Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Model Strategic Decisions: Capture the objectives and constraints of both attackers and defenders [12].

- Conduct Risk Analysis: Elucidate payoffs and tactics to identify critical vulnerabilities and optimal defensive strategies [13].

- Enable Adaptive Defense: Capture the dynamic nature of cyber threats, including those augmented by AI, to inform adaptive countermeasures [14].

- Optimize Resource Allocation: Evaluate strategy effectiveness to guide efficient investment of limited defensive resources [15].

- A novel game-theoretic model for DFR that quantifies strategic attacker-defender interactions.

- The integration of MITRE ATT&CK and D3FEND with AHP-weighted metrics to ground utilities in real-world tactics and techniques.

- An equilibrium analysis that yields actionable resource allocation guidance for SMBs/SMEs.

- An evaluation demonstrating the framework’s efficacy in reducing attacker success rates, even in complex, multi-vector APT scenarios influenced by modern AI-powered tools.

2. Related Works

2.1. Game Theory in Digital Forensics

2.2. Digital Forensics Readiness and Techniques

2.3. Advancement in Cybersecurity Modeling

2.4. Innovative Tools and Methodologies

2.5. Digital Forensics in Emerging Domains

2.6. Advanced Persistent Threats and Cybercrime

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Problem Statement

- : Strategies available to attackers, corresponding to MITRE ATT&CK tactics (e.g., Reconnaissance, Resource Development, Initial Access, Execution, Persistence, etc.).

- : Strategies available to defenders, corresponding to MITRE D3FEND countermeasures (e.g., Model, Detect, Harden, Isolate, Deceive, etc.)

- P: Parameters influencing game models, such as attack severity, defense effectiveness, and forensic capability.

- : Utility function for attackers, representing the payoff based on their strategy and the defenders’ strategy .

- : Utility function for defenders, representing the payoff based on their strategy and the attackers’ strategy .

- Model Construction: Construct game models to represent the interactions between A and D.

- Equilibrium Analysis: Identify Nash equilibria such that:

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Research Design

- Theoretical Framework: The study employs game theory to analyze strategic interactions between attackers and defenders in the context of DFR.

- Model Representation: Game theory models are used to represent the decision-making process of both attackers and defenders, considering their incentives, strategies, and potential outcomes.

3.2.2. Materials

- Game Theory: The research uses game theory literature to build theoretical foundations and employ advanced modeling techniques for analyzing the strategic interactions between attackers and defenders.

- DFR Frameworks: The study uses established DFR frameworks to understand the requirements and strategies involved so our models reflect real world forensic readiness scenarios.

- Computational Tools and Software: Advanced computational tools and software are used to simulate game scenarios and analyze the strategic behavior of both attackers and defenders. These tools allow us to model complex interactions and generate insights from the simulations.

3.2.3. Procedure

- Development of Game Models: Construct game models to represent the interactions between attackers and defenders in DFR scenarios.

- Identification of Strategies: Define strategies available to attackers and defenders, such as investing in security measures, launching attacks, or conducting forensic investigations.

- Parameterization: Assign values to parameters within the game models, representing factors like attack severity, defense effectiveness, and forensic capability.

- Simulation and Analysis: Simulate scenarios using game-theoretic algorithms to evaluate model performance and outcomes.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of varying parameters on strategic outcomes and forensic readiness scores.

3.2.4. Data Analysis

- Quantification of Strategic Behaviors: Quantify the strategic behaviors of attackers and defenders based on game-theoretic metrics such as equilibrium outcomes, payoffs, and dominance strategies.

- Interpretation: Interpret the results of the analysis to identify optimal strategies for improving DFR, including investment priorities, resource allocation, and policy adjustments.

3.2.5. Validation

- Validation of Model Assumptions: Validate game models against real-world scenarios and empirical data where possible, ensuring that the theoretical framework accurately captures the dynamics of DFR.

- Sensitivity Testing: Perform sensitivity testing to assess the robustness of the findings against variations in the assumptions and parameters of the model.

3.2.6. Reporting

- Documentation: Document the methodology, assumptions, and results of the study in a comprehensive research report or academic paper.

- Discussion: Discuss the implications of the findings for improving DFR, addressing limitations, and suggesting avenues for future research.

3.3. Game Theory Background

3.3.1. Players and Actions

3.3.2. Payoff Functions and Utility

3.3.3. Scenario Analysis

3.3.4. Formalizing the Game

- Players: Defender (D), Attacker (A)

-

Actions:

- -

- Defender: (Set of defender’s investment choices)

- -

- Attacker: (Set of attacker’s attack choices)

-

Payoff Functions:

- -

- Defender’s Payoff Function: (Maps a combination of defender’s investment (D) and attacker’s attack (A) to a real number representing the defender’s utility)

- -

- Attacker’s Payoff Function: (Maps a combination of defender’s investment (D) and attacker’s attack (A) to a real number representing the attacker’s utility)

| Attack (SA) | Attack (SI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Defender (HI FT) | ||

| Defender (LI FT) |

3.3.5. Payoff Analysis

-

Defender’s Payoffs:

- -

- HI FT: High investment in forensic tools leads to high readiness for a sophisticated attack (SA), resulting in low losses (high utility) for the defender. However, if the attacker chooses a simpler attack (SI), the high investment might be unnecessary, leading to very low losses (moderate utility) but potentially wasted resources.

- -

- LI FT: Low investment translates to lower readiness, making the defender more vulnerable to a sophisticated attack (SA), resulting in high losses (low utility). While sufficient for a simpler attack (SI), it might not provide a complete picture for forensic analysis, leading to moderate losses (moderate utility).

-

Attacker’s Payoffs:

- -

- SA: A sophisticated attack offers the potential for higher gains (data exfiltration) but requires more effort and resources to bypass advanced forensic tools (HI FT) implemented by the defender. If the defender has low investment (LI FT), the attack is easier to conduct, resulting in higher gains (higher utility).

- -

- SI: This requires less effort but might yield lower gains (lower utility). If the defender has high investment (HI FT), the attacker might face challenges in extracting data, resulting in very low gains (low utility).

3.3.6. Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) and Equilibrium Concepts

3.4. Proposed Approach

-

Players:

- -

- Attacker: 14 strategies ()

- -

- Defender: 6 strategies ()

- Rationality: Both players are presumed rational, seeking to maximize their individual payoffs given knowledge of the opponent’s strategy. The game is simultaneous and non-zero-sum.

3.4.1. PNE Analysis

3.4.2. MNE Analysis

| Algorithm 1:Attacker–Defender Payoff Matrix Calculation |

|

3.4.3. Payoff Matrix Calculation Algorithm

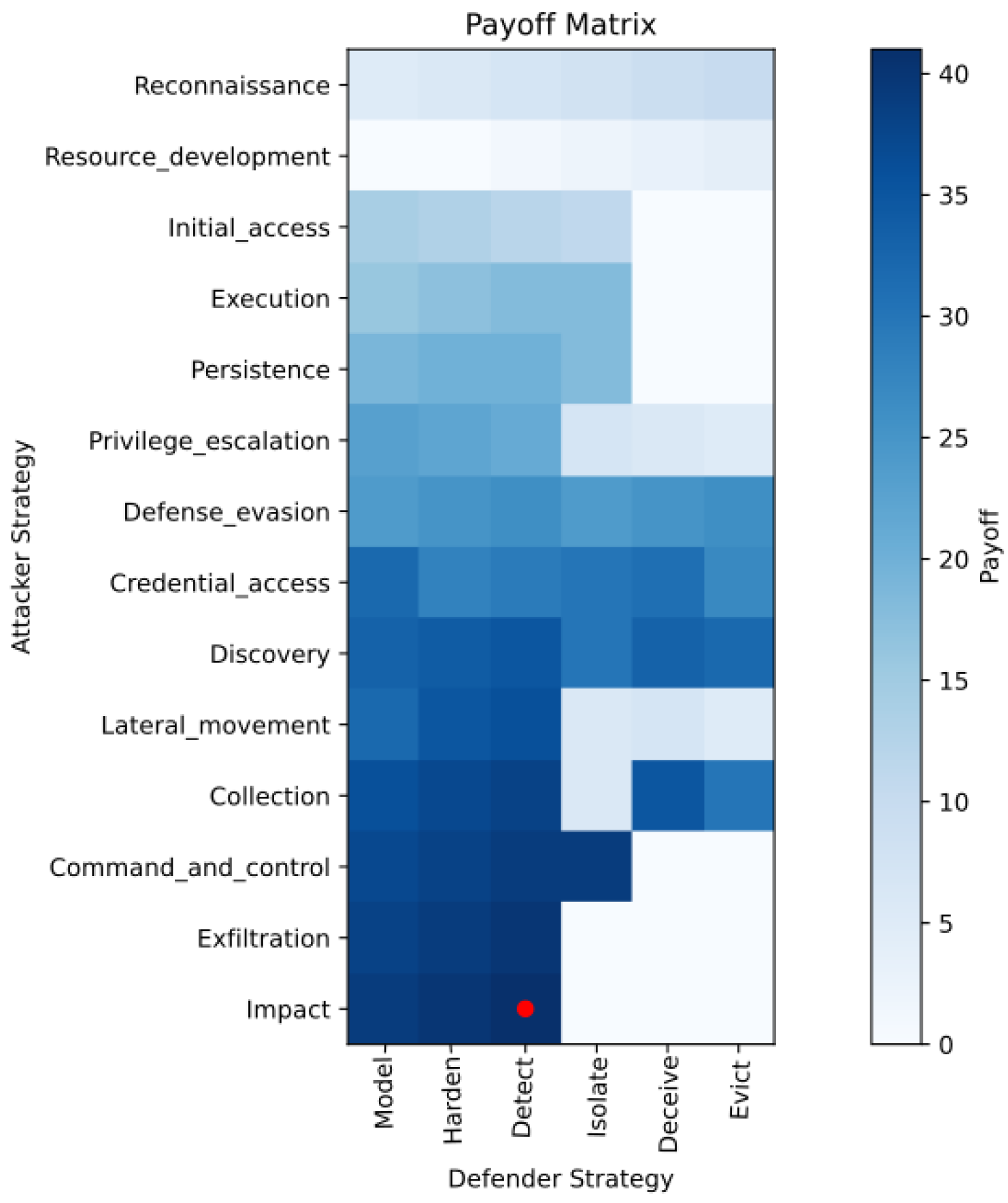

3.4.4. Payoff Matrices

3.4.5. Mixed Nash Equilibrium Computation

MNE Analysis Results

- First MNE: The attacker prefers ’Command_and_Control’ (57%), while the defender favors ’Model’ (95%) with some likelihood for ’Detect’.

- Deterministic Scenarios: Certain equilibria show exclusive preference (e.g., attacker fully on ’Exfiltration’, defender on ’Model’ or ’Detect’).

- Variable Strategies: Some MNEs distribute probabilities across two or more strategies, reflecting tactical unpredictability.

