for its decisions, a patch-based input feature ablations method is proposed. The interpretability analysis reveals the absence of bias and the use of relevant information in the decision-making process. Both the industrial line used in the experimentation and all the data come from real sources, that is, a production environment currently operational in a factory. All of the above constitutes a framework that demonstrates the reliability and robustness of our proposal to ensure detection of unsafe situations. In addition, the presented methodology can be easily deployed in any industrial cell, complementing the safety measures specified by the functional safety standards. The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the main lines of research on the application of AI in architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) environments, with an emphasis on risk detection and safety-related works.

Section 3 describes the industrial configuration, the dataset used, the models and the characteristics of the training carried out.

Section 4 describes the experimental results.

Section 5 describes the Bayesian analysis for the identification of unknown non-legitimate scenarios.

Section 6 presents the designed patch-based input feature ablations method and shows explainability analysis.

Section 7 details the industrial configuration that has resulted in the integration of the AI safety channel into a real manufacturing cell and presents the main limitations encountered in the study, as well as future lines of work. Finally,

Section 8 describes the conclusions of our work.

2. Related Work

One of the main application areas of intelligent manufacturing is the control and monitoring of the production cycle. This monitoring can be addressed from several different perspectives, ranging from an intelligent control of the manufactured products (see [

7,

8,

9] for practical applications) to improving production reliability and ensuring health and safety conditions in manufacturing environments (see [

10]). With this focus in mind, the technological evolution brought by AI has enabled multiple applications in the field of safety and risk management on manufacturing lines. Most of the recent publications refer to the identification of risk scenarios and the detection of the use of appropriate equipment by operators. A line of work with multiple contributions is the use of DL-based on convolutional analysis to detect the appropriate use of safety wearing, mostly helmets but also other equipment [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Another relevant line of research is the detection of safety risks by analyzing scenarios using DL technology and generating a risk classification to prevent accidents [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. [

22] designs a real-time safety alerting system using bluetooth low energy devices for indoor localization and alerting in construction sites. Another active line of research with growing interest in AEC environments is worker ergonomics. [

23] introduces a pipeline based on a three-dimensional (3D) pose estimator and mesh classifier for pose safety assessment and avoiding harmful positions for operators in industrial manufacturing environments. [

24] proposes the study of the posture of the lower limbs of construction workers using the VideoPose3D model to extract spatial coordinates and support vector machines for classification. In [

25] authors design a semi-supervised method to extract workers’ skeletons and estimate the positions and angles of their joints. Based on the results, corrective actions are calculated and a collaborative robot is programmed to help operators perform the most critical operations. These and other works [

26] have been developed primarily in construction and industrial environments and are oriented towards the detection of known scenarios trained in a supervised way.

Anomaly detection is a major research niche of considerable industrial relevance. One prominent domain where it has been extensively applied is predictive maintenance. [

27] presents a hybrid anomaly detection model based on DL that predicts downtime within the manufacturing process by analyzing raw equipment data. [

28] proposes a deep echo state network (DeepESN)-based method for predicting the occurrence of machine failure by analyzing energy consumption datasets from production lines. Another subfield that has attracted growing attention from the research community is the detection of anomalies in manufactured products. [

29] introduces ReConPatch, a CL-based framework that extracts easily separable features by training a simple linear transformation, rather than training the entire network. [

30] proposes a CL scheme based on two stages. First, a discriminator learns to locate anomalies approximately in the input images. Subsequently, this discriminator is used to train a CL scheme by providing negative-guided information. Another prominent research direction focuses on safeguarding critical control infrastructure and information systems. [

31] reviews the potential impact of applying a wide range of DL techniques to study anomaly detection within industrial control systems (ICS) environments. [

32] proposes a CL scheme with data augmentation through negative sampling for anomaly detection in actual operating systems in corporate environments. However, none of these research directions specifically address the visual safety and adequacy control of industrial production processes. The increasing industry automation and the shift towards a dynamic and collaborative manufacturing paradigm also means that production line safety systems must evolve accordingly and support new production models. [

33] details the service groups which are needed for the technical implementation of reconfigurable safety systems (RSSs), derived from the design requirements of reconfigurable manufacturing systems (RMSs). Along the same line, [

34] presents a framework that assists a safety engineer in dynamically redesigning safety measures for an industrial facility based on the available safety devices. The advances in automation and smart manufacturing enabled by AI must also extend to industrial safety. For example, [

35] proposes the use of a YOLO V8-based scheme to monitor in real-time a stamping press process, detect potential dangers, and reduce the number of accidents. Our study, although framed in a similar context, is more ambitious, since it also aims to detect potentially dangerous anomalous situations caused by foreign objects of any kind and therefore could not have been previously learned by the DL models during the training process.

Due to the nature of AI technologies, applying functional safety certification frameworks remains challenging. [

36] reviews why the general DL-based systems development process clashes head-on with traditional safety development pipeline and proposes an integration architecture between DL systems and traditional safety devices that extends widely adopted functional safety management (FSM) methodologies. This perspective enables the integration of AI techniques, such as those developed in this work, as complementary channels that enhance the capabilities offered by traditional functional safety designs. Furthermore, as detailed in [

33], an RSS must have characteristics such as modularity, integrability, and comprehensibility, among others. The AI system proposed in this study fulfills these characteristics. In terms of modularity, the new safety channel offered by the AI operates independently from the functional safety ones, complementing them without affecting their operation. In terms of integrability, the AI-managed channel can be incorporated into a safety system designed using functional safety standards as described in [

7]. Finally, regarding comprehensibility, the proposed AI system offers interpretability measures that enhances transparency and clarity to the inference process performed by the AI, improving the understanding, safe-state recovery, and maintenance of the system.

3. Methods

3.1. Industrial Configuration

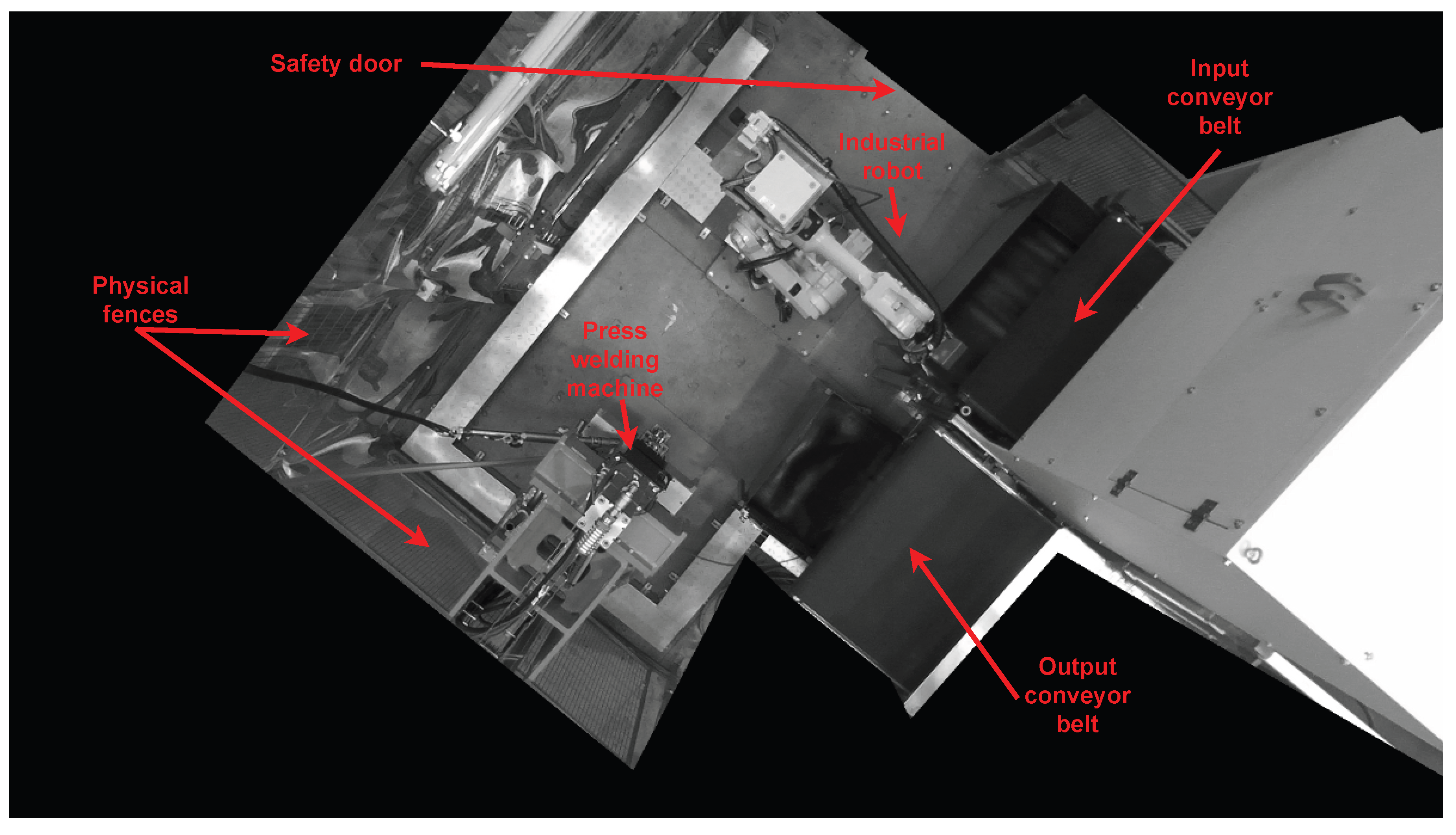

The physical environment from which we obtain the data used in this work can be seen in

Figure 2. It is made up of several manufacturing cells, located in parallel, which perform a press welding process (

Figure 2a). The parts to be welded are picked up and placed on two different conveyor belts. Physical fences and safety door are the only functional safety elements that protect each of the cells (blue fences in

Figure 2b). However, this measure does not guarantee that any foreign object could remain inside the closed perimeter at the moment of starting the production cycle. This may cause serious damage to the installation equipment or, in the worst case, to an employee of the factory. To overcome this, integrating an intelligent monitoring system capable of detecting unsafe scenarios would be a step forward in terms of safety and reliability of the facility.

