1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, when the initial cluster of pneumonia cases was reported. Chinese authorities notified the World Health Organization (WHO) on January 7, 2020, and the disease was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, followed by a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 [

1,

2]. From that point onward, infection numbers increased exponentially—first in China and rapidly across the world [

3].

In Spain, the first confirmed case was reported on January 31, 2020. Within weeks, the country experienced one of the most severe outbreaks in Europe. The Community of Madrid became the epicenter, with more than 64,000 confirmed cases by May 2020 [

4,

5]. The Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM), one of Madrid’s largest tertiary referral centers, was among the institutions most affected, facing critical overload during the first epidemic wave.

The pandemic’s rapid escalation profoundly disrupted healthcare practice. Hospitals across Spain and worldwide were forced to reorganize clinical workflows and redistribute staff and infrastructure. Non-urgent surgeries and outpatient activity were suspended, while healthcare professionals were redeployed to COVID-19 units and intensive care wards [

6,

7]. This abrupt transformation highlighted the urgent need for alternative mechanisms to ensure care continuity while minimizing exposure risk.

Telemedicine, although conceptually established since the mid-20th century and introduced into neurosurgery in the 1990s [

8,

9], had remained marginal before 2020. The COVID-19 crisis acted as a powerful catalyst for its adoption, dismantling long-standing barriers such as insufficient digital infrastructure, lack of training, and regulatory uncertainty. Early reports confirmed its potential to preserve continuity of care, reduce unnecessary hospital visits, and mitigate transmission risk [

10,

11,

12].

Neurosurgery was among the most affected specialties, due to operating room restrictions and personnel reallocation to COVID-19 care, which led to the suspension of elective and outpatient procedures [

13,

14]. Similar telemedicine initiatives emerged worldwide to sustain patient follow-up during lockdown [

15,

16,

17]. In Spain, the transition occurred swiftly and organically, driven by institutional necessity and supported by regional digital health initiatives [

18,

19].

At HGUGM, the Department of Neurosurgery transitioned its outpatient activity to remote telephone consultations within days, ensuring uninterrupted patient care. What began as an emergency adaptation evolved into a stable, scalable digital workflow that persists five years later. Similar trends have been observed in other Spanish hospitals across multiple specialties, where telemedicine remains integrated into hybrid care models [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

This study describes the rapid implementation and clinical outcomes of telemedicine in neurosurgical outpatient care at HGUGM during the first wave of COVID-19. It provides quantitative evidence of care adaptation, examines univariate and multivariate factors associated with follow-up and surgical indication, and contextualizes the long-term role of telemedicine in consolidating a hybrid model of neurosurgical practice in Spain.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective observational study evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on neurosurgical outpatient activity and analyzed the rapid implementation of telemedicine in a tertiary referral hospital. It was conducted at the Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM), Madrid, Spain—one of the largest tertiary centers in the region and among those most affected during the first epidemic wave of COVID-19. Two cohorts were compared: the pandemic cohort (2020), comprising 3,105 patients who received telemedicine consultations between March 1 and May 31, 2020, and the pre-pandemic cohort (2019), including 2,074 patients attended in person during the same months of 2019. The total study population consisted of 5,179 patients. In both groups, six-month follow-up data were reviewed to assess continuity of care, adherence to recommended reviews, and potential delays in clinical management.

Eligible participants were adult patients (≥18 years) scheduled and evaluated in the Neurosurgery Outpatient Department during either the first wave of the pandemic (March 2–May 29, 2020) or the corresponding period in 2019. Exclusion criteria included incomplete clinical documentation, absence of follow-up data, or missing initial or six-month consultations. Data were retrieved from the hospital’s electronic medical record system (HCIS®, DXC Technology, Tysons, VA, USA) and compiled into a structured database specifically developed for this study. The dataset included demographic, clinical, and temporal variables for all patients scheduled in both periods, allowing a comprehensive comparison of outpatient activity, consultation modality (in-person vs. teleconsultation), pathology type, and clinical outcomes. Longitudinal follow-up data up to six months after the initial consultation enabled evaluation of care continuity, outcomes, and timing of re-evaluation.

The analyzed variables included demographic factors (age, sex), temporal indicators (week, month, and year of consultation), and clinical parameters such as type of scheduled visit (new, results, follow-up, or telephonic), underlying pathology (traumatic, tumoral, degenerative, vascular, functional, cerebrospinal fluid disorders, or others), and consultation outcomes (diagnostic test request, follow-up, discharge, or surgical indication). Six-month follow-up adequacy was categorized as on time (within the physician-recommended period), delayed (beyond the recommended time), no-show, or other. All variables were analyzed for both cohorts, and descriptive and comparative summaries were compiled in tables (Tables 1–3).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize all data. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) when normally distributed or as median and interquartile range (IQR) otherwise, while categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies (%). Comparisons between qualitative variables were performed using Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate, and quantitative comparisons were conducted with Student’s t-test for parametric data. A univariate analysis was performed to explore associations between clinical variables (pathology type, consultation outcome, and follow-up adequacy) and consultation modality (in-person vs. telemedicine), calculating odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A multivariate logistic regression model was subsequently applied to identify independent predictors of delayed follow-up and surgical indication. Variables with p < 0.10 in univariate testing were entered into the model. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% CI were reported. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Given its retrospective design, the requirement for informed consent was waived. All patient data were anonymized prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality and compliance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR 2016/679) and the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 on Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological Context: National and Regional Infection Data

