1. Introduction

CD44, a type I transmembrane glycoprotein, was first identified in the 1980s as a lymphocyte homing receptor [

1]. The human CD44 gene consists of multiple exons. Exons 1–5 encode the conserved extracellular domain, exons 16 and 17 encode the stalk region, exon 18 encodes the transmembrane domain, and exons 19 and 20 encode the cytoplasmic domain. The isoform composed of exons 1–5 and 16–20 is referred to as the standard form (CD44s), which is expressed in most cell types. Exons 6–15 undergo alternative splicing, resulting in multiple variant (CD44v) isoforms that are inserted between the extracellular and stalk regions [

2]. For instance, CD44v8–10 (also known as CD44E) is predominantly expressed in epithelial cells, whereas CD44v3–10, the largest isoform, is mainly expressed in keratinocytes [

3]. Aberrant expression of CD44v isoforms has been implicated in cancer progression [

4].

Pan-CD44, including CD44s and CD44v, interacts with hyaluronic acid (HA) via the conserved extracellular domain, which plays pivotal roles in cellular proliferation, migration, homing, and adhesion [

5]. The CD44v isoforms possess diverse oncogenic functions, including the promotion of cancer cell motility and invasiveness [

6], acquisition of cancer stem cell (CSC)-like properties [

4], and resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy [

7]. Each variant exon-encoded region plays an essential role in cancer progression. The v3-encoded region undergoes modification of heparan sulfate, enabling the recruitment of heparin-binding growth factors, including fibroblast growth factors. Therefore, the v3 region can amplify the downstream signaling of receptor tyrosine kinases [

8]. The v6-encoded region is critical for activation of c-MET via a ternary complex formation with the ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [

9]. Moreover, the v8–10-encoded region interacts with xCT, a cystine–glutamate transporter, and plays pivotal roles in the reduction of oxygen species through promotion of cystine uptake and glutathione synthesis [

10].

CSCs drive tumor initiation and metastasis [

11,

12]. CD44 has been implicated as a cell surface CSC marker in various carcinomas [

3]. In colorectal cancer, the CSCs express CD44v6, which is essential for their migration and metastasis [

13]. Although CD44v6 expression is relatively low in the primary tumors, it distinctly marks the clonogenic CSC subpopulation [

14]. Cytokines such as HGF derived from the tumor microenvironment, upregulate CD44v6 expression in the CSCs via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby promoting migration and metastasis [

14]. In patient cohorts, CD44v6 expression is an independent negative prognostic marker [

14]. Therefore, CD44v6 has been implicated as an essential target for tumor diagnosis and therapy.

Anti-CD44v6 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), including clones VFF4, VFF7, and VFF18, have been developed and primarily utilized for tumor diagnosis and therapeutic applications. The VFF series of mAbs were generated by immunizing animals with bacterially expressed CD44v3–10 fused to glutathione S-transferase [

15,

16]. Among them, VFF4 and VFF7 were employed in immunohistochemical analysis [

17]. VFF18 was shown to bind specifically to fusion proteins, containing the variant 6-encoded region. Moreover, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using synthetic peptides spanning this region identified the WFGNRWHEGYR sequence as the VFF18 epitope [

15].

VFF18 (mouse IgG

1) was further humanized and developed to BIWA-4 (bivatuzumab) [

18]. Clinical trials of the BIWA-4 conjugated with mertansine (bivatuzumab mertansine) were conducted for the treatment of solid tumors. But they were discontinued due to the skin toxicities [

19,

20]. These adverse effects were attributed to the accumulation of the mertansine payload in normal skin squamous epithelium [

19,

20]. In addition, human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells have been shown to express high levels of CD44 mRNA as a result of reduced CpG island methylation within the promoter region [

21]. Notably, elevated CD44v6 expression was detected in AML patients harboring FLT3 or DNMT3A mutations [

21]. Consequently, a modified version of BIWA-4, designated BIWA-8, was developed to generate chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) targeting CD44v6 in AML. These CD44v6-directed CAR-T cells demonstrated strong anti-leukemic activity [

21,

22], suggesting that CD44v6 is a promising therapeutic target for AML with FLT3 or DNMT3A mutations. Moreover, CD44v6 CAR-T cells also exhibited significant antitumor efficacy in xenograft models of lung and ovarian cancers [

23]. The safety and effectiveness of CD44v6 CAR-T treatment in patients with advanced CD44v6-positive solid tumors are being evaluated in the Phase I/II clinical studies [

24]. Moreover, BIWA-8-based CAR-NK therapy also showed effectiveness in eliminating CD44v6-positive cancer cell lines [

25]. Accordingly, VFF18-derived BIWA-4 or BIWA-8-based therapies have been evaluated in the clinic.

We previously generated a series of highly sensitive and specific mAbs against CD44v by immunizing mice with Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cells stably overexpressed CD44v3–10 (CHO/CD44v3–10). The critical epitopes recognized by these mAbs were determined by ELISA and further characterized through flow cytometry, western blotting, and immunohistochemistry [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Among the established clones, C

44Mab-9 (mouse IgG

1, κ) specifically bound to a peptide corresponding to the v6-encoded region [

29]. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that C

44Mab-9 recognized both CHO/CD44v3–10 cells and colorectal cancer cell lines. Moreover, C

44Mab-9 successfully detected endogenous CD44v6 in colorectal cancer tissues by immunohistochemistry. Collectively, these findings indicate that C

44Mab-9 is a valuable mAb for detecting CD44v6 in a variety of experimental and diagnostic applications.

In the present study, we engineered a mouse IgG2a version of C44Mab-9 (designated C44Mab-9-mG2a) to enhance effector functions. We then evaluated its antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and antitumor efficacy in xenograft models of gastric and colorectal cancers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

CHO-K1 and colorectal cancer cell lines (COLO201 and COLO205) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). A human gastric cancer cell line (NUGC-4) was obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (Osaka, Japan). CHO/CD44v3–10 was established previously [

28].

