Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Characteristics

| Parameter | Dementia & hyperlipidemia (n=109) | Hyperlipidemia (n=94) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male / Female, sex | 47/62 (43.1%/56.9%) | 37/57 (39.4%/60,6%) | p=0.588 |

| Age, y | 70.8 (±11.5) | 64.1 (±12.9) | p <0.05 |

| Weight, kg | 78.0 (70.0÷86.5) | 79.5 (68.0÷95.5) | p=0.420 |

| Diabetes | 13 (11.9%) | 27 (28.7%) | p <0.05 |

| Hypertension | 20 (18.4%) | 68 (72.3%) | p <0.05 |

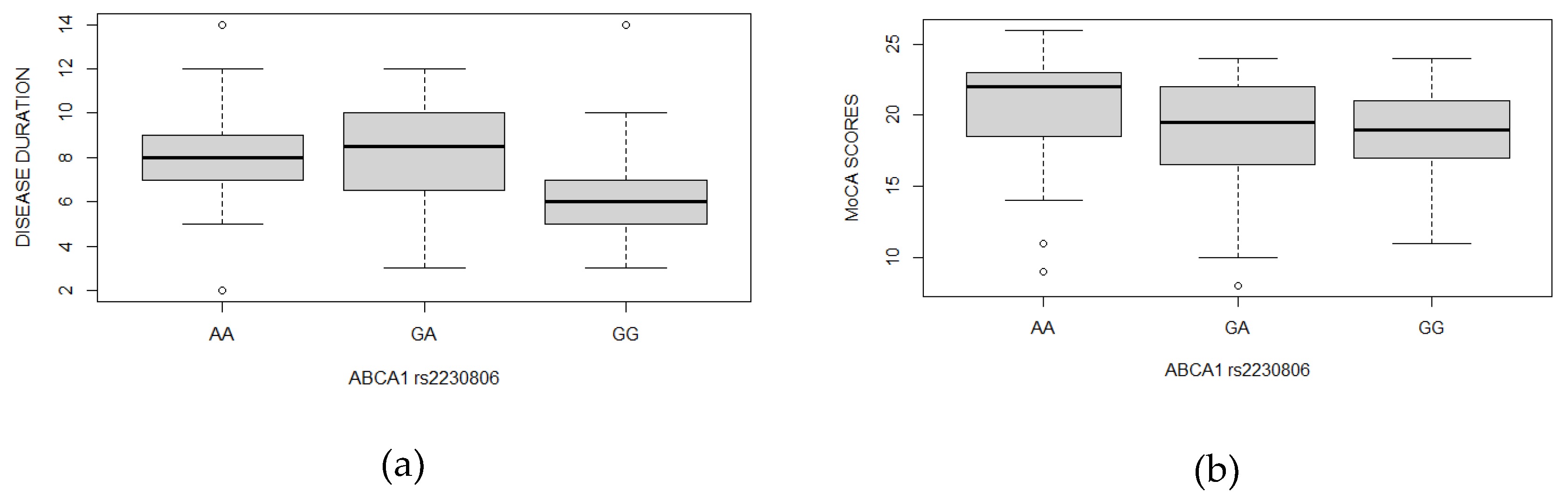

| Age of dementia diagnosis, y | 65.8 (±9.8) | - | |

| Dementia duration, y | 7.8 (±2.4) | - | |

| MMSE score | 18.1 (±4.0) | - | |

| MoCA score | 19.0 (±4.1) | - | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 231.0 (220.0÷244.0) | 146.0 (118.0÷168.0) | p <0.05 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 55.0 (49.0÷64.0) | 43.0 (32.0÷56.0) | p <0.05 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 140.7 (±21.3) | 77.3 (±34.6) | p <0.05 |

| Triglicerydes, mg/dl | 195.2 (±53.1) | 130.7 (±75.5) | p <0.05 |

2.2. Polymorphisms

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Genotyping

4.3. Laboratory Markers

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 24S-OHC | 24(S)-Hydroxycholesterol |

| AD | Alzheimer disease |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| Aβ | Amyloid β |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| HDL | High density lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low density lipoprotein |

| MMSE | Mini–Mental State Examination |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- WHO. Dementia. March 15, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed in September 2024).

- WHO. The top 10 causes of death. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed September 2024).

