1. Introduction

Cancer pain is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms across all types of cancer, significantly reducing patients’ quality of life [

1]. Moreover, managing cancer-related pain can often be challenging [

2]. For example, many patients with advanced disease struggle to attend frequent clinic visits due to their limited ability to perform daily activities or because of unmanageable pain and other symptoms [

3]. In this complex situation, telehealth interventions can help bridge this gap by improving access to care and maintaining ongoing pain management [

4]. Notably, recent evidence shows that telemedicine-based programs can lead to a reduction in pain intensity and pain interference with daily life compared to usual in-person care [

5]. These findings highlight the feasibility of remote care options and the effectiveness and acceptability of these strategies as key components of cancer pain management.

However, implementing and optimizing telemedicine-based pain care pathways pose several challenges that must be addressed. Given the need for a personalized care process, cancer pain management often requires multidisciplinary input and flexible adjustment of therapy [

6]. Therefore, scheduling a care pathway that includes both clinic visits and remote assessments is often complex. Key issues include identifying suitable assessment tools for remote pain evaluation, implementing reliable symptom monitoring devices, and determining when additional interventions or in-person exams are necessary [

7].

Therefore, there is an urgent need to establish calibrated, dynamic protocols that strike the right balance between telehealth and in-person visits. These protocols are necessary for timely clinical assessments, additional diagnostic tests, or procedures. In the absence of comprehensive guidelines or large-scale trials in this field, developing such a structured telemedicine pathway depends on early experiences and expert consensus. While a hybrid care model that combines remote visits with on-site hospital care was demonstrated to be an effective and safe strategy for managing cancer pain, precise refinement of this process is essential [

8]. It should incorporate patient feedback and outcomes [

9]. For example, a telehealth-based pain management program in Italy combined virtual consultations with traditional clinic visits, resulting in positive outcomes regarding patient adherence and pain control. This initial experience demonstrated that a hybrid telemedicine approach can deliver high-quality care while reaching patients who live up to 500 km away from the cancer center [

8,

9,

10].

On these premises, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) can be used to analyze multiple patient-related variables, such as demographic, clinical, and therapeutic metadata, to predict which patients will require more intensive follow-up and, ultimately, identify those likely to need additional remote consultations or earlier in-person visits [

11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Ethics

The study population included adult patients treated for cancer pain at the Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Fondazione Pascale, Napoli, Italy, and at the Ruggi University Hospital, Salerno, Italy.

The local Medical Ethics Committees approved this study (protocol code 41/20 Oss; date of approval, 26 November 2020; Ethical Committee Campania 2, N°2024/28590, 3 April 2025), and all patients provided written informed consent. The investigation was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Datasets

Two cohorts of cancer patients, cohort 1 recorded during 2021 and cohort 2 in 2023/2025, were considered in the analysis. A single operator (Marco Cascella) performed the televisits for both cohorts. The same technology and processes (platform, devices, privacy policy) were adopted.

The date of any single televisit was recorded. The included variables were age, sex, tumor site, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, presence of metastasis, bone metastasis, pain (breakthrough cancer pain, BTCP, no BTCP), type of pain (nociceptive, neuropathic/mixed), and rapid opioid onset (ROO) therapy (no, yes). The time-varying variables, such as ECOG, BTCP, pain type, and ROO therapy, were considered at the first televisit, according to the former dataset. Continuous measurements were shown as mean (standard deviation, SD) and median (interquartile range, IQR), while categorical measures were synthesized with absolute frequencies (percentages). Repositories are available at [

12,

13].

2.3. Dataset Harmonization and Preprocessing

This initial step involved adapting two datasets. For cohort 2, time-varying information about variables was collected and had to be aligned with the format of the cohort 1 dataset. Specifically, after transposing data into a wide format, we only considered information on age, sex, ECOG, (bone) metastasis, BTCP pain, pain type, and ROO therapy at the first televisit. Data on tumor sites and the presence of metastasis were also available, but they were excluded from the analysis due to the small number of observations and their strong correlation with other features.

The final data included 280 cancer patients from cohort 1 (n = 226) and cohort 2 (n = 54). Since 10 observations containing missing values were removed, a total of 270 complete observations were considered for the subsequent analysis.

