1. Introduction

The hospital-at-home (HaH) model provides hospital-grade acute care in the patient’s home, and has been adapted in western and eastern countries [

1,

2,

3,

4]. HaH has proven effective in managing a range of acute medical conditions—including pneumonia, heart failure, COPD, urinary tract infections, and skin and soft tissue infections—by delivering timely, hospital-level care without the need for admission. [

4,

5,

6].

Successful HaH care hinges on deploying point-of-care services such as mobile diagnostics, real-time remote monitoring, intravenous treatments, and virtual consultations to replicate hospital capabilities at home [

6,

7]. Among available diagnostic tools, point-of-care ultrasonography (PoCUS) plays a central role [

8]. While PoCUS complements other imaging modalities in hospital settings, it often functions as the primary—or even sole—diagnostic tool in HaH care [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Evidence supports the use of PoCUS in managing COVID-19 pneumonia, guiding the development of comparable home-based care strategies [

14,

15] for disease preparedness and mitigate health inequality [

16,

17]. Previously, we reviewed the techniques and key sonographic patterns for diagnosing pneumonia using PoCUS in home care settings and highlighted essential confounders and pathological mimickers that must be recognized (

Table 1) [

18,

19]. This review further explores key questions regarding the prognostic value, synchronicity, and unexpected benefits of pneumonia management using PoCUS within the HaH model.

Table 1.

Ten essential questions to adress before using point-of-care ultrasonography to diagnose and manage pneumonia in the hospital-at-home model.

Table 1.

Ten essential questions to adress before using point-of-care ultrasonography to diagnose and manage pneumonia in the hospital-at-home model.

| 1. What ultrasound techniques are essential for diagnosing pneumonia? |

| 2. What are the ultrasound patterns associated with pneumonia? |

| 3. Do different settings or etiologies of pneumonia influence the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography? |

| 4. Do pulmonary comorbidities affect the accuracy of ultrasound diagnosis for pneumonia? |

| 5. Do other differential diagnoses mimic the ultrasound patterns of pneumonia? |

| 6. Do ultrasound findings correlate with pneumonia severity? |

| 7. Do initial ultrasound findings associated with pneumonia hold prognostic value? |

| 8. Do the ultrasound patterns improve in accordance with pneumonia recovery? |

| 9. Is ultrasound superior to chest x-ray for diagnosing pneumonia? |

| 10. Does ultrasonography lead to overdiagnosis of pneumonia? |

2. Question 7: Do Initial Ultrasound Findings Associated with Pneumonia Hold Prognostic Value?

During the treatment of infectious diseases, some imaging modalities are often used as a one-time cross-sectional assessment, with limited or no follow-up imaging thereafter. For pneumonia, a typical one-time cross-sectional imaging is computed tomography (CT). A single center study compared patients who were diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) using chest x-ray and CT in the emergency department. With a non-randomized retrospective analysis, it found that CT improved diagnosis consistency for CAP, with a trend for lower hospital length-of-stay around 2 days, but did not affect ICU admission and in-hospital mortality [

20].

PoCUS offers advantages in safety and repeatability. However, it is often performed only once during the entire treatment course—typically at enrollment—serving primarily as a triage tool to assess whether a pneumonia patient is suitable for out-of-hospital care. The additional prognostic insights provided by PoCUS are therefore essential to avoid assigning complex or difficult-to-treat pneumonia cases to home-based care.

Table 2 summarises reg flag signs of lung ultrasound (LUS) patterns which may be seen in patients with pneumonia.

