1. Introduction

How to explain the productive manifestations of learning outcomes? What’s there in common with the theory of productivity? How do learning outcomes influence productivity and modulate productiveness? Learning has become one of the most important determinants of productivity today, whereas knowledge (technical and methodological) has become a form of “productive” power. This productive power—whether we call it skills, competencies, abilities or aptitudes, it’s all the same interpreted in idiosyncratic perspectives. In economic sense, however, productivity is explained by theories—by that of the theory of production (Wolman, 1921; Frisch, 1964). In another important context, it is imperative to understand productive human capital, since it is explicitly linked to learning, creativity, and eminence (Walberg & Stariha, 1992). Human capital is put to use to generate outcomes, e.g., production of knowledge, goods, and services, and wealth creation, asset building, etc. The question, therefore, remains that of the productiveness of human capital, and productivity of the individual, moreover. A simple and unambiguous answer to all these questions is the outcome and utility that determine the productiveness of capital resources, including that of human resources itself. Today, the entire world is embracing the concept of productiveness and productive efficiency. It thus appears that the productive manifestations of individual efforts, including that of learning outcomes and outcomes of organised efforts, do constitute the fundamental backbone of the theory of productivity.

It is imperative to refer to the law of increasing productivity as a transformer of value and utility by which to attain maximum productive efficiency (Mella, 2019). In this age of digital transformation and artificial intelligence, “effective outcomes” are governed by laws of productivity, but these are not strictly any ‘standard laws’ by which we can define productivity. By law of productivity, it is strictly meant here the economic theories of production which function as laws that govern and drive productivity in this age of automation and AI. It is a fact that AI and automation are linked to economic growth (Aghion, Jones & Jones, 2017), but it is also true that AI is itself a tool of automation which is set to automate many human tasks and industrial operations. It is, therefore, a productivity tool, and there are no laws by which we can define its extent or impact on the economy as a whole. For, there exist no definite laws of productivity that could explain production function. Nevertheless, in economic sense, production function can be defined as “organised human or industrial action of making goods or services as merchandise for sale”. The objective ideals at work concerning production function can be understood as a “capability” of a system to generate or produce by virtue of productive power goods and services—ordinary and hi-tech, both. It encompasses ‘management of technology’ and ‘organisation of technical expertise’ under one roof.

Productivity, then, can be considered a power and a tool for individuals, organisations, and industries, but then, it remain a paradox beyond which we need to advance (Brynjolfsson & Hitt, 1998). It depends on what context or perspective the word “power” is expressed as an organisational trait: Singh (2009) suggests that the use of expert power is more beneficial to organisations than other kinds of authoritarian powers, and that it promotes better decision making. Expert power of productivity is an enabler, which we believe it to be true, too, meaning that it influences organisational ability to get things done. The power to manage productivity and processes, however, is inherent to every organisation’s core competence development program. Both social and economic progresses rely heavily on the shoulders of management processes and productivity function. Today, productivity is driven by ideas, and even simple ideas could have large productive impacts. But perhaps we do not as yet need theories to hypothesize or explain digital productivity, for it is widely and implicitly understood. And yet there remains a field wide open for exploration and assumption of the possibility of the impact of AI on economic growth—e.g., unbounded growth prospects which always challenge conventional paradigms of economic productivity (Aghion, Jones & Jones, 2017). Leaving it aside, what we aspire to study is the productive manifestations of human potential to boost outputs, be it by use of electronic tools or digital gadgets, or simply, human effort.

This research, therefore, is a small step forward toward such a deeper understanding of human productivity and productive potential.