- Nordestgaard, L.T.; Christoffersen, M.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Shared Risk Factors between Dementia and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 29, 9777. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, D.; Li, C.; Xie, W.; Zheng, F. Association between Age at Diagnosis of Hyperlipidemia and Subsequent Risk of Dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2024, 25, 104960. [CrossRef]

- van Gennip, A.C.E.; van Sloten, T.T.; Fayosse, A.; Sabia, S.; Singh-Manoux, A. Age at cardiovascular disease onset, dementia risk, and the role of lifestyle factors. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 1693-1702. [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Sehgal, A.; Kumar, A.; Uddin, M.S.; Bungau, S. The Interplay of ABC Transporters in Aβ Translocation and Cholesterol Metabolism: Implicating Their Roles in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 1564-1582. [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, A.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; Sleegers, K. The role of ABCA7 in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from genomics, transcriptomics and methylomics. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 201-220. [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T.; Holm, M.L.; Kanekiyo, T. ABCA7 and pathogenic pathways of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 27. [CrossRef]

- Giau, V. V.; Bagyinszky, E.; An, S. S.; Kim, S. Y. Role of apolipoprotein E in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 2015, 11, 1723–1737. [CrossRef]

- Passero, M.; Zhai, T.; Huang, Z. Investigation of Potential Drug Targets for Cholesterol Regulation to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 20, 6217. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.M.; Pikuleva, I.A. Cholesterol 24-Hydroxylation by CYP46A1: Benefits of Modulation for Brain Diseases. Neurotherapeutics. 2019, 16, 635-648. [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Zhao, C.; Wang, L.; Xiao, Z.; Rong, J.; Xia, X.; Chen, Z.; Pfister, S.K.; Mast, N.; Yutuc, E.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Shao,T.; Warnock, G.I.; Dawoud, A.; Connors, T.R.; Oakley, D.H.; Wei, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, H.; Davenport, A.T.; Daunais, J.B.; Van, R.S.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.R.; Gebhard, C.; Pikuleva, I.; Levey, A.I.; Griffiths, W.J.; Liang, S.H. Assessment of cholesterol homeostasis in the living human brain. Sci Transl Med. 2022, 14, 9967. [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, M.; Tachibana, M.; Kanekiyo, T.; Bu, G. Role of LRP1 in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from clinical and preclinical studies. J Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 1267-1281. [CrossRef]

- Rauch, J. N.; Luna, G; Guzman, E.; Audouard, M.; Challis, C.; Sibih, Y. E.; Leshuk, C.; Hernandez, I.; Wegmann, S.; Hyman, B. T.; Gradinaru, V.; Kampmann, M.; Kosik, K. S. LRP1 is a master regulator of tau uptake and spread. Nature, 2020, 580, 381–385. [CrossRef]

- Knight, B.L. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1: regulation of cholesterol efflux. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004, 32, 124-127. [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Albavera, L.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; Medina-Leyte, D. J.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T. The Role of the ATP-Binding Cassette A1 (ABCA1) in Human Disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 2021, 22, 1593. [CrossRef]

- Akram, A; Schmeidler, J.; Katsel, P.; Hof, P.R.; Haroutunian, V. Increased expression of cholesterol transporter ABCA1 is highly correlated with severity of dementia in AD hippocampus. Brain Res. 2010, 1318, 167-177. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.A.; Hong, M.G.; Eriksson, U.K.; Blennow, K.; Bennet, A.M.; Johansson, B.; Malmberg, B,; Berg, S.; Wiklund, F.; Gatz, M.; Pedersen, N.L.; Prince, J.A. A survey of ABCA1 sequence variation confirms association with dementia. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30, 1348-54. [CrossRef]

- Elali, A.; Rivest, S. The role of ABCB1 and ABCA1 in beta-amyloid clearance at the neurovascular unit in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in physiology, 2013, 4, 45. [CrossRef]

- Zargar, S.; Wakil, S.M.; Mobeirek, A.F.; Al-Jafari, A.A. Involvement of ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A polymorphism with susceptibility to coronary artery disease. Biomedical reports, 2013, 16, 883-888 . [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Jia, A.; Yu, L.; Muhammad, I.; Zeng, W.; Song, Y. Associations of the ABCA1 gene polymorphisms with plasma lipid levels. Medicine, 2018, 97. [CrossRef]