3.4.6. Convergence Analysis

3.5. Utility Function

3.5.1. Attacker Utility Function

3.5.2. Defender Utility Function

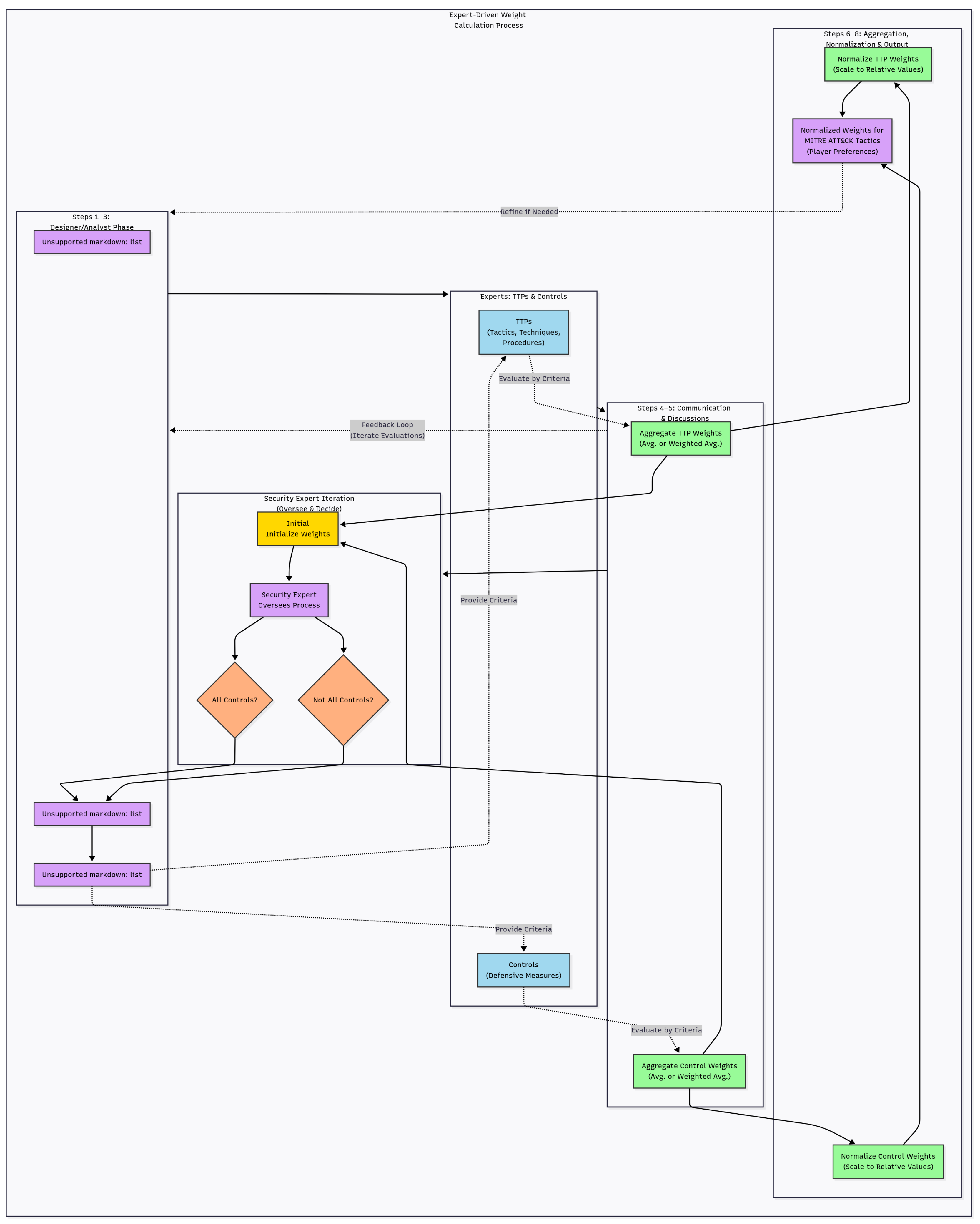

3.5.3. Expert-Driven Weight Calculation

- 1.

- Identify relevant security experts with domain-specific ATT&CK knowledge.

- 2.

- Analyze the threat landscape and associated TTPs.

- 3.

- Establish weighting criteria such as Likelihood, Impact, Detectability, and Effort.

- 4.

- Present tactics and criteria simultaneously to experts for independent evaluation.

- 5.

- Aggregate weights (average or weighted average depending on expertise level).

- 6.

- Normalize aggregated weights to ensure comparability.

- 7.

- Output a set of normalized tactic weights representing collective expert judgment.

3.5.4. Utility Calculation Algorithms

| Algorithm 2:Computing the Utility Function |

|

| Algorithm 3:Analyzing Utility Outcomes |

|

| Algorithm 4:Identify Areas of Improvement |

|

3.6. Identify Areas of Improvement

3.7. Prioritizing DFR Improvements

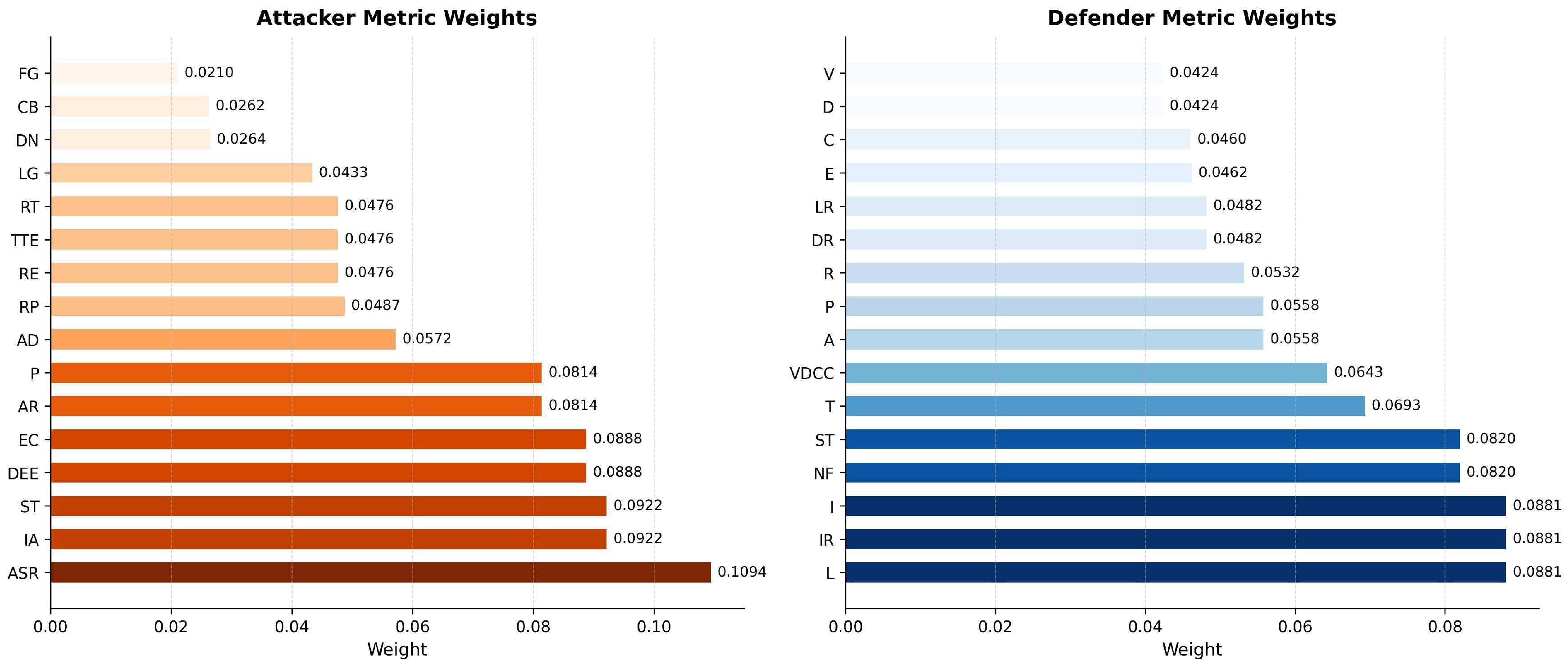

3.7.1. AHP Methodology for Weight Determination

- 1.

- Expert Pairwise Judgments: Ten domain experts completed two pairwise comparison matrices (PCMs), one each for attacker and defender metrics. Entries were scored on the Saaty scale (1/9–9), with reciprocity enforced via . Element-wise geometric means across all expert inputs were computed:

- 2.

- Eigenvector-Based Weight Derivation: For each consensus matrix , we solved and normalized w such that . These normalized weights are visualized in Figure 5.

- 3.

- Weight Consolidation: Consensus weights were tabulated in Table 6 to integrate directly into the utility functions.

- 4.

-

Consistency Validation: We calculated the Consistency Index (CI) and Consistency Ratio (CR) using with and [50]. Both attacker and defender PCMs achieved :

- Attacker PCM: , ,

- Defender PCM: , ,

Reporting Precision and Repeated Weights

Plausibility of Small and Similar CR Values

Additional AHP Diagnostics and Robustness

3.7.2. Prioritization Process

- 1.

- Identify metrics with high weight but low scores.

- 2.

- Assess potential readiness gains from targeted improvement.

- 3.

- Develop tailored enhancement strategies considering cost, time, and resource constraints.

- 4.

- Implement, monitor, and iteratively refine improvements.

