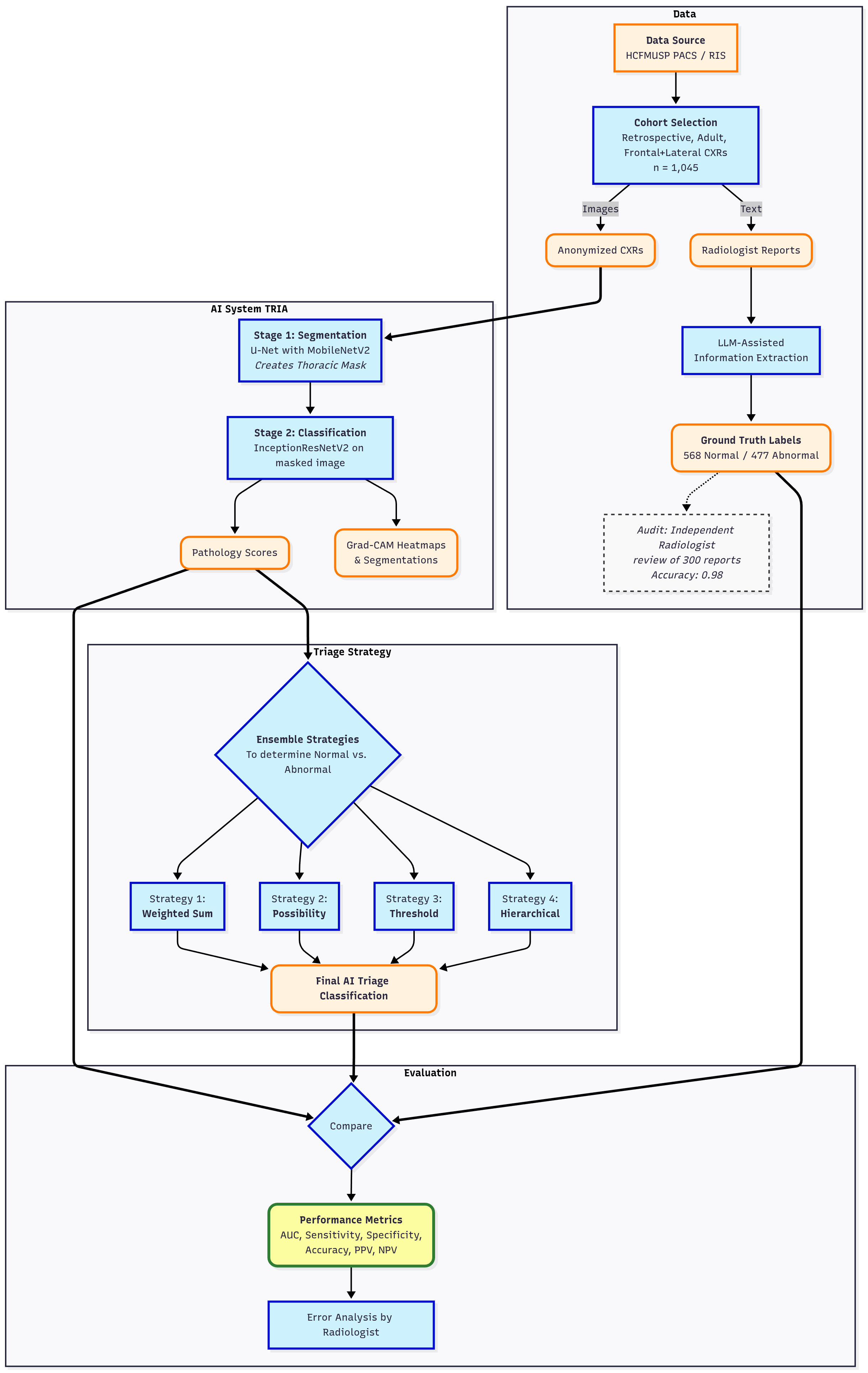

1. Introduction

The chest radiography (CXR) remains the most common radiological examination globally, serving as a critical first-line diagnostic tool[

1]. However, the high volume of CXRs, coupled with a worldwide shortage of radiologists, often leads to significant reporting backlogs. This delay is particularly acute in emergency department (ED) settings, where timely interpretation is crucial for patient management. In many such settings, initial CXR readings are performed by general practitioners or ED physicians who may lack the specialized expertise of a radiologist, potentially leading to diagnostic errors or delays.

As in many other industries, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged in healthcare as a promising approach to address persistent challenges. The advent of deep learning has enabled novel diagnostic applications, with algorithms achieving levels of accuracy comparable to those of expert clinicians in disease recognition[

2]. One of the earliest and most impactful applications is triage, defined as the automated prioritization of medical cases[

3]. A system capable of reliably differentiating between normal and abnormal chest radiographs (CXRs) can improve physicians ability to recognize abnormalities in CXR [

4] and has potential to optimize clinical workflows by directing abnormal or critical studies for immediate evaluation by a radiologist. Furthermore, radiology represents the medical specialty with the highest number of AI software approvals, highlighting the imperative for rigorous post-implementation validation of these systems[

5].

This study aims to perform an external validation of TRIA, a commercial AI-powered chest radiograph triaging system manufactured by NeuralMed (São Paulo, Brazil), registered with Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) as a Class II medical device (Register 8261971001)[

6]. We retrospectively evaluated its post-implementation performance on Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo (HCFMUSP) to determine its accuracy in classifying CXRs as normal versus abnormal, a critical step for validating its clinical utility. This study supports ANVISA requirements for manufacturers to maintain clinical evaluation and post-market surveillance[

7] and it is funded by Neuralmed. This study was also approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee board.

2. Methods

2.1. AI Algorithm (TRIA)

The algorithm is based on a dual-pronged deep learning approach, consisting of a lung field segmentation pipeline followed by a pathology classification model. A key design choice of the methodology is the prioritization of intrathoracic findings, especially those related to the cardiopulmonary system, at the expense of musculoskeletal and spinal conditions.

2.1.1. Training Dataset

The models were developed using a large-scale, multi-source dataset of 275,399 anonymized, unique chest radiographs. The dataset was curated from public and private sources and features a multi-label annotation schema (

Table 1). Part of the dataset originated from private clinical sources collected under research and commercial agreements in compliance with Brazilian General Data Protection Law [

8].

The public datasets included: the Shenzhen Chest X-ray Set[

9]; the Indiana University Chest X-ray Collection[

10]; the JSRT database from the Japanese Society of Radiological Technology[

11]; the NIH ChestX-ray14 dataset[

12]; and the PadChest dataset[

13]. All public datasets were used in compliance with their respective open-access agreements.

Before training, the images were proofed by medical radiology specialists using a proprietary annotation application (

Figure 1). The dataset exhibits a significant class imbalance reflective of real-world pathology prevalence. For training binary classifiers, studies with definitive labels (1.0 for present, 0.0 for absent) were used, while studies with missing labels for a specific finding were excluded from the loss calculation for that task.

