1. Introduction

Biomineralization refers to the biologically mediated formation of minerals, often involving the precipitation of inorganic compounds through interactions between organisms and their environment [

1]. In terrestrial ecosystems, it plays a crucial role in converting carbon into stable inorganic forms, effectively creating long-term carbon sinks. In this context, biogenic inorganic carbon (BIC) denotes carbon locked in inorganic compounds such as carbonates, oxalates, or silica through biological activity, distinguishing it from abiotically formed inorganic carbon [

2]. Soil inorganic carbon (SIC) typically refers to carbonate minerals within soils, representing a highly stable pool with residence times ranging from millennia to millions of years [

3]. By contrast, soil organic carbon (SOC)—derived from plant and microbial residues—has far shorter residence times, often decades to centuries, making it more vulnerable to release through decomposition, wildfires, or land management changes [

4]. A related concept, phytolith-occluded organic carbon (PhytOC), refers to plant-derived organic carbon physically encapsulated within silica phytoliths, which is highly resistant to decomposition and can persist in soils for millennia [

5]. The most common intracellular biominerals in plants are calcium oxalate crystals, although calcium carbonate and silica are also widespread across lineages [

6]. These intracellular crystals contribute to structural reinforcement, ion homeostasis, and defense against herbivory and pathogens.

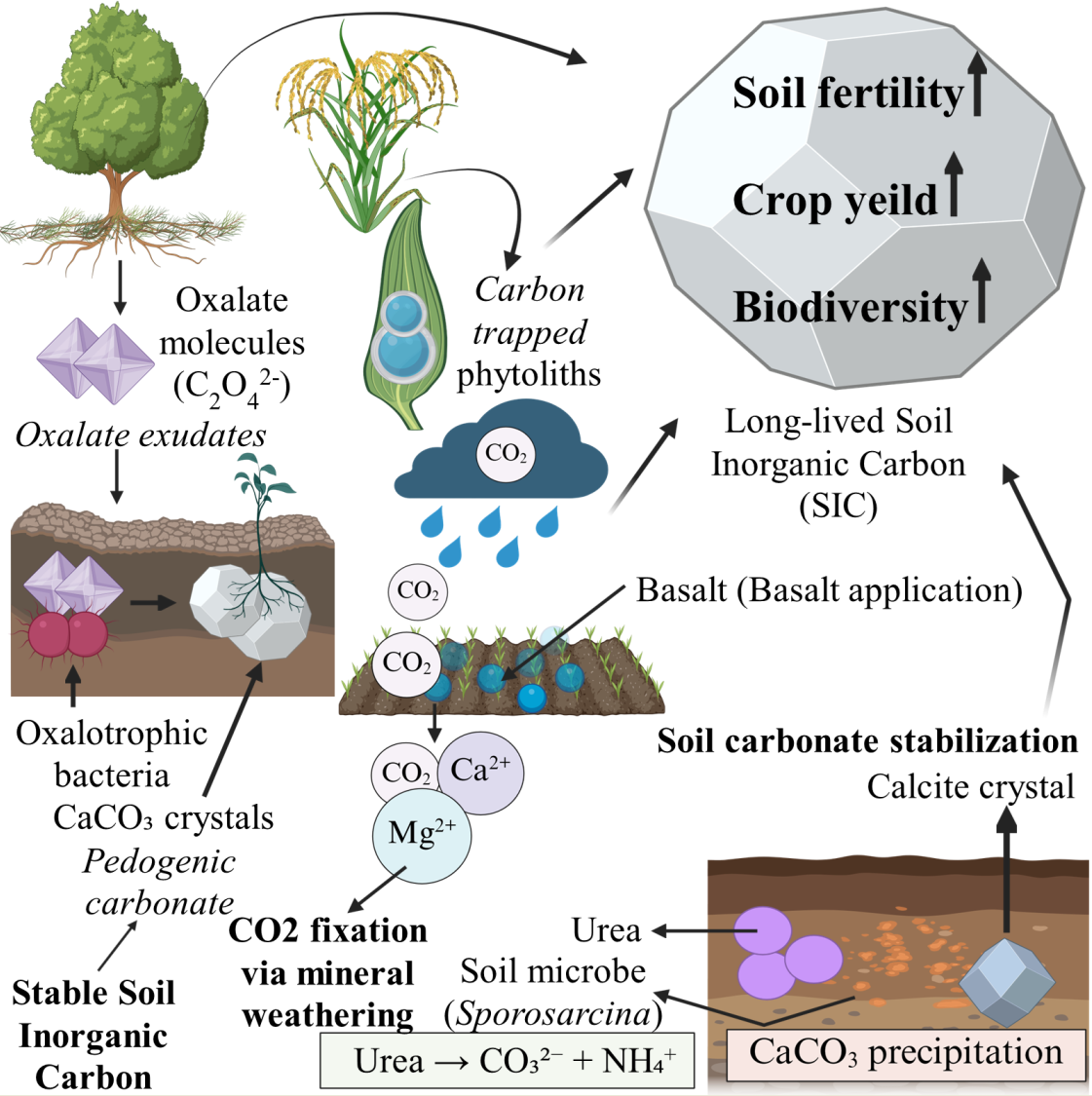

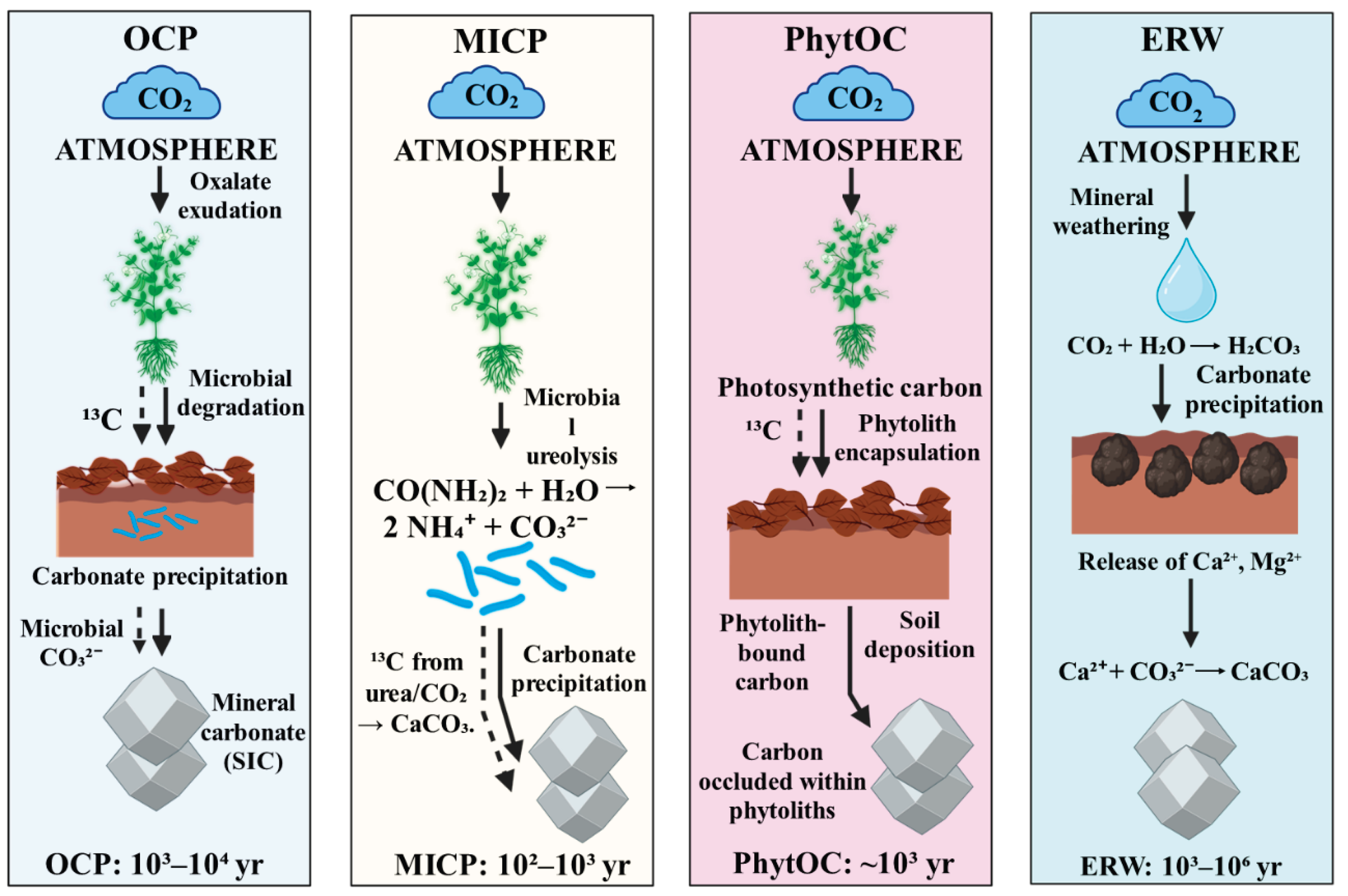

Several key biological and biogeochemical pathways underpin carbon biomineralization:

Oxalate–Carbonate Pathway (OCP): Plants produce calcium oxalate crystals that enter soils via litterfall. Oxalotrophic microorganisms then oxidize oxalate, releasing carbonate and driving calcite precipitation [

7]. In OCP systems, biologically produced calcium oxalate is microbially degraded to alkalinity and carbonate, ultimately precipitating pedogenic calcium carbonate under favorable conditions [

8]. One key enzymatic route involves oxalate decarboxylation, wherein oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase converts oxalyl-CoA to formyl-CoA with release of CO₂, which can subsequently be hydrated to bicarbonate and drive carbonate mineralization [

9]. In wood and litter, brown-rot fungi frequently accumulate calcium oxalate that is subsequently metabolized by oxalotrophic bacteria, sustaining localized alkalinity and carbonate precipitation [

10]. Oxalotrophy is widespread among plant-associated

Burkholderia/Paraburkholderia lineages, providing a microbial conduit between plant oxalate production and carbonate formation in the rhizosphere [

11].

Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation (MICP): Microbial metabolisms such as ureolysis, denitrification, sulfate reduction, or photosynthesis create alkaline conditions or increase bicarbonate availability, leading to carbonate mineral formation [

12]. Extracellular carbonic anhydrases catalyze rapid interconversion of CO₂ and bicarbonate, increasing local carbonate alkalinity and enhancing CaCO₃ nucleation in soils and engineered matrices [

13]. Ureolytic, endospore-forming bacteria such as

Sporosarcina pasteurii can induce calcium carbonate precipitation via urease-driven alkalinization and have been widely tested for biocement and “bioconcrete” applications [

14]. Photosynthetic cyanobacteria and microalgae elevate pH and draw down dissolved inorganic carbon, promoting carbonate precipitation while stabilizing biocrusts and improving infiltration [

15].

Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW): Finely ground silicate minerals (e.g., basalt) are spread onto soils, where plant roots and microbial activity accelerate dissolution, releasing Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ that combine with CO₂ to form stable carbonates or bicarbonates [

16]. For ERW and carbonate-forming pathways, standardized MRV should pair soil inorganic carbon measurements with mineralogical speciation, isotopic partitioning, and, where relevant, process biomarkers (e.g.,

ureC for ureolysis;

oxc/frc for oxalate catabolism) to constrain mechanisms and durability (Hartmann et al., 2013; Syed et al., 2020). To avoid over-generalization, removal rates should be reported as t CO₂ ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ with explicit assumptions on Ca/Mg supply, rainfall, and pH buffering, and should be bracketed by evidence level (lab, field, modeled) [

17]

PhytOC: Organic carbon trapped in silica phytoliths produced by plants, often resistant to microbial degradation [

5]. In croplands, PhytOC provides a distinct, physically protected carbon pool whose accumulation varies among grasses and cereals across climates [

18]. Recent field work from Poland and Estonia indicates that cereal systems can measurably increase PhytOC stocks, highlighting agronomic levers for deployment in temperate regions [

19]. Bamboo forests may achieve comparatively high PhytOC yields per hectare, although reported rates are site-specific and sensitive to species and soil silica supply [

20].

Together, these pathways form a crucial bio-geological bridge that links rapid biological CO₂ fixation to long-term mineral stabilization, thereby addressing the permanence gap between transient biomass storage and durable geological sequestration. Trees and woody plants play a central role in this framework. Through photosynthesis, they capture atmospheric CO₂ and channel it via root exudates and litter decomposition into the rhizosphere, where interactions with microbes, organic acids, and minerals foster carbonate precipitation and accelerated weathering [

21]. Thus, trees act not only as reservoirs of organic carbon but also as bio-catalytic engines for mineralized carbon formation. Woody systems further enhance co-benefits such as soil fertility improvement, biodiversity support, pH buffering, and provision of harvestable products like fruit, timber, and fiber, increasing their appeal for climate mitigation strategies [

22].

Quantitative estimates suggest that woody biomass inputs of oxalates and associated microbial processes could sequester between 0.5–5 t C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ under optimal field conditions [

23]. If scaled to global dryland ecosystems, such biomineralization could offset 10–20% of anthropogenic emissions [

24]. Stable-isotope tracing of pedogenic carbonates (e.g., δ¹³C and radiocarbon) can differentiate newly formed biogenic carbonates from geogenic sources and quantify additionality in OCP/MICP field systems [

25]. The permanence hierarchy underscores that mineralized carbon offers orders of magnitude greater longevity than SOC or biomass. Notably, ecosystems such as those dominated by the iroko tree (

Milicia excelsa) have been termed “true carbon trapping ecosystems,” since they facilitate the transformation of biologically fixed carbon into mineral sinks [

26]. The iroko tree remains the best-documented natural OCP case, where oxalate production and microbial turnover couple to carbonate accumulation at the tree base [

7].

The historical development of this research reveals both ancient and modern dimensions. Carbonate biomineralization traces back ~750 million years, with a major expansion during the Cambrian period that reshaped Earth’s climate [

1]. Early 20th-century observations documented “stones” on iroko tree trunks, while pioneering studies in the 1960s emphasized silica-carbon occlusion in phytoliths. By the 1990s, attention shifted to oxalogenic plants and microbial ecology, culminating in a landmark West African field study that documented the oxalate–carbonate pathway in iroko ecosystems, where oxalates from litter were microbially converted to soil calcite [

27]. Concurrently, geomicrobiologists elucidated multiple microbial carbonate precipitation routes [

28], and geochemists proposed ERW as a viable CO₂ sink. In recent decades, studies of long-lived phytolith carbon and microbial biomineralization confirmed millennial stability. Until peer-reviewed reports appear, anecdotal observations on fig-associated carbonate formation in basaltic soils should be referenced cautiously and framed as hypotheses for replication rather than confirmed rates [

29]. High-profile discoveries, such as CaCO₃ formation in trunks and rhizospheres of fig trees in volcanic soils [

30], further highlight the underappreciated role of woody plants as agents of inorganic carbon sequestration [

26].

This review therefore synthesizes the current state of knowledge on biomineralization processes linked to plants, microbes, soils, and woody tissues [

31]. It excludes purely engineered direct air capture systems unless they explicitly integrate biological mechanisms, such as microbe-enhanced weathering. By emphasizing natural plant–microbe–mineral interactions, this synthesis outlines a path for leveraging biomineralization as a durable, millennia-spanning carbon sink, bridging short-lived biogenic carbon cycles with geological permanence. It identifies key opportunities for research, management, and large-scale application to close the gap between global carbon removal needs and the current limited capacity of conventional carbon dioxide removal strategies.

2. Major Biomineralization Pathways Relevant to Trees and Soils

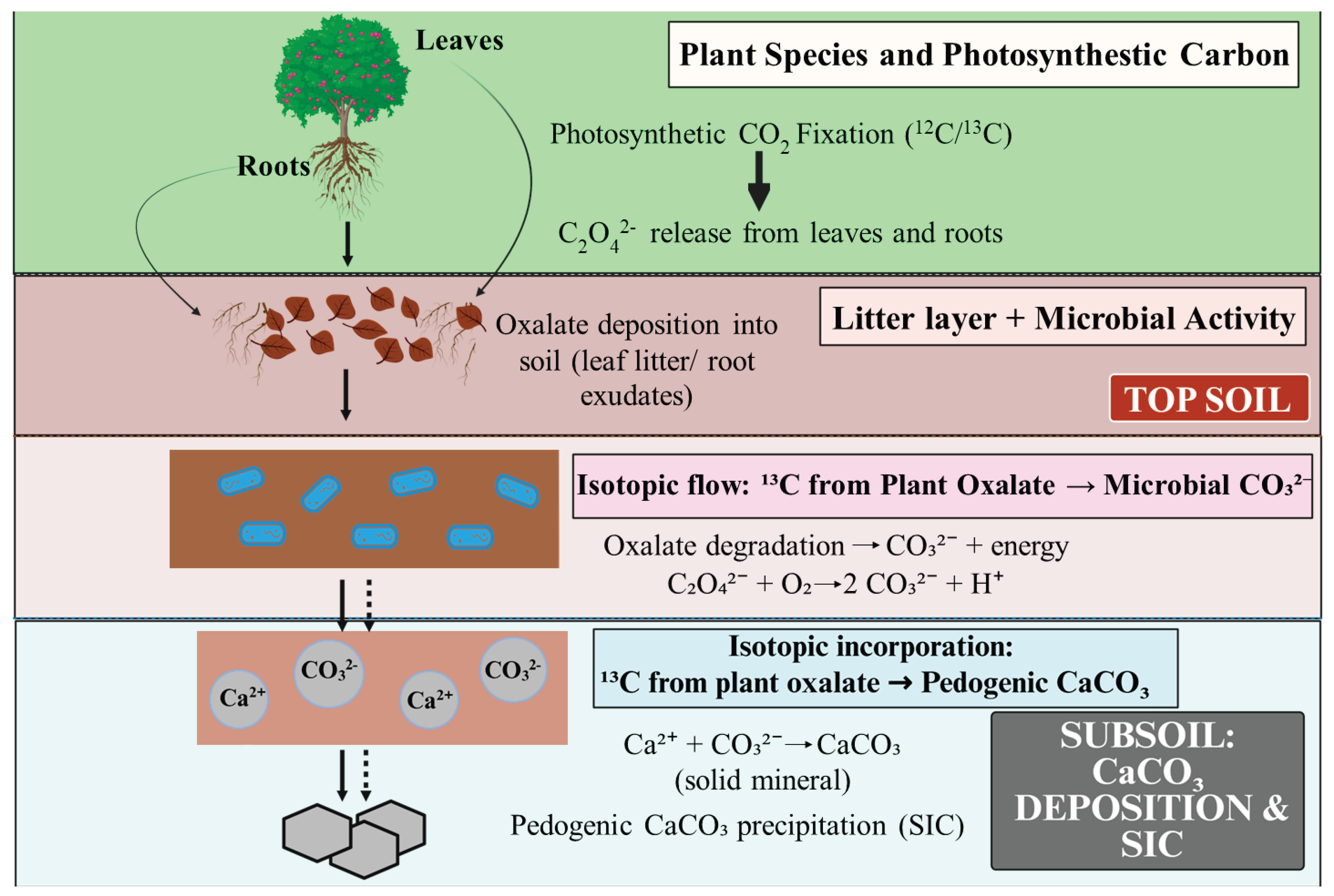

2.1. Oxalate–Carbonate Pathway (OCP)

In the oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP), plants synthesize oxalic acid and precipitate it as calcium oxalate (CaC₂O₄·H₂O, whewellite) within tissues such as leaves, stems, and roots. The most common intracellular biominerals in plants are calcium oxalate crystals, although calcium carbonate and silica are also widespread across lineages [

6]. This crystallization serves multiple physiological roles, including calcium regulation, structural reinforcement, ion homeostasis, and defense against herbivory and pathogens, while simultaneously storing carbon in mineral form inside the plant. Upon senescence and decomposition of plant parts (leaf litter, woody debris, roots), calcium oxalate crystals are released into the soil and litter layers [

2].

The subsequent microbial phase is crucial. Saprophytic fungi and wood-decay organisms liberate oxalate crystals from plant material, while specialized oxalotrophic bacteria metabolize the oxalate through oxidation or decarboxylation reactions. A key enzymatic route involves oxalate decarboxylation, wherein oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase converts oxalyl-CoA to formyl-CoA with release of CO₂, which can subsequently be hydrated to bicarbonate and drive carbonate mineralization [

32]. A simplified microbial process is oxalate decarboxylation:

This generates bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) and formate, consumes protons, and elevates local pH. The resulting alkalinization shifts the carbonate–bicarbonate equilibrium, promoting calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) precipitation in the presence of available Ca²⁺ ions. Sources of calcium include soil solutions, root exudates, weathering of minerals, and basal soil layers. Thus, atmospheric CO₂—fixed by photosynthesis, incorporated into oxalate, and subsequently metabolized—is ultimately mineralized and stored as stable calcite in soils and sometimes within woody tissues (

Figure 1).

This process exemplifies a nature-based solution that bridges biological and geological carbon cycles. The OCP is not a simple plant-to-bacteria conversion but rather a complex, symbiotic interaction. Fungi act as key decomposers, creating the microenvironment necessary for oxalotrophic bacterial metabolism, while bacterial activity depends on fungal-driven pH shifts [

33]. This inter-kingdom dependency ensures efficient mineralization. Notably, in acidic soils where carbonate accumulation is otherwise unexpected, OCP activity can lead to the precipitation of stable calcium carbonate, representing a significant pathway of carbon sequestration. Oxalotrophy is widespread among plant-associated

Burkholderia/Paraburkholderia lineages, providing a microbial conduit between plant oxalate production and carbonate formation in the rhizosphere [

11] (

Figure 2).

