1. Introduction

Tidal flats, as dynamic intertidal zones periodically submerged and exposed by tides [

1,

2], are critical transitional ecosystems bridging land and sea. Globally, tidal flats span approximately 354,600 km²(60°N–60°S) [

3], serving as biodiversity hotspots [

4], key habitats for coastal species [

5], and providers of essential ecosystem services, including coastal stabilization [

6], water purification [

7], and carbon sequestration [

8]. However, these vulnerable ecosystems [

9] face escalating threats from climate change (e.g., sea-level rise [

10]) and anthropogenic activities (e.g., industrialization and coastal development [

11]). Between 1984 and 2016, global tidal flat area declined by 16.02% [

3], triggering ecological degradation and biodiversity loss. China, with its 18,000 km coastline [

12] and the world’s second-largest tidal flat area [

2], plays a pivotal role in migratory bird pathways and biodiversity conservation. Systematic monitoring of China’s tidal flats is thus imperative—not only to refine global carbon cycle assessments but also to advance sustainable development goals (SDGs) for coastal resilience.

Satellite remote sensing has emerged as the primary tool for tidal flat monitoring, with four key technical components: (1) Data selection: Landsat series (30 m resolution) dominate global-scale studies, while Sentinel-2 (10 m) is preferred for regional analyses; (2) Spectral indices: Enhanced water-land contrast [

13,

14] via indices like NDWI [

15], mNDWI [

16], or specialized tidal flat indices (e.g., LTideI [

17], TWDI [

18]); (3) Temporal analysis: Characterization of tidal phases through time-series imagery (e.g., extreme-value compositing [

19]); and (4) Classification and validation: Machine learning [

17] or thresholding [

14] for tidal flat extraction, coupled with accuracy assessments using ground-reference points.

Under this framework, various global and regional tidal flat datasets have been developed. At the global scale, representative products include the UQD (1984–2019, 30 m) [

2] and GTF30 (2000–2022, 30 m) [

17], both based on Landsat time-series data, as well as the GWL_FCS30 (2020, 30 m) [

20], which integrates Sentinel-1 and Landsat data. Regionally, the MTWM-TP (2020, 10 m) [

9] based on Sentinel-2 was developed for coastal East Asia, while datasets for China’s coastal areas include the Sentinel-2-derived CTF (2019, 10 m) [

14] and TFMC (2020, 10 m) [

18], along with the Landsat-based FUDAN/OU (2015, 2018, 30 m) [

21] and DCTF (1989–2020, 30 m) [

22]. Additionally, regional datasets such as SZU (2015, 30 m) [

10] and IGSNRR (2017, 10 m) [

23] cover northern and southern coastal China, respectively. Although these datasets provide valuable support for tidal flat research, they exhibit significant spatial heterogeneity due to methodological differences (e.g., sensor resolution, spectral indices, and classification algorithms). While most datasets claim accuracies exceeding 85%, their reliability for scientific and policy applications remains limited in the absence of cross-dataset validation.

To address these gaps, we conduct a systematic evaluation of six 2020 tidal flat datasets (GTF30, GWL_FCS30, MTWM-TP, DCTF, CTF, TFMC) across China’s coastal zone, with three objectives: (1) Quantify spatial consistency among datasets; (2) Perform independent edge-based validation (2,550 samples) using confusion matrices, overall accuracy (OA), and Kappa coefficients; and (3) Diagnose methodological drivers (e.g., data sources, indices, algorithms) of observed discrepancies. Our work provides a critical benchmark for dataset selection and methodological optimization in tidal flat mapping.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 describes the study area and datasets;

Section 3 details the methodology;

Section 4 presents comparative results;

Section 5 discusses technical implications; and

Section 6 concludes with recommendations.

2. Study Area and Dataset

2.1. Study Area

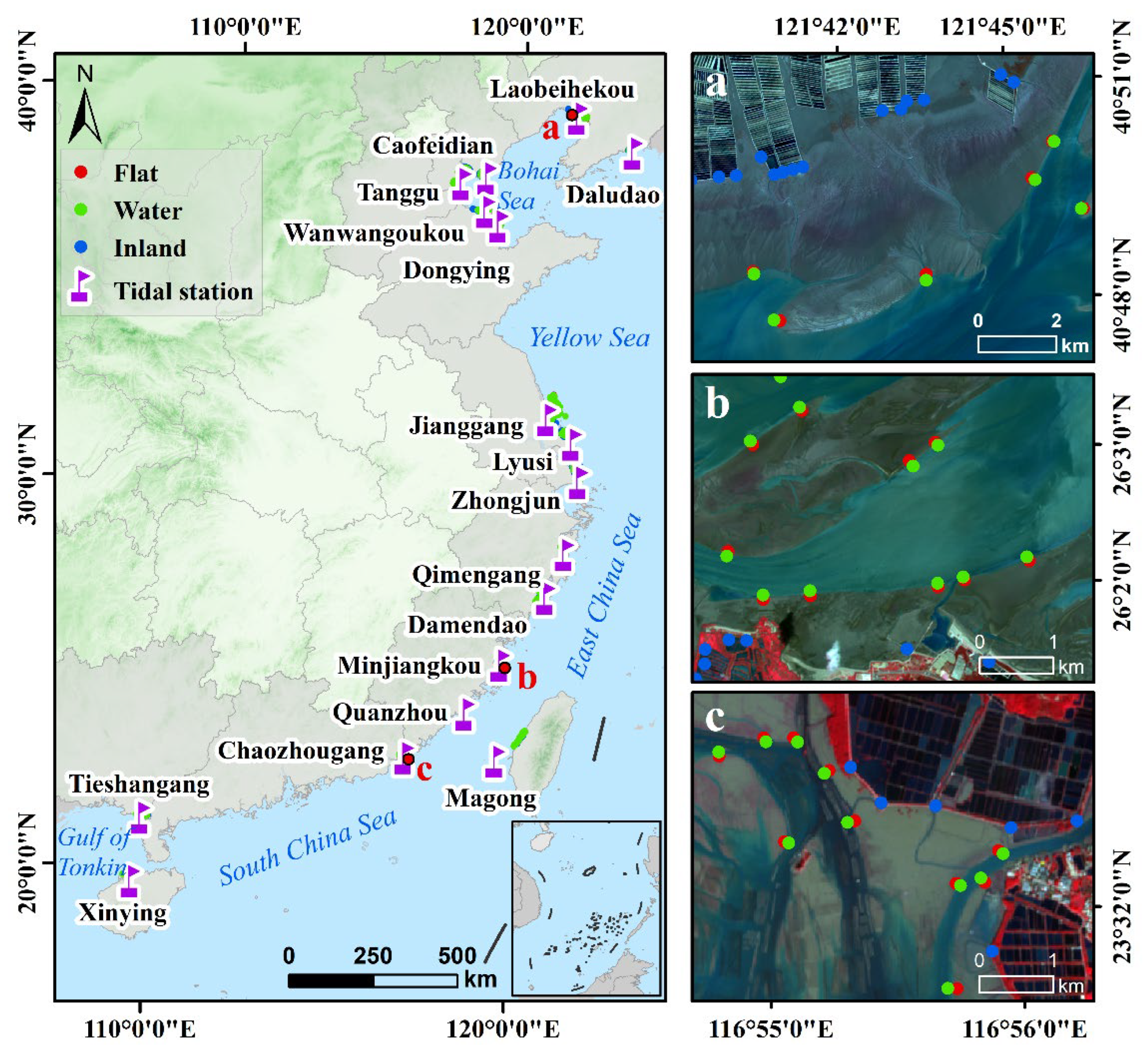

China's coastal zone, spanning from the Yalu River estuary (40.5°N) to the Beilun River estuary (18.2°N), encompasses 12 provincial-level administrative regions (including Taiwan and Hainan islands) with a total coastline of ~18,000 km (

Figure 1). This region traverses tropical, subtropical, and temperate climate zones, supporting diverse wetland ecosystems such as tidal flats, salt marshes, and mangroves. To capture the full ecological gradient, we defined the study area as a 5 km landward and 30 km seaward buffer from the mainland and island coastlines. This delineation ensures comprehensive coverage of intertidal dynamics while minimizing interference from non-coastal landscapes.

2.2. Publicly Available Tidal Flat Datasets

We evaluated six 2020 tidal flat datasets covering China’s coastal zone (

Table 1). These include two global-scale datasets: (1) GTF30 (2000–2022, 30 m) (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7936721), developed by Zhang et al. [

17] using Landsat imagery and a random forest classifier based on the LTideI index; and (2) GWL_FCS30 (2020, 30 m) (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7340516), a global wetland classification that integrates Sentinel-1 and Landsat data, with tidal flats as a subset category [

20]. At the regional scale, we assessed four datasets: (1) MTWM-TP (2020, 10 m) (

https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Fujian_zip/14331785), covering East Asia’s coastline [

10], which combines Sentinel-2 imagery with tidal-phase and phenological features to classify tidal flats, salt marshes, and mangroves; (2) DCTF (1989–2020, 30 m) (

https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.10.06.V1), a China-focused dataset [

22] derived from Landsat using a random forest classifier and encompassing tidal flats and salt marshes; and (3–4) CTF (2019, 10 m) (

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112285) and TFMC (2020, 10 m) (

https://code.earthengine.google.com/a4256918c4c85e863bb52f2e57a631de), both generated via Google Earth Engine (GEE) using Sentinel-2 data. The CTF [

14] employs NDVI and mNDWI indices, while TFMC [

18] introduces the novel Tidal Wetland Dynamic Index (TWDI); both apply time-series index extremum compositing coupled with Otsu threshold segmentation for tidal flat extraction.

