Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

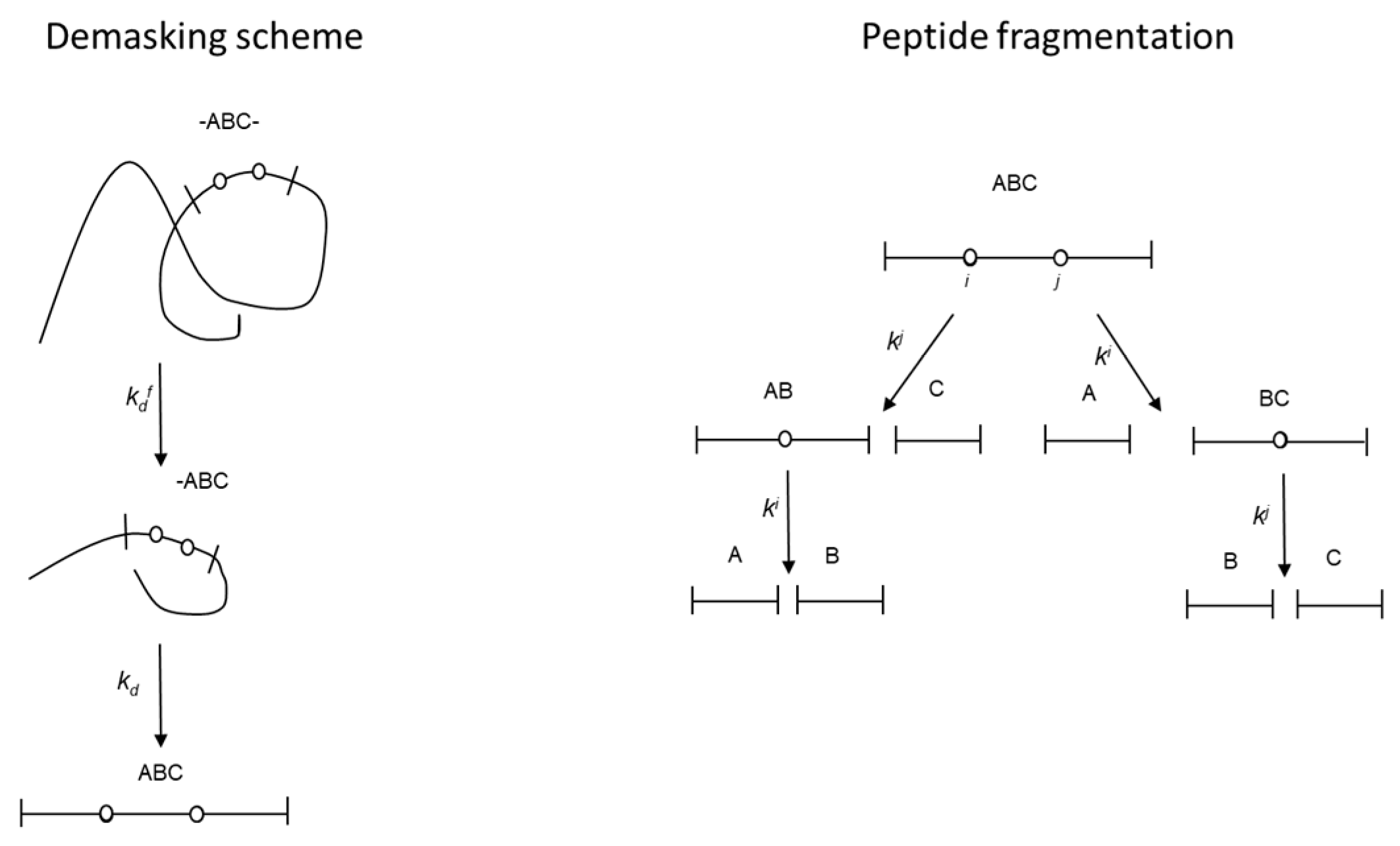

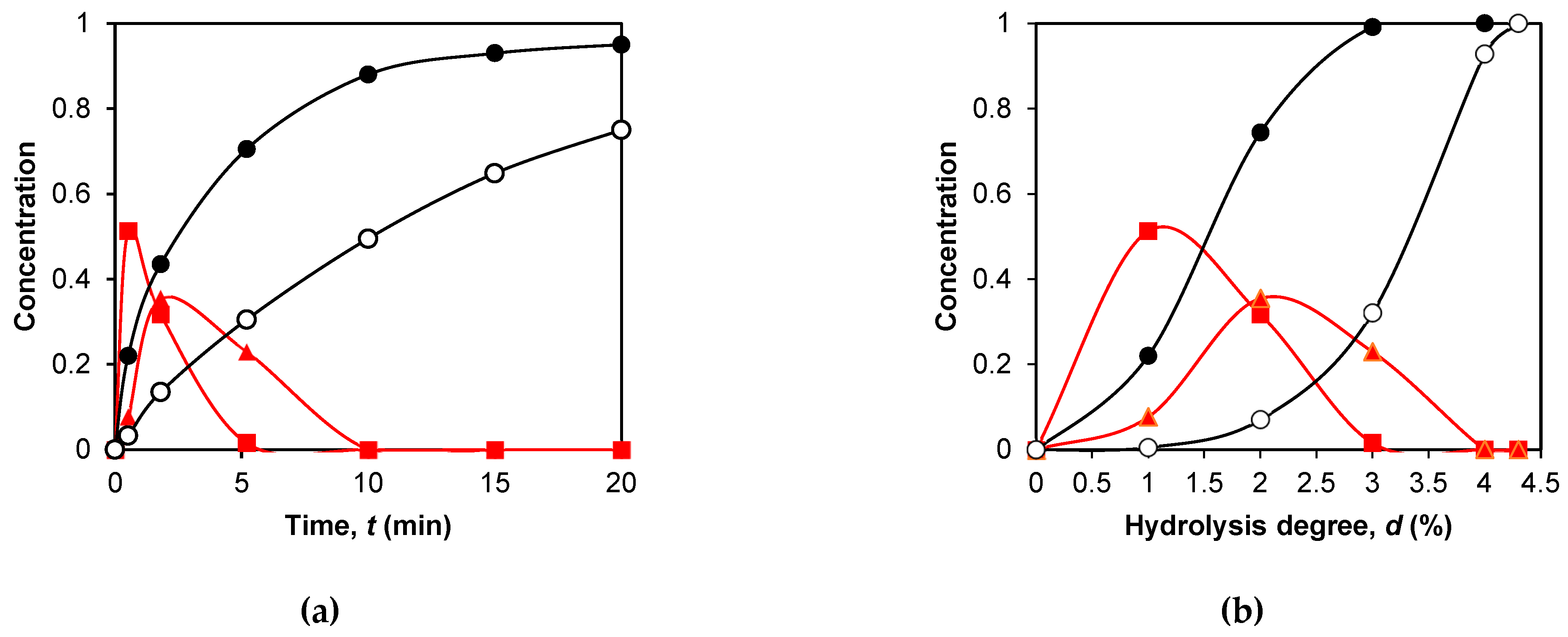

2.1. Proteolysis model

2.2. Application of the fragmentation scheme to the proteolysis of β-CN by trypsin

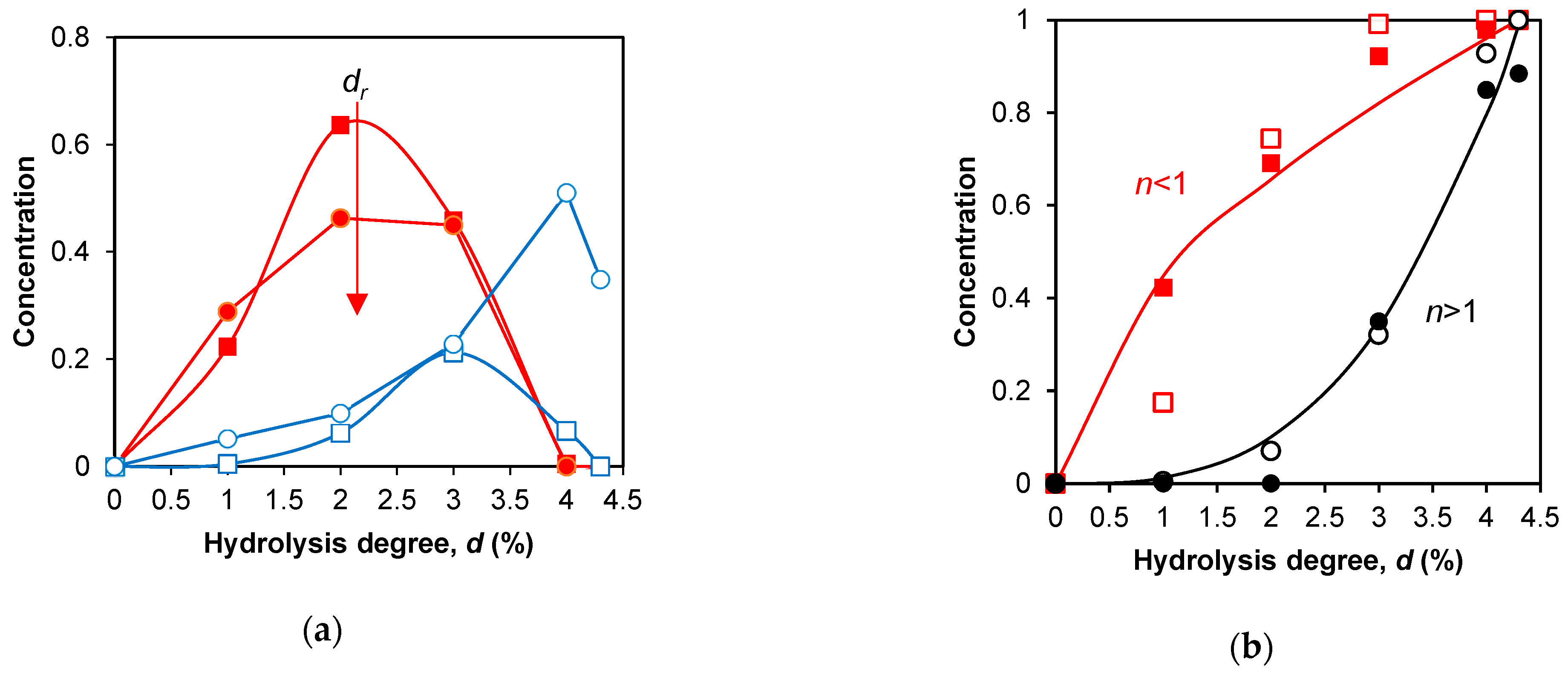

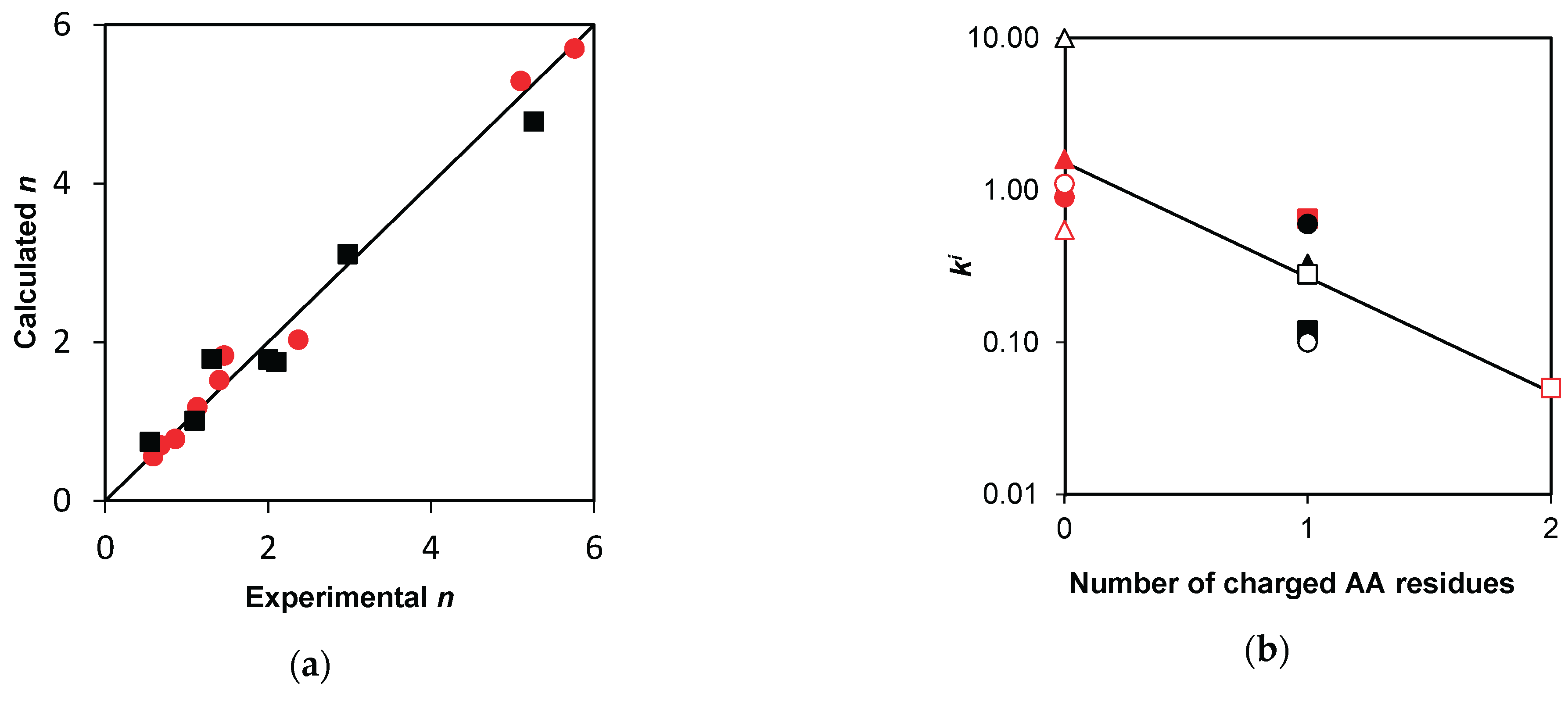

2.3. Estimation of rate constants for demasking and hydrolysis

2.4. Simulation of peptide release during proteolysis by trypsin

2.5. Prospects for in silico proteolysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Quantitative modelling of proteolysis

4.2. Estimation of the rate constants

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vorob’ev, M.M. Towards a quantitative description of proteolysis: Contribution of demasking and hydrolysis steps to proteolysis kinetics of milk proteins. Foods 2025, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linderstrom-Lang, K.U. Lane Medical Lectures. Volume 6, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1952; pp. 53–72.