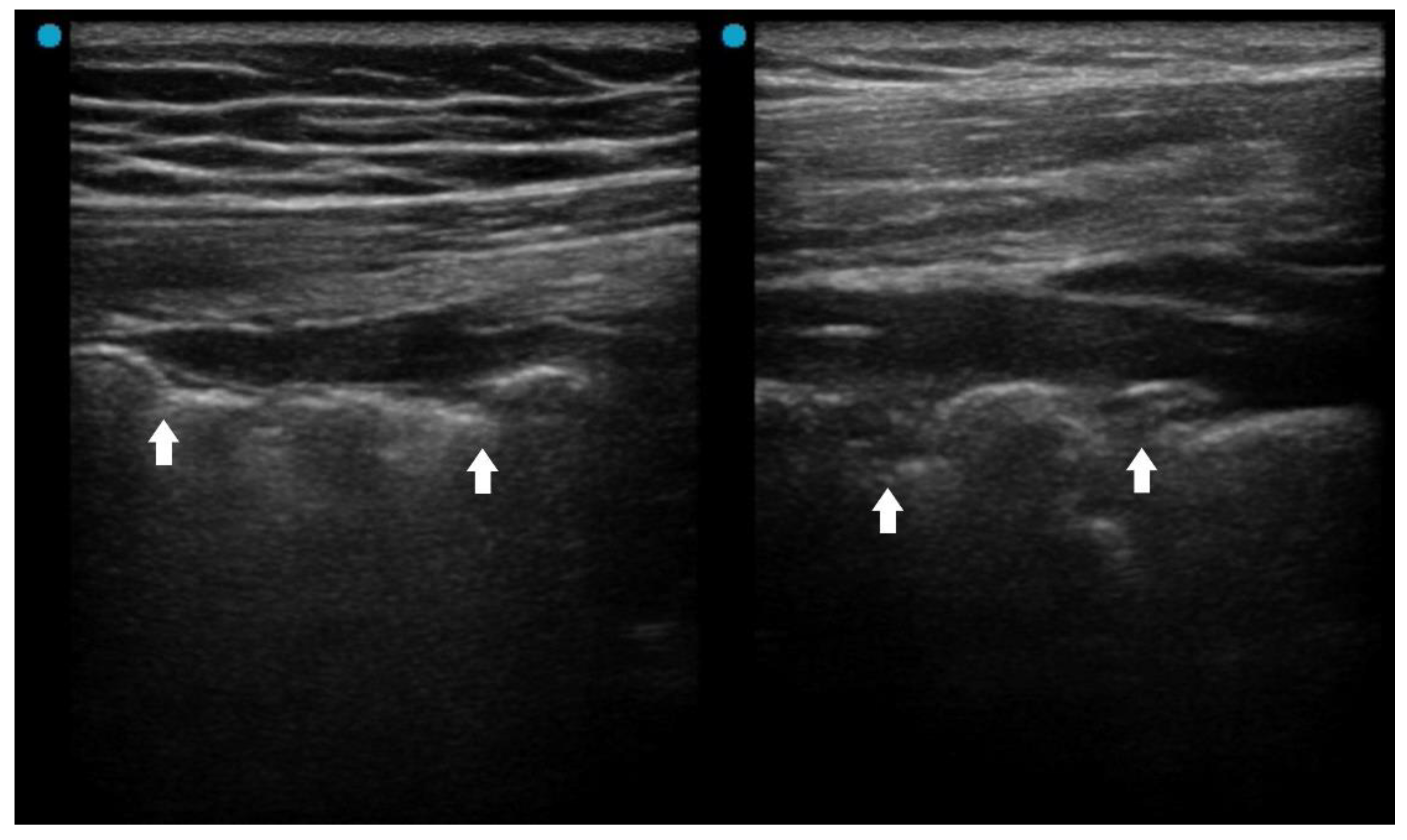

2.1. Red Flag Signs Related to ARDS

Several LUS signs, based on previous studies, indicate a more severe pneumonia, such as acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). A landmark study sough to differentiate acute pulmonary edema (APE) from ARDS by LUS. Although B-lines (alveolar-interstitial syndrome) prevailed 100% in both APE and ARDS, absence or reduction of the pleural gliding (sliding) was observed in 100% of patients with ARDS and in 0% of patients with APE. ‘Spared areas’ within confluent B-lines were observed in 100% of patients with ARDS and in 0% of patients with APE [

21]. In addition, pleural line abnormalities, including irregularity or thickening, were observed in 100% of patients with ALI/ARDS (

Figure 1). These signs are classified as level B of evidence with strong recommendation in a landmark LUS guideline [

22].

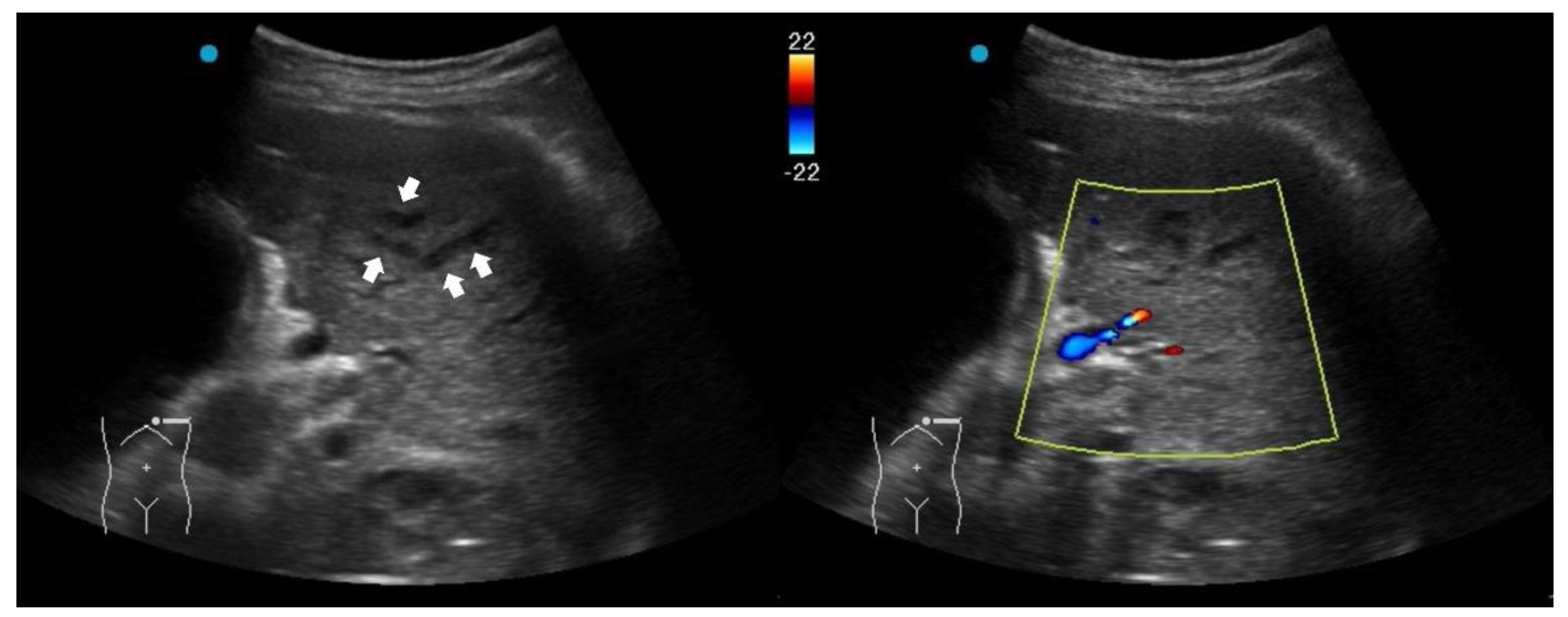

2.2. Red Flag Signs Related to Complicated Pneumonia

Fluid bronchogram is originally described as a sign on CT [

23]. It is also described in post-obstructive pneumonia in ultrasonography, identified as anechoic tubular structures with hyperechoic walls but without color Doppler signals (

Figure 2) [

24,

25].

Post-obstructive pneumonia with a fluid bronchogram usually reflects complete bronchial obstruction, making the consolidation refractory to antibiotic therapy alone.

The ultrasonographic appearance of pneumonia in children can be used for adults [

22]. A study investigated pediatric hospitalized patients found that children with a uncomplicated CAP presented an air, arboriform, superficial and dynamic bronchogram, as opposed to complicated CAP which had an air and liquid bronchogram, deep, fixed [

26]. Another pediatric study reported that fluid bronchogram, multifocal involvement, and pleural effusion were associated with adverse outcomes, including longer hospital stay, ICU admission, and tube thoracotomy in hospitalized CAP children [

27].

