Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Materials and Instruments

2.2. Preparation of the Hedysari Radix Disperse Particles and the Modified Samples

2.3. Enzymatic Activity Assays

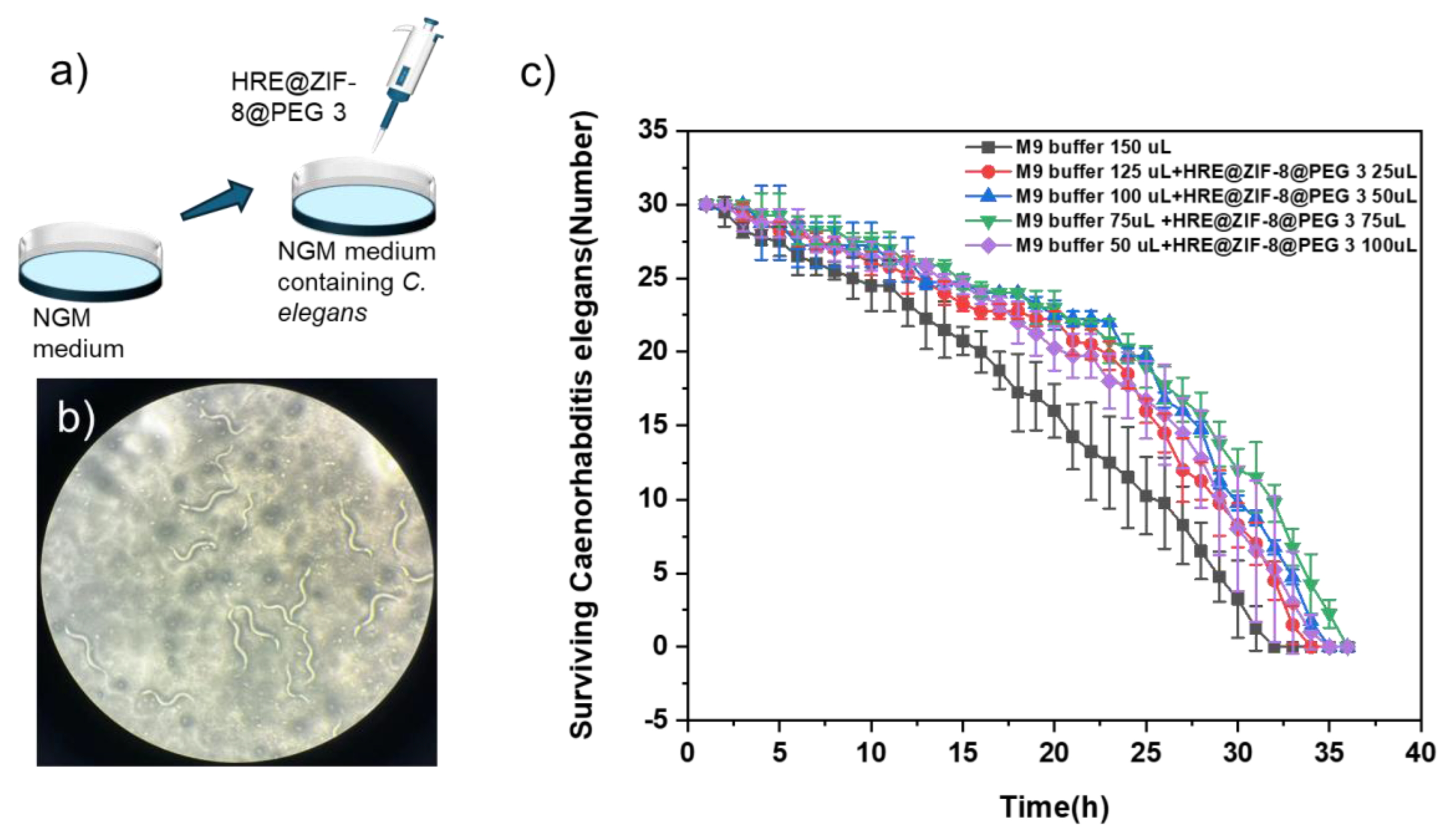

2.4. Testing the Anti-Oxidant Effect in C. elegans

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

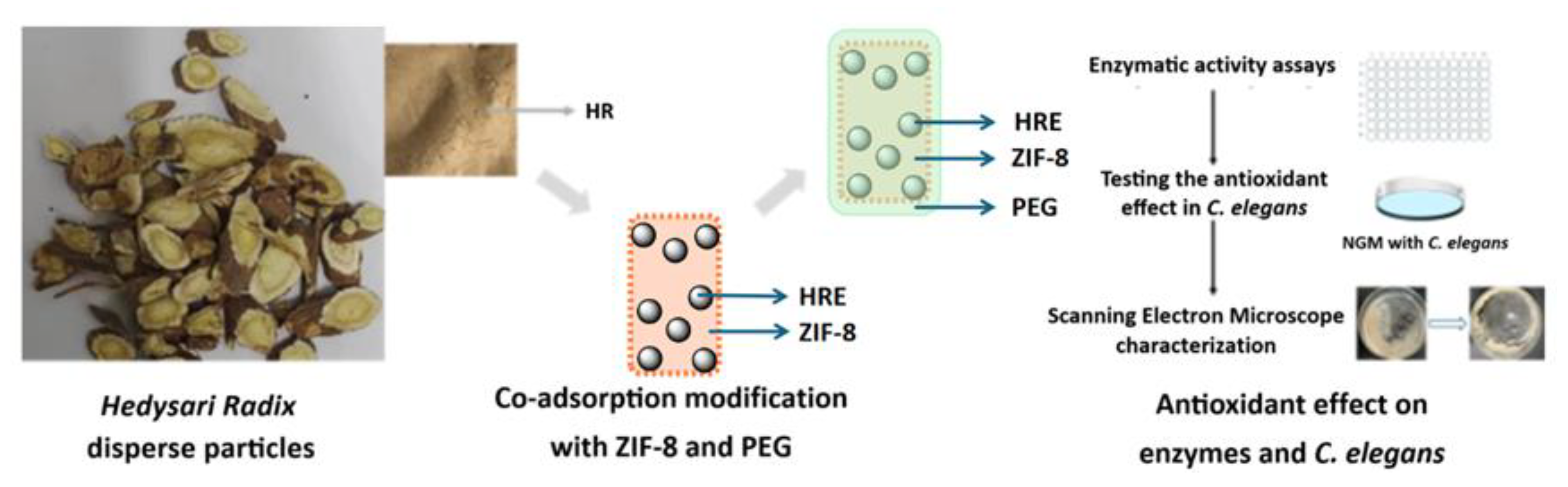

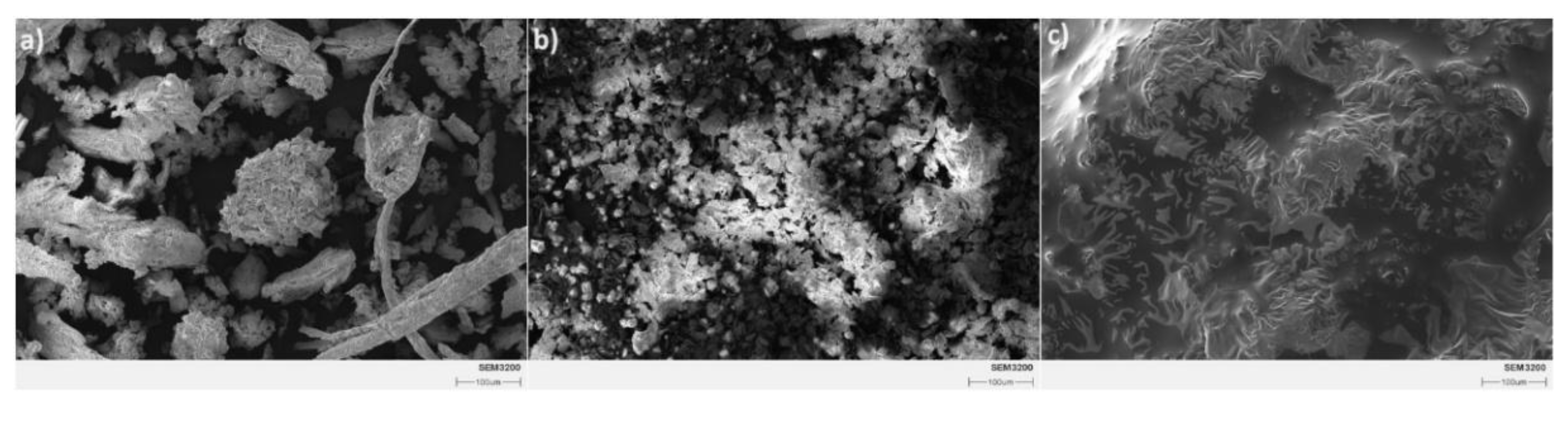

3.1. Co-Adsorption Modification on the Hedysari Radix Disperse Particles

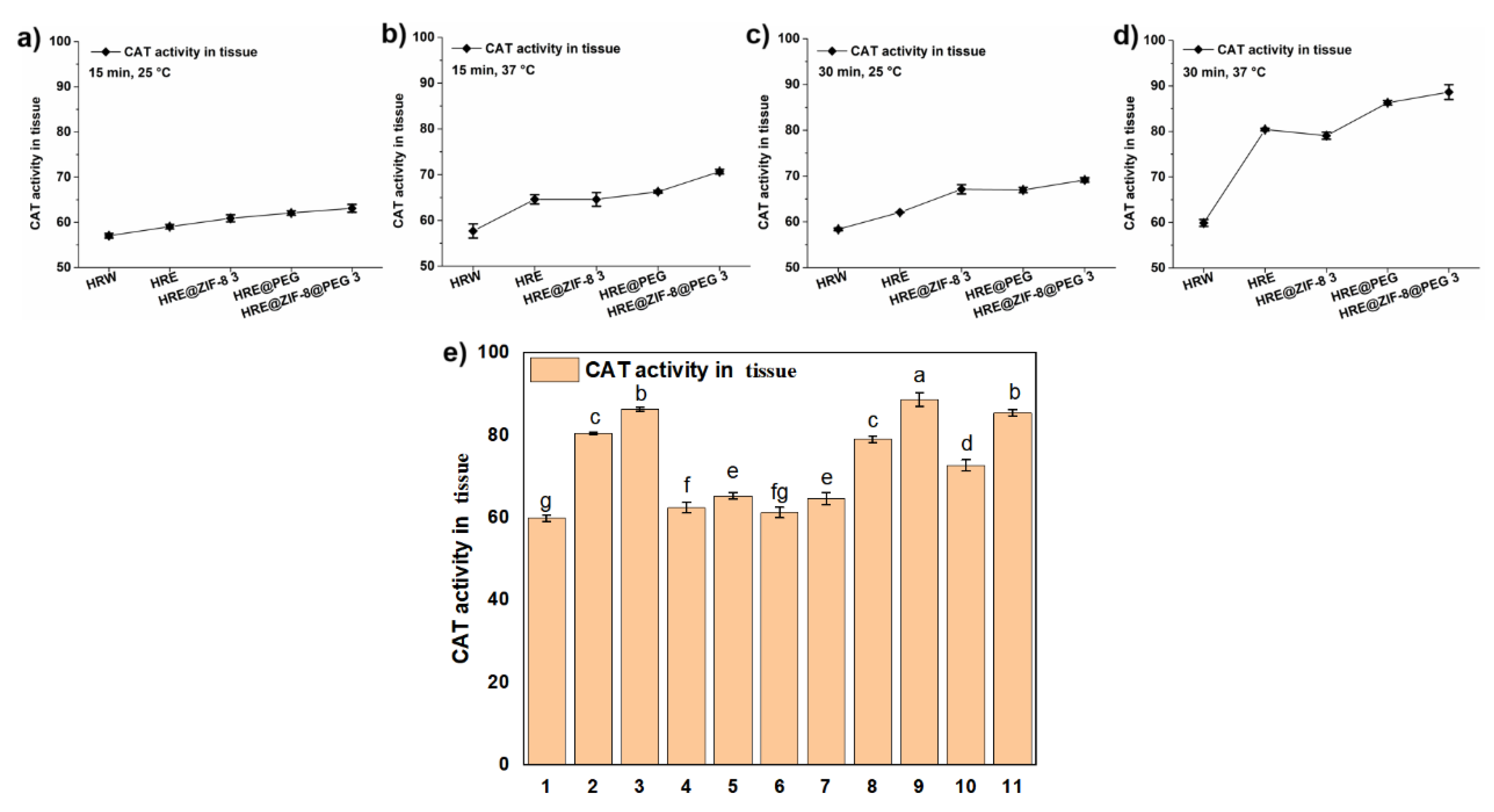

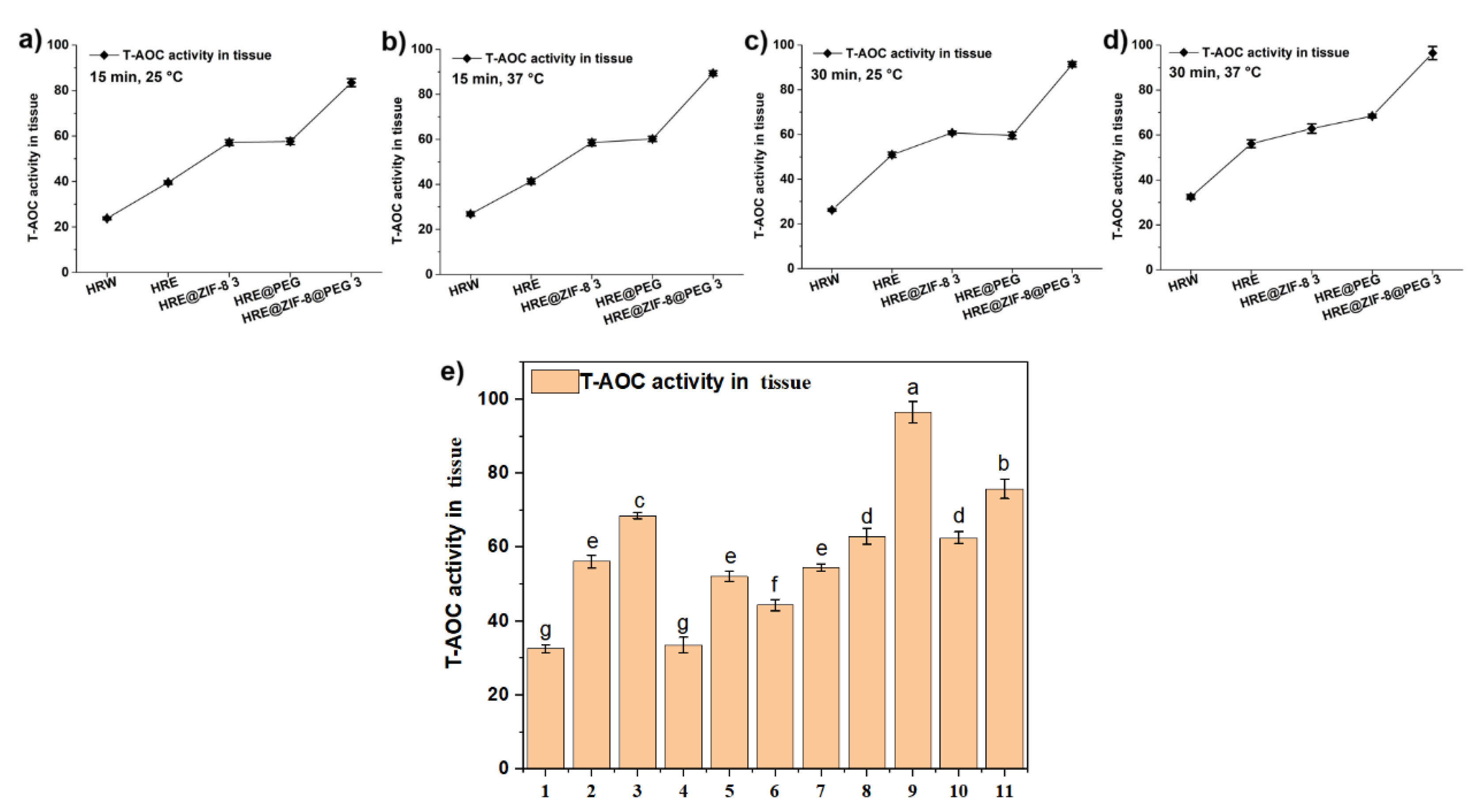

3.2. Testing the Antioxidant Activity in the Solution System

3.3. Testing the Antioxidant Activity upon C. elegans

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Que, L.; Chi, X.L.; Zang, C.X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Yang, G.; Jin, A.Q. Species diversity of ex-situ cultivated Chinese medicinal plants. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2018, 43, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.X.; Zhang, M.X.; Wang, C.C.; Zhang, R.; Shi, T.T.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.B.; Li, M.H. Application of remote sensing technology in medicinal plant resources. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2021, 46, 4689–4696. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.C.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, H.Y.; Qin, M.; Dai, X.Y.; Yan, B.B.; Guo, X.Z.; Zhou, L.; Lin, H.B.; Guo, L.P. Application of tissue culture technology of medicinal plants in sustainable development of Chinese medicinal resources. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2023, 48, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.C.; Fang, C.; Qin, M.; Wang, H.Y.; Guo, X.Z.; Wang, Y.F.; Yan, B.B.; Zhang, Z.H.; Wang, S.; Guo, L.P. DUS testing guidelines for new varieties of Chinese medicinal plants. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2023, 48, 2896–2903. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.F.; Liu, K.Y.; Feng, J.H.; Tong, Y.R.; Gao, W. Research progress in synthetic biology of active compounds in Chinese medicinal plants. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2021, 46, 5727–5735. