Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

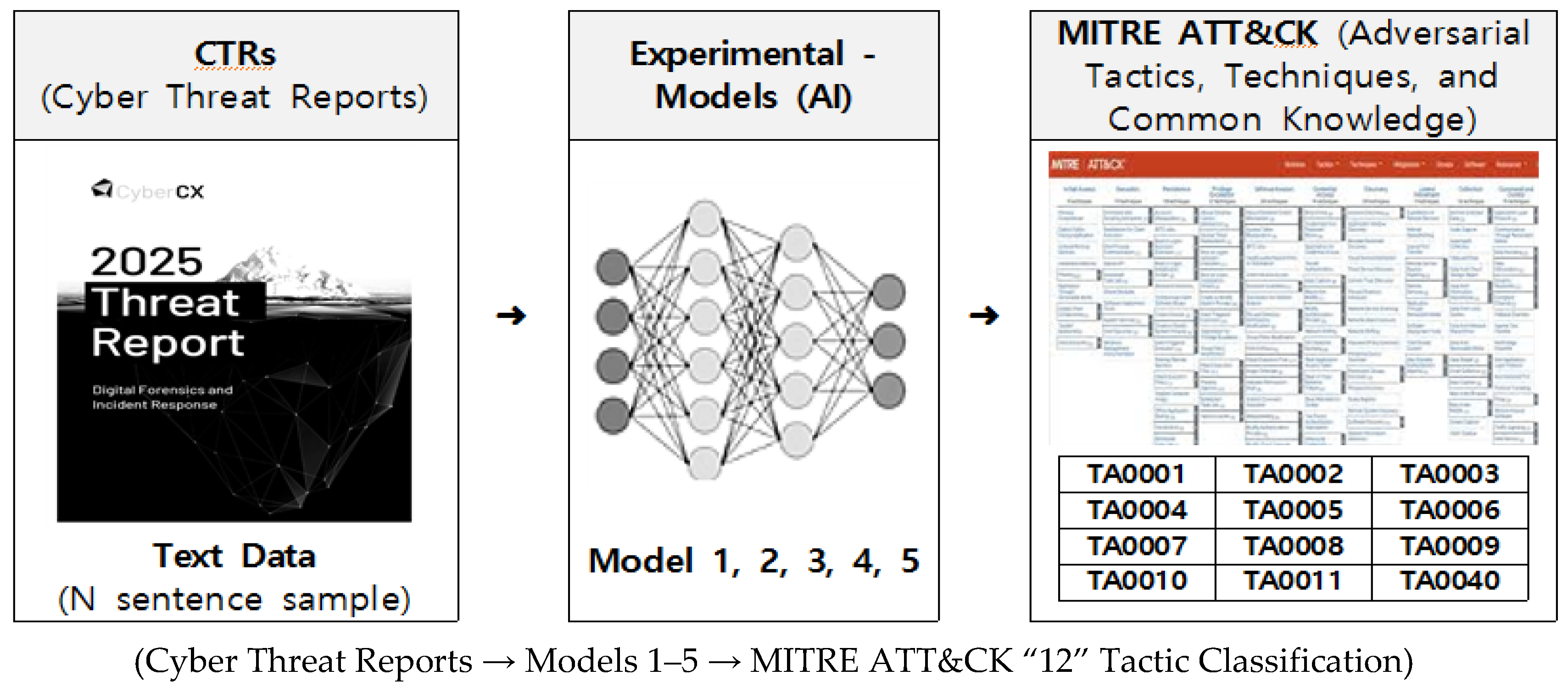

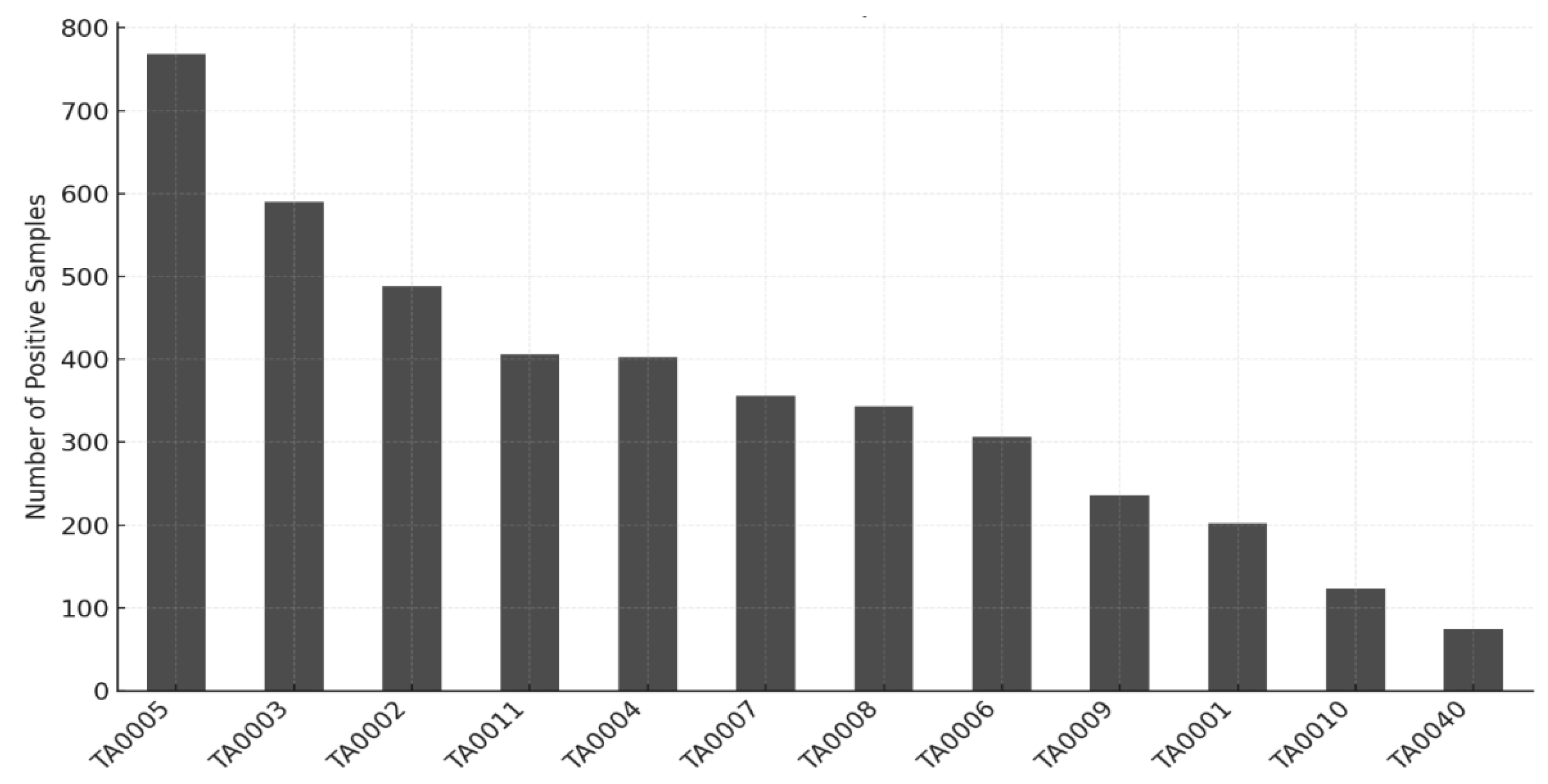

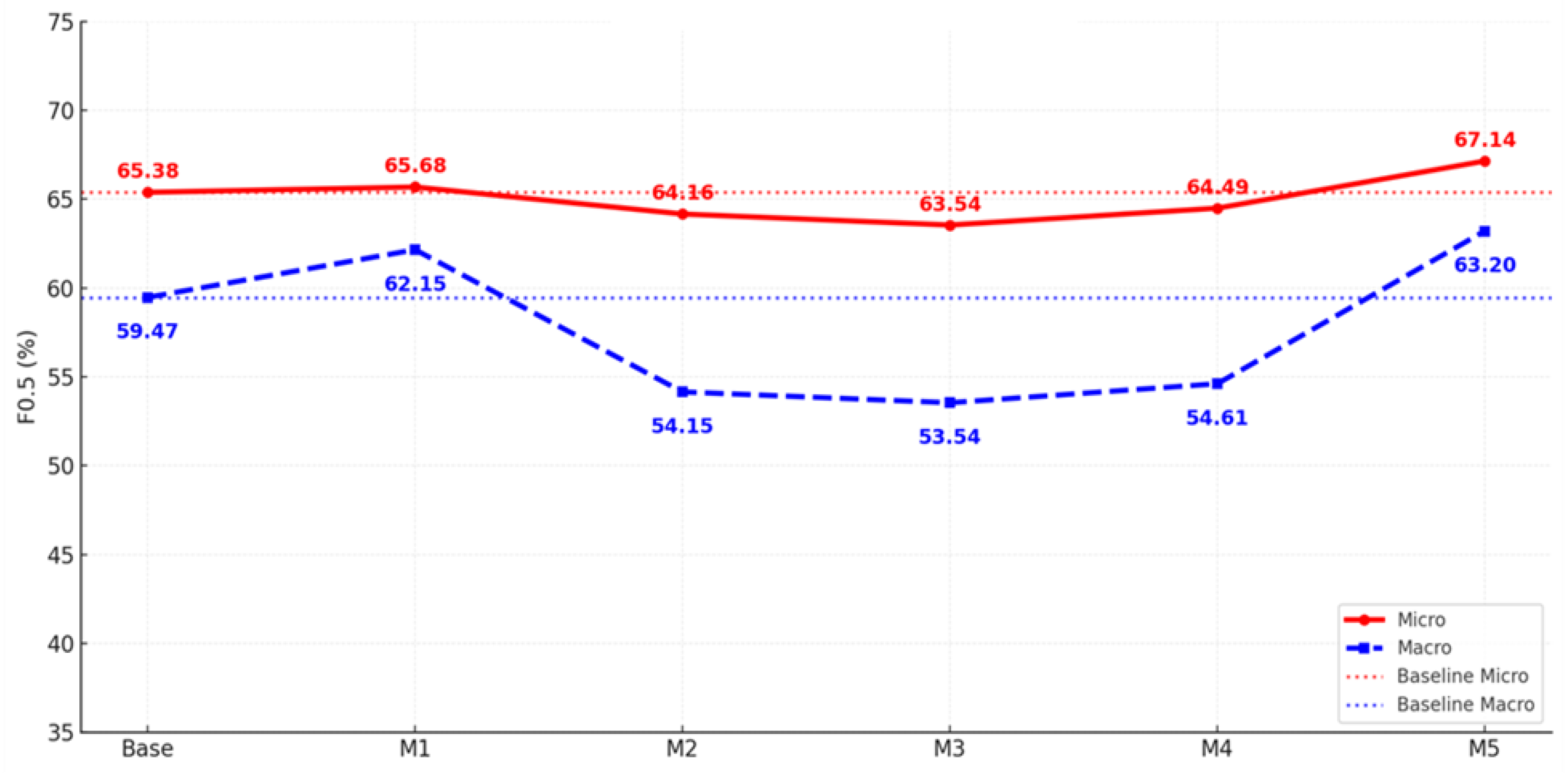

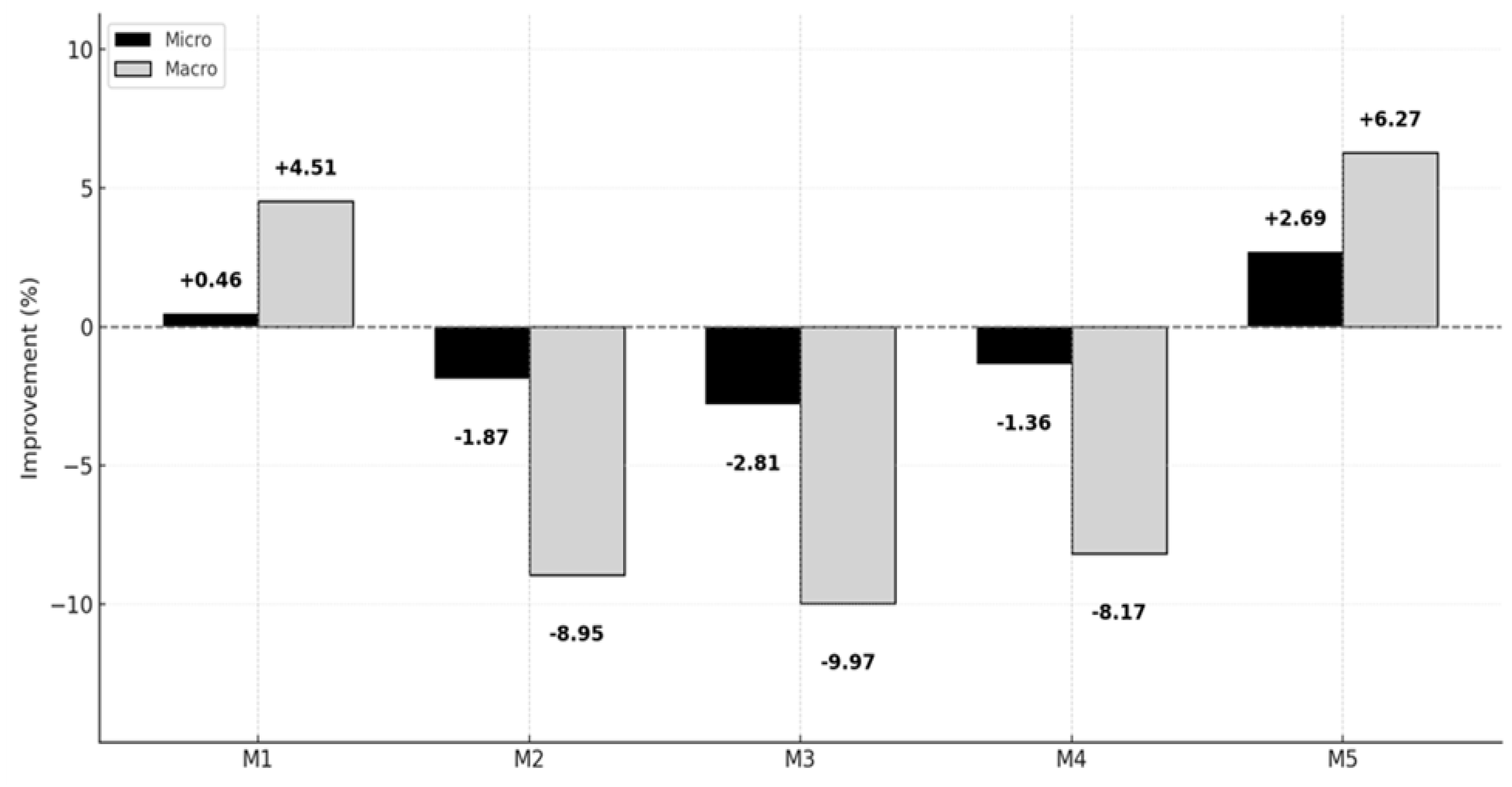

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) reports are key resources for identifying the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) of hackers and hacking groups. However, these reports are lengthy and unstructured, presenting limitations for automatic mapping to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. In this study, we designed and compared the performance of five hybrid classification models concatenating statistical-based features (TF-IDF), transformer-based contextual embeddings (BERT, ModernBERT), and topic-based representations (BERTopic) to automatically classify CTI reports into 12 ATT&CK tactic categories. Experiments using the rcATT dataset, comprising 1,490 public threat reports, showed that the model concatenating TF-IDF and ModernBERT achieved a micro-precision of 72.25%, demonstrating a 10.07 percentage point improvement in detection precision compared to the baseline paper. Furthermore, the model concatenating TF-IDF and BERTopic achieved a micro F₀.₅ of 67.14% and a macro F₀.₅ of 63.20%, representing a 6.27 percentage point improvement over the baseline paper, significantly enhancing detection performance for imbalanced classes and rare tactics. Academically, this study demonstrates that a hybrid approach integrating statistical, contextual, and semantic information can simultaneously improve precision and balance compared to existing CTI analysis techniques. Industrially, it demonstrated the practical applicability of the model to enhance detection efficiency and reduce analyst workload in Security Operations Center (SOC), adversary emulation, and Threat-informed Defense environments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional Text Mining-Based Research