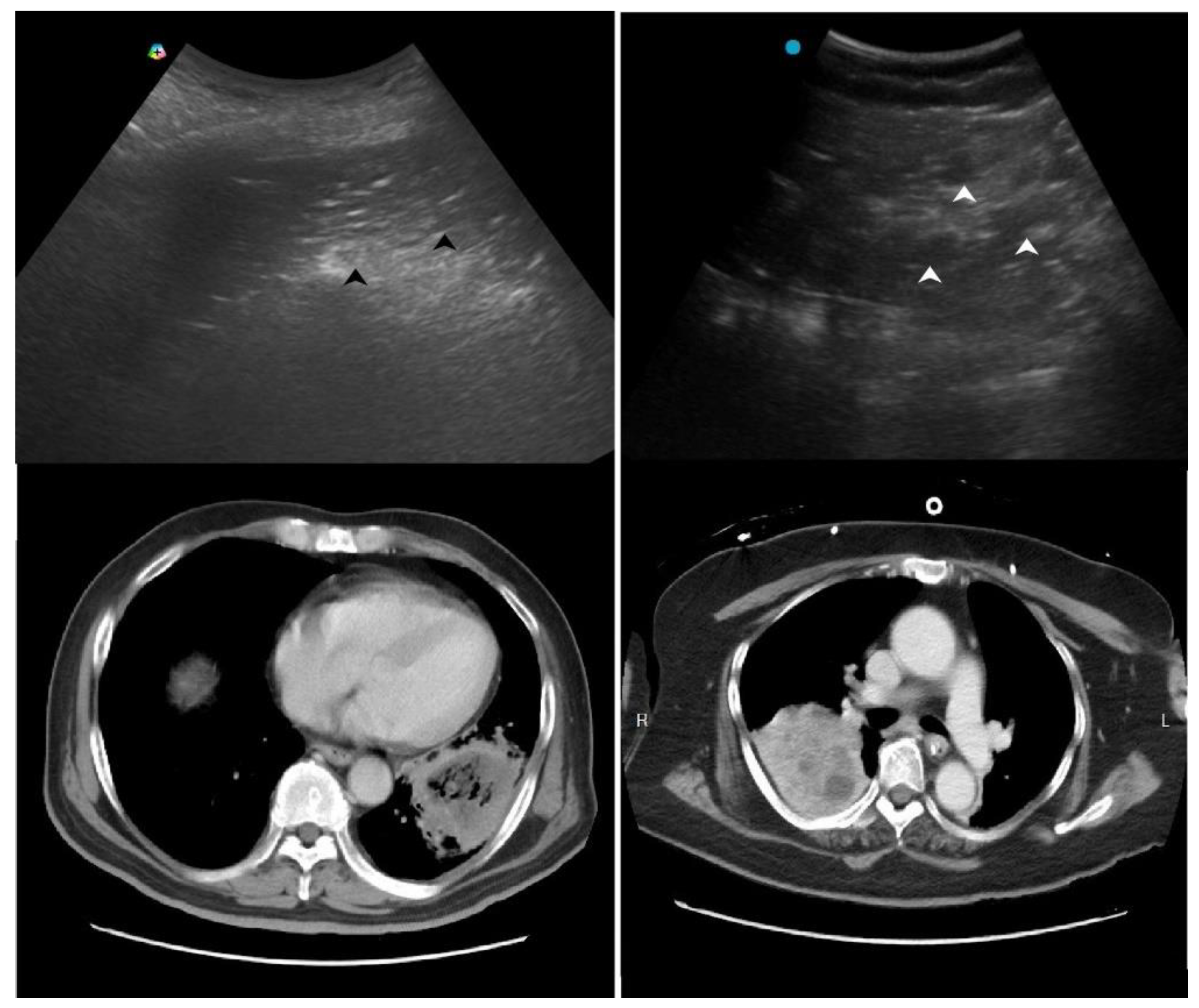

2.3. Red Flag Signs Related to Necrotizing Pneumonia

A study retrospectively reviewed 236 children with CAP. The perfusion of subpleural consolidation was classified into normal perfusion (homogenously distributed tree-like vascularity), decreased perfusion (less than 50% of an area with typical tree-like vascularity), and poor perfusion (no recognizable color Doppler flow) [

28]. Poor perfusion had a positive predictive value of 100% and 81.8% for all necrotizing pneumonias and severe necrotizing pneumonias, respectively. It was also associated with an increased risk of pneumatocele formation and the subsequent requirement for surgical lung resection. However, the absence of color Doppler signals within consolidations has been scarcely studied in adult CAP and warrants further investigation in future research.

Another LUS sign of necrotizing pneumonia in children was the presence of a heterogeneous hypoechoic consolidation containing more hypoechoic confluent lesions [

29]. These hypoechoic lesions were thought corresponding to necrotic cavities. Adult studies have shown that the presence of micro-abscesses or hypoechoic areas within consolidations may suggest necrotizing changes, prompting further confirmation with a repetitive CT in suspicious patients (

Figure 3) [

30,

31].

2.4. Other Red Flag Signs

For a long time, researchers have seldom incorporated radiologic findings into prognostic models of CAP. The Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), developed in 1997 to guide hospitalization decisions for CAP in emergency and outpatient settings, included only one radiologic parameter—pleural effusion—among its 20 scoring items [

32]. A PSI score of 71–90 corresponds to class III, indicating approximately twice the odds of hospitalization and increased mortality compared to classes I and II. For example, a male patient over 65 years old presenting with pneumonia and pleural effusion would be classified as class III. In such cases, the presence of pleural effusion detected by LUS serves as a red flag. A systematic review reported the incidence of COVID-19-related pleural effusions was 7.3% among 47 observational studies [

33]. Pleural effusions were commonly observed in critically ill patients and had Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome. COVID-19 patients with pleural effusion, compared to patients without pleural effusion, had worse gas exchange and higher mortality in another report [

34]. Another study found that CAP patients with pleural effusion were more likely to be older, have comorbid neurological diseases, and have a lasting fever [

35]. Notably, pleural effusion is common in patients with heart failure or renal dysfunction and is associated with increased in-hospital mortality [

36]. Since PoCUS as an imaging modality has higher diagnostic accuracy than CXR in detecting pleural effusion,[

37] its presence or new onset should be considered a red flag during CAP management.

The PSI is often considered too complex to calculate, prompting some researchers to propose simplified versions [

38]. Recently, the CURB-65 score has been widely used for CAP [

39]. Developed in 2003, CURB-65 is a simpler tool than PSI; however, it does not incorporate any radiologic findings.