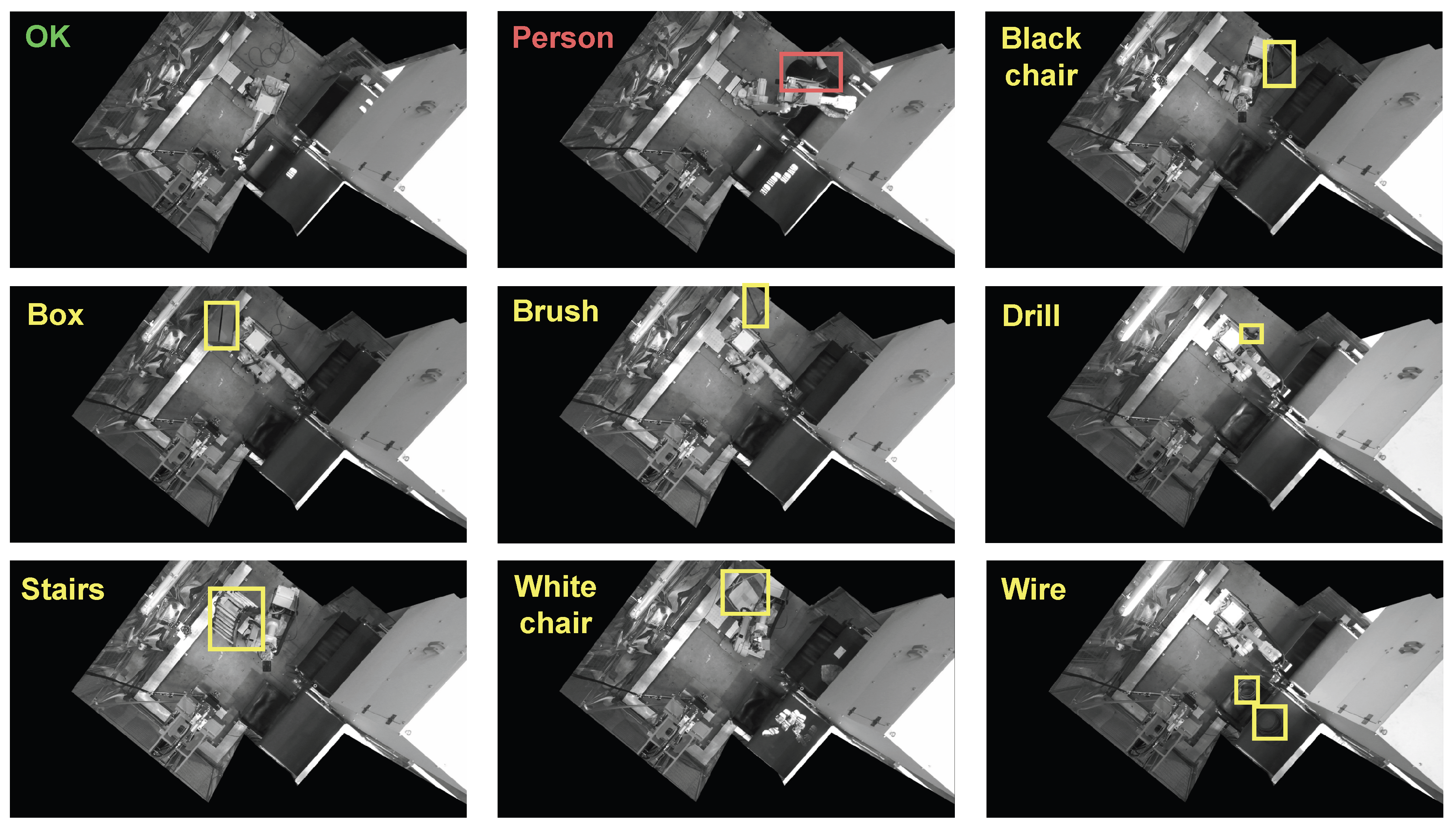

A data capture infrastructure is placed in each individual cell. We use an RGB-D stereo camera with a resolution of 2 megapixels (1920 x 1080) delivered at 30 frames per second. To cover the entire working area within the device’s field of view, the camera is placed in a top-down position. By so doing, each pixel covers, approximately, a 4x4 mm region of the cell’s inner surface. Depth information is discarded since it is very noisy, which would hinder an accurate and robust analysis. Additionally, RGB images are converted to grayscale. This transformation is performed to emphasize the structural characteristics of the image and to increase robustness against illumination changes. Since the images provided by the camera cover more area than the required, a binary mask is constructed to indicate the region to be inspected. By doing this, the inspection perimeter is limited and the possible noise outside the cell that potentially might have a bad influence on the DL methodology is filtered out. An example of the inspection area captured by the camera, after applying the masking, can be seen in

Figure 3. This simple data acquisition method can be easily adapted to the topology of the cell to be inspected, ensuring simple and robust scalability.

3.2. Dataset

When building the dataset representing the safe operation of the facility, it is important to guarantee that the manufacturing cell always remains in legitimate scenarios (safe states). These scenarios are very diverse because the cell has multiple mobile elements that interact together in complex ways, leading to a wide range of possible configurations. For example, there may be one or more robotic arms, conveyor belts, welding presses and wires, among other objects that may move. The appearance of volatile elements such as smoke, sparks and small flames is also possible, all within the normality of the manufacturing cell. Thus, it becomes crucial to build a diverse and representative dataset of the normal activity of the manufacturing cell. To this end, the production process is sampled during a significant number of cycles, ensuring coverage of all workflows and scenarios which do not endanger the safety of the process.

Besides correct scenarios, it is also necessary to capture situations that may compromise the safety of the industrial process. Two groups of incorrect scenarios are identified depending on whether people are involved or not. The most hazardous element that can be found inside the manufacturing cell is a person, because the possible consequences are serious damage, disability, or even death. To avoid it, it is essential for the system to detect situations in which people, partially or totally, are inside the production perimeter. Consequently, we feed the dataset with images of people within the monitored area. These images are captured during the assembly of the installation (mechanics), programming of the robot trajectories (programmers) and other situations that occur during the machine set-up, ensuring that the cell assembly fine-tuning process is not interrupted. Under strict safety conditions, complex situations have also been forced, with humans partially covered by machinery, to test the detection capabilities of the methodology developed. All individuals from whom images were captured to support the experimentation presented in this work have been comprehensively informed and have given their consent.

The second group of incorrect scenarios relates only to the appearance of new strange objects. This second group could potentially have an infinite variability, because it is not possible to restrict the number or type of objects that can appear in the scenario. It is therefore not possible to train our models for all possible situations. But, still, the objective of this work is to detect any kind of uncertain scenarios caused by the presence of any strange object. To achieve this we have developed a novel proposal based on latent space Bayesian analysis described in

Section 5. With the sole purpose of testing our proposals (not to train with them), a dataset of scenes with the presence of different types of strange objects has been generated. All collected objects are commonly found in industrial manufacturing environments and used during machine maintenance and repair, so it is easy for them to remain inside the cell in case of a human negligence. A summary of the collected dataset can be found in

Table 1.

Figure 4 shows an example of an observation from each category. It can be easily seen how strange objects can appear in any area of the cell surface, making it hard for a human operator to check the safety of the cell. Furthermore, some of these objects can be quite small (brushes, drills, wires) and may be partially hidden by some elements of the cell, making their detection extremely challenging.

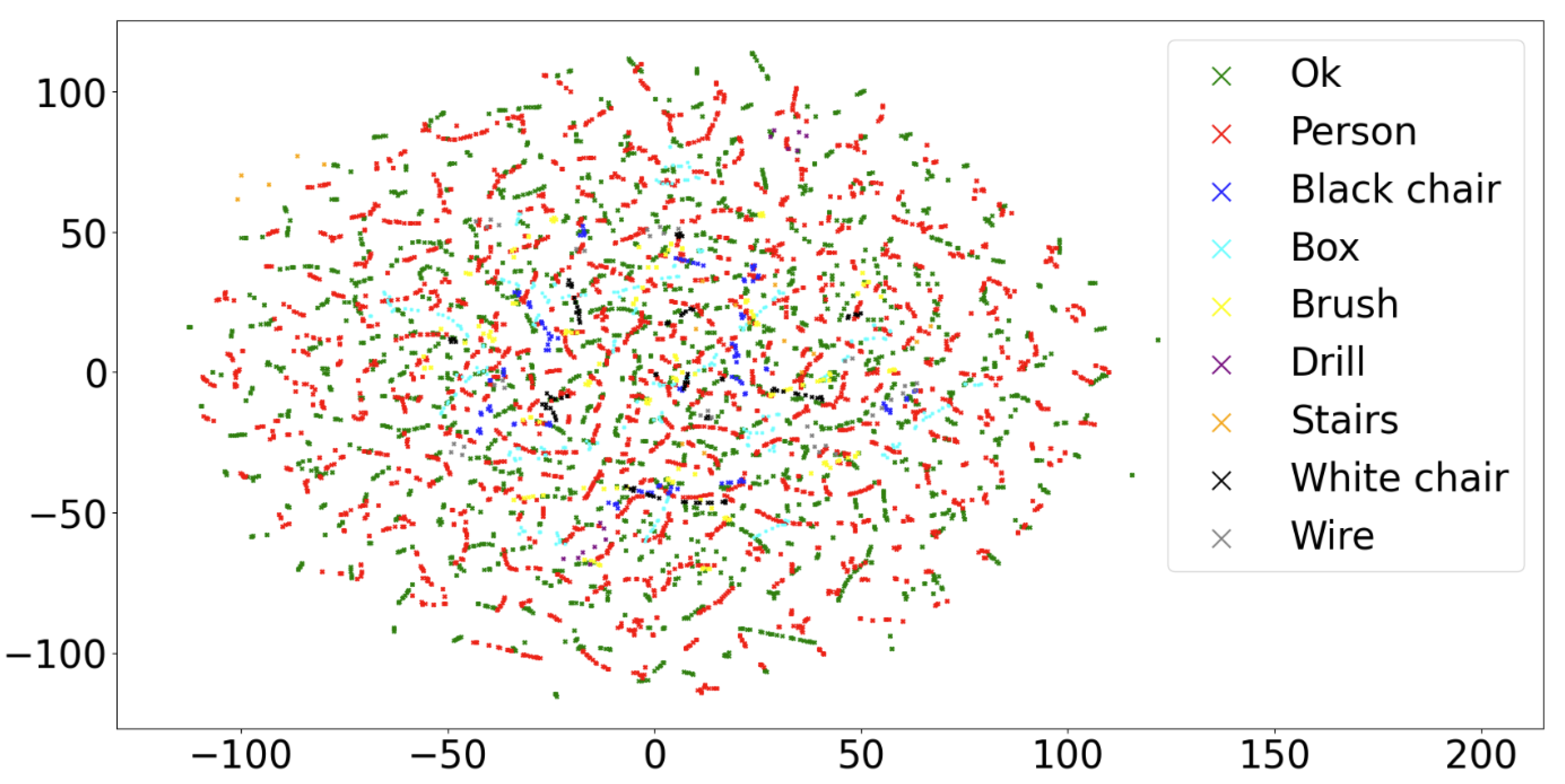

An essential step when building a real-world dataset is to check for the presence of biases that may distort the final results. This event typically leads to unexpected behaviors when the system is in production. In the context of this problem, a biased dataset would be one in which the situations that may compromise the safety of the cell have been captured when the industrial machinery is in unrealistic positions. This would cause the industrial configurations present in the safe and unsafe scenarios to be so different that the DL models could associate the anomalous situations with certain positions of the machinery, rather than basing their decision on the strange object. To check for the absence of this type of bias, we build and analyze an embedding of all the images in the dataset. We use principal components analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). While PCA is used to reduce the dimensionality of the dataset, preserving as much variance as possible, t-SNE is used to project the principal components of each category into a

