1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) represents a vast ecosystem of interconnected smart devices that autonomously collect, share, and process data over the internet without direct human intervention [

1]. This paradigm has transformed numerous sectors, including healthcare, energy, transportation, smart cities, and finance, enabling real-time monitoring, automation, and data-driven decision-making. However, the widespread adoption of IoT also expands the attack surface, exposing devices and networks to diverse cyber and privacy threats [

2]. In healthcare IoT, for instance, sensors embedded in wearable devices or medical equipment can reveal highly sensitive information such as health conditions, daily routines, and precise locations. Notable incidents, such as the 2021 Verkada breach [

3], which compromised live feeds from 150 million surveillance cameras, highlight the urgency for robust security and privacy-preserving mechanisms. Developing secure, privacy-aware IoT infrastructures is therefore critical to ensure public trust and enable large-scale adoption.

To counter cyberattacks in IoT ecosystems,

Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) have become a primary defense mechanism, particularly those based on anomaly detection [

4,

5]. Such systems monitor behavioral patterns and flag deviations as potential intrusions, often combining anomaly-based methods with signature-based techniques to improve accuracy. Traditional IDS architectures predominantly rely on centralized machine learning (ML), where IoT devices transmit raw data to a cloud server for training and inference. This approach suffers from several limitations: (i) sensitive raw data is exposed to third-party servers, creating privacy risk; (ii) compliance with cross-border data protection regulations becomes challenging; and (iii) high network and computation overhead arises from transmitting large and heterogeneous IoT datasets. Decentralized approaches, which perform processing closer to the data source, such as at the edge or fog layer, offer a promising alternative to mitigate these issues.

Federated Learning (FL) [

6] addresses these limitations by enabling multiple clients to collaboratively train a global model

without sharing raw data. In FL, a central server initializes a global IDS model and distributes it to participating clients. Each client performs local training on private datasets and sends only model updates (weights or gradients) back to the server. Aggregation methods, such as

Federated Averaging (FedAvg) [

7], combine these updates to refine the global model iteratively. This process continues until the model converges or reaches desired accuracy, improving its generalization to unseen attack patterns. Numerous FL variants have been proposed to accelerate convergence, enhance robustness, and secure communication between clients and the central server.

Several FL-based IDS frameworks for IoT have been developed [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Nevertheless, these methods often rely on resource-constrained IoT devices as FL clients, which presents challenges such as limited computation, energy restrictions, and high communication overhead. To address these limitations, we propose a

Privacy-Preserving Hierarchical Fog Federated Learning (PP-HFFL) framework for IoT intrusion detection, which integrates the advantages of Fog-based Federated Learning (Fog-FL) while incorporating privacy-preserving mechanisms. In PP-HFFL,

fog nodes—positioned between IoT devices and the cloud—function as local aggregators and decision-makers, while IoT devices primarily collect and preprocess data. This hierarchical approach reduces communication overhead & latency, and enhances scalability by offloading computation to fog nodes. Additionally, fog nodes enable near real-time intrusion detection by processing data close to the source and responding rapidly to anomalous events.

Despite the benefits of PP-HFFL, several challenges persist, particularly at the fog layer. The most critical include

non-IID (non-independent and identically distributed) data [

13],

system scalability, and

data privacy [

14]. Addressing these issues is essential to ensure PP-HFFL–based IDS frameworks remain effective, secure, and reliable across heterogeneous IoT environments. This study systematically investigates these challenges and proposes solutions validated on real-world IoT benchmark datasets.

Non-IID Data: In PP-HFFL, each fog node aggregates updates from multiple heterogeneous IoT devices, often resulting in skewed or imbalanced class distributions and, in extreme cases, missing classes on certain clients. Such non-IID conditions can lead to biased model updates, slower convergence, and reduced global model accuracy. The severity of these effects depends on the complexity of the dataset and the degree of distributional heterogeneity, motivating a detailed analysis of non-IID impacts in hierarchical Fog-FL systems.

Scalability: Scalability in PP-HFFL involves supporting a variable number of fog nodes and handling dynamic node participation. Increasing the number of fog nodes can enhance learning capacity but may also exacerbate heterogeneity. Moreover, nodes may join or leave during training, requiring robust coordination mechanisms to maintain stable convergence. Studying scalability behavior under diverse participation scenarios is thus crucial for practical deployments.

Data Privacy: Although FL reduces privacy risks by keeping data local, interactions at the fog layer can introduce new attack surfaces. Malicious fog nodes could infer sensitive patterns from model updates or manipulate aggregation results. PP-HFFL integrates Differential Privacy (DP) mechanism to maintain strong privacy guarantees without significantly compromising model utility.

The primary objective of this research is to design and evaluate the PP-HFFL–based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) that addresses the identified challenges. Specifically, we (i) examine the effect of non-IID data on detection accuracy, (ii) evaluate system scalability under varying fog node participation, and (iii) incorporate Differential Privacy (DP) at the fog layer to quantify the privacy–utility trade-off. Experimental validation is performed using two IoT benchmark datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness, efficiency, and practicality of the proposed approach.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents background concepts,

Section 3 surveys related works,

Section 4 details the architecture of the proposed PP-HFFL framework,

Section 5 reports experimental evaluations and discussions, and

Section 6 concludes with key findings and future directions.

2. Background

2.1. Federated Learning

Federated Learning (FL), first introduced by Google in 2017, was designed to enable Android users to collaboratively train models without sharing personal data [

7]. FL represents a privacy-preserving, decentralized paradigm of machine learning (ML), where a global model is trained across multiple clients without transferring raw data to a central server. Each client independently optimizes a local objective function—typically through stochastic gradient descent (SGD)—and sends the resulting model updates or gradients to a coordinating server. The server then performs an aggregation step, usually by averaging the received parameters, to update the global model. This process is repeated iteratively until convergence.

Under certain data distributions and system configurations, FL can achieve performance comparable to centralized ML models, while providing stronger privacy guarantees. The foundational FL formulation proposed by [

7] is defined as:

where

denotes the loss function for the

i-th training sample

parameterized by

. Here,

K represents the total number of participating clients, and

is the local objective of client

k, which contains

samples stored in its dataset

. The total dataset size across all clients is

.

A common aggregation rule is the

Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm [

7], where the global update after each communication round

t is computed as:

where

is the locally updated parameter vector of the

k-th client after completing its local training in round

t. This weighted averaging ensures that clients with larger datasets contribute proportionally more to the global update.

Despite its advantages, FL faces several challenges, including communication overhead, client heterogeneity, and data non-IIDness, especially in Internet of Things (IoT) environments, where clients are resource-constrained devices with intermittent connectivity [

14,

15].

2.2. Non-IID Properties of IoT Data

In a Fog-FL–based intrusion detection system (IDS), fog nodes aggregate data from nearby IoT devices and act as clients in the federated setup. However, some fog clients may only receive data samples belonging to a limited subset of malware classes, leading to a

label imbalance across clients. Moreover, certain types of attacks appear more frequently in practice, creating an

overall class imbalance at the system level. When both types of imbalance coexist, the heterogeneity—or non-IID nature—of the data is further exacerbated [

16,

17].

