1. Introduction

Accurately distinguishing Ménière’s disease (MD) from vestibular migraine (VM) remains, at times, one of the most demanding problems in contemporary neurotology (1). Both disorders present with recurrent vertigo, yet they diverge in pathophysiology, prognosis, and treatment, so misclassification may lead to inappropriate management, delayed interventions, and worse outcomes (2). Despite decades of research, reliable biomarkers that consistently separate MD from VM have proven elusive, although important advances have emerged in recent years (3). Current diagnostic frameworks rely predominantly on clinical symptom profiles defined by the Bárány Society (4) and the International Headache Society (5), which are purely clinical classifications grounded in symptomatology and episode characteristics; given the overlap between syndromes, diagnostic ambiguity is frequent (6).

Current diagnostic frameworks for Ménière’s disease, including the 1995 Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines (7) and the 2020 AAO-HNSF Clinical Practice Guideline (8), emphasize pure-tone thresholds (0.5–3 kHz) and recommend concurrent assessment of speech recognition. However, the operational classification of hearing change and “usable hearing” remains primarily anchored in pure-tone averages, with speech discrimination used as a secondary modifier. Audiometry thus remains central to MD diagnosis together with symptomatology. In particular, pure-tone thresholds obtained during or shortly after attacks provide objective evidence of fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss, a defining feature of MD. This study extends that framework by formally integrating speech discrimination performance into the audiometric evaluation. By analyzing the relationship between PTA and SDS (through both correlation and derived indices such as the SDS/PTA ratio) the model captures functional hearing performance beyond sensitivity alone, potentially reflecting the degree of cochlear distortion characteristic of endolymphatic hydrops.

Recognition of the limitations of purely clinical definitions has also driven interest in objective physiological markers—beyond MRI—including advanced vestibular function tests (9) and emerging blood-based biomarkers (10). By contrast, alternative MD classifications have integrated objective vestibular testing and hydrops MRI alongside clinical criteria, incorporating immediate nystagmus recording during attacks and gadolinium-enhanced MRI to visualize endolymphatic hydrops (11). Early predictive models have been informative yet limited: a logistic approach suggested value in electrocochleography, head-shaking, ocular VEMPs, and horizontal-canal vHIT (12); the Base-ML initiative tested multiple algorithms on registry data but achieved only 25.9–50.4% accuracies, underscoring the complexity of automated classification in this domain (13).

Among candidate physiologic markers, the dissociation between caloric and vHIT responses (abnormal calorics with preserved horizontal vHIT) has emerged as a reproducible MD signature (14,15), with large-scale studies supporting its specificity against VM and other vestibular disorders (16). In this work, we refer to this dissociation as CalHiT-A (caloric–vHIT dissociation, pattern A). Notably, such caloric–vHIT dissociation has not been systematically integrated with speech measures and otolithic variables within a unified, leakage-controlled modeling framework.

Aligned with contemporary diagnostic frameworks (8, 17), we designed a PTA-free analysis to minimize incorporation bias. Our primary focus was on bilateral speech discrimination scores (SDS, per ear), which capture functional hearing beyond pure-tone averages. We then asked whether vestibular physiology, prespecified as CalHiT-A, adds diagnostic information over SDS alone. Accordingly, our objectives were:

Primary objective: quantify the diagnostic performance of an SDS-only model (bilateral SDS per ear) for discriminating MD from VM using patient-level, out-of-fold cross-validation.

Secondary objective: assess the incremental value of CalHiT-A over SDS by changes in ROC–AUC, and compare calibration and decision-curve net benefit; additionally, describe the prevalence of CalHiT-A by diagnostic group.

Exploratory objective (pre-specified): compare ear-wise SDS to an “affected/healthy” SDS encoding and confirm that it does not outperform the bilateral specification.

All modeling used logistic regression with in-fold preprocessing; calibration and decision-curve analyses are summarized in the Supplement.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This was a cross-sectional, retrospective study including 60 patients with definite Ménière’s disease (MD) according to the 2015 Bárány Society criteria (4) and 40 patients with definite vestibular migraine (VM) according to the Bárány Society/ICHD consensus (5). MD patients contributed both the affected and contralateral ears (120 ears total), while VM patients contributed both ears (80 ears total). The analysis used data from the index visit (2015–2018) only; subsequent visits were not used to compute predictors or outcomes.

Diagnostic stability was verified over 6–7 years using in-person clinic assessments whenever possible, with structured telephone interviews used only to supplement missing recent visits. No MD case progressed to bilateral involvement (18), and no VM case required diagnostic reclassification. This approach aligns with Bárány recommendations underscoring the role of longitudinal assessment to secure diagnostic accuracy in MD and VM. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective design, informed consent was waived.

2.2. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Clinical Variables

All participants completed validated Spanish instruments at the index visit: the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) (19); the Vertigo Symptom Scale (severity and anxiety subscales) (20); in addition, patients completed the Cuestionario de Impacto Emocional del Vértigo (CIEV; Emotional Impact of Vertigo Questionnaire), originally developed and validated in Spanish (21). We also recorded clinical features (auditory fluctuation, tinnitus, aural fullness, phonophobia, vascular triggers), disease duration (years), days since the last limiting vestibular event, and number of attacks in the preceding 12 months. A full otologic examination and a structured bedside vestibular evaluation (ocular motility, spontaneous nystagmus, post–head-shake nystagmus, positional testing) were performed. Ancillary evaluations (neurology, hydrops MRI) supported exclusion of alternative diagnoses and consolidation of MD or VM diagnoses as definite when needed.

These variables were used to characterize the cohort and for sensitivity/descriptive analyses; none were used as predictors in the primary models.

2.3. Audiologic Assessment

Pure-tone audiometry. Air- and bone-conduction thresholds were measured from 250 to 6000 Hz under standard clinical conditions. The conventional PTA was the mean at 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 kHz in line with AAO-HNS guidance (7); a high-frequency PTA (2–6 kHz) was also computed (8).

Speech audiometry (SDS and SDS/PTA). Speech reception threshold (SRT) was the level (dB HL) yielding 50% correct for disyllabic words. Speech discrimination score (SDS) was obtained monaurally at a fixed presentation of 65 dB HL, using recorded, phonetically balanced disyllabic Spanish lists (Cárdenas-Marrero). Testing was performed in a sound-treated booth with calibrated transducers (insert or supra-aural as per clinic standards); 25 words/ear were presented once (no item repetition), and percent correct per ear was recorded. Masking with speech-spectrum noise was used when indicated by standard interaural-attenuation rules (22). To quantify speech efficiency relative to tone loss, we computed SDS/PTA per ear as SDS (%)/PTA (dB HL, 0.5–3 kHz). This ratio operationalizes the classic observation that disproportionately reduced SDS relative to PTA suggests pathology beyond “amount of loss” and has long been used in diagnostic audiology (23). Rationale for 65 dB HL: a fixed monaural level maximizes comparability across visits and aligns with conversational levels. If sensation level at 65 dB HL was low (e.g., SRT > 35 dB HL) or approached UCL, the presentation level was adjusted to SRT+35 dB HL or MCL, and the exact level was documented.

2.4. Vestibular Assessment

Calorics. Bithermal water irrigations (30 °C / 44 °C) were performed, and the induced nystagmus was recorded using videonystagmography (VNG; ICS Natus, Middleton, WI, USA). Canal paresis (CP) was calculated according to Jongkees’ formula, with CP ≥ 22% considered abnormal.

Video head impulse test (vHIT). Horizontal and vertical semicircular canal VOR were measured by video-oculography (ICS Natus). Normal horizontal-canal gain was defined as ≥ 0.80; vertical ≥ 0.70.

VEMPs. cVEMP: sternocleidomastoid recordings using acoustic clicks and 100-Hz vibratory stimuli (Interacoustics, Middelfart, Denmark); P13/N23 latencies and amplitudes analyzed (24). oVEMP: extraocular recordings to vibratory stimuli on the same platform; N10/P15 latencies and amplitudes analyzed (24).

