1. Introduction

Tourism is an economic generator that, with its multiple effects, contributes to the financial balance between the state and local governments. Given the growing importance of this industry as a contributor to public budgets in the form of taxes, the tax burden on tourism businesses deserves attention. In practically all countries, tourism budgets are under pressure because new resources are required to support tourism development. The taxation of tourism is an important tool for ensuring necessary investments in infrastructure, services, and promotional activities. The importance of tourism in the national economy can be expressed through the share of tourism in the state economy.

The direct gross domestic product of tourism is part of the gross domestic product of the economy. It is calculated as the sum of the direct gross added value of tourism and net taxes on tourism products (taxes on products minus subsidies on products included in the value of products consumed within the tourism industry).

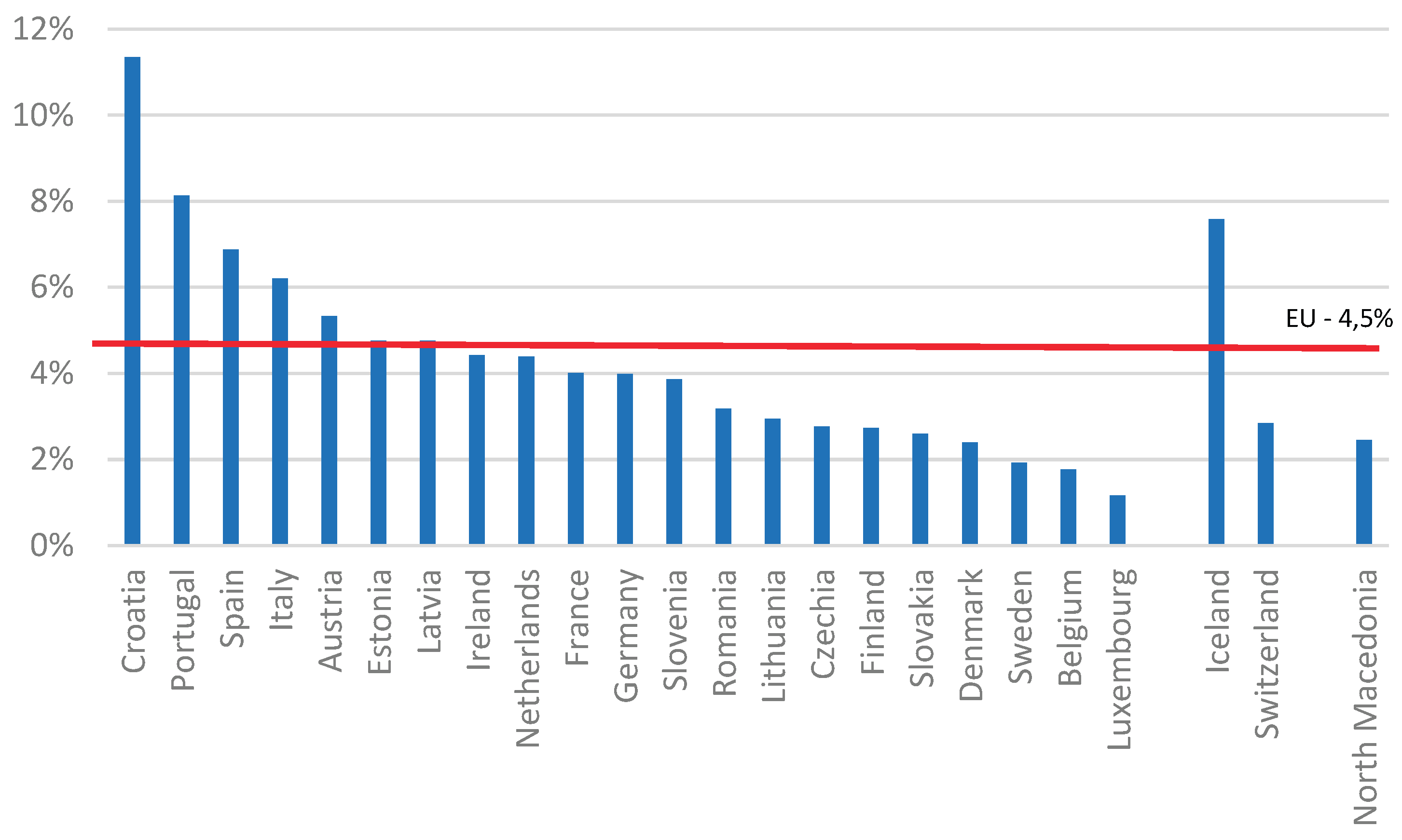

According to the latest edition of Tourism Satellite Accounts in Europe, the direct gross domestic product of the tourism industry in Europe reached EUR 572 billion in 2019 (the last year before the COVID-19 pandemic heavily hit the tourism sector), which represented a 4.5% share of the GDP of the European economy (

Figure 1).

The gross value added to the tourism industry includes the gross value added for all its activities, regardless of whether they are part of the tourism industry or whether they directly serve visitors.

The concept of accommodation tax is not recent; it has been long practiced in North American cities where revenue from such taxes has funded tourism projects for over two decades (Bonham & Mak, 1996). Before the 1960s, tourism-specific taxes were uncommon. However, with the remarkable growth of the tourism industry over the last half century, approximately 40 different taxes have been imposed on tourism activities. While the implementation of accommodation taxes has become increasingly widespread in many European cities, the scholarly discourse varies with respect to the overall impact of these taxes (Heffer-Flaata, Voltes-Dorta & Suau-Sanchez, 2021). Moreover, as tourist numbers surged, cities across Asia and Europe also adopted accommodation taxes, including Barcelona, which introduced the accommodation tax in 2012, and Kyoto in 2018 (European Tourism Association, 2018; Japan National Tourism Organization, 2019).

Destination Marketing Association International (2015), as well as Cárdenas-Garcí et al. (2022), demonstrated in their research that DMOs are primarily funded by public sources, such as accommodation taxes, before generating income from their own activities or from the private sector. Since the DMO plays the role of the leader of tourism development and the coordinator of relations and activities of stakeholders in the destination (Asmelash, Kumar & Villace, 2020; Idisondjaja, Wahyuni & Turino, 2023; Monroy-Rodríguez & Caro-Carretero, 2023), the DMO is also considered to be a financial manager of the destination (Cárdenas-Garcí et al., 2022). Taxation plays a pivotal role in the tourism industry, significantly affecting both government bodies and businesses. It is imperative for stakeholders to grasp and manage tax obligations within this sector. This requires achieving a delicate balance between revenue generation, sustainable development goals, and provision of high-quality services and visitor experiences (Safarov, Taniev & Janzakov, 2023).

Effective tax management within the tourism sector is paramount for several reasons. First, taxes contribute to economic growth by providing a stable source of revenue for governments, which can then be reinvested in tourism infrastructure and promotional activities (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2011). Second, it plays a crucial role in influencing the competitiveness of tourism destinations, with tax policies directly impacting destination appeal and visitor demands (Herman et al., 2019). Furthermore, taxation serves as a critical tool for governments to finance public services, infrastructure development, and tourism initiatives. Additionally, tax policies can serve as regulatory mechanisms that shape the behaviour of tourism businesses and visitors alike (Herman et al., 2023). For instance, accommodation taxes and tourist levies have been employed to manage issues such as overcrowding and environmental degradation in popular tourist destinations. Moreover, taxes can support environmental and cultural preservation efforts with revenue allocated to conservation initiatives and heritage protection programs (Yu et al., 2023).

