Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Table of Content

1. Introduction

3. Standard Polymer Micelles

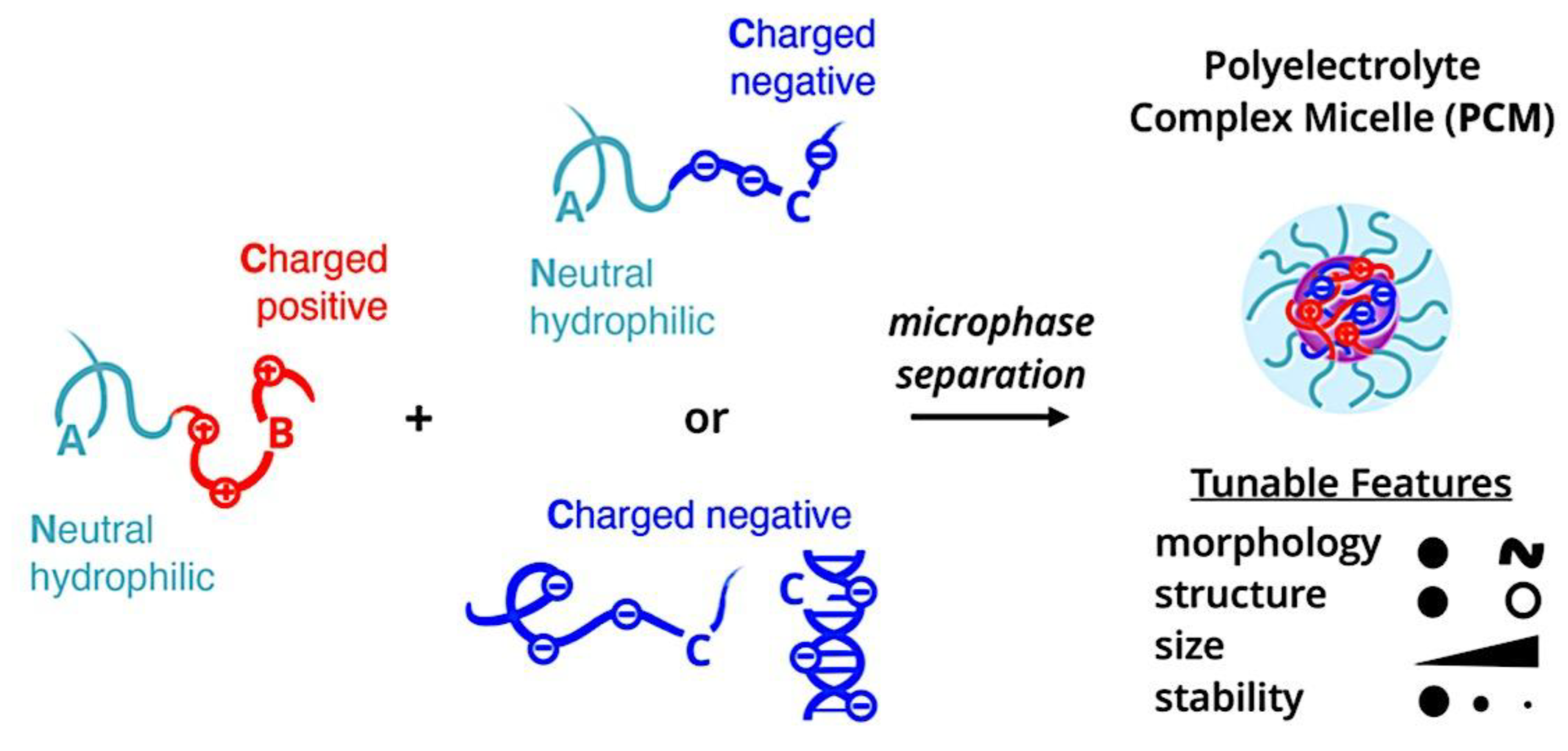

4. An Alternative Kind of Polymer Micelle Nanoparticles

5. Polymer Micelle Nanoparticles that Are Acid-Cleavable and pH Sensitive

6. Micelle Nanoparticles of Cross-Linked Polymers

7. Innovative Approaches to Polymer Micelle Nanotechnology

8. C3M Structure-Property Relationships

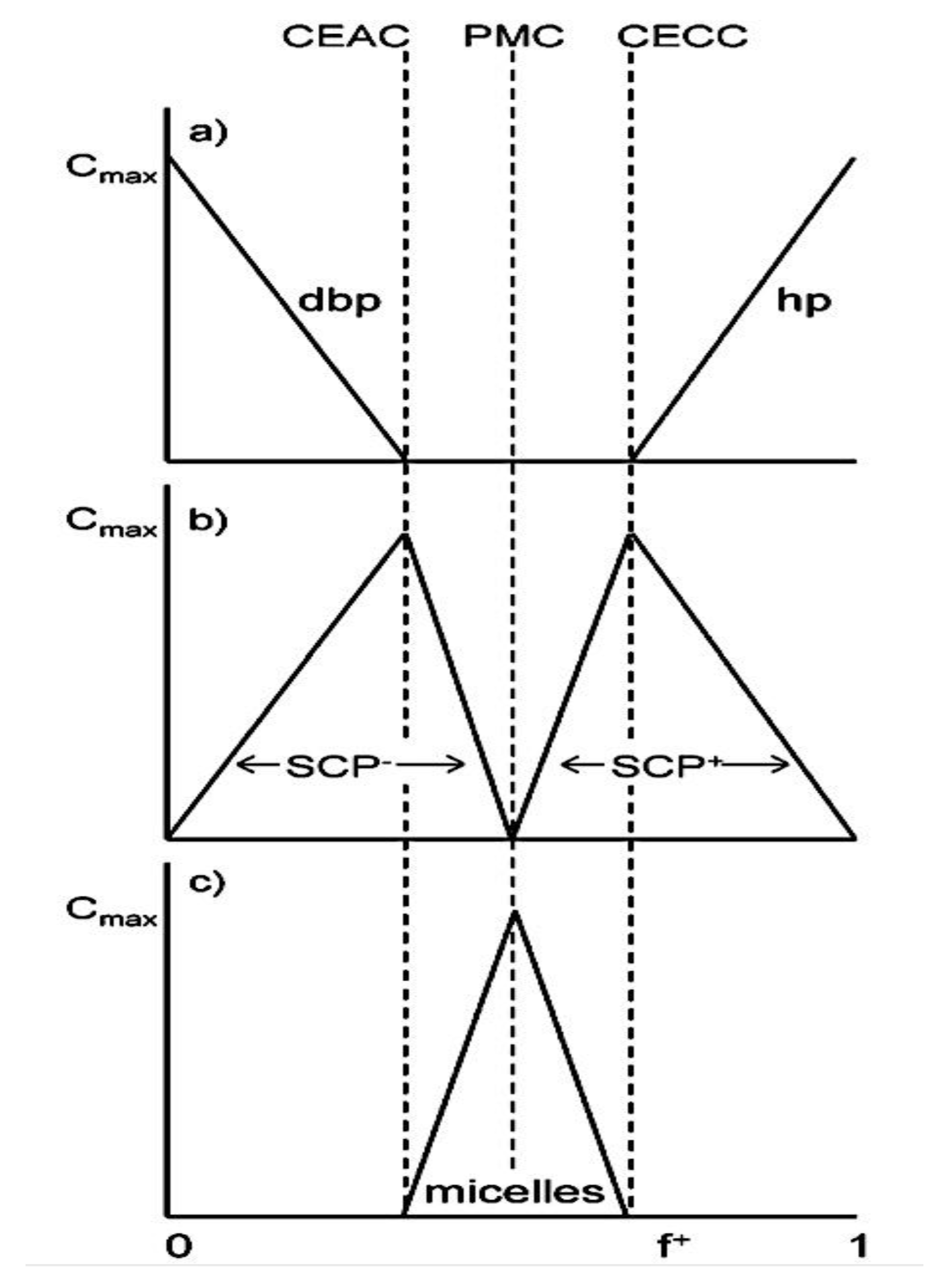

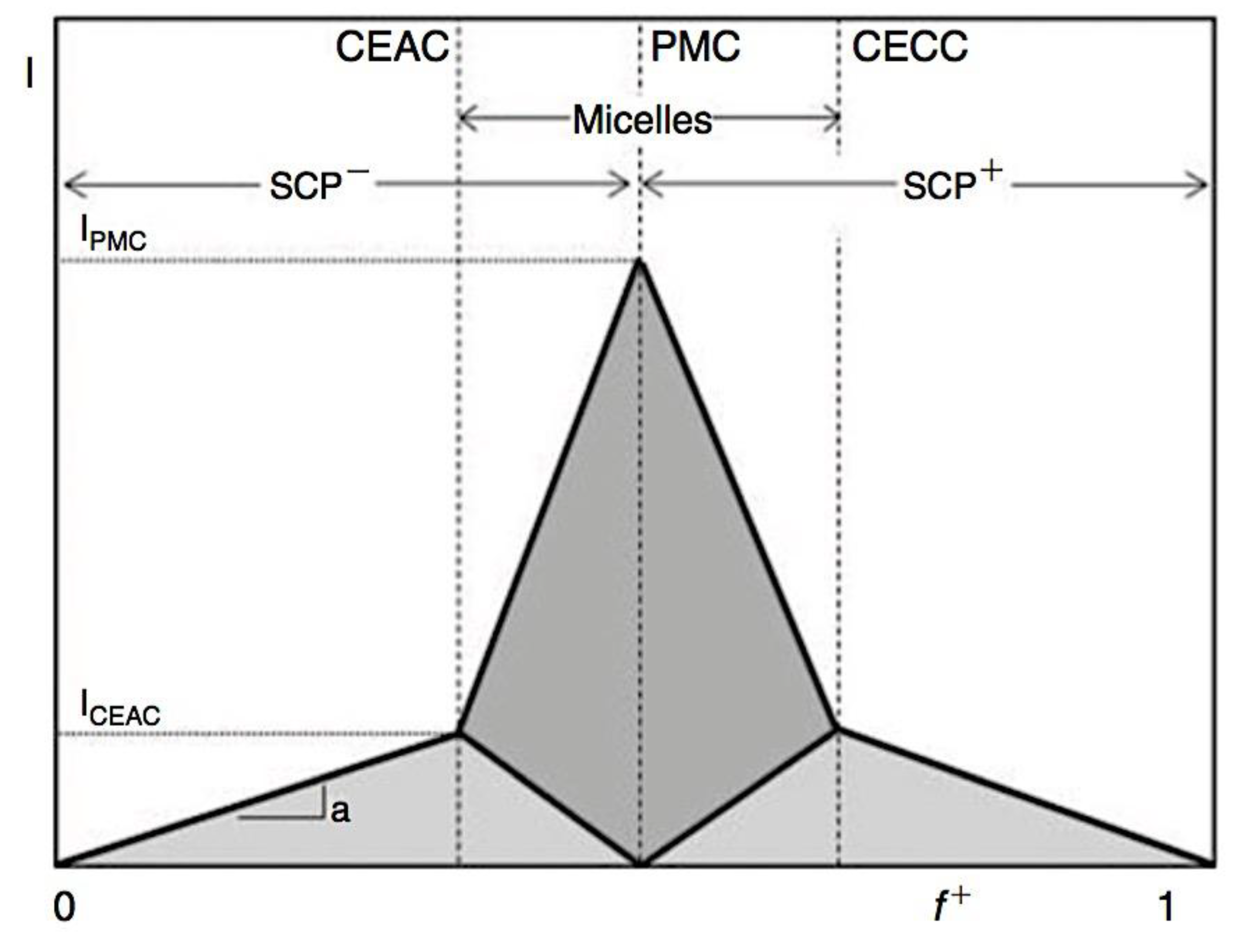

8.1. Steady-State Properties

8.2. Morphological Transitions

8.3. Sturdy, Long-Lasting, and Stimuli-Sensitive Pharmaceutical Micelles

8.3.1. Longevity

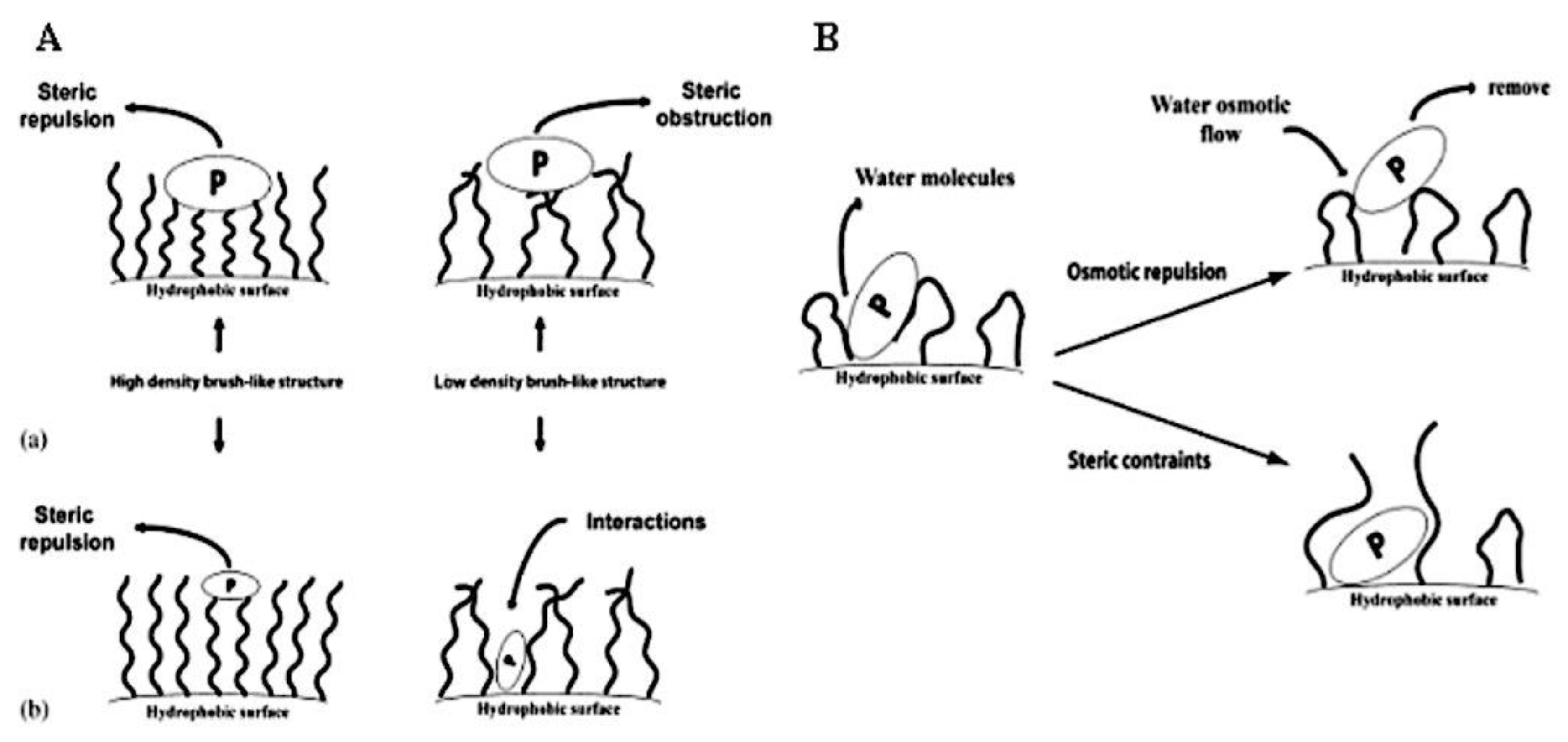

8.3.1.1. Steric Stabilization

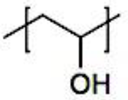

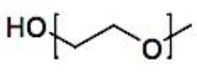

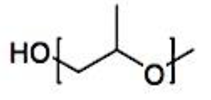

- 8.3.1.1.1. Poly(ethylene glycol)

- 8.3.1.1.2. Substitute Coatings

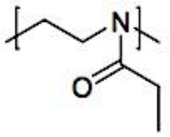

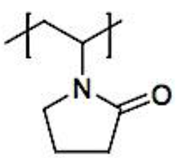

- 8.3.1.1.2.1. Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)

