Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

3.2. Discussion

4. Conclusion and Suggestions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

lengkap dengan bentuk lengkapnya:

| Acronim | Full Form |

| N-Gain | Normalized Gain |

| KKM | Kriteria Ketuntasan Minimal(Minimum Mastery Criterion) |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| PBL | Problem-Based Learning(disebut dalam diskusi sebagai kemungkinan model yang mirip atau terkait) |

| AKM | Asesmen Kompetensi Minimum(Minimum Competency Assessment – bagian dari evaluasi nasional di Indonesia) |

| UIN | Universitas Islam Negeri (Islamic State University) |

| SMP | Sekolah Menengah Pertama (Junior High School) |

| df | degrees of freedom(istilah statistik, bukan akronim institusional) |

| p-value | probability value |

References

- Lubis, A. B., et al. (2019). Influence of the guided discovery learning model on primary school students’ mathematical problem-solving skills. Mimbar SD, 6(2), 253–266. [CrossRef]

- Kamaluddin, M., & Widjajanti, D. B. (2019). The impact of discovery learning on students’ mathematics learning outcomes. IOP Conference Series: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1320(1), 012038. [CrossRef]

- Hariyanto, H., Hikamah, S. R., Maghfiroh, N. H., & Priawasana, E. (2023). Discovery learning model integrated RQA to improve critical thinking skills, metacognitive skills and problem-solving through science material. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Rahmi, C. N., Jailani, J., & Chrisdiyanto, E. (2024). Improving communication, problem-solving, and self-efficacy skills grade-10 students through scientific approach based on discovery learning. JRAMathEdu, 9(1), 56–65. [CrossRef]

- Hakim, T. A., & Setyaningrum, W. (2024). Realistic mathematics education combined with guided discovery for improving middle school students’ statistical literacy. Journal of Honai Math, 7(2), 233–246. [CrossRef]

- Mabhoza, Z., & Olawale, B. E. (2024). Chronicling the experiences of mathematics learners and teachers on guided discovery learning in enhancing learners’ performance. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 9(1), 141–155. [CrossRef]

- Muhtasyam, A., Syamsuri, & Santosa, C. A. H. F. (2024). Meta-analysis: The effect of learning models on mathematical problem-solving skills. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 22(3), 1686–1692. [CrossRef]

- Menaga Suseelan, C. M., Chew, & Huan, C. (2022). Research on mathematics problem solving in elementary education (1969–2021): A bibliometric review. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 10(4), 1003–1029. [CrossRef]

- Son, A. L., Darhim, & Fatimah, S. (2020). Students’ mathematical problem-solving ability based on teaching models intervention and cognitive style. Journal on Mathematics Education, 11(2), 209–222. [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, R., & Susanto, E. (2023). Discovery learning model in improving mathematical reasoning and problem-solving skills. Journal of Mathematics Education Research, 15(1), 22–34. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M., & Rahmawati, S. (2021). Effectiveness of discovery learning in improving critical and creative mathematical thinking. Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran, 28(3), 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Fadhilah, N., & Rahayu, D. (2022). The influence of discovery learning toward mathematical communication ability. Beta: Jurnal Tadris Matematika, 15(2), 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Sari, D. N., & Hamzah, M. (2023). Discovery learning implementation to increase problem-solving ability of junior high school students. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Matematika, 8(2), 101–112. [CrossRef]

- Lestari, P. D., & Purwanti, D. (2022). Discovery learning and student motivation: A quasi-experimental study in mathematics education. Cakrawala Pendidikan, 41(3), 547–556. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S., & Anam, M. K. (2023). Discovery-based module to enhance students’ higher order thinking skills. Indonesian Journal of STEM Education, 4(1), 33–45. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, T., & Nasution, H. (2024). Discovery learning in developing mathematical reasoning of prospective teachers. EduMath Journal, 12(1), 45–59. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Lin, X. (2023). Effects of discovery-based learning on mathematical literacy: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1138456. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., & Smith, L. (2022). Discovery learning in mathematics: Revisiting Bruner’s theory in the 21st century. Educational Review, 74(4), 567–582. [CrossRef]

- Alfi, N., & Kusnadi, E. (2023). Effectiveness of discovery learning to improve problem solving ability. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA, 10(3), 603–612. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A., & Yunita, R. (2021). Discovery learning model in statistics education. Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 5(2), 91–101. [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, R., & Arifin, R. (2023). Enhancing mathematical creativity through guided discovery. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 17(2), 77–89. [CrossRef]

