1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is the major cause of infection-related deaths globally specially in HIV+ patient cohort (1). Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb.) is the causative pathogen of TB which is characterised by a complex, lipid-rich, hydrophobic cell envelope. TB is transmissible through M. tb.-containing aerosol droplets, which are propelled by active TB patients (2). The granulomatic lesion is the paradigm of pulmonary tuberculosis, which is an amorphous collection of macrophages and other immune cells and serves a cantonment of infection. Granuloma is capable of clearing drug sensitive pathogen by suppressing the progression to the active disease. However, multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogen persists and survives acidic environment of granuloma by blocking the phagosome-lysosome fusion and sabotaging host's immunogenic response. This pathological condition can remain dormant for decades, outwitting the immune response and persisting in a quiescent state (3) predisposing patient asymptomatic. During this period, the bacilli containing macrophages differentiate into foamy macrophages (3) where pathogen survives either opportunistically or passively. Depending upon pathogenesis, the granuloma may develop into necrotizing due to the necrotic lysis of the host immune cells, forming what is known as cheese-like necrosis (4) which becomes fatal for host (5) and favorable for pathogen. This is attributed to specialized architecture of Mycobacteria which tweak extensive fibrosis and enable them to survive them in extreme environment of host. There are four primary components that make up the M.tb. cell envelope. The cytosol is surrounded by the innermost, or cytoplasmic membrane which is mainly composed of proteins, phospholipids such as phosphatidic acid (PA), diphosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides (PIMs). The major backbone of PIMs is the phosphatidyl-myo-inositol moiety, which anchors the lipoglycans also known as cell envelope LAM and lipomannan (LM) in the plasma membrane. The periplasmic region is composed of peptidoglycan (PG) and arabinogalactan (AG), which together make up the arabinogalactan protein (AGP) complex, are found outside of the cell membrane. The outer membrane, also known as a "myco-membrane," is made up of a unique layer of mycolic acids (6). Heterogeneous lipoglycan is one of the main components of mycobacteria's LAM. A phosphatidylinositol anchor is composed of mannan backbone, and several arabinan antennae extending from the mannan. Although this, remain conserved across majority of mycobacterial spp however Mycobacterium chelonae display AraLAM without arabinan, whereas Mycobacterium smegmatis display PI-LAM phosphoinositol capping (7). A mannosyl phosphatidyl-inositol (MPI) lipid moiety with residues of palmitic, tuberculostearic, and stearic acids is covalently bonded to the mannan core of LAM. M. tb. LAM contains a large amount of mannose-capped arabinomannan (ManAM), which is structurally similar to the ManAM portion of LAM (8). The biological activity of the two LAM variants is significantly influenced by their distinct terminal configurations. This more or less dictates the interaction of LAM with host cells during various biotic stresses. LAM and its precursors, LM, PIMs have strong immunomodulatory effects on immune cells. To impair cellular immune responses, ManLAM suppress the synthesis of interleukin IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), restrict TLR (Toll like receptor)-mediated activation, stimulate IL-10 release, and prevent macrophage death. On the other hand, PI-LAM may trigger TLR-2 induced autophagy and increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, PI-LAM has no such effects, while ManLAM inhibits the formation of LC3-II in phagosomes. Thus, variations in innate immunity are caused by LAM diversity (9).

Figure 1.