Despite the potential benefits of taxation in the tourism sector, challenges and concerns persist. Stakeholders, particularly those within the accommodation sector, may resist taxes implementation, viewing it as burdensome or unfair (Nunkoo, 2015; Reinhold, Laesser & Beritelli, 2018; Ikeji & Yamada, 2020). Although earmarking taxes for tourism-related purposes enhances transparency and accountability, it may not secure support from accommodation providers (Reinhold, Laesser & Beritelli, 2018). For instance, Cantallops (2004) highlighted strong opposition to the accommodation tax in the Balearic Islands, where managers argued that its selective application unfairly targeted regulated accommodations while omitting unregulated ones, such as villas and apartments. Similarly, managers in destinations experiencing high volumes of day visitors may view the tax as unjust because they bear the burden of financing tourism initiatives.

In conclusion, understanding tax responsibilities and effective tax management practices is indispensable for the sustainable growth and success of the tourism industry. By striking a balance between revenue generation, development goals, and visitor satisfaction, taxation can contribute to the expansion and prosperity of tourism while ensuring a fair and equitable economic environment for all stakeholders involved. Therefore, the aim of our study is to bridge the gap between accommodation tax and destination management, providing insights from Central and Eastern Europe.

2. Literature Review

Researchers in the tourism field have extensively studied the effects of tourism taxation since the late 1970s. A growing body of literature has analyzed the economic impacts of indirect taxation on tourism activities, particularly focusing on its effects on the accommodation sector (Alfano et al., 2022). Previous research has presented theoretical justifications that support and oppose the implementation of an accommodation tax, yielding varied outcomes: some scholars have demonstrated that tourist demand remains largely unaffected by such taxation (Mak & Nishimura, 1979; Combs & Elledge, 1979; Bonham & Gangnes, 1996; Notaro et al., 2019; Soares et al., 2022; Göktaş & Çetin, 2023), whereas others have indicated that the tourism market responds to fluctuations in prices (taxes) (Aguilo et al., 2005; Durbarry, 2008; Lee, 2014; Arguea & Hawkins, 2015; Biagi et al., 2017; Heffer-Flaata et al., 2021; Biagi et al., 2021). Recent studies support the latter perspective (

Table 1).

Lee (2014) discovered that following the implementation of a hotel occupancy tax in 2007, midland hotels in Texas performed worse than neighboring Odessa lodging submarkets. Similarly, Arguea and Hawkins (2015) analyzed bed tax base elasticity across Florida counties from 1997 to 2012 and observed a substantial short-term decline in the hotel tax base due to an increase in the tax rate. Similarly, Biagi et al. (2017), who studied the impact of tourism tax on tourist flows in Sardinia, Italy, from 2006 to 2011, confirmed a decline in domestic tourist demand, but not international demand. In addition, the European Commission (2017) recommended reducing tourism taxes to enhance destination competitiveness and support tourism. This also mirrors the research of Heffer-Flaata et al. (2021), who found that hotel taxation negatively affected visitor flows, particularly during peak periods and in French destinations. This recommendation aligns with the findings of Biagi et al. (2021), who reported that tourists' insensitivity to price increases due to tourist taxes, suggesting that lower taxes could improve destination competitiveness.

Notaro et al. (2018) found that tourists in the Italian Alps were willing to pay tourist taxes to support local development. Similarly, Soares et al. (2022) reported positive public perceptions regarding the implementation of a tourist tax in Santiago de Compostela, highlighting a need for strategic tourism planning to address negative impacts. This finding underscores the importance of considering public perceptions and stakeholder engagement in the design and implementation of tourism taxation policies. In addition, Göktaş and Çetin (2023) also noted tourists' willingness to pay taxes to enhance sustainable tourism. These findings emphasize that tourists’ willingness to pay is determined by their use of funds for the sustainable development of a destination, as previously pointed out (Piriyapada &Way, 2015).

Sharma, Perdue, and Nicolau (2020) show that accommodation tax can have both positive and negative impacts on visitors. They analyzed the impact of lodging taxes on US hotels, focusing on two main market segments. Their study, based on data from 2013 to 2018, revealed that lodging taxes have a more negative effect on hotel performance (RevPar) for group bookings than for transient bookings.

In connection with the pandemic, accommodation tax, and tourism recovery, Chen et al. (2023) found that tax reductions and financial subsidies for local residents did not expedite post-pandemic tourism recovery, advocating for alternative policy measures. This suggests that traditional approaches to taxation and incentives may not always yield desired outcomes in the context of tourism recovery, highlighting the need for innovative and targeted policy interventions.

Sour, L., & Arcos, S. (2024) highlighted factors influencing the effectiveness of lodging tax collection. They analyzed data from 32 Mexican states. Their study, based on data from 2010 to 2020, revealed that states located on the coast and with significant tourist attractions tend to demonstrate higher lodging tax collection efficiency. They also identified key factors influencing lodging tax collection efficiency: regional tourist traffic, GDP, and employment rates in the tourism sector. This suggests that local governments should consider the specific economic conditions and industry dynamics in their regions to optimize lodging tax collection strategies.

Over the years, research on accommodation tax has focused on its use in sustainable development as a tool for the financial management of the destination (

Table 2).

Palmer and Riera (2003) proposed that levying an accommodation tax on tourism stays could effectively address negative externalities arising from tourism activities while concurrently supporting efforts towards resource preservation. Building upon this notion, Gooroochurn and Sinclair (2005) and Gago et al. (2009) suggest that implementing an accommodation tax could offer a viable solution to congestion issues in tourist destinations. However, the acceptance of such taxation measures among tourists varies across different demand segments. Do Valle et al. (2012) discovered that while typical sun-and-beach tourists, constituting a dominant segment of demand in many destinations, may exhibit reluctance to pay accommodation taxes, environmentally conscious and nature-oriented tourists display higher receptiveness to such taxation initiatives. On the other hand, Cetin et al. (2017) found that visitors are more willing to pay accommodation tax when it contributes to their experience directly. Additionally, research by Göktaş and Çetin (2023) indicates that tourists are willing to pay higher rates of accommodation tax if the tax is allocated to specific investments in sustainable tourism. Ortega-Rodríguez et al. (2024) discoverd that tourists' positive attitudes towards green policies, their ecological and pro-ecological attitudes, increase their willingness to pay accommodation taxes. The research results of Cetin et al. (2017), Göktaş and Çetin (2023), and Ortega-Rodríguez et al. (2024) highlight the importance of considering the diverse preferences and behaviours of individual tourist segments when designing effective tax policies. In turn, (Garcia et al., 2022) proved in their research that taxes play an important role in integrating the principles of sustainable development and enriching tourists' experiences.

Moreover, the impact of tourism taxes extends beyond economic considerations to encompass broader implications for social welfare. Sheng and Tsui (2009) highlight the role of destination market power in shaping the effects of tourism taxes on social welfare, emphasizing the need to evaluate taxation measures within a broader social and environmental context to maximize their welfare-enhancing potential. In addition to its social and economic dimensions, tourism taxation has also been explored in the context of natural disaster management and sustainability. Ponjan and Thirawat (2016) demonstrated that tax cuts in the aftermath of natural disasters could mitigate the adverse effects on tourism, while Durán-Román et al. (2021) emphasized the positive role of tax reductions in enhancing the sustainability of tourism destinations.

These studies contribute to the literature by highlighting the potential drawbacks and benefits of taxation in the tourism industry. Specifically, it adds to the evidence suggesting that, while accommodation taxes may provide revenue for municipalities, they can also have adverse effects on the performance of accommodation facilities. This underscores the complexity of balancing the advantages of taxation with its potential negative consequences, emphasizing the importance of carefully considering the implications of such policies for all tourism ecosystem stakeholders.