To model such non-IID distributions in FL simulations, two widely adopted strategies are

uniform label assignment and

Dirichlet sampling. In the first, each client is restricted to a fixed number of classes, and samples from those classes are distributed evenly. This generates deterministic non-IID partitions while maintaining the global class balance. In contrast, Dirichlet sampling stochastically partitions data according to a Dirichlet(

) distribution:

where

is the proportion of class

c assigned to client

k, and

controls the degree of heterogeneity—smaller

values produce more skewed class distributions, whereas larger values approximate IID conditions [

18].

Beyond label imbalance, non-IID data may also arise due to:

Covariate shift: where the input feature distribution varies across clients while the conditional label distribution remains constant.

Concept shift: where clients share the same feature distribution but differ in label assignments, i.e., changes across clients.

These advanced distribution shifts introduce significant challenges in achieving convergence and fairness in global optimization but are beyond the immediate scope of this work.

2.3. Personalization in Federated Learning

Traditional FL seeks to learn a single global model that performs well across all clients. However, in the presence of highly heterogeneous (non-IID) data, a single model often underperforms for certain clients, as it cannot fully capture their local data characteristics. Conversely, training individual local models in isolation may lead to overfitting and poor generalization.

To balance this trade-off,

Personalized Federated Learning (PFL) [

19,

20] introduces adaptation mechanisms that tailor the global model to each client’s data distribution. The general objective of PFL can be represented as:

where

is a regularization parameter that controls the closeness between the local and global models. Smaller

encourages greater personalization, while larger values enforce stronger alignment with the global model.

Among the numerous approaches proposed, one effective strategy involves

client clustering [

21,

22], which groups clients with similar data distributions or geographical proximity. In a Fog-FL–based IoT system, such clustering occurs naturally: IoT devices within the same fog domain often share environmental and traffic characteristics. By fine-tuning the pre-trained fog model on its local data, each fog node can achieve both personalization and scalability in intrusion detection tasks.

2.4. Differential Privacy

Differential Privacy (DP) is a rigorous mathematical framework designed to protect individual data contributions while allowing useful aggregate analysis [

23,

24]. A mechanism

satisfies

-DP if, for all neighboring datasets

D and

differing by one record, and for all output subsets

S:

Here,

controls the privacy-utility trade-off (smaller

implies stronger privacy), and

represents a small probability of failure.

In the

central differential privacy (CDP) setting, a trusted server collects raw data and adds noise to outputs before release. In contrast,

local differential privacy (LDP) ensures that each client perturbs its own data or gradients before sharing, offering privacy even from the server [

25].

In Fog-FL, both models are applicable. A fog node can apply CDP when aggregating data from IoT devices, or LDP when acting as a client that perturbs its own gradient updates. Standard mechanisms for adding DP noise include the Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms [

26], where random noise proportional to the query’s sensitivity is injected.

To manage privacy loss across multiple training rounds,

Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) [

27] provides a tighter composition bound. The

-RDP guarantee for a mechanism

is defined as:

where

denotes the Rényi divergence of order

. RDP is particularly suitable for DP-SGD implementations (e.g., TensorFlow Privacy, Opacus) used in FL, as it efficiently tracks cumulative privacy loss across communication rounds.

In summary, integrating RDP-based noise mechanisms within Fog-FL architectures strikes a balance between privacy protection, model utility, and computational feasibility, making it suitable for IoT-based intrusion detection systems.

3. Related Work

Federated learning (FL) has emerged as a promising paradigm for constructing intrusion detection systems (IDS) across distributed and privacy-sensitive Internet of Things (IoT) environments. In contrast to centralized learning, FL allows multiple IoT nodes to collaboratively train models without sharing raw data, thereby preserving privacy while leveraging distributed intelligence.

Several studies have explored FL-based IDS designs for diverse IoT scenarios. For instance, FLEAM [

28] was developed for IoT-based Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack detection by integrating FL with edge analytics to counter large-scale attacks efficiently. Federated mimic learning [

29] introduced a teacher–student knowledge distillation mechanism to improve IDS accuracy while maintaining data confidentiality. Similarly, DeepFed [

30] applied deep learning–based FL within industrial cyber–physical systems, demonstrating the potential of collaborative anomaly detection across heterogeneous industrial sites. In the agricultural domain, FELIDS [

10] extended FL to smart farming scenarios, showcasing lightweight intrusion detection for resource-constrained devices and emphasizing scalability in distributed environments. Furthermore, a privacy-preserving FL-based IDS was proposed in [

31] to secure IoT systems without exposing sensitive local data. More recently, FL-IDS [

32] further advanced this line of research by incorporating FL into IoT-based IDS with a focus on maintaining high detection accuracy across heterogeneous client devices and non-uniform environments.

Despite these advances, most conventional FL-based IDS still face critical challenges, including synchronization delays, excessive communication overhead, non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data, and constrained edge resources. IoT devices inherently exhibit limitations in computation, memory, energy, bandwidth, and hardware diversity, compounded by statistical heterogeneity in local data distributions. These constraints make standard FL protocols difficult to deploy effectively at the edge, as emphasized in [

33]. Consequently, recent research trends emphasize the development of more adaptive, hierarchical, and resource-efficient FL architectures tailored for IoT-based intrusion detection.

3.1. Fog-Enabled Federated Learning for IoT IDS

To mitigate resource constraints and communication latency in IoT-based IDS, several studies have proposed integrating fog computing with federated learning. The fog layer, positioned between the edge and the cloud, provides intermediate computation, storage, and coordination capabilities—making it particularly suitable for latency-sensitive IoT security applications.

Javeed et al. [

34] incorporated fog computing into FL to offload intensive training tasks from resource-limited IoT devices, thereby reducing latency and improving overall IDS performance. Bensaid et al. [

35] extended this concept by securing IoT systems through fog-layer FL deployment, achieving low-latency collaborative intrusion detection while preserving client privacy. Similarly, Liu et al. [

36] investigated fog-client selection strategies—both random and resource-aware—demonstrating how optimized fog participation can reduce communication costs and improve detection efficiency. A hierarchical federated structure, Fog-FL [

37], was proposed to further improve scalability, where geographically distributed fog nodes perform local aggregation and synchronization with the cloud. This design effectively reduces uplink bandwidth usage and aligns FL with edge constraints. In a similar vein, de Souza et al. [

38] developed a fog-based FL framework for IDS that exploits fog-layer processing to enhance scalability, responsiveness, and distributed model accuracy in large-scale IoT deployments.

In addition to these approaches, Abdel-Mageed et al. [

39] proposed a privacy-preserving fog–federated IDS that jointly addresses non-IID data distribution and adversarial data leakage through the integration of generative adversarial networks (GANs) and differential privacy. Their work highlights the growing emphasis on designing hybrid privacy mechanisms at the fog layer to balance learning efficiency with confidentiality, particularly in heterogeneous and dynamic IoT ecosystems.

Table 1 summarizes representative fog-enabled FL approaches for IDS. These systems collectively illustrate how bringing computation closer to data sources can alleviate the bottlenecks of traditional FL. By reducing uplink communication, minimizing latency, and adapting to edge-level heterogeneity, fog-based FL significantly enhances responsiveness and scalability for IoT intrusion detection. Nonetheless, as summarized in the table, several limitations persist: most studies provide limited treatment of non-IID data handling, only partially address scalability in dynamic network topologies, and often overlook end-to-end privacy preservation at the fog layer. Compared to the broader FL-IDS literature, relatively few studies explicitly emphasize fog-layer deployment, leaving a significant opportunity for future research to design more robust, privacy-preserving, and adaptive fog–federated IDS frameworks (e.g., integrating differential privacy [

40] or secure aggregation [

41] at the fog layer).

