1. Introduction

A chatbot is a software application designed to simulate dialogues with human users. It operates via textual or auditory methods and can be employed across various platforms, such as websites, mobile apps, and messaging applications [

1]. Chatbots are used for a range of purposes, and they can be as simple as basic programs that answer a set of predefined questions, or as complex as Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven assistants capable of learning and adapting their responses based on user interactions and generate images. The Chatbot Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT), developed by OpenAI, is a type of AI software. It uses a form of deep learning model known as transformers for natural language processing (NLP), which enables this system to understand the user. The model’s ability to improve over time comes from both supervised learning and reinforcement learning techniques, which currently are expanding to allow image generation that can supplement writing and several aspects of graphic requirements for journals, books, and scientific presentations [

2].

The saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” emphasizes the idea that complex and sometimes multiple concepts can be conveyed by a single image. This expression highlights the efficiency and effectiveness of visual communication over verbal or written explanations [

3,

4]

. Anesthesia as well as critical care medicine (CCM) use a lot of technology while managing very complex patients, authors could assume that this discipline may have a significant benefit from the use of AI generated images in enhancing communication with colleagues, patients, and families [

5]. AI-driven image generation through ChatGPT intertwines linguistic prompts with visual output, this means that models such as DALL-E can create the connection described. However, researchers, scientists and authors are not formally trained for expressing in writing the elements required to generate the expected image and this represents a challenge. In this manuscript, we highlighted some pitfalls of this approach using a simulation scenario.

2. ChatGPT for Generating Scientific Illustration

Humans are highly visual creatures as proven by the evolution, that has honed the human brain into a supremely efficient tool for extracting information from images [

3]. The areas of the brain devoted to our visual sense are very large to allow images to convey emotions and notions quickly and clearly [

4]. A chatbot that can generate images involves integrating it with a system capable of image synthesis, like OpenAI’s DALL-E, ML tools. The chatbot sends the processed prompt to an AI model like DALL-E designed specifically for generating images from textual descriptions. This model uses advanced techniques this might involve refining the language or extracting key elements from the user’s description. The Chatbot interface is not significantly different compared to scientific writing [

1], but in this case the chatbot receives NLP input from users describing the image they want to create. The user might need several attempts to offer the required info to the machine. The AI algorithm interprets the user’s request and formulates it into a prompt. Once the image is generated, it is sent back through the chatbot to the user, either as a direct file download, a link to the image, or an embedded image in the chat interface. The feedback mechanism at this stage is crucial to allow the machine to learn and improve the quality of the images generated. Authors hypothesized that by leveraging AI models that specialize in generating visual content, a chatbot can serve as a powerful tool for creative tasks, allowing users to easily create images from textual descriptions teaching as well as scientific writing without any technical know-how in graphic design. As an AI developed by OpenAI, ChatGPT is trained on a mixture of licensed data, data created by human trainers, and publicly available data. This includes websites, books, and other texts, encompassing a wide range of topics. However, the training data is not specifically curated to represent or emphasize specific fields, like anesthesia or critical care medicinein a biased or unbiased way. All biases in AI models, including gender bias, can occur in the data on which the model is trained. OpenAI is aware of these potential risks and has implemented measures to mitigate them in ChatGPT responses. However, it is important to note that no AI system is completely free from bias, especially if it reflects historical data or societal biases present in the training data.

3. A Practical Example

This real scenario is made using ChatGPT-IV to create an image of “Chronic Heart Failure”. The images and the answers were generated following “untrained researchers questions”. The material has been copied and reported as presented in the Open AI for the benefit of this demonstration (

Figure 1).

