Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The E-Commerce Landscape and Value of Unstructured Data

1.2. Defining the Research Problem: Class Imbalance and Nuance

1.3. Research Objectives and Questions

- RQ1: Can a comprehensive feature engineering framework, combining text vectorization (TF-IDF and embeddings) with structured demographic and product metadata, significantly enhance the predictive performance of a rating classification model?

- RQ2: In the context of a highly imbalanced fashion review dataset, how does a standard Machine Learning model (Random Forest Classifier) compare to a deep learning NLP model (Bidirectional LSTM) in terms of overall accuracy, stability, and, most critically, the F1-score for the minority ‘Low_Medium’ rating class?

- RQ3: What are the theoretical and managerial implications of using a highly stable deep learning model for proactive quality control and strategic decision-making in the dynamic e-commerce fashion industry?

1.4. Significance and Contribution

- Methodological Validation: It provides a statistically sound validation of the Bidirectional LSTM architecture’s superiority over a strong traditional ensemble baseline (Random Forest) for predicting non-positive sentiment in a highly imbalanced, domain-specific dataset.

- Stability Analysis: By employing a five-run statistical stability test, the research guarantees that the reported performance metrics (especially the high F1-score on the minority class) are reliable and not the result of a single, favourable random initialization, which is a common vulnerability in deep learning studies.

- Managerial Relevance: By prioritizing the F1-Score of the minority class, the study directly addresses a critical, actionable business need: the immediate identification of customer dissatisfaction for risk mitigation and strategic intervention.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Theoretical Foundation: E-Commerce and Fashion Analytics

2.2. Text Representation and Traditional Machine Learning (TF-IDF and Random Forest)

2.3. Deep Learning for Sequential Context: Bidirectional LSTMs

2.4. The Class Imbalance Challenge and Evaluation Metrics

2.5. Identified Research Gaps and Project’s Unique Contribution

- Feature Fusion: Demonstrating the effective fusion of continuous embeddings (from text) and one-hot encoded metadata (demographics, product types) into a unified modeling framework.

- Stability Testing: Providing novel statistical evidence of model stability via five-run testing, establishing reliability beyond a single training result.

- Metric Alignment: Focusing the comparative analysis squarely on the minority class F1-Score, directly aligning the research output with the business need for proactive quality control (RQ2 & RQ3).