Several plant taxa are recognized as OCP-active. Tropical tree species such as

Milicia excelsa (iroko) and various

Ficus species (

F. sycomorus, F. natalensis, F. wakefieldii) produce large calcium oxalate loads. The iroko tree remains the best-documented natural OCP case, where oxalate production and microbial turnover couple to carbonate accumulation at the tree base [

7]. Other oxalogenic plants include members of the Moraceae, Rubiaceae, and certain herbs such as

Oxalis, as well as crop species like spinach and beets. Additional examples include bamboo and some legumes. Successful carbonate precipitation is contingent on both sufficient calcium supply and active microbial communities. Termite activity and decay fungi have been shown to accumulate calcium oxalate in woody debris, which is subsequently metabolized by oxalotrophic bacteria, sustaining localized alkalinity and indirectly enhancing calcite formation in ecosystems such as iroko stands [

10].

Environmental factors strongly modulate OCP efficiency. Soil texture influences drainage and gas exchange, while moisture and microbial ecology determine oxalate turnover. High Ca²⁺ availability, especially from basaltic parent materials, enhances crystal formation. Decomposition rates control the timing and extent of oxalate release: warmer, moist conditions accelerate microbial degradation but also risk leaching if carbonate precipitation does not occur rapidly enough. Observations indicate that OCP efficiency peaks in semi-arid zones receiving 500–800 mm of annual rainfall, where bicarbonate accumulation outpaces dissolution. In such woody systems, the pathway has been estimated to sequester 1–3 t C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ [

34]. In mature OCP systems, soil and decaying wood can reach near-alkaline pH (~8), with visible calcite crystals and concretions forming in soils and sometimes within the tree trunk itself. Stable-isotope tracing of pedogenic carbonates (e.g., δ¹³C and radiocarbon) has been used to differentiate newly formed biogenic carbonates from geogenic sources and quantify additionality in OCP/MICP field systems [

35].

2.2. Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation (MICP) in Rhizosphere & Trunk Microenvironments

MICP is a widespread biogeochemical process in natural environments, driven by diverse microbial metabolisms that increase local pH and carbonate saturation, ultimately leading to the precipitation of carbonate minerals (usually calcite) in soils, biofilms, rhizospheres, or even tree trunks. This process has been extensively documented in soil stabilization, carbon sequestration, and carbonate rock formation, and can be harnessed and enhanced in both engineered and natural systems. In rhizospheres, root exudates provide substrates for microbial activity, creating nucleation sites on root surfaces, soil particles, or trunk crevices where persistent moisture favors precipitation. Nucleation is often controlled by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), which template crystal growth and favor calcite over metastable polymorphs such as vaterite in stable environments [

28].

The dominant metabolic pathways of MICP include:

- a)

Ureolysis – This is the most extensively studied and technologically applied mechanism, mediated by urease-positive bacteria such as Sporosarcina pasteurii (formerly Bacillus pasteurii), as well as Bacillus, Lysinibacillus, Heliobacter, and others. Urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea:

The released ammonia equilibrates to NH₄⁺ and OH⁻, raising pH, while CO₂ hydrates to bicarbonate. In alkaline conditions, Ca²⁺ combines with carbonate (CO₃²⁻) to precipitate CaCO₃. This mechanism can elevate pH to 8–9, driving CaCO₃ supersaturation, and in engineered systems has achieved large-scale carbonate precipitation.

S. pasteurii is particularly effective due to high urease production and endospore resilience in harsh environments. Ureolysis-driven MICP is widely applied in soils, concretes, and calcareous building materials because urea is inexpensive. However, ammonia release may act as a soil fertilizer (a co-benefit) but also raises concerns about N₂O emissions [

36].

- b)

Denitrification – Facultative anaerobes such as Pseudomonas, Paracoccus, and Thauera reduce nitrate under anaerobic conditions:

This reaction consumes protons and generates bicarbonate and hydroxide, increasing alkalinity and enabling carbonate precipitation in the presence of Ca²⁺. Denitrification-driven MICP has been reported in engineered systems and naturally in anoxic soil niches [

37].

- c)

Sulfate Reduction – Sulfate-reducing bacteria such as Desulfovibrio and Desulfobacter convert sulfate to sulfide using organic matter:

This process generates bicarbonate and alkalinity under saturated, anoxic, and organic-rich conditions (e.g., peatlands or flooded soils), favoring carbonate precipitation. However, a trade-off exists due to the potential release of hydrogen sulfide gas, which is toxic [

38].

- d)

Photosynthetic CO₂ Drawdown – Photosynthetic microbes, particularly cyanobacteria (e.g., Synechococcus spp.) and microalgae, deplete dissolved CO₂:

By removing CO₂ and bicarbonate, the equilibrium shifts toward OH⁻ and CO₃²⁻, raising local pH (up to ~10.5) and enabling CaCO₃ precipitation in calcium-rich environments. Many calcifying cyanobacteria, found in soil crusts, moist bark, or epiphytic mats, nucleate CaCO₃ directly on their cells or biofilms. This mechanism has been responsible for large-scale carbonate rock formation throughout geological history and continues to operate in natural and engineered environments [

39].

These functionally distinct pathways demonstrate remarkable redundancy and specialization within the microbial world. Different microbial groups achieve the same endpoint—carbonate mineralization—through diverse strategies, making MICP a resilient process across ecosystems. In rhizospheres, synergies between microbial metabolism and plant exudates enhance carbonate precipitation, with sequestration rates estimated at 0.5–2 t C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹. In tree trunks, epiphytic cyanobacteria drive localized precipitation, as observed in basaltic fig systems, and MICP may complement oxalate–carbonate pathways (OCP) by accelerating carbonate formation in low-oxalate zones. Stable-isotope tracing of pedogenic carbonates (e.g., δ¹³C and radiocarbon) provides a valuable approach to differentiate newly formed biogenic carbonates from geogenic sources and quantify additionality in MICP/OCP field systems [

40].

Overall, MICP represents a versatile, naturally occurring process with significant potential in biogeotechnical engineering, carbon sequestration, and soil stabilization. The choice of microbial pathway depends on environmental conditions, substrate availability, and engineering goals, with ureolysis being the most widely exploited, while denitrification, sulfate reduction, and photosynthetic CO₂ drawdown offer additional routes for targeted applications (Figure 2).

2.3. Phytoliths and Carbon Occlusion (PhytOC)

Phytoliths are microscopic amorphous silica bodies (SiO₂·nH₂O), often referred to as “plant opal,” that precipitate within plant tissues as a result of high silicon uptake from soil monosilicic acid (Si(OH)₄) and transpiration. Grasses and other high-silica plants such as rice, sugarcane, bamboo, horsetails, and cereals can accumulate phytoliths at percent-level concentrations. During phytolith deposition in intra- and extracellular spaces, a fraction of the surrounding organic carbon derived from plant metabolites or cytoplasmic debris becomes physically occluded within the silica matrix, forming phytolith-occluded carbon (PhytOC). The proportion of occluded carbon typically ranges from 0.1% to 6.0% of phytolith mass [

24].

The encapsulated organic carbon is physically protected within the rigid silica matrix, rendering it highly resistant to microbial decomposition [

41]. Unlike other carbon stabilization mechanisms that involve transformation into inorganic forms, PhytOC represents a unique biomineralization pathway in which plants directly stabilize a portion of their organic carbon. This process effectively creates a microscopic, mineralized fortress for organic carbon, leading to its persistence in soils long after plant tissues decompose. Laboratory and field studies have demonstrated that phytoliths can resist dissolution for hundreds to thousands of years, with some sediments preserving phytolith carbon for millions of years. In archaeological soils up to 2,000 years old, over 80% of the residual organic carbon has been detected within phytoliths, highlighting their long-term stability [

42].

PhytOC accumulation varies across ecosystems and management practices. In grasslands, where belowground productivity dominates, phytolith formation plays a major role in total PhytOC accumulation. In agroecosystems, rice (

Oryza sativa) alone contributes significantly, with sequestration rates of 20–70 kg CO₂ per hectare per year depending on genotype and management. Experiments with barley and oat show that silicon fertilization or organic amendments such as compost can increase phytolith abundance and PhytOC content several-fold. Similarly, bamboo forests under sustained management display substantial long-term PhytOC storage [

20]. In mature forests, PhytOC stocks reach 10–30 kg m⁻², with mixed stands exhibiting occlusion rates up to 3% of biomass carbon. In woody systems, erosion and leaching further contribute to subsoil PhytOC transport and storage. Recent field work from Poland and Estonia also indicates that cereal systems can measurably increase PhytOC stocks, highlighting agronomic levers for deployment in temperate regions [

19].

Environmental factors also influence persistence. Neutral soils with low microbial activity enhance long-term stabilization, whereas fire alters phytolith chemistry—often increasing aromatic carbon fractions within the silica but simultaneously releasing some carbon. Recrystallization during burning has been reported to enhance mineral stability. Importantly, PhytOC not only serves as a passive carbon sink but may also synergize with other mineral-associated carbon pools. In particular, parallels exist with the oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP), where biologically produced calcium oxalate is microbially degraded into alkalinity and carbonate, ultimately precipitating as pedogenic calcium carbonate under favorable conditions [

43]. Within such OCP systems, extracellular carbonic anhydrases and oxalotrophic bacteria catalyze CO₂–bicarbonate interconversions, enhancing CaCO₃ nucleation [

44]. By analogy, PhytOC stabilization within silica matrices provides a complementary bio-protective mechanism, and together these pathways highlight how plant biominerals (silica, oxalate, carbonate) contribute to persistent soil carbon pools [

45] (

Figure 2).

Overall, phytolith formation represents an elegant bio-protective mechanism for long-term carbon sequestration. Its stability, persistence, and responsiveness to ecosystem type and management practices make PhytOC particularly relevant in grasslands, forests, and agroecosystems where large biomass production and high silica uptake converge to contribute significantly to soil carbon storage [

46].

2.4. Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW) Synergized with Vegetation

Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW) involves spreading finely crushed silicate rocks (e.g., basalt, olivine, dunite, dolerite) onto soils, agricultural land, or forests to accelerate natural chemical weathering reactions that consume atmospheric CO₂. The increased surface area of the crushed rock speeds up dissolution processes, which are strongly influenced by vegetation and rhizosphere microbes [

47]. Plant roots play a synergistic role by both physically acting on minerals and releasing organic acids, while microbial metabolites further increase the acidity around weathering minerals. In addition, respiration of roots and microbes produces biogenic CO₂, which dissolves in soil water to form carbonic acid (H₂CO₃). Together, these factors dramatically enhance silicate mineral dissolution.