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X.L.; Guo, D.K.; Jiang, Y.G.; Chen, P.; Huang, L.F. Isolation, structures and bioactivities of the polysaccharides from Radix Hedysari: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 199, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Zhang, S.J.; Niu, J.T.; Si, X.L.; Bian, T.T.; Wu, H.W.; Li, D.H.; Li, Y.F. Comparative study of Astragali Radix Praeparata cum Melle and Hedysari Radix Praeparata cum Melle on spleen Qi deficiency rats. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2021, 46, 5641–5649. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.W.; Gu, Z.R.; Guo, Y.; Lyu, X.; Ge, B. Research hotspots and trends of Hedysari Radix: based on CiteSpace knowledge map. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2022, 47, 3095–3104. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.B.; Qu, C.H.; Dong, X.X.; Shen, M.R.; Ni, J. Preparation regularity of Chinese patent medicine in Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 edition, Vol. Ⅰ). Chin J Chin Mater Med 2022, 47, 4529–4535. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K.R.; Li, X.R.; Wei, X.C.; He, J.G.; Jia, M.T.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.T.; Xie, X.M.; Li, C.Y. Research progress on pharmacological action and mechanism of Hedysari Radix flavones. Chin Trad Herb Drugs 2024, 55, 3906–3915. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.B.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, T.J. Research progress in study on chemical constituents and antitumor effects in Hedysarum polybotrys. Chin Trad Herb Drugs 2015, 46, 3434–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Ren, C.Z.; Li, L.Y.; Zhao, H.L.; Liu, K.; Zhuang, M.J.; Lv, X.F.; Zhi, X.D.; Jiang, H.G.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhao, X.K.; Li, Y.D. Pharmacological action of Hedysarum polysaccharides: a review. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1119224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Guo, L.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.L.; Feng, S.L. Chemical structural features and anti-complementary activity of polysaccharide HPS1-D from Hedysarum polybotrys. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2014, 39, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Chen, H.B.