Table 2 shows the distribution for a selection of key labels. The list of pathologies was selected based on the availability of labeled data, balanced with clinical importance for ED. The ’normal’ and ’abnormal’ pools included cases with pathologies beyond the specifically targeted list; these were categorized under the general "yesfinding" class.

2.1.2. Algorithm Architecture

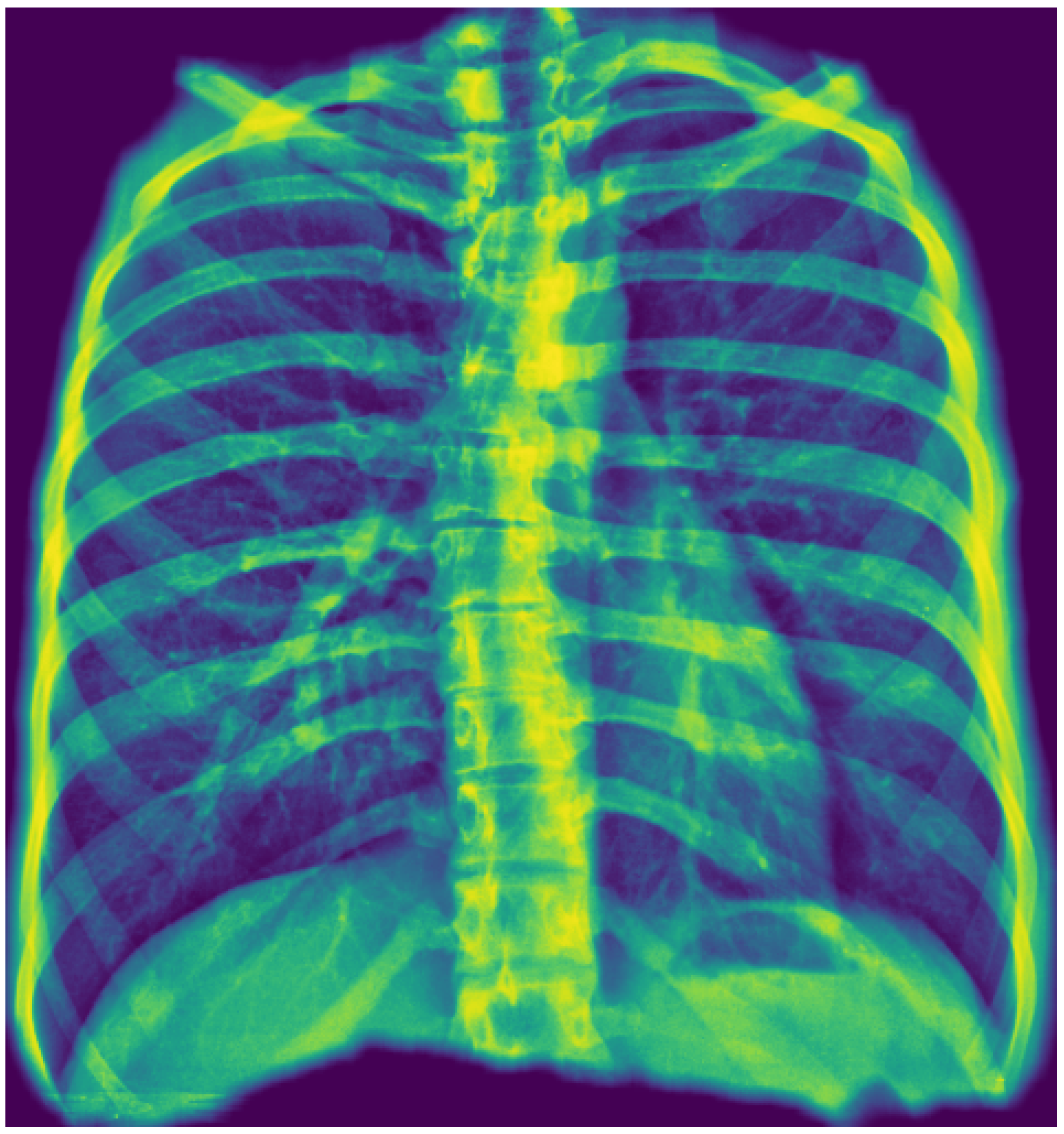

The first stage employs a U-Net architecture with a MobileNetV2 encoder to generate a unified thoracic mask. This process uses a "tongue-shaped" mask that creates a single contiguous region of interest (ROI) encompassing both lungs and the intervening mediastinal and hilar regions. This approach simplifies binary segmentation and ensures that critical central structures are included in the analysis. Input images were resized to 512x512 pixels, and the model was trained using a composite Dice and Binary Focal loss function.

Figure 2 shows an example.

The second stage uses an InceptionResNetV2 model, pre-trained on ImageNet, for pathology classification. The model’s top layers were replaced to suit the specific task. A notable trade-off in development was resizing input images to a low resolution of 75x75 pixels to facilitate rapid training. The model was trained using class weights to counteract data imbalance.

