1. Introduction

Two large observational studies looked at the relationship between aluminum adjuvants from vaccines and future asthma diagnosis. Daley et al. “Association Between Aluminum Exposure From Vaccines Before Age 24 Months and Persistent Asthma at Age 24 to 59 Months.” [

1] found a positive association between aluminum adjuvants and asthma with a hazard ratio of 1.19 per mg of aluminum from vaccines (95% CI 1.14, 1.25). while Andersson et al. “Aluminum-Adsorbed Vaccines and Chronic Diseases in Childhood : A Nationwide Cohort Study.” [

2] found a negative association with a hazard ratio of .96 per mg of aluminum from vaccines (95% CI .94, .98). These are both statistically significant results, but in opposite directions. This study will show how a potential uncorrected nonlinearity in dose response violates the proportional hazards assumption and can lead to arbitrarily large errors in HR estimates.

2. Materials and Methods

This study, done at the CDC VSD, is a reanalysis of Daley et al. “Association Between Aluminum Exposure From Vaccines Before Age 24 Months and Persistent Asthma at Age 24 to 59 Months.” [

1], using the same population and methodology, with extra steps to test for potential nonlinearity of aluminum dose-response either as a function of dose in mg/Kg, or as a function of the age of the child receiving the vaccine. To determine this, the overall 2 year exposure window was divided into 6 smaller exposure windows for the non eczema cohort, centered on dose timings (0-1m), (1-3m), (3-5m), (5-7m), (7-15m), (15-23m). A separate Cox proportional hazards model was done for each exposure period for the same population. As in the Daley study, the dose received in the sub exposure window is not adjusted by the dose of aluminum prior to the exposure window, nor after the exposure window, nor aluminum received through diet. If the aluminum dose-response is linear, it should be possible to recover the Daley et al. result for the total exposure window to within the margin of error from each of the smaller exposure windows. For this type of study, we are comparing the same population repeatedly, without attempting to reinterpret the effect size, therefore the static covariates used in the original study are not needed. This leads to an unadjusted HR that differs from the original, but is not important for the purposes of determining if linearity assumptions in dose-response or proportional hazards assumptions in the later regression were justified. The important result is whether or not the sub window HR’s are statistically different from the overall relationship. The critical question is if it is justified to sum aluminum doses received at different ages or whether aluminum dose-response violates the proportional hazards assumption inherent in choosing to sum aluminum doses. If there is a significant underlying non linearity in dose-response, the hazard ratios computed from the smaller exposure windows will in general lie outside the confidence interval, some above and some below. The specific criteria is whether there exists any sub window where the |adjusted t-test| > 2.