2.2. Transformer-Based Embedding Research

2.3. Topic Modeling and Hybrid Approach Research

2.4. Research Gaps and Distinctiveness of This Study

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design Overview

3.2. Dataset and Processing

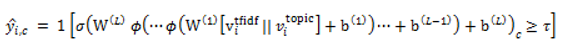

3.3. Model Structure

3.3.1. Model 1 : TF-IDF + MLP

|

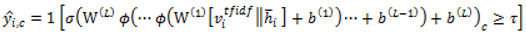

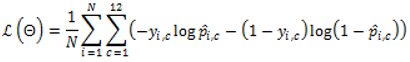

Algorithm (Model-1): Classification with TF-IDF + MLP Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020), 1,490 threat reports; TF-IDF vectorizer; MLP classifier; labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes 1. For each document ∈ D, perform preprocessing (tokenization, stopword removal). 2. Fit the TF-IDF vectorizer on the training set; transform train/validation (or test) sets to obtain sparse vectors . 3. Initialize the MLP classifier (e.g., hidden layers with ReLU; output dimension = 12). 4. Train the MLP on TF-IDF vectors and multi-label targets using BCE/BCEWithLogits loss. 5. For each validation/test document vector , feed it to the MLP to obtain logits . 6. Apply the sigmoid function to convert logits to probabilities ∈ . 7. Threshold each class probability at τ (default 0.5; optionally calibrated) to produce the predicted label set. 8. Optionally tune τ (global or per-class) on the validation set to optimize . 9. Evaluate using micro/macro precision, recall, and . |

3.3.2. Model 2 : BERT(sliding_Window) + MLP

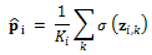

|

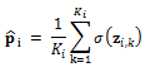

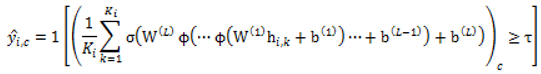

Algorithm (Model-2): BERT (sliding window) + MLP Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020), 1,490 threat reports; pretrained BERT; MLP classifier; window length L (e.g., 512 tokens), stride S (e.g., 256); labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes For each document ∈ D, prepare the input text (no stopword removal). Tokenize with the BERT