Summary and Research Gap

In summary, existing literature has established the potential of federated learning (FL) and fog computing as enablers of collaborative and privacy-aware intrusion detection in IoT ecosystems. However, the reviewed studies reveal that most frameworks prioritize performance, with only a few addressing scalability and/or privacy; rarely are all three properties achieved simultaneously under the realistic non-IID conditions. Furthermore, current fog–federated systems often lack adaptive mechanisms to dynamically balance communication cost, convergence speed. These challenges underscore the need for a unified architecture that jointly optimizes non-IID robustness, scalability, and privacy preservation.

Addressing these issues forms the central motivation of this work, which proposes a Privacy-Preserving Hierarchical Fog Federated Learning (PP-HFFL) framework. PP-HFFL is designed to provide scalable, privacy-preserving, and adaptive intrusion detection in large-scale IoT networks, capable of operating efficiently under heterogeneous, adversarial, and real-world deployment scenarios.

4. PP-HFFL: Privacy-Preserving Hierarchical Fog Federated Learning for IDS

Building upon insights and limitations identified in existing literature, this section introduces the proposed PP-HFFL framework for intrusion detection systems (IDS). The methodology is designed to explicitly address challenges in scalability, heterogeneous data, and privacy leakage, combining the hierarchical advantages of fog computing with the collaborative intelligence of federated learning. PP-HFFL enhances efficiency, accuracy, and adaptability while maintaining strong privacy guarantees. The subsections below describe the system architecture, underlying algorithms, implementation strategies, and security and privacy analyses.

System Assumptions

Several key assumptions regarding the system entities, operational environment, and trust model are outlined:

Data Assumptions: IoT-collected datasets represent diverse behavioral and operational patterns, which are privacy-sensitive. Aggregated datasets at the fog level are inherently non-IID due to: (i) each fog node observing distinct subsets of attack and benign classes, and (ii) imbalanced class distributions both across and within clients. Data drift may occur over time as device behaviors evolve or new IoT devices join the network.

Trust Assumptions: Each fog client is trusted by its associated IoT devices. All other fog nodes and the central cloud server are semi-honest (honest-but-curious), meaning they follow the protocol but may attempt to infer privacy-sensitive information from updates. No entity is fully malicious or colluding unless explicitly defined in the threat model.

Computation Assumptions: IoT edge devices are resource-constrained, with limited processing power, memory, and energy, and cannot efficiently train complex ML models. Fog nodes have moderate computational resources to perform local training and communication with both IoT devices and cloud server, while the cloud server has sufficient computational capacity for global coordination and aggregation.

Communication Assumptions: IoT-to-fog communication is bandwidth-limited and may experience latency or data loss. Fog-to-cloud links are relatively stable, leveraging high-speed backhaul. Synchronization between fog and cloud layers is periodic, conserving bandwidth while enabling efficient model updates.

Security and Privacy Assumptions: Standard cryptographic mechanisms (secure aggregation) are assumed to protect local updates at the server side and prevent model inversion attacks. Secure key exchange and authentication exist between fog nodes and cloud to prevent impersonation or poisoning attacks.

Deployment Assumptions: Each fog node serves a fixed set of IoT clusters. The number of fog nodes may scale dynamically based on network density. Time synchronization across nodes is loosely coordinated to allow asynchronous or semi-synchronous federated updates.

Figure 1.

Privacy-Preserving Hierarchical Fog Federated Learning (PP-HFFL) framework for IoT intrusion detection. The hierarchical architecture consists of three tiers: the Cloud Tier, which initializes and aggregates the global IDS model; the Fog Tier, where fog nodes perform client selection, local training with differential privacy (DP), and model personalization to handle non-IID data; and the Edge Tier, where IoT device clusters collect, preprocess, and transmit data to fog nodes. PP-HFFL ensures scalable, adaptive, privacy-preserving, and accurate intrusion detection across heterogeneous IoT networks.

Figure 1.

Privacy-Preserving Hierarchical Fog Federated Learning (PP-HFFL) framework for IoT intrusion detection. The hierarchical architecture consists of three tiers: the Cloud Tier, which initializes and aggregates the global IDS model; the Fog Tier, where fog nodes perform client selection, local training with differential privacy (DP), and model personalization to handle non-IID data; and the Edge Tier, where IoT device clusters collect, preprocess, and transmit data to fog nodes. PP-HFFL ensures scalable, adaptive, privacy-preserving, and accurate intrusion detection across heterogeneous IoT networks.

4.1. System Architecture of PP-HFFL

PP-HFFL leverages fog-enabled federated learning for large-scale IoT intrusion detection. Unlike conventional cloud-only systems, fog nodes are positioned closer to edge devices, with moderate computational capabilities for localized data processing and training. This reduces communication latency, network congestion, and dependence on centralized resources, enabling near-real-time intrusion detection.

Figure 1 illustrates the hierarchical three-tier architecture:

Cloud Tier,

Fog Tier, and

Edge Tier, where each layer has distinct roles to ensure scalable, privacy-preserving, and accurate federated learning under non-IID conditions.

Cloud Tier in PP-HFFL. The cloud tier serves as the central coordinator and aggregator. It initializes the global IDS model, optionally pre-trains it, and distributes it to participating fog nodes. During each global round, it collects updated model parameters from fog nodes, aggregates them using Federated Averaging, updates the global model, and redistributes it. New fog nodes joining the system receive the latest global model for local updates and reintegration, supporting dynamic scalability.

Fog Tier in PP-HFFL. The fog tier consists of geographically distributed fog nodes that act as intermediate computation layers between IoT devices and the cloud. Each fog node:

Receives the global model from the cloud.

Performs local training with its own dataset.

Applies differential privacy (DP) via Gaussian noise to gradients before sending them to the cloud.

Optionally personalizes the model to adapt to local non-IID data distributions.

This process repeats iteratively across multiple communication rounds until convergence. New fog nodes seamlessly integrate into the PP-HFFL network.

Edge Tier in PP-HFFL. IoT devices continuously collect raw data, perform lightweight preprocessing (feature extraction, normalization, noise filtering), and transmit processed data to their assigned fog node. Edge devices do not participate directly in federated training due to resource constraints.

4.2. Federated Learning Algorithm in PP-HFFL

The training process of PP-HFFL is governed by the Federated Averaging with Differential Privacy algorithm (FedAvgDP), described in Algorithm 1. Key steps include: 1. Cloud selects a subset of fog clients for each round. 2. Batch Normalization is replaced with Group Normalization for stability under small batches. 3. PrivacyEngine adds Gaussian noise to gradients controlled by and . 4. Local training for E epochs on mini-batches. 5. Local gradients are clipped, noised, and used to update local models. 6. Fog nodes send updated models to the cloud, which aggregates them using FedAvg. 7. The updated global model is broadcasted to all fog nodes. 8. Optional personalization at fog nodes to handle non-IID data.