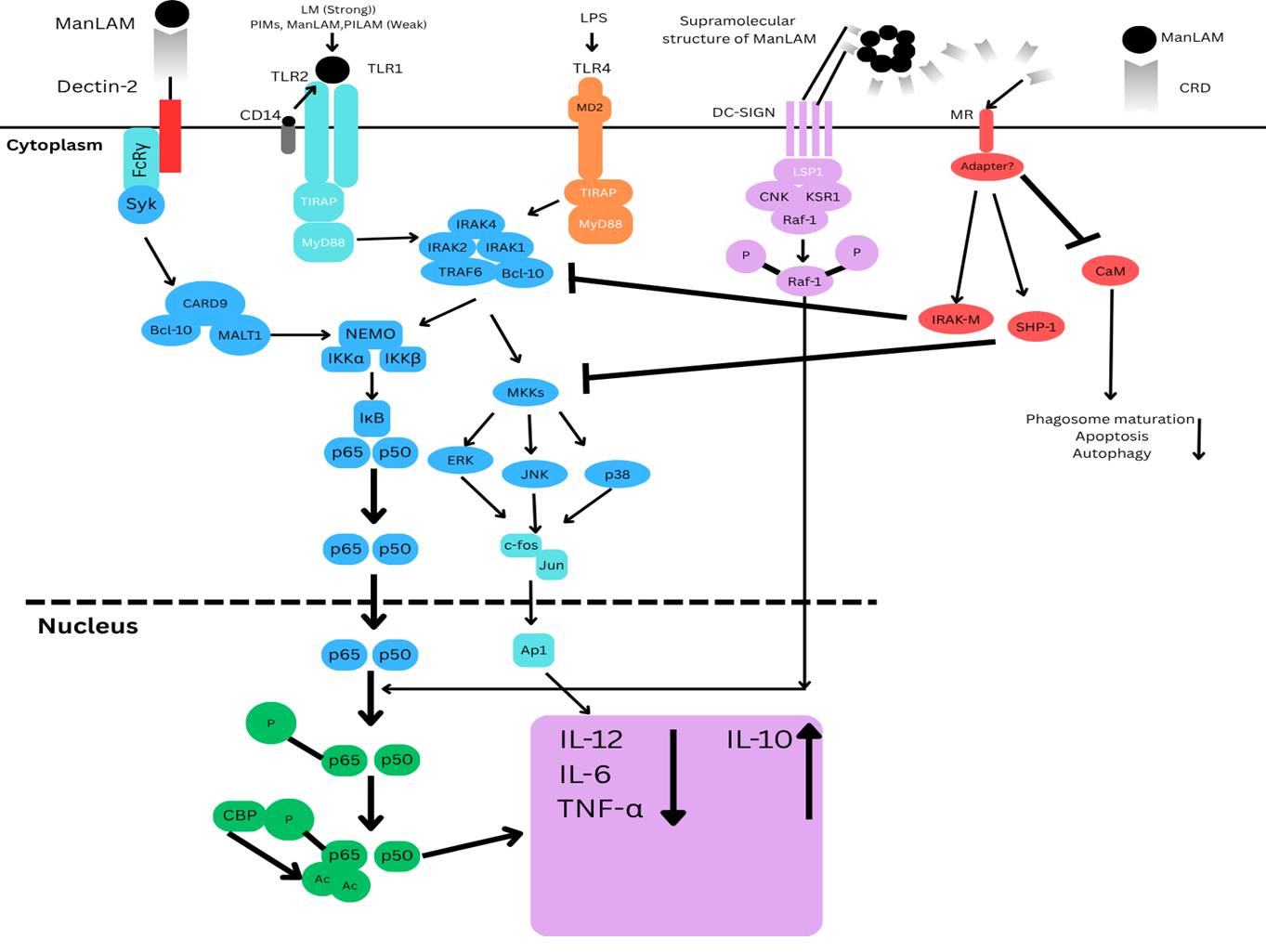

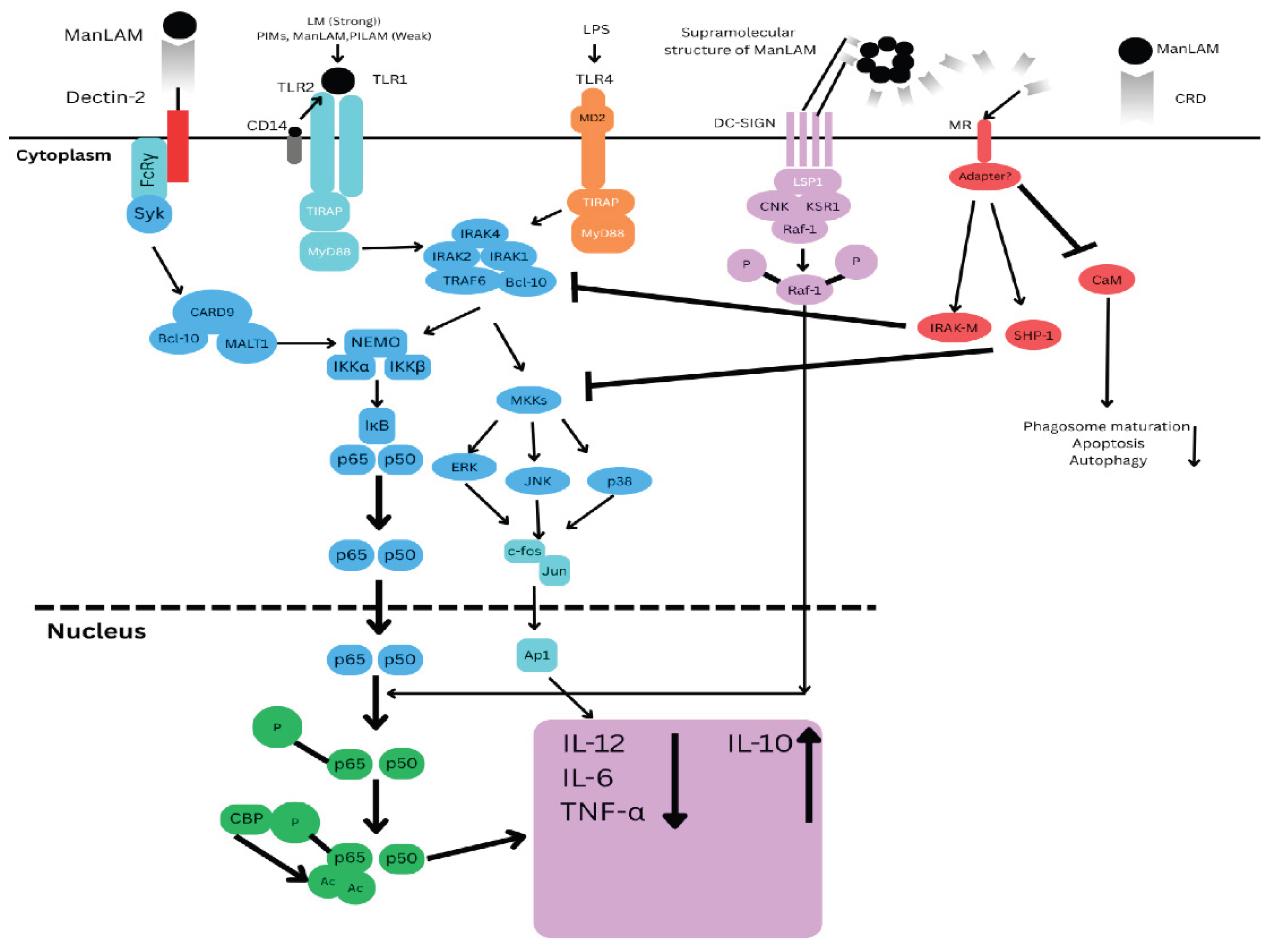

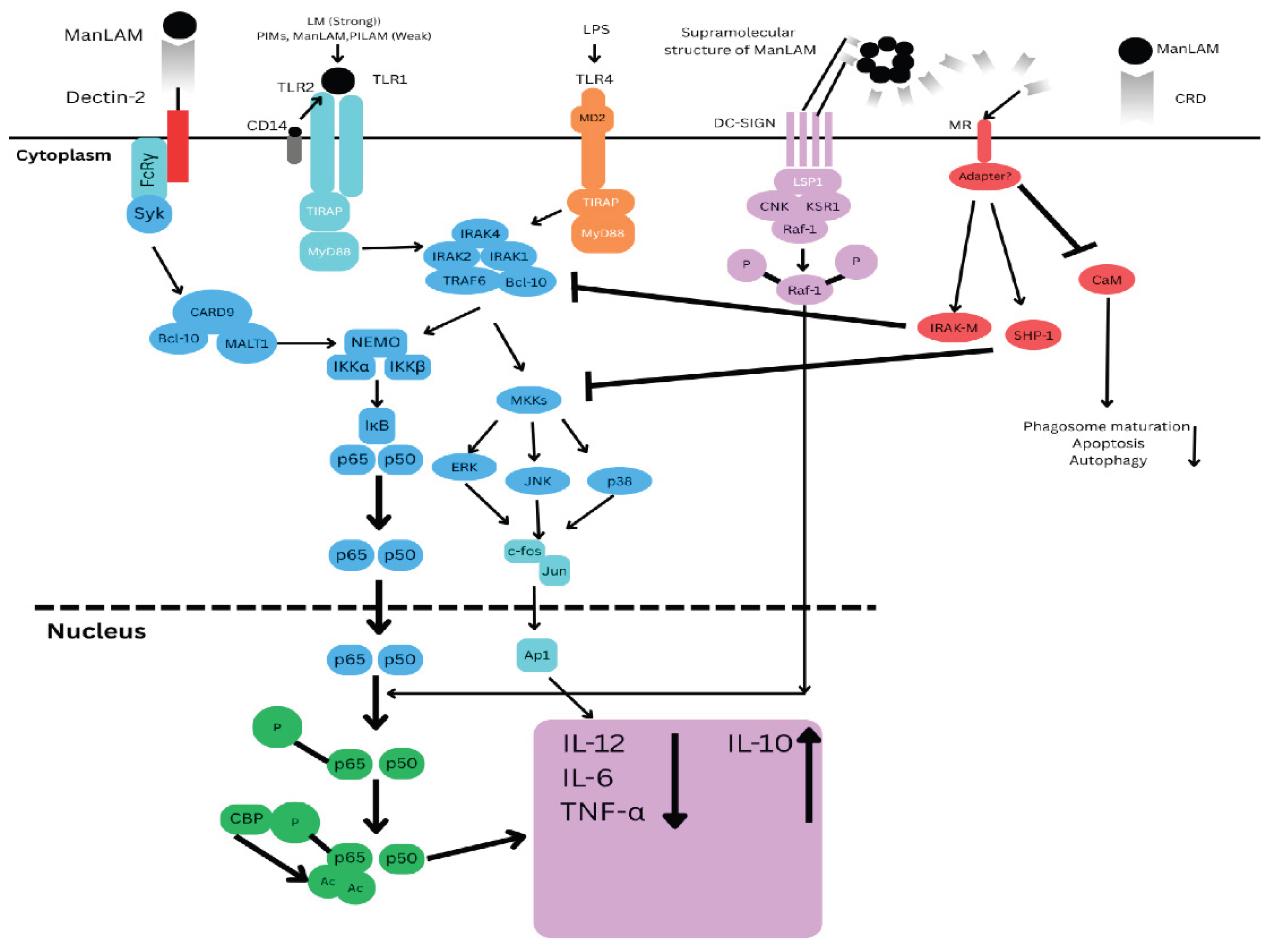

ManLAM and its metabolic precursors, LM and PIMs, initiate cell signalling pathways. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are produced in DCs (Dendritic cells) and macrophages by LM and, to a much lesser extent, PIMs, PILAM, and ManLAM via the Tri- or tetra-acylated MPI (Mannose phosphate isomerase) anchor recognition by the TLR2/TLR1 heterodimer. Through the binding of mannose caps to Dectin-2, ManLAM causes bone marrow-derived DCs to release cytokines. However, it also prevents the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-6 and promotes IL-10 by DC-SIGN ligation in LPS-stimulated human DCs. In the signalling route, Raf-1 activation causes the p65 subunit of NF-κB to become phosphorylated at Ser276, which in turn causes two histone acetyltransferases to acetylate p65. After