Euclidean space. The embedding representation can be seen in

Figure 5. It can be noticed that the distribution of the points by category is uniform. There are no isolated clusters belonging to a specific category. All embedding regions are covered by safe scenarios, ensuring that safety-compromising situations have been captured in a normal operating state of the facility. Furthermore, this means that there are no substantial changes in the configuration of the industrial cell between non-safe and safe categories and that the strange objects represent only minor deviations of the correct configurations.

3.3. Supervised Deep Contrastive Learning

The number of scenarios that can lead to an unsafe state of the cell is practically unlimited. This precludes the use of standard supervised learning models to search for anomalous situations and validate the production start-up because these kinds of algorithms require a predefined number of classes, i.e., infinite in this case. One possible approach involves the use of unsupervised learning, namely autoencoder-based schemes (see [

37]). This scheme maps each correct scenario to a distribution in the latent space. An inaccurate reconstruction of a sample from the learned distribution could indicate the presence of a strange setup that may compromise the safety of the cell. However, this approach suffers from two main drawbacks. First, this kind of schemes tend to over-smooth the reconstructions due to the use of Kullback-Leibler divergence in the loss function (see [

38]). As a result, the great complexity and variance inherent in the correct scenarios could potentially lead to a problem of persistent false positives (scenarios incorrectly categorized as unsafe), triggering false alarms and, thus, impacting on the productivity of the industrial process. Second, these kinds of solutions are not able to discriminate, and therefore prioritize, between different objects. For example, a person’s foot may occupy the same surface as a drill but are very different scenarios, the former situation involves far greater risk than the latter. It is essential to ensure that the most dangerous scenarios (people inside the cell) will be detected over any other situation.

In order to overcome the aforementioned challenges and endow the system with the appropriate safety capabilities, we propose the use of deep CL. CL is an emerging technique that aims to extract meaningful representations of the input features by contrasting positive and negative pairs of instances. It leverages the assumption that similar cases should be close to each other in a learned latent space, while dissimilar cases should be farther apart. In a standard CL approach, a single positive of each anchor (a slight augmentation of an observation) is contrasted against any other image in the dataset. Thus, the need of supervised learning (labels) is avoided and a topology of representations is generated in the latent space based on the similarities of the extracted features. The problem is that this self-supervised approach would not guarantee that safe and unsafe scenarios lie in regions far enough from each other because sometimes their discrepancies are minimal. And this is a very important problem in our context because we have a set of highly diverse scenarios that belong to the same positive class (safe scenario) and the same happens for the negative class. In addition, we have two subsets in the negative class. The first subset represents the intrusions of people, which has much more relevance than the second subset, any foreign object. Therefore, the objective is to project all the images of the positive class in a narrow region of the latent space and, at the same time, to keep this region as far away as possible from the representations of the scenarios that seriously compromise the safety of the cell. For this purpose, we rely our learning scheme on the supervised version of the CL paradigm of [

39]. This discriminative approach allows capturing the complex features underlying the correct scenarios and to distinguish them from any potential dangerous disturbance.

The supervised CL scheme will be trained with only two categories of images: Ok and Ko. This approach has two main advantages. First, by using supervised training with humans, it is guaranteed that the system will deliver excellent performance to avoid situations that may compromise people’s integrity. Second, models are trained to synthesize the complex set of features that characterize a correct scenario, learning that any perturbation of these features must be projected into a distant region of latent space. This behavior implies that disturbances caused by a wide range of uncertain and potentially dangerous situations can be resolved without the need to train the network with all the specific cases, which would be impossible. Experimentation associated with the detection of the most dangerous scenarios is described in sec:experimentalResults, while the uncertainty management for the detection of strange situations (any foreign object) is shown in sec:generalizationUncertainDomains.

3.4. Training Specifications

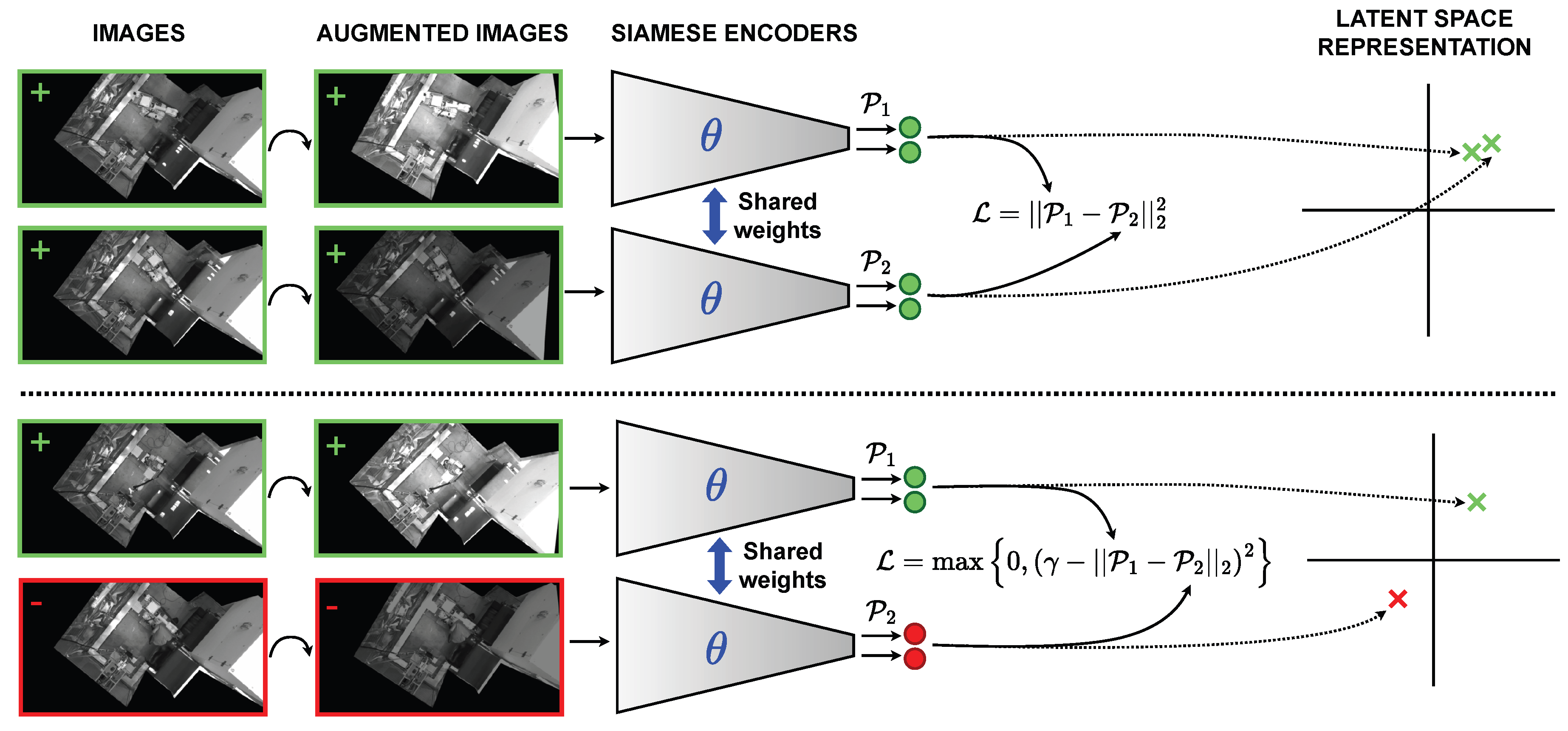

The designed architecture scheme can be seen in

Figure 6. Our approach adapts the idea presented in Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations (SimCLR; see [

40]), which targets robust, label-free representations of images by applying random data augmentation techniques. We adopt the same concept, but using the supervised CL scheme explained in

Section 3.3. We design random data augmentation transformations aiming to achieve robustness to the different perturbations that a capture device may suffer in an industrial manufacturing production environment. Mainly, these disturbances arise from changes in ambient light conditions and vibrations of the capturing device. Therefore, the data augmentation transformations used are based on color space and geometric space alterations (see taxonomy in [

41]). To this end, rotations, translations, brightness changes and Gaussian noise are randomly applied at each epoch to the images that are introduced to the network. We compose all the aforementioned transformations, allowing the model to learn better representations of the data, as discussed in [

40]. A visual effect of these augmentations can be appreciated in

Figure 6. With this technique, we ensure consistent system performance when faced with variable physical conditions, which is very common in an industrial deployment.