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Q.Y. Chemotaxonomy studies on the genus Hedysarum. Biochem Syst Ecol 2019, 86, 103902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xing, H.; Li, X. Effect of Radix Hedysari Polysaccharide on Glioma by Cell Cycle Arrest and TNF-α Signaling Pathway Regulation. Int J Polym Sci 2019, 2019, 2725084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.F.; Cheng, W.D.; Gui, M.M.; Li, X.Y.; Wei, D.F. Comparative study of Radix Hedyseri as sulstitute for Radix Astragali of yupingfeng oral liquid on cellular immunity in immunosuppressed mice. J Chin Med Mater 2012, 35, 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.P.; Xiu, M.H.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, S.W.; Wan, S.F.; Han, S.Z.; Yang, D.; Liu, Y.Q.; He, J.Z. The antioxidant effects of hedysarum polybotrys polysaccharide in extending lifespan and ameliorating aging-related diseases in Drosophila melanogaster. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 241, 124609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Dong, J.Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.L. Antioxidant effect of total flavonoids of Hedysarum polybotry on human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury induced by hydrogen peroxide. J Chin Med Mater 2007, 30, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.Y.; Xue, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.F.; Fang, Y.Y.; Zhou, X.L.; Zhao, L.G.; Feng, S.L. Complex enzyme combined with ultrasound extraction technology, physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of Hedysarum polysaccharides. Chin J Chin Mater Med 2018, 43, 2261–2268. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.W.; Wei, S.C.; Yan, C.L.; Wang, R.Q.; Li, Y.D. The influences of ultrafiltration and alcohol sedimentation on protective effects of Radix Astragali and Radix Hedyseri against rat’s cerebral ischemia. Chin J Appl Phys 2015, 31, 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.J.; Yang, Z.J.; Li, S.; Ji, X.J.; Ning, Y.M.; Wang, Y. Effects of Radix Hedysari, Radix Astragalus and compatibility of Angelica Sinensis on blood deficiency model mice induced by cyclophosphamide. Chin J Appl Phys 2018, 34, 550–554. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Gu, K.; Shao, Z. Preparation of the Protein/Polyphenylboronic Acid Nanospheres for Drug Loading and Unloading. Acta Chim Sin 2023, 81, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.Q. Nano Traditional Chinese Medicine: Current Progresses and Future Challenges. Curr Drug Targets 2015, 16, 1548–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.W.; Guo, M.Q.; Wang, W.H.; He, J.B.; Wu, C.B.; Pan, X.; Zhang, X.J.; Huang, Y.; Hu, P. Crosstalk between nano/micro particulate technologies and Chinese medicine: a bibliometric analysis. Tradit Med Res 2023, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Han, Y.; Fan, M.; Li, Z.; Ge, K.; Liang, X.J.; Zhang, J. Metal-organic framework-based nanocatalytic medicine for chemodynamic therapy. Sci China-Mater 2020, 63, 2429–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Metal-organic-framework-based catalysts for hydrogenation reactions. Chin J Catal 2017, 38, 1108–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, Q.; Lin, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Xia, C.; Bao, T.; Wan, J.; Huang, R.; Zou, J.; Yu, C. Ternary MOF-on-MOF heterostructures with controllable architectural and compositional complexity via multiple selective assembly. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Song, L.J.; Luan, S.F. Elimination Ability of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 Against Biofilms on Medical Polymer Surface. Chin J Anal Chem 2023, 51, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Ju, W.; Wang, T.; Sun, X.; Zhao, T.; Lu, X.; Lu, F.; Fan, Q. Preparation of Highly-dispersed Conjugated Polymer-Metal Organic Framework Nanocubes for Antitumor Application. Acta Chim Sin 2023, 81, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zhu, Y.; Teng, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, S.; Meyer, T.J.; Chen, Z. Fabrication of complex, 3D, branched hollow carbonaceous structures and their applications for supercapacitors. Sci Bull 2022, 67, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Xie, Z.; Yu, S.; Li, L.; Xiao, H.; Song, Y. Hyaluronic acid coating on the surface of curcumin-loaded ZIF-8 nanoparticles for improved breast cancer therapy: An in vitro and in vivo study. Colloid Surface B 2021, 203, 111759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.B.; Cao, P.; Jiang, C.Y.; Qiao, H.Z.; Peng, L.H.; Lin, X.D.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Jin, H.L.; Zhang, H.T.; Wang, S.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Fan, J.B.; Li, B.; Li, G.; Liu, B.F.; Li, Z.Y.; Qi, S.H.; Zhang, M.Z.; Zheng, J.J.; Zhou, J.Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, K.W. Consensus statement on research and application of Chinese herbal medicine derived extracellular vesicles-like particles (2023 edition). Chin Herb Med 2024, 16, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.J.; Wang, Y.L.; Han, X.X.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, H.; Chen, J.; Ji, D.; Mao, C.Q.; Lu, T.L. A Modern Technology Applied in Traditional Chinese Medicine: Progress and Future of the Nanotechnology in TCM. Dose-Response 2019, 17, 1559325819872854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M.; Yasin, K.A.; Haq, S. Elmnasri K. Ben Ali M, Boufahja F, Shukurov O, Mahmoudi E, Hedfi A. Synthesis and characterization of manganese-L-arginine framework (MOF) for antibacterial and antioxidant studies. Dig J Nanomater Bios 2024, 19, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Sun, W.; Lin, J.T.; Fan, C.Y.; Wang, C.X.Q.; Zhang, Z.S.; Wang, Y.P.; Tang, Y.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Zhou, D.F. Using Cu-Based Metal–Organic Framework as a Comprehensive and Powerful Antioxidant Nanozyme for Efficient Osteoarthritis Treatment. Adv Sci 2024, 11, 2307798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermy, B.R.; Al-Jindan, R.Y.; Ravinayagam, V.; El-Badry, A.A. Anti-blastocystosis activity of antioxidant coated ZIF-8 combined with mesoporous silicas MCM-41 and KIT-6. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.M.; Allyn, M.; Swindle-Reilly, K.; Palmer, A.F. ZIF-8 metal organic framework nanoparticle loaded with tense quaternary state polymerized bovine hemoglobin: potential red blood cell substitute with antioxidant properties. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 8832–8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchigna, M.; Cateni, F.; Procida, G. Improvement of Chemical and Physical Properties and Antioxidant Evaluation of Eugenol - PEG adduct. Nat Prod Commun 2017, 12, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.H.; Yang, Y.Q.; Zheng, Y.F. Preparation of curcuminoids-loaded PCL-PEG-PCL microspheres, and study on their drug delivery and antioxidant activity. Modern Chemical Industry 2022, 42, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.W.; Qi, X.R.; Wang, Y.H.; Zheng, Z.T.; Liang, J.Q.; Ling, J.T.; Chen, Y.X.; Tang, X.Y.; Zeng, X.X.; Yu, P.; Zhang, D.J. Application of fermented Chinese herbal medicines in food and medicine field: From an antioxidant perspective. Trends Food Sci Tech 2024, 148, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, O.W.L.; Xu, Y.J.; Sadler, P.J. Minerals in biology and medicine. RSC Adv 2021, 11, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Wang, Y.G.