NUGC-4 were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). CHO/CD44v3–10, CHO-K1, COLO201, and COLO205 were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). All culture media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air.

2.2. Recombinant mAb Production

An anti-CD44v6 mAb, C

44Mab-9 (mouse IgG

1, κ) was previously established [

29]. To create the mouse IgG

1 version (C

44Mab-9) and mouse IgG

2a version (C

44Mab-9-mG

2a), the V

H cDNA of C

44Mab-9 and the C

H of mouse IgG

1 or IgG

2a were cloned into the pCAG-Neo vector [FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Wako), Osaka, Japan]. Similarly, the V

L cDNA of C

44Mab-9 and the C

L of the mouse kappa chain were cloned into the pCAG-Ble vector (Wako). The antibody expression and purification were performed using the ExpiCHO Expression System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), as described previously [

30]. C

44Mab-9 and C

44Mab-9-mG

2a were purified using Ab-Capcher (ProteNova Co., Ltd., Kagawa, Japan). A control mouse IgG

2a (mIgG

2a) mAb, PMab-231 (mouse IgG

2a, κ, an anti-tiger podoplanin mAb) was previously produced [

31].

2.3. ELISA

Twenty synthesized CD44v6 peptides [CD44v6 p351-370 wild-type (WT) and the alanine-substituted mutants] (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) were immobilized onto Nunc Maxisorp 96-well immunoplates (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) at a concentration of 1 µg/mL for 30 min at 37°C. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 (PBST; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) using a Microplate Washer, HydroSpeed (Tecan, Zürich, Switzerland), the wells were blocked with PBST containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min at 37°C. C44Mab-9 (1 µg/mL) was then added to each well, followed by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulins (1:2000 dilution; Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The enzymatic reaction was developed using the ELISA POD Substrate TMB Kit (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.), and the optical density at 655 nm was recorded with an iMark microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA).

2.4. Flow Cytometry

Cells, collected by brief incubation with a solution containing 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and 0.25% trypsin, were washed with a blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.1% BSA). The cells were treated with primary mAbs for 30 minutes at 4 °C and were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA). The data were obtained using an SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The dissociation constant

(KD) value was also determined by flow cytometry [

26].

2.5. Measurement of ADCC by C44Mab-9-mG2a

The animal experiments were performed in compliance with institutional regulations and ethical standards aimed at minimizing pain and distress and were approved by the Institutional Committee for Animal Experiments of the Institute of Microbial Chemistry (Numazu, Japan; approval number: 2025-029). Female BALB/c nude mice, five weeks of age, were obtained from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). Splenocytes, used as effector cells, were prepared as previously described [

30]. The ADCC activity of C

44Mab-9-mG

2a was evaluated as follows: Calcein AM-labeled target cells (CHO/CD44v3–10, NUGC-4, COLO201, and COLO205) were co-cultured with effector cells at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 50:1 in the presence of 100 μg/mL C

44Mab-9-mG

2a (n = 3) or control mIgG

2a (n = 3). After a 4.5-hour incubation, Calcein release into the medium was quantified using a microplate reader (Power Scan HT; BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Cytotoxicity was calculated as a percentage of lysis using the following formula: % lysis = (E − S)/(M − S) × 100, where E represents the fluorescence intensity from co-cultures of effector and target cells, S denotes the spontaneous fluorescence from target cells alone, and M corresponds to the maximum fluorescence obtained after complete lysis using a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was evaluated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

2.6. Measurement of CDC by C44Mab-9-mG2a

Calcein AM-labeled target cells (CHO/CD44v3–10, NUGC-4, COLO201, and COLO205) were seeded and incubated with rabbit complement (final concentration, 10%; Low-Tox-M Rabbit Complement, Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, ON, Canada) in the presence of 100 μg/mL C44Mab-9-mG2a (n = 3) or control mIgG2a (n = 3). After incubation for 4.5 h at 37°C, Calcein release into the medium was quantified as described above.

2.7. Antitumor Activity of C44Mab-9-mG2a

The Institutional Committee for Animal Experiments of the Institute of Microbial Chemistry approved the animal experiment (approval numbers: 2025-011 and 2025-029). Throughout the study, mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions with an 11-hour light/13-hour dark cycle and were given food and water ad libitum. Body weight was monitored twice weekly, and overall health status was evaluated three times per week. Humane endpoints were defined as either a loss of more than 25% of the initial body weight and/or a tumor volume exceeding 3,000 mm3.

Female BALB/c nude mice (4 weeks old) were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. Tumor cells (0.3 mL of a 1.33 × 108 cells/mL suspension in DMEM) were mixed with 0.5 mL of BD Matrigel Matrix Growth Factor Reduced (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). A 100 μL aliquot of the mixture, containing 5 × 106 cells, was subcutaneously injected into the left flank of each mouse (day 0). To assess the antitumor activity of C44Mab-9-mG2a against CHO/CD44v3–10 and NUGC-4 tumor-bearing mice, they received intraperitoneal injections of 200 μg C44Mab-9-mG2a (n = 8) or control mIgG2a (n = 8) diluted in 100 μL PBS on days 7 and 14. Mice were euthanized on day 21 after tumor inoculation. In COLO201 and COLO205 tumor-bearing mice, 100 μg C44Mab-9-mG2a (n = 8) or control mIgG2a (n = 8) were intraperitoneally injected on days 7 and 14. Mice were euthanized on day 21 after tumor inoculation.