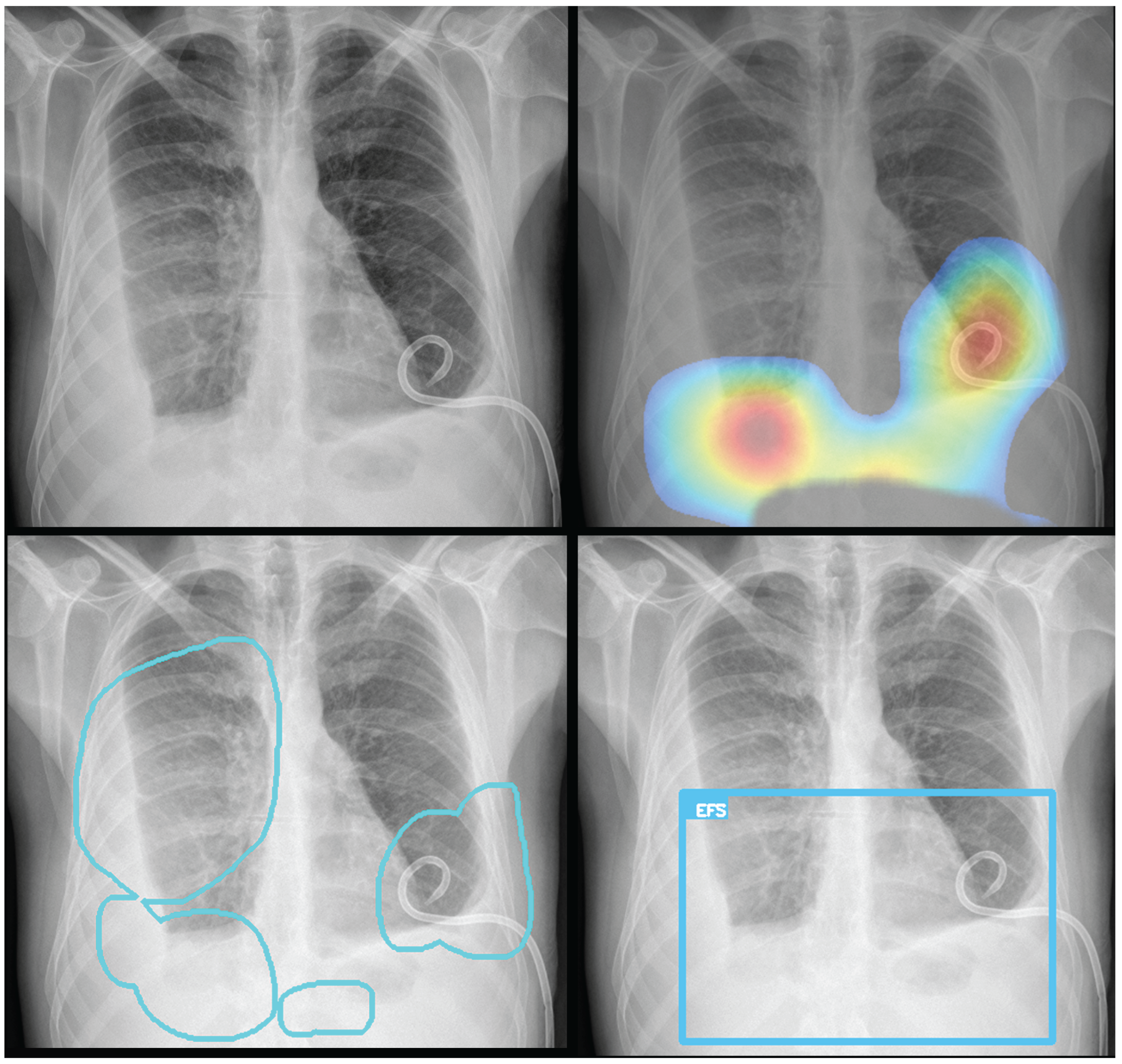

To provide visual explanations for the pathologies identified, both Grad-CAM heatmaps and segmentation masks are generated and overlaid on the original CXR images. The Grad-CAM technique produces class activation maps, highlighting the image regions most influential in the model’s prediction for a specific pathology. The resulting overlays—which can be a heatmap, bounding box, or contoured area—identify the most relevant regions, ensuring the system provides clear and interpretable visual evidence for its predictions (

Figure 3).

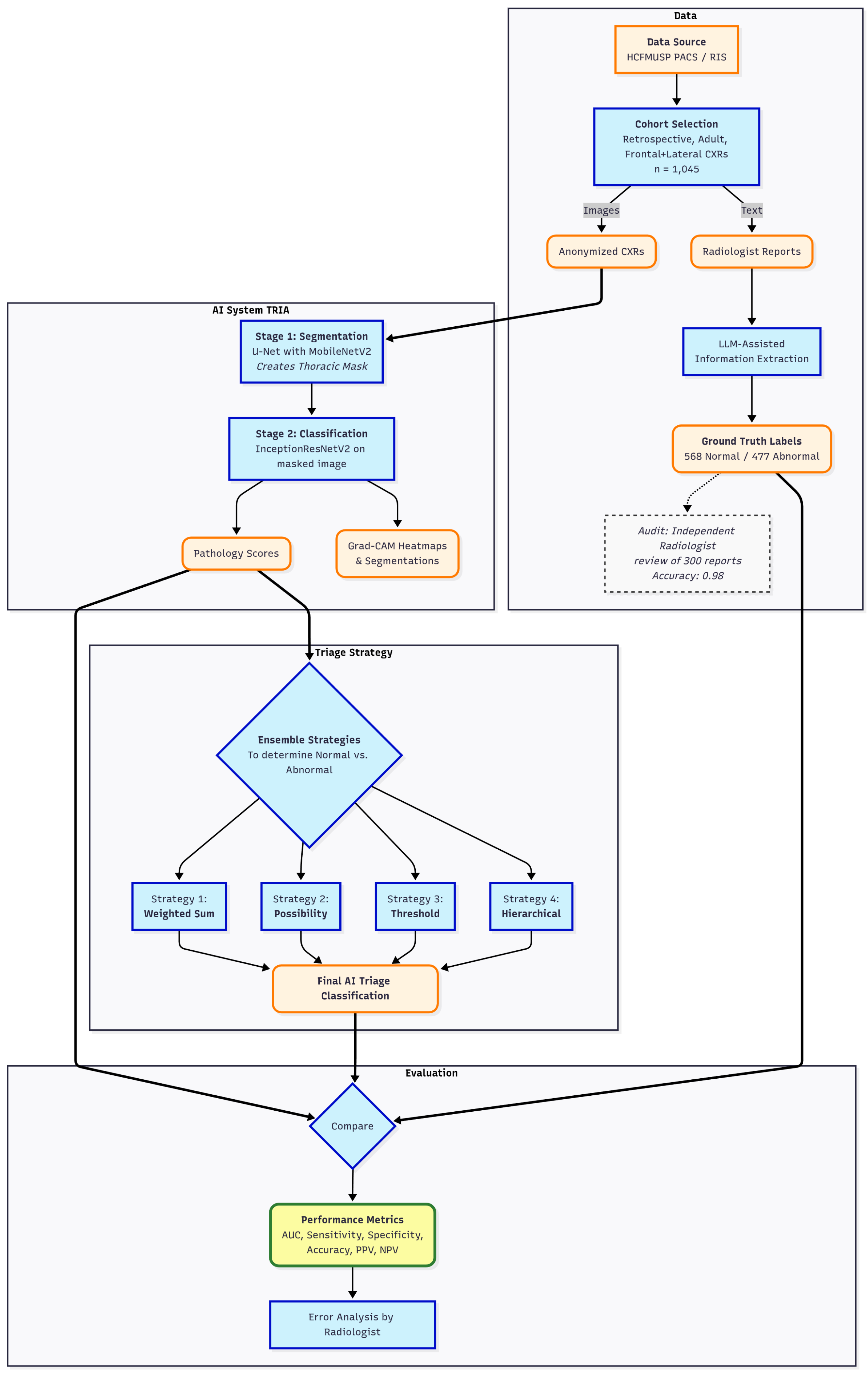

2.2. Validation Study Design

For validation, a retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted on a dataset of 1,045 anonymized chest radiographs from HCFMUSP, over the past five years. Eligibility was restricted to adult CXR studies that included both frontal and lateral images and had an accompanying report authored by a senior radiologist. To ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the algorithm’s performance on both normal and abnormal cases, a purposive sampling strategy was employed. The final cohort was constructed by selecting 568 examinations with reports describing a normal chest and 477 examinations with abnormal findings. The abnormal cases were identified by selecting reports that lacked a normal description and contained one or more of the following keywords: "pneumonia", "opacity", "cardiomegaly", "pneumothorax", "effusion", "nodule" or "mass". To create structured, binary labels for evaluation, these reports were processed using a large language model (LLM) assisted extraction method[

14]. A prompt was crafted to structure the output to match the JSON format of the computer vision algorithm’s results. To evaluate the normal and abnormal separation, the accuracy of each pathology classifier and the criticality ensemble were calculated. The radiographs were processed by the TRIA system that served the institution through its Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) using files in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format.