Caloric–vHIT pattern taxonomy (CalHiT). We classified patient-level caloric–vHIT patterns using a simple 4-cell scheme (

Table 1); the primary dissociation of interest is CalHiT-A. For the primary analyses, we encoded CalHiT-A (Yes/No) as the vestibular predictor (i.e., abnormal calorics with preserved horizontal vHIT in either ear). Other patterns were used for descriptive context and sensitivity checks.

2.5. Outcome, Data Structure, and Leakage Control

The outcome was diagnosis (MD=positive class; VM=negative class) at the patient level. To avoid leakage from side assignment, we did not use “affected ear” as a predictor; instead, ear-wise measurements entered the models as bilateral features (e.g., SDS-right, SDS-left). Pure-tone thresholds (PTA) were excluded from all models to minimize incorporation bias.

2.6. Feature Sets (Pre-Specified)

Primary (SDS-only): continuous SDS-right and SDS-left.

Secondary (CalHiT-A-only): Yes/No indicating CalHiT-A as defined above; if either component (calorics or vHIT) was missing, a Missing level was retained for descriptive reporting and sensitivity analyses (not treated as positive).

Tertiary (SDS + CalHiT-A): SDS-only with CalHiT-A added to assess incremental value.

Exploratory (ear-assignment check): affected/healthy SDS recoding where available, compared against the bilateral ear-wise specification.

Other available vestibular variables (e.g., CP% magnitude, per-ear vHIT gains) were summarized descriptively by diagnosis but not entered into the primary models.

Group comparisons. Demographic/clinical variables were compared between MD and VM: categorical variables by chi-squared test, continuous variables (non-normal distributions) by Mann–Whitney U. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Preprocessing, modeling, and validation. All preprocessing occurred within each training fold to prevent information leakage. Numeric features (SDS) used median imputation and z-standardization. Categorical features (CalHiT-A) used most-frequent imputation and one-hot encoding with unknown-level handling. The primary learner was logistic regression (liblinear, max_iter = 2000). Validation used 5-fold stratified out-of-fold (OOF) cross-validation at the patient level; OOF probabilities were aggregated for evaluation. Robustness checks repeated key analyses after: (i) forcing CalHiT-A levels to Yes/No (excluding Missing from modeling), and (ii) confirming that affected/healthy SDS encoding did not outperform the bilateral SDS specification.

Performance metrics and statistical analysis. Discrimination was assessed by ROC-AUC with bootstrap 95% CIs (1,000 resamples). Calibration (slope, intercept, Brier score) and Decision-Curve Analysis (DCA) were computed on OOF predictions and are summarized in the Supplement. Threshold-based metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV) are reported at p=0.50 and Youden’s J in the Supplement. Counts of CalHiT-A (Yes/No) by diagnostic group and the Fisher exact p-value are provided in Results.

Software. All analyses were conducted in Python with scikit-learn, following the pipeline above (in-fold preprocessing; OOF evaluation; bootstrap CIs) (25).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 100 patients were included: 60 with definite MD (120 ears) and 40 with definite VM (80 ears). Sex distribution differed significantly: VM showed a marked female predominance (87.5%) versus MD (55%, p < 0.001). Mean age did not differ (MD: 52.3 ± 12.1 years; VM: 48.7 ± 11.8 years; p = 0.15).

Table 2 summarizes demographics, clinical features, and patient-reported outcomes; questionnaires indicated high disease activity at specialty referral.

3.2. Audiometric Findings

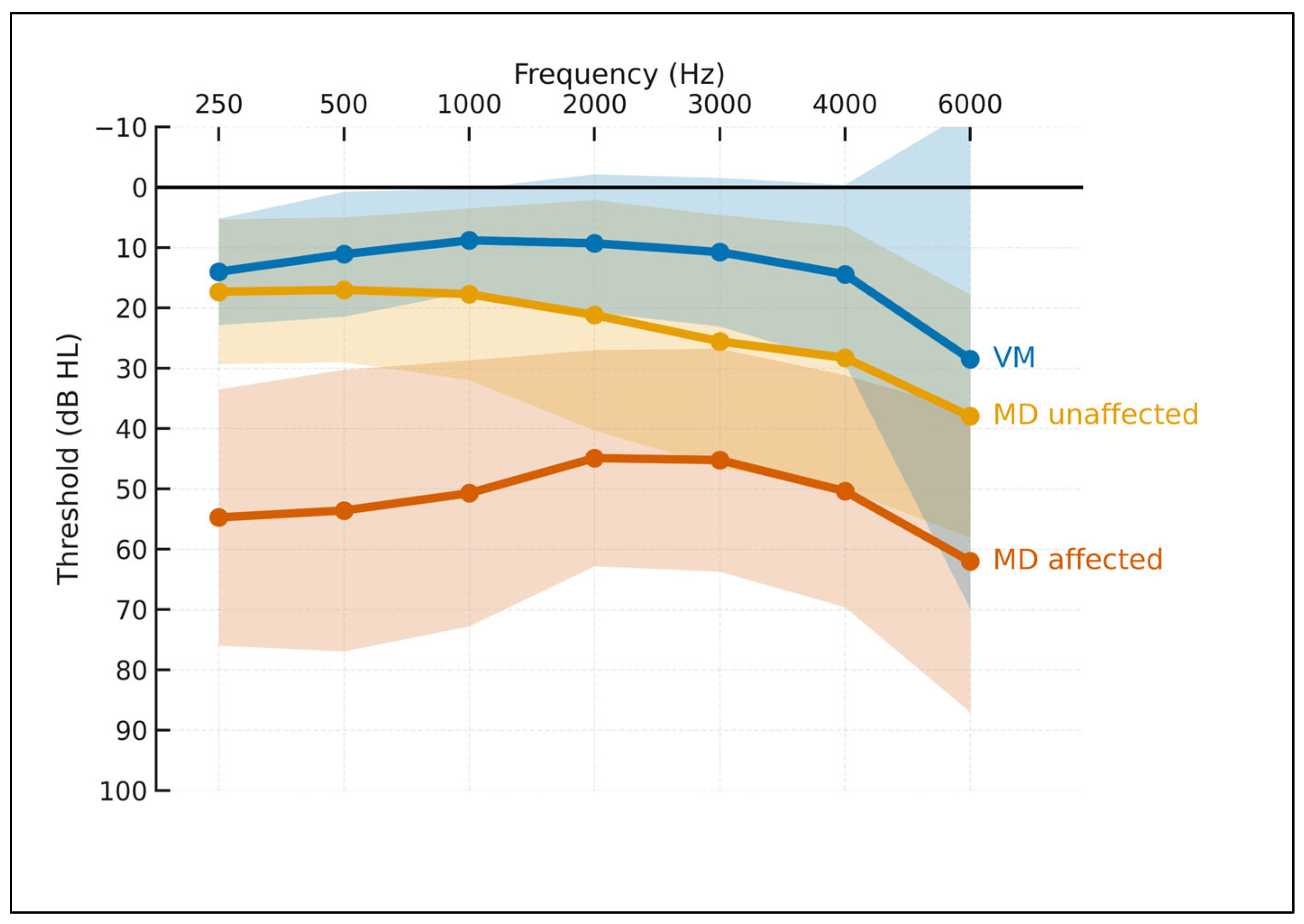

Across 250–6000 Hz (

Figure 1), MD-affected ears showed the highest thresholds with the typical low- to mid-frequency predominance; VM ears remained near normal across most frequencies; MD-unaffected ears were intermediate (largely normal at low frequencies with a mild high-frequency slope). These gradients were consistent across frequencies and mirrored bar-plot contrasts at 250 Hz, PTA 0.5–3 kHz, and PTA 2–4 kHz.