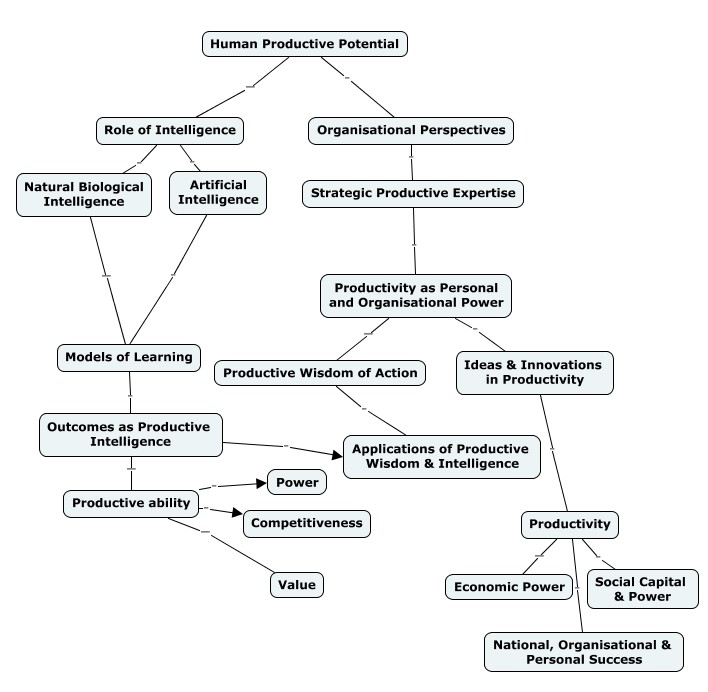

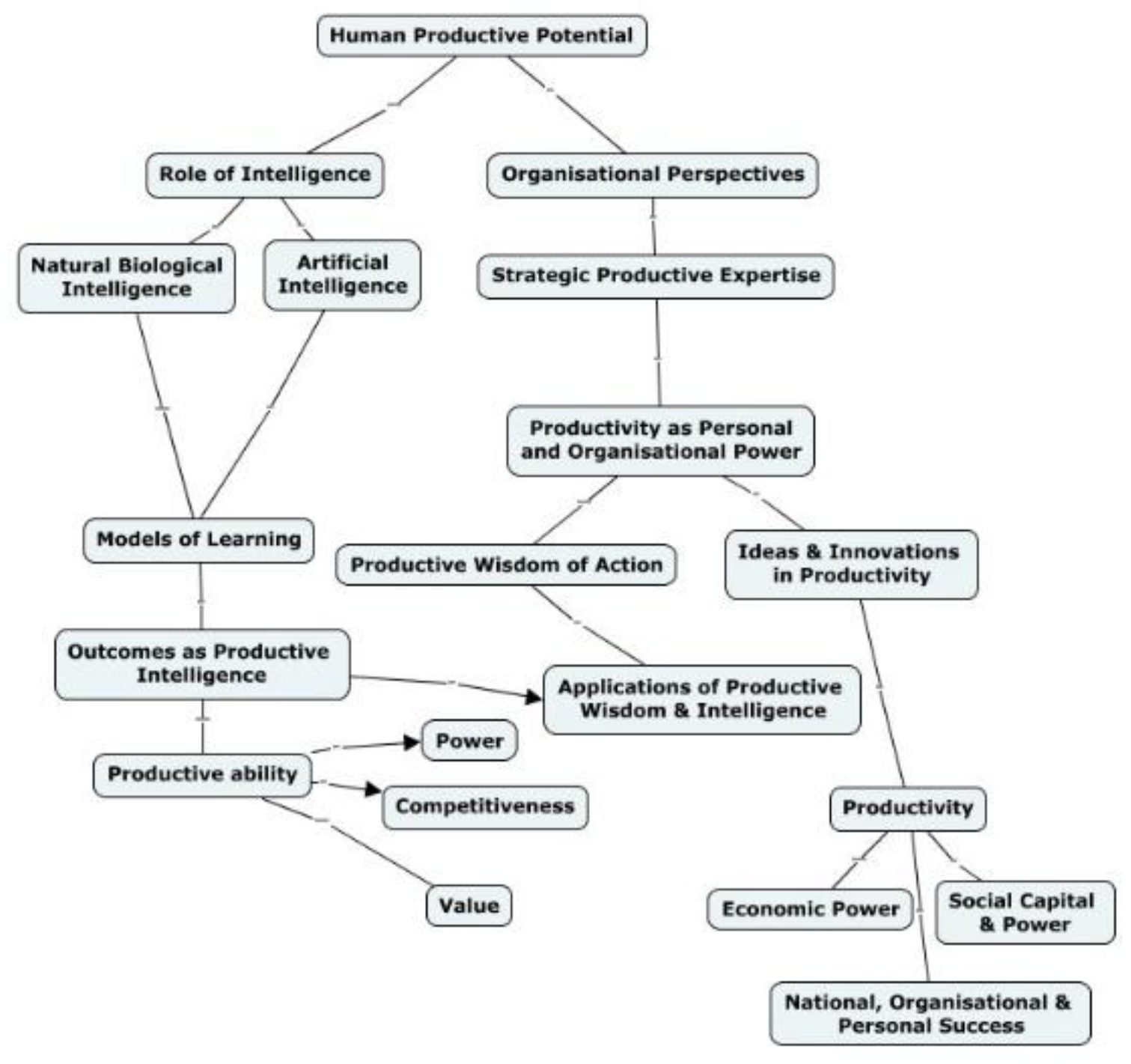

Human Potential and Productivity research is slowly taking forward strides in incorporating various models of learning, while their outcomes as a form of intelligence could be utilised to help develop powerful systems mirroring AI-driven agents, which has today become a vogue. Today, every organisation—small or big is inclined to nurture

productiveness among their employees and workforces, for competition has taken a new form and shape with the adoption of generative artificial intelligent systems (O’Connor, 2024). Firms have not failed to understand its economic significances—the importance of nurturing

productive abilities. Productive ability is itself a great power. This power is illustrated in

Figure 1 below.

Highly productive individuals are valued, respected, and esteemed everywhere. The economic importance of productivity is a well acknowledged fact as studies have been devoted towards understanding how wisdom of production—aka productive intelligence can further boost human potential in making us more productive (Marzall et al., 2022), and competitive at the same time. Companies are keen in developing strategic management expertise at the ground level aimed at guiding production or streamlining productivity in this age of intelligence. We may call it Strategic Productive Expertise (SPE). Productivity, thus, has become a ‘form of knowledge’ today, a formidable tool—the “knowledge” of expertise and efficiency bundled together in truest sense. In “productive sense”, however, the prime importance of productive knowledge typically relates to:

Productive wisdom of action

Productive intelligence in applications

Ideas and Innovations on productivity