Privacy, Scalability, and Adaptability in PP-HFFL. PP-HFFL addresses non-IID data, ensures scalable and adaptive operation, and preserves privacy. DP secures model updates, dynamic node addition enables scalability, and personalization improves convergence and accuracy. Fog-layer computation reduces network traffic and latency, supporting real-time intrusion detection.

|

Algorithm 1: PP-HFFL: Federated Averaging with Differential Privacy (FedAvgDP) at Fog Nodes |

-

Require:

C: set of fog clients, G: global dataset, M: global model with parameters , R: max rounds, : learning rate, : client ratio, E: local epochs, : noise multiplier, : clipping norm -

Ensure:

Differentially-private, personalized updated global model M

- 1:

for to R do

- 2:

▹ Select subset of fog clients - 3:

▹ Initialize list for local models - 4:

for each fog client do

- 5:

Initialize ▹ Client receives global model from cloud - 6:

Replace BatchNorm with GroupNorm ▹ Enhances stability for small batches - 7:

Attach PrivacyEngine ▹ Enable DP at client side - 8:

for to E do

- 9:

Sample batch from local dataset

- 10:

Compute predictions

- 11:

Compute loss

- 12:

Compute per-sample gradients

- 13:

Clip gradients:

- 14:

Add Gaussian noise:

- 15:

Update local weights:

- 16:

end for

- 17:

Apply personalization layer for client c ▹ Adapt model to local data distribution - 18:

Evaluate local model and record metrics - 19:

- 20:

end for

- 21:

Aggregate: ▹ Compute global model update - 22:

Update M with aggregated parameters and evaluate on global dataset G

- 23:

end for - 24:

returnM ▹ Differentially-private, personalized global model |

4.3. Security and Privacy Analysis in PP-HFFL

FL-based IDS in fog environments face security and privacy challenges due to decentralized, non-IID data and multi-tier communication. PP-HFFL ensures robust intrusion detection while preserving privacy and maintaining system scalability. Differential privacy (DP) and personalized federated learning (PFL) strategies enhance model resilience and convergence under heterogeneous conditions. The hierarchical architecture enables real-time decision-making at the fog layer, reducing computation at IoT devices and minimizing data transmission to the cloud.

Threat Landscape: Attacks on FL-based systems include

manipulation attacks [

42,

43] and

inference attacks [

44,

45]. Manipulation attacks compromise model integrity, while inference attacks attempt to extract sensitive information. Both training and inference phases are vulnerable, necessitating multi-layered defense mechanisms [

46,

47].

Mitigation via Differential Privacy: DP noise added at fog nodes obscures sensitive gradient information and reduces any single participant’s influence on the global model. Accuracy trade-offs can be managed through adaptive noise calibration or hybrid schemes [

39,

40,

41].

Robustness through Personalized Federated Learning: Personalized FL (PFL) fine-tunes the global model to each fog node’s local data. This limits the impact of poisoned updates, accelerates convergence under non-IID data, and provides implicit anomaly detection [

48,

49].

Privacy Preservation and System Integrity: Only obfuscated gradients or parameters are shared between fog and cloud layers, preventing reconstruction of raw data. PP-HFFL’s distributed design inherently limits large-scale data leakage. Compromised IoT devices can still be detected through collaboratively trained models, ensuring system privacy and integrity across the fog–cloud continuum.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Dataset

We evaluated the proposed PP-HFEL method on the RT-IoT 2022 [

4] and CIC-IoT 2023 [

50] datasets, both specifically designed for IoT intrusion detection. RT-IoT 2022 is relatively smaller in sample size but richer in feature space, whereas CIC-IoT 2023 is significantly larger but with fewer features. Specifically, RT-IoT 2022 contains 79 features and 123,117 samples, while CIC-IoT 2023 has 46 features and 1,048,575 samples. Both datasets are tabular (non-image), making them less complex in raw input dimensionality compared to image corpora, yet still challenging due to heterogeneity and non-IID distributions across devices.

Both datasets exhibit strong class imbalance, which poses significant challenges for federated learning.

Table 2 summarizes the sample counts per class. In CIC-IoT, several classes (e.g.,

DDoSICMPFlood,

DDoSUDPFlood,

DDoSTCPFlood) have more than 100,000 samples, whereas others (e.g.,

ReconPingSweep,

BackdoorMalware) contain fewer than 100. Similarly, in RT-IoT, the largest class (

DOSSYNHping) exceeds 94,000 samples, while smaller classes such as

MetasploitBFSSH and

NMAPFINScan have under 100 samples. CIC-IoT also spans a much wider label space, with 34 distinct classes compared to 12 in RT-IoT.

5.2. Experiment Setup

For the PP-HFFL IDS experiments, we preprocessed the datasets, designed deep neural network (DNN) architectures for both global and local models, and carefully selected hyperparameters. Training data was partitioned across multiple fog clients, enabling hierarchical collaborative learning under various non-IID conditions. To ensure privacy, differential privacy (DP) noise was integrated into the PP-HFFL framework, resulting in a privacy-preserving system. Additionally, personalized federated learning techniques were incorporated to improve local model performance while maintaining overall system scalability.

During federated training, each selected client executed five local epochs before uploading its differentially private model updates to the central server. The server aggregated these updates using FedAvg and broadcasted the updated global model back to all clients. This process was repeated for 300 communication rounds. The same configuration was applied across all experiments to ensure comparability.

All experiments were conducted in two distinct environments to evaluate reproducibility, performance, and robustness across heterogeneous hardware and runtime setups:

Local machine: Visual Studio Code on Windows via Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), Intel Core i5-1235U CPU @ 1.30 GHz, 16 GB RAM, no GPU. Primarily used for end-to-end runs without GPU acceleration.

Cloud environment: GPU-enabled cloud runtime with 2 GB GPU memory and Python 3.10.13 provided by the Digital Research Alliance. Used to confirm reproducibility and evaluate performance on a different hardware/software stack.

All hyperparameters, including learning rate, batch size, and DP noise scale, were kept constant across environments to ensure that performance differences reflected computational characteristics rather than configuration inconsistencies.

5.2.1. Model Architecture and Hyperparameters

We designed a custom multi-layer perceptron (MLP) optimized for one-dimensional IoT feature vectors. The input dimension d is passed through a series of fully connected layers, each followed by batch normalization and ReLU activations. The final hidden layer has 128 units before the output layer, which produces logits for n classes. This architecture is applied consistently across global and local models, with minor adjustments for dataset-specific feature dimensions or class counts.

A complete overview of the architecture and hyperparameters is provided in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Table 3.

Neural network architecture for PP-HFFL IDS.

Table 3.

Neural network architecture for PP-HFFL IDS.

| Layer (type) |

Output |

Param # |

| Input Layer (Linear) |

(128) |

|

| BatchNorm1d |

(128) |

256 |

| ReLU |

(128) |

0 |

| Linear |

(256) |

|

| BatchNorm1d |

(256) |

512 |

| ReLU |

(256) |

0 |

| Linear |

(256) |

|

| BatchNorm1d |

(256) |

512 |

| ReLU |

(256) |

0 |

| Linear |

(128) |

|

| BatchNorm1d |

(128) |

256 |

| ReLU |

(128) |

0 |

| Output Layer (Linear) |

(n) |

|

Table 4.

Hyperparameters for PP-HFFL IDS training.

Table 4.