3.7.3. DFR Improvement Algorithm

| Algorithm 5: DFR Improvement Plan |

|

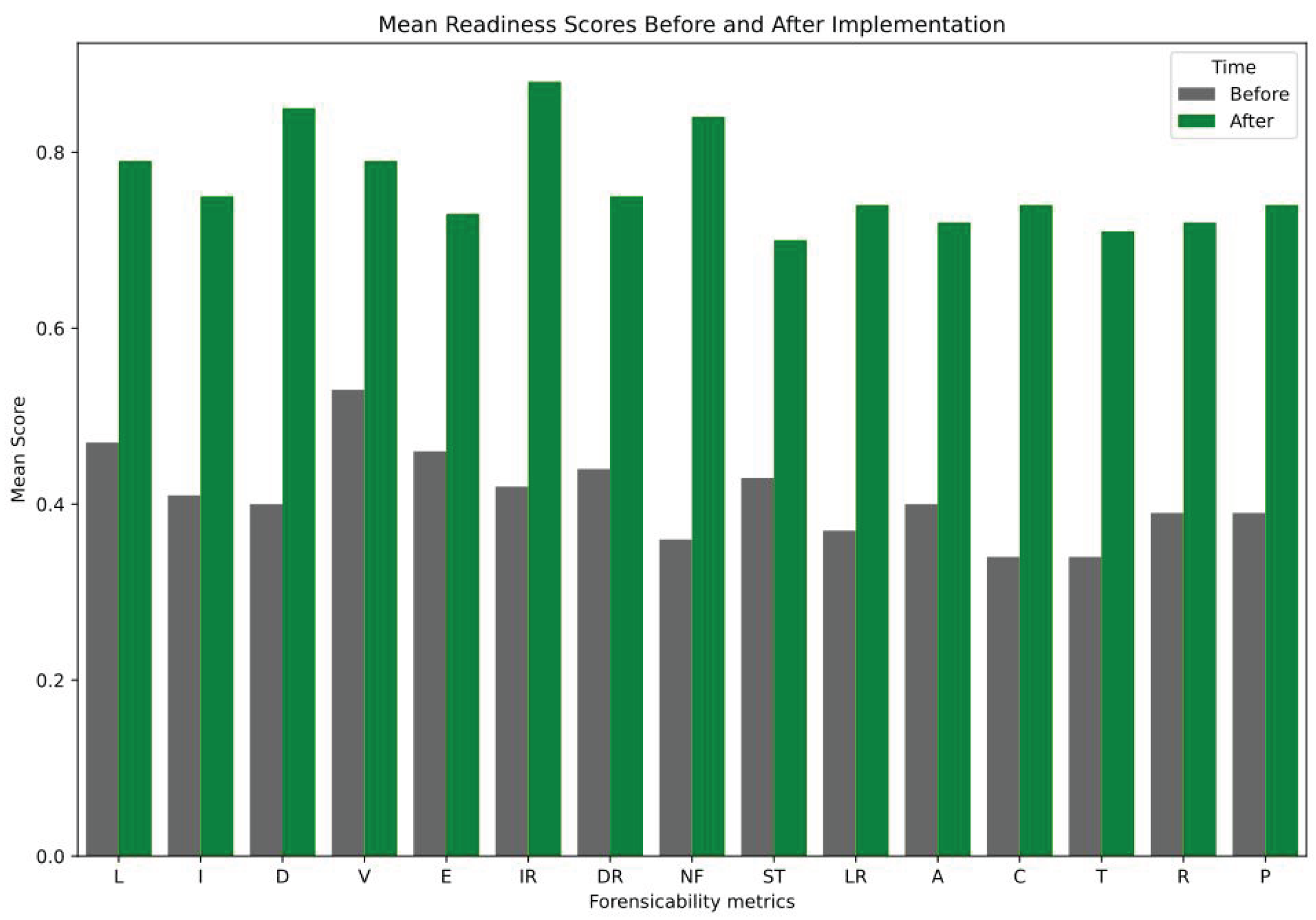

3.8. Reevaluating the DFR

4. Results

4.1. Data Collection and Methodology

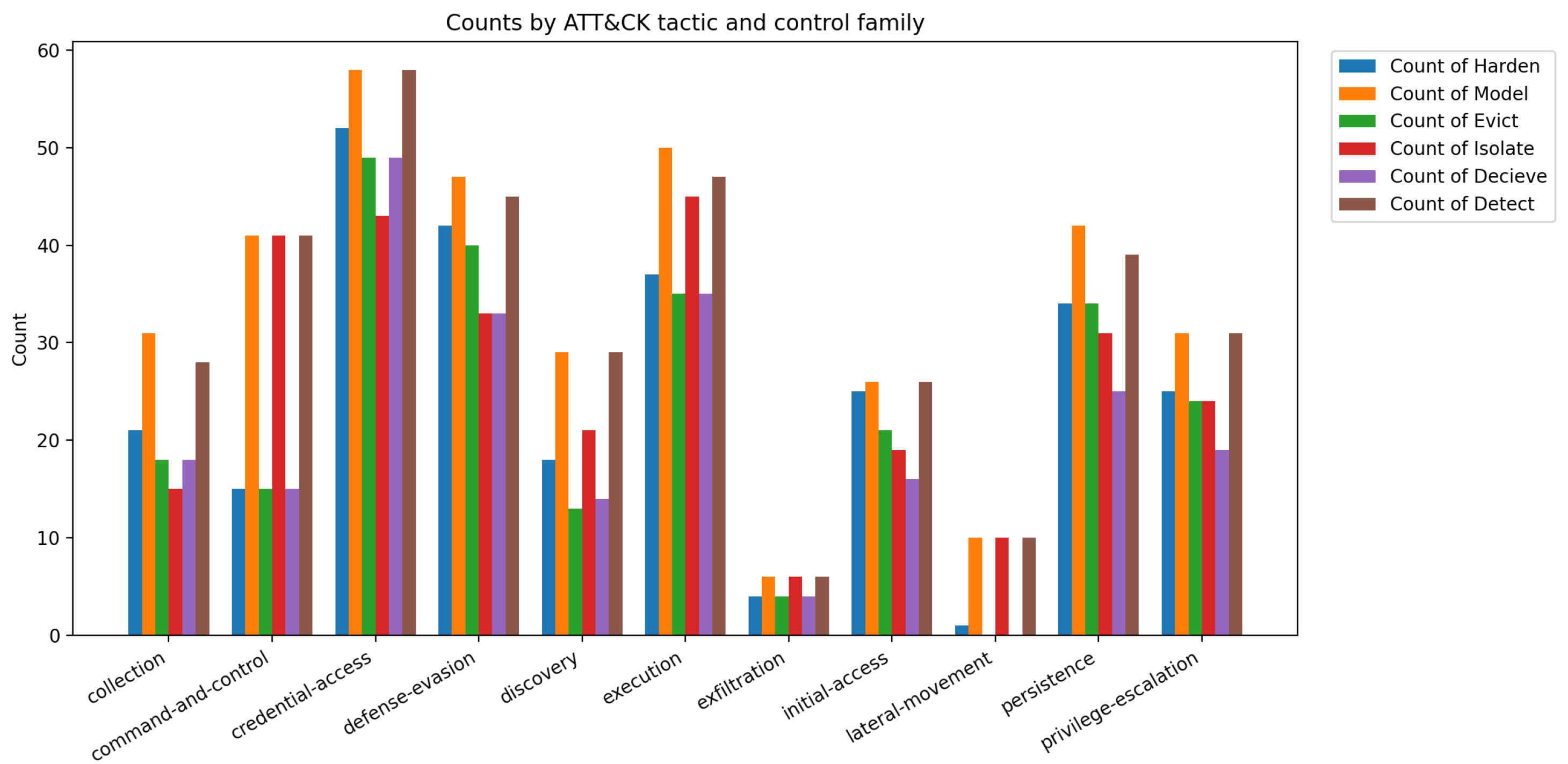

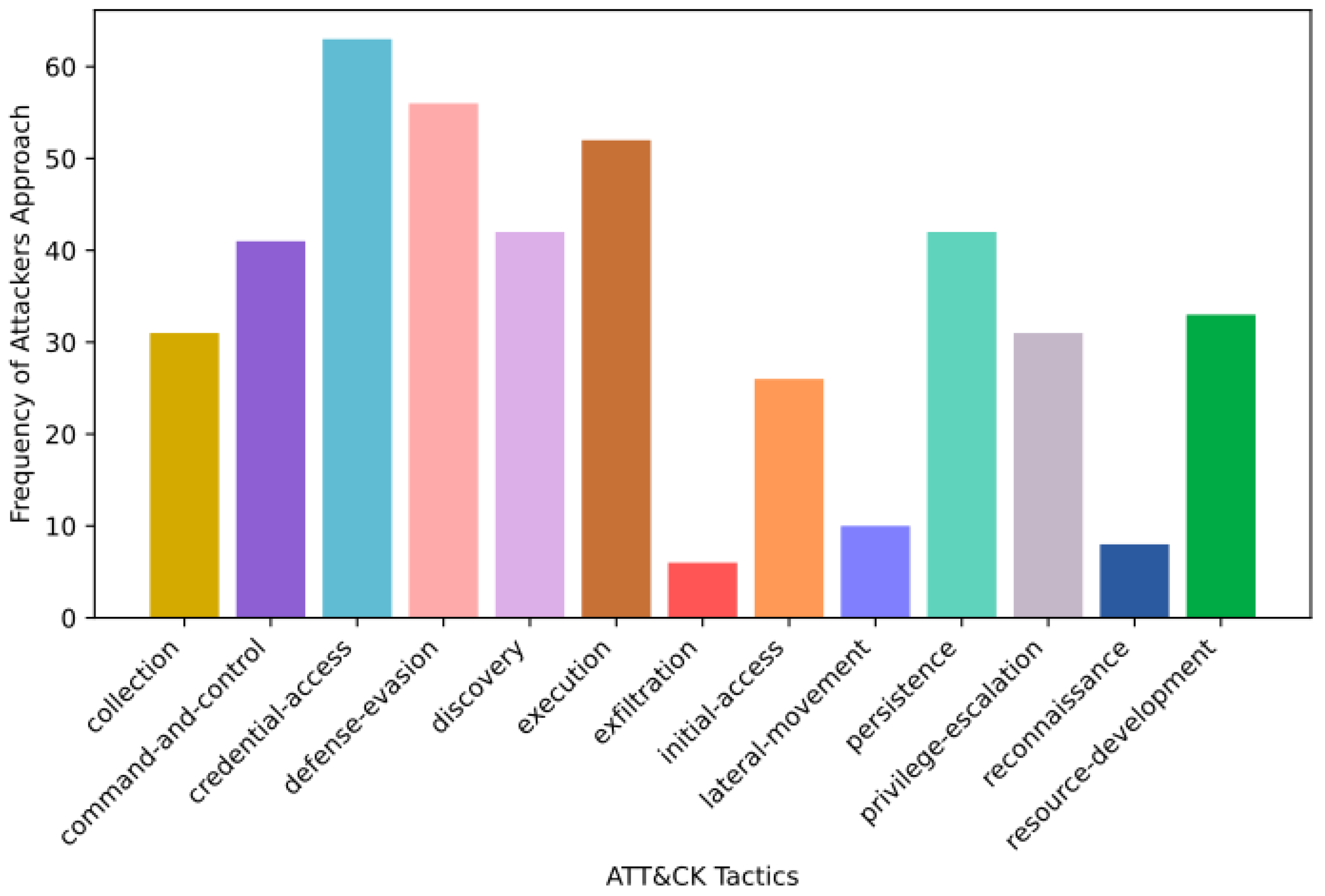

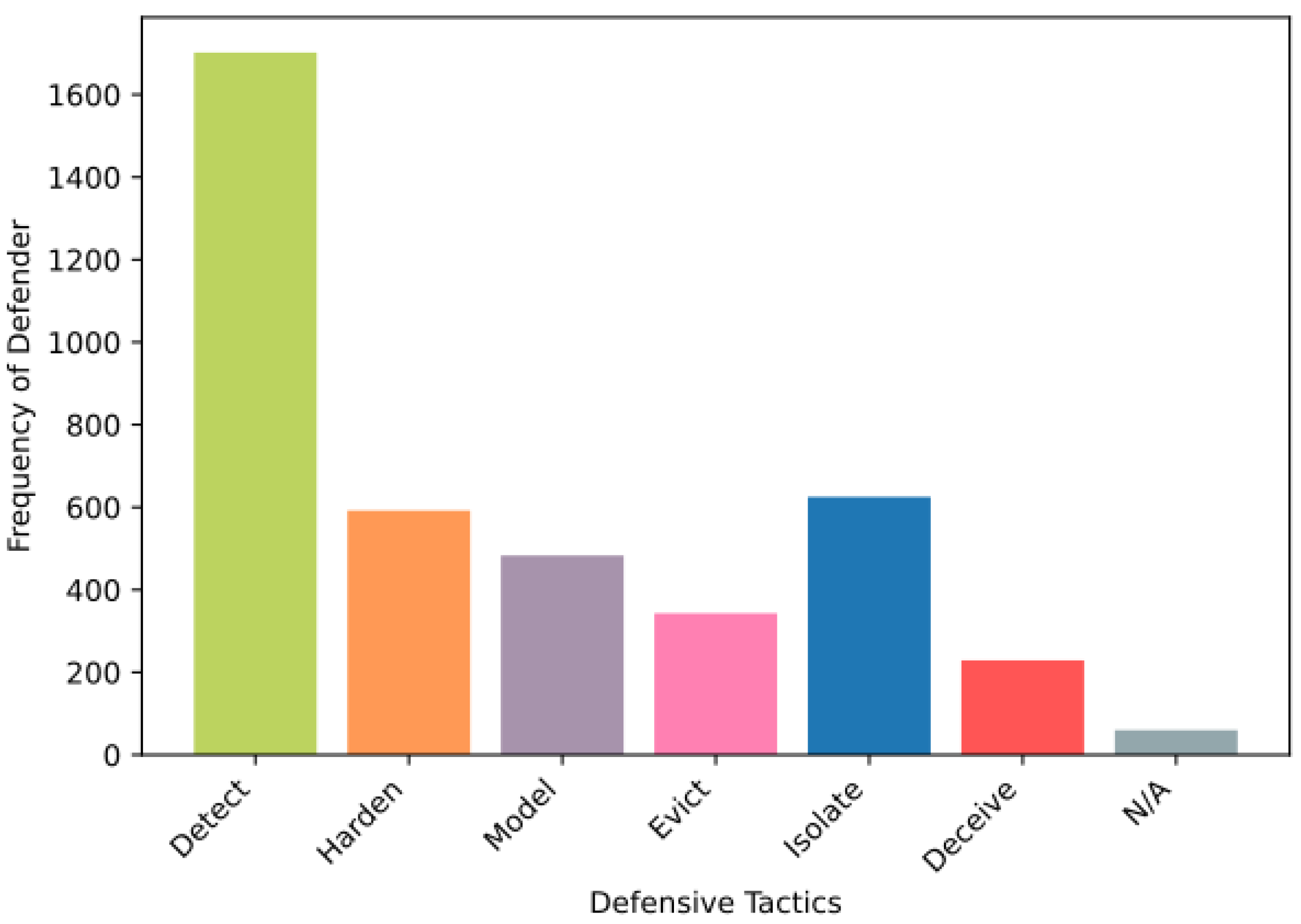

4.2. Analysis of Tactics and Techniques

4.3. DFR Metrics Overview and Impact Quantification

4.4. Attackers vs. Defenders: A Comparative Study

4.5. Game Dynamics and Strategy Analysis

4.6. Real-World Case Assessment

4.7. Sensitivity Analysis

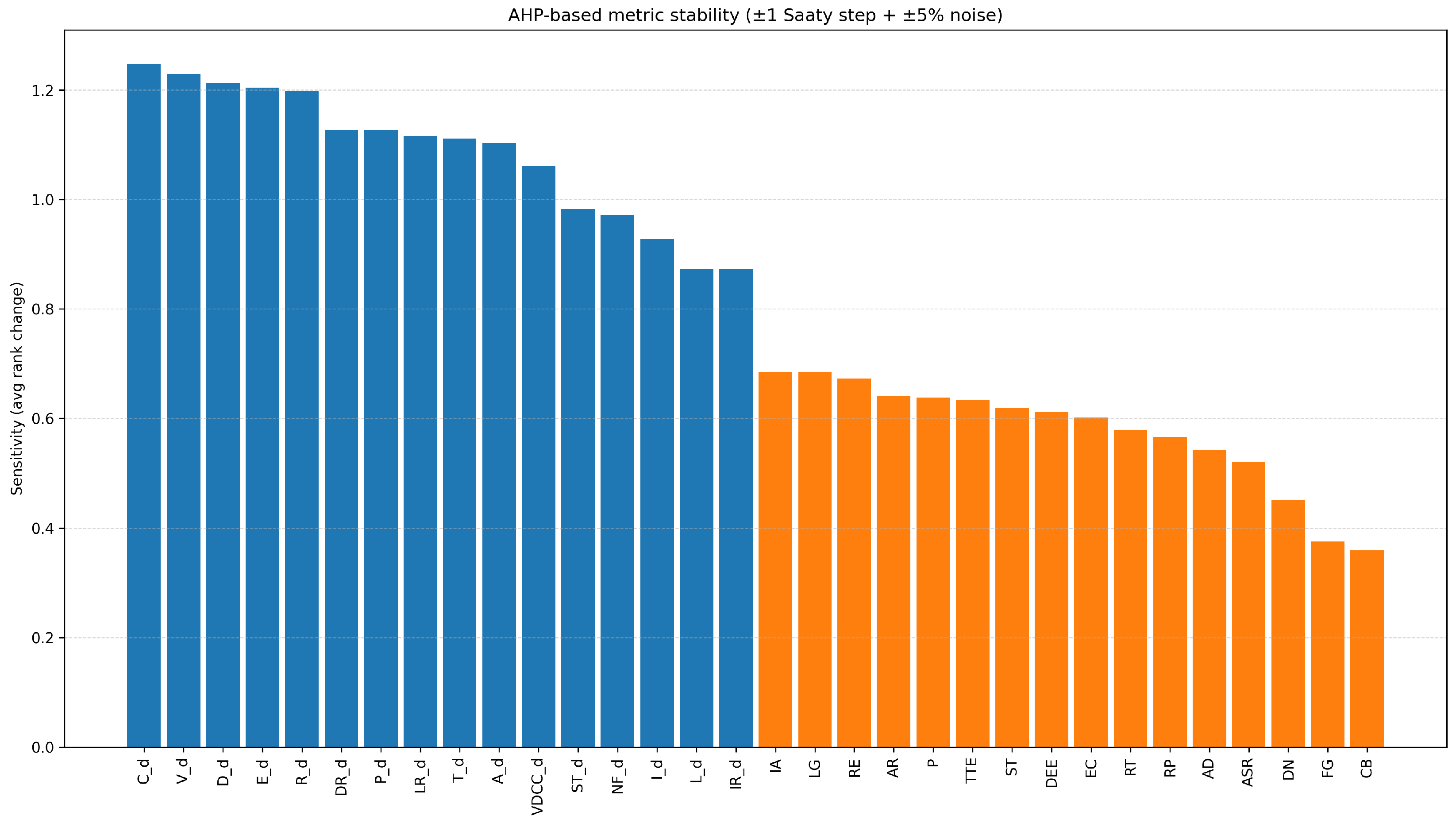

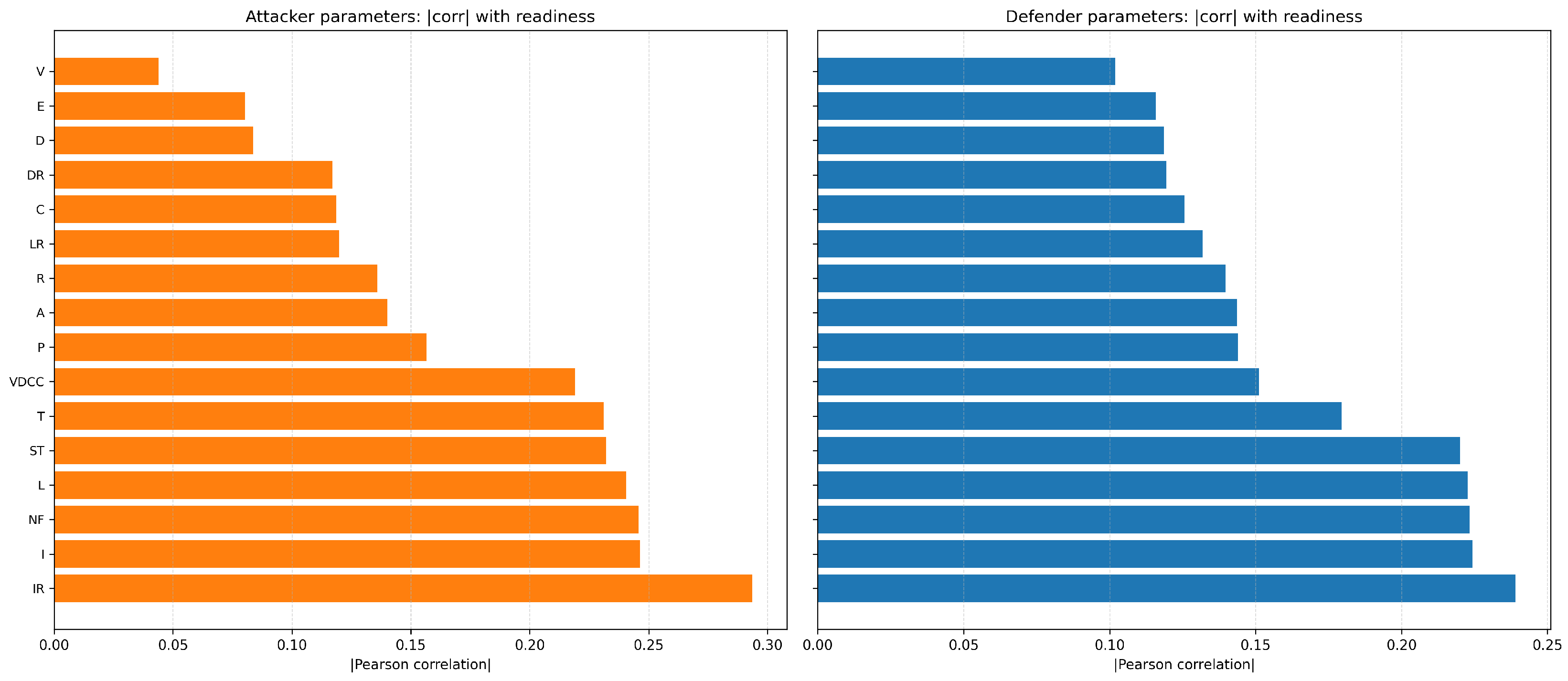

4.7.1. Local Perturbation Sensitivity

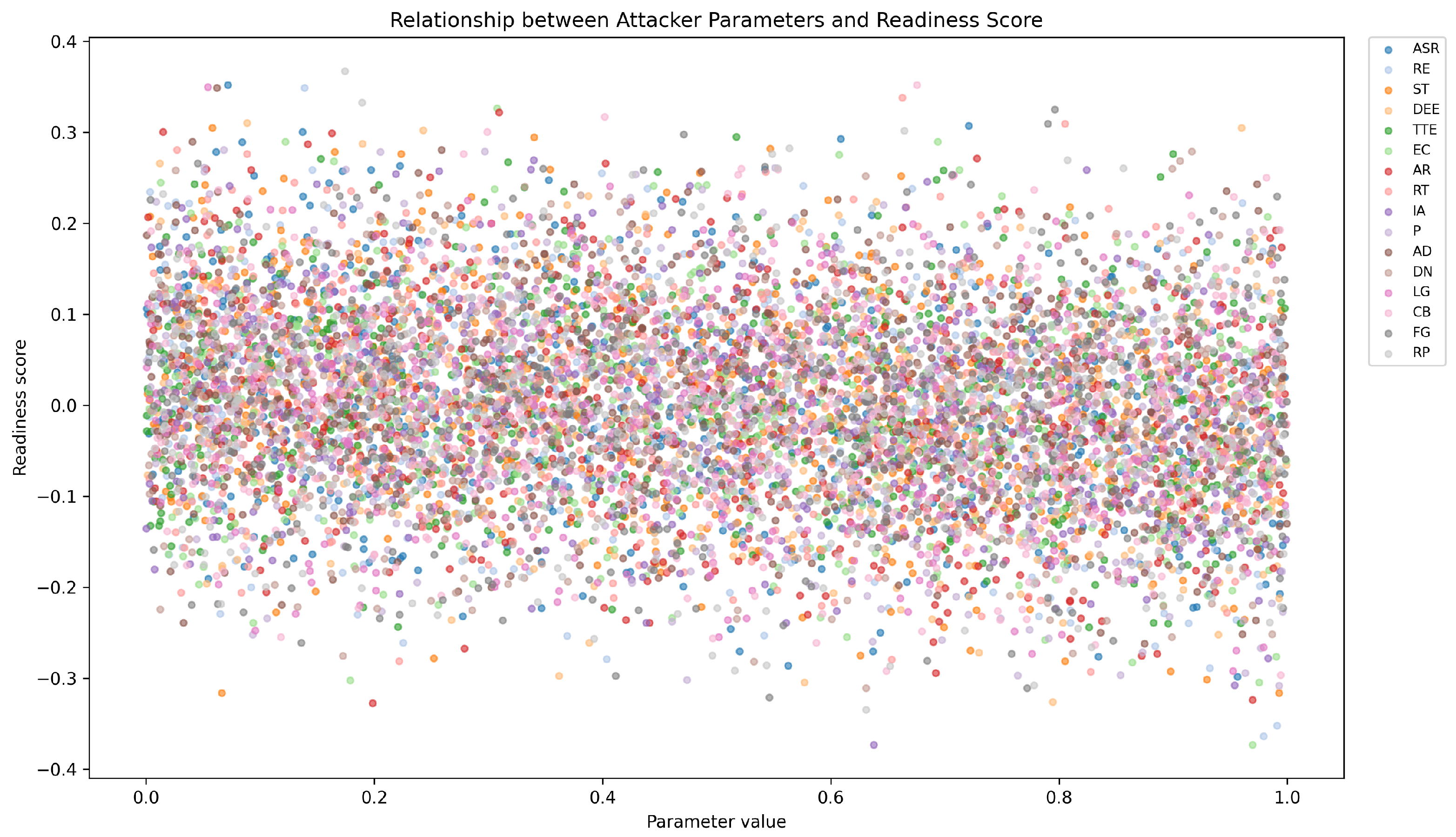

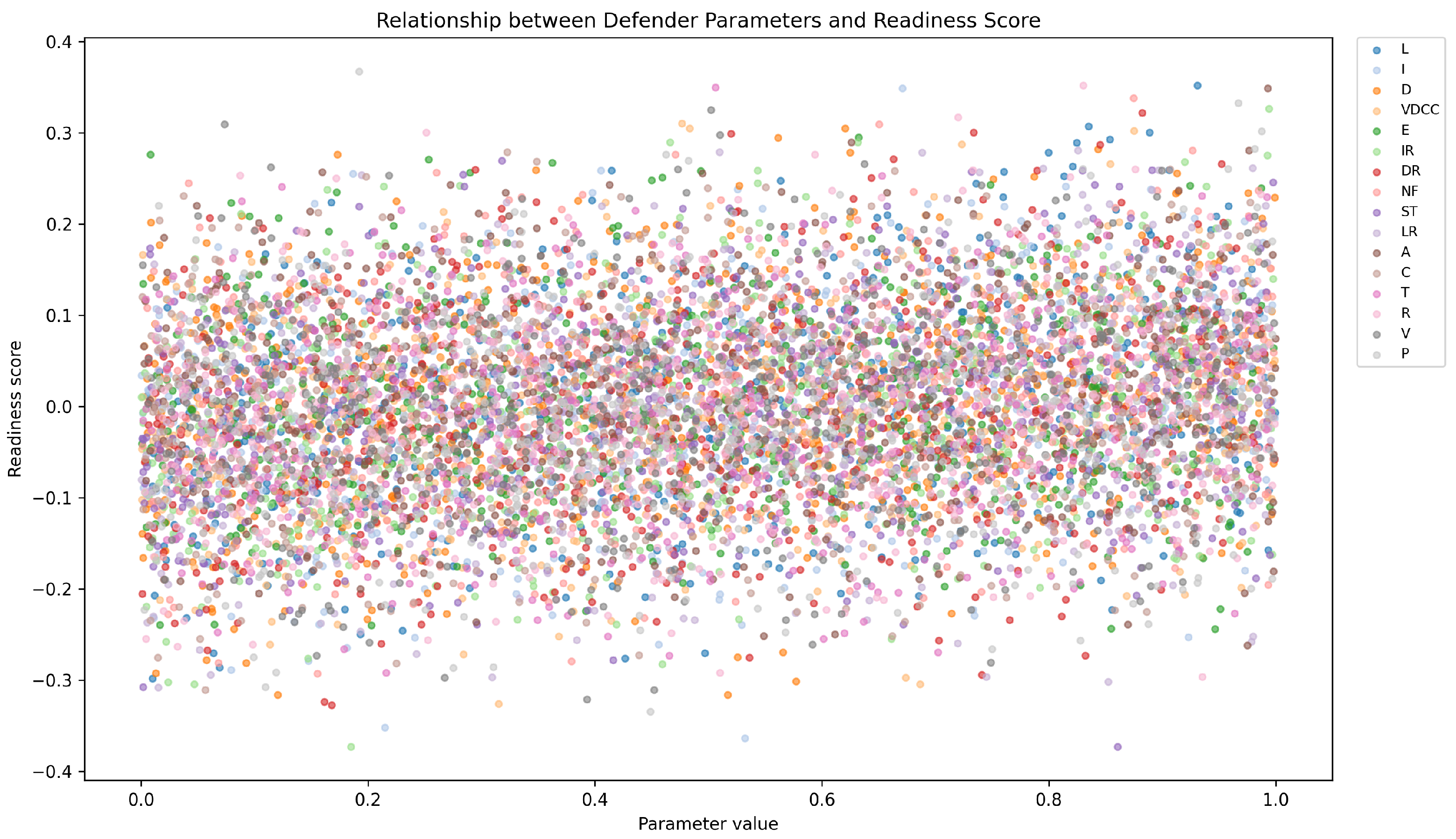

4.7.2. Monte Carlo Simulation

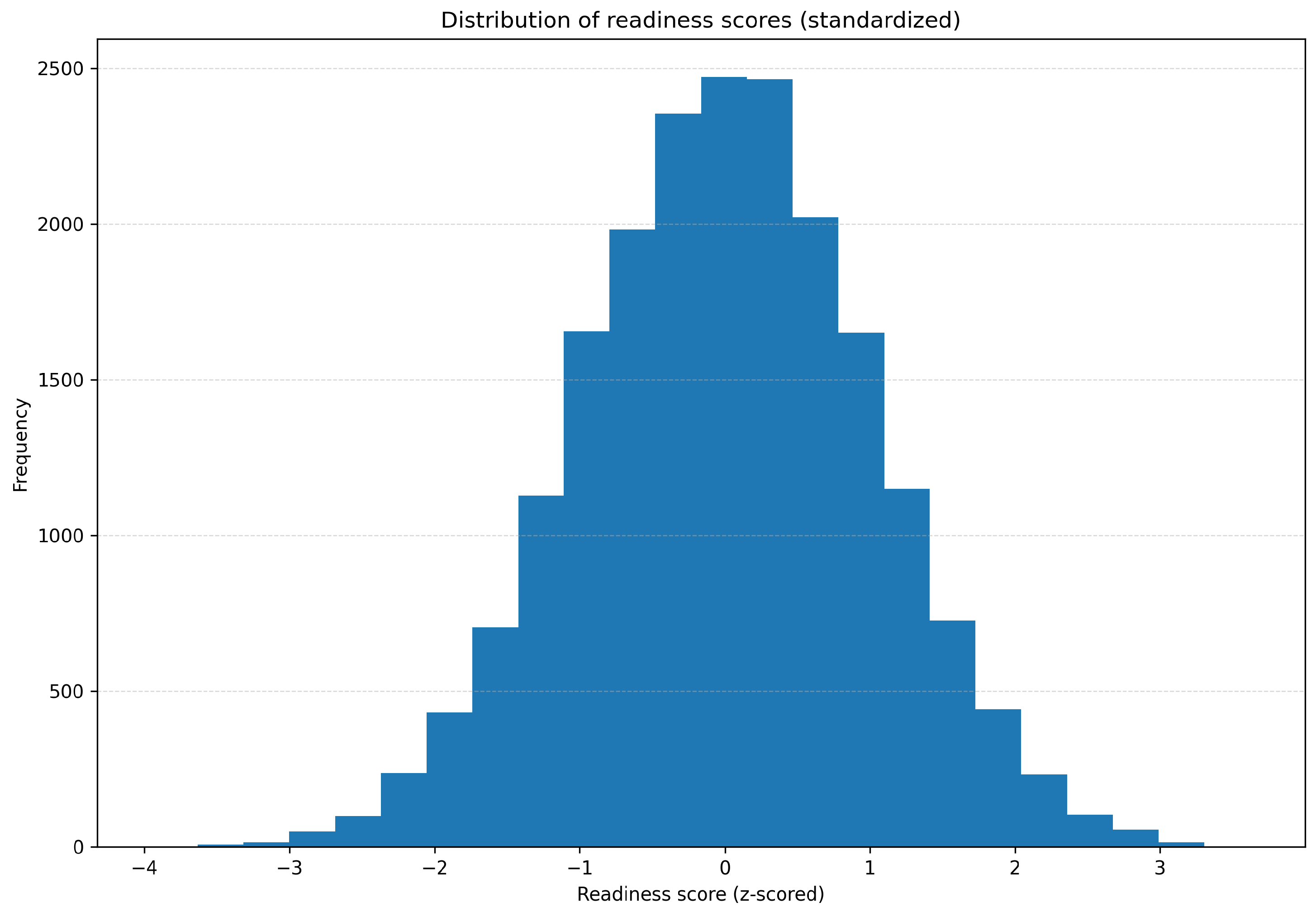

4.8. Distribution of Readiness Score

- Central Peak at 0.0: A high frequency around 0.0 indicates balanced readiness in most systems.

- Symmetrical Spread: Even tapering on both sides suggests system stability across environments.

- Low-Frequency Extremes: Outliers at the tails (−0.3 and +0.3) denote rare but critical deviations requiring targeted intervention.

5. Discussion

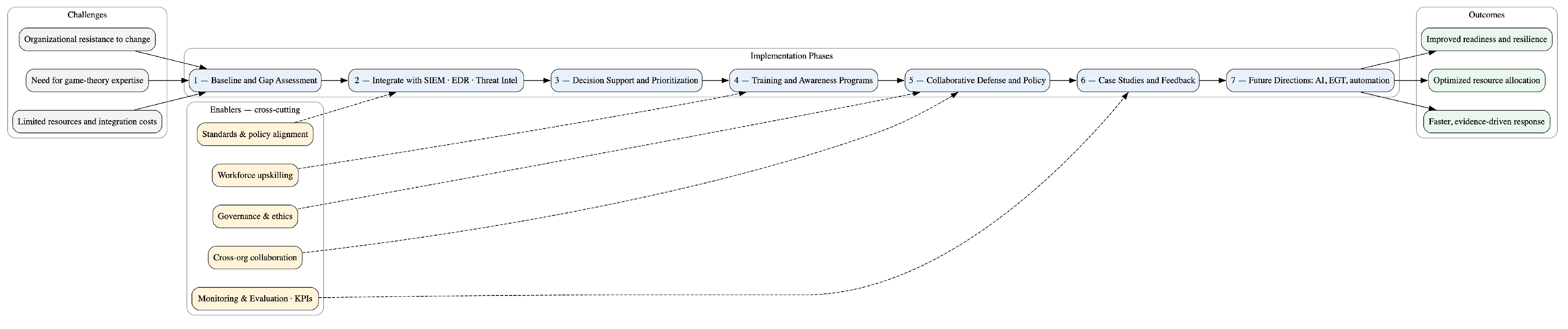

- 1.