Productivity is both an economic and social power. It is an important indicator of social health and economic progress of a nation (Roxana et al, 2023), as well as its citizens. One can attract wealth with the wisdom and power of productivity. Productivity, hence, is also a personal power. People make impressions on others with their productive abilities. Both individuals and organisations accomplish many things with the power of productivity or by virtue of being productive. In practice, it is a formidable tool and a power for achieving success (Bernolak, 2009; Woods et al, 2013). Now, we shall examine how the outcomes of learning are manifested in productivity.

2. Productivity for Success!

The clear motto of this age could be read as following: Productivity for Success! Here, in practice, one complements the other. In theory, some ideas tend to be productive or are born out of creative thinking, having the ability to stir productivity in individuals. A theory that enables one to predict the effects of actions with great precision must have on the individuals some of its effects virtually felt by virtue of productive outcomes which, in fact, act as factors that limit or modulate productive possibilities. Hence, we should remain open to progressive ‘productive’ ideologies or ideologies that promote productivity among the people. Idealism and ideologies have often proved to be dangerous philosophies, but any good productive ideology that rises above idealism powered by a true sense of need for productivity cannot be considered a dangerous tool, but an instrument of growth, development, and social stability of which the latter is no less important than the former ones. There are “factors” or determinants that contribute to productive ‘stability’. But these are not the same factors that “determine” human productivity. Tangen (2005) discusses the determinants of productivity in detail, which reveals interesting facts concerning those factors that actually determine productiveness.