Regarding the models, we propose to implement a wide variety of configurations to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposal, regardless of the specific characteristics of each particular design. To this end, we use encoders from three widely used convolutional neural networks (CNNs) families that are in the state of the art: ResNet ([

42]), DenseNet ([

43]) and EfficientNet ([

44]). We also use a ConvNeXt network, a modern transformer-inspired CNN architecture that leverages the power of depth-wise convolution to deliver superior performance on vision tasks (see [

45]). Finally, we also utilize a Cross-Covariance Image Transformer (XCiT; see [

46]), a transformer architecture that combines the accuracy of conventional transformers with the scalability of convolutional architectures by leveraging a transposed version of the self-attention mechanism that operates across feature channels rather than tokens. From the ResNet family we use the version with 18 hidden layers, from the DenseNet family the variants 161 and 201, and from the EfficientNet family the smallest model, B0. For ConvNeXt and XCiT architectures, we use the nano versions. The reason is that big transformer and transformer-inspired architectures typically requires larger amounts of data to achieve comparable performance to CNNs (see [

47,

48]), and the dataset in this work is relatively small. For all models, we start the learning process from a pretrained version on the ImageNet dataset (see [

49]). By so doing, we achieve a faster convergence and reduce the computational cost as the models have already learned basic features useful for many types of computer vision problems, regardless of the context and the specific task.

We propose to use the contrastive loss function in Equation (

1), where

represent a pair of augmented images,

represent the corresponding labels,

the

branch of the siamese neural network, and

the margin that defines a threshold distance in the embedding space. In this work, we empirically set

since it represents a sufficient margin to allow the CL process to clearly separate

Ok and

Ko observations in the latent space, but this hyperparameter may vary depending on the problem. For images of the same class (two positive examples;

), the loss function tries to minimize their square Euclidean distance in the latent space. For images of different class (positive and negative examples;

), it seeks to maximize their embedding square Euclidean distance at least as far as indicated by the

margin.

Besides data augmentation, we employ two additional regularization techniques. First, we perform L2 or Ridge regularization, in order to keep the weights of the model small, learn simpler representations and therefore generalize better to unseen scenarios. Second, we select the best model achieved on the validation set over all training epochs (200), avoiding the effects of potential overfitting in the final stage of the learning process. We use the Adam optimizer [

50] and an initial learning rate of 0.001, dynamically multiplying it by a factor of 10% if learning plateaus during ten consecutive epochs. To validate our methodology, we divided the dataset into four subsets: train, validation, supplementary train and test. While train and validation subsets are used to perform the learning process of the neural networks, the supplementary train and test subsets remain unseen at this stage of the process. Regarding the supplementary training subset, it is made up of a small subset of

Ok situations, and it will be used to fit methodology after training DL schemes (more details will be given in

Section 4 and

Section 5). With respect to the test set, it is made up of images not included in any previous subset, which will allow us to validate the overall process. It contains a subset of the

Ok category, a subset of the

Ko category (only humans), and all the scenes with objects that may potentially represent a risk to the cell’s safety (to preserve their uncertainty status). This last category, named

Other objects, has not been used in the training phase. A summary of the number of elements contained in each dataset by category can be found in

Table 2.

For the training process, we used a server with an NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPU with 24 GB RAM and an AMD Ryzen 9 5900X 12-core CPU. The training time is, on average, less than 5 hours. This quick training time allows for a dynamic re-adaptation to a changing industrial environment that may require a slight fine-tuning of the system.

4. Experimental Results for the Base Safe/Unsafe Scenario

This section presents the results obtained for the problem of identifying the safe scenarios (

Ok) from the most dangerous ones (presence of person;

Ko).

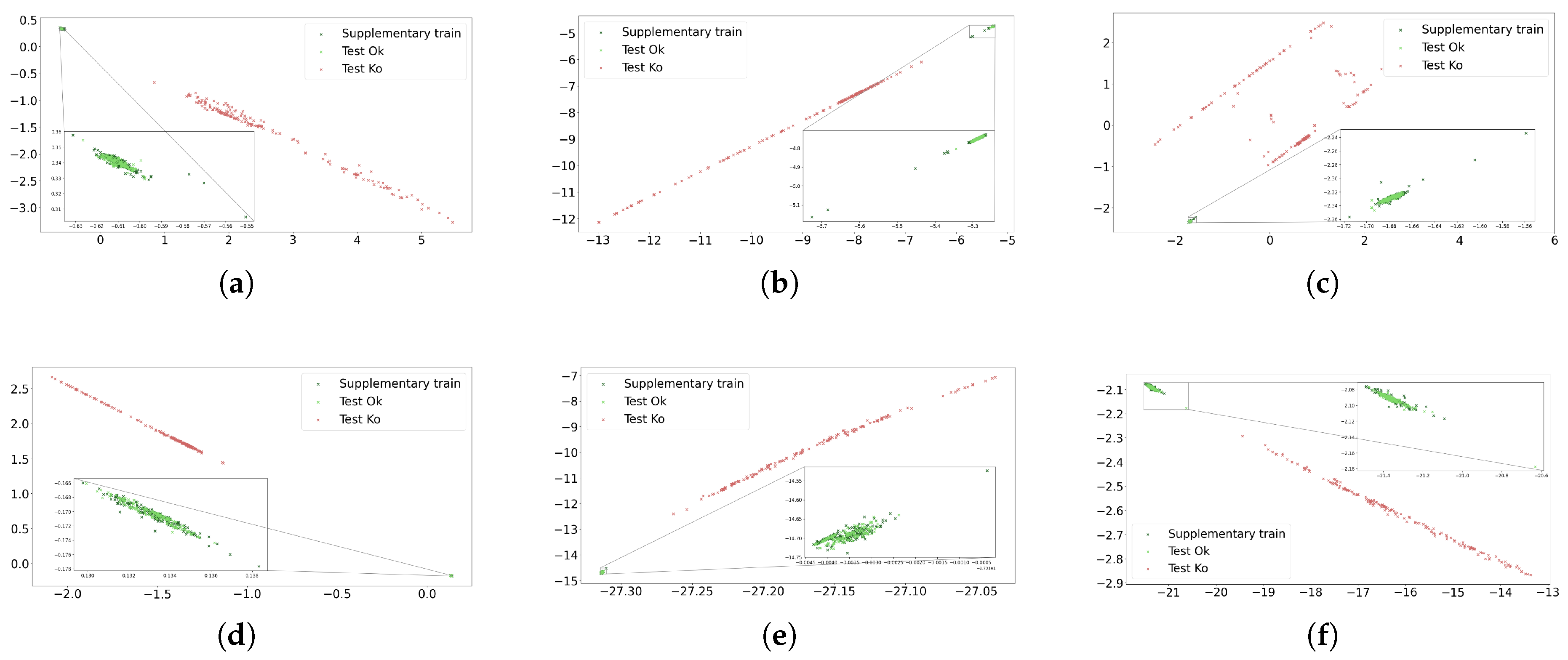

Figure 7 shows, for the supplementary train and test datasets, the distribution of the latent space learned by the six encoders detailed in

Section 3.4. We note that, once the CL schemes are trained, the feedforward step can be performed through any of the two branches of the siamese networks to compute the latent space representations. For all cases, we can identify two well-defined patterns. First, the

Ok and the

Ko scenes from the test dataset are projected in regions far away from each other. This means that the CL schemes are correctly associating the disturbances produced by the presence of people as features that comprise the safety of the manufacturing cell. Second, it can be noticed that all the positive examples, either from the supplementary train or from the test dataset (both not used in the training phase), form an isolated and compacted cluster. This means that the models are able to synthesize the underlying characteristics of the safe scenarios, despite the great diversity among them.

Beyond the latent space morphology, it is necessary to design a strategy to, in the face of a new scenario, give it the category of safe or unsafe. In this case, where the differences are clearly defined, a simple but useful technique is based on the nearest neighbor search (see [

51]). It is important to perform the nearest neighbor fit using an auxiliary dataset not used in the training phase because if the fit were made using the training or validation sets, the process would be biased by the model’s implicit knowledge of them and the results would not be representative. That’s why we use the latent space representations from the supplementary train dataset. By so doing, we measure the Euclidean distance from each observation in the test dataset to its nearest neighbor from this supplementary dataset. The nearest neighbor search is described in Equation (

2), where

and

represents the supplementary train and test datasets,

one of the siamese network branches, and

and

observations from the test and supplementary train datasets respectively.

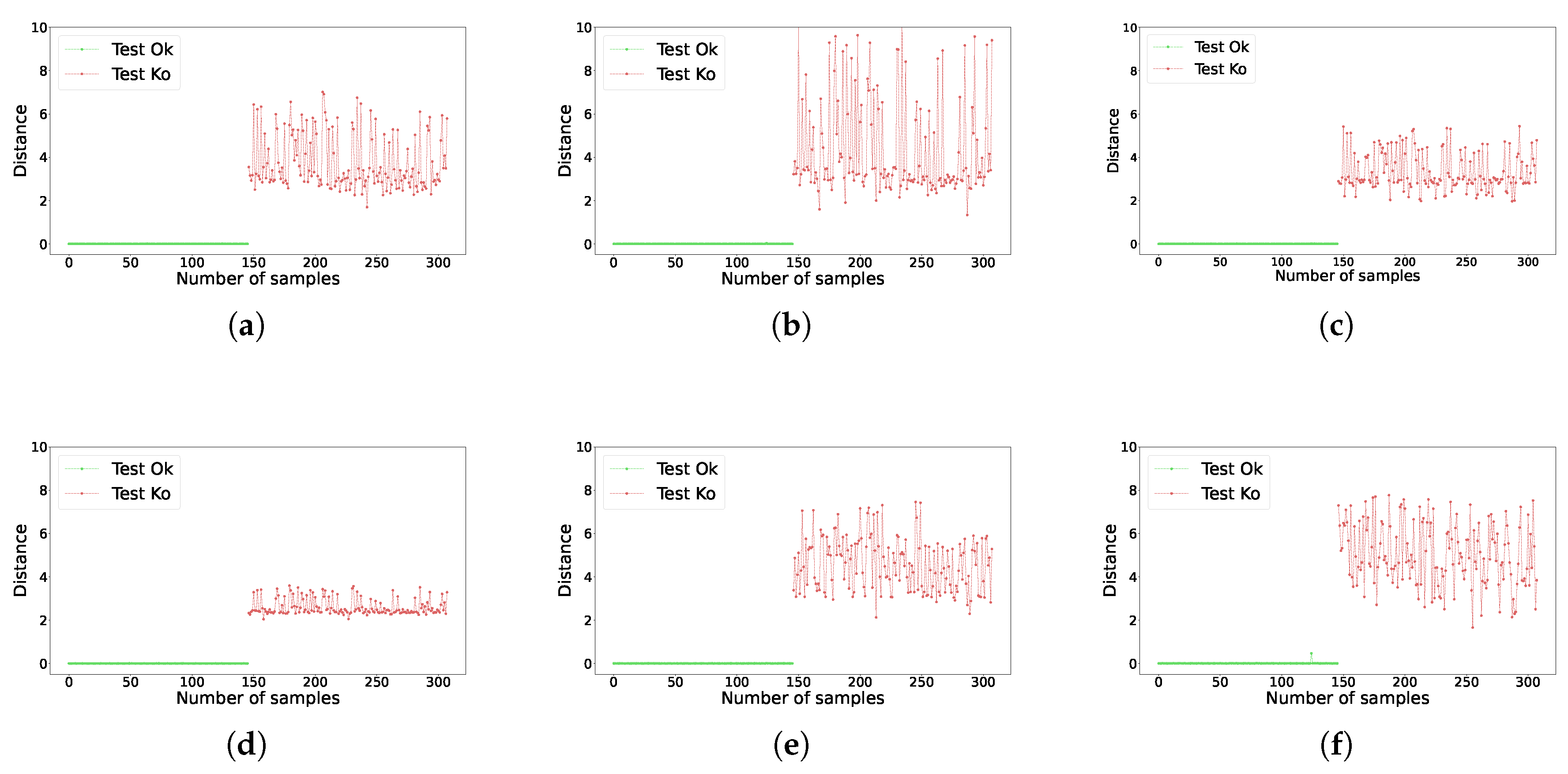

By doing this, we quantify how distant is each test set representation from the nearest safe scenario. These distances are shown in

