1. Introduction

The global construction industry is undergoing a technological renaissance, with digital construction methods such as Building Information Modeling [

1], Robotics [

2], and 3-Dimensional Concrete Printing [

3] reconfiguring the traditional paradigms of design, project delivery, and infrastructure development. 3DCP, an additive manufacturing technology, is the process of creating a physical object, in this case a structure, from 3D digital model in a layer-by-layer process [

4]. According to [

3], the technology offers unprecedented opportunities for automation, design flexibility, material efficiency, and sustainability. 3DCP holds particularly promises of addressing the housing and infrastructure deficits in developing countries [

5] by enabling faster, cost-effective, and environmentally responsive building solutions. [

6], reported that all over the world, 3DCP technology is being piloted and scaled across different sectors, from social housing to emergency shelter construction, industrial facilities, and aesthetic architectural expressions.

In the context of South Africa, 3DCP is increasingly attracting the interest of researchers, private firms, and government institutions. According to [

5], digital technology advancement promises solutions to the age-long problems of cost, time, and quality in building projects delivery. The successful development of South Africa’s first 3D printed house by the Centre for Sustainable Materials and Construction Technologies at the University of Johannesburg [

7] exemplifies the possibilities, momentum and suggests the practical feasibility of the technology within local conditions. Despite the promising developments, the technology is far from mainstream [

8]. The pathway from innovation to routine use is obstructed by a range of acceptance barriers [

3,

5] notwithstanding technological, regulatory, financial, as well as cultural challenges. For 3DCP to achieve meaningful uptake and impact the South African construction ecosystem, it is critical to understand how key stakeholders, particularly construction professionals and regulators perceive and engage with the technology.

While global studies on 3DCP have expanded over the past decade, there is a stack lack of empirical research addressing how the technology is received within developing country contexts. This shortcoming is probably marked by institutional complexity, uneven infrastructure, skills deficits, and slow regulatory reforms. In the South African context, the fragmented regulatory environment, high dependence on conventional construction practices, and limited public sector experimentation, create unique conditions that affect the acceptance of technology like 3DCP. Existing literature often examines 3DCP from a purely technical or economic perspective [

9], focusing on material properties [

10], printability [

11,

12], or comparative cost advantages [

13], without exploring how regulatory agencies and construction professionals perceive the risks, benefits, and readiness. Furthermore, many global acceptance studies deploy generic models such as the Technology Acceptance Model [

14] or the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [

15], without accounting for the institutional and policy environments that mediate acceptance in a real-world construction environment. The lack of integrated studies that combine professional attitude with regulatory considerations within the South African built environment leaves a critical gap. Without this understanding, efforts to scale 3DCP risk continuous failure due to misalignment between technological possibilities and regulatory, institutional, and cultural readiness.

The aim of this article is to evaluate the factors influencing the acceptance of 3D concrete printing in South Africa, based on insights from built environment professionals and regulatory bodies. To achieve this aim, the study is guided by the following specific objectives: assess the perceptions of construction professionals regarding the benefits, risks, and feasibility of 3DCP; investigate the current position and preparedness of regulatory agencies about the incorporation of 3DCP into building codes and standards; modify and apply the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology to a construction context by integrating variables such as regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness; and identify the key barriers and enablers affecting 3DCP technology acceptance, and recommend strategies to facilitate the responsible adoption of 3DCP technology.

This study provides a multi-stakeholder assessment of 3DCP acceptance in South Africa, focusing simultaneously on the professions and regulators. The study contributes original insights by extending the UTAUT model to include regulatory and infrastructural dimensions, thereby addressing the contextual factors often omitted in conventional technology acceptance research. More so, the study fills a methodological gap by employing a mixed-method approach that triangulates survey data, interview insights, and focus group findings [

16], offering a rich, robust and holistic view of the ecosystem surrounding 3DCP acceptance. The study originality also lies in the practical orientation. By aligning technological perceptions with regulatory priorities, the study informs actionable pathways for policy development, curriculum design, and industry experimentation. This is particularly important in a country like South Africa, where the construction sector must rapidly innovate to meet the rising pressure from urbanization, sustainability imperatives, and demand for affordable housing, without compromising quality and safety.