- Leszek, J.; Mikhaylenko, E.V.; Belousov, D.M.; Koutsouraki, E.; Szczechowiak, K.; Kobusiak-Prokopowicz, M.; Mysiak, A.; Diniz, B.; Somasundaram, S.G.; Kirkland, C.E.; Aliev, G. The Links between Cardiovascular Diseases and Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Neuropharmacology, 2020, 19, 152 – 169. [CrossRef]

- Karasinska, J.M.; Haan, W.D.; Franciosi, S.; Ruddle, P.; Fan, J.; Kruit, J.K.; Stukas, S.; Lütjohann, D.; Gutmann, D.H.; Wellington, C.L.; Hayden, M.R. ABCA1 influences neuroinflammation and neuronal death. Neurobiology of Disease, 2013, 54, 445-455. [CrossRef]

- Fitz, N. F.; Cronican, A. A.; Saleem, M.; Fauq, A. H.; Chapman, R.; Lefterov, I.; Koldamova, R. Abca1 deficiency affects Alzheimer’s disease-like phenotype in human ApoE4 but not in ApoE3-targeted replacement mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2012, 32, 13125–13136. [CrossRef]

- Koldamova, R.; Fitz, N. F.; Lefterov, I. The role of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 in Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegeneration. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 2010, 1801, 824–830. [CrossRef]

- Koldamova, R.; Fitz, N. F.; Lefterov, I. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1: from metabolism to neurodegeneration. Neurobiology of disease, 2014, 72, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Donkin, J. J.; Stukas, S.; Hirsch-Reinshagen, V.; Namjoshi, D.; Wilkinson, A.; May, S.; Chan, J.; Fan, J.; Collins, J.; Wellington, C. L. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 mediates the beneficial effects of the liver X receptor agonist GW3965 on object recognition memory and amyloid burden in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 mice. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2010, 285, 34144–34154. [CrossRef]

- Fehér, Á.; Giricz, Z.; Juhász, A.; Pákáski, M.; Janka, Z.; Kálmán, J. ABCA1 rs2230805 and rs2230806 common gene variants are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience letters, 2018, 664, 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, P.; Zeng, H.; Chen, W. Association studies of several cholesterol-related genes (ABCA1, CETP and LIPC) with serum lipids and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Lipids in health and disease, 2012, 11, 163. [CrossRef]

- Wavrant-De Vrièze, F.; Compton, D.; Womick, M.; Arepalli, S.; Adighibe, O.; Li, L.; Pérez-Tur, J.; Hardy, J. ABCA1 polymorphisms and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience letters, 2007, 416, 180–183. [CrossRef]

- Sundar, P. D.; Feingold, E.; Minster, R. L.; DeKosky, S. T.; Kamboh, M. I. Gender-specific association of ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (ABCA1) polymorphisms with the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging, 2007, 28, 856–862. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovic, N. The Challenges of Diagnosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. US neurology. 2018, 14, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N. J.; Puig-Pijoan, A.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Fernández-Lebrero, A.; García-Escobar, G.; González-Ortiz, F.; Kac, P. R.; Brum, W. S.; Benedet, A. L.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Day, T. A.; Vanbrabant, J.; Stoops, E.; Vanmechelen, E.; Triana-Baltzer, G.; Moughadam, S.; Kolb, H.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; Karikari, T. K.; Minguillon, C.; Suárez-Calvet, M. Plasma and CSF biomarkers in a memory clinic: Head-to-head comparison of phosphorylated tau immunoassays. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 2023, 19, 1913–1924. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Lucas, M.; Allué, J. A.; Sarasa, L.; Fandos, N.; Castillo, S.; Terencio, J.; Sarasa, M.; Tartari, J. P.; Sanabria, Á.; Tárraga, L.; Ruíz, A.; Marquié, M.; Seo, S. W.; Jang, H.; Boada, M.; & FACEHBI study group. Clinical performance of an antibody-free assay for plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 to detect early alterations of Alzheimer’s disease in individuals with subjective cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s research & therapy, 2023, 15, 2. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Role in lipid metabolism | Involvement in dementia | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA1 | Regulation of cholesterol, support ApoE lipidation | Influence for ApoE lipidation affect APP processing and Aβ cumulation | [6,8] |

| ABCA7 | Regulation of lipid metabolism, apolipoproteins lipidation | Phagocytic elimination of Aβ, suppression of AβPP proteolysis | [6,7,8] |

