Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

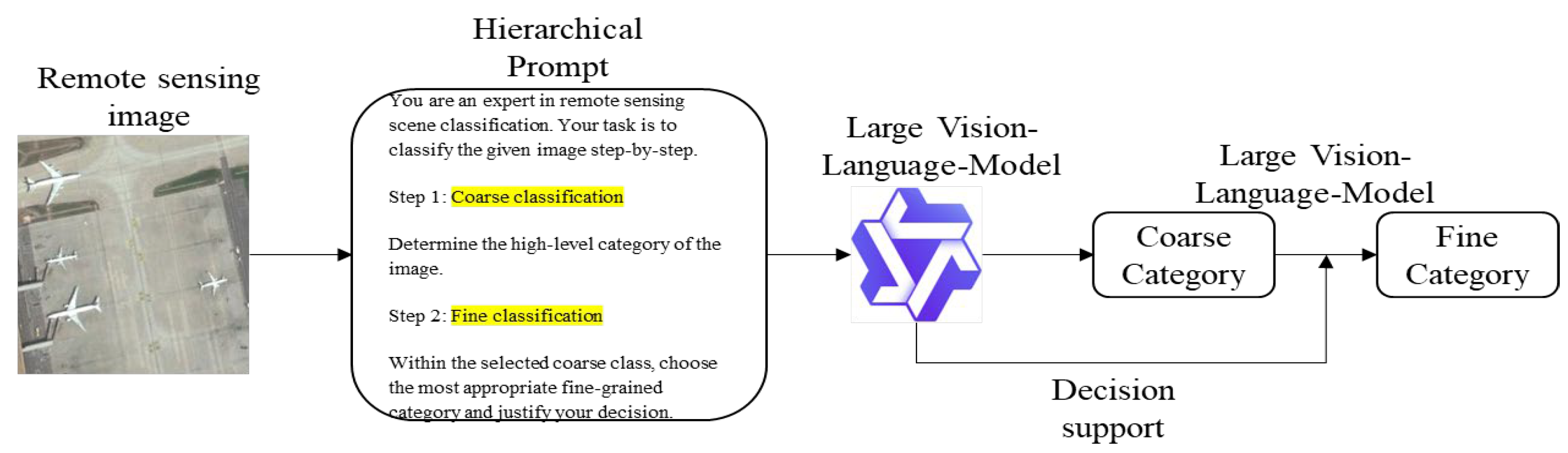

3.1. AID Dataset Preparation

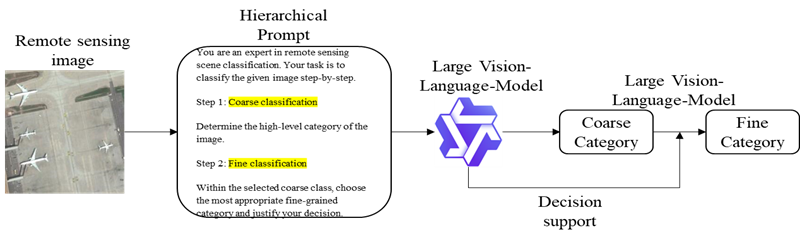

3.2. Prompt Design

3.3. External Evaluation Datasets and Label Mapping

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Hyperparameters

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Main Results

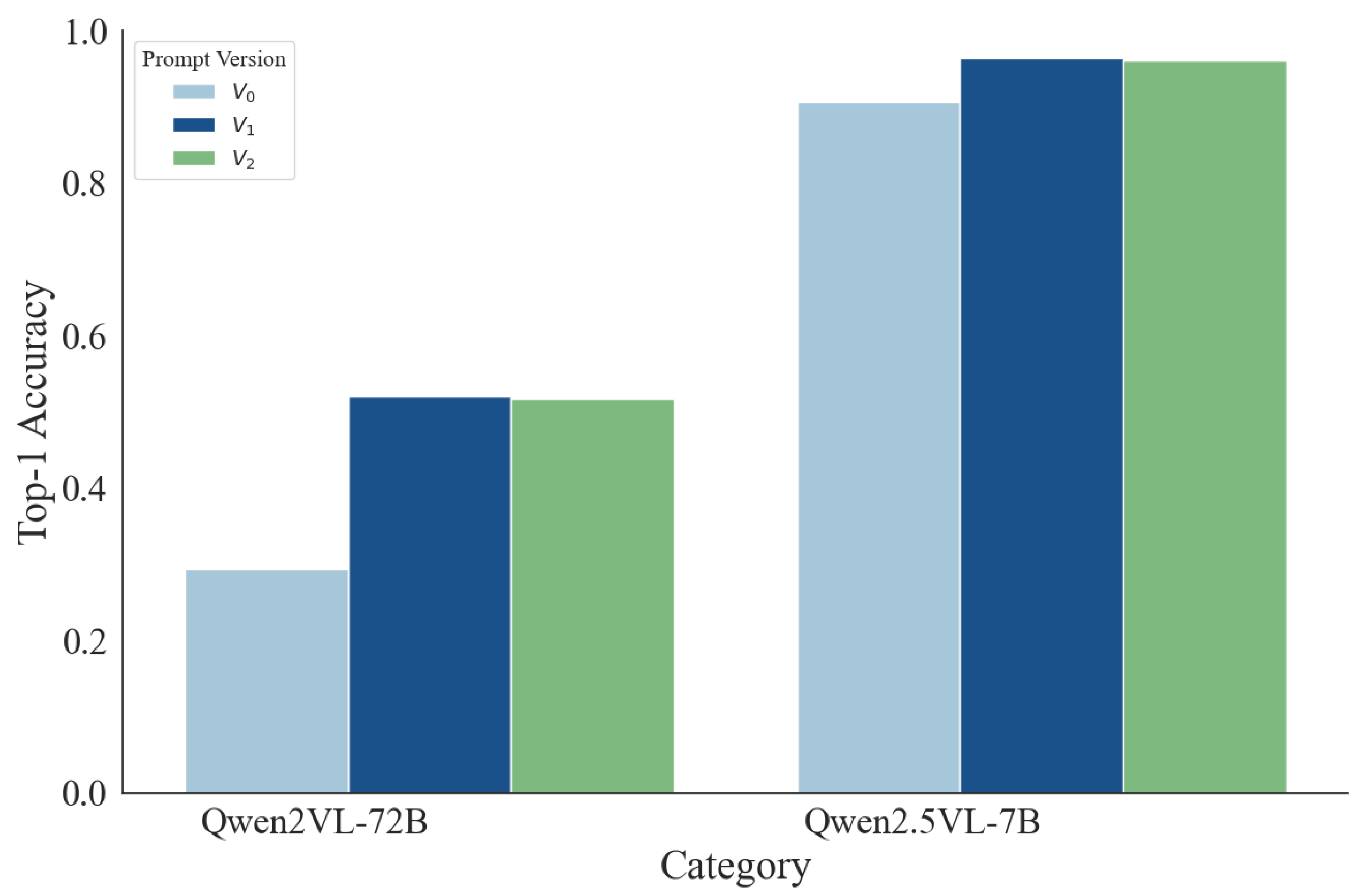

4.2.1. Prompt Engineering Analysis

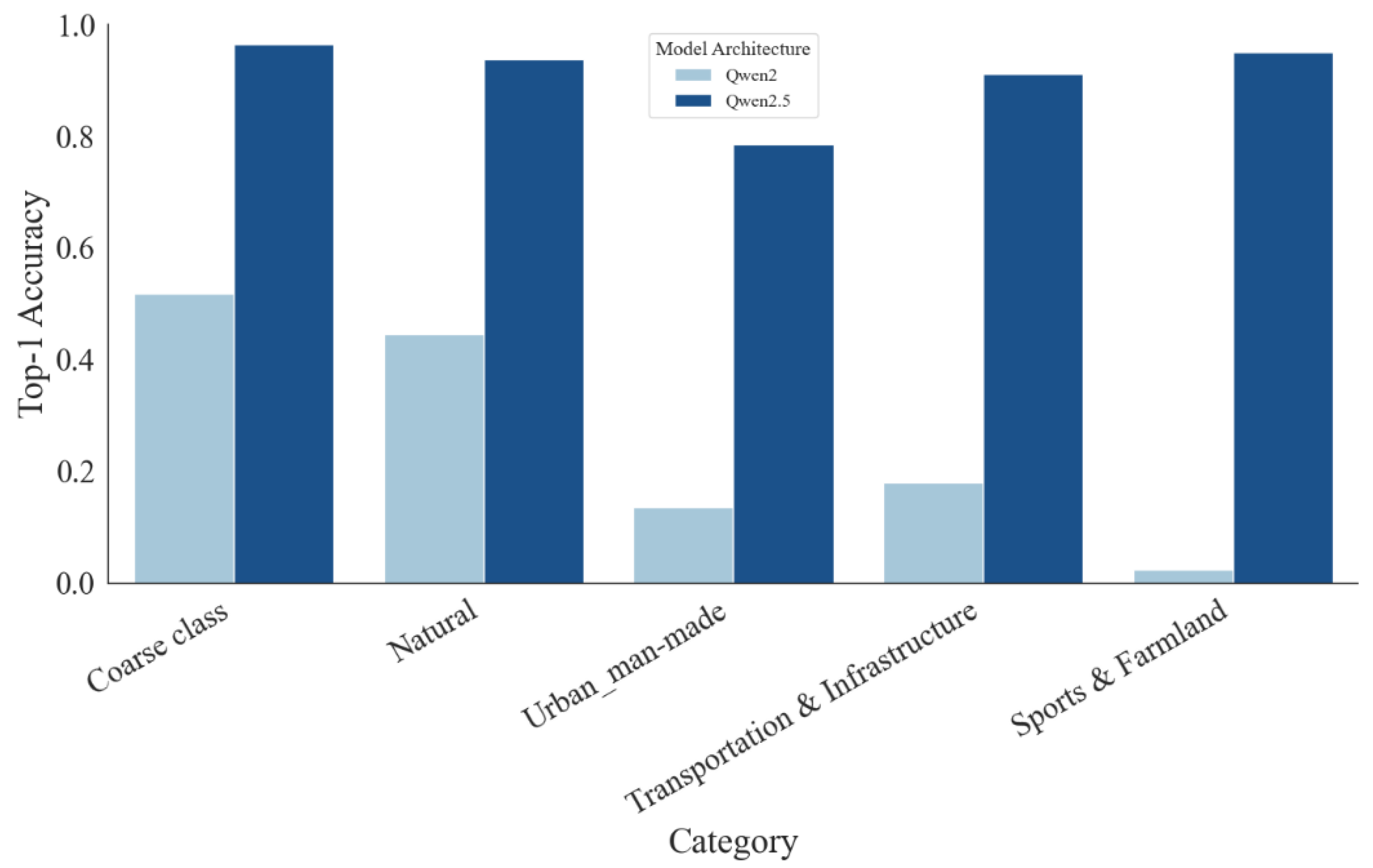

4.2.2. Model Architecture Comparison

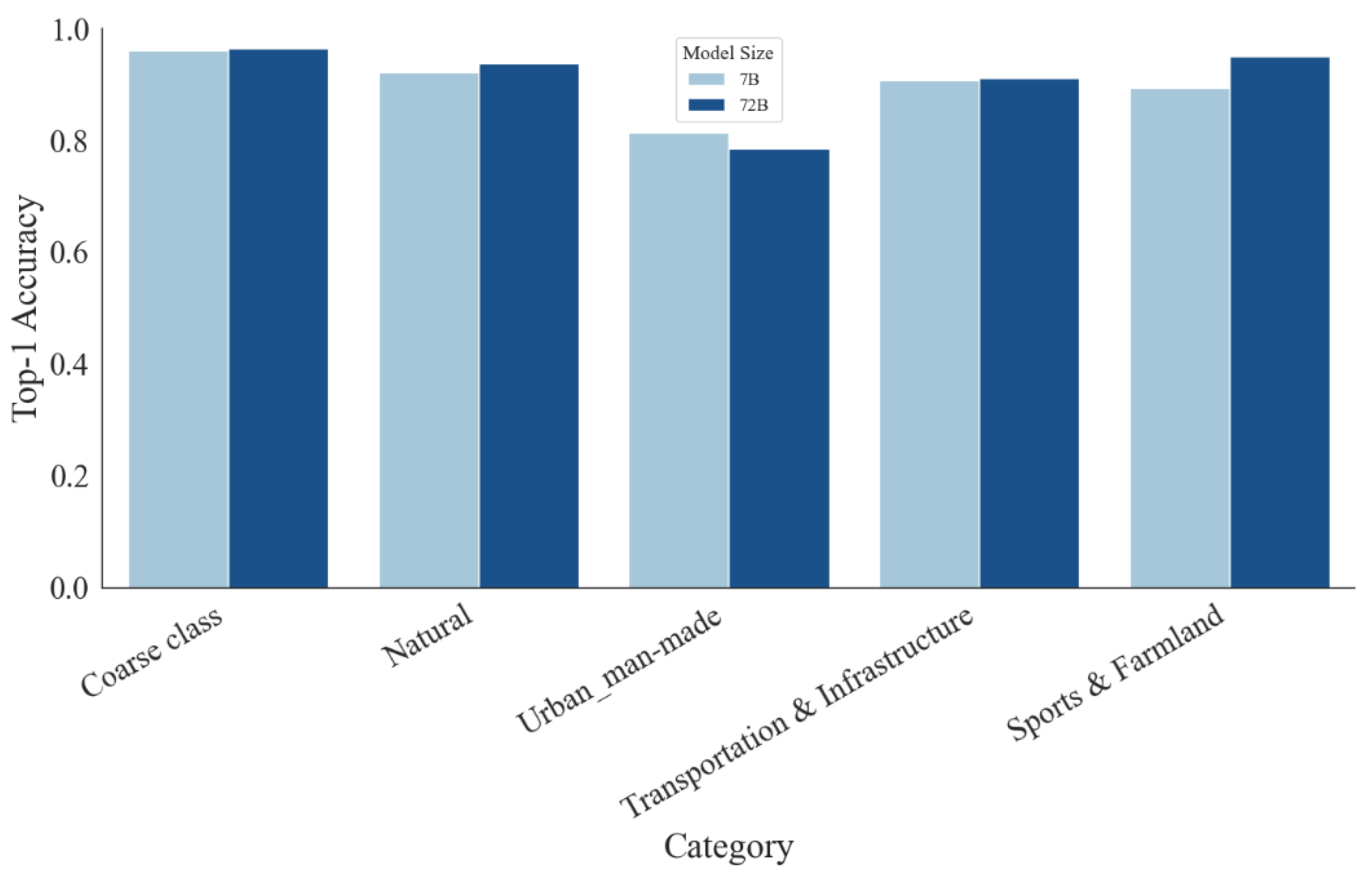

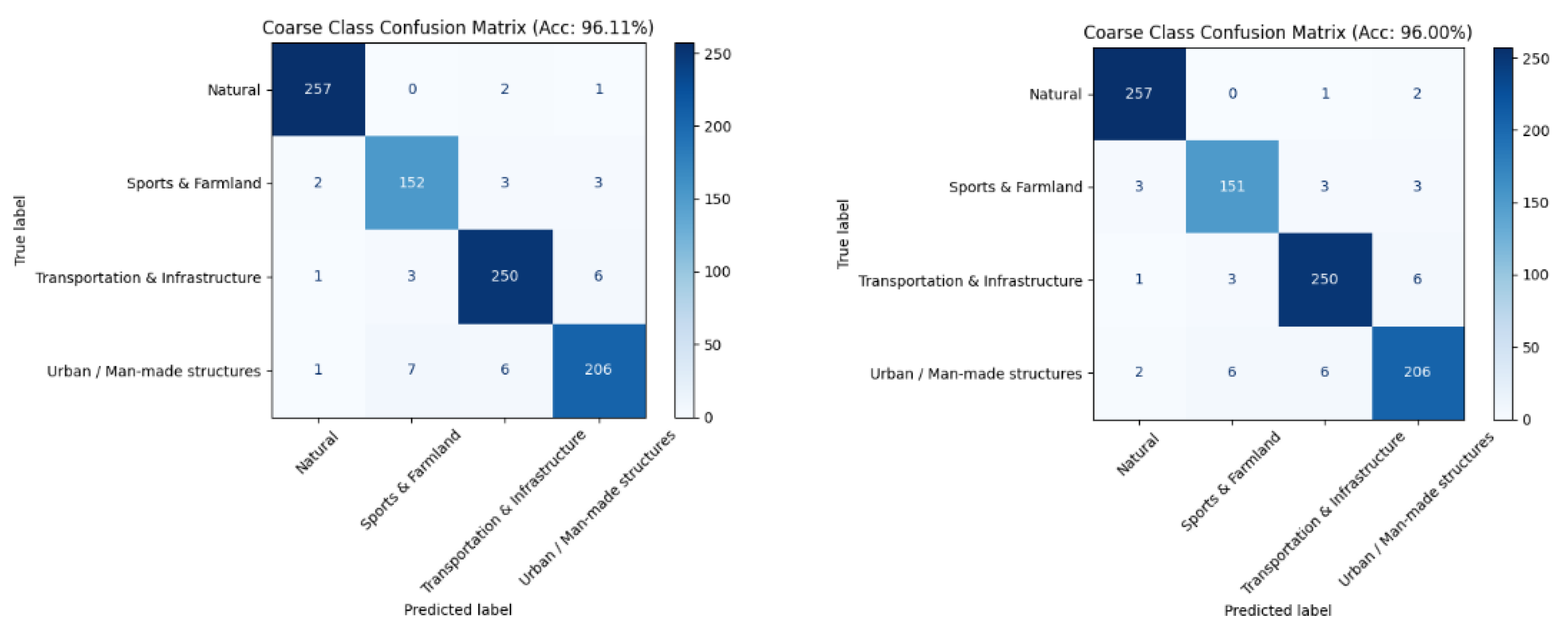

4.2.3. Effect of Model Size

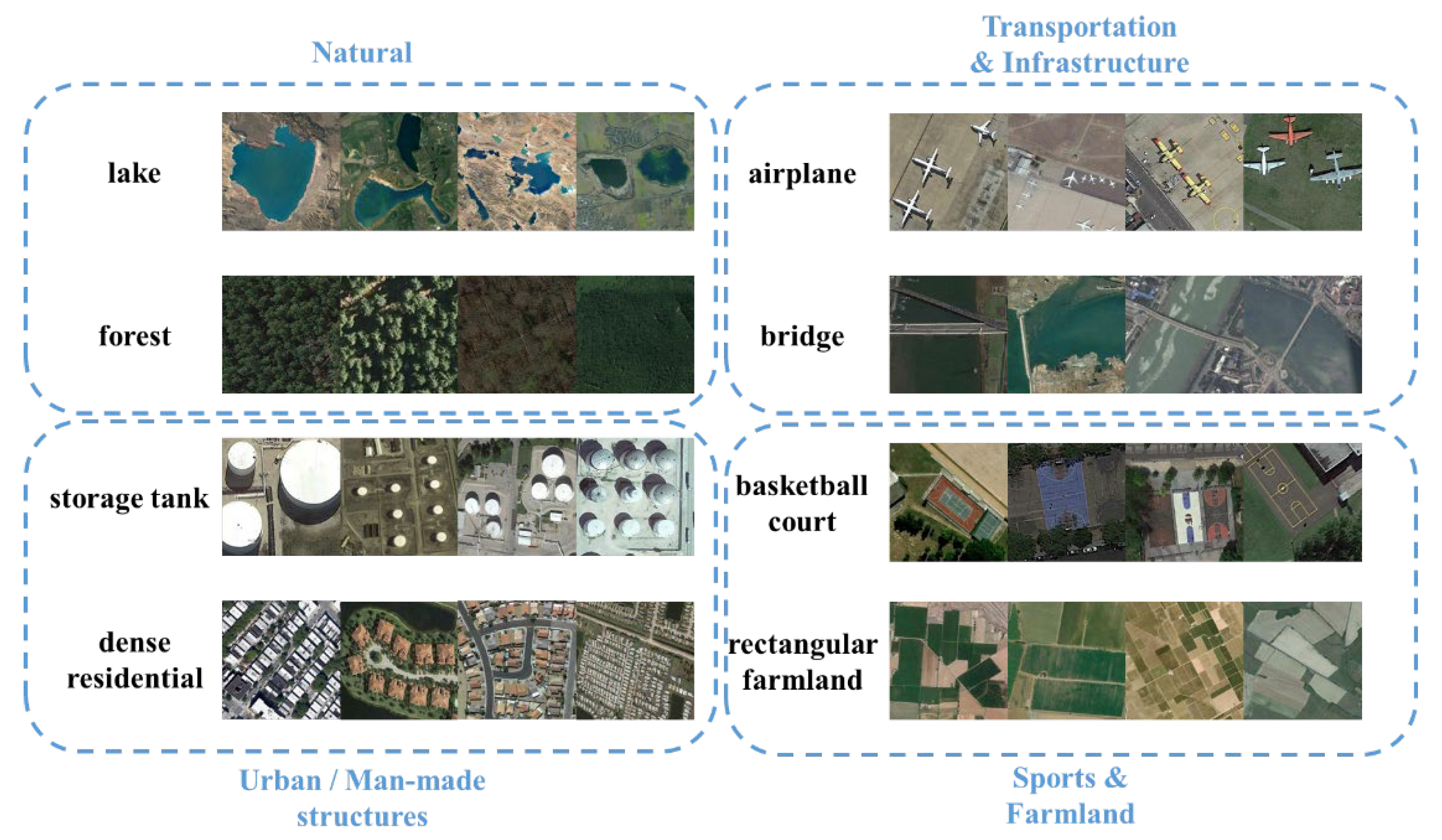

4.2.4. Data Version Impact

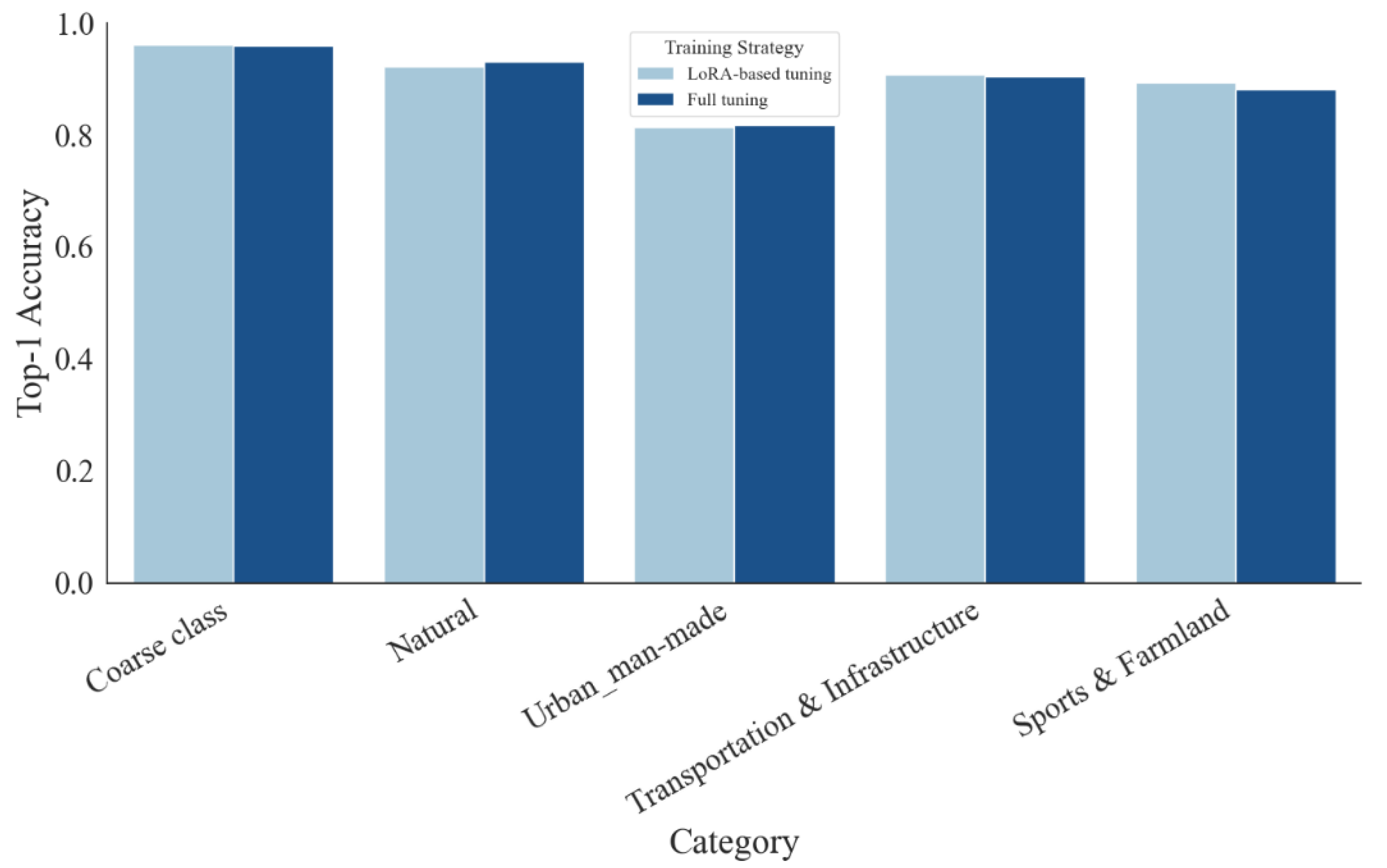

4.2.5. Training Strategy Comparison

4.2.6. Comparison with Classical CNNs

