Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

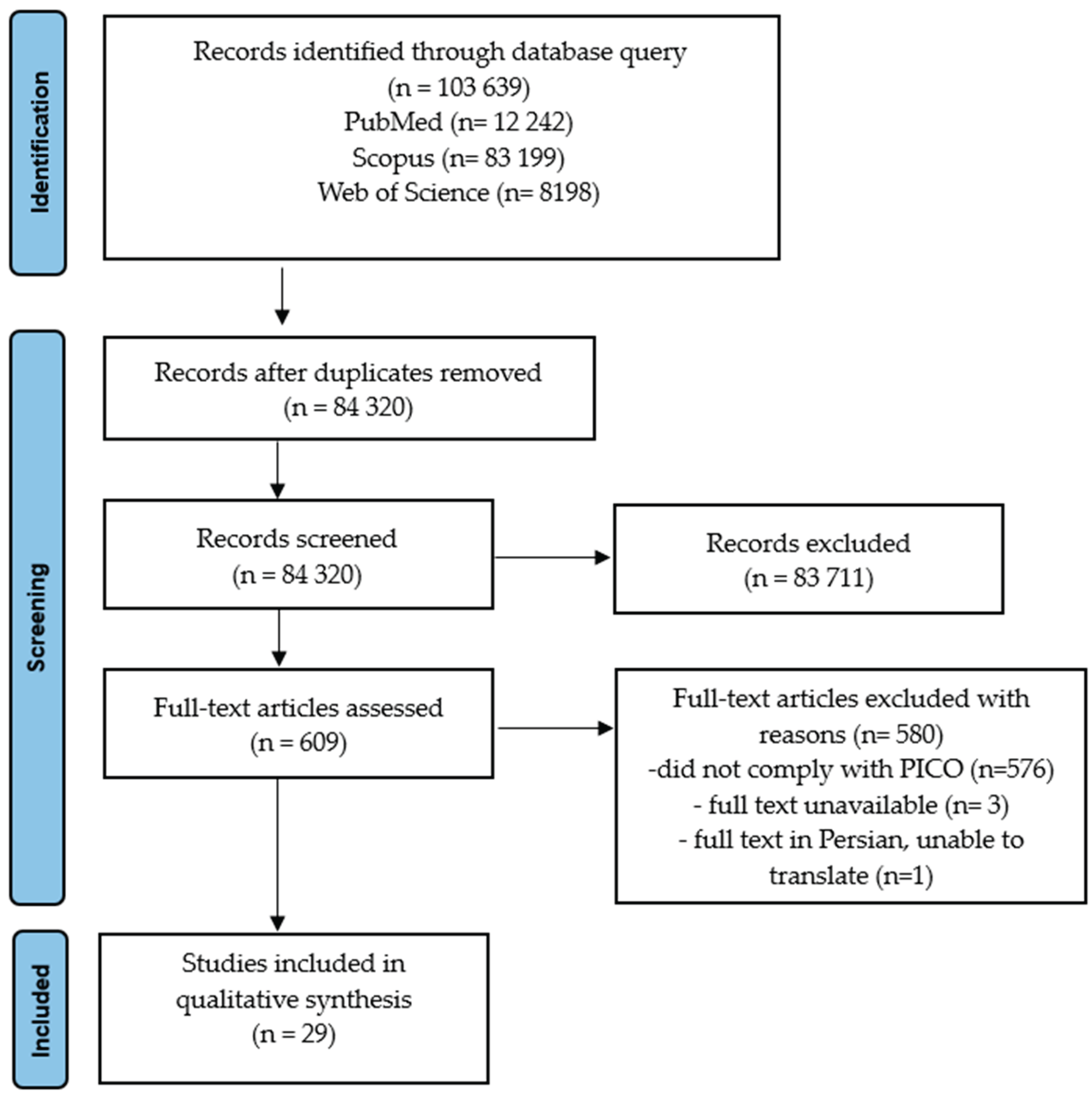

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compilation of an Inventory of Ingredients Declared as Active in Trichological Shampoos

2.2. Evidence Acquisition from Published Clinical Trials

3. Results

3.1. Ingredients Advertised as “Active” in Trichological Shampoos

3.2. Published Evidence Behind the “Active” Ingredients in Trichological Shampoos

4. Discussion

- Only in 2 studies, the authors explicitly declared the absence of conflict of interest (COI) both with regard to funding of the study and financial relations between authors with potentially commercial beneficiaries, of which a non-proprietary, in-house preparation was used in one study [73] and a commercial brand of product was named in the other [55].

- Six trials were disclosed (sometimes vaguely or indirectly) as industry-funded or -sponsored [45,56–58,62,63]. Except the above-mentioned two, in remaining 3 trials there was no statement with this regard.

- In 5 trials at least some co-authors were disclosed as employees of manufacturers of products tested, or received other financial gratifications from them for performing the study [45,56,62,63,69]. In 2 trials, the authors declared the absence of any link to manufacturers [55,73], while there was no statement with this regard in remaining four [57,58,61,67].

- Tested products were identified by brand or tradename in 5 trials [55–58,67], non-proprietary, in-house preparations were described in 3 trials [45,61,73] with no statement in the remaining three [63,69].

- Possible bias or study limitations were addressed in only 2 of the 11 trials [55,56].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Owecka, B.; Tomaszewska, A.; Dobrzeniecki, K.; Owecki, M. The Hormonal Background of Hair Loss in Non-Scarring. Alopecias Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 513. [CrossRef]

- Rallis, E.; Lotsaris, K.; Grech, V.S.; Tertipi, N.; Sfyri, E.; Kefala, V. The Nutrient-Skin Connection: Diagnosing Eating Disorders Through Dermatologic Signs. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4354. [CrossRef]

- Smolarczyk, K.; Meczekalski, B.; Rudnicka, E.; Suchta, K.; Szeliga, A. Association of Obesity and Bariatric Surgery on Hair Health. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60, 325. [CrossRef]

- Brnic, S.; Spiljak, B.; Zanze, L.; Barac, E.; Likic, R.; Lugovic-Mihic, L. Treatment Strategies for Cutaneous and Oral Mucosal Side Effects of Oncological Treatment in Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1901. [CrossRef]