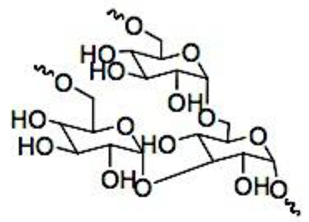

- 8.3.1.1.2.2. Polysaccharides

- 8.3.1.1.2.3. Additional Hydrophilic Blocks

8.3.1.2. The Size of Micellar Particles

8.3.1.3. Additional Methods to Enhance Circulation Times

8.3.1.4. Longevity of Polymeric Micelles with Active Targeting

8.3.2. Stability of Micellar Matter

8.3.2.1. Lowering the CMC

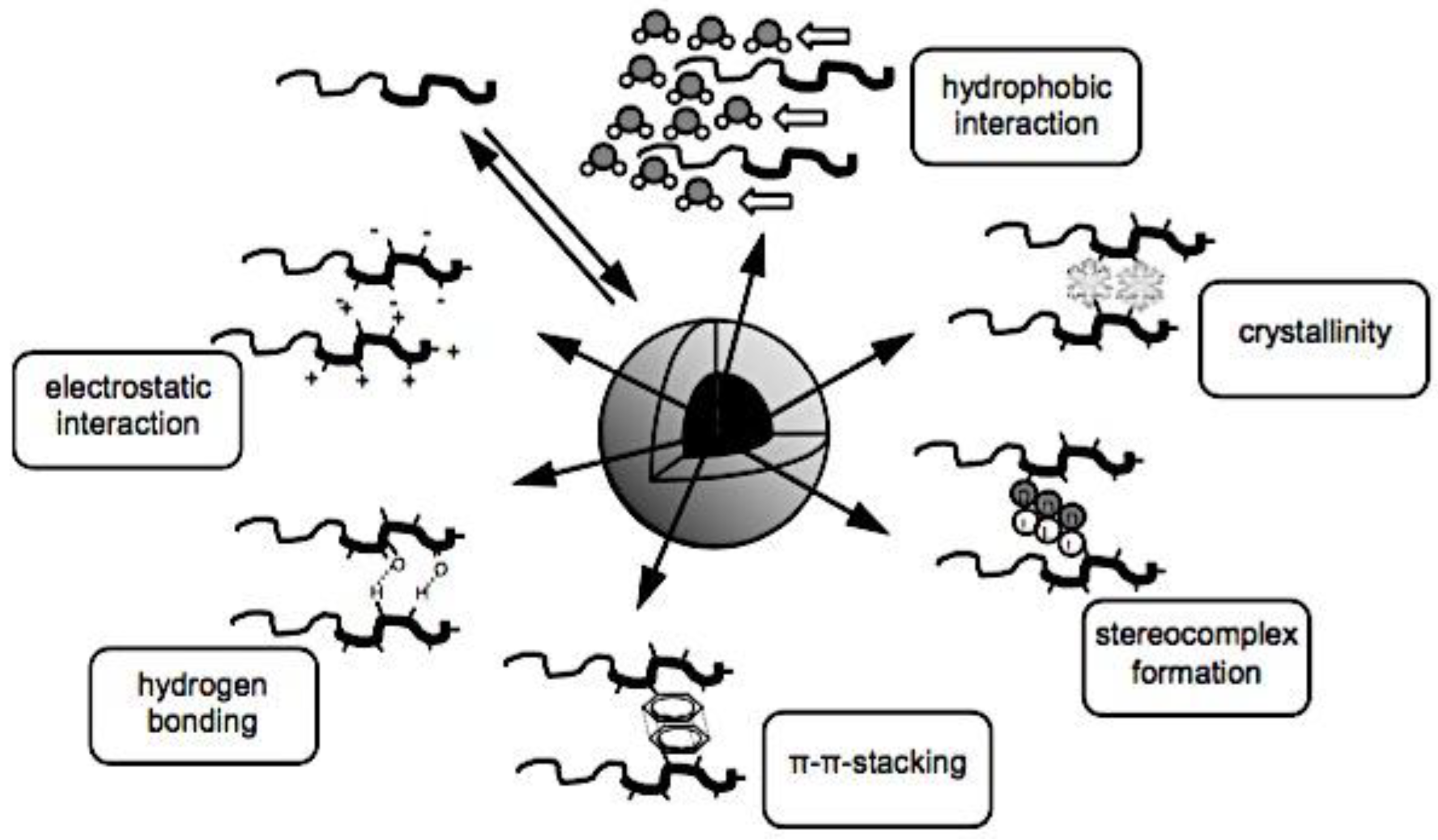

8.3.2.2. Physical Interactions

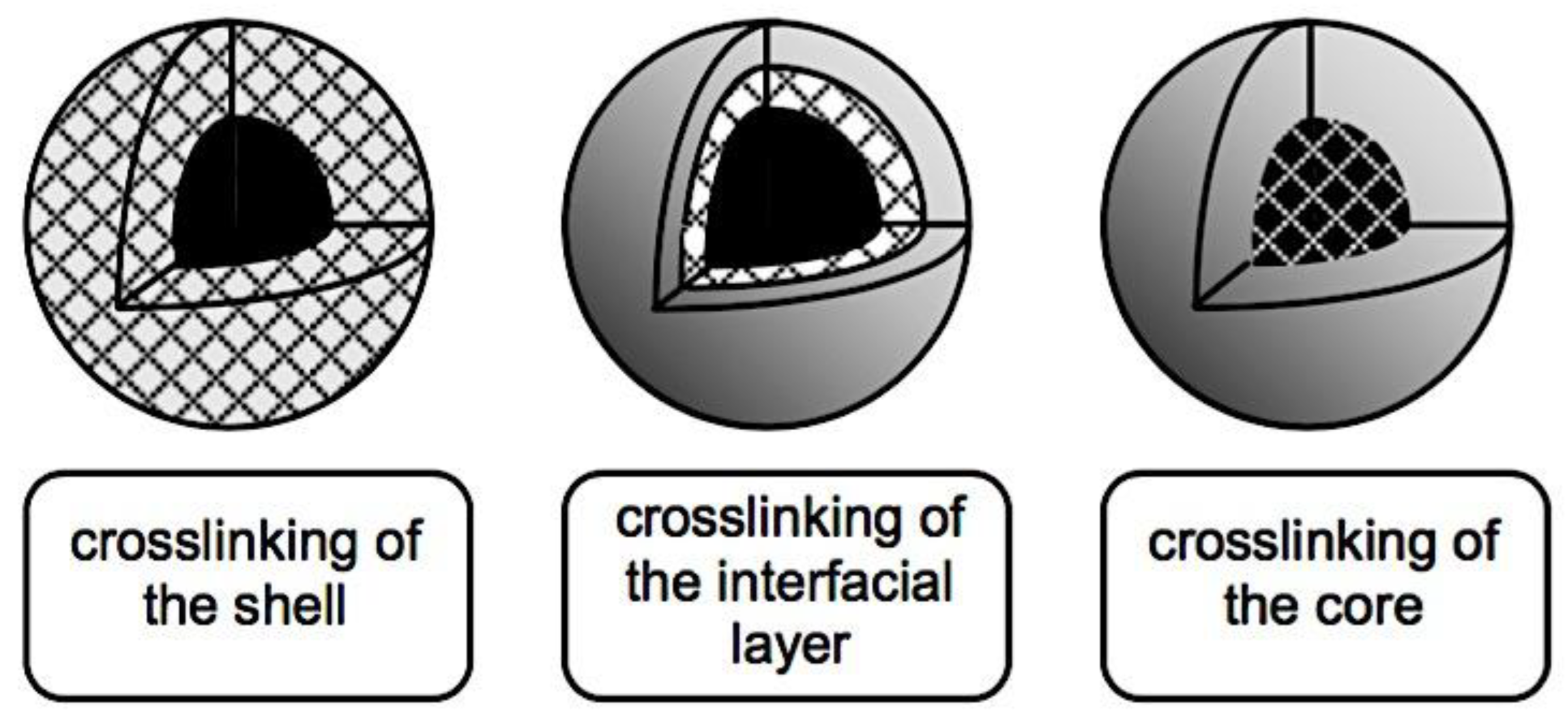

8.3.2.3. Crosslinking of Covalent Bonds

- 8.3.2.3.1. Crosslinking of Shells

- 8.3.2.3.2. The Crosslinking of Interfaces

- 8.3.2.3.3. Crosslinking at the Core

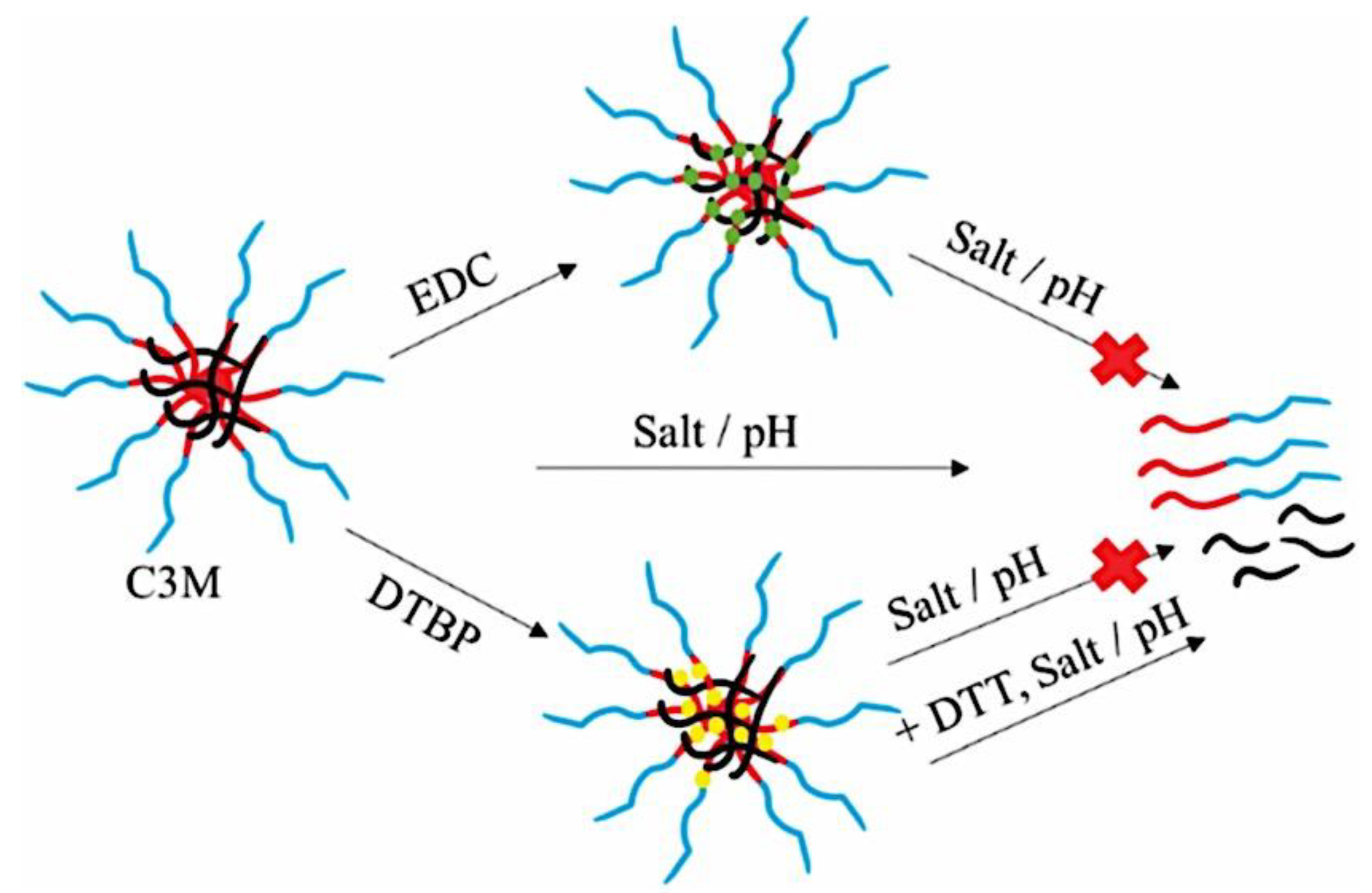

- 8.3.2.3.4. Cleavable Crosslinks

- 8.3.2.3.5. Crosslinking’s Effects on Drug Release and Loading

8.3.2.4. Drug Compatibility with Micellar Core

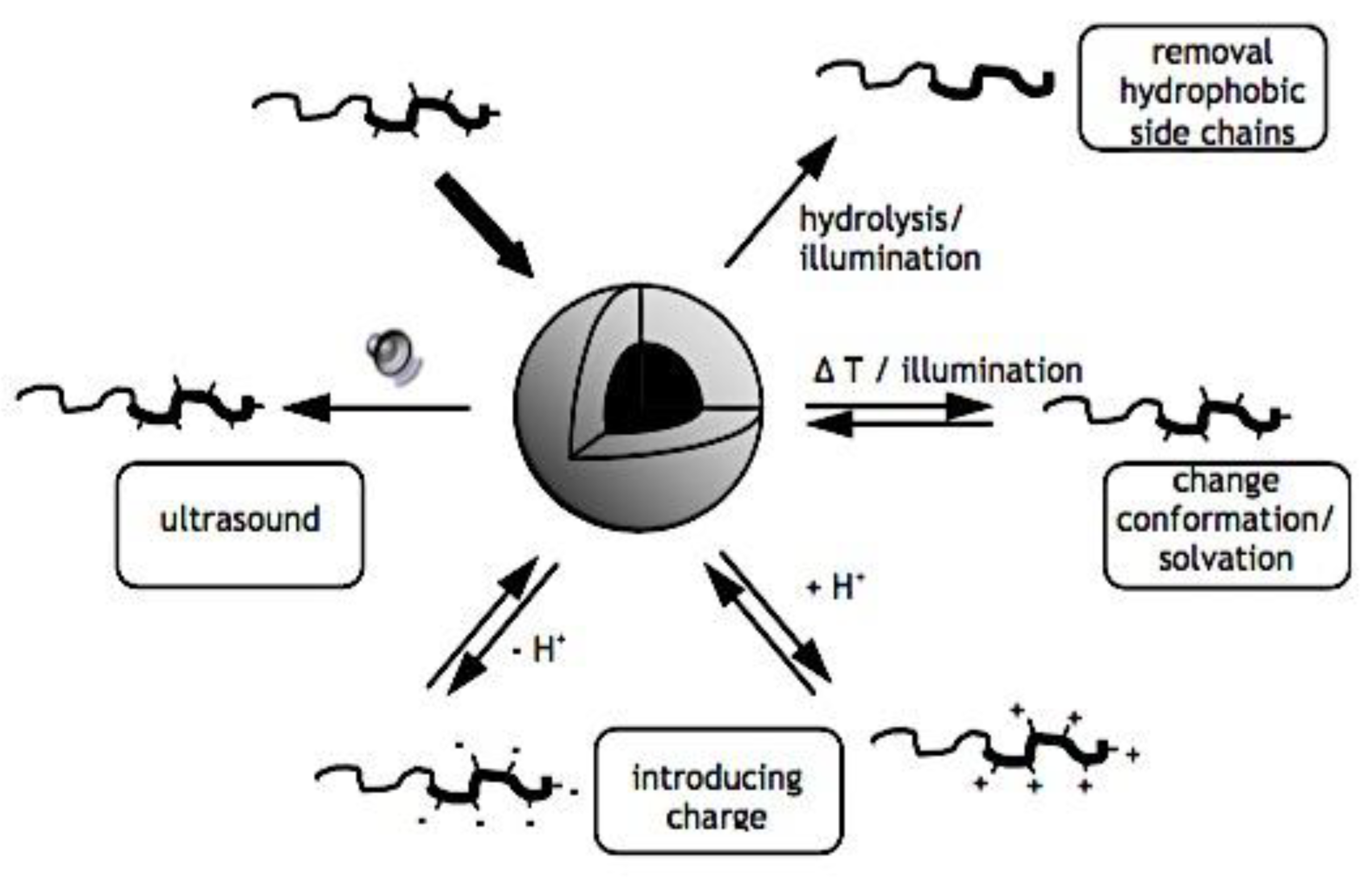

8.3.3. Sensitivity to Stimuli

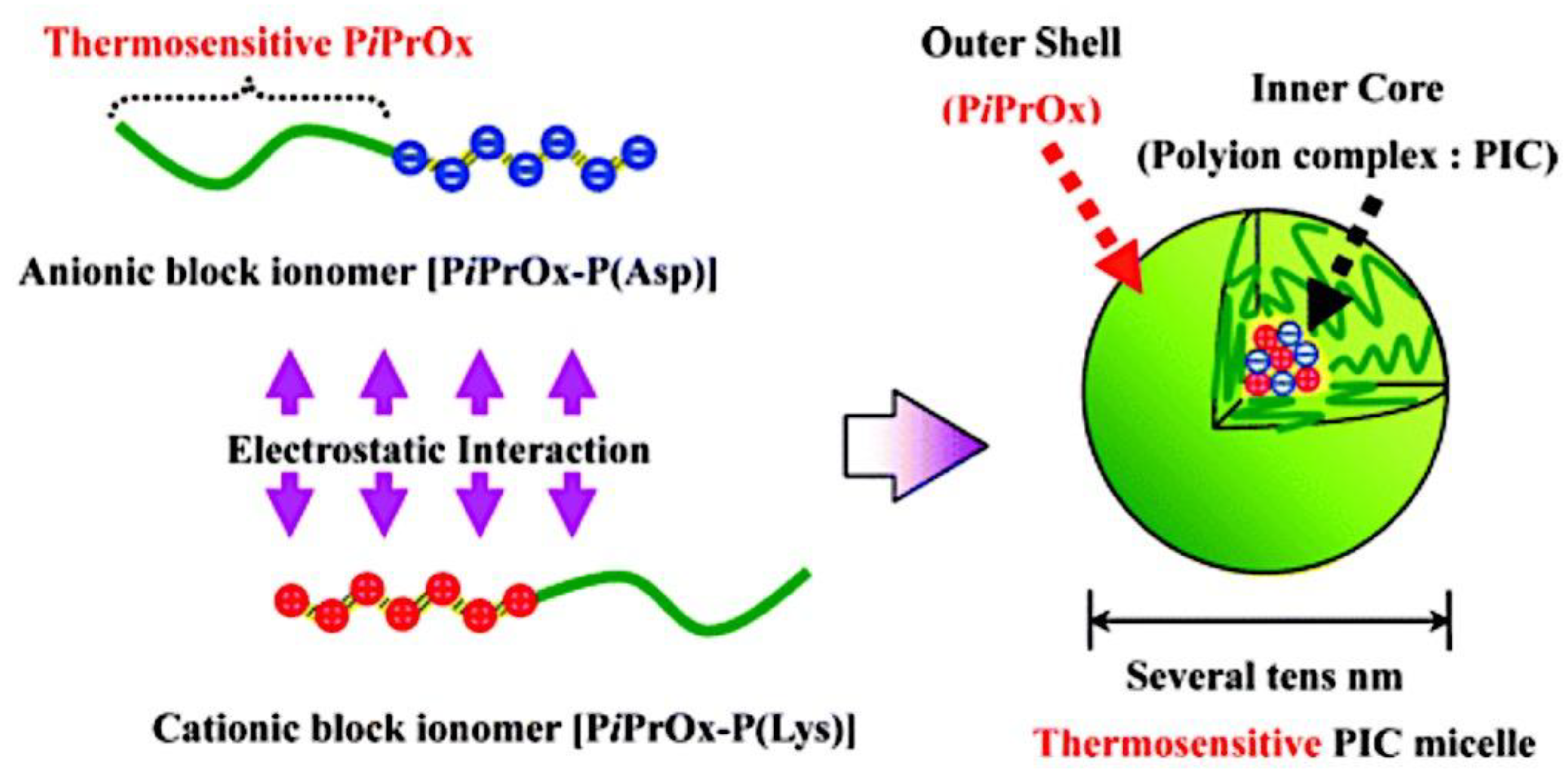

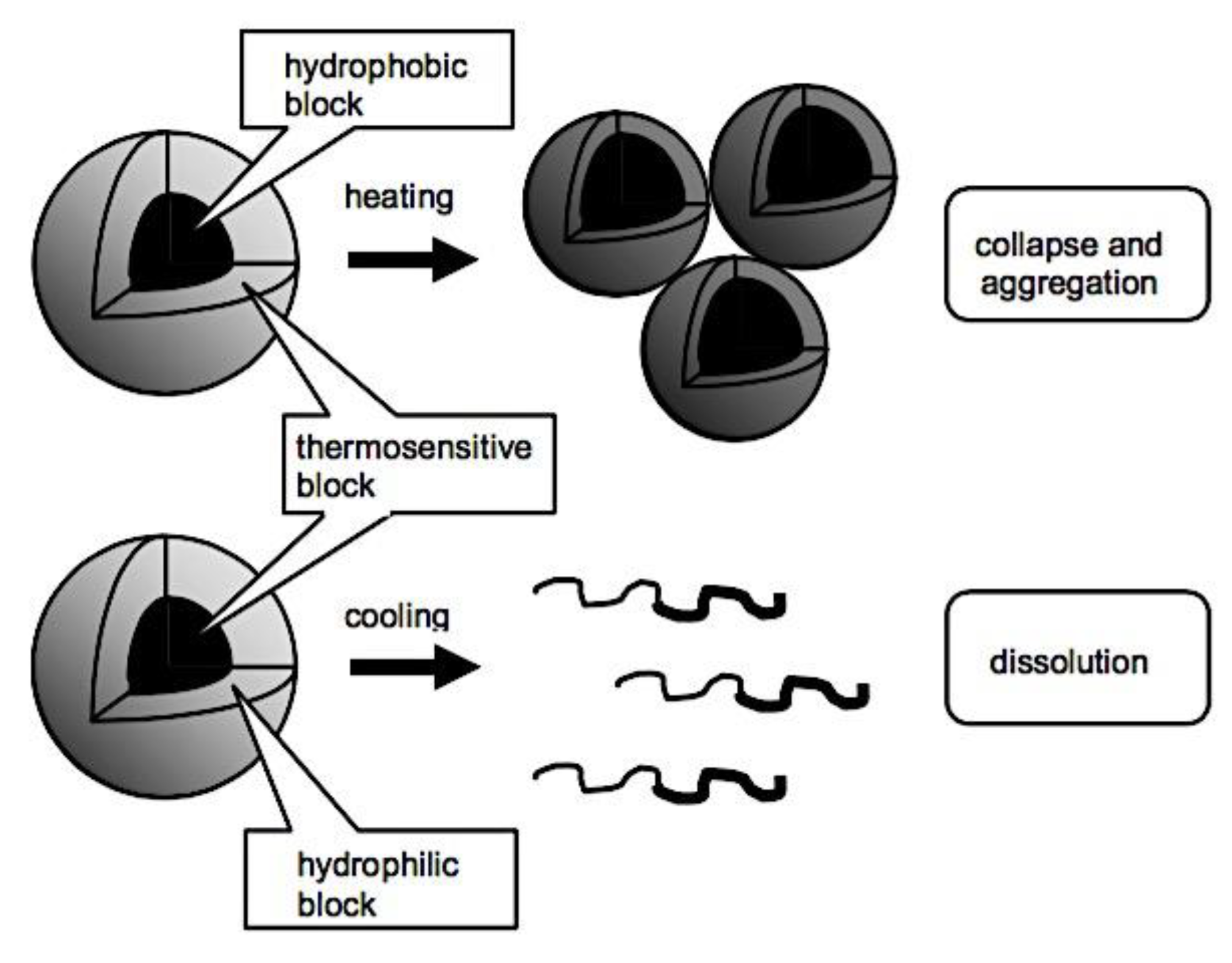

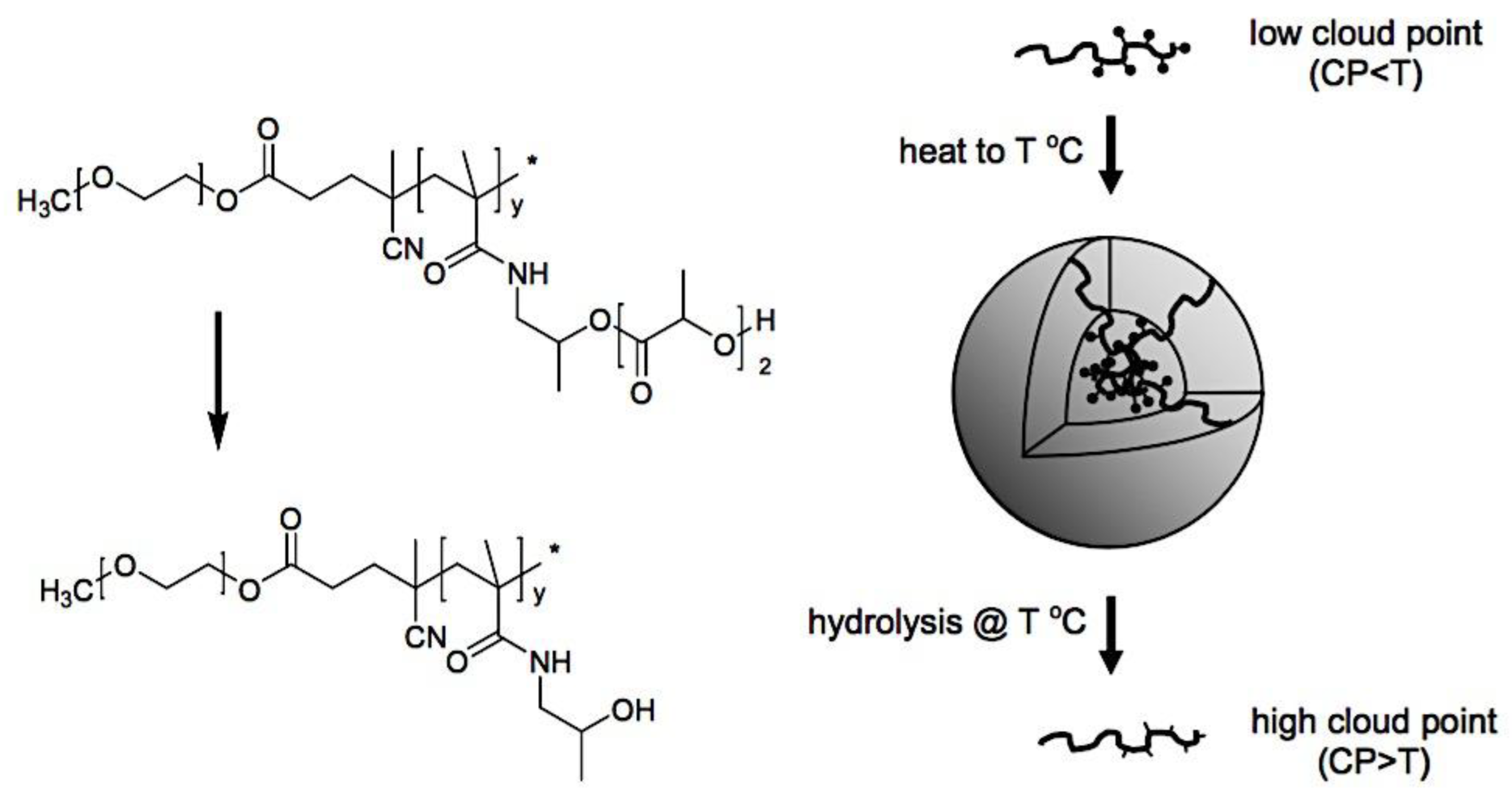

8.3.3.1. Polymeric Micelles with Thermosensitivity

8.3.3.2. Polymeric Micelles with pH-Sensitivity

8.3.3.3. Micellar Disintegration Induced by Chemical Hydrolysis

- 8.3.3.3.1. Chemical Hydrolysis of the Polymeric Framework

- 8.3.3.3.2. Cleavable Side Chains

- 8.3.3.3.3. Breakdown of Polymer-Drug Complexes

8.4.3.3. Polymeric Micelle Destabilization Induced by Enzymes

8.5.3.3. Polymeric Micelles Susceptible to Oxidation and Reduction

8.6.3.3. Micellar Deformation Caused by Light

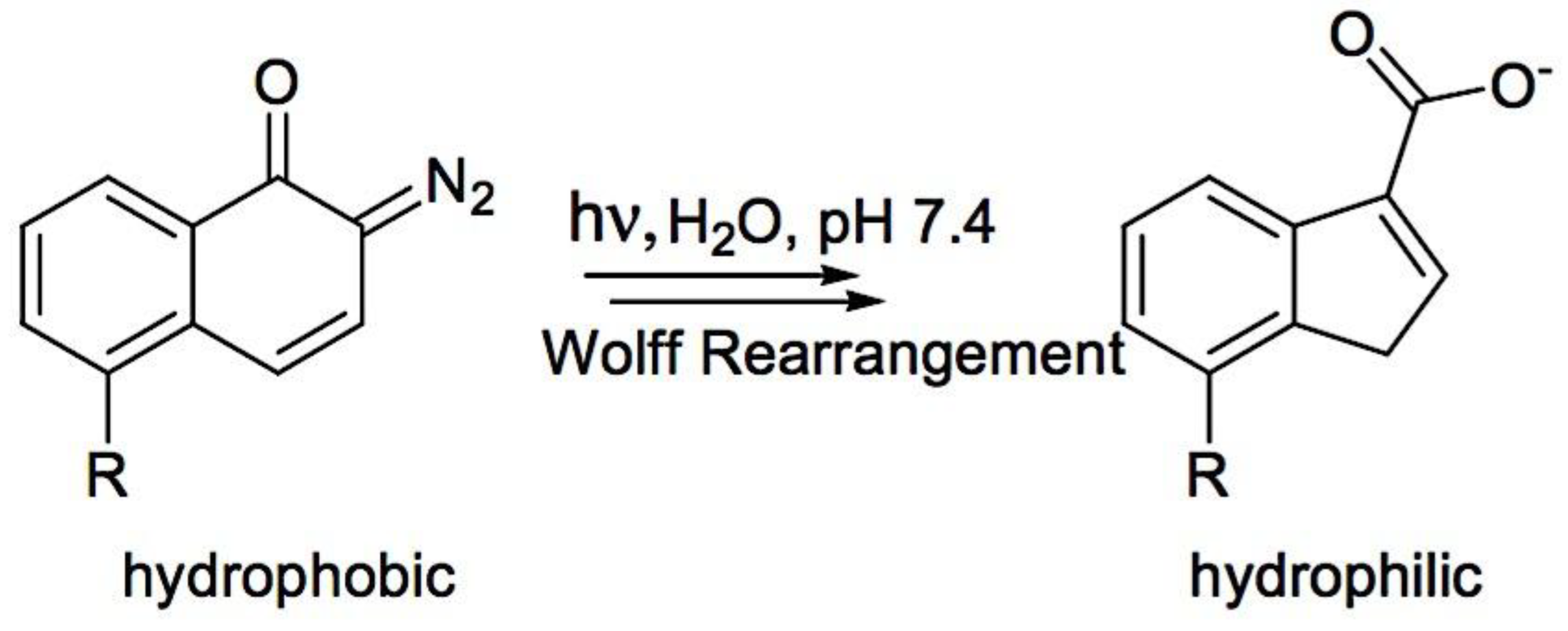

- 8.6.3.3.1. Irreversible Reactions that Occur on Illumination (Photolysis)