3. Materials and Methods

Accommodation taxes are widespread in tourism, typically charged per person or per night. These constitute a small part of the total accommodation cost and are commonly applied across Europe (Alfano et al., 2022). As an examination conducted by Heffer-Flaata, Voltes-Dorta & Suau-Sanchez (2021) revealed, approximately 75 % of the 20 most frequented European cities implemented some form of tourism tax. In EU member states, revenue from tourist taxes allocated to local administrations can be collected through three distinct methods: per person per night basis, per room per night, or as a percentage of the room rate (Goktas & Polat, 2019). Accommodation tax is applied in 18 EU countries, is not collected in a third of the EU countries. The rate ranges from 0,10 EUR Bulgaria 7,50 EUR. On average, the rate is lower in Eastern European countries, where there is also a lower accommodation price. The average rate ranges from 0,40 EUR to 2,50 EUR. The rates are mostly differentiated according to accommodation type.

As the tourism sector in Slovakia is becoming an increasingly important part of the national economy and accommodation tax is considered one of the financial management tools of the destination, in our research, we focus on clarifying the determination and collection of the tax in different parts of Slovakia, how the accommodation tax affects the public budget, and how proper financial management of the destination can contribute to the development of the municipality..

3.1. Municipal Accommodation Tax Data (2017-2023)

Nature of the Data. This dataset includes detailed statistics on accommodation tax revenues from all municipalities in Slovakia that applied this tax. The data spans from 2017 to 2023, capturing fluctuations in tax revenue and its impact on local public budgets.

Geographical Range. The dataset covers municipalities across Slovakia, including key tourism destinations like Bratislava, High Tatras, Piešťany, Dudince, and Demänovská Dolina, among others.

Source of the Data. The data was obtained from municipal records, focusing on the revenue collected through accommodation taxes across various municipalities. This information is critical for assessing both regional and national-level trends in tax revenues.

Size of the Data. The dataset includes tax records from 905 municipalities (as of 2023), tracking the growth in the number of municipalities applying the tax from 878 in 2022.

Data Accessibility. The data is available through municipal reports and government statistics, accessible to the public. In some cases, individual municipalities may require formal requests to access their specific financial data.

Rights and Permissions. Since this data is part of the public financial records of municipalities, no special permissions were required for its use. It complies with Slovakia’s regulations on the use of public financial data for research purposes.

3.2. Ministry of Transport and Municipal Data (2012-2022)

Nature of the Data. Statistical data on the composition of Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) incomes at regional and local levels, focusing on the distribution of subsidies and other financial sources.

Geographical Range. This data includes financial details from DMOs operating in all regions of Slovakia, providing a nationwide view of DMO funding and activities.

Source of the Data. Data was collected from the Ministry of Transport of the Slovak Republic, the central register of contracts, and the central register of financial statements. It was further supplemented by annual reports from DMOs across Slovakia.

Size of the Data. The dataset spans 10 years (2012-2022), covering financial records from all DMOs at both regional and local levels. Over 59 million EUR in subsidies were tracked and analyzed across this period.

Data Accessibility. Data from the Ministry and central registers is publicly accessible.

Rights and Permissions. Data from government ministries and registers does not require special permissions for research purposes.

3.3. Annual Reports of DMOs and Contracts with the Ministry of Transport

Nature of the Data. This data includes detailed financial reports from DMOs, focusing on how subsidies and other income sources are distributed and utilized for tourism development and sustainability projects.

Source of the Data. The data was obtained from publicly available annual reports of DMOs and contracts between DMOs and the Ministry of Transport, available through the Central Register of Contracts.

Size of the Data. The dataset includes reports from all DMOs that published annual reports, with specific attention to the subsidies provided for the creation and support of sustainable tourism products.

Data Accessibility. The reports are available through public records.

Rights and Permissions. Since the reports are part of public records, no special permissions were required for their use, provided they were obtained through publicly accessible means.

3.4. Ethical Considerations and Permissions

The data used in this research does not contain any personal or sensitive information, focusing solely on public financial records, statistical data, and tourism-related metrics. Thus, no ethical approvals or individual permissions were required. All data was handled in accordance with Slovakia’s legal regulations regarding the use of public financial data.

3.5. Data Analysis

First, we collected statistical data on accommodation tax for all municipalities that applied the tax, and analyzed the differences between the most visited destinations. We focus on identifying fluctuations in the volume of taxes collected and how these fluctuations can affect public budgets. Second, we collected and analyzed statistical data from the Ministry of Transport of the Slovak Republic and data from the central register of contracts and the central register of financial statements to identify the composition of incomes of DMOs at the regional and local levels in Slovakia. We further used these data to identify the distribution of subsidies between the individual regions of Slovakia. As the financial management of the destination can contribute to sustainable tourism development, we investigated the impact of DMOs on sustainable development using Spearman's correlation coefficient.

The coefficient examines the strength of the dependence of two variables: the dependence between the total subsidies provided and the subsidies spent on the creation and support of sustainable products. We identified the amount of subsidies spent by analyzing the activities of DMOs at the local and regional levels based on the annual reports of all DMOs in Slovakia that publish annual reports and by analyzing contracts between the DMO and the Ministry of Transport of the Slovak Republic, which are published in the Central Register of Contracts.

The results of the correlation coefficient can be interpreted in three groups, with the minus sign indicating indirect dependence and the plus sign indicating direct dependence between the investigated variables.

Strong dependence: if the value of the coefficient lies between ± 0,50 ± 1;

s medium dependence: if the value lies between ± 0,30 a ± 0,49;

weak dependency: if the value is less than ± 0,29.

Since destination benchmarking can be used to evaluate and improve a destination's performance by comparing it with best practices and standards from other destinations (Xiang et al., 2007; Luštický & Kinčl, 2012; Assaf & Dwyer, 2013; Strydom, 2018; Madsen & Johanson, 2022), we used Switzerland as a benchmark for destination management in Slovakia and bring this comparison in discussion. Switzerland has long been one of the pioneers in the tourism industry, and its destination management has a long tradition (Steffen et al., 2020; Cardoso et al., 2021; Leimgruber, 2021). Moreover, the primary tourism offer, as well as the historical development of the country, is similar to Slovakia, and we believe that this comparison is appropriate and will be helpful. This process helps identify strengths and weaknesses, set performance goals, and develop strategies for improvement. By understanding where a destination stands in relation to others, stakeholders can make informed decisions to enhance the visitor experience, boost competitiveness, and achieve sustainable growth.

4. Results

In Slovakia, accommodation tax has a predecessor in spa and recreation fees. The spa tax (Kurtax) was introduced in–Australia Hungary. However, it has purposeful use in tourism in most countries. This is still the case in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (Hornok, 2021A). The basic definition of tax is given in the Act of the National Council of the Slovak Republic no. 582/2004. The law provides a broad definition of tax, leaving its implementation to local governments, who establish detailed regulations. The tax applies to temporary stays in facilities that offer accommodation services, with taxpayers being temporary residents. It is calculated based on the number of overnight stays, with a rate per person per night determined by the municipalities in euros. Each municipality has autonomy in setting rates without specifying minimum or maximum values. Additionally, municipalities may opt for a flat annual tax, exempting operators from guest-record-keeping obligations (Hornok, 2022).