tokenizer and split into overlapping windows of length L with stride S (pad/truncate as needed). Encode each window with BERT to obtain contextual embeddings; extract the [CLS] vector . Feed to an MLP to produce window-level logits ∈ . Convert window logits to probabilities via sigmoid and aggregate across windows (e.g., mean  pooling): pooling): Training: Optimize with Binary Cross-Entropy (either on aggregated or averaged over window logits). Inference: Apply threshold τ (default 0.5; optionally calibrated) to to obtain the predicted label set. Optionally tune L, S, pooling (mean/max/attention), and τ on the validation set to optimize . Evaluate using micro/macro precision, recall, and . |

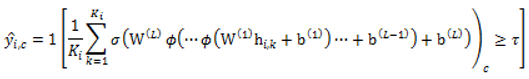

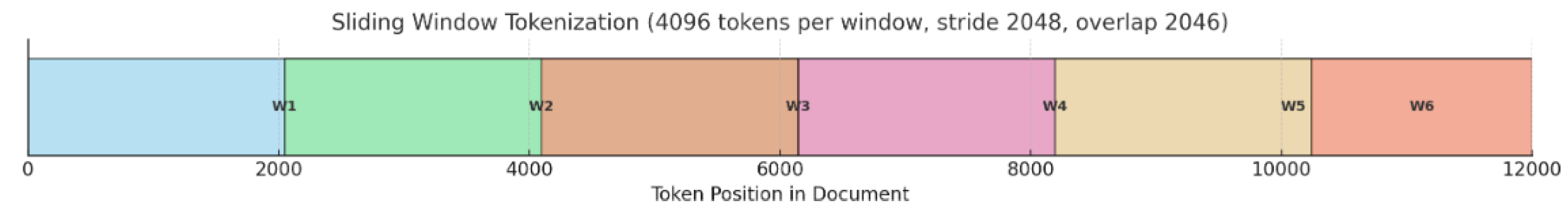

3.3.3. Model 3 : ModernBERT (sliding_Window) + MLP

|

Algorithm (Model-3): ModernBERT (sliding window) + MLP Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020), 1,490 threat reports; pretrained ModernBERT; MLP classifier; window length L (e.g., 4096 tokens), stride S (e.g., 2048); labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes For each document doc_i ∈ D, prepare the raw text (no stopword removal). Tokenize with the ModernBERT tokenizer and split into overlapping windows of length L with stride S (pad/truncate as needed). Encode each window with ModernBERT to obtain contextual embeddings; extract a window representation (e.g., [CLS] or mean-pooled). Feed into an MLP to produce window-level logits ∈ . Convert window logits to probabilities via sigmoid and aggregate across windows (e.g., mean pooling):  Training: Optimize with Binary Cross-Entropy (either on aggregated or averaged over window logits). Inference: Apply threshold τ (default 0.5; optionally calibrated) to to obtain the predicted label set. Optionally tune L, S, pooling strategy (mean/max/attention), and τ on the validation set to optimize . Evaluate using micro/macro precision, recall, and . |