Figure 8. It is easily noticeable how, for every network, all the distances obtained for the

Ok class are notably smaller than all the distances obtained for the

Ko class (remember that all instances in the supplementary dataset belongs to the

Ok class). These results can be used to build a wide range of binary classifiers to diagnose whether a scenario is safe or unsafe. To this end, it is enough to set a threshold that lies at a midpoint between the distances of the

Ok and

Ko classes. The closer this threshold is to the average value of the

Ok distances, the higher the probability that an unsafe scenario will not be misdetected.

These results show that the base case is solved, that is, safe and unsafe scenarios are correctly identified. The proposed approach can enhance the safety of industrial manufacturing cells and avoid high-risk situations for humans through a robust process that does not interfere with the production cycle of the machine.

5. Generalization to Unknown Non-Legitimate Scenarios: Uncertainty Quantification

The main situation that causes the manufacturing cell to reach a critical risk state is the presence of people inside it. However, this is not the only potential source of risk that may affect the integrity of the industrial process. There is a nearly unlimited set of strange situations, caused by the presence of anomalous objects, which can cause damage to the cell equipment and thus severely impair the productive cycle. These objects, commonly found in industrial manufacturing environments, interfere with the industrial process mainly due to human oversight, causing accidents with severe economic consequences. To limit the occurrence of such events, it turns necessary to develop DL methodology with the ability to identify that wide range of potentially dangerous situations. The number of objects and situations that can potentially damage the industrial process is not limited, limiting the application of conventional supervised methodologies.

Therefore, we propose an unsupervised approach based on the CL methodology presented in

Section 3.3. As explained, this model was trained in a supervised way to differentiate safe from unsafe (risk of harm people) scenarios. By doing so, this scheme manages to synthesize the features that characterize safe scenarios, despite their wide variability due to the large diversity of interactions and configurations that may happen within the cell. Using a supervised approach exclusively with the person class not only provides confidence against the most critical element, but also makes the models learn that any deviation from the components and interactions that make up the safe scenarios has to be projected at a point far away from the cluster formed by the safe situations in the latent space. Therefore, by adopting an unsupervised approach with the unlimited number of anomalous objects, we are able to detect most of the potentially unsafe situations for the manufacturing process, even though they are caused by completely new and unseen (not used for training) objects and situations.

In this section, we first explain the Bayesian methodology applied in the latent space to detect and quantify the uncertainty caused by the presence of situations which present deviations from the safe scenarios (

Section 5.1). Next, in

Section 5.2, we present and discuss the results obtained. Finally, in

Section 5.3, we propose the creation of a hybrid latent space for maximizing the detection of uncertain situations.

5.1. Bayesian Gaussian Mixture Model (BGMM)

The latent space distribution expected when computing the image representations of the anomalous objects will be much more complex than the analyzed in

Figure 7 (

Ok vs

Ko). The reason is that the

Other objects category has not been used during the supervised CL training, so the differences between the safe and the potentially unsafe scenarios are likely to be slight. The nearest neighbor approximation (see

Section 4) may be valid in situations where differences between the different classes’ latent space representations are relatively large. However, this approach lacks robustness in the presence of intermixed and poorly defined groups of representations. Therefore, it is necessary to design a suitable approach to synthesize and estimate the density of the distribution of

Ok observations in the latent space. Likewise, it is important that such approximation allows to quantify the discrepancy between an unknown scenario with respect to the set of safe representations. This quantification will provide a way to set dynamic thresholds in an industrial deployment, thereby offering flexibility to control how sensitive the system is in detecting uncertain conditions. Gaussian mixtures are very well suited for this purpose. These are a family of methods which provide flexible-basis representations for densities that can be used to model heterogeneous data (safe representations in this case). Gaussian mixtures can be estimated using frequentist or Bayesian approaches.

Under the frequentist approach, clustering is performed using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm, with the parameters of the mixture model usually being estimated within a maximum likelihood estimation framework [

52]. Point estimates derived from the EM algorithm can be sensitive to outliers, potentially leading to biased parameter estimations and poor model performance. To mitigate this problem, we propose the use of the Bayesian approach. The main advantage over the frequentist scheme is that it incorporates a regularization method by adding a prior knowledge of the model parameters. This prior distribution increases robustness to atypical patterns, which is particularly useful when dealing with small or sparse datasets that may have outliers (see some extreme values in supplementary train representations in

Figure 7). The result is that the posterior distribution tends to be less influenced by extreme observations compared to frequentist point estimations. In our case, this approach better captures the underlying trend of the

Ok data distribution and, therefore, it is more suitable to detect scenarios that slightly deviate from the safe region. To this end, we infer an approximate posterior distribution over the parameters of a Gaussian mixture distribution using Bayesian variational inference. We use an infinite mixture model with the Dirichlet Process in order to define the parameters’ prior distribution. For the posterior distribution estimation, we use the variational inference algorithm for Dirichlet Process mixtures presented in [

53]. The implementation used for this algorithm has been taken from [

54].

For detecting the potentially unsafe scenarios, we first fit a Bayesian Gaussian mixture model (BGMM) on the supplementary train subset. By so doing, we are robustly capturing latent space distribution of the safe scenarios. Then, knowing that we have the safe scenario behavior summarized in the posterior distribution, anomalies are identified based on their log-likelihood scores. If an observation gets a low log-likelihood score, it implies that it is less likely to have been generated by the BGMM. On the other hand, if an observation obtains a reasonably high log-likelihood, this suggests that it is very likely that this observation can be sampled from the a posteriori distribution learned by the Bayesian framework. This approach allows for the explicit quantification of uncertainty and, therefore, for the detection of unknown scenarios that may potentially represent a danger to the integrity of the manufacturing cell.

5.2. Results

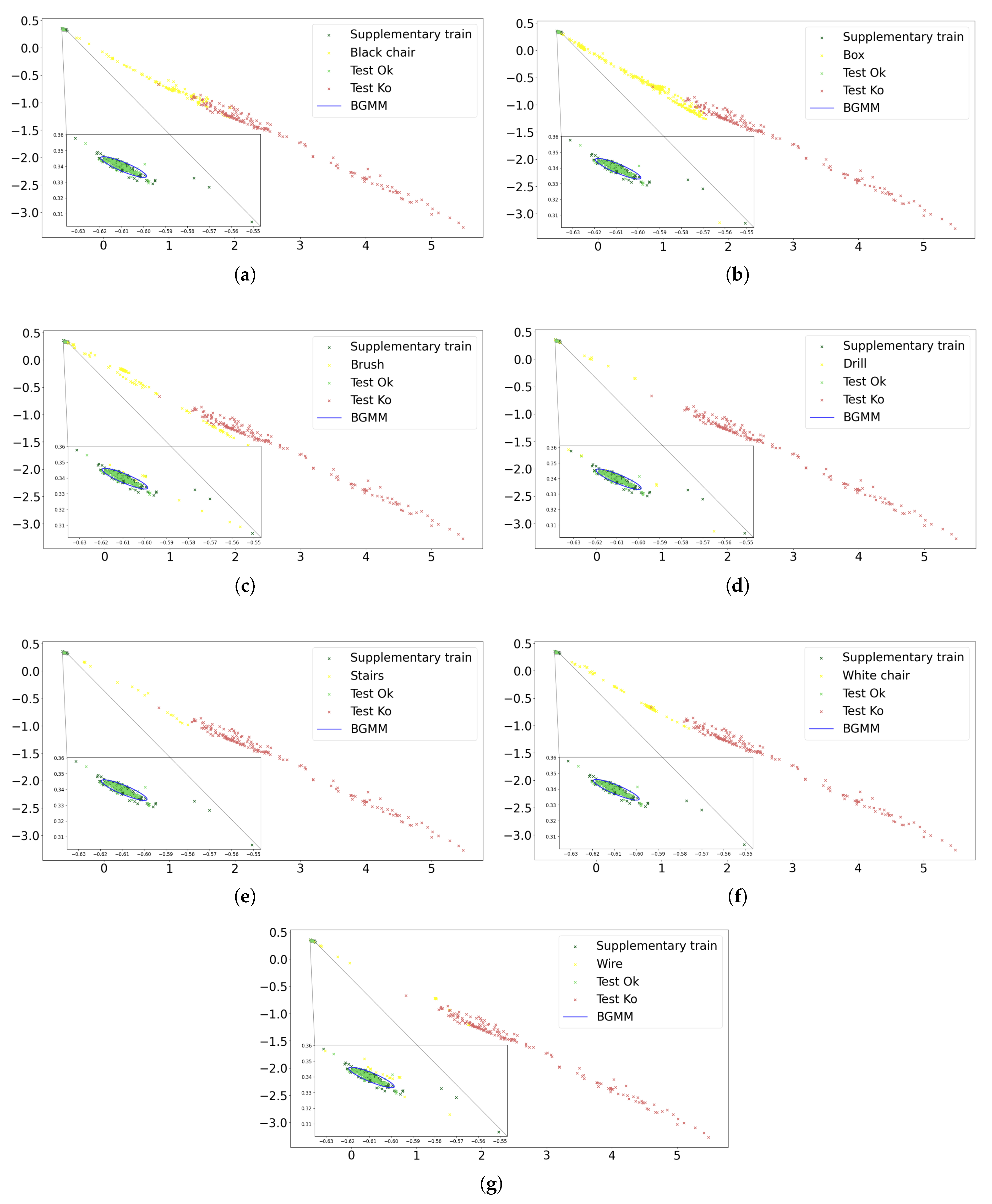

The first step to quantify the performance of the scheme when facing uncertainty is to compute the latent space representations of the scenarios belonging to the

Other objects category. We will only plot the results for the best performing model, which is ResNet-18, as will be discussed later. These results can be seen in

Figure 9. Each of the seven subfigures shows, respectively, the representations obtained for the scenarios with the presence of each of the seven anomalous objects (described in

Table 1). Similarly, each subfigure also shows the supplementary train and the

Ok-

Ko test set representations (the same as

Figure 7a). The general trend indicates that the representations of the scenarios with potential safety risk are projected in regions far away from the cluster of

Ok observations, namely in an intermediate region between the

Ok and the

Ko representations. Although these anomalous scenarios often present very small deviations from a correct situation, the proposed CL methodology is able to detect and focus on the unknown features that do not characterize the safe scenarios.