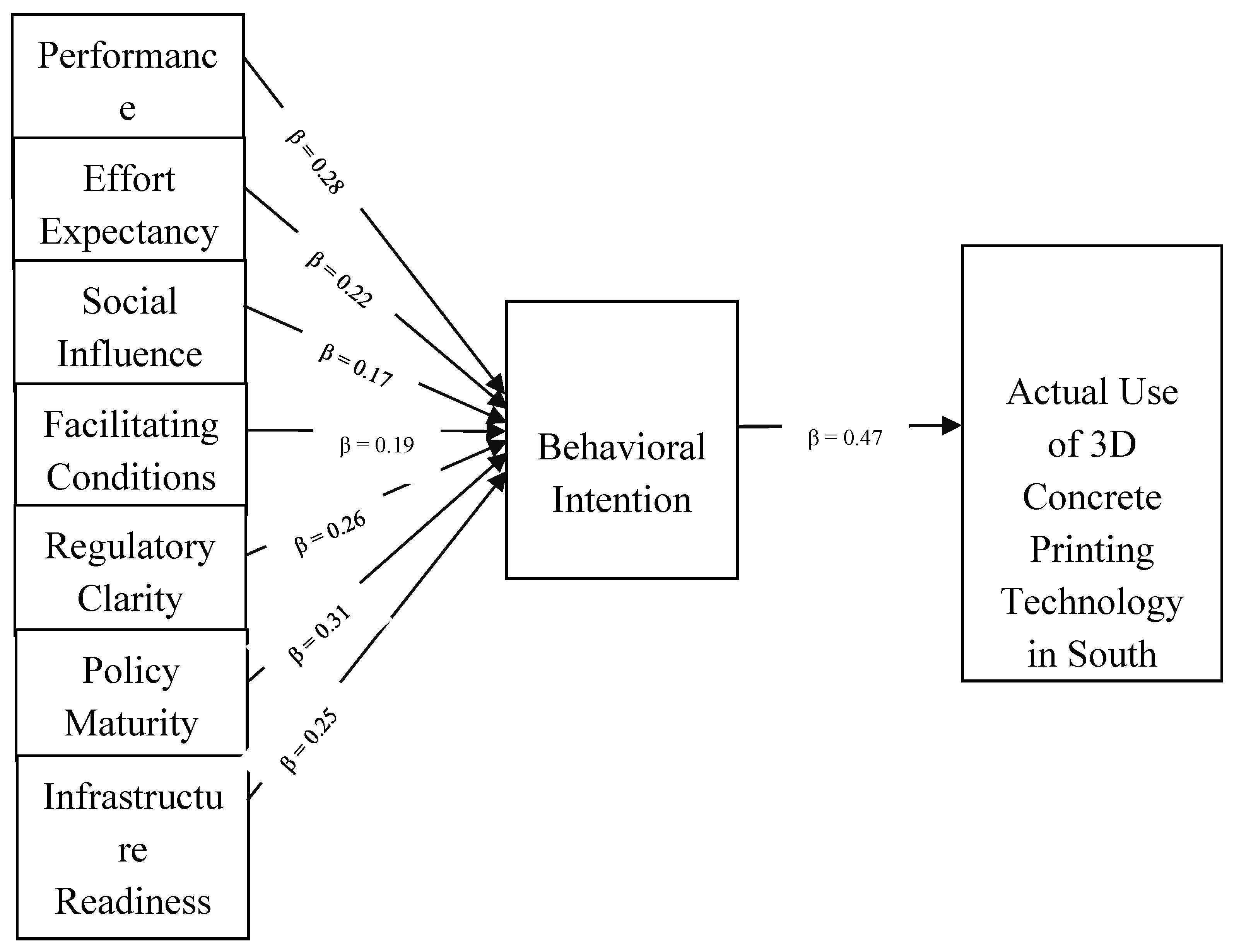

The study is grounded in theory. To frame the study, a modified UTAUT model [

17] served as the primary theoretical lens. While the original UTAUT model [

18] includes core constructs such as Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, Social Influence, and Facilitating Conditions, this study introduces three new constructs relevant to the South African construction context: Regulatory Clarity, Policy Maturity, and Infrastructure Readiness. These variables are essential to capture how external institutional conditions affect stakeholders’ intention and readiness to use 3DCP technology. The conceptual framework posits that technology acceptance is shaped by both the individual and systemic factors. Professional users’ decision to embrace 3DCP is mediated not just by the perceived usefulness or ease of use, but also by the regulatory environment in which they operate and the infrastructural capacity available for implementation. This integrative approach ensures a more robust and realistic assessment of acceptance in the construction sector.

2. Literature

3D Concrete Printing has emerged as a transformative and innovative construction method that enables the automated layer-by-layer fabrication of concrete structures based on digital models [

19]. According to [

20] the technology has potential to reduce material waste, accelerate construction speed [

21], and enable complex geometries [

6]. These qualities of 3DCP make the technology particularly appealing in a global context of rising urban demand and sustainability concerns [

6]. In developed countries, 3DCP technology has been used to construct bridges [

22,

23], residential homes [

24], as well as commercial buildings [

25]. Other notable examples including the first 3D printed bridge in the Netherlands and ICON’s social housing projects in Mexico and the United States. The relevance of 3DCP to emerging economies like South Africa lies in the potential to address housing backlogs, infrastructure deficits, and construction inefficiencies [

5,

7]. However, the implementation of 3DCP is not merely a technical challenge [

26], it also requires institutional readiness, professional buy-in, and regulatory clarity. This is a major argument in this article. The argument underscores the need for country-specific studies that assess how key actors perceive and respond to this innovation.

2.1. Technology Adoption in Construction

The construction industry is characteristically conservative in its approach to innovation [

27], often constrained by fragmented supply chain, risk-averse cultures, and complex regulatory landscapes [

28]. According to [

29], digital innovations like Building Information Modeling, and 3DCP introduce disruption that challenges traditional roles, processes, and performance expectations. Previous studies have used models such as the Technology Acceptance Model and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology to assess technology uptake, mostly among professionals [

15,

17,

30]. While these models provide useful starting points, the application in construction often lacks sensitivity to contextual variables such as infrastructure availability, regulatory frameworks, and policy stability. In response, recent studies have begun to modify these models to include sector-specific enablers and barriers [

31,

32,

33,

34]. For example, [

35], reported that in developing countries, institutional support and perceived public sector legitimacy are often stronger predictors of technology uptake than individual behavioral intention alone.

2.2. DCP Acceptance: Global and South African Perspectives

Globally, research on 3DCP acceptance has focused on technical feasibility, economic analysis, and environmental benefits. [

36] assessed the printability and mix design challenges; [

37] analyzed the cost-benefit scenarios, while [

38] studied the rheological requirements. However, fewer studies have explored professional and regulatory perceptions of 3DCP as an innovation, especially in the Global South. In South Africa, emerging studies have examined the feasibility of 3DCP for social housing, notably by the University of Johannesburg and partners [

5,

7]. Yet these efforts remain localized, with limited integration into mainstream construction education, professional practice, or national housing policy. Regulatory bodies such as the South African Bureau of Standards, National Home Builders Registration Council, and local municipalities have yet to develop guidelines or certification protocols for 3D printed structures. A review by [

39] identified that one of the main inhibitors of additive manufacturing in Africa is regulatory uncertainty. Professionals often cite concerns for 3DCP over structural safety, code compliance, and lack of accredited training. Moreover, regional disparity in infrastructure capacity and internet connectivity affects readiness for digital construction technologies.

2.3. Institutional and Professional Factors Influencing Acceptance

Professional acceptance of 3DCP hinges on awareness, exposure, training, and perceived professional relevance [

3]. Architects may be excited about design freedom, while engineers might worry about structural integrity. Contractors often highlight the uncertainty of transitioning to machine-based operations and workforce implications. Regulators, on the other hand, function under the mandate of risk mitigation and public safety. The absence of standards on 3DCP in national building codes often leads to a cautious approach. According to [

40] when regulatory frameworks lag innovation, acceptance is stifled due to fears of legal liability and insurance complications.

2.4. Gaps and Conceptual Direction

There remains a significant gap in literature regarding multi-actor perspectives on 3DCP in South Africa. Most studies overlook the voices of regulators or treat the regulators as monolithic, despite the diversity of the different institutions involved. Similarly, little research has connected institutional factors with established technology acceptance frameworks. This study bridges these gaps by using a modified UTAUT model to assess both professional and regulatory readiness for 3DCP. The study proposes new constructs, regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness, which are absent in traditional models. This will enable a richer, context-specific understanding of 3DCP acceptance in South Africa’s construction ecosystem.

2.5. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical foundation of this study is anchored on the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model developed by [

18]. The UTAUT model is particularly suitable for understanding the behavioral intentions and actual use of technology among individuals within organizational settings. The UTAUT model posits that four core constructs of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions, determine technology acceptance. However, the UTAUT model has been widely criticized for its limited sensitivity to contextual variables [

34], especially in highly regulated sectors like the construction sector, and in the South African settings.