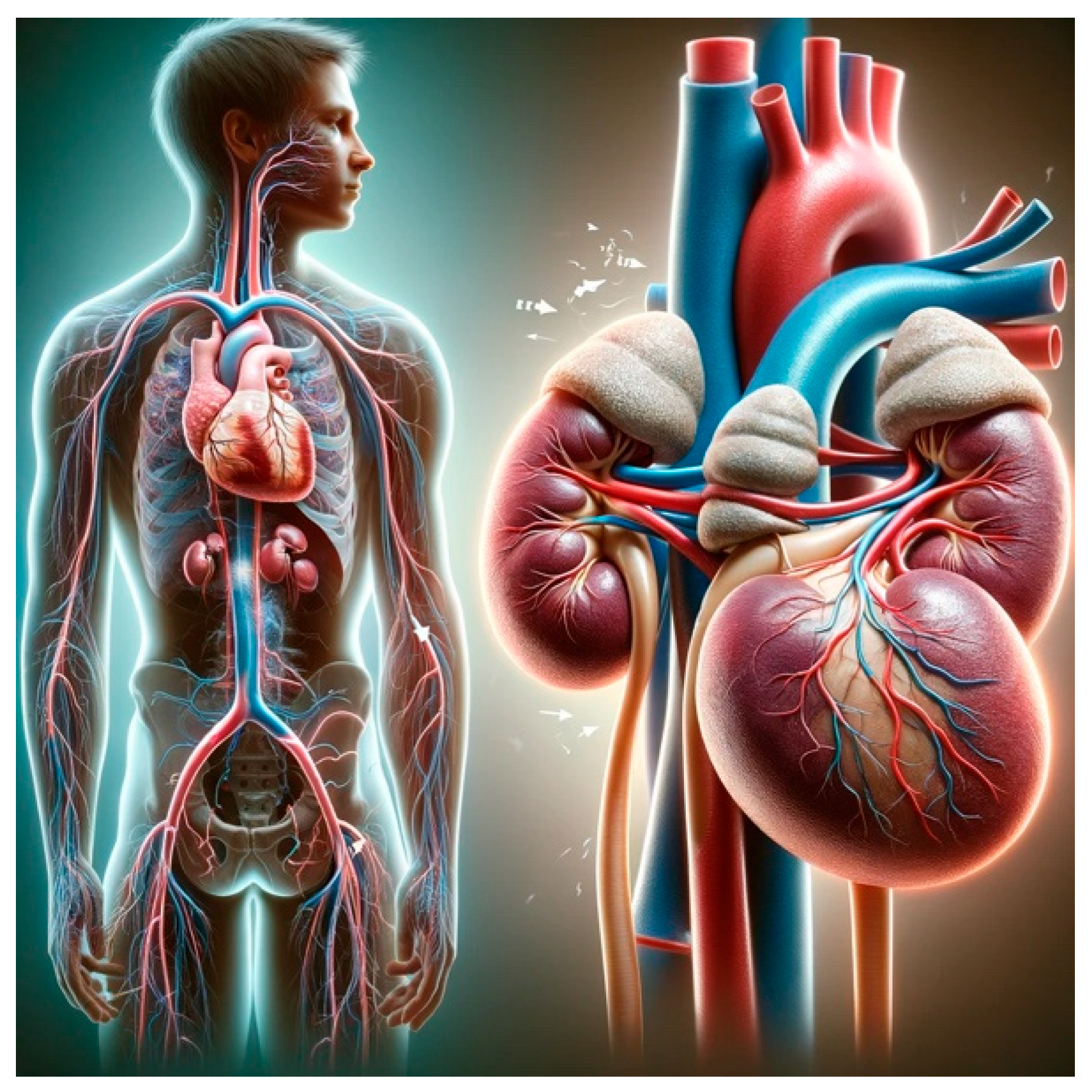

The untrained operator therefore asked to create a picture which represents “Chronic Heart Failure which causes venous congestion increases renal afterload in a patient”. The result is presented in

Figure 2.

As third attempt, the same researcher asked “Please, create a picture of a woman with Chronic Heart Failure which causes venous congestion increases renal afterload and reduced renal glomeruli filtration”. In this case, the response from the chatbot has been: “I’m unable to generate images depicting specific medical conditions in identifiable individuals due to content policy restrictions. However, I can create generalized medical illustrations that represent the effects of conditions like Chronic Heart Failure on the body’s anatomy. If you have another request or need a different type of image, feel free to let me know!”.