During the first epidemic wave of COVID-19 in Spain (March–May 2020), a total of 250,273 confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases were reported nationwide (

Table 1). The Community of Madrid registered the highest number of infections (64,408), followed by Catalonia (55,196), Castilla y León (23,192), and Castilla-La Mancha (20,477), while smaller regions such as Asturias and the Balearic Islands presented considerably lower incidence rates (Equipo COVID-19, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, 2020) [

4].

This distribution underscores the disproportionate impact of the pandemic in Madrid, which became one of Europe’s main epicenters. Consequently, tertiary hospitals such as the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM) faced extraordinary healthcare pressure, requiring rapid structural reorganization and the introduction of telemedicine to sustain outpatient activity.

3.2. Patient Demographics and Consultation Distribution

A total of 5,175 neurosurgical outpatients were included—3,105 patients (60%) attended in 2019 (pre-pandemic cohort) and 2,070 (40%) in 2020 (pandemic cohort) (

Table 2). No statistically significant demographic differences were found between cohorts (p > 0.05). The mean age was 59 ± 15 years (2019: 59; 2020: 58), and sex distribution was similar (56% female, 44% male).

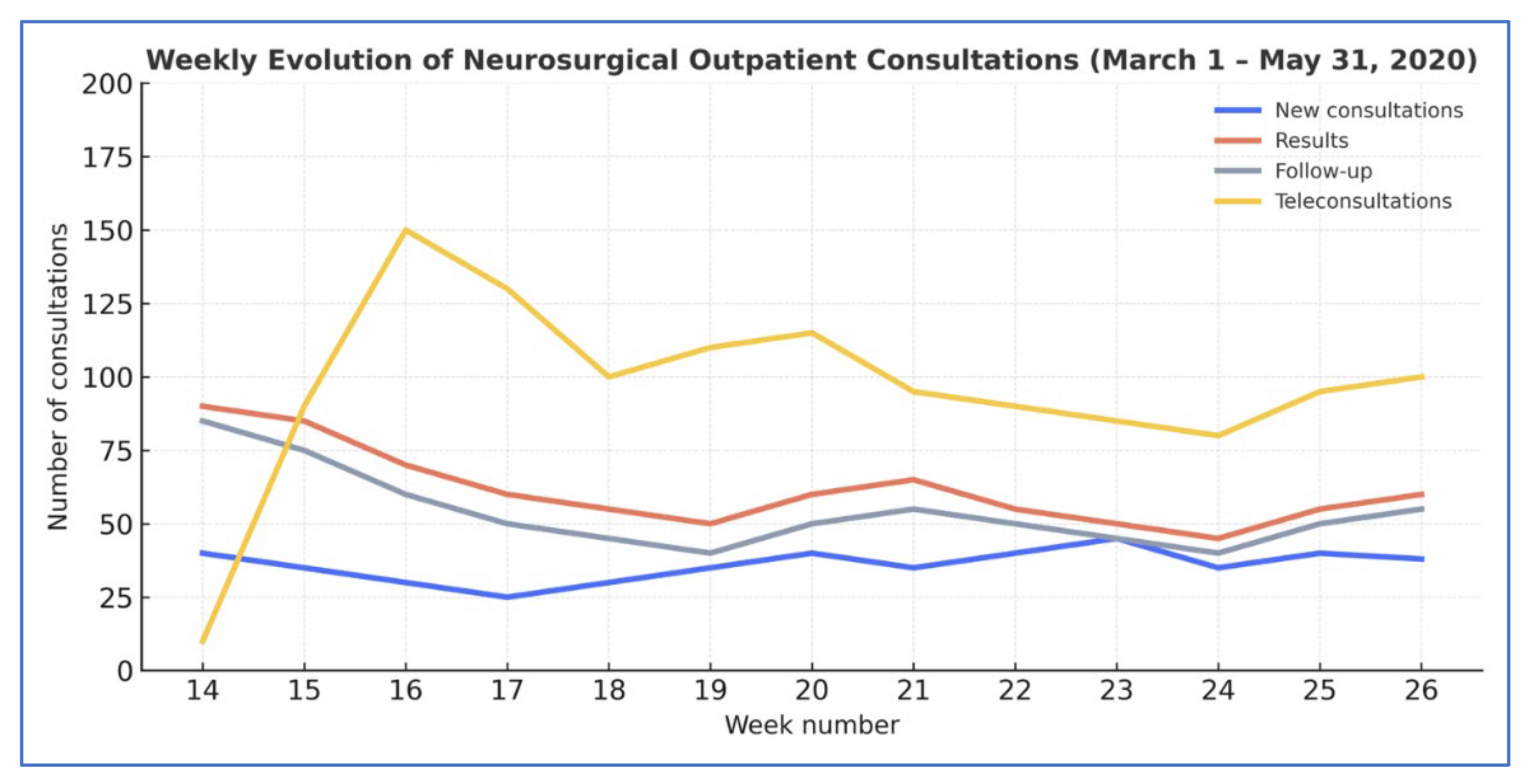

Weekly variation in neurosurgical consultations at HGUGM during the first COVID-19 wave (2020) versus 2019. 2019: in-person only (new; results, follow-up); 2020: in-person (same types and teleconsultations). X-axis = week number for each study year. The sharp increase in teleconsultations reflects the rapid transition to remote care at the onset of the pandemic.

Monthly outpatient volume declined sharply during 2020, paralleling the epidemiological curve of the pandemic (

Figure 1). Consultations fell from 981 in March to 611 in April and 478 in May (p < 0.001), showing a clear inverse relationship between infection surge and hospital attendance.

3.3. Consultation Types and Attendance

In 2019, the distribution of consultation types was consistent: new visits (21%), results (37%), and follow-ups (43%), all performed in person. In 2020, however, consultation dynamics changed dramatically (

Table 3;

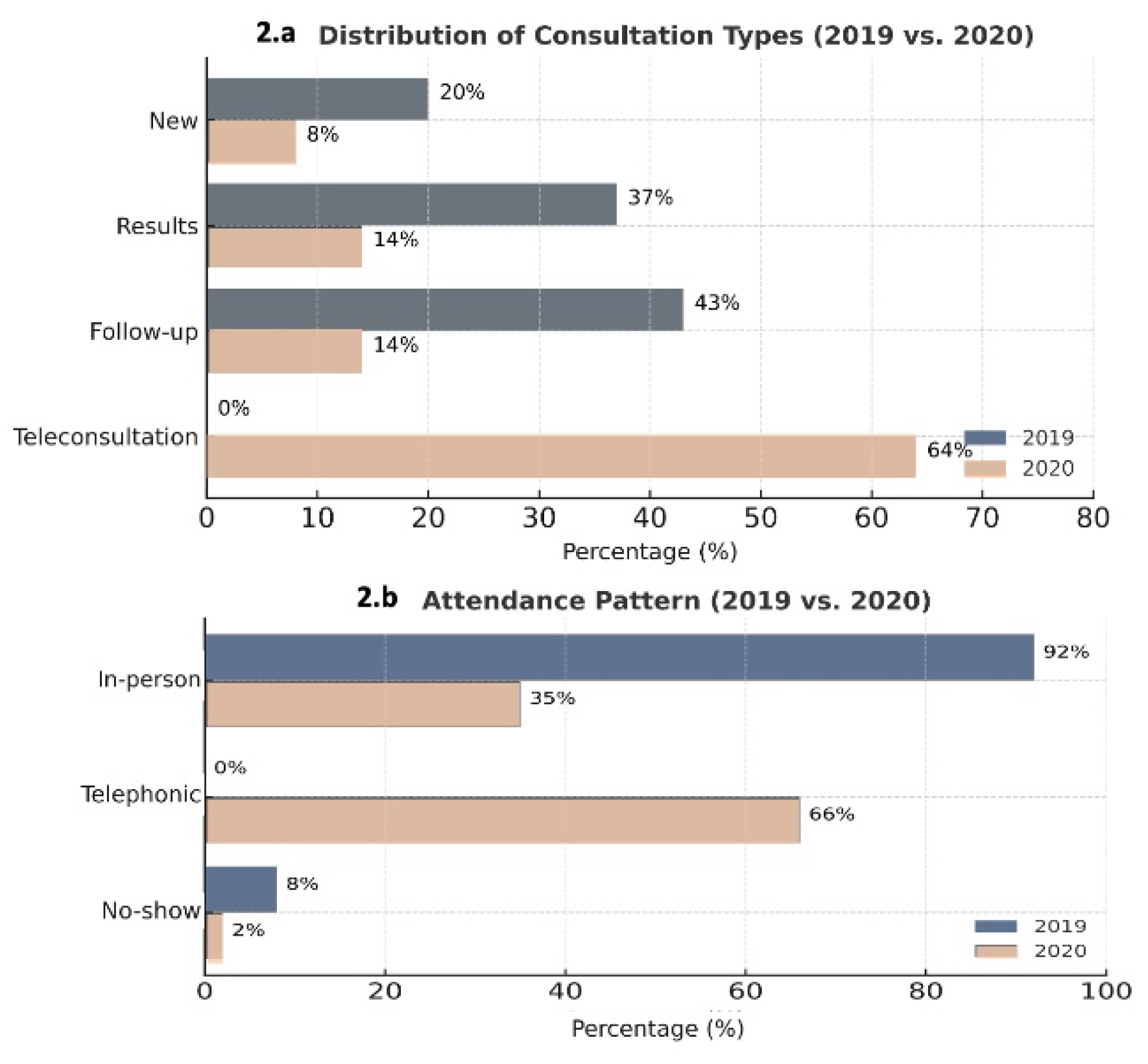

Figure 2).