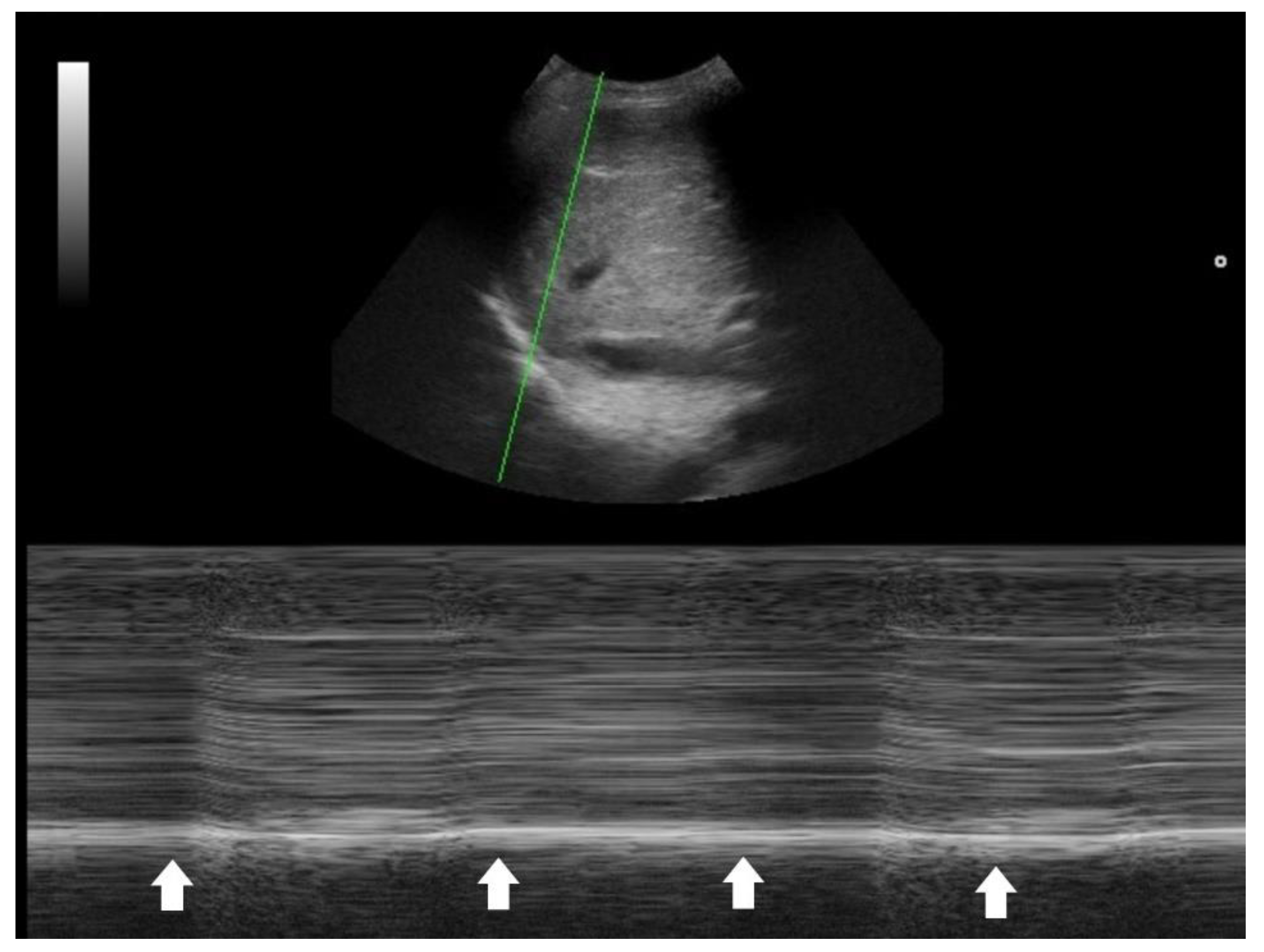

One key clinical implication of PSI and CURB-65 is the prognostic value of co-morbidities, physical signs, and laboratory data in CAP. PoCUS serves as a powerful tool to detect occult co-morbidities—such as heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and liver disease—that are incorporated into the PSI score [

32]. Laboratory items in PSI and CURB-65 aim to identify signs of sepsis. In this context, PoCUS can help confirm a hyperdynamic left ventricle in patients with tachycardia and/or hypotension [

40,

41,

42], or a hyperdynamic diaphragm in tachypneic patients as a compensatory response [

43,

44]. Suboptimal diaphragmatic excursion in a patient is an ominous sign, indicating poor respiratory endurance and limited reserve (

Figure 4) [

45,

46,

47,

48].

3. Question 8: Do the Ultrasound Patterns Improve in Accordance with Pneumonia Recovery?

Ultrasound characteristics of the lung like consolidations, B-lines, pleural effusions, and pleural line disease typically decrease in size, number, and extent as pneumonia recovers. Serial examinations for both community-acquired and COVID-19 pneumonia indicate that consolidations may regress or resolve, B-lines become lessened, and pleural effusions become decreased and resolve as days and treatment and clinical status become successful [

49,

50,

51]. Most studies confirmed that the course of pneumonia was comparable using X-ray and LUS. In the case of COVID-19 pneumonia, confluent B-lines wane after the acute phase, whereas irregular pleura and subpleural consolidations resolved later [

50]. Residual LUS abnormalities can last for months. A study of 96 COVID-19 pneumonia found that only 20.8% had complete resolution on LUS at 1 month, which rose to 68.7% at 3 months [

51]. Reports in ICU showed LUS findings were significantly decreased by ICU discharge [

52,

53]. The use of LUS has been demonstrated to be a powerful tool for monitoring the evolution of COVID-19 during the pandemic [

54,

55].

In pediatric populations, LUS correlates well with clinical improvement and can reliably monitor disease progression and resolution [

56]. In summary, improvement in LUS patterns generally parallels the resolution of clinical symptoms in pneumonia recovery, making lung ultrasound a reliable tool for monitoring disease course and guiding follow-up.