The number of televisits was recorded in discrete values and categorized into one televisit or more televisits. One-hot encoding was applied to categorical variables, while age, the only continuous measure, was standardized based on the values in the training set.

2.4. ML Framework

2.4.1. ML Algorithms

Our analysis aimed to classify observations with one or more televisits. To showcase the full methods pipeline and ensure reproducibility, we outlined our framework following guidelines for the recommended use of supervised ML models [

14,

15]. Five ML algorithms and a multiple logistic regressor (LR) as a reference model were used for this analysis. Specifically, the random forest (RF) and the gradient boosting machine (GBM) are tree-based methods consisting of multiple decision trees (DTs), which individually process the input data and collectively produce the final output. RF is based on the bagging (bootstrap aggregating) method to build pseudo-uncorrelated trees that focus on different feature subsets as predictors for the outcome. This results in a stable algorithm capable of handling many covariates. An RF can be configured by hyperparameters, including the number of trees (ntree), the number of random features (mtry) per tree, and the minimum number of observations in a terminal node (node size). The boosting learner is an alternative approach applied to the sequential construction of DTs in the GBM ensemble method. After creating an initial DT, the prediction error is gradually reduced by subsequent trees. The growth of these trees is regulated by the number of trees, terminal node size, and the shrink (learning rate) parameter. The support vector machine (SVM) aims to find the best hyperplane that separates observations. This hyperplane maximizes the distance between the hyperplane and the nearest data points from both classes. The optimal hyperplane, known as a hard margin, maximizes these margins. When nonlinear relationships exist between the outcome and features, the probabilistic shape of the data is used to transform the input. We implemented kernel density using a radial basis function (RBF) kernel, a common approach in SVM classification tasks. Other hyperparameters include gamma, which relates to the RBF kernel, and the cost parameter (c or cost), which penalizes the model for misclassifications within the margins. Higher values enforce stricter separation. These parameters are usually tuned within known value ranges [

16]. The k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm is widely used for classification, where a new data point is classified based on the majority class among its k closest neighbors. The hyperparameter k must be specified before running the algorithm. The multilayer perceptron (MLP) is a type of artificial neural network composed of interconnected layers of neurons. Each neuron acts as a switch that transforms its input via an activation function and outputs a signal if a threshold is met. The neurons are organized in layers, with hidden layers in between the input and output layers. Each layer receives input from the previous layer, computes its output based on weights, and passes it forward. The final layer produces the network’s output. Backpropagation involves iteratively passing the output backward through the network to adjust and optimize the weights, which control the strength of signal transmission. This enhances the network’s predictive ability but also increases computational demands. We used the hyperbolic tangent as the activation function, as it proved more stable when handling outliers [

17]. The network was built with one or two hidden layers (HLs). The first could vary from 1 to 5 neurons, and the second was set equal to the first. The learning rate determines how quickly weights are updated during training in a backpropagation process.

2.4.2. Data Splitting, Explorative Analysis, and ML Models Training and Selection

Data was split into a 75/25% training/test, balanced on the combination of the number of televisits and cohort. An explorative univariate nalysis consisted of detecting statistical differences across cohorts and showing crude associations between the number of televisits (One, More televisits) with the other variables. Tests included Pearson’s chi-squared test for independence and Fisher’s exact test. The Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to deal with multiple tests.

Five ML methods (RF, GBM, SVM, KNN, MLP) were implemented together with the reference LR model. The training was performed by an R-repeated K-fold cross-validation method. In particular, for each ML algorithm, we adopted R = 7 and K = 5: for a single combination of hyperparameters, the training set was split into 5 parts: 4 (n = 165) used for training each algorithm, and the last (n = 39) to validate the algorithm. A seed based on K and R was applied to allow the reproducibility of splitting. Observations were randomly given to the training or test set, balancing the proportion of the number of televisits together with the cohort. The algorithms characterized by the corresponding hyperparameters linked to the best performance were chosen.