2.3. Analysis

The evaluation was performed using a multi-step pipeline that began with threshold optimization for each individual pathology classifier. Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROCC) were generated, and optimal probability thresholds were selected using Youden’s J statistic to balance sensitivity and specificity.

Following threshold optimization, four ensemble classification strategies were evaluated to combine the predictions of individual classifiers into a single normal/abnormal decision. The approach used in the commercial product is a rule-based method ("Possibility-based"). Other methods included a threshold-based approach, which flags an exam as abnormal if any pathology prediction exceeds its optimal threshold, and a weighted sum-based method, which uses a weighted sum of prediction probabilities, giving higher weight to the general "yesfinding" indicator. In addition, a hierarchical approach that prioritizes critical findings was also implemented.

The next step involved a comprehensive performance evaluation, where sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy, F1 score, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) were calculated for all models and ensembles. Exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed for all metrics, while AUROC CI were estimated via bootstrap resampling to ensure statistical rigor. Finally, an error analysis was performed by a senior radiologist who inspected the original images, reports, extracted data, and predictions for all false negatives from the six listed pathologies.

Figure 4 depicts performed validation and analysis .

3. Results

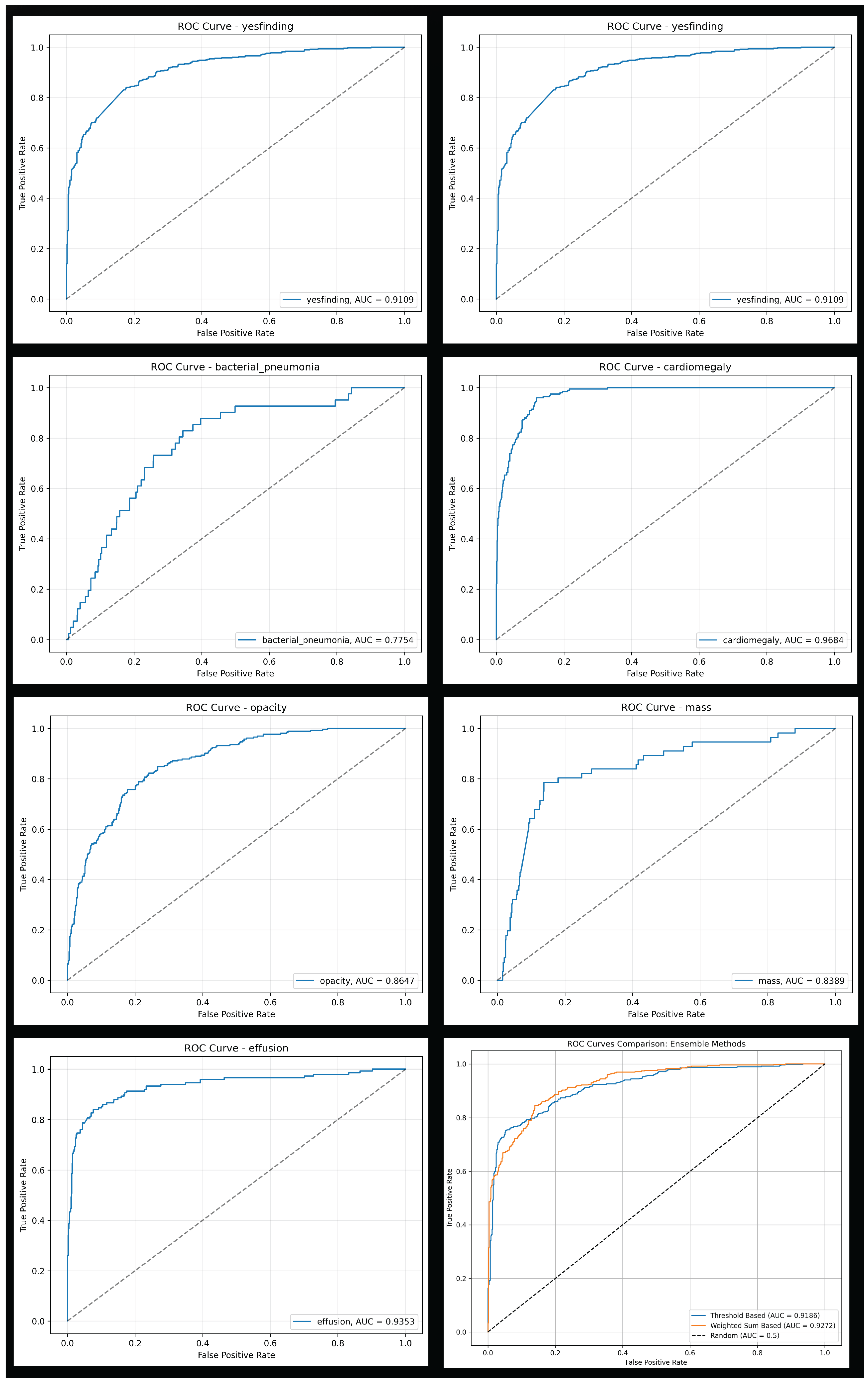

3.1. Individual Classifier Performance

The general "yesfinding" model demonstrated strong performance with an AUROC of 0.911. For specific pathologies, the models for cardiomegaly, pneumothorax, and effusion showed excellent discriminative ability, achieving AUROC of 0.968, 0.955, and 0.935, respectively. In contrast, the model for bacterial pneumonia, while showing high sensitivity (0.829), had a relatively low specificity (0.656), indicating a high false-positive rate. Detailed performance metrics for each classifier are presented in

Table 3.