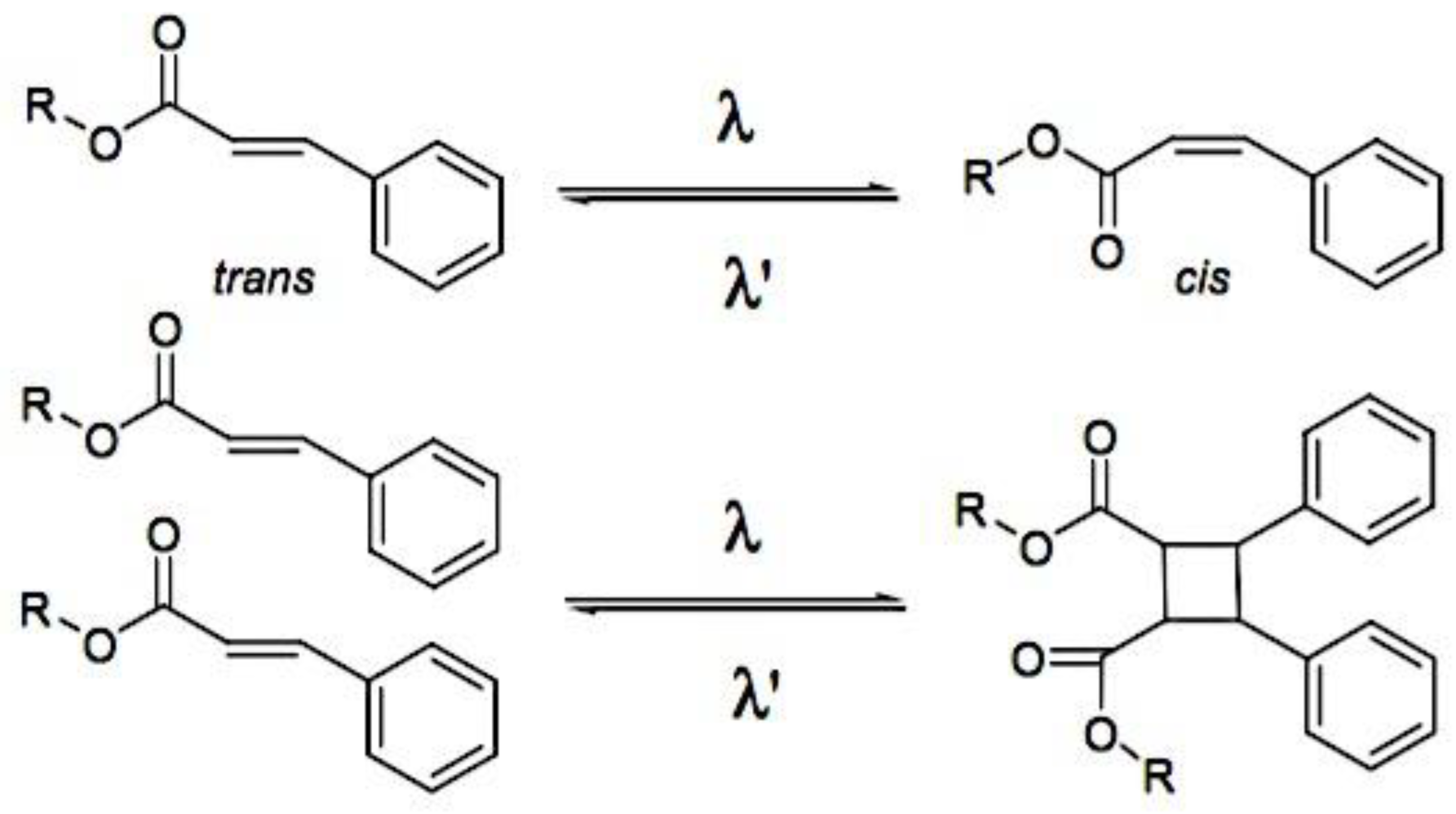

- 8.6.3.3.2. Light-Triggered Reversible Alterations

8.7.3.3. Other Physical Triggers that cause Polymeric Micelles to Become Unstable

8.8.3.3. Multi-Trigger-Responsive Polymeric Micelles

- 8.8.3.3.1. Temperature and pH Sensitivity

- 8.8.3.3.2. Temperature-Sensitive Biodegradable Polymers

- 8.8.3.3.2. Diverse

8.9.3.3. Drug Delivery Guided by Imaging

8.4.3. Combining Stability, Longevity, and Stimulus Sensitivity

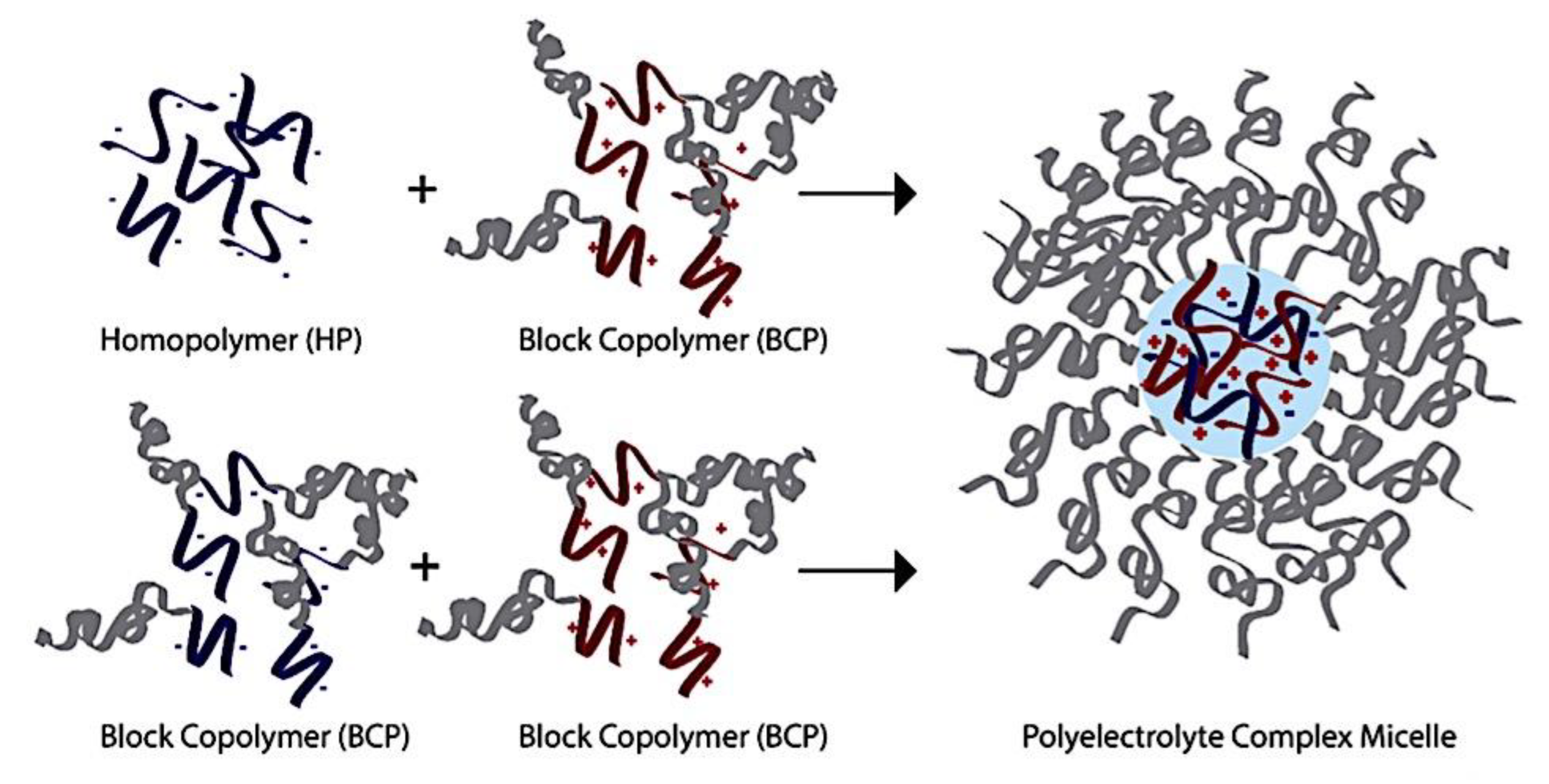

9. Self-Assembly, Synthesis and Theory of Block Copolymers (BCP) Solution

9.1. Self Assembly

9.1.1. General Aspects

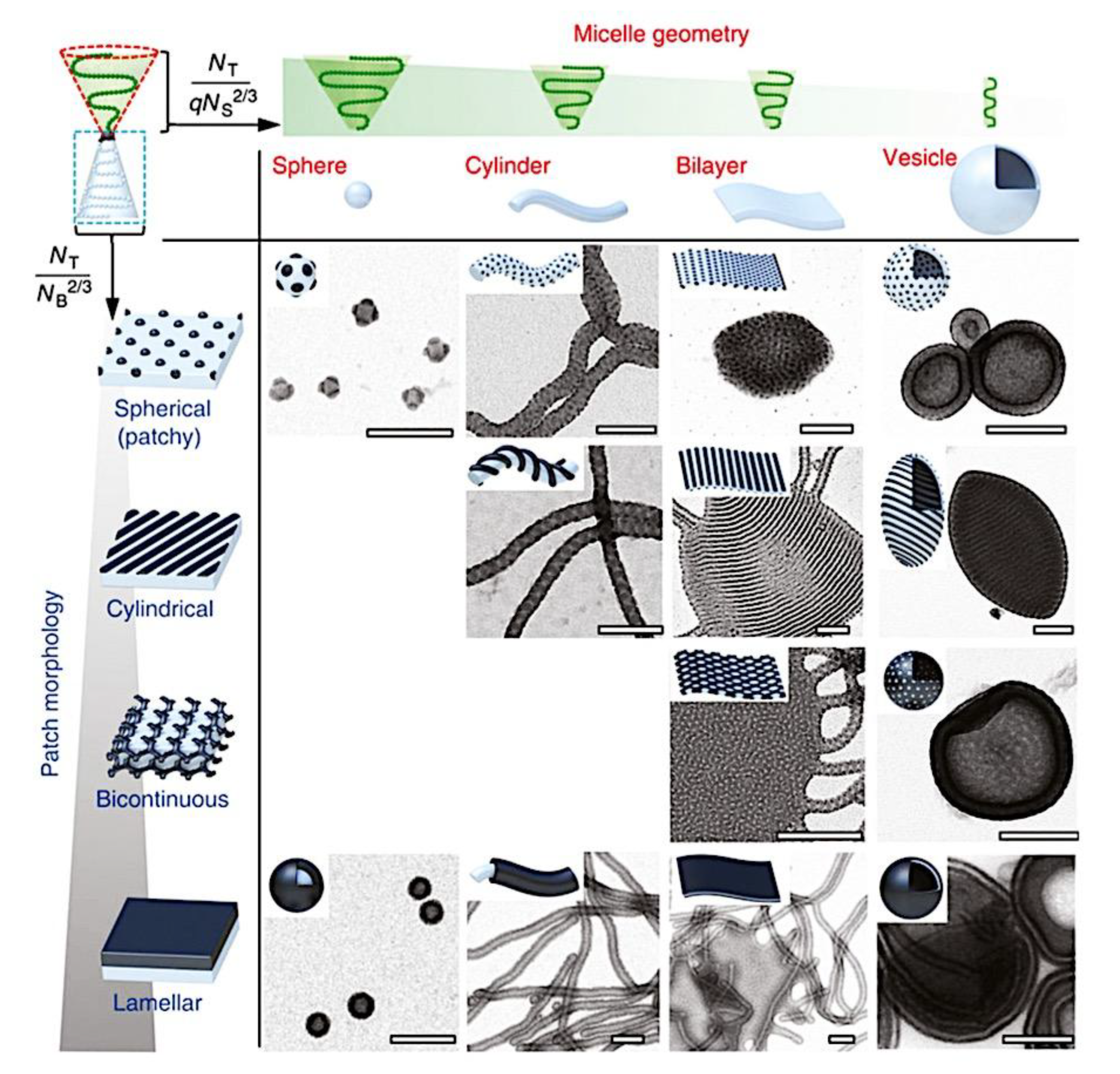

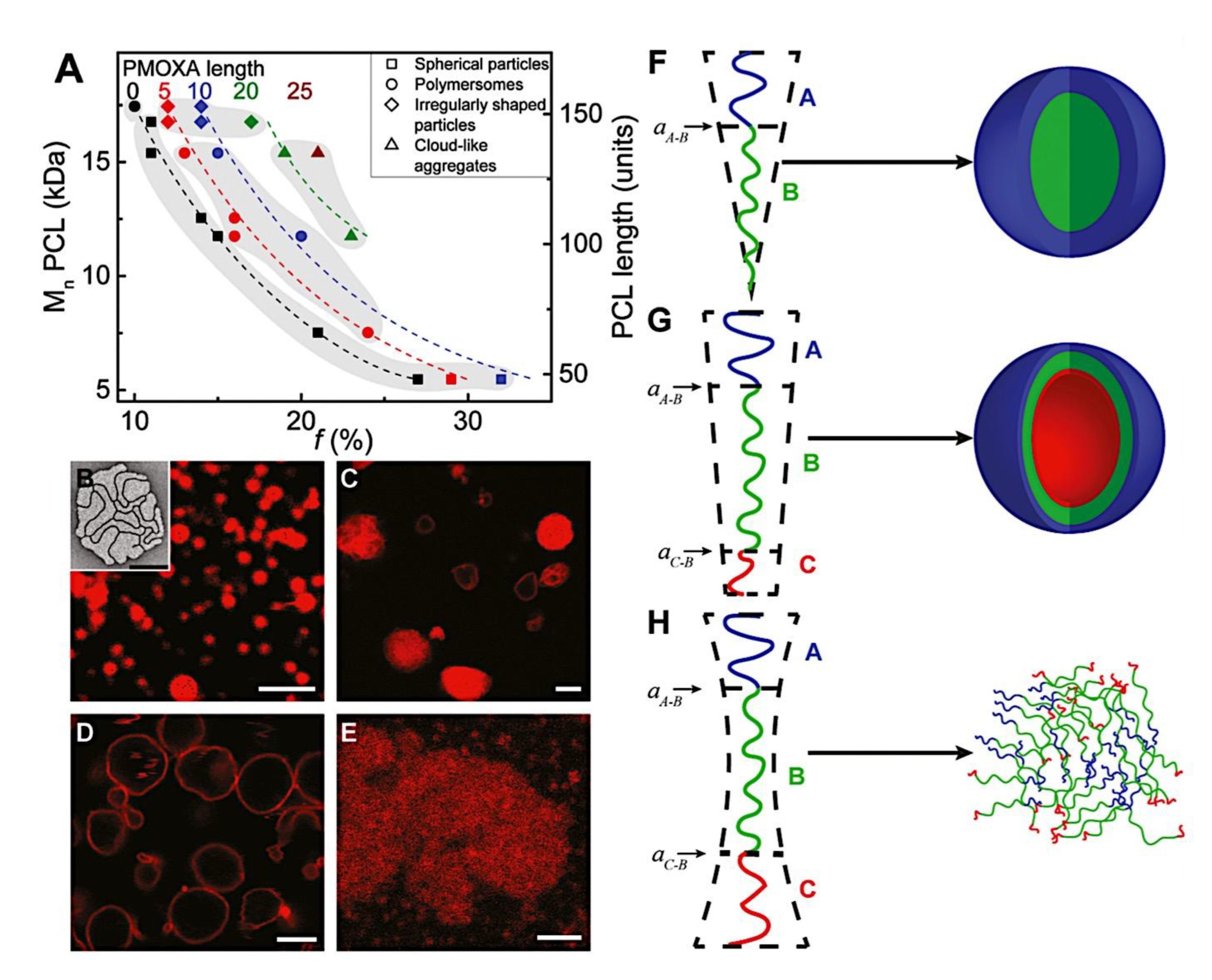

9.1.2. Morphology of Micellar Structures.

9.1.2.1. Spherical, Cylindrical Micelles and Polymersomes

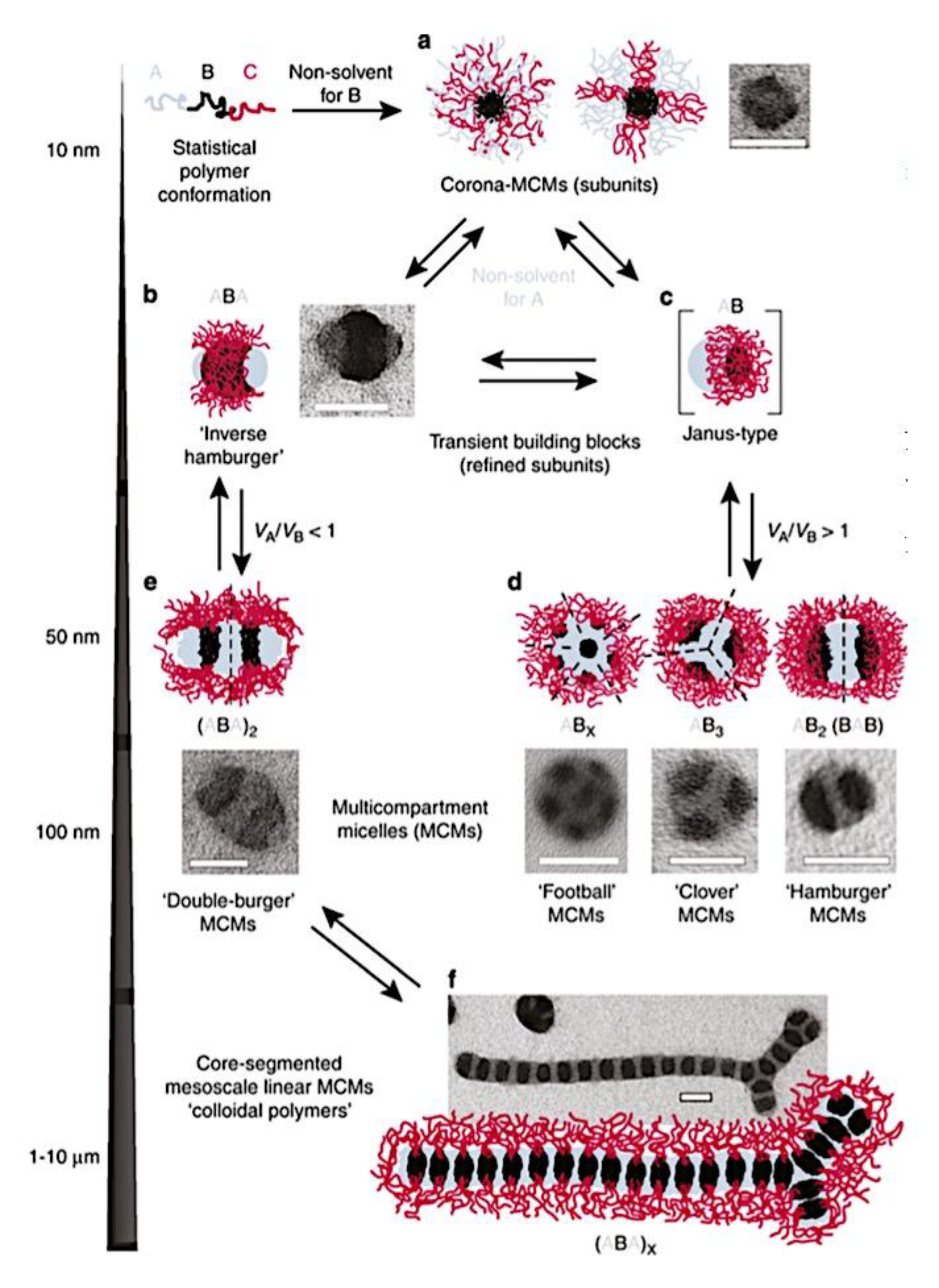

9.1.2.2. Complex Supramolecular Structures

9.1.3. Alternative Self-Assembly Routes

9.1.3.1. Polymerization-Induced and Electrostatic Self-Assembly

9.2. Synthesis and Theory.

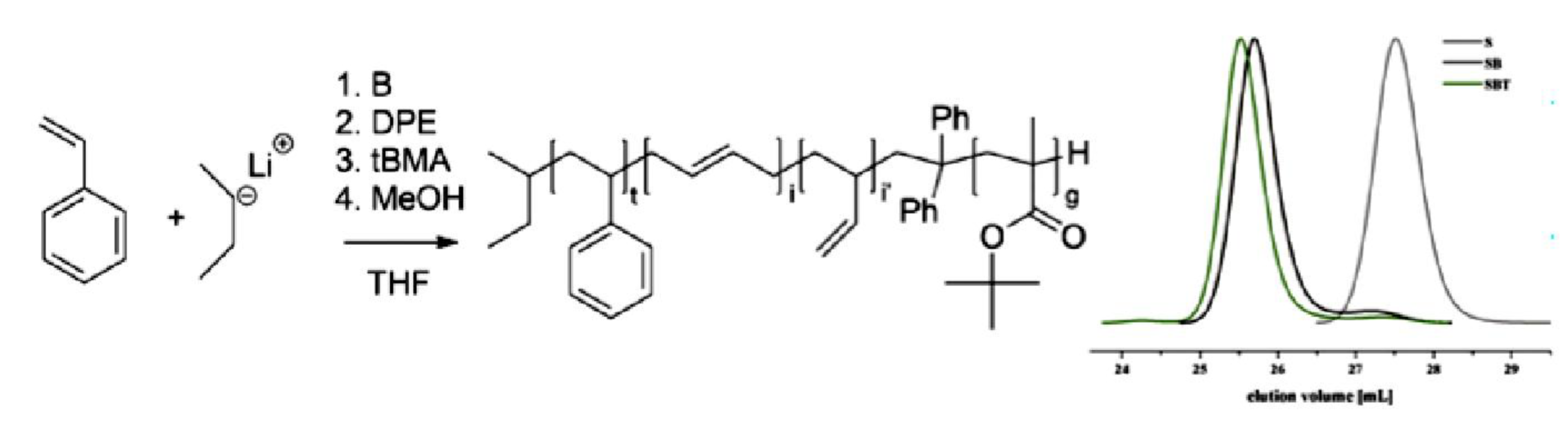

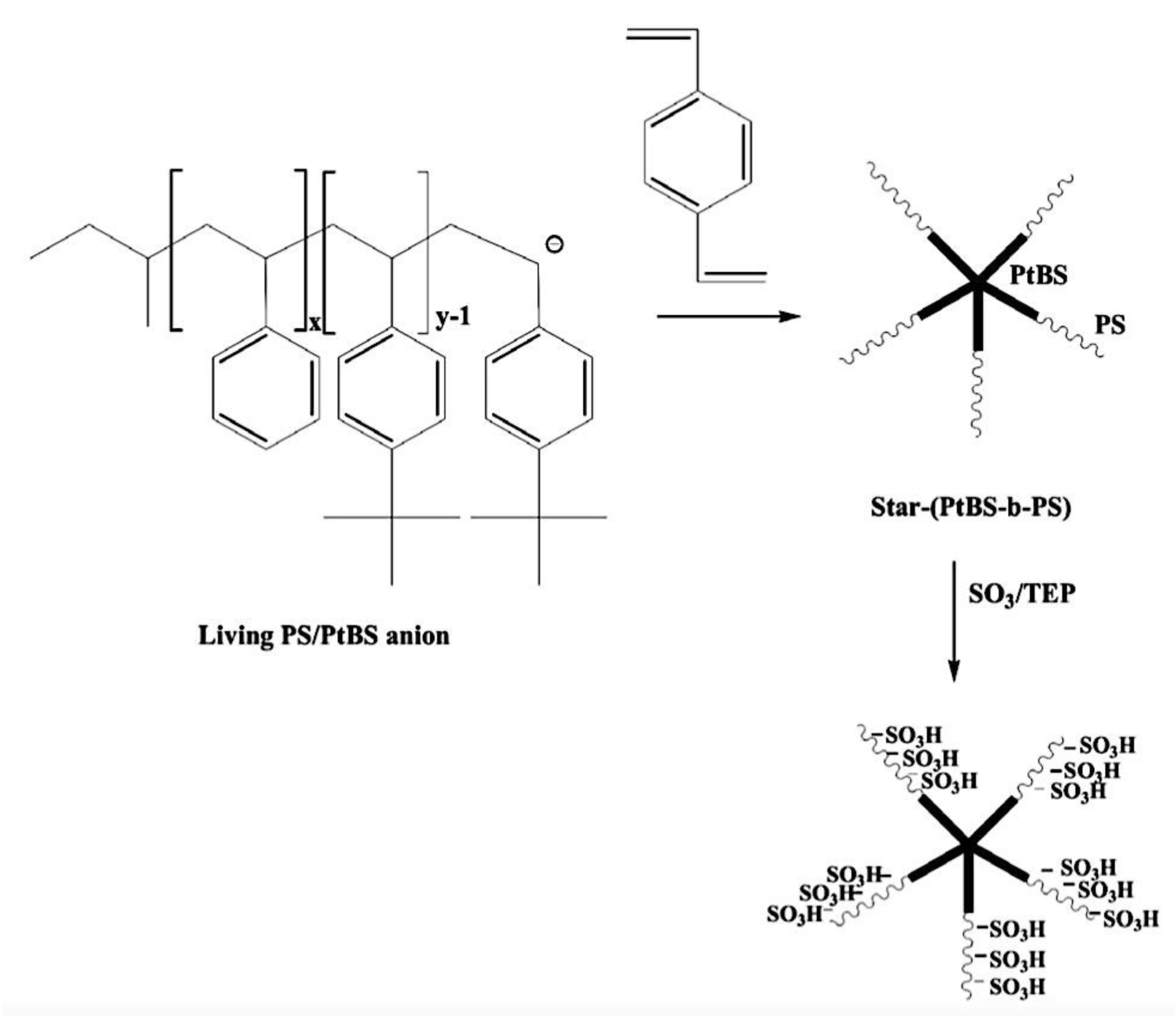

9.2.1. Amphiphilic Block Copolymer (AmBC) Synthesis Using a Mixture of Selective Post-Polymerization Functionalization and Anionic Polymerization