3. Results

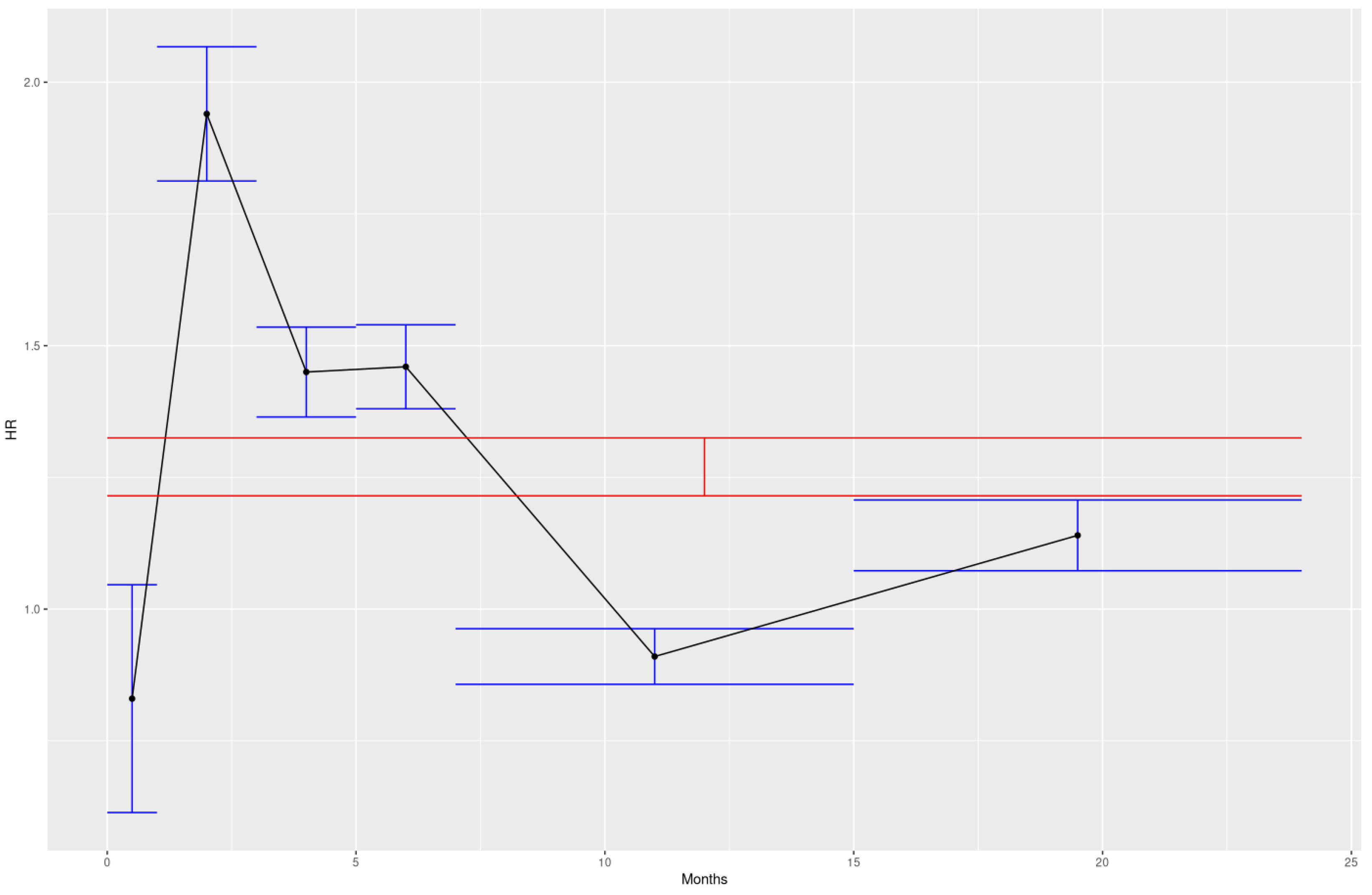

Evidence of nonlinearity by age of exposure was found, while nonlinearity by dose was a null result for the range of doses involved. The two sample t test results in the right column show that all of the hazard ratios from the sub exposure windows were statistically different from the overall 2 year exposure hazard ratio when the exposure windows are chosen to be centered around the major doses received by children. Adjusting the t-test for multiple testing doesn’t change the result.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the total exposure HR in red vs sub window HR in blue

Figure 1.

Visualization of the total exposure HR in red vs sub window HR in blue

Table 1.

Unadjusted cox proportional hazard models overall and by sub exposure window

Table 1.

Unadjusted cox proportional hazard models overall and by sub exposure window

| Age |

HR |

SE Ln(HR) |

CI1

|

t-test2

|

Adjusted t3

|

| 0m-23m |

1.27 |

0.02172 |

1.21, 1.32 |

- |

- |

| 0m-1m |

.83 |

0.1103 |

.67, 1.03 |

-3.75 |

-3.27 |

| 1m-3m |

1.94 |

0.06501 |

1.71, 2.21 |

6.27 |

5.98 |

| 3m-5m |

1.45 |

0.04354 |

1.33, 1.58 |

2.80 |

2.16 |

| 5m-7m |

1.46 |

0.04066 |

1.35, 1.58 |

3.11 |

2.54 |

| 7m-15m |

.91 |

0.02693 |

.87, .96 |

-9.46 |

-9.27 |

| 15m-23m |

1.14 |

0.03424 |

1.06, 1.21 |

-2.68 |

-2.01 |

Not only do none of the sub window HR error bars overlap with the overall HR error bars, but they rarely overlap each other.

It should be noted that these exposure windows were chosen post hoc. The a priori analysis called for 4 - 6 month sub windows (0-5m), (6-11m), (12-17m), and (18-23m) which also were significant to 6.17 sigma by adjusted t-test, but failed to illustrate the features apparent in the first 6 month bucket. The a priori windows were chosen with the expectation that the nonlinearity was most likely as a function of dose in mg/Kg, rather than age, with an expected peak in the 4m-12m range. The post hoc results are presented as the most important for future replication.