- Adler-Nissen, J. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Food Proteins; Elsevier Applied Science Publishers: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Vorob’ev, M.M. Kinetics of peptide bond demasking in enzymatic hydrolysis of casein substrates. J. Mol. Catal. B 2009, 58, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Tamayo, R.; De Groot, J.; Wierenga, P.A.; Gruppen, H.; Zwietering, M.H.; Sijtsma, L. Modeling peptide formation during the hydrolysis of β-casein by Lactococcus lactis. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Gruppen, H.; Wierenga, P.A. Comparison of protein hydrolysis catalyzed by bovine, porcine, and human trypsins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 4219–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; van der Veer, F.; Sforza, S.; Gruppen, H.; Wierenga, P.A. Towards predicting protein hydrolysis by bovine trypsin. Process Biochem. 2018, 65, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeb, E.; Stefan, T.; Letzel, T.; Hinrichs, J.; Kulozik, U. Tryptic hydrolysis of b-lactoglobulin: A generic approach to describe the hydrolysis kinetic and release of peptides. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 105, 104666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorob’ev, M.M. Modeling of the peptide release during proteolysis of β-lactoglobulin by trypsin with consideration of peptide bond demasking. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Riera, F. b-Lactoglobulin tryptic digestion: A model approach for peptide release. Biochem. Eng. J. 2013, 70, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaubier, S.; Framboisier, X.; Fournier, F.; Galet, O.; Kapel, R. A new approach for modelling and optimizing batch enzymatic proteolysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozols, M.; Eckersley, A.; Platt, C.I.; Stewart-McGuinness, C.; Hibbert, S.A.; Revote, J.; Li, F.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Watson, R.E.B.; Song, J.; et al. Predicting proteolysis in complex proteomes using deep learning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorob’ev, M.M.; Vogel, V.; Güler, G.; Mäntele, W. Monitoring of demasking of peptide bonds during proteolysis by analysis of the apparent spectral shift of intrinsic protein fluorescence. Food Biophys. 2011, 6, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorob’ev, M.M. Modeling of proteolysis of β-lactoglobulin and β-casein by trypsin with consideration of secondary masking of intermediate polypeptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, A.; de Laureto, P.P.; Spolaore, B.; Frare, E.; Picotti, P.; Zambonin, M. Probing protein structure by limited proteolysis, Acta Biochimica Polonica 2004, 51, 299–321. [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, S.J. The structural aspects of limited proteolysis of native proteins, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1382, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorob’ev, M.M. Proteolysis of β-lactoglobulin by trypsin: Simulation by two-step model and experimental verification by intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Symmetry 2019, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, H.M.; Jimenez-Flores, R.; Bleck, G.T.; Brown, E.M.; Butler, J.E.; Creamer, L.K.; Hicks, C.L.; Hollar, C.M.; Ng-Kwai-Hang, O.F.; Swaisgood, T.H.E. Nomenclature of the proteins of cows’ milk, 6th rev. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1641–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambling, S.G.; McAlpine, A.S.; Sawyer, L. β-Lactoglobulin. In: P.F. Fox (Ed.), Adv. Dairy Chem. Proteins, vol. 1, 1992, pp. 141–190, Essex: Elsevier.