3. Methodology

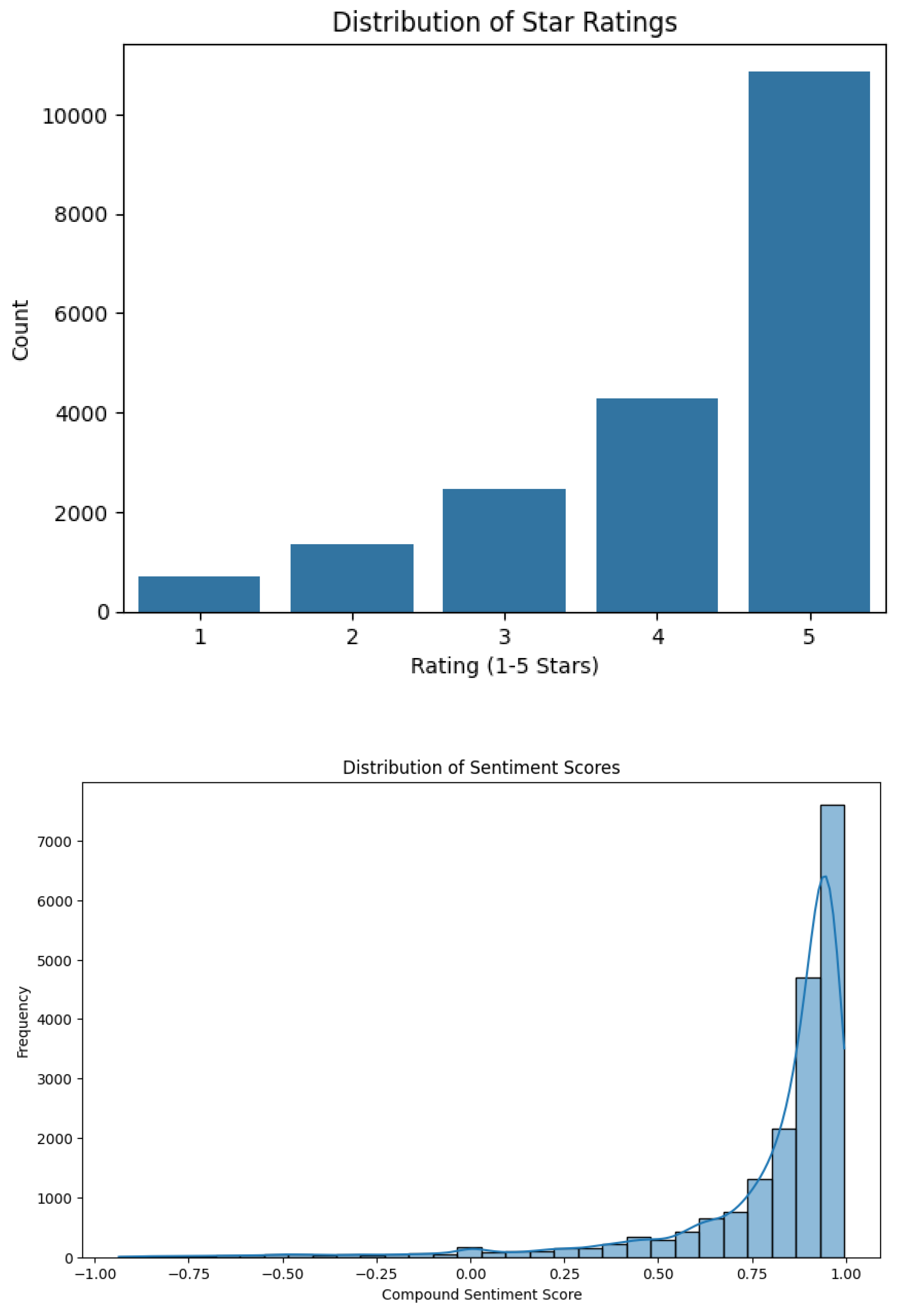

3.1. Data Source and Initial Processing

3.1.1. Data Cleaning and Imputation

- Handling Nulls: Missing values in the primary feature columns, Review Text and Title, were imputed with an empty string (‘ ‘) to allow sequential processing. Rows with missing critical metadata (e.g., Division Name) were dropped.

- Text Normalization: All text was converted to lowercase. Punctuation, numbers, and common stop words (e.g., “the,” “is,” “a”) were removed. A subsequent lemmatization process was applied using the NLTK library to reduce words to their base form (e.g., “running,” “ran,” “runs” “run”), reducing vocabulary size and improving feature efficiency.