Comparison of outpatient consultation categories (new, results, and follow-up) during March–May 2019 and the same months in 2020. Teleconsultations, nonexistent in 2019, represented over 70% of visits by May 2020, replacing most in-person appointments.

New consultations decreased from 14% in March to 1% in May (p < 0.001); results visits declined from 24% to 9% (p < 0.001); and follow-ups dropped from 21% to 14% (p < 0.001). In contrast, teleconsultations—non-existent in 2019—rapidly became predominant, representing 74% of total visits in April and 77% in May (p < 0.001).

Attendance patterns mirrored this shift. Face-to-face visits fell from 56% in March to 23% in May, while telephone consultations increased from 39% to 77%. Non-attendance, which had averaged 8% in 2019, declined to 0% by May 2020, indicating improved accessibility and compliance through remote care.

3.4. Distribution by Pathology Type and Disease Category

Analysis of clinical diagnoses revealed major shifts in case mix (

Table 4;

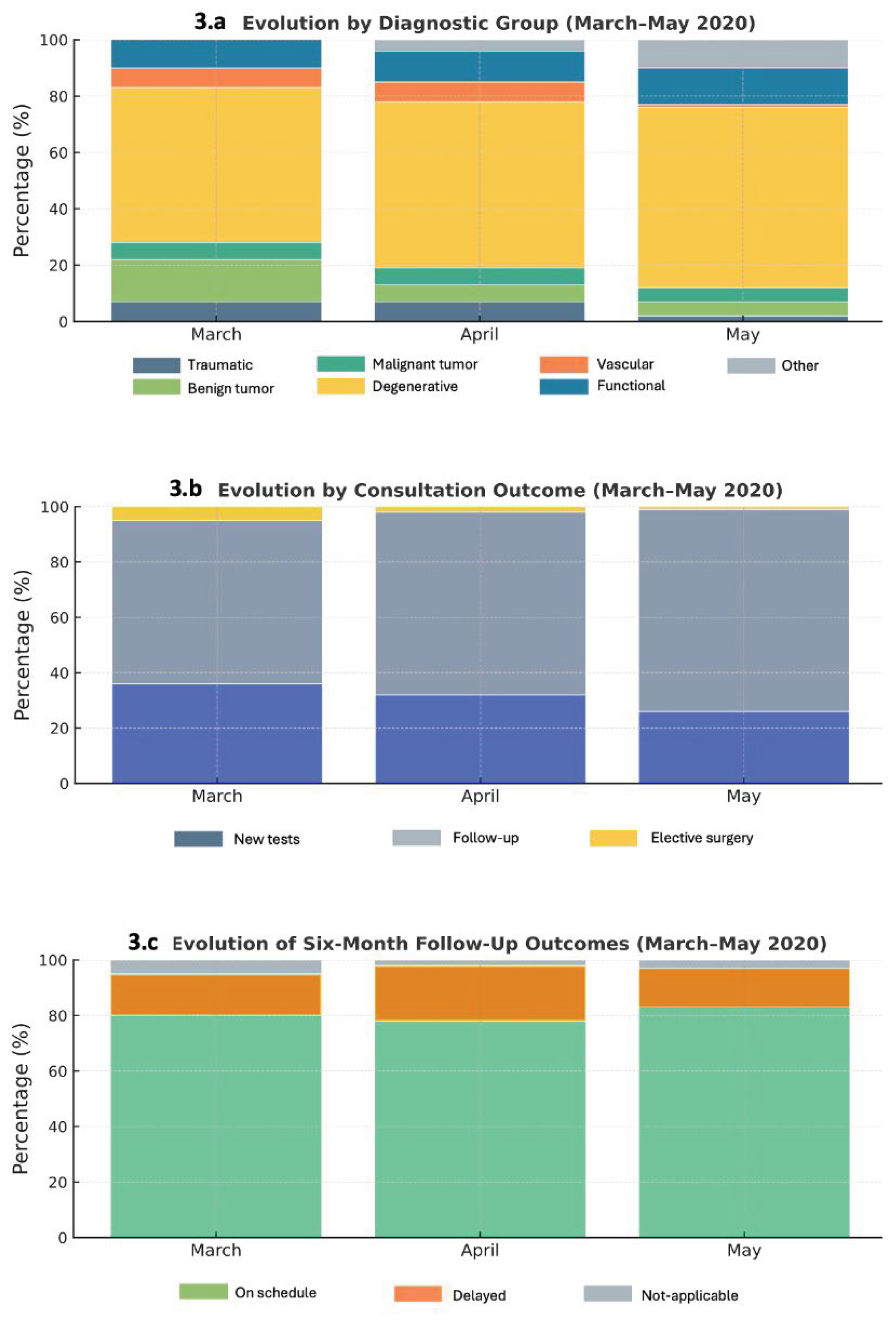

Figure 3A). All diagnostic categories decreased markedly across March–May 2020, consistent with the suspension of elective activity. Cranial pathologies dropped from 58% in March to 11% in May (p < 0.001), and spinal disorders from 56% to 12% (p < 0.001). Other pathologies—such as peripheral nerve, vascular, or functional disorders—fell from 74% to 14% (p < 0.001).