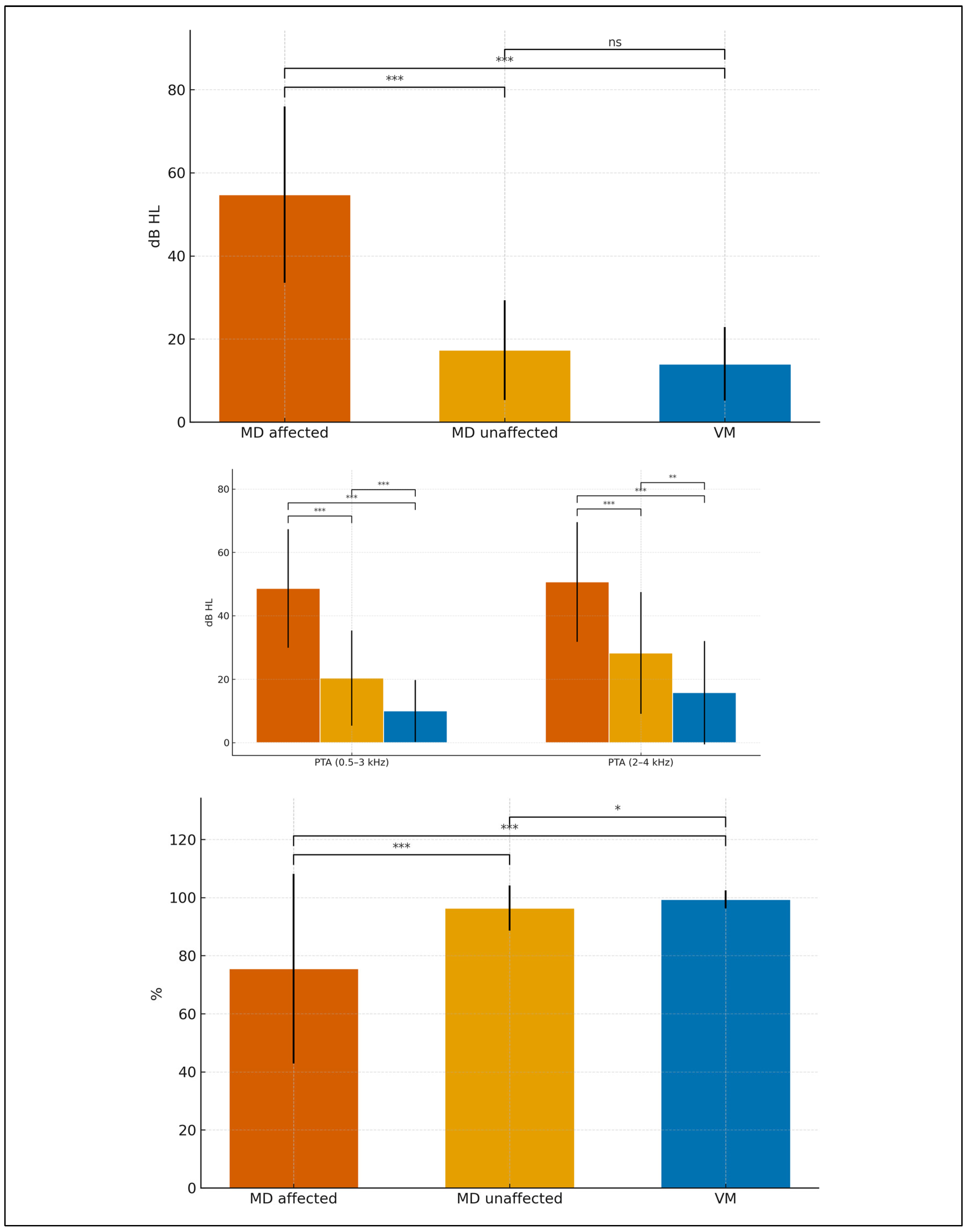

Considering all three groups (MD-affected, MD-unaffected, VM),

Figure 2 shows that at 250 Hz thresholds were highest in MD-affected, intermediate in MD-unaffected, and lowest in VM; the same gradient held for PTA 0.5–3 kHz and PTA 2–4 kHz. Speech discrimination (SDS, %; 65 dB HL) was lowest in MD-affected, intermediate-to-high in MD-unaffected, and near ceiling in VM. Pairwise, permutation-based tests with Bonferroni correction (

Table 3) indicated:

MD-affected vs VM: consistently large differences at 250 Hz, PTA 0.5–3 kHz, PTA 2–4 kHz, and SDS (all p_adj < 0.001).

MD-affected vs MD-unaffected: higher thresholds across tones and lower SDS in MD-affected (all p_adj < 0.001).

MD-unaffected vs VM: higher thresholds and lower SDS in MD-unaffected; differences remained significant after multiplicity control.

These findings support a graded audiometric profile (VM ≈ near-normal, MD-unaffected intermediate, MD-affected worst) mirrored by SDS, jointly providing robust separation across groups.