The power of productivity is universally recognised as an advantage and a strength. This is the reason behind the link between management practices and productivity and performance of firms and organisations (Siebers et al., 2008). Productivity is a power which drives the engine of economic growth. There are times of greater productivity which individuals often have had the need to encounter. On the other hand, the problem of “low productivity” thrives in many societies across many nations, and even constant efforts fail to produce effects due to wastage of time and resources (Srivastava and Barmola, 2011). It isn’t surprising that we are often called to accept certain challenges representing social and economic situations and contexts that demand higher activities, efforts or struggles from our end. The question of importance is then aligned to the support of productive efforts when reason tells otherwise. To attain a position of higher productivity as well as to maintain a certain level of “productive momentum” consequently requires necessary guidance and expertise.

It shall be noted that although an effective routine does the job of making us productive, it needs be taken care of that that such a routine be followed or obeyed in practice, and without fail. Hence, it might be necessary to call upon reason to manifest itself in full power and ability to render us more productive. The reason for being productive is a “stimulus”, which must be understood well. This makes us think about productivity. The goal of this paper, therefore, is to deliver individuals from the yoke unproductive inertia and inspire the passion of productivity in them. To this end, we undertake a study of productivity, its manifestations, and learning outcomes concerning how the effects of profound learning could stir productivity within us.

3. Thoughts on the Theory of Productivity

Productivity attracts attention. It is the outcome of human actions in a coordinated manner. We can take the trouble to grow lofty ideas, but unless those ideas are transformed into reality through actions, there wouldn’t be any outcome at all. The first principle of productivity is action: e.g., doing. We can do a lot with little means, or can employ large amount of resources to achieve very little. Productivity is the measure of how much or how little is achieved or attained using a fixed amount of inputs (Diewart, 1992; Rogers & Rogers, 1998). Expertise is always a necessary factor to become highly productive. But it is not easy for everyone to become highly productive, for productivity is the key element of attaining success, and not everyone becomes highly successful in becoming highly productive. Therefore, productivity is dynamically linked to success. There are more people who fail than those who succeed, but those who achieve success set examples to lead those who trail behind.

One element of importance to note is that, procrastination is a form of unproductive behavior (Peper, 2014). Various factors thwart human progress, and procrastination is one among these factors that contribute to low productivity. Although delay, deferment, and unnecessary rescheduling leads to procrastination, it presents as obstacle which even experts often fail to override. Thoughts on productivity alone can’t solve the problem of procrastination that we often face concerning the theory of action which can make us become more or less productive and efficient. Amit et al (2021) presents a framework aimed to prevent procrastination and improve productivity. They believe, and truly do so, that procrastination is an obstacle to productive session. Roxana et al (2023) attempts to examine the relationship between productivity, burnout, and procrastination with regard to the development of personalised strategies to manage stress and time aimed at enhancing performance, which offers rich information on this issue.

With regard to the energy dynamics of the mind in relation to the theory of productivity, it can be aptly said that continuous practice nurtures productive energy. Nonetheless, for an individual or a system, howsoever advanced it might become, it will still fail to acquire “infinite” productive capacity and power. But it is possible for the mind to harness a certain amount of productive energies through continuous practice of learning, but it never approaches infinity. Hence, learning embodies the mind with the power to become proactive, which is an outcome of transformative learning as it alters learners’ perspectives, interpretations, and responses (Maiese, 2017). Hence, there exists explicit link between learning and productivity.

To aim for the highest that life can offer demands productive actions that determine outcomes.

On various instances, it is often our own reason which becomes the counsellor and guide to low productivity. Hence, it is necessary to build up productive relations in society which we can leverage in times of need. But beyond these, what’s required is the best and most illustrious mode of production and knowledge of it as reward for performing higher tasks. The best modes of achieving productivity constitutes a kind of knowledge to reckon with. It also denotes the most effective mode of production that increases human productive efficiency.