Tumor size was measured, and volume was calculated using the formula: volume = W2 × L / 2, where L represents the long diameter and W represents the short diameter. Data are shown as the mean ±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Among the CD44v isoforms, CD44v6 plays a pivotal role in cancer progression through binding to HGF, osteopontin, and other key cytokines secreted in the tumor microenvironment [

32]. In the presence of HGF, CD44v6 forms a ternary complex with c-MET, thereby enhancing the intracellular signaling [

9]. Moreover, increased MUC5AC expression was observed in breast cancer brain metastasis through c-MET signaling. MUC5AC promotes brain metastasis by interacting with the c-MET and CD44v6. Blocking the MUC5AC/c-MET/CD44v6 complex with a blood–brain barrier–permeable c-MET inhibitor, bozitinib, effectively reduces MUC5AC expression and decreases the metastatic potential of breast cancer cells to the brain [

33]. Additionally, CD44v6 expression was detected in a highly tumorigenic colorectal CSC population with metastatic potential [

14] and gastric CSCs [

34]. Therefore, targeting CD44v6 has been considered as an attractive target for mAb-based therapy. In this study, C

44Mab-9-mG

2a, a mouse IgG

2a version of a novel anti-CD44v6 mAb, was developed and evaluated. C

44Mab-9-mG

2a exhibited a superior reactivity to CD44v6-positive colorectal and gastric cancer cell lines in flow cytometry (

Figure 2) and showed the antitumor activities to CHO/CD44v3–10 (

Figure 3) and colorectal and gastric cancers (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). These findings highlight the therapeutic efficacy of C

44Mab-9-mG

2a and suggest the possibility of clinical application. We already prepared the humanized version of C

44Mab-9 and will evaluate the effectiveness in vivo.

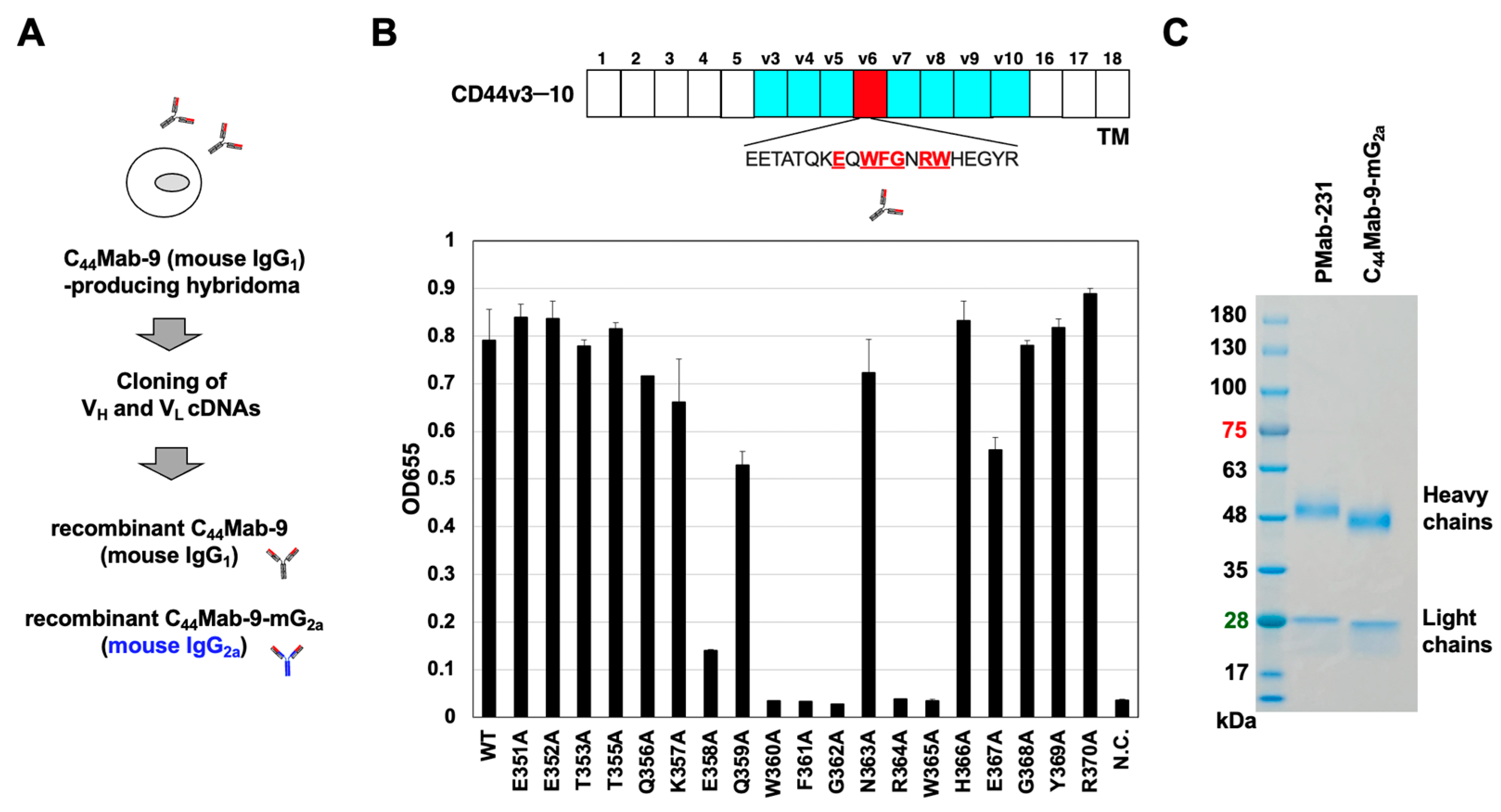

In clinical trials using anti-CD44v6 mAbs, a clone VFF18-derived humanized mAb BIWA-4 was developed into an ADC, bivatuzumab mertansine [

19,

20]. BIWA-8, a modified version of BIWA-4, was developed CD44v6-directed CAR-T [

21,

22], which has been evaluated in AML (clinical trials.gov NCT04097301 [

35]) and solid tumors (clinical trials.gov NCT04427449). As shown in

Figure 1B, the critical amino acids of C

44Mab-9 epitope include E358, W360, F361, G362, R364 and W365, which partly overlap the epitope sequence (360-WFGNRWHEGYR-370) of VFF18 [

15]. Since an alanine-substituted peptide at E358 reduced the reactivity of C

44Mab-9 (

Figure 1B), C

44Mab-9 possesses a different epitope from VFF18. Furthermore, VFF18 was generated by immunization with bacterially expressed CD44v3–10 [

16], whereas C

44Mab-9 was generated by immunization with CHO/CD44v3–10 [

29]. It is essential to compare the biological activity of mAbs derived from C

44Mab-9 and VFF18.