9.2.1.1. Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers

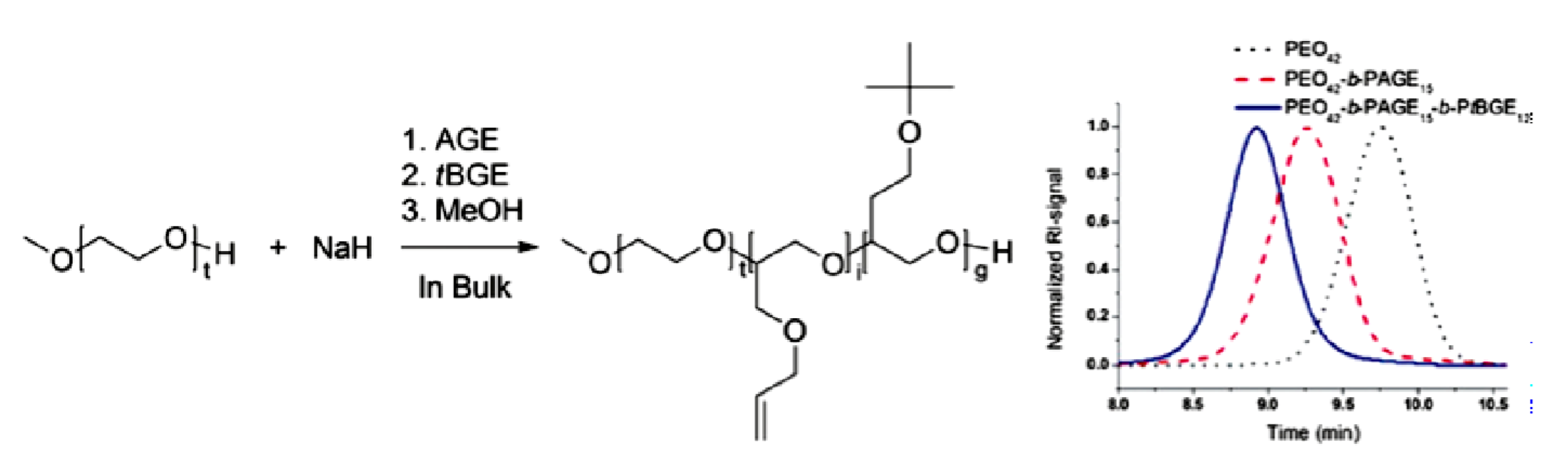

9.2.1.2. Double Hydrophilic Diblock Copolymers

9.2.2. Theory of Nonionic and Ionic Diblock Copolymer Micelles

9.2.3. Synthesis of Linear Triblock and Multiblock Copolymers

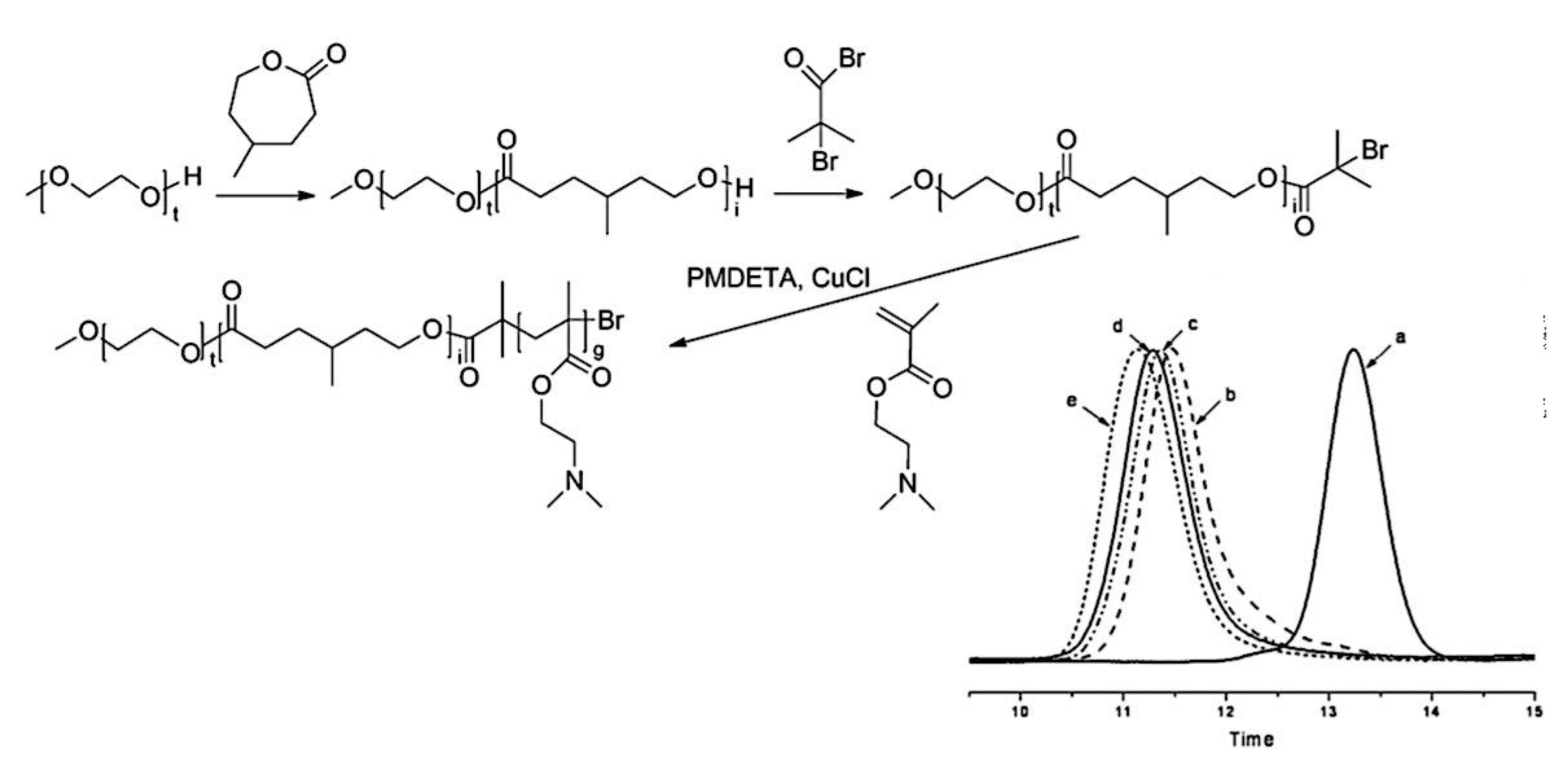

9.2.3.1. Sequential RAFT and ATRP

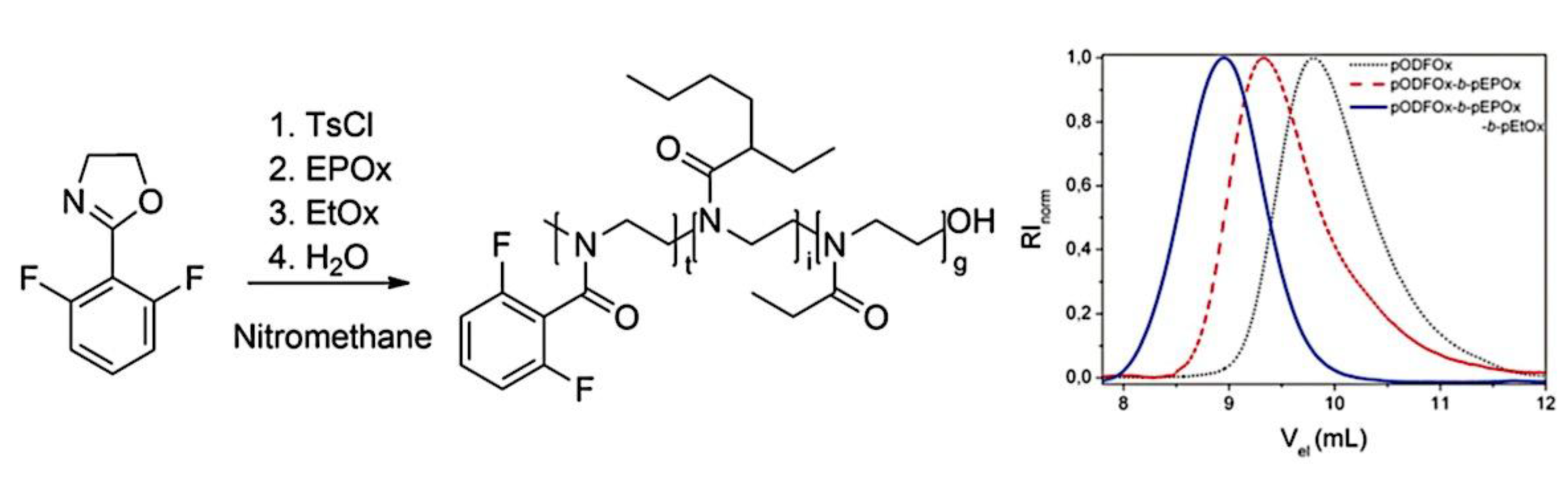

9.2.3.2. Sequential AP, AROP and CROP

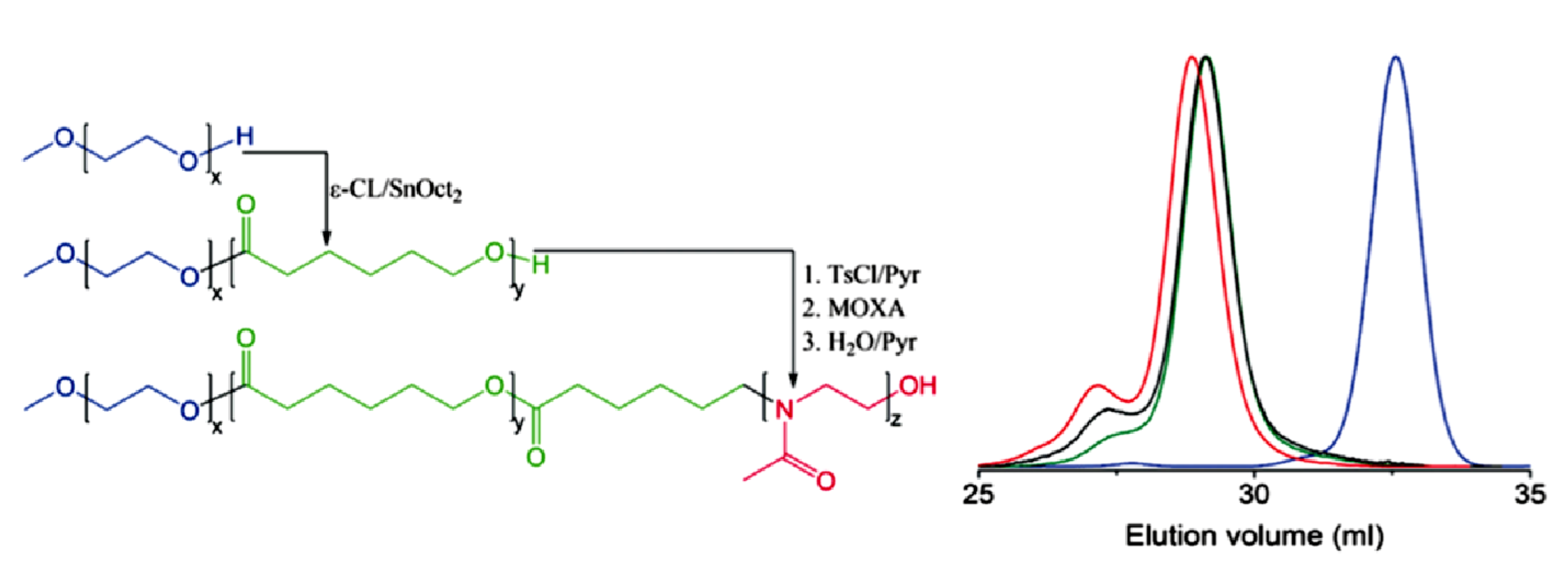

9.2.3.3. Macroinitiators Available Commercially

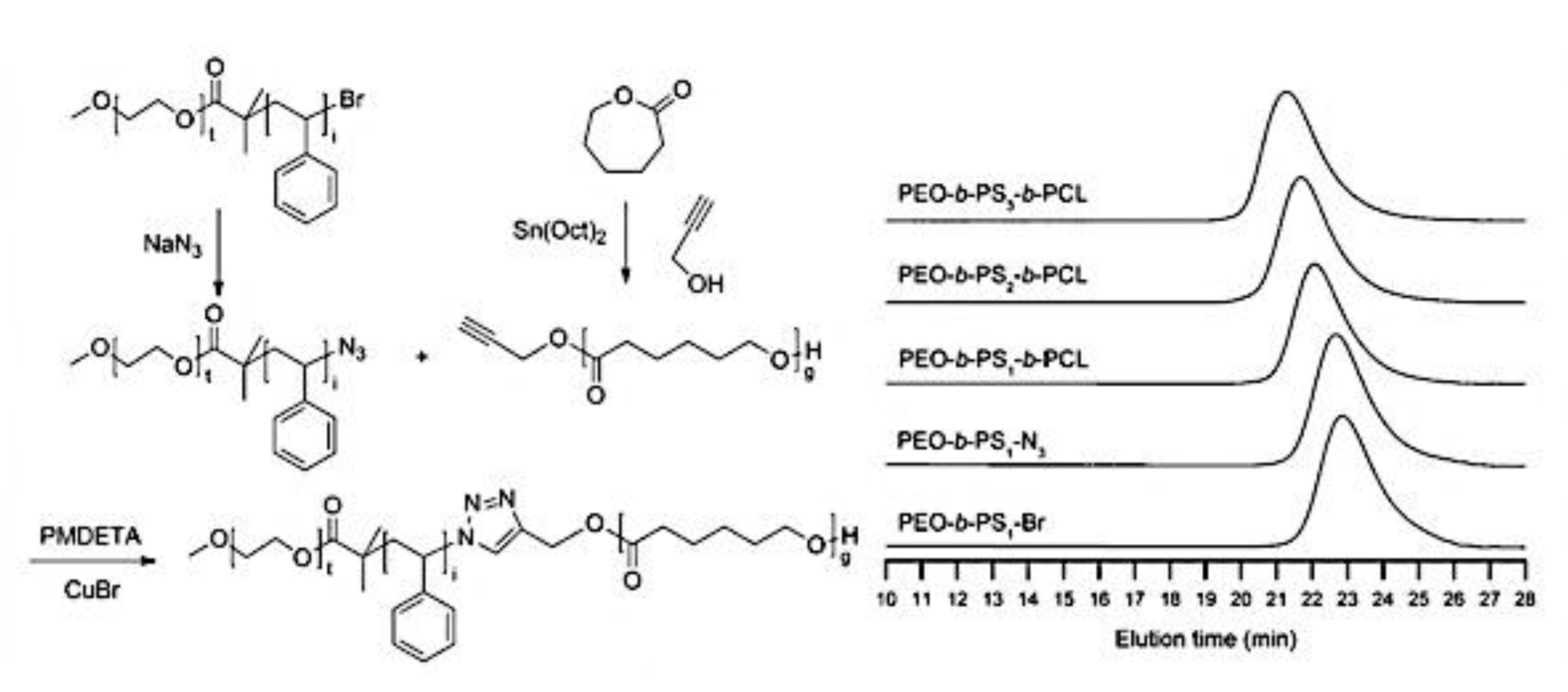

9.2.3.4. Combination of Various Methods for Polymerization: To Combine AB and C by Click Reactions

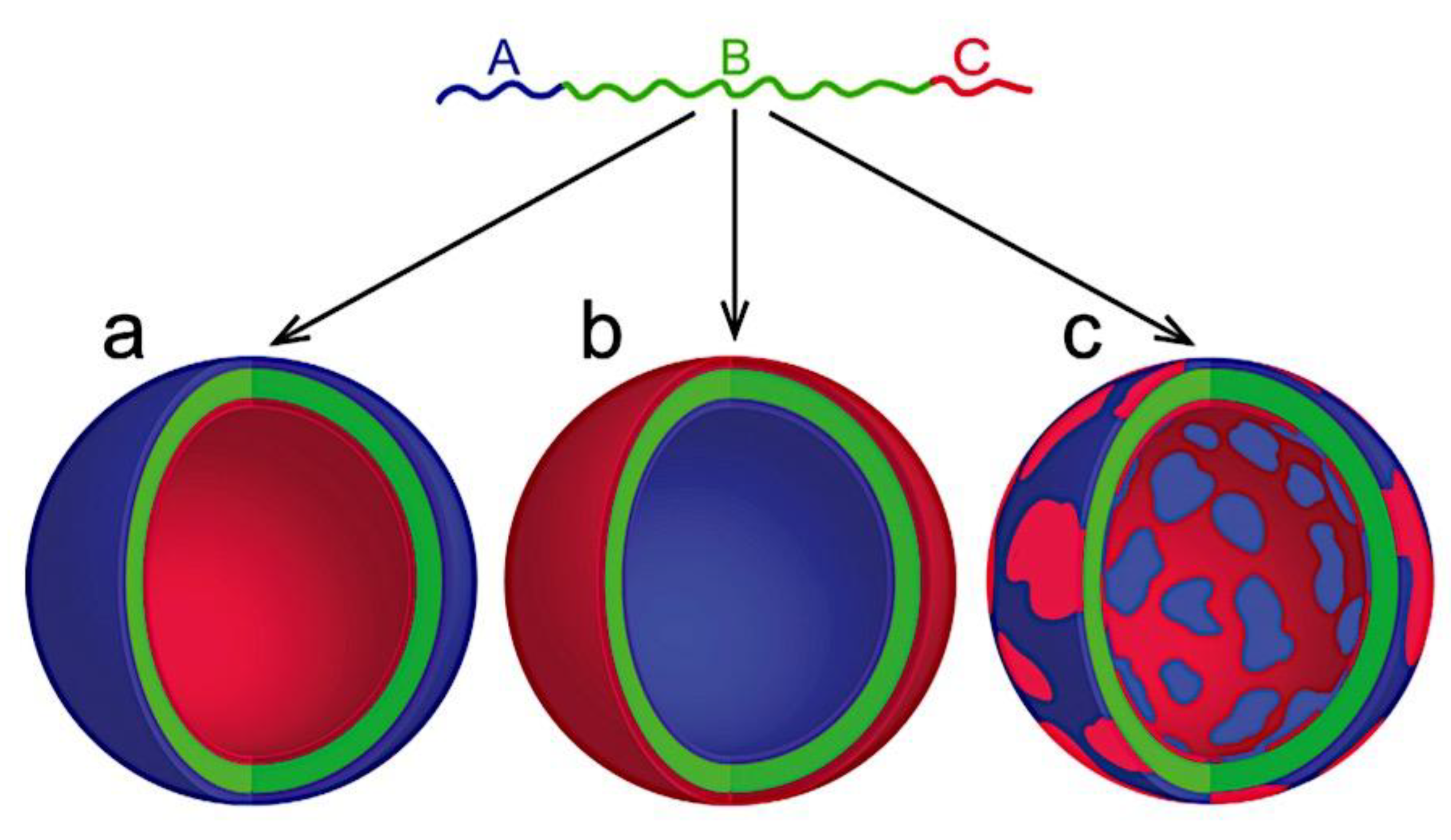

9.2.4. Theory of Triblock Co- and Terpolymer Self-Assembly

9.2.4.1. Soluble C Block ABC Polymers

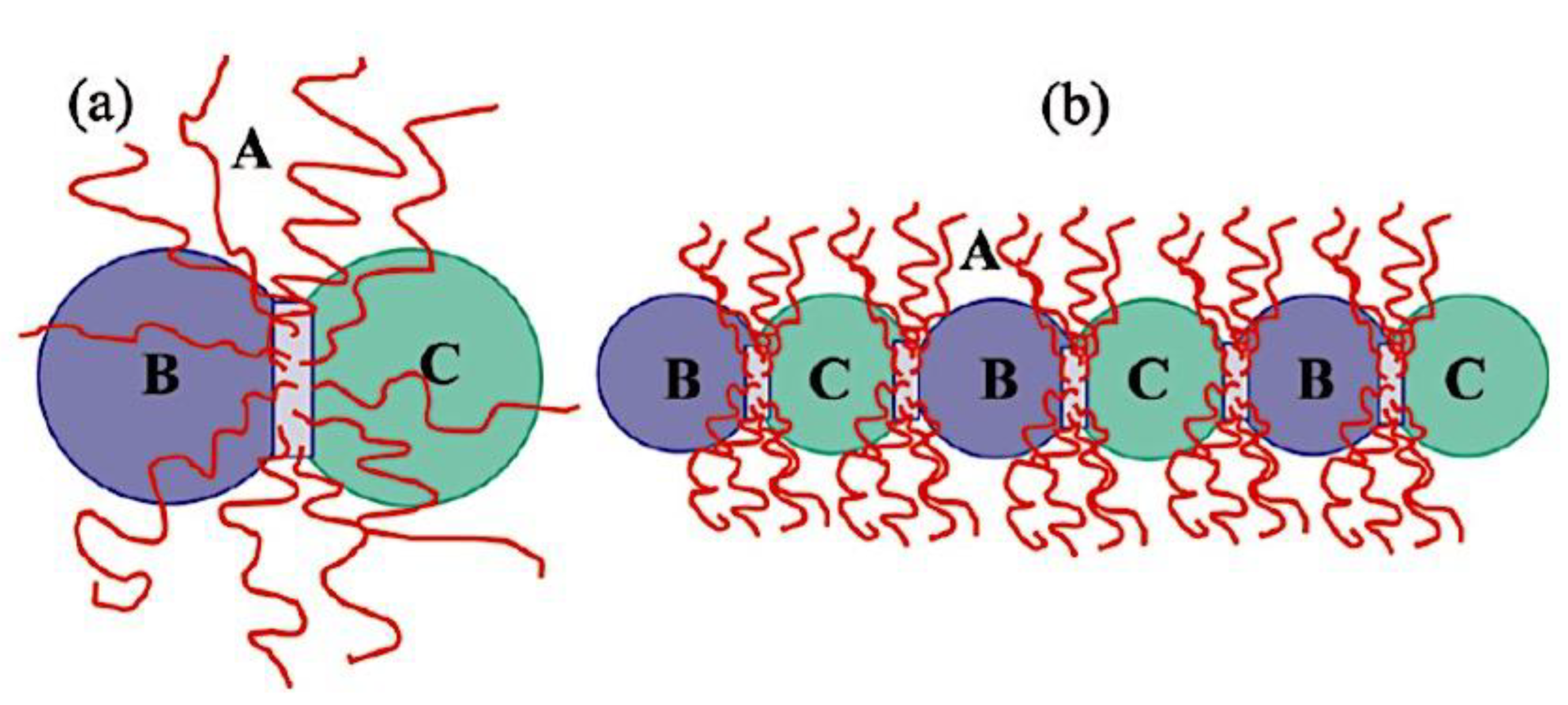

9.2.4.2. Soluble A and C Blocks in ABC Polymers

9.2.5. Non-Linear Architectures

10. Mechanisms of C3M Formation: Mechanism of Micelle Assembly and Disassembly

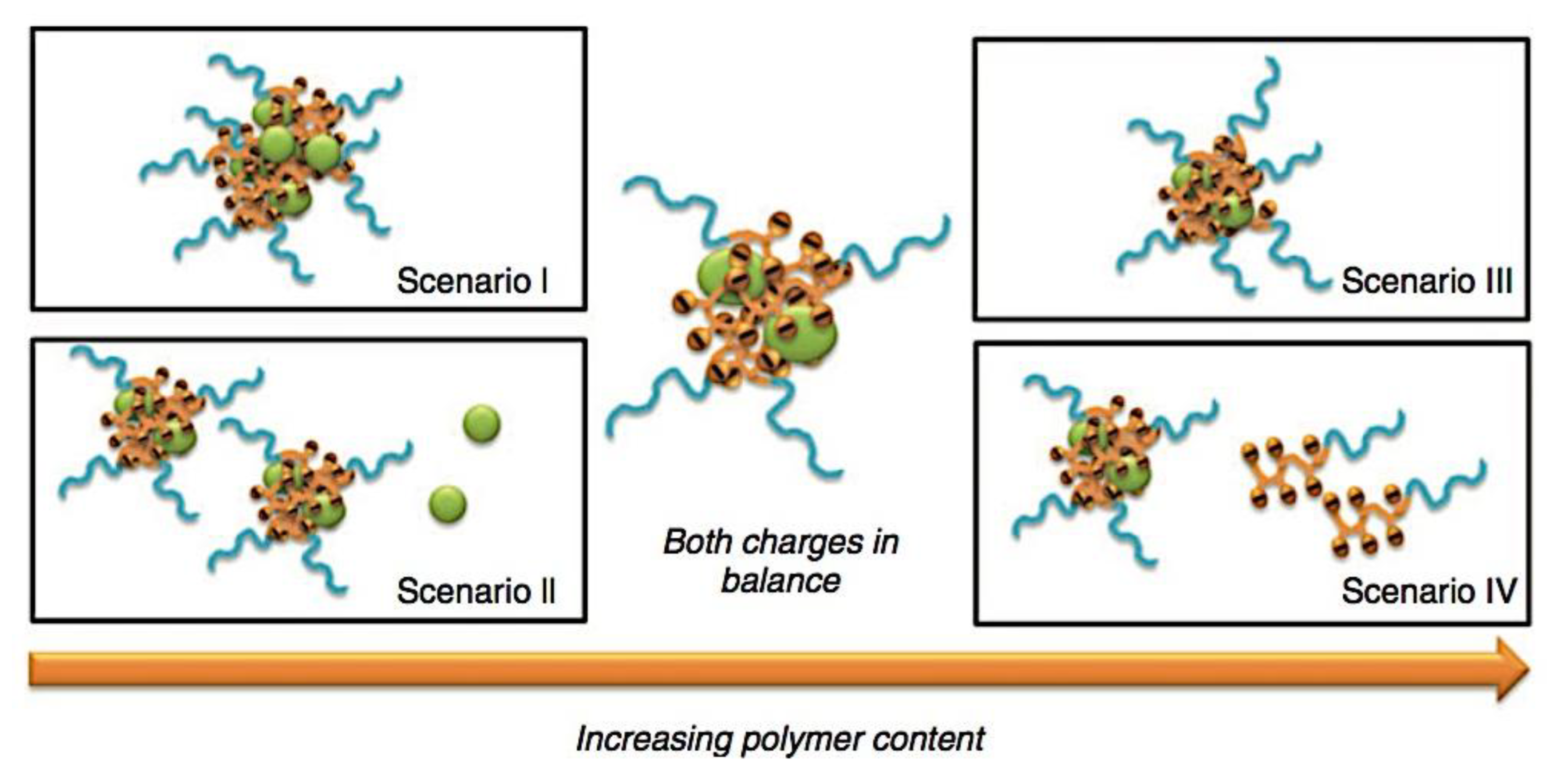

10.1. Mechanism of Aggregation: Factors Influencing and Impact of External Factors, Polymer Architecture, the Length of the Core-Forming Block and Charged Functionality’s Structure towards C3M Formation