Productivity Fact Check: To boost the power of human productiveness, streams of mental energies are necessary for the sake of strength and courage of constancy in maintaining a higher productivity level. Hence, there is the very need for productive impulse. It is supposedly true that one can attain perfection through productivity and practice, the only need being that is to call upon our intrinsic latent potential to manifest itself in full power. This may sound as a “subjective theory” but it is has its fundamental basis embedded in objective theory of action. In this research note, we examine the productive manifestations of learning outcomes, since learning is an energy dependent process, experiential in nature, by the power of which knowledge and wisdom of productivity are usually gained. This necessitates an effective framework of ingenious learning which helps channelizing the hard effort into productive outcomes. It will help us examine and understand the “productive manifestations” of learning outcomes. The outcomes of learning depend on how well the learner has acquired useful knowledge that has significance for him/her, in terms of results brought about or the effects which learning produces on the learner. The “productiveness” of learning outcome—therefore, is a relative notion in this context.

4. Productive Manifestations of Learning Outcomes

In what manner the outcomes of learning are manifested in productivity? Both learning and productivity are energy dependent activities. Productivity being an “energy dependent” and effort making process, its outcomes are measured in terms of efficiency and output. Productiveness, on the other hand, is the real value of effort in terms of effectiveness of actions, i.e., doing the right things. Peter Drucker (2018) very aptly distinguishes between efficiency and effectiveness, wherein, he states that:

Efficiency is doing things right. Effectiveness is doing the right things.

Now, streams of energy are necessary to effect actions that may bear positive (productive) or fruitful outcomes. Every creative or productive program must involve some expenditure of energy, where energy is embedded in outcomes. Expression of energy and strong determination to accomplish a task is itself a ‘productive’ endeavor. The productive manifestation of ideas emerge out of the concerted and coordinated actions from the part of the doer. Specific conditions do serve the purpose, which are responsible for supporting productive activities (Chatterjee, 2025). Now, at the individual level, learning greatly influences productivity and determines the effectiveness of outcomes. Also, there are regions of higher activities where people migrate for better opportunities, as the conditions favor such. These regions turn out to be the centres that manifest human productivity and productiveness at higher levels.

Businesses and most forms of profit making organisations are always in search of most efficient means of attaining higher productivity as well as efficiency. They promote their (market) power and efficiency through various channels for the purpose of serving the society grounded on common reasons; i.e., service for profit being their prime motive. The role of learning and outcomes of learning are intertwined explicitly to most forms of organised human activities, including that of all profit-seeking organisations. It is because knowledge is obtained by means of learning or noesis which is characteristic of productive outcomes. The modes of knowledge acquisition are varied, e.g., education and learning by means of direct experience, reading, lectures, dialectical modes, observation, reasoning, discourse, practice, and through productive actions as these constitute the primary routine elements of edification. Therefore, productivity is linked to learning outcomes as a result of different modes of cognition. The use of objective methods in routine practice of learning, too, have their effects felt on the productivity frontiers by moderation of efficiency and effectiveness. Lastly, the didactic intents of the prescriptive descriptions of productive routines are felt along various channels of workflow and knowledge transmission. It explains the metaphysics of relative productivity linked to learning outcomes.

5. Effects of Learning on Productivity: Theoretical Inferences

Learning has positive and constructive effects on human productivity, and it is a facilitator of productive actions. Actions without knowledge, and knowledge without actions are both imperfect manifestations of human potential. Knowledge is gained through learning as it imparts necessary wisdom of action and productivity. A dynamic relationship between knowledge, wisdom and learning could be postulated using a hypothetical concept:

“No amount of wisdom gained is lost but converted to latent productive potential.”

Thus formulated, it signifies an important concept: the subtotal of wisdom of an intellect varies in accordance to changes in power acquired through learning. It signifies an increase in “mind power” as a result of learning, and there it constitutes the knowledge of action: i.e., doing things in a better way which is both efficient and effective. It improves productivity and makes an individual become more productive. Formulated otherwise, the “productive power of an individual or a system varies according to the changes in learning patterns.” The wisdom that remains latent is never lost but could be called into action as potential “noetic power” characterising productive action. By noetic power it is simply meant here our intellectual capabilities.