Performances were calculated via the F1-score metric. The selected models were re-run on the whole train set (n = 204) and internally tested and compared with each other on the F1-score, Accuracy, and AUC-ROC measures calculated on the test set (n = 66). The Delong test [

18] was adopted to detect pair-wise differences in terms of prediction performances, according to the AUC score.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify potential changes in the performance of algorithms. Specifically, all ML pipelines were rerun under two scenarios: a) we applied class weights to the models based on the proportion of televisits and cohort membership; b) we removed the cohort variable from the feature set, resulting in an unbalanced dataset while keeping the same training and test set structure used in the main analysis. In scenario a), the function used to implement the MLP did not allow for direct input of class weights. Therefore, an oversampling procedure was designed to achieve a similar effect.

All tests and estimates were presented at the 95% confidence level. The analyses were implemented using the R software for statistical analysis, version 4.3.2, and the following packages were included: dplyr for data manipulation, gtsummary for data presentation, caret for the performance metrics computation, randomForest, gbm, e1071, class, neuralnet for algorithm implementation, purrr and pROC for AUC-ROC analysis, and ggplot to draw the figures. The workflow is available at [

19].

3. Results

Demographic and clinical data were collected into two separate datasets. The two cohorts include 226 individuals from cohort 1 and 54 from cohort 2. The characteristics of the sample are described in

Table 1. Mean age was 64.5 years (±12.4), half were males, the most prevalent tumor site was gastrointestinal (20.7%), followed by breast (12.9%). Most patients suffered from metastatic disease (90%), whereas half of them had bone metastasis. Almost 40% suffered from BTCP, while a similar prevalence was observed in neuropathic or mixed pain. Sixty percent of the sample underwent ROO therapy. The median number of televisits was 1 (IQR: 1, 3), with 143 patients having 1 televisit and 9% having more than four (see

Table 2, in the middle). When analyzing the difference between cohorts (not shown in tables), cohort 2 had a significantly higher ECOG than cohort 1 (p = 0.02), reported a higher prevalence of bone metastases (70.4% vs 45.1%, p < 0.01), and suffered from nociceptive pain more than cohort 1 (78.8 vs 59.1, p = 0.01).

Nevertheless, no differences in the number of televisits were observed by cohort (p > 0.90). When analyzing our main outcome (

Table 1), no significant association were found between the number of televisits with the available set of features, even if an indication of relationship was visible for sex, where requiring more televisits was more prevalent among males than females (55.6% vs 44.8%, p = 0.07), and for type of pain: in particular patients undergoing more televisits had a more prevalent neuropathic or both pain compared to the one who underwent only one televisit (p = 0.09).

3.1. ML Modelling

Table 2 summarizes the hyperparameter grids and computational time required to optimize each ML algorithm using the 7-repeated 5-fold cross-validation procedure. For each model, a range of key hyperparameters was explored to identify the configuration providing the best validation performance.

The RF and GBM models were tuned by varying the number of trees (ntree = 20–100), node size (9–17), and the number of features randomly sampled at each split (mtry = 3–6 for RF) or the shrinkage rate (shrink = 0.001–0.1 for GBM). The SVM was optimized over exponential grids of gamma (2^−15 to 2^3) and cost (2^−5 to 2^15). For the KNN algorithm, k varied from 2 to 5. The MLP network was tuned through combinations of learning rates (0.001–0.19, step 0.02) and the number of neurons in the first (HL1 = 1–5) and second hidden layers (HL2 < HL1). The LR model used a logit link as a reference.

In terms of computational cost, ensemble, and kernel-based methods (GBM = 3.39 min; SVM = 3.60 min; RF = 0.86 min) showed moderate training times, while the neural network (MLP) required substantially longer optimization (≈ 231 min). Simpler algorithms, such as KNN and LR, trained almost instantaneously.

The optimal hyperparameters and linked F1-scores on the test set with accuracy and AUC-ROC scores are shown in

Table 3. Each model was retrained using the best configuration obtained from the 7-repeated 5-fold cross-validation and then tested on unseen data (n = 66).

Among ensemble methods, the RF achieved an F1-score of 0.43 and an accuracy of 0.49 (95% CI: 0.36–0.61), while the GBM performed similarly (F1 = 0.42; AUC = 0.42). The SVM with γ = 2 and cost = 0.125 showed a moderate improvement (F1 = 0.55; accuracy = 0.55; AUC = 0.55). The KNN algorithm with k = 3 produced comparable results (F1 = 0.45; accuracy = 0.48; AUC = 0.45).