- Implementation Challenges: Real-world adoption may encounter barriers such as limited resources, integration costs, and the need for game theory expertise. Organizational resistance to change and adaptation to new analytical frameworks are additional challenges.

- 2.

- Integration with Existing Tools: The framework can align synergistically with existing platforms such as threat intelligence systems, SIEM, and EDR tools. These integrations can enhance decision-making and optimize forensic investigation response times.

- 3.

- Decision Support Systems: Game-theoretic models can augment decision support processes by helping security teams prioritize investments, allocate resources, and optimize incident response based on adaptive risk modeling.

- 4.

- Training and Awareness Programs: Building internal capability is crucial. Training programs integrating game-theoretic principles into cybersecurity curricula can strengthen decision-making under adversarial uncertainty.

- 5.

- Collaborative Defense Strategies: The framework supports collective defense through shared intelligence and coordinated responses. Collaborative action can improve deterrence and resilience against complex, multi-organizational threats.

- 6.

- Policy Implications: Incorporating game theory into cybersecurity has policy ramifications, including regulatory alignment, responsible behavior standards, and ethical considerations regarding autonomous or strategic decision models.

- 7.

- Case Studies and Use Cases: Documented implementations of game-theoretic approaches demonstrate measurable improvements in risk response and forensic readiness. Future research can expand these to varied industry sectors.

- 8.

- Future Directions: Continued innovation in game model development, integration with AI-driven threat analysis, and tackling emerging cyber challenges remain promising directions.

5.1. Forensicability and Non-Forensicability

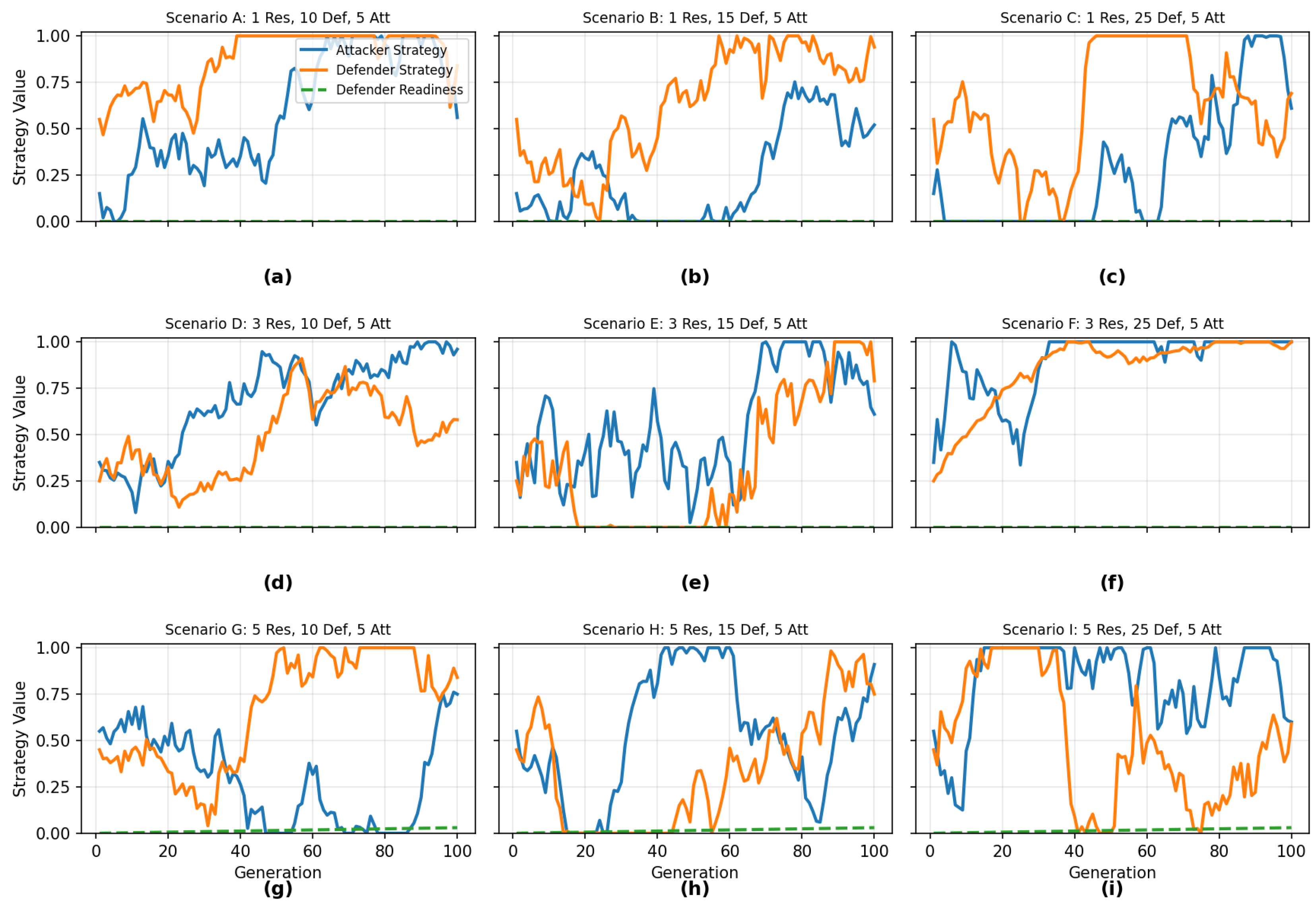

5.2. Evolutionary Game Theory Analysis

- Evolutionary Dynamics: Attackers and defenders co-adapt in continuous feedback cycles; the success of one influences the next strategic shift in the other.

- Replication and Mutation: Successful tactics replicate, while mutations introduce strategic diversity critical for both exploration and adaptation.

- Equilibrium and Stability: Evolutionary Stable Strategies (ESS) represent steady states where neither party benefits from deviation.

- Co-evolutionary Context: The model exposes the perpetual nature of cyber escalation, showing that proactive defense and continuous readiness optimization are essential to remain resilient.