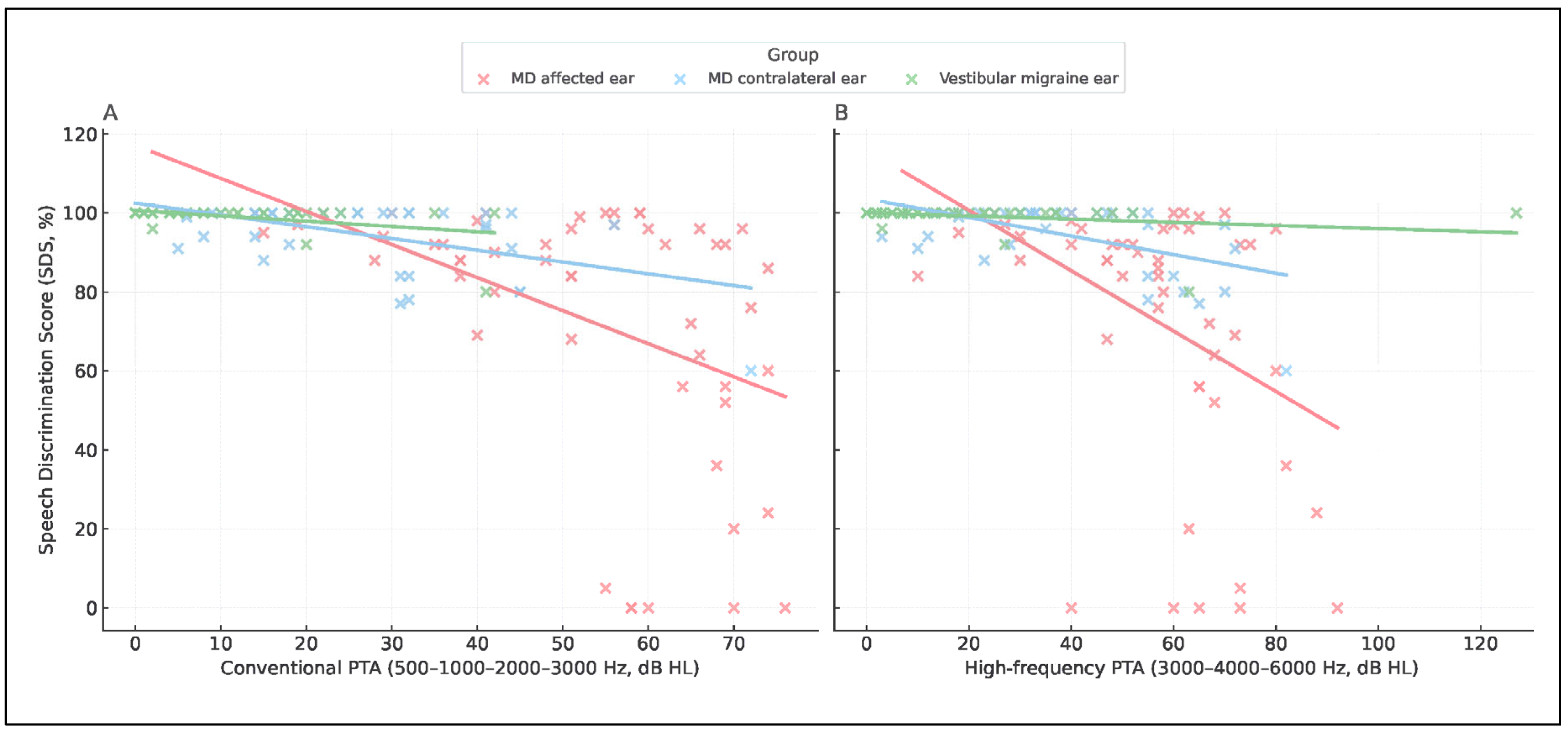

The relationship between speech discrimination (SDS) and tonal thresholds (PTA, 0.5–3 kHz) revealed a consistent inverse trend across diagnostic groups. Higher PTA values were associated with lower SDS, but the slope of this relationship differed markedly as it was steeper in MD-affected ears and shallower in vestibular migraine, indicating group-specific patterns of auditory distortion (

Figure 4,

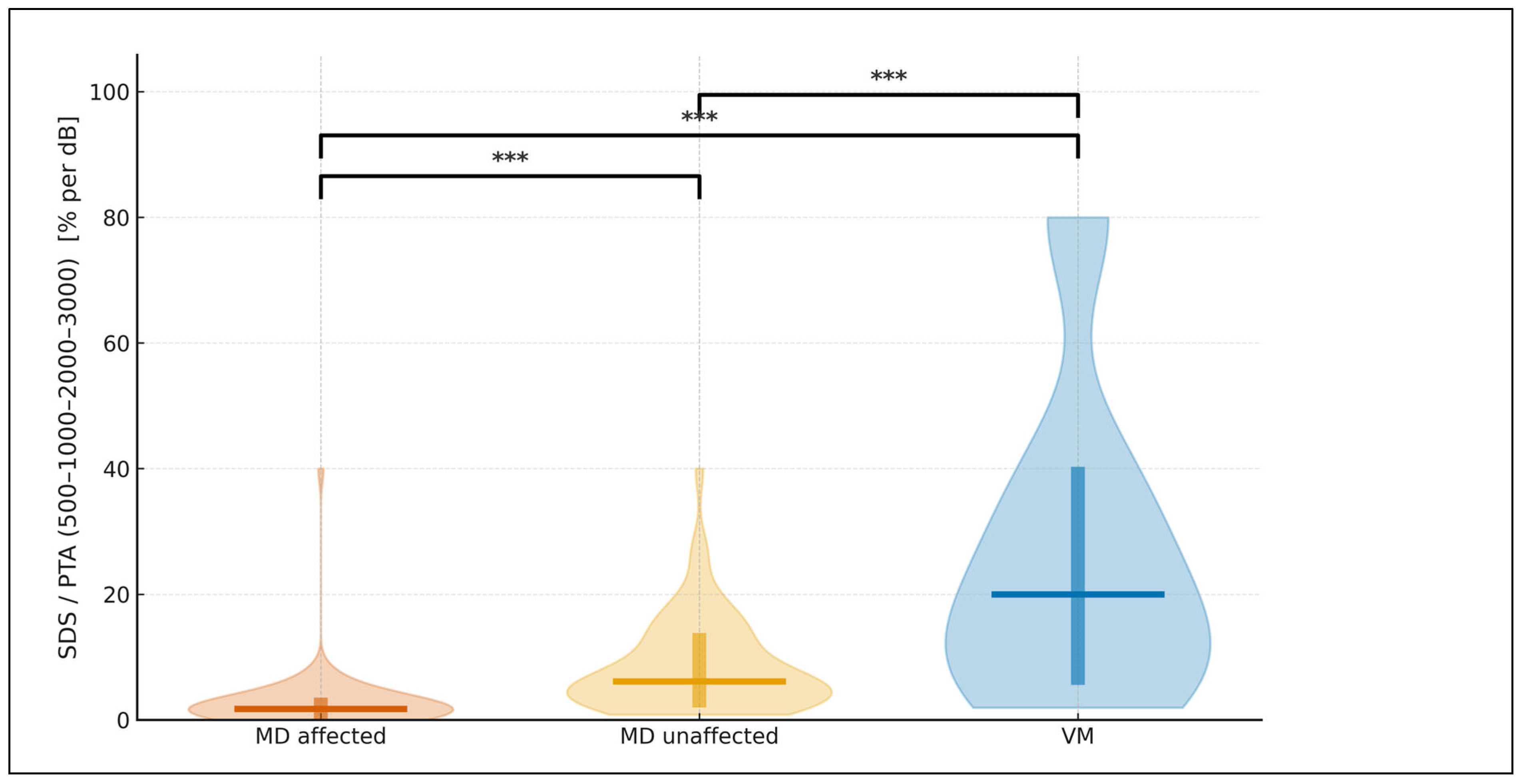

Table 4). To express this relationship in functional terms, we derived the SDS/PTA ratio, which estimates speech efficiency. As illustrated in

Figure 5, this ratio was highest in vestibular migraine, intermediate in MD-unaffected ears, and lowest in MD-affected ears. All three pairwise contrasts remained statistically significant after Bonferroni-adjusted, two-sided permutation testing. For visualization only, values were truncated to the 1st–99th percentiles, whereas all statistics were performed on the complete dataset.

Figure 2.

Group mean audiograms with SD ribbons. Bar charts display mean ± SD for (A) 250 Hz, (B) PTA 0.5–3 kHz and PTA 2–4 kHz, and (C) SDS (%). Significance markers (*, **, ***, “ns”) denote Bonferroni-adjusted two-sided permutation tests for all three pairwise comparisons (MD affected vs VM; MD affected vs MD unaffected; MD unaffected vs VM). X-axis labels: MD affected, MD unaffected, VM; Vestibular migraine ears.

Figure 2.

Group mean audiograms with SD ribbons. Bar charts display mean ± SD for (A) 250 Hz, (B) PTA 0.5–3 kHz and PTA 2–4 kHz, and (C) SDS (%). Significance markers (*, **, ***, “ns”) denote Bonferroni-adjusted two-sided permutation tests for all three pairwise comparisons (MD affected vs VM; MD affected vs MD unaffected; MD unaffected vs VM). X-axis labels: MD affected, MD unaffected, VM; Vestibular migraine ears.

Figure 3.

Scatterplots of SDS versus PTA. (A) Speech discrimination score (SDS) plotted against conventional PTA (500–1000–2000–3000 Hz). (B) SDS plotted against high-frequency PTA (3000–4000–6000 Hz). Red dots represent MD affected ears, blue dots represent MD contralateral ears, and green dots represent VM ears. Linear regression lines are shown for each group.

Figure 3.

Scatterplots of SDS versus PTA. (A) Speech discrimination score (SDS) plotted against conventional PTA (500–1000–2000–3000 Hz). (B) SDS plotted against high-frequency PTA (3000–4000–6000 Hz). Red dots represent MD affected ears, blue dots represent MD contralateral ears, and green dots represent VM ears. Linear regression lines are shown for each group.

Figure 4.

Violin plots show the distribution of SDS/PTA (500–1000–2000–3000) expressed in % per dB for MD affected (vermillion), MD unaffected (orange), and VM (blue). A horizontal line marks the median, and a thick vertical bar indicates the IQR (25th–75th percentiles) for each group. Brackets with asterisks denote Bonferroni-adjusted, two-sided permutation tests for the three pairwise comparisons (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001). The plotting range is limited to the 1st–99th percentiles for clarity; no observations were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Figure 4.