- Creamer, L.K.; Parry, D.A.; Malcolm, G.N. Secondary structure of bovine beta-lactoglobulin B. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1983, 227, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, G.R.; Saraiva Macedo Timmers, L.F.; Volken de Souza, C.F. In silico strategies to predict anti-aging features of whey peptides. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024, 66, 2426–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.F.; McSweeney, P.L.H. (Eds.), Advanced dairy chemistry—volume 1: proteins (parts A and B), Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, USA, 2003.

- Grosclaude, F.; Mahé, M.F.; Ribadeaudumas, B. Primary structure of alpha casein and of bovine beta casein Eur. J. Biochem. 1973, 40, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C. Structure and stability of bovine casein micelles. Adv. Protein Chem. 1992, 43, 63–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, A.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Livney, Y.D. Beta-casein nanovehicles for oral delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs, Nanomedicine: NBM 2010, 6, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Decker, E.A.; Park, Y.; Weiss, J. Structural design principles for delivery of bioactive components in nutraceuticals and functional foods, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 577–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongonierma, A.B.; FitzGerald, R.J. Enhancing bioactive peptide release and identification using targeted enzymatic hydrolysis of milk proteins. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 3407–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.D.H.; Liang, N.; Rathish, H.; Kim, B.J.; Lueangsakulthai, J.; Koh, J.; Qu, Y.; Schulz, H.J.; Dallas, D.C. Bioactive milk peptides: an updated comprehensive overview and database, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butre, C.I.; Sforza, S.; Gruppen, H.; Wierenga, P.A. Introducing enzyme selectivity: a quantitative parameter to describe enzymatic protein hydrolysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 5827–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butré, C.I. Introducing enzyme selectivity as a quantitative parameter to describe the effects of substrate concentration on protein hydrolysis. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, 2014. ISBN 978-94-6257-023-8.