The weathering reactions release divalent cations such as Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺, and also nutrients including K and P, into the soil solution. These cations can subsequently combine with dissolved inorganic carbon (as bicarbonate, HCO₃⁻) to precipitate stable secondary carbonates (e.g., calcite, magnesite) in soils or be transported to rivers and eventually the oceans. Permanence of this captured carbon exceeds 10,000 years in carbonate form, positioning ERW as a scalable bridge to biological carbon removal pathways. Notably, carbonate formation in soils may also couple to biologically mediated oxalate–carbonate pathways (OCP), where plant-derived calcium oxalate crystals are microbially degraded to alkalinity and pedogenic calcium carbonate under favorable conditions [

48]. Oxalotrophic bacteria, including Burkholderia/Paraburkholderia lineages, metabolize oxalate in the rhizosphere, sustaining localized alkalinity and enhancing carbonate precipitation [

49]. Thus, biotic and abiotic processes can jointly increase the durability and magnitude of inorganic carbon storage.

Soil structure and ecosystem type influence ERW efficiency. Porous aggregates facilitate water infiltration, while microbial biofilms on rock particles enhance localized acid secretion. In woody systems, deep roots extend the weathering zone, and exudates such as citrate dissolve silicates 2–5 times faster than abiotic rates. Field trials demonstrate that the presence of plant roots can more than double the weathering rate compared to unplanted controls. Analyses from 2024 studies estimate that ERW combined with vegetation sequesters approximately 0.5–1.5 t CO₂ ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, while global-scale modeling suggests gigaton-scale potential (~1–4 Gt CO₂ yr⁻¹) if basalt were applied to millions of hectares of cropland and forests [

50]. Complementary biological mineralization pathways—including microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) via ureolysis [

14] or extracellular carbonic anhydrase catalyzed CO₂ hydration [

13] may further amplify ERW efficiency under certain soil conditions (

Figure 2).

Beyond carbon removal, ERW provides multiple co-benefits. The released base cations can neutralize soil acidity, raising pH, improving fertility, and reducing nutrient leaching. In acidic soils, basalt dust has been shown to increase soil fertility by 10–20% while simultaneously capturing CO₂. Nutrients such as K and Mg are also supplied, supporting plant growth. Integrating ERW with agroforestry, crop residue management, or regenerative agricultural practices amplifies both climate mitigation and soil health benefits. This integration is increasingly described as a form of “geotherapy,” where a powerful geochemical process couples with dynamic biological systems to achieve durable carbon sequestration and improved ecosystem functioning [

47]. To ensure robustness, standardized monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) frameworks should pair soil inorganic carbon measurements with mineralogical speciation, isotopic partitioning, and relevant microbial biomarkers (e.g., ureC for ureolysis; oxc/frc for oxalate catabolism), allowing clear attribution of carbonate formation pathways and durability [

17].

2.5. Intracellular and Structural Mineralization in Plants (Ca-Oxalate, Ca-Carbonate)

Many plants produce intracellular crystals of calcium oxalate (and less commonly calcium carbonate) as part of their normal physiology. These crystals occur in specialized cells called crystal idioblasts or within vacuoles and may also appear as cell wall deposits. They come in diverse morphologies such as raphides (needle-like) and druses (spherical aggregates). The most common intracellular biominerals in plants are calcium oxalate crystals, although calcium carbonate and silica are also widespread across lineages [

51]. These intracellular crystals contribute to structural reinforcement, ion homeostasis, and defense against herbivory and pathogens [

6]. The formation of calcium oxalate crystals represents the first, rate-limiting step of the oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP), wherein biologically produced calcium oxalate is microbially degraded to alkalinity and carbonate, ultimately precipitating pedogenic calcium carbonate under favorable conditions [

52]. These processes, widespread across the plant kingdom, suggest a vast, evolutionarily ancient potential for carbon mineralization that has been largely untapped for climate mitigation.

In some species, vacuolar Ca-oxalate crystals undergo further intravacuolar calcification, with plants such as figs forming Ca-carbonate layers within these structures. Such biominerals regulate physiology not only by buffering ions but also by releasing CO₂ during stress, thereby aiding photosynthesis. Upon decomposition of plant tissues, these crystals generally dissolve by microbial action, releasing carbon back into the environment. Thus, only a fraction contributes to long-term carbon storage. However, in certain cases, crystal dissolution provides Ca²⁺ fluxes that prime soils for microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP), amplifying carbon sequestration potential by 20–50% in high-biomass trees.

Beyond intracellular crystals, a potentially overlooked reservoir of carbon permanence lies in mineral carbonates formed within woody tissues themselves. Structural mineralization in trunks can create calcite inclusions, such as calcite or calcite-like crusts lining xylem vessels or rays, as documented in Kenyan fig trees where carbonate was found inside wood and on bark [

26]. Similar findings were reported at the 2025 Goldschmidt conference on basaltic figs, highlighting intravacuolar calcification and structural mineralization in trunks. These carbonate deposits may persist locked within wood for decades until complete decomposition, thus contributing an additional layer of carbon stabilization. Collectively, these biomineralization processes—from intracellular Ca-oxalate crystallization and intravacuolar calcification to structural mineralization in woody tissues—integrate plant physiology with soil processes, reinforcing the oxalate–carbonate pathway as a significant mechanism of long-term carbon sequestration. (

Table 1)

3. Microbial Players and Community Ecology

3.1. Oxalotrophs, Ureolytic Bacteria, and Photosynthetic Microbes

Biomineralization is not a passive phenomenon; it is actively driven by diverse microbial groups that employ specialized metabolic processes to induce carbonate precipitation. These microbial communities demonstrate both functional specialization and redundancy, making the system ecologically resilient and scalable. Key contributors include oxalotrophs, ureolytic bacteria, photosynthetic microbes, and associated fungi and saprophytes, each fulfilling distinct ecological and biochemical roles. Notably, the most common intracellular biominerals in plants are calcium oxalate crystals, although calcium carbonate and silica are also widespread across lineages. These crystals contribute to structural reinforcement, ion homeostasis, and defense against herbivory and pathogens [

6], and in oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP) systems, biologically produced calcium oxalate can be microbially degraded to alkalinity and carbonate, ultimately precipitating pedogenic calcium carbonate under favorable conditions [

54].

3.1.1. Oxalotrophs

Oxalotrophic bacteria possess the ability to utilize oxalate as their sole carbon and energy source. Prominent groups include members of the Oxalobacteraceae and Burkholderiales (e.g.,

Cupriavidus,

Ralstonia), with additional representatives from Betaproteobacteria (

Herbaspirillum), Gammaproteobacteria (

Pseudomonas), and Actinobacteria (e.g.,

Streptomyces). Enzymatic pathways vary with environmental context: under anaerobic or low-oxygen rhizosphere conditions, metabolism is mediated by formyl-CoA transferase (

frc) and oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase (

oxc), producing formate and CO₂ and thereby raising alkalinity. In aerobic systems, enzymes such as glyoxylate carboligase (GCL) and hydroxypyruvate reductase dominate oxalate metabolism [

55]. One key enzymatic route involves oxalate decarboxylation, wherein oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase converts oxalyl-CoA to formyl-CoA with release of CO₂, which can subsequently be hydrated to bicarbonate and drive carbonate mineralization [

56].

Oxalotrophs are abundant in soils rich in oxalate from plant litter, especially beneath trees shedding oxalate-laden leaves. They frequently form biofilms on decaying organic matter and interact closely with fungi. For instance, brown-rot fungi generate calcium oxalate during wood decay, which is subsequently degraded by adjacent oxalotrophic bacteria, sustaining localized alkalinity and carbonate precipitation [

57]. Their ecological role includes regulating soil pH, recycling calcium, and contributing to organic carbon turnover. In woody systems, colonization of decaying trunks enhances oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP) efficiency. Oxalotrophy is widespread among plant-associated

Burkholderia/

Paraburkholderia lineages, providing a microbial conduit between plant oxalate production and carbonate formation in the rhizosphere [

11]. Certain strains engage in oxalotrophy exclusively in the context of plant growth promotion, highlighting a mutually beneficial relationship wherein plants provide oxalate as a substrate for microbial partners that, in turn, enhance plant survival.

3.1.2. Ureolytic Bacteria and Sporosarcina pasteurii

Urea-degrading bacteria are central to microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). The most extensively studied is

Sporosarcina pasteurii (formerly

Bacillus pasteurii), a spore-forming soil bacterium characterized by robust urease activity. Urease (encoded by

ureC and accessory genes) hydrolyzes urea into ammonia and CO₂, sharply increasing pH and promoting carbonate precipitation. This process is further accelerated by extracellular carbonic anhydrase, which catalyzes rapid interconversion of CO₂ and bicarbonate, enhancing local carbonate alkalinity and CaCO₃ nucleation in soils and engineered matrices [

58].

The physiological traits of

S. pasteurii, particularly its ability to form resistant endospores, make it highly suited for survival under harsh conditions, including applications in construction (“biocement” and “bioconcrete”) [

36]. Trials in tree soils have demonstrated 20–30% carbonate yield upon rhizosphere inoculation, with nitrate assimilation by roots enhancing compatibility. When combined with urea fertilizers,

S. pasteurii drives localized CaCO₃ precipitation around roots. However, ammonium accumulation requires regulation (e.g., via nitrifying bacteria or uptake by plants) to avoid nitrogen overload or N₂O emissions. Beyond

S. pasteurii, other urease-positive soil bacteria include

Bacillus sphaericus,

Lysinibacillus spp.,

Klebsiella, and certain plant-associated

Rhizobium strains.

3.1.3. Photosynthetic Microbes (Cyanobacteria and Microalgae)

Photosynthetic microbes, particularly cyanobacteria (e.g.,

Microcoleus,

Calothrix,

Nostoc,

Synechococcus) and microalgae, significantly influence carbonate precipitation by reducing dissolved CO₂ and bicarbonate through photosynthesis [

39]. The light-driven depletion of inorganic carbon raises ambient pH and shifts carbonate equilibria toward CO₃²⁻, enabling CaCO₃ precipitation in the presence of Ca²⁺.

Ecologically, cyanobacteria and green algae form biocrusts on soil surfaces, inhabit rock crevices, colonize wet bark, and thrive epiphytically on trunks in moist niches. They contribute substantially (10–20%) to trunk-associated mineralization processes. Their extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and biofilm matrices act as nucleation sites, facilitating calcite deposition. On larger scales, calcifying cyanobacteria are well known as architects of stromatolites and calcareous deposits in aquatic systems, while in terrestrial desert crusts and moist soils, microalgal–cyanobacterial mats drive localized carbonate accumulation. Photosynthetic cyanobacteria and microalgae therefore both stabilize biocrusts and improve water infiltration, while promoting carbonate precipitation [

59]. These organisms largely alter their immediate microenvironment rather than directly metabolizing calcium, making them important agents of passive yet effective biomineralization.