3.3.4. Model 4 : TF-IDF + ModernBERT (sliding_Window) + MLP

|

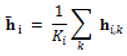

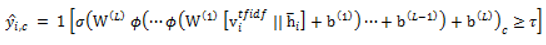

Algorithm (Model-4): TF-IDF + ModernBERT (sliding window) + MLP Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020), 1,490 threat reports; TF-IDF vectorizer; pretrained ModernBERT; MLP classifier; window length L (e.g., 4096), stride S (e.g., 2048); labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes For each document ∈ D, use the raw text (no stopword removal). Fit the TF-IDF vectorizer on the training set; transform train/validation (or test) sets to obtain sparse vectors . Tokenize with the ModernBERT tokenizer and split into overlapping windows of length L with stride S (pad/truncate as needed). Encode each window with ModernBERT to get window representations (e.g., [CLS] or mean-pooled). Aggregate window representations to a document embedding: (or attention pooling)  Concatenate features to form the fused input (optionally reduce TF-IDF dimension via SVD). Feed to the MLP to obtain logits ∈ ; apply sigmoid to get probabilities ∈ . Threshold each class probability at τ (default 0.5; optionally calibrated per class) to produce the predicted label set. Evaluate using micro/macro precision, recall, and (tune L, S, pooling, SVD rank, and τ on the validation set to optimize . |

3.3.5. Model 5 : TF-IDF + BERTopic + MLP

|

Algorithm (Model-5): TF-IDF + BERTopic + MLP Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020), 1,490 threat reports; TF-IDF vectorizer; BERTopic model; MLP classifier; labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes For each document ∈ D, prepare the raw text for two parallel feature paths. TF-IDF path: Fit the TF-IDF vectorizer on the training set; transform train/validation (or test) sets to obtain sparse vectors . BERTopic path (with stopword removal): tokenize and remove stopwords, then compute embeddings (e.g., sentence-transformer), apply BERTopic to assign a topic; derive a topic feature (one-hot or topic embedding). Concatenate features to form the fused input (optionally reduce TF-IDF with SVD before fusion). Feed into the MLP to produce logits ∈ . Apply the sigmoid function to obtain probabilities ∈ . Threshold each class probability at τ (default 0.5; optionally calibrated or per-class) to generate the predicted label set. Train with Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE/BCEWithLogits), optionally using class weights or focal loss for imbalance. Evaluate using micro/macro precision, recall, and . |