To address these limitations, this study employs a modified UTAUT model tailored to the South African construction context. Three additional constructs are introduced to the UTAUT framework in this study:

1. Regulatory clarity: This refers to the degree to which construction professionals and regulators perceive 3DCP policies and codes to be clear and actionable.

2. Policy maturity: The extent to which national policies have evolved to accommodate innovative construction technologies.

3. Infrastructure readiness: This is the availability of technological, material, and digital infrastructure to support 3DCP operations.

The extended framework allows the study to holistically analyze not only professional attitudes towards 3DCP but also how institutional and regulatory environments affect the acceptance. The extended model acknowledges that acceptance is not only a matter of personal intention but also an outcome shaped by systemic factors [

41]. The use of the adapted model ensures that the findings in the data are both theoretically grounded and context-specific, providing a robust framework for interpreting variables in acceptance across diverse professional groups and regulatory institutions in South Africa.

3. Materials and Methods

To investigate the acceptance of 3D concrete printing technology among construction professionals and regulatory bodies in South Africa, the study adopts a mixed method sequential explanatory design [

16]. The rationale for selecting this design lies in the complex, multifaceted nature of technology acceptance, which is influenced by a combination of individual beliefs, professional dynamics, and institutional or policy frameworks [

42]. The sequential explanatory model allows the researcher to firstly generate broad patterns through quantitative surveys and then explore the underlying causes and meanings of the patterns in qualitative interviews and focus group discussions. Quantitative methods offer generalizability and allow for the testing of theoretical constructs using statistical tools [

43], while qualitative methods provide deeper insights into actors’ experience, institutional practices, and the sociocultural environment that shapes attitudes towards innovation [

44]. In the context of emerging technologies like the 3DCP, a mixed method approach helps bridge the gap between numerical trends and the rich context-specific insights needed to inform policy and practice.

This methodology is particularly relevant given the dual focus of the study, understanding both professional attitudes and regulatory as well as institutional responses to 3DCP acceptance in South Africa. A purely quantitative approach may not sufficiently capture the institutional complexity and stakeholder interplay in the adoption process, while a purely qualitative design may not offer the representativeness required to inform broad policy. Thus, according to [

45], a mixed method approach allows for triangulation and enhance the validity and richness of findings. This study is situated within the broader South African construction industry, a sector that remains both economically significant and environmentally impacted. The construction sector in South Africa is characterized by a mix of formal and informal practices, varying levels of technological adoption, and significant regulatory oversight [

46]. The focus of the study is on two broad stakeholder categories:

1. Construction professionals, including architects, civil engineers, construction managers, project managers, contractors, and quantity surveyors.

2. Regulatory bodies such as the South African Bureau of Standards, the National Home Builders Registration Council, the Construction Industry Development Board, and local municipal planning departments.

These two groups are chosen because they represent the key drivers and gatekeepers of innovation adoption in the built environment. Professionals implement technologies on the ground while regulators shape the institutional environment through policy, standards, and certification. The study employed a multi-stage sampling technique [

16], comprising both stratified random sampling for the quantitative phase and the purposive sampling for the qualitative phase.

A stratified random sampling method was used to ensure that all key professional groups were represented in the sample. Strata are defined by professional affiliation, including evidence of registration with statutory councils such as Engineering Council of South Africa, the South African Council for the Architectural Profession, the South African Council for the Project and Construction Management Professions, and the South African Council for the Quantity Surveying Profession. From each stratum, respondents are selected randomly using LinkedIn networks and conference databases. The survey returned completed responses from 153 respondents which allowed for a meaningful statistical analysis. Exploratory Factor Analysis was used to test the validity of the different constructs in the UTAUT model. Structural Equation Modelling was used to explore the relationship between the different UTAUT variables and technology acceptance. To obtain the qualitative data, a purposive sampling strategy [

47] guided the selection of key participants for the interviews and focus groups. Key participants included decision makers within the regulatory bodies as well as experienced professionals who are familiar with 3DCP technology. Snowballing sampling technique [

48] was used to identify experts through referrals. The qualitative data was obtained from nine semi structured interviews with the regulators and policy makers, as well as two focus group discussions comprising six professionals across the different disciplines within the built environment.

3.1. Data Collection Methods

The quantitative data collection employed a structured questionnaire developed based on the modified UTAUT model. The modified model includes performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness. Each construct is operationalized through multiple items using a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). The questionnaire was pilot tested with ten respondents to ensure validity and reliability before the full deployment. Google form was used for the survey. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, demographic questions only captured respondents’ age, profession, years of experience, region of practice, and level of familiarity with 3DCP technology.

For the qualitative data, semi structured interviews targeting regulators and senior professionals with decision-making roles were employed. According to [

49] the semi structured interviews format allows for flexibility. The flexibility enabled the exploration of themes such as the extent to which current building codes in South Africa accommodate 3DCP, institutional challenges in regulating new technologies, and the views on the readiness of the construction sector in South Africa, for automation and innovation. The focus group discussions explored collective perceptions, shared barriers and differences across professions. The discussion guide included open-ended questions such as what opportunities and risks do you associate with 3DCP technology? How would you describe your institution’s openness to construction innovation? What enablers would increase your willingness to accept 3DCP in practice? The focus group discussion was conducted online via zoom and depending on the availability of the different participants.

While the study aims for representativeness, access to certain regulators was not possible due to institutional bureaucracy. It is equally possible that social desirability bias [

50] was muted in the responses from professionals who wished to appear more innovative than they have been in practice. These limitations were mitigated using multiple data sources and triangulation. The study obtained ethical clearance under the code: UJ_FEBE_FEPC_01726.