3.1.4. Functional Redundancy and Specialization

The coexistence of oxalotrophs, ureolytic bacteria, and photosynthetic microbes demonstrates both redundancy and specialization within biomineralizing communities. Functional redundancy ensures resilience—if one pathway is inhibited, others may still drive mineralization. At the same time, strong specialization underpins ecological roles:

S. pasteurii’s endospore-forming capacity uniquely suits bioconcrete applications [

58], oxalotrophs are selectively recruited by plant root exudates [

60], and cyanobacteria contribute significantly to biocrust restoration [

51]. This interplay of generalist and specialist microbes is therefore central to the efficiency, resilience, and scalability of natural and engineered biomineralization systems.

3.2. Fungi and Community Ecology

Fungi contribute to biomineralization in multiple ways and are not merely passive partners in the process but active and indispensable players. Saprotrophic fungi decompose organic matter and often excrete oxalic acid to mobilize nutrients and metals. For example, many wood-decay fungi (especially brown-rot species like

Serpula lacrymans) produce copious oxalate during lignocellulose breakdown, generating calcium oxalate crystals on wood surfaces or in the surrounding litter, effectively storing calcium [

61]. These intracellular crystals, especially calcium oxalate but also calcium carbonate and silica across lineages, contribute to structural reinforcement, ion homeostasis, and defense against herbivory and pathogens [

62]. Other fungi can decompose these crystals: some produce oxalate decarboxylase or oxidase to utilize oxalate carbon.

Mycorrhizal fungi (both ecto- and arbuscular types) also influence soil carbonate; by altering root exudates and through mineral weathering (with hyphae physically penetrating minerals), they can indirectly affect local Ca²⁺ and bicarbonate concentrations. Some mycorrhizal and plant pathogenic fungi are known to precipitate calcium carbonate on hyphae or spores under high-calcium conditions. Thus, fungi often create the oxalate substrates for the oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP) and can either sequester or release carbonate through their metabolic activities [

63].

Fungi, particularly brown-rot fungi, are prolific producers of oxalic acid [

57]. This acid can be used to chelate metals for nutrient acquisition or, in the case of the OCP, as a precursor for carbonate formation [

64]. In wood and litter, brown-rot fungi frequently accumulate calcium oxalate that is subsequently metabolized by oxalotrophic bacteria, sustaining localized alkalinity and carbonate precipitation [

65]. One key enzymatic route involves oxalate decarboxylation, wherein oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase converts oxalyl-CoA to formyl-CoA with release of CO₂, which can subsequently be hydrated to bicarbonate and drive carbonate mineralization [

56]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that while bacteria are primarily responsible for the local pH shift that induces carbonate precipitation, their oxalotrophic activity requires the presence of fungi to be effective [

66]. This indicates a more profound, inter-kingdom dependency than previously understood, where fungi prime the system for bacterial action. For instance, fungi such as

Aspergillus produce oxalates during decomposition, feeding oxalotrophs, while saprophytes enhance OCP by breaking lignocellulose and releasing substrates.

Oxalotrophy is widespread among plant-associated

Burkholderia/Paraburkholderia lineages, providing a microbial conduit between plant oxalate production and carbonate formation in the rhizosphere [

67]. Extracellular carbonic anhydrases further catalyze the rapid interconversion of CO₂ and bicarbonate, increasing local carbonate alkalinity and enhancing CaCO₃ nucleation in soils and engineered matrices [

68]. The iroko tree (

Milicia excelsa) remains the best-documented natural OCP case, where oxalate production and microbial turnover couple to carbonate accumulation at the tree base [

64]. Until peer-reviewed reports appear, anecdotal observations on fig-associated carbonate formation in basaltic soils should be referenced cautiously and framed as hypotheses for replication rather than confirmed rates [

7].

The role of fungi in soil carbon dynamics extends beyond metabolism. Fungal biomass is generally more resistant to decomposition than bacterial biomass, and the remains of dead fungi (necromass) are considered a main component of stable soil organic carbon [

66]. Fungi also secrete compounds that bind soil particles together, forming stable aggregates that physically protect carbon from decomposition. This process is increasingly referred to as the “microbial carbon pump,” whereby microorganisms transform labile carbon into more stable, recalcitrant forms [

31]. Consequently, soils with a higher fungal-to-bacterial ratio tend to show enhanced carbon sequestration [

21]. In croplands, phytolith-occluded carbon (PhytOC) provides a distinct, physically protected carbon pool whose accumulation varies among grasses and cereals across climates [

5]. Recent field work from Poland and Estonia indicates that cereal systems can measurably increase PhytOC stocks, highlighting agronomic levers for deployment in temperate regions [

19]. Bamboo forests may achieve comparatively high PhytOC yields per hectare, although reported rates are site-specific and sensitive to species and soil silica supply [

69]. This direct link between microbial community structure and long-term carbon permanence underscores that biomineralization is not just a chemical process but also an ecologically managed one, with land management practices directly influencing the microbial communities driving carbon stabilization.

3.2.1. Microbial Community Assembly, pH Niches, Nutrient Feedbacks, and Resilience

The micro-scale geochemical gradients generated by oxalate oxidation or ureolysis create distinct niches. Zones of active oxalate consumption become alkaline and calcium-rich, selecting for alkaliphilic bacteria and suppressing acid-tolerant ones. In such “OCP zones,” microbial community composition can converge on consortia of oxalate degraders and calcite nucleators. Assembly follows niche partitioning, with acid-tolerant fungi dominating in low-pH microenvironments and alkaliphilic bacteria prevailing under high-pH conditions. Nutrient feedbacks further reinforce these interactions: ureolytic microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) releases NH₄⁺, which can fertilize plants or be nitrified (potentially producing N₂O). Conversely, denitrification-driven precipitation consumes NO₃⁻, altering nitrogen availability, while sulfate reduction taps into soil sulfur pools. Over time, these processes influence soil nutrient cycles. For example, increasing soil pH through calcification can raise phosphate availability (by releasing it from iron oxides) but can also precipitate micronutrient cations [

2].

Resilience of these communities is tied to both environmental stability and community diversity. Sustained mineralization requires continuous substrate supply (e.g., plant litter) and appropriate conditions (pH, moisture). Mixed communities buffer pH shifts and sustain sequestration over time. However, in disturbed or managed systems, engineering or disturbance may disrupt microbial networks, highlighting the importance of understanding ecological assembly when planning biomineralization interventions. Stable-isotope tracing of pedogenic carbonates (e.g., δ¹³C and radiocarbon) can differentiate newly formed biogenic carbonates from geogenic sources and quantify additionality in OCP/MICP field systems (Manning & Renforth, 2013; Bayat et al., 2023). For enhanced rock weathering and carbonate-forming pathways, standardized MRV should pair soil inorganic carbon measurements with mineralogical speciation, isotopic partitioning, and, where relevant, process biomarkers (e.g.,

ureC for ureolysis;

oxc/frc for oxalate catabolism) to constrain mechanisms and durability [

47]. To avoid over-generalization, removal rates should be reported as t CO₂ ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ with explicit assumptions on Ca/Mg supply, rainfall, and pH buffering, and should be bracketed by evidence level (lab, field, modeled).

4. Mechanistic Geochemistry: Nucleation, Polymorphs, and Permanence

4.1. Geochemical Pathways from CO2 → Organic C → Oxalate → Carbonate

The geochemical pathway from atmospheric CO₂ to stable mineral carbonates involves a series of interlinked reactions, often facilitated by biological catalysts (

Figure 1). The process begins with gaseous CO₂ dissolving in aqueous solutions such as soil water, forming carbonic acid (H₂CO₃), which then dissociates into bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) and carbonate ions (CO₃²⁻).¹ In biomineralization contexts, this can occur either directly through CO₂ consumption by photosynthetic microbes³³ or indirectly via the breakdown of organic matter.⁹

The most common intracellular biominerals in plants are calcium oxalate crystals, although calcium carbonate and silica are also widespread across lineages [

8]. These intracellular crystals contribute to structural reinforcement, ion homeostasis, and defense against herbivory and pathogens.

In the Oxalate–Carbonate Pathway (OCP), plants initially capture atmospheric CO₂ through photosynthesis, a portion of which is converted biochemically into oxalic acid (H₂C₂O₄) by plants or fungi. Within plants, oxalic acid readily precipitates with Ca²⁺ to form calcium oxalate (CaC₂O₄·H₂O, whewellite).⁹ Upon plant decay, microbial oxalotrophy oxidizes CaC₂O₄ to bicarbonate and formate, consuming protons and leading to local alkalinization. The simplified net microbial reaction is:

One key enzymatic route involves oxalate decarboxylation, wherein oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase converts oxalyl-CoA to formyl-CoA with release of CO₂, which can subsequently be hydrated to bicarbonate and drive carbonate mineralization [

70]. In wood and litter, brown-rot fungi frequently accumulate calcium oxalate that is subsequently metabolized by oxalotrophic bacteria, sustaining localized alkalinity and carbonate precipitation [

33]. Oxalotrophy is widespread among plant-associated Burkholderia/Paraburkholderia lineages, providing a microbial conduit between plant oxalate production and carbonate formation in the rhizosphere [

71].

This microbial degradation of oxalate thus liberates both calcium (Ca²⁺) and carbon species, which subsequently precipitate as calcium carbonate (CaCO₃).²⁰ As soil pH rises (often to ~8 or above), dissolved carbonate species increase and calcite precipitation is favored. The key controlling factors include pH, Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ availability, and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC). In alkaline conditions, most DIC exists as CO₃²⁻, favoring CaCO₃ precipitation; in acidic soils, CaCO₃ tends to dissolve back into Ca²⁺ and CO₂.

Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW) also contributes, wherein biogenic CO₂ from root and microbial respiration forms carbonic acid, which acidifies the soil solution and accelerates the dissolution of reactive silicate minerals.⁸ This releases divalent cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺) that combine with dissolved carbon species to precipitate stable carbonate minerals [

72].

4.2. Mineral Phases, Transformation Pathways, and Stability

Carbonate minerals occur as different polymorphs with distinct stabilities. Calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) precipitates in three main polymorphic forms: calcite, aragonite, and vaterite.²² Calcite (trigonal CaCO₃) is the most thermodynamically stable under Earth surface conditions and dominates pedogenic carbonates. It is therefore the most durable, with residence times ranging from 10³–10⁵ years in soils⁶ and potentially extending to millions of years in stable geologic settings. Classic soil carbonates have radiocarbon ages of 10³–10⁵ years under arid/semiarid conditions, while even in acidic, leached soils, soil inorganic carbon (SIC) may persist over 10⁴–10⁵ years, far exceeding organic carbon turnover.

Aragonite (orthorhombic CaCO₃) and vaterite (hexagonal CaCO₃) are metastable phases.⁵¹ Aragonite is more stable than vaterite but transforms to calcite over geological timescales of 10–100 million years.⁵² Vaterite is the least stable and readily transforms into calcite or aragonite via dissolution–reprecipitation processes such as Ostwald ripening, especially under humid conditions (weeks to months).⁵¹ Microbial activity and organic impurities may transiently stabilize metastable polymorphs, but the long-term goal in carbon sequestration systems is to favor calcite precipitation, given its superior permanence. Biological carbonates, including coral skeletons or microbialites, commonly form aragonite or vaterite before later recrystallization to calcite.