4. Discussion

The Cox proportional hazards model [

3] was used in both studies to analyze the relationship between summed aluminum dose and future asthma outcomes. This model is a semi-parametric approach commonly used in survival analysis to estimate the effects of covariates on the hazard rate of an event occurring. The model's hazard function is expressed as h(t | X) = h_0(t) exp(β^T X), where h_0(t) is the unspecified baseline hazard function, (X) represents the covariates, and β are the regression coefficients. This formulation relies on two key assumptions: (1) proportional hazards, meaning the hazard ratio between any two individuals is constant over time and independent of (t); and (2) linearity, meaning the effects of the covariates are linear on the log-hazard scale. Both studies included appropriate tests for linearity of the relationship between asthma and summed aluminum dose, but in both cases there were no tests to verify that summation of aluminum doses did not violate the proportional hazards (PH) assumption.

These data suggest the response to aluminum adjuvants is a non linear function of time thus violating the PH assumption as the baseline hazard ratio now becomes a function of age at exposure. If this is true this means that doses of aluminum received at different ages can’t be summed together without adjusting for the varying response. Otherwise when the summed dose of aluminum is then regressed against any outcome, the result will be dependent on the age at exposure for the subject, mostly determined by each country's vaccination schedule, and the choice of exposure window by the researcher. The potential consequences should be clear from the results above that any hazard ratio in the range of .83 - 1.94 may be found in a study of the relationship between summed aluminum dose and asthma in the presence of an uncorrected nonlinearity. This range does not even bound possible values, as those results are merely an average for a bucket, there are potentially more extreme values that are possible.

In this case dose in mg is being used as a proxy variable for the response to such dose. The response is unknown but assumed to be linear as a function of dose in mg. The proportional hazards assumption is dependent on this linearity of dose-response. There is a need to test for linearity in dose-response before summing doses of aluminum that were different in terms of age administered or in terms of dose in mg/Kg. Summing doses of differing mg/Kg, at least for the ranges seen in childhood vaccination, appears to be justified, but summing doses received at different ages does not appear to be. Such tests should be conducted prior to observational studies until there is sufficient knowledge of the dose-response function from biology. There are known methods of handling the non-linearity of covariates in an extended Cox proportional hazards model [

4] as this problem has been encountered before in oncology. For the purposes of this study, the only goal was to determine if the PH assumption was justified, not reinterpret the effect size by using an extended Cox proportional hazards model.

The differences in the results for Daley et al. and Andersson et al. may be partially explained by the different vaccination schedules sampling a nonlinear function in different domains. This highlights the need for research protocols to explicitly test for such non linearities before conducting an observational study. While this complicates the protocol, now requiring 2 datasets, one for exploration of the dose-response function, and another to study the outcome of interest. The consequences for not doing this extra work can be dire.

Numerically it’s possible to demonstrate the differences in total HR for the median dose of aluminum for the 6 exposures (0-1m, 1-3m, 3-5m, 5-7m, 7-15m, 15-23m) which was respectively (.25mg, .975mg, .975mg, .975mg, .75mg, .375mg) which makes the total HR 3.6. That compares to the Daley et al. methodology, where we can choose to use either sum of sub window medians at 4.3mg or actual total dose median of 4.175mg, which gives HR of 2.79 or 2.71 respectively. While the magnitude of these unadjusted HRs are not important, the ratio of HRs 3.6/2.79 = 1.29 or 3.6/2.71 = 1.33 demonstrates the potential masking of risk that happens when nonlinearity of dose-response is not properly accounted for. There exists no bound for the potential difference in HR estimates in the presence of an uncorrected nonlinearity. The difference is enough to make otherwise significant results insignificant, or even change the sign of a significant result. In the particular case of Daley et al. these results suggest it caused an underestimate of risk.

Andersson et al. studied more than just asthma. If there exists an uncorrected nonlinearity in the dose-response of aluminum as a function of age, it would cause systematic error in all of the reported results.

The biology of what in particular causes such nonlinear features in the dose-response of aluminum is surely complex and due to multiple factors, but it can be speculated that the features at the front end of the curve are possibly mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome via its two-signal process [

5]. Activation of NLRP3 occurs via: Priming (signal 1) which upregulates NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β/pro-IL-18 through NF-κB, often triggered by cytokines like TNF-α or IL-1β. Activation (signal 2) leads to assembly, caspase-1 cleavage, maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, and gasdermin D (GSDMD)-mediated pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death. [

5] This two-signal process potentially explains why the first birth dose of aluminum appears to not have a positive association with asthma, while the second dose received at 2 months appears to have the strongest association with asthma. Aluminum salts are known to activate NLRP3 in both animals and humans [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Furthermore, Cheng et al. found that the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and its downstream products caspase-1 and IL-1β increased in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized asthmatic airway inflammation model mice [

5]. Wood et al. found increased expression of IL-1β and upregulated expression of NLRP3 and NOD-like domain 1 genes in sputum of 127 patients with asthma [

5]. Simpson et al. found elevated expression of NLRP3 in neutrophilic asthma [

10]. In line with those findings, inhibition of NLRP3 is considered a promising avenue of treatment for asthma and several other inflammatory diseases [

11,

12].