Violin plots show the distribution of SDS/PTA (500–1000–2000–3000) expressed in % per dB for MD affected (vermillion), MD unaffected (orange), and VM (blue). A horizontal line marks the median, and a thick vertical bar indicates the IQR (25th–75th percentiles) for each group. Brackets with asterisks denote Bonferroni-adjusted, two-sided permutation tests for the three pairwise comparisons (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001). The plotting range is limited to the 1st–99th percentiles for clarity; no observations were excluded from the statistical analysis.

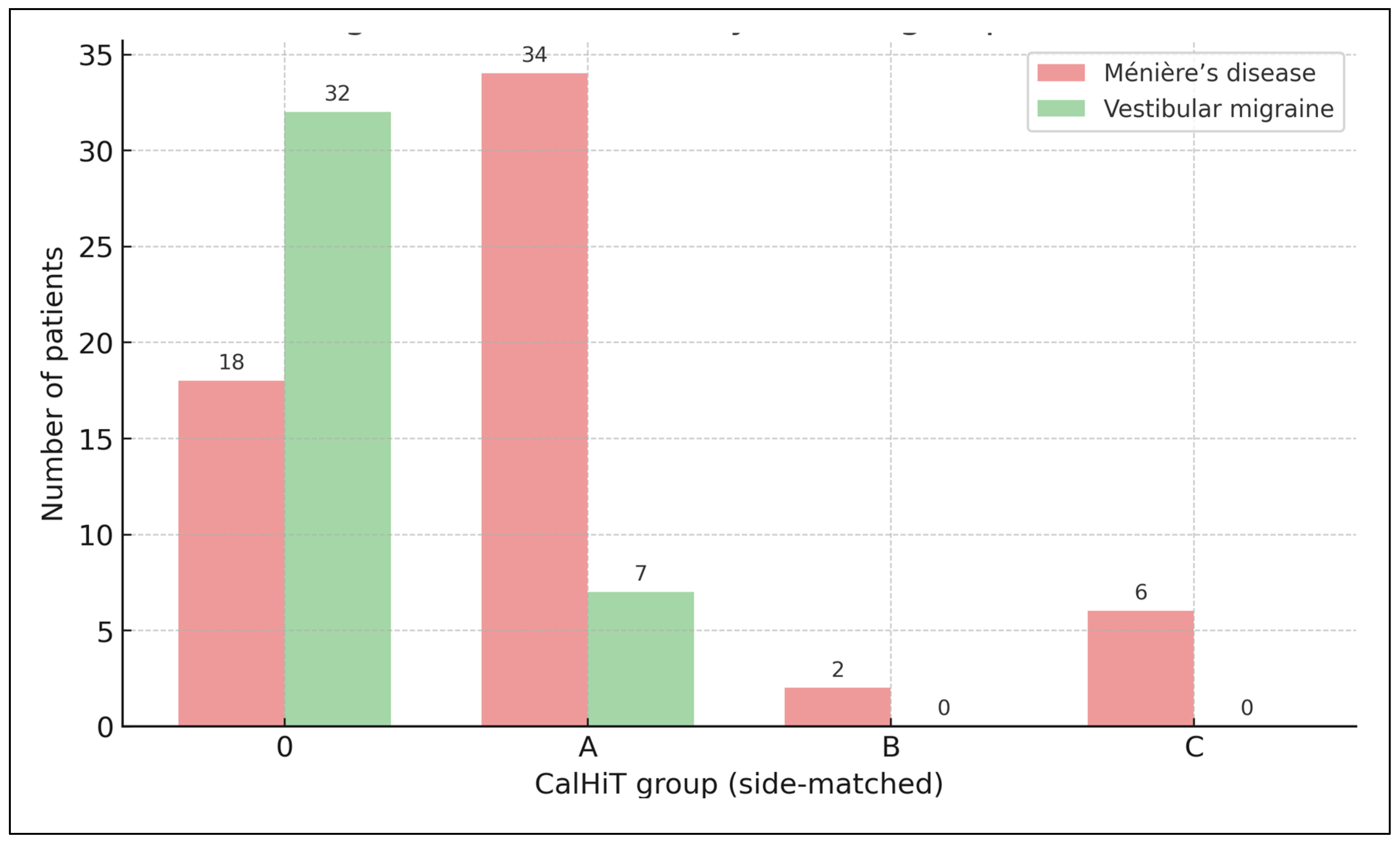

Figure 5.

Diagnosis distribution by CalHiT group (side-matched), counts. Bars show the number of patients per CalHiT group for Ménière’s disease (soft red) and vestibular migraine (soft green). Side-matched rule: the caloric lesser-function side is compared with the vHIT of the same side. CalHiT-0 = normal calorics and normal same-side horizontal vHIT; CalHiT-A = canal paresis ≥22% with same-side vHIT gain ≥0.80; CalHiT-B = normal calorics with same-side vHIT gain <0.80; CalHiT-C = study-specific atypical category.

Figure 5.

Diagnosis distribution by CalHiT group (side-matched), counts. Bars show the number of patients per CalHiT group for Ménière’s disease (soft red) and vestibular migraine (soft green). Side-matched rule: the caloric lesser-function side is compared with the vHIT of the same side. CalHiT-0 = normal calorics and normal same-side horizontal vHIT; CalHiT-A = canal paresis ≥22% with same-side vHIT gain ≥0.80; CalHiT-B = normal calorics with same-side vHIT gain <0.80; CalHiT-C = study-specific atypical category.

3.3. Vestibular Findings

In MD (n=60), the predominant class was CalHiT-A (56.7%, 34/60), followed by CalHiT-0 (30.0%, 18/60), CalHiT-C (10.0%, 6/60), and CalHiT-B (3.3%, 2/60). In vestibular migraine (n=40), CalHiT-0 dominated (80.0%, 32/40), with CalHiT-A at 17.5% (7/40) and CalHiT-B at 2.5% (1/40); no CalHiT-C cases were observed. (see

Figure 5).

Canal paresis (CP%) differed markedly by class: CalHiT-0 mean 11.36 (SD 5.52; median 10.5; n=50); CalHiT-A 46.46 (19.92; 45.0; n=41); CalHiT-B 13.33 (9.81; 19.0; n=3); CalHiT-C 54.67 (26.50; 50.0; n=6). Canal paresis (CP%) by diagnosis. MD: mean 35.05 (SD 21.90; median 31.5; n=60). VM: mean 18.45 (SD 22.00; median 10.0; n=40). Statistical contrasts (CP%). MD vs VM (Mann–Whitney U): U = 1896.5, p = 9.58×10−7 ⇒ CP% is significantly higher in MD than VM. Across CalHiT classes (Kruskal–Wallis): H = 74.36, p = 4.98×10−16 ⇒ CP% differs significantly across rule categories.

As expected, VM concentrates in CalHiT-0 (normal calorics and normal same-side vHIT), whereas MD shows a predominance of CalHiT-A (abnormal calorics with preserved same-side vHIT), with low CP% in CalHiT-0/B and high CP% in CalHiT-A/C.

We compared inter-aural amplitude ratios (IAAR, %) between MD and VM across click cVEMP, 100-Hz vibratory cVEMP, and vibratory oVEMP. IAAR distributions were centered near 0% with broad dispersion in both groups; values beyond ±40% occurred in each cohort. Two-sided permutation tests (10,000 permutations), Bonferroni-adjusted across modalities, showed no significant MD–VM differences (ns for all). Thus, IAAR did not discriminate MD from VM in this sample (Supplementary Table ST1, Figure SF1).