CD44v isoforms were markedly upregulated and associated with poor prognosis in various cancers. Expression of CD44v isoforms is reported to be regulated by the Wnt-β-catenin/TCF4 signaling pathway in colorectal cancer [

36]. A recent study demonstrated a novel tumor-suppressive mechanism of MEN1 through the regulation of the CD44 alternative splicing. Loss of Men1 significantly accelerated the progression of Kras-driven lung adenocarcinoma and enhanced the accumulation of CD44v isoforms [

37]. Mechanistically, MEN1 maintained a relatively slow RNA polymerase II elongation rate by regulating the release of PAF1 from CD44 pre-mRNA, thereby preventing the inclusion of variant exons of CD44 [

37]. Moreover, CD44v6-interfering peptides effectively inhibited the growth and metastasis of established MEN1-deficient tumors through the activation of ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides on cellular membranes [

37]. The CD44v6-interfering peptide was previously reported as KEQWFGNRWHEGYR [

38], which contains the epitope amino acids of C

44Mab-9 (

Figure 1B). Furthermore, the CD44v6-interfering peptide or VFF18 were also reported to block ligand-dependent activation of c-MET and subsequent colorectal cancer cell scattering and migration [

38,

39]. Although we mainly investigated the ADCC and CDC induced by C

44Mab-9-mG

2a (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), it is interesting to examine whether C

44Mab-9 suppresses the ligand-induced cell proliferation and induces ferroptosis in vitro and in vivo.

Because CD44 plays a pivotal role in promoting tumor metastasis and conferring resistance to therapy, multiple therapeutic strategies have been designed to target CD44 against various cancers, including breast, head and neck, ovarian, and gynecological cancers [

40]. Despite these efforts, clinical trials assessing CD44-directed approaches have yielded modest results. For instance, RG7356, a mAb against pan-CD44, showed an acceptable safety profile but failed to elicit a dose-dependent or clinically meaningful response, leading to early termination [

41,

42,

43,

44]. Bivatuzumab mertansine underwent clinical testing; however, its development was discontinued due to the occurrence of severe skin toxicity [

19,

20].

To minimize off-target reactivity and reduce toxicity in normal tissues, cancer-specific monoclonal antibodies (CasMabs) targeting various tumor-associated antigens have been generated. Over three hundred anti–human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) mAb clones have been established through immunization of mice with cancer cell–expressed HER2. Among these, H

2CasMab-2 (also known as H

2Mab-250) was identified as exhibiting cancer cell–specific binding through flow cytometric screening. H

2CasMab-2 selectively recognized HER2 expressed on breast carcinoma cells, while showing negligible reactivity with HER2 on normal epithelial cells, derived from mammary gland, colon, lung bronchus, renal proximal tubule, and colon [

45]. The epitope analyses further elucidated the molecular basis underlying this cancer-specific recognition [

45,

46]. In addition, CAR T-cell therapy employing a single-chain variable fragment of H

2CasMab-2 has been developed and is currently being evaluated in a phase I clinical trial (NCT06241456) for patients with HER2-positive advanced solid tumors [

46]. Although several anti-CD44v6 mAbs clones have been generated, additional clones will be necessary to identify those with cancer-specific reactivity suitable for developing CD44v6-directed CasMabs. We have been generating more clones of anti-CD44v6 mAbs using some strategy and updated our website antibody bank (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm, accessed on Oct.14, 2025). We will screen their reactivity to normal and cancer cells, and the development of anti-CD44v6 CasMabs is expected in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.K. and Y.K.; methodology, M.K.K. and T.O.; validation, H.S. and Y.K.; investigation, A.H., T.T., T.O., K.Shinoda., T.N., A.N., N.K., H.A., K.Suzuki., and H.S.; data curation, A.H. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.; project administration, Y.K.; funding acquisition, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Production of recombinant anti-CD44v6 mAbs, C44Mab-9 and C44Mab-9-mG2a, from C44Mab-9-producing hybridoma. (A) After determination of CDRs of C44Mab-9 (mouse IgG1), recombinant C44Mab-9 and C44Mab-9-mG2a (mouse IgG2a) were produced. (B) ELISA assay using twenty synthesized CD44v6 peptides [CD44v6 p351-370 wild-type (WT) and the alanine-substituted mutants]. Extracellular structure of CD44v3-10, including standard exons (1-5 and 16-18) and variant exons (v3-v10)-encoded regions are presented. The essential amino acids for C44Mab-9 recognition are presented (underlined). N.C.: negative control (PBS). (C) C44Mab-9-mG2a and PMab-231 (control mIgG2a) were treated with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on a polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with Bio-Safe CBB G-250 Stain.

Figure 1.

Production of recombinant anti-CD44v6 mAbs, C44Mab-9 and C44Mab-9-mG2a, from C44Mab-9-producing hybridoma. (A) After determination of CDRs of C44Mab-9 (mouse IgG1), recombinant C44Mab-9 and C44Mab-9-mG2a (mouse IgG2a) were produced. (B) ELISA assay using twenty synthesized CD44v6 peptides [CD44v6 p351-370 wild-type (WT) and the alanine-substituted mutants]. Extracellular structure of CD44v3-10, including standard exons (1-5 and 16-18) and variant exons (v3-v10)-encoded regions are presented. The essential amino acids for C44Mab-9 recognition are presented (underlined). N.C.: negative control (PBS). (C) C44Mab-9-mG2a and PMab-231 (control mIgG2a) were treated with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on a polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with Bio-Safe CBB G-250 Stain.