- Haagsma, A.B.; Otto, F.G.; de Sa Vianna, M.L.G.; Maingue, P.M.; Muller, A.P.; de Oliveira, N.; Abbott, L.A.; da Silva, F.P.G.; Klein, C.K.; Herzog, D.M.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of COVID-19 Survivors at a Public Multidisciplinary Health Clinic. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1888. [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Moog, P.; Li, C.; Steinbacher, L.; Knoedler, S.; Kukrek, H.; Dornseifer, U.; Machens, H.G.; Jiang, J. Exploring the Association Between Multidimensional Dietary Patterns and Non-Scarring Hair Loss Using Mendelian Randomization. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2569. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, A.; Conde, G.; Greco, J.F.; Gharavi, N.M. Management of androgenic alopecia: a systematic review of the literature. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2024, 26, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Nobari, N.N.; Roohaninasab, M.; Sadeghzadeh-Bazargan, A.; Goodarzi, A.; Behrangi, E.; Nikkhah, F.; Ghassemi, M. A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials Using Single or Combination Therapy of Oral or Topical Finasteride for Women in Reproductive Age and Postmenopausal Women with Hormonal and Nonhormonal Androgenetic Alopecia. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 32, 813–823.

- Desai, D.D.; Nohria, A.; Sikora, M.; Anyanwu, N.; Shapiro, J.; Lo Sicco, K.I. Comparative analysis of low-dose oral minoxidil with spironolactone versus finasteride or dutasteride in female androgenetic alopecia management. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 622. [CrossRef]

- Keerti, A.; Madke, B.; Keerti, A.; Lopez, M.J.C.; Lirio, F.S. Topical Finasteride: A Comprehensive Review of Androgenetic Alopecia Management for Men and Women. Cureus 2023, 15, e44949. [CrossRef]

- Starace, M.V.R.; Gupta, A.K.; Bamimore, M.A.; Talukder, M.; Quadrelli, F.; Piraccini, B.M. The Comparative Effects of Monotherapy with Topical Minoxidil, Oral Finasteride, and Topical Finasteride in Postmenopausal Women with Pattern Hair Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2024, 10, 293-300. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Cauhe, J.; Lo Sicco, K.I.; Shapiro, J.; Hermosa-Gelbard, A.; Burgos-Blasco, P.; Melian-Olivera, A.; Ortega-Quijano, D.; Pindado-Ortega, C.; Buendia-Castano, D.; Asz-Sigall, D.; et al. Characterization and Management of Adverse Events of Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil Treatment for Alopecia: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1805. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Song, S.Y.; Sung, J.H. Recent Advances in Drug Development for Hair Loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3461. [CrossRef]

- Szendzielorz, E.; Spiewak, R. Caffeine as an Active Ingredient in Cosmetic Preparations Against Hair Loss: A Systematic Review of Available Clinical Evidence. Healthcare. 2025, 13, 395. [CrossRef]

- Krefft-Trzciniecka, K.; Pietowska, Z.; Pakiet, A.; Nowicka, D.; Szepietowski, J.C. Short-Term Clinical Assessment of Treating Female Androgenetic Alopecia with Autologous Stem Cells Derived from Human Hair Follicles. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 53. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Pascual, M.A.; Sacristan, S.; Toledano-Macias, E.; Naranjo, P.; Hernandez-Bule, M.L. Effects of RF Electric Currents on Hair Follicle Growth and Differentiation: A Possible Treatment for Alopecia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7865. [CrossRef]

- Lama, S.B.C.; Perez-Gonzalez, L.A.; Kosoglu, M.A.; Dennis, R.; Ortega-Quijano, D. Physical Treatments and Therapies for Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4534. [CrossRef]

- Szendzielorz, E.; Spiewak, R. Adenosine as an Active Ingredient in Topical Preparations Against Hair Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published Clinical Trials. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1093. [CrossRef]

- Perez, S.M.; AlSalman, S.A.; Nguyen, B.; Tosti, A. Botulinum Toxin in the Treatment of Hair and Scalp Disorders: Current Evidence and Clinical Applications. Toxins (Basel) 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Bento, E.B.; Matos, C.; Ribeiro Junior, H.L. Successful Treatment of Hair Loss and Restoration of Natural Hair Color in Patient with Alopecia Areata Due to Psychological Disorder Using Exosomes: Case Report with 6-Month Follow-Up. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 97. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, L.; Ding, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, N. Androgenetic Alopecia: An Update on Pathogenesis and Pharmacological Treatment. Drug. Des. Devel. Ther. 2025, 19, 7349-7363. [CrossRef]

- Vrapcea, A.; Pisoschi, C.G.; Ciupeanu-Calugaru, E.D.; Trasca, E.T.; Tutunaru, C.V.; Radulescu, P.M.; Radulescu, D. Inflammatory Signatures and Biological Markers in Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy for Hair Regrowth: A Comprehensive Narrative Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2025, 15, 1123. [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Jang, Y.; Sim, J.; Ryu, D.; Cho, E.; Park, D.; Jung, E. Anti-Hair Loss Effect of Veratric Acid on Dermal Papilla Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2240. [CrossRef]

- Irwig, M.S. Safety concerns regarding 5alpha reductase inhibitors for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2015, 22, 248-253. [CrossRef]

- Almohanna, H.M.; Perper, M.; Tosti, A. Safety concerns when using novel medications to treat alopecia. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2018, 17, 1115-1128. [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.S. Ongoing Concerns Regarding Finasteride for the Treatment of Male-Pattern Androgenetic Alopecia. JAMA Dermatol 2021, 157, 25-26. [CrossRef]

- Amberg, N.; Fogarassy, C. Green Consumer Behavior in the Cosmetics Market. Resources 2019, 8, 137. [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 184-207. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q.; Yang, S.; Wang, C. Advancing herbal medicine: enhancing product quality and safety through robust quality control practices. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1265178. [CrossRef]

- Trueb, R.M.; Rezende, H.D.; Dias, M.F.R.G.; Uribe, N.C. Trichology and Trichiatry; Etymological and Terminological Considerations. Int. J. Trichology 2022, 14, 117-119. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, F.; Armijo, M.; Naranjo, R.; Dulanto, F. Le syndrome tricho-rhino-phalangien (Giedion). Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 1978, 105, 17-21.