Hyperparameters for PP-HFFL IDS training.

| Name |

Value |

| Aggregation algorithm |

FedAvg |

| Total classes |

12, 7 |

| Input dimension |

79, 46 |

| Participation ratio |

1.0 |

| Max training rounds |

300 |

| Local epochs per round |

5 |

| Batch size |

64 |

| Optimizer |

SGD |

| Initial learning rate |

0.03 |

| Weight decay |

1e-5 |

| Noise multiplier |

1.0 |

| Max_grad_norm |

1.0 |

Table 5.

Mapping the 34 CIC-IoT 2023 malware classes to 7 consolidated categories, with sample counts before and after downsampling, aligned with PP-HFFL.

Table 5.

Mapping the 34 CIC-IoT 2023 malware classes to 7 consolidated categories, with sample counts before and after downsampling, aligned with PP-HFFL.

| New Class |

Old Class |

Count |

Downsampled Count |

| Flood Attacks |

DDoSICMPFlood, DDoSTCPFlood, DDoSUDPFlood, DoSTCPFlood, DoSUDPFlood, DoSSynFlood, DDoSPSHACKFlood, DDoSRSTFINFlood, DoSHTTPFlood, DDoSSYNFlood, DDoSSynIPFlood, DDoSHTTPFlood |

921,428 |

92,143 |

| Botnet/Mirai Attacks |

MiraiGreethFlood, MiraiUDPplain, MiraiGreipFlood |

59,233 |

5,924 |

| Benign |

BenignTraffic |

24,476 |

2,448 |

| Spoofing/MITM |

DNSSpoofing, MITMArpSpoofing |

11,053 |

1,106 |

| Reconnaissance |

ReconHostDisc, ReconOSScan, ReconPortScan, ReconPingSweep |

7,136 |

714 |

| Backdoors & Exploits |

BackdoorMalware, UploadingAttack, BrowserHijacking, DictionaryBF |

563 |

57 |

| Injection Attacks |

SqlInjection, CommandInjection, XSS |

299 |

30 |

5.2.2. Data Preprocessing

For both centralized ML models and PP-HFFL IDS experiments, we used the original RT-IoT 2022 and CIC-IoT 2023 datasets with a uniform label assignment (label split) strategy for federated learning. Centralized ML achieved 99.49% and 90.64% accuracy on RT-IoT and CIC-IoT, respectively, while FL reached above 99.0% on RT-IoT and above 85.0% on CIC-IoT under the same 300-round training configuration. The primary challenge for FL and PP-HFFL lies in the computational cost and time required for global training, particularly on CIC-IoT, which contains 1,048,575 samples spanning 34 classes.

To reduce computational complexity and improve training efficiency, we

regrouped the 34 CIC-IoT classes into 7 broader categories and

downsampled all classes by a factor of 10.

Table 5 presents the preprocessing details: the first two columns map the original 34 classes to the 7 consolidated categories, while the last two columns report class sizes after regrouping and downsampling. This preprocessing not only simplifies CIC-IoT classification but also improves performance: on the downsampled CIC-IoT dataset, centralized ML achieved

99.05% accuracy, while PP-HFFL achieved

98.56%.

Importantly, this downsampling preserves the non-IID characteristics of the data, ensuring the validity of our PP-HFFL IDS experiments. Additionally, for both datasets, fog clients with fewer than five samples were excluded from FL training to prevent unreliable contributions from sparsely populated local models. This preprocessing strategy balances computational efficiency with data representativeness, supporting robust and scalable PP-HFFL training.

5.3. Effect of non-IID Data on PP-HFFL Training

In the non-IID setting, we investigated the combined effects of class imbalance and class absence on

privacy-preserving hierarchical federated learning (PP-HFFL) training. Both RT-IoT and CIC-IoT datasets are inherently imbalanced, and to preserve this characteristic in PP-HFFL, we applied a uniform label assignment (label split) to distribute all data across fog clients without performing any rebalancing. To simulate controlled class missingness per client, we limited the

maximum number of classes assigned to each client as follows: for RT-IoT,

; for CIC-IoT,

. The single-class-per-client scenario was deliberately excluded, as it represents an extreme case that can introduce a positive-class issue [

51]. Additionally, we varied the number of fog clients (10, 50, 100, 200, 400) to analyze the impact of client scale on PP-HFFL training accuracy.

Table 6 represents the global

PP-HFFL IDS accuracy on test data under these non-IID settings for both RT-IoT 2022 and CIC-IoT 2023 datasets. When clients have sufficient class diversity (RT-IoT: 12 or 6 classes; CIC-IoT: 7 or 3 classes), PP-HFFL accuracy remains close to that of the centralized model because local updates are more representative and client drift is limited. In contrast, when each client has very few classes (e.g., 3 or 2), overall accuracy becomes highly dependent on the number of clients and the random assignment of classes. For example, with few clients, many classes are absent (CIC-IoT with 2 classes/client and 10 clients achieves only

accuracy), whereas increasing the number of clients improves coverage significantly (CIC-IoT with 2 classes/client reaches approximately

for

clients).

RT-IoT exhibits higher variance under skewed splits, with sharp drops in accuracy (e.g., at 100 clients and 3 classes/client), followed by partial recovery as the federation expands (e.g., and at 400 clients and 2 classes/client). These results highlight two key insights for PP-HFFL: (i) maintaining sufficient class diversity per client stabilizes hierarchical federated training, and (ii) in extreme skew scenarios, increasing the number of clients mitigates missing-class effects by improving overall class coverage across the federation.

5.4. Effect of Differential Privacy in PP-HFFL Accuracy

To ensure data privacy in our

privacy-preserving hierarchical federated learning (PP-HFFL) framework, we integrate differential privacy (DP) into the client-side training using Opacus [

52], a PyTorch library designed for privacy-preserving deep learning. In this PP-HFFL setup, each fog client applies the Gaussian noise mechanism with a

noise_multiplier of 1.0, adding noise sampled from a normal distribution (standard deviation 1.0) to the aggregated local gradients. This noise level is carefully chosen to balance privacy protection with model utility.

Additionally, max_grad_norm is set to 1.0, clipping each individual sample’s gradient to a maximum L2 norm of 1.0 before noise addition. This bounds the sensitivity of each data point, ensuring that no single IoT sample disproportionately affects the local model update. After local training in each round, clients upload differentially private model updates to the PP-HFFL server for hierarchical aggregation.