An individual’s capacity to learn determines the total wisdom which expands as an effect of learning and which is transformed into “latent potential power”, or “latent productive potential”. Wisdom once gained is never lost—but may be stored as implicit memory in the form of repressed knowledge—a concept in cognitive psychology (Talvitie & Ihanus, 2002). Acquired knowledge or wisdom which is not immediately used isn’t lost either: it forms a component of stored information which is a form of potential energy and can be converted into kinetic energy in times of need (Spender, 1996; Bratianu & Bejinaru, 2019). In this context, alike Bratianu and Bejinaru (2019), I have considered energy as a source of semantic field—where knowledge can be considered a field obeying thermodynamics principles.

One can properly harness the power of wisdom from learning when it is closely aligned with purpose. The latent form of wisdom is accessible through deep learning, relearning, thoughtful reflection, and cogitation. When accumulated, the subtotal of wisdom constitutes the store of intellectual power whose effectiveness depends on intelligence level, memory, environment, attention, focus, willpower, and habits. The value of wisdom hence varies depending on one’s ability to utilise it—as it exists in potential form. It is attained through learning, training, and education, observation, as well as experience. But how it is linked to productivity? Potentiality and actuality. The potential form of power inherent in wisdom thus accumulated becomes active when actualised as it renders an individual productive. Hence, power, knowledge, and learning are dynamically entwined as one without the other is rendered ineffective.

The unequivocal impact of learning on human productiveness remains unchallenged, however, and thus forms the fundamental basis of the theory of productivity in modern context. It shall be noted herein that the derivation of a law corresponding to the theory of productivity is deliberate on account of the established effects of learning on productivity. The outcomes of learning having its effects being felt on human potential and productiveness can be readily measured, which is apparent through applications of advanced standard appraisal systems measuring human (employee/workforce) productivity.

Now, the theory of productivity is born out of the classical concepts of production function. The modern concept of productivity, however, varies significantly from its classical counterparts. We shall examine yet all this how so it varies.

5.1. Productive Outcomes of Learning:

Productive power is a dynamic force—and it is also a quality which depends on the outcomes of learning strategies. Learning multiplies power when it becomes a flexible tool of intellectual development, growth, and maturation (Bratianu & Bejinaru, 2019). The primary goal is to generate productive, transformative outcomes which are reliant on the capacity to align knowledge with goals and purposes (Davis, Kee & Newcomer, 2010). We believe that long-term transformations of organisations seeking strategic competence development aimed towards improvement in productivity necessitates acquisition of information and knowledge (Davis, Kee & Newcomer, 2010). Here, latent wisdom gained previously through learning can be reactivated in future when the need for such arises. Productive power here refers to the capacity to generate “positive outcomes” based on skills, cognitive resources, adaptability, and effectiveness of learning patterns.

Learning patterns evolve over time (Papini, 2002), in cooperation with depth, modularity and efficiency. Wisdom gained from learning modulates the human capacity to produce, helping individuals become creative, proactive. It aids in actualisation of latent potential to generate meaningful outcomes in future. The quality of learning mechanism hence is an important determinant of productivity (Pastuszak et al., 2013). Outcomes from learning become productive only under certain given conditions which are dynamically determined by adaptability to mechanisms of learning, system’s ability to access information, feedback, reflection, and the applicability of the generative power of knowledge and wisdom thus gained from learning.

5.2. The Modern Theory of Productivity vis-à-vis its Classical Counterpart

Speaking of and about the classical theory of productivity, in the past, production function used to be a rather simple computation of input/output quotient. The concept of productivity begun to take its form and shape following Karl Marx’s theory of productivity (Gough, 1972). It wasn’t fully developed until Taylor (1998) introduced the scientific management system, under the ambit of which productivity and Total Factor Productivity were conceived in new light. He introduced such concepts like scientific selection of employees, their special abilities and deficiencies, to help them achieve a high level of efficiency (Taylor, 1998).

