3. Results

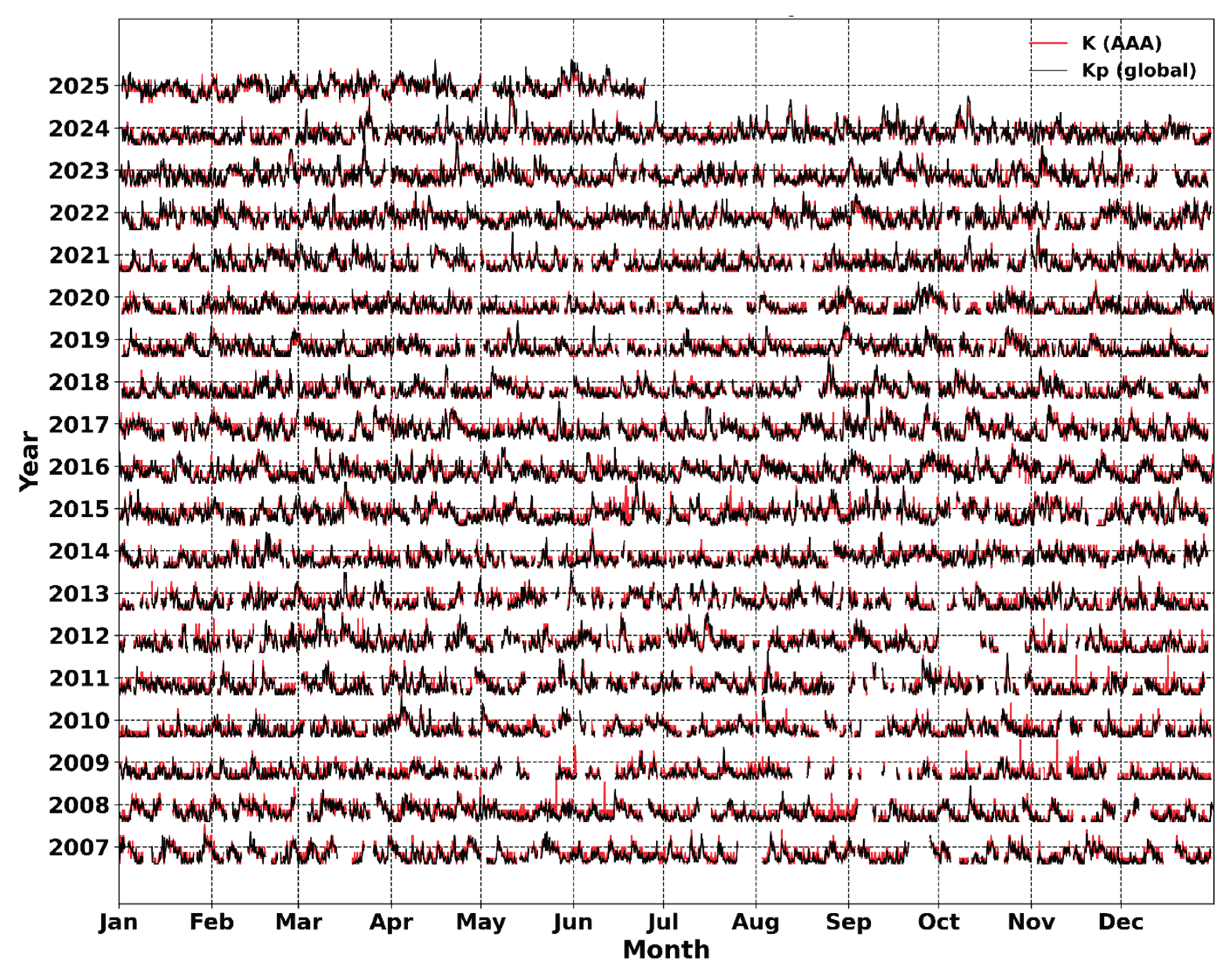

A comparison of the three-hour values of the local K (AAA) and global Kp indices revealed a high degree of coherence between the two time series. As shown in

Figure 1, both indices exhibit clear synchronization during periods of enhanced geomagnetic activity; however, the local index displays larger amplitude fluctuations and pronounced diurnal variations. In contrast, the global Kp index demonstrates a smoother behavior, reflecting the averaging of data from a distributed network of magnetic observatories.

This discrepancy between K and Kp emphasizes that local measurements are more sensitive to small-scale processes and can capture disturbances not evident in global indices. The overall similarity in their dynamics during magnetic storms confirms that regional magnetospheric responses are in phase with global solar–terrestrial processes. Nevertheless, differences in the amplitude and structural patterns of variations indicate that the local K index serves as a complementary diagnostic parameter, providing valuable insight into the spatial inhomogeneity of the magnetospheric response.

To identify diurnal and seasonal patterns in local and global manifestations of geomagnetic activity, heat maps of the median values of the K (Almaty Observatory, AAA) and Kp indices were constructed in the coordinates “day of year—hour (UTC)”. As shown in

Figure 2, both indices exhibit pronounced spatial–temporal inhomogeneity, reflecting the combined influence of seasonal effects and diurnal variations in magnetospheric disturbances.

For the local K index, a distinct dependence on local time is evident: maxima of median values occur in the 18–23 UTC interval, corresponding to evening and nighttime hours in Kazakhstan. This structure is consistent with the typical ionospheric dynamics, in which variations in conductivity and current systems are most intense in the evening magnetospheric sector. In contrast, the global Kp index exhibits a smoother and more uniform distribution, reflecting averaging across all latitude zones. Nonetheless, seasonal shifts in intensity are also visible, particularly near the equinoxes, confirming the presence of the Russell–McPherron effect [

25,

26], which enhances the coupling between the interplanetary magnetic field and the magnetosphere during these periods.

A comparison of the maps reveals that the local K index demonstrates greater contrast and sensitivity to regional disturbance features, whereas the global Kp index is more inertial, representing the integrated global level of geomagnetic activity. Thus, local observations are capable of capturing small-scale processes and short-term variations that tend to be smoothed out in the formation of global indices.