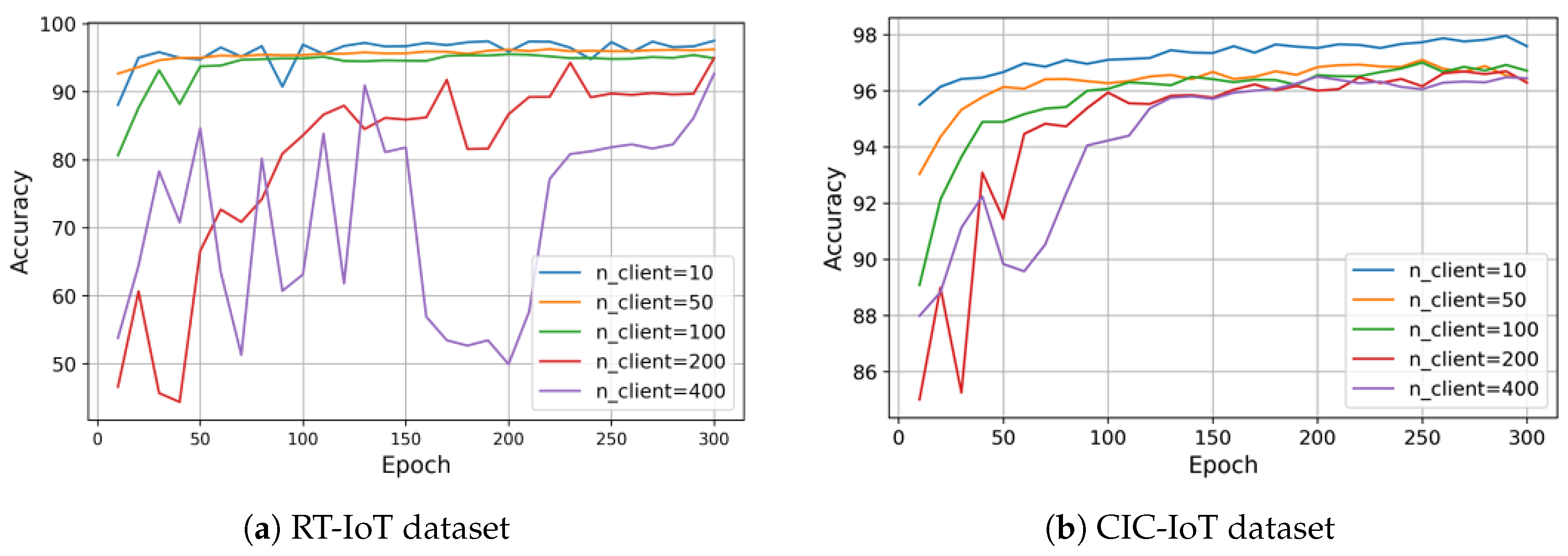

Figure 2.

Accuracy of PP-HFFL global models on test data under differential privacy (DP) with varying fog client counts. Across 300 communication rounds, DP reduces accuracy by approximately 1.71–5.78% for RT-IoT and 1.33–2.65% for CIC-IoT, demonstrating the accuracy–privacy tradeoff in privacy-preserving hierarchical federated learning.

Figure 2.

Accuracy of PP-HFFL global models on test data under differential privacy (DP) with varying fog client counts. Across 300 communication rounds, DP reduces accuracy by approximately 1.71–5.78% for RT-IoT and 1.33–2.65% for CIC-IoT, demonstrating the accuracy–privacy tradeoff in privacy-preserving hierarchical federated learning.

The DP mechanism in PP-HFFL operates through the following steps during client-side training:

Per-sample gradient computation: Gradients are computed individually for each IoT sample rather than the entire batch.

Gradient clipping and accumulation: Each sample gradient exceeding the L2 norm threshold is clipped, then aggregated to form the batch gradient.

Noise addition: Gaussian noise is added to the aggregated gradient to mask individual contributions.

Gradient scaling: The noisy gradient is normalized by the effective batch size to maintain correct learning dynamics.

Optimizer step: The privacy-preserving gradient is applied to update the local model parameters, which are then uploaded to the hierarchical PP-HFFL server.

This integration of DP into PP-HFFL ensures that privacy guarantees are maintained without significantly compromising model performance, enabling secure collaborative learning across heterogeneous IoT devices.

Figure 2 illustrates the accuracy–privacy tradeoff on test data in our

PP-HFFL IDS when differential privacy (DP) is applied. For the RT-IoT dataset (12 classes, 79 features), accuracy fluctuates during the early communication rounds, particularly with 200–400 fog clients, due to the stronger DP noise, before stabilizing. Non-DP PP-HFFL achieves accuracy above

, while the DP-enabled PP-HFFL model converges to roughly 94–

, representing a drop of

–

percentage points. This sensitivity is largely attributable to the higher number of classes and input features, which amplifies the impact of DP noise on local updates.

In comparison, the CIC-IoT dataset (7 classes, 46 features) exhibits smoother accuracy curves and a smaller reduction under DP: non-DP PP-HFFL maintains above accuracy, and DP reduces it to around 96–, a decrease of – points. The simpler class structure and lower input dimensionality reduce susceptibility to DP noise, allowing the hierarchical PP-HFFL model to retain strong performance across varying client counts.

Overall, these results confirm that DP slightly reduces model accuracy, with a more pronounced effect for datasets with higher complexity or larger numbers of fog clients. Nonetheless, both datasets achieve high final accuracy, demonstrating that differential privacy can be effectively incorporated into PP-HFFL without severely compromising performance. This highlights the feasibility of deploying privacy-preserving, hierarchical federated learning in real-world IoT intrusion detection systems while maintaining practical utility.

5.5. Personalized PP-HFFL

In the personalized PP-HFFL experiments, we evaluated two key scenarios: (i) improving a trained global model when it performs poorly on a fog node’s local data, under both non-DP and DP settings; and (ii) enabling a newly joined fog node to adapt the global PP-HFFL model using its local data.

For the first scenario, we selected a global PP-HFFL model with suboptimal performance based on

Table 6. For the second, we retrained the global model on the new client’s local data, analogous to transfer learning within the PP-HFFL context. Both scenarios were tested under non-DP and DP conditions.