Notably, the MLP, optimized with a learning rate of 0.05 and two hidden layers (HL1 = 4, HL2 = 3), achieved the highest discrimination capacity (F1 = 0.65; AUC = 0.65), although with relatively lower accuracy (0.48) due to class imbalance. Finally, the LR model yielded intermediate performance (F1 = 0.47; accuracy = 0.52; AUC = 0.47), confirming its role as a stable but less flexible baseline classifier.

Despite the differences in mean values, no statistically significant difference among models was detected (DeLong test, p > 0.05), indicating comparable predictive capacities under the same data conditions.

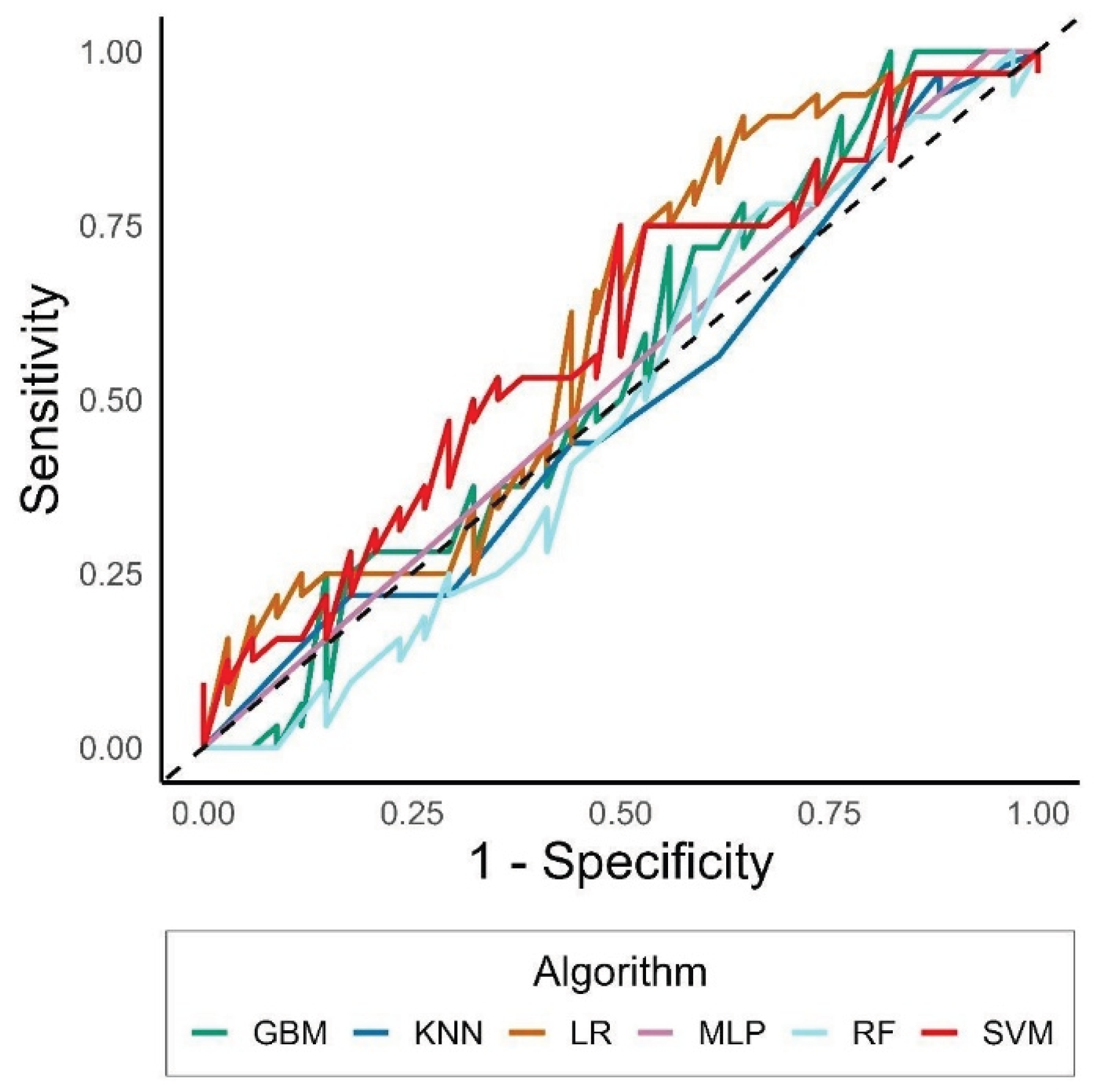

Comparisons across AUCs reported values from 0.43 (RF) to 0.65 (LR) (

Figure 1). GBM was particularly unable to detect observations correctly, leading to an accuracy < 0.5, and to a statistically significantly worse AUC than SVM and LR (p-value from the Delong test = 0.04 and 0.03, respectively).