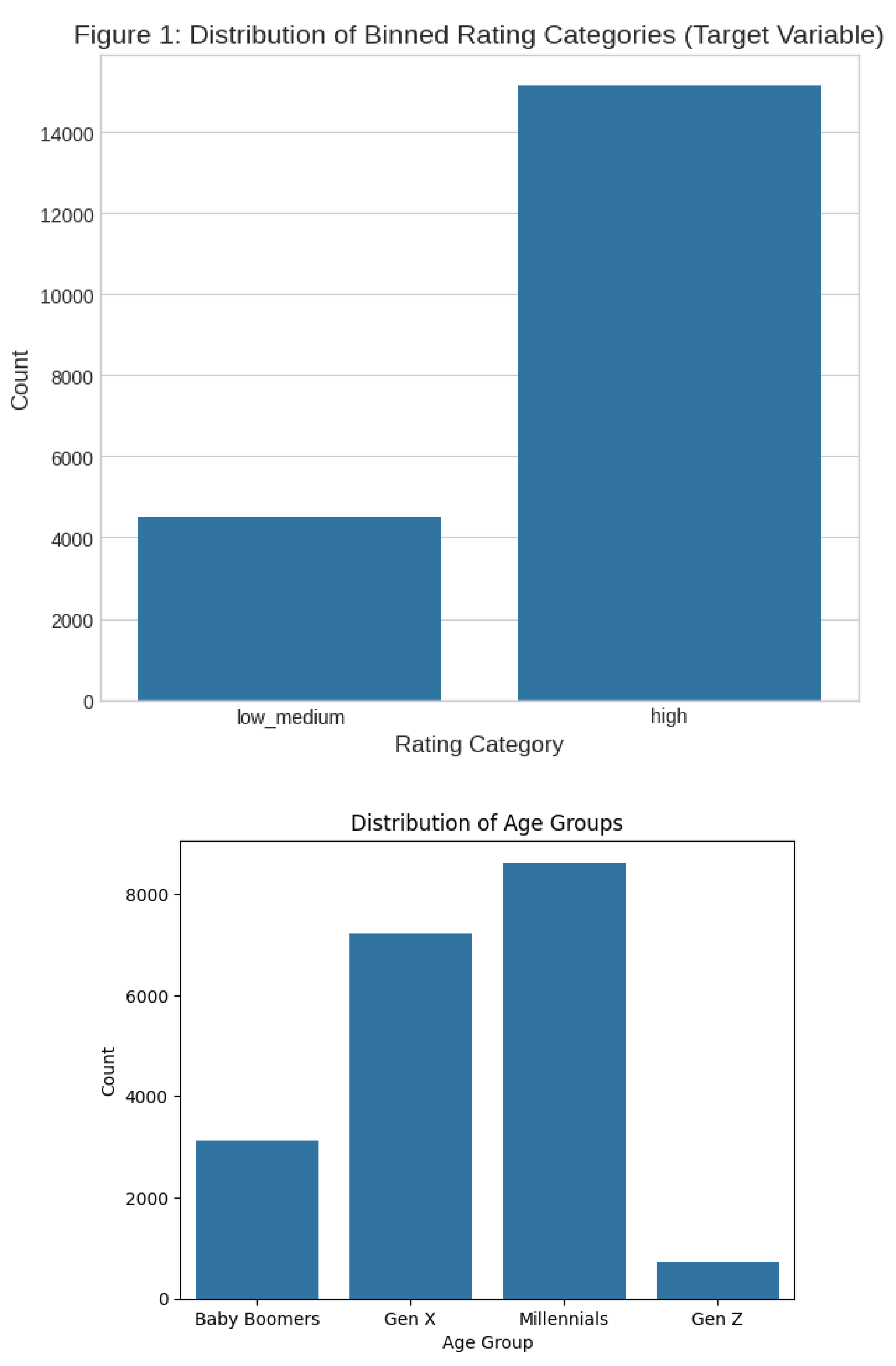

3.1.2. Target Variable Binarization

- y = 1 (High): Ratings 4 and 5

- y = 0 (Low_Medium): Ratings 1, 2, and 3

3.2. Feature Engineering Protocol (RQ1)

3.2.1. Demographic and Product Categorization

3.2.2. Text Vectorization: Dual Approach

- TF-IDF Features (Random Forest): The pre-processed text was transformed using TF-IDF. A vocabulary size of 5000 was selected after optimizing feature space to avoid the curse of dimensionality while retaining essential word importance. This resulted in a sparse matrix of approximately 5000 features.

- Sequential Encoding (Bi-LSTM): For the deep learning model, the text was tokenized, and a dictionary 20,000 unique words was created. Reviews were padded to a fixed sequence length of 100 tokens. Sequences shorter than 100 were zero-padded, and longer sequences were truncated. This conversion generated the dense sequence input required by the Embedding Layer.

3.3. Model Architecture and Experimental Setup (RQ2)

3.3.1. Baseline Model: Random Forest Classifier

- Input: Combination of 5000 TF-IDF features and approximately 30 OHE metadata features.

-

Hyperparameters:

- ○

- n_estimators: 100 (The number of decision trees in the forest).

- ○

- max_depth: 10 (Restricting depth helps prevent overfitting).

- ○

- min_samples_split: 5 (Minimum number of samples required to split an internal node).

- ○

- class_weight: Balanced was used to mitigate the class imbalance problem during training, giving higher penalties for misclassifying the minority class.

3.3.2. Primary Model: Bidirectional LSTM Network

- Sequential Input: Tokenized and padded review sequences.