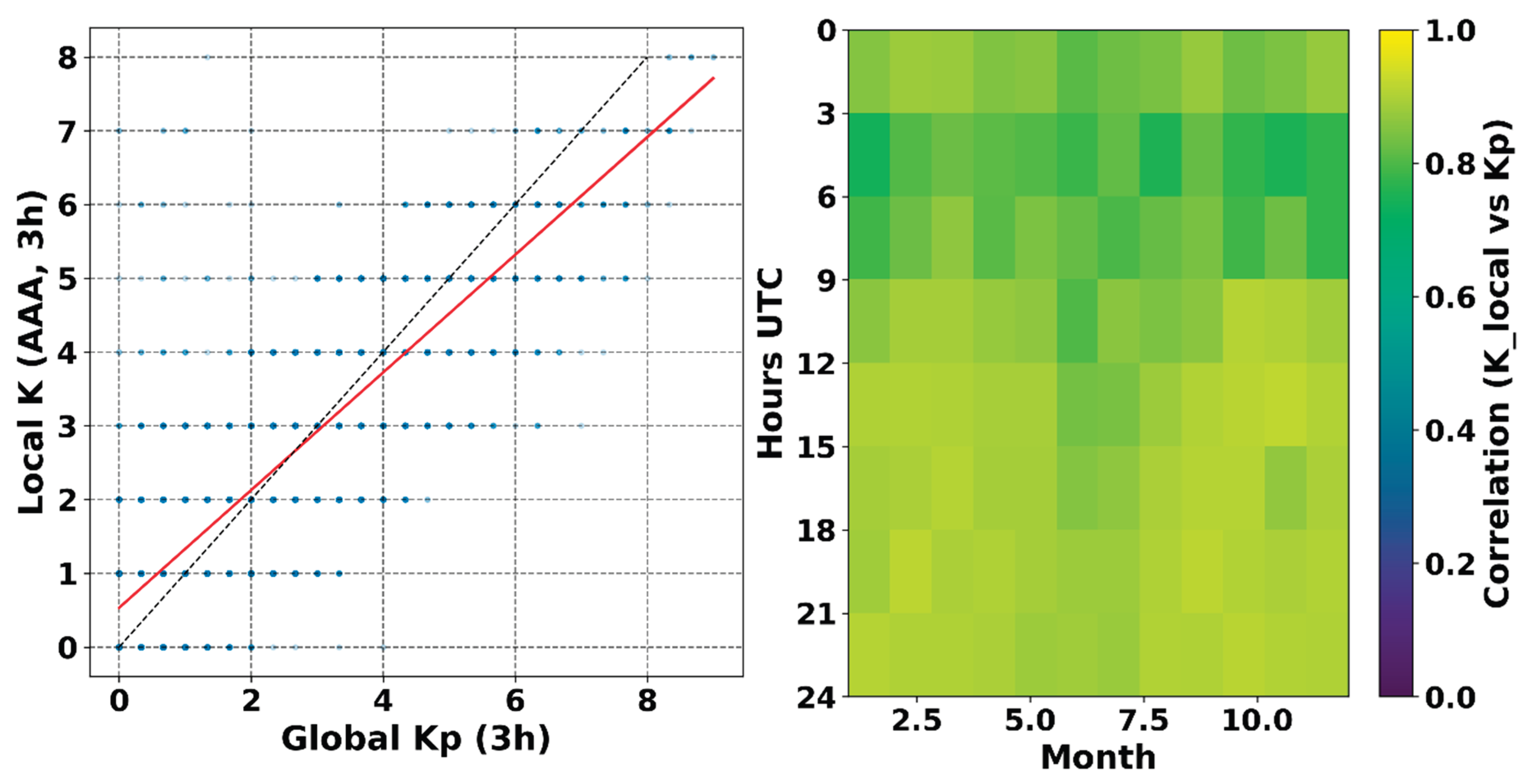

Figure 3a presents a scatter plot comparing the local geomagnetic activity index K (AAA station) and the global Kp index, calculated for three-hour intervals over the entire observation period. Each point represents the correspondence between local and global levels of geomagnetic activity, while the red line indicates the linear regression fit. A clear positive correlation between K and Kp (correlation coefficient r ≈ 0.84) is observed, indicating a strong overall consistency between regional and global magnetospheric processes.

At the same time, the local K values exhibit a larger spread around the regression line, particularly within the range of moderate disturbances (Kp = 2–5). This dispersion reflects the influence of local factors, such as ionospheric current systems, the electrojet, and the geomagnetic latitude of the station, which modify the intensity of local magnetic field variations.

The high degree of correlation, coupled with persistent local deviations, confirms the complex, multiscale nature of magnetospheric processes, where global drivers interact with regional electrodynamic responses.

Figure 3b shows a two-dimensional correlation map between the local geomagnetic index K (AAA station) and the global Kp index in the coordinates “month × hour (UTC)”. The color scale represents the Pearson correlation coefficient between the two indices, averaged over the entire observation period (2007–2025).

The highest correlation values (r ≈ 0.8–0.9) are observed during the evening and nighttime hours (18:00–03:00 UTC), when the geomagnetic field at the station is most sensitive to variations in magnetospheric current systems, particularly during substorm activity. In contrast, the correlation weakens slightly during daytime hours (06:00–12:00 UTC), reflecting the influence of local ionospheric currents driven by solar heating and conductivity variations.

This diurnal modulation of correlation indicates the coexistence of global magnetospheric drivers and regional ionospheric responses, emphasizing the importance of local observations for resolving the temporal and spatial structure of geomagnetic activity.

The scatter plot confirms a linear relationship between the magnitudes of the indices while preserving a notable degree of dispersion, particularly in the region of moderate geomagnetic activity. This indicates that global and local magnetic field variations are driven by the same disturbance sources, yet the amplitude of local fluctuations strongly depends on regional current systems and the geomagnetic latitude of the observatory.

The correlation map refines this relationship, revealing a systematic diurnal and seasonal modulation of coherence between the indices. The highest correlation values (r > 0.8) occur during the evening and nighttime hours, when local magnetic field variations are most in phase with global magnetospheric processes. During the daytime, the correlation weakens slightly due to the influence of ionospheric currents and solar heating–driven diurnal effects.