10.2. Mechanism of Micelle Assembly and Disassembly

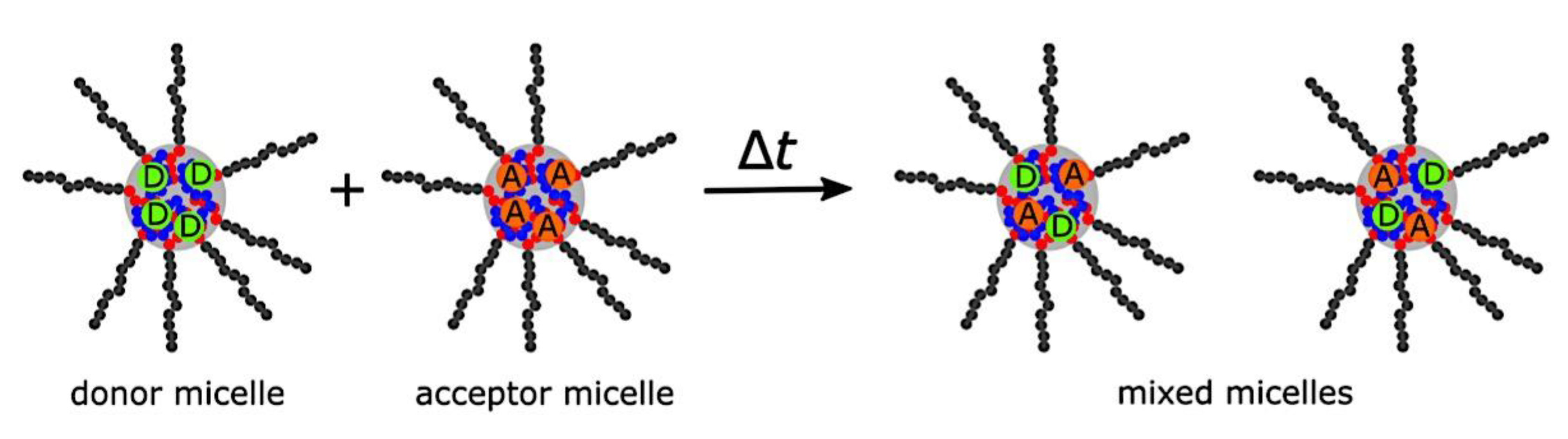

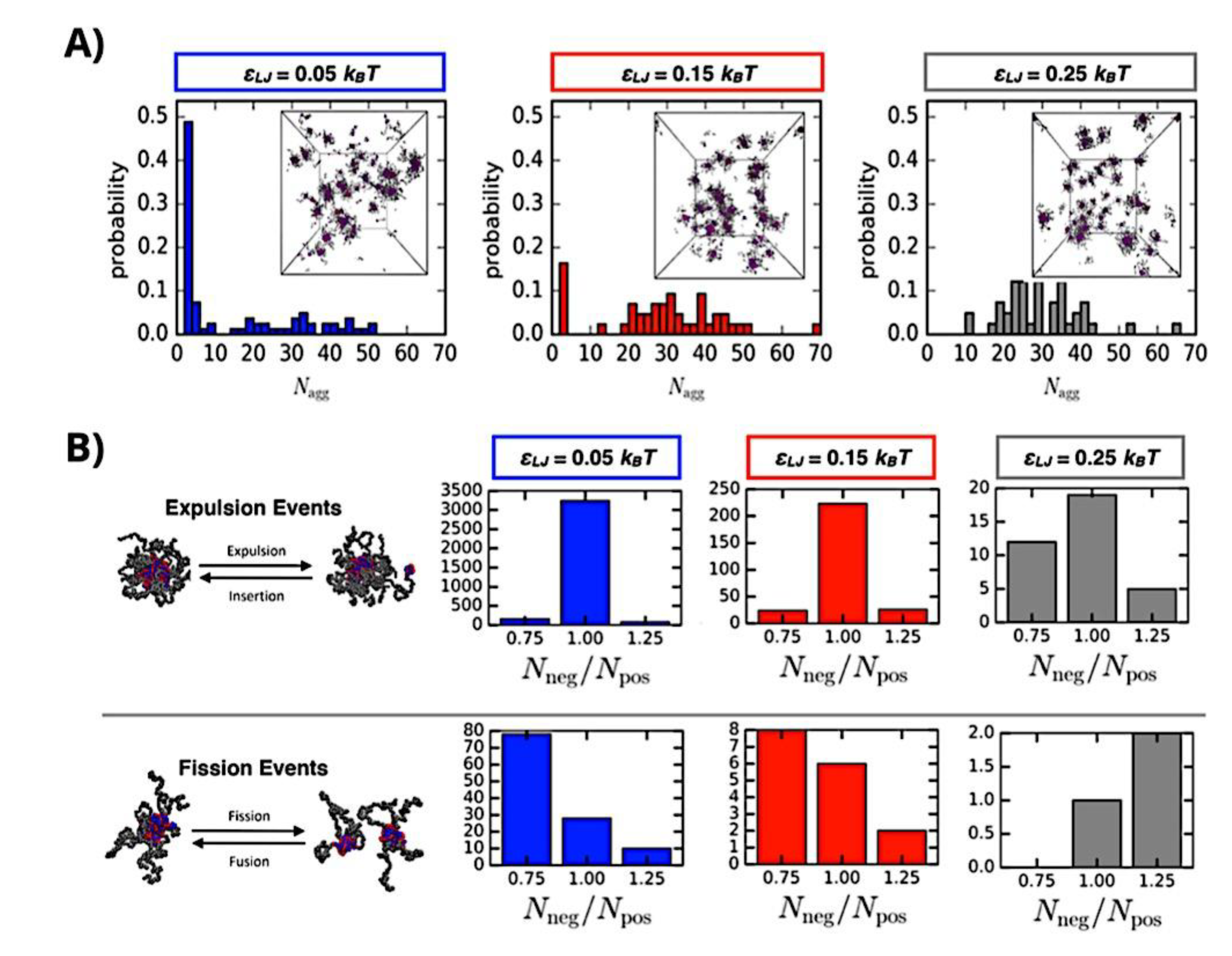

11. Kinetics of Micellization and Kinetics of Exchange

11.1. Kinetics of Micellization

11.2. Kinetics of Exchange

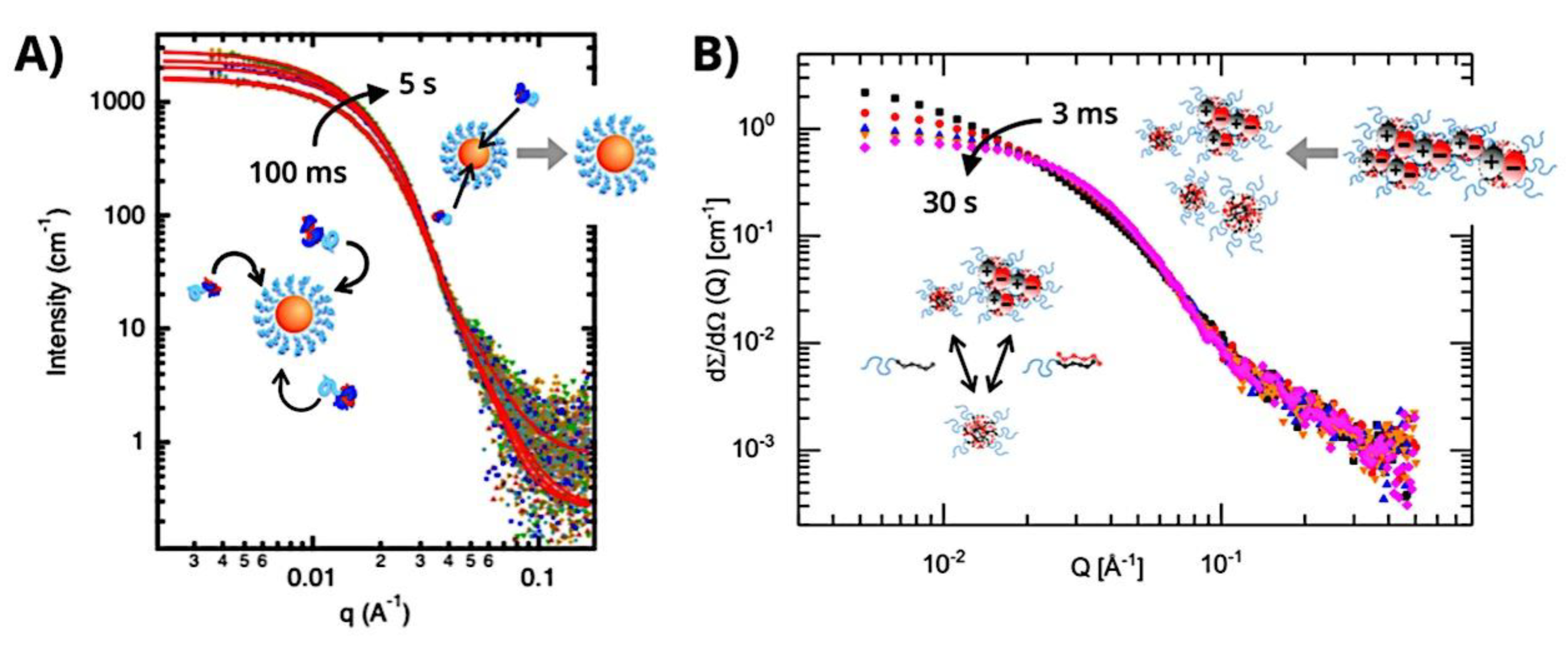

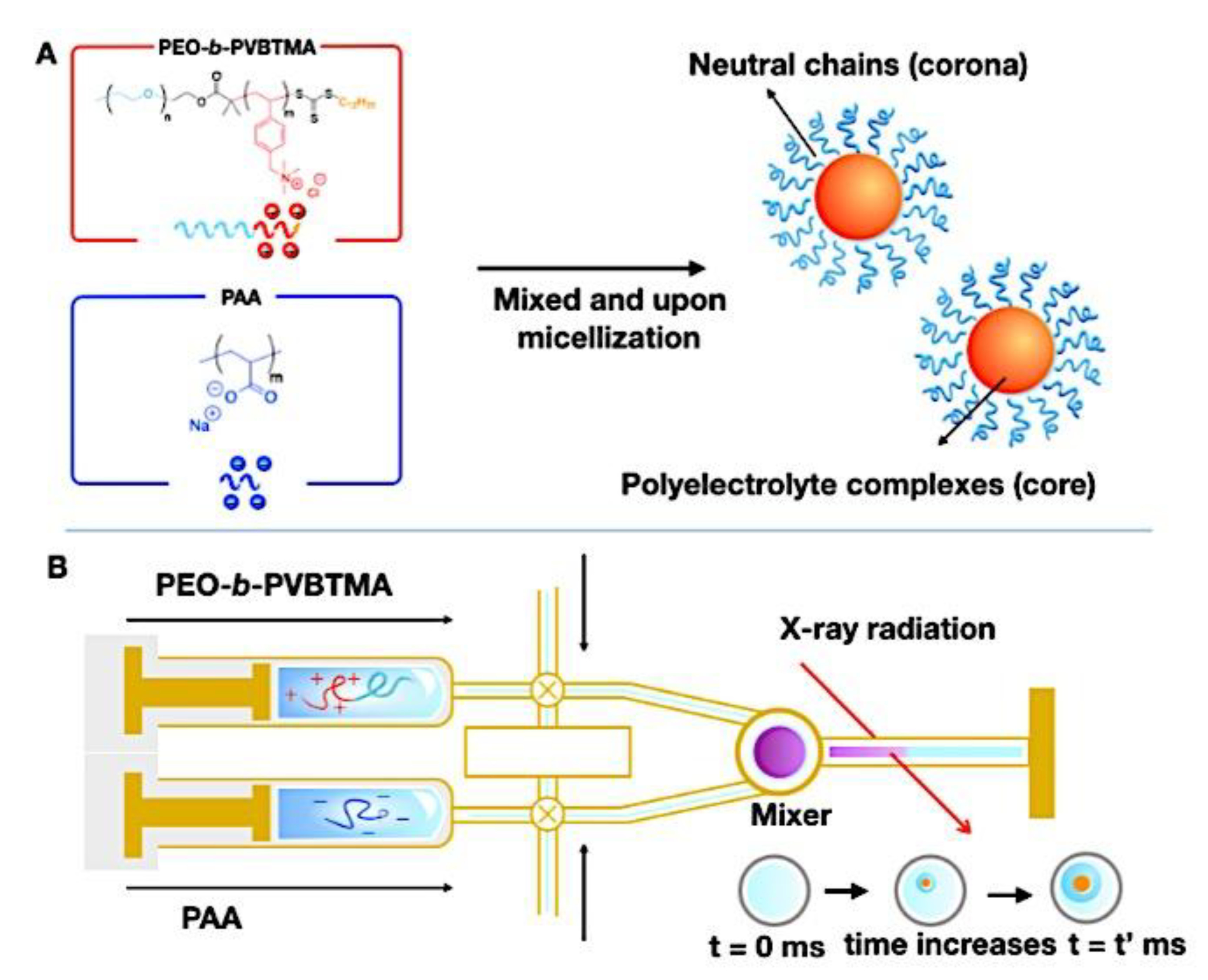

11.3. Time-Resolved in situ Polyelectrolyte Complex Micelle Formation Kinetics Uncovered by Small-Angle X-ray Scattering

12. Balance of Micellar Free Energy

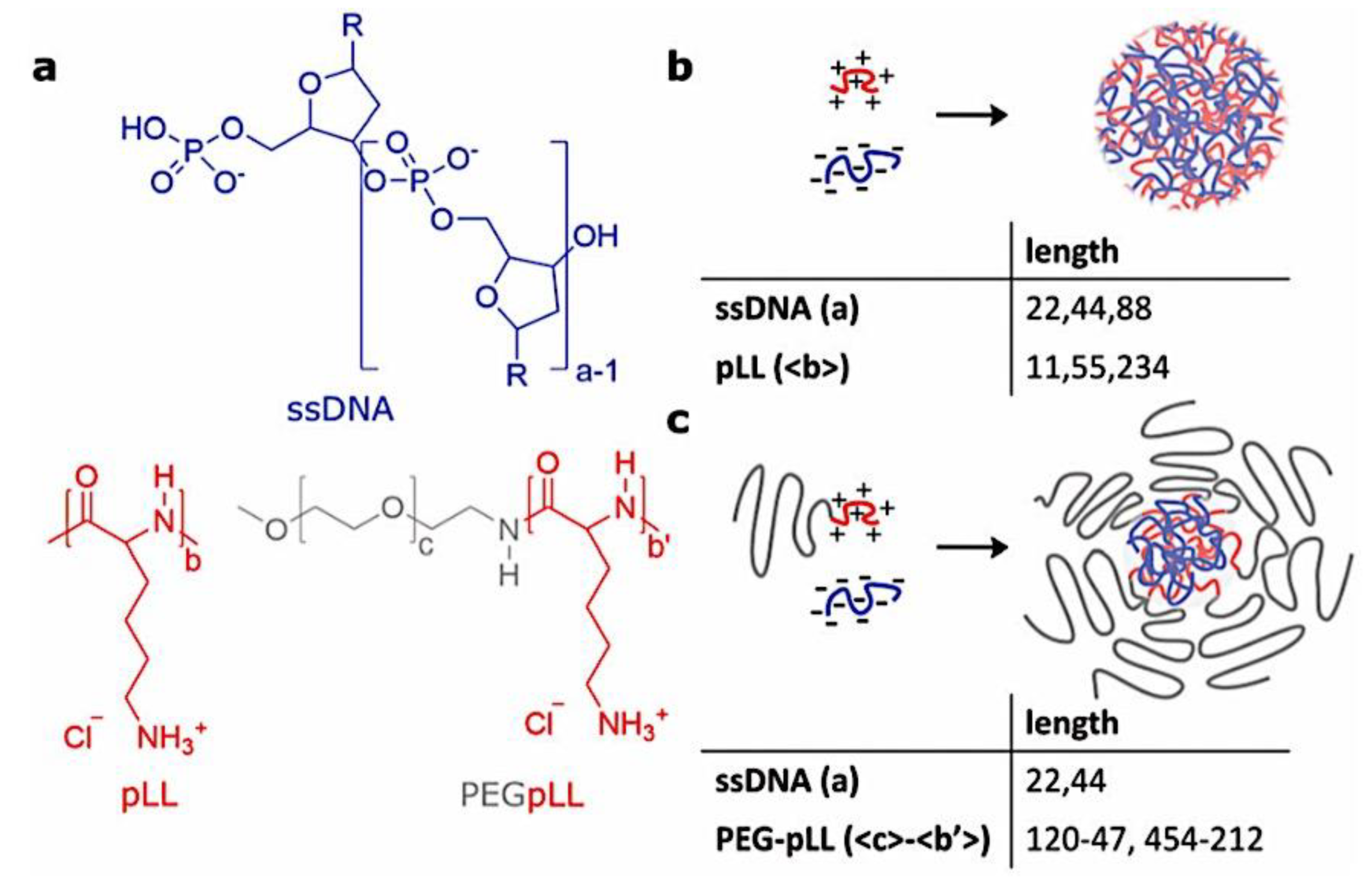

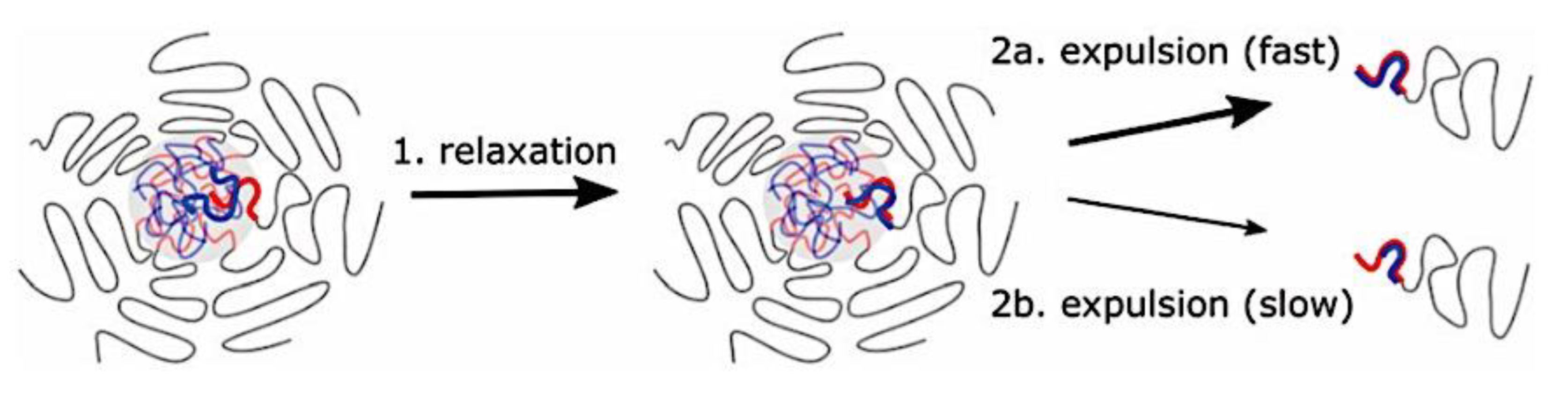

13. Complex Coacervate Droplets and Micelles: DNA Dynamics

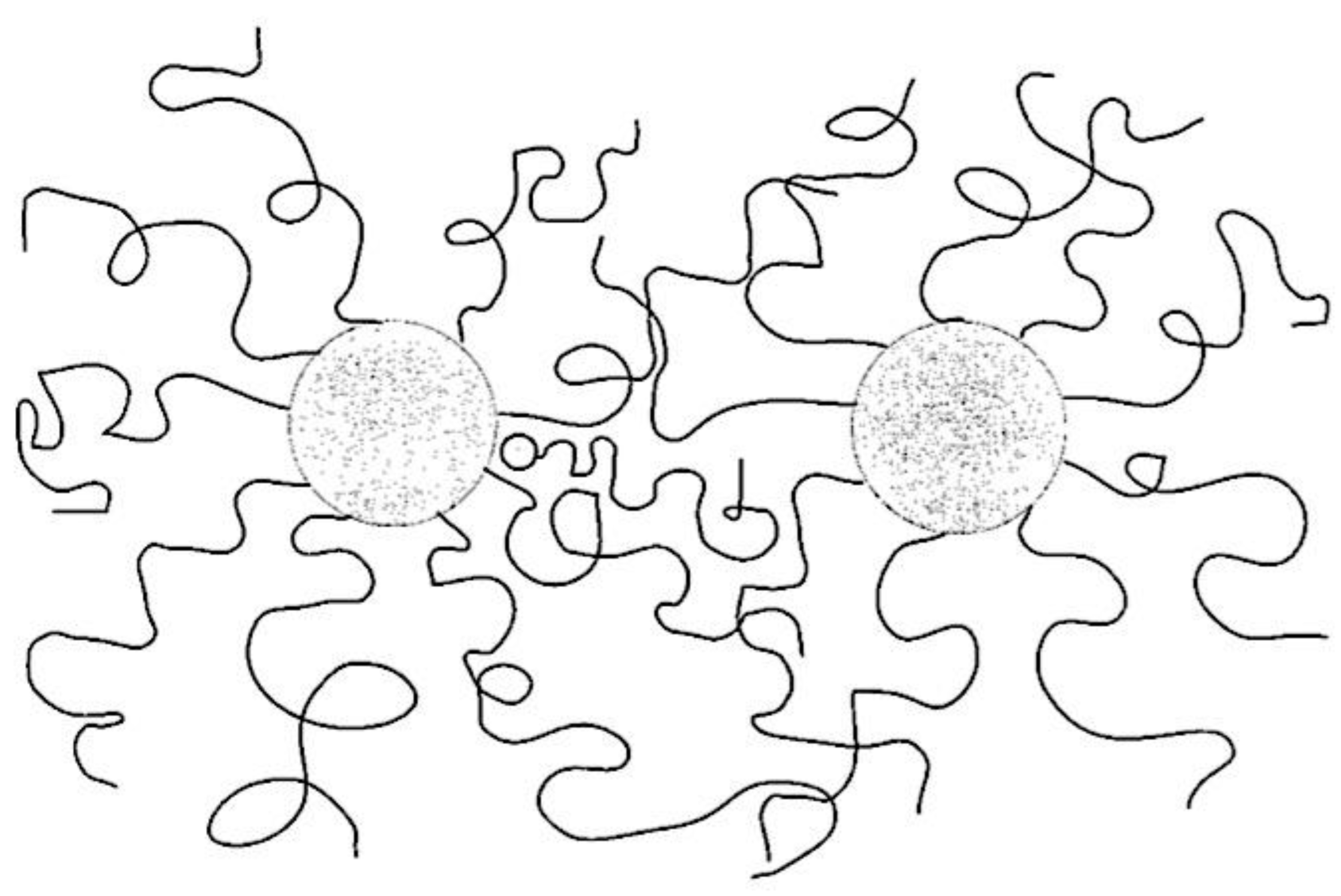

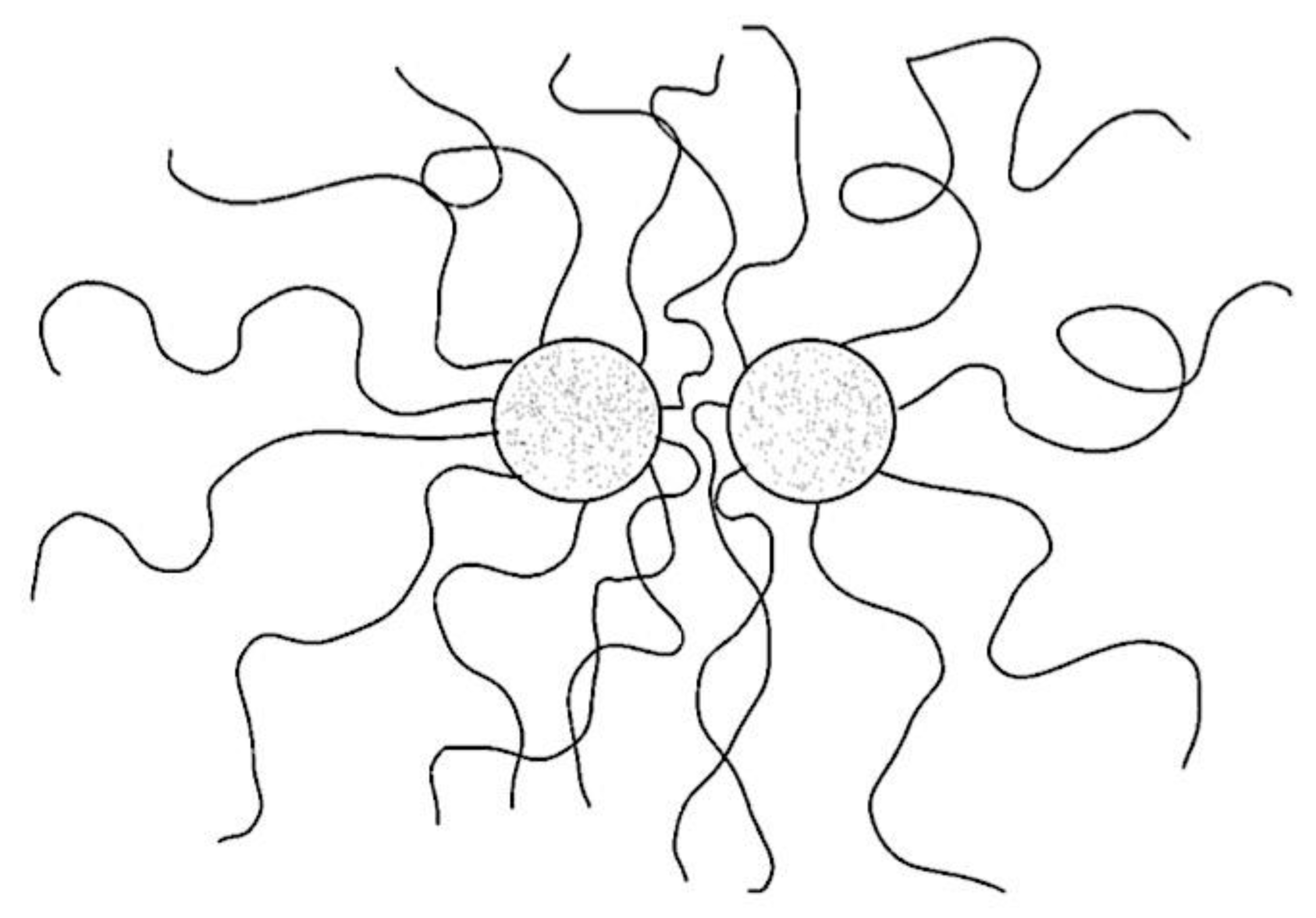

14. C3M in Dilute Solutions: Interparticle Interactions

15. Methods

15.1. ζ- Potential and Viscosimetry

15.2. Conductometry and Static Light Scattering (SLS)

15.3. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Other Methods

16. Applications

16.1. Biomedical Applications

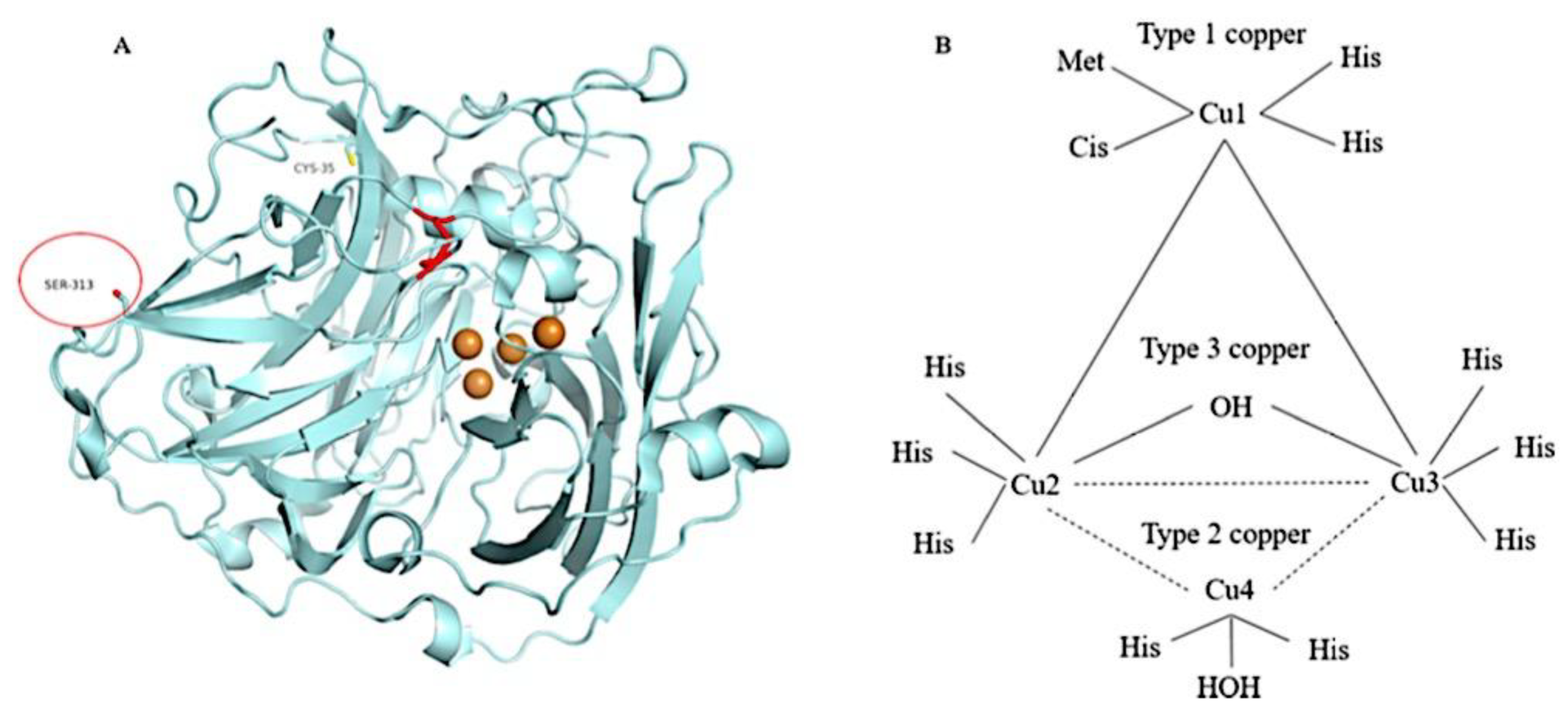

16.1.1. Control of Enzymatic Activity: Optimizing Enzyme Encapsulation Stability and Efficiency in Complicated Coacervate Core Micelles

16.1.2. C3M-Based Biomolecule Delivery

- 16.1.2.1. Nucleic Acid Delivery

16.1.2.2. Brain Delivery

- 16.1.2.2.1. Passing the Brain-Blood Barrier

- 16.1.2.2.2. Potential Applications of C3M in Glioblastoma Treatment.