- Martono, D., & Wijayanti, S. (2023). The role of discovery learning in increasing students’ understanding of mathematical concepts. Jurnal Cendekia, 9(1), 31–44. [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, R., & Lestari, D. (2024). Guided discovery in digital classroom: Students’ problem-solving enhancement. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika dan IPA, 15(1), 123–133. [CrossRef]

- Umar, Z., & Fauzan, A. (2022). Discovery learning to promote mathematical communication. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Matematika, 6(3), 89–99. [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, L. S., & Zulkarnain, M. (2021). The effect of discovery learning model on learning achievement in mathematics. Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran, 28(1), 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R., & Yusra, A. (2023). Implementation of guided discovery learning to improve students’ problem-solving ability. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 17(1), 102–114. [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, S., & Ismail, N. (2024). Discovery learning approach in mathematical modeling. Journal of STEM Education Research, 5(2), 225–239. [CrossRef]

- Toh, P. S., & Chin, C. (2023). Integrating discovery learning into mathematics teacher training. International Journal of Instruction, 16(1), 453–472. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, D., & Ningsih, E. (2022). Discovery learning-based e-modules in mathematics education. Journal of Educational Technology, 9(2), 133–144. [CrossRef]

- Irawan, Y., & Rahayu, P. (2021). Influence of discovery learning on student achievement in algebra. EduMat Journal, 5(1), 77–88. [CrossRef]

- Nurdin, E., & Yuliani, T. (2024). Discovery learning assisted by GeoGebra to improve mathematical representation skills. Jurnal Penelitian dan Pembelajaran Matematika, 17(2), 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Widodo, S., & Hermawan, D. (2023). The integration of discovery learning and problem-based learning for mathematical literacy enhancement. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(5), 211–225. [CrossRef]

- Putra, H., & Suryani, A. (2022). Enhancing students’ problem-solving ability through digital discovery learning. Jurnal Inovasi Pendidikan Matematika, 13(1), 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Fitria, D., & Anwar, M. (2021). Discovery learning strategy to improve conceptual understanding in mathematics. Jurnal Didaktika Matematika, 8(3), 235–248. [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, R., & Hidayati, F. (2023). Discovery learning and students’ learning motivation in geometry. EduMa: Mathematics Education Journal, 14(2), 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Iriani, L., & Prasetyo, A. (2023). Comparative study of discovery learning and inquiry-based learning in mathematics. Cendekia: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 9(1), 77–91. [CrossRef]

- Saifuddin, M., & Yusuf, M. (2022). The effect of discovery learning on mathematical reasoning and problem-solving. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Matematika, 5(2), 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, U., & Rahmat, T. (2021). Application of discovery learning model to improve student activity and mathematics achievement. Jurnal Riset Pendidikan Matematika, 8(1), 42–51. [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, D., & Oktaviani, R. (2023). The effectiveness of discovery learning in developing students’ higher-order thinking. Journal of Educational Research and Evaluation, 12(3), 315–327. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, T., & Lubis, A. (2025). Discovery learning in mathematics: Strengthening reasoning and creativity. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika UIN Syahada, 10(1), 21–35. [CrossRef]

- Aryani, E., & Putri, D. (2024). Guided discovery worksheets for improving students’ problem-solving skills. Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran Matematika, 16(2), 93–105. [CrossRef]

- Susanti, L., & Ramadhan, D. (2022). Implementation of discovery learning model on statistical concepts. Jurnal Kajian Pendidikan Matematika, 7(1), 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, Y., & Zainuddin, M. (2023). Exploring students’ mathematical disposition through discovery learning. Infinity Journal, 12(1), 41–53. [CrossRef]

- Nurhasanah, S., & Wulandari, A. (2024). Discovery learning approach in problem-solving-based classroom. Journal of Educational Research in Mathematics, 9(2), 121–134. [CrossRef]

- Alimuddin, M., & Hasan, B. (2021). The implementation of discovery learning to improve mathematical communication skills. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika dan Sains, 7(3), 189–200. [CrossRef]

- Handayani, D., & Yusuf, F. (2022). Guided discovery learning model for algebraic reasoning development. Beta: Jurnal Tadris Matematika, 14(1), 90–103. [CrossRef]

