1. Introduction

Leukemia is a group of hematologic malignancies characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of immature or dysfunctional hematopoietic cells [

1]. Despite advances in targeted therapies, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and immunotherapies, leukemia continues to be a major clinical and socioeconomic burden globally. The incidence rates vary across subtypes, with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) remaining aggressive diseases associated with high relapse rates and poor prognosis in many patient populations. Chronic leukemias, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), are more indolent but present challenges with drug resistance and disease progression [

2].

Recent advances in genomics and immunotherapy have shifted focus towards the metabolic dependencies of cancer cells [

3]. Leukemia cells, like other malignancies, rewire their metabolism to meet the increased energetic and biosynthetic demands [

4]. While glucose and glutamine metabolism have been extensively studied, emerging evidence highlights the critical role of taurine, a semi-essential sulfur-containing β-amino acid, in leukemia biology [

5]. Taurine is abundant in leukocytes, the CNS, and muscle tissue, where it regulates osmotic balance, calcium signaling, membrane stabilization, redox homeostasis, and mitochondrial function. Unlike most amino acids, taurine is not incorporated into proteins but acts as a versatile small-molecule modulator [

6].

Cellular taurine levels are tightly regulated by the taurine transporter (TauT), encoded by SLC6A6 [

7]. TauT governs taurine uptake and intracellular accumulation. Dysregulation of SLC6A6 expression has been observed in multiple cancers, with preclinical evidence suggesting that leukemic cells exploit this pathway to sustain proliferation, resist chemotherapy-induced stress, and modulate interactions with the bone marrow niche [

8].

The taurine–TauT axis represents a promising metabolic vulnerability in leukemia [

9]. Understanding its role could not only provide insight into leukemia pathogenesis but also unveil novel therapeutic strategies [

10]. This review explores the clinical burden of leukemia, taurine biology, the structure and function of SLC6A6, and the evidence linking the taurine–TauT axis to leukemogenesis. We also explore therapeutic implications and outline future directions for translating this knowledge into clinical benefit.

2. Clinical Burden of Leukemia

2.1. Global Incidence and Epidemiological Landscape

Leukemia is among the most studied hematological malignancies, yet it continues to impose a substantial clinical burden worldwide [

11]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, more than 475,000 new cases of leukemia are diagnosed annually, with close to 312,000 deaths, underscoring its impact on global health. The disease is not homogeneous but encompasses a spectrum of acute and chronic subtypes, each with distinct age distributions, biological characteristics, and treatment outcomes [

12].

In high-income countries, survival rates for certain leukemias — particularly childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) — have improved significantly due to advances in chemotherapy protocols and supportive care. However, outcomes for adults with ALL or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remain poor, with five-year overall survival often below 30% in older patients. In low- and middle-income countries, the disparity is even more striking, as access to diagnostics, cytogenetics, and novel therapies is limited. Chronic leukemias, including chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), display slower progression but contribute substantially to long-term morbidity, particularly among older populations [

13].

2.2. Disease Subtypes and Shared Clinical Burden

Although acute and chronic leukemias differ in their biology and clinical presentation, they share several unifying features that shape the overall disease burden. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains the most lethal subtype, particularly in older adults where survival rarely exceeds 20–30% [

14]. Even in younger patients, remission is often followed by relapse, as leukemic stem cells persist in protected bone marrow niches and resist chemotherapy. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common childhood malignancy, has seen remarkable progress with cure rates surpassing 85% in pediatric populations. Yet in adults, survival remains below 40%, and relapse continues to be the primary cause of treatment failure [

15]. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) exemplifies the success of targeted therapy, as tyrosine kinase inhibitors have transformed a once fatal disease into a manageable chronic condition. However, quiescent stem cells survive despite continuous therapy, creating reservoirs for minimal residual disease and relapse once treatment is discontinued. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common adult leukemia in Western populations, is equally marked by heterogeneity [

16]. While some patients live for decades without requiring therapy, others progress rapidly and ultimately develop resistance to targeted agents such as BTK and BCL2 inhibitors.

Together, these clinical observations reveal a consistent pattern: across all major leukemia subtypes, relapse is the dominant contributor to mortality, therapy resistance is driven not only by genetic evolution but also by metabolic adaptations, and bone marrow niches provide sanctuary environments where malignant cells can survive therapeutic stress. These shared characteristics emphasize that the true burden of leukemia lies not only in incidence and mortality, but also in the persistence of resistant cellular populations. Mounting evidence suggests that taurine uptake through the taurine transporter SLC6A6 contributes to this resilience, offering malignant cells a biochemical buffer against oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [

17]. This common thread underscores the clinical relevance of the taurine–TauT axis as a unifying metabolic vulnerability across otherwise distinct forms of leukemia.

2.3. Emerging Clinical Themes Across Subtypes

Across AML, ALL, CML, and CLL, several unifying themes emerge. First, relapse remains the dominant contributor to disease burden. Despite therapeutic advances, most patients who relapse have poor outcomes, underscoring the centrality of residual disease and stem-cell persistence. Second, therapy resistance increasingly reflects metabolic reprogramming. From chemotherapy resistance in AML and ALL to TKI resistance in CML and targeted therapy escape in CLL, malignant cells adapt not only through genetic changes but also by exploiting metabolic safeguards [

18]. Third, the bone marrow microenvironment provides sanctuary conditions that reinforce these adaptations, supplying nutrients and shielding blasts from therapeutic stress.

In this context, taurine biology acquires clinical relevance. Its uptake via SLC6A6 provides leukemic cells with a versatile tool to withstand oxidative stress, stabilize mitochondria, and interact with the niche [

19]. While genetics initiates leukemia, it is often metabolic resilience that sustains it. Appreciating this interplay reframes the clinical burden of leukemia not simply as a matter of incidence and mortality but as a problem of biological persistence — one in which taurine plays an underrecognized but pivotal role.

3. Taurine Biology: Cellular and Molecular Functions

Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) is one of the most abundant free amino acid–like compounds in mammalian tissues, constituting up to 50–60 mM in leukocytes and reaching millimolar concentrations in the central nervous system, retina, myocardium, and skeletal muscle. Unlike canonical amino acids, taurine is not incorporated into proteins but acts as a low–molecular weight modulator with pleiotropic physiological roles that are increasingly recognized as central to cancer biology [

6].

3.1. Chemical Structure and Discovery

Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) is a unique sulfur-containing amino acid discovered in the early 19th century, originally isolated from ox bile — hence the name, derived from

Bos taurus [

6]. Unlike proteinogenic amino acids, taurine lacks a carboxyl group and instead terminates with a sulfonic acid moiety. This seemingly minor structural difference endows taurine with distinct physicochemical properties: it is highly polar, exists predominantly in zwitterionic form at physiological pH, and exhibits remarkable chemical stability. These properties explain taurine’s high solubility, its ability to accumulate to millimolar concentrations, and its suitability as an osmolyte and antioxidant [

20].

Although taurine is not incorporated into proteins, it is one of the most abundant free amino acids in mammalian tissues [

6]. Concentrations range from 5 to 50 mM in excitable tissues such as retina, heart, and skeletal muscle, and even higher levels are found in leukocytes. Its abundance and multifunctionality make taurine an essential mediator of cellular homeostasis, despite its non-proteinogenic status.

Table 1 summarizes the Taurine function in AML, ALL, CLL and CML.

3.2. Biosynthesis and Dietary Sources

Taurine is classified as a conditionally essential amino acid

. While mammals can synthesize taurine endogenously, production rates often fail to meet cellular demands under stress, rapid growth, or disease [

25].

The primary biosynthetic pathway begins with cysteine. Cysteine dioxygenase catalyzes the conversion of cysteine to cysteine sulfinic acid, which is then decarboxylated by cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase (CSAD) to hypotaurine. Hypotaurine is subsequently oxidized to taurine. Alternative minor pathways, including degradation of homocysteine and cysteamine, contribute in specific tissues but are less significant quantitatively [

26].

Dietary sources are important, particularly in humans where hepatic CSAD activity is relatively low compared with other mammals. Taurine is abundant in seafood, meat, and dairy products. Vegetarians and vegans often exhibit lower plasma taurine levels, though compensatory upregulation of transport mechanisms usually maintains intracellular pools. Nevertheless, under stress conditions, endogenous and dietary taurine may both be insufficient, necessitating robust uptake systems such as SLC6A6 [

25].

3.3. Tissue Distribution and Cellular Uptake

Taurine distribution is highly tissue-specific, reflecting its diverse physiological roles. The retina contains some of the highest taurine concentrations known in biology, where it regulates photoreceptor stability. In the brain, taurine modulates neuronal excitability and osmoregulation, acting as a weak agonist at glycine and GABA receptors. Cardiac and skeletal muscle are similarly enriched, where taurine supports calcium handling and contractile function [

27].