4.2.7. Data Efficiency Under Limited Labels

4.2.8. Cross-Domain Generalization

4.3. Hierarchical Multi-Label Extension

- Start from the root; apply a calibrated threshold for each node.

- If , expand to its children; otherwise prune the subtree.

- Return all activated leaves and (optionally) their ancestors. A simple repair step sets to satisfy ancestry.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Effectiveness of Hierarchical Prompting

5.2. Trade-offs Between Model Size and Accuracy

5.3. Limitations and Potential Failure Cases

5.4. Future Work

Appendix A. Prompt Templates

A.1. Prompt: Direct Category Selection

A.2. Prompt: Coarse-to-Fine Step-by-Step Classification

A.3. Prompt: Streamlined Coarse-to-Fine Reasoning

Appendix B. Dataset Variant Design and Prompt–Variant Alignment

B.1. Goals

B.2. Variant Construction and Prompt Rationale (Table A1).

| Variant | Design goal (robustness axis) | Construction rule (leakage control) | Prompt alignment (why this prompt) | Artifacts |

| Baseline comparability | Standard random split; no augmentation | Generic flat prompt, used as the neutral reference | Split index (train/val/test) | |

| Orientation/flip invariance stress | Global rotations (0/90/180/270) and H/V flips applied naïvely | Add orientation-invariant wording and spatial cues | Augmentation list | |

| Leakage-safe augmentation | Split-before-augment: apply all augmentations only to training; validation/test untouched | Keep wording to isolate protocol effect (naïve vs. leakage-safe) | Train-only aug manifests | |