3.4. Document-Level Result Integration and Evaluation Method

3.5. Positioning of Comparative Research

4. Data Analysis and Critical Discussion

4.1. Experiment Purpose and Structure

4.2. Baseline Models for Comparison

4.3. Experimental Design of This Study

4.4. Experimental Results

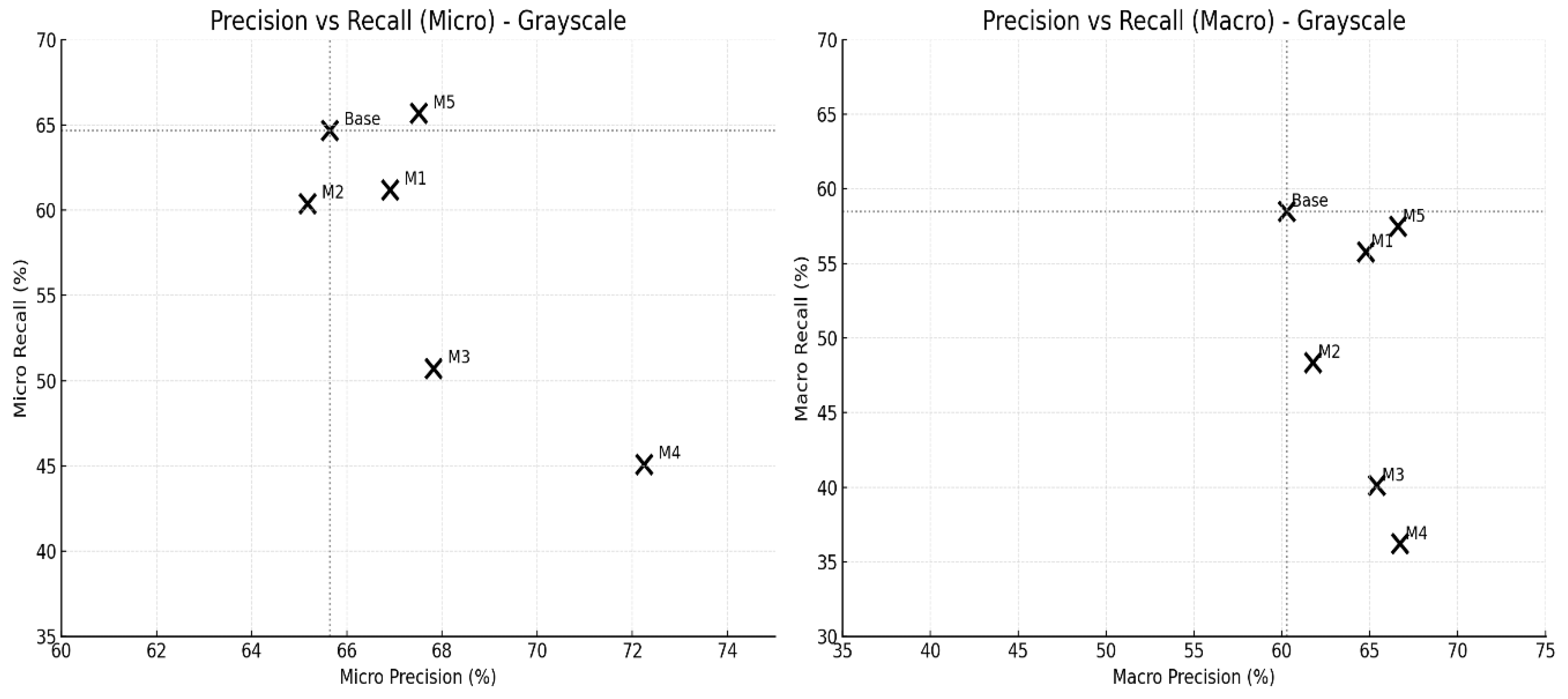

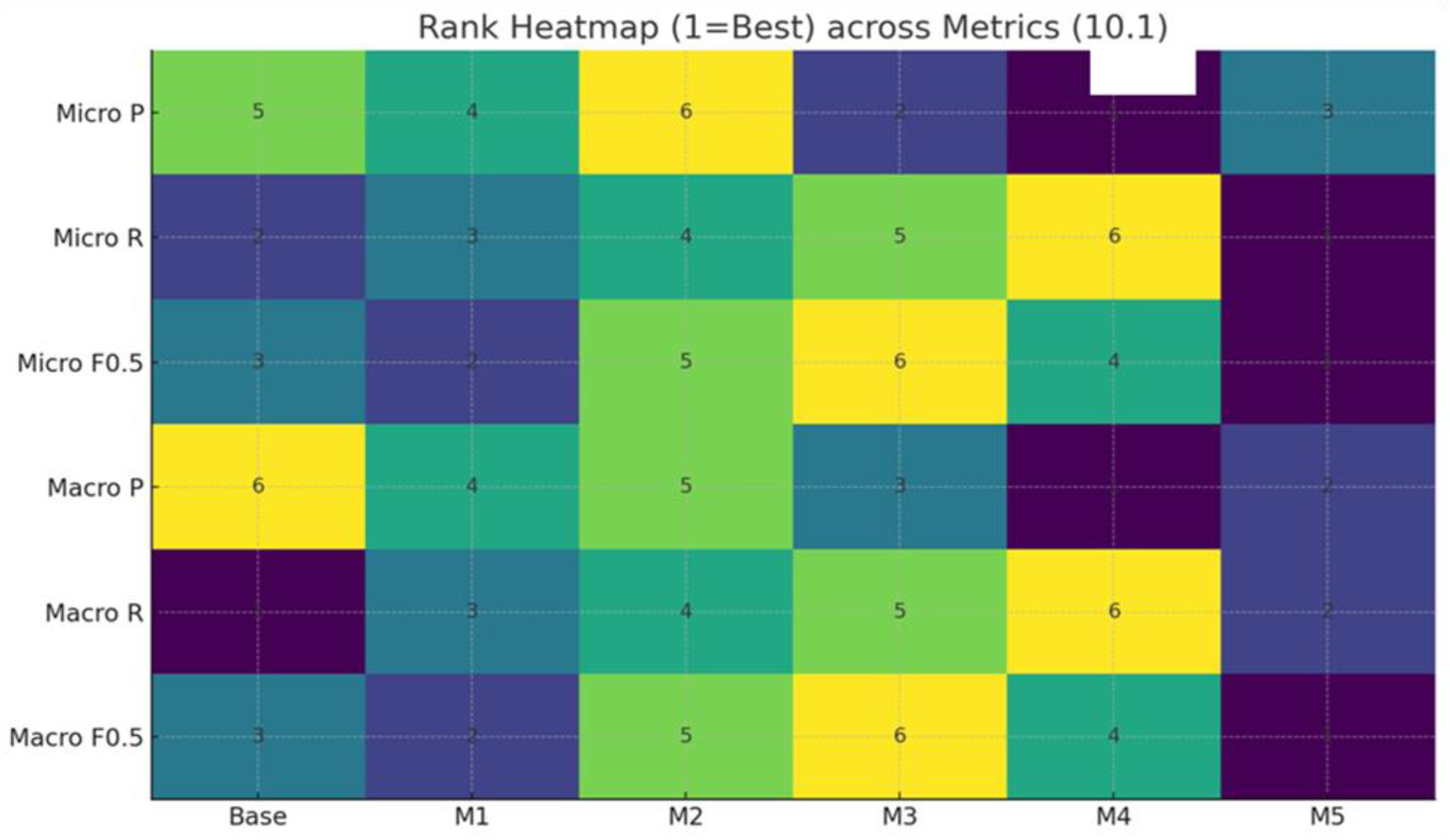

4.5. Interpretation of Results

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

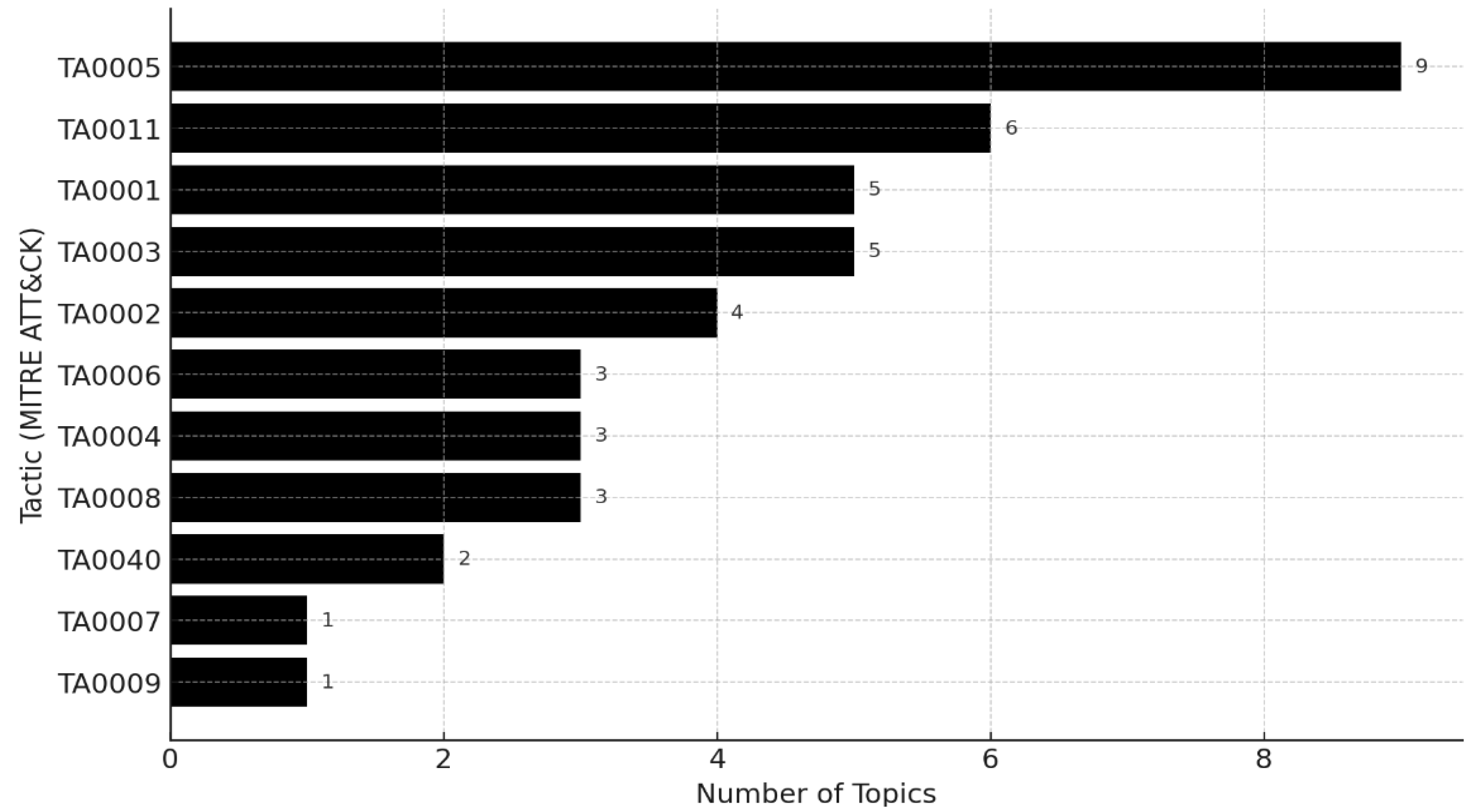

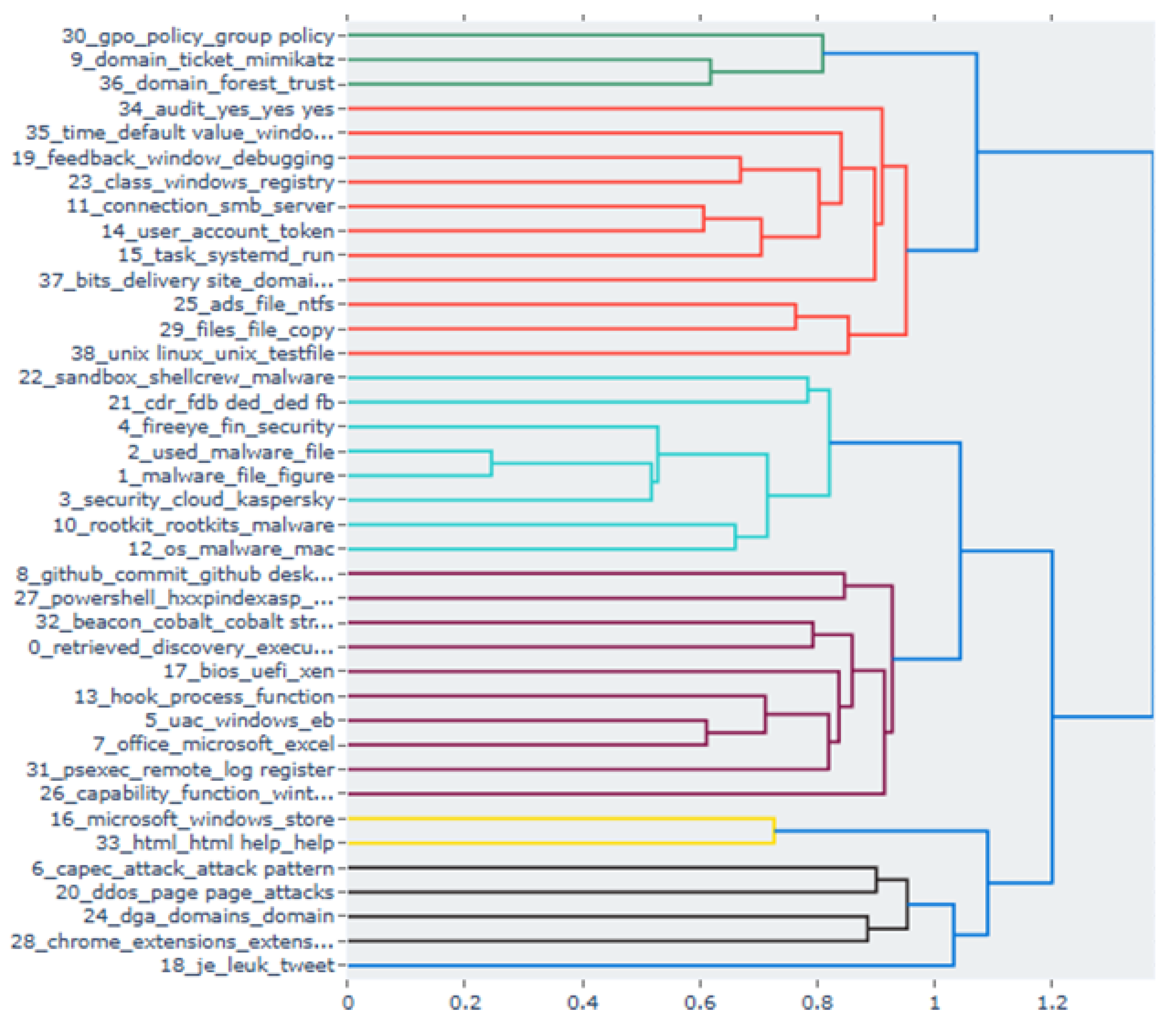

Appendix A. BERTopic Cluster Analysis of Model 5 (Based on Information Security Technology)

| Topic | Key Keywords | Mapped Tactic | Confidence Level | Supporting Evidence |

| 0 | retrieved, discovery, execution | TA0001 /2 /6 /7 /11 | High | 'discovery' keyword is directly associated with reconnaissance tactics |

| 1 | malware, file, microsoft | TA0005- | Low | Generic malware keywords, Difficulty in specifying tactics |

| 2 | used, malware, file | - | Low | APT/File Context, No Explicit Tactic Indicators |

| 3 | security, cloud, kaspersky | - | Low | Security vendor–related context |

| 4 | uac, windows, dll | TA0004 /5 | Medium ~ High |

UAC bypass → privilege escalation |

| 5 | office, macros, excel | TA0001 /2 /6 /7 /11 | High | Macro execution = initial access / execution |