3. Methods

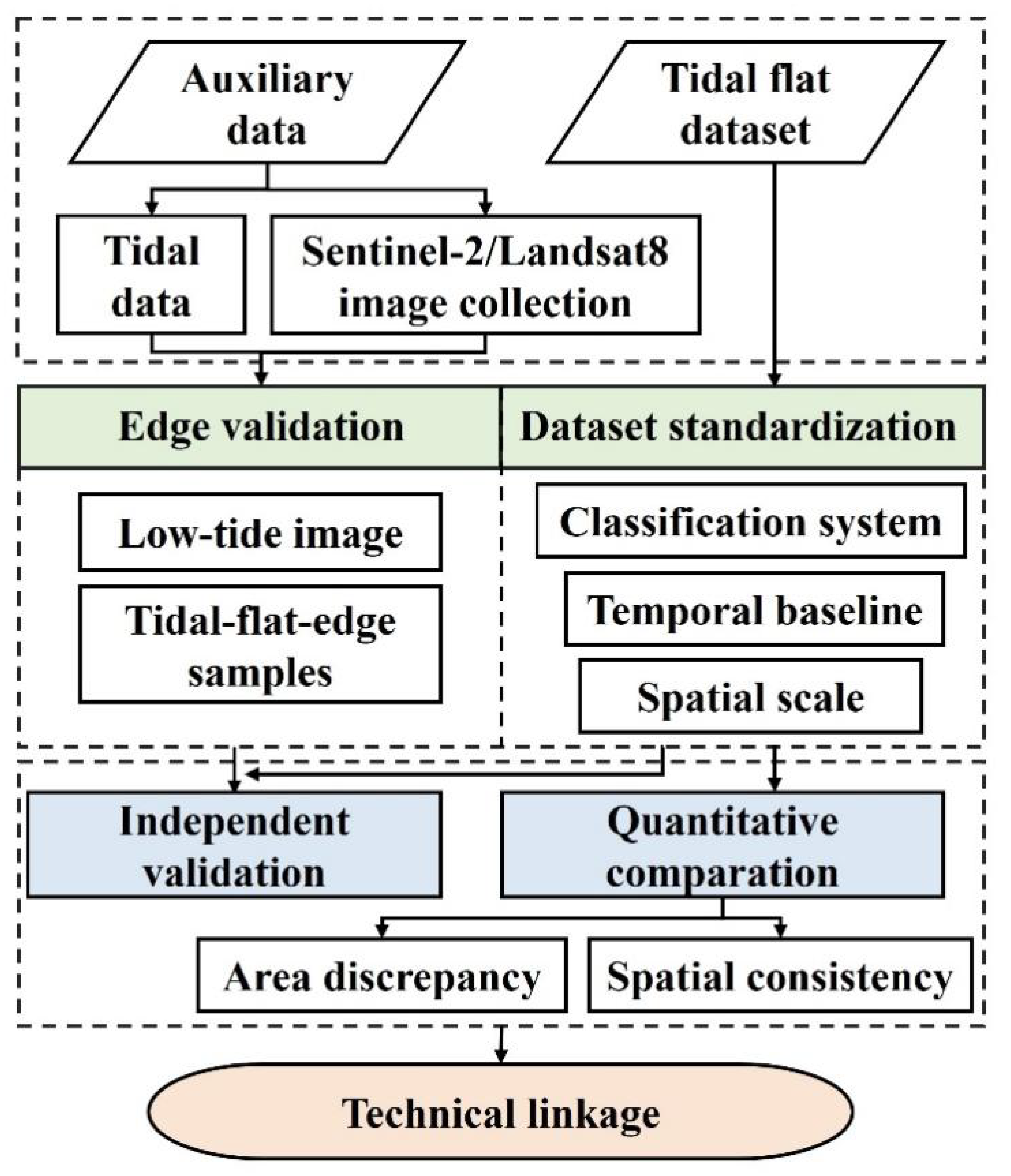

This study systematically evaluates tidal flat datasets through four key steps(

Figure 2):(1) Dataset standardization: Harmonizing classification systems, temporal baselines, and spatial scales to ensure inter-dataset comparability. (2) Quantitative comparison: Quantifying area discrepancies across datasets using the Coefficient of Variation (CV) and analyzing spatial consistency on a per-pixel basis through a six-level pixel-wise metric.(3) Independent validation: Assessing edge classification accuracy with tide-gauge-aligned tidal-flat-edge samples and quantifying precision metrics via a confusion matrix. (4) Technical linkage: Linking methodological differences to performance outcomes—specifically, investigating how variations in data sources, spectral indices, time-series analysis, and classification algorithms influence the observed differences in area estimation and spatial accuracy among datasets.

3.1. Dataset Standardisation

To ensure comparability [

24], we addressed three key sources of heterogeneity in the datasets. First, regarding classification systems, for datasets that contain multiple classes (e.g., GWL_FCS30, DCTF, MTWM-TP), we extracted “tidal-flat” pixels using the original class labels, excluding non-target classes such as salt marsh and mangroves. Second, for temporal consistency, we standardized the temporal baselines by retaining only 2020 data from multi-year datasets (e.g., GWL_FCS30, DCTF). Although MWTM-TP incorporated imagery from June 2019 to December 2020 and CTF used data from January 2019 to June 2020, we considered these representative of 2020 due to the demonstrated short-term stability of tidal flats, which exhibit change rates below 5% between 2001 and 2016 [

25]. Finally, to resolve spatial-scale discrepancies, we uniformly resampled all datasets to 10 m resolution using China’s provincial boundaries obtained from the National Platform for Common Geospatial Information Services (Tianditu,

https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/), with area calculations performed under the Albers Equal-Area projection to maintain geometric accuracy.

3.2. Quantitative Comparison

We assessed the heterogeneity among the six tidal-flat products along two dimensions: area discrepancy and spatial consistency.

3.2.1. Area Discrepancy

At the provincial scale, the coefficient of variation (CV) of tidal-flat area across the six products was calculated as:

where

is the mean area of the six datasets,

is the standard deviation,

denotes the area of the i-th dataset, and N is the total number of datasets (N = 6). A higher CV indicates larger inter-product differences within the province.

3.2.2. Spatial Consistency

(1) Multi-product agreement

Each product was resampled to a 10 m binary mask (1 = tidal flat, 0 = other). For every pixel, we counted how many products classified it as tidal flat and assigned an agreement level from 1 to 6, with level 6 indicating unanimous agreement among all products.

(2) Pair-wise overlap

The Spatial Consistency index (SC) [

26]was used to quantify the overlap between any two products:

where M is the number of tidal-flat pixels jointly identified by both datasets, and X and Y are the total numbers of tidal-flat pixels identified by each individual dataset, respectively. SC ranges from 0 to 1; values closer to 1 denote higher consistency between the two datasets.

3.3. Edge Validation

3.3.1. Sample Collection

To cover all coastal provinces, we selected 17 tide-gauge stations (

Figure 3) and added extra stations in provinces with large tidal-flat areas such as Jiangsu and Liaoning. For each station.

For each station, tidal-synchronous imagery analysis was performed by matching Landsat-8/9 and Sentinel-2 overpass times with tide records from the National Marine Science Data Center (

https://mds.nmdis.org.cn/pages/tidalCurrent.html). The instantaneous tide height (H) at image acquisition was calculated through linear interpolation using tidal harmonic equations:

where

and

represent adjacent low- and high-tide heights,

denotes the tidal range, T indicates the time interval between image acquisition and the nearest high/low tide, and t corresponds to the duration between two tide extremes. Scenes acquired at low-tide stages with ≤60% cloud cover were retained, followed by cloud masking, details for each province are listed in

Table 2.

For edge validation, each qualifying low-tide image was systematically sampled with 50 random points along the tidal-flat/water boundary and 50 points along the tidal-flat/land boundary (

Figure 3, right), collectively generating 2,550 samples to specifically evaluate boundary delineation accuracy.

3.3.2. Accuracy Assessment

The collected samples were utilized to build confusion matrices for calculating classification accuracy metrics, including overall accuracy (OA), producer's accuracy (PA), and user's accuracy (UA). MTWM-TP lacks data for Taiwan Province, corresponding results are therefore reported as missing.