The kidney and liver demonstrate high taurine levels owing to their roles in osmoregulation and bile acid conjugation. Importantly, leukocytes are also exceptionally taurine-rich, with concentrations reaching 30–50 mM, a reflection of their exposure to oxidative bursts and their reliance on taurine for cytoprotection [

28].

Given taurine’s polarity, passive diffusion across membranes is negligible. Intracellular accumulation depends almost exclusively on the high-affinity, sodium- and chloride-dependent transporter SLC6A6 (TauT).[

29] This transporter enables cells to concentrate taurine up to 1,000-fold above plasma levels, highlighting the tight regulation of taurine homeostasis.

3.4. Physiological Functions

Taurine has been described as a “biological jack-of-all-trades,” reflecting its involvement in numerous processes. Key physiological roles include:

Osmoregulation: Taurine functions as an organic osmolyte, balancing cell volume during hypo- or hyperosmotic stress. This role is particularly vital in kidney medullary cells, neurons, and immune cells that encounter fluctuating osmotic environments [

30].

Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Defense: Taurine directly scavenges reactive species such as hypochlorous acid (HOCl), forming taurine chloramine (TauCl). TauCl is not only less cytotoxic but also possesses anti-inflammatory properties, modulating NF-κB signaling and dampening excessive immune activation [

31].

Calcium Homeostasis: Taurine regulates intracellular calcium fluxes, influencing processes as diverse as cardiac contractility, neurotransmitter release, and lymphocyte activation [

32]. It interacts with calcium-binding proteins and modulates ion channel activity.

Mitochondrial Function: Taurine is conjugated to uridine residues in mitochondrial tRNAs, ensuring accurate decoding of codons for respiratory chain proteins. Defects in taurine-conjugated tRNAs impair oxidative phosphorylation and are implicated in mitochondrial diseases such as MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, stroke-like episodes) [

33].

Bile Acid Conjugation: In hepatocytes, taurine conjugates with bile acids to form taurocholate and related compounds, essential for lipid solubilization, absorption, and cholesterol metabolism [

28].

Neurotransmission and Development: Taurine acts as a neuromodulator during brain development, supporting neuronal proliferation, migration, and synaptogenesis [

34]. Deficiency during perinatal periods causes severe neurological dysfunction in animal models.

3.5. Taurine in Immunity and Stress Responses

One of taurine’s most striking features is its enrichment in immune cells. Neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes accumulate taurine at concentrations among the highest in the body [

35]. During infection, myeloperoxidase activity in neutrophils generates HOCl as part of the oxidative burst. Taurine reacts rapidly with HOCl to form TauCl, thereby detoxifying a harmful oxidant and simultaneously producing a molecule with regulatory properties. TauCl modulates pro-inflammatory cytokine production, reduces tissue damage, and promotes resolution of inflammation [

31].

Beyond innate immunity, taurine contributes to adaptive immune function. It stabilizes T-cell survival under oxidative stress and enhances mitochondrial resilience during activation. In B cells, taurine supports antibody production indirectly through redox control. Collectively, these functions highlight taurine as both a cytoprotective molecule and an immunoregulatory signal.

3.6. Insights from Deficiency Models

The importance of taurine is underscored by deficiency states. In cats, which lack CSAD activity, dietary taurine deficiency leads to retinal degeneration, dilated cardiomyopathy, and reproductive failure. In humans, taurine deficiency is rare but has been described in premature infants, individuals on long-term parenteral nutrition, and certain metabolic disorders. Clinical features include developmental delay, visual impairment, and cardiomyopathy.

Knockout models in mice further highlight taurine’s indispensability. TauT-deficient mice exhibit growth retardation, retinal degeneration, impaired reproduction, and cardiomyopathy. Hematopoietic effects include reduced lymphocyte survival and impaired neutrophil function, consistent with taurine’s role in immunity [

36]. These models provide mechanistic insight into how taurine scarcity impacts systems under high oxidative or metabolic stress — conditions reminiscent of the leukemic microenvironment.

3.7. Relevance to Hematopoiesis and Leukemia

`The hematopoietic system is inherently taurine-rich. Stem and progenitor cells, as well as differentiated leukocytes, accumulate taurine to protect against oxidative fluctuations during proliferation and activation [

22]. This baseline enrichment means that leukemias, which arise from these cells, inherit a taurine dependency from the outset.

Leukemic blasts and stem cells are frequently exposed to chemotherapy-induced ROS, hypoxic bone marrow niches, and metabolic competition. Taurine uptake via TauT enables them to survive these pressures, buffering oxidative stress, stabilizing mitochondrial translation, and maintaining ionic balance [

32]. In AML, high intracellular taurine correlates with resistance to cytarabine, while in ALL, taurine supplementation protects blasts from methotrexate and vincristine. In CLL, plasma taurine levels are elevated, reflecting malignant B-cell turnover and uptake [

37].

Thus, taurine biology is not merely a background physiological process but a foundation upon which leukemic adaptations are built. By appropriating taurine’s antioxidant and mitochondrial roles, leukemias achieve a survival advantage that contributes to therapy resistance and relapse.

4. The Taurine Transporter (SLC6A6): Structure, Regulation, and Function

4.1. Structure and Transport Mechanism of SLC6A6 (TauT)

The taurine transporter, or TauT, encoded by the SLC6A6 gene

, is a member of the solute carrier family 6 (SLC6), which comprises sodium- and chloride-dependent neurotransmitter transporters such as those for serotonin, dopamine, and GABA [

38]. TauT is a high-affinity, highly selective transporter that sustains the disproportionately high intracellular taurine concentrations characteristic of immune cells, muscle, and neurons.

TauT is an integral membrane protein composed of twelve transmembrane (TM) α-helices, organized into two inverted repeats of five helices, with additional N- and C-terminal helices stabilizing the fold. This structural organization, common across SLC6 transporters, forms the scaffold for taurine recognition and translocation. While a high-resolution structure of TauT itself has not been solved, homology models based on related SLC6 family members provide insight into its architecture. The substrate-binding pocket is nestled between TM1, TM3, TM6, and TM8, where taurine is coordinated together with two sodium ions and one chloride ion [

38].

The transport cycle adheres to the alternating access model. In the outward-facing state, the binding pocket is accessible to extracellular taurine, which binds cooperatively with the coupled ions. A conformational rearrangement then occludes the pocket before transitioning into an inward-facing state, allowing release of taurine and ions into the cytoplasm. Resetting the transporter requires ion dissociation and structural realignment. This process allows TauT to concentrate taurine intracellularly up to 1000-fold higher than plasma levels, a property central to its physiological and pathological roles.

TauT’s substrate affinity is exceptionally high (Km ~10 µM), ensuring efficient uptake even in nutrient-scarce conditions, such as hypoxic bone marrow niches or chemotherapy-stressed microenvironments. Although TauT can also transport β-alanine and structurally related sulfonic acids, taurine remains its primary substrate, reflecting strong evolutionary specialization [

39].

Beyond transport, TauT function is modulated by regulatory elements embedded in its structure. Phosphorylation motifs on intracellular termini regulate trafficking to the plasma membrane, while allosteric interactions fine-tune taurine affinity under varying cellular stresses. In leukemia, where survival hinges on adaptation to metabolic and oxidative pressure, this high-affinity, ion-coupled transport system provides a critical biochemical lifeline.

Figure 1.

Taurine Biology and Transport via SLC6A6 (TauT). (A) The chemical structure of taurine, highlighting the amino (NH₂) and sulfonic acid (SO₃H) groups, with its unique sulfonic acid moiety replacing the typical carboxyl group in amino acids. (B) Taurine biosynthesis pathway, from cysteine to taurine, and dietary sources such as seafood, meat, and dairy. (C) Tissue distribution of taurine, showing high concentrations in the retina, brain, heart, muscle, and leukocytes, with functional annotations for each tissue. (D) TauT (SLC6A6) transporter mechanism, co-transporting taurine with Na⁺ and Cl⁻ into cells, where it stabilizes mitochondrial function and reduces oxidative stress.

Figure 1.

Taurine Biology and Transport via SLC6A6 (TauT). (A) The chemical structure of taurine, highlighting the amino (NH₂) and sulfonic acid (SO₃H) groups, with its unique sulfonic acid moiety replacing the typical carboxyl group in amino acids. (B) Taurine biosynthesis pathway, from cysteine to taurine, and dietary sources such as seafood, meat, and dairy. (C) Tissue distribution of taurine, showing high concentrations in the retina, brain, heart, muscle, and leukocytes, with functional annotations for each tissue. (D) TauT (SLC6A6) transporter mechanism, co-transporting taurine with Na⁺ and Cl⁻ into cells, where it stabilizes mitochondrial function and reduces oxidative stress.

4.2. Tissue Distribution with Emphasis on Hematopoiesis

TauT expression is widespread but tissue-selective, enriched in organs where taurine-dependent processes are critical. The transporter is highly expressed in the kidney and liver, which regulate systemic taurine balance, in the brain and retina, where taurine maintains excitability and neurotransmission, and in heart and skeletal muscle, where it supports contractility and calcium handling [

40].