3.4. Multimodal Diagnostic Models

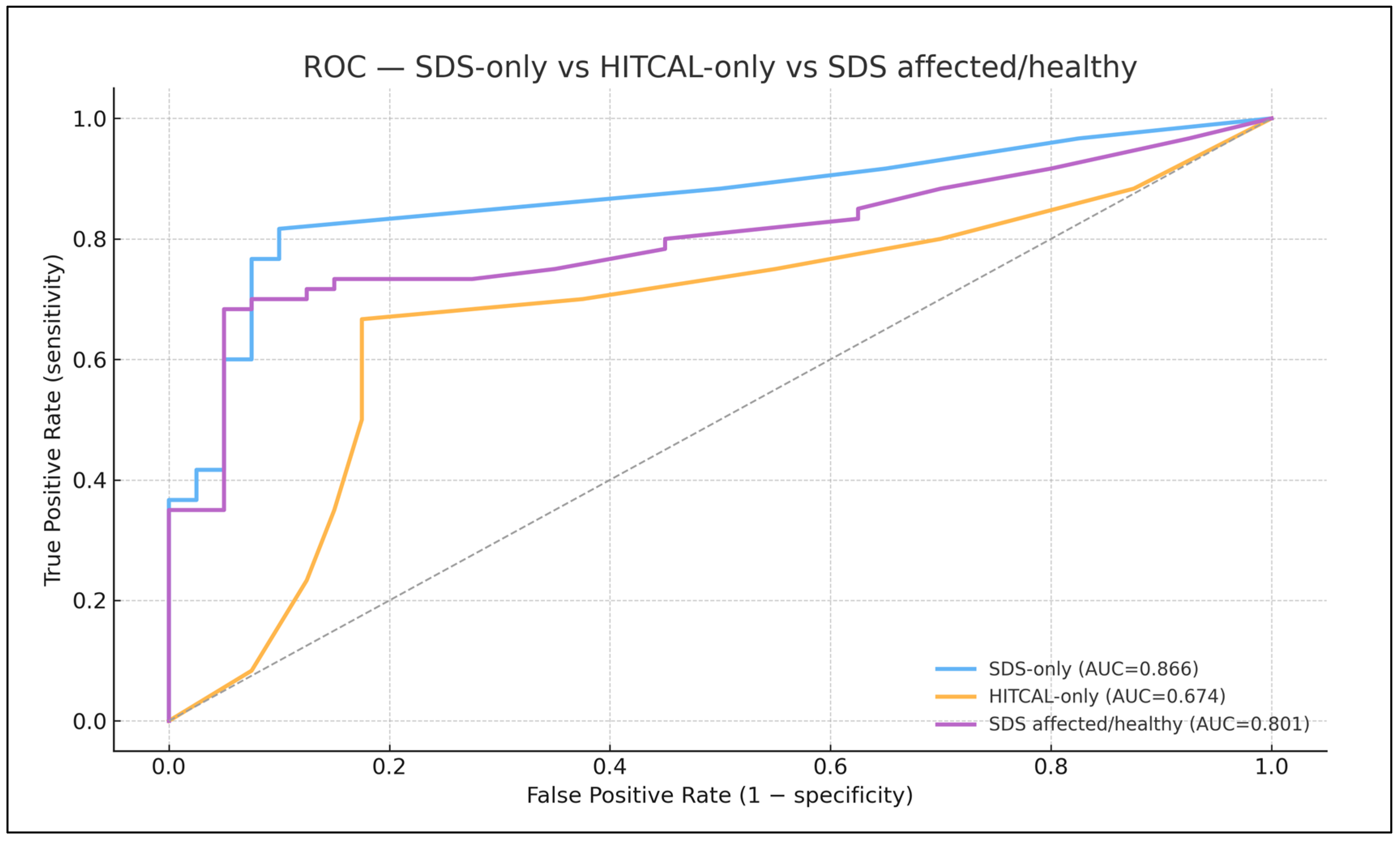

Overall diagnostic performance (primary analysis; logistic regression, 5-fold OOF CV) —

Figure 6

SDS-only (bilateral SDS per ear): ROC–AUC 0.866 (95% CI 0.787–0.937; n=100).

CalHiT-A-only (Yes/No): ROC–AUC 0.674 (0.561–0.778).

SDS + CalHiT-A: ROC–AUC 0.844 (0.760–0.913) — no improvement over SDS alone (overlapping CIs; no practical gain).

3.5. Exploratory SDS Encoding

Re-expressing SDS as “affected/healthy” (where available) underperformed the bilateral ear-wise specification (AUC 0.801 [0.706–0.882]). The combined SDS (affected/healthy) + CalHiT-A model remained inferior (AUC 0.816 [0.726–0.893]).

3.6. Prevalence Context

As above, CalHiT-A was present in 70.7% of MD (41/58) vs 16.7% of VM (9/54), p = 1.56 × 10−6, indicating strong physiologic separation at the group level despite the lack of incremental AUC when added to SDS in patient-level models.

Calibration and decision analysis. Calibration and decision-curve analyses are summarized in the Supplement; neither altered the primary conclusion that SDS alone provides the highest and most parsimonious discrimination, with no consistent benefit from adding CalHiT-A.

4. Discussion

Distinguishing Ménière’s disease (MD) from vestibular migraine (VM) remains challenging because prevailing diagnostic frameworks are largely clinical and place heavy weight on pure-tone thresholds thus creating a risk of incorporation bias when PTA is also used as a predictor. Within this context, our work shows that bilateral speech discrimination scores (SDS, per ear) provide strong, well-calibrated discrimination between MD and VM without circularity, and that the simple SDS/PTA ratio adds a functional perspective beyond tone thresholds. In parallel, the caloric–vHIT dissociation, pattern A (CalHiT-A: abnormal calorics with preserved same-side horizontal vHIT, side-matched) captures a vestibular phenotype highly characteristic of MD at the group level and clinically valuable for adjudication and phenotyping even if, in our dataset, it did not improve AUC once SDS was in the model. We therefore propose a dual-axis diagnostic paradigm: Audiologic (SDS / SDS-PTA) for primary classification, and Vestibular (CalHiT-A) for adjudication and phenotype definition.

Previous research has emphasized the divergence between PTA and SDS in Ménière’s disease (26). Current guidelines prioritize documenting fluctuation through serial PTA measurements (ideally obtained during or shortly after attacks) and, in practice, rely on tonal thresholds for longitudinal monitoring. While indispensable for defining auditory change, this emphasis entails two limitations: (i) it risks circularity, as PTA values contribute both to diagnostic criteria and prognostic modeling; and (ii) it underrepresents the functional dimension that matters most to patients—speech understanding. In the present study, we intentionally excluded PTA from predictive modeling to minimize incorporation bias and demonstrated that bilateral SDS alone achieved high discrimination and robust calibration relative to vestibular markers. Re-expressing SDS as a simple “affected/healthy” difference did not outperform the bilateral, ear-wise representation.

Speech audiometry has long been acknowledged within the diagnostic framework of Ménière’s disease. The 1972 Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium already recognized its contribution to evaluating functional hearing (27). The 1985 revision went further, explicitly requiring the use of word recognition scores (WRS) alongside pure-tone audiometry to define clinically significant hearing changes, setting a ≥ 15% difference in WRS as the criterion for both diagnosis and therapeutic follow-up (28). Subsequent iterations (17, 8) maintained the inclusion of speech testing but gradually relegated it to a secondary role, emphasizing tonal thresholds as the principal benchmark for progression. Our results revive and extend that early vision: by demonstrating that bilateral SDS alone discriminates effectively between MD and VM and that speech efficiency (SDS/PTA) systematically distinguishes affected from unaffected ears, this study provides empirical support for reinstating speech audiometry as a core diagnostic element. Rather than a discretionary adjunct, it should be regarded as integral to the audiologic phenotype of Ménière’s disease.