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Yan, P.M.; Xiao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, W.W.; Ding, L.; Dong, H.Y.; Wei, C.; Lin, S.; Lin, Y. Paeoniflorin alleviates AngII-induced cardiac hypertrophy in H9c2 cells by regulating oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 165, 115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, R.J.; Hu, Y.C.; Wei, Y.Y.; Qin, X.D.; Lu, Y.W. The neuroprotective effects of Rehmanniae Radix Praeparata exerts via regulating SKN-1 mediated antioxidant system in Caenorhabditis elegans and activating Nrf2-ARE pathway in vitro. J Funct Foods 2024, 113, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.H.; Feng, W.R.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.F.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.L.; Xu, P.; Tang, Y.K. H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress Responses in Eriocheir sinensis: Antioxidant Defense and Immune Gene Expression Dynamics. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, R.; Franz, G. Modern European Monographs for Quality Control of Chinese Herbs. Planta Med 2010, 76, 2004–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.P.; Zhao, J.; Yang, B. Strategies for quality control of Chinese medicines. J Pharmaceut Biomed 2011, 55, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Z.L.; Feng, D.M.; Liu, X.H.; Yang, T.; Guo, L.; Liang, J.; Liang, J.D.; Hu, F.D.; Cui, F.; Feng, S.L. Structure and antioxidant activity study of sulfated acetamido-polysaccharide from Radix Hedysari. Fitoterapia 2013, 89, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.; Ng, L.F.; Poovathingal, S.K.; Halliwell, B. Deceptively simple but simply deceptive - Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan studies: Considerations for aging and antioxidant effects. FEBS Lett 2009, 583, 3377–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.D.; Lin, D.Y.; Love, M.I. Consistency and overfitting of multi-omics methods on experimental data. Brief Bioinform 2020, 21, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Feng, R.X.; Chang, Z.H.; Liu, X.J.; Tang, H.; Bai, Q. Hybrid biomimetic assembly enzymes based on ZIF-8 as “intracellular scavenger” mitigating neuronal damage caused by oxidative stress. Front Bioeng Biotech 2022, 10, 991949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Shan, P.; Yu, F.Y.; Li, H.; Peng, L.C. Fabrication and characterization of waste fish scale-derived gelatin/sodium alginate/carvacrol loaded ZIF-8 nanoparticles composite films with sustained antibacterial activity for active food packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 230, 123192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidi, Z.; Roohbakhsh, A.; Karimi, G. An overview on the protective effects of ellagic acid against heavy metals, drugs, and chemicals. Nutr Food Sci 2023, 11, 7469–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.X.; Guo, Z.M.; Zhao, R.H.; Yin, N.; Xu, Q.L.; Yao, X. A simple method for the preparation of CeO2 with high antioxidant activity and wide application range. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 105706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Quan, J.I.; Blackwell, T.K. Metformin: Restraining Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling to Fight Cancer and Aging. Cell 2016, 167, 1670–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Wang, G.; Feng, T.; Shen, M.; Xiao, B.; Gu, J.Y.; Wang, W.M.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.J. Evaluation of the antioxidant effects of acid hydrolysates from Auricularia auricular polysaccharides using a Caenorhabditis elegans model. Food Funct 2019, 10, 5531–5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.G.; Park, Y.; Park, J.E.; Park, N.I. Enhancement of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidative Activities by the Combination of Culture Medium and Methyl Jasmonate Elicitation in Hairy Root Cultures of Lactuca indica L. Nat Prod Commun 2019, 14, DOI10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.S.; Iqbal, Z.; Ansari, M.I. Enhancement of total antioxidants and flavonoid (quercetin) by methyl jasmonate elicitation in tissue cultures of onion (Allium cepa L.). Acta Agrobot 2019, 72, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutimanukul, P.; Sukdee, S.; Prajuabjinda, O.; Thepsilvisut, O.; Panthong, S.; Ehara, H.; Chutimanukul, P. Exogenous Application of Coconut Water to Promote Growth and Increase the Yield, Bioactive Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity for Hericium erinaceus Cultivation. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, A.; Soundararajan, P.; Halimah, N.; Ko, C.H.; Jeong, B.R. Blue LED Light Enhances Growth, Phytochemical Contents, and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities of Relunannia glutinosa Cultured In Vitro. Hortic Environ Biote 2015, 56, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, K.; Kumari, S.; Vinutha, T.; Singh, B.; Dahuja, A. Gamma irradiation induces reduction in the off-flavour generation in soybean through enhancement of its antioxidant potential. J Radioanal Nucl Ch 2015, 303, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabajal, M.P.A.; Isla, M.I.; Borsarelli, C.D.; Zampini, I.C. Influence of in vitro gastro-duodenal digestion on the antioxidant activity of single and mixed three “Jarilla” species infusions. J Herb Med 2020, 19, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 62 Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Tan, J.; Li, R.; Jiang, Z.T.; Tang, SH. Enhancement of the Stabilities and Intracellular Antioxidant Activities of Lavender Essential Oil by Metal-Organic Frameworks Based on β-Cyclodextrin and Potassium Cation. Pol J Food Nutr Sci 2021, 71, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.Y.; Han, Y.X.; Xu, Y.Q.; Liu, T.G.; Cui, M.Y.; Xia, L.L.; Li, H.N.; Gu, Y.Q.; Wang, P. Diversified strategies based on nanoscale metal-organic frameworks for cancer therapy: The leap from monofunctional to versatile. Coordin Chem Rev 2021, 431, 213676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.M.; Zhao, X.J.; Sun, X.J.; Lv, J.Z. Wide temperature adaptive oxidase-like based on mesoporous manganese based metal-organic framework for detecting total antioxidant capacity. Food Chem 2024, 451, 139378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.; Li, Y.P.; Xie, L.H.; Li, X.Y.; Li, J.R. Construction and application of base-stable MOFs: a critical review. Chem Soc Rev 2022, 51, 6417–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.V.; Le Cerf, D. Colloidal Polyelectrolyte Complexes from Hyaluronic Acid: Preparation and Biomedical Applications. Small 2022, 18, 2204283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).