- Butre, C.I.; Sforza, S.; Wierenga, P.A.; Gruppen, H. Determination of the influence of the pH of hydrolysis on enzyme selectivity of Bacillus licheniformis protease towards whey protein isolate. Int. Dairy J. 2015, 44, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turalić, A.; Hegedüs, Z.; Altieri, F.; Martinek, T.A.; Đeđibegović, J. Discordance between in silico and in vitro results on proteolytic stability of milk protein-derived DPP-4 inhibitory peptides. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 3199–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, H.L.R.; Peralta, J.P.; Tejano, L.A.; Chang, Y.-W. In silico and in vitro assessment of Portuguese Oyster (Crassostrea angulata) proteins as precursor of bioactive peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero-Pino, F.; Idowu, C.; Malfroy, H.; Rueda, D.; Lester, H. In silico analyses as a tool for regulatory assessment of protein digestibility: Where are we? Computational Toxicology 2025, 35, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorob'ev, M.M.; Açıkgöz, B.D.; Güler, G.; Golovanov, A.V.; Sinitsyna, O.V. Proteolysis of micellar β-casein by trypsin: secondary structure characterization and kinetic modeling at different enzyme concentrations. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2023, 24, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheison, S.C.; Leeb, E.; Letzel, T.; Kulozik, U. Influence of buffer type and concentration on the peptide composition of trypsin hydrolysates of β-lactoglobulin. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Burgos, D.; Regnier, F.E. Disparities between immobilized enzyme and solution based digestion of transferrin with trypsin. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melikishvili, S.; Dizon, M.; Hianik, T. Application of high-resolution ultrasonic spectroscopy for real-time monitoring of trypsin activity in β-casein solution. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorob'ev, M.M.; Sinitsyna, O.V. Degradation and assembly of β-casein micelles during proteolysis by trypsin. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 104, 104652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chobert, J.-M.; Briand, L.; Tran, V.; Haertle, T. How the substitution of K188 of trypsin binding site by aromatic amino acids can influence the processing of b-casein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 246, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeke, G.J.C.; Vincken, J.-P.; Wierenga, P.A. The path of proteolysis by bovine chymotrypsin. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamone, G.; Picariello, G.; Caira, S.; Addeo, F. , Ferranti, P. Analysis of food proteins and peptides by mass spectrometry-based techniques. J. Chrom. A 2009, 1216, 7130–7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeke, G.J.C.; Lubbers, W.; Vincken, J.-P.; Wierenga, P.A. A method to identify and quantify the complete peptide composition in protein hydrolysates. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1201, 339616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butré, C.I.; Buhler, S.; Sforza, S.; Gruppen, H.; Wierenga, P.A. Spontaneous, non-enzymatic breakdown of peptides during enzymatic protein hydrolysis, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics 2015, 1854, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vreeke, G.J.C.; Vincken, J.-P.; Wierenga, P.A. Quantitative peptide release kinetics to describe the effect of pH on pepsin preference. Proc. Biochem. 2023, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckin, V.; Altas, M.C. Ultrasonic monitoring of biocatalysis in solutions and complex dispersions. Catalysts 2017, 7, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizon, M.; Buckin, V. Ultrasonic monitoring of enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins. 1. Effects of ionization. Food Hydrocol. 2023, 144, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizon, M.; Buckin, V. Ultrasonic monitoring of enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins. 2. Relaxation effects. Food Hydrocol. 2025, 158, 110221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopade, P.A. Computational characteristics of kinetic models for in vitro protein digestion: A review. J. Food Eng. 2024, 360, 111690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Feunteun, S.; et al. Mathematical modelling of food hydrolysis during in vitro digestion: From single nutrient to complex foods in static and dynamic conditions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margot, A.; Flaschel, E.; Renken, A. Empirical kinetic models for tryptic whey-protein hydrolysis. Process Biochem. 1997, 32, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Araiza, G.; Castano-Tostado, E.; Amaya-Llano, S.L.; Regalado-Gonzalez, C.; Martinez-Vera, C.; Ozimek, L. Modeling of enzymatic hydrolysis of whey proteins. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 2596–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, P.; Pinto, M.; Almonacid, S. Identification of the key mechanisms involved in the hydrolysis of fish protein by Alcalase. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, P.; Espinoza, K.; Astudillo-Castro, C.; Salazar, F. Modeling tool for studying the influence of operating conditions on the enzymatic hydrolysis of milk proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaubier, S.; Framboisier, X.; Fournier, F.; Galet, O.; Kapel, R. A new approach for modelling and optimizing batch enzymatic proteolysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bond index i | Cleavage site1 | Selectivity2 (%) | Initial hydrolysis rate2 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bonds | Most slowly hydrolyzed bonds | Peptide fragments in trimer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R-EI | 0 | 0 | + |

1-28/29, 30-97, 98-99 |

|

| 25 | TR-IN | 0.7 | 0 | + | ||

| 28/29 | NK-KI/KK-IE | 8.2/0.9 | 0.1 | |||

| 32 | EK-FQ | 0.7 | 0 | + | ||

| 48 | DK-IH | 0.02 | 0 | + | ||

| 97 | EK-TK | 0.6 | 0.1 | |||

| 99 | VK-EA | 15.3 | 0.8 | + | ||

| 105 | PK-HK | 23.4 | 0.8 | + | 106-107, 108-113, 114-169 | |

| 107 | HK-EM | 2.7 | 0.3 | |||

| 113 | PK-YP | 1.0 | 0.05 | |||

| 169 | SK-VL | 32.4 | 1 | + | ||

| 176 | QK-AV | 11.4 | 0.6 | 170-176, 177-183, 184-209 | ||

| 183 | QR-DM | 2.8 | 0.2 | |||

| 202 | VR-GP | 0.2 | 0 | + |

| Substrate | Bond index i | kd2 | ki3 |

3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28/29 | 3.5 | 5 | 0.6±0.2 | 70±3 | |