being initially focused on the transcription of genes that code for pro-inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB translocation in response to TLR activation shifts its focus to anti-inflammatory promoter targets, which lowers these cytokines to the advantage of IL-10. By directly affecting the TLR4 signalling cascade through the enhanced expression of IRAK-M, which can compete with IRAK1 for binding to TRAF6 and hence decrease NF-κB activation, ManLAM also suppresses IL-12 and TNF-α in macrophages independently of IL-10 production. Additionally, ManLAM encourages the tyrosine dephosphorylation of several proteins, including MAPK; this effect may be attributed to a rise in tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 activity. Despite lacking a signalling motif in its cytoplasmic domain, MR is likely to facilitate ManLAM immunosuppressive functions in macrophages. This begs the intriguing question of whether it binds with adaptor molecules to transduce signals.

Figure 1.

ManLAM and its metabolic precursors, LM and PIMs, initiate cell signalling pathways. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are produced in DCs (Dendritic cells) and macrophages by LM and, to a much lesser extent, PIMs, PILAM, and ManLAM via the Tri- or tetra-acylated MPI (Mannose phosphate isomerase) anchor recognition by the TLR2/TLR1 heterodimer. Through the binding of mannose caps to Dectin-2, ManLAM causes bone marrow-derived DCs to release cytokines. However, it also prevents the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-6 and promotes IL-10 by DC-SIGN ligation in LPS-stimulated human DCs. In the signalling route, Raf-1 activation causes the p65 subunit of NF-κB to become phosphorylated at Ser276, which in turn causes two histone acetyltransferases to acetylate p65. After being initially focused on the transcription of genes that code for pro-inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB translocation in response to TLR activation shifts its focus to anti-inflammatory promoter targets, which lowers these cytokines to the advantage of IL-10. By directly affecting the TLR4 signalling cascade through the enhanced expression of IRAK-M, which can compete with IRAK1 for binding to TRAF6 and hence decrease NF-κB activation, ManLAM also suppresses IL-12 and TNF-α in macrophages independently of IL-10 production. Additionally, ManLAM encourages the tyrosine dephosphorylation of several proteins, including MAPK; this effect may be attributed to a rise in tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 activity. Despite lacking a signalling motif in its cytoplasmic domain, MR is likely to facilitate ManLAM immunosuppressive functions in macrophages. This begs the intriguing question of whether it binds with adaptor molecules to transduce signals.