But before these, Ricardo and later on Schumpeter have had their ideas reflected on the theory of the economics of productivity, thereby shedding new lights on the old subject. And yet, for the most part of the beginning of the past century the ‘concept of productivity’ was somewhat marginalised by general management staffs. Not in the private sector, though, it was less developed or discussed, but in the public sector it was so, since one must consider the matter of effectiveness and efficiency in conceptualising productiveness (Linna et al., 2010). It was well acknowledged but less talked about; well discussed but often more ignored in common debates. The only thing was that, industrial production have had their best opinions and facts revealed on the theory of productivity, and this term remained bound to the most productive sectors of the economy—i.e., the manufacturing sectors which constitutes the backbone of industrial production and productivity. In simple sense, productivity is more closely linked to industrial operations, although it is relevant for all sectors. It is true that all things come into existence by means of production. Productivity, therefore, is a function. Learning, too, is a function of action. Learning becomes effective when knowledge is applied to generate value or create things that have utility and applications. Learning becomes productive when it is employed to produce things of value and utility. Therefore, outcomes of learning is a power, and such power is manifested in productivity.

In essence, the classical theory of productivity can be categorised into three preliminary phases:

Ricardian theory of production (Knight, 1935)

Marxian—concerning labour productivity (Gough, 1972 ; Hunt, 1979)

Schumpeterian productivity and competition having booster effect on growth (Aghion & Howitt, 1998)

Post Modern Industry 4.0 (Digital productivity), Jovevski (2023)

The Modern day is witnessing a new dimension of production the productivity of which is being powered by Artificial Intelligence-driven “digital efficiency”. It may be defined as productivity in the virtual space. The adoption and application of AI-based tools have undeniably increased productivity levels of individuals and organisations, as surveyed by George (2024), though extensive analyses are still ongoing on this phenomenological supposition (Necula, Fotache, & Rieder, 2024). Even if we consider productivity an independent trait of human nature, it is gradually being modulated and heavily influenced by AI tools of today.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, I have discussed the productive implications of learning outcomes and how they influence productivity states. Learning has a definite outcome on productivity, as it influence and powers it. In this brief research, I have highlighted the essence and the importance of productive learning and its outcomes as a tool and potential, both, in the service of the individual. It could be seen from the analysis that productivity is a power, and it is itself powered by learning and its outcomes. In this respect, productivity is an essential, if not the most important, element characterising human potential.

Acknowledgements

The author extends his gratitude to the V.S. Krishna Central Library, Andhra University for providing access to conduct this research.

References

- Aghion, P. , Jones, B. F., & Jones, C. I. (2017). Artificial intelligence and economic growth (No. w23928). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Amit, A. J. , Shankararam, S. G., Pradeep, P., Perumalraja, R., & Kamalesh, S. (2021, May). Framework for preventing procrastination and increasing productivity. In 2021 3rd International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICPSC) (pp. 228-232). IEEE.

- Bernolak, I. (2009). Succeed with Productivity and Quality. Quality Press.

- Bratianu, C. , & Bejinaru, R. (2019). The theory of knowledge fields: a thermodynamics approach. Systems, 7(2), 20.

- Brynjolfsson, E. Hitt, L. M. (1998). Beyond the productivity paradox. Communications of the ACM, 41(8), 49-55.

- Davis, E. B. , Kee, J., & Newcomer, K. (2010). Strategic transformation process: Toward purpose, people, process and power. Organization Management Journal, 7(1), 66-80.

- Diewert, W. E. (1992). The measurement of productivity. Bulletin of economic research, 44(3).

- Drucker, P. (2018). The effective executive. Routledge.

- Frisch, R. (1964). Theory of production. Springer Science & Business Media.

- George, A. S. (2024). AI-enabled intelligent manufacturing: A path to increased productivity, quality, and insights. Partners Universal Innovative Research Publication, 2(4), 50-63.