The SDS/PTA (0.5–3 kHz) ratio in this study operates as a speech-efficiency index: for a given amount of tonal loss, how effectively does the patient recognize words?. Importantly, SDS and PTA are associated but PTA does not deterministically set SDS as intelligibility depends on more than audibility (e.g., distortion, recruitment, temporal and suprathreshold factors). We therefore use SDS/PTA as a descriptive index (not a model predictor) to express “speech per unit of tone loss”. In our cohort, SDS/PTA showed a graded pattern (VM highest, MD-unaffected intermediate, MD-affected lowest), indicating that the decline in intelligibility in MD exceeds what would be expected from thresholds alone. The metric is simple and readily standardized (fixed presentation level; recorded, equivalent lists; predefined 0.5–3 kHz band). This builds on a well-established audiologic principle: the SDS–PTA relationship has long been used to flag retrocochlear involvement when speech discrimination is disproportionately poor relative to mild pure-tone loss, helping distinguish cochlear from retrocochlear pathology (29) and we previously have shown how it evolves in follow-up MD (22). We advocate routine reporting of SDS/PTA alongside SDS and PTA to better capture the functional footprint of MD and to enable clean longitudinal tracking of functional fluctuation.

Between attacks, vestibular migraine generally shows near-normal pure-tone thresholds with ceiling-level SDS, whereas Ménière’s disease shows depressed (often asymmetric) SDS. An SDS-centered workflow, qualified by SDS/PTA, therefore resolves much of the diagnostic ambiguity without invoking predictors embedded in the case definition. That a purely tonal model performs well is unsurprising given current criteria; the clinically meaningful advance is that SDS performs as well or better without circularity and with superior calibration.

CalHiT-A (abnormal calorics with preserved same-side horizontal vHIT; side-matched rule) reflects the frequency-time dissociation between tests that do also reflect different grounds: caloric is a test of nystagmus while vHIT is a test of vestibulo-ocular reflex. It aligns also with known hydropic mechanics (30, 31). In our sample, CalHiT-A was far more prevalent in MD than in VM (56.7% [34/60] vs 17.5% [7/40]; Fisher’s exact p = 1.49×10−4), underscoring group-level specificity. Although adding CalHiT-A to SDS did not increase AUC in patient-level models, CalHiT-A does add clinical value: it (i) adjudicates borderline cases when SDS/SDS-PTA are equivocal, (ii) defines phenotypes (e.g., MD–CalHiT-A) with potential prognostic and therapeutic implications, and (iii) documents vestibular physiology in a disease where vertigo attacks drive much of the disability while VM is defined by burdensome vestibular symptoms. For these reasons, CalHiT-A should be explicitly included in diagnostic pathways, as a minimum recommended vestibular criterion (at least once during work-up) and as a phenotypic descriptor (16, 32, 33, 34).

In our cohort, inter-aural amplitude ratios (IAAR) for click cVEMP, 100-Hz vibratory cVEMP, and vibratory oVEMP were centered near 0% with broad dispersion in both MD and VM. Given this lack of discriminatory signal at the univariate level, we did not include VEMPs in the predictive models. This preserves parsimony and calibration, avoids penalizing patients with missing otolithic data, and prevents diluting the clear audiologic and canal-level vestibular effects (SDS/SDS-PTA and CalHiT-A). Methodologically, VEMP amplitudes are susceptible to high physiological and technical variance (age effects, sternocleidomastoid activation, montage, conductive factors, and time since the last vertigo spell or activity of the disease), which can obscure modest between-diagnosis differences. Clinically, our results suggest that VEMPs add limited value for the binary MD-VM separation, although they remain useful for otolithic phenotyping, longitudinal tracking, and specific differential diagnoses outside the present scope. Future work could revisit VEMPs using EMG-normalized metrics, frequency-tuning paradigms, or interaction-aware models (e.g., coupling VEMP features to depressed SDS or low SDS/PTA), but on current evidence they should not be part of the primary MD–VM classifier.

In keeping with AAO-HNS/Bárány frameworks that already stress documenting fluctuation with PTA, we propose three concrete additions for future updates: (1) make bilateral SDS mandatory for diagnosis and follow-up of MD, alongside PTA/SRT, using a standardized protocol (recorded, equivalent lists; stable presentation level); (2) report SDS/PTA (0.5–3 kHz) routinely as an efficiency index to enable inter-center comparability and longitudinal interpretation anchored to function; (3) adopt CalHiT-A (side-matched caloric/vHIT dissociation) as a recommended vestibular criterion and as a phenotypic label (e.g., MD–CalHiT-A±), obtained with calorics + vHIT at least once and repeated when clinical decisions hinge on vestibular status—i.e., a shift from “PTA-centric” to “dual-axis.”

It is important to note that our analyses were conducted under a specific, historically grounded audiometric methodology (35). For speech discrimination testing we recommend two practical implementation options: (1) a two-step fixed-level rule presenting SDS monaurally at 65 dB HL with recorded, equivalent lists via inserts/supra-aurals; if the sensation level is low (e.g., SRT > 35 dB HL) or approaches UCL, switch to SRT+35 dB HL or MCL; or (2) a single-step variable-level rule presenting SDS at SRT+35 dB HL (or MCL) from the outset. We used rule (1) in this study because it maximizes comparability across visits and aligns with conversational levels; whichever option is chosen, we recommend documenting the exact presentation level, transducer, list ID, and masking.

Strengths include an analysis free of incorporation bias (PTA excluded from modeling), patient-level, out-of-fold validation, and pre-specified comparisons across SDS, CalHiT-A, and SDS+CalHiT-A with calibration and decision-curve evaluation as currently ongoing (36). Limitations include the retrospective, single-center design; use of Spanish recorded lists at a fixed level; absence of hydrops MRI as a predictor in the primary model; and interictal testing (peri-attack speech testing could increase sensitivity).

5. Conclusions

Bilateral speech audiometry (with SDS as the anchor and SDS/PTA as a complementary index) should be part of the diagnostic and follow-up core for Ménière’s disease because it offers high, non-circular discrimination and maps to functional outcomes. CalHiT-A is necessary to capture vestibular physiology, adjudicate ambiguous cases, and define clinically useful phenotypes. A dual-axis strategy (SDS/SDS-PTA for primary classification and CalHiT-A for adjudication/phenotyping) provides a pragmatic, patient-centered path ready for clinical adoption and worthy of inclusion in future guidelines.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients who participated in this study and the clinical staff of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology in Clinica Universidad de Navarra in Pamplona, for their assistance with audiological and vestibular testing. We also thank the institutional ethics committee for their guidance throughout the study. Statistical analyses involving multivariable machine learning models and assistance in language revision were supported by ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA). The authors maintained full intellectual control over the content, and all outputs generated by the tool were critically reviewed, validated, and revised for accuracy and consistency with the study data.

References

- Huppert D, Grill E, Becker-Bense S, Zwergal A, Strobl R. Diagnostic challenges in vestibular migraine-clinical differentiation from Menière’s disease and discrepancies with current classification criteria. J Neurol. 2025; 272. Article number 558. [CrossRef]

- Yin H, Li H, Zheng Y, Jia Y, Shen B, Sun Y, Sun S, Zhang Y, Peng W, Liu C. Synergistic role of blood-labyrinth barrier permeability and endolymphatic hydrops: a comparative perspective in Ménière’s disease and vestibular migraine. Front Neurol. 2025 Sep 3;16:1667277. [CrossRef]

- Klokman VW, Verhagen MJJ, Sanders MS, Jellema K, de Kleijn DPV, Jie KE. Blood Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Peripheral Causes of Vestibular Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2025 Oct 1;46(9): e359-e369. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Escamez JA, Carey J, Chung WH, Goebel JA, Magnusson M, Mandalà M, Newman-Toker DE, Strupp M, Suzuki M, Trabalzini F, Bisdorff A; Classification Committee of the Barany Society; Japan Society for Equilibrium Research; European Academy of Otology and Neurotology (EAONO); Equilibrium Committee of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS); Korean Balance Society. Diagnostic criteria for Menière’s disease. J Vestib Res. 2015; 25: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, Waterston J, Seemungal B, Carey J, Bisdorff A, Versino M, Evers S, Newman-Toker D. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res. 2012; 22: 167-72. [CrossRef]