- Plewig, G.; Schill, W.B.; Hofmann, C. [Oral treatment with tretinoin: andrological, trichological, ophthalmological findings and effects on acne (author’s transl)]. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1979, 265, 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Bartosova, L.; Werkmannova, A.; Smolan, S.; Fingerova, H. Trichological alterations in women during pregnancy and after delivery. Acta Univ. Palacki Olomuc Fac. Med. 1987, 117, 225-246.

- Rushton, D.H.; Ramsay, I.D.; James, K.C.; Norris, M.J.; Gilkes, J.J. Biochemical and trichological characterization of diffuse alopecia in women. Br. J. Dermatol. 1990, 123, 187-197. [CrossRef]

- Brzezinska-Wcislo, L.; Bogdanowski, T.; Koslacz, E.; Hawrot, A. [Trichological examinations in women suffering from diabetes mellitus]. Wiad. Lek. 2000, 53, 30-34.

- Yesudian, P. Why Another journal? Int. J. Trichology 2009, 1, 1. [CrossRef]

- Trueb, R.M. A Comment on Mercantilism in the Trichological Sciences. Int. J. Trichology 2023, 15, 85-87. [CrossRef]

- Trueb, R.M.; Gadzhigoroeva, A.; Kopera, D.; Luu, N.C.; Dmitriev, A. The Problem with Capitalism in the Trichological Sciences. Int. J. Trichology 2023, 15, 79-84. [CrossRef]

- Pyzik, M.; Plichta, D.; Spiewak, R. Analiza występowania składników deklarowanych jako aktywne w preparatach przeciw wypadaniu włosów oraz przegląd systematyczny badań nad ich skutecznością. [An occurrence analysis of ingredients declared as active in anti-hair loss products and systematic review of studies on their effectiveness] (in Polish). Estetol. Med. Kosmetol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Szendzielorz, E.; Śpiewak, R. An analysis of the presence of ingredients that were declared by the producers as “active” in trichological shampoos for hair loss. Estetol. Med. Kosmetol. 2024, 14, 001.en. [CrossRef]

- Szendzielorz, E.; Spiewak, R. Placental Extracts, Proteins, and Hydrolyzed Proteins as Active Ingredients in Cosmetic Preparations for Hair Loss: A Systematic Review of Available Clinical Evidence. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10301. [CrossRef]

- Spiewak, R.; Szendzielorz, E. Topical ingredients considered as active against hair loss: a scoping review. Available online: https://osf.io/2kmhd (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, 452 S.; Guyatt, G.H. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401-406. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.W.; Trüeb, R.M.; Hänggi, G.; Innocenti, M.; Elsner, P. Topical melatonin for treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Trichology. 2012, 4, 236-245. http://doi:10.4103/0974-7753.111199.

- Fischer, T.W.; Burmeister, G.; Schmidt, H.W.; Elsner, P. Melatonin increases anagen hair rate in women with androgenetic alopecia or diffuse alopecia: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 150, 341–345. [CrossRef]

- Pekmezci, E.; Dündar, C.; Türkoğlu, M. A proprietary herbal extract against hair loss in androgenetic alopecia and telogen effluvium: a placebo-controlled, single-blind, clinical-instrumental study. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2018, 27, 51-57.

- Reygagne, P.; Mandel, V.D.; Delva, C.; et al. An anti-hair loss treatment in the management of mild androgenetic alopecia: Results from a large, international observational study. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, 15134. [CrossRef]

- Turlier, V.; Darde, M.S.; Loustau, J.; Mengeaud, V. Assessment of the effects of a hair lotion in women with acute telogen effluvium: a randomized controlled study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 12-20. [CrossRef]

- Pelfini, C.; Fideli, D.; Speziali, A.; Vignini, M. Effects of a topical preparation on some hair growth parameters, evaluated utilizing a morphometric computerized analysis. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1987, 9, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Marotta, J.C.; Patel, G.; Carvalho, M.; Blakeney, S. Clinical Efficacy of a Topical Compounded Formulation in Male Androgenetic Alopecia: Minoxidil 10%, Finasteride 0.1%, Biotin 0.2%, and Caffeine Citrate 0.05% Hydroalcoholic Solution. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2020, 24, 69-76.

- Lueangarun, S.; Panchaprateep, R. An Herbal Extract Combination (Biochanin A, Acetyl tetrapeptide-3, and Ginseng Extracts) versus 3% Minoxidil Solution for the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia: A 24-week, Prospective, Randomized, Triple-blind, Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2020,13, 32-37.

- Piérard, G.; Piérard-Franchimont, C.; Nikkels-Tassoudji, N.; Nikkels, A.; Léger, D. S. Improvement in the inflammatory aspect of androgenetic alopecia. A pilot study with an antimicrobial lotion. J. Dermatol. Treatment. 1996, 7 , 153–157. [CrossRef]

- Masoud, F.; Alamdari, H.A.; Asnaashari, S.; Shokri, J.; Javadzadeh, Y. Efficacy and safety of a novel herbal solution for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia and comparison with 5% minoxidil: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial study. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, 14467. [CrossRef]

- Wessagowit, V.; Tangjaturonrusamee, C.; Kootiratrakarn, T.; et al. Treatment of male androgenetic alopecia with topical products containing Serenoa repens extract. Australas J. Dermatol. 2016, 57, 76-82. [CrossRef]

- Barat, T.; Abdollahimajd, F.; Dadkhahfar, S.; Moravvej, H. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of cow placenta extract lotion versus minoxidil 2% in the treatment of female pattern androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2020, 6, 318–321. [CrossRef]

- Dhurat, R.; Chitallia, J.; May, T.W.;Ammani, M.; Madhukara, J.J.; Anandan, S.; Vaidya, P.; Klenk, A. An Open-Label Randomized Multicenter Study Assessing the Noninferiority of a Caffeine-Based Topical Liquid 0.2% versus Minoxidil 5% Solution in Male Androgenetic Alopecia. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2017, 30, 298-305. [CrossRef]

- Sisto, T.; Bussoletti, C.; Celleno, L. Efficacy of a Cosmetic Caffeine Shampoo in Androgenetic Alopecia management. II Note. J. Appl. Cosmetol. 2013, 31, 57-66.

- Bussoletti, C; Mastropietro, F.; Tolaini, M.V; Celleno, L. Use of a Caffeine Shampoo for the Treatment of Male Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Appl. Cosmetol. 2010, 28, 153-162.