Most relevant to leukemia, TauT expression is particularly abundant in leukocytes and hematopoietic progenitors. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes maintain millimolar intracellular taurine pools, a reflection of both high uptake and strong retention. These pools are mobilized during immune activation, buffering oxidative stress, calcium flux, and osmotic changes [

41].

This baseline enrichment is of critical significance: when hematopoietic progenitors undergo malignant transformation, they already exist in a taurine-rich context. The persistence or upregulation of SLC6A6 expression in leukemic blasts provides a metabolic advantage, enabling survival and proliferation in hostile microenvironments such as the hypoxic bone marrow niche.

4.3. Regulation of SLC6A6 Expression

TauT is a highly inducible transporter, responding dynamically to metabolic stress, environmental conditions, and oncogenic signaling. Its regulation occurs at multiple levels:

At the transcriptional level, the SLC6A6 promoter contains binding sites for TonEBP/NFAT5, a transcription factor activated under hyperosmotic conditions. This explains the strong induction of TauT in cells exposed to high-salt environments. [

40] Similarly, HIF-1α upregulates SLC6A6 under hypoxia, linking transporter expression to the oxygen-deprived niches that leukemic cells frequently inhabit. Oncogenic transcription factors such as c-Myc and NF-κB also drive TauT expression, integrating transporter regulation into broader oncogenic programs [

42].

At the post-transcriptional level, microRNAs play a role in fine-tuning SLC6A6 expression. For example, miR-98 and miR-3151 have been reported to destabilize SLC6A6 mRNA in cancer models, suggesting that altered miRNA landscapes in leukemia may indirectly enhance TauT levels [

43,

44].

At the environmental level, taurine deprivation triggers compensatory SLC6A6 upregulation, ensuring intracellular taurine homeostasis. Oxidative stress also upregulates TauT, reflecting the transporter’s role in redox buffering. Together, these regulatory mechanisms converge to maintain taurine uptake under precisely the conditions—hypoxia, ROS accumulation, nutrient scarcity—that define the leukemic bone marrow niche.

Table 2.

SLC6A6 (TauT) Expression and Its Implications in Leukemia Subtypes.

Table 2.

SLC6A6 (TauT) Expression and Its Implications in Leukemia Subtypes.

| Leukemia Subtype |

SLC6A6 Expression (TauT) |

Functional Role |

Mechanistic Implications |

Prognostic Implications |

Therapeutic Relevance |

References |

| AML |

Upregulated in blasts and LSCs |

Antioxidant protection, mitochondrial stabilization |

Elevated taurine reduces ROS accumulation and stabilizes mitochondrial OXPHOS, protecting against apoptosis |

High TauT expression correlates with poor prognosis, increased relapse rates, and adverse cytogenetics(e.g., FLT3-ITD, TP53) |

TauT inhibition sensitizes AML cells to chemotherapy (cytarabine, doxorubicin), targeting LSCs to reduce relapse |

[45] |

| ALL |

Elevated in relapsed B-ALL clones |

Calcium homeostasis, redox buffering |

Modulates intracellular calcium flux, stabilizes signaling pathways under stress, and prevents apoptosis |

High TauT expression linked to chemoresistance and relapse, particularly in pediatric |

Taurine supplementation protects from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, and TauT inhibition may improve treatment efficacy |

[46] |

| CML |

Enriched in quiescent LSCs, particularly in hypoxic niches |

Redox buffering, mitochondrial function |

Supports quiescent LSCs by buffering oxidative stress and maintaining mitochondrial function, enabling persistence under TKI therapy |

Persistent LSCs survive treatment, causing relapse despite long-term TKI therapy |

Targeting TauT could synergize with TKIs to eliminate persistent LSCs and prevent relapse |

[47] |

| CLL |

Upregulatedin leukemic B cells |

ROS buffering, immune modulation |

Buffers ROS, stabilizes mitochondria, and suppresses inflammatory immune responses via taurine-derived chloramines (TauCl) |

Elevated TauT expression correlates with resistance to BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib) and BCL2 inhibitors (venetoclax) |

|

[48] |

4.4. Dysregulation of TauT in Cancer

TauT dysregulation has been observed across a spectrum of malignancies. In glioblastoma, SLC6A6 upregulation confers protection against oxidative stress, while its inhibition reduces clonogenic growth. In colorectal cancer, high SLC6A6 expression correlates with poor survival and resistance to chemotherapy [

49]. Similarly, breast cancer cells overexpress TauT as part of their antioxidant defense machinery.

In hematologic malignancies, direct evidence is emerging from transcriptomic and functional studies. Analyses of RNA-seq datasets from TCGA (AML, CLL) and TARGET (ALL) reveal elevated SLC6A6 expression in subsets of patients compared with normal hematopoietic cells. Importantly, in AML, high SLC6A6 expression is enriched in adverse-risk cytogenetic subgroups, suggesting prognostic relevance [

50]. In CLL, SLC6A6 is more highly expressed in leukemic B cells than in their normal counterparts, consistent with a selective survival advantage.

4.5. Functional Evidence in Leukemia

Several experimental observations highlight the functional relevance of TauT in leukemogenesis

. In vitro studies demonstrate that taurine deprivation or pharmacological inhibition of SLC6A6 reduces leukemic blast survival, underscoring transporter dependency. Elevated TauT expression protects leukemia cells from chemotherapy-induced oxidative stress, particularly against cytarabine and doxorubicin, two standard AML drugs [

51]. Knockdown of SLC6A6 restores chemosensitivity, suggesting a causal role in resistance.

Of particular importance is the observation that leukemic stem cell (LSC)-enriched populations express higher SLC6A6 levels than bulk blasts. Given that LSC persistence is a major driver of relapse, TauT upregulation in these cells provides a mechanistic explanation for therapy resistance and long-term disease recurrence.

4.6. Microenvironmental Interactions

Leukemia does not exist in isolation but within the bone marrow microenvironment, where nutrient exchange, hypoxia, and redox imbalance shape disease progression.[

52] TauT plays a central role in mediating leukemic adaptation to this niche. Stromal and immune cells can release taurine, which is avidly imported by leukemic blasts via SLC6A6. This uptake buffers intracellular ROS, maintains osmotic stability, and protects against apoptosis.[

19]

Such metabolic symbiosis mirrors well-documented phenomena in solid tumors, where cancer cells exploit microenvironmental nutrient sharing (e.g., glutamine, lactate). In leukemia, TauT provides a similar axis of survival, allowing malignant blasts to thrive in otherwise hostile conditions. This not only sustains leukemia cells but may also suppress immune surveillance by dampening ROS-mediated cytotoxicity in the niche.

5. The Taurine–TauT Axis in Leukemia

5.1. Overview: Linking Taurine Biology to Leukemia

The convergence of taurine’s multifaceted biological functions with the metabolic vulnerabilities of leukemia provides a compelling rationale for considering the taurine–TauT axis as central to leukemogenesis. Leukemic blasts and leukemic stem cells (LSCs) exist in microenvironments characterized by hypoxia, oxidative stress, and nutrient limitation — all conditions under which taurine uptake via SLC6A6 becomes indispensable. Elevated intracellular taurine concentrations enable malignant cells to buffer redox stress, stabilize mitochondrial function, and resist apoptosis induced by chemotherapy [

51].

Importantly, leukocytes are inherently taurine-rich, meaning that malignant transformation occurs within a metabolic framework already primed to exploit taurine biology [

53]. Unlike many solid tumors, where taurine must be recruited as an auxiliary metabolite, leukemias arise in a cellular system where taurine is already abundant and physiologically relevant. This duality elevates the taurine–TauT axis from a background regulator to a driver of persistence and therapeutic resistance in hematologic malignancies.

5.2. Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Among all leukemia subtypes, AML provides the strongest evidence linking taurine metabolism to disease biology. AML blasts harbor higher intracellular taurine pools than normal progenitors, paralleled by increased SLC6A6 expression [

39]. Transcriptomic analyses from TCGA and BeatAML cohorts confirm that SLC6A6 overexpression correlates with adverse-risk cytogenetics, including complex karyotypes, TP53 mutations, and FLT3-ITD [

54,

55]. These associations underscore that reliance on taurine uptake is amplified in aggressive disease.

Functionally, taurine promotes AML cell survival on multiple levels. By detoxifying ROS directly through taurine chloramine formation and indirectly through mitochondrial stabilization, taurine confers resistance to chemotherapy-induced oxidative stress. Blocking TauT restores ROS sensitivity, amplifying the efficacy of agents such as cytarabine and doxorubicin. Taurine also interferes with intrinsic apoptotic signaling by preventing mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and reducing cytochrome c release, thereby diminishing caspase activation [

22]. Furthermore, LSCs — the primary reservoir for relapse — express disproportionately high levels of SLC6A6 compared with bulk blasts. By maintaining mitochondrial fitness and buffering stress within hypoxic niches, taurine uptake equips LSCs to endure therapy and repopulate disease.