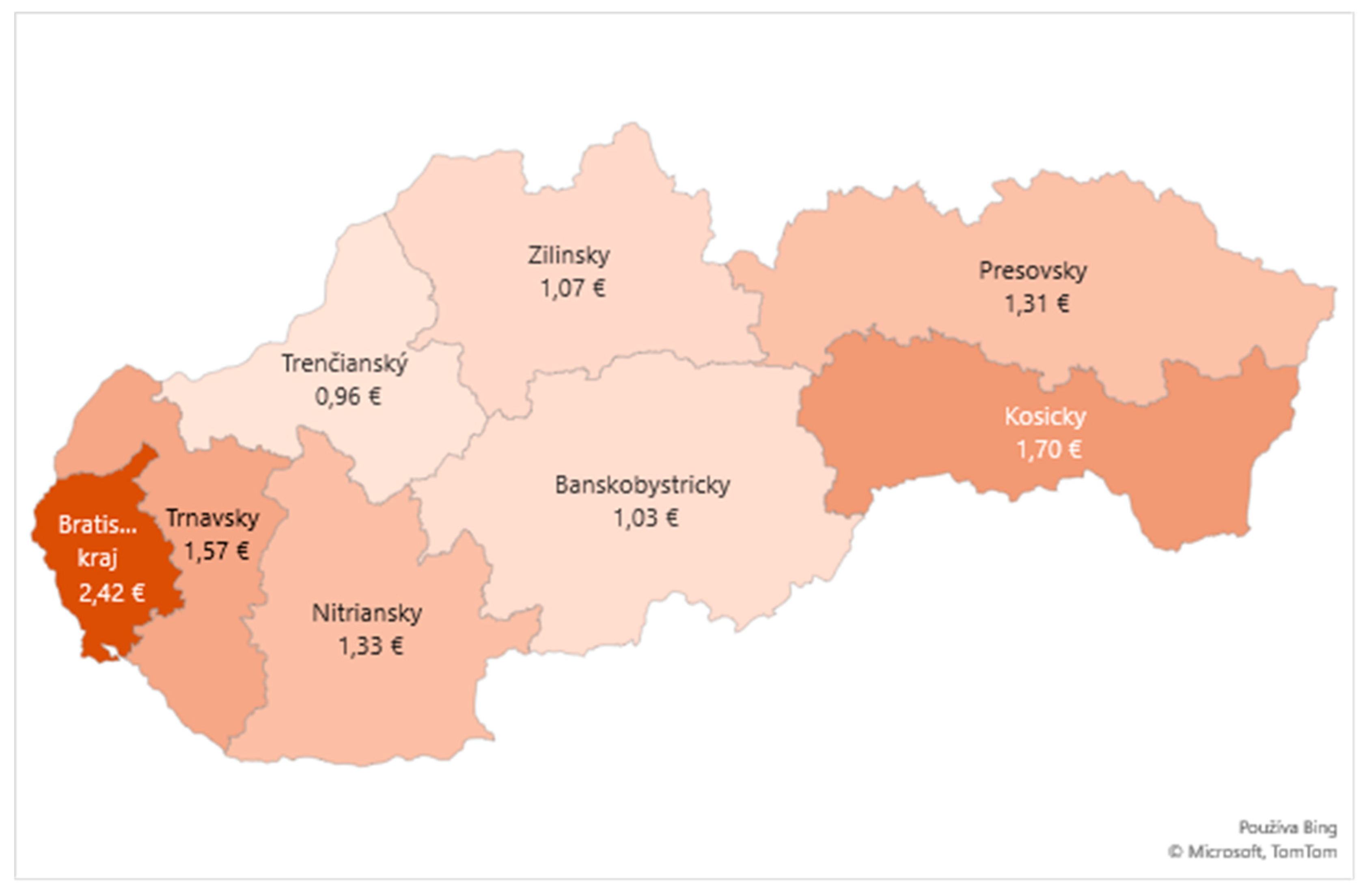

Determining the accommodation tax rate is the responsibility of the municipal government; therefore, there are fundamental differences in its amount (Hornok, 2019). The average tax rate for accommodation in individual regions, calculated as a share of tax revenue for accommodation and the number of overnight stays, was the highest in the capital city of Bratislava 2,42 EUR (1,93 EUR in 2022) and the lowest in the Trenčín Region, where it did not exceed 1,00 EUR (

Figure 2).

The increase in the average price for accommodation since 2017 was 42 % and the increase in the average tax rate was 47 % (

Table 3). The share of accommodation tax on the average accommodation price increased slightly.

The monthly collection of tax results in fluctuations in the income of local municipal budgets, depending on the development of visitors at the destination. The seasonality of accommodation tax income is demonstrated by the development of income in 2023 and 2022 (

Table 4). While the distribution of income for the whole of Slovakia has not changed year-on-year, a significant fluctuation is visible in Demänovská Dolina, which is an important tourism center. Even though the rate in this municipality changed from 1,00 EUR 2022 to 1,50 EUR in 2023, rate changes always occurred on January 1. and, therefore, did not affect seasonal fluctuations. The opposite was observed in Bratislava, the capital city, where the rate change occurred during the year 2023 and had an impact on the yield in the second half of the year.

Cities and municipalities with the highest share of accommodation tax revenue per inhabitant, such as Demänovská dolina, have, thanks to tourism, the same budget as villages with eight times the number of inhabitants. In addition to the income of municipal budgets, the tax procedure for accommodation tax is a valuable source of information about visitors (Gúčik, Hornok, 2021).