It would be interesting to know where the empirical peak of aluminum dose-response would be in a country like Denmark, where exposure occurs at 3 months, 5 months, and 12 months according to their vaccination schedule. Finding a peak of aluminum dose-response at 5 months in Denmark, as opposed to 2 months in the US would be consistent with the hypothesis that NLRP3 priming and activation mediates some of the nonlinear features seen in the aluminum dose-response curve.

5. Conclusions

Aluminum adjuvant responses may vary nonlinearly with child age, which if true would invalidate unadjusted summation of doses across ages in observational studies. This class of error can produce HR estimates varying widely (e.g., 0.83-1.94), potentially explaining discrepancies between Daley et al. and Andersson et al. studies and masking true risks. Future protocols must test for dose-response nonlinearities using exploratory datasets to avoid systematic errors in vaccine safety research.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Solutions IRB (protocol ID 0755 on 7/31/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the use of secondary data.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they are owned by the CDC VSD. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to publicdataset@cdc.gov.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Degrees of freedom intermediate calculation for adjusted t-test in table 1

Table A1.

Degrees of freedom intermediate calculation for adjusted t-test in table 1

| Age |

SE Ln(HR) |

Degrees of Freedom |

| 0m-23m |

0.02172 |

- |

| 0m-1m |

0.1103 |

336821 |

| 1m-3m |

0.06501 |

381545 |

| 3m-5m |

0.04354 |

459130 |

| 5m-7m |

0.04066 |

477592 |

| 7m-15m |

0.02693 |

598396 |

| 15m-23m |

0.03424 |

529141 |

References

- Daley, M.F.; Reifler, L.M.; Glanz, J.M.; Hambidge, S.J.; Getahun, D.; Irving, S.A.; Nordin, J.D.; McClure, D.L.; Klein, N.P.; Jackson, M.L.; et al. Association Between Aluminum Exposure From Vaccines Before Age 24 Months and Persistent Asthma at Age 24 to 59 Months. Acad. Pediatr. 2022, 23, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, N.W.; Svalgaard, I.B.; Hoffmann, S.S.; Hviid, A. Aluminum-Adsorbed Vaccines and Chronic Diseases in Childhood: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1972, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Tsokos, C. A Statistical Model with Non-Linear Effects and Non-Proportional Hazards for Breast Cancer Survival Analysis. Adv. Breast Cancer Res. 2018, 07, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Di, X.; Zhao, M.; Li, H.; Bai, L.; Wang, K. The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammation in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Immunity, Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornung, V.; Bauernfeind, F.; Halle, A.; O Samstad, E.; Kono, H.; Rock, K.L.; A Fitzgerald, K.; Latz, E. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenbarth, S.C.; Colegio, O.R.; O’connor, W.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Flavell, R.A. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature 2008, 453, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Willingham, S.B.; Ting, J.P.-Y.; Re, F. Cutting Edge: Inflammasome Activation by Alum and Alum’s Adjuvant Effect Are Mediated by NLRP3. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, L.; Núñez, G. The Nlrp3 inflammasome is critical for aluminium hydroxide-mediated IL-1β secretion but dispensable for adjuvant activity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38, 2085–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.L.; Phipps, S.; Baines, K.J.; Oreo, K.M.; Gunawardhana, L.; Gibson, P.G. Elevated expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome in neutrophilic asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 43, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, R.C.; Robertson, A.A.B.; Chae, J.J.; Higgins, S.C.; Muñoz-Planillo, R.; Inserra, M.C.; Vetter, I.; Dungan, L.S.; Monks, B.G.; Stutz, A.; et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, A.V.; Park, I.-H.; Park, J.W.; Bae, J.P.; Lee, G.S.; Kang, T.J. NLRP3 Inflammasome as Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Diseases. Biomol. Ther. 2023, 31, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

95% CI = exp(HR +/- 1.96 * SE) |

| 2 |

Welch’s t test: (mean1 - mean2) / √(SE1² + SE2²) |

| 3 |

Bonferroni correction: df = (SE1² + SE2²)² / [(SE1⁴ / (n1 - 1)) + (SE2⁴ / (n2 - 1))]

Adjusted t = qt(pt(unadjusted t, df, lower.tail=FALSE) * 6, df, lower.tail=FALSE)

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).