The observation that confluent B-lines and pleural effusions often resolve earlier, whereas subpleural consolidations and pleural line irregularities tend to persist longer—particularly in patients with more severe disease—is clinically meaningful. Recognizing which LUS findings typically improve first is crucial for clinicians HaH care, as early reversibility of specific ultrasound features may serve as a reliable indicator of favorable response to antimicrobial therapy. Conversely, an increase in the amount of pleural effusion may indicate a suboptimal or delayed response to therapy. In patients with prolonged complications after pneumonia such as COVID-19, LUS findings were associated with persistent respiratory symptoms one month after the initial LUS evaluation [

57]. It plays an important role in facilitating effective doctor–patient communication within the HaH setting.

Finally, although LUS is a valuable modality for monitoring pneumonia, it has inherent limitations, including incomplete visualization of all pulmonary regions. Therefore, protocols incorporating more than eight scanning zones are recommended to improve coverage as studies showed that higher acquisition zones rendered higher sensitivity and specificity [

58,

59]. Moreover, the technique’s operator dependency poses challenges for longitudinal comparisons, particularly when examinations are performed by different clinicians. Questions such as whether “LUS images can be reliably compared across operators” remain insufficiently addressed. To minimize interrater variability, standardized image acquisition protocols and structured training programs for clinicians involved in HaH care should be implemented. Nevertheless, studies evaluating such standardization remain limited in the current literature.

4. Question 9: Is Ultrasound Superior to Chest X-Ray for Diagnosing Pneumonia?

The limited sensitivity of chest radiography in the diagnosis of pneumonia has been well described. Lung ultrasound is more sensitive than chest radiography for detecting pneumonia and its complications, and serial ultrasound examinations can accurately track pulmonary reaeration and the effectiveness of treatment [

60]. Nevertheless, variations across patient populations and clinical contexts warrant individualized consideration.

4.1. Pediatrics

Investigations which conducted in the pediatric ICU directly compared the diagnostic performance of lung ultrasound (LUS) and chest radiography (CXR), using thoracic computed tomography (CT) as the reference standard [

61,

62]. A total of 84 hemithoraces were assessed by all three modalities. For consolidation, CXR demonstrated the sensitivity, specificity, and overall diagnostic accuracy of 38%, 89%, and 49%, respectively, whereas LUS achieved 100%, 78%, and 95%. For interstitial syndrome, the corresponding values were 46%, 80%, and 69% for CXR versus 94%, 93%, and 94% for LUS. For pleural effusion, CXR reported 65%, 81%, and 86%, whereas LUS demonstrated perfect performance at 100%, 100%, and 100%. This observation has been corroborated by another study in ER demonstrating that clinicians can accurately diagnose pneumonia in children and young adults using point-of-care ultrasonography, with high specificity [

63]. Another study found that the diagnostic accuracy for childhood pneumonia was greater on LUS than chest x-ray (area under the curve, 0.94 and 0.76, respectively), and LUS missed only 4.5% of the pneumonia cases while chest x-ray missed 21% [

64].

Lung ultrasound demonstrates higher diagnostic accuracy for pneumonia in pediatric patients compared to adult patients. In children, pooled sensitivity consistently ranges from 94% to 96% and specificity from 90% to 96%indicating excellent performance [

65,

66]. In adults, meta-analyses report slightly lower sensitivity (typically 88–94%) and specificity (78–96%), with AUC values around 0.93 [

67,

68]. Several factors contribute to this difference. Pediatric patients generally have thinner chest walls and less subcutaneous tissue, facilitating better ultrasound penetration and visualization of lung pathology

Collectively, these findings indicate that LUS consistently outperformed CXR across all major thoracic pathologies, particularly for consolidation and pleural effusion detection. Therefore, strong advocacy has emerged for incorporating ultrasound earlier in the diagnostic imaging algorithm for suspected pneumonia in children [

69]. Wherever institutional infrastructure permits, ultrasound may precede, complement, or even replace chest radiography.

4.2. Adults

Studies comparing chest radiography and lung ultrasound (LUS) should be contextualized according to specific clinical settings, as adult populations often present with greater complexity than pediatric cases. For instance, in postoperative thoracic surgical patients, chest radiography failed to detect findings observed on ultrasonography in 24% of examinations, and notably missed 60% of pleural effusions that were identified by LUS [

70]. In the emergency department setting, LUS markedly reduced diagnostic uncertainty for pneumonia from 73% to 14%, with most of the initial uncertainty attributable to chest radiography findings [

71].

A systematic review included 17 studies found that LUS in the hands of the non-imaging specialists, such as emergency physicians, internal medicine physicians, intensivists, demonstrated high sensitivities (≥0.91) and specificities (0.57 to 1.00) in diagnosing pneumonia [

72]. While chest x-ray interpretation skills vary among non-radiologists, the study observed no substantial difference in diagnostic accuracy between low- and high-performing groups.

When combined with other point-of-care tests, lung ultrasound may enhance clinicians’ confidence in making antibiotic prescribing decisions [

73]. This strategy appears particularly promising within the HaH care model.

4.3. Special Contexts

A recent study conducted in Viet Nam, a setting with a high incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis, investigated the use of LUS for the diagnosis and monitoring of pneumonia [

74]. LUS demonstrated higher sensitivity than chest radiography (CXR)—96.0% versus 82.8%—and comparable specificity of 64.9% versus 54.1%. The moderate specificity of LUS was largely attributable to sonographically similar conditions, particularly pulmonary TB, which was present in 5.1% of patients. Although LUS is highly sensitive for diagnosing pneumonia, its specificity may be limited in TB-endemic regions. Similar limitations were observed in contexts such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where viral pneumonias were more prevalent than those of bacterial origin and the decision must be individualized [

75].

Patients with obesity, thick chest walls, subcutaneous emphysema, restricted chest wall access (from dressings, prosthetic material, or dermatologic conditions) are prone to reduced diagnostic accuracy with LUS for pneumonia. In these populations, ultrasound beam penetration and transmission are impaired, limiting visualization of the lung parenchyma and hindering detection of consolidations. The American College of Radiology specifically notes that LUS has limited utility in such contexts [

76].

5. Question 10: Does Ultrasonography Lead to Overdiagnosis of Pneumonia?

Lung ultrasound has consistently demonstrated higher sensitivity than chest radiography in various clinical applications, frequently detecting radiographically occult abnormalities that might otherwise go unrecognized. However, a highly sensitive diagnostic tool may also detect minor or clinically insignificant pathological findings. It remains uncertain whether all patients with suspected lower respiratory tract infection and LUS-detected but radiographically occult consolidations truly require antibiotic therapy [

77].