4. Results

4.1. Inter Dataset Variability in Tidal-Flat Area

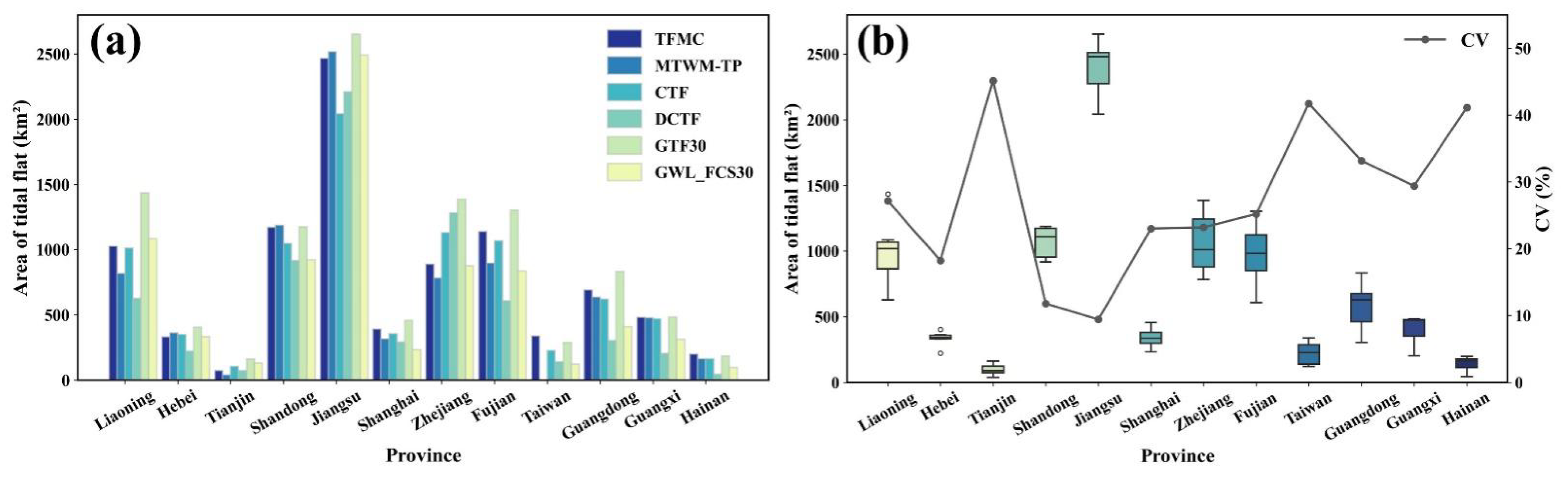

Figure 4 summarizes the 2020 provincial-scale estimates derived from the six independent products (TFMC, MTWM-TP, CTF, DCTF, GTF30, GWL_FCS30). The analysis reveals three statistically distinct macro-regional classifications: (1) Extensive mudflats. Jiangsu Province hosts >2 000 km² of tidal flats, accounting for >35 % of the national total. (2) Intermediate-complexity coasts. Liaoning, Shandong, Zhejiang and Fujian each contain ~1 000 km² of flats, controlled by convoluted shorelines and heterogeneous sediment regimes. (3) Restricted micro-tidal settings. Hebei, Tianjin and five other provinces retain <500 km², limited by short fetch, rocky headlands or heavily armoured coasts.

Inter-product agreement, quantified by the coefficient of variation (CV), exhibits a pronounced pattern (

Figure 4 b). High-consistency provinces (CV < 15 %) are Jiangsu (9.4 %) and Shandong (11.8 %), whereas Tianjin, Taiwan and Hainan display high dispersion (CV > 40 %). The remaining seven provinces fall within the moderate range (CV = 20–30 %).

4.2. Provincial Scale Area Rankings

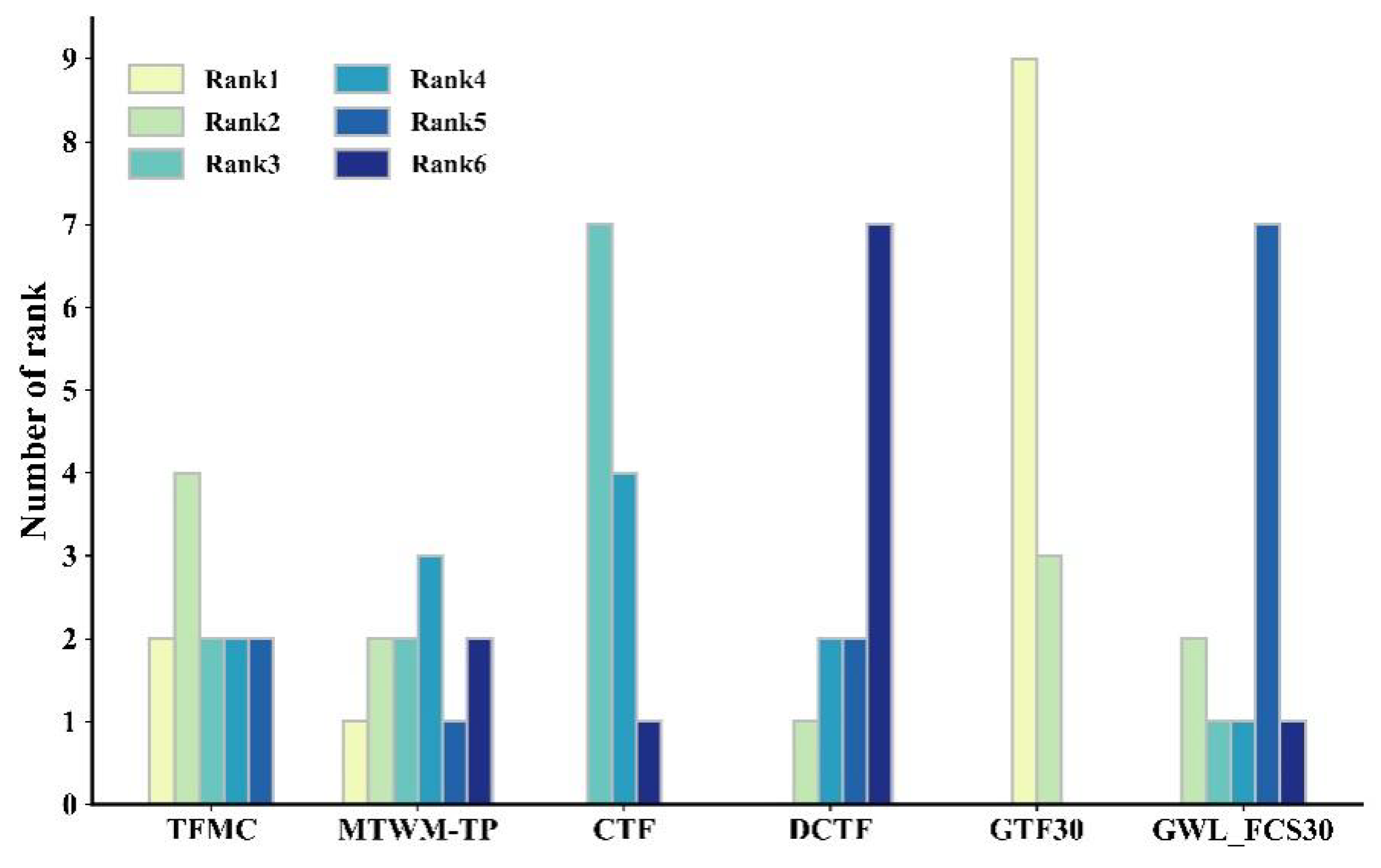

Figure 5 ranks the six products within each province (1=largest area). In combination with

Figure 4 a, three consistent patterns emerge.

GTF30 produced the largest estimates, ranking first in nine of the twelve provinces and second in the remaining three. The largest absolute departures occur in Liaoning, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong, with Liaoning exhibiting the most pronounced outlier.

DCTF and GWL_FCS30 were consistently low. DCTF is the smallest source in seven provinces; in Fujian it is approximately 200km² below the next-smallest estimate. GWL_FCS30 ranks fifth in seven provinces and is the minimum value for Shanghai and Taiwan.

CTF occupies the mid-range, ranking third or fourth in most provinces, but records the lowest value in Jiangsu. TFMC and MTWM-TP exhibit dispersed rankings without a clear directional bias. However, The areal estimates of TFMC, MTWM-TP, and GWL_FCS30 demonstrated consistent agreement (standard deviation is 113 km²), while GTF30, CTF, and DCTF produced significantly larger.