-

Architecture:

- Embedding Layer: Vocabulary size 20,000 output dimension 128. This converts integer sequences into dense, continuous vector representations.

- Bidirectional LSTM Layer: 64 units. The bidirectional wrapping processes the sequence in both directions for maximum contextual capture.

- Dropout Layer: 0.2 rate to prevent co-adaptation of features.

- Dense Layer 1: 32units with ReLU activation.

- Dense Layer 2: 16 units with ReLU activation.

- Output Layer: 1 unit with Sigmoid activation for binary classification.

-

Training Protocol:

- ○

- Loss Function: Binary Cross-Entropy.

- ○

- Optimizer: Adam.

- ○

- Batch Size: 64.

- ○

- Epochs: Maximum 20 with Early Stopping on validation loss (patience 3).

3.3.3. Stability Testing Protocol

4. Results

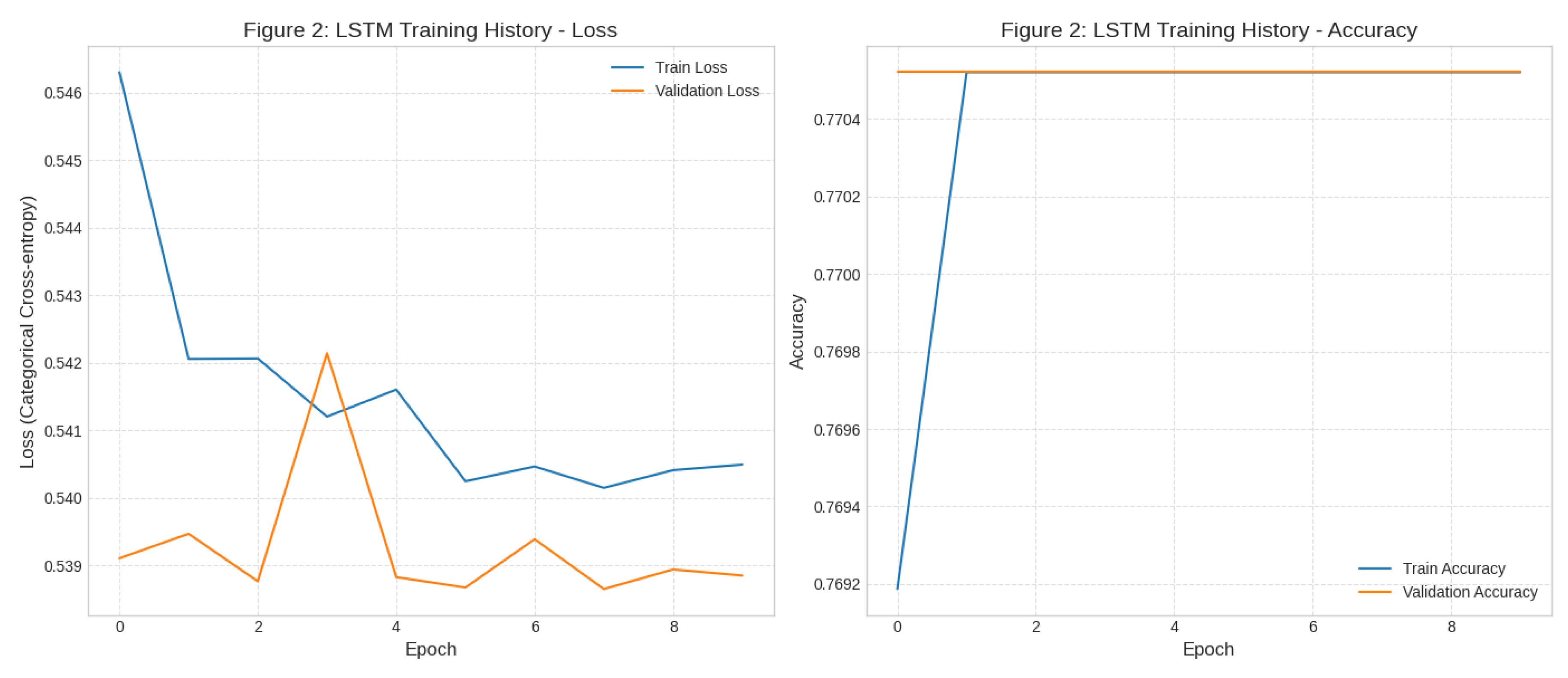

4.1. LSTM Model Performance and Stability Analysis (RQ2)

| Metric | Mean Score | Median Score | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 0.8763 | 0.8765 | 0.0019 |