When grouped by oncological status, non-tumoral conditions declined from 46% in March to 25% in May (p < 0.001), and tumoral cases from 60% to 11% (p < 0.001). Within the tumoral subgroup, malignant lesions were preserved in relatively higher proportion compared with benign or degenerative disorders, reflecting clinical prioritization of urgent and high-risk cases.

It is important to note that acute neurosurgical conditions—including cranial trauma, hydrocephalus, and high-grade tumors—are typically managed through the emergency department rather than outpatient clinics. Therefore, their lower representation in this cohort does not indicate reduced care provision; rather it reflects the institution’s established triage and referral pathways.

Monthly evolution of neurosurgical outpatient activity at Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM) during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–May 2020): (A) distribution by diagnostic group, (B) consultation outcomes, and (C) six-month follow-up results

3.5. Consultation Outcomes

Marked differences were observed in consultation outcomes (

Figure 3B). Requests for diagnostic tests and surgical indications decreased significantly (p < 0.001), due to restricted access to imaging and operating rooms. Conversely, follow-up reviews increased proportionally, representing an adaptive response to maintain patient surveillance with limited hospital resources.

Surgical indications declined dramatically—from 74% in March to 3% in May (p < 0.001)—confirming that only urgent cases, mainly malignant tumors and acute cerebrospinal fluid disorders, were prioritized during lockdown.

3.6. Six-Month Follow-Up

At six months, adherence to follow-up remained high, with most patients reviewed within the recommended period (

Figure 3C). On-time reviews accounted for 81% in March and 83% in May, while delayed visits represented 15–20% of the total.

Teleconsultation was associated with a modest increase in delay rates (20.9% vs. 10.4% for in-person), yet overall adequacy remained comparable (77.3% vs. 83.4%). This pattern likely reflects the broader epidemiological context: as the pandemic progressed, telemedicine became the only viable form of consultation, naturally concentrating follow-up volume in remote modalities. Despite this, remote care effectively prevented patient loss to follow-up and maintained clinical continuity under crisis conditions.

3.7. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

The univariate analysis demonstrated significant associations between the pandemic period, consultation mode, and clinical outcomes (

Table 5). Tumoral (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.23–0.54; p < 0.001), degenerative (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.27–0.45; p < 0.001), and vascular (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.02–0.30; p < 0.001) pathologies significantly decreased during the pandemic months. Requests for diagnostic tests (OR 0.3; p < 0.001) and surgical indications (OR 0.7; p = 0.001) also declined, whereas follow-up visits increased (OR 0.4; p < 0.001). Delayed six-month reviews were twice as likely after teleconsultation (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.43–2.74; p < 0.001).

In the multivariate model (

Table 5), teleconsultation independently predicted delayed follow-up (aOR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3–2.8; p = 0.002) and a lower likelihood of surgical indication (aOR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.7; p = 0.004). Tumoral pathology remained the strongest predictor of surgical decision (aOR 3.6, 95% CI 2.1–5.9; p < 0.001), confirming that oncological status was the primary determinant of operative management during the pandemic.

4. Discussion

Although the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic occurred five years ago, the present study remains highly relevant. It documents one of the earliest structured experiences of telemedicine implementation in neurosurgical care in Spain, marking a turning point in the digital transformation of clinical practice [

20]. Beyond its historical significance, it provides a longitudinal perspective on how crisis-driven innovations evolved into sustainable care models. The lessons learned—rapid digital adaptation, hybrid patient management, and enhanced accessibility—are directly applicable to current healthcare priorities, including resilience, efficiency, and equity in digital medicine.

The abrupt onset of the pandemic in early 2020 led to an unprecedented collapse of hospital systems in Madrid, one of the hardest-hit regions in Europe [

25,

26]. Over 64,000 infections were recorded during the first wave, forcing hospitals such as the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM) to reorganize virtually overnight [

27,

28]. As reported by international studies, this situation prompted widespread disruption of elective and outpatient activity in neurosurgery [

13,

14,

29]. In this context, telemedicine emerged as the only feasible mechanism to ensure care continuity, patient safety, and infection control.

At HGUGM, the introduction of telephone-based teleconsultation was achieved within days, enabling more than 70% of neurosurgical visits to be performed remotely by May 2020. Despite a 40% reduction in total consultations, follow-up compliance exceeded 80%, and non-attendance rates fell to nearly zero. These results demonstrate both the feasibility and effectiveness of telemedicine in a highly specialized surgical discipline that had previously relied almost exclusively on in-person evaluation. Comparable experiences were described across international centers: De Biase et al. (2020) reported a 55% conversion to telemedicine in a U.S. tertiary center [

15] and Taha et al. (2021) in Australia observed similar adoption rates [

30]. In Europe, Apostolopoulou et al. (2022) described that over 80% of pediatric neurosurgical visits were conducted remotely during national lockdowns [

31]. The parallel evolution of these models underscores the universal capacity of telemedicine to maintain neurosurgical care during large-scale health crises.