Overdiagnosis of pneumonia leads to concerns of unnecessary antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance [

78]. The potential for overtreatment of such radio-occult conditions warrants systematic evaluation through dedicated clinical trials. However, challenges of the robustness of clinical trials for PoCUS remain. First, gold standards used to investigate diagnostic accuracy of LUS for pneumonia are sometimes not appropriate. Second, given the high operator-dependent variability of PoCUS, pre-study hands-on workshops are recommended to standardize sonographic competency and minimize bias [

79].

A recommended approach to minimize the overdiagnosis of pneumonia by LUS is to integrate ultrasound findings with the clinical context and complementary diagnostic information from other modalities. It is important to emphasize that ultrasound assessment should not be confined to the lungs; for instance, in reports of decision-making for COVID-19 patients, age, oxygen saturation, the inferior vena cava, pleural space, and pericardium were also incorporated [

80,

81]. We appreciate the American College of Physicians guideline’s concept of “parallel use,” in which PoCUS complements rather than replaces standard diagnostic pathways to enhance diagnostic accuracy, while “replacement” refers to substituting one or more tests entirely with PoCUS [

82]. POCUS used in parallel with standard diagnostics can improve sensitivity and reduce missed cases, representing the most common clinical scenario. Yet, most studies have assessed POCUS as a replacement for chest radiography, citing its simplicity, safety, and potential accuracy advantages [

83]. We advocate that future researchers avoid using replacement or head-to-head designs when evaluating the role of PoCUS. Emphasizing its parallel, integrative use will yield more clinically meaningful and generalizable insights.

6. Conclusions

Effective diagnosis and management of pneumonia in hospital-at-home programs require clinicians to master the identification of sonographic patterns of pneumonia, supported by the appropriate selection of equipment and scanning techniques. In the first part of our review, we summarize current practices for diagnosing pneumonia by LUS, focusing on different protocols in the literature. In the second part of our review, we summarize the evidence supporting the repetitive application of PoCUS throughout the clinical course of pneumonia. Recognizing differential diagnoses of LUS patterns, along with awareness of potential pitfalls and confounders, is essential for improving diagnostic accuracy and delivering person-centered care in HaH programs. In the third and final part of review, we present current evidence showing that LUS findings can provide prognostic insights during the early phase of pneumonia and exhibit synchrony with disease progression or recovery. Finally, we emphasize that clinicians should not rely solely on LUS findings when evaluating patients with pneumonia in home-based settings, as we are ultimately treating patients—not diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nin-Chieh. Hsu. and Chia-Hao. Hsu.; writing—original draft preparation, Nin-Chieh. Hsu.; writing—review and editing, Yu-Feng. Lin., Hung-Bin. Tsai.; supervision, Chia-Hao. Hsu.; image editing and revision, Charles Liao.; funding acquisition, Nin-Chieh. Hsu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (TW) (NSTC 114-2410-H-002-068).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance from Taiwan Association of Hospital Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mirón-Rubio M, González-Ramallo V, Estrada-Cuxart O, et al. Intravenous antimicrobial therapy in the hospital-at-home setting: data from the Spanish Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy Registry. Future Microbiol. 2016;11(3):375-390.

- van Goor, H. M. R., de Hond, T. A. P., van Loon, K., Breteler, M. J. M., Kalkman, C. J., & Kaasjager, K. A. H. Designing a Virtual Hospital-at-Home Intervention for Patients with Infectious Diseases: A Data-Driven Approach. J Clin Med. 2024,13,977.

- Ko SQ, Goh J, Tay YK, et al. Treating acutely ill patients at home: Data from Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022;51(7):392-399.

- Hakkarainen T, Lahelma M, Rahkonen T, et al. Cost comparison analysis of continuous versus intermittent antimicrobial therapy infusions in inpatient and outpatient care: real-world data from Finland. BMJ Open. 2024;14(9):e085242.

- Candel FJ, Salavert M, Basaras M, et al. Ten Issues for Updating in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: An Expert Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(21):6864.

- Nouvenne, A., Ticinesi, A., Siniscalchi, C., Rendo, M., Cerundolo, N., Parise, A., Castaldo, G., Chiussi, G., Carrassi, R., Guerra, A., & Meschi, T. The Multidisciplinary Mobile Unit (MMU) Program Bringing Hospital Specialist Geriatric Competencies at Home: A Feasible Alternative to Admission in Older Patients with Urgent Complaints. J Clin Med. 2024,13,2720.

- Zychlinski, N., Fluss, R., Goldberg, Y., Zubli, D., Barkai, G., Zimlichman, E., & Segal, G. Tele-medicine controlled hospital at home is associated with better outcomes than hospital stay. PLoS One. 2024,19, e0309077.

- Salton F, Kette S, Confalonieri P, et al. Clinical Evaluation of the ButterfLife Device for Simultaneous Multiparameter Telemonitoring in Hospital and Home Settings. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(12):3115..

- Kirkpatrick AW, McKee JL, Couperus K, Colombo CJ. Patient Self-Performed Point-of-Care Ultrasound: Using Communication Technologies to Empower Patient Self-Care. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(11):2884.

- Xirouchaki, N., Bolaki, M., Psarologakis, C., Pediaditis, E., Proklou, A., Papadakis, E., Kondili, E., & Georgopoulos, D. Thoracic ultrasound use in hospitalized and ambulatory adult patients: a quantitative picture. Ultrasound J. 2024, 16, 11.

- Duggan, N. M., Jowkar, N., Ma, I. W. Y., Schulwolf, S., Selame, L. A., Fischetti, C. E., Kapur, T., & Goldsmith, A. J. Novice-performed point-of-care ultrasound for home-based imaging. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 20461.

- Lin J, Bellinger R, Shedd A, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Airway Evaluation and Management: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(9):1541.

- Ganchi FA, Hardcastle TC. Role of Point-of-Care Diagnostics in Lower- and Middle-Income Countries and Austere Environments. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(11):1941.