Calcium oxalate (whewellite, CaC₂O₄·H₂O) itself is quite insoluble (solubility ~0.0028 g/100 mL in water) and may convert to weddellite (CaC₂O₄·2H₂O) under some conditions, though both are similar in stability. While whewellite provides temporary carbon protection, its stability is ultimately limited by microbial enzymatic degradation or extreme pH shifts, making it less permanent than CaCO₃ [

73].

Phytoliths (amorphous silica) also sequester carbon by physical occlusion; their solubility is extremely low at near-neutral pH, allowing persistence over >10³ years in soils unless dissolved by strong alkali or biological weathering [

74]. In croplands, phytolith-occluded carbon (PhytOC) provides a distinct, physically protected carbon pool whose accumulation varies among grasses and cereals across climates. Recent field work from Poland and Estonia indicates that cereal systems can measurably increase PhytOC stocks, highlighting agronomic levers for deployment in temperate regions [

19]. Bamboo forests may achieve comparatively high PhytOC yields per hectare, although reported rates are site-specific and sensitive to species and soil silica supply [

20].

4.3. Inference and Permanence

The permanence of mineralized carbon is fundamentally linked to the thermodynamic stability of the precipitated phases. In soil and woody matrices, calcite is particularly long-lived due to its low solubility and stability under alkaline conditions. Encapsulation within woody tissues can further extend permanence, reducing dissolution rates by ~50% and enabling sequestration on timescales exceeding 10,000 years. In living roots or wood, CaCO₃ may remain stored for decades, and burial in anoxic sediments or conversion to biochar may render carbonate effectively permanent (centuries to millennia). In alkaline woody soils, Mg/Ca ratios <1 strongly favor calcite precipitation and longevity, thereby amplifying sequestration efficiency by minimizing carbon re-emission.

Stable-isotope tracing of pedogenic carbonates (e.g., δ¹³C and radiocarbon) can differentiate newly formed biogenic carbonates from geogenic sources and quantify additionality in OCP/MICP field systems (Manning & Renforth, 2013; Bayat et al., 2023). For enhanced rock weathering and carbonate-forming pathways, standardized MRV should pair soil inorganic carbon measurements with mineralogical speciation, isotopic partitioning, and, where relevant, process biomarkers (e.g., ureC for ureolysis; oxc/frc for oxalate catabolism) to constrain mechanisms and durability. To avoid over-generalization, removal rates should be reported as t CO₂ ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ with explicit assumptions on Ca/Mg supply, rainfall, and pH buffering, and should be bracketed by evidence level (lab, field, modeled) [

17].

5. Empirical Evidence — Case Studies and Field Reports

5.1. Classic Ecosystems: Iroko (Ivory Coast) and Documented OCP Sites; Isotopic and Mineralogical Evidence

The best-documented case of the oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP) comes from the West African iroko tree (

Milicia excelsa), historically observed since the early 20th century for its association with calcite “stones” on its trunks [

7]. Researchers in Ivory Coast found that iroko forests produce a large flux of calcium through leaf litter and termite-rotted wood. Dead leaves of iroko, rich in CaC₂O₄ crystals [

6], accumulate on the forest floor. Wood-decaying termites consume the trunk, releasing CaOx, which is then oxidized by soil bacteria and oxalotrophic microorganisms [

11]. The net effect is a conspicuous layer of calcite in the soil at the tree’s base, even though the surrounding oxisol is highly leached of carbonates. Geochemical modeling and isotopic analyses (δ¹³C of carbonate) confirmed that much of the soil CaCO₃ originated from the plant’s oxalate, with the isotopic “fingerprint” distinguishing it from ancient geological carbon and directly reflecting plant respiration and microbial activity [

25]. Termites play a key role by digesting wood and producing fecal pellets rich in calcium carbonate, further contributing to soil carbonate. Mineralogical evidence includes calcite nodules in soils, and field measurements suggested that each mature iroko can sequester on the order of one ton of CaCO₃ (≈0.6 t CO₂) in its lifetime. At the ecosystem level, iroko sites show sequestration rates of 2–4 t C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ via OCP. This “carbon trapping” mechanism converts a significant fraction of the tree’s photosynthate into stable inorganic carbon, making it a true carbon sink so long as the calcium source is not from pre-existing carbonate rocks. Similar OCP activity has been reported under other tropical species (e.g.,

Manilkara bidentata), but iroko remains the canonical example.

5.2. Recent Observations: Fig Trees in Basaltic Soils

A high-profile recent study in Kenya, presented at the Goldschmidt 2025 conference, reported that native fig trees growing on volcanic basalt actively convert atmospheric CO₂ into trunk and soil carbonates [

75]. In three

Ficus species, notably

F. wakefieldii, calcium carbonate was detected both on the exterior of trunks and deep within wood tissues, as revealed by synchrotron X-ray microscopy. Soil around the trees was strongly alkalinized and enriched in calcite. The pathway was clearly OCP-based: leaves and roots of the figs produce Ca-oxalate, which upon decay is metabolized by oxalotrophic bacteria and fungi to precipitate CaCO₃ [

10].

Ficus wakefieldii was found to be especially effective, with reported sequestration rates of 1–2 t C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ and long-term storage in calcified wood. This expands the known carbon sink beyond the soil to include woody biomass itself, suggesting a higher total sequestration potential than previously assumed. Remarkably, these fig trees are fruit-bearing, suggesting that food crops could simultaneously provide carbon storage, soil alkalinization (unlocking key nutrients), and food security. Researchers estimated that each tree could fix on the order of tonnes of CO₂ as calcium carbonate over decades, raising hopes for agroforestry applications and positioning oxalogenic trees as a potential climate mitigation tool. However, until peer-reviewed reports appear, these findings should be referenced cautiously and framed as hypotheses for replication rather than confirmed rates [

76].

5.3. Agricultural Systems: PhytOC in Crops and Bamboo

Biomineralization pathways are not limited to natural forest ecosystems. The phytolith-occluded carbon (PhytOC) pathway, in particular, holds significant potential in agricultural systems [

24]. In annual crops like rice, wheat, barley, and maize, a fraction of biomass silica is returned to soil each harvest. Measurements show that intensively managed rice paddies can accumulate tens of kg CO₂ per hectare per year as phytolith carbon, with literature values ranging from ~16 to >100 kg CO₂·ha⁻¹·yr⁻¹ depending on variety and conditions. One meta-analysis estimated rice cropping contributes ~0.02–0.07 t CO₂·ha⁻¹·yr⁻¹ to stable carbon pools via PhytOC. Recent field work from Poland and Estonia indicates that cereal systems can measurably increase PhytOC stocks, with 3–5 fold enhancement achievable through foliar silicon application and compost fertilization [

77]. Cover crops and silicon fertilization can further boost these numbers: for example, soluble Si fertilizer applied to wheat or oat increased phytolith content by several mg g⁻¹ and raised the implied carbon sink several-fold.

Perennial grasses and bamboos can build up PhytOC over longer timescales. Bamboo plantations have been shown to yield 0.5–1 t PhytOC ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, with intensive management (heavy mulching, fertilization) increasing soil phytolith carbon by >200 Mg C·ha⁻¹ in 20 years, ~85% of which derived from leaf litter used as mulch [

20]. Management practices strongly influence sequestration: residue retention can boost rates by ~30%, while fire and residue burning have more complex effects. For instance, open-fire burning of pine forest residue led to higher carbon concentration and lower solubility of residual phytoliths, suggesting that some phytolith carbon becomes more recalcitrant after combustion. In temperate pastures, native grasses also contribute phytolith carbon to soils over decades, though usually at rates lower than intensively managed crop systems. Overall, agricultural lands represent a non-negligible sink for long-term carbon via PhytOC, especially when optimized with high-silicon crops, bamboo systems, and appropriate residue management. (

Table 2)

5.4. Experimental MICP Trials in Soils and in Planta (Greenhouse and Field), Dolerite/Basalt Amendments Supplying Divalent Cations

Experimental trials have validated the practical, co-beneficial applications of microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). Laboratory studies have shown that MICP treatments can significantly improve the strength of root-soil composites, with one study documenting a 32.6% increase in strength and a 49.2% increase in cohesive force with a 1.5% root content [

85]. Importantly, the MICP reaction showed no negative effects on vegetation growth, demonstrating its strong engineering application value for purposes such as slope reinforcement and soil erosion control.

Field and greenhouse trials have tested MICP in soils, often motivated by erosion control or concrete repair. In agriculture-related contexts, experiments involve adding ureolytic bacteria (often

Sporosarcina pasteurii) with urea and a calcium source (CaCl₂ or crushed limestone) to topsoil [

14]. Results consistently show precipitation of calcite within soil pores, reducing permeability and increasing soil strength. For example, adding basalt rock dust (dolerite fines) as the Ca source led to more inorganic carbon precipitation than using CaCl₂, despite also emitting more CO₂ initially (the net balance favored dolerite, which provides weatherable Ca) [

80]. Such “green MICP” field tests highlight the trade-off: rock amendments store more carbon long-term but require careful management of transient CO₂ efflux.

Some studies have attempted in planta approaches, injecting MICP solutions into tree hollows or trunk bases to promote internal calcification; these are still experimental. More commonly, enhanced rock weathering (ERW) trials add silicate dust to fields with concurrent MICP (e.g., adding urea). In one pilot, a plot amended with basalt and urea showed a net removal of soil CO₂ over a growing season, whereas a CaCl₂-treated plot needed more optimization. Although quantitative results vary, a key insight is that providing magnesium and calcium via reactive rocks can enhance microbial calcification with a lower net carbon cost. Similarly, ERW trials, such as a four-year field study in the US Corn Belt, have demonstrated that the annual application of crushed basalt can increase maize and soybean yields by 12% to 16%, while simultaneously resulting in significant carbon removal [

86]. Greenhouse trials with basalt amendments show 0.8 t CO₂ ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, enhanced by tree roots.

These findings underscore the importance of standardized monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) protocols for OCP, PhytOC, MICP, and ERW systems, pairing soil inorganic carbon measurements with mineralogical speciation, isotopic partitioning, and molecular biomarkers (e.g.,

ureC for ureolysis;

oxc/frc for oxalate catabolism) to constrain mechanisms and durability [

54]. (

Table 3)

6. Methods and Measurement

6.1. Mineralogical & Microstructural Tools

Accurately identifying and characterizing biominerals requires a multi-scale suite of analytical techniques, as no single tool is sufficient to fully characterize the mineral phases, their chemical composition, and their relationship to biological components.

Together, these approaches move beyond identifying “who is there” to understanding “what they are doing” and establishing causal links to biomineralization processes.

MRV Frameworks for Permanence, Leakage, and Additionality: Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) is critical for carbon accounting, ensuring credibility of biomineralization projects.

Long-term Monitoring: Repeated soil and plant sampling across years to track inorganic carbon stocks (calcite, phytolith C) [

108].