Our findings reveal notable shifts in clinical case mix and care dynamics. Degenerative and benign spinal pathologies—normally predominant in neurosurgical outpatient practice—declined sharply, while malignant and urgent cranial cases were prioritized. It is important to note that acute trauma and emergency cranial cases are typically evaluated directly through emergency departments rather than outpatient clinics, both before and during the pandemic, explaining their lower representation in this study cohort. This selective maintenance of high-risk pathologies reflects rational triage strategies consistent with international guidelines and early recommendations from the COVIDSurg Collaborative (2020) [

32].

At the same time, restrictions on imaging and surgical capacity limited diagnostic and operative throughput. The significant reduction in surgical indications (p < 0.001) mirrors global trends reported by Kessler et al. (2020) [

33] and Jean et al. (2020) [

34], who documented the near-total suspension of non-urgent procedures during this phase. The six-month follow-up data further confirm that remote consultation preserved long-term care continuity. Although delayed reviews were twice as frequent among teleconsultation patients (20.9% vs. 10.4%), overall adequacy remained comparable (77% vs. 83%). This finding must be interpreted in context: as the pandemic advanced, teleconsultation became the dominant, and often the only, available mode of follow-up. Thus, the apparent delay reflects system-wide disruption rather than inefficiency of the telemedicine model itself. On the contrary, remote care allowed timely monitoring in circumstances where face-to-face evaluation was unfeasible, highlighting its role in mitigating clinical risk.

These figures align with those from Eichberg et al. (2020) [

35]and Vogt et al. (2022) [

11], who demonstrated that patient satisfaction, adherence, and safety outcomes in telemedicine neurosurgical follow-up were equivalent to in-person models. Importantly, in our cohort, no cases of clinical deterioration or diagnostic omission were reported due to teleconsultation, underscoring its reliability for stable or postoperative patients.

From a broader perspective, the experience at HGUGM was consistent with the evidence generated by the COVIDSurg Collaborative on perioperative risk, surgical delay, and postoperative outcomes during the pandemic [

32,

36]. These international data contextualize the ethical and logistical dilemmas faced by surgical teams: balancing infection risk, resource limitations, and the need to continue essential oncological or urgent interventions. In this regard, the telemedicine framework developed at HGUGM represented a practical and safe adaptation that preserved access while minimizing exposure.

Telemedicine also introduced long-term clinical and socioeconomic advantages. By reducing unnecessary hospital visits, it lowered patient travel burden, optimized scheduling, and facilitated multidisciplinary coordination—particularly valuable for chronic or postoperative neurosurgical cases. Moreover, it contributed to reducing nosocomial infection risk, not only for SARS-CoV-2 but also for other transmissible diseases. Economic analyses have demonstrated that telemedicine models improve efficiency and reduce healthcare expenditure [

10,

12], findings that are consistent with the operational experience at HGUGM.

From an institutional perspective, the introduction of telemedicine at HGUGM triggered a long-term reorganization that extended beyond the acute pandemic phase. Five years later, teleconsultation remains integrated into routine neurosurgical workflows—especially for postoperative reviews, communication of results, and follow-up of stable patients. Similar patterns of persistence in telemedicine use have been documented in Spanish clinical settings, supporting the notion that remote consultation models have achieved sustainability and acceptance across specialties. In line with institutional strategies, the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón and other hospitals in the Madrid Regional Health Service (SERMAS) have maintained teleconsultation systems as part of their post-pandemic digital care plans, citing improved accessibility, reduced waiting times, and enhanced infection control [

19,

37].

Altogether, this experience demonstrates that even under conditions of healthcare system collapse, rapid digital transformation is possible. Telemedicine enabled uninterrupted neurosurgical care, preserved patient safety, and laid the foundation for hybrid models that continue to define patient-centered care in modern healthcare systems.

5. Highlights

This study provides one of the earliest structured evaluations of telemedicine implementation in neurosurgical outpatient care in Spain. During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 70% of neurosurgical consultations were conducted remotely while maintaining follow-up adherence above 80%. Teleconsultation significantly reduced non-attendance and ensured continuity of care despite the collapse of in-person healthcare systems. The analysis revealed a sharp decline in degenerative and benign pathologies, while urgent and malignant cases were prioritized according to clinical severity. Five years later, telemedicine remains integrated into routine neurosurgical workflows, demonstrating its long-term sustainability and contribution to the development of modern hybrid healthcare models that enhance accessibility, efficiency, and resilience.