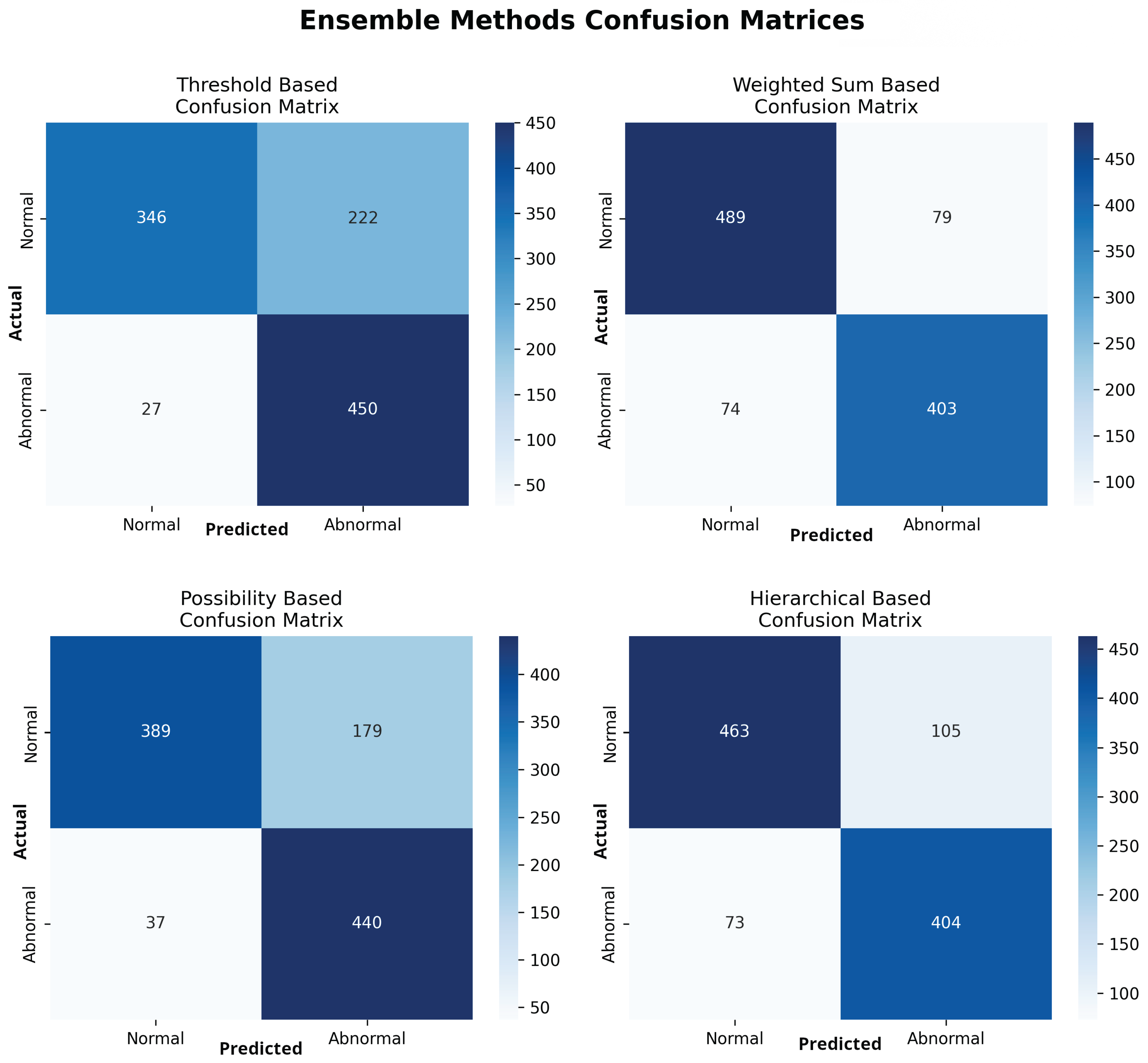

3.2. Ensemble Model Performance for Abnormality Detection

To classify exams as normal or abnormal, four distinct ensemble strategies were evaluated. The weighted sum-based ensemble yielded the most balanced and superior overall performance. It achieved an accuracy of 0.854 (95% CI: 0.831-0.874), a sensitivity of 0.845 (95% CI: 0.810-0.875), a specificity of 0.861 (95% CI: 0.830-0.887), and an AUROC of 0.927 (95% CI: 0.911-0.940). This model provided the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. In contrast, the threshold-based and possibility-based methods achieved higher sensitivity (0.943 and 0.922, respectively) at a significant cost to specificity (0.609 and 0.685, respectively), resulting in a greater number of false positives. The comprehensive performance of all four ensemble methods is detailed in

Table 4, with ROCC for the top models shown in

Figure 5 and confusion matrices for all methods in

Figure 6.

3.3. Error Analysis

An analysis of the algorithm’s false negatives reveals a nuanced performance profile, where a specific miss did not always equate to a complete system failure. Across the board, a substantial number of cases with a false negative for one specific pathology were nevertheless correctly identified as abnormal by the general "yesfinding" classifier or had other co-occurring true positive pathologies. For example, out of 38 false negatives for ’opacity,’ the algorithm correctly identified the exam as abnormal in 25 cases. In many instances of a missed finding, the algorithm successfully detected other pathologies within the same study. Misclassification was another notable source of error, where an existing pathology was detected but incorrectly labeled, such as opacities being predicted as masses or nodules (

Figure 7). Radiologist review of these false-negative cases frequently noted findings that were "subtle," "small," "doubtful," "seen on lateral image only," or "non-specific." In other cases, the algorithm correctly identified a more critical finding, like a large pleural effusion, while missing a secondary, less significant pathology (

Figure 3).

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate false negative cases for opacity, pneumothorax, and nodule, respectively. This highlights the inherent limitations and inevitable failures of this kind of system.

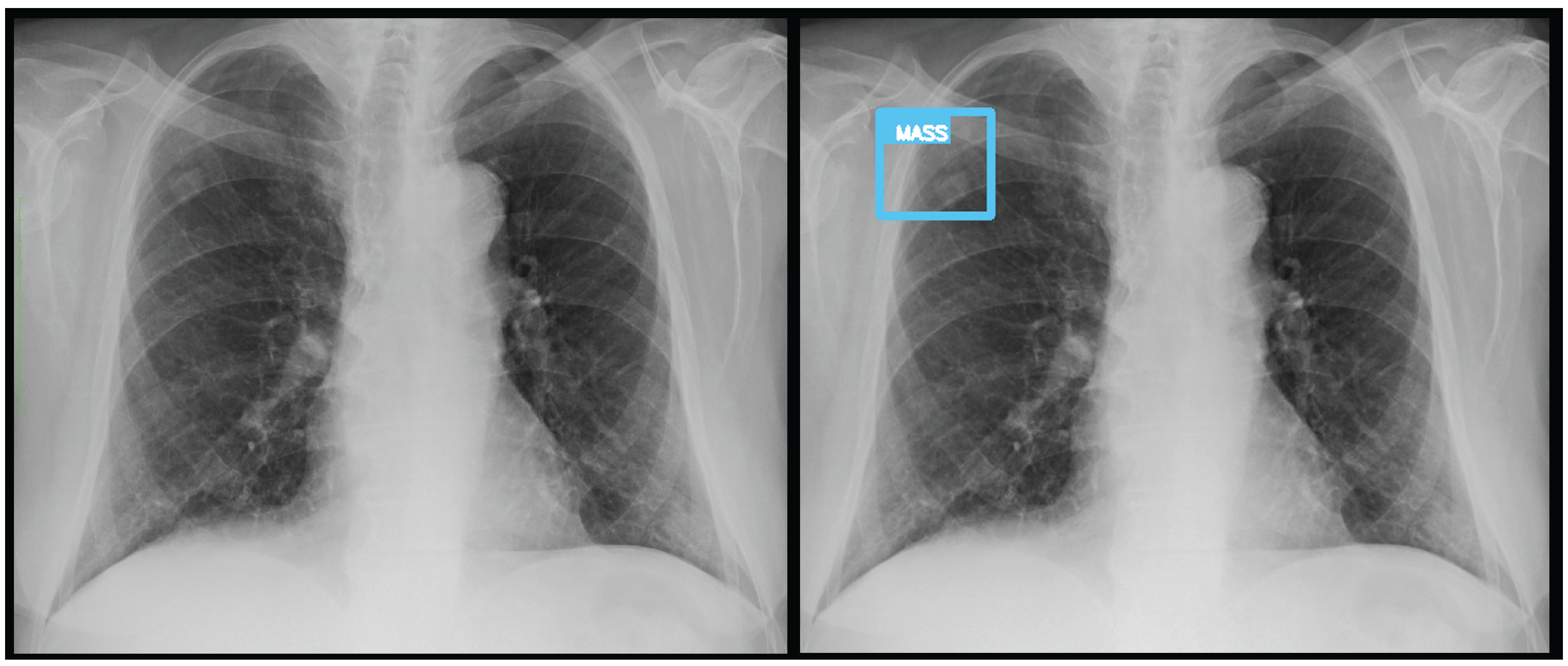

Figure 7.