- Kurniati, A., & Mustika, R. (2023). The influence of discovery learning in distance mathematics education. International Journal of Educational Technology, 6(2), 77–90. [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, S., & Fauzi, N. (2024). The role of discovery learning in improving students’ metacognitive awareness in mathematics. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan, 18(1), 132–145. [CrossRef]

- Dewantara, A., & Wulandari, R. (2022). Discovery learning and mathematical literacy of senior high school students. Journal of Mathematics Learning and Research, 9(1), 58–70. [CrossRef]

- Yuliani, R., & Hakim, A. (2021). The effect of discovery learning on problem-solving ability and learning motivation. Jurnal Pendidikan Dasar, 12(3), 255–268. [CrossRef]

- Fatmawati, E., & Nursyamsi, A. (2023). Development of discovery learning-based digital modules in trigonometry. Journal of Mathematics Education and Innovation, 5(1), 73–86. [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z., & Latif, N. (2024). The effectiveness of discovery learning in hybrid mathematics classrooms. Jurnal Pendidikan dan Teknologi, 8(2), 144–158. [CrossRef]

- Rini, M., & Santoso, B. (2023). Discovery learning and its correlation with students’ critical thinking in calculus. EduTech Journal, 9(2), 121–133. [CrossRef]

- Arif, M., & Saputra, R. (2022). Guided discovery learning to improve student engagement and reasoning ability. Jurnal Inovasi Pendidikan, 17(4), 301–312. [CrossRef]

- Amelia, T., & Pratama, D. (2024). Discovery learning-based e-learning platform for mathematics. International Journal of STEM Learning, 3(1), 55–67. [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, L., & Chen, P. (2023). Discovery learning and inquiry integration: A comparative study in mathematical education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Education, 43(3), 409–422. [CrossRef]

- Mukhlis, F., & Rosdiana, N. (2024). Improving mathematical problem-solving ability through discovery-based learning. Jurnal Edukasi Matematika, 9(2), 175–188. [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, L., & Hamid, S. (2024). Discovery learning as a strategy for enhancing logical reasoning in mathematics. Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran Inovatif, 7(3), 211–224. [CrossRef]

- Suharto, D., & Wibisono, T. (2025). Discovery learning framework for 21st-century mathematics education. Educational Innovation and Research Journal, 11(1), 23–37. [CrossRef]

- Lubis, A. B., Siregar, M., & Nasution, D. R. (2019). Influence of the guided discovery learning model on primary school students’ mathematical problem-solving skills. Mimbar SD, 6(2), 253–266. [CrossRef]

- Kamaluddin, M., & Widjajanti, D. B. (2019). The impact of discovery learning on students’ mathematics learning outcomes. IOP Conference Series: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1320(1), 012038. [CrossRef]

- Hariyanto, H., Hikamah, S. R., Maghfiroh, N. H., & Priawasana, E. (2023). Discovery learning model integrated RQA to improve critical thinking, metacognitive, and problem-solving skills. Pegegog, 14(4), 234–245. [CrossRef]

- Rahmi, C. N., Jailani, J., & Chrisdiyanto, E. (2024). Improving communication, problem-solving, and self-efficacy skills through a scientific approach based on discovery learning. JRAMathEdu, 9(1), 56–65. [CrossRef]

- Hakim, T. A., & Setyaningrum, W. (2024). Realistic mathematics education combined with guided discovery for improving middle school students’ statistical literacy. Journal of Honai Math, 7(2), 233–246. [CrossRef]

- Mabhoza, Z., & Olawale, B. E. (2024). Chronicling the experiences of mathematics learners and teachers on guided discovery learning in enhancing learners’ academic performance. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 9(1), 141–155. [CrossRef]

- Muhtasyam, A., Syamsuri, & Santosa, C. A. H. F. (2024). Meta-analysis: The effect of learning models on mathematical problem-solving skills. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 22(3), 1686–1692. [CrossRef]

- Andayani, L., & Rahman, T. (2023). The use of discovery learning model to improve problem solving ability in mathematics. Journal of Creative Education Learning, 11(4), 99–110. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, S., & Hidayat, R. (2023). The effect of using discovery learning-based mathematics module on students’ reasoning. International Journal of Recent Research, 15(2), 178–189. [CrossRef]