4.3. Spatial Agreement Assessment

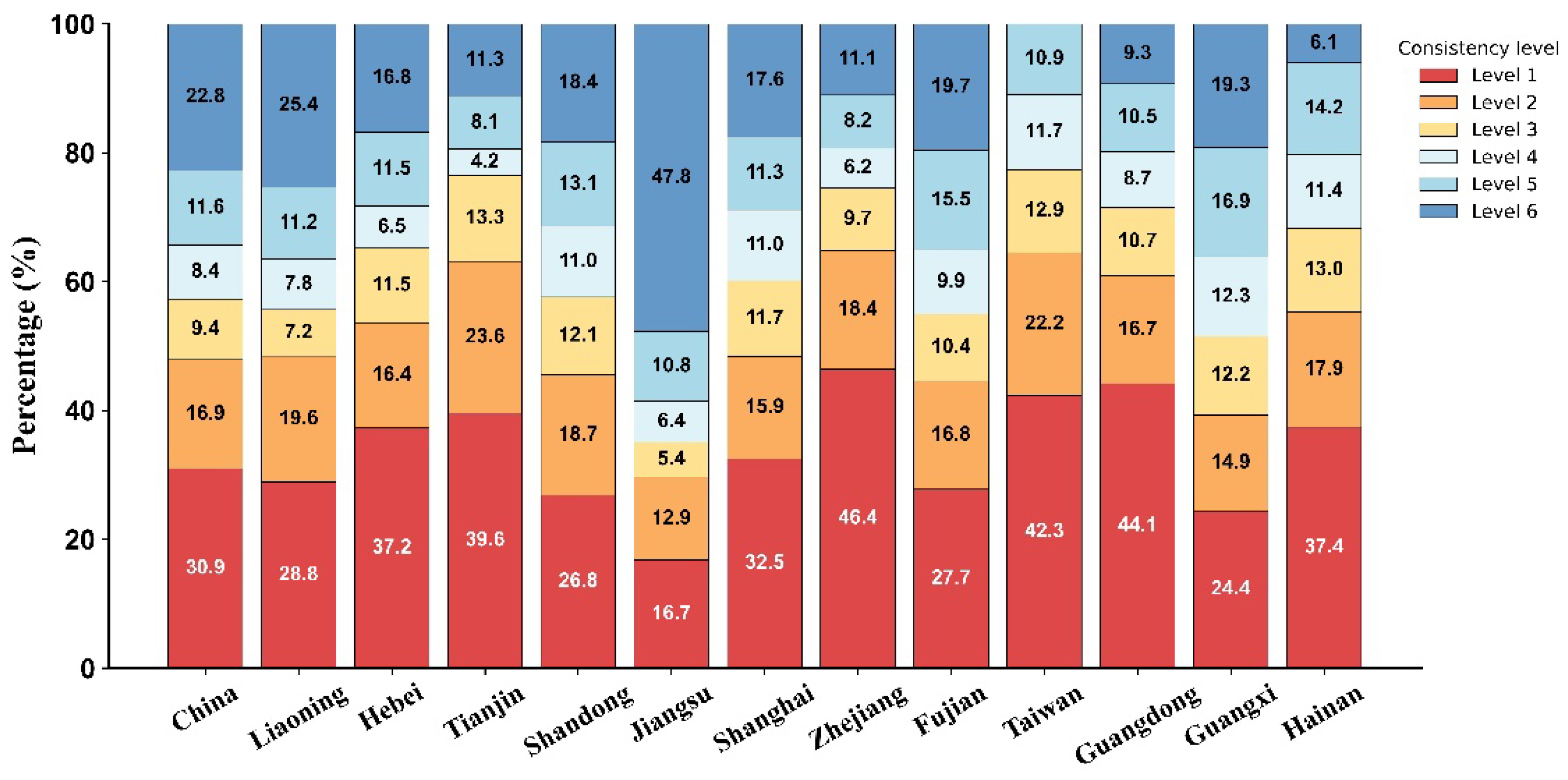

While aggregate area metrics reveal overall magnitude discrepancies, they do not capture spatial heterogeneity in dataset performance. We therefore quantified pixel-wise agreement among the six products by stacking their 10 m binary masks (1 = tidal flat, 0 = otherwise) and assigning each pixel an agreement level L∈{1, 2, …, 6}, where L = 6 indicates unanimous classification. Provincial frequency distributions of these levels are shown in

Figure 6.

Nationwide, spatial agreement is modest: 57.2 % of all tidal-flat pixels fall within low-agreement classes (L = 1–3), whereas only 42.8 % reach L ≥ 4. Perfect agreement (L = 6) is achieved for merely 22.8 % of pixels, underscoring substantial inter-product divergence. Note that low-agreement pixels (L = 1) do not necessarily denote commission or omission errors; they may also represent true tidal flats detected by some, but not all, algorithms.

Provincially, three distinct patterns emerge: (1) High agreement: Jiangsu exhibits near-maximum consensus, with 49.8 % of pixels at L = 6 and < 30 % at L = 1–2. (2) Moderate agreement: Liaoning, Shandong, Shanghai, Fujian and Guangxi show 35–45 % of pixels at L ≥ 4 and ≤ 50 % at L = 1–2. (3) Low agreement: Hebei, Tianjin, Zhejiang, Taiwan, Guangdong and Hainan display < 35 % of pixels at L ≥ 4; Guangdong and Hainan record only 9.3 % and 6.1 % at L = 6, respectively, while > 55 % of pixels fall within L = 1–2, indicating pronounced spatial discordance.

Figure 7 illustrates the spatial pattern of agreement levels among the six datasets. High-consistency pixels (level 6) are concentrated in well-developed tidal-flat regions, such as the Liao River estuary (

Figure 7 f) and the Jiangsu shoals, forming contiguous swaths. In contrast, turbid estuaries, like the Oujiang (

Figure 7 g), Jiaojiang and Hangzhou Bay, are dominated by low-consistency pixels (levels 1–3). The disagreement is particularly acute along the Oujiang boundary, where most pixels are assigned levels 1–3. Intermediate agreement dominates elsewhere, exemplified by the Nanliujiang estuary in Guangxi (

Figure 7 h), where agreement levels increase landward, revealing systematic positional uncertainty at the tidal-flat margin.

Taken together,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 demonstrate pronounced spatial heterogeneity in tidal-flat detection, arising from both methodological differences (data sources, algorithms and processing chains) and the intrinsic complexity of certain coastal environments. To quantify these differences, we computed the pairwise Spatial Consistency index (SC) at national and provincial scales (

Figure 8).

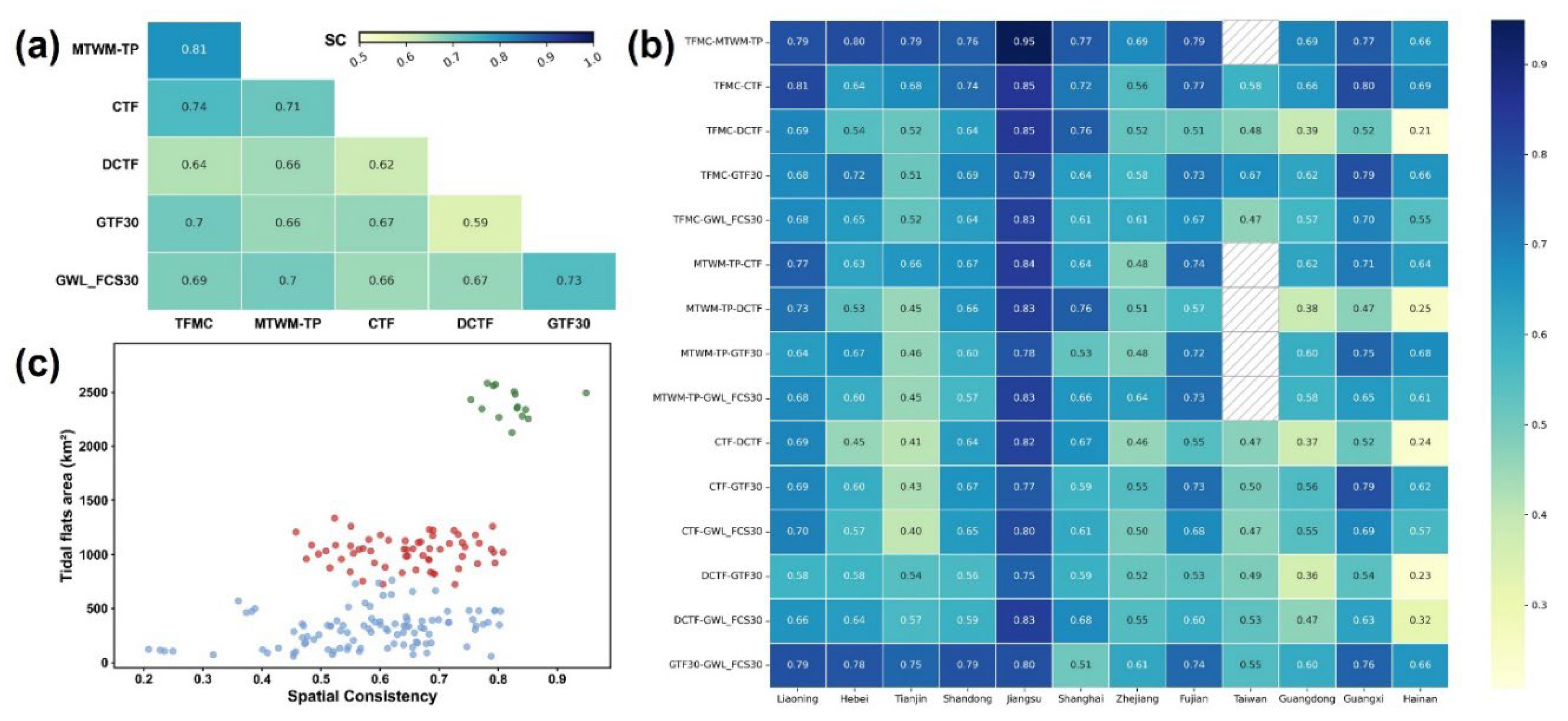

National-scale SC values (

Figure 8 a) range from 0.59 to 0.81. The highest agreement is observed between MTWM-TP and TFMC (SC = 0.81), whereas GTF30 and DCTF exhibit the lowest (SC = 0.59). Five additional pairs exceed 0.7: CTF–TFMC, CTF–MTWM-TP, GWL_FCS30–GTF30, GTF30–TFMC and GWL_FCS30–MTWM-TP. All remaining combinations fall within 0.60–0.70, except GTF30–DCTF. Notably, MTWM-TP, TFMC and CTF form a coherent cluster, whereas DCTF shows uniformly lower agreement with every other product, consistent with its systematic underestimation noted in

Section 4.1.