A true positive for a nodule/mass. In this case, the report indicated an opacity, however it was classified by the algorithm as a mass.

Figure 7.

A true positive for a nodule/mass. In this case, the report indicated an opacity, however it was classified by the algorithm as a mass.

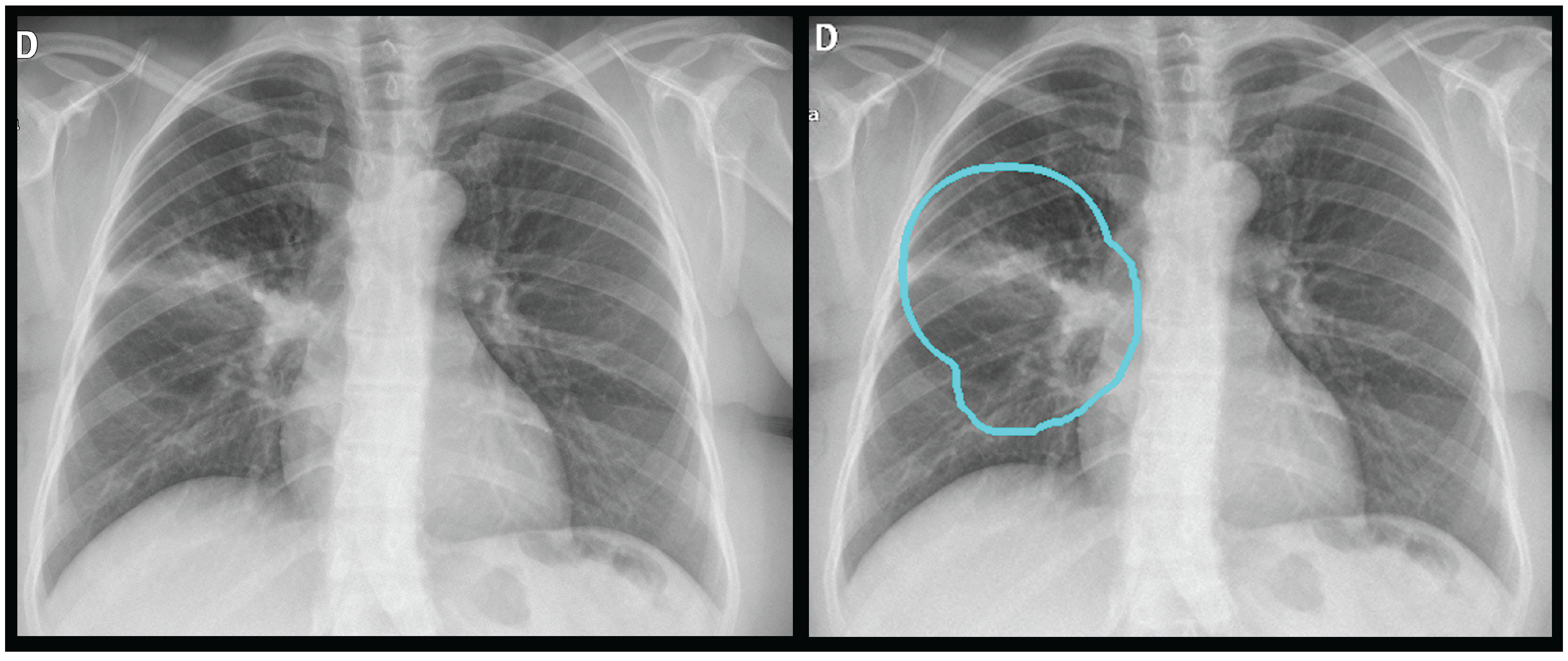

Figure 8.

A true positive for opacity and consolidation.

Figure 8.

A true positive for opacity and consolidation.