| Semantic disambiguation / label noise | Merge near-synonymous/ambiguous classes; remove borderline samples; run near-duplicate audit across splits | Emphasize structural/semantic descriptors in a coarse→fine template | Cleaned indices + audit logs | |

| Clean + invariance (combined) | Apply’s leakage-safe augmentation aftercleaning | Streamlined hierarchical prompt (coarse→fine) for efficiency and clarity | All manifests & scripts |

B.3. Leakage Prevention and Duplicate Audit

B.4. Reproducibility

Appendix C. Label Mapping for External Datasets

C.1. Mapping Policy and Notation

C.2. UC Merced (UCM) → Our Hierarchy / AID Fine Classes

- 1)

- Agriculture — generic farmland (AID distinguishes circular vs. rectangular farmland).

- 2)

- Buildings — generic built-up category (AID uses more specific urban subclasses).

| UCM Class | Coarse Class | UCM Class | Coarse Class | UCM Class | Coarse Class |

| Agriculture | Sports & Farmland | Forest | Natural | Overpass | Transportation & Infrastructure |

| Airplane | Transportation & Infrastructure | Freeway | Transportation & Infrastructure | Parking lot | Transportation & Infrastructure |

| Baseball diamond |

Sports & Farmland | Golf course | Sports & Farmland | River | Natural |

| Beach | Natural | Harbor | Transportation & Infrastructure | Runway | Transportation & Infrastructure |

| Buildings | Urban / Man-made | Intersection | Transportation & Infrastructure | Sparse residential |

Urban / Man-made |

| Chaparral | Natural | Medium residential | Urban / Man-made | Storage tanks | Urban / Man-made |

| Dense residential |

Urban / Man-made | Mobile home park | Urban / Man-made | Tennis court | Sports & Farmland |

C.3. WHU-RS19 → Our Hierarchy / AID Fine Classes

- 1)

- Farmland — generic farmland (AID splits by geometry).