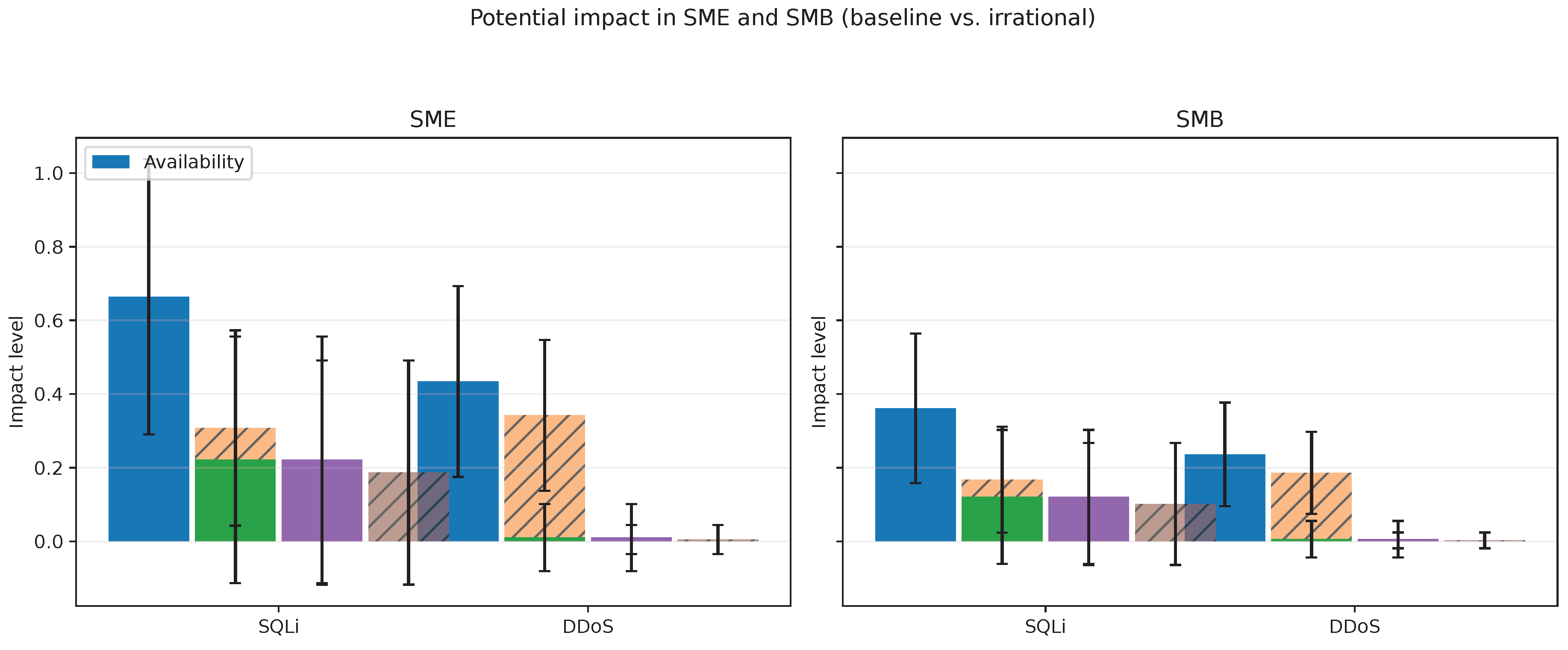

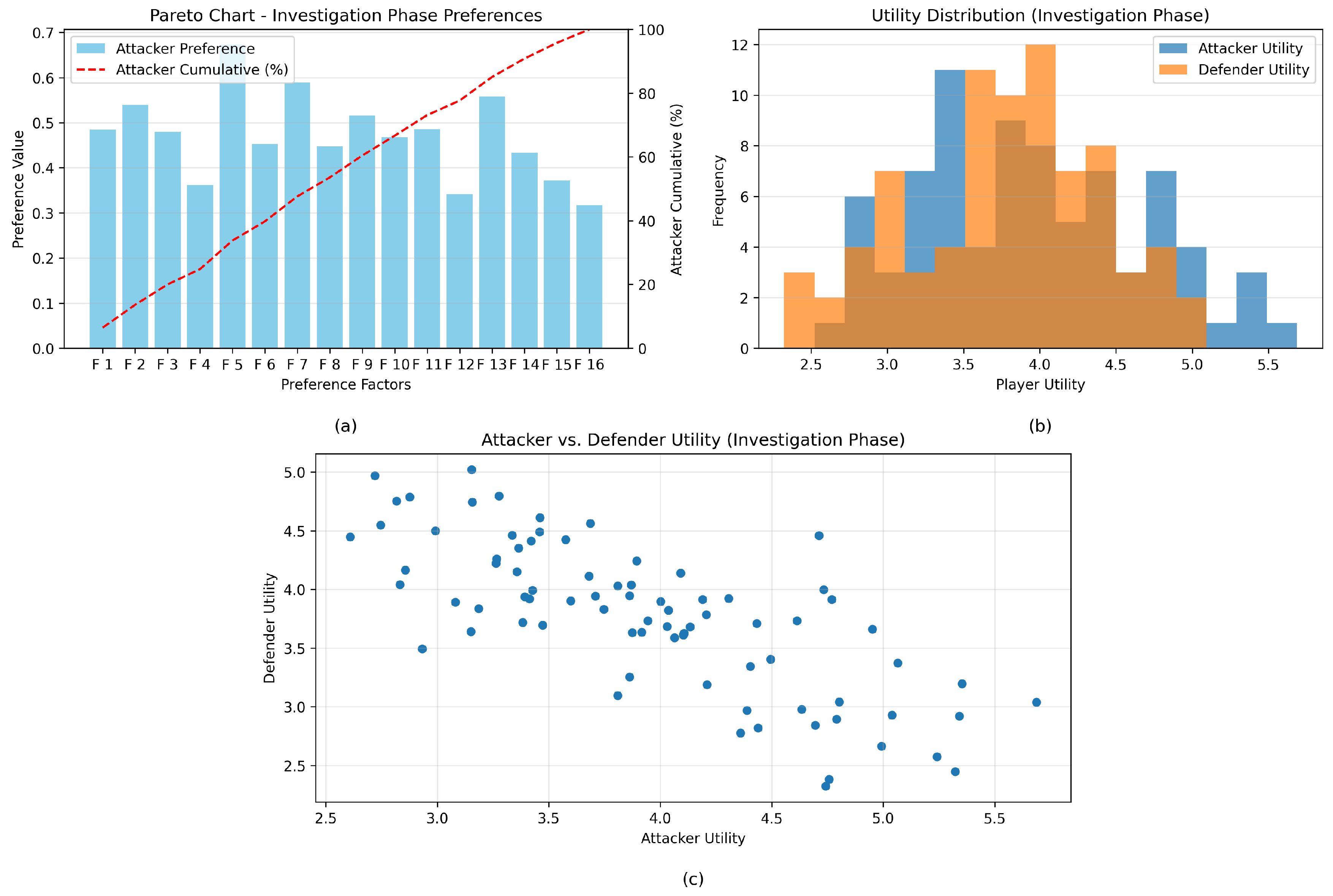

5.3. Attack Impact on Readiness and Investigation Phases

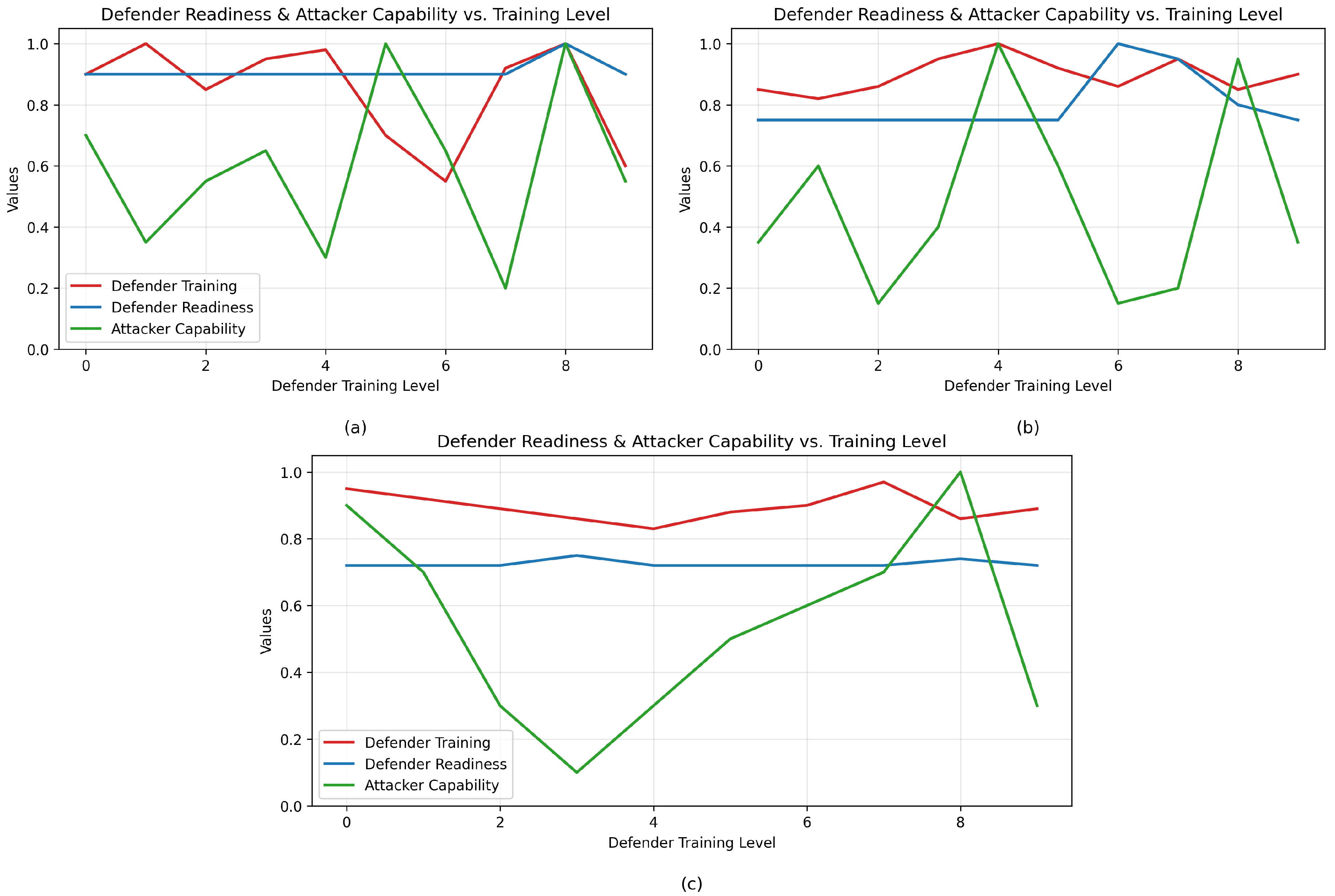

5.4. Readiness and Training Level of the Defender

5.5. Attack Success and Evidence Collection Rates

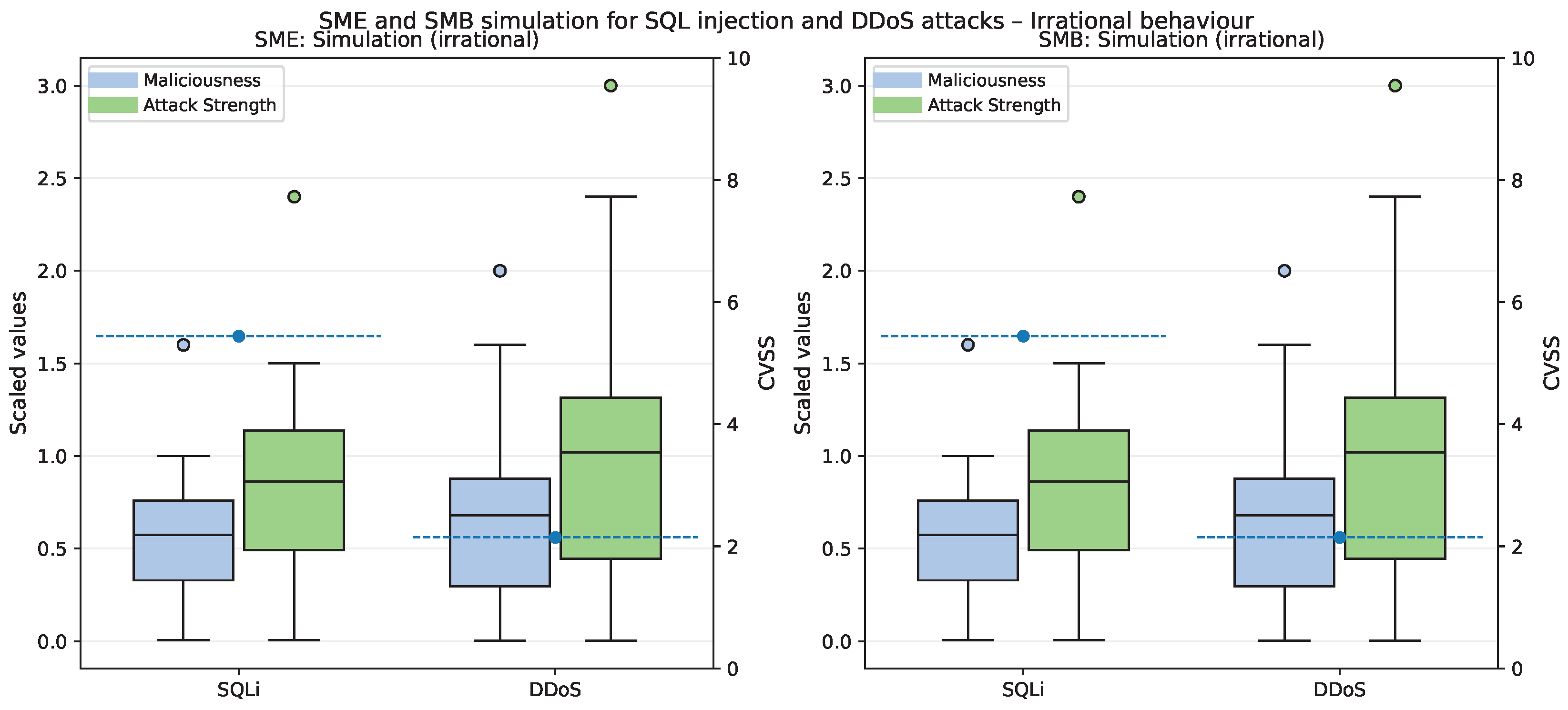

5.6. Comparative Analysis in SMB and SME Organizations

5.6.1. Irrational Attacker Behavior Analysis

5.7. Limitations and Future Work

- Model Complexity: Real-world human elements and deep organizational dynamics may extend beyond current model parameters.