- Rapaport, J.; Sadgrove, N.J.; Arruda, S.; Swearingen, A.; Abidi, Z.; Sadick, N. Real World, Open-Label Study of the Efficacy and Safety of a Nowel Serum in Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2023, 22, 559-564.

- Samadi, A.; Rokhsat, E.; Saffarian, Z.; Goudarzi, M.M.; Kardeh, S.; Nasrollahi, S.A.; Firooz, A. Assessment of the efficacy and tolerability of a topical formulation containing caffeine and Procapil 3% for improvement of male pattern hair loss. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 1492-1494. [CrossRef]

- Faghihi, G.; Iraji, F.; Harandi, M.; Nilforoushzadeh, M.A.; Askari, G. Comparison of the efficacy of topical minoxidil 5% and adenosine 0.75% solutions on male androgenetic alopecia and measuring patient satisfaction rate. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2013, 21, 155-159.

- Iwabuchi, T.; Ideta, R.; Ehama, R. et al. Topical adenosine increases the proportion of thick hair in Caucasian men with androgenetic alopecia. J. Dermatol. 2016, 43, 567-570. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Nagashima, T.; Hanzawa, N.; et al. Topical adenosine increases thick hair ratio in Japanese men with androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 37, 579-587. [CrossRef]

- Garre, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of a New Topical Hair Loss-Lotion Containing Oleanolic Acid, Apigenin, Biotinyl Tripeptide-1, Diaminopyrimidine Oxide, Adenosine, Biotin and Ginkgo biloba in Patients with Androgenetic Alopecia and Telogen effluvium: A Six-month Open-Label Prospective Clinical Study. J. Cosmo. Trichol. 2018, 4. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Shin, J.Y.; Choi, Y.H.; Joo, J.H.; Kwack, M.H.; Sung, Y.K.; Kang, N.G. Hair Thickness Growth Effect of Adenosine Complex in Male/Female-Patterned Hair Loss via Inhibition of Androgen Receptor Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6534. [CrossRef]

- Welzel, J.; Wolff, H.H; Gehring, W. Reduction of telogen rate and increase of hair density in androgenetic alopecia by a cosmetic product: Results of a randomized, prospective, vehicle-controlled double-blind study in men. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1057-1064. [CrossRef]

- Sisto, T.; Bussoletti, C.; Celleno, L. Role of a Caffeine Shampoo in Cosmetic Management of Telogen Effluvium. J. Appl. Cosmetol. 2013, 31, 139-145.

- Merja, A.; Patel, N.; Patel, M.; Patnaik, S.; Ahmed, A.; Maulekhi, S. Safety and efficacy of REGENDIL™ infused hair growth promoting product in adult human subject having hair fall complaints (alopecia). J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 23, 938-948. [CrossRef]

- Oura, H.; Iino, M.; Nakazawa, Y.; et al. Adenosine increases anagen hair growth and thick hairs in Japanese women with female pattern hair loss: a pilot, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Dermatol. 2008, 35, 763-767. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yu, F.; Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Tan, J.; Shi, Q.; He, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Zhao, H. Anti-hair loss effect of a shampoo containing caffeine and adenosine. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 00, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Byeon, J.Y.; Choi, H.J.; Park, E.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Effectiveness of Hair Care Products Containing Placental Growth Factor for the Treatment of Postpartum Telogen Effluvium. Arch. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2017, 23, 73-78.

- Sawaya, M.E.; Shapiro, J. Alopecia: unapproved treatments or indications. Clin. Dermatol. 2000, 18, 177-186. [CrossRef]

- Tansathien, K.; Ngawhirunpat, T.; Rangsimawong, W.; Patrojanasophon, P.; Opanasopit, P.; Nuntharatanapong, N. In Vitro Biological Activity and In Vivo Human Study of Porcine-Placenta-Extract-Loaded Nanovesicle Formulations for Skin and Hair Rejuvenation. Pharmaceutics. 2022, 14, 1846. [CrossRef]

- Ringrow, H. Peptides, proteins and peeling active ingredients: exploring ‘scientific’ language in English and French cosmetics advertising. Études de Stylistique Anglaise 2017, 7, 183-210.

- Arroyo, M.D. Scientific language in skin-care advertising: Persuading through opacity. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada 2013, 26, 197-214.

- Fowler, J.G.; Reisenwitz, T.H.; Carlson, L. Deception in cosmetics advertising: Examining cosmetics advertising claims in fashion magazine ads. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 2015, 6, 194–206. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. What Is Science-Washing, And Can The Beauty Industry Do Anything About It? Beauty Independent , 18 Apr. 2022. https://www.beautyindependent.com/what-science-washing-can-the-beauty-industry-do-anything/.

- Mehtonen, R. Science-washing in Skincare Marketing. University of Helsinki, 2024.

- Wong M. Scientism or “Science-Washing” in Beauty. Lab Muffin Beauty Science. April 14, 2019. Accessed September 5, 2025. https://labmuffin.com/scientism-or-science-washing-in-beauty/.

- Siegel, S.T.; Terdenge, J. The Fine art of Detecting Sciencewashing: Definition, Consequences, Forms & Prevention. . Journal Trends und Themen aus der Wissenschaftskommunikation 2023, 1-4.

- Crowther, T. Science-washing: The flawed ways beauty brands are marketing products Cosmetics Business 2024.

- Murphy, L.A.; White, I.R.; Rastogi, S.C. Is hypoallergenic a credible term? Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2004, 29, 325-327. [CrossRef]

- Boozalis, E.; Patel, S. Clinical utility of marketing terms used for over-the-counter dermatologic products. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2018, 29, 841-845. [CrossRef]

- Draelos, Z.D. Cosmeceuticals. In Evidence-Based Procedural Dermatology, Alam, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2019; pp. 479–497.

- Malinowska, P. Dermocosmetic packaging as an instrument of marketing communication. Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Poznańskiej. Organizacja i Zarządzanie 2020, 82, 159-171. [CrossRef]

- Hiranput, S.; McAllister, L.; Hill, G.; Yesudian, P.D. Do hypoallergenic skincare products contain fewer potential contact allergens? Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 49, 386-387. [CrossRef]

- Pokorska, P.; Śpiewak, R. Analiza składu kosmetyków rekomendowanych przez Polskie Towarzystwo Dermatologiczne oraz Polskie Towarzystwo Alergologiczne pod kątem występowania substancji o znanym potencjale uczulającym. Alergol. Immunol. 2012, 9, 227-232.