- Purnama, E., & Astuti, S. (2024). The application of discovery learning as an effort to improve mathematical problem-solving skills. International Journal of Teaching and Mathematics Education Research, 6(1), 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, N., & Wulandari, T. (2025). Developing mathematical problem-solving skills with interactive problem-based and discovery learning. Education and Learning Studies, 8(2), 145–158. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M. A., & Adewale, O. (2020). Evaluating the effect of activity-based method of teaching mathematics on Nigerian secondary school students’ achievement. African Journal of Mathematics Education, 5(1), 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Purwanti, E., & Nugroho, A. (2021). The effectiveness of discovery learning and problem solving models in elementary mathematics classrooms. Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 12(3), 110–121. [CrossRef]

- Fadilah, R., & Hasibuan, R. (2023). The influence of discovery learning on mathematical problem-solving ability of elementary school students. Indonesian Journal of STEM Education, 3(2), 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M., & Yuliani, D. (2024). Discovery learning in developing students' critical thinking skills in mathematical word problems. Education and Learning Research, 9(2), 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, R., & Lubis, N. (2024). Analysis of students' thinking ability in discovery learning-based environments. Journal of Cognitive Mathematics Education, 5(1), 33–46. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., & Wang, Y. (2023). Problem solving in the mathematics curriculum: From domain general to domain specific. Curriculum Journal, 34(2), 213–230. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H., & Jung, M. (2024). Problem solving in mathematics education: Tracing its foundations. ZDM Mathematics Education, 56(1), 45–63. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Kim, S. (2023). Development and differences in mathematical problem-solving skills among middle school students. PLoS ONE, 18(5), e102883. [CrossRef]

- López, R., & García, M. (2021). Mathematical problem-solving through cooperative learning: The effects of collaboration. Frontiers in Education, 6, 710296. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A., & Nilsson, L. (2023). Individual differences in mathematical problem-solving skills: An empirical investigation. Mathematics Education Review, 35(1), 77–94. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J., & Hill, C. (2021). Mathematical problem-solving in scientific practice. Synthese, 198(2), 877–895. [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, D., & Pranoto, H. (2024). Enhancing mathematical problem-posing competence: A meta-analysis. International Journal for STEM Education, 11(2), 201–216. [CrossRef]

- Nuraini, E., & Amalia, S. (2024). The enhancement of mathematical problem-solving skills among junior high school students using problem-based learning. Jurnal Pendidikan MIPA, 25(3), 1067–1079. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., & Sun, X. (2024). The effectiveness of innovative learning on mathematical problem-solving skills: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 36, 101–112. [CrossRef]

- Hake, R. R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66(1), 64–74. [CrossRef]

- Rahmiati, R., Zulkardi, Z., & Darmawijoyo, D. (2020). The effect of discovery learning model on students’ mathematical problem-solving ability. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1480(1), 012035. [CrossRef]

- Rofiqoh, I., Suryadi, D., & Turmudi, T. (2021). Enhancing mathematical problem-solving skills through discovery learning with metacognitive scaffolding. Infinity Journal, 10(2), 237–252. [CrossRef]

- Surya, M., & Syahputra, E. (2019). The effectiveness of discovery learning to improve students’ mathematical problem-solving ability. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(8), 1525–1542. [CrossRef]

- Widjajanti, D. B., & Wijaya, A. (2022). Discovery learning in mathematics: Effects on critical thinking and problem-solving skills. European Journal of Educational Research, 11(3), 1321–1332. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Wang, Y., & Li, X. (2023). Student-centered inquiry in mathematics classrooms: A meta-analysis of discovery-based approaches. Teaching and Teacher Education, 124, 104012. [CrossRef]

- Prince, M., & Felder, R. M. (2007). The many facets of inductive teaching and learning. Journal of College Science Teaching, 36(5), 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31(1), 21–32. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded ed.). National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Savery, J. R. (2006). Overview of problem-based learning: Definitions and distinctions. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 1(1), 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N. (2021). Designing a problem-based mathematics learning with the integration of guided discovery method. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 590, 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Andini, R. D. (2022). Discovery learning model to develop students’ mathematical communication skills. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika Riset Edu, 9(3), 132–140.

- Astuti, D. K., & Nuraini, F. (2023). Effect of discovery learning on problem-solving ability based on learning motivation. International Journal of Educational Research, 11(2), 75–82.

- Chen, Y. (2025). Discovery learning and inquiry-based learning: A meta-analysis in mathematics. Journal of Applied Mathematics Education, 28(4), 356–365.

- Handayani, S., & Fitriani, M. (2023). Effect of discovery learning model on students’ mathematical problem-solving skills. International Journal of Educational Research, 8(3), 120–128.