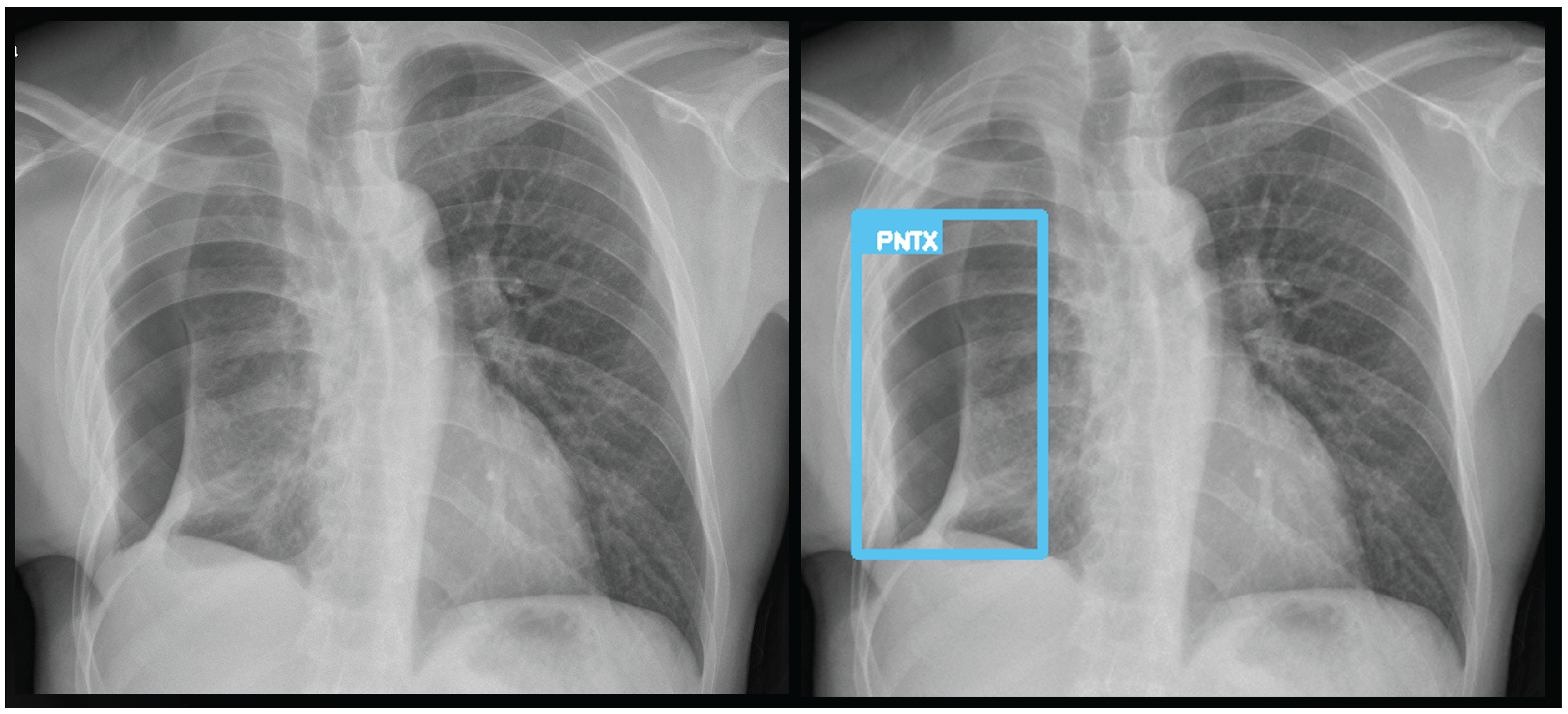

Figure 9.

A true positive for pneumothorax. The algorithm successfully detected pneumothorax without a pleural tube, indicating it is not overfitted to post-drainage cases.

Figure 9.

A true positive for pneumothorax. The algorithm successfully detected pneumothorax without a pleural tube, indicating it is not overfitted to post-drainage cases.

Figure 10.

A false negative example of a small, missed nodule (black arrow).

Figure 10.

A false negative example of a small, missed nodule (black arrow).

Figure 11.

A false negative example of an alveolar opacity (black arrow).

Figure 11.

A false negative example of an alveolar opacity (black arrow).

Figure 12.

A false negative example of a missed loculated pneumothorax. The presence of pulmonary markings (black arrow) beyond the pleural line (white arrowhead) may have misled the algorithm.

Figure 12.

A false negative example of a missed loculated pneumothorax. The presence of pulmonary markings (black arrow) beyond the pleural line (white arrowhead) may have misled the algorithm.

4. Discussion

The intended clinical application for the TRIA system is as a triage tool to prioritize worklists, a common and valuable use case for radiology AI[

3,

15]. This study provides a necessary external validation of the system for this purpose. The evaluation methodology used is a standard approach in AI validation, as highlighted in systematic reviews and other external evaluations[

15,

16,

17].

A key methodological strength of the underlying AI model is the tongue-shaped segmentation mask. By including the mediastinum and hilar regions in the ROI, the model analyzes these diagnostically critical areas, which are often excluded by traditional lung-only segmentation. This approach creates a more clinically relevant area for analysis that may improve the detection of central pathologies.

However, a significant trade-off in the model’s design is the use of a very low input resolution (75x75 pixels) for classification. While this allows for computational efficiency, it inherently risks the loss of fine-grained details necessary for detecting subtle pathologies like small nodules or early interstitial disease. This was reflected in the error analysis, where false negatives were often subtle cases. The high false-positive rate for conditions like opacity and bacterial pneumonia suggests the model may be oversensitive to non-specific patterns, highlighting a discrepancy between pure pattern recognition and a radiologist’s clinical interpretation, which incorporates a higher threshold for significance.

The set of pathologies chosen to build the tool reflects the importance of critical findings for emergency physicians unassisted by radiology specialists. The limited number of specific pathologies favors computational efficiency, while the general normal/abnormal classifier ("yesfinding") provides a safeguard for unlisted pathologies, as depicted by the ensemble results.

Our validation dataset, comprising 1,045 curated chest radiographs (CXRs), provides a statistically robust sample size. This cohort yields 95% confidence intervals with margins of error of approximately ±3–4% for key performance metrics, thereby exceeding typical requirements for medical imaging validation. Although this enriched sampling ensures that the algorithm is evaluated across a wide range of conditions, it does not reflect true disease prevalence and contrasts with studies employing large, consecutive prospective cohorts from routine clinical practice, which provide a more realistic benchmark of real-world performance[

18,

19]. Ground truth was established through LLM–assisted extraction of findings from reports authored by senior radiologists, a pragmatic strategy for large-scale datasets. A subset of 300 reports was independently reviewed by a radiologist, yielding an accuracy of 0.9838 (95% CI: 0.9783–0.9883), thereby supporting the reliability of the adopted approach. Nevertheless, more rigorous standards for ground truth determination exist, such as consensus interpretation by a panel of expert radiologists or correlation with reference imaging modalities, including computed tomography [

18,

20,

21,

22].

A comparative analysis reveals a landscape of varied performance among commercial AI solutions. In this study, the possibility-based ensemble (used in the commercial product) obtained high sensitivity, while the weighted sum ensemble demonstrated robust and balanced performance for abnormality stratification, achieving an AUROC of 0.927 with a sensitivity of 84.5% and a specificity of 86.1%. This balanced profile contrasts with other AI triage tools, such as the one evaluated by Blake et al., which was optimized for very high sensitivity (99.6%) at the expense of lower specificity (67.4%)[

15]. Another algorithm evaluated in a primary care setting showed excellent specificity (92.0%) but significantly lower sensitivity (47.0%)[

23]. These differences represent fundamental design choices: one prioritizes minimizing missed findings, accepting more false positives, while the other seeks to balance sensitivity and specificity to reduce workload more efficiently. The overall AUROC for TRIA is comparable to high-performing algorithms evaluated in other studies, which often achieve AUROC in the 0.92 to 0.94 range[

24,

25].

The error analysis of TRIA, which noted that false negatives were often subtle or challenging cases, is a consistent finding across the field. For instance, Plesner et al. similarly found that the performance of four different commercial tools declined for smaller-sized findings and on complex radiographs with multiple pathologies[

18]. Our study identifies the model’s very low input resolution as a potential factor contributing to missing fine-grained details. Despite this, while the model may misclassify or miss a specific finding, its ability to flag an exam as generally abnormal remains high, ensuring that complex cases are still prioritized for radiologist review. The variability highlighted in

Table 5 also shows that algorithm performance is highly dependent on the clinical task and validation setting, suggesting that a single set of metrics may not fully capture an algorithm’s utility.

This study has some limitations. First, this evaluation is retrospective, and performance can decrease when transitioning from a curated analysis to a prospective implementation[

16]. Second, the validation was conducted at a single center, which may limit generalizability. Finally, the validation dataset was enriched with significant pathologies and therefore does not reflect the typical prevalence of findings in a real-world population, which may influence performance metrics.

Future work should include prospective, multi-center validation studies to assess the algorithm’s performance in real-time clinical workflows and to measure its impact on downstream outcomes, such as time-to-diagnosis and workload reduction. Further refinement of the classification model, particularly by adding more pathologies and exploring higher input resolutions, could enhance its ability to detect more subtle findings and improve its clinical utility.