Once we have these representations, the second step consists in fitting the BGMM on the projections of the supplementary train dataset. The fitted mixture corresponds to the blue ellipse in

Figure 9. To represent this ellipse, we use the mean, covariance, and shape of the estimated supplementary train distribution in the latent space. A closer look at the fit reveals that it is not influenced by the presence of some small outliers (belonging to the supplementary train set). Such robustness implies that the vast majority of representations of the

Other objects category lie outside the ellipse that characterizes the estimated distribution, which will result in a high success rate in detecting the unknown scenarios.

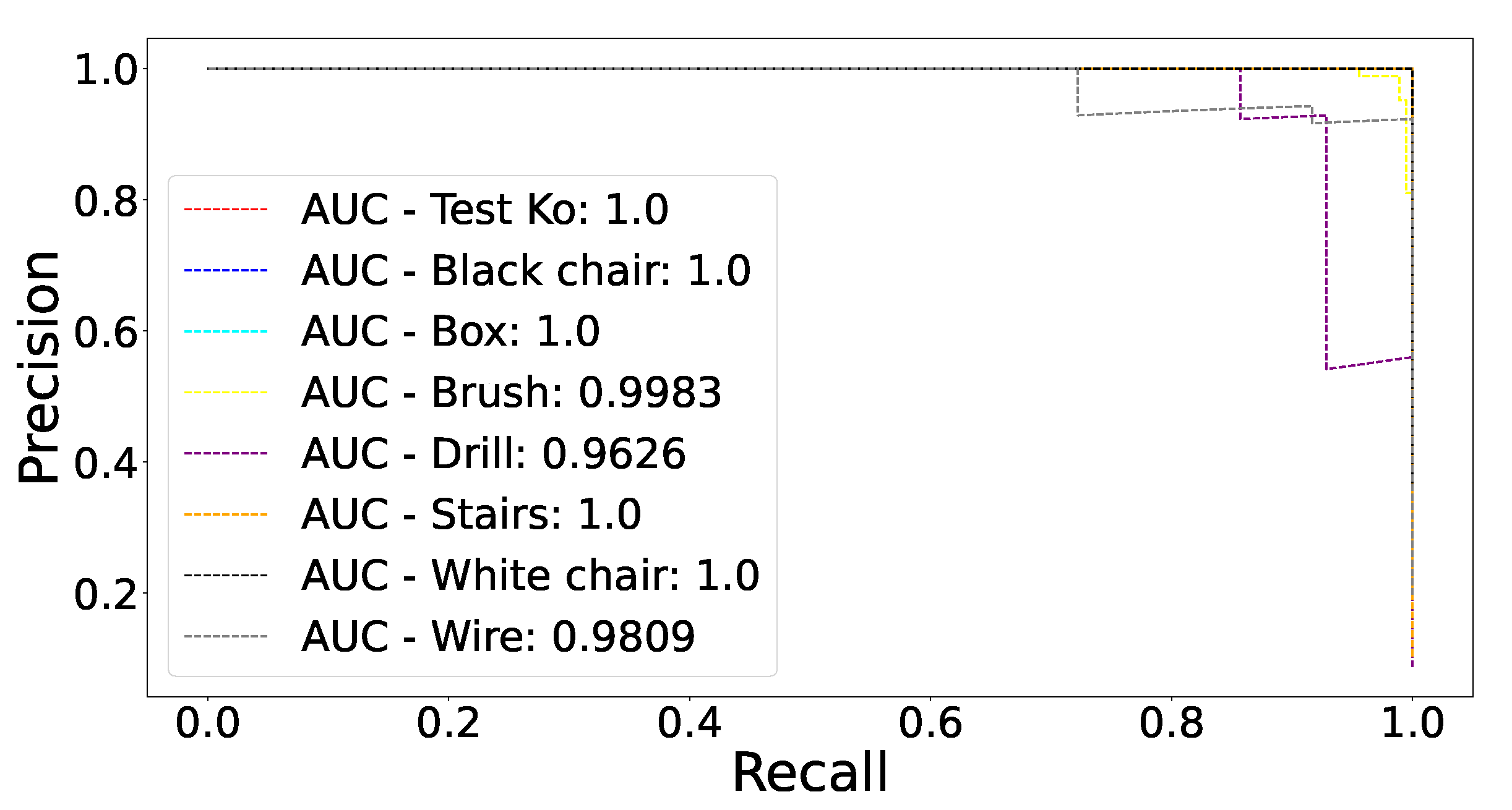

As argued in

Section 5.1, in order to quantify the performance of the models, we will identify anomalies by computing the log-likelihood that each observation could have been generated by the BGMM. Using these log-likelihoods we can build, for each anomalous object, a precision-recall (P-R) curve showing the model’s ability to distinguish between safe and potentially unsafe scenarios caused by the concerned object. We use a P-R curve instead of a more straightforward metric, such as the accuracy, because the former is much more robust to class imbalance and allows visualizing the tradeoff between the cost of type I and type II errors. Since P-R curves focus on the performance of the positive class (class with the highest scores), it is necessary that this becomes the class that captures the unsafe or potentially unsafe scenarios. Otherwise, the results would be biased by the safe class and would not be focused on the anomalous situation detection. For this purpose, we need to invert the obtained log-likelihood scores. After this simple transformation, observations with a low probability of being generated by the BGMM model will have high associated scores, while observations with a high probability of being generated by the BGMM model will have low scores. Thus, false positives represent situations where a safe scenario is identified as unsafe, and false negatives represent situations where an unsafe scenario is identified as safe. The P-R curves, and their area under the curves (AUCs), obtained for the best performing model on the test set are shown in

Figure 10. Each P-R curve represents the binary problem of discerning between the test safe (

Ok category) and unsafe (

Ko category) or potentially unsafe scenarios (seven curves, one for each anomalous object present in the

Other objects category). Performing the same process, the AUCs obtained for all models are shown in

Table 3. It can be appreciated that the ResNet-18 encoder is the one that achieves the best results, with a mean AUC of 0.9928. It is able to identify as unsafe all scenarios where four of the seven anomalous objects (black chair, box, stairs and white chair) are found. For the scenarios with the presence of the other three anomalous objects (brush, drill, wire), the AUC is considerably higher than 95%. These results reflect the great ability of the CL-BGMM methodology to derive the characteristics that define a correct scenario and identify any uncertain variation, however small, as a situation that carries a potential safety risk. For the other results, the overall performance of the different encoders is very good when the anomalous objects cover a relatively large proportion of the image pixels (black chair, box, stairs and white chair). As the strange objects gradually decrease in size, some of the models lose the ability to discriminate from the safe scenes. This behavior aligns with the desirable situation in an industrial deployment, since the smaller an anomalous object found illegitimately in the cell, the more likely it is that it will not constitute any safety or feasibility risk to the manufacturing process.

5.3. Hybrid Latent Space for Performance Maximization

The results presented in

Table 3 show considerable oscillations for some categories. Mainly, these are the ones that represent the presence of small objects that barely alter the safe state of the cell (brush, drill, wire). This variance arises from training with different architectures (CNNs of different families and complexity and a vision transformer) and a CL methodology fed by randomly augmented images. Thus, each model learns to synthesize a different set of high-level features from the data, achieving a high diversity of results. This diversity allows exploiting the concept of ensemble learning in order to maximize the overall performance of the pipeline. Ensemble learning refers to the methodology that combines two or more baseline models in order to obtain improved performance and better generalization ability than any of the individual base learners [

55,

56].

In this work, we propose to use ensemble learning as an intermediate phase between the CL training and the Bayesian mixture fit. This process is made up of two different stages. In the first stage, we combine the results coming from two different CL schemes. The selected aggregation mechanism is the concatenation. This process is illustrated in Equation (

3), where

and

represent two different

latent space representations of the observation

, ∥ the concatenation operation,

the dataset, and

the set of representations in a

latent space. The reason for concatenating individual latent spaces to form a latent space of higher dimensionality is to leverage the strengths of each individual model for those categories where it performs best, while mitigating potential discrepancies. We assume that an individual model is able to project scenarios with the presence of a specific anomalous object far away from the cluster of safe scenarios, so, when combined with other model, this discriminative power is transferred without perturbations to two of the dimensions that compose the 4-dimensional latent space. If the second model is also able to project such scenes away from its safe scenario cluster, then there will be a clear separation in the two groups of dimensions of the compound latent space. Alternatively, if the second model performs poorly for that category, the compound latent space still maintains a high discriminative ability in two of its dimensions, being highly probable that the remaining dimensions hardly impair the separation transferred by the first model. The second stage remains the same, consisting in adjust a Bayesian mixture on the safe representations of the

latent space. As previously described, we employ the supplementary train dataset to perform the BGMM fitting and compute the inverse log-likelihood scores of the test set scenarios (

Ok,

Ko, and

Other objects).