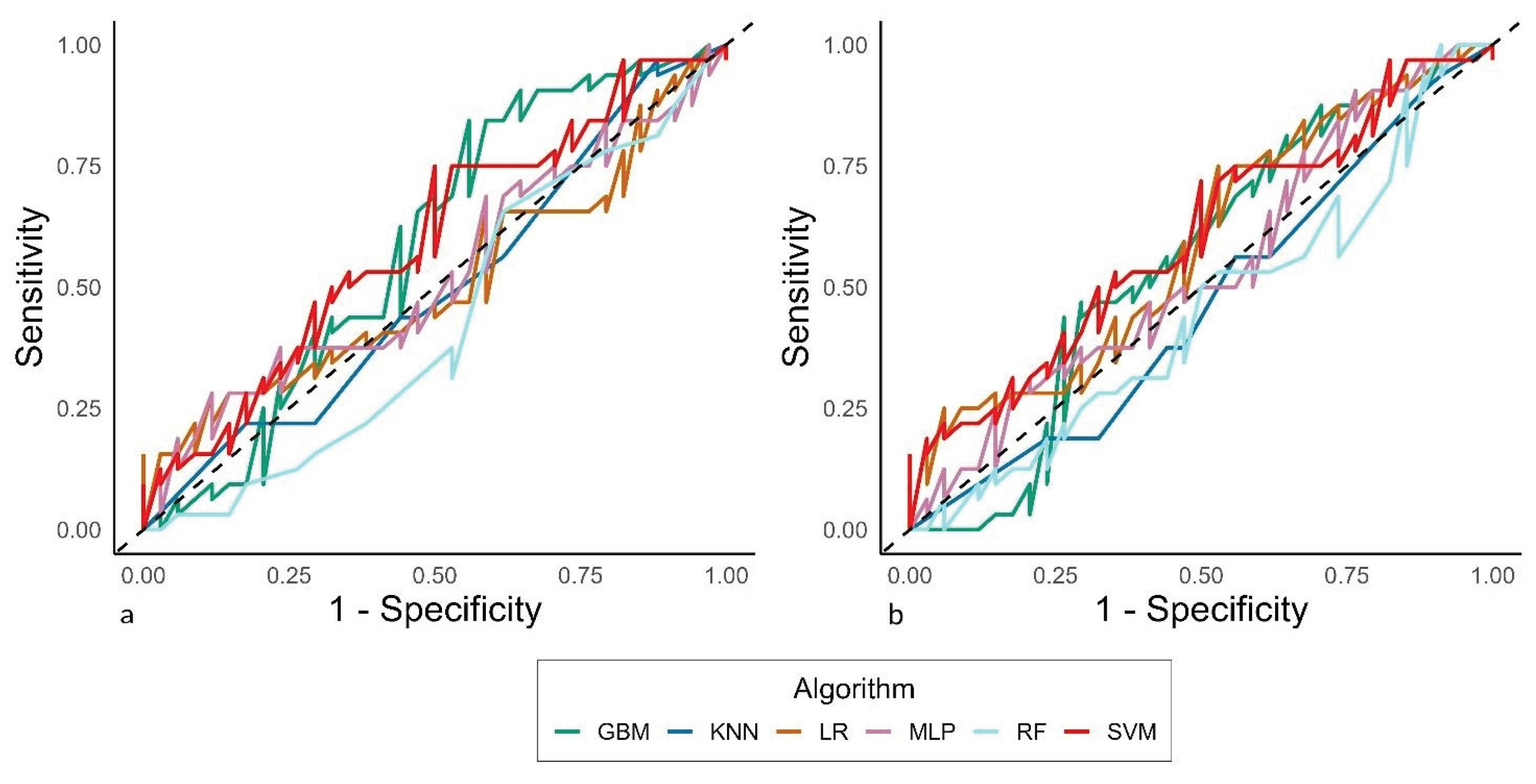

The sensitivity analysis did not detect particular differences in the classification behaviors across models, even if an additional time was needed to train the MLP (6.8 hours), due to the oversampling routine that was applied when tackling the sub-analysis on the class weight, where they were given as follows: One televisit and cohort 1: n = 81, weight = 1.02; one televisit and cohort 2: n = 24, weight = 3.46; more televisits and cohort 1: n = 83, weight = 1.0; more televisits and cohort 2: n = 16, weight = 5.19. In contrast, the computational time was reduced by about one hour when the analysis was performed without considering the cohort among the features.

Figure 2 reports the AUC-ROCs from these additional analyses.

4. Discussion

Although telemedicine represents a suitable opportunity for care delivery, clinical practice indicates that scheduling and balancing in-person and telehealth-based consultations is often challenging [

7,

10,

20]. In the complex context of cancer pain management, ML-driven predictions can enable clinicians to tailor care interventions and allocate resources.

In our previous ML investigation, we found that models identified specific factors that increased the likelihood of requiring multiple teleconsultations. These factors included younger patient age (<55 years), certain cancer types (e.g., lung cancer), and the occurrence of BTCP episodes. The analysis also suggested that elderly patients (>75 years) with advanced disease and bone metastases might benefit from closer telemedicine monitoring [

21]. In this study, which focused on using ML models to predict the need for additional visits, despite implementing rigorous validation procedures, model performance remained modest across all tested algorithms. Probably, these results reflect intrinsic limitations of the dataset rather than methodological flaws.

A first critical issue relates to the risk of underfitting. In ML contexts, underfitting occurs when algorithms fail to learn sufficient patterns from the data, producing models that perform similarly to random classification [

22]. This is a common problem in small and homogeneous datasets, especially when the outcome variable exhibits class imbalance or low variability [

23]. Specifically, the dataset included a limited number of predictors, most of which were categorical and derived from baseline assessments. Consequently, the limited feature complexity may have affected the models’ ability to capture nonlinear relationships and hidden interactions among variables. Nevertheless, the simplicity of the dataset and the small number of clinically meaningful predictors likely reduced the capacity of the algorithms to generalize. This is a key issue as cancer pain is influenced by multifactorial dynamics, including psychological, pharmacologic, and social variables, and probably they were not fully captured in this analysis [