- Dell’Aquila, P., Raimondo, P., Racanelli, V., De Luca, P., De Matteis, S., Pistone, A., Melodia, R., Crudele, L., Lomazzo, D., Solimando, A. G., Moschetta, A., Vacca, A., Grasso, S., Procacci, V., Orso, D., & Vetrugno, L. Integrated lung ultrasound score for early clinical decision-making in patients with COVID-19: results and implications. Ultrasound J. 2022, 14, 21.

- Fabuel Ortega, P., Almendros Lafuente, N., Cánovas García, S., Martínez Gálvez, L., & González-Vidal, A. The correlation between point-of-care ultrasound and digital tomosynthesis when used with suspected COVID-19 pneumonia patients in primary care. Ultrasound J. 2022, 14, 11.

- Leach M, MacGregor H, Ripoll S, Scoones I, Wilkinson A. Rethinking Disease Preparedness: Incertitude and the Politics of Knowledge. Crit Public Health. 2022;32(1):82-96.

- Kajeepeta S, Bruzelius E, Ho JZ, Prins SJ. Policing the pandemic: Estimating spatial and racialized inequities in New York City police enforcement of COVID-19 mandates. Crit Public Health. 2022;32(1):56-67.

- Hsu NC, Lin YF, Tsai HB, Huang TY, Hsu CH. Ten Questions on Using Lung Ultrasonography to Diagnose and Manage Pneumonia in the Hospital-at-Home Model: Part I-Techniques and Patterns. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(24):2799.

- 第二篇.

- Claessens YE, Berthier F, Baqué-Juston M, et al. Early chest CT-scan in emergency patients affected by community-acquired pneumonia is associated with improved diagnosis consistency. Eur J Emerg Med. 2022;29(6):417-420.

- Copetti R, Soldati G, Copetti P. Chest sonography: a useful tool to differentiate acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema from acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2008;6:16.

- Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(4):577-591.

- Shin MS, Ho KJ. CT fluid bronchogram: observation in postobstructive pulmonary consolidation. Clin Imaging. 1992;16(2):109-113.

- Reissig A, Copetti R. Lung ultrasound in community-acquired pneumonia and in interstitial lung diseases. Respiration 2014; 87(3): 179–189.

- Kedia Y, Gupta N, Kumar R. Ultrasonographic view of fluid bronchogram secondary to endobronchial obstruction: A case report. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2025;28(1):e12418.

- Musolino AM, Tomà P, Supino MC, et al. Lung ultrasound features of children with complicated and noncomplicated community acquired pneumonia: A prospective study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(9):1479-1486.

- Chen IC, Lin MY, Liu YC, et al. The role of transthoracic ultrasonography in predicting the outcome of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173343.

- Lai SH, Wong KS, Liao SL. Value of Lung Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis and Outcome Prediction of Pediatric Community-Acquired Pneumonia with Necrotizing Change. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130082.

- Carrard J, Bacher S, Rochat-Guignard I, et al. Necrotizing pneumonia in children: Chest computed tomography vs. lung ultrasound. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:898402.

- Yang PC, Luh KT, Chang DB, Yu CJ, Kuo SH, Wu HD. Ultrasonographic evaluation of pulmonary consolidation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(3):757-762.

- Lichtenstein D, Peyrouset O. Is lung ultrasound superior to CT? The example of a CT occult necrotizing pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(2):334-335.

- Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(4):243-250.

- Chong WH, Saha BK, Conuel E, Chopra A. The incidence of pleural effusion in COVID-19 pneumonia: State-of-the-art review. Heart Lung. 2021;50(4):481-490.

- Cappelli S, Casto E, Lomi M, et al. Pleural Effusion in COVID-19 Pneumonia: Clinical and Prognostic Implications-An Observational, Retrospective Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):1049.

- Zhong M, Ni R, Zhang H, Sun Y. Analysis of clinical characteristics and risk factors of community-acquired pneumonia complicated by parapneumonic pleural effusion in elderly patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):355.

- Wang D, Niu Y, Ma Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of non-malignant pleural effusions in hospitalised patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2024;14(7):e077980.

- Zaki HA, Albaroudi B, Shaban EE, et al. Advancement in pleura effusion diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of point-of-care ultrasound versus radiographic thoracic imaging. Ultrasound J. 2024;16(1):3.

- Chang SC, Grunkemeier GL, Goldman JD, et al. A simplified pneumonia severity index (PSI) for clinical outcome prediction in COVID-19. PLoS One. 2024;19(5):e0303899.

- Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58(5):377-382.

- Jones AE, Craddock PA, Tayal VS, Kline JA. Diagnostic accuracy of left ventricular function for identifying sepsis among emergency department patients with nontraumatic symptomatic undifferentiated hypotension. Shock. 2005;24(6):513-517.

- Vieillard-Baron A, Prin S, Chergui K, Dubourg O, Jardin F. Hemodynamic instability in sepsis: bedside assessment by Doppler echocardiography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(11):1270-1276.

- Gotsman I, Leibowitz D, Keren A, Amir O, Zwas DR. Echocardiographic Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of the Hyperdynamic Heart: A ‘Super-Normal’ Heart is not a Normal Heart. Am J Cardiol. 2023;187:119-126.

- Hsu CH, Hsu NC. Elderly Man With Fall Incident. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;83(2):168-169.

- Boussuges A, Finance J, Chaumet G, Brégeon F. Diaphragmatic motion recorded by M-mode ultrasonography: limits of normality. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00714-2020.

- Hayward S, Cardinael C, Tait C, Reid M, McCarthy A. Exploring the adoption of diaphragm and lung ultrasound (DLUS) by physiotherapists, physical therapists, and respiratory therapists: an updated scoping review. Ultrasound J. 2025;17(1):9.

- Skaarup SH, Juhl-Olsen P, Grundahl AS, Løgstrup BB. Replacement of fluoroscopy by ultrasonography in the evaluation of hemidiaphragm function, an exploratory prospective study. Ultrasound J. 2024;16(1):1.

- Neto Silva I, Duarte JA, Perret A, et al. Diaphragm dysfunction and peripheral muscle wasting in septic shock patients: Exploring their relationship over time using ultrasound technology (the MUSiShock protocol). PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0266174.

- Sartini S, Ferrari L, Cutuli O, et al. The Role of Pocus in Acute Respiratory Failure: A Narrative Review on Airway and Breathing Assessment. J Clin Med. 2024;13(3):750.