Provincial SC patterns (

Figure 8 b) further reveal strong regional modulation. MTWM-TP versus TFMC remains > 0.80 in all provinces, peaking in Jiangsu (0.94) and declining slightly in Zhejiang, Guangdong and Hainan. CTF–TFMC and GWL_FCS30–GTF30 follow similar spatial trends but register weaker performance in Taiwan. Conversely, DCTF paired with any dataset yields SC < 0.40 in Guangdong and Hainan, reaching a minimum of 0.21.

To examine the influence of tidal-flat extent on inter-product agreement, we plotted SC against the mean area of each provincial pair (

Figure 8 c). Provinces with large, continuous flats (green symbols) cluster at high SC values, whereas provinces with fragmented or narrow flats (blue and red symbols) exhibit greater scatter and lower SC. This confirms that extensive, morphologically simple flats enhance mapping stability, while small or complex flats amplify methodological differences.

In summary, Jiangsu displays the highest stability, combining the lowest CV (

Section 4.1) with the highest SC values, attributable to its broad, regular flats. Fujian, Guangxi and Liaoning also achieve high agreement. In contrast, Tianjin, Zhejiang, Taiwan, Guangdong and Hainan show pronounced discrepancies—high proportions of low-agreement pixels and SC values frequently < 0.4. These regional contrasts reflect both the geometric and sedimentological properties of the flats and the divergent sensor configurations, classification algorithms and thresholding strategies employed by each dataset; the latter are explored in detail in

Section 5.

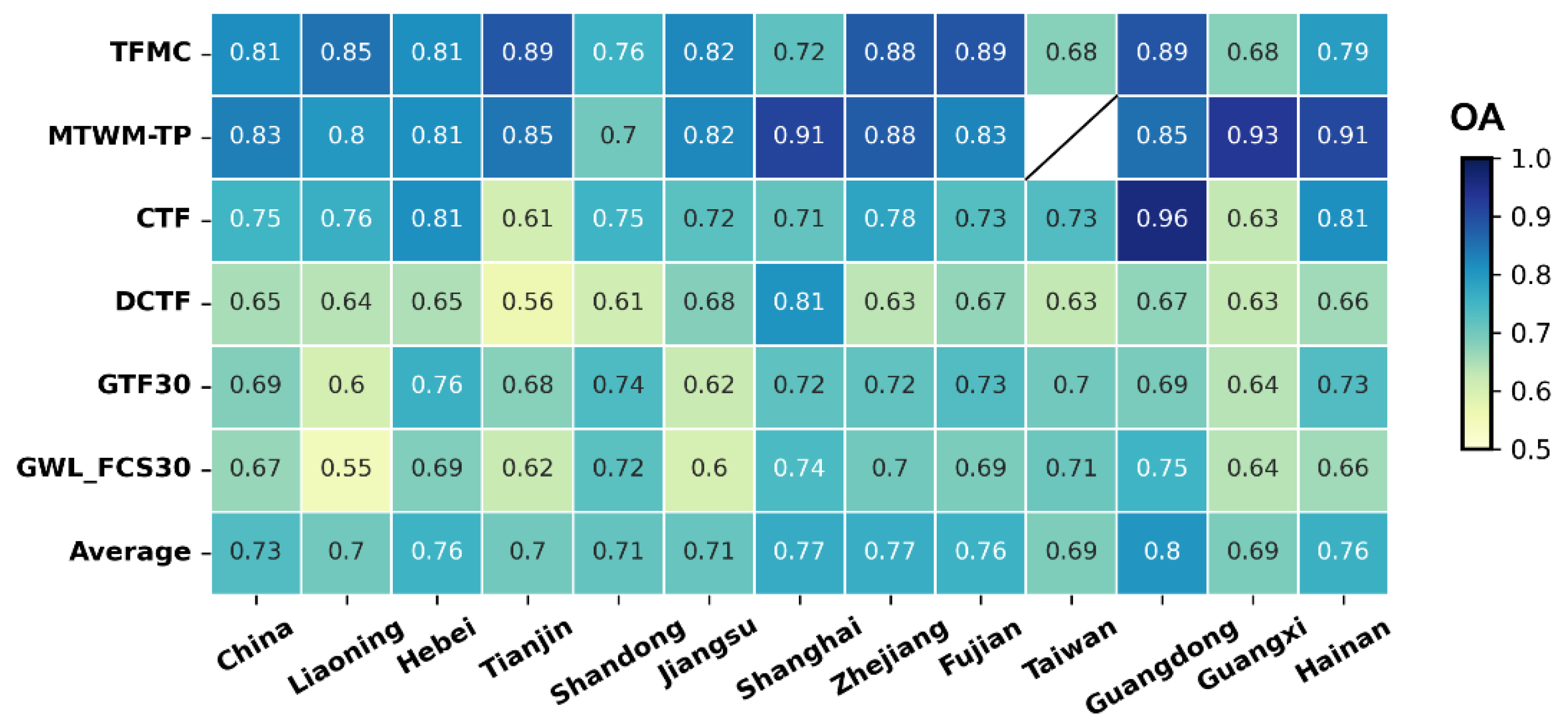

4.4. Accuracy Assessment using 2 550 Edge Validation Points

To quantify classification performance at the tidal-flat boundary, we generated an independent set of 2 550 validation points adjacent to seventeen tide gauges. Overall accuracies (OA) range from 0.65 to 0.85 (

Table 3). MTWM-TP achieves the highest OA (0.83), with high user’s and producer’s accuracies (UA and PA) for non-tidal-flat classes. It exceeds 0.80 in ten provinces and attains the top rank in five (

Figure 9). TFMC ranks second (OA = 0.81), its PA for tidal-flat pixels reaches 0.86, and provincial OA peaks at 0.89. CTF performs moderately (OA = 0.75), yet both UA and PA for tidal-flat pixels are comparatively low, indicating notable omission and commission errors, especially in Tianjin (OA = 0.61) and Guangxi (OA = 0.63).

DCTF, GWL_FCS30 and GTF30 yield lower accuracies (0.65, 0.67 and 0.69, respectively). DCTF’s PA for tidal-flat pixels is only 0.25, whereas PA for inland and water classes reaches 0.80 and 0.91, confirming systematic underestimation of tidal-flat extent—consistent with its low area estimates and SC values (

Section 4.1). GWL_FCS30 and GTF30 exhibit markedly lower PA for inland classes, implying widespread misclassification of aquaculture ponds and bare soil as tidal flats, thereby inflating area totals. GTF30 overestimates area in every province, and its reduced OA corroborates severe commission errors.

Differences from the nominal accuracies reported in the original datasets (

Table 1) stem primarily from the validation strategy employed. By focusing sampling on tidal-flat edges rather than using traditional within-class random points, our design is more sensitive to positional errors along boundaries. Edge validation shows that MTWM-TP and TFMC achieve robust boundary delineation, whereas the remaining datasets exhibit varying degrees of omission or commission.

5. Discussion

Inter-provincial differences in area, spatial consistency and edge accuracy (

Figure 4,

Figure 6 and

Figure 9) originate from systematic divergence along the entire processing chain: sensor choice, tidal-flat boundary constraints, spectral indices and classification algorithms jointly determine spatial fidelity and agreement. The following sections dissect these factors and propose actionable improvements.