2. LAM and Antimicrobial Response: Tug of War

The dense cell envelope, with its enrichment by lipoarabinomannan and phenolic glycolipid I, contribute to the intrinsic resistance to ROS which are important for both activation of phagocytes and killing of pathogen. ManLAM inhibits phagosome maturation by blocking Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII (Calcium ion/Calmodulin/Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II) signaling pathway responsible for PI3P (Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate) generation by type III PI3Kinase hVPS34 (human Vaculor Protein Sorthing 34). ManLAM is also able to block phagosome maturation by interacting with mannose receptor and interfering with membrane microdomains, rafts, but the connection with Ca2+/CaM signaling has not been explored. PIMs, ManLAM precursor, disrupt phagosome maturation by activating phagosome and early endosomes fusion. M. tb. inhibit the translocation of Rab14 to phagosome and inhibit early endosome fusion and maturation. It is still to be determined if PIMs enhances early endosome fusion via recruitment of Rab14 (10). ManLAM, being as strong immune modifier, contribute to the enhancement of TB prevention, diagnosis and treatment interventions. Following M. tb. infection, LAM is able to modulate the innate immunity of phagocytes, for example, alveolar epithelial cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. The innate immune reactions against mycobacteria are largely engaged in inflammatory factors secretion, phagocytosis, autophagy, and bactericidal activity. LAM is recognized via mannose receptor (MR), dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), and TLRs. SR-A (Scavenger Receptor Class A) has been shown to modulate TLRs signaling in host during infection. LAM has diversity receptor affinity and heterogeneous immunogenicity as a result of variations in the structures of LAM (11). Molecular mechanism investigation shows that ManLAM-TLR2 interaction causes IL-10 production by B cells through the TLR2/MyD88/PI3K (Phosphoinositide 3-kinase) AP-1 (Activator Protein-1) and NEMOK63 (NF- κB Essential Modulator) ubiquitination NF-κB pathways, and enhanced USP40 (Ubiquitin Specific Protease 40). ManLAM-induced B10 cells suppress Th1 responses, enhance Th2 polarization, and do not affect Th17 cells. ManLAM-induced B10 cells enhance susceptibility to M. tb. infection in mice. This assist in comprehending the interaction of B cells with M. tb. ManLAM and emphasize the ManLAM-mediated B cells' immunomodulatory roles (12). Patients having high pathogen burden, or with advanced TB infection (a condition similar to cachexia), show higher concentration of LAM (13) in their urine. Urine based LAM testing was most beneficial for TB patients who did not have respiratory symptoms or produce sputum (14). Lateral flow urine LAM testing further provided a significant new avenues for early detection of TB. The sickest patients living with HIV (PLHIV) responds well to Alere Determine TB LAM Ag (also known as "LF-LAM"), which is currently approved. Newer LAM tests, including Fujifilm SILVAMP TB LAM (also known as "SILVAMP-LAM"), demonstrate increased sensitivity, even in HIV-negative individuals, indicating that technology is still advancing. This indicates the potential epidemiological implication of LAM based testing on TB incidence and mortality (15). Urine LAM testing might be a convenient way to track how well TB patients receiving treatment in HIV-endemic, resource-constrained environments are responding to anti-TB medication. Among HIV-positive individuals who are at increased risk of death, rapid urine LAM test is prudent for those who need careful monitoring. Nevertheless, a bigger clinical trial is necessary to ascertain if repeatedly positive urine LAM is linked to drug-resistant TB, poor medication adherence, or the lack of a treatment response, given the many attractive features of urine LAM testing and its potential application at the clinical point-of-care (16).

3. LAM as Yardstick of Mycobacterial Survival in Hostile Environment

LAM is a "yardstick of Mycobacteria" since it is a specific, quantifiable, and biologically significant biomarker that indicates bacteria identity, burden, virulence, treatment response, and prognosis. It facilitates microbiological detection and help in predicting immunological function, thus has a central molecule in TB pathogenesis. Systematic review and meta-analysis have demonstrated that HIV-TB patients with detectable LAM are at higher risk of mortality than TB patients with undetectable LAM. LAM is an independent predictor of mortality and thus is not an epiphenomenon of individuals with high immunosuppression. Detection of LAM seems to be a sensible strategy to reveal patients with high mortality risk and to identify probable targets for adjunctive treatments to prevent mortality from TB in the next 20 years (17). ManLAM is continuously secreted from metabolically active or degrading bacteria cells hence, this can be correlative to the viable bacterial infection (18). Sputum LAM concentration correlates with bacterial load in sputum as quantified by both solid culture and liquid culture and mirrors changes in bacterial load after pharmacological effect. The LAM titer changes in sputum after therapy which suggests that this can be used as a prognostic marker (19) in TB patients. FujiLAM (Fujifilm LAM) served as a supplement point-of-care for rapid TB diagnosis in patients with presumptive TB presenting at outpatient health care thus could be of colossal impact on patient outcome, if used as a rule-in test in conjunction with initiation of treatment (20). Convenient and quick Alere LAM warrants top priority to guide TB treatment among HIV+ patients who are incapable of producing sputum which complicate TB diagnosis, whereas almost all subjects are capable of producing urine (21). In conclusion, this perspective note emphasizes that LAM can serve as immunopathological markers in MDR-TB, act as both prognostic marker and target for managing latent or MDR TB diseases. We believe that LAM based approach may constitute future host-directed therapies against TB.