Collectively, these findings highlight AML’s metabolic “addiction” to the taurine–TauT axis, particularly in contexts of therapeutic stress and stem-cell persistence.

5.3. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

In ALL, the data are less mature but point toward a similar taurine-mediated survival advantage. Pediatric ALL blasts contain elevated intracellular taurine compared with normal lymphoblasts, reflecting both enhanced uptake and altered turnover. Analyses from the TARGET-ALL cohort indicate that relapsed B-ALL clones display upregulated SLC6A6, implicating TauT in relapse biology [

56].

Mechanistically, taurine modulates calcium homeostasis, which is critical for ALL proliferation and survival. By stabilizing Ca²⁺ fluxes under stress, taurine dampens apoptotic signaling and maintains growth pathways. Functional assays show that taurine supplementation reduces apoptosis induced by frontline agents such as methotrexate and vincristine, while taurine depletion sensitizes blasts to these drugs [

57]. Within the bone marrow niche, where hypoxia and nutrient scarcity prevail, upregulation of TauT may serve as a key adaptation that enables resistant clones to persist and expand.

Although less extensively documented than in AML, these converging lines of evidence suggest that the taurine–TauT axis plays an underappreciated role in ALL therapy resistance and relapse, particularly in the pediatric setting where bone marrow microenvironmental support is critical.

5.4. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML)

In CML, tyrosine kinase inhibitors have redefined disease management, yet complete eradication remains elusive due to the persistence of LSCs [

58]. These stem cells reside in hypoxic bone marrow niches and survive independently of BCR–ABL1 signaling, relying instead on metabolic adaptations for long-term persistence. Transcriptomic profiling indicates that SLC6A6 expression is enriched in quiescent stem-like fractions, implicating taurine uptake as a contributor to minimal residual disease [

59].

Experimental studies suggest that taurine depletion sensitizes CML cells to TKIs, providing proof-of-principle that TauT activity supports survival under kinase blockade [

60]. While the evidence is not as extensive as in AML, these observations raise the possibility that targeting taurine metabolism could synergize with TKIs to overcome stem-cell persistence and improve treatment-free remission rates.

5.5. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

CLL offers a unique lens into taurine biology due to its origin from mature B lymphocytes. CLL cells display significantly higher SLC6A6 expression than their normal counterparts, consistent with the elevated oxidative stress imposed by aberrant B-cell receptor signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction [

61]. Taurine uptake buffers this stress, stabilizes mitochondrial function, and reduces apoptotic signaling, thereby prolonging malignant B-cell survival.

Beyond cell-intrinsic effects, taurine metabolism also contributes to immune evasion in CLL[

9]. Taurine-derived chloramines (TauCl) suppress inflammatory signaling, dampening anti-leukemic immune responses. Clinically, metabolomic studies demonstrate that plasma taurine levels are elevated in CLL patients, reflecting increased uptake and turnover. Importantly, TauT upregulation correlates with resistance to targeted agents such as BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib) and the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax, positioning taurine uptake as a potential resistance node in the era of targeted therapy [

62].

Figure 2.

The Taurine–TauT Axis in Leukemia Subtypes. Panel A illustrates the role of taurine in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), where taurine helps buffer chemotherapy-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and sustains leukemic stem cells (LSCs), contributing to relapse. Panel B shows acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), where taurine stabilizes calcium (Ca²⁺) flux, reducing apoptosis induced by frontline chemotherapy drugs such as methotrexate (MTX) and vincristine (VCR). Panel C highlights chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), where taurine supports stem cell survival in hypoxic bone marrow niches under tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy, contributing to minimal residual disease (MRD) persistence. Panel D focuses on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), where taurine overexpression aids in ROS buffering and contributes to drug resistance, particularly against Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitors.

Figure 2.

The Taurine–TauT Axis in Leukemia Subtypes. Panel A illustrates the role of taurine in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), where taurine helps buffer chemotherapy-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and sustains leukemic stem cells (LSCs), contributing to relapse. Panel B shows acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), where taurine stabilizes calcium (Ca²⁺) flux, reducing apoptosis induced by frontline chemotherapy drugs such as methotrexate (MTX) and vincristine (VCR). Panel C highlights chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), where taurine supports stem cell survival in hypoxic bone marrow niches under tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy, contributing to minimal residual disease (MRD) persistence. Panel D focuses on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), where taurine overexpression aids in ROS buffering and contributes to drug resistance, particularly against Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitors.

5.6. Integrative Perspective

When viewed collectively, the taurine–TauT axis emerges as a unifying metabolic adaptation across otherwise distinct leukemias. In AML and ALL, it equips blasts and stem-like cells to withstand chemotherapy, enabling relapse. In CML, it sustains quiescent LSCs under TKI pressure, perpetuating minimal residual disease. In CLL, it buffers ROS and contributes to targeted therapy resistance while simultaneously facilitating immune evasion [

63].

What distinguishes taurine uptake from other metabolic pathways is its reliance on a single high-affinity transporter, SLC6A6. This lack of redundancy means that leukemic cells dependent on taurine biology are particularly vulnerable to transporter inhibition. By converging on redox buffering, mitochondrial stability, apoptosis regulation, and stem-cell persistence, the taurine–TauT axis represents not only a mechanistic cornerstone of leukemic survival but also a tractable therapeutic target.

5.7. Clinical Studies on the Taurine–TauT Axis in Leukemia

Clinical studies supporting the relevance of the taurine–TauT axis in leukemia have provided important insights into its contribution to disease progression and therapy resistance. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), transcriptomic analyses from both the TCGA and BeatAML cohorts have shown elevated SLC6A6 expression in leukemic blasts compared with normal progenitors [

64]. This upregulation correlates with adverse cytogenetic profiles such as TP53 mutations and FLT3-ITD, which are associated with poor prognosis and high relapse rates. High SLC6A6 expression in these patient populations suggests that taurine uptake is a critical metabolic adaptation that supports leukemic survival in aggressive disease settings [

59]. Furthermore, in vitro studies have demonstrated that taurine supplementation helps mitigate chemotherapy-induced ROS, while TauT inhibition sensitizes blasts to chemotherapy agents such as cytarabine and doxorubicin, highlighting the role of taurine in chemoresistance [

65].

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), although the data are less extensive, early studies indicate that SLC6A6 expression is also upregulated in treatment-resistant B-ALL clones. Transcriptomic data from the TARGET-ALL cohort reveal that relapsed ALL samples display higher taurine uptake, which correlates with enhanced survival of leukemic blasts under oxidative stress [

66]. Functional assays have shown that taurine protects ALL blasts from apoptosis induced by methotrexate and vincristine, two standard chemotherapy agents in the treatment protocol. These findings suggest that taurine may play a protective role in chemoresistance by stabilizing calcium signaling and maintaining redox balance in ALL cells.

Although, CML is less studied in terms of taurine metabolism, emerging data indicate that quiescent CML stem cells exhibit increased SLC6A6 expression, which may contribute to their survival in the hypoxic bone marrow niche. Despite successful TKI treatment targeting the BCR–ABL1 fusion protein, CML stem cells persist in a metabolically unique state, relying on mitochondrial function and redox buffering to survive [

67]. Preliminary studies suggest that taurine depletion sensitizes CML cells to TKI-induced apoptosis, pointing to a potential therapeutic strategy targeting TauT in conjunction with TKIs to improve patient outcomes and eradicate minimal residual disease [

60].

Finally, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL

) provides compelling evidence for taurine's role in immune evasion and therapy resistance. Plasma taurine levels are significantly elevated in CLL patients compared with healthy controls, indicating that taurine turnover is increased in leukemic B cells [

68]. SLC6A6 expression in CLL cells is notably higher than in normal B cells, correlating with their increased oxidative stress due to chronic BCR signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction. In vitro, taurine uptake has been shown to buffer ROS, stabilize mitochondria, and promote cell survival in oxidative niches, all of which contribute to therapeutic resistance [

32]. Notably, CLL patients who are resistant to BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib) and BCL2 inhibitors (venetoclax) have been shown to rely more heavily on TauT for maintaining redox homeostasis, suggesting that the taurine–TauT axis plays a critical role in resistance to targeted therapies [

48].

Taken together, these clinical studies suggest that the taurine–TauT axis is a unifying metabolic feature across leukemia subtypes, contributing to therapy resistance and disease persistence. The consistent correlation of high SLC6A6 expression with poor prognosis and relapse across AML, ALL, CML, and CLL positions the taurine–TauT axis as a promising therapeutic target for overcoming metabolic adaptations and improving patient outcomes.

Table 3.

Therapeutic Strategies and Associated Challenges for Targeting the Taurine–TauT Axis.

Table 3.