| 6 | github, commit, download | TA0001 /3 /10 | Medium | Potential intrusion via public repositories / downloads |

| 7 | capec, attack_pattern | - | Low | Attack pattern literature |

| 8 | fireeye, fin, apt | - | Low | Vendor information |

| 9 | domain_ticket, mimikatz, kerberos | TA0001 /2 /6 /7 /11 | Very High | Mimikatz = representative tool for credential theft |

| 10 | rootkit, malware | TA0005 | High | Rootkit = detection evasion |

| 11 | connection, smb, server | TA0003 /6 / 8 | High | SMB connection = lateral movement |

| 12 | os_malware_mac, wirulker | TA0005 / TA0040 | 보통 | macOS malware concealment |

| 13 | hook, process, function | TA0001 /2/ 5 / 6 /7 /11 | High | Process hooking / injection |

| 14 | user_account_token, lsa | TA0003 /6 /8 /14 | High | Token / LSA related = credential theft |

| 15 | task, systemd, run, schtasks | TA0003 /6 /8 /14 | High | Scheduled tasks / systemd |

| 16 | microsoft_windows_store | - | Low | General platform keywords |

| 17 | bios, uefi, xen | TA0004 / TA0003 | Medium | Firmware / Boot-Level Privilege Escalation |

| 18 | je_leuk_tweet, op, meer | - | Low | Social / noise |

| 19 | feedback_window_debugging | TA0003 /5 /6 /7 /8 | Medium | Debugging-related reconnaissance / anti-debugging |