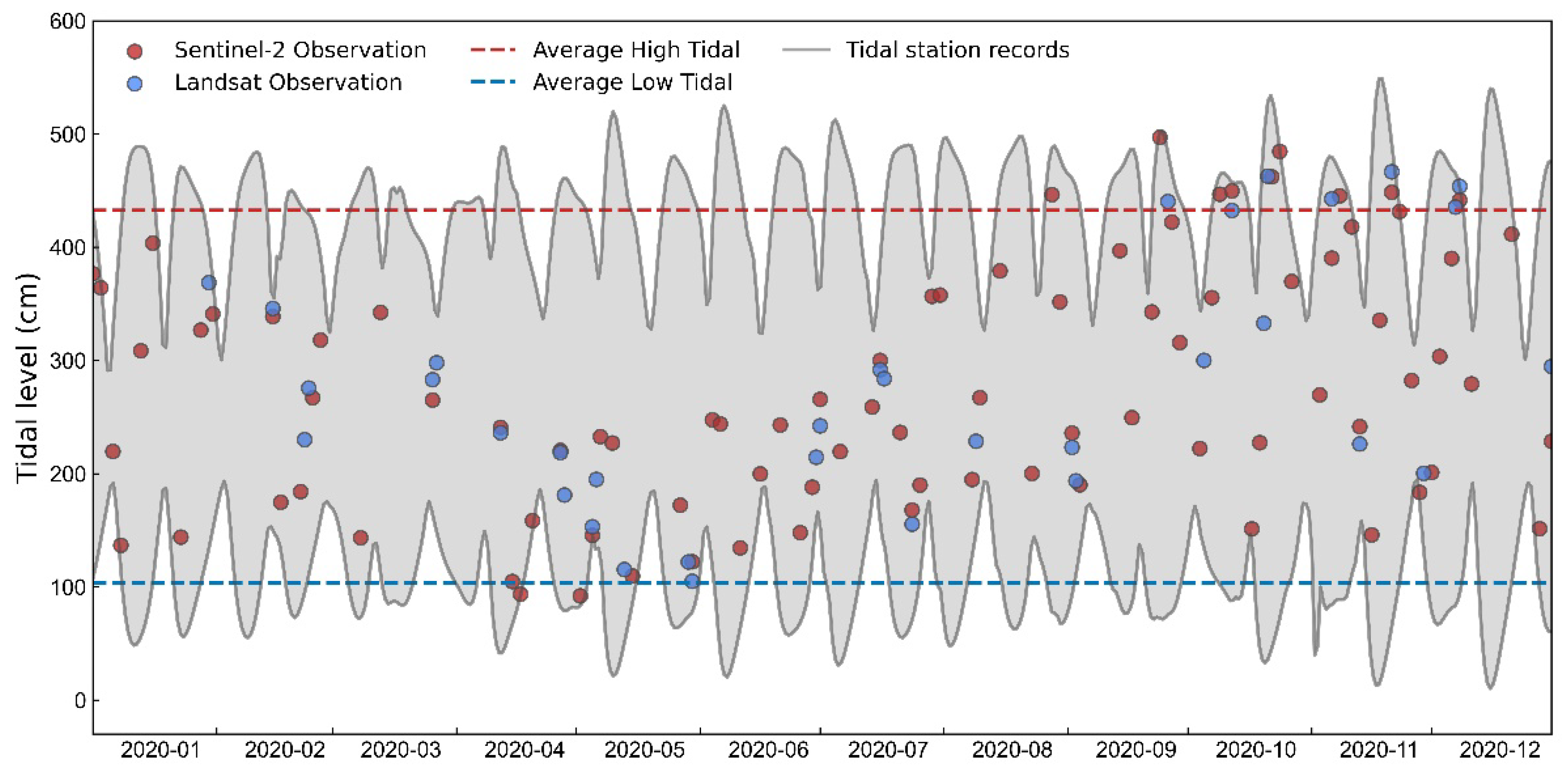

5.1. Sensor-Specific Impacts on Tidal-Flat Extraction

Landsat-8/9 and Sentinel-2 A/B are the most widely used optical sensors for large-area tidal-flat mapping. They differ markedly in spatial resolution (30 m vs 10 m), revisit interval (16 d vs 5 d; 3–5 d when Sentinel-2 A/B are combined) and spectral band configuration. The shorter revisit interval of Sentinel-2 significantly increases the probability of acquiring cloud-free images at low tide. In the Nanliujiang Estuary, Guangxi, for 2020, 87 Sentinel-2 scenes met a uniform cloud-cover threshold (≤ 60 %), 2.6 times the 34 available Landsat scenes (

Figure 10). Synchronizing these acquisitions with tide-gauge records shows that Sentinel-2 captured a minimum tide height of 92 cm, compared with 105 cm for Landsat.

Figure 11 demonstrates that Sentinel-2-based products (CTF, MTWM-TP, TFMC) fully delineate the exposed tidal-flat extent, whereas Landsat-based products (DCTF, GTF30, GWL_FCS30) systematically omit areas. Quantitative assessment reveals a 20%-60% larger tidal flat area extracted from Sentinel-2 data compared to Landsat in the Nanliu River estuary. Landsat missed approximately 60% of low-tide exposure windows in Beihai, resulting in systematic underestimation of tidal flat areas.

Nevertheless, Sentinel-2’s fixed overpass (around 10:30 in Beijing time) and cloud persistence still hinder annual minimum-tide coverage. Sub-meter imagery (e.g., GF-2, WorldView) with tasking capability offers a complementary source. A multi-sensor fusion strategy is therefore recommended to enhance both temporal completeness and spatial detail.

5.2. Suppression of Inland Interference Through Tidal-Flat Boundary Constraints

The spatiotemporal extent of tidal flats is strictly governed by cyclic tidal inundation; therefore, inland water bodies (aquaculture ponds, salt pans, and lakes) must be excluded during mapping to prevent systematic commission errors. TFMC, MTWM-TP, and CTF achieve this by deriving an annual maximum high-water shoreline from Sentinel-2 imagery and applying it as a hard boundary mask, effectively eliminating spectral look-alikes. In contrast, GWL_FCS30 and GTF30 omit this step and exhibited pronounced misclassification of aquaculture ponds as tidal flats in the Liaohe River Estuary (

Figure 12).

Quantitative assessment shows that incorporating the maximum high-water shoreline mask reduces inland commission errors by 35%–60% in the Liaohe Estuary. Conversely, unconstrained approaches (e.g., GTF30) yield a producer’s accuracy below 0.40 for aquaculture ponds, directly explaining their overestimated extents and low edge-validation accuracies. Given the widespread distribution of coastal aquaculture ponds in China [

27], integrating a maximum high-water shoreline mask is an essential step toward accurate, large-scale tidal-flat mapping.

5.3. Local Adaptability of Spectral Indices

A single water index cannot address the full range of tidal-flat remote-sensing requirements across complex coastal environments. In estuaries with high sediment loads and turbid waters (e.g., Oujiang Estuary and Hangzhou Bay), NDWI and NDVI frequently misclassify sediment-laden waters as tidal flats. Incorporating the short-wave-infrared (SWIR) band to construct mNDWI significantly reduces these false positives [

28,

29,

30] (

Figure 13 top). Consequently, datasets that rely on near-infrared indices—CTF, DCTF, and GTF30—exhibit extensive misclassification of turbid water in the Oujiang Estuary, whereas products integrating SWIR information (MWTM-TP and TFMC) provide more accurate and consistent classifications (

Figure 14). Similar errors occur in other turbid estuaries along the Zhejiang coast (Hangzhou Bay, Feiyun River Estuary, Aojiang River Estuary), leading to systematic overestimation of tidal-flat area and reduced spatial consistency for CTF, DCTF, and GTF30. Conversely, in gently sloping, high-moisture flats such as Laizhou Bay, mNDWI underestimates the tidal-flat extent due to strong SWIR absorption, whereas NDWI achieves more accurate land–water separation (

Figure 13, bottom).

Quantitative evaluation demonstrates a 35% reduction in mNDWI false positives within the turbid Oujiang Estuary, while NDWI supplementation accounted for 55% of the intertidal zone area undetected by mNDWI in the gentle region of Laizhou Bay.In summary, we recommend dynamically selecting or combining indices according to ambient turbidity and surface moisture levels to establish a scenario-adaptive spectral-index framework, thereby enhancing the robustness and transferability of tidal-flat remote-sensing products.

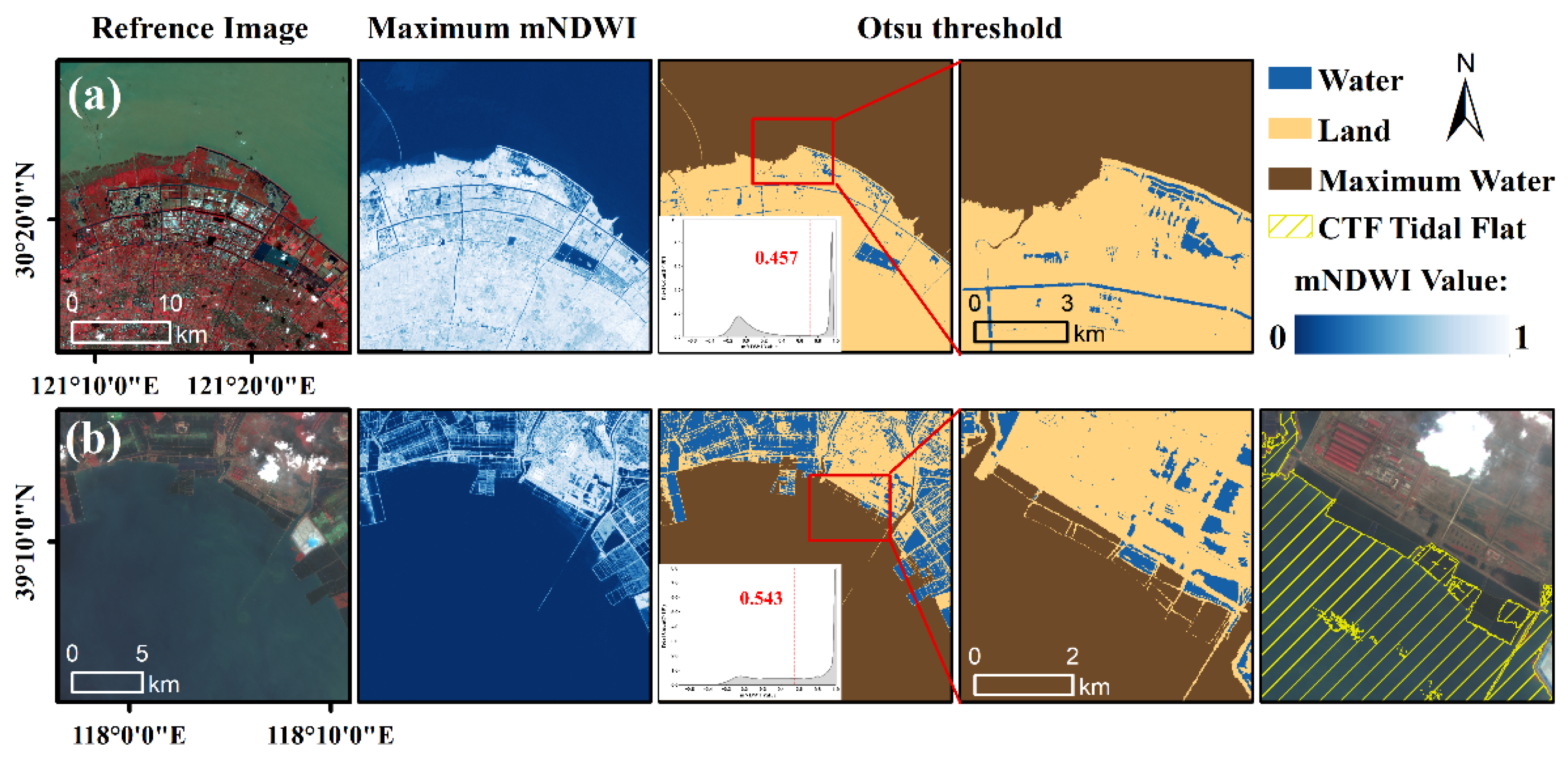

5.4. Robustness of Classification Approaches

Otsu’s method [

31] relies on a bimodal histogram assumption [

32], however, mixed pixels or class imbalance at tidal-flat margins frequently violate this premise and introduce threshold bias [

33]. In Caofeidian (Hebei), the mNDWI histogram is unimodal, so the automatically derived threshold fragments the shoreline and leading to erroneous segmentation of aquaculture ponds (

Figure 15 a). Conversely, Hangzhou Bay exhibits a well-defined bimodal histogram, enabling Otsu thresholds to achieve accurate land–water separation (

Figure 15 b).