Therapeutic Strategies and Associated Challenges for Targeting the Taurine–TauT Axis.

| Therapeutic Strategy |

Mechanism of Action |

Challenges |

Potential Impact |

Clinical Implications |

References |

| Direct TauT Inhibition |

Inhibition of SLC6A6 transporter prevents taurine uptake into leukemic cells, disrupting oxidative stress balance and mitochondrial stability. |

Lack of selective inhibitors for TauT; off-target effects on other SLC6 family members. |

Increased ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, cell death in leukemic cells. |

Can enhance chemotherapy efficacy (cytarabine, doxorubicin) by sensitizing blasts to oxidative stress. |

[69] |

| Chemosensitization via TauT |

Combining TauT inhibition with conventional chemotherapy agents (cytarabine, doxorubicin) to increase their efficacy by reducing ROS protection. |

Risk of toxicity to normal cells; need for optimal dosing strategies. |

Synergistic therapy, increased sensitivity of leukemic cells to chemotherapy. |

Potential for combined regimen therapy, especially in high-risk AML and ALL patients. |

[70] |

| Leukemic Stem Cell Targeting |

Disrupts mitochondrial function and redox buffering in quiescent LSCs by inhibiting TauT. |

Potential harm to normal stem cells; difficulty in targeting LSCs specifically. |

Reduced relapse, eradication of minimal residual disease (MRD). |

TauT inhibition can target LSCs that persist post-chemotherapy, reducing relapse risk in AML and CML. |

[71] |

| Systemic Taurine Modulation |

Dietary taurine restriction or taurine analogs to modify systemic taurine levels, indirectly affecting leukemia progression. |

Limited ability to control taurine levels precisely; systemic effects on other tissues (e.g., brain, heart). |

Potential for modulating metabolic environment of leukemia. |

Adjunctive therapy to enhance chemotherapy or support normal tissue function. |

[72] |

| Biomarker Use (SLC6A6 Expression) |

Using SLC6A6 expression as a biomarker for prognosis and therapy resistance in leukemia. |

Lack of consensus on high/low expression thresholds; need for clinical validation. |

Early detection of relapse, personalized risk stratification in leukemia patients. |

Could be integrated into clinical decision-making to identify resistant subpopulations in AML, ALL, CLL, and CML. |

[8,73] |

6. Metabolic Reprogramming and Leukemia Dependency on Taurine

6.1. Metabolic Reprogramming in Leukemia

Leukemia, like other cancers, is characterized by profound metabolic rewiring that allows malignant cells to thrive in environments that are typically hostile to normal hematopoiesis. Blasts and leukemic stem cells (LSCs) adapt to conditions of hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and oxidative stress by remodeling their use of energy substrates and protective metabolites. Traditional studies have emphasized glycolysis, glutamine metabolism, and lipid remodeling as central to leukemic survival [

74]. However, accumulating evidence indicates that taurine is also integrated into this reprogrammed metabolic framework.

Unlike glucose or glutamine, taurine does not directly supply carbon or nitrogen for biomass synthesis. Instead, taurine functions primarily as a regulatory and stabilizing molecule, buffering redox stress, maintaining osmotic balance, and supporting mitochondrial function. This makes it distinct among metabolites, as its contribution lies less in fueling proliferation and more in enabling leukemic cells to withstand the biochemical challenges of their environment. The reliance on taurine is especially evident in populations that face extreme stress — such as chemotherapy-exposed blasts or quiescent LSCs — where taurine uptake becomes a determinant of survival.

6.2. Taurine and Redox Balance

One of the best-documented roles of taurine in leukemia is its contribution to redox regulation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) occupy a paradoxical position in leukemogenesis: moderate levels promote proliferative signaling and genetic instability, while excessive accumulation is cytotoxic [

75]. Many chemotherapeutic agents, including cytarabine and anthracyclines, exploit this by generating lethal ROS levels. Yet leukemic cells frequently adapt, and taurine uptake through SLC6A6 is part of this adaptation.

Taurine neutralizes ROS both directly and indirectly. It reacts with hypochlorous acid, a potent oxidant generated by myeloperoxidase activity, to form taurine chloramine, a less toxic and more immunomodulatory compound[

76]. It also stabilizes mitochondrial membranes, preventing ROS-induced permeability transition and the cascade of cytochrome c release and caspase activation. By these means, taurine reduces the cytotoxic potential of chemotherapy-induced oxidative stress.

This buffering effect has been observed across subtypes. In AML, taurine supplementation diminishes apoptosis after chemotherapy exposure, while TauT knockdown restores sensitivity to oxidative killing [

77]. In CLL, where malignant B cells experience high baseline oxidative stress due to chronic BCR signaling, TauT upregulation correlates with prolonged survival[

61]. Even in CML, taurine appears to support quiescent stem cells in hypoxic niches, enabling them to resist oxidative damage despite tyrosine kinase inhibition. Thus, the taurine–TauT axis functions as a redox safety net, allowing leukemia to harness ROS for signaling without succumbing to its lethal effects.

6.3. Mitochondrial Dependency

Mitochondria are increasingly recognized as central to the persistence of leukemia, particularly in stem-like populations that resist therapy [

78]. In AML, LSCs depend heavily on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and therapies such as venetoclax exploit this dependency. Taurine directly supports mitochondrial function by modifying uridine residues in mitochondrial tRNAs, an essential step in the synthesis of respiratory chain proteins. Deficiency in these modifications leads to defective electron transport and energy collapse, highlighting taurine’s unique role as a mitochondrial cofactor [

79].

Beyond translation, taurine stabilizes mitochondrial membranes, reducing susceptibility to depolarization and apoptosis. This dual role ensuring the integrity of respiratory chain synthesis and protecting against structural collapse gives leukemia cells a survival mechanism under metabolic and therapeutic stress. Resistant AML clones exposed to venetoclax frequently remodel mitochondrial metabolism; taurine-dependent stabilization may be one of the adaptations that allow these clones to escape apoptosis.

The dependence on taurine for mitochondrial stability is not restricted to AML. Evidence from ALL and CLL suggests that taurine helps maintain energy homeostasis in stressed blasts, although the precise molecular mechanisms remain less well defined [

25]. Collectively, taurine contributes to a metabolic phenotype in which mitochondria are preserved as functional powerhouses, even in environments designed to compromise them.

6.4. Microenvironmental Interactions

The bone marrow microenvironment adds another layer of complexity to leukemic metabolism. Here, malignant blasts compete with stromal and immune cells for nutrients while also facing hypoxia and oxidative stress. Taurine provides a distinct survival advantage in this context. By supporting osmotic stability, calcium regulation, and antioxidant defense, taurine allows leukemia cells to continue proliferating in conditions that would otherwise limit growth [

80].

Emerging evidence suggests that stromal cells may contribute taurine to the extracellular milieu, creating a metabolic exchange that supports malignant blasts [

81]. This mirrors the nutrient-sharing phenomena described in solid tumors, where cancer-associated fibroblasts release metabolites such as glutamine or lactate to support tumor growth. In leukemia, the exchange centers on taurine, with blasts acting as the primary beneficiaries. This interaction underscores the point that metabolic dependencies cannot be viewed in isolation from the microenvironment; instead, they reflect a dynamic dialogue between malignant cells and their niche.[

17]

6.5. Integration into the Leukemic Metabolic Landscape

Taurine dependency intersects with other metabolic pathways, reinforcing its role in the broader reprogramming of leukemia. By stabilizing intracellular conditions, taurine permits sustained glycolytic flux without tipping cells into oxidative collapse [

22]. It complements glutamine metabolism by providing an alternative buffer for redox homeostasis when NADPH production is insufficient. It also protects lipids from peroxidation, thereby reducing susceptibility to ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death that is beginning to attract therapeutic attention. These interactions illustrate how taurine functions not in isolation but as part of a layered metabolic strategy, one that enhances redundancy and resilience under diverse stresses.

6.6. Leukemia as a Taurine-Dependent Malignancy

Taken together, these observations suggest that leukemia can be considered a taurine-dependent malignancy. This dependency originates in the intrinsic enrichment of taurine in leukocytes but is amplified by malignant transformation into an essential survival mechanism. Taurine does not fuel biomass synthesis directly, yet its buffering and stabilizing roles are indispensable to blasts and stem-like populations facing therapeutic and environmental stress [

51]. Recognizing taurine as a central enabler of leukemic persistence reframes it as a genuine metabolic vulnerability, one that could be targeted across multiple subtypes irrespective of genetic background.

7. Therapeutic Targeting of the Taurine–TauT Axis

7.1. Rationale for Targeting Taurine Metabolism

The rationale for targeting the taurine–TauT axis in leukemia rests on three pillars. First, taurine uptake is largely mediated by a single high-affinity transporter, SLC6A6. Unlike many metabolic pathways with redundant transporters and enzymes, taurine dependency converges on one molecular gatekeeper, making it an unusually tractable node. Second, taurine functions not as a generic nutrient but as a survival buffer, stabilizing redox balance, mitochondrial integrity, and osmotic homeostasis [

7]. Blocking this safeguard may selectively sensitize malignant cells to stress without crippling normal hematopoiesis. Third, evidence across AML, ALL, CML, and CLL indicates that high TauT expression marks aggressive disease biology and therapy resistance, strengthening its relevance as a therapeutic target.