| 20 | ddos, page, attacks | TA0040 | High | DDoS = denial of service |

| 21 | cdr, fdb, ded, fd | - | Low | File / forensic |

| 22 | sandbox, shellcrew, trojan | TA0005 | High | Sandbox evasion |

| 23 | class, windows, registry, atom | TA0003 /5 /6 /8 | Medium | Registry manipulation |

| 24 | dga, domains, domain | TA0011 | Very High | DGA = C2 persistence |

| 25 | ads, file_ntfs, stream | TA0005 | Medium | Alternate Data Streams 은폐 |

| 26 | capability_function, wintrustdll | TA0005 | Medium | WinTrust signature manipulation |

| 27 | powershell, script, hxxp | TA0001 /2 /6 /11 | High | PowerShell execution |

| 28 | chrome, extensions, webstore | TA0001 /3 /10 | Medium | Intrusion / persistence via malicious extensions |

| 29 | files, file_copy, executable | TA0001 /3 /9 /10 | Medium | File collection |

| 30 | gpo, policy, group policy | TA0003 /6 /8 | Medium ~ High |

Policy / GPO manipulation |

| 31 | psexec, remote, log register | TA0003 /6 /8 | Very High | PsExec = lateral movement |

| 32 | cobalt_strike, beacon | TA0011 | Very High | Cobalt Strike = C2 tool |

| 33 | html, html_help | - | Low | Formal Keywords |

| 34 | audit_yes_yes, policy | - | Low | Noise / logs |

| 35 | time_default_value, windows time | TA0003 /5 /6 /8 | Medium | Timer-based persistence |

| 36 | domain_forest_trust | TA0001 /3 /4 /8 /10 | Medium | Abuse of forest trust |

| 37 | bits_delivery, malware_delivery_site | TA0001 /3 /10 /11 /40 | Medium | BITS job = payload / C2 |

| 38 | unix, linux, chmod | TA0002 | Medium | Unix shell execution |

References

- MITRE Corporation. MITRE ATT&CK Framework; Bedford, MA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Center for Threat-Informed Defense. Threat Report ATT&CK Mapper (TRAM); MITRE CTID Project, 2025. Available online: https://ctid.mitre.org/projects/threat-report-attck-mapper-tram/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Legoy, V.; Caselli, M.; Seifert, C.; Peter, A. Automated Retrieval of ATT&CK Tactics and Techniques for Cyber Threat Reports. Comput. Secur. 2020, 93, 101796. [CrossRef]

- Lange, L.; Müller, M.; Torbati, G.H.; Milchevski, D.; Grau, P.; Pujari, S.; Friedrich, A. AnnoCTR: A Dataset for Detecting and Linking Entities, Tactics, and Techniques in Cyber Threat Reports. Electronics 2024, 13(15), 3190. [CrossRef]

- Lange, L.; Müller, M.; Friedrich, A. AnnoCTR (Extended); Dataset Companion Release, 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/1234567 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Branescu, C.; et al. Automated Mapping of CVE to MITRE ATT&CK Tactics. Information 2024, 15(4), 214. [CrossRef]

- Arazzi, M.; Arikkat, D.R.; Nicolazzo, S.; Nocera, A.; Conti, M. NLP-Based Techniques for Cyber Threat Intelligence. Comput. Secur. 2023, 126, 103078. [CrossRef]

- Büchel, M.; Paladini, T.; Longari, S.; Carminati, M.; Zanero, S.; et al. SoK: Automated TTP Extraction from CTI Reports—Are We There Yet? Proc. USENIX Security Symp. 2025, Seattle, WA, USA. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity25 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Li, L.; Huang, C.; Chen, J. Automated Discovery and Mapping of ATT&CK Tactics and Techniques for Unstructured Cyber Threat Intelligence. Comput. Secur. 2024, 140, 103815. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Saha, B.; Maurya, V.; Shukla, S.K. TTPXHunter: Actionable Threat Intelligence Extraction from FinishedCyber Threat Reports. Digit. Threats 2024, 5, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Shu, H.; Kang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y. Malware2ATT&CK: Mapping Malware to ATT&CK Techniques.

- Comput. Secur. 2024, 140, 103772. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; et al. Leveraging LLMs to Correlate CVE and CTI with MITRE ATT&CK TTPs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.00878. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.00878 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Simonetto, S.; Rossi, M.; et al. Comprehensive Threat Analysis and Systematic Mapping of Vulnerabilities to MITRE ATT&CK. Proc. NLPAICS 2024, Lancaster, UK. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-XXX/NLPAICS2024.html (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Jo, H.; Lee, Y.; Shin, S. Vulcan: Automatic Extraction and Analysis of Cyber Threat Intelligence from Unstructured Text. Comput. Secur. 2022, 120, 102763. [CrossRef]

- Sorokoletova, E.; et al. Towards a Scalable AI-Driven Framework for Data-Independent CTI Extraction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.06239. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.06239 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Nguyen, T.; Pham, N.; Le, H. Towards Effective Identification of Attack Techniques in CTI Reports Using LLMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.03147. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.03147 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Tsang, C.M.; Luong, P.; Tsoi, K.H.; Hui, L.C.K.; Yiu, S.M. A Unifying Framework with GPT-3.5, BERTopic, and LLM-as-Judge for Cybersecurity Intelligence. Proc. NLPAICS 2024, Lancaster, UK.

- Albarrak, M.; Pergola, G.; Jhumka, A. U-BERTopic: Urgency-Aware BERT-Topic Modeling for Detecting Cybersecurity Issues. Proc. NLPAICS 2024, Lancaster, UK.

- Rani, N.; Saha, B.; Maurya, V.; Shukla, S.K. Topic Modeling-Based Prediction of Software Defects and Root Cause Using BERTopic. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11529. [CrossRef]

- Arreche, J.; et al. XAI-IDS: Toward an Explainable AI Framework for Intrusion Detection. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14(10), 4170. [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, I.; et al. A Versatile XAI-Based Framework for Efficient and Explainable Intrusion Detection Systems. Ann. Telecommun. 2025, 80, 633–646. [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Kostakos, V. HuntGPT: Integrating ML-Based Anomaly Detection and Explainable AI with LLMs. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16021. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.16021 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Tellache, M.; et al. Advancing Autonomous Incident Response: Leveraging LLMs and CTI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10677. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.10677 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Nguyen, T.; Pham, N. Large Language Models for Cyber Threat Hunting and SOC Automation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 144210–144225. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zhang, D. Generative Models for Cyber Threat Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57(3), 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Large Language Models for Cyber Security: A Systematic Literature Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.04760. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.04760 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Jaffal, N.O.; Janbi, A.; et al. Large Language Models in Cybersecurity: A Survey of Applications, Vulnerabilities, and Defenses. Digital 2025, 6(9), 216. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wei, H.; et al. Cyber-Attack Technique Classification Using Two-Stage Multimodal Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.18755. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.18755 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. Available online:.