Flux Measurements: CO₂ fluxes measured via closed chambers or eddy-covariance; distinguishing inorganic vs. organic fluxes may require isotopic tracing or specialized chambers targeting HCO₃⁻ [

109].

Baseline Controls & Field Trials: Paired plots and randomized designs establish baselines and capture variability, proving

additionality (that sequestration would not occur without intervention) [

35].

Permanence Trials: Soil cores incubated under altered pH/moisture test stability of newly formed carbonates. Addressing metastable mineral phases is key [

110].

Leakage and Trade-offs: Assessment of unintended effects (e.g., N₂O emissions from urea, nutrient leaching, rock mining/transport for ERW) [

16].

Modeling: Process-based soil carbon models (including inorganic pools) extrapolate findings across scales and time [

111].

Certification Standards: Few carbon-credit protocols explicitly recognize SIC. New standards—similar to those for biochar or SOC—are urgently needed. High MRV costs remain a barrier, but digital MRV (dMRV) solutions may reduce expenses via automation [

35].

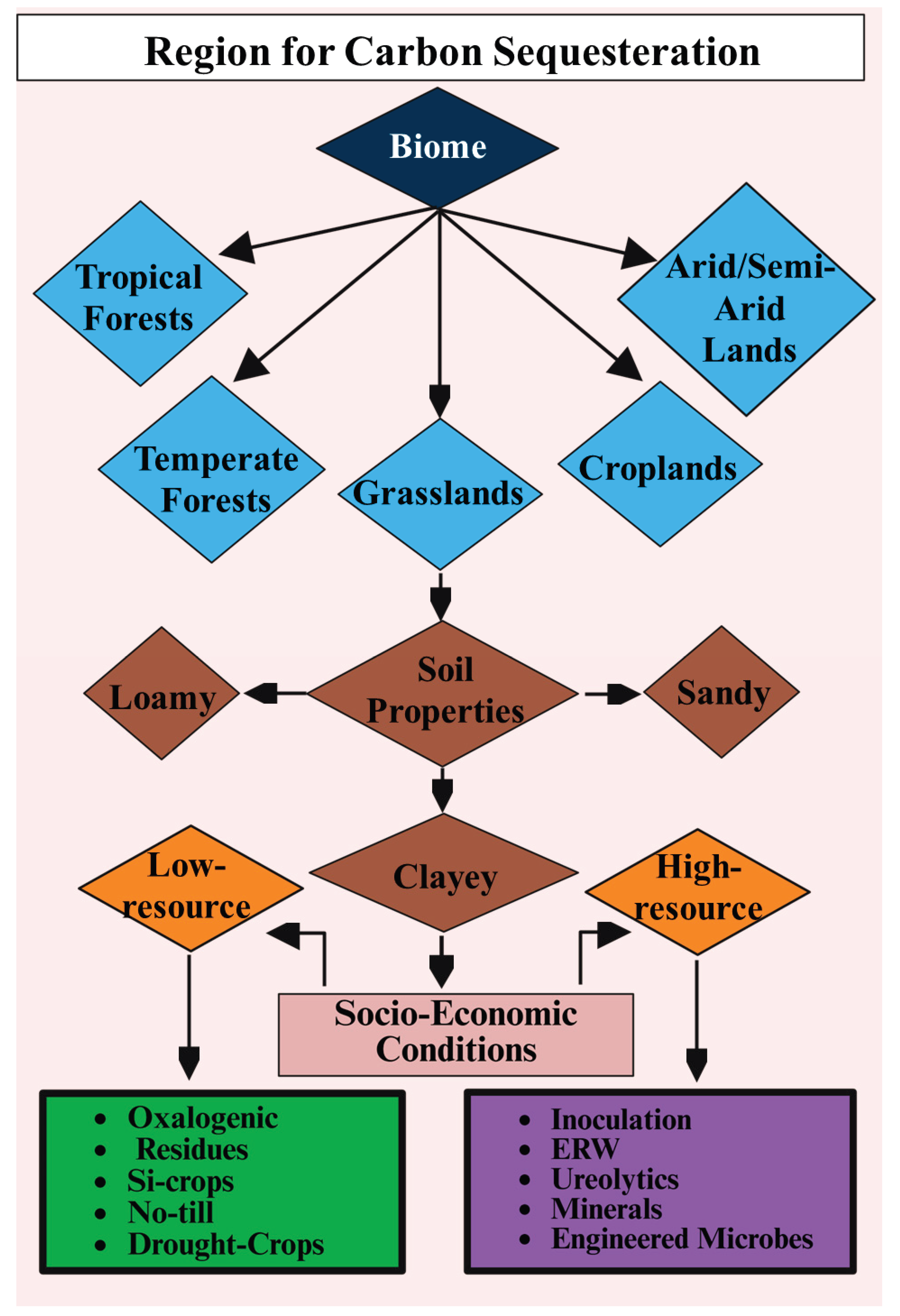

7. Engineering and Management Pathways

7.1. Low-Intervention Strategies: Selecting and Restoring Oxalogenic Tree Species, Agroforestry Integration, Residue and Fire Management to Maximize OCP and PhytOC

Leveraging biomineralization does not always require high-tech interventions. Low-intervention strategies, rooted in ecological management, provide a scalable pathway for enhancing carbon mineralization. Planting or preserving oxalogenic tree species such as iroko, certain oaks, and fig trees (Ficus spp.) enhances the oxalate–carbonate pathway (OCP), offering long-term inorganic carbon sequestration beyond biomass storage. The food value of fig trees creates an additional agroforestry co-benefit. Agroforestry systems that intermix trees with crops and/or livestock significantly enhance soil organic carbon, improve nutrient cycling, reduce erosion, and increase biodiversity, while also fostering favorable microbial environments that strengthen both OCP and PhytOC pathway [

2]. Encouraging highly silicified grasses and bamboos (e.g., vetiver grass, fast-growing bamboo) further enhances PhytOC sequestration.

Management practices play a decisive role. Retaining crop residues and leaf litter instead of burning ensures that oxalates and phytoliths return to the soil for long-term sequestration. Heavy mulching, as demonstrated in bamboo systems, amplifies carbon storage. Controlled burning is controversial: while carbonization may increase phytolith recalcitrance and produce carbonated ash isotopically linked to plant material, it also releases CO₂ and may volatilize nutrients. Overall, low-disturbance regimes such as no-till farming and organic amendments favor inorganic carbon accumulation, whereas repeated burning or deep plowing dissipates it. Reforestation of degraded soils with local oxalogenic species offers an additional pathway for passive carbon capture (

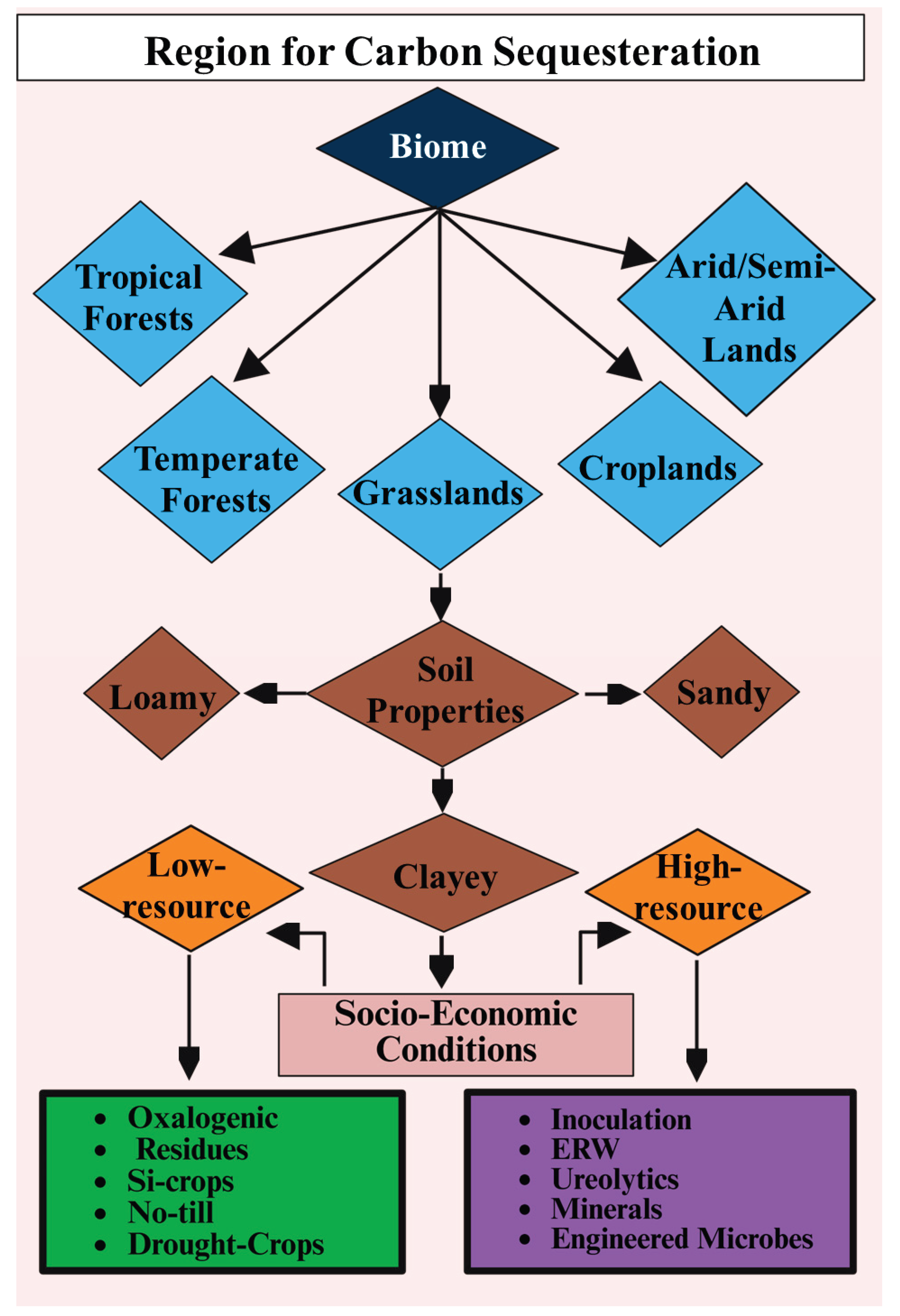

Figure 3).

7.2. Active Microbial Augmentation: Inoculation with Oxalotrophs/Ureolytic Strains and Biosafety Considerations

A more active approach to biomineralization involves microbial inoculation. Bioaugmentation introduces beneficial microbes to accelerate carbonate precipitation. For OCP, soils may be inoculated with efficient oxalate-degrading bacteria such as Cupriavidus oxalaticus, which promote calcite formation from existing oxalate pools. For microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP), ureolytic bacteria such as Sporosarcina pasteurii can be delivered with urea and calcium sources to cement calcium carbonate in soils. Early greenhouse trials show that ureolytic consortia can double soil carbonate production under controlled conditions, though questions of scalability and persistence remain.