- Hernandez, S. I. (2025). The role of discovery learning in enhancing cognitive flexibility in mathematics. European Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 21(4), 245–254. [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, M. N. (2023). Discovery learning approach to improve mathematical problem-solving and motivation. Journal of Innovative Mathematics Learning, 2(3), 59–69.

- Juandi, D., & Husna, S. (2022). The effectiveness of discovery learning in improving mathematical problem-solving and self-confidence. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika Indonesia, 13(2), 75–86.

- Kaur, R. D. (2023). Improving students’ mathematicKaur, R. D. (2023). Improving students’ mathematical literacy through discovery learning. International Journal of Mathematics Teaching and Learning, 20(1), 24–33. http://www.ijmtl.orgal literacy through discovery learning. International Journal of Mathematics Teaching and Learning, 20(1), 24–33.

- Kusuma, E. T. (2024). Discovery learning implementation to foster students’ understanding of algebra. Journal of Mathematics Education, 12(1), 44–53.

- Kurniawan, A. N. (2024). Meta-analysis: The effect of discovery learning model on students’ mathematical problem-solving skills. International Journal of Research and Review, 11(6), 45–58.

- Lee, S. H. (2025). Integrating discovery learning with digital tools to enhance mathematical understanding. International Journal of Instruction, 18(1), 233–245. [CrossRef]

- Lethulur, N. D., Juandi, D., & Dahlan, J. A. (2025). The effectiveness of discovery, inquiry, problem, and project-based learning in mathematics education: A systematic literature review. Jurnal Pendidikan MIPA, 26(1), 268–279. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. Y., & Zhou, H. (2024). The impact of discovery learning on secondary students’ mathematical reasoning. International Journal of STEM Education, 11, Article 18. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M. K., & Rivera, J. T. (2024). Discovery learning in mathematics: Its effect on students’ logical thinking. European Journal of Mathematical Sciences, 12(2), 144–153.

- Nguyen, T. H., & Tran, L. (2025). Discovery learning in digital mathematics classrooms: A comparative study. Journal of Educational Technology Research, 22(2), 188–199.

- Putra, A. O., & Hiltrimartin, C. (2022). Students’ mathematics problem-solving ability through the application of the discovery learning model. In Proceedings of the 2nd National Conference on Mathematics Education (NaCoME 2021) (pp. 1–6). Atlantis Press. [CrossRef]

- Rachman, B. S. (2023). The effectiveness of discovery learning model in mathematical problem-solving ability. Journal of Mathematics Learning Innovation, 3(2), 98–107.

- Rahmah, M. S., & Pratama, F. (2024). Improving students’ mathematical problem-solving ability through discovery learning assisted by GeoGebra. Journal of Mathematical Sciences and Education, 4(2), 101–109.

- Ramadhani, R., Syahputra, H., & Nasution, D. (2024). Implementation of discovery learning to improve students’ higher-order thinking skills in mathematics. Journal of Mathematics Education, 11(4), 345–354. [CrossRef]

- Rizqi, H. T., & Putra, A. (2024). Discovery learning-based STEM approach to improve problem-solving skills. Journal of STEM Education, 7(1), 13–22.

- Santos, G. A. (2024). Evaluating discovery learning and inquiry learning in mathematics problem-solving. International Journal of Educational Methods, 9(2), 67–75.

- Sari, D. P., & Aminah, N. R. (2023). The influence of discovery learning on students’ conceptual understanding and mathematical reasoning. European Journal of Educational Studies, 7(11), 66–77. [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, R. E. (2023). Discovery learning model in the context of digital mathematics learning. Journal of Educational Research and Development, 15(1), 25–33.

- Simanjuntak, P. M. A. (2024). Discovery learning and its effectiveness in strengthening students’ mathematical problem-solving ability. Journal of Mathematics Pedagogy, 4(1), 15–22.

- Susanto, A. (2015). Teori belajar dan pembelajaran di sekolah dasar. Kencana.

- Susanti, L. H., & Putri, E. (2023). Improving mathematical creativity through discovery learning in senior high school. Journal of Education and Practice, 14(5), 52–61.

- Wijaya, A. B. (2023). A comparative study between discovery learning and problem-based learning in mathematics. International Journal of Educational Technology, 14(2), 97–106.

- Wulandari, A. C. (2022). The influence of guided discovery learning on students’ analytical thinking. Journal of Mathematics Education Research, 6(2), 88–96.