The results of the hybrid latent space proposal can be found in

Table 4. We have selected a collection of seven cases where a varied casuistry is collected: combinations of base learners where both have good performance (ResNet-18 & DenseNet-201), combinations of base learners where a top-performance model and a model with notably lower performance are used (ResNet-18 & DenseNet-161, DenseNet-201 & DenseNet-161, ResNet18 & ConvNeXt-nano), and combinations of base learners where the performance of both models is relatively low (the remainder).

Analyzing the results from a general perspective (), the main point that can be noticed is that, for all cases, the hybrid model improves the results of the best base learner which participates in the combination. By category, the main improvement in the results can be observed in small objects, which are the most difficult to detect. For the drill category, all seven combinations exceed the performance of their base models. In the case of the brush and wire categories, six of the seven combinations achieve an improvement. In the case of the box and stairs categories, the only combinations that can improve the results, do so. For all other categories, when the results of the base learners are perfect, the hybrid model maintains the performance. Analyzing the results regarding the type of combination, it is worth noting that the effectiveness of the method is robust to the underlying performance differences between the models that are combined. For example, when combining two high performance models (see ResNet-18 & DenseNet-201), the ensemble approach achieves improved results in the only categories where there is room for improvement (Brush, Drill, Wire). The features learned by both encoders vary, and their combination allows taking advantage of the situations where each one performs best and obtain a high-dimensional latent space where even the most complex illegitimate variations are separated from the safe scenario cluster. It is remarkable to note the behavior obtained for the cases where two models with different performance are combined (see ResNet-18 & ConvNeXt-nano). The features learned by the simpler model provide discriminative capabilities to the information encoded in the latent space distribution generated by the more complex encoder, inducing a combination that maximizes performance. Finally, when two models with lower performance are combined (see ConvNeXt-nano & EfficientNetB0), the ensemble allows for improved performance in detecting scenarios belonging to the most complex categories.

The best hybrid model obtained (ResNet-18 & DenseNet-201) has almost perfect behavior. In addition to detecting with perfect accuracy all unsafe scenarios due to the presence of people, it is also able to detect all potentially unsafe scenarios caused by the presence of six of the seven unknown objects. The only potentially unsafe scenarios that it is not able to fully detect are those where strange wires are present. We note that this anomalous object is particularly difficult to detect, as a multitude of correct scenarios present wires in a wide range of positions (driven by the movement of the robotic arm) that do not compromise the safety of the industrial process. Even so, the AUC is practically perfect, with a value of 0.9874, reflecting that a very high proportion of them are differentiated from the cluster of safe scenarios.

6. Confidence Against Uncertainty: Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI).

The proposed methodology based on CL and Bayesian mixtures is able to determine very effectively when the industrial cell is in an unsafe state, either by the presence of a person (see

Section 4) or any type of unknown object that may potentially compromise the integrity and reliability of the manufacturing process (see

Section 5). Beyond the results, the application of AI-based methods in a safety-related domain requires a high level of confidence in their decision-making process, as well as in understanding how they will behave when facing with unknown situations which may arise in the future. With the aim of providing confidence and understanding the decisions made by AI models, the field of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) has recently come to the forefront. XAI is a term that refers to AI systems that can provide explanations for their decision or predictions to human users [

57]. This process becomes crucial in some domains, specifically in the safety field (see [

57]). Most existing research on XAI focuses on providing a comprehensive overview of approaches for either explaining black-box models or designing white-box models [

58], being the former the one on which we will focus on this work. The BGMM phase is highly interpretable and does not require any auxiliary process to unravel the underlying mechanism that regulates its behavior. Therefore, we will focus on identifying the factors that determine the decisions made by the DL encoders trained with CL. In particular, we will study which regions of the scenarios cause them to be projected at a point near or far from the cluster of safe scenarios in the latent space. To this end, we will employ two techniques. The first one, proposed in this work, is based on ablations of the initial feature space, while the second one, more conventional and widespread for the diagnosis of computer vision models, is the computation of saliency maps.

6.1. Input Feature Ablations

Ablations, in the context of an AI application, consist of removing one or more of the components that make up the system and examining how this affects the final behavior. Commonly, ablation studies involve adding or removing components from a model (see [

59,

60]). However, ablations can also be performed on the data that serve as input to the models in order to study how their perturbation impacts the performance. For example, data ablations are used in [

61] in order to remove repeated patterns in images and test whether deep neural networks can maintain a high level of confidence in their predictions. In [

59], the concept of data ablations is fully exploited, developing a tool that allows to conduct this type of studies for general computer vision problems. In [

62], the randomized ablation feature importance technique is introduced, where the different input characteristics (independent variables of a dataset) are replaced by a random variable with a marginal distribution according to the original variable, checking for each replacement whether the model’s ability to make a good prediction is preserved.

In this work, we design a novel patch-based input feature ablations method inspired by the work presented in [

62]. Instead of randomly perturb portions of the initial feature space that feeds the DL models, we perform a similarity-based search on the dataset image and replace the patches with others that are geospatially consistent. A visual representation of the developed ablation pipeline can be found in

Figure 11. The first step consists of selecting two scenarios: the one in which the ablation study will be performed (target scenario; typically unsafe or potentially unsafe) and a scenario, as similar as possible to the one to be ablated, belonging to the cluster of safe scenarios. This matching is feasible in our use case, since it is highly probable that, for each unsafe scenario, there is an almost identical safe configuration in which the only difference is the absence of the element that triggers the unsafe state of the cell. The reason for this matching is that partial parts (patches) of the target image will be replaced by the equivalent parts corresponding to the safe counterpart. By so doing, it is possible to generate a much more realistic ablation than would be achieved by replacing the patches with black regions or by randomly filling the pixels. For each of the patch substitutions, and until the entire image is covered, the latent space representation is computed, measuring the deviation produced with respect to the original target representation.

The deviation computation is written in Equation (

4), where

x represents the target image,

represents the function that performs the process of replacing a patch in

x, and

d is the deviation. Therefore, if a patch replacement results in a high deviation with respect to the target representation, it means that the DL scheme was extracting relevant features from the target patch, which caused the scenario to be projected in a region far away from the safe scenario cluster. In contrast, if the ablation barely affects the latent space representation, it means that the corresponding portion of the cell did not contain any significant feature that was determinant in projecting the scenario in the unsafe region. The smaller the size of the patches, the more detailed the information about which areas of the cell contain information relevant to the encoders. Finally, with the deviation computed for each patch, we can build a heatmap that displays which patches cause more deviations and which patches are more irrelevant to the decision taken by the model (the more important, the stronger the yellow color).

Figure A1 (see

Appendix A.1) shows the ablations results obtained for eight

Ko observations of the test set, using the best individual model (ResNet-18) and a 45x60 patches grid. We have selected a varied set of scenarios which are representative of different interactions that humans may have with the manufacturing cell. There are some scenarios where several workers are within the cell (

Figure A1a,

Figure A1b,

Figure A1c,

Figure A1e), where only small parts of workers are visible (

Figure A1b,

Figure A1f,

Figure A1g), and where some workers are partially covered by the machinery (

Figure A1c,

Figure A1h). All these situations have been captured during the set-up and fine-tuning of the industrial process, and are highly likely to be repeated during the life cycle of the machine. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that the decisions made by the DL models are fully justified and without biases that may induce inconsistent behavior. A close analysis of the heatmaps obtained using the input feature ablations technique shows that, in all cases, the patches with a more intense yellow color are those close to the place where the workers are located. As already argued, this means that these patches have the greatest influence on the encoder in projecting the corresponding images far away from the cluster of safe scenarios. Even in the most challenging situations, where only a part of a person’s foot is visible (

Figure A1f) or the person is partially covered by the robotic arm (

Figure A1h), the DL model is able to detect very accurately the small deviations that exist with respect to the set of

Ok scenarios. It is also remarkable that, in the case of scenarios with multiple workers, the DL model is able to detect the presence of all foreign bodies remaining in the cell. The decision to move such scenarios away from the safe cluster is equally influenced by the pixels belonging to the different humans. This behavior shows that the model lacks biases whereby it is influenced more by individuals, or parts of individuals, of greater size.

Similarly,

Figure A2 (see

Appendix A.1) shows the result of applying the input ablations to a set of scenarios belonging to the

Other objects category. Two representative scenarios have been selected for each of the anomalous objects contained in the aforementioned category. It can be noticed that the patches that induce a greater deviation of the representation in the latent space are mostly concentrated in the areas adjacent to the unknown objects. It is worth pointing out the case of

Figure A2h, where the anomaly is caused by a small object (drill) partially covered by the robotic arm. Despite the complexity of identifying the anomaly, the model is able to determine the presence of a foreign body outside the set of patterns that characterize safe scenarios. Another highly complex scenario is

Figure A2n, where an anomalous object (wire) is placed above one of the conveyor belts of the cell. The surface of the conveyor belts exhibit a great variability within the set of

Ok scenarios, since there is a virtually unlimited casuistry in the disposition of the transported parts. However, rather than decreasing its performance in the aforementioned area, the DL model is able to determine the presence of a morphology different from those that are commonly carried by the conveyor belt. Thus, the input feature ablations illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed scheme to detect any type of anomalous object and, therefore, to be robust and provide guarantees of high performance in the event of uncertain conditions.

6.2. Saliency Maps

A widely used technique to explain the decisions made by DL models are saliency maps. This technique, presented in [

63], belongs to the family of gradient-based methods (see [

64]), and relies on the calculation of the gradient of the final prediction with respect to the input of the network. This gradient represents how each input variable contributes to the output prediction. As such, these types of gradient-based methods generate heatmaps which indicate the importance of each pixel in the input space to the network’s final prediction [

65]. Saliency maps were originally designed from the perspective of a classification paradigm, estimating the areas of the image that were most important in order to assign the input to a particular category (see [

63]). Typically, the backpropagation-based computation of the gradient starts from the neuron associated with the class that has obtained the highest score. However, in this works, DL models belong to the CL paradigm, so the target of the final layer is not the same as in a classification scheme. Each neuron in the last layer represents one of the two dimensions of the latent space into which the inputs are projected, and does not compute a score associated with a classification approach. Therefore, when choosing from which neuron should start the gradient computation, it would not be correct to select the one that computes a higher value (which would be the case in a classification problem as the higher value would represent the most likely class). To overcome this, we propose to always choose the same neuron, namely the one associated with the dimension of the latent space that gathers as much variance as possible. This dimension will have a higher discriminatory power, so it is more likely that its backpropagation will obtain the most relevant saliency maps, showing the image characteristics that determine whether it belongs to the safe cluster or not. Regarding the best single model (ResNet-18), this dimension corresponds to the first one (

x-axis in

Figure 9). Thus, to compute the saliency maps, we will always use the neuron associated with the

x-dimension of the latent space as the starting value for the backpropagation.