3.2. Data Analysis

Data from the survey was analyzed using R. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the responses. Exploratory Factor Analysis was used to confirm construct validity, assessing convergence and discriminant validity, in line with [

51]. Then Structural Equation Modeling was used to test the predictive power of the independent variables as well as the added contextual factors of regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness on 3DCP technology acceptance. The study employed SEM using SmartPLS based on the Partial Least Square due to the exploratory nature of the study and the sample size of 153. The choice of using SEM is also predicated on the ability to measure complex and multifaceted constructs [

52] as is the case in the current study. SEM is a robust multivariate technique used to analyze structural relationships between latent variables. SEM is ideal for modeling a causal system. The significance level adopted is p < 0.05. In line with [

52], a scale is used for the measurement because the constructs cannot be measured directly due to the latent nature. Cronbach’s alpha is used to measure the internal consistency of the scale [

53]. According to [

53], a high value of Cronbach’s alpha is not evidence that the items are influenced by only one latent variable. In order that the reliability of the scale can be estimated using the Cronbach’s alpha, it was important in line with [

54] to ensure that all the questions in a scale measure the same latent variable. A score above 0.7 was considered acceptable [

55] to measure how well the questions measure the latent variables. For the qualitative data, interview and focus group discussion transcripts were imported into Nvivo 15 for coding into themes. A thematic analysis approach [

16] was used to identify patterns across the responses. Both deductive codes, based on the UTAUT constructs, and inductive codes emerging from the data were applied. Identified themes were cross compared by stakeholder groups to understand divergences in perception between regulators and professionals. To ensure credibility [

56], transcripts were returned to the participants for checking. Transferability was enhanced through thick description of contexts [

57] while dependability and confirmability [

58] were addressed by maintaining an audit trail and using peer debriefing. The quantitative and qualitative data was integrated during the interpretation phase. Key survey findings were contextualized using qualitative narratives to offer a holistic view of 3DCP technology acceptance dynamics.

4. Results

The results are presented in two parts, in line with the mixed method approach. Firstly, the results from the quantitative data. The descriptive data indicate that most of the respondents were civil engineers, accounting for 20.9% of the study population. This is followed by construction managers, 20.3%, quantity surveyors, 17% and architects, 15%. Other professionals that responded were project managers, 13.7%, and contractors, forming 13.1%. Out of these respondents, 34% had experience spanning over 11 to 20 years, 32% had years of experience spanning 6 to 10 years. 18.3% of the respondents had about 5 years of experience while 15.7% had over 21 years of experience in the construction space. In terms of the respondents’ familiarity with 3DCP, only 12.4% were very familiar with 3DCP. 57.5% were somewhat familiar while 30.1% were not very familiar with 3DCP. The descriptive data implies that the target respondents for the study is adequate considering the emerging nature of 3DCP technology in South Africa. The respondents possessed a reasonable level of academic qualification to participate in the study and made meaningful contributions based on experiences accumulated over the years within the construction sector as well as a personal interest in 3DCP.

At the construct level, the different constructs of the UTAUT model including the contextual constructs of regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness were assessed based on the respondents’ perception of the constructs to influence the acceptance of 3DCP technology.

Table 1 presents the results of the descriptive statistics for the different constructs measured.

All the constructs measured demonstrated acceptable internal consistency with α ≥ 0.70. The contextual factors: Regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness exceed 0.85, which shows particularly strong reliability.

To examine the construct validity of the survey instrument, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on responses from the 153 construction professionals. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.841, indicating excellent suitability for factor analysis [

59]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity [

60] was significant at p < 0.001, confirming the presence of sufficient correlations among the variables for factor extraction. Nine factors were extracted using the Principal Axis Factoring [

61] with Varimax rotation, aligning with the predefined theoretical constructs. The result of the exploratory factor analysis is presented in

Table 2.

The entire factor loadings exceeded the threshold of 0.60, confirming a very good convergent validity [

62]. No substantial cross-loading was detected. This supports discriminant validity.

4.1. Hypothesis Testing using Structural Equation Modeling

Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypothesis which states that the independent variables do not significantly influence the behavioral intention and actual use of 3DCP technology.

4.1.1. Model Structure

The seven independent variables also known as latent constructs are: 1. Performance Expectancy (PE), 2. Effort Expectancy (EE), 3. Social Influence (SI), 4. Facilitating Conditions (FC), 5. Regulatory Clarity (RC), 6. Policy Maturity (PM), and 7. Infrastructure Readiness (IR) while the two dependent variables are: 8. Behavioral Intention (BI) and Actual Use (AU).

4.1.2. Hypotheses

H1 to H7: PE, EE, SI, FC, RC, PM, and IR do not influence BI.

H8: BI does not influence AU of 3DCP technology.

4.1.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

A confirmatory factor analysis was used to evaluate the model and presented in

Table 3.

All the constructs measured met the reliability threshold. CR > 0.7, AVE > 0.5, and α > 0.7. Hence discriminant validity is confirmed using Fornell-Lacker criterion [

63].

4.1.4. Structural Model

Table 4 presents the results from the path coefficient analysis for the different constructs.

The final SEM model fit summary is presented in

Table 5.

Based on the results presented, the null hypotheses were rejected because each of the seven latent variables had a significant effect on the behavioral intention to accept 3DCP technology. However, policy maturity was the strongest predictor, followed by regulatory clarity. These reveal the centrality of institutional factors impacting 3DCP technology acceptance. Behavioral intention was a strong predictor of actual use of the technology, thereby validating the logic of the UTAUT framework. The model achieved high explanatory power (R2 for BI = 0.69; R2 for AU = 0.53).

Given the significant path coefficients and p-values, the null hypothesis being that the independent variables do not affect the behavioral intention and actual use of 3DCP technology is rejected for all the constructs. The model demonstrates strong global fit, thereby validating both the measurement and the structural paths in the SEM analysis.

Table 6 presents the factor correlation matrix with square root of average variance extracted and bolded along the diagonal for all the measured constructs.

According to the data, all the diagonal values for square root of average variance extracted are greater than the off-diagonal inter-construct correlations. These are indications of strong internal consistency across all the constructs. The convergence is validated since the average variance extracted exceeds 0.50. The model satisfied discriminant validity using the Fornell-Larcker test. All the indices reflect excellent model-data alignment. The result from the qualitative data is presented in the next section.

4.2. Qualitative Data Results

Thematic analysis was employed to analyze the interviews and focus group discussions. This followed the [

64] six-steps framework: 1. familiarization with the data, 2. generating initial codes, 3. searching for themes, 4. reviewing themes, 5. defining and naming themes, and 6. producing the report.

Nvivo 14 was used for organizing the codes and identifying recurrent patterns within the data. The emergent themes and associated illustrative quotes from the participants are presented in

Table 7.

4.3. Triangulation and Interpretation of Findings

Triangulation was used to compare and integrate insights from the quantitative and qualitative datasets. Findings from the mixed-method research design reveal strong convergence across the different strata of data. The quantitative data confirmed the statistical significance of 3DCP technology acceptance determinants, while the qualitative data enriched the understanding by revealing practical, cultural, and institutional barriers and enablers. Notably, the contextual variables of regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness emerged as critical predictors in both data sets, thereby emphasizing the need for systematic changes in policy and planning towards the scaling of 3DCP technology.

Table 8 presents the findings from triangulation of the different data strands.

Based on the results from the study, the final path model is presented in

Figure 1.