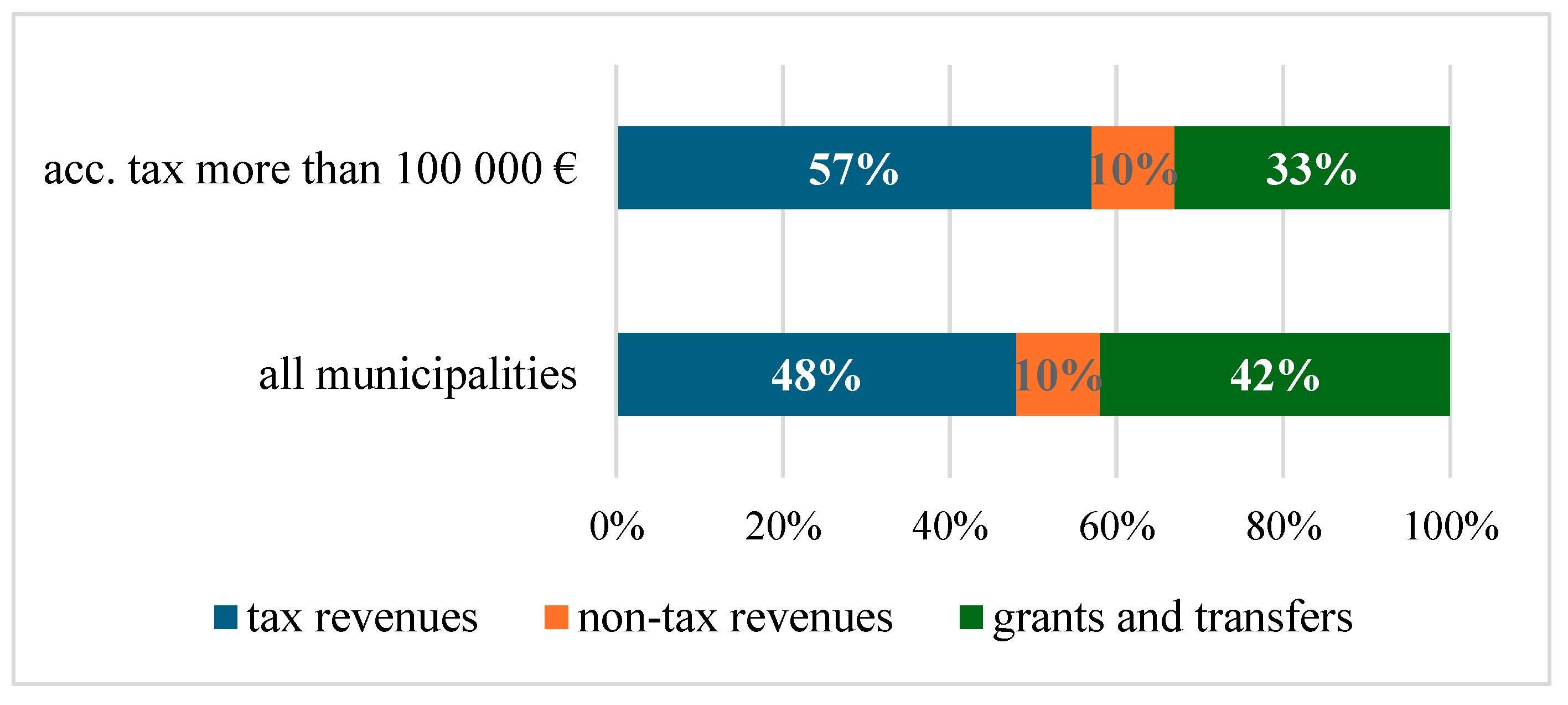

Almost half of the revenues of the current municipalities’ budgets are tax revenues, 48 % due to the share of income tax from individuals. Non-tax income of the regular budget of the municipality are creating 10 % - income from business and property ownership, from administrative fees and other fees and payments, income from interest from domestic and foreign loans, repayable financial assistance, deposits and premiums, and other non-tax income. 42 % of the revenues are grants and transfers from the state budget - ordinary grants and transfers, and capital grants and transfers intended for financing the competences of the transferred performance of the state administration. Most funds were directed to the field of education, the rest to public services (registry, population register), and the economic field to construction and road transport. Other activities provided by municipalities within their self-governing powers include supporting regional development, tourism, housing development, and infrastructure renewal. This amount also includes funds provided by individual chapters for financing joint projects within the EU. In municipalities where the revenue from accommodation tax is more than 100 000 EUR, the share of tax revenue is 9 % higher. This increase occurred at the expense of transfer payments, the share fell to 33 % (

Figure 3).

Accommodation tax was levied in 878 municipalities in 2022, and a year later it was already 905. This represents the highest number since 2012, when accommodation tax was levied on only 720 municipalities. The share of the accommodation tax in the total tax revenue of cities and municipalities where the accommodation tax was collected varied from 0,78 % in 2021 to 1,13 % in 2023. Apart from the COVID period, the share of the accommodation tax in the total tax revenue of the municipality is at the level of one percent even though the tax revenue increased by more than 240 %. In 2023, there were seven municipalities in Slovakia with a share of accommodation tax in total taxes higher than 20 %. The share higher than 10 % is in another 18 and more than 5 % is in another 22 municipalities. An indirect benefit of the presence of tourism is the increased income from taxes imposed on buildings and accommodation facilities.

The new significant benefit of the accommodation tax is defined in the Tourism Support Act. The state subsidy ceiling for DMO at a local level is set at 90 % of the aggregate amount of accommodation tax collected in member municipalities associated with the DMO for the year preceding the previous budget year. At DMO At the DMO, it is 10 %. The subsidy can be used by the DMO for marketing and promotion, activity of the tourist information center, creation and operation of the reservation system, sustainable tourism products, tourism infrastructure, strategic documents, statistics and surveys, service quality systems, and education (Hornok, 2021, B).

For a DMO to achieve correct financial management of a destination, it is necessary that the activities performed by the DMO are effective. The activities of DMOs in Slovakia at regional and local levels are defined in the Tourism Support Act. The activities of DMOs in Slovakia at local and regional levels are financed by member contributions, subsidies, and their own activities (

Table 5). The total amount of subsidies provided in the years 2012-2022 was 59 362 603,20 EUR.

Income from own activities makes up approximately only 4 % of the income of DMOs in Slovakia. From a long-term perspective, the current structure of income composition of DMOs is unsustainable and ineffective. The subsidy provision scheme changes regularly, and there may be a situation where subsidies stop being provided completely. The amount of membership fees, which make up approximately 56 % of the budget of management organizations, can also change. Due to the impact of the pandemic, many members of DMOs do not have enough financial resources to pay the membership fee. The DMOs thus lose significant sources of funding, as the amount of the subsidy also depends on the membership fees.

Over the past nine years, subsidies have increased by more than 5,1 million EUR. However, it still does not reach the maximum possible level, which is accommodation tax revenue. By amending the law, the maximum subsidy amount was fixed at the level of 2019 when the tax revenue reached 16 million EUR.