- 16.1.2.2.2.1. The Importance of Micelle-based Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Therapy Implementation Hindrances

- Due to the CNS’s location of these cells, systemically delivered therapeutic medicines are unable to reach the target malignant tissue without first passing through the BBB. Many therapeutic drugs still do not reach significantly hazardous levels within tumors, despite the existence of a weakened vasculature that may exacerbate the intratumoral EPR impact.[188]

- Necrotic and hypoxic tissue can be found in certain regions of GBM tumors, while neovascularization can be found in other locations. Hypovascularization, fibrosis, and necrotic pockets are the main reasons for reduced intratumoral drug distribution, whereas hypervascularized regions promote accumulation in the surrounding tissue. It's critical to comprehend the distribution of nanoparticles throughout tumors since certain cell populations, such self-renewing GBM cancer stem cells that sustain a tumor, may be restricted to particular vascular habitats.[1435,1436]

- Depending on how it is administered, therapeutic delivery has inherent flaws. Many systemically administered therapeutic drugs produce non-specific organ toxicity and are quickly cleared from circulation by reticuloendothelial cells. Thus, enhancements in the duration of drug circulation and the precision of targeting represent significant advancements for this mode of delivery. The delivery of various dose regimens to a patient and high interstitial pressures that result in poor molecular dispersion limit intratumoral administration of therapeutic medicines.[1437]

- While these clinical micelle formulations improve the potency of the medicine in several solid tumor types, they do not yet have any targeting moieties that could enable increased accumulation in brain tumors or the central nervous system. To increase the effectiveness of currently available formulations, it could be necessary to target alternative receptors expressed on glioma cells molecularly.

- Systemic toxicity may unavoidably be a problem if high dosages of given micelles are required to guarantee sufficient intratumoral accumulation because they lack a controlled-release capability. In order to minimize non-specific release prior to reaching the tumor location, it would be ideal to include stimulus-triggered releasing mechanisms of encapsulated compounds, which would enable release only inside the tumor area.

- 16.1.2.2.2.2. Glioma-Specific Targeting Moieties

- 16.1.2.2.2.3. Therapeutic Micelle Delivery to Brain Tumors

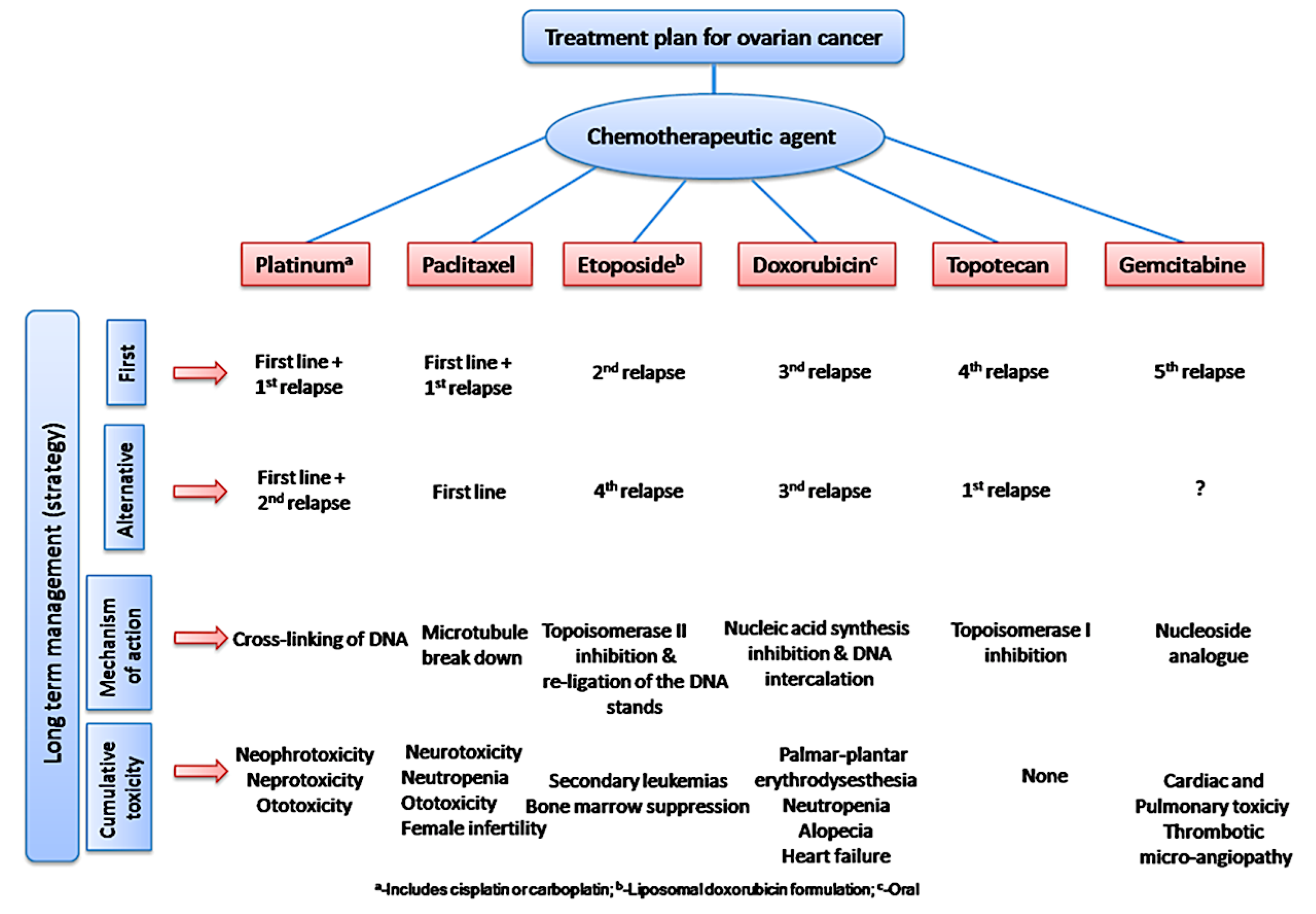

- 16.1.2.3. Drug Delivery

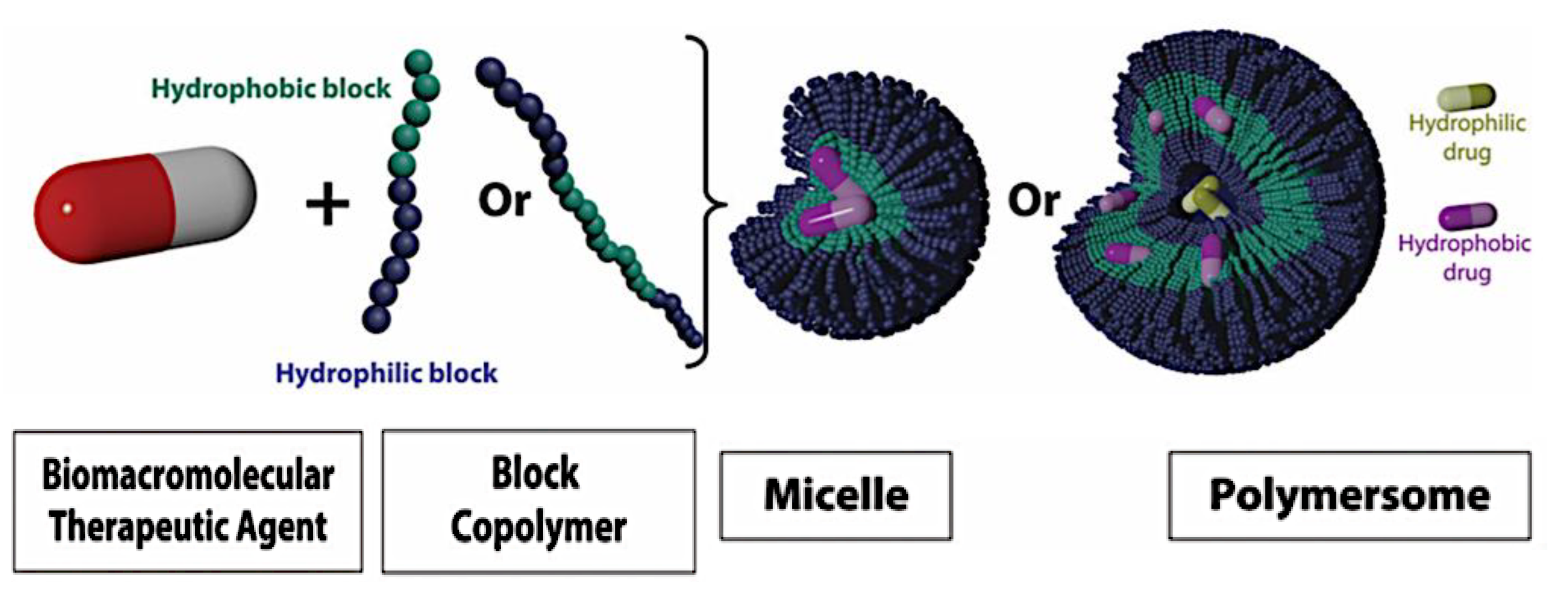

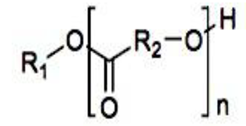

- 16.1.2.3.1. Polymeric Micelles and Vesicles: Their Characteristics

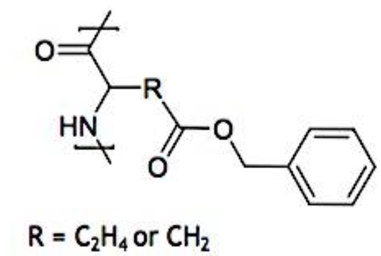

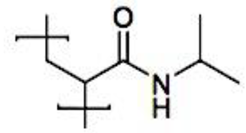

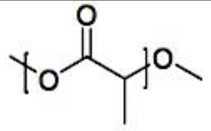

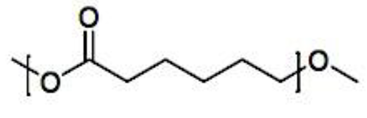

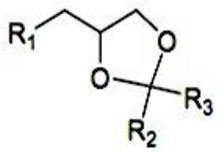

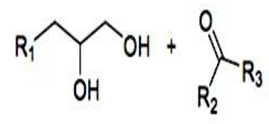

- 16.1.2.3.2. The Building Blocks

- 16.1.2.3.3. Polymeric Micelles: Loading, Retention, and Release of Drugs

- 16.1.2.4. Delivery of Therapeutic Proteins

16.1.3. Diagnostics, Imaging and Theranostics: Combination of Diagnosis and Treatment

16.2. Nanofabrication

16.3. BCP Self-Assembly Applications in Ionic Liquids (ILs)

16.3.1. Soft Actuators

16.3.2. Electrochemical Applications and Devices

16.3.3. Lithium-Ion Batteries

16.3.4. The Electrolyte-Gated Transistors

16.4. Other Applications

17. Micellar Formulations in Clinical Trials

17.1. Genexol-PM and NK105

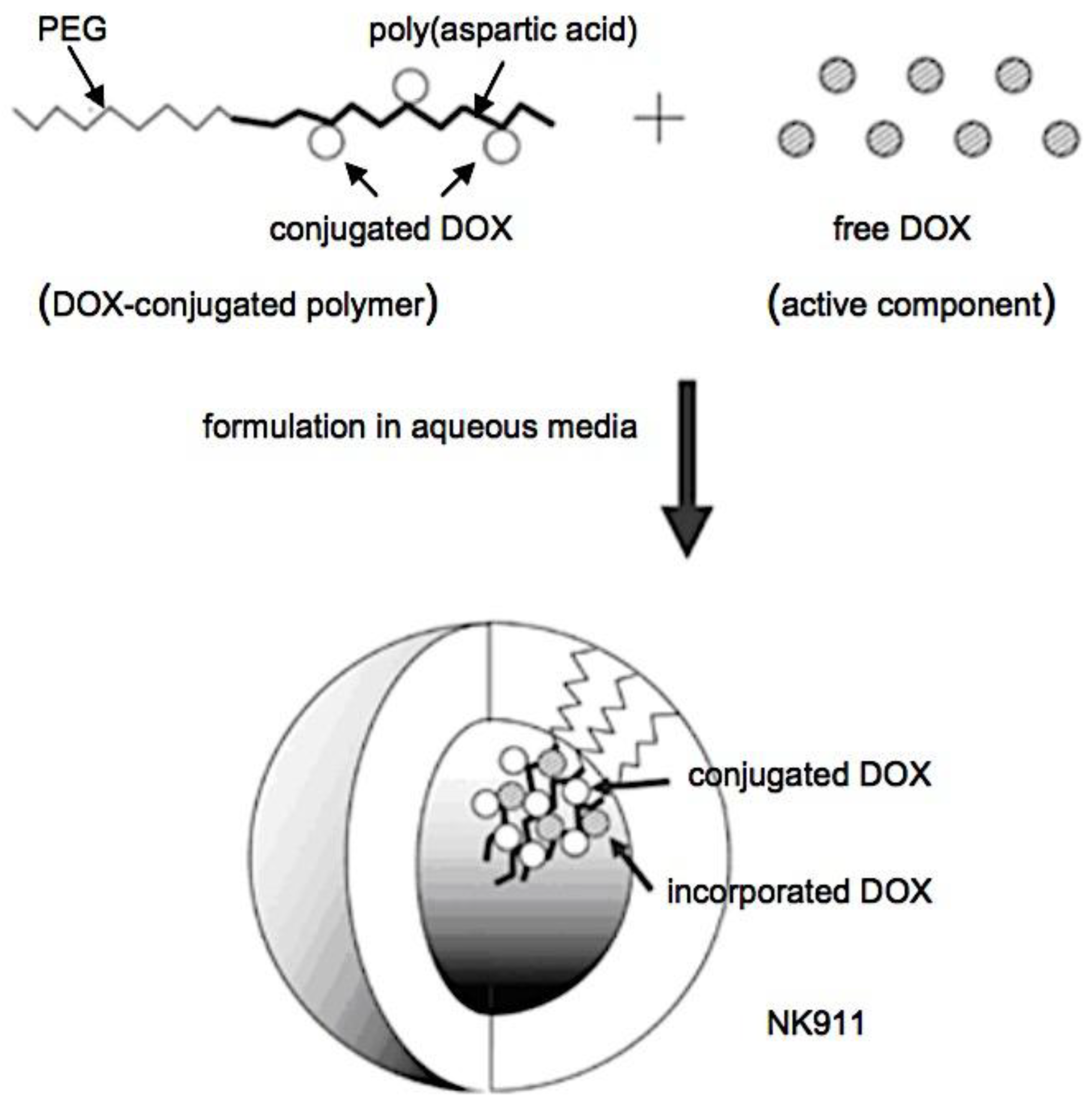

17.2. SP1049C AND NK911

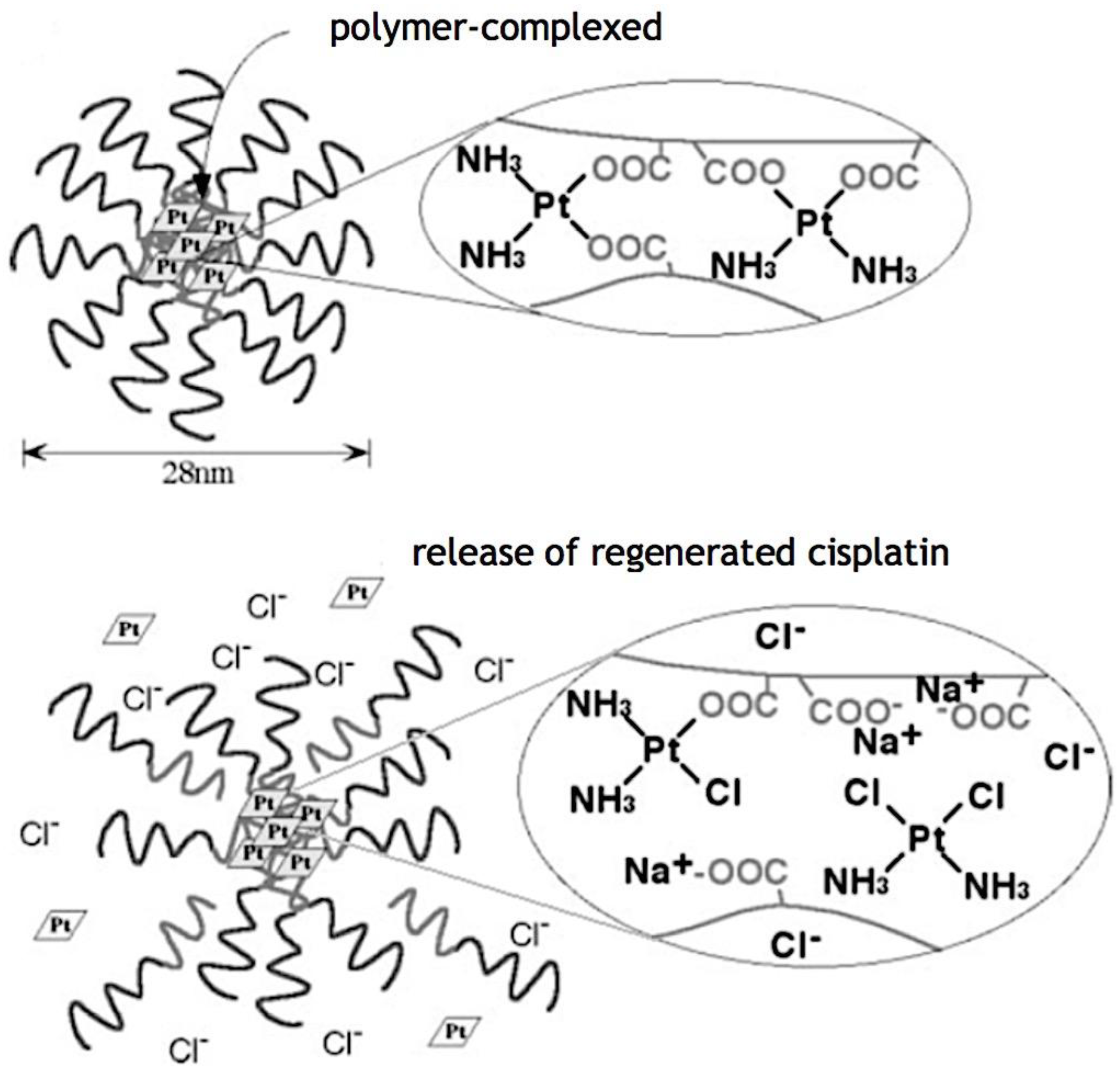

17.3. NC-6004 AND NC-4016

17.4. NC-6300 and NK102

Conclusion and Perspective

Author Information

Acknowledgments

References

- Mitragotri, S.; Burke, P.; Langer, R. Overcoming the challenges in administering biopharmaceuticals: formulation and delivery strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttenthaler, M.; King, G. F.; Adams, D. J.; Alewood, P. F. Trends in peptide drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J. A.; Witzigmann, D.; Thomson, S. B.; Chen, S.; Leavitt, B. R.; Cullis, P. R.; van der Meel, R. The current landscape of nucleic acid therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B. C.; Fletcher, R. B.; Kilchrist, K. V.; Dailing, E. A.; Mukalel, A. J.; Colazo, J. M.; Oliver, M.; Cheung-flynn, J.; Brophy, C. M.; Tierney, J. W.; Isenberg, J. S.; Hankenson, K. D.; Ghimire, K.; Lander, C.; Gersbach, C. A.; Duvall, C. L. An Anionic, Endosome-Escaping Polymer to Potentiate Intracellular Delivery of Cationic Peptides, Biomacromolecules, and Nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G. Therapeutic insulins and their large-scale manufacture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 67, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C. First generic biologics finally approved. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A. L.; Dhimolea, E.; Reichert, J. M. Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2018. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfram Julie, A.; Donahue, J. K. J. Am. J . Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e000119. [Google Scholar]

- Lostalé-Seijo, I.; Montenegro, J. Synthetic materials at the forefront of gene delivery. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2, 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainov, N. G. A phase III clinical evaluation of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase and ganciclovir gene therapy as an adjuvant to surgical resection and radiation in adults with previously untreated glioblastoma multiforme. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000, 11, 2389–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, W. J. Jr.; Ostrem, J. L.; Verhagen, L.; Starr, P. A.; Larson, P. S.; Bakay, R. A.; Taylor, R.; Cahn-Weiner, D. A.; Stoessl, A. J.; Olanow, C. W.; Bartus, R. T. Safety and tolerability of intraputaminal delivery of CERE-120 (adeno-associated virus serotype 2-neurturin) to patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease: an open-label, phase I trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartus, R. T.; Baumann, T. L.; Siffert, J.; Herzog, C. D.; Alterman, R.; Boulis, N.; Turner, D. A.; Stacy, M.; Lang, A. E.; Lozano, A. M.; Olanow, C. W. Safety/feasibility of targeting the substantia nigra with AAV2-neurturin in Parkinson patients. Neurology 2013, 80, 1698–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F, P. ; Thomas, S. J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J. L.; P ́erez Marc, G.; Moreira, E. D.; Zerbini, C.; Bailey, R.; Swanson, K. A.; Roychoudhury, S.; Koury, K.; Li, P.; Kalina, W. V.; Cooper, D.; Frenck, R.W.; Hammitt, L. L.; Türeci, ̈ O.; Nell, H.; Schaefer, A.; Ünal, S.; Tresnan, D. B.; Mather, S.; Dormitzer, P. R.; -Sahin, U.; Jansen, K. U.; Gruber, W. C. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar]

- Houseley, J.; Tollervey, D. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell 2009, 136, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisby, T.; Yilmazer, A.; Kostarelos, K. Reasons for success and lessons learnt from nanoscale vaccines against COVID-19. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crommelin, D. J. A.; Anchordoquy, T. J.; Volkin, D. B.; Jiskoot, W.; Mastrobattista, E. Addressing the Cold Reality of mRNA Vaccine Stability. J Pharm Sci. 2021, 110, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedifard, F,; Chakravarthy, K. Nanomedicine for COVID-19: the role of nanotechnology in the treatment and diagnosis of COVID-19. Emergent Mater. 2021, 4, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselmo, A. C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: An update. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2019, 4, e10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, O. S.; Olafson, K. N.; Pillai, P. S.; Mitchell. M. J.; Langer, R. Advances in Biomaterials for Drug Delivery. Adv Mater. 2018, 30, e1705328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, D.; Robinson, K. J.; Islam, J.; Thurecht, K. J.; Corrie, S. R. Nanoparticle-Based Medicines: A Review of FDA-Approved Materials and Clinical Trials to Date. Pharm. Res. 2016, 33, 2373–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Chan, G.; Hu, Y.; Hu, H.; Ouyang, D. A Comprehensive Map of FDA-Approved Pharmaceutical Products. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K. R.; Maceren, J. P.; Strand, A. I.; He, B.; Overby, C.; Benoit, D. S. W. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 2513–2518. 10.

- Bungenberg de Jong, H. G.; Kruyt, H. R. Coacervation (Partial Miscibility in Colloid Systems). Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. 1929, 32, 849–856. [Google Scholar]

- Hofs, B.; Voets, I. K.; De Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Comparison of Complex Coacervate Core Micelles from Two Diblock Copolymers or a Single Diblock Copolymer with a Polyelectrolyte. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 4242–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Formation of Polyion Complex Micelles in an Aqueous Milieu from a Pair of Oppositely-Charged Block Copolymers with Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Segments. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 5294–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voets, I. K.; de Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Complex Coacervate Core Micelles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 147–148, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pergushov, D. V.; Müller, A. H. E.; Schacher, F. H. Micellar Interpolyelectrolyte Complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6888–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cingil, H. E.; Boz, E. B.; Wang, J.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Sprakel, J. Probing Nanoscale Coassembly with Dual Mechanochromic Sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Burgh, S.; de Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Complex Coacervation Core Micelles. Colloidal Stability and Aggregation Mechanism. Langmuir 2004, 20, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ko, N. R.; Oh, J. K. Recent Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Degradable Block Copolymer Micelles: Synthesis and Controlled Drug Delivery Applications. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2012, 48, 7542–7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, C.; Ha, T.-L.; Kim, E.; Jeong, S.W.; Lee, S.G.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, H.-C. Bioreducible Micelles Self-Assembled from Poly(ethylene glycol)-Cholesteryl Conjugate As a Drug Delivery Platform. Polymers 2015, 7, 2245–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, L.; Xiao, C.; Chen, L.; Zhuang, X.; Chen, X. Noncovalent interaction-assisted polymeric micelles for controlled drug delivery. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11274–11290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Kumari, P.; Lakhani, P. M.; Ghosh, B. Recent advances in polymeric micelles for anti-cancer drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 83, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Fukushima, S.; Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Design of environment-sensitive supramolecular assemblies for intracellular drug delivery: polymeric micelles that are responsive to intracellular pH change. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003, 42, 4640–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayose, S.; Kataoka, K. Water-soluble polyion complex associates of DNA and poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(L-lysine) block copolymer. Bioconjug. Chem. 1997, 8, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, H.; Miyata, K.; Osada, K.; Kataoka, K. Block Copolymer Micelles in Nanomedicine Applications. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6844–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukerabigwi, J. F.; Ge, Z.; Kataoka, K. Therapeutic nanoreactors as in vivo nanoplatforms for cancer therapy. Chem.-Eur. J. 2018, 24, 15706–15724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciotti, C.; Saggiomo, V.; Bunschoten, A.; ten Hove, J. B.; Rood, M. T. M.; van Leeuwen, F. W. B.; Velders, A. H. Assembly, Disassembly and Reassembly of Complex Coacervate Core Micelles with Redox-Responsive Supramolecular Cross-Linkers. ChemSystemsChem. 2020, 2, e1900032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orilall, M. C.; Wiesner, U. Block copolymer based composition and morphology control in nanostructured hybrid materials for energy conversion and storage: solar cells, batteries, and fuel cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwars, T.; Paetzold, E.; Oehme, G. Reactions in micellar systems. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005, 44, 7174–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, K. PEO-related block copolymer surfactants oids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001, 183-185, 277-292.