5. Discussion

Technology acceptance in a developing country like South Africa is usually marred by a combination of factors [

39,

42,

65]. A rich insight into the interplay of individual, technological, and contextual factors influencing the behavioral intention and actual use of 3D concrete printing among construction professionals and regulators in South Africa is presented in this study. The results from the analyses confirm the robustness of the proposed modified Universal Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology framework, with all the path coefficients demonstrating statistically significant relationships and the structural model exhibiting excellent fit. The acceptance of 3DCP technology has not been wholistically investigated through the prism of the UTAUT in any previous study.

Performance expectancy on behavioral intention with a beta value of 0.28 emerged as a strong predictor of intention to use 3DCP. This is an indication that professionals who perceive the technology as capable of enhancing productivity, reducing construction time, and lowering waste are more inclined to accept the technology. This is consistent with [

18] who emphasized that performance expectancy is the most influential determinant of intention in technology acceptance models. In the South African context, where efficiency is critical in meeting low-income housing demands [

66], these perceived benefits directly influence the willingness to experiment with novel construction methods like 3DCP. Effort expectancy with a beta value of 0.22 also significantly influenced behavioral intention, underscoring the concerns about the ease of learning and operating the 3DCP systems as contemplated by [

5]. This finding reflects anxiety among stakeholders, particularly older or less tech-savvy professionals, regarding the complexity of integrating 3DCP into existing workflows in the construction sector. This finding resonates with the study by [

3]. The significance of this path suggests that successful adoption of 3DCP technology will require targeted capacity building programs and easy-to-use software, and hardware interfaces tailored to local contexts.

Although social influence has a smaller beta value of 0.17, the path from social influence on behavioral intention was significant and aligns with the research by [

39], which opined the growing impact of peer influence, academic research, and early adopters in shaping the perceptions about additive manufacturing. Younger professionals and innovation-oriented firms are gradually shifting the narrative from skepticism to curiosity. However, this modest coefficient indicates that a broader industry consensus is yet to be achieved [

3]. This could be according to [

5] likely due to the nascency of the technology in South Africa. The significance of facilitating conditions with a beta value of 0.19 affirms the need for technical support, training, and integration with existing construction infrastructure within the construction sector in South Africa [

7]. According to [

67], inadequate exposure, lack of demonstration projects, and the absence of 3DCP service providers constrain professionals’ confidence in using the technology. This finding signals the importance of ecosystem readiness, including logistics, software support, and material supply chains, to reduce the perceived implementation burdens.

Regulatory clarity had a beta value of 0.26. This makes it a strong driver of intention. The findings in the study which aligns with [

39] shows that professionals and regulators alike expressed hesitation in adopting a technology that is not yet formally acknowledged within the national building codes or certification schemes. This pathway illustrates the psychological and institutional weight of formal approval processes in technology diffusion. In agreement with [

68], this finding buttresses the fact that where guidelines and compliance mechanisms are ambiguous, risk aversion dominates, especially among large contractors and public sector entities. Policy maturity emerged as the strongest predictor of behavioral intention. This highlights the pivotal role of national and provincial policy frameworks in legitimizing and accelerating the integration of 3DCP technology into mainstream construction practices. This has not been reported in any previous study however [

69] opined that where innovation incentives, urban technology roadmaps, and public-private partnerships are absent or fragmented, acceptance is stifled. This finding suggests that comprehensive policies including subsidies, pilot projects, and strategic research and development funding are essential to create an enabling environment for experimentation and uptake.

The importance of infrastructure readiness which has a beta value of 0.25 points to the physical and digital preconditions for technology deployment. Many respondents indicated that regional disparities in infrastructure including stable electricity, access roads, and ICT infrastructure limit the feasibility of 3DCP technology uptake in rural or underdeveloped areas. While this variable often receives less attention in technology acceptance models, the significance in this study underscores the structural inequalities affecting innovation in South Africa.

As expected, behavioral intention was the most direct and significant predictor of actual use. This aligns with the foundational premise of Technology Acceptance Model and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [

18]. Intention is the proximal antecedent to behavior. However, the gap between a high intention and a relatively low actual usage reported in the qualitative interviews agrees with the findings of [

70] that systematic constraints including regulatory, infrastructure, and financial may inhibit the conversion from intention to action. Bridging this gap will be essential for a meaningful technological transition in the construction sector.

Collectively, the results indicate that whereas individual perception and social cues matter, it is the contextual enablers such as regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness that ultimately determine whether 3DCP technology will transition from experimental novelty to mainstream practice in South Africa. This deviates from the classical UTAUT assumptions in more digitally mature environments, underscoring the need to localize technology acceptance models in emerging economies. The results support a policy anchored adoption model; wherein behavioral intention is not only a function of technological perception but also institutional scaffolding and systematic readiness. This finding contributes to the literature by validating the extension of the UTAUT model with context specific variables relevant to construction innovation in the Global South.

To build on the foundation laid by this study, it is recommended that future research efforts are in the direction of examining how behavioral intention and actual use of 3DCP technology evolve over time as regulatory and policy landscapes shift. Cost-benefit and lifecycle assessments of printed structures, relative to conventional construction methods in various South African provinces is recommended. It is also important to explore how 3DCP adoption may affect local job markets, gender representation, and community participation in construction, particularly in townships. Another important aspect may be to design, implement, and evaluate live 3DCP housing or infrastructure pilots to generate experimental evidence and assess the social acceptability, resilience, and compliance in real world conditions.

6. Conclusions

The study sets out to examine the factors influencing the acceptance and use of 3D Concrete Printing technology in South Africa through the lens of both the construction professionals and regulatory authorities within the built environment. Using a modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model, enriched with three critical contextual constructs of regulatory clarity, policy maturity, and infrastructure readiness, the study generated a robust body of evidence through a mixed method research design comprising 153 complete survey, nine in-depth interviews, and two focus group discussions. The findings confirm that technology acceptance in the construction sector is not driven solely by individual beliefs about performance and effort. While constructs such as performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence were statistically significant, it was the institutional and structural enablers, particularly policy maturity (β = 0.31), regulatory clarity (β = 0.26), and infrastructural readiness (β = 0.25) that carried the most weight in predicting behavioral intention to use 3DCP technology. Behavioral intention in turn was a strong predictor of actual use (β = 0.47). This is an indication that there is a direct relationship between attitudinal readiness and technology adoption outcomes. The triangulated qualitative findings enriched this deduction by revealing a widespread enthusiasm tempered by uncertainty, institutional inertia, and uneven infrastructure across different regions of South Africa. Professionals cited the lack of standards, fragmented government direction, and absence of demonstrable success stories as major roadblocks. Regulators expressed caution about certifying structures produced with novel methods like 3DCP technology in the absence of a long-term performance data. The study’s contribution lies in the context-sensitive expansion of the UTAUT model, providing empirical support for the argument that technological innovation in the global south must be evaluated through a socio-technical lens. The study affirms the necessity of aligning policy instruments, legal frameworks, and infrastructural investments with grassroot innovation efforts, if transition to 3DCP technology is to be deployed at scale.