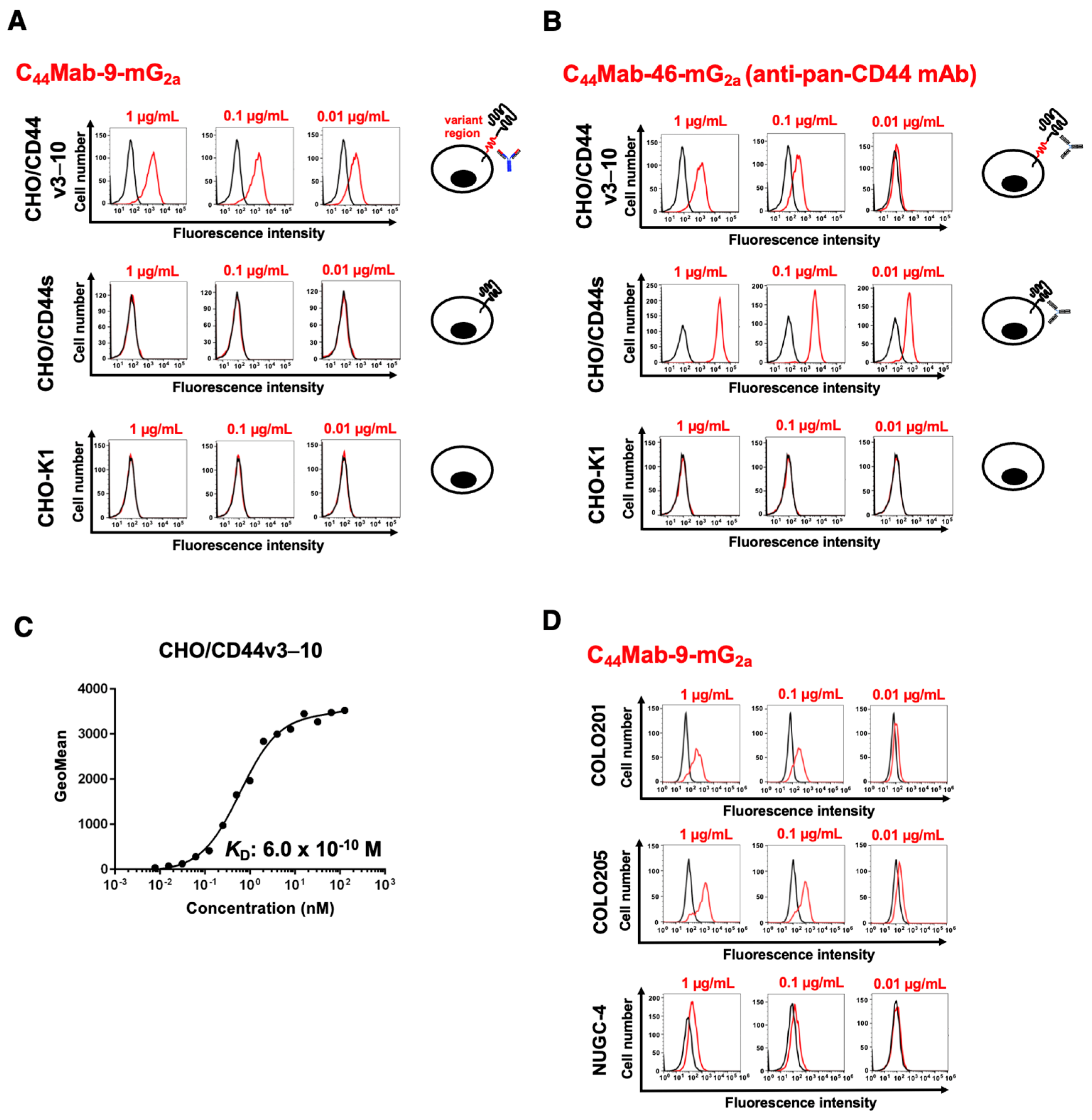

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis using anti-CD44 mAbs. (A,B) CHO/CD44v3–10, CHO/CD44s, and CHO-K1 were treated with 0.01, 0.1, and 1 µg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a (A) and C44Mab-46-mG2a (B). The cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer. (C) CHO/CD44v3–10 were treated with serially diluted C44Mab-9-mG2a, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG treatment. The fluorescence data were analyzed, and the KD values were determined. (D) COLO201, COLO205, and NUGC-4 were treated with 0.01, 0.1, and 1 µg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a. The cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis using anti-CD44 mAbs. (A,B) CHO/CD44v3–10, CHO/CD44s, and CHO-K1 were treated with 0.01, 0.1, and 1 µg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a (A) and C44Mab-46-mG2a (B). The cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer. (C) CHO/CD44v3–10 were treated with serially diluted C44Mab-9-mG2a, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG treatment. The fluorescence data were analyzed, and the KD values were determined. (D) COLO201, COLO205, and NUGC-4 were treated with 0.01, 0.1, and 1 µg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a. The cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