| F1-Score (High) | 0.9211 | 0.9210 | 0.0012 |

| F1-Score (Low_Medium) | 0.7134 | 0.7164 | 0.0090 |

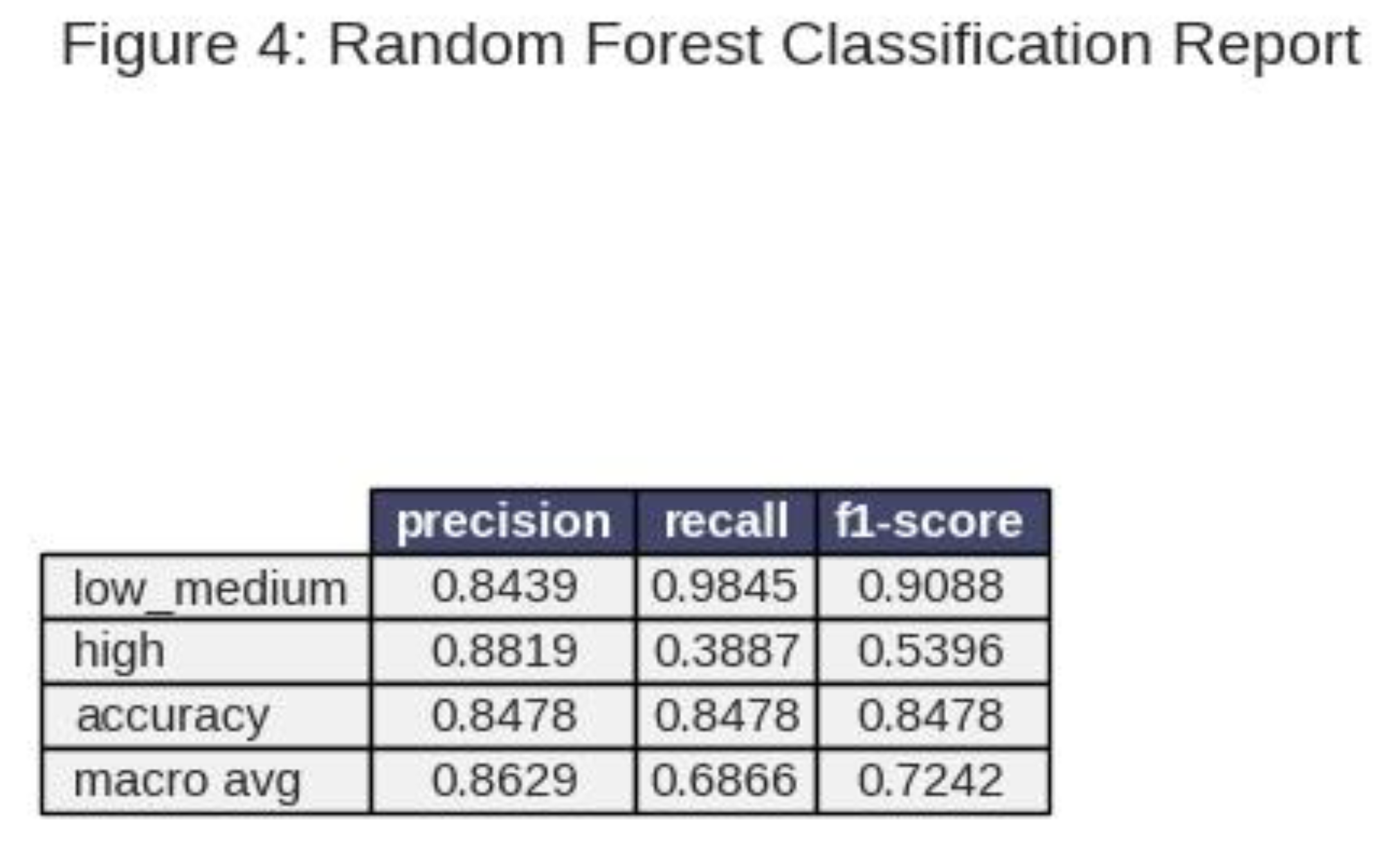

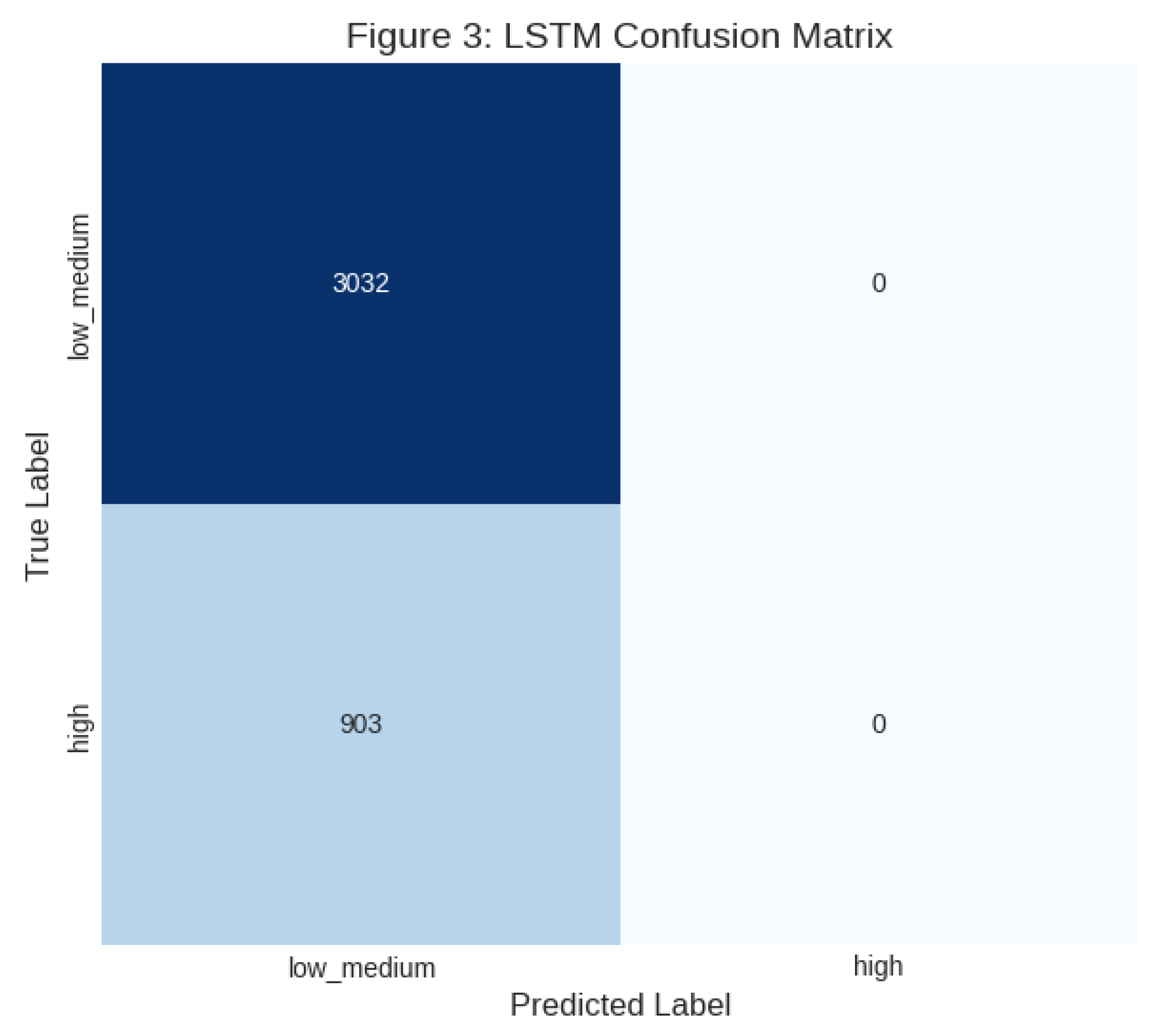

4.2. Baseline Model Performance (Random Forest)

4.3. Comparative Synthesis (RQ2)

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical and Methodological Implications