Seasonal variations are moderate but become more pronounced around the equinoxes, consistent with the Russell–McPherron effect, which enhances the coupling between the interplanetary magnetic field and the magnetosphere during these periods.

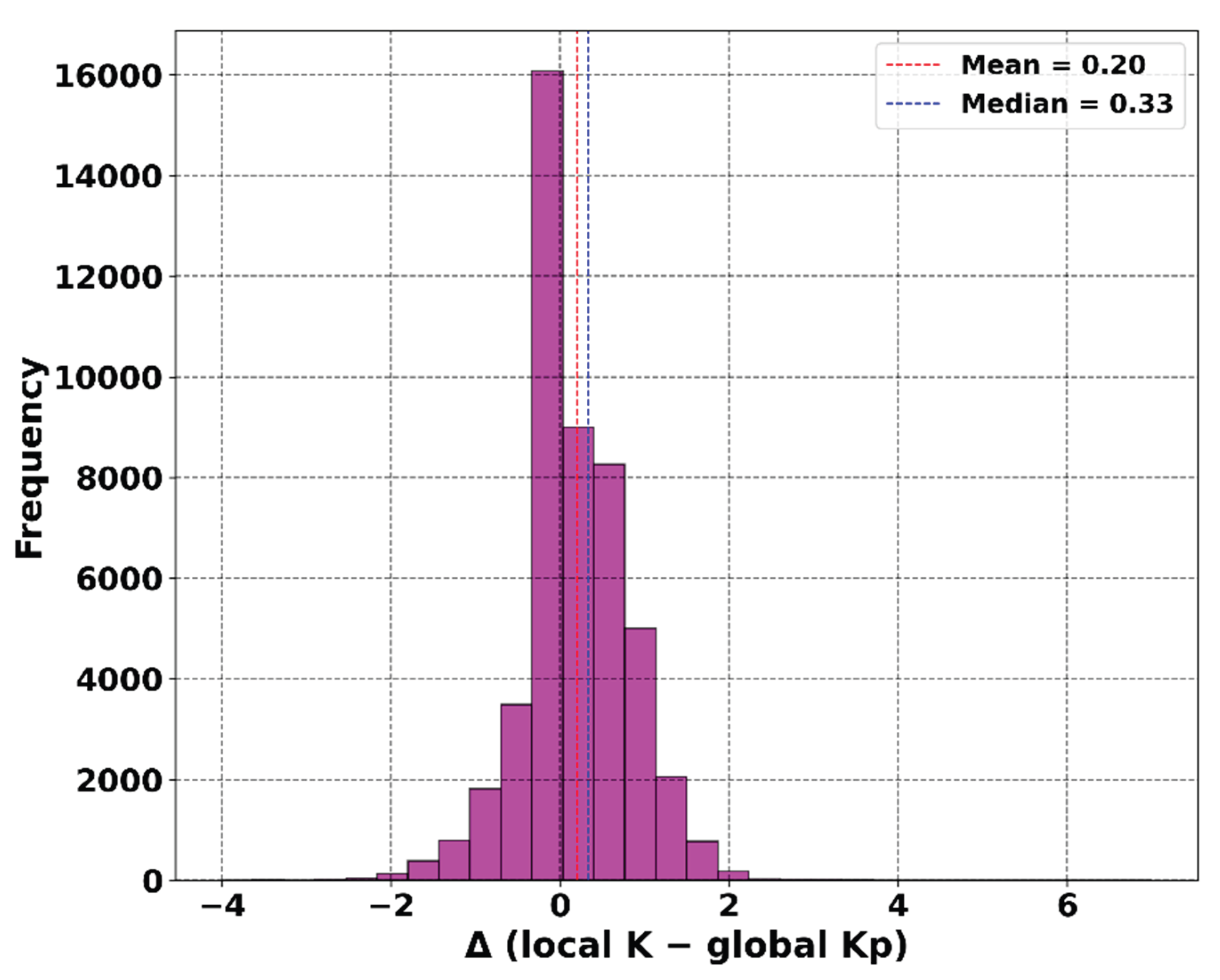

To quantitatively assess the discrepancies, the distribution of differences was calculated as Δ = K − Kp (

Figure 4). The mean difference was +0.20, the median +0.33, and the standard deviation approximately 0.69. These results indicate that the local K index systematically exceeds the global Kp index, while the spread of values reflects the presence of additional regional variations.

Thus, there is a consistent positive bias of the local index relative to the global one, suggesting that the AAA observatory records geomagnetic disturbances that, on average, are stronger than those represented by the globally averaged Kp. This bias highlights the enhanced regional sensitivity of the Almaty station to local magnetospheric–ionospheric processes.

To examine the temporal structure of the discrepancies, the dependence of the offset Δ = K − Kp on month and time of day was analyzed (

Figure 5a). It was found that during the nighttime hours (01:30–04:30 UTC), the local index tends to be lower than Kp, particularly in the winter season (Δ ≈ −0.3 to −0.4). In contrast, during the daytime interval (07:30–16:30 UTC), a persistent positive anomaly is observed (Δ up to +0.6 in summer), indicating an enhanced sensitivity of the Almaty observatory to disturbances in the dayside magnetospheric sector.

In the evening hours (around 19:30 UTC), the local index also frequently exceeds the global value, while the differences tend to diminish toward midnight. This asymmetry corresponds to variations in ionospheric conductivity and daytime electrodynamic response, consistent with the Russell–McPherron effect, which governs the seasonal modulation of solar wind–magnetosphere coupling.

An additional analysis of the frequency of cases where the local index K exceeds the global Kp (

Figure 5b) confirmed the previously identified patterns. During daytime hours, the probability of K > Kp reaches 60–80%, with a maximum in summer. At night, this probability decreases to 20–30%, while during the transitional seasons (spring and autumn), the contrast between day and night is particularly pronounced.