7.2. Inhibition of SLC6A6 (TauT) as a Direct Strategy

The most straightforward approach is direct inhibition of SLC6A6. Experimental models show that pharmacological blockade or genetic knockdown of TauT reduces taurine uptake, leading to accumulation of oxidative stress and apoptosis in leukemic blasts. In AML, TauT suppression resensitizes resistant cells to cytarabine and doxorubicin, restoring ROS-induced cell death. In LSC-enriched populations, TauT inhibition compromises mitochondrial function, reducing clonogenic potential and stemness [

82]

Despite this promise, translation faces significant barriers. Selective inhibitors of TauT are not yet clinically available. Most current compounds lack specificity and interfere with other SLC6 family members, raising the risk of off-target neurological effects. Development of high-affinity, transporter-specific inhibitors remains a critical unmet need. Advances in structure-guided drug design, facilitated by cryo-EM models of related transporters, may accelerate this effort.

7.3. Sensitization to Chemotherapy

One of the most compelling applications of TauT inhibition is as a chemosensitizer. Standard leukemia therapies, from anthracyclines to venetoclax, rely on oxidative stress and mitochondrial disruption to induce apoptosis. Taurine uptake counteracts both mechanisms, enabling blasts to tolerate drug pressure. By blocking TauT, leukemic cells could be pushed past their tolerance threshold, making existing therapies more effective at lower doses.

Preclinical studies support this synergy. In AML models, TauT knockdown enhances cytarabine cytotoxicity by amplifying ROS accumulation. In CLL, taurine depletion increases sensitivity to BCL2 inhibitors by destabilizing mitochondrial integrity [

83]. Even in CML, where TKIs target BCR–ABL1 signaling, taurine modulation may weaken the stem-cell compartment that sustains relapse [

84]. These findings suggest that TauT-directed strategies are unlikely to work in isolation but may be highly effective in combination regimens.

7.4. Targeting Leukemic Stem Cells (LSCs)

Eradication of LSCs remains one of the greatest obstacles in leukemia therapy. These cells are metabolically flexible, therapy-resistant, and capable of long-term disease relapse. Several lines of evidence suggest that LSCs rely disproportionately on taurine uptake compared with bulk blasts. High SLC6A6 expression has been noted in stem-like fractions of AML, and functional assays confirm reduced colony formation when taurine uptake is suppressed [

85]

This opens the possibility that TauT inhibition could function as an anti-stem cell therapy, selectively weakening the very population responsible for relapse. In the context of venetoclax-based regimens, which already target mitochondrial dependencies of LSCs, TauT blockade may act as a complementary approach, destabilizing mitochondrial function further and enhancing eradication.

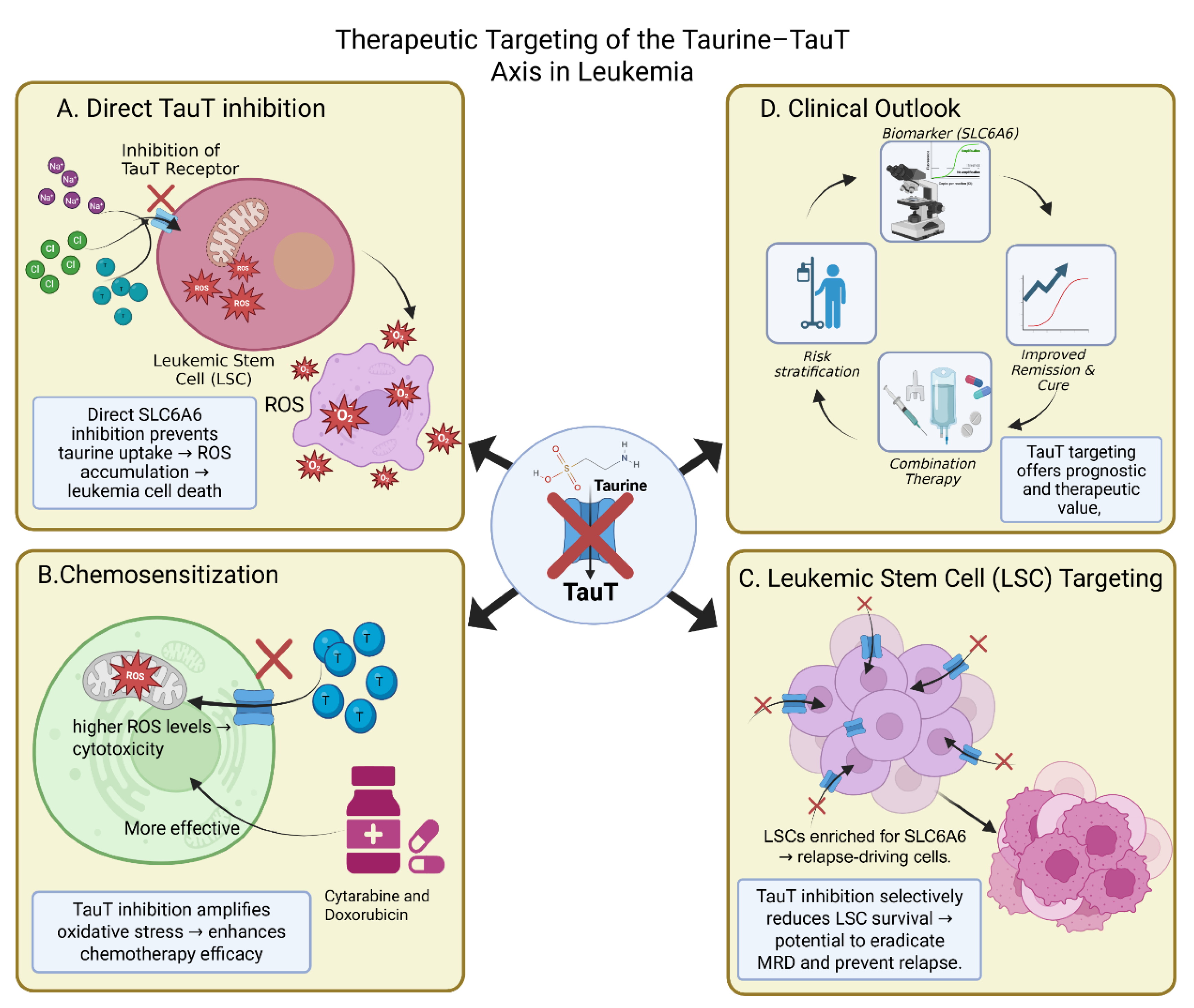

Figure 3.

Therapeutic targeting of the Taurine–TauT axis in leukemia. The schematic illustrates multiple strategies by which inhibition of the taurine transporter (TauT; gene symbol SLC6A6) can be leveraged as a therapeutic avenue in leukemia. (A) Direct TauT inhibition: Blocking TauT function impedes taurine uptake, resulting in reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and subsequent leukemic cell death. (B) Chemosensitization: TauT inhibition amplifies oxidative stress, thereby enhancing the cytotoxic efficacy of standard chemotherapeutic agents such as cytarabine and doxorubicin. (C) Leukemic stem cell (LSC) targeting: Given that LSCs are enriched for SLC6A6 expression and drive relapse, TauT inhibition selectively compromises LSC survival, offering the potential to eradicate minimal residual disease (MRD) and reduce relapse risk. (D) Clinical outlook: Targeting TauT provides prognostic and therapeutic value by serving as a biomarker (e.g., SLC6A6expression), aiding risk stratification, supporting combination therapies, and improving remission and cure rates.

Figure 3.

Therapeutic targeting of the Taurine–TauT axis in leukemia. The schematic illustrates multiple strategies by which inhibition of the taurine transporter (TauT; gene symbol SLC6A6) can be leveraged as a therapeutic avenue in leukemia. (A) Direct TauT inhibition: Blocking TauT function impedes taurine uptake, resulting in reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and subsequent leukemic cell death. (B) Chemosensitization: TauT inhibition amplifies oxidative stress, thereby enhancing the cytotoxic efficacy of standard chemotherapeutic agents such as cytarabine and doxorubicin. (C) Leukemic stem cell (LSC) targeting: Given that LSCs are enriched for SLC6A6 expression and drive relapse, TauT inhibition selectively compromises LSC survival, offering the potential to eradicate minimal residual disease (MRD) and reduce relapse risk. (D) Clinical outlook: Targeting TauT provides prognostic and therapeutic value by serving as a biomarker (e.g., SLC6A6expression), aiding risk stratification, supporting combination therapies, and improving remission and cure rates.