In

Appendix A.2,

Figure A3 and

Figure A4 show the results obtained for a test set sample of the

Ko and

Other objects categories respectively using the best single model (ResNet-18). As with the previous XAI technique, we have selected a set of representative scenarios that cause the cell to fall into an unsafe state. Analyzing the scenes with the presence of humans (

Figure A3), it can be appreciated that the regions that take a greater importance when projecting the scenarios far from the safe cluster are those where the workers are located. As already shown using the input feature ablations, this behavior is consistent regardless of the size of the person. In

Figure A3a, the network is able to rely its decision on the presence of a person’s leg. Similarly, in

Figure A3b, the DL model detects that the disturbance of the safe scenario comes from the presence of a body part of a person. In

Figure A3c and

Figure A3h, the regions with the greatest influence on the input come from both a complete and a partial body, showing the robustness of the proposed scheme regardless of the human morphology. Likewise, the model is able to draw its judgment from information coming from different areas.

Regarding the scenarios where unknown objects are found (

Figure A4), the results derived from computing the saliency maps are satisfactory. The technique reveals that the portions of the image that condition the network decisions are those with anomalies. It is worth highlighting some challenging situations, such as

Figure A4b, where the black chair is almost entirely covered by the robotic arm, yet the DL model is able to identify the slight unknown disturbance in that area. In

Figure A4e, the scheme bases its decision on the identification of two foreign bodies (brushes) whose characteristics are not representative of the normal operation of the manufacturing process. We note that one of these brushes is extremely difficult to detect (the one on the right), both because of its small size with respect to the cell and because it is just located in the area of the conveyor belts and the containers where the parts that the robot fails to pick up fall. Despite the set of

Ok scenarios contains a high variability of situations in the aforementioned area, the DL model is able to detect that the morphology of the brush, although extremely fine, diverges from the morphologies that may appear in that zone during a correct operation state. This case is similar to the one reflected in

Figure A4n, where even though a wire is placed in the container where the parts of a conveyor belt may fall, the DL model is able to determine that there is an unknown morphology. In

Figure A4m, the two areas with presence of anomalous wires influence the results provided by the network. This case is highly complex to detect, as there are certain allowed robot wires patterns around those areas contained within the set of safe scenarios.

Overall, the results are consistent with those obtained using the proposed patch-based input feature ablations method, reflecting the high quality of the predictions. The proposed CL scheme is able to synthesize and base its decisions on the non-legitimate disturbances of the industrial cell, whether known (people: Ko) or in the face of uncertainty (anomalies: Other objects). Consequently, the Bayesian mixture is indeed able to quantify very accurately the deviation that each non-legitimate situation entails from the set of characteristics that determine the safe scenarios. The XAI techniques presented in this work ensure that the proposed scheme is free of biases that may distort the obtained results and, therefore, lead to long-term inconsistent behavior when deployed in an industrial plant. Likewise, we show that DL models will perform properly when dealing with any abnormal event not covered during their training phase. The proposed pipeline provides guarantees to successfully manage the uncertainty that may arise in advanced manufacturing environments.

7. Industrial Deployment

In this section, we detail the characteristics of the industrial deployment that has enabled us to carry out the experimentation described in the work and assess the performance of the system in a real production environment. Similarly, we will also describe the main limitations encountered in the study, as well as the new lines of research that are already being developed. The pipeline based on CL and Bayesian clustering has an average inference time of 50 miliseconds using an industrial PC (IPC, see characteristics in

Section 3.4). This implies that, on average, the AI auxiliary safety channel will deliver outputs at 20 frames per second (FPS). The speed of the method allows it to be used in two different operating modes:

Cycle-triggered monitoring mode: the system will diagnose the safety of the industrial space only at the start of each production cycle.

Continuous monitoring mode: the safety check will be performed periodically every 50 miliseconds.

Both operating modes are meaningful depending on the layout of the monitored cell and the safety devices already integrated. For instance, in a completely fenced-off cell whose only access point is an industrial door, checking for the presence of unauthorized elements at the cycle start is enough, since once started the safety chain of the installation cannot be broken unless the door is opened. On the other hand, a cell in which the operator can load components or access the machinery during the cycle benefits from the AI safety system continuously checking the legitimacy of the process. In the industrial configuration described in

Section 3.1, data has been collected, and so the system evaluated, using captures during the active industrial cycle, i.e., continuous monitoring mode. The reason is that the machine has two entry and exit points (conveyor belts) through which an untrained or malicious worker can easily access the interior of the facility and easily throw unexpected objects. The programmable logic controller (PLC) used is a Siemens SIMATIC S7-1200F safety CPU, with 8 digital inputs and 6 digital outputs. We also use a Siemens SIMATIC S7-1200 digital I/O module, Relay output SM 1226 with PROFIsafe for communication between the digital outputs and the facility’s actuators (robot, welding press, conveyor belts). This module allows to send the stop signal when the safety circuit is broken. To communicate the IPC with the PLC, a digital I/O card connected via Ethernet to the IPC is used, which also interfaces to a safety-rated digital input module of the PLC. In addition, the PLC implements a watchdog system that determines whether the IPC is active by checking whether a bit in its DB is modified every 20 milliseconds. When the AI safety channel detects any non-legitimate situation, the software running in the IPC displays in a monitor an image generated using input feature ablations (see

Section 3.1) to help workers diagnose what is triggering the safety alert.

7.1. Limitations and Future Work

Two main limitations have been identified that need to be addressed in future research. The first one is the possible sensitivity to the general lighting conditions of the facility. Generally, all DL algorithms, even when trained with data augmentation that distorts the color space (brightness, saturation, contrast, etc.), tend to overfit the underlying lighting conditions in the training datasets. The industrial belt picking cell monitored in this study has an LED lighting system that provides homogeneous illumination across the cell surface. However, at the end of the luminaires’ useful life or in the event of an unexpected error, lighting conditions may deteriorate and affect system performance. Moreover, if the machine is located in an industrial plant with large windows, direct sunlight can cause glare or saturation that may distort the AI results. Therefore, a possible future line of research can be focused on using near-infrared (NIR) lighting and NIR-sensitive cameras that isolate the vision system from the lighting conditions in the plant.

The second identified improvement is related to the rapid deployment on new machines or the ease of adaptation to layout changes. The significance of this utility is described in [

33,

34]. Currently, the CL-based method proposed has been trained in a supervised manner using images representing the machine in a safe state (normal production cycle) and images of an unsafe state (workers performing maintenance tasks within the facility and tricky situations forced to evaluate the method’s performance). This implies that, in case of a machine layout change, it would be necessary to recapture the set of safe and unsafe scenes. Although safe scenes are easy to record (normal production cycle), unsafe scenes require time and effort. To solve this problem, Aparicio-Sanz et al. in prep. will propose a methodology derived from the one presented in this paper called human augmentation, which allows for plug-and-play operation in a new installation or when changing an existing layout.

8. Conclusion

In this work, we create a DL system based on CL and Bayesian analysis that improves the safety conditions achieved through the application of traditional functional safety devices in industrial manufacturing cells. Using data from an automated press welding cell fed by a belt picking process currently in production, we develop a DL methodology to discriminate between safe and unsafe scenarios, the last ones characterized both by the presence of people and anomalous objects. First, using supervised deep CL framework, we obtain robust latent space representations by maximizing the distances between safe and human-present scenarios. Second, fitting a Bayesian Gaussian mixture to the learned latent space distribution, we robustly synthesize the underlying trend of the safe representations, detecting those scenarios whose features deviate from safe behavior, i.e., scenarios with the presence of non-legitimate elements. We get a perfect AUC for discriminating between safe and human-present scenarios, and an average AUC of 0.9982 for discriminating between safe scenarios and scenarios with seven types of anomalous objects that have not been seen during the training. Hence, besides reliably identifying human presence, we are able to detect any kind of anomalous object even without having been involved in the learning process of the DL model. Furthermore, by combining different DL schemes through the generation of an ensemble-based hybrid latent spaces, we are able to join the discriminating features of the underlying models and maximize the overall performance. In order to provide confidence in the achieved results and gain insights into the decision-making process, an explainable artificial intelligence analysis based on two different techniques is carried out. Specifically, we suggest to use saliency maps and an innovative technique based on patch-based input feature ablations that we design for this purpose. We show that the proposed methodology is solid, consistent and without biases that may distort the results and lead to long-term inconsistent behavior. Thus, we guarantee that the models will detect and react appropriately to the occurrence of any type of unknown situation, being able to manage uncertainty. The combination of techniques developed in the work have been successfully deployed and are currently undergoing validation in a real industrial production environment. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first work to propose and validate the development of an AI-managed safety channel that improves upon, and can be combined with, the capabilities offered by traditional functional safety measures, which represents a significant breakthrough in the efficiency, reliability, and safety of modern industrial processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.-I., F.B., and B.S.; methodology, J.F.-I., and B.S.; software, J.F.-I.; validation, J.F.-I., F.B., and B.S.; formal analysis, J.F.-I.; investigation,J.F.-I., and B.S.; resources, J.F.-I., F.B., and B.S.; data curation, J.F.-I.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.-I., F.B., and B.S.; writing—review and editing, J.F.-I., F.B., and B.S.; visualization, J.F.-I.; supervision, F.B., and B.S.; project administration, J.F.-I.; funding acquisition, J.F.-I., and F.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J. Fernández-Iglesias. and F. Buitrago acknowledges support from the project “PID2020-116188GA-I00”, funded by “MICIU/AEI /10.13039/501100011033”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study, as well as the training scripts, are not publicly available due the fact that they constitute an excerpt of research in progress but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge WIP by Lear and Lear Corporation for collaboration in the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEC |

Architecture, engineering, and construction |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ANSI |

American National Standards Institute |

| AUC |

Area under curve |

| BGMM |

Bayesian Gaussian mixture model |

| CL |

Contrastive learning |

| DL |

Deep learning |

| EHSRs |

Essential health and 46 safety requirements |

| EM |

Expectation- Maximization |

| FPS |