- Kataoka K, Harada A, Nagasaki Y. Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: design, characterization and biological significance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 47, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullagh, M.; Prytkova, T.; Tonzani, S.; Winter, N. D.; Schatz, G. C. Modeling Self-Assembly Processes Driven by Nonbonded Interactions in Soft Materials. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 10388–10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliloglu, T.; Bahar, I.; Erman, B.; Mattice, W. L. Mechanisms of the Exchange of Diblock Copolymers between Micelles at Dynamic Equilibrium. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 4764–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mattice, W. L.; Napper, D. H. Simulation of the Formation of Micelles by Diblock Copolymers under Weak Segregation. Langmuir 1993, 9, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gennes, P. G. Scaling theory of polymer adsorption. J. Phys. (Paris) 1976, 37, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gennes, P. G. Conformation of Polymers Attached to an Interface. Macromolecules 1980, 13, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, A. Polymeric Micelles: A Star Model. Macromolecules 1987, 20, 2943–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noolandi, J.; Hong, K. M. Theory of Block Copolymer Micelles in Solution. Macromolecules 1983, 16, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibler, L.; Orland, H.; Wheeler, J. C. Theory of critical micelle concentration for solutions of block copolymers. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 3550–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pépin, M. P.; Whitmore, M. D. Monte Carlo and Mean Field Study of Diblock Copolymer Micelles. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 8644–8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, L.; Corti, M.; Salina, P. Direct measurement of the formation time of mixed micelles. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 5981–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.-Y.; Davis, H. T.; Bates, F. S. Molecular Exchange in PEO-PB Micelles in Water. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, R.; Willner, L.; Richter, D.; Dormidontova, E. E. Equilibrium Chain Exchange Kinetics of Diblock Copolymer Micelles: Tuning and Logarithmic Relaxation. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 4566–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, C. E.; Perry, S. L. Recent progress in the science of complex coacervation. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 2885–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Schlenoff, J. B. Driving Forces for Oppositely Charged Polyion Association in Aqueous Solutions: Enthalpic, Entropic, but Not Electrostatic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marras, A. E.; Ting, J. M.; Stevens, K. C.; Tirrell, M. V. Advances in the Structural Design of Polyelectrolyte Complex Micelles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2021, 125, 7076–7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumyantsev, A. M.; Zhulina, E. B.; Borisov, O.V. ; Zhulina, E. B.; Borisov O.V. Scaling Theory of Complex Coacervate Core Micelles. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 7–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproncken, C. C. M.; Magana, J. R.; Voets, I. K. 100th Anniversary of Macromolecular Science Viewpoint: Attractive Soft Matter: Association Kinetics, Dynamics, and Pathway Complexity in Electrostatically Coassembled Micelles. ACS Macro Lett. 2021, 10, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magana, J. R.; Sproncken, C. C. M.; Voets, I. K. On Complex Coacervate Core Micelles: Structure-Function Perspectives. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggleman, R. A.; Kumar, R.; Fredrickson, G. H. Investigation of the interfacial tension of complex coacervates using field-theoretic simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 024903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabanov, A. V.; Bronich, T. K.; Kabanov, V. A.; Yu, K.; Eisenberg, A. Soluble stoichiometric complexes from poly(N-ethyl-4- vinylpyridinium) cations and poly(ethylene oxide)-block-polymetha- crylate anions. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 6797–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; de Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Drechsler, M.; Besseling, N. A. M. Stability of complex coacervate core micelles containing metal coordination polymer. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 10908–10914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; de Keizer, A.; Fokkink, R.; Yan, Y.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; van der Gucht, J. Complex coacervate core micelles from iron-based coordination polymers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 8313–8319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaucher, G.; Dufresne, M.-H.; Sant, V. P.; Kang, N.; Maysinger, D.; Leroux, J.-C. Block copolymer micelles: preparation, characterization and application in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2005, 109, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarenko, E.Y.; Khokhlov, A.R.; Reineker, P. Stoichiometric polyelectrolyte complexes of ionic block copolymers and oppositely charged polyions. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 194902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, B.; Liu, X.; An, Y.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; Shi, L. Pyranine- induced micellization of poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(4-vinyl- pyridine) and pH-triggered release of pyranine from the complex micelles. Langmuir 2007, 23, 7498–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmers, M.; Voets, I. K.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; van der Gucht, J. Transient network topology of interconnected polyelectrolyte complex micelles. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Formation of stable and monodispersive polyion complex micelles in aqueous medium from poly(L-lysine) and poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(aspartic acid) block copolymer. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A. 1997, 34, 2119–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautzenberg, H.; Rother, G. Response of polyelectrolyte complexes to subsequent addition of sodium chloride: time-dependent static light scattering studies. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2004, 205, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matralis, A.; Sotiropoulou, M.; Bokias, G.; Staikos, G. Water- soluble stoichiometric polyelectrolyte complexes based on cationic comb-type copolymers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2006, 207, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Akiyama, Y.; Yamasaki, Y.; Kataoka, K. Preparation and characterization of polyion complex micelles with a novel thermosensitive poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline) shell via the complexation of oppositely charged block ionomers. Langmuir 2007, 23, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pispas, S. Complexes of polyelectrolyte-neutral double hydrophilic block copolymers with oppositely charged surfactant and polyelectrolyte. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 8351–8359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindhoud, S.; Voorhaar, L.; de Vries, R.; Schweins, R.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Norde, W. Salt-induced disintegration of lysozyme- containing polyelectrolyte complex micelles. Langmuir 2009, 25, 11425–11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, G. M. Polysaccharide-Based Polyion Complex Micelles as New Delivery Systems for Hydrophilic Cationic Drugs. Ph.D. thesis, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Montreal, 09; pp 1-258. 20 August.

- Brzozowska, A.; Zhang, Q.; de Keizer, A.; Norde, W.; Cohen Stuart, M. Reduction of protein adsorption on silica and polysulfone surfaces coated with complex coacervate core micelles with poly(vinyl alcohol) as a neutral brush forming block. Colloids Surf. A 2010, 368, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowska, A.; de Keizer, A.; Christophe, D.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Norde, W. Grafted ionomer complexes and their effect on protein adsorption on silica and polysulfone surfaces. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 1621–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danial, M.; Klok, H.-A.; Norde, W.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Complex coacervate core micelles with a lysozyme-modified corona. Langmuir 2007, 23, 8003–8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhoud, S.; de Vries, R.; Schweins, R.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Norde, W. Salt-induced release of lipase from polyelectrolyte complex micelles. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, J. T.; Voorn, M. J. Phase separation in polyelectrolyte solutions; theory of complex coacervation. J. Cell Physiol. Suppl. 1957, 49 (Suppl. 1), 7–22; discussion, 22-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, J. N.; Feldman, K. E.; Lynd, N. A.; Deek, J.; Campos, L. M.; Spruell, J. M.; Hernandez, B. M.; Kramer, E. J.; Hawker, C. J. Tunable, high modulus hydrogels driven by ionic coacervation. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 2327–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capito, R. M.; Azevedo, H. S.; Velichko, Y. S.; Mata, A.; Stupp, S. I. Self-assembly of large and small molecules into hierarchically ordered sacs and membranes. Science 2008, 319, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakizawa, Y.; Kataoka, K. Block copolymer micelles for delivery of gene and related compounds. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2002, 54, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Supramolecular assemblies of block copolymers in aqueous media as nanocontainers relevant to biological applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 949–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holappa, S.; Kantonen, L.; Andersson, T.; Winnik, F.; Tenhu, H. Overcharging of polyelectrolyte complexes by the guest polyelectrolyte studied by fluorescence spectroscopy. Langmuir 2005, 21, 11431–11438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolles, A.; Hooiveld, E.; Westphal, A. H.; van Berkel, W. J.; Kleijn, J. M.; Borst, J. W. FRET Reveals the Formation and Exchange Dynamics of Protein-Containing Complex Coacervate Core Micelles. Langmuir 2018, 34, 12083–12092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M.; Diget, J. S.; Lyngsø, J.; Pedersen, J. S.; Narayanan, T.; Lund, R. Kinetic Pathways for Polyelectrolyte Coacervate Micelle Formation Revealed by Time-Resolved Synchrotron SAXS. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 8227–8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, I.; Sprakel, J. Langevin Dynamics Simulations of the Exchange of Complex Coacervate Core Micelles: The Role of Nonelectrostatic Attraction and Polyelectrolyte Length. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 8923–8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ting, J. M.; Tirrell, M. V. Mechanism of Dissociation Kinetics in Polyelectrolyte Complex Micelles. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berret, J.-F.; Cristobal, G.; Herve,́ P. ; Oberdisse, J.; Grillo, I. Structure of colloidal complexes obtained from neutral/polyelectrolyte copolymers and oppositely charged surfactants. Eur. Phys. J. E Soft Matter 2002, 9, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ting, J. M.; Werba, O.; Meng, S.; Tirrell, M. V. Non- equilibrium phenomena and kinetic pathways in self-assembled polyelectrolyte complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 163330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofs, B.; De Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. On the stability of (highly aggregated) polyelectrolyte complexes containing a charged- block-neutral diblock copolymer. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 5621–5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindhoud, S.; Norde, W.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Reversibility and relaxation behavior of polyelectrolyte complex micelle formation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 5431–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, I.; Terenzi, C.; Sprakel, J. Chemical Feedback in Templated Reaction-Assembly Networks. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 10675–10685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormidontova, E. E. Micellization kinetics in block copolymer solutions: Scaling model. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 7630–7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, R.; Willner, L.; Stellbrink, J.; Lindner, P.; Richter, D. Logarithmic chain-exchange kinetics of diblock copolymer micelles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 068302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Lodge, T. P.; Bates, F. S. Mechanism of molecular exchange in diblock copolymer micelles: hypersensitivity to core chain length. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 047802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, T.; Willner, L.; Lund, R.; Pipich, V.; Richter, D. Equilibrium exchange kinetics in n-alkyl-PEO polymeric micelles: single exponential relaxation and chain length dependence. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Choi, S.; Bates, F.; Lodge, T. Molecular exchange in diblock copolymer micelles: bimodal distribution in core-block molecular weights. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Bates, F.; Lodge, T. Chain exchange in binary copolymer micelles at equilibrium: confirmation of the independent chain hypothesis. ACS Macro Lett. 2013, 2, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Lu, J.; Bates, F. S.; Lodge, T. P. Effect of corona block length on the structure and chain exchange kinetics of block copolymer micelles. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 3563–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, I.; Timmerman, M.; Sprakel, J. FRET-Based Determination of the Exchange Dynamics of Complex Coacervate Core Micelles. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenov. A. N. Contribution to the theory of microphase layering in block-copolymer melts. Sov. Phys. JETP 1985, 61, 733–742. [Google Scholar]

- Borisov, O. V.; Zhulina, E. B.; Leermakers, F. A. M.; Müller, A. H. E. Self-Assembled Structures of Amphiphilic Ionic Block Copolymers: Theory, Self-Consistent Field Modeling and Experiment. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2011, 241, 57–129. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij, H. M.; Spruijt, E.; Voets, I. K.; Fokkink, R.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; van der Gucht, J. . On the Stability and Morphology of Complex Coacervate Core Micelles: From Spherical to Wormlike Micelles Langmuir 2012, 28 (40), 14180-14191.

- Lueckheide, M. , Vieregg, J. R.; Bologna, A. J.; Leon, L.; Tirrell, M. V. Structure-property relationships of oligonucleotide polyelectrolyte complex micelles. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7111–7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, M.; Zanchetta, G.; Chapman, B. D.; Jones, C. D.; Cross, J. O.; Pindak, R.; Bellini, T.; Clark, N. A. End-to-end stacking and liquid crystal condensation of 6 to 20 base pair DNA duplexes. Science 2007, 318, 1276–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumyantsev A., M. , de Pablo J. J., Liquid crystalline and isotropic coacervates of semiflexible polyanions and flexible polycations. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5140–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, A.; Guibert, C.; Olijve, L. L. C.; Voets, I. K. Morphological Evolution of Complex Coacervate Core Micelles Revealed by iPAINT Microscopy. Polymer 2016, 107, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.; Girard, M.; King, J. T.; De La Cruz, M. O. Role of Chain Flexibility in Asymmetric Polyelectrolyte Complexation in Salt Solutions. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocher McTigue, W. C.; Perry, S. L. Protein Encapsulation Using Complex Coacervates: What Nature Has to Teach Us. Small 2020, 16, e1907671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Polyion Complex Micelle Formation from Double-Hydrophilic Block Copolymers Composed of Charged and Non-Charged Segments in Aqueous Media. Polym. J. 2018, 50, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.S. Complex Coacervate-Based Materials for Biomedicine: Recent Advancements and Future Prospects. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 5414–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J. M.; Kapelner, R. A.; Obermeyer, A. C. Macro- and Microphase Separated Protein-Polyelectrolyte Complexes: Design Parameters and Current Progress. Polymers (Basel, Switz.) 2019, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Stenzel, M. H. Polyion Complex Micelles for Protein Delivery. Aust. J. Chem. 2018, 71, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Batys, P.; O’Neal, J. T.; Li, F.; Sammalkorpi, M.; Lutkenhaus, J. L. Molecular Origin of the Glass Transition in Polyelectrolyte Assemblies. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gineste, S.; Di Cola, E.; Amouroux, B.; Till, U.; Marty, J.-D.; Mingotaud, A.-F.; Mingotaud, C.; Violleau, F.; Berti, D.; Parigi, G.; Luchinat, C.; Balor, S.; Sztucki, M.; Lonetti, B. Mechanistic Insights into Polyion Complex Associations. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathee, V. S.; Sidky, H.; Sikora, B. J.; Whitmer, J. K. Role of Associative Charging in the Entropy-Energy Balance of Polyelectrolyte Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15319–15328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P. S.; Samanta, A.; Mukherjee, M.; Roy, B.; Mukherjee, A. Designing Novel pH-Induced Chitosan-Gum Odina Complex Coacervates for Colon Targeting. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 15728–15745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemoto, H.; Miyata, K.; Hattori, S.; Ishii, T.; Suma, T.; Uchida, S.; Nishiyama, N.; Kataoka, K. Acidic PH-Responsive SiRNA Conjugate for Reversible Carrier Stability and Accelerated Endosomal Escape with Reduced IFNα-Associated Immune Response. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6218–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gucht, J.; Spruijt, E.; Lemmers, M.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Polyelectrolyte Complexes: Bulk Phases and Colloidal Systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 361, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapert, H. R.; Nishiyama, N.; Jiang, D. L.; Aida, T.; Kataoka, K. Polyion Complex Micelles Encapsulating Light-Harvesting Ionic Dendrimer Zinc Porphyrins. Langmuir 2000, 16, 8182–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadman, K.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Keshavarz, B.; Jiang, Z.; Shull, K. R. Influence of Hydrophobicity on Polyelectrolyte Complexation. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 9417–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kruif, C. G.; Weinbreck, F.; De Vries, R. Complex Coacervation of Proteins and Anionic Polysaccharides. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 9, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. E.; Obermeyer, A.; Dong, X.; Walker, J.; Olsen, B. D. Complex Coacervate Core Micelles for the Dispersion and Stabilization of Organophosphate Hydrolase in Organic Solvents. Langmuir 2016, 32, 13367–13376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Zhou, J.; Pan, W.; Li, Z.; Liang, D. Assembly and Reassembly of Polyelectrolyte Complex Formed by Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Block-Poly(Glutamate Sodium) and S5R4 Peptide. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 4627–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, H.; Cheng, Y. Surface-Engineered Dendrimers in Gene Delivery. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 5274–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Shi, L.; Zhang, W.; An, Y.; Zhu, X.-X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z. Formation of Hybrid Micelles between Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Block- Poly(4-Vinylpyridinium) Cations and Sulfate Anions in an Aqueous Milieu. Soft Matter 2005, 1, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, N.; Bouyer, F.; Destarac, M.; In, M.; Gérardin, C. Hybrid Polyion Complex Micelles Formed from Double Hydrophilic Block Copolymers and Multivalent Metal Ions: Size Control and Nanostructure. Langmuir 2012, 28, 3773–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, N.; Prévost, S.; Schweins, R.; Houston, J. E.; Morfin, I.; Huber, K. Invertible Micelles Based on Ion-Specific Interactions of Sr2+ and Ba2+ with Double Anionic Block Copolyelectrolytes. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 8759–8770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciotti, C.; Saggiomo, V.; van Hurne, S.; Bunschoten, A.; Kaup, R.; Velders, A. H. Oxidant-Responsive Ferrocene-Based Cyclodextrin Complex Coacervate Core Micelles. Supramol. Chem. 2020, 32, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Dell, E. J.; Freyer, J. L.; Campos, L. M.; Jang, W. D. Polymeric Supramolecular Assemblies Based on Multivalent Ionic Interactions for Biomedical Applications. Polymer 2014, 55, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Holkar, A.; Srivastava, S. Protein-Polyelectrolyte Complexes and Micellar Assemblies. Polymers (Basel, Switz.) 2019, 11, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. E.; Sizovs, A.; Grandinetti, G.; Xue, L.; Reineke, T. M. Diblock Glycopolymers Promote Colloidal Stability of Polyplexes and Effective PDNA and siRNA Delivery under Physiological Salt and Serum Conditions. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3015–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Zha, Y.; Feng, B.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Sun, X.; Ren, J.; Zhang, C.; Shao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, X. PEGylated Poly(2- (Dimethylamino) Ethyl Methacrylate)/DNA Polyplex Micelles Decorated with Phage-Displayed TGN Peptide for Brain-Targeted Gene Delivery. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2117–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Karls, L.; Lodge, T. P.; Reineke, T. M. Polycation Architecture and Assembly Direct Successful Gene Delivery: Micelleplexes Outperform Polyplexes via Optimal DNA Packaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15804–15817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, S.; Diociaiuti, M.; Cametti, C.; Masci, G. Hyaluronic Acid and Alginate Covalent Nanogels by Template Cross-Linking in Polyion Complex Micelle Nanoreactors. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Lee, S. H.; Lee, S.; Choi, S. H.; Hawker, C. J.; Kim, B. S. Highly Stable Au Nanoparticles with Double Hydrophilic Block Copolymer Templates: Correlation Between Structure and Stability. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 4528–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogstad, D. V.; Choi, S. H.; Lynd, N. A.; Audus, D. J.; Perry, S. L.; Gopez, J. D.; Hawker, C. J.; Kramer, E. J.; Tirrell, M. V. Small Angle Neutron Scattering Study of Complex Coacervate Micelles and Hydrogels Formed from Ionic Diblock and Triblock Copolymers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 13011–13018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortony, J. H.; Choi, S. H.; Spruell, J. M.; Hunt, J. N.; Lynd, N. A.; Krogstad, D. V.; Urban, V. S.; Hawker, C. J.; Kramer, E. J.; Han, S. Fluidity and Water in Nanoscale Domains Define Coacervate Hydrogels. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Fares, H. M.; Schlenoff, J. B. Ion-Pairing Strength in Polyelectrolyte Complexes. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingil, H. E.; Meertens, N. C. H.; Voets, I. K. Temporally Programmed Disassembly and Reassembly of C3Ms. Small 2018, 14, e1802089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, H.; Liu, G.; Ma, R.; An, Y.; Kong, D.; Shi, L. pH/Sugar Dual Responsive Core-Cross-Linked PIC Micelles for Enhanced Intracellular Protein Delivery. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3434–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Besseling, N. A. M.; Fokkink, R. G. Formation of Micelles with Complex Coacervate Cores. Langmuir 1998, 14, 6846–6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voets, I. K.; De Vries, R.; Fokkink, R.; Sprakel, J.; May, R. P.; De Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Towards a Structural Characterization of Charge-Driven Polymer Micelles. Eur. Phys. J. E: Soft Matter Biol. Phys. 2009, 30, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresnais, J.; Lavelle, C.; Berret, J. F. Nanoparticle Aggregation Controlled by Desalting Kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 16371–16379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Fresnais, J.; Berret, J. F.; Castaing, J. C.; Destremaut, F.; Salmon, J. B.; Cousin, F.; Chapel, J. P. Influence of the Formulation Process in Electrostatic Assembly of Nanoparticles and Macromolecules in Aqueous Solution: The Interaction Pathway. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 16373–16381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Fresnais, J.; Berret, J. F.; Castaing, J. C.; Grillo, I.; Chapel, J. P. Influence of the Formulation Process in Electrostatic Assembly of Nanoparticles and Macromolecules in Aqueous Solution: The Mixing Pathway. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 12870–12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocher McTigue, W. C.; Voke, E.; Chang, L.-W.; Perry, S. L. The Benefit of Poor Mixing: Kinetics of Coacervation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 20643–20657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voets, I. K. Electrostatically Driven Assembly of Polyelectrolytes. In: Fluorescence Studies of Polymer Containing Systems; Procházka, K., Ed.; Springer Series on Fluorescence, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016; Vol 16, pp 65-89. [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Zheng, M.; Tao, W.; Chung, R.; Jin, D.; Ghaffari, D.; Farokhzad, O. C. Challenges in DNA Delivery and Recent Advances in Multifunctional Polymeric DNA Delivery Systems. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 2231–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S.; Kataoka, K. Design concepts of polyplex micelles for in vivo therapeutic delivery of plasmid DNA and messenger RNA. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2019, 107, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka K, Harada A, Nagasaki Y: Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: design, characterization and biological significance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 37–48. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, C.; Brohlin, O.; Shahrivarkevishahi, A.; Gassensmith, J. J. Virus like Particles: Fundamental Concepts, Biological Interactions, and Clinical Applications. Chung E. J., Leon L., Rinaldi C., Eds.; Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Chapter 11, pp. 153-174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tockary, T. A.; Osada, K.; Chen, Q.; Machitani, K.; Dirisala, A.; Uchida, S.; Nomoto, T.; Toh, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Itaka, K.; Nitta, K.; Nagayama, K.; Kataoka, K. Tethered Peg Crowdedness Determining Shape and Blood Circulation Profile of Polyplex Micelle Gene Carriers. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 6585–6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, T.; Sugawara, K.; Tanaka, K.; Horiuchi, S.; Takashima, Y.; Okada, H. Suppression of tumor growth by systemic delivery of anti-VEGF siRNA with cell-penetrating peptide-modified MPEG-PCL nanomicelles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 81, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. H.; Kim, S. W.; Park, T. G. A new antisense oligonucleotide delivery system based on self-assembled ODN-PEG hybrid conjugate micelles. J. Control Release 2003, 93, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindhoud, S.; de Vries, R.; Norde, W.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Structure and stability of complex coacervate core micelles with lysozyme. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2219–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, M.; Nagasaki, Y.; Itaka, K.; Nishiyama, N.; Kataoka, K. Lactosylated poly(ethylene glycol)-siRNA conjugate through acid- labile β-thiopropionate linkage to construct pH-sensitive polyion complex micelles achieving enhanced gene silencing in hepatoma cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1624–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Ishii, T.; Kim, H. J.; Nishiyama, N.; Hayakawa, Y.; Itaka, K.; Kataoka, K. Efficient delivery of bioactive antibodies into the cytoplasm of living cells by charge-conversional polyion complex micelles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010, 49, 2552–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, W.-D.; Nakagishi, Y.; Nishiyama, N.; Kawauchi, S.; Morimoto, Y.; Kikuchi, M.; Kataoka, K. Polyion complex micelles for photodynamic therapy: incorporation of dendritic photosensitizer excitable at long wavelength relevant to improved tissue-penetrating property. J. Controlled Release 2006, 113, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Besseling, N. A. M.; de Keizer, A.; Marcelis, A.; Drechsler, M.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Hierarchical self-assembly in solutions containing metal ions, ligand, and diblock copolymer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007, 46, 1807–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Dragan, S. Nonstoichiometric interpolyelectrolyte complexes as colloidal dispersions based on NaPAMPS and their interaction with colloidal silica particles. Macromol. Symp. 2004, 210, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Burgh, S.; Fokkink, R.; de Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Complex coacervation core micelles as anti-fouling agents on silica and polystyrene surfaces. Colloids Surf. A 2004, 242, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowska, A.; Hofs, B.; de Keizer, A.; Fokkink, R.; Cohen Stuart, M.; Norde, W. Reduction of protein adsorption on silica and polystyrene surfaces due to coating with complex coacervate core micelles. Colloids Surf. A 2009, 347, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkle, S.; McNeil, S. E.; Mühlebach, S.; Bawa, R.; Borchard, G.; Barenholz, Y. C.; Tamarkin, L.; Desai, N. Nanomedicines: addressing the scientific and regulatory gap. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1313, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, B. Have nanomedicines progressed as much as we'd hoped for in drug discovery and development? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krukemeyer, M. G.; Krenn, V.; Huebner, F.; Wagner, W.; Resch, R. History and Possible Uses of Nanomedicine Based on Nanoparticles and Nanotechnological Progress. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 1000336. [Google Scholar]