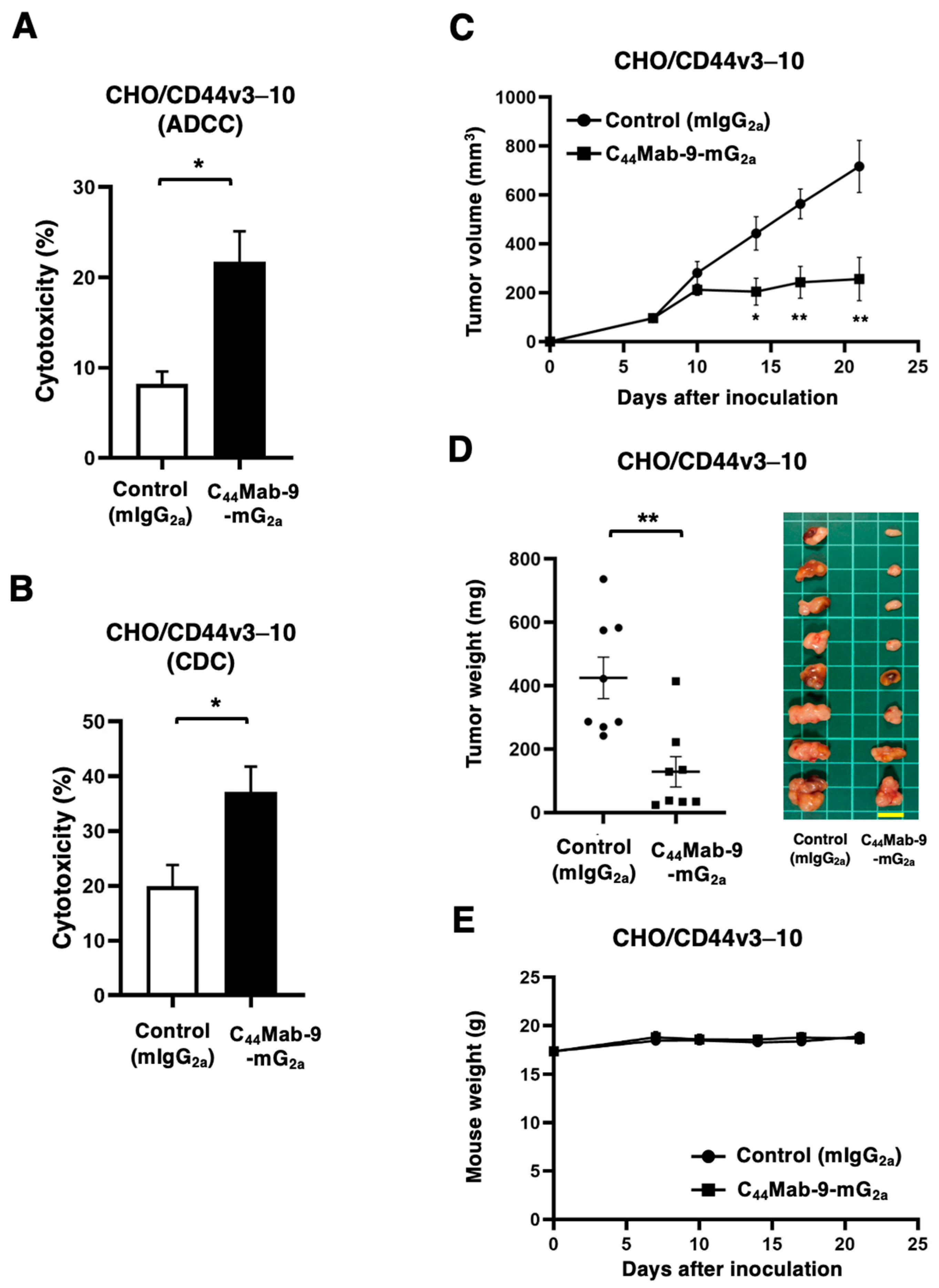

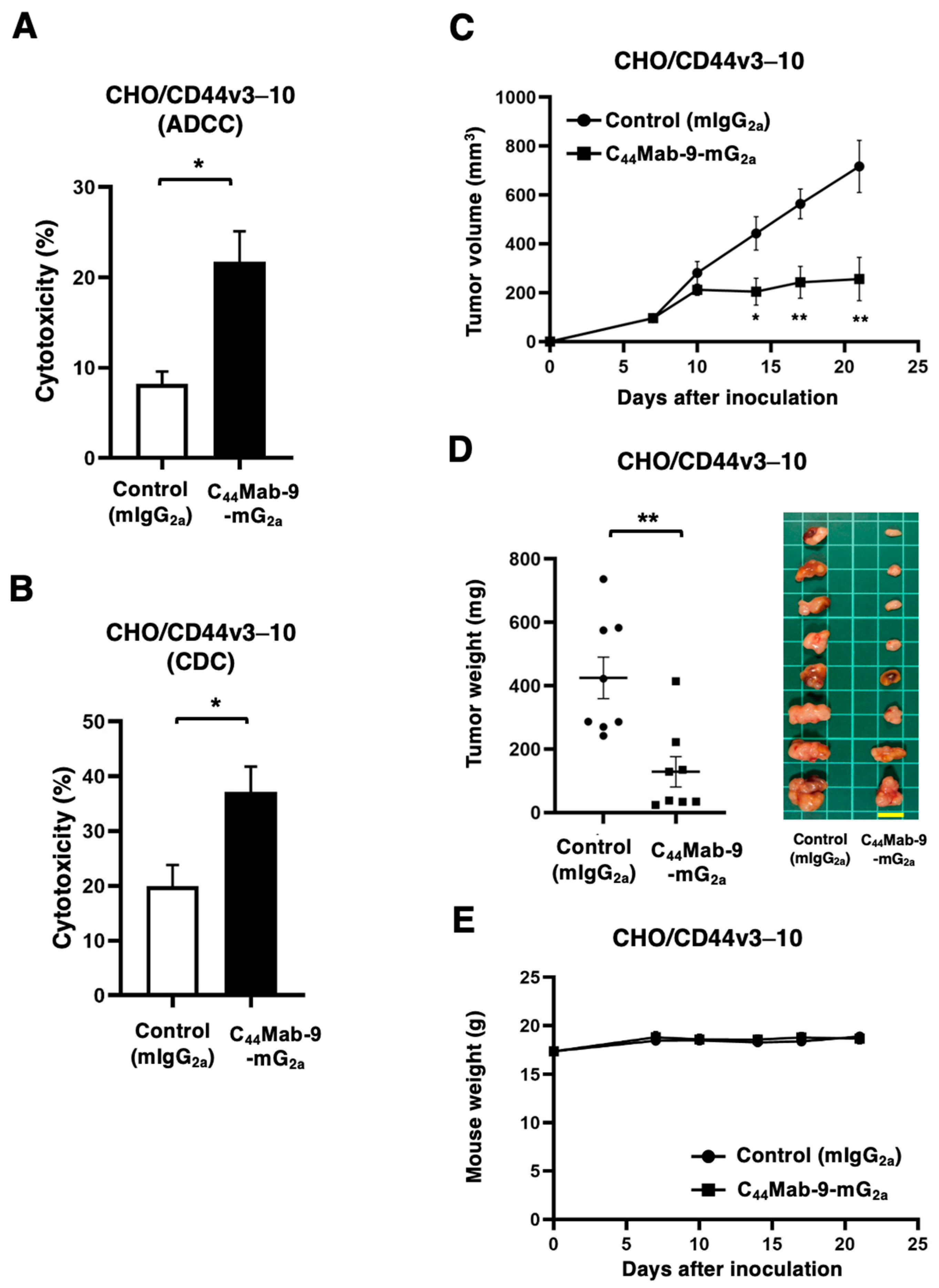

Figure 3.