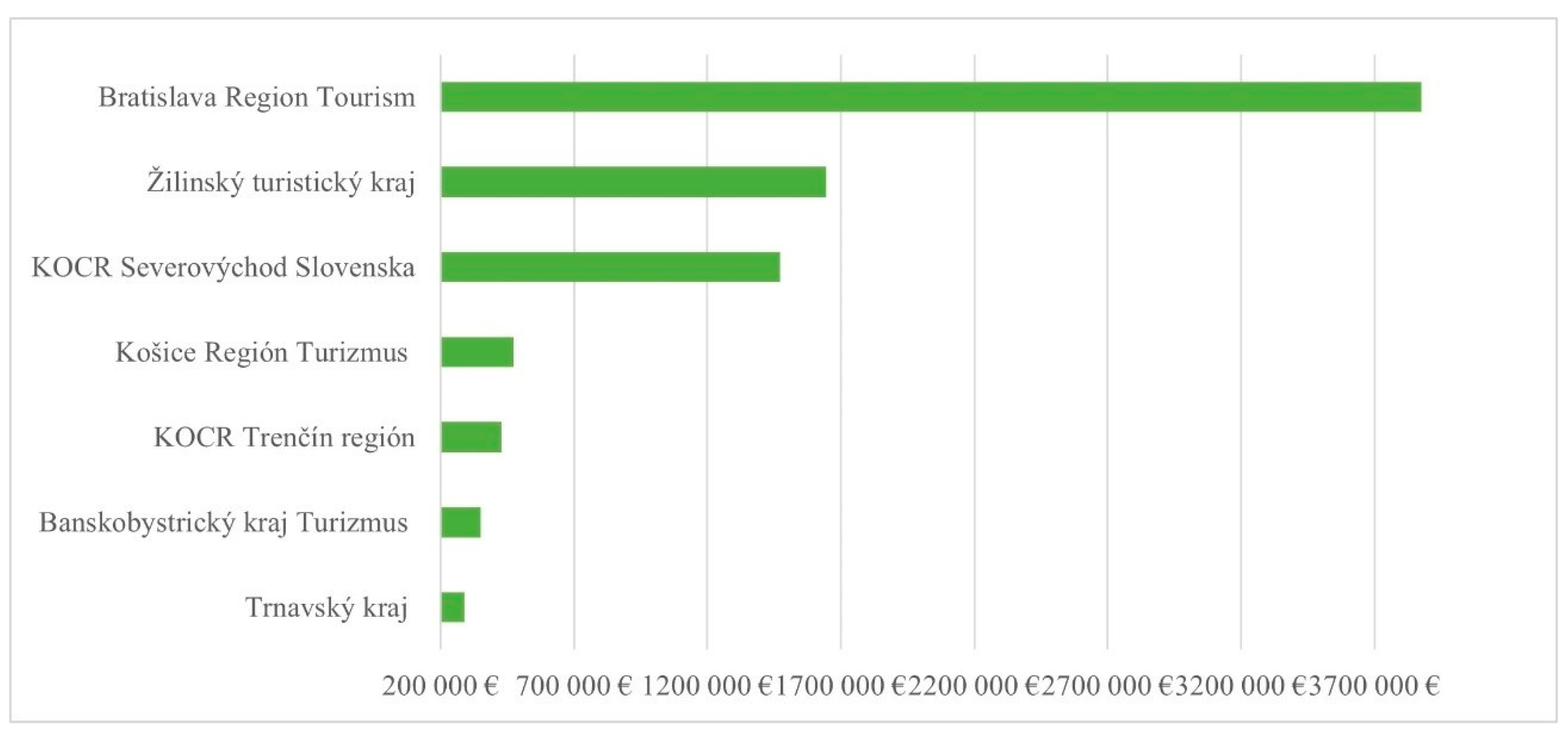

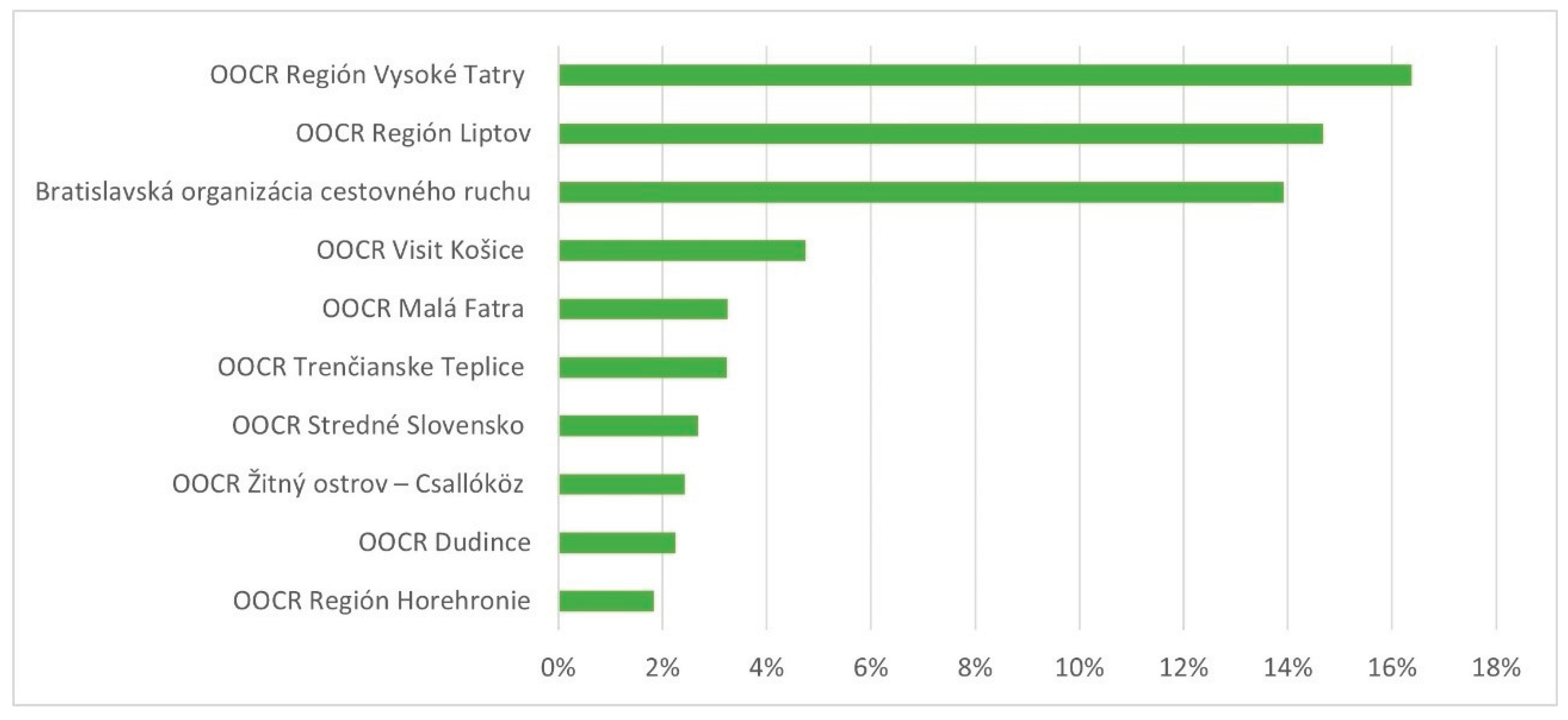

The structure of the subsidies provided is relatively uneven in Slovakia (

Figure 4). The Ministry can provide a subsidy to a regional organization in the same amount as the membership contribution of a higher territorial unit, while the maximum amount of subsidy to a regional organization is limited to 10 % of the accommodation tax of all member municipalities of regional organizations.

The Ministry can provide a subsidy to a DMO at a local level in the same amount as the aggregate value of the selected member contributions of the regional organization, while the maximum amount of the subsidy to the regional organization is limited to 90 % of the aggregate value of the collected accommodation tax for all member municipalities. The current method of providing subsidies deepens regional disparities, as regions with strongly developed tourism are entitled to a higher subsidy, whereas regions with less developed tourism are entitled to a lower subsidy (

Figure 5).

The adoption of Act Tourism Support Act No. 91/2010 stimulated the creation of management organizations at the regional and local levels. By amending the Act dated January 1, 2020, the activity "creation and support of tourism products" was changed to "creation and support of sustainable tourism products". To determine the extent to which this amendment influenced the development of sustainable tourism, we checked the Spearman correlation coefficient.

The results of Spearman's correlation coefficient showed a moderately strong direct relationship between the amendment of Tourism Support Act No. 91/2010 and sustainable tourism development (

Table 6). to 2020-2022, an average of 21 % of the total volume of subsidies was provided for the creation and support of sustainable products, and 66 % of these subsidies were actually used for the creation and support of sustainable products. We considered sustainable products to be those that were designed, developed, and provided in a way that minimized negative impacts on the natural, social, and economic environment, while maximizing the benefits for all stakeholders. The goal is to provide visitors with unique experiences while contributing to sustainable tourism development. For the subsidies provided to support truly for sustainable products, closer cooperation between the Ministry of Transport of the Slovak Republic and Slovakia Travel, the national DMO, and the DMOs at regional and local levels is necessary. Cooperation enhances DMOs’ knowledge of sustainable and ensures retrospective control of the expenditure of public funds.

5. Discussion

By taxing tourism, the tax is exported outside the region since visitors, not residents, pay it.. Voters of regional politicians are not taxed in this way, making tourism taxes politically more transitory. However, in tourist attractions where tourism generates significant income, businesses can influence tax decisions. Tourism businesses, as key regional employers, impact tax policies. Several local taxes affect the tourism sector, which inevitably influences pricing and overall demand.

Visitors mostly have average and above-average incomes, making it easier for them to bear an additional tax burden. Money is spent more freely on vacation; therefore, taxation faces less resistance than in ordinary life. Visitors consume public goods and must contribute to their funding, including security and public services, and infrastrcuture. Increased visitor arrivals raise the need for financing the aforementioned good, and without taxation of tourism, the burden would remain on residents. From this point of view, tourism taxation is fair. While some attractions charge visitors directly, taxation remains the simples and fairest financing method in most cases.

Higher tax revenues, also thanks to tax revenues from tourism, can help to increase well-being in the country, for example, by higher expenditures on health care or by reducing the tax burden on residents. Such tax revenues can also help change the tax policy, for example, by reducing consumption taxes. In traditional tourist countries, revenues from taxes imposed on tourism constitute from 10 % to 25 % of total tax revenues. In the Bahamas, this share is up to 50 %, in the Maldives around 40 %. Developing countries do not fully utilize their tourism tax potential. This is mainly related to the level of services provided, which is at a very low level and thus produces a very low added value. Thus, there is no room for higher tax revenue. Developing countries compensate for lower quality services with a more attractive primary offer. In general, the more attractive the primary supply, the less elastic the demand, and the less responsive it is to price increases caused by the introduction or increase in taxes. Therefore, countries with a rich primary supply have more room to raise taxes. For example, the introduction of lodging tax in Hawaii had no effect on hotel revenues; it did not affect the length of stay. However, when examining the tax burden, we must consider the complexity of the tourism product and take into account the fact that each component may be taxed with a different tax, a set of taxes, or at a different rate. In addition, the taxation of one component, even if it does not directly affect its consumption, can cause consumption of another component that may not be taxed. Increasing the costs of the tourism product caused by taxation can also cause a decrease in savings or a decrease in the visitor's normal consumption.