- https://papers.nips.cc/paper/7181-attention-is-all-you-need.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proc. NAACL-HLT 2019, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The Long-Document Transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05150. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.05150 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Zaheer, M.; et al. BigBird: Transformers for Longer Sequences. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 17283–17297. Available online:.

- https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2020/hash/c8512d142a2d849725f31a9a7a361ab9-Abstract.html (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Warner, B.; et al. Smarter, Better, Faster, Longer: A Modern Bidirectional Encoder for Long-Context Finetuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.19458. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.19458 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural Topic Modeling with a Class-Based TF-IDF Procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.05794 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Reeves, A.; Calic, D.; Delfabbro, P. “Generic and Unusable”: Understanding Employee Perceptions of Cybersecurity Training and Advice Fatigue. Comput. Secur. 2023, 128, 103137.

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2023.103137. [CrossRef]

- Peltola, S. Threat Detection Analysis Using MITRE ATT&CK Framework. Comput. Secur. 2025, 137, 103854. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Shin, C.; Shin, S. Cyber Attack Group Classification Based on MITRE ATT&CK Model. J. Internet Comput. Serv. 2022, 23, 1–13. Available online: https://www.jics.or.kr/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Shin, C.; Choi, C. Cyberattack Goal Classification Based on MITRE ATT&CK: CIA Labeling. J. Internet Comput. Serv. 2022, 23, 15–26. Available online: https://www.jics.or.kr/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Husari, G.; Al-Shaer, E.; Ahmed, M.; Chu, B.; Niu, X. TTPDrill: Automatic and Accurate Extraction of Threat Actions from Unstructured CTI Text Sources. Proc. IEEE ICICS 2017, Beijing, China, 103–115. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. KnowCTI: Knowledge-Based Cyber Threat Intelligence Entity and Relation Extraction. Comput. Secur. 2024, 140, 103824. [CrossRef]

| No. of Win. (MAX_LENGTH = 4096) |

No. of Docs. | % | Doc. Len. (A4 p.) |

| 1 | 1153 | 77.38 | 8.2 |

| 2 | 178 | 11.95 | 16.4 |

| 3 | 67 | 4.5 | 24.6 |

| 4 | 41 | 2.75 | 32.8 |

| 5 | 18 | 1.21 | 40.9 |

| 6 | 15 | 1.01 | 49.1 |

| 7 | 4 | 0.27 | 57.3 |

| 8 | 5 | 0.34 | 65.5 |

| 9 | 3 | 0.2 | 73.7 |

| 11 | 1 | 0.07 | 90.1 |

| 12 | 1 | 0.07 | 98.3 |

| 13 | 1 | 0.07 | 106.4 |

| 14 | 1 | 0.07 | 114.6 |

| 16 | 2 | 0.13 | 131.0 |

| 총합 | 1490개 | 100 % |

| Tactic ID | Tactic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| TA0001 | Initial Access | Methods used by adversaries to gain an initial foothold within a network (e.g., phishing, exploiting public-facing applications). |

| TA0002 | Execution | Techniques that result in execution of adversary-controlled code on a local or remote system (e.g., PowerShell, command-line). |

| TA0003 | Persistence | Techniques that adversaries use to maintain their foothold (e.g., creating accounts, service registration, scheduled tasks). |

| TA0004 | Privilege Escalation | Techniques that allow adversaries to gain higher-level permissions (e.g., exploiting vulnerabilities, token manipulation). |

| TA0005 | Defense Evasion | Techniques used to evade detection and avoid defenses (e.g., obfuscation, rootkits, timestomping). |

| TA0006 | Credential Access | Techniques for stealing credentials such as passwords, hashes, or tokens (e.g., Mimikatz, credential dumping). |

| TA0007 | Discovery | Techniques adversaries use to gain knowledge about the system and internal network (e.g., network scanning, account discovery). |

| TA0008 | Lateral Movement | Techniques that enable moving through a network (e.g., PsExec, RDP, SMB exploitation). |

| TA0009 | Collection | Techniques used to gather information relevant to the adversary’s goals (e.g., keylogging, screen capture, file collection). |

| TA0010 | Exfiltration | Techniques used to exfiltrate collected data outside the victim environment (e.g., compression + upload, FTP, HTTP POST). |

| TA0011 | Command and Control | Techniques to communicate and control compromised assets via C2 channels (e.g., Cobalt Strike, beacons, DGA). |

| TA0040 | Impact | Techniques used to disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy business and operational processes (e.g., ransomware, wipers, DDoS). |

| Metric Avg. | Precision | Recall | F0.5 |

| Micro | 48.72% | 19.00% | 37.10% |

| Macro | 4.43% | 9.09% 1 | 4.93% |

| Metric Avg. | Precision | Recall | F0.5 |

| Micro | 65.64% | 64.69% | 65.38% |

| Macro | 60.26% | 58.50% 1 | 59.47% |

| Experimental Model | Configuration (Data Representation + Classifier) |

| Model-1 | TF-IDF + MLP |

| Model-2 | BERT + MLP |

| Model-3 | ModernBERT + MLP |

| Model-4 | TF-IDF + ModernBERT + MLP |

| Model-5 | TF-IDF + BERTopic + MLP |

| Experimental Model | Metric Avg.. | Precision (%) |

Imp. (%) |

Recall (%) |

Imp. (%) |

F0.5 (%) |

Imp. (%) |

||

| Category | Data Representation | Classifier | |||||||

| Base-line | TF-IDF | Linear SVC | Micro | 65.64 | 0.0 | 64.69 | 0.0 | 65.38 | 0.0 |

| Macro | 60.26 | 0.0 | 58.50 | 0.0 | 59.47 | 0.0 | |||

| Model-1 | TF-IDF | MLP | Micro | 66.91 | +1.93 | 61.19 | -5.41 | 65.68 | +0.46 |

| Macro | 64.78 | +7.5 | 55.80 | -4.62 | 62.15 | +4.51 | |||

| Model-2 | BERT | MLP | Micro | 65.17 | -0.72 | 60.40 | -6.63 | 64.16 | -1.87 |

| Macro | 61.77 | +2.51 | 48.38 | -17.3 | 54.15 | -8.95 | |||

| Model-3 | ModernBERT | MLP | Micro | 67.82 | +3.32 | 50.73 | -21.58 | 63.54 | -2.81 |

| Macro | 65.39 | +8.51 | 40.13 | -31.4 | 53.54 | -9.97 | |||

| Model-4 | TF-IDF + ModernBERT | MLP | Micro | 72.25 | +10.07 | 45.11 | -30.27 | 64.49 | -1.36 |

| Macro | 66.72 | +10.72 | 36.23 | -38.07 | 54.61 | -8.17 | |||

| Model-5 | TF-IDF + BERTopic | MLP | Micro | 67.51 | +2.85 | 65.69 | +1.55 | 67.14 | +2.69 |

| Macro | 66.59 | +10.5 | 57.49 | -1.73 | 63.20 | +6.27 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).