24]. Therefore, expanding future datasets to include pivotal information such as patient-reported outcomes, analgesic adjustments, as well as clinical input obtained from wearable sensor data and digital technology tools [

25], could substantially enhance predictive modeling.

The presence of two distinct cohorts may have introduced heterogeneity that impaired model learning. Statistically significant differences were observed in ECOG performance status, pain type, and prevalence of bone metastases. These inter-cohort disparities may represent background differences not directly associated with the outcome (number of televisits), thereby acting as noise that limits pattern recognition. Similar findings have been described in ML studies using heterogeneous clinical populations, where variations in data source or clinical practice reduce algorithmic stability. They represent crucial gaps for AI deployment into clinical practice [

26]. Andersen et al. [

27], for instance, discussed how variations in clinical data sources and operational settings can compromise the stability of AI and ML models, thereby requiring continuous monitoring practices and model updating strategies. However, the inclusion of a comprehensive sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the models across different training conditions. Techniques for handling class imbalance, such as class-weight adjustment or oversampling of minority classes, have been extensively documented in the literature to mitigate bias due to class or cohort imbalance [

28,

29,

30]. In our analysis, given the application of class-weight adjustments and testing the exclusion of the cohort variable, potential sources of bias related to class imbalance and cohort heterogeneity were effectively mitigated. Therefore, model performance remained stable and was not driven by data distribution artifacts.

From a methodological perspective, other strengths could be highlighted. For example, the application of a repeated k-fold cross-validation scheme (7×5) represents a robust internal validation strategy, consistent with international guidelines such as the data, optimization, model and evaluation (DOME) approach [

14], and the multidisciplinary recommendations for developing ML models in biomedicine [

15]. Moreover, the integration of multiple algorithms (tree-based, kernel-based, and neural models) within the same pipeline provides a comparative view of how different learning paradigms behave in a low-dimensional telemedicine dataset.