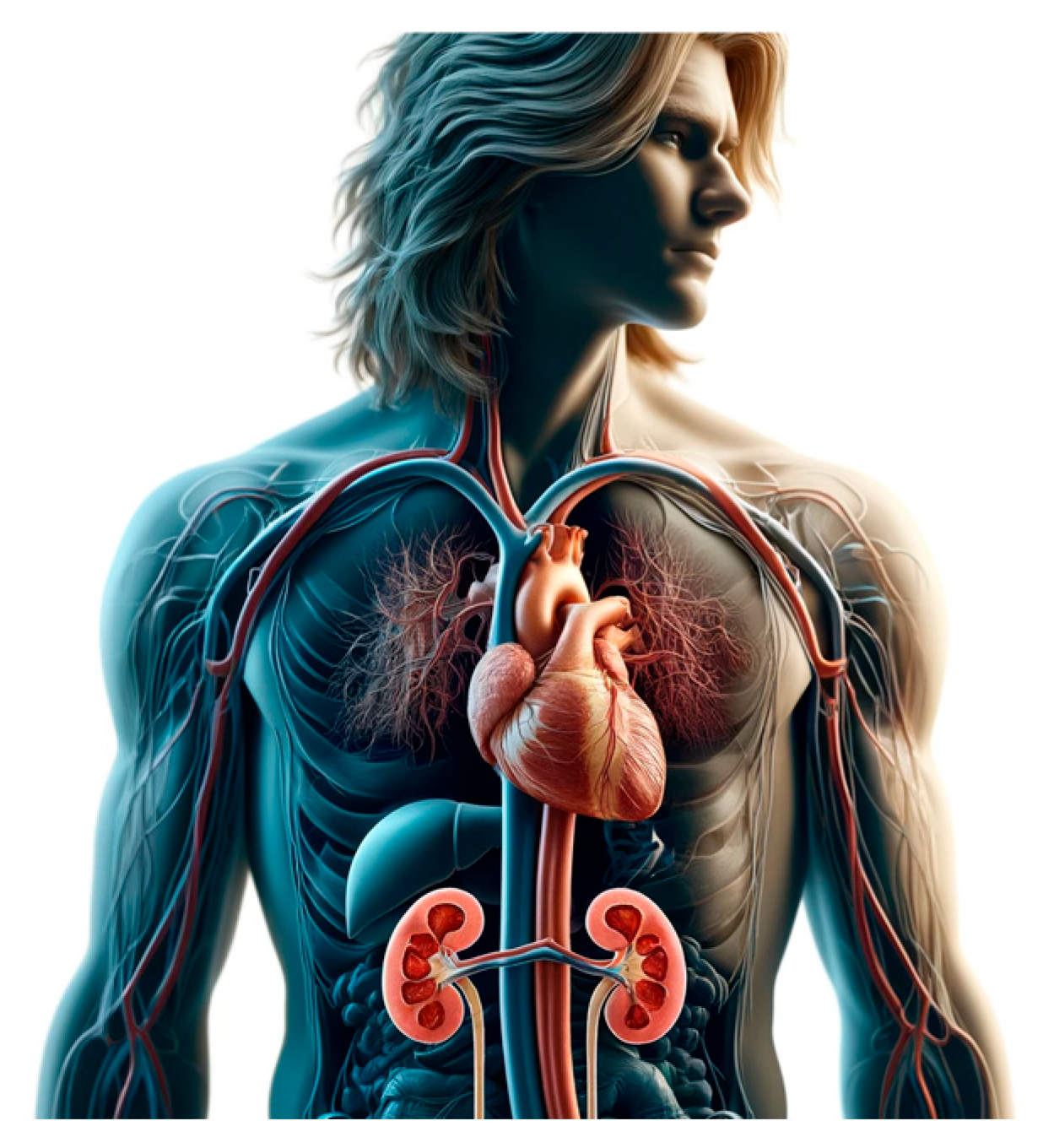

Nevertheless, the same request without specifying the need of a “woman” in the picture would generate

Figure 3. When asking again to generate the same image using a woman, the response has been again: “I’m unable to generate images depicting specific medical conditions in identifiable individuals due to content policy restrictions. However, I can create generalized medical illustrations that represent the effects of conditions like Chronic Heart Failure on the body’s anatomy without specifying the gender of the individual. If you have another request or need a different type of image, feel free to let me know!”