- Reissig A, Kroegel C. Sonographic diagnosis and follow-up of pneumonia: a prospective study. Respiration. 2007;74(5):537-547.

- Burkert J, Jarman R, Deol P. Evolution of Lung Abnormalities on Lung Ultrasound in Recovery From COVID-19 Disease-A Prospective, Longitudinal Observational Cohort Study. J Ultrasound Med. 2023;42(1):147-159.

- Hernández-Píriz A, Tung-Chen Y, Jiménez-Virumbrales D, et al. Importance of Lung Ultrasound Follow-Up in Patients Who Had Recovered from Coronavirus Disease 2019: Results from a Prospective Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(14):3196.

- Alharthy A, Faqihi F, Abuhamdah M, et al. Prospective Longitudinal Evaluation of Point-of-Care Lung Ultrasound in Critically Ill Patients With Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40(3):443-456.

- Barnikel M, Alig AHS, Anton S, et al. Follow-up lung ultrasound to monitor lung failure in COVID-19 ICU patients. PLoS One. 2022;17(7):e0271411.

- He L, Sun Y, Sheng W, Yao Q. Diagnostic performance of lung ultrasound for transient tachypnea of the newborn: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248827.

- Hoffmann T, Bulla P, Jödicke L, et al. Can follow up lung ultrasound in Coronavirus Disease-19 patients indicate clinical outcome?. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256359.

- McLario DJ, Sivitz AB. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Pediatric Clinical Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(6):594-600.

- Mafort TT, Rufino R, da Costa CH, et al. One-month outcomes of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and their relationships with lung ultrasound signs. Ultrasound J. 2021;13(1):19.

- Kuroda Y, Kaneko T, Yoshikawa H, et al. Artificial intelligence-based point-of-care lung ultrasound for screening COVID-19 pneumoniae: Comparison with CT scans. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0281127.

- Kok B, Schuit F, Lieveld A, Azijli K, Nanayakkara PW, Bosch F. Comparing lung ultrasound: extensive versus short in COVID-19 (CLUES): a multicentre, observational study at the emergency department. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e048795.

- Schenck EJ, Rajwani K. Ultrasound in the diagnosis and management of pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29(2):223-228.

- Xirouchaki N, Kondili E, Prinianakis G, Malliotakis P, Georgopoulos D. Impact of lung ultrasound on clinical decision making in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(1):57-65.

- O’Connor M, Isitt CE, Vizcaychipi MP. Comment on Xirouchaki et al.: Impact of lung ultrasound on clinical decision making in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(7):1061-1062.

- Shah VP, Tunik MG, Tsung JW. Prospective evaluation of point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):119-125.

- Buz Yaşar A, Tarhan M, Atalay B, Kabaalioğlu A, Girit S. Investigation of Childhood Pneumonia With Thoracic Ultrasound: A Comparison Between X-ray and Ultrasound. Ultrasound Q. 2023;39(4):216-222.

- Shi C, Xu X, Xu Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the accuracy of lung ultrasound and chest radiography in diagnosing community acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024;59(12):3130-3147.

- Balk DS, Lee C, Schafer J, et al. Lung ultrasound compared to chest X-ray for diagnosis of pediatric pneumonia: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53(8):1130-1139.

- Llamas-Álvarez AM, Tenza-Lozano EM, Latour-Pérez J. Accuracy of Lung Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Pneumonia in Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest. 2017;151(2):374-382.

- Padrao EMH, Caldeira Antonio B, Gardner TA, et al. Lung Ultrasound Findings and Algorithms to Detect Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Testing Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. Published online August 14, 2025. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000006818.

- Darge K, Chen A. Ultrasonography of the lungs and pleurae for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: prime time for routine use. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):187-188.

- J Jakobson D, Cohen O, Cherniavsky E, Batumsky M, Fuchs L, Yellin A. Ultrasonography can replace chest X-rays in the postoperative care of thoracic surgical patients. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0276502.

- Javaudin F, Marjanovic N, de Carvalho H, et al. Contribution of lung ultrasound in diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in the emergency department: a prospective multicentre study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e046849.

- Jensen MBB, Aakjær Andersen C. Accuracy of lung ultrasonography in the hands of non-imaging specialists to diagnose and assess the severity of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e036067.

- Geis D, Canova N, Lhopitallier L, et al. Exploration of the Acceptance of the Use of Procalcitonin Point-of-Care Testing and Lung Ultrasonography by General Practitioners to Decide on Antibiotic Prescriptions for Lower Respiratory Infections: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5):e063922.

- Tran-Le QK, Thai TT, Tran-Ngoc N, et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis and monitoring of pneumonia in a tuberculosis-endemic setting: a prospective study. BMJ Open. 2025;15(4):e094799.

- Morello R, Camporesi A, De Rose C, et al. Point-of-care lung ultrasound to differentiate bacterial and viral lower respiratory tract infections in pediatric age: a multicenter prospective observational study. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):35196.

- Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care, and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;82(3):e115-e155.

- Volpicelli G, Fraccalini T, Cardinale L. Lung ultrasound: are we diagnosing too much?. Ultrasound J. 2023;15(1):17.

- Glover RE, Mays NB, Fraser A. Do you see the problem? Visualising a generalised ‘complex local system’ of antibiotic prescribing across the United Kingdom using qualitative interview data. Crit Public Health. 2023;33(4):459-471.

- Volpicelli G, Rovida S. Clinical research on point-of-care lung ultrasound: misconceptions and limitations. Ultrasound J. 2024;16(1):28.

- Dell’Aquila P, Raimondo P, Racanelli V, et al. Integrated lung ultrasound score for early clinical decision-making in patients with COVID-19: results and implications. Ultrasound J. 2022;14(1):21.

- Fabuel Ortega P, Almendros Lafuente N, Cánovas García S, Martínez Gálvez L, González-Vidal A. The correlation between point-of-care ultrasound and digital tomosynthesis when used with suspected COVID-19 pneumonia patients in primary care. Ultrasound J. 2022;14(1):11.

- Gartlehner G, Wagner G, Affengruber L, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in Patients With Acute Dyspnea: An Evidence Report for a Clinical Practice Guideline by the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(7):967-976.

- Bossuyt PM, Irwig L, Craig J, Glasziou P. Comparative accuracy: assessing new tests against existing diagnostic pathways. BMJ. 2006;332(7549):1089-1092.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).