The findings from the study offer critical and timely implications for professionals, construction firms, regulators, and policymakers seeking to leverage 3DCP technology as a pathway towards a more sustainable, efficient, and innovative building solution in South Africa. The significance of effort expectancy and facilitating conditions implies that many practitioners are not yet comfortable with 3DCP processes. Professional bodies like the South African Institution of Civil Engineering, South African Council for the Architectural Profession, the Association of South African Quantity Surveyors, and construction firms should prioritize capacity building through targeted training programs and CPD workshops, simulated 3DCP design environments, and partnerships with academic institutions to develop tailored curricula for skills development and technological literacy. Professionals and contractors can enhance familiarity and reduce risk perception by participating in pilot projects. Pilot projects are veritable testbeds that can allow firms to explore printing logistics, material behaviors, and supply chain issues in a controlled environment, thereby converting behavioral intention into practical competency. With infrastructure readiness highlighted as a key determinant, firms should assess and upgrade their digital infrastructure, including CAD-BIM-3DCPrinter integration, material testing facilities, and connectivity tools. It is equally important to pay attention to logistical readiness in transporting and operating 3DC printers, especially in rural and semi-urban settings.

The strong determiner of regulatory clarity on the behavioral intention to accept 3DCP technology signals an urgent need for codified building regulations that reference 3DCP. The South African Bureau of Standards and the National Home Builders Registration Council in collaboration with academic and industry stakeholders should urgently draft minimum compliance benchmark for 3D printed structures. The regulators should issue an interim guideline for safety, material testing, and certification by referencing international best practices while localizing to the South African context. Given that the policy maturity was the strongest predictor of behavioral intention, the Department of Human Settlements, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and provincial authorities should embed 3DCP in smart cities strategies, green building incentives, and affordable housing innovation programs. This may include highlighting 3DCP’s role in reducing carbon footprint, cost of housing, and project timelines.

Because infrastructure readiness significantly impacts 3DCP acceptance, targeted investment to support regional equity through infrastructure investment is required to upgrade ICT, power supply, road infrastructure in townships and rural areas. Investment is also required to facilitate mobile or modular 3DCP units that can operate in low resource settings. The study recommends the provision of subsidies or incentives for early adopters within and outside the urban metros. The convergence between professionals’ perceptions and regulatory hesitancy highlights the need for an inclusive governance framework. Policy formulation should involve construction professionals, government departments, industry associations, as well as technical universities and research councils.

The study suggests that technology acceptance in construction cannot be reduced to end-user readiness alone. In the case of 3DCP, policy alignment, regulatory credibility, and infrastructure scaffolding are central. In addition to providing a technological answer, South Africa can foster the growth of 3DCP technology as a tool for housing justice, environmental sustainability, and economic transformation by implementing the recommendation presented in this study. 3DCP symbolizes a new age in construction, it is more than just a technological advancement. Given the growing challenges of housing backlog and climate change, a well thought out, inclusive, and proactive national strategy could establish South Africa as a leader in sustainable building technology in Africa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Stanley Okangba; methodology, Stanley Okangba; software, Stanley Okangba; validation, Stanley Okangba, Ntebo Ngcobo, and Jeffrey Mahachi; formal analysis, Stanley Okangba; investigation, Stanley Okangba; resources, Ntebo Ngcobo, and Jeffrey Mahachi; data curation, Stanley Okangba; writing—original draft preparation, Stanley Okangba; writing—review and editing, Stanley Okangba, Ntebo Ngcobo, and Jeffrey Mahachi; visualization, Stanley Okangba; supervision, Ntebo Ngcobo and Jeffrey Mahachi; project administration, Stanley Okangba. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding however, the APC was funded by the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Johannesburg, protocol code UJ_FEBE_FEPC_01726 on October 1, 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used QuillBot and Grammarly for the purpose of editing and grammar checking. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| CAD |

Computer-Aided Design |

| 3DCP |

3-Dimensional Concrete Printing |

| SMaCT |

Sustainable Materials and Construction Technologies |

| TAM |

Technology Acceptance Model |

| UTAUT |

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| PE |

Performance Expectancy |

| EE |

Effort Expectancy |

| SI |

Social Influence |

| FC |

Facilitating Conditions |

| RC |

Regulatory Clarity |

| PM |

Policy Maturity |

| IR |

Infrastructure Readiness |

| BI |

Behavioral Intention |

| AU |

Actual Use |

| SABS |

South Africa Bureau of Standards |

| NHBRC |

National Home Builders Registration Council |

| DHS |

Department of Human Settlement |

| CIDB |

Construction Industry Development Board |

| CSIR |

Council for Scientific and Industry Research |

| ECSA |

Engineering Council of South Africa |

| SACAP |

South African Council for the Architectural Profession |

| SACPCMP |

South African Council for the Project and Construction Management Professions |

| SACQSP |

South African Council for the Quantity Surveying Profession |

| EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modelling |

| ICT |

Information and Communications Technology |

References

- Ullah K, Lill I, Witt E. An Overview of BIM Adoption in the Construction Industry: Benefits and Barriers. 2019. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/books/oa-edited-volume/15708/chapter/87072629/An-Overview-of-BIM-Adoption-in-the-Construction (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Llale J, Setati M, Mavunda S, Ndlovu T, Root D, Wembe P. A Review of the Advantages and Disadvantages of the Use of Automation and Robotics in the Construction Industry. In 2019. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-26528-1_20 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Ambily P, Kaliyavaradhan S, Rajendran N. Top challenges to widespread 3D concrete printing (3DCP) adoption - A review. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering 2024, 28, 300–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi SH, Tetik M, Mohite A, Peltokorpi A, Li M, Weng Y, et al. Additive Manufacturing in the Construction Industry: The Comparative Competitiveness of 3D Concrete Printing [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/9/3865 (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Aghimien D, Aigbavboa C, Aghimien L, Thwala WD, Ndlovu L. Making a case for 3D printing for housing delivery in South Africa. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 2020, 13, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebel S, Top SM, Takva C, Gokgoz BI, Llerisoy ZY, Sahmaran M. Investigation of three-dimensional concrete printing (3DCP) technology in AEC industry in the context of construction, performance and design | AVESİS [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://avesis.gazi.edu.tr/yayin/307fb186-4992-4c45-99b5-c2aacfb23f6e/investigation-of-three-dimensional-concrete-printing-3dcp-technology-in-aec-industry-in-the-context-of-construction-performance-and-design (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Moghayedi A, Mahachi J, Lediga R. Revolutionizing affordable housing in Africa: A comprehensive technical and sustainability study of 3D-printing technology. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaloudis M, Roca J. Sustainability tradeoffs in the adoption of 3D Concrete Printing in the construction industry. Sustainability tradeoffs in the adoption of 3D Concrete Printing in the construction industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 307. [Google Scholar]