7.5. Dietary and Systemic Modulation of Taurine

Beyond direct inhibition, systemic manipulation of taurine levels has been proposed. Taurine supplementation has been explored clinically for reducing chemotherapy toxicity in other cancers, due to its protective effects on normal tissues such as the heart and liver. However, in leukemia, supplementation could paradoxically protect malignant cells as well. Conversely, dietary taurine restriction may theoretically reduce leukemic survival, though systemic depletion is challenging given endogenous biosynthesis and widespread physiological roles. At present, dietary approaches remain speculative and are unlikely to achieve the precision needed for therapeutic impact[

86]

7.6. Challenges and Future Directions

Several challenges must be addressed before taurine metabolism can be translated into a therapeutic target. First, selective pharmacological tools for TauT are lacking, and their development will be essential. Second, it remains to be determined how much normal hematopoiesis depends on taurine compared with leukemia. While leukocytes are naturally taurine-rich, malignant blasts may have exaggerated dependence, offering a potential therapeutic window. Third, comprehensive clinical data linking SLC6A6 expression with treatment outcomes are still limited, and large-scale correlative studies are needed [

87].

Despite these uncertainties, the taurine–TauT axis represents an unusually clear metabolic vulnerability. By combining direct transporter inhibition with conventional therapies, or by integrating it into regimens that target leukemic stem cells, it may be possible to exploit this dependency to achieve deeper and more durable remissions.

8. Clinical Implications and Translational Outlook

8.1. Prognostic Significance of SLC6A6 Expression

Emerging data suggest that SLC6A6 expression may serve as a biomarker of prognosis in leukemia. In AML, higher TauT levels have been detected in patients with adverse-risk cytogenetics such as TP53 mutations, FLT3-ITD, and complex karyotypes. These associations point to a link between taurine metabolism and aggressive disease biology. Similarly, in CLL, elevated SLC6A6 distinguishes leukemic B cells from their normal counterparts and aligns with poor-risk features, including resistance to BTK and BCL2 inhibitors [

88]. Although large-scale, prospective studies are lacking, the convergence of transcriptomic and functional evidence suggests that SLC6A6 could eventually be incorporated into risk stratification models.

8.2. Implications for Therapy Resistance and Relapse

One of the most important clinical consequences of taurine–TauT activity is its role in therapy resistance. By buffering oxidative stress and stabilizing mitochondria, taurine uptake allows blasts and leukemic stem cells to survive cytotoxic stress. This mechanism helps explain why residual disease persists after chemotherapy and why LSCs escape eradication by venetoclax or TKIs. Clinically, this implies that patients with high SLC6A6 expression may be more prone to relapse, even if they initially respond to therapy. Identifying these patients early could allow more intensive monitoring or tailored combination regimens that specifically target metabolic resilience.

8.3. Integration with Existing Therapies

The translational potential of targeting TauT lies not in replacing current therapies but in enhancing them. Conventional chemotherapies, BCL2 inhibitors, and TKIs all rely, at least in part, on mitochondrial disruption and oxidative stress. By blocking taurine uptake, it may be possible to lower the threshold for cell death, amplifying the efficacy of existing drugs. This approach could enable dose reduction of toxic agents while maintaining therapeutic potency, thereby improving tolerability in older or frail patients. Preclinical models of AML and CLL already support this synergy, and clinical trials could extend it to broader settings.

8.4. Implications for Leukemic Stem Cell Eradication

Perhaps the most significant translational impact lies in the potential to

target leukemic stem cells. Current therapies often induce remission but fail to eradicate LSCs, which seed relapse. Evidence that LSC-enriched populations express higher SLC6A6 suggests that TauT inhibition could directly impair their survival[

89]. This would represent a major advance in leukemia therapy, shifting treatment from short-term cytoreduction toward long-term disease eradication. Clinically, such an approach could improve cure rates, reduce relapse risk, and potentially allow discontinuation of chronic therapies such as TKIs.

8.5. Opportunities and Limitations in Clinical Translation

Despite its promise, clinical translation of taurine-targeted strategies faces challenges. Selective TauT inhibitors are not yet available, and systemic taurine depletion is unlikely to be feasible given its physiological importance in heart, muscle, and brain. Moreover, normal leukocytes also rely on taurine, raising concerns about hematologic toxicity. The critical question is whether malignant cells are more dependent on taurine than their normal counterparts, creating a therapeutic window. Early data suggest they may be, but definitive proof will require carefully designed translational studies.

At the same time, there are opportunities. Advances in precision oncology increasingly integrate transcriptomic and metabolic profiling, making it possible to identify patients whose leukemias are most dependent on taurine. Combination strategies may also allow selective targeting: for example, pairing TauT inhibition with chemotherapy could exploit the fact that blasts under oxidative stress are more reliant on taurine than resting immune cells. Such strategies would require careful balancing of efficacy and toxicity but are conceptually within reach.

Table 4.

Candidate Biomarkers for Patient Selection and Monitoring.

Table 4.

Candidate Biomarkers for Patient Selection and Monitoring.

| Biomarker |

Leukemia Subtype |

Mechanistic Role |

Clinical Relevance |

Potential Use in Patient Monitoring |

References |

| SLC6A6 (TauT) |

AML, ALL, CML, CLL |

Taurine transporter that regulates oxidative stress and mitochondrial stability |

Upregulated in leukemic cells, particularly in relapse and resistant clones. High expression correlates with poor prognosis and chemoresistance. |

Predicts relapse risk; potential for therapeutic targeting (TauT inhibition) to sensitize to chemotherapy. |

[8] |

| Plasma Taurine Levels |

CLL, AML, ALL |

Reflects systemic taurine turnover and tumor metabolism |

Elevated taurine levels correlate with increased disease burden and therapy resistance, particularly in CLL. |

Used as a metabolomic biomarker to monitor disease progression and therapy resistance. |

[90] |

| FLT3-ITD Mutations |

AML |

Activates multiple pro-survival pathways, contributing to chemoresistance and LSC persistence |

Strongly associated with poor prognosis, high relapse rates, and resistance to conventional therapies. |

Prognostic biomarker; used to identify patients who may benefit from targeted FLT3 inhibitors. |

[91] |

| TP53 Mutations |

AML, CML, ALL |

Disrupts DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation |

Associated with adverse prognosis and treatment resistance. TP53 mutations lead to LSC survival and relapse. |

Prognostic marker to identify high-risk patients and determine the need for intensified therapy. |

[92] |

| BCR-ABL1 Fusion Protein |

CML |

Hallmark of CML, driving leukemogenesis via BCR–ABL1 signaling |

Presence of BCR-ABL1 is central to CML diagnosis and targeted therapy with TKIs (imatinib). |

Monitored for minimal residual disease (MRD) detection and assessing TKI therapy effectiveness. |

[93] |

| BTK Inhibitors Resistance (e.g., Ibrutinib) |

CLL |

Aberrant BCR signaling and immune evasion |

Resistance to BTK inhibitors (e.g., ibrutinib) indicates failure of current therapy and need for alternative strategies. |

Marker of resistance in CLL patients; indicates the potential use of second-line therapies or TauT inhibitors |

[94] |

9. Future Directions

9.1. Development of Selective TauT Inhibitors

One of the most immediate priorities is the creation of highly selective pharmacological inhibitors of SLC6A6. Current experimental compounds lack specificity and affect other SLC6 family members, raising the risk of neurological and cardiovascular side effects. Advances in cryo-electron microscopy of related transporters now make structure-guided drug design feasible, offering a path to identify small molecules or biologics that target TauT with high affinity. Such inhibitors would allow rigorous preclinical testing and, eventually, clinical translation.

9.2. Clinical Validation of SLC6A6 as a Biomarker

Although transcriptomic analyses suggest correlations between high SLC6A6 expression and poor prognosis in AML and CLL, these findings remain largely exploratory. Prospective studies across large, well-annotated patient cohorts are needed to determine whether TauT levels can serve as independent prognostic markers. Integration into risk stratification models could help identify patients who are more likely to relapse, and who may benefit most from therapies targeting taurine metabolism. Future studies should test TauT inhibition in combination with existing standards of care. In AML, this means pairing with cytarabine or venetoclax; in CLL, combining with BTK or BCL2 inhibitors; and in CML, exploring synergy with TKIs. Preclinical work already points to enhanced chemosensitivity when taurine uptake is suppressed, but systematic studies in patient-derived xenograft models and ex vivo primary samples are required to confirm this synergy and assess toxicity.

9.3. Targeting Leukemic Stem Cells

The persistence of leukemic stem cells remains the greatest barrier to cure. Evidence that LSC-enriched populations express higher SLC6A6 suggests that TauT inhibition could directly impair their survival. Future research should focus on dissecting how taurine uptake supports stemness programs at the molecular level — whether through mitochondrial translation, redox buffering, or signaling pathways — and how this can be best exploited therapeutically. To fully appreciate taurine’s role in leukemia, a systems-level approach is required. Integrating transcriptomic, metabolomic, and single-cell analyses will help map taurine dependencies across subtypes, disease stages, and treatment responses. Such profiling could also reveal whether systemic taurine availability, influenced by diet or liver function, modifies leukemia progression. These insights would inform both patient stratification and therapeutic timing.