| ABCB1 | Efflux transporter, pharmacoresistance, detoxification, homeostasis maintaince in CNS | Transport of Aβ from neural processes to blood circulation | [6] |

| APOE | Lipid transporter protein | APOE E4 variant accelerate the accumulation, aggregation, and deposition of Aβ in the brain | [9] |

| CYP46A1 | Conversion cholesterol into form 24S-OHC capable of crossing blood-brain barrier | Decreased function leads to an increased production of Aβ and tau proteins | [10,11,12] |

| LRP1 | Internalization of lipoproteins into neurons, apoE receptor | Aβ deposition, tau regulation, brain homeostasis | [13,14] |

| Gene | rs code | Participants | Genotype frequency | p-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA1 | rs2230806 | AA | GA | GG | 0.004 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 39 (35.8%) | 36 (33.0%) | 34 (31.2%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 45 (47.8%) | 40 (42.6%) | 9 (9.6%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 37 (36.6%) | 44 (43.6%) | 20 (19.8%) | ||||||||

| ABCA1 | rs2422493 | CC | CT | TT | 0.066 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 34 (31.2%) | 51 (46.8%) | 24 (22.0%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 20 (21.3%) | 56 (59.6%) | 18 (19.1%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 20 (19.8%) | 49 (48.5%) | 32 (31.7%) | ||||||||

| ABCA7 | rs4147929 | AA | AG | GG | 0.561 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 3 (2.8%) | 35 (32.1%) | 71 (65.1%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 2 (2.1%) | 30 (31.9%) | 62 (66.0%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 3 (3.0%) | 23 (22.8%) | 75 (74.2%) | ||||||||

| ABCA7 | rs3752246 | CC | CG | GG | 0.493 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 71 (65.1%) | 36 (33.0%) | 2 (1.9%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 64 (68.1%) | 29 (30.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 77 (76.2%) | 23 (22.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | ||||||||

| ABCA7 | rs3764650 | GG | GT | TT | 0.446 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 1 (0.9%) | 17 (15.6%) | 91 (83.5%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (1.1%) | 11 (11.7%) | 82 (87.2%) | ||||||||

| Controls | - | 10 (9.9%) | 91 (90.1%) | ||||||||

| ABCB1 | rs1045642 | CC | CT | TT | 0.478 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 27 (24.8%) | 55 (50.4%) | 27 (24.8%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 28 (29.8%) | 44 (46.8%) | 22 (23.4%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 19 (18.8%) | 52 (51.5%) | 30 (29.7%) | ||||||||

| ABCB1 | rs1128503 | CC | CT | TT | 0.512 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 38 (34.9%) | 48 (44.0%) | 23 (21.1%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 38 (40.4%) | 48 (43.6%) | 15 (16.0%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 30 (29.7%) | 47 (46.5%) | 24 (23.8%) | ||||||||

| ABCB1 | rs2032582 | GG | GT | TT | 0.353 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 36 (33.6%) | 51 (47.7%) | 20 (18.7%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 44 (46.8%) | 37 (39.4%) | 13 (13.8%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 34 (33.7%) | 49 (48.5%) | 18 (17.8%) | ||||||||

| APOE | rs429358 rs7412 |

E2/E2 | E2/E3 | E2/E4 | E3/E3 | E3/E4 | E4/E4 | 0.224 | |||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | - | 16 (14.7%) | 5 (4.6%) | 77 (70.6%) | 7 (6.4%) | 4 (3.7%) | |||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (1.1%) | 6 (6.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 67 (71.3%) | 19 (20.2%) | - | |||||

| Controls | 1 (1.0%) | 7 (6.9%) | 1 (1.0%) | 86 (85.2%) | 6 (5.9%) | - | |||||

| CYP46A1 | rs754203 | AA | AG | GG | 0.148 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 51 (46.8%) | 52 (47.7%) | 6 (5.5%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 44 (46.8%) | 35 (37.2%) | 15 (16.0%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 48 (47.5%) | 40 (39.6%) | 13 (12.9%) | ||||||||

| LRP1 | rs1799986 | CC | CT | TT | 0.224 | ||||||

| Dementia & hyperlipidemia | 75 (68.8%) | 31 (28.4%) | 3 (2.8%) | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 73 (77.6%) | 17 (18.1%) | 4 (4.3%) | ||||||||

| Controls | 65 (64.4%) | 32 (31.6%) | 4 (4.0%) | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).