- Nurzyńska, M.; Śpiewak, R. The assessment of declared compositions of skin care products recommended by the Children’s Health Center and the Institute of Mother and Child with regard to the presence of ingredients with known sensitizing potential. Estetol. Med. Kosmetol. 2013, 3, 004.en. [CrossRef]

- Mosahebi, A. Commentary on: The Fountain of Stem Cell-Based Youth? Online Portrayals of Anti-Aging Stem Cell Technologies. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2015, 35, 737-738. [CrossRef]

- Kashihara, H.; Nakayama, T.; Hatta, T.; Takahashi, N.; Fujita, M. Evaluating the Quality of Website Information of Private-Practice Clinics Offering Cell Therapies in Japan. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2016, 5, e15. [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, B.; Zarzeczny, A.; Caulfield, T. Exploiting science? A systematic analysis of complementary and alternative medicine clinic websites’ marketing of stem cell therapies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019414. [CrossRef]

- Kent, D.M. Overall average treatment effects from clinical trials, one-variable-at-a-time subgroup analyses and predictive approaches to heterogeneous treatment effects: Toward a more patient-centered evidence-based medicine. Clin. Trials 2023, 20, 328-337. [CrossRef]

- Finocchiaro, M.A. The fallacy of composition: Guiding concepts, historical cases, and research problems. J. Appl. Logic. 2015, 13, 24-43. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Du, B.; Xiao, S.E.; Hu, Y.; Hu, Z. 6-Gingerol inhibits hair shaft growth in cultured human hair follicles and modulates hair growth in mice. PLoS One 2013, 8, e57226. [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Miao, Y.; Ji, H.; Wang, S.; Liang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Hong, W. 6-Gingerol inhibits hair cycle via induction of MMP2 and MMP9 expression. An Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017, 89, 2707-2717. [CrossRef]

- Haslam, I.S.; Hardman, J.A.; Paus, R. Topically Applied Nicotinamide Inhibits Human Hair Follicle Growth Ex Vivo. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1420-1422. [CrossRef]

- Oblong, J.E.; Peplow, A.W.; Hartman, S.M.; Davis, M.G. Topical niacinamide does not stimulate hair growth based on the existing body of evidence. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2020, 42, 217-219. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Kang, N.G.; Lee, S. Niacinamide Down-Regulates the Expression of DKK-1 and Protects Cells from Oxidative Stress in Cultured Human Dermal Papilla Cells. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 1519-1528. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.G.; Piliang, M.P.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Caterino, T.L.; Fisher, B.K.; Sacha, J.P.; Carr, G.J.; Moulton, L.T.; Whittenbarger, D.J.; Schwartz, J.R. Scalp application of antioxidants improves scalp condition and reduces hair shedding in a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2021, 43 Suppl 1, S14-S25. [CrossRef]

- Khare, S. Efficacy of Dr. SKS Hair Booster Serum in the Treatment of Female Pattern Alopecia in Patients With PCOS: An Open-Label, Non-randomized, Prospective Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e44941. [CrossRef]

- Khare, S. The Efficacy and Safety of Dr. SKS Hair Booster Serum (a Cocktail of Micronutrients and Multivitamins) in Adult Males and Females With Androgenetic Alopecia: An Open-Label, Non-randomized, Prospective Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e37424. [CrossRef]

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Plants of the World Online. https://powo.science.kew.org/results?q=Curcuma (electronic document, accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Vaughn, A.R.; Branum, A.; Sivamani, R.K. Effects of Turmeric (Curcuma longa) on Skin Health: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Evidence. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1243-1264. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Anwar, M.J.; Maity, M.K.; Azam, F.; Jaremko, M.; Emwas, A.H. The Dynamic Role of Curcumin in Mitigating Human Illnesses: Recent Advances in Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17, 1674. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Lee, J.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin in Cancer Prevention: Insights from Clinical Trials and Strategies to Enhance Bioavailability. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2024, 30, 1838-1851.

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Latini, G.; Ferrante, L.; Nardelli, P.; Malcangi, G.; Trilli, I.; Inchingolo, F.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.D. The Effectiveness of Curcumin in Treating Oral Mucositis Related to Radiation and Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Abbastabar, M.; Alaghi, A.; Heshmati, J.; Crowe, F.L.; Sepidarkish, M. Curcumin on Human Health: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 103 Randomized Controlled Trials. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 6048-6061. [CrossRef]

- Ayub, H.; Islam, M.; Saeed, M.; Ahmad, H.; Al-Asmari, F.; Ramadan, M.F.; Alissa, M.; Arif, M.A.; Rana, M.U.J.; Subtain, M.; et al. On the health effects of curcumin and its derivatives. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 8623-8650. [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Kameswaran, S.; Ramesh, B.; Bangeppagari, M.; Nath, R.; Das Talukdar, A.; Shin, H.S.; Patra, J.K. Anti-Aging Effect of Traditional Plant-Based Food: An Overview. Foods 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pumthong, G.; Asawanonda, P.; Varothai, S.; Jariyasethavong, V.; Triwongwaranat, D.; Suthipinittharm, P.; Ingkaninan, K.; Leelapornpisit, P.; Waranuch, N. Curcuma aeruginosa, a novel botanically derived 5alpha-reductase inhibitor in the treatment of male-pattern baldness: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2012, 23, 385-392. [CrossRef]

- Suphrom, N.; Pumthong, G.; Khorana, N.; Waranuch, N.; Limpeanchob, N.; Ingkaninan, K. Anti-androgenic effect of sesquiterpenes isolated from the rhizomes of Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 864-871. [CrossRef]

- Suphrom, N.; Srivilai, J.; Pumthong, G.; Khorana, N.; Waranuch, N.; Limpeanchob, N.; Ingkaninan, K. Stability studies of antiandrogenic compounds in Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb. extract. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014, 66, 1282-1293. [CrossRef]

- Srivilai, J.; Phimnuan, P.; Jaisabai, J.; Luangtoomma, N.; Waranuch, N.; Khorana, N.; Wisuitiprot, W.; Scholfield, C.N.; Champachaisri, K.; Ingkaninan, K. Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb. essential oil slows hair-growth and lightens skin in axillae; a randomised, double blinded trial. Phytomedicine 2017, 25, 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Kanase, V.; Khan, F. An overview of medicinal value of curcuma species. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 40-45. [CrossRef]