- Data Availability: Reliance on open-source ATT&CK and D3FEND datasets limits coverage of emerging threat behaviors.

- Computational Needs: Evolutionary modeling and large-scale simulations require high-performance computing resources.

- Expert Bias: AHP-based weighting depends on expert judgment, introducing potential subjective bias despite structured controls.

- Real-time Adaptive Models: Integrating continuous learning to instantly adapt to threat changes.

- AI/ML Integration: Employing predictive modeling for attacker intent recognition and defense automation.

- Cross-Organizational Collaboration: Expanding to cooperative game structures for shared threat response.

- Empirical Validation: Conducting large-scale quantitative studies to reinforce and generalize model applicability.

6. Conclusion

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Future Research Directions

- Extended Environmental Applications: Adapting the framework to cloud-native, IoT, and blockchain ecosystems where architectural differences create distinct forensic challenges.

- Dynamic Threat Intelligence Integration: Employing real-time data feeds and AI-based analytics to enable adaptive recalibration of utilities and strategy distributions.

- Standardized Readiness Benchmarks: Developing comparative industry baselines for forensic maturity that support cross-organizational evaluation and improvement.

- Automated Response Coupling: Integrating automated incident response and orchestration tools to bridge the gap between detection and remediation.

- Enhanced Evolutionary Models: Expanding evolutionary game formulations to capture longer-term strategic co-adaptations between attackers and defenders.

- Large-Scale Empirical Validation: Conducting multi-sector, empirical measurement campaigns to statistically validate and refine equilibrium predictions.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| APT | Advanced Persistent Threat |

| ATT&CK | MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge |

| CASE | Cyber-investigation Analysis Standard Expression |

| CIA | Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability (triad) |

| CSIRT | Computer Security Incident Response Team |

| CVSS | Common Vulnerability Scoring System |

| D3FEND | MITRE Defensive Countermeasures Knowledge Graph |

| DFIR | Digital Forensics and Incident Response |

| DFR | Digital Forensic Readiness |

| DDoS | Distributed Denial of Service |

| EDR | Endpoint Detection and Response |

| EGT | Evolutionary Game Theory |

| ESS | Evolutionarily Stable Strategy |

| IDPS | Intrusion Detection and Prevention System |

| JCP | Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| MNE | Mixed Nash Equilibrium |

| NDR | Network Detection and Response |

| NE | Nash Equilibrium |

| PNE | Pure Nash Equilibrium |

| SIEM | Security Information and Event Management |

| SMB | Small and Medium Business |

| SME | Small and Medium Enterprise |

| SQLi | Structured Query Language injection |

| TTP | Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures |

| UCO | Unified Cyber Ontology |

| XDR | Extended Detection and Response |

Appendix A. Simulation Model and Settings

Readiness Components

Outcome Probabilities

Sampling and Maturity Regimes

- Junior+Mid+Senior: , ;

- Mid+Senior: , ;

- Senior: , .

Experiment Size and Uncertainty

References

- Chen, P.; Desmet, L.; Huygens, C. A study on advanced persistent threats. In Proceedings of the Communications and Multimedia Security: 15th IFIP TC 6/TC 11 International Conference, CMS 2014, Aveiro, Portugal, 2014. Proceedings 15. Springer, 2014, September 25-26; pp. 63–72.

- Scott, J.S.; R. . Advanced Persistent Threats: Recognizing the Danger and Arming Your Organization. IT Professional 2015, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlingson, R. A ten step process for forensic readiness. International Journal of Digital Evidence 2004, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Naraine, R. Researchers spot APTs targeting small business MSPs, 2023.

- Johnson, R. 60 percent of small companies close within 6 months of being hacked,, 2019.

- Baker, P. The SolarWinds hack timeline: Who knew what, and when?, 2021.

- Batool, A.; Zowghi, D.; Bano, M. AI governance: a systematic literature review. AI and Ethics.

- Wrightson, T. Advanced persistent threat hacking: the art and science of hacking any organization; McGraw-Hill Education Group, 2014.

- Årnes, A. Digital forensics; John Wiley & Sons, 2017.

- Griffith, S.B. Sun Tzu: The art of war; Vol. 39, Oxford University Press London, 1963.

- Myerson, R.B. Game theory; Harvard university press, 2013.

- Belton, V.; Stewart, T. Multiple criteria decision analysis: an integrated approach; Springer Science & Business Media, 2002.

- Lye, K.w.; Wing, J.M. Game strategies in network security. International Journal of Information Security 2005, 4, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Ellis, C.; Shiva, S.; Dasgupta, D.; Shandilya, V.; Wu, Q. A survey of game theory as applied to network security. In Proceedings of the 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE; 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Basar, T. Game-theoretic methods for robustness, security, and resilience of cyberphysical control systems: games-in-games principle for optimal cross-layer resilient control systems. IEEE Control Systems Magazine 2015, 35, 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, K.; Chevalier, S.; Grance, T. Guide to integrating forensic techniques into incident. Tech. Rep. 800-86.

- Alpcan, T.; Başar, T. Network security: A decision and game-theoretic approach. Cambridge University Press 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, E. Digital evidence and computer crime: Forensic science, computers, and the internet; Academic press, 2011.

- Manshaei, M.H.; Zhu, Q.; Alpcan, T.; Bacşar, T.; Hubaux, J.P. Game theory meets network security and privacy. Acm Computing Surveys (Csur) 2013, 45, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisioti, A.; Loukas, G.; Rass, S.; Panaousis, E. Game-theoretic decision support for cyber forensic investigations. Sensors 2021, 21, 5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanabadi, S.S.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. A game-theoretic defensive approach for forensic investigators against rootkits. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2020, 33, 200909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabiyik, U.; Karabiyik, T. A game theoretic approach for digital forensic tool selection. Mathematics 2020, 8, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanabadi, S.S.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. A memory-based game-theoretic defensive approach for digital forensic investigators. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2021, 38, 301214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporusso, N.; Chea, S.; Abukhaled, R. A game-theoretical model of ransomware. In Proceedings of the Advances in Human Factors in Cybersecurity: Proceedings of the AHFE 2018 International Conference on Human Factors in Cybersecurity, July 21-25, 2018, Loews Sapphire Falls Resort at Universal Studios, Orlando, Florida, USA 9.

- Kebande, V.R.; Venter, H.S. Novel digital forensic readiness technique in the cloud environment. Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences 2018, 50, 552–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebande, V.R.; Karie, N.M.; Choo, K.R.; Alawadi, S. Digital forensic readiness intelligence crime repository. Security and Privacy 2021, 4, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englbrecht, L.; Meier, S.; Pernul, G. Towards a capability maturity model for digital forensic readiness. Wireless Networks 2020, 26, 4895–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.; Venter, H.S. The architecture of a digital forensic readiness management system. Computers & security 2013, 32, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Grobler, C.P.; Louwrens, C. Digital forensic readiness as a component of information security best practice. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Information Security Conference. Springer; 2007; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhdhar, Y.; Rekhis, S.; Sabir, E. A Game Theoretic Approach For Deploying Forensic Ready Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks (SoftCOM). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Elyas, M.; Ahmad, A.; Maynard, S.B.; Lonie, A. Digital forensic readiness: Expert perspectives on a theoretical framework. Computers & Security 2015, 52, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiquni, I.Z.; Amiruddin, A. A case study of digital forensic readiness level measurement using DiFRI model. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Informatics, Multimedia, 2022, Cyber and Information System (ICIMCIS). IEEE; pp. 184–189.

- Rawindaran, N.; Jayal, A.; Prakash, E. Cybersecurity Framework: Addressing Resiliency in Welsh SMEs for Digital Transformation and Industry 5.0. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2025, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenwith, P.M.; Venter, H.S. Digital forensic readiness in the cloud. In Proceedings of the 2013 Information Security for South Africa. IEEE; 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, D.; Yu, Y.; Zisman, A.; Nuseibeh, B. Adaptive Observability for Forensic-Ready Microservice Systems. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Legrand, E.; Åberg, O.; Lagerström, R. Cyber security threat modeling based on the MITRE Enterprise ATT&CK Matrix. Software and Systems Modeling 2022, 21, 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Neil, M. A Bayesian-network-based cybersecurity adversarial risk analysis framework with numerical examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.00471, arXiv:2106.00471 2021.

- Usman, N.; Usman, S.; Khan, F.; Jan, M.A.; Sajid, A.; Alazab, M.; Watters, P. Intelligent dynamic malware detection using machine learning in IP reputation for forensics data analytics. Future Generation Computer Systems 2021, 118, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lal, C.; Conti, M.; Hu, D. LEChain: A blockchain-based lawful evidence management scheme for digital forensics. Future Generation Computer Systems 2021, 115, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Seno, S.A.H. Detecting the software usage on a compromised system: A triage solution for digital forensics. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2023, 44, 301484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rother, C.; Chen, B. Reversing File Access Control Using Disk Forensics on Low-Level Flash Memory. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2024, 4, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkel, B. Registration Data Access Protocol (RDAP) for digital forensic investigators. Digital Investigation 2017, 22, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkel, B. Fintech forensics: Criminal investigation and digital evidence in financial technologies. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2020, 33, 200908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Seok, B.; Lee, C. Digital forensic investigation framework for the metaverse. The Journal of Supercomputing 2023, 79, 9467–9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, S. Digital forensics meets ai: A game-changer for the 4th industrial revolution. In Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain in Digital Forensics; River Publishers, 2023; pp. 1–20.

- Tok, Y.C.; Chattopadhyay, S. Identifying threats, cybercrime and digital forensic opportunities in Smart City Infrastructure via threat modeling. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2023, 45, 301540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, G.M.; Whinston, A.B. Security defense against long-term and stealthy cyberattacks. Decision Support Systems 2023, 166, 113912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Snowe, M.J. A taxonomy of cybercrime: Theory and design. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 2020, 38, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.; Barnum, S.; Griffith, R.; Snyder, J.; van Beek, H.; Nelson, A. Advancing coordinated cyber-investigations and tool interoperability using a community developed specification language. Digital investigation 2017, 22, 14–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, M.E. The complexity of vertex enumeration methods. Mathematics of Operations Research 1983, 8, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, V.; Campbell, J. Nashpy: A Python library for the computation of Nash equilibria. Journal of Open Source Software 2018, 3, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopounidis, C.; Pardalos, P.M. Handbook of multicriteria analysis; Vol. 103, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- Bipm, I.; Ifcc, I.; Iso, I. IUPaP, and OImL. Evaluation of measurement data—Supplement 2008, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Analytic hierarchy process. In Encyclopedia of operations research and management science; Springer, 2013; pp. 52–64.

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t5 | t6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| s2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| s3 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| s4 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| s5 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| s6 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| s7 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| s8 | 32 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 33 | 32 |

| s9 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 30 | 33 | 32 |

| s10 | 32 | 35 | 36 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| s11 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 6 | 35 | 30 |

| s12 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 0 | 0 |

| s13 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| s14 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t5 | t6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 |

| s2 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| s3 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 8 | 11 |

| s4 | 8 | 10 | 25 | 25 | 9 | 12 |

| s5 | 9 | 11 | 24 | 8 | 10 | 13 |

| s6 | 10 | 12 | 24 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| s7 | 11 | 21 | 20 | 10 | 12 | 7 |

| s8 | 18 | 14 | 25 | 9 | 5 | 25 |

| s9 | 13 | 15 | 23 | 12 | 4 | 8 |

| s10 | 14 | 16 | 22 | 11 | 14 | 9 |

| s11 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| s12 | 16 | 18 | 21 | 13 | 15 | 25 |

| s13 | 17 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 16 | 17 |

| s14 | 12 | 19 | 29 | 16 | 17 | 16 |

| Metric | Description | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Attack Success Rate (ASR) | Attack success rate is nearly nonexistent | 0 |

| Attacks are occasionally successful | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Attacks are successful about half of the time | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Attacks are usually successful | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Attacks are always successful | 1 | |

| Resource Efficiency (RE) | Attacks require considerable resources with low payoff | 0 |

| Attacks require significant resources but have a moderate payoff | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Attacks are somewhat resource efficient | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Attacks are quite resource efficient | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Attacks are exceptionally resource efficient | 1 | |

| Stealthiness (ST) | Attacks are always detected and attributed | 0 |

| Attacks are usually detected and often attributed | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Attacks are sometimes detected and occasionally attributed | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Attacks are seldom detected and rarely attributed | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Attacks are never detected nor attributed | 1 | |

| Data Exfiltration Effectiveness (DEE) | Data exfiltration attempts always fail | 0 |