- Decuzzi, P.; Peer, D.; Mascolo, D. D.; Palange, A. L.; Manghnani, P. N.; Moghimi, S. M.; Farhangrazi, Z. S.; Howard, K. A.; Rosenblum, D.; Liang, T.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J. J.; Gu, Z.; Korin, N.; Letourneur, D.; Chauvierre, C.; van der Meel, R.; Kiessling, F.; Lammers, T. Roadmap on nanomedicine. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicha, I.; Chauvierre, C.; Texier, I.; Cabella, C.; Metselaar, J. M.; Szebeni, J.; Dézsi, L.; Alexiou, C.; Rouzet, F.; Storm, G.; Stroes, E.; Bruce, D.; MacRitchie, N.; Maffia, P.; Letourneur, D. From design to the clinic: practical guidelines for translating cardiovascular nanomedicine. Cardiovasc Res. 2018, 114, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Shi, Y.; Qi, T.; Qiu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Q.; Lin, G. Precise design strategies of nanomedicine for improving cancer therapeutic efficacy using subcellular targeting. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhise, K.; Sau, S.; Alsaab, H.; Kashaw, S. K.; Tekade, R. K.; Iyer, A. K. Nanomedicine for cancer diagnosis and therapy: advancement, success and structure-activity relationship. Ther. Deliv. 2017, 8, 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchione, M. A.; Aristizabal Bedoya, D.; Figueroa, F. N.; Munoz-Fernandez, M. A.; Strumia, M. C. Nanosystems applied to HIV infection: Prevention and treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binda, A.; Murano, C.; Rivolta, I. Innovative Therapies and Nanomedicine Applications for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease: A State-of-the-Art (2017-2020). Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 6113–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Khang, D. Past, Present, and Future of Anticancer Nanomedicine. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2020, 15, 5719–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desland, F. A.; Hormigo, A. The CNS and the Brain Tumor Microenvironment: Implications for Glioblastoma Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H. S.; Muresanu, D. F.; Castellani, R. J.; Nozari, A.; Lafuente, J. V.; Tian, Z. R.; Sahib, S.; Bryukhovetskiy, I.; Bryukhovetskiy, A.; Buzoianu, A. D.; Patnaik, R; Wiklund, L. ; Sharma, A. Pathophysiology of blood-brain barrier in brain tumor. Novel therapeutic advances using nanomedicine. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2020, 151, 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, E. A.; Furnari, F. B.; Bachoo, R. M.; Rowitch, D. H.; Louis, D. N.; Cavenee, W. K.; DePinho, R. A. Malignant glioma: genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 1311–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R. , Hegi, M. E., Mason, W. P., van den Bent, M. J., Taphoorn, M. JB., Janzer, R. C., Ludwin, S. K., Allgeier, A., Fisher, B., Belanger, K., Hau, P., Brandes, A. A., Gijtenbeek, J., Marosi, C., Vecht, C. J., Mokhtari, K., Wesseling, P., Villa, S., Eisenhauer, E., Gorlia, T.; Weller, M.; Lacombe, D.; Gregory Cairncross, J.; Mirimanoff, R. O. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Hau, P.; Fabel, K.; Baumgart, U.; Rümmele, P.; Grauer, O.; Bock, A.; Dietmaier, C.; Dietmaier, W.; Dietrich, J.; Dudel, C.; Hübner, F.; Jauch, T.; Drechsel, E.; Kleiter, I.; Wismeth, C.; Zellner, A.; Brawanski, A.; Steinbrecher, A.; Marienhagen, J.; Bogdahn, U. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-efficacy in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Cancer 2004, 100, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H. S.; Prados, M. D.; Wen, P. Y.; Mikkelsen, T.; Schiff, D.; Abrey, L. E.; Yung, W. K.; Paleologos, N.; Nicholas, M. K.; Jensen, R.; Vredenburgh, J.; Huang, J.; Zheng, M.; Cloughesy, T. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4733–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, M.; Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Martin, J.; Warnke, P.; Menei, P.; Eckland, D.; Kinley, J.; Kay, R.; Ram, Z.; ASPECT Study Group. Adenovirus-mediated gene therapy with sitimagene ceradenovec followed by intravenous ganciclovir for patients with operable high-grade glioma (ASPECT): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zustovich, F.; Landi, L.; Lombardi, G.; Porta, C.; Galli, L.; Fontana, A.; Amoroso, D.; Galli, C.; Andreuccetti, M.; Falcone, A.; Zagonel, V. Sorafenib plus daily low-dose temozolomide for relapsed glioblastoma: a phase II study. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 3487–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunwar, S.; Chang, S.; Westphal, M.; Vogelbaum, M.; Sampson, J.; Barnett, G.; Shaffrey, M.; Ram, Z.; Piepmeier, J.; Prados, M.; Croteau, D.; Pedain, C.; Leland, P.; Husain, S. R.; Joshi, B. H.; Puri, R. K.; PRECISE Study Group. Phase III randomized trial of CED of IL13-PE38QQR vs Gliadel wafers for recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010, 12, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, E.; Bienemann, A.; Taylor, H.; Hopkins, K.; Cameron, A.; Gill, S. A phase I trial of carboplatin administered by convection-enhanced delivery to patients with recurrent/progressive glioblastoma multiforme. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2012, 33, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S. B.; Amiji, M. M. A review of nanocarrier-based CNS delivery systems. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2006, 3, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Nakamura, H.; Maeda, H. The EPR effect: Unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraglia, M.; Addeo, R.; Costanzo, R.; Montella, L.; Faiola, V.; Marra, M.; Abbruzzese, A.; Palmieri, G.; Budillon, A.; Grillone, F.; Venuta, S.; Tagliaferri, P.; Del Prete, S. Phase II study of temozolomide plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the treatment of brain metastases from solid tumours. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2006, 57, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, C. P.; Schmid, C.; Gorlia, T.; Kleinletzenberger, C.; Beier, D.; Grauer, O.; Steinbrecher, A.; Hirschmann, B.; Brawanski, A.; Dietmaier, C.; Jauch-Worley, T.; Kölbl, O.; Pietsch, T.; Proescholdt, M.; Rümmele, P.; Muigg, A.; Stockhammer, G.; Hegi, M.; Bogdahn, U.; Hau, P. RNOP-09: pegylated liposomal doxorubicine and prolonged temozolomide in addition to radiotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma-a phase II study. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northfelt, D. W.; Dezube, B. J.; Thommes, J. A.; Miller, B. J.; Fischl, M. A.; Friedman-Kien, A.; Kaplan, L. D.; Du Mond, C.; Mamelok, R. D.; Henry, D. H. Pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: results of a randomized phase III clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 2445–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. N.; Tonda, M.; Sun, S.; Rackoff, W.; Doxil Study 30-49 Investigators. Long-term survival advantage for women treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with topotecan in a phase 3 randomized study of recurrent and refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 95, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, M. E. R.; Wigler, N.; Inbar, M.; Rosso, R.; Grischke, E.; Santoro, A.; Catane, R.; Kieback, D. G.; Tomczak, P.; Ackland, S. P.; Orlandi, F.; Mellars, L.; Alland, L.; Tendler, C.; CAELYX Breast Cancer Study Group. Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYX/Doxil) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, R. Z.; Nagler, A.; Sonneveld, P.; Bladé, J.; Hajek, R.; Spencer, A.; San Miguel, J.; Robak, T.; Dmoszynska, A.; Horvath, N.; Spicka, I.; Sutherland, H. J.; Suvorov, A. N.; Zhuang, S. H.; Parekh, T.; Xiu, L.; Yuan, Z.; Rackoff, W.; Harousseau, J. L. Randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus bortezomib compared with bortezomib alone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: combination therapy improves time to progression. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 3892–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaitan, D.; Reddy, P. L.; Ningaraj, N. Targeting Brain Tumors with Nanomedicines: Overcoming Blood Brain Barrier Challenges. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 13, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, C. J. Management of treatment-related toxicity in advanced ovarian cancer. Oncologist 2002, 7, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yallapu, M. M.; Jaggi, M.; Chauhan, S. C. Scope of nanotechnology in ovarian cancer therapeutics. J. Ovarian Res. 2010, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, C. L.; Roth, C. M. Nanoscale drug delivery systems for enhanced drug penetration into solid tumors: current progress and opportunities. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, D.; Karp, J. M.; Hong, S.; Farokhzad, O. C.; Margalit, R.; Langer, R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petros, R. A.; DeSimone, J. M. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L. R.; Lin, M. Z.; Zhong, H. H.; Cai, Y. J.; Li, B.; Xiao, Z. C.; Shuai, X. T. Nanodrug regulates lactic acid metabolism to reprogram the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 3892–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Z. P. MnO2-shelled Doxorubicin/Curcumin nanoformulation for enhanced colorectal cancer chemo-immunotherapy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 617, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han Y, Wen P, Li J, Kataoka K. Targeted nanomedicine in cisplatin-based cancer therapeutics. J. Control Release 2022, 345, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.; Nabi, B.; Javed, A.; Khan, T.; Iqubal, A.; Ansari, M. J.; Baboota, S.; Ali, J. Unraveling enhanced brain delivery of paliperidone-loaded lipid nanoconstructs: pharmacokinetic, behavioral, biochemical, and histological aspects. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1409–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, T.; Qin, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J.; Nice, E. C.; Xie, N.; Huang, C.; Shen, Z. Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles for cancer treatment using versatile targeted strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ye, Z.; Huang, C.; Qiu, M.; Song, D.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q. Lipid nanoparticle-mediated lymph node-targeting delivery of mRNA cancer vaccine elicits robust CD8+ T cell response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2207841119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V. K.; Chau, E.; Mishra, A.; DeAnda, A.; Hegde, V. L.; Sastry, J. K.; Haviland, D.; Jagannath, C.; Godin, B.; Khan, A. CD44 receptor targeted nanoparticles augment immunity against tuberculosis in mice. J. Control Release. 2022, 349, 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, J.; Thomas, R. K. Binding of sodium dodecyl sulfate with linear and branched polyethyleneimines in aqueous solution at different pH values. Langmuir 2006, 22, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kimura, K.; Dubin, P. L.; Jaeger, W. Polyelectrolyte−Micelle Coacervation: Effects of Micelle Surface Charge Density, Polymer Molecular Weight, and Polymer/Surfactant Ratio. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 3324–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kimura, K.; Huang, Q.; Dubin P., L.; Jaeger, W. Effects of Salt on Polyelectrolyte−Micelle Coacervation. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 7128–7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. S.; Park, S. W.; Hammond, P. T. Hydrogen-bonding layer-by-layer-assembled biodegradable polymeric micelles as drug delivery vehicles from surfaces. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, G.; Ma, Y.; Cui, Z.; Binks, B. P. Smart worm-like micelles responsive to CO₂/N₂ and light dual stimuli. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 2727–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Shin, E.; Kim, B. S. Light-responsive micelles of spiropyran initiated hyperbranched polyglycerol for smart drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Ketner A., M.; Heymann, R.; Kesselman, E.; Danino, D.; Falvey, D. E.; Raghavan, S. R. A Simple Route to Fluids with Photo-Switchable Viscosities Based on a Reversible Transition between Vesicles and Wormlike Micelles. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T. S.; Ketner, A. M.; Raghavan, S. R. Self-assembly of surfactant vesicles that transform into viscoelastic wormlike micelles upon heating. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6669–6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Chu, Z.; He, S.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Y. Thermally induced structural transitions from fluids to hydrogels with pH-switchable anionic wormlike micelles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 394, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezei, A.; Meszaros, R.; Varga, I.; Gilanyi, T. Effect of mixing on the formation of complexes of hyperbranched cationic polyelectrolytes and anionic surfactants. Langmuir 2007, 23, 4237–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappisi, L.; Leach, S. D.; Gradzielski, M. Precipitating polyelectrolyte–surfactant systems by admixing a nonionic surfactant – a case of cononsurfactancy. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 4988–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Eghtesadi, S. A.; Dawadi, M. B.; Wang, C.; Huang, S; Seymore, A. E.; Vogt, B. D.; Modarelli, D. A.; Liu, T.; Zacharia, N. S. Partitioning of Small Molecules in Hydrogen-Bonding Complex Coacervates of Poly(acrylic acid) and Poly(ethylene glycol) or Pluronic Block Copolymer. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3818–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K. A.; Priftis, D.; Perry, S. L.; Yip, J.; Byun, W. Y.; Tirrell, M. Protein Encapsulation via Polypeptide Complex Coacervation. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3, 1088–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Zacharia, N. S. Sequestration of Methylene Blue into Polyelectrolyte Complex Coacervates. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2016, 37, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Perriman, A. W.; Mann, S. Photocatalytic multiphase micro-droplet reactors based on complex coacervation. Chemical Communications 2015, 51, 8600–8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Liu, X. K.; Yuan, W. C.; Brown, L. J.; Wang, D. Y. Confined flocculation of ionic pollutants by Poly(l-dopa)-based polyelectrolyte complexes in hydrogel beads for three-dimensional, quantitative, efficient water decontamination. Langmuir 2015, 31, 6351–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Mazzawi, M.; Chen, K.; Sun, L.; Dubin, P. L. Protein purification by polyelectrolyte coacervation: influence of protein charge anisotropy on selectivity. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dora Tang, T. Y.; Rohaida Che Hak, C.; Thompson, A. J.; Kuimova, M. K.; Williams, D. S.; Perriman, A. W.; Mann, S. Fatty acid membrane assembly on coacervate microdroplets as a step towards a hybrid protocell model. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stano, P.; Luisi, P. L. Achievements and open questions in the self-reproduction of vesicles and synthetic minimal cells. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2010, 46, 3639–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, K.; Tamura, M.; Shohda, K.; Toyota, T.; Suzuki, K.; Sugawara, T. Self-reproduction of supramolecular giant vesicles combined with the amplification of encapsulated DNA. Nat Chem. 2011, 3, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansy, S. S.; Schrum, J. P.; Krishnamurthy, M.; Tobé, S.; Treco, D. A.; Szostak, J. W. Template-directed synthesis of a genetic polymer in a model protocell. Nature 2008, 454, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, B.; Price, A. D.; Chandrawati, R.; Hosta-Rigau, L.; Zelikin, A. N.; Caruso, F. Polymer hydrogel capsules: En route toward synthetic cellular systems. Nanoscale 2009, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Bai, S.; Ansorge-Schumacher, M. B.; Wang, D. Nanoparticle cages for enzyme catalysis in organic media. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 5694–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, A. B.; Wan, J.; Gopinath, A.; Stone, H. A. Semi-permeable vesicles composed of natural clay. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 2600–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisi, P. L.; Ferri, F.; Stano, P. Approaches to semi-synthetic minimal cells: a review. Naturwissenschaften 2006, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzieciol, A. J.; Mann, S. Designs for life: protocell models in the laboratory. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftis, D.; Farina, R.; Tirrell, M. Interfacial energy of polypeptide complex coacervates measured via capillary adhesion. Langmuir 2012, 28, 8721–8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhao, M.; Dawadi, M. B.; Cai, Y.; Lapitsky, Y.; Modarelli, D. A.; Zacharia, N. S. Effect of small molecules on the phase behavior and coacervation of aqueous solutions of poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) and poly(sodium 4-styrene sulfonate). J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 518, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitsky, Y.; Kaler, E. W. Surfactant and polyelectrolyte gel particles for encapsulation and release of aromatic oils. Soft Matter 2006, 2, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani-Bagha, A. R.; Holmberg, K. Solubilization of Hydrophobic Dyes in Surfactant Solutions. Materials (Basel) 2013, 6, 580–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani-Bagha, A. R.; Singh, R. G.; Holmberg, K. Solubilization of two organic water-insoluble dyes by anionic, cationic and nonionic surfactants. Colloid Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2013, 417, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalberg, K.; Lindman, B.; Karlstroem, G. Phase-behavior of systems of cationic surfactant and anionic polyelectrolyte: influence of surfactant chain-length and polyelectrolyte molecular-weight. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 3370–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Trabelsi, S.; Guillot, S.; McLoughlin, D.; Langevin, D.; Letellier, A. P.; Turmine, M. Critical Aggregation Concentration in Mixed Solutions of Anionic Polyelectrolytes and Cationic Surfactants. Langmuir 2004, 20, 8496–8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y. J.; Xia, J. L.; Dubin, P. L. Complex formation between polyelectrolyte and oppositely charged mixed micelles: Static and dynamic light scattering study of the effect of polyelectrolyte molecular weight and concentration. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 7049–7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin P., L.; Rigsbee, D. R.; Gan, L.; Fallon, M. A. Equilibrium Binding of Mixed Micelles to Oppositely Charged Polyelectrolytes. Macromolecules 1988, 21, 2555–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comert, F.; Nguyen, D.; Rushanan, M.; Milas, P.; Xu, A. Y.; Dubin, P. L. Precipitate–Coacervate Transformation in Polyelectrolyte–Mixed Micelle Systems. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017, 121, 4466–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, P. L.; Oteri, R. Association of polyelectrolytes with oppositely charged micelles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1983, 95, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, H.; Rigsbee, D. R.; Dubin, P. L.; Shaikh, T. Structural elucidation of soluble polyelectrolyte-micelle complexes: Intra- vs interpolymer association. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 2759–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kimura, K.; Huang, Q.; Dubin, P.L.; Jaeger, W. Effects of Salt on Polyelectrolyte−Micelle Coacervation. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 7128–7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuigg, D. W.; Kaplan, J. I.; Dubin, P. L. Critical conditions for the binding of polyelectrolytes to small oppositely charged micelles. J. Chem. Phy. 1992, 96, 1973–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, R.; Thompson, L.; Bos, M.; Varga, I.; Gilányi, T. Interaction of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate with Polyethyleneimine: Surfactant-Induced Polymer Solution Colloid Dispersion Transition. Langmuir 2003, 19, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezei, A.; Ábrahám, Á.; Pojják, K.; Mészáros, R. The impact of electrolyte on the aggregation of the complexes of hyperbranched poly(ethyleneimine) and sodium dodecylsulfate. Langmuir 2009, 25, 7304–7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, G.; Schwarz, S. Dye removal from solutions and sludges by using polyelectrolytes and polyelectrolyte-surfactant complexes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2006, 51, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Lee, M. W.; Woo, S. H. Adsorption of congo red by chitosan hydrogel beads impregnated with carbon nanotubes. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1800–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takae, S.; Miyata, K.; Oba, M.; Ishii, T.; Nishiyama, N.; Itaka, K.; Yamasaki, Y.; Koyama, H.; Kataoka, K. PEG-detachable polyplex micelles based on disulfide-linked block catiomers as bioresponsive nonviral gene vectors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6001–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S. Functional block copolymer assemblies responsive to tumor and intracellular microenvironments for site-specific drug delivery and enhanced imaging performance. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7289–7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Bu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, F.; Shen, H.; Wu, D. Facile construction of pH- and redox-responsive micelles from a biodegradable poly(β-hydroxyl amine) for drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zheng, M.; Meng, F.; Mickler, F. M.; Ruthardt, N.; Zhu, X.; Zhong, Z. Reversibly shielded DNA polyplexes based on bioreducible PDMAEMA-SS-PEG-SS-PDMAEMA triblock copolymers mediate markedly enhanced nonviral gene transfection. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Y.; Velders, A. H.; Gianolio, E.; Aime, S.; Vergeldt, F. J.; Van As, H.; Yan, Y.; Drechsler, M.; de Keizer, A.; Stuart, M. A. C.; van der Gucht, J. Controlled Mixing of Lanthanide(III) Ions in Coacervate Core Micelles. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 3736–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Groeneveld, A.; Oikonomou, M.; Prusova, A.; Van As, H.; van Lent, J.W.; Velders, A.H. Revealing and Tuning the Core, Structure, Properties and Function of Polymer Micelles with Lanthanide-coordination Complexes. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Huang, J.; de Keizer, A.; Cohen Stuart, M. A. Fluorescence enhancement by microphase separation-induced chain extension of Eu3+ coordination polymers: phenomenon and analysis. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 2720–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang. J.; Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Marcelis, A. T. M., Colomb-Delsuc, M.; Otto, S.; van der Gucht, J. Stable polymer micelles formed by metal coordination. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 7179–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hove, J. B.; Wang, J.; van Leeuwen, F. W. B.; Velders, A. H. Dendrimer-encapsulated Nanoparticle-core Micelles as a Modular Strategy for Particle-in-a-box-in-a-box Nanostructures. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 18619–18623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Voets, I. K.; Fokkink, R.; van der Gucht, J.; Velders, A. H. Controlling the Number of Dendrimers in Dendrimicelle Nanoconjugates from 1 to More than 100. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 7337–7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hove, J. B.; van Oosterom, M. N.; van Leeuwen, F. W. B.; Velders, A. H. Nanoparticles Reveal Extreme Size-Sorting and Morphologies in Complex Coacervate Superstructures. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13820–13827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciotti, C.; Saggiomo, V.; Bunschoten, A.; Fokkink, R.; Hove, J. B. T.; Wang, J.; Velders, A. H. Cyclodextrin-based Complex Coacervate Core Micelles with Tuneable Supramolecular Host-guest, Metal-to-ligand and Charge Interactions. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 9542–9549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Leon, L. Structural dynamics, phase behavior, and applications of polyelectrolyte complex micelles. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 53, 101424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Hofs, B.; Voets, I. K.; de Keizer, A. Assembly of polyelectrolyte-containing block copolymers in aqueous media. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 10 (1–2), 30-36.

- Hales, K.; Pochan, D. J. Using polyelectrolyte block copolymers to tune nanostructure assembly. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 11, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colfen, H. Double-hydrophilic block copolymers: synthesis and application as novel surfactants and crystal growth modifiers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2001, 22, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H. J.; Kang, S. Double-Hydrophilic Block Copolymers and Their Self-Assembly. Prog. Chem. 2005, 17, 854–859. [Google Scholar]

- Gohy, J. F. Block Copolymer Micelles. In Block Copolymers II; Abetz, V., Ed.; Advances in Polymer Science; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005; Vol. 190, pp 65-136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, G. Micellization of block copolymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 1107–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, V. A.; Kabanov, A. V. Interpolyelectrolyte and block ionomer complexes for gene delivery: physico-chemical aspects. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1998, 30, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronich, T. K.; Kabanov, A. V.; Eisenberg, A.; Kabanov, V. A. , Block ionomer complexes: Implications for drug delivery. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 223, U438–U438. [Google Scholar]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Polyion complex micelles with core-shell structure: their physicochemical properties and utilities as functional materials. Macromol. Symp. 2001, 172, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhart, C. L.; Kabanov, A. V. Perspectives on Polymeric Gene Delivery. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2003, 18, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, E. R.; Frechet, J. M. J. Development of acid-sensitive copolymer micelles for drug delivery. Pure Appl. Chem. 2004, 76, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, N.; Jang, W-D. ; Kataoka, K. Supramolecular nanocarriers integrated with dendrimers encapsulating photosensitizers for effective photodynamic therapy and photochemical gene delivery. New J. Chem. 2007, 31, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Alexandridis, P. Physicochemical aspects of drug delivery andrelease from polymer-based colloids. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 5, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, K.; Togawa, H.; Harada, A.; Yagusi, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Katayose, S. Spontaneous formation of polyion complex micelles with narrow distribution from antisense oligonucleotide and cationic block copolymer in physiological saline. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 8556–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen Stuart, M. A.; Besseling, N. A. M.; Fokkink, R. G. Formation of Micelles with Complex Coacervate Cores. Langmuir 1998, 14, 6846–6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Novel Polyion Complex Micelles Entrapping Enzyme Molecules in the Core. 2. Characterization of the Micelles Prepared at Nonstoichiometric Mixing Ratios. Langmuir 1999, 15, 4208–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Novel Polyion Complex Micelles Entrapping Enzyme Molecules in the Core: Preparation of Narrowly-Distributed Micelles from Lysozyme and Poly(ethylene glycol)−Poly(aspartic acid) Block Copolymer in Aqueous Medium. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijmans, C. M.; Zhulina, E. B. Polymer brushes at curved surfaces. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 7214–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. Chain length recognition: core-shell supramolecular assembly from oppositely charged block copolymers. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 1999, 283, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, A.; Kataoka, K. On-off Control of Enzymatic Activity Synchronizing With Reversible Formation of Supramolecular Assembly from Enzyme and Charged Block Copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 9241–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H. S.; Kim, H. J.; Naito, M.; Ogura, S.; Toh, K.; Hayashi, K.; Kim, B. S.; Fukushima, S.; Anraku, Y.; Miyata, K.; Kataoka, K. Systemic Brain Delivery of Antisense Oligonucleotides across the Blood-Brain Barrier with a Glucose-Coated Polymeric Nanocarrier. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 8173–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammas, S.; Kataoka, K. Site specific drug-carriers: polymeric micelles as high potential vehicles for biologically active molecules. In Solvents and Self-organization of Polymers; Webber, S. E., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Quémener, D.; Deratani, A.; Lecommandoux, S. Dynamic Assembly of Block-Copolymers; Barboiu, M., Ed.; Constitutional Dynamic Chemistry. Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; Vol.322, pp 165-192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, D. J. Theory of block copolymers. I. Domain formation in A-B block copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part C 1969, 26, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, E.; Tagami, Y. Theory of the Interface between Immiscible Polymers. II. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 3592–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, E.; Tagami, Y. Theory of the Interface Between Immiscible Polymers. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 57, 1812–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, E.; Wasserman, Z. R. Block Copolymer Theory. 4. Narrow Interphase Approximation. Macromolecules 1976, 9, 879–888. [Google Scholar]

- Helfand, E.; Wasserman, Z. R. Block Copolymer Theory. 5. Spherical Domains. Macromolecules 1978, 11, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, E.; Wasserman, Z. R. Block Copolymer Theory. 6. Cylindrical Domains. Macromolecules 1980, 13, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leermakers, F. A. M.; & Scheutjens, J. M. H. M.; Scheutjens, J. M. H. M. Statistical thermodynamics of associated colloids. 1. Lipid bilayer membranes. Journal of Chemical Physics 1988, 89, 3264–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X. F.; Masters, A. J.; Price, C. Self-consistent field theory of micelle formation by block copolymers. Macromolecules 1992, 25, 6876–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, G.; Stuart, M. C.; Scheutjens, J. M.; Cosgrove, T.; Vincent, B. Polymers at interfaces. Chapman and Hall: London, 1993.

- Leermakers, F. A. M.; Eriksson, J. C.; Lyklema, J. Association colloids and their equilibrium modelling. In Fundamentals of Interface and Colloid Science; Lyklema, J., Elsevier Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Vol. V: Soft Colloids, pp 4.1-4.123. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S. F. The statistical mechanics of polymers with excluded volume. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1965, 85, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.D.; Flory, P. J. In: Macromolecular Science. Contemporary Topics in Polymer Science; Ulrich, R. D., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, 1978; Vol. 1, pp 69-98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kik, R. A.; Leermakers, F. A.; Kleijn, J. M. Molecular modeling of lipid bilayers and the effect of protein-like inclusions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kik, R. A.; Lermakers, F. A. M.; Kleijn, J. M. Molecular modeling of protein like inclusions in lipid bilayers: Lipid-mediated interactions. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2010, 81 (2 Pt 1)), 021915/1-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]