To evaluate the ability of the local K index to reproduce global magnetic storms, defined by Kp ≥ 6, an event coincidence analysis was performed. In this case, an interval was classified as a “magnetic storm.” Based on the three-hour data, a confusion matrix was constructed to represent the matches and mismatches between the local and global indices (

Figure 6):

True Positive (TP)—storms detected by both Kp and K: 109 cases;

False Negative (FN)—storms identified by Kp but not detected at AAA: 112 cases;

False Positive (FP)—local events with K ≥ 6 while Kp remained below the threshold: 122 cases;

True Negative (TN)—absence of storms in both datasets: 47,781 cases.

Thus, in the vast majority of intervals, the indices show strong agreement, while individual discrepancies reflect the regional specificity of the geomagnetic field response.

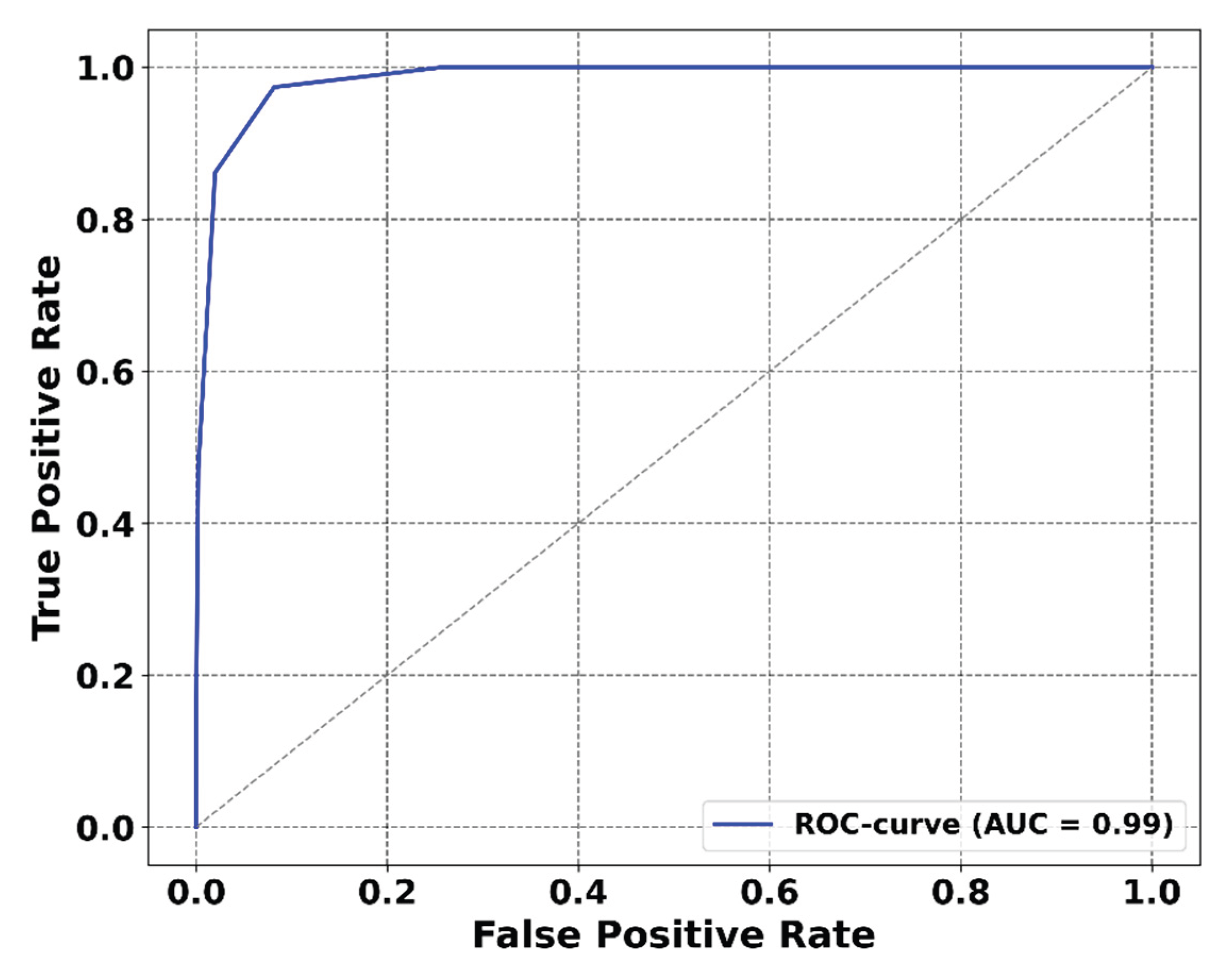

For a more detailed assessment, a ROC curve was constructed using the local K index as a classifier of geomagnetic storms relative to the global Kp index (

Figure 7). The resulting AUC value of 0.99 indicates an almost perfect agreement between the two datasets.

The AAA observatory demonstrates a high reliability in detecting extreme geomagnetic disturbances. However, in some instances, it registers local enhancements that are not reflected in the global Kp index (false positives, FP), while in other cases it misses individual global storm events (false negatives, FN). These discrepancies are likely associated with regional characteristics of the geomagnetic response, influenced by the specific longitude and latitude of the observatory and the local configuration of ionospheric current systems.

To identify the dominant periodicities in the dynamics of geomagnetic activity, a spectral analysis of the time series of the local K index (AAA) and the global Kp index was performed. Calculations were carried out using the Welch method with periodogram averaging, which reduced the variance of the PSD estimates.

A comparison of the spectra (

Figure 8) showed that both indices exhibit similar spectral characteristics, reflecting the common physical origin of geomagnetic field disturbances. The most persistent spectral peaks correspond to the following periodicities:

~27 days—the solar rotation period, determining the recurrence of large-scale solar wind disturbances;

~13–14 days—a subharmonic of solar rotation, associated with the asymmetry of solar wind streams within the heliospheric structure;

7–9 days—oscillations reflecting the dynamics of recurrent interplanetary disturbances.

At the same time, the spectrum of the local K index (AAA) contains more pronounced high-frequency variations (periods <10 days), indicating the sensitivity of local observations to regional features of the magnetosphere–ionosphere response. The Kp spectrum, in contrast, exhibits a smoother power distribution, particularly at shorter timescales, which results from the spatial averaging across a global network of observatories.