- Abia, W.A.; Haughey, S.A.; Radhika, R.; Taty, B.P.; Russell, H.; Carey, M.; Maestroni, B.M.; Petchkongkaew, A.; Elliott, C.T.; Williams, P.N. Africa, an Emerging Exporter of Turmeric: Combating Fraud with Rapid Detection Systems. Foods 2025, 14, 1590. [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.; Wang, Y.; Eachempati, P.; Iorio, A.; Murad, M.H.; Hultcrantz, M.; Chu, D.K.; Florez, I.D.; Hemkens, L.G.; Agoritsas, T.; et al. Core GRADE 4: rating certainty of evidence-risk of bias, publication bias, and reasons for rating up certainty. BMJ 2025, 389, e083864. [CrossRef]

- Terán-Bustamante, A.; Martínez-Velasco, A.; López-Fernández, A.M. University–Industry Collaboration: A Sustainable Technology Transfer Model. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 142. [CrossRef]

- Pujotomo, D.; Syed Hassan, S.A.H.; Ma’aram, A.; Sutopo, W. University–industry collaboration in the technology development and technology commercialization stage: a systematic literature review. J. Appl. Res. Higher Educ. 2023, 15, 1276-1306. [CrossRef]

- Steel, D. If the Facts Were Not Untruths, Their Implications Were: Sponsorship Bias and Misleading Communication. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J 2018, 28, 119-144. [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E. The deception and fallacies of sponsored randomized prospective double-blinded clinical trials: the bisphosphonate research example. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2014, 29, e37-44. [CrossRef]

- Rollins, N.; Piwoz, E.; Baker, P.; Kingston, G.; Mabaso, K.M.; McCoy, D.; Ribeiro Neves, P.A.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Richter, L.; Russ, K.; et al. Marketing of commercial milk formula: a system to capture parents, communities, science, and policy. Lancet 2023, 401, 486-502. [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.; Antonio, B.; Aragon, A.; Bustillo, E.; Candow, D.; Collins, R.; Davila, E.; Durkin, B.; Kalman, D.; Lockwood, C.; et al. “Common questions and misconceptions about dietary supplements and the industry - What does science and the law really say?”. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2534128. [CrossRef]

- Vojvodic, S.; Kobiljski, D.; Srdenovic Conic, B.; Torovic, L. Landscape of Herbal Food Supplements: Where Do We Stand with Health Claims? Nutrients 2025, 17, 1571. [CrossRef]

- Pappas, C.; Williams, I. Grey Literature: Its Emerging Importance. J. Hosp. Librarianship 2011, 11, 228-234. [CrossRef]

- Paez, A. Grey literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. J Evid Based Med 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kolaski, K.; Logan, L.R.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews. BMC Infect Dis. 2023, 23, 383. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mao, R.; Huang, H.; Dai, Q.; Zhou, X.; Shen, H.; Rong, G. Processes, challenges and recommendations of Gray Literature Review: An experience report. Information Software Technol. 2021, 137, 106607. [CrossRef]

| PICO criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Patients/Participants | People suffering from baldness, hair loss, effluvium or alopecia |

| Intervention | Ingredients of interest tested in topical anti-hair loss preparations |

| Comparator/Control | Placebo or other topical anti-hair loss preparations, no comparator |

| Outcomes | Phototrichogram, trichoscopy, investigator assessment (IA), participant assessment (PA) |

| Ingredient | CAS number | Origin | N | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achillea millefolium extract | 84082-83-7 | Plant | 5 | 4 |

| Adenosine | 58-61-7 | Animal, various | 3 | 3 |

| Aloe barbadensis | 85507-69-3 | Plant | 6 | 2 |

| Arginine | 74-79-3 | Synthetic, plant, animal | 4 | 4 |

| Biotin | 58-85-5 | Synthetic, plant | 10 | 2 |

| Caffeine | 58-08-2 | Synthetic, plant | 7 | 6 |

| Calcium pantothenate | 137-08-6 | Synthetic, natural | 5 | 2 |

| Capsicum | 85940-30-3 | Plant | 9 | 7 |

| Cinchona succirubra bark extract | 84776-28-3 | Plant | 3 | 3 |

| Citrus paradisi extract | 90045-43-5 | Plant | 2 | 2 |

| Gardenia jasminoides meristem cell culture | - | Plant | 2 | 2 |

| Glycine soja germ extract | - | Plant | 2 | 2 |

| Humulus lupulus extract | 8060-28-4 | Plant | 5 | 2 |

| Hydrolyzed collagen | 92113-31-0 | Animal | 5 | 4 |

| Hydrolyzed keratin | 69430-36-0 | Animal, plant | 6 | 2 |

| Hydrolyzed soy protein | 68607-88-5 | Plant | 5 | 2 |

| Hydrolyzed wheat protein | 94350-06-8 | Plant | 6 | 2 |

| Lavandula Angustifolia oil | 8000-28-0 | Plant | 2 | 2 |

| Melaleuca Ericifolia Oil | 85085-48-9 | Plant | 2 | 2 |

| Malus domestica fruit cell culture | - | Plant | 5 | 3 |

| Medicago sativa extract | 84082-36-0 | Plant | 2 | 2 |

| Melatonin | 73-31-4 | Synthetic | 4 | 3 |

| Menthol | 1490-04-6 | Plant | 11 | 3 |

| Panax ginseng root extract | 84650-12-4 | Plant | 6 | 2 |

| Panicum milialecum | 90082-36-3 | Plant | 2 | 2 |

| Panthenol | 81-13-0 | Synthetic | 23 | 2 |

| Piroctone olamine | 68890-66-4 | Synthetic | 2 | 2 |

| Placental protein | 84195-59-5 | Animal | 5 | 3 |

| Prunus amygdalus dulcis oil | 8007-69-0 | Plant | 4 | 4 |

| Rosmarinus officinalis leaf extract | 84604-14-8 | Plant | 9 | 6 |

| Royal jelly | 8031-67-2 | Animal | 2 | 2 |

| Serenoa serrulata fruit extract | 84604-15-9 | Plant | 11 | 8 |

| Tocopherol | 1406-66-2 | Plant, synthetic | 7 | 2 |

| Tocopheryl acetate | 7695-91-2 | Plant, synthetic | 11 | 2 |

| Tussilago farfara extract | 84625-50-3 | Plant | 3 | 3 |

| Urtica dioica extract | 84012-40-8 | Plant | 9 | 3 |

| Hair problem |

Main features | Diagnostic methods used | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Androgenetic alopecia |