- Gürkov R, Hornibrook J. On the classification of hydropic ear disease (Menière’s disease). HNO. 2018; 66: 455-63. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium. Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Ménière’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; 113: 181-5. [CrossRef]

- Basura GJ, Adams ME, Monfared A, Schwartz SR, Antonelli PJ, Burkard R, Bush ML, Bykowski J, Colandrea M, Derebery J, Kelly EA, Kerber KA, Koopman CF, Kuch AA, Marcolini E, McKinnon BJ, Ruckenstein MJ, Valenzuela CV, Vosooney A, Walsh SA, Nnacheta LC, Dhepyasuwan N, Buchanan EM. Clinical Practice Guideline: Ménière’s Disease Executive Summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020; 162: 415-34. [CrossRef]

- Montes-Jovellar L, Guillen-Grima F, Perez-Fernandez N. Cluster analysis of auditory and vestibular test results in definite Menière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 2011; 121: 1810-7. [CrossRef]

- Frejo L, Cara FE, Flook M, Robles-Bolivar P, Escalera-Balsera A, Montilla-Ibañez MA, Dominguez-Duran E, Martinez-Martinez M, Perez-Carpena P, Lopez-Escamez JA. Allergy and autoinflammation drive persistent systemic inflammatory response in Meniere Disease: A longitudinal study. Clin Immunol. 2025 Feb; 271:110413. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki S, Shojaku H, Murofushi T, Seo T, Kitahara T, Origasa H, Watanabe Y, Suzuki M, Takeda N; Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines of Japan Society for Equilibrium Research. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for Meniere’s disease of the Japan Society for Equilibrium Research. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2021; 48: 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Guo Z, Wang J, Tian E, Chen J, Zhou L, Kong W, Zhang S. Development and Validation of the Predictive Model for the Differentiation between Vestibular Migraine and Meniere’s Disease. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 14;11(16):4745. [CrossRef]

- Vivar G, Strobl R, Grill E, Navab N, Zwergal A, Ahmadi SA. Using Base-ml to Learn Classification of Common Vestibular Disorders on DizzyReg Registry Data. Front Neurol. 2021 Aug 2;12:681140. [CrossRef]

- McGarvie L.A., Curthoys I.S., MacDougall H.G., Halmagyi G.M. What does the dissociation between the results of video head impulse versus caloric testing reveal about the vestibular dysfunction in Ménière’s disease? Acta Otolaryngol. 2015; 135: 859-65. [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Yanza JA, Arrieta Vázquez EV, Hernaiz Leonardo JC, Mancera Sánchez J, Hernández Palestina MS, Pérez-Fernández N. Comparative study between the caloric vestibular and the video-head impulse tests in unilateral Menière’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017; 137: 1178-82. [CrossRef]

- Tamanini JB, Mezzalira R, Vallim MGB, Gabriel GP, Stoler G, Chone CT. Dissociation between video head impulse test and caloric test: a marker of Menière’s disease?-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2023; 89: 101279. [CrossRef]

- Goebel JA. 2015 Equilibrium Committee Amendment to the 1995 AAO-HNS Guidelines for the Definition of Ménière’s Disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016; 154: 403-4. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Carbonell T, Orts-Alborch M, Pla-Gil I, Pérez-Guilén V, Tenías-Burrillo JM, Marco-Algarra J, Pérez-Garrigues H. Bilateral Ménière’s disease according to its form of debut: synchronous and metachronous disease. J Laryngol Otol. 2023; 137: 782-8. [CrossRef]

- Pérez N, Garmendia I, Martín E, García-Tapia R. Adaptación cultural de dos cuestionarios de medida de la salud en pacientes con vértigo [Cultural adaptation of 2 questionnaires for health measurement in patients with vertigo]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2000; 51: 572-80.

- Yardley L, Masson E, Verschuur C, Haacke N, Luxon L. Symptoms, anxiety and handicap in dizzy patients: development of the vertigo symptom scale. J Psychosom Res. 1992; 36: 731-41. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Zorrilla GE, Pérez-Fernández N, Hernández-Palestina MS, Carrillo-Mora P. Vértigo: correlación entre los indicadores objetivos y subjetivos de gravedad, incapacidad y limitación funcional. An Orl Mex. 2014; 59: 181-6.

- Garaycochea O, Manrique-Huarte R, Calavia D, Girón L, Pérez-Fernández N. Speech Recognition During Follow-Up of Patients with Ménière’s Disease: What Are We Missing? J Int Adv Otol. 2022; 18: 14-9. [CrossRef]

- Jerger J, Jerger S. Auditory disorders: a manual for clinical evaluation. Boston: Little, Brown; 1974.

- Guajardo-Vergara C, Pérez-Fernández N. Air and bone stimulation in vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in patients with unilateral Ménière’s disease and in controls. Hear Balance Commun. 2019; 17: 170-8. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12:2825-30.

- Mateijsen DJ, Van Hengel PW, Van Huffelen WM, Wit HP, Albers FW. Pure-tone and speech audiometry in patients with Menière’s disease. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2001; 26: 379-87. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium. Report of Subcommittee on Equilibrium and its Measurement. Meniere’s disease: criteria for diagnosis and evaluation of therapy for reporting. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 197; 76: 1462-4.

- Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for Meniere’s disease, published in the AAO-HNS Bulletin, 1985; 5(July): 6–7,.

- Marinelli JP, Reed NS, Lohse CM, Fussell WL, Petersen RC, Machulda MM, Vassilaki M, Carlson ML. Cognitive Performance, Sociodemographic Factors, Pure-Tone Audiometry, and their Association with Speech Discrimination: A Prospective Population-Based Study of 1,061 Older Adults. Otol Neurotol. 2023; 44: 860-55. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fernández N, Dominguez P, Manrique-Huarte R, Calavia D, Arbizu L, Garcia-Eulate R, Alvarez-Gomez L, Guajardo C, Zubieta JL. Endolymphatic hydrops severity in magnetic resonance imaging evidences disparate vestibular test results. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019; 46: 210-217. [CrossRef]

- Connor S, Grzeda MT, Jamshidi B, Ourselin S, Hajnal JV, Pai I. Delayed post gadolinium MRI descriptors for Meniere’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2023; 33: 7113-55. [CrossRef]

- Mavrodiev V, Strupp M, Vinck AS, van de Berg R, Lehner L. The dissociation between pathological caloric testing and a normal video head impulse test helps differentiate between Menière’s disease, vestibular migraine, and other vestibular disorders: a confirmatory study in a large cohort of 2,101 patients. Front Neurol. 2024 Aug 14;15:1449261. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz MS, Egilmez OK, Kara A, Guven M, Demir D, Genc Elden S. Comparison of the results of caloric and video head impulse tests in patients with Meniere’s disease and vestibular migraine. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 202; 278: 1829-1834. [CrossRef]

- Melville IZ, Yamsuan K, Wu H, Thorne PR, Kobayashi K, Taylor RL. Do measures of gain asymmetry and catch-up saccades improve video head impulse test agreement with caloric results? Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2024;9: 217-26. [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Piera J, Blanco M, Santos-Garrido J, Manrique-Huarte R, Suárez-Vega V, Domínguez P, Fullaondo J, Arbizu L, Pérez-Fernández N. Functional Audiometric Dissociation in Ménière’s Disease: Exploring the Mismatch Between Pure-Tone Thresholds and Speech Recognition. J Clin Med. 2025 Jul 4;14(13):4747. [CrossRef]

- Du Y, Liu X, Ren L, Wang Y, Wu Z. Multidimensional Feature Analysis of Meniere’s Disease and Vestibular Migraine: Insights from Machine Learning and Vestibular Testing. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2025; 26: 287-300. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).