- Gebel S, Top SM, Takva C, Gokgoz BI, Ilerisoy ZY, Sahmaran M. Exploring the role of 3D concrete printing in AEC: Construction, design, and performance. Journal of Construction Engineering Management & Innovation 2024, 7, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca M, Matos AM. 3D Construction Printing Standing for Sustainability and Circularity: Material-Level Opportunities. Materials 2023, 16, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia M, Nematollahi B, Sanjayan J. Printability, accuracy and strength of geopolymer made using powder-based 3D printing for construction applications. Automation in Construction 2019, 101, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan SA, İlcan H, Aminipour E, Şahin O, Al Rashid A, Şahmaran M, et al. Buildability analysis on effect of structural design in 3D concrete printing (3DCP): An experimental and numerical study. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2023, 19, e02295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza MH, Besklubova S, Zhong RY. Economic analysis of offsite and onsite 3D construction printing techniques for low-rise buildings: A comparative value stream assessment. Additive Manufacturing 2024, 89, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarseh S, Kamardeen I. The Impact of Individual Beliefs and Expectations on BIM Adoption in the AEC Industry. In 2017. p. 466–455. Available online: https://easychair.org/publications/paper/MhkG (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Jayaseelan R, Brindha, D. A Qualitative Approach Towards Adoption of Information and Communication Technology by Medical Doctors Applying UTAUT Model. 2020, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders MNK, Lewis P, Thornhill A. Research methods for business students. Eighth Edition. New York: Pearson; 2019.

- Lee DC, Lin SH, Ma HL, Wu DB. Use of a Modified UTAUT Model to Investigate the Perspectives of Internet Access Device Users. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2017, 33, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi B, Xia M, Sanjayan J. Current Progress of 3D Concrete Printing Technologies. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (IAARC) [Internet]. Taipei, Taiwan: Tribun EU, s.r.o., Brno; 2017. Available online: http://www.iaarc.org/publications/2017_proceedings_of_the_34rd_isarc/current_progress_of_3d_concrete_printing_technologies.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Al-Raqeb H, Ghaffar SH. 3D Concrete Printing in Kuwait: Stakeholder Insights for Sustainable Waste Management Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman AU, Perrot A, Birru BM. Recommendations for quality control in industrial 3D concrete printing construction with mono-component concrete: A critical evaluation of ten test methods and the introduction of the performance index. Dev Built Environ [Internet]. 2023, 16. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85172027911&doi=10.1016%2fj.dibe.2023.

- Bhooshan S, Bhooshan V, Dell’Endice A, Chu J, Singer P, Megens J, et al. The Striatus bridge. Architecture, Structures and Construction 2022, 2, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari A, Kazemian A, Ataei S. Comparative Analysis of 3D Printed Bridge Construction in Louisiana. Publications [Internet]. Available online: https://repository.lsu.edu/transet_pubs/152 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Fernandez LIC, Caldas LR, Mendoza Reales OA. Environmental evaluation of 3D printed concrete walls considering the life cycle perspective in the context of social housing. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 74, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaryouti Y, Suwaidi MA, AlKhuwaildi RM, Kolthoum H, Youssef I, Imam MA. A Case Study of the Largest 3D Printed Villa: Breaking Boundaries in Sustainable Construction. E3S Web of Conferences 2024, 586, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollakanti CR, Prasad CVSR. Applications, performance, challenges and current progress of 3D concrete printing technologies as the future of sustainable construction – A state of the art review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 65, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue X, Zhang R, Yang R, Dai J. Innovation in Construction: A Critical Review and Future Research. International Journal of Innovation Science 2014, 6, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okangba S, Khatleli N, Root D. Indicators for Construction Projects Supply Chain Adaptability using Blockchain Technology: A Review. Proceedings of International Structural Engineering and Construction [Internet]. 2021, 8(1). Available online: https://www.isec-society.org/ISEC_PRESS/ISEC_11/xml/CON-23.xml (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Rane N, Choudhary S, Rane J. Leading-edge Technologies for Architectural Design: A Comprehensive Review [Internet]. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4637891 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Ifinedo, P. Technology Acceptance by Health Professionals in Canada: An Analysis with a Modified UTAUT Model. In: 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 2012. p. 2937–46.

- Venkatesh V, Thong JYL, Xu X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal M, Maqsood T. Toward improving BIM acceptance in facilities management: A hybrid conceptual model integrating TTF and UTAUT - RMIT University [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/esploro/outputs/9921886344901341?institution=61RMIT_INST&skipUsageReporting=true&recordUsage=false (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Hewavitharana T, Nanayakkara S, Perera A, Perera P. Modifying the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) Model for the Digital Transformation of the Construction Industry from the User Perspective. Informatics 2021, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okangba S, Khatleli N, Root D. On the Journey to Blockchain Technology, BIM and the BEE in the Construction Sector 2022.

- Azamela JC, Tang Z, Ackah O, Awozum S. Assessing the Antecedents of E-Government Adoption: A Case of the Ghanaian Public Sector. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul AV, Santhanam M, Meena H, Ghani Z. 3D printable concrete: Mixture design and test methods. Cement and Concrete Composites 2019, 97, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer AN, Kozlova M, Mohite A, Yeomans JS, Hall D. A Stochastic Decision-Support Framework for Exploring Strategic Pathways in 3D Concrete Printing. 2024 Sept 4. Available online: https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/692648 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Yang L, Gao Y, Chen H, Jiao H, Dong M, Bier T, et al. 3D printing concrete technology from a rheology perspective: a review. Advances in Cement Research 2024.