- 2)

- Park — urban green/parkland (no exact AID fine class).

- 3)

- Residential area — density not specified (AID separates dense/medium/sparse).

- 4)

- (Ambiguity handled at fine level but irrelevant here) Football field — could appear with or without athletics track; we evaluate at the coarse level.

| WHU Class | Coarse Class | WHU Class | Coarse Class | WHU Class | Coarse Class |

| Airport | Transportation & Infrastructure | Football field | Sports & Farmland | Parking lot | Transportation & Infrastructure |

| Beach | Natural | Forest | Natural | Pond | Natural |

| Bridge | Transportation & Infrastructure | Industrial area | Urban / Man-made | Port | Transportation & Infrastructure |

| Commercial area | Urban / Man-made | Meadow | Natural | Railway station | Transportation & Infrastructure |

| Desert | Natural | Mountain | Natural | Residential area | Urban / Man-made |

| Farmland | Sports & Farmland | Park | Urban / Man-made | River | Natural |

| - | - | Viaduct | Transportation & Infrastructure | - | - |

C.4. RSSCN7 → Our Hierarchy / AID Fine Classes

- 1)

- Field — generic farmland (AID splits circular/rectangular).

- 2)

- Residential — density not specified (AID distinguishes dense/medium/sparse).

| RSSCN7 Class | Coarse Class | RSSCN7 Class | Coarse Class | RSSCN7 Class | Coarse Class |

| Grass | Natural | Industrial | Urban / Man-made | Residential | Urban / Man-made |

| River | Natural | Field | Sports & Farmland | Parking | Transportation & Infrastructure |

| - | - | Forest | Natural | - | - |

References

- G. Cheng, J. Han, and X. Lu, “Remote sensing image scene classification: Benchmark and state of the art,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 105, no. 10, pp. 1865–1883, Oct. 2017.

- G.-S. Xia, J. Hu, F. Hu, B. Shi, X. Bai, Y. Zhong, L. Zhang, and X. Lu, “AID: A Benchmark Dataset for Performance Evaluation of Aerial Scene Classification,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 3965–3981, Jul. 2017.

- A. Radford, J. W. Kim, C. Hallacy, A. Ramesh, G. Goh, S. Agarwal, and I. Sutskever, “Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision,” in Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Jul. 2021.

- J.-B. Alayrac, J. Donahue, P. Luc, A. Miech, I. Barr, Y. Li, et al., “Flamingo: A Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2204.14198, 2022.

- Yang, Yi and S. Newsam. “Bag-of-visual-words and spatial extensions for land-use classification.” ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Advances in Geographic Information Systems (2010).

- M. Castelluccio, G. Poggi, C. Sansone, and L. Verdoliva, “Land Use Classification in Remote Sensing Images by Convolutional Neural Networks,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:1508.00092, 2015.

- S. Basu, S. Ganguly, S. Mukhopadhyay, et al., “DeepSat: A Learning Framework for Satellite Imagery,” in Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems (SIGSPATIAL), 2015.

- G.-S. Xia, J. Hu, F. Hu, et al., “AID: A Benchmark Dataset for Performance Evaluation of Aerial Scene Classification,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 3965–3981, Jul. 2017.

- Chen, Ting et al. “A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations.” ArXiv abs/2002.05709 (2020): n. pag.

- J.-B. Alayrac, J. Donahue, P. Luc, et al., “Flamingo: A Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2204.14198, 2022.

- T. Zhao, X. Wu, et al., “Exploring Prompt-Based Learning for Text-to-Image Generation,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2203.08519, 2022.

- J. Gao, X. Han, et al., “Scaling Instruction-Finetuned Language Models,” arXiv preprint, 2022.

- X. Li, C. Yin, et al., “Decomposed Prompt Learning for Language Models,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2022.

- E. Hu, Y. Shen, P. Wallis, et al., “LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2106.09685, 2021.

- Dettmers, Tim, et al. “Qlora: Efficient finetuning of quantized llms.” Advances in neural information processing systems 36 (2023): 10088-10115.

- Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, et al., “RemoteCLIP: A Vision–Language Foundation Model for Remote Sensing,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2408.05554, 2024.

- Z. Luo, Y. Chen, et al., “RS5M: A Large-Scale Vision–Language Dataset for Remote Sensing,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2024.

- CSIG-RS Lab, “RSGPT: Visual Remote Sensing Chatbot,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 2024.

- Y. Li, J. Zhang, et al., “GeoChat: Grounded Vision–Language Model for Remote Sensing,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, early access, 2024.

- Z. Luo, X. Xie, et al., “VRSBench: A Versatile Vision–Language Benchmark for Remote Sensing,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2023.

- Y. Bazi, M. Al Rahhal, et al., “RS-LLaVA: A Large Vision–Language Model for Joint Captioning and VQA in Remote Sensing,” Remote Sensing, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 1477, 2024.

- Z. Zhang, X. Li, et al., “EarthGPT: A Universal MLLM for Multi-Sensor Remote Sensing,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2401.16822, 2024.

- G.-S. Xia, J. Hu, F. Hu, et al., “NWPU-RESISC45: A Public Dataset for Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, 2017.

- P. Helber, B. Bischke, A. Dengel, and D. Borth, “EuroSAT: A Novel Dataset and Deep Learning Benchmark for Land Use and Land Cover Classification,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2019.

- J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans, et al., “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint, 2022.

- S. Yao, Y. Yu, J. Zhao, et al., “Tree-of-Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint, 2023.

- B. Barz and J. Denzler, “Do We Train on Test Data? Purging CIFAR of Near-Duplicates,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:1902.00423, 2019.

- C. Zauner, “Implementation and Benchmarking of Perceptual Image Hash Functions,” Master’s thesis, 2010.

- S. Rajbhandari, J. R. Child, D. Li, et al., “ZeRO: Memory Optimizations Toward Training Trillion-Parameter Models,” in Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (SC ’20), 2020.