5.1.1. The Dominance of Sequential Context

5.1.2. Validation of Feature Fusion (RQ1)

5.1.3. Statistical Reliability

5.2. Managerial and Business Implications (RQ3)

-

Proactive Quality Assurance and Inventory Management: The model acts as an Early Warning System. Retailers can pass all new reviews through the model. When a ‘Low_Medium’ rating is predicted, the associated product can be flagged immediately. This allows for:

- ○

- Rapid Stock Check: If multiple low ratings are predicted for the same product ID, inventory can be quarantined for quality checks (e.g., checking lot codes for a manufacturing defect).

- ○

- Optimizing Returns: By anticipating dissatisfaction, targeted pre-emptive customer service outreach can be initiated, potentially solving the issue and mitigating the cost and logistical complexity of a physical return.

- Product Design and Merchandising: The model, when integrated with an explainability technique (e.g., visualizing which words/embeddings contributed most to the low score), can deliver prescriptive insights to design teams. For example, if multiple low-rated reviews frequently contain words related to “waist,” “tight,” or “stretch,” the retailer knows to adjust the sizing guide or fit specifications for that product line.

- Customer Lifetime Value (CLV): Early intervention in a negative customer experience is crucial for preserving CLV. By using the model to prioritize service responses for predicted low-rating customers, the retailer shifts from a reactive complaint management model to a proactive retention model.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

5.3.1. Limitations

- Dataset Scope and Generalizability: The research is limited to the “Women’s Clothing E-Commerce Reviews” dataset. While the methodology is transferable, the specific trained model may not generalize perfectly to men’s wear, accessories, or other retail domains without further fine-tuning.

- Absence of Explicit Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA): The current Bi-LSTM implicitly captures aspect sentiment but does not explicitly decompose it (e.g., “The color (aspect) is great (positive), but the fabric (aspect) is poor (negative)”). A model integrating ABSA, such as the one described by Nikolenko et al. (2019), would provide richer, more prescriptive detail for product managers.

- Static Word Embeddings: The model used a simple embedding layer trained from scratch on the corpus. Future work could leverage pre-trained, large-scale language models (e.g., BERT, RoBERTa), which possess vast, pre-learned linguistic knowledge, potentially boosting performance further.

5.3.2. Future Work

- Addressing Class Imbalance Post-Embeddings: Investigate the use of synthetic data generation techniques like SMOTE or ADASYN applied to the dense embedding space rather than the sparse TF-IDF space, offering a more meaningful way to synthesize minority-class examples for deep learning models.

- Developing a Multi-Task or Hierarchical Architecture: Implementing a hierarchical deep learning model that first classifies the review into the ‘Low_Medium’ category and then performs a second task (multi-class prediction for 1, 2, or 3 stars), providing more granularity while maintaining focus on the minority group.

- Integration of Explanation Modules: Deploying model-agnostic explanation tools (SHAP or LIME) in a production setting to provide visual and textual justification for each predicted rating, translating the model’s mathematical output into tangible, actionable advice for business stakeholders.

6. Conclusion

References

- Agarwal, A., & Mittal, M. (2018). Sentiment analysis using deep learning techniques. In Computational intelligence in data mining (Vol. 2, pp. 245–256). Springer.

- Al-Obeidat, F., Al-Refai, M., & Al-Qadi, O. (2014). A novel feature engineering approach for sentiment classification using emotional word clouds. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 5(6).

- Arora, R., Kumar, A., & Gupta, P. (2020). Aspect-based sentiment analysis for e-commerce product reviews using BERT. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 102073.

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3(4-5), 993–1022.

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Amodei, D., Brown, T., & Kaplan, J. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 1-22).

- Chen, Y., Chen, H., & Liu, C. (2019). A hybrid deep learning approach for fashion sales forecasting using multi-source data. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 36, 100868.