Additionally, another potential strength is the translational applicability of the proposed framework. Given the availability of larger and more granular datasets, ML-based care processes can be directly applied to predict high-frequency teleconsultations, optimize clinician workload, and tailor follow-up [

31]. According to key objectives in modern telehealth oncology practice, these tools could assist healthcare providers in proactively identifying patients who might benefit from closer remote monitoring or careful in-person evaluations [

5]. Therefore, on these premises, future studies should aim to integrate temporal and textual features (e.g., free-text notes, symptom trajectory), to evaluate model calibration and explainability using techniques such as SHAP or LIME [

32], and to perform external validation on independent cohorts. Addressing these aspects will increase generalizability and clinical trustworthiness, aligning with emerging AI quality standards and the European AI Act framework [

33].

5. Conclusions

Despite limitations, this ML analysis confirms the feasibility of applying predictive analytics to telemedicine data for cancer pain management. Importantly, results highlight the importance of dataset quality, feature richness, and cohort homogeneity in developing reliable predictive models. Future research should expand data sources and exploit more sophisticated architectures to strengthen the integration of AI into personalized telehealth care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C., M.C. and A.C.; methodology, S.C., M.S. and F.S.; software, M.A.I., D.E. and V.C.; validation, A.O., M.P.B. and R.D.F.; formal analysis, M.S., S.C. and A.O.; investigation, D.E., V.C. and A.C.; resources, R.D.F., M.P.B. and F.S.; data curation, M.A.I., D.E. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C., A.O. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C., M.P.B. and F.S.; visualization, V.C., R.D.F. and M.A.I.; supervision, M.C., F.S. and A.O.; project administration, M.C., A.C. and R.D.F.; funding acquisition, M.C., A.O. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The local Medical Ethics Committees approved this study (protocol code 41/20 Oss; date of approval, 26 November 2020; Ethical Committee Campania 2, N°2024/28590, 3 April 2025), and all patients provided written informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.C., upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Snijders RAH, Brom L, Theunissen M, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(3):591. [CrossRef]

- Carbonara L, Casale G, De Marinis MG, Bosetti C, Valle A, Carinci P, D’andrea MR, Corli O. Adherence to ESMO guidelines on cancer pain management and their applicability to specialist palliative care centers: An observational, prospective, and multicenter study. Pain Pract. 2024 Oct 3. [CrossRef]

- van Roij J, Brom L, Youssef-El Soud M, van de Poll-Franse L, Raijmakers NJH. Social consequences of advanced cancer in patients and their informal caregivers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(4):1187-1195. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Huang J, Cui Z, Wang L, Dong L, Ying W, Zhang Y. The efficacy of telemedicine for pain management in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2023 Feb 17;14:20406223231153097. [CrossRef]

- Buonanno P, Marra A, Iacovazzo C, Franco M, De Simone S. Telemedicine in Cancer Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Med. 2023;24(3):226-233. [CrossRef]

- Porzio G, Capela A, Giusti R, Lo Bianco F, Moro M, Ravoni G, Zułtak-Baczkowska K. Multidisciplinary approach, continuous care and opioid management in cancer pain: case series and review of the literature. Drugs Context. 2023;12:2022-11-7. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Marinangeli F, Vittori A, Scala C, Piccinini M, Braga A, Miceli L, Vellucci R. Open Issues and Practical Suggestions for Telemedicine in Chronic Pain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23):12416. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Schiavo D, Grizzuti M, Romano MC, Coluccia S, Bimonte S, Cuomo A. Implementation of a Hybrid Care Model for Telemedicine-based Cancer Pain Management at the Cancer Center of Naples, Italy: A Cohort Study. In Vivo. 2023;37(1):385-392. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Coluccia S, Grizzuti M, Romano MC, Esposito G, Crispo A, Cuomo A. Satisfaction with Telemedicine for Cancer Pain Management: A Model of Care and Cross-Sectional Patient Satisfaction Study. Curr Oncol. 2022 Aug 4;29(8):5566-5578. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Innamorato MA, Natoli S, Bellini V, Piazza O, Pedone R, Giarratano A, Marinangeli F, Miceli L, Bignami EG, Vittori A. Opportunities and barriers for telemedicine in pain management: insights from a SIAARTI survey among Italian pain physicians. J Anesth Analg Crit Care. 2024 Sep 17;4(1):64. [CrossRef]