- T. Dettmers, M. Lewis, S. Shleifer, and L. Zettlemoyer, “LLM.int8(): 8-Bit Matrix Multiplication for Transformers at Scale,” arXiv preprint, 2022.

- Xu, Y., Xie, L., Gu, X., Chen, X., Chang, H., Zhang, H., Chen, Z., Zhang, X., & Tian, Q. (2024). QA-LoRA: Quantization-Aware Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. ICLR 2024.

- W. Zhao, H. Xu, et al., “SWIFT: A Scalable Lightweight Infrastructure for Fine-Tuning,” in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), 2025.

- K. He et al., “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition,” CVPR, 2016.

- M. Sandler et al., “MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks,” CVPR, 2018.

- M. Tan and Q. Le, “EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for CNNs,” ICML, 2019.

- Neumann M, Pinto A S, Zhai X, et al. In-domain representation learning for remote sensing[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.06721, 2019.

- D. Dai and W. Yang, “Satellite image classification via two-layer sparse coding with biased image representation,” IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 173–176, 2011.

- Q. Zou, L. Ni, T. Zhang, and Q. Wang, “Deep learning based feature selection for remote sensing scene classification,” IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 12, no. 11, pp. 2321–2325, Nov. 2015, . [CrossRef]

| Version | Key Operations | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Original dataset | 45 classes, 100 images per class; no augmentation data | |

| Data augmentation | Each image transformed with 6 operations: rotate (0°, 90°, 180°, 270°), horizontal flip, vertical flip | |

| Augmentation after split [27] | Training and testing sets split first; augmentation applied only on training set | |

| Class merging data cleaning | Merge semantically similar classes (e.g., church + palace → edifice); remove ambiguous samples | |

| Post-cleaning augmentation | Based on V_3, split into training and testing sets; apply augmentation on training set |

| Version | Main Strategy | Key Features | Output Format |

| Direct classification | Select one category from a list without explanation | Category name only | |

| Coarse-to-fine hierarchical reasoning | Step 1: Coarse classification into 4 major groups; Step 2: Fine-grained classification within selected group; Reasoning required | |Coarse class|Fine class|Reasoning| | |

| Simplified hierar-chical reasoning | Same two-step classification as but with streamlined instructions to reduce cognitive load | |Coarse class|Fine class|Reasoning| |