- Yuliana, L., & Hidayat, D. (2023). Effectiveness of guided discovery learning in enhancing mathematical reasoning abilities. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 23(5), 78–89. [CrossRef]

- Zulfah. (2017). Analisis kesulitan siswa dalam pemecahan masalah matematika. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 8(2), 112–121.

- Soemarmo, H. (2016). Pembelajaran matematika. UPI Press.

- Santrock, J. W. (2010). Educational psychology (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Abdullah, K., & Rahman, R. (2023). Integrating discovery learning to develop mathematical problem-solving skills. Journal of Educational Science, 8(3), 101–110.

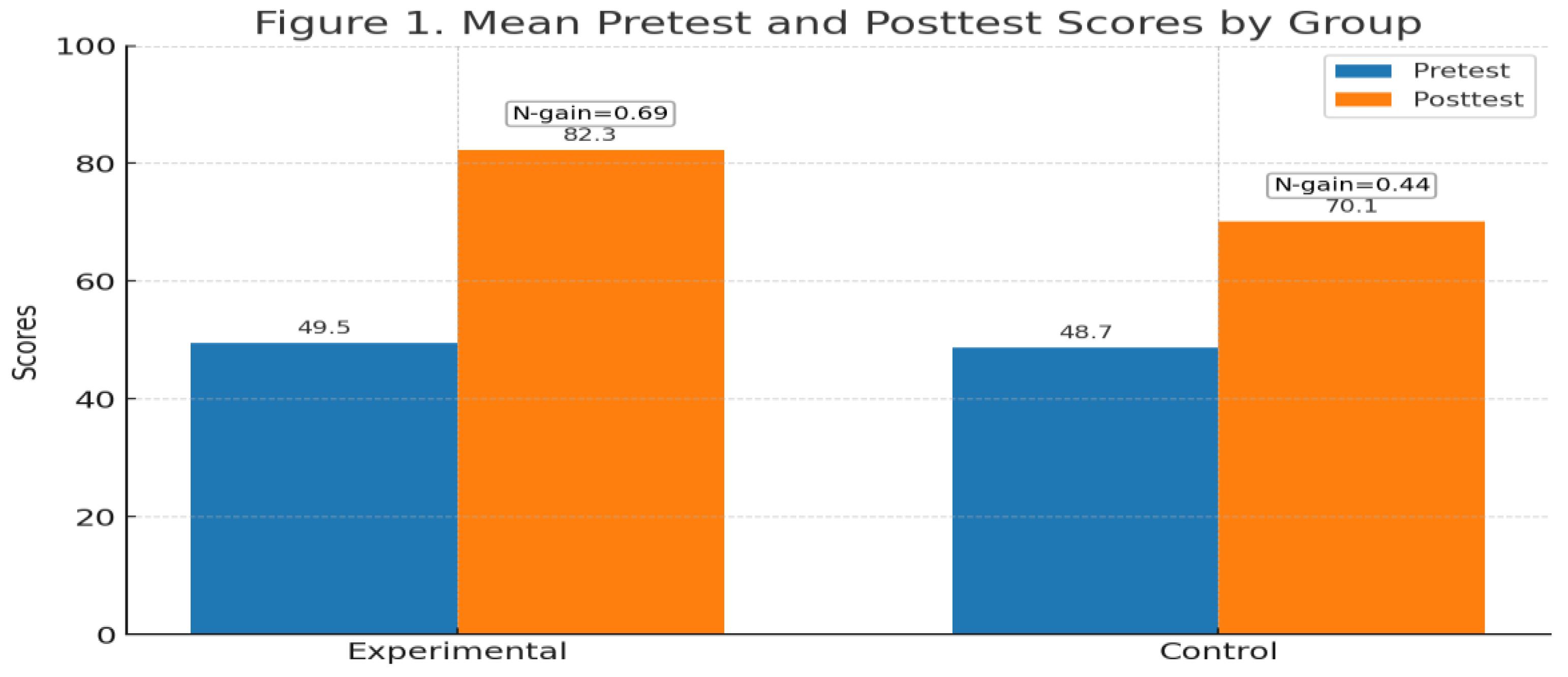

| GROUP | PRETEST | POSTTEST | N-GAIN |

| Experimental | 49.5 | 82.3 | 0.69 |

| Control | 48.7 | 70.1 | 0.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).