- Li YH, Li YL, Wei MY, Li GY. Innovation and challenges of artificial intelligence technology in personalized healthcare. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):18994. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M. PainDatafor_Telemedicine_ML [Data set] Zenodo. 2022 . [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M. (2025). Telemedicine_Cancer_Pain_RUGGI [Data set]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Walsh I, Fishman D, Garcia-Gasulla D, Titma T, Pollastri G; ELIXIR Machine Learning Focus Group; Harrow J, Psomopoulos FE, Tosatto SCE. DOME: recommendations for supervised machine learning validation in biology. Nat Methods. 2021;18(10):1122-1127. Erratum in: Nat Methods. 2021;18(11):1409-1410. [CrossRef]

- Luo W, Phung D, Tran T, Gupta S, Rana S, Karmakar C, Shilton A, Yearwood J, Dimitrova N, Ho TB, Venkatesh S, Berk M. Guidelines for Developing and Reporting Machine Learning Predictive Models in Biomedical Research: A Multidisciplinary View. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(12):e323. [CrossRef]

- Hsu C, Chang C, Lin C. A Practical Guide to Support Vector Classification. 2003. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:2443126.

- Cuevas FG, Schmid H. Robust Non-linear Normalization of Heterogeneous Feature Distributions with Adaptive Tanh-Estimators. Proceedings of The 27th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. In: Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 2024;238:406-414 Available from https://proceedings.mlr.press/v238/guimera-cuevas24a.html.

- DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44, 837–845.

- Coluccia, S. (2025). Telemedicine_ML_Workflow. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Wyte-Lake T, Cohen DJ, Williams S, Bailey SR. Balancing Access, Well-Being, and Collaboration When Considering Hybrid Care Delivery Models in Primary Care Practices with Team-Based Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2025 Sep 15;38(3):475-489. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Coluccia S, Monaco F, Schiavo D, Nocerino D, Grizzuti M, Romano MC, Cuomo A. Different Machine Learning Approaches for Implementing Telehealth-Based Cancer Pain Management Strategies. J Clin Med. 2022;11(18):5484. [CrossRef]

- Nazha A, Elemento O, McWeeney S, Miles M, Haferlach T. How I read an article that uses machine learning methods. Blood Adv. 2023;7(16):4550-4554. [CrossRef]

- Chicco D, Jurman G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Bennett MI, Kaasa S, Barke A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede RD; IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic cancer-related pain. Pain. 2019 Jan;160(1):38-44. [CrossRef]

- Goncalves Leite Rocco P, Reategui-Rivera CM, Finkelstein J. Telemedicine Applications for Cancer Rehabilitation: Scoping Review. JMIR Cancer. 2024;10:e56969. [CrossRef]

- Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):195. [CrossRef]

- Andersen ES, Birk-Korch JB, Hansen RS, Fly LH, Röttger R, Arcani DMC, Brasen CL, Brandslund I, Madsen JS. Monitoring performance of clinical artificial intelligence in health care: a scoping review. JBI Evid Synth. 2024;22(12):2423-2446. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Yang K, Yu Z. et al. A survey on imbalanced learning: latest research, applications and future directions. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57:137. [CrossRef]

- Gurcan F, Soylu A. Learning from Imbalanced Data: Integration of Advanced Resampling Techniques and Machine Learning Models for Enhanced Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(19):3417. [CrossRef]

- Araf I, Idri A, Chairi I. Cost-sensitive learning for imbalanced medical data: a review. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57: 80. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou SC. Machine Learning Models and Technologies for Evidence-Based Telehealth and Smart Care: A Review. BioMedInformatics. 2024; 4(1):754-779. [CrossRef]

- Contreras J, Winterfeld A, Popp J, Bocklitz T. Spectral Zones-Based SHAP/LIME: Enhancing Interpretability in Spectral Deep Learning Models Through Grouped Feature Analysis. Anal Chem. 2024 Oct 1;96(39):15588-15597. [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on Artificial Intelligence (AI Act). Available from: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/the-act/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).