|

Prompt Version |

|||

| Qwen2VL-72B | 29.33% | 52.00% | 51.78% |

| Qwen2.5VL-7B | 90.67% | 96.44% | 96.11% |

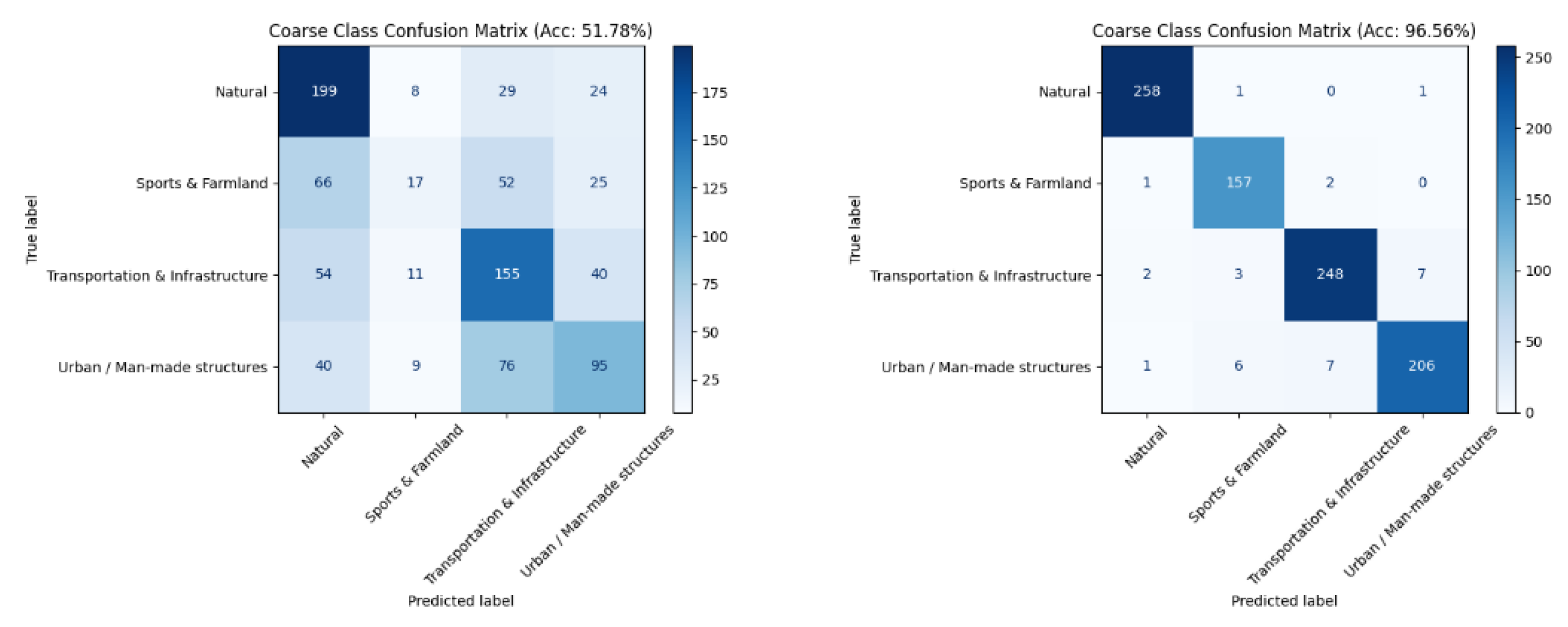

| Model Architecture | Qwen2VL | Qwen2.5VL | Improvement |

| Coarse class | 51.78% | 96.56% | +44.78% |

| Natural | 44.62% | 93.85% | +49.23% |

| Urban / Man-made | 13.64% | 78.64% | +65.00% |

| Transportation & Infrastructure | 18.08% | 91.15% | +73.07% |

| Sports & Farmland | 2.50% | 95.00% | +92.50% |

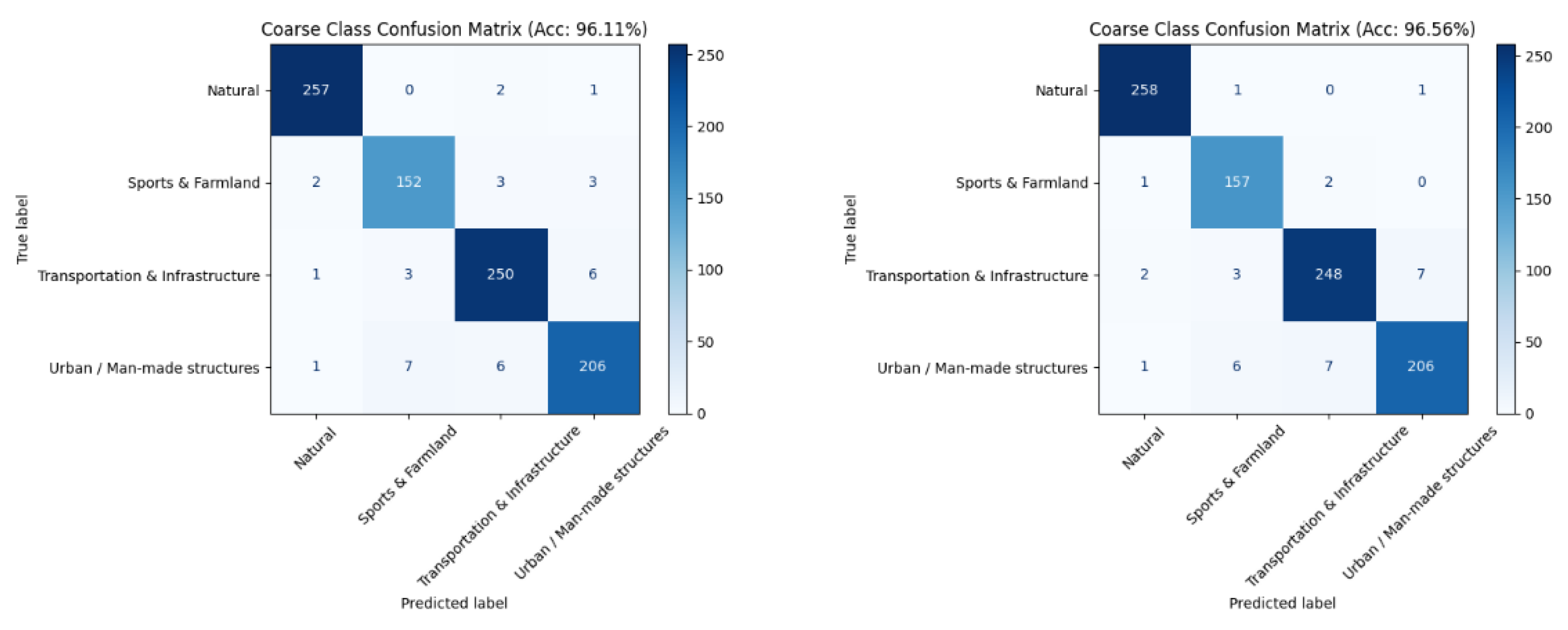

| Model Size | 7B | 72B | Improvement |

| Coarse class | 96.11% | 96.56% | +0.45% |

| Natural | 92.31% | 93.85% | +1.54% |

| Urban / Man-made | 81.36% | 78.64% | -2.72% |

| Transportation & Infrastructure | 90.77% | 91.15% | +0.38% |

| Sports & Farmland | 89.38% | 95.00% | +5.62% |

| Training Strategy | LoRA | Full | Improvement |

| Coarse class | 96.11% | 96.00% | -0.11% |

| Natural | 92.31% | 93.08% | +0.77% |

| Urban / Man-made | 81.36% | 81.82% | +0.46% |

| Transportation & Infrastructure | 90.77% | 90.38% | -0.39% |

| Sports & Farmland | 89.38% | 88.12% | -1.26% |

| Model | Trainable Params (M) | Peak Mem (GB) | Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Macro-F1 (%) |

| ResNet-50 (ImageNet) | 23.60 | 3.139 | 90.67 | 90.46 |

| MobileNetV2 (ImageNet) | 2.282 | 2.626 | 89.78 | 89.81 |

| EfficientNet-B0 (ImageNet) | 4.065 | 2.968 | 91.11 | 91.09 |

| Qwen2.5VL-7B+LoRA+HPE | 8.39 | 14.00 | 91.33 | 91.32 |

| Labeled (%) | ResNet-50 | MobileNetV2 | EfficientNet-B0 | Qwen2.5VL-7B + LoRA |

| 1% | 27.89 / 26.25 | 53.44 / 53.46 | 29.00 / 28.81 | 81.44 / 82.63 |

| 5% | 49.33 / 47.63 | 67.00 / 65.94 | 53.67 / 53.02 | 87.22 / 87.90 |

| 10% | 69.44 / 69.44 | 81.11 / 80.98 | 75.00 / 74.51 | 85.22 / 84.92 |

| 25% | 84.33 / 84.22 | 90.00 / 89.94 | 86.22 / 86.13 | 87.11 / 87.04 |

| Dataset | Few-shot LoRA | Zero-shot | ||

| Coarse Top-1 | Coarse F1 | Coarse Top-1 | Coarse F1 | |

| AID- | 97.78 | 97.67 | - | - |

| UCM | 95.70 | 95.55 | 87.20 | 87.04 |

| WHU | 96.81 | 95.92 | 93.90 | 91.98 |

| RSSCN7 | 82.37 | 62.64 | 74.07 | 28.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).