ADCC, CDC, and antitumor effects against CHO/CD44v3–10 by C44Mab-9-mG2a against CHO/CD44v3–10. (A) Calcein AM-labeled target CHO/CD44v3–10 was incubated with the effector splenocytes in the presence of 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. (B) Calcein AM-labeled target CHO/CD44v3–10 was incubated with complements and 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. Following a 4.5-hour incubation, the Calcein release into the medium was measured. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test). (C-E) Antitumor activity of C44Mab-9-mG2a against CHO/CD44v3–10 xenograft. (C) CHO/CD44v3–10 was subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). An amount of 200 μg of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mouse IgG2a (mIgG2a) was intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on day 14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D) The mice treated with the mAbs were euthanized on day 21. The xenograft weights were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). (E) Body weights of xenograft-bearing mice treated with the mAbs. There is no statistical difference.

Figure 3.

ADCC, CDC, and antitumor effects against CHO/CD44v3–10 by C44Mab-9-mG2a against CHO/CD44v3–10. (A) Calcein AM-labeled target CHO/CD44v3–10 was incubated with the effector splenocytes in the presence of 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. (B) Calcein AM-labeled target CHO/CD44v3–10 was incubated with complements and 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. Following a 4.5-hour incubation, the Calcein release into the medium was measured. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test). (C-E) Antitumor activity of C44Mab-9-mG2a against CHO/CD44v3–10 xenograft. (C) CHO/CD44v3–10 was subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). An amount of 200 μg of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mouse IgG2a (mIgG2a) was intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on day 14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D) The mice treated with the mAbs were euthanized on day 21. The xenograft weights were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). (E) Body weights of xenograft-bearing mice treated with the mAbs. There is no statistical difference.

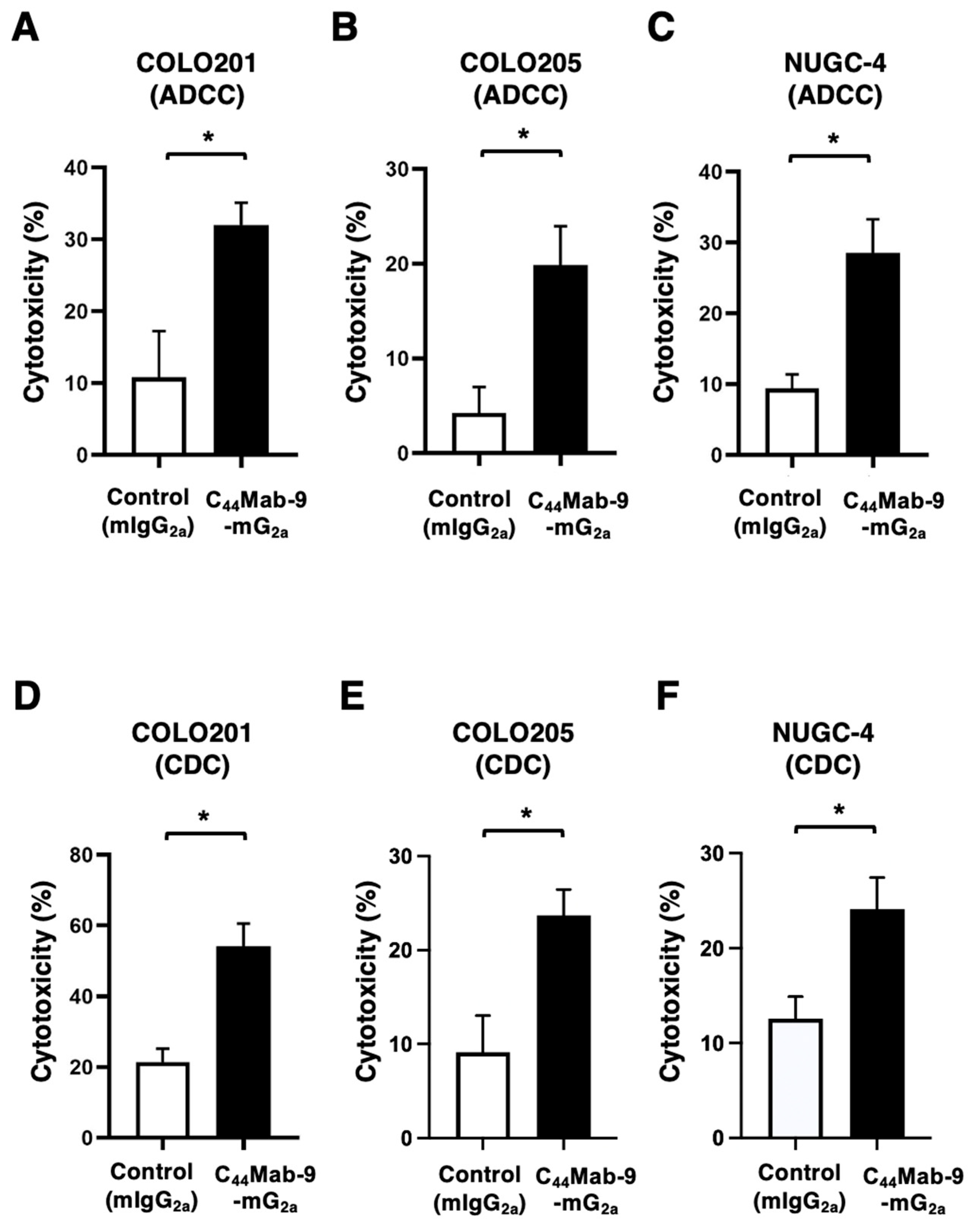

Figure 4.