| 97 | 3.5 | 5 | 0.3±0.1 | 32±2 | |

| 99 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| 105 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| β-CN | 107 | 3.5 | 1 | 0.10±0.01 | 19±1 |

| 113 | 3.5 | 1 | 0.10±0.01 | 75±3 | |

| 169 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| 176 | 3.5 | 1 | 10±1 | 78±5 | |

| 183 | 3.5 | 1 | 0.3±0.1 | 80±8 | |

| ________________________________________________________________________________ | |||||

| 8 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| 14 | 0.46 | >>1 | 0.9±0.2 | 93±7 | |

| 40 | 0.46 | >>1 | 1.6±0.4 | 102±5 | |

| 69/70 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| β-LG1 | 75 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | |||

| 83 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.6±0.1 | 115±8 | |

| 91 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 1.1±0.3 | 96±3 | |

| 100/101 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| 124 | 0.46 | 1.1 | 0.55±0,14 | 80±6 | |

| 135 | 0.46 | 1.1 | 0.05±0.01 | 19±1 | |

| 138 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| 141 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| 148 | Most rapidly hydrolyzed bond | ||||

| Substrate | Peptide | Type of fragment | Calculated dr (%)1 | Experimental dr (%)1 | Calculated n2 | Experimental n2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f(1-99), ABC | Intermediate | 1.41 | 1.00 | ||||

| f(1-97), AB | Intermediate | 2.04 | 1.77 | ||||

| f(30-99), BC | Intermediate | 2.23 | 2.28 | ||||

| f(106-169), ABC | Intermediate | 2,18 | 2.14 | ||||

| f(106-113), AB | Intermediate | 2.98 | 3.61 | ||||

| f(108-169), BC | Intermediate | 2.98 | 1.96 | ||||

| f(170-209), ABC | Intermediate | 1.32 | 1.33 | ||||

| f(170-183), AB | Intermediate | 1.40 | 1.48 | ||||

| f(177-209), BC | Intermediate | 2.14 | 1.61 | ||||

| f(1-28/29), A | Final | 1.01 | 1.10 | ||||

| β-CN | f(30-97), B | Final | 1.75 | 2.10 | |||

| f(98-99), C | Final | 1.42 | -3 | ||||

| f(106-107), A | Final | 3.11 | -3 | ||||

| f(108-113), B | Final | 4.78 | 5.26 | ||||

| f(114-169), C | Final | 3.11 | 2.98 | ||||

| f(170-176), A | Final | 0.74 | 0.55 | ||||

| f(177-183), B | Final | 1.79 | 1.31 | ||||

| f(184-209), C | Final | 1.78 | 2.00 | ||||

| ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |||||||

| f(9-69/70), ABC | Intermediate | 2.45 | 1.503 | ||||

| f(9-40), AB | Intermediate | 2.90 | 3.60 | ||||

| f(15-69/70), BC | Intermediate | 2.65 | -3 | ||||

| f(76-100/101) ABC | Intermediate | 3.62 | 3.40 | ||||

| f(76-91), AB | Intermediate | 4.29 | 4.40 | ||||

| f(84-100/101), BC | Intermediate | 4.06 | 4.70 | ||||

| β-LG | f(101/102-138), ABC | Intermediate | 3.41 | 3.40 | |||

| f(101/102-135), AB | Intermediate | 4.20 | -3 | ||||

| f(125-138), BC | Intermediate | 4.85 | 6.10 | ||||

| f(9-14), A | Final | 0.70 | 0.68 | ||||

| f(15-40), B | Final | 0.78 | 0.86 | ||||

| f(41-69/70), C | Final | 0.56 | 0.59 | ||||

| f(76-83), A | Final | 1.83 | 1.46 | ||||

| f(84-91), B | Final | 2.03 | 2.37 | ||||

| f(92-100/101), C | Final | 1.52 | 1.40 | ||||

| f(101/102-124), A | Final | 1.18 | 1.13 | ||||

| f(125-135), B | Final | 5.70 | 5.76 | ||||

| f(136-138), C | Final | 5.29 | 5.10 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).