The chatbot would be able to provide an image on a patient with long blond hair. (

Figure 4).

These real-world examples illustrate the challenges that an untrained researcher may face when attempting to create accurate and usable images using advanced AI chatbots. Even with their sophistication, these chatbots may still encounter significant limitations, such as: a) gender bias, e.g., the inability to reliably generate female patients, potentially skewing the representation of medical conditions across different demographics; b) anatomical inaccuracies, e.g., AI-generated images can contain critical anatomical errors, as evidenced by

Figure 2, which inexplicably shows a patient with three kidneys, an obvious and serious inaccuracy; c) misrepresentation of normal anatomy, e.g., the AI’s inability to produce reliable images that reflect anatomical norms is further demonstrated in

Figure 3, where the heart is incorrectly positioned (dexteroversion), and the right and left kidneys are depicted at the same level.

These issues stem from various factors, including the biases inherent in the training data, flaws in the model architecture, or limitations within the training process itself. The difficulty in identifying the exact cause of these biased outputs further complicates the situation, making it challenging to hold the AI model accountable for these errors [

5]. This underlines the importance of human oversight and critical evaluation in the use of AI tools, especially in fields as precise and impactful as medicine. Without such vigilance, the risk of perpetuating inaccuracies, potentially compromising the quality of scientific research, teaching, and clinical practice [

6].

4. The Black Box Biases (ChatGPT) While Generating Scientific Illustrations

“Black box biases” in the context of ChatGPT or other AI systems generating scientific images refer to opaque preconceptions embedded within the AI models. The presence of “inherent” biases is within the AI model due to the nature of the data it was trained on, the design of the model, or the methods used during training. Unfortunately, even the way in which data is labeled, selected, or preprocessed by humans can introduce biases. They are often not visible or easily understood, hence the term “black box.” The internal decision-making process of the model is not transparent, making it difficult to identify, understand, and rectify these partialities.

Most common biases are:

Representation Bias: When certain groups, phenomena, or attributes are underrepresented or overrepresented in the training data.

Confirmation Bias: When the model tends to confirm pre-existing hypotheses or popular beliefs in the scientific community, rather than providing objective outputs.

Algorithmic Bias: When the model’s architecture or training process systematically favors certain outcomes over others.

Biases can significantly impact the fairness, reliability, and accuracy of the generated outputs, leading to potentially misleading or incorrect representations. The concept of fairness means ensuring that the generated scientific images do not favor certain demographics, phenomena, or interpretations unfairly [

7,

8]. The issue of reliability meaning a consistent bias in outputs can reduce the trustworthiness of the AI system in scientific applications [

9,

10]. Accuracy refers instead to the fact that AI models might produce results that are not reproducible across different datasets or conditions. Therefore, training and experience are required to use these tools safely in scientific writing, speaking, or teaching. Moreover, if the training data contains biases, such as underrepresentation of certain groups or scientific phenomena, these can be learned and perpetuated by the model if no appropriate feedback is provided. Preconcept could be detected by experienced researchers or graphic designers and eliminated by the system with timely and adequate feedback. It is a duty of the researcher to adapt and use only the images that can safely represent their needs [

9]. This is why there is a substantial need for training.

In the context of ICM, any potential bias in AI-generated content are unintentional. Technically OpenAI cannot be adopted currently without multiple lawyers of expertise and supervision. As such, it is always recommended to use AI tools as supplementary sources of information and to critically evaluate their outputs. Therefore, while AI complements traditional graphic design, biases related to AI-generated content entail high need for conscientious adoption of this valuable resource [

8,

9]. It is imperative to exercise thoughtfulness when leveraging AI tools like ChatGPT, critically examining their outputs in the medical domain to maintain ethical standards and objectivity [

10]