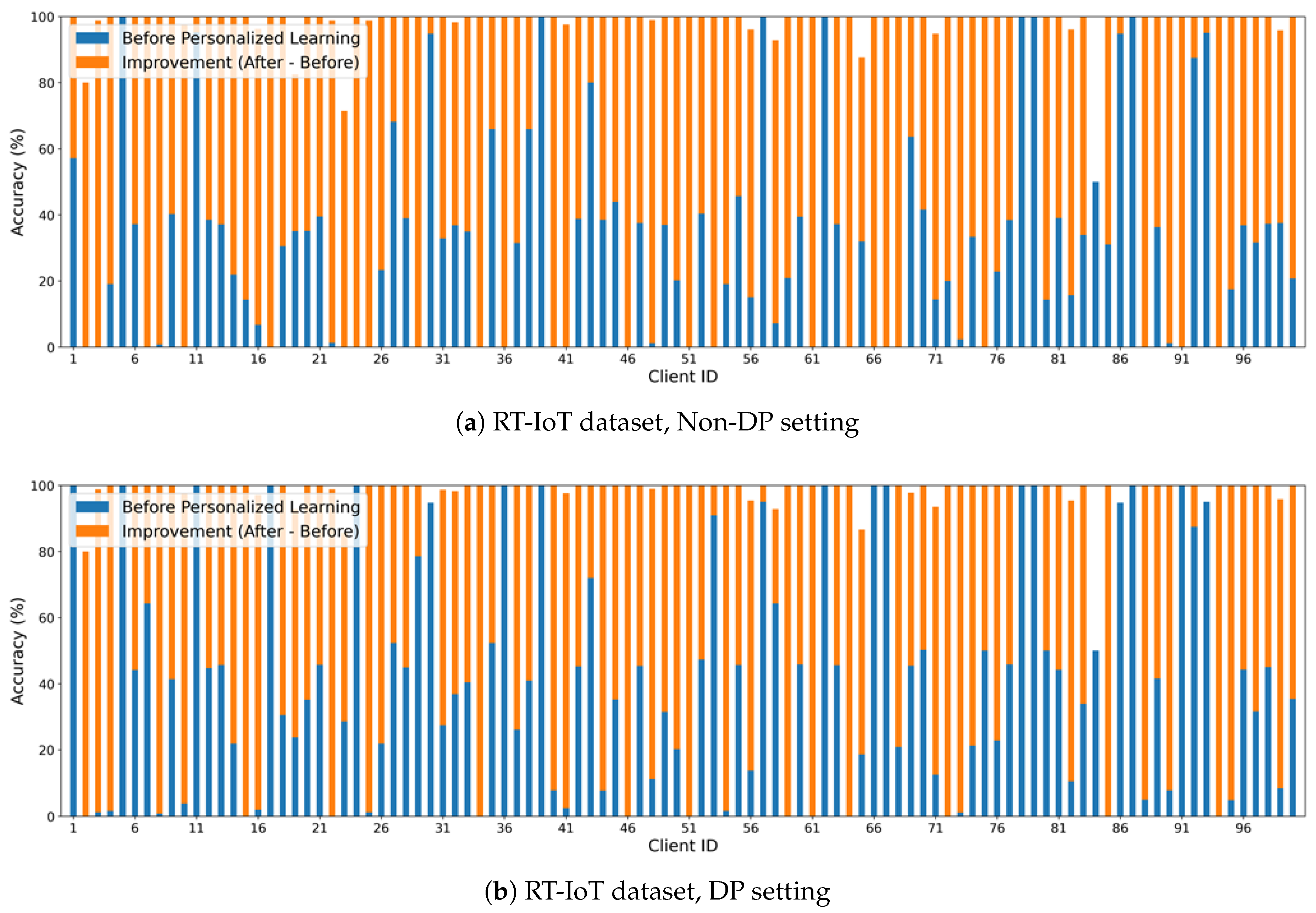

Figure 3 (a) shows the effect of

personalized PP-HFFL in the non-DP setting for the RT-IoT dataset, with 100 fog clients and 2 classes per client. The baseline global model accuracy was 37.99%. Green bars represent per-client accuracy before personalization, and orange bars show improvements after personalization. Clients with fewer than five samples were excluded, explaining gaps in the plot. Most clients benefit substantially, with local performance often approaching that of a centralized ML model trained on the full dataset. However, improvements are not uniform, as client datasets vary in size and label distribution. Some residual bias remains due to extreme non-IID conditions. Overall, the results confirm that

personalization effectively boosts local performance when the global PP-HFFL model underperforms.

The trend is similar in the DP setting (

Figure 3 (b)). Personalization provides an even larger performance boost under DP, since baseline DP PP-HFFL models typically perform worse due to added noise. For newly joined fog nodes, personalization enables the hierarchical global model to efficiently adapt to local data, akin to transfer learning, improving performance while preserving privacy.

5.6. Discussion and Limitations

Our experiments on RT-IoT 2022 and CIC-IoT 2023 datasets highlight several key findings in the context of PP-HFFL-based IDS:

The PP-HFFL IDS maintains near-centralized accuracy when fog clients retain sufficient class diversity. Performance drops sharply under extreme non-IID splits, though increasing the number of clients partially mitigates this by improving overall class coverage within the hierarchical federation.

Integrating differential privacy (DP) in PP-HFFL introduces a modest accuracy reduction (approximately 1.3–5.8 points), with a larger impact observed for the higher-dimensional RT-IoT dataset. Nevertheless, both datasets achieve strong final accuracy, demonstrating that DP can be incorporated into PP-HFFL without severely compromising model utility.

Personalization within PP-HFFL significantly enhances local model performance, particularly under DP. Many fog clients approach baseline centralized performance, and newly joined nodes can efficiently adapt the hierarchical global model via a transfer-learning-like mechanism, preserving privacy while improving local accuracy.

Limitations of the current PP-HFFL-based IDS study include:

Evaluation is restricted to two tabular IoT datasets (RT-IoT 2022 and CIC-IoT 2023) and a single type of non-IID partitioning strategy. Broader dataset diversity and more complex data distributions should be considered in future work.

Differential privacy (DP) settings were fixed (noise_multiplier and max_grad_norm) without performing full -accounting; more rigorous privacy analyses could quantify the tradeoff between privacy guarantees and model utility in PP-HFFL.

The study primarily focuses on accuracy; other important metrics such as F1-score, precision, and recall were not extensively analyzed. Evaluating these metrics would provide a more comprehensive assessment of PP-HFFL performance.

The experimental setup assumes synchronous FedAvg aggregation and excludes fog clients with very few samples. Future investigations should consider partial client participation, heterogeneous resource constraints, and a wider range of non-IID scenarios to better reflect real-world IoT environments.

6. Conclusion

This work presented a Privacy-Preserving Hierarchical Fog Federated Learning (PP-HFFL) framework for Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), designed to overcome the limitations of resource-constrained IoT environments. By offloading model training and decision-making to fog nodes, the proposed approach alleviates computational and communication burdens on IoT devices while simultaneously addressing scalability, privacy, and data heterogeneity challenges inherent in distributed IoT ecosystems. In PP-HFFL, a global model is trained at the cloud using the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm, with fog nodes acting as federated clients. To safeguard sensitive information, client-side Differential Privacy (DP) mechanisms are incorporated into local training, protecting model updates from potential inference attacks. Additionally, model personalization is applied at the fog layer to fine-tune local models for each node, enabling adaptation to dynamic environments and seamless integration of newly joined nodes into the federated network.

The framework was experimentally validated using two benchmark IoT datasets—

RT-IoT 2022 and

CIC-IoT 2023. The evaluations demonstrate that PP-HFFL achieves detection accuracy comparable to centralized approaches, even under heterogeneous data distributions and varying client scales. Incorporating differential privacy introduces a modest trade-off between privacy and performance, consistent with prior DP-FL studies [

40,

53]. Importantly, model personalization substantially enhances local accuracy, particularly in DP-enabled settings, ensuring that each fog node benefits from context-specific model refinement. These results confirm that PP-HFFL maintains strong privacy guarantees while providing high detection effectiveness across diverse fog computing environments.

Overall, the proposed PP-HFFL–based IDS demonstrates robustness, scalability, and adaptability for real-world IoT intrusion detection scenarios. The experimental results validate its stability under varying class distributions, dataset complexities, and client populations. Furthermore, the hierarchical architecture of PP-HFFL ensures efficient communication, rapid adaptation to non-IID data, and resilience to dynamic client participation.

Future research directions include: (i) extending the analysis to broader non-IID distributions and complex IoT deployments, (ii) handling partial, asynchronous, or intermittent client participation, (iii) incorporating heterogeneous resource constraints across fog nodes and IoT devices, (iv) employing more rigorous privacy accounting mechanisms such as Rényi DP [

27], and (v) performing large-scale, end-to-end evaluation on operational fog computing testbeds. These enhancements aim to further improve the reliability, efficiency, and privacy-preserving capacity of PP-HFFL for next-generation IoT networks, ultimately supporting secure and scalable deployment of intelligent IoT infrastructures.