Miniaturization of hair follicles in androgen-dependent areas | Dermatoscopy, trichoscopy | [44–47,49–66] |

| Telogen effluvium |

It occurs about three months after the triggering factor, e.g., infection, drug use, hormonal disorders, metabolic diseases, nutritional deficiencies, or stress | Positive pull test, trichogram, laboratory tests for underlying conditions | [48,64,67] |

| Hair loss (unspecified) |

Losing more hair than usual for longer than three months | Positive pull test, trichogram, laboratory tests for underlying conditions | [44,49,68] |

| Female pattern hair loss | Miniaturization of hair follicles in androgen-dependent areas | Dermatoscopy, trichoscopy | [51,69] |

| Thinning hair | A noticeable reduction in hair density | Dermatoscopy, trichoscopy | [70] |

| Diffuse alopecia |

A large number of hairs prematurely entering the telogen phase, resulting in diffuse hair loss | Dermatoscopy, trichoscopy | [45] |

| Postpartum hair loss | Typically occurs about three months after childbirth | Positive pull test, trichogram, laboratory tests for underlying conditions | [71] |

| Ingredient | Total participants |

GRADE | Overall conclusions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine | 466 | Tested individually: - moderate: 2 trials [63,69] - low: 2 trials [61,62] Tested in complex products: - low: 2 trials [65,70] - very low: 1 trial [64] |

Published trials seem to support the effectiveness of topical adenosine products against hair loss | [18] |

| Caffeine | 684 | Tested individually: - moderate: 1 trial [56] - low: 1 trial [57] - very low: 2 trials [58,67] Tested in complex products: - moderate: 2 trials [66,70] - very low: 3 trials [59,60,68] |

Published trials seem to support the effectiveness of topical caffeine products against hair loss | [14] |

| Placenta derivatives | 127 | Tested individually: - low: 2 trials [55,73] Tested in complex products: - very low: 1 trial [71] |

Published trials seem to support the effectiveness of topical placenta products in both stopping hair loss and stimulating hair growth | [41] |

| Patients | Intervention | Comparator | Outcome (reviewers’ summary) | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 F with AGA |

Melatonin 0.1% alcoholic solution (leave-on) | Alcohol | After 6 months of treatment, significantly higher anagen rate (85.0%) in mean occipital hair of melatonin-treated group than placebo (82.1%, p=0.012). A reverse tendency in frontal hair (80.4% versus 84.9%; ns). | moderate |

| 28 F with DA |

Melatonin 0.1% alcoholic solution (leave-on) | Alcohol | After 6 months of treatment, significantly higher anagen rate (83.8%) in mean frontal hair of melatonin-treated group than placebo (81.1%, p=0.046). A reverse tendency in occipital hair (83.7% versus 84.9%; ns). | moderate |

| Study design | Patients | Intervention | Comparator | Major outcomes | GRADE | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-center, uncontrolled | 18 P with AGA, hair loss and thinning hair | Marketed hair lotion (leave-on) with biotin, thioglycoran, HUCP1, thurfyl nicotinate, sodium pantothenate (undiscl. conc.) | None | After 60 d: incr. anagen hair ratio (p<0.001), incr. growth rate (p<0.001). | very low | [49] |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

20 M with AGA | Lotion (leave-on) with piroctone olamine (0.25%), triclosan (0.3%) | None | HCD index sign. decr. after 6 m. of treatment (-22.2%, p<0.05) and further on. Negative logarithmic correlation (r=-0.64, p<0.01) between time of treatment and HCD index. | very low | [52] |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

30 M and F with AGA |

Lotion (leave-on) with melatonin 0.0033%, Ginkgo biloba (undiscl. conc.), biotin (undiscl. conc.) | None | Investigator assessment of alopecia severity decr. after 30 d. (-34.1%, p<0.001) and 60 d. (-39.0, p<0.001). P assessment of alopecia severity decr. after 30 d. (-68.3%, p<0.001) and 60 d. (-75.1%, p<0.001). |

very low | [44]2 |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled | 35 M with AGA | Incr. hair density after 3 m. (+29.1%, p<0.001) and 6 m. (+40.9%, p<0.001). Rate of P satisfied (mostly satisfied) with the shampoo 93.2% after 3 m.: and after 6 m. |

very low | |||

| Multi-center, open-label, uncontrolled | 60 M and F hair loss or thinning hair | Hair stylist assessment after 90 d.: impr. of hair texture score by 18.5% (p<0.001), impr. hair loss score by 11.8% (p<0.001). | very low | |||

| Multi-center, open-label, uncontrolled | 1800 M and F with AGA | Investigator assessment: proportion of P with severe and moderate hair loss decr. from 61.6% at the beginning to 33.7% after 30 d. (p<0.001) and to 7.8% after 90 d. (p<0.001). Proportion of P with no hair loss incr. from 12.2% to 25.5% after 30 d. (p<0.001) and 61.5% after 90 d. (p<0.001). | very low | |||

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

50 M with AGA |

Marketed serum (leave-on) and shampoo (rinse-off) with Serenoa serrulata, green tea extract, peony root extract, piroctone olamine, oligopeptides (undiscl. conc.) | None | Sign. incr. in hair density after 6 w (+21.5%, p<0.001) and 12 w (+74.1%, p<0.001). | very low | [54] |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