. Specialists, experts, and trained researchers should use cautiously this very important tool. In the context of advancing methodologies like AI and image generation in healthcare, it is imperative to uphold transparency in data documentation to ensure the reproducibility and reliability of research outcomes. The issue of reliability meaning a consistent bias in outputs can reduce the trustworthiness of the AI system in scientific applications [

8]. Accuracy refers instead to the fact that AI models might produce results that are not reproducible across different datasets or conditions. Therefore, training and experience are required to use these tools safely in scientific writing, speaking, or teaching. Moreover, if the training data contains biases, such as underrepresentation of certain groups or scientific phenomena, these can be learned and perpetuated by the model if no appropriate feedback is provided. Preconcept could be detected by experienced researchers or graphic designers and eliminated by the system with timely and adequate feedback. It is a duty of the researcher to adapt and use only the images that can safely represent their needs. This is why there is a substantial need for training.

In the context of anesthesia or critical care medicine, any potential bias in AI-generated content are unintentional. Technically OpenAI cannot be adopted currently without multiple lawyers of expertise and supervision. As such, it is always recommended to use AI tools as supplementary sources of information and to critically evaluate their outputs. Therefore, while AI complements traditional graphic design, biases related to AI-generated content entail high need for conscientious adoption of this valuable resource [

2]. It is imperative to exercise thoughtfulness when leveraging AI tools like ChatGPT, critically examining their outputs in the medical domain to maintain ethical standards and objectivity [

6]. Specialists, experts, and trained researchers should use cautiously this very important tool.

In the context of advancing methodologies like AI and image generation in healthcare, it is imperative to uphold transparency in data documentation to ensure the reproducibility and reliability of research outcomes.

Adhering to established standards, such as those delineated in the recent STANDING-Together guidelines (accessible at

https://www.datadiversity.org/recommendations) [

9], is paramount for maintaining data integrity and fostering trust in scholarly endeavors. Understanding the varying levels of technological and healthcare infrastructure is crucial, as it heavily influences the capacity of distinct healthcare settings to effectively harness and derive benefits from innovative approaches like AI and image generation tools. By acknowledging and addressing these global disparities, we can enhance the adaptability and inclusivity of healthcare solutions on a global scale, thereby facilitating more equitable and impactful advancements in medical technology. [

10]

The advance of technology, expensive monitoring and tests has perhaps improved patient outcome overall but it has not ameliorated the bedside physical examination skills among medical students, residents and practising physician [

10,

11]

. One potential solution is the teaching of “visual literacy “trough the close observation and guided discussion of visual art and imaging [

4]

. Visual Thinking Strategy (VTS) [

4]

is a discussion-based teaching and learning methodology that uses art discussion in medical field to improve pattern recognition, communication, collaboration, empathy, critical and creative thinking. It has been used successfully also in critical care setting where observational skills and communication are of vital importance. The method of image analysis and discussion could be translated using a patient bed like an “art installation” stimulating observation and discussion. [

12,

13]

5. OpenAI vs. Human Generated Content

All biases in AI models can occur in the data on which the model is trained. OpenAI is aware of these potential challenges and has implemented measures to mitigate them in ChatGPT’s, DALL-E’s and other tools’ responses as demonstrated earlier in this manuscript in the practical examples. Preventing bias in chatbots, especially in sensitive areas like gender, involves multiple steps. Here are key strategies to reduce preconceptions:

- -

Use diverse training data: ensure that the training data includes a wide range of perspectives and voices. This includes balancing the representation of genders in medical case studies, research, and literature used in training the AI.

- -

Use algorithms and methods to detect and mitigate biases in the training data and the model’s outputs. This can involve both automatic methods, such as bias detection algorithms, and manual reviews by diverse human teams.

- -

Feedback and revalidation to train algorithms currently used: continuously update the AI model with new data, research findings, and balanced perspectives to reflect the most current and comprehensive understanding of gender issues in medicine. Re-evaluate the model periodically to assess bias and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

- -

Use strict ethical guidelines and standards that specifically address bias in AI. Embrace stringent ethical guidelines focusing on bias elimination to sustain the impartiality of AI tools in medical contexts.