Many developing countries forget about the negative effects on the environment thanks to the currencies brought about by tourism. Sooner or later, they will have to address this problem. There are two ways to regulate the influx of visitors and, thus, the devastation of the environment. The government has decided to regulate tourism through regulatory guidelines or by taxing selected products. The first solution can cause significant disruption in the economic environment, which disrupts the entire economy. In the second case, the intervention is not directive, and the economy absorbs it more easily. Nor does the pressure on the growth of corruption, which arises precisely where there are direct interventions by the state in the economy, and the additional tax revenue also represents resources for the restoration or development of the affected area. This is the way for the sustainable development of tourism. One such tax can be an entry tax (entrance fee). When introducing it, due to the regulation of mass tourism, we must also consider the negatives it brings. This tax limits the number of visitors and does not only limit a certain activity. Thus, we give up all income from visitors, whom we discourage with the entrance fee. If the entrance fee is a one-time fixed amount, it discourages short-term stays more than long-term stays, which are less affected. The entrance fee is usually paid only by visitors and not by residents, who participate equally in the devastation of the environment because of their presence.

Security fees are collected, for example, at airports in New Zealand and financed by state organizations, ensuring the safety of air transport. Consumption support in the form of VAT refunds paid when purchasing goods by visitors aims to support their consumption in Israel, and job creation is stimulated in Ireland in the form of a reduced VAT rate. For example, in Mexico, 80 % of the revenue from the special tax imposed on incoming visitors is directed to the Mexican Tourism Organization, which handles domestic and international tourism promotions. However, a diverse approach in applying different fees and incentives to meet short-term goals has a long-term impact on tourism. It is necessary to examine tourism as an industry and taxation of this period comprehensively and in the long term, considering strategic development goals.

In Switzerland, the activities of DMOs are financed in different ways, and the financing of organizations depends on their legal form. Management organizations at the regional and local levels in Switzerland mostly take the form of joint-stock companies or associations; some organizations exist in the form of cooperatives or other forms. Organizations are financed mainly by accommodation tax, contributions from public sources, their own activities, and member contributions (

Table 7).

The main difference in the composition of the income of DMOs at the regional and local levels in Slovakia and Switzerland is in the share of member contributions. While In Switzerland, this income is only approximately 10 %, in Slovakia, this income is 56 %. Another significant difference is income from own activities, which accounts for approximately 23 % in Switzerland, while in Slovakia it is only 4 %. Income from DMOs’ own activities in Switzerland is made up mainly of commissions, royalties, sales of products, and provision of services to third parties. Commissions are earned by third-party service providers who offer their products and services through the organization. Often, these are commissions from accommodation facilities, travel agencies, and other service providers. Royalties and licenses refer to royalties that an organization can receive for the use of its brand or intellectual property by third parties. Services provided by organizations to third parties most commonly include marketing activities, event planning, or consulting services.

Another significant difference in the income structure of DMOs in Switzerland is the accommodation tax income, as in Slovakia the accommodation tax is income to the budget of the local government and affects the budget of the organization only in connection with determining the maximum amount of the provided subsidy. The difference in the income of DMOs is also observed in contributions from public sources, which DMOs in Slovakia do not have in the composition of income. Approximately 6 % of these revenues in Switzerland are resources to cover costs that are not tied to specific performance goals of the organizations but are intended to support their activities. These costs are primarily operating and labor costs, which must be paid from their own resources in Slovakia.

In conclusion, taxing tourism presents a viable strategy for generating revenue without directly burdening residents, thus making it politically favorable. In tourism-dependent regions, tourism businesses have a significant influence on tax decisions. The revenue generated from tourism taxes supports public goods and services, reducing the financial burden on residents and contributing to the overall national welfare. Countries with robust tourism industries, such as the Bahamas and Maldives, capitalize significantly on tourism taxes, while developing nations often underutilize this potential due to lower service quality.

Poland is an example of a country that does not use the potential of tourist taxes, including those on accommodation, despite the relatively high quality of services offered (Grobelna, Marciszewska, 2013). Debates on introducing an accommodation tax have been conducted in Poland for years but with little success. The local fee in Poland is collected from individuals staying longer than 24 hours for tourist, recreational or training purposes in locations with favourable climatic properties, landscape values and conditions enabling the stay of people for the purposes mentioned above, as well as in locations located in areas that have been granted the status of a protected health resort area (Dz. U. z 2007 r., Nr 249, poz. 1851). Therefore, not every location attractive to tourists can collect a local fee.

Although the history of DMOs in Poland is longer than in Slovakia, their income structure is similar. However, it should be noted that the central part of the income is subsidies, which only in the case of Regional DMOs amount to 70% (FROT 2024).

Income from membership fees constitutes about 10% of DMO income in Poland. On the other hand, income from own activities averages about 20%. As in the case of Slovakia, it should be noted that the composition of DMO income in Poland is unbalanced and inefficient.

Moreover, tourism taxation can be a tool for sustainable development, helping fund environmental conservation and infrastructure improvements. While direct regulatory measures can disrupt economic stability, taxation provides a smoother and less intrusive method of managing the environmental impact of tourism. Different types of tourism taxes, such as entry fees and security charges, have varied effects on visitor behaviour and economic outcomes. Effective tourism taxation requires a comprehensive, long-term approach that aligns with strategic development goals and balances immediate fiscal needs with sustainable industry growth. The recent global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that aid policies in many regions of the world have proven to be ineffective (Shao et al., 2020; Wszendybył -Skulska et al., 2024) and revenues from the tourism tax directly at the disposal of DMOs could be an excellent source of support for tourism in the regions.

A comparison between Switzerland and Slovakia highlights different funding structures for DMOs, emphasizing the role of accommodation taxes and public contributions in supporting these entities. Swiss DMOs benefit from diverse income sources, including member contributions, own activities, and public funds, whereas Slovak DMOs rely heavily on member contributions and have limited revenue from their activities. This analysis underscores the importance of a balanced and diversified funding strategy for DMOs to ensure sustainable tourism development and effective destination management.

5. Conclusions

Higher tax revenues, including those from tourism, can enhance a country's well-being by increasing healthcare spending or reducing domestic tax burden. Traditional tourist destinations often rely heavily on tourism taxes, comprising 10 % to 50 % of total tax revenue. However, developing countries may not fully exploit their tourism tax potential because of low service quality and added value. Countries with attractive primary offers have more flexibility in raising taxes without significantly affecting demand. Taxation of tourism products can be complex, affecting overall consumption and visitor behaviour; thus, accommodation tax can also contribute to sustainable tourism development and building industry resilience.

By taxing tourism, the burden is placed on temporary visitors rather than on the domestic population, leading to political transience in regions where voters of regional politicians are not affected. However, in tourist destinations, where tourism income is significant, businesses have a considerable influence on tax decisions as major employers. The numerous local taxes imposed on tourism businesses inevitably affect the prices and overall demand. Visitors typically belong to income groups with average or above-average incomes, making them more capable of bearing additional tax burdens, especially because spending tends to be more liberal during vacations, resulting in less resistance to taxation. Therefore, we believe that accommodation tax can contribute to sustainable tourism development, and in the most visited destinations, it can even act as a mediator of the negative effects of tourism development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Maráková Vanda; methodology, Maráková Vanda; validation, Maráková Vanda; formal analysis, Maráková Vanda; investigation, Maráková Vanda; resources, Maráková Vanda and Wszendybył-Skulska Ewa; data curation, Dzúriková Lenka; writing—original draft preparation, Maráková Vanda and Wszendybył-Skulska Ewa; writing—review and editing, Maráková Vanda and Wszendybył-Skulska Ewa; visualization, Wszendybył-Skulska Ewa; supervision, Maráková Vanda; project administration, Maráková Vanda; funding acquisition, Maráková Vanda.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic VEGA under Grant number 1/0360/23 “Tourism of the New generation – responsible and competitive development of tourism destinations in Slovakia in the post-COVID era.”.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are included in the article and/or supporting material. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Michal Hornok: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| DMO |

Destination Management Organization |

| RevPar |

Revenue Per Available Room |

| EU |

European Union |

| EUR |

Euro |

| Acc |

Accommodation |

References

- (Aguiló et al., 2025) Aguiló, E., Riera, A., & Rosselló, J. The short-term price effect of a tourist tax through a dynamic demand model: The case of the Balearic Islands. Tourism Management 2005, 26, 359–365.