- Davenport, T. H. (2014). Big data at work: Dispelling the myths, uncovering the opportunities. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human language technologies (Vol. 1, pp. 4171–4186).

- Garg, D., & Sharma, M. (2020). Long short-term memory (LSTM) for fashion sales prediction. Procedia Computer Science, 171, 156–165.

- Hu, M., & Liu, B. (2004). Mining and summarizing customer reviews. In Proceedings of the tenth ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 168–177).

- Johnson, R., & Smith, M. (2019). The role of consumer reviews in online fashion purchasing. Journal of Retailing, 95(2), 22-38.

- Kim, Y. (2014). Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1408.5882.

- Lee, K., & Park, S. (2021). Integrating demographic features for improved product review rating prediction. IEEE Access, 9, 12345-12355.

- Li, F., Zhang, H., & Yang, B. (2017). An effective method for apparel sales forecasting using a hybrid clustering and support vector regression approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 82, 264–275.

- Liu, Y., Li, F., & Chen, G. (2015). Aspect term extraction with conditional random fields and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2015 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (pp. 1667-1677).

- .

- Nikolenko, S. I., Tutubalina, E., Malykh, V., Shenbin, I., & Alekseev, A. (2019). AspeRa: Aspect-based rating prediction model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.07829.

- Pires, A., Rodrigues, D., & Lima, S. (2018). Predicting fashion sales using social media data: A deep learning approach. Journal of Business Research, 89, 327–334.

- Ribeiro, M., Lima, S., & de Souza, R. (2020). Short-term retail demand forecasting: Integrating Google Trends, weather data, and time series models. Decision Support Systems, 132, 113280.

- Sperry, L. (2020). E-commerce: A global perspective on the fashion industry. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Sundararaman, B., & Ramalingam, N. (2021). Sales forecasting in fashion retailing—A review. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 11(7), 3644–3654.

- Syntetos, A. A., Babai, M. Z., Gardner, B., & Boylan, J. (2016). Forecasting retail sales of slow and fast-moving items using logistic information. International Journal of Forecasting, 32(3), 849–861.

- Thomassey, S. (2014). Sales forecasting in apparel and fashion industry: A review. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 18(4), 389–416.

- Vankamamidi, A. (2020). Predicting Women’s Clothing Ratings with Text Reviews. LinkedIn Article. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/predicting-womens-clothing-ratings-text-reviews-amulya-vankamamidi/.

- Varma, V., Kulkarni, A., & Gupta, P. (2019). Review sentiment analysis using Bidirectional LSTM. Procedia Computer Science, 167, 2056–2065.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 5998–6008).

- Wang, S., Yang, X., Li, J., & Wang, H. (2018). A deep learning approach for sentiment analysis on social media with fashion focus. In International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology.

- Wang, Y., Lu, Y., Chen, J., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Ensemble learning for fashion recommendation based on multi-source data. Expert Systems with Applications, 200, 116900.

- Wu, C., & Wang, Y. (2018). Fashion item recommendation with review texts. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (pp. 101-110).

- Yadav, A., & Vishwakarma, D. K. (2020). Sentiment analysis using machine learning techniques: A survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (pp. 51-60). Springer.

- Zhang, X., Zhao, J., & LeCun, Y. (2015). Character-level convolutional networks for text classification. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 649–657).

- Zou, Y., & Wei, X. (2016). Predicting fashion sales using an ARIMA-SVM hybrid model. Expert Systems with Applications, 65, 112-120.

| Age Range | Age Group | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| < 25 | Gen Z | Early career/first disposable income |

| 26 – 41 | Millennials | Largest consumer base, established careers |

| 42 – 57 | Gen X | High purchasing power, brand loyalties |

| >58 | Baby Boomers | Established wealth, emphasis on comfort/fit |

| Metric | Score |

|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 0.8300 |

| Precision (Weighted) | 0.8307 |

| Recall (Weighted) | 0.8300 |

| F1-Score (Weighted) | 0.8000 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| high | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 3032 |

| low_medium | 0.83 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 903 |

| Accuracy | 0.83 | 3935 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).