Microbial inoculants can also stimulate plant growth and improve nutrient cycling, highlighting the potential to “choreograph” soil metabolic activity toward carbon storage. However, this approach raises ethical, ecological, and regulatory concerns. Strict biosafety oversight is critical to prevent risks associated with non-native or genetically modified strains. Strains should be non-pathogenic, environmentally contained, and preferably native or well-characterized. Potential delivery routes include seed coatings or soil drenches, though deployment would likely be restricted to degraded or remediation sites rather than pristine ecosystems to avoid ecological imbalance. Genetic engineering to enhance urease output or carbonate precipitation efficiency remains theoretical and subject to rigorous governance frameworks.

7.3. Mineral Amendments and Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW) Integration

Mineral amendments provide cations and alkalinity that support biomineralization. Enhanced rock weathering (ERW), in particular, involves spreading finely ground basalt or dolerite, typically at 1–10 tons per hectare, supplying Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and other weatherable minerals over years. Basalt is favorable due to its abundance of divalent cations essential for carbonation reactions [

34]. The synergy between mineral amendments and vegetation—where plant roots and microbes accelerate mineral dissolution—transforms ERW from a purely geochemical reaction into a coupled nature-based climate solution.

Experimental plots combining fine dolerite with urea or compost have demonstrated enhanced carbonate yield. Limestone (CaCO₃) can provide immediate Ca²⁺ but its dissolution is carbon-neutral, as it releases CO₂. Gypsum (CaSO₄) may precipitate CaCO₃ in alkaline soils while adding sulfur. Novel approaches include biochar–activated silicates, which combine mineral and carbon benefits. However, contamination risks must be assessed, as some basalts contain trace metals such as Ni and Cr. Coupling ERW with mycorrhizal trees in greenhouse studies has shown accelerated silicate weathering and increased soil carbon storage, demonstrating the promise of integrated mineral–biological approaches.

7.4. Biotechnological Routes: Engineering Cyanobacteria, Plants, and Microbiomes for Enhanced Carbonate Precipitation

Biotechnological innovations offer longer-term, higher-tech strategies for enhancing biomineralization. One vision is the engineering of plants or their microbial symbionts to increase production of biomineral precursors. For example, genetically modifying trees to exude more organic acids (oxalate or citrate) could intensify weathering and carbonate precipitation. Selective breeding and screening of high-biomineralizing varieties, such as crops with superior phytolith content, provide more immediate, tractable options [

112].

Microbiome engineering presents another frontier. Designer root-associated consortia could be constructed to overexpress urease or carbonic anhydrase, maximizing calcite formation. Synthetic biology approaches are also exploring cyanobacteria engineered for enhanced, light-driven calcium carbonate precipitation, inspired by their geological role in ancient carbonate rock formations [

31]. Such strategies could form the basis of a sustainable carbonate economy, recycling CO₂ from industrial emissions into durable mineral products [

35]. However, these remain nascent and face significant biosafety and regulatory scrutiny before real-world application.

8. Scaling, Permanence, and Climate Accounting

8.1. Estimates of Potential C Removal per Hectare Under Optimistic vs. Conservative Scenarios (OCP, PhytOC, MICP + ERW)

The quantitative potential of these pathways is a critical determinant of their value as a climate solution. A large-scale ERW trial in the US Corn Belt demonstrated a cumulative CDR potential of 10.5 ± 3.8 t CO₂/ha over four years of annual basalt application. Global biogeochemical models project that if ERW were deployed across major agricultural regions worldwide, it could sequester up to two billion metric tons of CO₂ annually, even after accounting for operational emissions from mining and transport. The global PhytOC sink from croplands alone is estimated at 26.35 ± 10.22 Tg CO₂/yr, with rice, wheat, and maize as the dominant contributing crops [

23]. The classic OCP system of an iroko tree is estimated to sequester one ton of calcium carbonate in the soil over its lifetime.

Estimating carbon removal at scale remains challenging due to variability. As a rough guide, high-performance OCP systems (e.g., dense stands of iroko-like trees) might fix on the order of 0.5–2 t CO₂/ha·yr as soil carbonates (optimistic case), whereas PhytOC in typical cereal agriculture often contributes only ~0.02–0.1 t CO₂/ha·yr. MICP in croplands (with active urea/rock application) could similarly achieve a few hundred kg CO₂/ha·yr. Enhanced rock weathering has the largest theoretical scale: modeling suggests that applying basalt dust to ~10% of global croplands and forests (hundreds of Mha) could remove ~1–4 Gt CO₂/yr. When combined (for example, agroforestry with oxalogenic trees on basalt-amended soils), conservative scenarios might reach hundreds of kg C/ha·yr (i.e., 1–2 t CO₂/ha·yr), whereas optimistic tallies could exceed 10 t CO₂/ha·yr in ultra-favorable contexts [

23]. At a national or global level, preliminary budgets have not yet been formulated for these processes, but they likely represent a modest fraction of total anthropogenic emissions. Nonetheless, even a few percent contribution (tens of Gt CO₂ over decades) could be meaningful.

Optimistic integrated scenarios suggest 2–5 t CO₂/ha·yr removal, with conservative cases at 0.5–1 t. Global drylands alone may represent a potential sink of 1–2 Gt CO₂/yr.

8.2. Residence Times and Stability

The fundamental advantage of biomineralization lies in permanence. Unlike organic carbon in biomass, which is part of a relatively short cycle of years to decades, the mineralized carbon in soil inorganic carbon (SIC) has an extremely long residence time. SIC stocks have a mean residence time of ~78,000 years and turnover times spanning millennia to millions of years, making them one of the most durable forms of carbon sequestration. PhytOC, while a form of organic carbon, is physically protected within the phytolith matrix, giving it high stability that is believed to last for millennia [

113].

Pedogenic calcite can persist for hundreds to tens of thousands of years in stable soils, while phytolith carbon (encased in SiO₂) resists decomposition for millennia. In contrast, organic carbon in plant biomass and litter typically turns over on decadal scales. However, this permanence is not guaranteed: the form of the precipitated mineral matters. Metastable polymorphs such as vaterite and aragonite are more susceptible to dissolution than calcite, thereby introducing a risk of impermanence [

114]. Moreover, uncertainties remain—soil conditions (e.g., acid rain, invasive species, or land-use change) could accelerate dissolution, potentially releasing CO₂. Residence times of carbonate are also climate-dependent: warmer and wetter conditions can increase dissolution rates. Thus, while SIC and PhytOC are considered highly stable, more field data are required to quantify their persistence under realistic management regimes.

8.3. Co-Benefits and Trade-Offs

The deployment of biomineralization-based interventions such as enhanced rock weathering (ERW), microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP), and organic carbon precipitation (OCP) is associated with a suite of agronomic and ecological co-benefits. Empirical studies have demonstrated that ERW can substantially enhance edaphic fertility and augment crop yields by 12–16%, largely attributable to reductions in soil acidification and concomitant improvements in nutrient availability. Processes such as OCP and MICP actively modulate rhizosphere pH, thereby mobilizing otherwise recalcitrant pools of phosphorus and micronutrients, while agroforestry-based deployment strategies integrate carbon sequestration with ecosystem service provision, including soil structural enhancement, hydrological regulation, and biodiversity conservation. A salient example is the integration of fig (Ficus spp.) in agroecosystems, which simultaneously strengthens food security and long-term carbon storage. In addition, mineral inputs such as basaltic rock dust and carbonate precipitates contribute physiochemically by supplying silica, potassium, and trace micronutrients, elevating soil calcium and magnesium pools, improving cation exchange capacity, and mitigating aluminum-induced phytotoxicity in acidified substrates. Moreover, MICP-mediated carbonate crystallization has been reported to enhance soil aggregation, thereby improving water retention and resistance to erosive forces, further reinforcing the multifunctional benefits of biomineralization strategies [

80].

Notwithstanding these advantages, the large-scale implementation of biomineralization pathways is accompanied by non-trivial biogeochemical trade-offs and potential ecological risks. Mineral amendments used in ERW may inadvertently mobilize and accumulate toxic trace elements, notably nickel and chromium, thereby introducing ecotoxicological hazards to soils and aquatic ecosystems, necessitating rigorous geochemical oversight. Similarly, the alkalinizing effects of carbonate precipitation, while beneficial in acidic substrates, can induce deleterious chemical imbalances in already alkaline soils, leading to nutrient precipitation and reduced bioavailability of phosphorus and essential micronutrients. Certain MICP pathways, such as dissimilatory sulfate reduction, yield hydrogen sulfide—a phytotoxic and environmentally hazardous gas—while ureolytic MICP generates ammonia, which, if unmanaged, poses risks of eutrophication and nitrous oxide (N₂O) emissions. Furthermore, the water-intensive nature of some mineralization methods raises sustainability concerns in arid and semi-arid agroecosystems. Beyond biogeochemical constraints, large-scale inputs of pulverized silicate rock or urea fertilizers heighten the risk of nitrate leaching and heavy metal contamination. Land-use trade-offs also emerge as a critical dimension, as dedicating agricultural land or forest biomes to carbon mineralization plantations or bioenergy crops (e.g., switchgrass) may exacerbate food security challenges, disrupt local livelihoods, and generate profound ethical and socio-environmental justice concerns. Finally, a comprehensive life-cycle analysis of mining, comminution, and transportation energy demands relative to the magnitude of carbon drawdown is essential to determine the techno-economic viability and sustainability of these interventions [

115]. (

Table 4)

8.4. Inclusion in Carbon Markets and MRV Requirements

Currently, most carbon accounting systems focus on organic carbon (forests, soils) and recognize only limited inorganic pathways. To include biomineralization, new protocols would be required. Key challenges include establishing baseline carbonate levels, attributing changes to management versus background weathering, and certifying permanence. Double-counting remains a concern: for instance, if a forest is already credited for biomass growth, should its soil carbonate accrual also count?

Verification would require specific measurements and monitoring frameworks. Some proposals suggest combining mineral carbon sinks with existing frameworks (e.g., co-crediting crop residue management for PhytOC). Until standardized methodologies are established, large-scale implementation in carbon markets will lag. Nonetheless, voluntary carbon pilots may emerge for “enhanced soil carbon” projects that explicitly track inorganic carbon. MRV (Measurement, Reporting, Verification) is essential to ensure crediting accuracy, with baseline-setting required to avoid double-counting.

9. Risks, Ethical & Governance Considerations

9.1. Environmental Risks

While biomineralization offers significant promise for carbon sequestration, it is not without potential environmental risks that must be carefully assessed and managed. Large-scale interventions carry inherent ecological uncertainties. Chemical imbalances are a prime concern: soil alkalinization through mineral amendments (e.g., MICP, ERW, or carbonate additions) may mobilize toxic heavy metals such as nickel and chromium, which are often present in silicate or basaltic rocks [