- -

Foster a culture of transparent feedback mechanisms to refine AI models continually, because robust feedback mechanisms that allow users to report perceived biases or errors in the AI’s responses. Use this feedback to make improvements.

- -

Involve multidisciplinary teams, including ethicists, gender studies experts, medical professionals, and AI developers, in the design, training, and deployment processes of AI systems. This ensures a more holistic approach to recognizing and addressing potential biases.

- -

Provide training to educate users on the potential for bias and encourage them to use AI tools as one of many informational resources, not as the sole decision-maker, especially in critical fields like medicine.

Maintaining data security and public trust is paramount [

14,

15]. Building trust and acceptance among healthcare professionals is critical for the successful adoption and implementation of AI technologies in clinical practice.

Incorporating external validation methods and cultivating machine learning medical or scientific tools are essential steps to enhance the reliability and applicability of AI algorithms in medical settings. Collaborations with artistic professionals and scientific illustrators can enrich the AI database, enabling the development of more sophisticated and accurate image-generating tools that cater expressly to medical and scientific domains. International consensus amongst professionals and experts will further fortify the ethical and practical frameworks governing the use of AI in medicine, streamlining its integration into clinical practice [

16]. During centuries artists have helped doctors to understand anatomy and procedures. “Artists draw what can’t be seen, watch what’s never been done, and tell thousands about it without saying a word” (Association of Medical Illustrator 2024) [

4,

14].

Table 1.

Mitigating Black Box Biases requires the list presented in this table.

Table 1.

Mitigating Black Box Biases requires the list presented in this table.

| Data Auditing: |

Diverse and Representative Data |

Ensuring that Training Datasets Are Comprehensive and Representative of all Relevant Variables and Populations. |

| |

Bias Detection |

Implementing methods to detect and quantify biases in the training data. |

| Model Transparency |

Explainability Tools |

Using tools and techniques to make the model’s decision-making process more interpretable. |

| |

Open Practices |

Sharing model architectures, training methods, and datasets openly to allow for external scrutiny and validation. |

| Ethical AI Practices |

Bias Mitigation Techniques |

Employing techniques such as reweighting, adversarial debiasing, and fairness constraints during model training. |

| |

Continuous Monitoring |

Regularly assessing and updating models to address and correct biases. |

AI and ML tools are not used at the bedside, in teaching and in medical writing because there have many unresolved technicalities [

14]. These include access to comprehensive and high-quality datasets for training and validating AI algorithms. Issues such as privacy regulations, patient consent requirements, and data siloing within healthcare institutions limit the availability of figures for training and testing AI models [

2,

14]. Compliance with regulations such as GDPR and HIPAA imposes additional burdens on healthcare organizations, necessitating robust governance frameworks and risk management strategies. [

15,

16]. Collaborative efforts between regulatory authorities, industry stakeholders, and healthcare providers are essential to navigate these challenges and ensure the ethical [

11] and responsible use of AI in healthcare. [

17]

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the guidance provided ignites a crucial discussion on the ethical and systematic implementation of AI technologies, particularly in scientific writing and medical illustration.

By integrating external validation procedures and fostering the creation of bespoke AI tools for medical and scientific applications, stakeholders can bolster the efficacy and credibility of AI algorithms in clinical environments. International cooperation and consensus are essential for establishing standardized practices that adhere to ethical guidelines and promote responsible AI use in healthcare. The convergence of technology and medical expertise promises to transform patient care and advance medical knowledge. Training is required to use these tools, obstacles such as the creation of large, high-quality labeled datasets for model training continue to impede progress. In addition, ethical considerations [

17,

18,

19] regarding data use, safety, transparency, fairness [

8], and biases require addressing before integration into healthcare

systems [

19]

.