To analyze the temporal evolution of periodicities, a wavelet decomposition of the K and Kp time series was performed using the complex Morlet wavelet.

Figure 9a and

Figure 9b show the wavelet scalograms of the local geomagnetic index K (AAA) and the global Kp index, obtained via the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) with a Morlet basis. The color scale represents the normalized wavelet power, which characterizes the relative energy of oscillations as a function of period (vertical axis) and time (horizontal axis).

Both indices exhibit a clearly defined multiscale temporal structure. The power maxima occur at periods between 5 and 30 days, corresponding to the characteristic timescales of magnetospheric disturbances associated with the solar rotation period and recurrent solar wind streams. However, the amplitude of energy contributions and the temporal stability of these components differ significantly between the local and global indices, reflecting differences in their sensitivity to regional versus planetary-scale processes.

In the scalogram of the local K index, short-period components dominate—ranging from 3 to 20 days—appearing as alternating bands of enhanced power. These variations reflect the influence of local current systems and Sq-type ionospheric currents, which form under the combined effects of diurnal and seasonal changes in atmospheric conductivity.

Frequent energy bursts with periods around 27 days correspond to solar rotation, reflecting the recurrence of Earth’s interaction with long-lived solar wind structures. The enhancement of power in the 15–30 day range is especially pronounced during solar maximum years (2013–2015 and 2023–2025), indicating an intensified impact of solar disturbances on local geomagnetic processes.

The scalogram of the global Kp index reveals similar dominant periodicities; however, its energy structure is smoother and extends to longer periods (40–80 days), indicating the contribution of longitudinally and latitudinally averaged processes. Broad zones of elevated power are particularly evident during periods of enhanced solar activity and magnetic storms, highlighting the integrated global response of the magnetosphere to solar forcing.

More extended regions of power enhancement at scales of approximately 30–60 days may be associated with seasonal variations in the orientation of the geomagnetic field and the Earth’s axial tilt (the Russell–McPherron effect), as well as with persistent high-speed solar wind streams.

Local power peaks in the K index often precede similar enhancements in Kp, suggesting that local processes may act as a leading phase in the development of global geomagnetic activity. This observation is consistent with the multifractal analysis results, which showed that local variations exhibit a higher degree of nonequilibrium and intermittency. Hence, local data reveal a more complex structure of high-frequency variability, whereas the global index predominantly reflects long-term and stable modulations.

Figure 10(a, b) present the results of the cross-wavelet (XWT) and wavelet coherence (WTC) analyses, illustrating the time-dependent interaction structure between the local and global geomagnetic activity indices. The regions of enhanced power and coherence indicate stable in-phase dynamics within the 10–30 day period range, confirming a common solar modulation of both local and global magnetospheric processes.

The wavelet diagrams reveal that the relationship between local and global magnetic field variations is distinctly multilevel and nonstationary. The most prominent zones of high cross-wavelet power are observed within the 10–30 day period range, corresponding to the characteristic timescales of solar-rotational disturbances. These regions indicate persistent simultaneous amplification of oscillations in both indices, driven by the influence of long-lived high-speed solar wind streams originating from coronal holes, which periodically interact with Earth’s magnetosphere as the Sun rotates.

During periods of enhanced solar activity (2013–2015 and 2023–2025), an increase in cross-wavelet power amplitude is evident, reflecting the globalized response of the magnetosphere, in which local and planetary-scale processes become phase-synchronized and mutually reinforced.

The combined results of the cross-wavelet (XWT) and wavelet coherence (WTC) analyses confirm the presence of a stable, scale-dependent relationship between the local and global geomagnetic activity indices. At the same time, a pronounced asymmetry in the temporal scales of this relationship is observed, reflecting the hierarchical organization of processes within the Sun–magnetosphere–ionosphere system.

However, even under conditions of high coherence, certain intervals persist in which local variations exhibit autonomous behavior and temporal inhomogeneity of energy distribution. To achieve a deeper understanding of these discrepancies and to quantitatively assess the degree of nonequilibrium in the signals, it is necessary to analyze their internal structure using methods of nonlinear dynamics.

The following subsection presents the results of a multifractal analysis of the K and Kp indices, which provides insights into the complexity of their time series and reveals differences in their scaling behavior and entropy-based characteristics.

The multifractal analysis of the local geomagnetic activity index K (Almaty) and the global index Kp revealed a complex structure of scale variability inherent to geomagnetic processes. The dependences h(q) for both series show a distinct decrease with increasing moment order q, confirming the presence of multifractality and the differences in temporal correlations between weak and strong fluctuations.

For the local K index, the Hurst exponent range h(q) is approximately 0.74–0.83, whereas for Kp it spans 0.79–0.90, indicating a broader and more stable scale hierarchy in the global index, which reflects the integrated dynamics of magnetospheric processes.

Table 1 presents a summary of the estimated multifractal spectrum parameters, providing a comparative overview of the scaling characteristics and complexity measures for both indices.

Figure 11 presents the results of the multifractal analysis of the local geomagnetic index K (AAA) and the global Kp index, performed using the MFDFA method. The plots of the Hurst function h(q) (panels c, d) and the multifractal spectra f(α) (panels a, b) provide a quantitative description of the scale inhomogeneity of fluctuations and highlight the differences in the variability structure of local and global processes.

The h(q) functions for both indices show a clear dependence on the moment order q, confirming the presence of multifractality and the nonuniform distribution of fluctuation intensities. However, the slope of the h(q) dependence for the local K index is steeper and more linear compared with that of Kp, indicating a narrower range of scaling exponents and thus a lower degree of variability in energetic fluctuations. In contrast, the h(q) curve for Kp exhibits a concave shape, characteristic of enhanced nonlinearity and greater sensitivity to extreme disturbances, which are averaged out when forming the global index.

The corresponding f(α) spectra support these findings. For the local K index, the spectrum peaks near α0≈ 1.0 and is nearly symmetric, typical of quasi-stationary processes with moderate intermittency. The Kp spectrum, however, is broader (Δα ≈ 0.20–0.25) and asymmetric toward larger α, indicating the presence of processes with stronger variability and a higher degree of nonequilibrium. This behavior is physically consistent with the nature of the Kp index, which aggregates contributions from observatories located across different latitudinal zones, each influenced by distinct magnetospheric and ionospheric current systems.