6. Strengths and Limitations

This study presents several methodological and contextual strengths. It includes a large, well-defined cohort with a direct year-to-year comparison (2019 vs. 2020) within a major tertiary neurosurgical center. The analysis integrates both univariate and multivariate models, providing quantitative insight into how clinical workflows and patient outcomes adapted to the abrupt digital transformation prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The inclusion of six-month follow-up data strengthens the evaluation of care continuity and highlights the long-term reliability of teleconsultation. Moreover, this work offers one of the earliest structured assessments of neurosurgical telemedicine implementation in Spain, contributing valuable evidence to the ongoing digital transformation of healthcare systems.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective and single-center design may limit generalizability, and patient satisfaction or diagnostic concordance were not formally measured. The exclusive use of telephone-based teleconsultations restricted direct imaging review and neurological examination, potentially affecting diagnostic precision in complex or newly presenting cases. Additionally, disparities in access to technology—particularly among elderly or socioeconomically disadvantaged patients—may have influenced the adoption of remote care. These challenges underscore the need for complementary hybrid models that combine digital innovation with equitable access and clinical rigor

7. Conclusions

Telemedicine proved to be a safe, efficient, and sustainable strategy to maintain neurosurgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the HGUGM, its rapid implementation ensured continuity of care despite the near collapse of in-person healthcare services. Although teleconsultation was associated with fewer surgical indications and slightly longer follow-up intervals, overall adherence exceeded 80%, and non-attendance dropped to zero, demonstrating preserved patient engagement and accessibility.

Five years later, teleconsultation remains integrated into routine neurosurgical workflows, particularly for postoperative reviews and long-term follow-up of stable patients. This sustained adoption confirms that telemedicine is not merely an emergency response but a structural innovation that has redefined the organization of neurosurgical outpatient care.

The HGUGM experience underscores the potential of digital transformation to strengthen healthcare resilience, optimize resource utilization, and extend equitable access to specialized services. The lessons learned from this model—rapid adaptability, hybrid patient management, and long-term continuity—illustrate how telemedicine has become a cornerstone of modern, patient-centered neurosurgical practice.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this manuscript. Conceptualization, Methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2020–2021 program for clinical research development).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Gregorio Marañón University Hospital Research Institute (protocol code TELEMATIC-NS-COVID19, approved on Madrid, March 31, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent was waived as the study involved a retrospective review and the use of anonymized data.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the staff of the Department of Neurosurgery and to the management and information systems teams of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón for their collaboration during the implementation of telemedicine services. The authors also acknowledge the support of the Gregorio Marañón University Hospital Research Institute and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid for their contribution to the development of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

aOR Adjusted odds ratio

CI Confidence interval

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease 2019

COVIDSurg COVIDSurg Collaborative

EU European Union

GDPR General Data Protection Regulation

HGUGM Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón

IQR Interquartile range

OR Odds ratio

SARS-CoV-2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

SD Standard deviation

SERMAS Servicio Madrileño de Salud (Madrid Regional Health Service)

WHO World Health Organization

References

- Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res 2020. [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. 2020. WHO n.d. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director- general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- Lan FY, Filler R, Mathew S, et al. COVID-19 symptoms predictive of healthcare workers’ SARS-CoV-2 PCR results. PLoS One 2022;17:e0262341. [CrossRef]

- Equipo Covid-19. Informe sobre la situación de COVID-19 en España. Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica Instituto de Salud Carlos III 2020.

- Pollán M, Pérez-Gómez B, Pastor-Barriuso R, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. The Lancet 2020;396:535–44. [CrossRef]

- Wong J, Goh QY, Tan Z, et al. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: a review of operating room outbreak response measures. Anesth Analg 2020;130:1409–20. [CrossRef]

- Kandel N, Chungong S, Omaar A, Xing J. Health security capacities in the context of COVID-19 outbreak: an analysis of International Health Regulations annual report data from 182 countries. The Lancet 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kahn EN, La Marca F, Mazzola CA. Telemedicine in neurosurgery: a systematic review. Neurosurgery 2016;79:613–24. [CrossRef]

- Shaver V, Shaver J, Yu P, Piatt JH. The role of telemedicine in neurosurgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev 2022;45:1223–40.

- Mandal I, Choudhury D. Telemedicine: A new normal after COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Technol 2022;11:100610.

- Vogt H, Tomic O, Haneef R. The expansion of telemedicine in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: patterns and predictors. BMJ Open 2022;12:e054870.

- Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, et al. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016242. [CrossRef]

- Ozoner B, Gungor A, Hasanov T, Toktas Z, Killic T. Neurosurgical practice during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. World Neurosurg 2020;140:198–207.

- Arnaout O, Patel A, Carter B, Chiocca EA. Adaptation under fire: Two harvard neurosurgical services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurosurgery 2020. [CrossRef]

- De Biase G, Freeman WD, Bydon M, Smith N, Jerreld D, Pascual J, Casler J, Hasse C, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Abode-Iyamah K. Telemedicine Utilization in Neurosurgery During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Glimpse Into the Future? Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2020;4:736–44. [CrossRef]

- Gadjradj PS, Matawlie RH, Harhangi BS. Letter to the Editor: The Use of Telemedicine by Neurosurgeons During the Covid Era: Preliminary Results of a Cross-Sectional Research. World Neurosurg 2020;139:746–8. [CrossRef]

- Abraham A, Jithesh A, Doraiswamy S, Al-Khawaga N, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Telemental Health Use in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review and Evidence Gap Mapping. Front Psychiatry 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Consejería de Sanidad de la Comunidad de Madrid. Datos COVID-19 Comunidad de MAdrid. 13/2/2021 2021. https://www.comunidad.madrid/sites/default/files/doc/sanidad/210213_cam_covid19.pdf.