9.4. Broadening the Scope Beyond Leukemia

While this review focuses on leukemia, it is possible that taurine metabolism plays comparable roles in other hematologic and solid malignancies. Investigating TauT expression and taurine dependency across cancers may uncover common vulnerabilities and allow the design of broader therapeutic strategies. This comparative perspective could also clarify whether leukemia is uniquely dependent on taurine, or whether this reflects a generalizable cancer biology principle.

10. Conclusions

Taurine, long regarded as a conditionally essential amino acid with supportive physiological roles, has emerged as a central player in the survival of leukemic cells. Through its dedicated transporter SLC6A6, taurine provides more than osmotic stability — it buffers oxidative stress, preserves mitochondrial function, and enables blasts and stem-like populations to withstand therapeutic and environmental pressure. Unlike many metabolic pathways with built-in redundancies, taurine uptake converges on a single high-affinity transporter, making TauT both a gatekeeper and a potential therapeutic target.

The clinical implications are profound. High SLC6A6 expression aligns with aggressive disease biology and therapy resistance across leukemia subtypes. By supporting leukemic stem cell persistence, taurine metabolism contributes directly to relapse, the greatest barrier to cure. These insights place the taurine–TauT axis alongside glycolysis and glutamine metabolism as a defining feature of leukemic reprogramming.

Future progress will depend on the development of selective TauT inhibitors, systematic clinical validation of taurine dependency, and integration of transporter targeting into combination regimens. If these hurdles can be overcome, disrupting taurine metabolism may allow existing therapies to achieve deeper remissions and potentially eradicate the stem-cell reservoir. In this sense, taurine is no longer a peripheral metabolite but a critical vulnerability that could reshape the therapeutic landscape of leukemia.

Author Contributions

Anshu Rao: Writing Original Draft, Writing Review & Editing, Visualization; Bishal Patgiri: Visualization; Jitendra Kumar: Writing Review & Editing; Uddalak Das: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Review & Editing. All authors critically revised the paper and approved the final version.

Funding

The author(s) acknowledge the funds received by Uddalak Das from the Department of Biotechnology (Grant No: DBTHRDPMU/JRF/BET-24/I/2024-25/376), the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (Grant No: 24J/01/00130), and the Indian Council of Medical Research (Grant No: 3/1/3/BRET-2024/HRD (L1)).

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The writing of this review paper involved the use of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies only to enhance the clarity, coherence, and overall quality of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the contributions of AI in the writing process while ensuring that the final content reflects the author's own insights and interpretations of the literature. All interpretations and conclusions drawn in this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the author.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author(s) report no conflict of interest.

References

- Nemkov, T.; D’Alessandro, A.; Reisz, J.A. Metabolic underpinnings of leukemia pathology and treatment. Cancer Rep. Hoboken NJ 2019, 2, e1139. [CrossRef]

- Poudel, G.; Tolland, M.G.; Hughes, T.P.; Pagani, I.S. Mechanisms of Resistance and Implications for Treatment Strategies in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia. Cancers 2022, 14, 3300. [CrossRef]

- Das, U. Emerging trends and research landscape of the tumor microenvironment in head-and-neck cancer: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Cancer Plus 2025, 0, 025060008. [CrossRef]

- Rashkovan, M.; Ferrando, A. Metabolic dependencies and vulnerabilities in leukemia. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 1460–1474. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jin, J.; Chang, R.; Yang, X.; Li, N.; Zhu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, Y. Targeting the sulfur-containing amino acid pathway in leukemia. Amino Acids 2024, 56, 47. [CrossRef]

- Ripps, H.; Shen, W. Review: taurine: a “very essential” amino acid. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 2673–2686.

- Du, B.; Cheng, L.; Xie, J.; Chen, L.; Yan, K. Molecular basis of human taurine transporter uptake and inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7394. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Shu, H.; Xu, M.; Ke, W.; Chen, W.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y. Association between taurine transporter SLC6A6 and breast cancer development and prognosis: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1414. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yu, Y.; Cao, C. The dual role of taurine in cancer and immune metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, S1043276025001705. [CrossRef]

- Das, U.; Banerjee, S.; Sarkar, M. Bibliometric analysis of circular RNA cancer vaccines and their emerging impact. Vacunas 2025, 500391. [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Chen, W.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Sun, X.; Luo, Y.; Shi, J.; Shao, K.; et al. The Global Burden of Leukemia and Its Attributable Factors in 204 Countries and Territories: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study and Projections to 2030. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 1612702. [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Mamo, W.; Moges, A.; Yesuf, S.A.; Mohamedsaid, A.; Arega, G. Treatment outcomes of pediatrics acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and associated factors in the country’s tertiary referral hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 640. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, G.; Cai, X.; Liu, Y.; Qian, B.; Li, D. Global, regional, and national burden of acute myeloid leukemia, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 101. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahayri, Z.N.; AlAhmad, M.M.; Ali, B.R. Long-Term Effects of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Chemotherapy: Can Recent Findings Inform Old Strategies? Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 710163. [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese, A.; Vigna, E.; Martino, E.A.; Amodio, N.; Labanca, C.; Mendicino, F.; Lucia, E.; Olivito, V.; Morabito, F.; Gentile, M. Treatment-Free Remission in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Revisiting the “W” Questions. Eur. J. Haematol. 2025, 115, 218–231. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Rodems, B.J.; Baker, C.D.; Kaszuba, C.M.; Franco, E.I.; Smith, B.R.; Ito, T.; Swovick, K.; Welle, K.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Taurine from tumour niche drives glycolysis to promote leukaemogenesis. Nature 2025, 644, 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, G. From Chemotherapy to Targeted Therapy: Unraveling Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Through Genetic and Non-Genetic Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4005. [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Ma, W.; Zhang, C.; Ge, M.; Tian, M.; Yu, J.; Jiao, A.; et al. Cancer SLC6A6-mediated taurine uptake transactivates immune checkpoint genes and induces exhaustion in CD8+ T cells. Cell 2024, 187, 2288-2304.e27. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A.; Ahmad, K.; Khan, M.S.A.; Bhat, M.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Rahman, S.; Jan, A.T. Expedition into Taurine Biology: Structural Insights and Therapeutic Perspective of Taurine in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 863. [CrossRef]

- Seneff, S.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M. Taurine prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and protects mitochondria from reactive oxygen species and deuterium toxicity. Amino Acids 2025, 57, 6. [CrossRef]

- Baliou S, Adamaki M, Ioannou P, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Spandidos DA, Christodoulou I, Kyriakopoulos AM, Zoumpourlis V. Protective role of taurine against oxidative stress (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2021 Aug;24(2):605.

- de Beauchamp, L.; Himonas, E.; Helgason, G.V. Mitochondrial metabolism as a potential therapeutic target in myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Sciaccotta, R.; Gangemi, S.; Penna, G.; Giordano, L.; Pioggia, G.; Allegra, A. Potential New Therapies “ROS-Based” in CLL: An Innovative Paradigm in the Induction of Tumor Cell Apoptosis. Antioxid. Basel Switz. 2024, 13, 475. [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, S.; Kim, H.W. Effects and Mechanisms of Taurine as a Therapeutic Agent. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 225–241. [CrossRef]

- Vitvitsky, V.; Garg, S.K.; Banerjee, R. Taurine biosynthesis by neurons and astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 32002–32010. [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Yue, M.; Chandra, D.; Keramidas, A.; Goldstein, P.A.; Homanics, G.E.; Harrison, N.L. Taurine is a potent activator of extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors in the thalamus. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 106–115. [CrossRef]

- Hardison, W.G. Hepatic taurine concentration and dietary taurine as regulators of bile acid conjugation with taurine. Gastroenterology 1978, 75, 71–75.

- Kubo, Y.; Ishizuka, S.; Ito, T.; Yoneyama, D.; Akanuma, S.-I.; Hosoya, K.-I. Involvement of TauT/SLC6A6 in Taurine Transport at the Blood-Testis Barrier. Metabolites 2022, 12, 66. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, I.H. Regulation of the cellular content of the organic osmolyte taurine in mammalian cells. Neurochem. Res. 2004, 29, 27–63. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, H.-U.; Lee, H.-N.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, C.; Cha, Y.-N.; Joe, Y.; Chung, H.T.; Jang, J.; Kim, K.; et al. Taurine Chloramine Stimulates Efferocytosis Through Upregulation of Nrf2-Mediated Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression in Murine Macrophages: Possible Involvement of Carbon Monoxide. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 163–177. [CrossRef]

- Jong, C.J.; Sandal, P.; Schaffer, S.W. The Role of Taurine in Mitochondria Health: More Than Just an Antioxidant. Mol. Basel Switz. 2021, 26, 4913. [CrossRef]