The analysis of the temporal evolution of multifractal characteristics made it possible to trace their dynamics over the 2007–2025 period.

Figure 12 shows the time variations of the main parameters of the multifractal spectrum–its width (Δα), peak position (α

0), asymmetry, and entropy–calculated within a sliding window for both the local K (AAA) and global Kp indices. These parameters provide insight into the evolution of complexity and scale heterogeneity of geomagnetic activity over the past two solar cycles.

The time series analysis reveals that the spectrum width (Δα) exhibits quasi-periodic oscillations that correlate well with the phases of solar activity. For the local K index, the range of Δα values does not exceed 0.4, indicating a relatively stable multifractal structure and a moderate degree of intermittency. In contrast, the global Kp index shows a broader spectrum width, reaching 0.7, which reflects a more pronounced multifractality associated with the integration of disturbances originating from different geomagnetic latitudes and current systems.

The parameter α0, which characterizes the dominant type of fluctuations, varies in phase with the solar cycle, decreasing during solar maxima (around 2014 and 2022). This behavior indicates the prevalence of rougher time series during periods of enhanced energy exchange between the solar wind and the magnetosphere. The asymmetry of the spectrum intensifies during strong geomagnetic storms (notably in 2009, 2015, and 2020), signifying an imbalance between positive and negative fluctuations–a typical signature of a system transitioning into an unstable, strongly nonequilibrium state.

The spectral entropy (Sf), which reflects the degree of statistical organization of the multifractal structure, exhibits local minima coinciding with extreme space weather events. Sharp entropy drops in 2015 and 2020 align with the strongest geomagnetic storms of the analyzed period, confirming its diagnostic sensitivity to transitions between quasi-stationary and turbulent magnetospheric states.

A comparison of the two indices reveals that the local K index primarily responds to regional fluctuations of ionospheric current systems, whereas the global Kp index captures system-wide magnetospheric reorganizations characterized by a stronger scale hierarchy. Nevertheless, the high correlation between the temporal evolution of α0 and entropy in both indices indicates a common physical origin of the processes governing the fractal structure of geomagnetic activity.

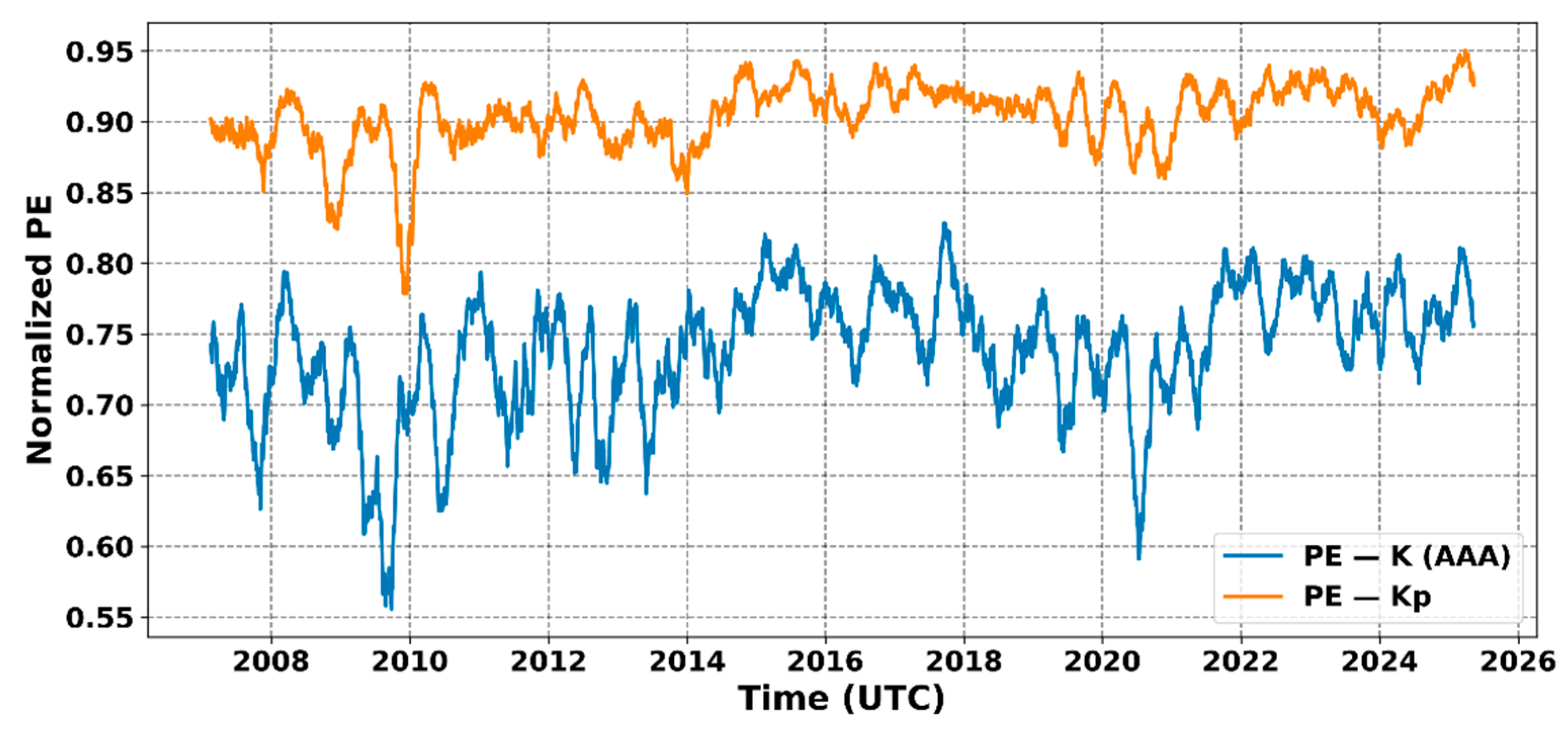

To assess the degree of chaoticity and stochasticity of geomagnetic variations, a permutation entropy (PE) analysis was performed for the local K(AAA) and global Kp indices using a sliding window of 90 days (

Figure 13). The results reveal a distinct cyclic pattern of PE variations that correlates with the 11-year solar cycle: during periods of low solar activity, entropy values are lower, indicating greater regularity and predictability of geomagnetic fluctuations. In contrast, during solar maxima (2003–2005, 2013–2015, and 2021–2024), entropy increases, reflecting the enhanced chaotic behavior of the magnetospheric response.