- Klenam D, Asumadu T, Bodunrin M, Obiko J, Genga R, Maape S, et al. Frontiers | Toward sustainable industrialization in Africa: the potential of additive manufacturing – an overview. 2025. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/manufacturing-technology/articles/10.3389/fmtec.2024.1410653/full (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Blind, K. 12: The overall impact of economic, social and institutional regulation on innovation: an update in: Handbook of Innovation and Regulation [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781800884472/b-9781800884472.00020.xml (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Taherdoost, H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manufacturing 2018, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay DJ, Doleck T, Bazelais P. Context and technology use: Opportunities and challenges of the situated perspective in technology acceptance research. British Journal of Educational Technology 2019, 50, 2450–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, PM.; Doing Survey Research | A Guide to Quantitative Methods | Peter M. Nar [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315172231/survey-research-peter-nardi (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Leung, L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research: Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care [Internet]. 2015. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jfmpc/_layouts/15/oaks.journals/downloadpdf.aspx?an=01697686-201504030-00008 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Moon, MD. Triangulation: A Method to Increase Validity, Reliability, and Legitimation in Clinical Research. 2019. Available online: https://www.jenonline.org/article/S0099-1767 (accessed on day month year).

- van Wyk L, Kajimo-Shakantu K, Opawole A. Adoption of innovative technologies in the South African construction industry. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation 2021, 42, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell S, Greenwood M, Prior S, Shearer T, Walkem K, Young S, et al. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples - Steve Campbell, Melanie Greenwood, Sarah Prior, Toniele Shearer, Kerrie Walkem, Sarah Young, Danielle Bywaters, Kim Walker, 2020 [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1744987120927206?casa_token=v3Y27fHtUMkAAAAA%3AOJ5NCv_hqLieuZHPCHlNzJAWEM5xR5-NxKDSinA9YtoVfC_pQUvLcyYL4BTP5IJTOh1cdGrQtHmQ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A. Snowball Sampling. SAGE Research Methods Foundations [Internet]. 2019 Sept 9. Available online: http://methods.sagepub.com/foundations/snowball-sampling (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Adams, WC.; Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In: Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015. p. 492–505. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119171386.ch19 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Larson, RB.; Controlling social desirability bias - Ronald B. Larson, 2019 [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1470785318805305?casa_token=BxbOtzP5SpAAAAAA%3AZQ59p4XhyLptMkYHPG0jE2mPFfZK6nZq1QubLiWJ3ExjQ_kzZFBzUjV3AHxQbpQT6JQPx5alZ3ml (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Cheung GW, Cooper-Thomas H, Lau RS, Wang LC. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations | Asia Pacific Journal of Management [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Wright R, Campbell D, Thatcher J, Roberts N. Operationalizing Multidimensional Constructs in Structural Equation Modeling: Recommendations for IS Research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems [Internet]. 2012, 30(1). Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.

- Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Den S, Schneider C, Mirzaei A, Carter S. How to measure a latent construct: Psychometric principles for the development and validation of measurement instruments. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2020, 28, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang MA, Omar ED, Baharum NA. A Review on Sample Size Determination for Cronbach’s Alpha Test: A Simple Guide for Researchers. Malays J Med Sci. 2018, 25, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, DG.; Methods and Meanings: Credibility and Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research. | EBSCOhost [Internet]. 2014. Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A16%3A7940976/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A93340461&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Slevin E, Sines D. Enhancing the truthfulness, consistency and transferability of a qualitative study: Utilising a manifold of approaches - ProQuest [Internet]. 2013. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/200819635?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Anney, VN. Ensuring the Quality of the Findings of Qualitative Research: Looking at Trustworthiness Criteria 2015.

- Nkansah, BK. On the Kaiser-Meier-Olkin’s Measure of Sampling Adequacy 2018.

- Williams B, Onsman A, Brown T. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Five-Step Guide for Novices - Brett Williams, Andrys Onsman, Ted Brown, 2010 [Internet]. 2010. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.33151/ajp.8.3.93 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- de Winter JCF, Dodou D. Full article: Factor recovery by principal axis factoring and maximum likelihood factor analysis as a function of factor pattern and sample size [Internet]. 2011. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02664763.2011.610445?casa_token=KwZM3g3KFykAAAAA%3ApRvkWqutSmsvGnSs-wT3_PM6o5c343VEov87k97dAJMQjFQZbBF5NfkvgiVK-uYARbFNftAYxlgb (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Carlson KD, Herdman AO. Understanding the Impact of Convergent Validity on Research Results - Kevin D. Carlson, Andrew O. Herdman, 2012 [Internet]. 2010. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1094428110392383?casa_token=INlGl9IVJjoAAAAA%3Ap1WgNgZybah5_BpNae6v8NTtYGWjkkNolRwkNGcNkIQDtKhzXcFW7CZktI2GBMqcEahDvZwqkGaY (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Ab Hamid MR, Sami W, Mohmad Sidek MH. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic Analysis | SpringerLink [Internet]. 2019. Available online: https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Adaloudis M, Bonnin Roca J. Sustainability tradeoffs in the adoption of 3D Concrete Printing in the construction industry. J Clean Prod [Internet] 2021, 307. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85105274147&doi=10.1016%2fj.jclepro.2021.127201&partnerID=40&md5=de9cb8fa72f34f108620eae0051e9a7d.

- Mhlongo ZD, Gumbo T, Musonda I, Moyo T. Sustainable low-income housing: Exploring housing and governance issues in the Gauteng City Region, South Africa. Urban Governance 2024, 4, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Natasha Abdul Jalil S, Rizal Alias A, Alias A. Challenges and strategies in implementing 3D concrete printing (3DCP) technology in Malaysia: Materials and Design Codes. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2025, 1509, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia S, Weng T, Jin R, Yang M, Yu M, Zhang W, et al. Curcumin-incorporated 3D bioprinting gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel reduces reactive oxygen species-induced adipose-derived stem cell apoptosis and improves implanting survival in diabetic wounds. Burns and Trauma [Internet] 2022, 10. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85127463327&doi=10.1093%2fburnst%2ftkac001&partnerID=40&md5=4de344994182c8af0269124912e3bbf5.

- Voorwinden, A. The privatised city: technology and public-private partnerships in the smart city. Law, Innovation and Technology 2021, 13, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello G, Fu X, Mohnen P, Ventresca M. The Creation and Diffusion of Innovation in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Economic Surveys 2016, 30, 884–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Further readings.

- Yossef, M. and Chen, A. (2015), “Applicability and limitations of 3D printing for civil structures”, Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Autonomous and Robotic Conference of Infrastructure, IA State University, Ames, pp. 237–246.

- Aghimien, D. Aigbavboa, C. Aghimien, L. Thwala, W.D. and Ndlovu, L. Making a case for 3D printing for housing delivery in South Africa. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 2019, 13, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).