Quantitative comparison shows that TFMC’s Otsu-based thresholding performs well in bimodal regions (Hangzhou Bay) but fails when the histogram is unimodal or dominated by mixed pixels (Caofeidian). MTWM-TP’s random-forest model maintains high overall accuracy (OA = 0.83) along complex edges, yet it requires extensive training data. Although the two approaches yield statistically similar results across the full domain, their applicability is complementary: thresholding is computationally efficient where histograms are well-behaved, whereas machine-learning models are more robust to mixed pixels and class imbalance at the cost of additional training samples.

Consequently, in heterogeneous transition zones such as tidal-flat margins, segmentation should integrate local histogram morphology, shape-adaptive thresholds, or post-classification machine-learning refinement to enhance robustness and spatial fidelity.

5.5. Methodological Recommendations

Future tidal-flat mapping should adopt a “multi-source – multi-index – multi-algorithm” framework that integrates the following components:

1. Multi-source synergy. Integrate the high temporal density of Sentinel-2 with Landsat’s long-term archive, complemented by high-resolution optical (e.g., GF-2, WorldView) and radar (e.g., Sentinel-1) observations to maximize spatial detail, temporal coverage, and all-weather capability.

2. Adaptive spectral indices. Dynamically select NDWI or mNDWI according to locally derived turbidity thresholds.

3. Hybrid classification. Employ rule-based thresholds for clear land–water interfaces and machine-learning (RF/CNN) classifiers for mixed-pixel zones, while constraining the domain with an annual maximum high-water shoreline.

Implementing this framework at 10 m resolution is expected to deliver seamless, nationwide annual updates and provide high-confidence data for coastal-zone management.

6. Conclusions

Tidal flats are critical ecotones between terrestrial and marine systems, underpinning biodiversity, carbon sequestration and coastal protection. Accurate mapping of these habitats is therefore essential for resource management, ecological conservation and global-change research. We conducted a systematic inter-comparison of six 2020 national-scale tidal-flat datasets (GTF30, GWL_FCS30, MTWM-TP, DCTF, CTF and TFMC) using three independent metrics: area estimates, spatial consistency and edge-based classification accuracy.

1. Substantial discrepancies exist among datasets in tidal-flat area, spatial patterns and boundary delineation. While broad agreement is achieved over typical mudflats (e.g., the Jiangsu shoals), pronounced divergence emerges along complex coastlines and turbid estuaries (e.g., Oujiang Estuary), indicating large spatial uncertainty.

2. Performance is dataset-specific, with systematic underestimation (DCTF) or overestimation (GTF30). Edge validation reveals that MTWM-TP (OA = 0.83) and TFMC (OA = 0.81) are the most accurate, whereas CTF (OA = 0.75) is moderate and DCTF (OA = 0.65), GWL_FCS30 (OA = 0.67) and GTF30 (OA = 0.69) suffer from severe misclassification.

3. Cross-product differences stem primarily from four technical dimensions: (1) spatiotemporal resolution of imagery, (2) boundary control strategies, (3) local adaptability of water indices, and (4) robustness of classification algorithms. Relying on a single sensor, index or segmentation approach is insufficient for China’s diverse coastal environments.

Future improvements should: (1) fuse multi-source optical and radar imagery to increase low-tide observations while maintaining automation; (2) develop dynamic combinations of spectral indices tailored to regional turbidity and geomorphology; and (3) refine thresholding algorithms by integrating image features and prior knowledge for enhanced boundary delineation. These findings provide a scientific basis for dataset selection and algorithm optimization, supporting precise coastal ecosystem management and sustainable development.

Funding

This research was funded by The Global Change and Air-Sea Interaction Project of China, grant number #JC-YGFW-YGJZ.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Jia M., Zhang Z., Chen Y., Hu Z., and Zhang X. for providing the datasets (CTF, MTWM-TP, TFMC, DCTF, GTF30, and GWL_FCS30) used in this study. We also extend our appreciation to the National Marine Science Data Center for supplying the tide records and to the National Platform for Common Geospatial Information Services for providing the administrative boundary data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Dyer, K.; Christie, M.; Wright, E., The classification of intertidal mudflats. Cont. Shelf Res. 2000, 20 (10-11), 1039-1060. [CrossRef]

- Murray, N. J.; Phinn, S. R.; DeWitt, M., et al., The global distribution and trajectory of tidal flats. Nature 2019, 565 (7738), 222-225. [CrossRef]

- Murray, N. J.; Worthington, T. A.; Bunting, P., et al., High-resolution mapping of losses and gains of Earth’s tidal wetlands. Sci. 2022, 376 (6594), 744-749. [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, R., et al., Mapping changes in coastlines and tidal flats in developing islands using the full time series of Landsat images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 239, 111665. [CrossRef]

- Loke, L. H.; Todd, P. A., Structural complexity and component type increase intertidal biodiversity independently of area. Ecology 2016, 97 (2), 383-393. [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, J. H.; Ashton, A. D.; Edmonds, D. A., et al., Global-scale human impact on delta morphology has led to net land area gain. Nature 2020, 577 (7791), 514-518. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jia, A.; Song, X., et al., Extraction and spatiotemporal evolution analysis of tidal flats in the Bohai Rim during 1984–2019 based on remote sensing. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33 (1), 76-98. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C. M.; Losada, I. J.; Hendriks, I. E., et al., The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3 (11), 961-968. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, N.; Li, Y., et al., Sub-continental-scale mapping of tidal wetland composition for East Asia: A novel algorithm integrating satellite tide-level and phenological features. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112799. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z., et al., Mapping tidal flats with Landsat 8 images and google earth engine: A case study of the China’s eastern coastal zone circa 2015. Remote Sens. 2019, 11 (8), 924. [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J., et al., China's wetlands loss to urban expansion. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29 (8), 2644-2657. [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z., et al., Rapid invasion of Spartina alterniflora in the coastal zone of mainland China: Spatiotemporal patterns and human prevention. Sensors 2019, 19 (10), 2308. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Tian, B., et al., Tide2Topo: A new method for mapping intertidal topography accurately in complex estuaries and bays with time-series Sentinel-2 images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 200, 55-72. [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Wang, Z.; Mao, D., et al., Rapid, robust, and automated mapping of tidal flats in China using time series Sentinel-2 images and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 255, 112285. [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S. K., The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17 (7), 1425-1432. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27 (14), 3025-3033. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, J., et al., Automated Mapping of Global 30-m Tidal Flats Using Time-Series Landsat Imagery: Algorithm and Products. J Remote Sens. 2023, 3, 0091. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, J.; Song, J., et al., Developing a new index with time series Sentinel-2 for accurate tidal flats mapping in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178037. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Li, P.; Li, Z., et al., Mapping tidal flats of the Bohai and Yellow seas using time series Sentinel-2 images and Google earth engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14 (8), 1789. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, T., et al., GWL_FCS30: global 30 m wetland map with fine classification system using multi-sourced and time-series remote sensing imagery in 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2022, 2022, 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zou, Z., et al., Mapping coastal wetlands of China using time series Landsat images in 2018 and Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 163, 312-326. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yin, Y., et al., Tidal flats dataset covers coastal region in north of 18°N latitude of China (1989–2020). J. Glob. Change. Data. Discovery. 2022, 6 (1), 125-132. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Qin, C.-Z.; Teng, J., Mapping large-area tidal flats without the dependence on tidal elevations: A case study of Southern China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 256-270. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Feng, M.; Jiang, H., et al., Validation of Land Cover Maps in China Using a Sampling-Based Labeling Approach. Remote Sens. 2015, 7 (8), 10589-10606. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zou, Z., et al., Tracking annual changes of coastal tidal flats in China during 1986–2016 through analyses of Landsat images with Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 238, 110987. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Feng, X., et al., Accuracy assessment of seven global land cover datasets over China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 125, 156-173. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y., et al., Rapid expansion of coastal aquaculture ponds in China from Landsat observations during 1984–2016. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 82, 101902. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Matsushita, B.; Pahlevan, N., et al., Remotely estimating total suspended solids concentration in clear to extremely turbid waters using a novel semi-analytical method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112386. [CrossRef]

- Surisetty, V. V. A. K.; Sahay, A.; Ramakrishnan, R., et al., Improved turbidity estimates in complex inland waters using combined NIR–SWIR atmospheric correction approach for Landsat 8 OLI data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39 (21), 7463-7482. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-L.; Ho, C.-R.; Huang, C.-C., et al., Hyperspectral sensing for turbid water quality monitoring in freshwater rivers: empirical relationship between reflectance and turbidity and total solids. Sensors 2014, 14 (12), 22670-22688. [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N., A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1975, 11 (285-296), 23-27. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, M. C.; Martinez, J.-M.; Peña-Luque, S., Automatic water detection from multidimensional hierarchical clustering for Sentinel-2 images and a comparison with Level 2A processors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 253, 112209. [CrossRef]

- Donchyts, G.; Schellekens, J.; Winsemius, H., et al., A 30 m resolution surface water mask including estimation of positional and thematic differences using landsat 8, srtm and openstreetmap: a case study in the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. Remote Sens. 2016, 8 (5), 386. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Spatial extent of tidal flat study area along China's coastline with 5 km landward and 30 km seaward buffer zones.