In this pursuit, let us not forget technology shapes our future, but it is our humanity that must always lead the way.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: article conception: FR, FT; draft manuscript preparation: FR, EB, FT, FB; preparation of figures: FR; preparation of tables: FT, EB, FB. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

all authors provide consent for this publication.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication. The Author has received no financial support including no institutional departmental funds. The Author has no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ChatGPT |

Chatbot Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| CCM |

Critical Care Medicine |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

References

- Salvagno, M., Taccone, F.S. & Gerli, A.G. (2023). Can artificial intelligence help for scientific writing? Crit Care 27, 75. [CrossRef]

- Klug J, Pietsch U. (2024) Can artificial intelligence help for scientific illustration? Details matter. Crit Care. Jun 10;28(1):196. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naghshineh S, Hafler. Miller AR, Blanco MA, Lipsitz SR, Katz JT. (2023) Formal Art Observation Training Improves Medical Students’ Visual Diagnostic Skills J Gen Intern Med 23(7):991–7.

- Yenewine P (2013) Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 1st edition (October 1, 2013) ISBN-10 : 1612506097. ISBN-13 978-1612506098.

- Katz JT, Khoshbin S. (2014) Can Visual Arts training Improve Physician Performance? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 125:331-342.

- Smith, A., Jones, B. (2021). The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: A Review of Current Trends and Future Directions. Journal of Medical AI, 5(2), 87-102. [CrossRef]

- Patel, C. , Lee, D. (2020). Leveraging AI Chatbots for Medical Education: A Scoping Review. Medical Education Journal, 18(4), 231-245. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E. , Nguyen, H. (2019). Ethics in Artificial Intelligence: Addressing Biases and Fairness in AI Models. Journal of AI Ethics, 3(1), 56-72. [CrossRef]

- Fong, N. , Langnas, E., Law, T., Reddy, M., Lipnick, M., & Pirracchio, R. Availability of information needed to evaluate algorithmic fairness—A systematic review of publicly accessible critical care databases. Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain Medicine, 2023; 42(5): 101248. [CrossRef]

- STANDING-Together 2024 see https://www.datadiversity.org/recommendations. (last open 6th September 2024).

- Rubulotta F, Bahrami S, Marshall DC, Komorowski M. (2024) Machine Learning Tools for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Detection and Prediction. Crit Care Med. Aug 12. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhruva, S. S. , Ross, J. S., Akar, J. G., Caldwell, B., Childers, K., Chow, W., Ciaccio, L., Coplan, P., Dong, J., Dykhoff, H. J., Johnston, S., Kellogg, T., Long, C., Noseworthy, P. A., Roberts, K., Saha, A., Yoo, A., & Shah, N. D. (2020) Aggregating multiple real-world data sources using a patient-centered health-data-sharing platform. NPJ Digital Medicine; 3: 60. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. , Adams, R. (2017). Exploring the Use of Chatbots in Medicine: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Health Information Technology, 23(2), 98-112. [CrossRef]

- Kalkman, S. , van Delden, J., Banerjee, A., Tyl, B., Mostert, M., & van Thiel, G. (2022) Patients’ and public views and attitudes towards the sharing of health data for research: A narrative review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Medical Ethics,; 48(1): 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Futoma, J. , Simons, M., Panch, T., Doshi-Velez, F., & Celi, L. A. (2020) The myth of generalisability in clinical research and machine learning in health care. The Lancet. Digital Health,;2(9): e489–e492. [CrossRef]

- Amann, J. , Blasimme, A., Vayena, E., Frey, D., Madai, V. I., & the Precise4Q consortium. (2020) Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: A multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making; 20(1): 310. [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, J. , Ivankovic, D., Habl, C., & Dimnjakovic, J. (20220 Enablers and barriers to the secondary use of health data in Europe: General data protection regulation perspective. Archives of Public Health = Archives Belges De Sante Publique; 80(1): 115. [CrossRef]

- Naik, N. , Hameed, B.M., Shetty, D.K., Swain, D., Shah, M., Paul, R., Aggarwal, K., Ibrahim, S., Patil, V., Smriti, K. and Shetty, S (2022). Legal and ethical consideration in artificial intelligence in healthcare: who takes responsibility? Frontiers in surgery; 9: 266.

- Wang, X. , Chen, Y. (2018). Machine Learning Algorithms for Clinical Decision Support in Critical Care: A Systematic Review. Critical Care Research Journal, 12(3), 134-147. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).