References

- Atzori, L.; Iera, A.; Morabito, G. The internet of things: A survey. Computer networks 2010, 54, 2787–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, Q. A survey on IoT security: Threats, attacks, and countermeasures. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2025, 12, 1245–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Axios. Hackers breach thousands of security cameras, exposing Tesla, jails, hospitals. https://www.axios.com/security-camera-hack-verkada-b6db6e5c-d8c0-4a3e-a3b6-3c9f8b0a5f7c.html, 2021. Accessed: 2025-10-07.

- Sharmila, B.S.; Nagapadma, R. Quantized deep neural network for intrusion detection in IoT networks. Computers & Security 2023, 126, 103042. [Google Scholar]

- Abusitta, A.; Bellaiche, M.; Dagenais, M.; Halabi, T. Deep learning-enabled anomaly detection for IoT systems. Internet of Things 2023, 21, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A.y. Federated learning of deep networks using model averaging. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.05629. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A.y. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2017, pp. 1273–1282.

- Arya, V.; Das, S.K. Intruder detection in IoT systems using federated learning. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 7012–7025. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi, M.; Zantout, H.; Alouini, M.S. Federated learning for intrusion detection in IoT networks: A comprehensive survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Friha, O.; Ferrag, M.A.; Shu, L.; Maglaras, L.; Wang, X. FELIDS: Federated learning-based intrusion detection system for agricultural IoT. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2022, 165, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpini, A.; Carrega, A.; Bolla, R. Clustering-based federated learning for intrusion detection in IoT. Computer Networks 2023, 224, 109608. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.M.; Kamruzzaman, J.; Hassan, M.M.; Imam, T.; Gordon, S. Federated learning for IoT intrusion detection. Computers & Security 2023, 125, 103033. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Lai, L.; Suda, N.; Civin, D.; Chandra, V. Federated learning with non-IID data. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.00582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Bonawitz, K.; Charles, Z.; Cormode, G.; Cummings, R.; et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Jin, Y. Federated learning on non-IID data: A survey. Neurocomputing 2021, 465, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.; Phanishayee, A.; Mutlu, O.; Gibbons, P. The non-IID data quagmire of decentralized machine learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 4387–4398.

- Hsu, T.M.H.; Qi, H.; Brown, M. Measuring the effects of non-identical data distribution for federated visual classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.06335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Pei, J.; Zhang, Y. Personalized federated learning: A meta-learning approach. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.07078. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V.; Chiang, C.K.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.S. Federated multi-task learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, Y.; Mohri, M.; Ro, J.; Suresh, A.T. Three approaches for personalization with applications to federated learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Chung, J.; Yin, D.; Ramchandran, K. An efficient framework for clustered federated learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 19586–19597.

- Dwork, C.; McSherry, F.; Nissim, K.; Smith, A. Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis. In Proceedings of the Theory of cryptography conference. Springer, 2006. 265–284.

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A.; et al. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Foundations and Trends in Theoretical Computer Science 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlingsson, Ú.; Pihur, V.; Korolova, A. Randomized aggregatable privacy-preserving ordinal response. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2014, pp. 1054–1067.

- Dong, J.; Roth, A.; Su, W.J. Gaussian differential privacy. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 2022, 84, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, I. Rényi differential privacy. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 30th computer security foundations symposium (CSF). IEEE, 2017, pp. 263–275.

- Li, Z.; Sharma, V.; Mohanty, S.P. FLEAM: A federated learning empowered architecture to mitigate DDoS in industrial IoT. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 18, 4059–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Huthaifi, R.; Steingrímsson, G.; Yan, Y.; Hossain, M.S. Federated mimic learning for privacy preserving intrusion detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 193372–193383. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, L.; Huang, J. DeepFed: Federated deep learning for intrusion detection in industrial cyber-physical systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2020, 17, 5615–5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; Tout, H.; Talhi, C.; Mourad, A. Internet of things intrusion detection: Centralized, on-device, or federated learning? IEEE Network 2020, 34, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, M.; Roy, K.; Kelly, J.; Okoye, C.T. FL-IDS: Federated learning-based intrusion detection system for IoT networks. Cluster Computing 2024, 27, 743–759. [Google Scholar]

- Imteaj, A.; Thakker, U.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Amini, M.H. Federated learning for resource-constrained IoT devices: Panoramas and state-of-the-art. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2002.10610. [Google Scholar]

- Javeed, D.; Gao, T.; Khan, M.T. Fog computing and federated learning-based intrusion detection system for Internet of Things. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2023, 107, 108651. [Google Scholar]

- Bensaid, S.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W.; Alsaeedi, A.; Al-Sarem, M. Securing IoT via fog-layer federated learning. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2025, 215, 103635. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, S.; Nepal, S.; Deng, R. Distributed intrusion detection system for IoT based on federated learning and edge computing. Computers & Security 2022, 115, 102622. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, R.; Misra, S.; Dutta, P.K. FogFL: Fog-assisted federated learning for resource-constrained IoT devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- de Souza, C.A.; Westphall, C.M.; Machado, R.B. F-FIDS: Federated fog-based intrusion detection system for smart grids. International Journal of Information Security 2023, 22, 1059–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Chang, V.; Ding, W.; et al. Privacy-preserving federated learning: A comprehensive survey. Information Fusion 2024, 104, 102234. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.C.; Klein, T.; Nabi, M. Differentially private federated learning: A client level perspective. In Proceedings of the NIPS Workshop on Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning, 2017.

- Bonawitz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Kreuter, B.; Marcedone, A.; McMahan, H.B.; Patel, S.; Ramage, D.; Segal, A.; Seth, K. Practical secure aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2017, pp. 1175–1191.

- Bagdasaryan, E.; Veit, A.; Hua, Y.; Estrin, D.; Shmatikov, V. How to backdoor federated learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS). PMLR, 2020, Vol. 108, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2938–2948.

- Blanchard, P.; El Mhamdi, E.M.; Guerraoui, R.; Stainer, J. Machine learning with adversaries: Byzantine tolerant gradient descent. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Shokri, R.; Stronati, M.; Song, C.; Shmatikov, V. Membership inference attacks against machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 3–18.

- Nasr, M.; Shokri, R.; Houmansadr, A. Comprehensive privacy analysis of deep learning: Passive and active white-box inference attacks against centralized and federated learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), IEEE, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 739–753.

- Sun, T.; Kairouz, P.; Suresh, A.T.; McMahan, H.B. Threats and countermeasures in federated learning: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, M.; Jin, R.; et al. A survey on privacy and security issues in federated learning: Threats, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2023, 25, 1234–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, V.; Kulkarni, M.; Pant, A. Survey of personalization techniques for federated learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.08673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ji, S.; Yang, T.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Y. Towards personalized federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 33, 5005–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.C.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferreira, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CIC-IoT2023: A real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.X.; Rawat, A.S.; Menon, A.K.; Kumar, S. Federated learning with only positive labels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR, 2020, Vol. 119, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 10946–10956.

- Meta, AI. Opacus: User-friendly differential privacy library in PyTorch. https://opacus.ai/, 2021. Accessed: 2025-10-07.

- Bonawitz, K.; Eichner, H.; Grieskamp, W.; Huba, D.; Ingerman, A.; Ivanov, V.; Kiddon, C.; Konečný, J.; Mazzocchi, S.; McMahan, H.B.; et al. Towards Federated Learning at Scale: System Design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd SysML Conference, Stanford, CA, USA, 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).