25 F with postpartum hair loss |

Shampoo (rinse-off) and tonic (leave-on) with equine placental growth factor (PIGF), pumpkin extract, panthenol, and niacinamide (undiscl. conc.) | None | After 3 m.: increased vertex hair thickness (+5.6%, p=0.028), increased occipital hair density (+8.1%, p<0.001) | very low | [71] |

| Single-center, open-label, prospective uncontrolled |

56 M and F with AGA (36 P) and TE (24 P) |

Lotion (leave-on) with oleanolic acid, apigenin, biotinyl tripeptide-1, 2-4-diamino pyrimidine-3-oxide, adenosine, Ginkgo biloba, biotin (undiscl. conc.) | None | After 6 mo, 79% P reported reduced hair loss, 86% P were satisfied with the results | very low | [64] |

| Single center, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind |

120 M and F with AGA | Shampoo (rinse-off) and solution (leave-on) with Urtica urens leaf extract, Urtica dioica root extract, Matricaria chamomilla flower extract, Achillea millefolium aerial part extract, Ceratonia siliqua fruit extract, Equisetum arvense leaf extract (undiscl. conc.) | Placebo shampoo and solution | After 6 mo, impr. anagen/telogen rate for both shampoo (sh) and solution (so, p<0.001). Efficacy ranking: sh+so> so > sh > placebo |

moderate | [46] |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

5 M with AGA |

Solution (leave-on) with MNX (10%), finasteride (0.1%), biotin (0.2%), caffeine citrate (0.05%) | None | After 6 mo, assessment by a non-blinded expert: clinical improvements “visually noticeable” in all 5 patients. A blinded physician rated the overall effect as +0.75 in 1 P, +1.00 in 2 P, and +1.25 in further 2 P on a scale where 0 means “no change”, +1 – “slightly incr.” and +2 “moderately incr.”. 100% P satisfied after 180 d of the treatment. |

very low | [50] |

| Randomized, double-blind, controlled |

16 M and 16 F with AGA | Marketed hair tonic (leave-on) with acetyl tetrapeptide-3, biochanin A (red clover extracts), Panax ginseng extract, Salvia officinalis oil (undiscl. conc.) | 3% MNX solution | Blinded experts’ assessment after 24 w: in the vertex area, hair status improved (from slightly to greatly) in 100% participants both in I and C groups, “excellent improvement” in 12.5% of the I group and 21.0% in C group (ns). In frontal area, hair status improved in 87.5% of I group and 85.0% in C group (ns). Incr. of terminal hair count in both I group (8.3%, p=0.009) and C group (8.7%, p=0.002), no significant differences between groups. Increased HMI in both groups: I (13.8%, p=0.008) and C (31.5%, p=0.026) at after 24 w, no difference between the two groups (p=0.158). |

moderate | [51] |

| Single-center, randomized, double-blind, controlled |

24 M with AGA |

Morning: 5% MNX lotion (leave-on) Evening: Lotion (leave-on) with Rosmarinus officinalis, Olea europaea, lipidosterolic extract of Serenoa serrulata (undiscl. conc.) |

5% MNX lotion (morning and evening) | Hair diameter bigger in I group than C group after 24 w (+19.0%, p=0.005) and 36 w. (23.9%, p=0.001). No significant changes in hair density. PA score significantly lower (better outcome) in I group than C group (for various questions decrease by 45.4% to 59.1%, p from 0.001 to 0.007). |

moderate | [53] |

| Multi-center, open-label, observational |

527 M and F with AGA |

Marketed cosmetic solution (leave-on) with DPNO, arginine, 6-O glucose linoleate (SP94), piroctone olamine, Vichy mineralizing water (undiscl. conc.) | None | After 3 mo, 89.0% P and 96.7% treating dermatologists satisfied with the product. | very low | [47] |

| Two-center, open, randomized, controlled |

100 F with positive pull test (TE) |

Marketed hair lotion (leave-on) with acetyl tetrapeptite-2, biotin, creatine, panthenol, pyridoxine HCl (undiscl. conc.); + marketed neutral shampoo (rinse-off) |

Marketed neutral shampoo only | After 8 w. decr. in density of telogen hairs higher in intervention group than controls (p=0.0465). Reduction in total number of hairs shed in 60 s larger in I group than in C group after 8 w. (-31.8% vs. -13.5%, p= 0.0392), and 16 w. (-43.6% vs. -33.1%, p=0.0584). No significant difference in Anagen/Telogen Ratio between I group and C group (p=0.320). | low | [48] |

| Randomized, controlled, double-blind |

62 M with AGA | Foam (leave-on) with polyphenols (DHQG and EGCG2), NHE, zinc salt (anion unspecified), glycine, caffeine (undiscl. conc.) | Vehicle | After 3 and 6 mo: stronger decrease in telogen rate in I group than C group (p=0.02). Increase in hair density observed in both I group (p=0.001) and C group (p=0.04). No significant differences between I and C. |

moderate | [66] |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

150 P with AGA (60 M and 90 W) | Marketed serum (leave-on) in a roller with caffeine, Serenoa serrulata, and 25 other ingredients (undiscl. conc.) | None | After 8 w, incr. thickness and density of crown and vertex hair (p<0.05), no significant changes in frontal hair. P satisfaction rates in various aspects of hair growth between 80-100%, except hair length (40%). |

very low | [59] |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

32 M and F with hair loss or alopecia |

Marketed hair serum (leave-on) with hydrolyzed wheat protein, hydrolyzed soy protein, caffeine, arginine, Rosmarinus officinalis leaf oil and 18 other ingredients (undiscl. conc.) | none | Incr. hair growth rate after 30 d. (+10.5%, p<0.01) and 60 d. (+31.6%, p<0.01). Incr. hair thickness after 30 d. (+24%, p<0.01) and 60 d. (+34%, p<0.01). Incr. hair density after 30 d. (+25%, p<0.01) and 60 d. (+40%, p<0.01). |

very low | [68] |

| Single-center, open-label, uncontrolled |

20 M with AGA | Liquid (leave-on) with Procapil™ 3%3, caffeine (undiscl. conc.), zinc PCA4 (undiscl. conc.) | None | After 12 wk.: a 26.9% decrease in hair loss (p=0.026), 53% increase in terminal/vellus hair ratio (p=0.028), no significant changes in anagen rate and density. Investigator assessment: improvement (slight to much) in 68.4% P. | very low | [60] |

| Single center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind |

46 P with AGA (27 M and 19 W) | Solution “APN” (leave-on) with adenosine (0.75%), panthenol (1%), niacinamide (2%) | Solution with MNX 5% | After 4 mo, incr. in hair density (I group: +6.2%, p<0.001; C group: +5.0%, p<0.01) and hair thickness (I: +10.3%, p<0.001; C: +5.1%, p<0.001). No direct comparisons I vs C. | low | [65] |

| Single center, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind |

84 M and F with self-perceived “thinning hair” |

Shampoo (rinse-off) with caffeine (0.4%) and adenosine (0.2%) | Placebo shampoo | After 3 mo, hair density incr.by 10.2%, hair loss decr. by 35.5% (each p<0.001 as compared with baseline and C group) | low | [70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).