5. Conclusion

This independent retrospective validation demonstrates that the TRIA AI algorithm achieves robust and accurate performance in discriminating between normal and abnormal chest radiographs. The actual commercial version has excellent sensitivity and provides confidence for clinical implementation as a reliable tool for triaging CXRs. The strong and balanced performance of weighted sum ensemble strategy provides a viable alternative when more specificity is warranted. The tool could help manage reporting backlogs, prioritize urgent cases for radiologist review, and potentially support earlier patient intervention. This study provides a foundation for future prospective and comparative research to further evaluate the algorithm’s clinical utility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E. and A.C.; Methodology, A.C. and M.W.; Software, M.W., A.Y. and A.C.; Validation, I.D., M.S., and M.E.; Formal Analysis, M.W. and A.C.; Investigation, A.C., I.D., M.S., and M.E.; Resources, I.D., M.S., and M.E.; Data Curation, M.W., I.D., M.S., and M.E.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, all authors; Supervision, M.S., A.C. and A.E.; Project Administration, A.C.; Funding Acquisition, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC was funded by NeuralMed (A2 Tecnologia Ltda)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of HCFMUSP (protocol code CAAE: 85444924.9.0000.0068).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, which involved the analysis of fully anonymized pre-existing medical data.

Data Availability Statement

The processed datasets generated and analysed during the current study are publicly available, however the images and the full reports are confidential and sensitive health data from HCFMUSP and still not released.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Radiology at HCFMUSP for their support and for providing the data for this validation study.

Conflicts of Interest

A.C. and A.E. are founders and stakeholders of of NeuralMed, the company that manufactures the TRIA system and funded the study. A.C., A.E., M.W., and A.Y. are employees of NeuralMed. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had a role in the design of the study; in the data analysis and interpretation; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Smith-Bindman, R.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Johnson, E.; et al. Use of Diagnostic Imaging Studies and Associated Radiation Exposure for Patients Enrolled in Large Integrated Health Care Systems, 1996-2010. JAMA 2012, 307, 2400–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annarumma, M.; Withey, S.J.; Bakewell, R.J.; Pesce, E.; Goh, V.; Montana, G. Automated Triaging of Adult Chest Radiographs with Deep Artificial Neural Networks. Radiology 2019, 291, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.G.; Tarder-Stoll, H.; Alpaslan, M.; Keathley, N.; Levin, D.L.; Venkatesh, S.; et al. Deep learning improves physician accuracy in the comprehensive detection of abnormalities on chest X-rays. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windecker, D.; Baj, G.; Shiri, I.; et al. Generalizability of FDA-Approved AI-Enabled Medical Devices for Clinical Use. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e258052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Consulta de Registro de Software como Dispositivo Médico - A2 Tecnologia Ltda. 2023. Available online: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/saude/25351120732202361/?nomeProduto=tria (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Dispõe sobre as boas práticas de fabricação de produtos médicos e produtos para diagnóstico de uso in vitro e dá outras providências. RDC Nº 657/2022; Ministério da Saúde, 2022. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-657-de-24-de-marco-de-2022-389712613 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Brasil. Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais (Lei nº 13.709); Diário Oficial da União, 14 August 2018. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2018/lei/l13709.htm (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Jaeger, S.; Candemir, S.; Antani, S.; Wang, Y.J.; Lu, P.; Thoma, G. Two public chest X-ray datasets for computer-aided screening of pulmonary diseases. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2014, 4, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Demner-Fushman, D.; et al. Preparing a collection of radiology examinations for distribution and retrieval. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi, J.; Katsuragawa, S.; Ikezoe, J.; Matsumoto, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Komatsu, K.; et al. Development of a digital image database for chest radiographs with and without a lung nodule: receiver operating characteristic analysis of radiologists’ detection of pulmonary nodules. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2000, 174, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Lu, L.; Lu, Z.; Bagheri, M.; Summers, R.M. ChestX-ray8: Hospital-scale chest X-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3462–3471. [Google Scholar]

- Bustos, A.; Pertusa, A.; Salinas, J.M.; de la Iglesia-Vayá, M. PadChest: A large chest x-ray image dataset with multi-label annotated reports. Med. Image Anal. 2020, 66, 101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemini Team. Gemini 2.5: Pushing the Frontier with Advanced Reasoning, Multimodality, Long Context, and Next Generation Agentic Capabilities; Google, 2025. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/deepmind-media/gemini/gemini_v2_5_report.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Blake, S.R.; Das, N.; Tadepalli, M.; Reddy, B.; Singh, A.; Agrawal, R.; et al. Using Artificial Intelligence to Stratify Normal versus Abnormal Chest X-rays: External Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm at East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilev, Y.; Vladzymyrskyy, A.; Omelyanskaya, O.; Blokhin, I.; Kirpichev, Y.; Arzamasov, K. AI-Based CXR First Reading: Current Limitations to Ensure Practical Value. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.; Qi, A.; Jeagal, L.; Torabi, N.; Menzies, D.; Korobitsyn, A.; et al. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence-based computer programs to analyze chest x-rays for pulmonary tuberculosis. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0221339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesner, L.L.; Müller, F.C.; Brejnebøl, M.W.; Laustrup, L.C.; Rasmussen, F.; Nielsen, O.W.; et al. Commercially Available Chest Radiograph AI Tools for Detecting Airspace Disease, Pneumothorax, and Pleural Effusion. Radiology 2023, 308, e231236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehoff, J.H.; Kalaitzidis, J.; Kroeger, J.R.; Schoenbeck, D.; Borggrefe, J.; Michael, A.E. Evaluation of the clinical performance of an AI-based application for the automated analysis of chest X-rays. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khader, F.; Han, T.; Müller-Franzes, G.; Huck, L.; Schad, P.; Keil, S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Interpretation of Bedside Chest Radiographs. Radiology 2023, 307, e220510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Camargo, T.F.O.; Ribeiro, G.A.S.; da Silva, M.C.B.; et al. Clinical validation of an artificial intelligence algorithm for classifying tuberculosis and pulmonary findings in chest radiographs. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1512910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, K.G.; Schalekamp, S.; Rutten, M.J.C.M.; et al. Comparison of Commercial AI Software Performance for Radiograph Lung Nodule Detection and Bone Age Prediction. Radiology 2024, 310, e230981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalina, Q.M.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Fuster-Casanovas, A.; Escalé-Besa, A.; Ruiz Comellas, A.; Solé-Casals, J. Real-world testing of an artificial intelligence algorithm for the analysis of chest X-rays in primary care settings. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.Z.; Sander, M.S.; Rai, B.; Titahong, C.N.; Sudrungrot, S.; Laah, S.N.; et al. Using artificial intelligence to read chest radiographs for tuberculosis detection: A multi-site evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of three deep learning systems. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzamasov, K.; Vasilev, Y.; Zelenova, M.; Pestrenin, L.; Busygina, Y.; Bobrovskaya, T.; et al. Independent evaluation of the accuracy of 5 artificial intelligence software for detecting lung nodules on chest X-rays. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 5288–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).