Figure 1.

Spatial extent of tidal flat study area along China's coastline with 5 km landward and 30 km seaward buffer zones.

Figure 2.

Research Framework for comparative analysis of tidal flat datasets.

Figure 2.

Research Framework for comparative analysis of tidal flat datasets.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of validation points (tide gauges and edge samples,a: Liaohe River Estuary, Minjiang River Estuary, Chaozhou Port).

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of validation points (tide gauges and edge samples,a: Liaohe River Estuary, Minjiang River Estuary, Chaozhou Port).

Figure 4.

Provincial-scale tidal flat area statistics and inter-dataset discrepancies along China's coast.

Figure 4.

Provincial-scale tidal flat area statistics and inter-dataset discrepancies along China's coast.

Figure 5.

Dataset ranking of tidal flat areas by province (descending order) along China's coast.

Figure 5.

Dataset ranking of tidal flat areas by province (descending order) along China's coast.

Figure 6.

Percentage distribution of spatial consistency levels among tidal flat datasets by province.

Figure 6.

Percentage distribution of spatial consistency levels among tidal flat datasets by province.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of inter-dataset consistency levels for tidal flat mapping.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of inter-dataset consistency levels for tidal flat mapping.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of pairwise spatial consistency (SC values) among tidal flat datasets.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of pairwise spatial consistency (SC values) among tidal flat datasets.

Figure 9.

Inter-provincial comparison of overall accuracy (OA) for tidal flat datasets using edge validation points.

Figure 9.

Inter-provincial comparison of overall accuracy (OA) for tidal flat datasets using edge validation points.

Figure 10.

Tidal elevation time-series and Landsat/Sentinel-2 image acquisition windows at Nanliujiang Estuary.

Figure 10.

Tidal elevation time-series and Landsat/Sentinel-2 image acquisition windows at Nanliujiang Estuary.

Figure 11.

Comparative spatial distributions of tidal flat datasets during low tide at Nanliujiang Estuary.

Figure 11.

Comparative spatial distributions of tidal flat datasets during low tide at Nanliujiang Estuary.

Figure 12.

Tidal flat dataset comparisons at Liaohe River Estuary (with/without high-water boundary constraints).

Figure 12.

Tidal flat dataset comparisons at Liaohe River Estuary (with/without high-water boundary constraints).

Figure 13.

Segmentation performance comparison of NDWI vs. mNDWI at turbid Oujiang Estuary and clear Laizhou Bay.

Figure 13.

Segmentation performance comparison of NDWI vs. mNDWI at turbid Oujiang Estuary and clear Laizhou Bay.

Figure 14.

Misclassification patterns in tidal flat datasets due to highly turbid waters at Oujiang Estuary.

Figure 14.

Misclassification patterns in tidal flat datasets due to highly turbid waters at Oujiang Estuary.

Figure 15.

mNDWI threshold segmentation comparison: unimodal histogram at Caofeidian vs. bimodal histogram at Hangzhou Bay.

Figure 15.

mNDWI threshold segmentation comparison: unimodal histogram at Caofeidian vs. bimodal histogram at Hangzhou Bay.

Table 1.

Technical parameter comparison of tidal flat datasets along China's coast (2020).

Table 1.

Technical parameter comparison of tidal flat datasets along China's coast (2020).

| Dataset |

Time |

Range |

Data sources |

Resolution |

Core index/band |

Nominal accuracy |

Class |

| GTF30 |

2000-2022 |

Global |

Landsat |

30m |

Landsat's six bands, LTideI, NDVI, mNDWI, LSWI |

90.34% |

Tidal flat |

| GWL_FCS30 |

2020 |

Global |

Sentinel-1 &Landsat |

30m |

Landsat's six bands, NDVI, mNDWI, EVI, LSWI |

86.44% |

Tidal flats, Salt marshes, Mangroves, Inland wetlands |

| MTWM-TP |

2020 |

Esat Asia |

Sentinel-2 |

10m |

Sentinel-2’s twelve bands, NDVI, NDWI |

97.02% |

Tidal flats, Salt marshes, Mangroves |

| CTF |

2020 |

China |

Sentinel-2 |

10m |

mNDWI, NDVI |

95% |

Tidal flats |

| DCTF |

1989-2020 |

China |

Landsat |

30m |

NDVI, mNDWI, LSWI, BSI, EVI, MSAVI, NDBI |

90.84% |

Tidal flats, Salt marshes |

| TFMC |

2020 |

China |

Sentinel-2 |

10m |

mNDWI、TWDI |

97% |

Tidal flats |

Table 2.

Tide gauge station metadata and low-tide image parameters for validation.

Table 2.

Tide gauge station metadata and low-tide image parameters for validation.

| Province |

Tidal station |

Image sources |

Overpass times |

Tidal height(cm) |

Chart datum (cm) |

| Liaoning |

Laobeihekou |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/5/6 10:56:26 |

51 |

-209 |

| Daludao |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/1/19 10:46:27 |

152 |

-332 |

| Hebei |

Caofeidian |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/4/11 10:56:55 |

60 |

-178 |

| Tianjin |

Tanggu |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/5/24 11:06:59 |

94 |

-241 |

| Shandong |

Wanwangoukou |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/7/8 11:07:13 |

39 |

-130 |

| Dongying |

Landsat 8 |

2020/3/14 10:41:49 |

62 |

-100 |

| Jiangsu |

Jianggang |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/4/28 10:48:31 |

97 |

-301 |

| Lvsi |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/3/14 10:48:46 |

135 |

-310 |

| Shanghai |

Zhongjun |

Landsat 8 |

2020/5/12 10:24:24 |

107 |

-225 |

| Zhejiang |

Qimengang |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/8/13 10:49:37 |

295 |

-379 |

| Damendao |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/11/11 10:40:11 |

184 |

-363 |

| Fujian |

Minjiangkou |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/8/26 10:50:41 |

140 |

-353 |

| Quanzhou |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/8/26 10:50:59 |

133 |

-366 |

| Taiwan |

Magong |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/11/21 10:41:08 |

52 |

-160 |

| Guangdong |

Chaozhougang |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/12/7 11:01:11 |

59 |

-101 |

| Hainan |

Xinying |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/5/2 11:22:29 |

78 |

-205 |

| Guangxi |

Tieshangang |

Sentinel-2 |

2020/5/2 11:22:17 |

174 |

-255 |

Table 3.

Confusion matrix of edge validation points for tidal flat datasets (OA: Overall Accuracy, PA: Producer's Accuracy, UA: User's Accuracy).

Table 3.

Confusion matrix of edge validation points for tidal flat datasets (OA: Overall Accuracy, PA: Producer's Accuracy, UA: User's Accuracy).

| Dataset |

Class |

TF |

Non-TF |

Use. acc. |

Ove. acc. |

| Inland |

Water |

| TFMC |

TF |

732 |

159 |

195 |

0.67 |

0.81 |

| Non-TF |

118 |

691 |

655 |

0.92 |

|

| Pro. acc. |

0.86 |

0.81 |

0.77 |

|

|

| MTWM-TP |

TF |

662 |

53 |

211 |

0.71 |

0.83 |

| Non-TF |

138 |

747 |

589 |

0.91 |

|

| Pro. acc. |

0.83 |

0.93 |

0.74 |

|

|

| CTF |

TF |

472 |

83 |

173 |

0.65 |

0.75 |

| Non-TF |

378 |

767 |

677 |

0.80 |

|

| Pro. acc. |

0.56 |

0.90 |

0.80 |

|

|

| DCTF |

TF |

209 |

168 |

80 |

0.46 |

0.65 |

| Non-TF |

641 |

682 |

770 |

0.69 |

|

| Pro. acc. |

0.25 |

0.80 |

0.91 |

|

|

| GTF30 |

TF |

502 |

309 |

131 |

0.53 |

0.69 |

| Non-TF |

348 |

541 |

719 |

0.78 |

|

| Pro. acc. |

0.59 |

0.64 |

0.85 |

|

|

| GWL_FCS30 |

TF |

257 |

204 |

54 |

0.50 |

0.67 |

| Non-TF |

593 |

646 |

796 |

0.71 |

|

| Pro. acc. |

0.30 |

0.76 |

0.94 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).