- Consejería de Digitalización de la Comunidad de Madrid. Plan Estratégico de Madrid Digital 2022-26. Portal de Transparencia de La Comunidad de Madrid 2022.

- De Saracho Pantoja IO, Jonathan GM, Perjons E. Rapid response for lasting impact: Examining the digital transformation of Spain’s healthcare system post-COVID-19. Procedia Comput Sci 2025;256:344–51. [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo-Carreño H, Muñoz-Esquerre M, Santos Pérez S, Romero-Ortiz AM, Fabrellas N, Guix-Comellas EM. Impact of the implementation of a telemedicine program on patients diagnosed with asthma. BMC Pulm Med 2024;24:32. [CrossRef]

- Piera-Jiménez J, Dedeu T, Pagliari C, Trupec T. Strengthening primary health care in Europe with digital solutions. Aten Primaria 2024;56:102904. [CrossRef]

- Belvís R, Santos-Lasaosa S, Irimia P, Blanco RL, Torres-Ferrús M, Morollón N, López-Bravo A, García-Azorín D, Mínguez-Olaondo A, Guerrero Á, Porta J, Giné-Ciprés E, Sierra Á, Latorre G, González-Oria C, Pascual J, Ezpeleta D. Telemedicine in the management of patients with headache: current situation and recommendations of the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Headache Study Group. Neurología (English Edition) 2023;38:635–46. [CrossRef]

- Barrios V, Cosín-Sales J, Bravo M, Escobar C, Gámez JM, Huelmos A, Ortiz Cortés C, Egocheaga I, García-Pinilla JM, Jiménez-Candil J, et al. Telemedicine consultation for the clinical cardiologists in the era of COVID-19: present and future. Consensus document of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2020;73:910–8. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Úbeda EF, Sánchez-Martín P, Torrego-Ellacuría M, Rey-Mejías Á Del, Morales-Contreras MF, Puerta J-L. Flexibility and Bed Margins of the Community of Madrid’s Hospitals during the First Wave of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:3510. [CrossRef]

- Puerta J-L, Torrego-Ellacuría M, Del Rey-Mejías Á, Bienzobas López C. Capacity and organisation of Madrid’s community hospitals during first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. J Healthc Qual Res 2022;37:275–82. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez CG, Chamorro-de-Vega E, Valerio M, Amor-Garcia MA, Tejerina F, Sancho-Gonzalez M, Narrillos-Moraza A, Gimenez-Manzorro A, Manrique-Rodriguez S, Machado M, et al. COVID-19 in hospitalised patients in Spain: a cohort study in Madrid. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021;57:106249. [CrossRef]

- Ramos R, de la Villa S, García-Ramos S, Padilla B, García-Olivares P, Piñero P, Garrido A, Hortal J, Muñoz P, Caamaño E, et al. COVID-19 associated infections in the ICU setting: A retrospective analysis in a tertiary-care hospital. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2023;41:278–83. [CrossRef]

- Tsermoulas G, Zisalis A, Flint G, Belli A. Challenges to Neurosurgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Neurosurg 2020;139:519–25. [CrossRef]

- Taha Z, Alghoul M, Anderson R. Telemedicine and neurosurgery during COVID-19: A global survey of practice patterns. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2021;88:8994.

- Apostolopoulou K, Elmoursi O, deLacy P, Zaki H, McMullan J, Ushewokunze S. The impact of telephone consultations due to COVID-19 on paediatric neurosurgical health services. Child’s Nervous System 2022;38:2133–9. [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. British Journal of Surgery 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kessler RA, Zimering J, Gilligan J, Rothrock R, McNeill I, Shrivastava RK, Caridi J, Bederson J, Hadjipanayis CG. Neurosurgical management of brain and spine tumors in the COVID-19 era: an institutional experience from the epicenter of the pandemic. J Neurooncol 2020;148:211–9. [CrossRef]

- Jean WC, Ironside NT, Sack KD, Felbaum DR, Syed HR. The impact of COVID-19 on neurosurgeons and the strategy for triaging non-emergent operations: a global neurosurgery study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:1229–40. [CrossRef]

- Eichberg DG, Shah AH, Luther EM, et al. Telemedicine in neurosurgery: Lessons learned and a look to the future. Neurosurgery 2020;87:E7–E13. [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. The Lancet 2020;396:27–38.

- Consejeria de Sanidad de la Comunidad de Madrid. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon. Memoria de actividades 2023: Innovación y transformación digital. Madrid: 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).