ADCC and CDC by C44Mab-9-mG2a against COLO201, COLO205, and NUGC-4. (A-C) Calcein AM-labeled targets COLO201 (A), COLO205 (B), and NUGC-4 (C) were incubated with the effector splenocytes in the presence of 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. (D-F) Calcein AM-labeled targets COLO201 (D), COLO205 (E), and NUGC-4 (F) were incubated with complements and 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. Following a 4.5-hour incubation, the Calcein release into the medium was measured. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test).

Figure 4.

ADCC and CDC by C44Mab-9-mG2a against COLO201, COLO205, and NUGC-4. (A-C) Calcein AM-labeled targets COLO201 (A), COLO205 (B), and NUGC-4 (C) were incubated with the effector splenocytes in the presence of 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. (D-F) Calcein AM-labeled targets COLO201 (D), COLO205 (E), and NUGC-4 (F) were incubated with complements and 100 μg/mL of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mIgG2a. Following a 4.5-hour incubation, the Calcein release into the medium was measured. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test).

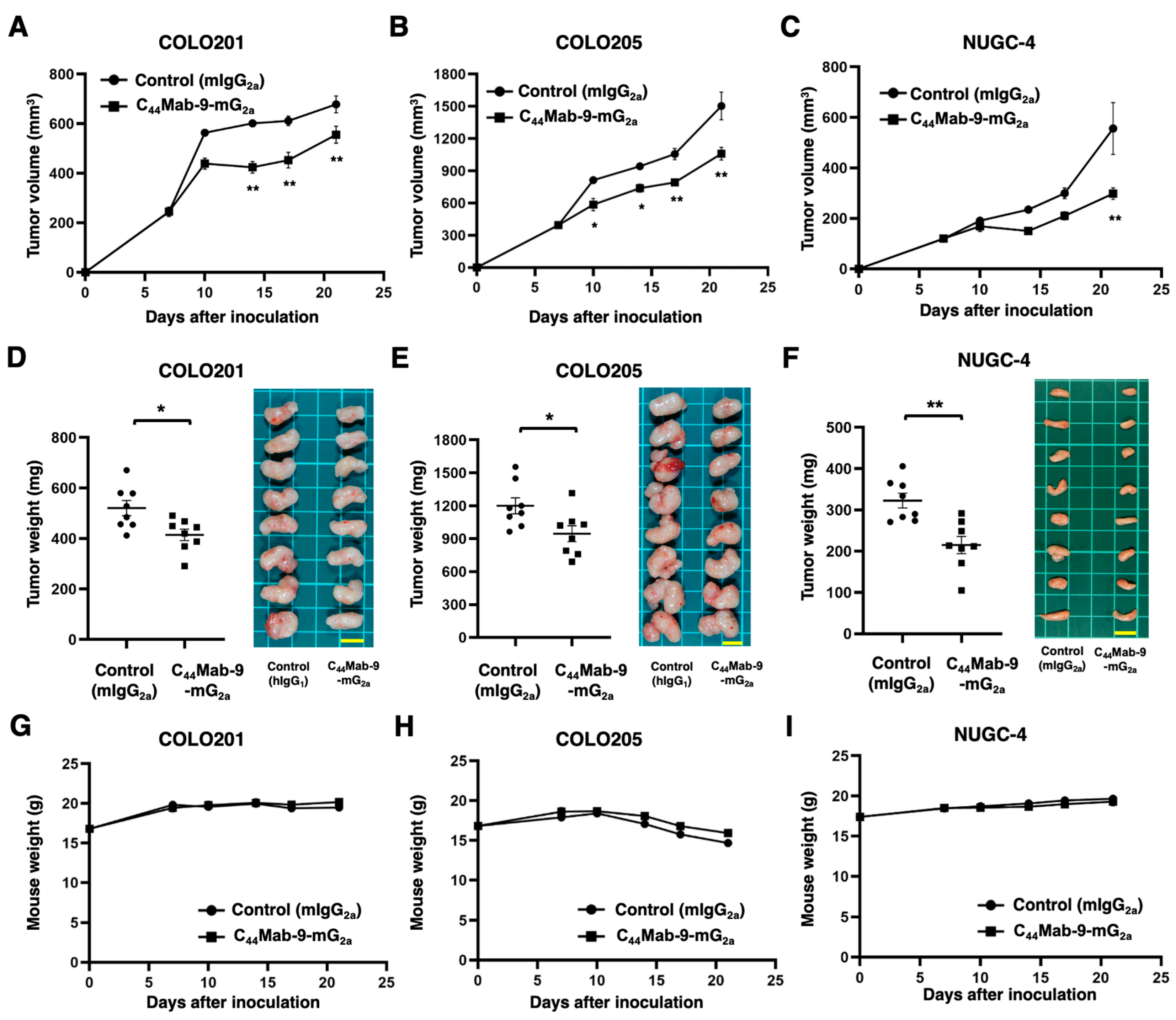

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of C44Mab-9-mG2a against COLO201, COLO205, and NUGC-4 xenograft. (A-C) COLO201 (A), COLO205 (B), and NUGC-4 (C) were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). Amounts of 100 μg (in COLO201 and COLO205) or 200 μg (in NUGC-4) of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mouse IgG2a (mIgG2a) were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on day 14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D-F) The mice treated with the mAbs were euthanized on day 21. The xenograft weights were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). (G-I) Body weights of xenograft-bearing mice treated with the mAbs. There is no statistical difference.

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of C44Mab-9-mG2a against COLO201, COLO205, and NUGC-4 xenograft. (A-C) COLO201 (A), COLO205 (B), and NUGC-4 (C) were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). Amounts of 100 μg (in COLO201 and COLO205) or 200 μg (in NUGC-4) of C44Mab-9-mG2a or control mouse IgG2a (mIgG2a) were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on day 14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D-F) The mice treated with the mAbs were euthanized on day 21. The xenograft weights were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). (G-I) Body weights of xenograft-bearing mice treated with the mAbs. There is no statistical difference.