| Data exfiltration attempts succeed only occasionally | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Data exfiltration attempts often succeed | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Data exfiltration attempts usually succeed | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Data exfiltration attempts always succeed | 1 | |

| Time-to-Exploit (TTE) | Vulnerabilities are never successfully exploited before patching | 0 |

| Vulnerabilities are exploited before patching only occasionally | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Vulnerabilities are often exploited before patching | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Vulnerabilities are usually exploited before patching | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Vulnerabilities are always exploited before patching | 1 | |

| Evasion of Countermeasures (EC) | Countermeasures always successfully thwart attacks | 0 |

| Countermeasures often successfully thwart attacks | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Countermeasures sometimes fail to thwart attacks | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Countermeasures often fail to thwart attacks | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Countermeasures never successfully thwart attacks | 1 | |

| Attribution Resistance (AR) | The attacker is always accurately identified | 0 |

| The attacker is often accurately identified | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker is sometimes accurately identified | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker is seldom accurately identified | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker is never accurately identified | 1 | |

| Reusability of Attack Techniques (RT) | Attack techniques are always one-off, never reusable | 0 |

| Attack techniques are occasionally reusable | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Attack techniques are often reusable | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Attack techniques are usually reusable | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Attack techniques are always reusable | 1 | |

| Impact of Attacks (IA) | Attacks cause no notable disruption or loss | 0 |

| Attacks cause minor disruption or loss | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Attacks cause moderate disruption or loss | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Attacks cause major disruption or loss | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Attacks cause catastrophic disruption or loss | 1 | |

| Persistence (P) | The attacker cannot maintain control over compromised systems | 0 |

| The attacker occasionally maintains control over compromised systems | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker often maintains control over compromised systems | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker usually maintains control over compromised systems | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker always maintains control over compromised systems | 1 | |

| Adaptability (AD) | The attacker is unable to adjust strategies in response to changing defenses | 0 |

| The attacker occasionally adjusts strategies in response to changing defenses | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker often adjusts strategies in response to changing defenses | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker usually adjusts strategies in response to changing defenses | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker always adjusts strategies in response to changing defenses | 1 | |

| Deniability (DN) | The attacker cannot deny involvement in attacks | 0 |

| The attacker can occasionally deny involvement in attacks | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker can often deny involvement in attacks | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker can usually deny involvement in attacks | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker can always deny involvement in attacks | 1 | |

| Longevity (LG) | The attacker’s operations are quickly disrupted | 0 |

| The attacker’s operations are often disrupted | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker’s operations are occasionally disrupted | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker’s operations are rarely disrupted | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker’s operations are never disrupted | 1 | |

| Collaboration (CB) | The attacker never collaborates with others | 0 |

| The attacker occasionally collaborates with others | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker often collaborates with others | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker usually collaborates with others | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker always collaborates with others | 1 | |

| Financial Gain (FG) | The attacker never profits from attacks | 0 |

| The attacker occasionally profits from attacks | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker often profits from attacks | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker usually profits from attacks | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker always profits from attacks | 1 | |

| Reputation and Prestige (RP) | The attacker gains no reputation or prestige from attacks | 0 |

| The attacker gains little reputation or prestige from attacks | 0.1–0.3 | |

| The attacker gains some reputation or prestige from attacks | 0.4–0.6 | |

| The attacker gains considerable reputation or prestige from attacks | 0.7–0.9 | |

| The attacker’s reputation or prestige is greatly enhanced by each attack | 1 |

| Metric | Description | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Logging and Audit Trail Capabilities (L) | No logging or audit trail capabilities | 0 |

| Minimal or ineffective logging and audit trail capabilities | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Moderate logging and audit trail capabilities | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Robust logging and audit trail capabilities with some limitations | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Comprehensive and highly effective logging and audit trail capabilities | 1 | |

| Integrity and Preservation of Digital Evidence (I) | Complete loss of all digital evidence, including backups | 0 |

| Severe damage or compromised backups with limited recoverability | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Partial loss of digital evidence, with some recoverable data | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Reasonable integrity and preservation of digital evidence, with recoverable backups | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Full integrity and preservation of all digital evidence, including secure and accessible backups | 1 | |

| Documentation and Compliance with Digital Forensic Standards (D) | No documentation or non-compliance with digital forensic standards | 0 |

| Incomplete or inadequate documentation and limited adherence to digital forensic standards | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Basic documentation and partial compliance with digital forensic standards | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Well-documented processes and good adherence to digital forensic standards | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Comprehensive documentation and strict compliance with recognized digital forensic standards | 1 | |

| Volatile Data Capture Capabilities (VDCC) | No volatile data capture capabilities | 0 |

| Limited or unreliable volatile data capture capabilities | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Moderate volatile data capture capabilities | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Effective volatile data capture capabilities with some limitations | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Robust and reliable volatile data capture capabilities | 1 | |

| Encryption and Decryption Capabilities (E) | No encryption or decryption capabilities | 0 |

| Weak or limited encryption and decryption capabilities | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Moderate encryption and decryption capabilities | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Strong encryption and decryption capabilities with some limitations | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Highly secure encryption and decryption capabilities | 1 | |

| Incident Response Preparedness (IR) | No incident response plan or team in place | 0 |

| Initial incident response plan, not regularly tested or updated, with limited team capability | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Developed incident response plan, periodically tested, with trained team | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Comprehensive incident response plan, regularly tested and updated, with a well-coordinated team | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Advanced incident response plan, continuously tested and optimized, with a dedicated, experienced team | 1 | |

| Data Recovery Capabilities (DR) | No data recovery processes or tools in place | 0 |

| Basic data recovery tools, with limited effectiveness | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Advanced data recovery tools, with some limitations in terms of capabilities | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Sophisticated data recovery tools, with high success rates | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Comprehensive data recovery tools and processes, with excellent success rates | 1 | |

| Network Forensics Capabilities (NF) | No network forensic capabilities | 0 |

| Basic network forensic capabilities, limited to capturing packets or logs | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Developed network forensic capabilities, with ability to analyze traffic and detect anomalies | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Advanced network forensic capabilities, with proactive threat detection | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Comprehensive network forensic capabilities, with full spectrum threat detection and automated responses | 1 | |

| Staff Training and Expertise (ST) | No trained staff or expertise in digital forensics | 0 |

| Few staff members with basic training in digital forensics | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Several staff members with intermediate-level training, some with certifications | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Most staff members with advanced-level training, many with certifications | 0.7–0.9 | |

| All staff members are experts in digital forensics, with relevant certifications | 1 | |

| Legal & Regulatory Compliance (LR) | Non-compliance with applicable legal and regulatory requirements | 0 |

| Partial compliance with significant shortcomings | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Compliance with most requirements, some minor issues | 0.4–0.6 | |

| High compliance with only minor issues | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Full compliance with all relevant legal and regulatory requirements | 1 | |

| Accuracy (A) | No consistency in results, many errors and inaccuracies in digital forensic analysis | 0 |

| Frequent errors in analysis, high level of inaccuracy | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Some inaccuracies in results, needs further improvement | 0.4–0.6 | |

| High level of accuracy, few inconsistencies or errors | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Extremely accurate, consistent results with virtually no errors | 1 | |

| Completeness (C) | Significant data overlooked, very incomplete analysis | 0 |

| Some relevant data collected, but analysis remains substantially incomplete | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Most of the relevant data collected and analyzed, but some gaps remain | 0.4–0.6 | |

| High degree of completeness in data collection and analysis, minor gaps | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Comprehensive data collection and analysis, virtually no information overlooked | 1 | |

| Timeliness (T) | Extensive delays in digital forensic investigation process, no urgency | 0 |

| Frequent delays, slow response time | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Reasonable response time, occasional delays | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Quick response time, infrequent delays | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Immediate response, efficient process, no delays | 1 | |

| Reliability (R) | Unreliable techniques, inconsistent and unrepeatable results | 0 |

| Some reliability in techniques, but results are often inconsistent | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Mostly reliable techniques, occasional inconsistencies in results | 0.4–0.6 | |

| High reliability in techniques, few inconsistencies | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Highly reliable and consistent techniques, results are dependable and repeatable | 1 | |

| Validity (V) | No adherence to standards, methods not legally or scientifically acceptable | 0 |

| Minimal adherence to standards, many methods not acceptable | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Moderate adherence to standards, some methods not acceptable | 0.4–0.6 | |

| High adherence to standards, majority of methods are acceptable | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Strict adherence to standards, all methods used are legally and scientifically acceptable | 1 | |

| Preservation (P) | No procedures in place for evidence preservation, evidence frequently damaged or lost | 0 |

| Minimal preservation procedures, evidence sometimes damaged or lost | 0.1–0.3 | |

| Moderate preservation procedures, occasional evidence damage or loss | 0.4–0.6 | |

| Robust preservation procedures, rare instances of evidence damage or loss | 0.7–0.9 | |

| Comprehensive preservation procedures, virtually no damage or loss of evidence | 1 |

| Metric (Attacker) | Weight | Metric (Defender) | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASR | 0.1094 | L | 0.0881 | |

| RE | 0.0476 | I | 0.0881 | |

| ST | 0.0921 | D | 0.0423 | |

| DEE | 0.0887 | VDCC | 0.0642 | |

| TTE | 0.0476 | E | 0.0461 | |

| EC | 0.0887 | IR | 0.0881 | |

| AR | 0.0814 | DR | 0.0481 | |

| RT | 0.0476 | NF | 0.0819 | |

| IA | 0.0921 | ST | 0.0819 | |

| P | 0.0814 | LR | 0.0481 | |

| AD | 0.0571 | A | 0.0557 | |

| DN | 0.0264 | C | 0.0460 | |

| LG | 0.0433 | T | 0.0693 | |

| CB | 0.0262 | R | 0.0531 | |

| FG | 0.0210 | V | 0.0423 | |

| RP | 0.0487 | P | 0.0557 |

| File No. | L | I | D | VDCC | E | IR | DR | NF | ST | LR | A | C | T | R | V | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| case1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| case2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| case3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| case4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| case5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| case6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| case7 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| case8 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| case9 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| case10 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| File No. | L | I | D | VDCC | E | IR | DR | NF | ST | LR | A | C | T | R | V | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| case1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| case2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| case3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| case4 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| case5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| case6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| case7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| case8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| case9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| case10 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Resources | Defenders | Attackers | Scenario | Final Value | Avg. Attacker Strategy | Avg. Defender Strategy | Avg. Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 5 | a | 0.56 | 0.84 | – | 0.00 |

| 1 | 15 | 5 | b | 0.52 | 0.94 | – | 0.00 |

| 1 | 25 | 5 | c | 0.61 | 0.69 | – | 0.00 |

| 3 | 10 | 5 | d | 0.96 | 0.58 | – | 0.00 |

| 3 | 25 | 5 | f | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 0.00 |

| 5 | 15 | 5 | h | 0.91 | 0.75 | – | 0.03 |

| Low | Medium | High | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attack success rate | 0.25 ± 0.0038 | 0.53 ± 0.0044 | 0.75 ± 0.0038 |

| Evidence collection rate | 0.93 ± 0.0022 | 0.96 ± 0.0017 | 0.94 ± 0.0021 |

| ID | SME | SMB | Impact metrics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Malic. | Str. | Impact | CVSS | Type | Malic. | Str. | Impact | CVSS | Workload | Avail. | Conf. | Integ. | |

| 0 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 7 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 7 | 1.125 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | SQLI | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 9 | SQLI | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 9 | 2.7 | 2.58 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| 2 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | Med | 0 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | Med | 0 | 1.125 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | SQLI | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 9 | SQLI | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 9 | 1.125 | 1.005 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| 4 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | Low | 0 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | Low | 0 | 1.125 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | SQLI | 0.75 | 1.12 | Med | 7 | SQLI | 0.75 | 1.12 | Med | 7 | 2.7 | 2.58 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| ID | SME | SMB | Impact metrics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Malic. | Str. | Impact | CVSS | Type | Malic. | Str. | Impact | CVSS | Workload | Avail. | Conf. | Integ. | |

| 0 | SQLI | 0.49 | 0.73 | Med | 7 | SQLI | 0.49 | 0.73 | Med | 7 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| 1 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 7 | DDoS | 0.75 | 1.12 | High | 7 | 1.12 | 0.80 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | DDoS | 0.80 | 1.21 | High | 7 | DDoS | 0.80 | 1.21 | High | 7 | 1.21 | 0.80 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | SQLI | 0.16 | 0.24 | High | 9 | SQLI | 0.16 | 0.24 | High | 9 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| 4 | SQLI | 0.58 | 0.87 | High | 9 | SQLI | 0.58 | 0.87 | High | 9 | 2.45 | 2.33 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| 5 | DDoS | 0.84 | 1.26 | High | 7 | DDoS | 0.84 | 1.26 | High | 7 | 2.84 | 0.80 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).