Throughout the entire observation period, the global Kp index exhibits systematically higher PE values, which points to its greater statistical heterogeneity and the spatially integrated nature of global magnetospheric dynamics. The local K(AAA) index, on the other hand, shows more pronounced PE oscillations, indicating the high sensitivity of the single observatory to local geomagnetic effects—including ionospheric currents, conductivity variations, and regional electrojet dynamics.

Notably, sharp decreases in PE(K) occur during extreme geomagnetic storms—for instance, in 2009 and 2020—which can be interpreted as a transition of the system into a more deterministic regime under the influence of a strong external driver (the solar wind). In such conditions, the magnetospheric response becomes more coherent and organized, consistent with the physical expectation of reduced stochasticity during powerful solar forcing events.

The scatter plot of PE(K) vs. PE(Kp) (

Figure 14) confirms a positive overall relationship between the local and global entropy values; however, the data points are distributed asymmetrically relative to the 1:1 line, clustering mostly above it. This indicates that the global index generally exhibits a higher degree of chaoticity compared with the local one. Such behavior aligns with the understanding that the integrated Kp indicator averages over numerous regional processes, including out-of-phase responses from different geomagnetic latitudes.

The obtained results complement the findings of the multifractal analysis, confirming that geomagnetic activity possesses pronounced structural variability, evident both in its temporal organization and in the stochastic properties of the signals.

A comparative analysis shows that both the local and global indices contain a common set of fundamental periodicities associated with solar-rotational modulations. At the same time, the local K (AAA) index demonstrates greater sensitivity to high-frequency and regional processes, whereas the Kp index represents an averaged global picture of geomagnetic activity, integrating the combined response of multiple magnetospheric regions.

Thus, the combined use of both indices makes it possible not only to identify the global patterns of magnetospheric dynamics, but also to trace the regional features that may play an important role in the study of ionospheric disturbances and their impact on technological systems.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that geomagnetic activity observed in the Almaty region represents a complex superposition of global and local processes interacting across a wide range of temporal and spatial scales. The findings confirm the hierarchical structure of geomagnetic and ionospheric dynamics, reflecting interactions within multiple layers of the Sun–Earth system–from disturbances in the IMF to responses in the lower atmosphere. The nonlinear effects identified in both the local and global indices point to the existence of inter-sphere coupling mechanisms, through which electromagnetic and plasma perturbations in the magnetosphere can influence the dynamics of the atmosphere and troposphere.

In this context, the study by [

27] is particularly illustrative. Based on observations in the Northern Tien Shan, the authors demonstrated the influence of various geophysical disturbance sources on the atmospheric electric field and thunderstorm activity. They showed that the enhancement of the atmospheric electric field and the increase in thunderstorm frequency correlate with magnetospheric–ionospheric variations, indicating vertical energy and charge transfer between atmospheric layers. These results expand the understanding that geomagnetic and ionospheric variations, as reflected in ground-based indices, can serve as indicators not only of space weather conditions but also of meteorological processes shaped by its influence.

The strong linear correlation between K(AAA) and Kp confirms that the main dynamics of the geomagnetic field at midlatitudes are governed by global disturbances associated with the solar wind and IMF. However, the persistent positive bias of the local index relative to Kp, along with the observed diurnal and seasonal asymmetry, highlights the role of regional factors that modulate the magnetospheric and ionospheric response depending on local geophysical conditions.

The most pronounced differences between the local geomagnetic index K(AAA) and the global index Kp are observed in the dayside sector, where the enhancement of Sq current systems and the increase in ionospheric conductivity occur under the influence of solar radiation. This effect is well documented in midlatitude observatory data and described by [

28] and [

8], who demonstrated that daytime variations in conductivity and Sq currents depend strongly on solar illumination, local time, and geomagnetic latitude.

The daytime maximum of K(AAA) reflects not only the impact of global current systems, but also the contribution of local electrojets that are distributed unevenly in longitude and latitude [

29]. These regional current structures can enhance magnetic field perturbations near the observatory, leading to a systematic excess of local index values over the global ones. This effect highlights the higher sensitivity of local indices to the fine structure of ionospheric current systems and the geo-electrical characteristics of the region.

The seasonal modulation of K(AAA) is in phase with the well-known Russell–McPherron effect, which arises from the geometric dependence of magnetic reconnection efficiency at the magnetopause on the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) [

25,

30]. The enhancement of geomagnetic activity near the equinoxes reflects an increased energy transfer into the magnetosphere under favorable IMF orientation, a feature evident in both global and regional indices [

31]. However, for the local K(AAA) index, this effect is amplified by regional variations in ionospheric conductivity, resulting in more pronounced diurnal and seasonal changes in the amplitude of geomagnetic activity.

Spectral analysis revealed that the structure of K and Kp variations is governed by several dominant scales: the 27-day cycle associated with solar-rotational modulation, and the 3–9-day range, related to processes within the magnetosphere and ionosphere. The more pronounced short-period oscillations in the local index arise from its sensitivity to substorm activity and localized disturbances in ring and polar current systems. These findings indicate that the spatial averaging inherent to the computation of Kp suppresses many regional variations, whereas the local index captures them in full detail.

Wavelet analysis methods revealed a complex, hierarchically organized temporal-scale structure of geomagnetic activity. Unlike classical correlation analysis, the wavelet approach allows the exploration of scale-dependent synchronization between signals and identifies the time intervals and periods where local disturbances are most coherent with global magnetospheric dynamics. This provides a means to track the evolution of phase relationships between indices, distinguishing intervals dominated by solar-induced periodicities (e.g., rotational cycles) from those where local processes exhibit autonomous behavior.