Acknowledgments

This was supported by extramural grants from Indian Council of Medical Research ( Nr - 5/8/85/46/Adhoc/2022/ECD-1) to Hridayesh Prakash.

References

- Kawasaki, M. et al. (2019) Lipoarabinomannan in sputum to detect bacterial load and treatment response in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: Analytic validation and evaluation in two cohorts. PLOS Medicine. 16 (4), 1-20.

- 2. Alsayed, S.S.R. and Gunosewoyo, H. (2023) Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Current Treatment Regimens and New Drug Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24, 1-23.

- Luies, L. and Preez, D. I. (2020) The Echo of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Mechanisms of Clinical Symptoms and Other Disease-Induced Systemic Complications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33(4), 1-19.

- Huszár, S. et al. (2020) The quest for the holy grail: New antitubercular chemical entities, targets and strategies. Drug Discov. Today. 25 (4), 772–780.

- Chai, Q. et al. (2018) Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An Adaptable Pathogen Associated With Multiple Human Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 1-15.

- Torrelles, B.J. and Chatterjee, D. (2023) Collected Thoughts on Mycobacterial Lipoarabinomannan, a Cell Envelope Lipoglycan. Pathogens.12, 1-15.

- De, P. et al. (2021) Structural implications of lipoarabinomannan glycans from global clinical isolates in diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Biol. Chem. 295 (5), 1-16.

- Neves-Correia, M. et al. (2019) Lipoarabinomannan in Active and Passive Protection against Tuberculosis. Frontiers in Immunology. 10, 1-13.

- Liu, H. et al. (2022) Structural Variability of Lipoarabinomannan Modulates Innate Immune Responses within Infected Alveolar Epithelial Cells. Cells.11, 1-21.

- Vergne, I. et al. (2015) Manipulation of the endocytic pathway and phagocyte functions by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 4, 1-9.

- Liu, H. et al. (2022) Structural Variability of Lipoarabinomannan Modulates Innate Immune Responses within Infected Alveolar Epithelial Cells. Cells. 11(3), 1-21.

- Yuan, C. et al. (2019) Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mannose-Capped Lipoarabinomannan Induces IL-10-Producing B Cells and Hinders CD4+Th1 Immunity. iScience. 11, 13-30.

- Paris, L. et al. (2017) Urine lipoarabinomannan glycan in HIV-negative patients with pulmonary tuberculosis correlates with disease severity. Science Translational Medicine. 9, 1-11.

- Lawn, D.S. et al. (2017) Diagnostic accuracy, incremental yield and prognostic value of Determine TB-LAM for routine diagnostic testing for tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients requiring acute hospital admission in South Africa: a prospective. BMC Medicine. 15 (67), 1-16.

- Ricks, S. et al. (2020) The potential impact of urine-LAM diagnostics on tuberculosis incidence and mortality: A modelling analysis. PLOS Medicine. 17 (12), 1-20.

- Drain, P.K. et al. (2015) Urine lipoarabinomannan to monitor antituberculosis therapy response and predict mortality in an HIV-endemic region: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 5(4), 1-8.

- Wright, A.G. et al. (2016) Detection of lipoarabinomannan (LAM) in urine is an independent predictor of mortality risk in patients receiving treatment for HIV-associated tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 14(53):1-11.

- Zhou, Y. et al. (2021) Aptamer Detection of Mycobaterium tuberculosis Mannose-Capped Lipoarabinomannan in Lesion Tissues for Tuberculosis Diagnosis. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 11, 1-12.

- Jones, A. et al. (2022) Sputum lipoarabinomannan (LAM) as a biomarker to determine sputum mycobacterial load: exploratory and model-based analyses of integrated data from four cohorts. BMC Infectious Diseases. 22, 1-18.

- Magni, R. et al. (202) Lipoarabinomannan antigenic epitope differences in tuberculosis disease subtypes. Scientific Reports. 10, 1-12.

- Broger, T. et al. (2023) Diagnostic yield of urine lipoarabinomannan and sputum tuberculosis tests in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Glob Health. 11, 903-916.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).