- Gough, I. (1972). Marx's theory of productive and unproductive labour. New left review, 1, 47-72.

- Ioana-Roxana, F. , Lavinia-Alexandra, J., Dana, M., & Mihaela, S. (2023). The relationship between productivity, burnout and procrastination at work. BlackSea Journal of Psychology, 14(4), 361-377.

- Jovevski, D. , Drakulevski, L., & Firfov, O. (2023). Digital Transformation and Productivity. KNOWLEDGE-International Journal, 59(1), 15-21.

- Knight, F. H. (1935). The Ricardian Theory of Production and Distribution1. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science/Revue canadienne de economiques et science politique, 1(2), 171-196.

- Linna, P. , Pekkola, S., Ukko, J., & Melkas, H. (2010). Defining and measuring productivity in the public sector: managerial perceptions. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23(5), 479-499.

- Maiese, M. (2017). Transformative learning, enactivism, and affectivity. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 36(2), 197-216.

- Marzall, L. F. , Kaczam, F., Costa, V. M. F., da Veiga, C. P., & da Silva, W. V. (2022). Establishing a typology for productive intelligence: a systematic literature mapping. Management Review Quarterly, 72(3), 789-822.

- Mella, P. (2018). The law of increasing productivity. International Journal of Markets and Business Systems, 3(4), 297-316.

- Necula, S. C. , Fotache, D., & Rieder, E. (2024). Assessing the impact of artificial intelligence tools on employee productivity: insights from a comprehensive survey analysis. Electronics, 13(18), 3758.

- O’Connor, A. J. (2024). Organizing for Generative AI and the Productivity Revolution: Reshaping Organizational Roles in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Springer Nature.

- Papini, M. R. (2002). Pattern and process in the evolution of learning. Psychological review, 109(1), 186.

- Pastuszak, Z. , Helo, P., Lee, T. R., Anussornnitisarn, P., Comepa, N., & Fankham-Ai, K. (2013). Productivity growth: importance of learning, intellectual capital, and knowledge workers. International journal of innovation and learning, 14(1), 102-119.

- Peper, E. Harvey, R., Lin, I. M., & Duvvuri, P. (2014). Increase productivity, decrease procrastination, and increase energy. Biofeedback, 42(2), 82-87.

- Rogers, M. , & Rogers, M. (1998). The definition and measurement of productivity (pp. 1-27). Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

- Siebers, P. O. , Aickelin, U., Battisti, G., Celia, H., Clegg, C., Fu, X.,... & Peixoto, A. (2008). Enhancing productivity: the role of management practices. Submitted to International Journal of Management Reviews, Forthcoming.

- Singh, A. (2009). Organizational power in perspective. Leadership and management in Engineering, 9(4), 165-176.

- Spender, J. C. (1996). Organizational knowledge, learning and memory: three concepts in search of a theory. Journal of organizational change management, 9(1), 63-78.

- Srivastava, S. K. Barmola, K. C. (2011). Role of motivation in higher productivity. Management Insight, 7(1), 63-82.

- Talvitie, V. Ihanus, J. (2002). The repressed and implicit knowledge. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 83(6), 1311-1323.

- Tangen, S. (2005). Demystifying productivity and performance. International Journal of Productivity and performance management, 54(1), 34-46.

- Taylor, F. W. (1998). The principles of scientific management. 1911.

- Taylor, F. W. (2004). Scientific management. Routledge.

- Vlcek, R. Trunecek, J., Nový, I., & Drucker, P. F. (1997). Peter F. Drucker on management. Journal for East European Management Studies, 2(1), 79-96.

- Walberg, H. J. , & Stariha, W. E. (1992). Productive human capital: Learning, creativity, and eminence. Creativity research journal, 5(4), 323-340.

- Wolman, L. (1921). The theory of production. The American Economic Review, 11(1), 37-56.

- Woods, M. I. , Woods, T., Rosenberg, M., Silvert, D., Weissman, J., & Finney, M. I. (2013). Business Productivity Strategies for Success (Collection). FT Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).