The local K(AAA) index is dominated by short-period and subrotational components, while the global Kp index exhibits stronger seasonal and cyclic oscillations. The joint analysis indicates a correlated but nonuniform dynamic relationship between local and global geomagnetic processes, confirming the multifractal nature of Earth’s magnetic field variations.

The wavelet coherence (WTC) analysis further supports these conclusions: coherence values exceed 0.8 in the 10–30 day range, and the interaction phase is predominantly in-phase, indicating synchronous behavior of both components. The regions of high mutual coherence within the solar-rotational period range (~27 days) confirm that both indices are controlled by common solar–geophysical sources, primarily high-speed solar wind streams (HSS) and the interaction between the solar magnetic field and Earth’s magnetosphere [

32,

33].

At shorter timescales (<10 days), the wavelet coherence between the local and global indices noticeably decreases, and the phase relationship between their oscillations begins to diverge. This effect is interpreted as a manifestation of local ionospheric processes, including electrojet activity, conductivity variations, and the spatially heterogeneous development of current systems in longitude and latitude [

28]. Such regional effects can modulate the amplitude and phase of geomagnetic variations, introducing additional nonlinearities into local indices. The observed phase leads of the local K(AAA) index relative to the global Kp by 3–6 h in the dayside sector reflect the temporal instability of the magnetosphere–ionosphere response. Similar phase shifts were previously observed in comparisons between the AE, Dst, and Kp indices and interpreted as differences in the energy transfer delay between regional and global systems [

34]. This confirms that local ionospheric processes respond more rapidly to solar wind disturbances than do globally integrated measures.

The ROC analysis provided a quantitative evaluation of the diagnostic capability of the local K(AAA) index relative to the global Kp in detecting extreme geomagnetic events. A storm threshold of Kp ≥ 6 was adopted, following the international geomagnetic storm classification [

13]. For the local index, the true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR) were computed to construct the ROC curve and determine the area under the curve (AUC). The resulting AUC ≈ 0.92 indicates high sensitivity and specificity, demonstrating that K(AAA) reliably detects global disturbances captured by Kp while also identifying local events not fully represented in global indices. Similar conclusions were reached by [

14], where ROC analysis was applied to assess the performance of K-index forecasting models.

Notably, during the onset phase of geomagnetic storms, the local index K(AAA) exhibits a lead of several hours relative to Kp. This finding is consistent with [

35] and [

36], who reported that regional ionospheric responses occur earlier due to differences in local conductivity and current system configuration. Such behavior underscores the importance of K(AAA) for real-time (nowcasting) and regional space weather diagnostics, particularly in regions with pronounced ionospheric effects.

The multifractal analysis further confirmed that geomagnetic activity possesses a strongly nonlinear, multiscale structure that cannot be reduced to simple linear correlations or stationary processes. The broad singularity spectra f(α) and elevated entropy values indicate the intermittent nature of geomagnetic variability, arising from the alternation of quiet and disturbed magnetospheric states [

37,

38].

For the local K(AAA) index, the multifractal spectra f(α) are broader and more asymmetric compared to those of the global Kp index, indicating its higher sensitivity to short-lived but intense events that enhance the multifractal properties of the time series. A similar pattern has been observed for the AE and SYM-H indices during geomagnetic storms, when the cascade of energy exchange between different temporal and spatial scales becomes more pronounced [

39].

An increase in the spectrum width f(α) and entropy during storm periods is consistent with the concept of multi-level energy coupling between macroscopic solar-wind flows and small-scale ionospheric current structures [

40]. This behavior indicates that the intensification of geomagnetic activity is accompanied by a rise in multifractality, signaling the system’s approach to a critical state. The comparison of local and global indices also shows that multifractal properties persist across spatial scales, reflecting the universal hierarchical organization of geomagnetic processes. However, differences in spectrum width and shape emphasize the importance of regional factors, such as ionospheric conductivity, station location, and local current systems, which must be considered when developing spatio-temporal magnetospheric models and nonlinear geomagnetic disturbance indicators.

A comparison between the diurnal and seasonal variations shown in

Figure 2 and the results of multifractal analysis reveals that periods of enhanced regional activity (evening hours and equinox seasons) correlate with broader f(α) spectra and increased asymmetry, indicating a strengthening of nonlinear processes and a higher contribution of rare, extreme fluctuations to the overall magnetospheric dynamics. The evening maxima of K(AAA) correspond to periods of enhanced ionospheric currents and strong magnetosphere–ionosphere coupling, during which multifractal metrics record a rise in scale variability—a signature of transition to a more turbulent regime. Thus, the spatio-temporal patterns detected on heat maps are directly reflected in changes in multifractal characteristics, confirming the tight link between the temporal structure and scale organization of geomagnetic activity. This is consistent with the concept of the self-organized nature of magnetospheric processes, where local variations collectively shape the global energy-exchange dynamics between the Sun, magnetosphere, and ionosphere.

The PE analysis demonstrated that global variations exhibit greater stochasticity and lower regularity than local ones, while local indices show entropy reduction during storms, reflecting more deterministic behavior of the system. The long-term evolution of PE follows the solar activity cycle, confirming the presence of nonlinear transitions between distinct magnetospheric states.

Of particular interest is the potential of multifractal characteristics as diagnostic and forecasting parameters of geomagnetic activity. As storm conditions approach, the statistical shape of f(α) systematically changes–its broadening, peak shift, and asymmetry increase, reflecting a transition from quasi-stationary to nonlinear, energetically unstable regimes. To quantify their predictive capability, binary classification methods, such as ROC analysis, can be applied to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of multifractal indicators relative to storm thresholds (Kp ≥ 6). Preliminary results show that integral metrics—the spectrum width (Δα) and entropy (Sf)–achieve AUC values above 0.8, indicating a high discriminative power between quiet and disturbed magnetospheric states.

Thus, the multifractal characteristics of K and Kp indices can serve not only as descriptors of nonlinear geomagnetic variability, but also as physically grounded precursors of geomagnetic storms. Their integration into ensemble forecasting models, together with solar-wind and IMF parameters, may significantly enhance the efficiency of early-warning systems for space-weather disturbances.