- (Alfano et al., 2022) Alfano, V., De Simone, E., D’Uva, M., Gaeta, G. L. Exploring motivations behind the introduction of tourist accommodation taxes: The case of the Marche region in Italy. Land Use Policy 2022, 113. [CrossRef]

- (Arguea & Hawkins, 2015). Arguea, N. M.,Hawkins, R. R. The rate elasticity of Florida tourist development (aka bed) taxes. Appl. Econ. 2015, 47, 1823–1832. [CrossRef]

- (Asmelash et al., 2020) Asmelash, A. G., Kumar, S.,Villace, T. Tourist satisfaction-loyalty Nexus in Tigrai, Ethiopia: Implication for sustainable tourism development. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- (Assaf & Dwyer, 2013). Assaf, A. G., Dwyer, L. Benchmarking International Tourism Destinations. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1233–1247. [CrossRef]

- (Biagi et al., 2026) Biagi, B., Brandano, M. G., Pulina, M. The effect of tourism taxation: A synthetic control approach (Working Paper CRENoS 201609). Centre for North South Economic Research, University of Cagliari and Sassari, Sardinia.

- (Biagi et al., 2021) Biagi, B., Brandano, M. G., Pulina, M. Tourism taxation: Good or bad for cities? In M. Ferrante, O. Fritz, & Ö. Öner (Eds.), Regional Science Perspectives on Tourism and Hospitality. Advances in Spatial Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. p. 477-505.

- (Bonham & Gangnes, 1996) Bonham, C. S., Gangnes, B. Intervention analysis with cointegrated time series: the case of the Hawaii hotel room tax. Appl. Econ. 1996, 28, 1281–1293. [CrossRef]

- (Bonham & Mak, 1996) Bonham, C., Mak, J. Private versus Public Financing of State Destination Promotion. J. Travel Res. 1996, 35, 3–10. [CrossRef]

- (Cantallops, 2004) Cantallops, A. S. Policies Supporting Sustainable Tourism Development in the Balearic Islands: The Ecotax. Anatolia 2004, 15, 39–56. [CrossRef]

- (Cárdenas-García et al, 2024) Cárdenas-García, P.J., Brida, J. G., Segarra, V. Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: evidence from homogeneous panels of countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-García, P.J.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Durán-Román, J.L.; Carrillo-Hidalgo, I. Tourist taxation as a sustainability financing mechanism for mass tourism destinations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Cardoso et al., 2021) Cardoso, L. A., Araújo, A. F., Santos, L. L., Schegg, R., Breda, Z., Costa, C. Country Performance Analysis of Swiss Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2378. [CrossRef]

- Central register of contracts. (2023). Available online: https://www.crz.gov.sk/ (accessed on 25.01.2025).

- Central register of financial statements. (2023). Available online: https://www.registeruz.sk/cruz-public/domain/accountingentity/simplesearch (accessed on 25.01.2025).

- (Cetin, 2017) Cetin, G., Alrawadieh, Z., Dincer, M. Z., Istanbullu Dincer, F., Ioannides, D. Willingness to Pay for Tourist Tax in Destinations: Empirical Evidence from Istanbul. Economies 2017, 5, 21. [CrossRef]

- (Chen et al., 2023) Chen, J. J., Qiu, R. T. R., Jiao, X., Song, H., Li, Y. Tax deduction or financial subsidy during crisis?: Effectiveness of fiscal policies as pandemic mitigation and recovery measures. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2023, 4.

- (Combs & Elledge, 1979) Combs, J., Elledge, B. EFFECTS OF A ROOM TAX ON RESORT HOTEL/MOTELS. Natl. Tax J. 1979, 32, 201–207. [CrossRef]

- Destination Marketing Association International. (2015). The new way for tourism bureaus measure their effectiveness. Available online: https://skift.com/2015/07/27/the-new-way-for-tourism-bureaus-measure-their-effectiveness/ (accessed on 3.02.2025).

- (do Valle et al. 2012) do Valle, P., Pintassilgo, P., Matias, A., Andre, F. Tourist attitudes towards an accommodation tax earmarked for environmental protection: A survey in the Algarve. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1408–1416. [CrossRef]

- Durán-Román, J.L.; Cárdenas-García, P.J.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. Tourist Tax to Improve Sustainability and the Experience in Mass Tourism Destinations: The Case of Andalusia (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Durbarry, 2008) Durbarry, R. Tourism taxes: Implications for tourism demand in the UK. Review of Development Economics 2008, 12, 21–36. [CrossRef]

- European Tourism Association. (2018). A tax on European tourism. Retrieved May 21, 2024. Available online: https://www.etoa.org/events/policy/regulation-and-taxation/tourist-taxes (accessed on 21.05.2024).

- European Union. (2017). The impact of taxes on the competitiveness of European tourism. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/130660/The%20Impact%20of%20Taxes%20on%20the%20Competitiveness%20of%20European%20tourism.pdf (accessed on 21.05.2024).

- Eurostat (2023). Tourism Satellite Accounts in Europe – 2023 edition, Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/7870049/16527548/KS-FT-22-011-EN-N.pdf/c0fa9583-b1c9-959a-9961-94ae9920e164?version=4.0&t=1683792112888 (accessed on 14.01.2025).

- FROT (2024). Available online: http://forumrot.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/WALNE-FROT-2023-r-06.02.23.pdf (accessed on 19.01.2025).

- (Gago et al., 2009) Gago, A., Labandeira, X., Picos, F., Rodríguez, M. Specific and general taxation of tourism activities. Evidence from Spain. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 381–392. [CrossRef]

- (Göktaş & Polat, 2019) Göktaş, L., Polat, S. Tourist tax for sustainability: Determining willingness to pay. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 35, 3503–3503. [CrossRef]

- (Gooroochurn & Sinclair, 2005) Gooroochurn, N., Sinclair, M. T. Tourist Tax Practices in European Union Member Countries and Its Applicability in Turkey. J. Tour. 2019. [CrossRef]

- (Gooroochurn & Sinclair, 2005) Gooroochurn, N., Sinclair, M. T. Economics of tourism taxation - evidence from Mauritius. Annals of Tourism Research 2005, 32, 478–498.

- Grobelna & Marciszewska, 2013) Grobelna, A., Marciszewska, B. Measurement of Service Quality in the Hotel Sector: The Case of Northern Poland. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 313–332. [CrossRef]

- (Gúčik & Hornok, 2021) Gúčik, M., Hornok, M. Accommodation tax as a source of revenue for budgets of local municipalities and tourism support in the Slovak Republic. In Wybrane aspekty działalności pozaprodukcyjnej na obszarach przyrodniczo cennych (pp. 161–171). Białystok: Wydawnictwo Ekomomia a Środowisko. ISBN 978-83-942623-8-9.

- (Heffer-Flaata et al., 2021) Heffer-Flaata, H., Voltes-Dorta, A., Suau-Sanchez, P. The Impact of Accommodation Taxes on Outbound Travel Demand from the United Kingdom to European Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 749–760. [CrossRef]

- Herman, G.V.; Grama, V.; Ilieș, A.; Safarov, B.; Ilieș, D.C.; Josan, I.; Buzrukova, M.; Janzakov, B.; Privitera, D.; Dehoorne, O.; et al. The Relationship between Motivation and the Role of the Night of the Museums Event: Case Study in Oradea Municipality, Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Herman et al., 2019) Herman, G. V., Wendt, J. A.,Dumbravă, R., Gozner, M. The role and importance of Promotion Centers in creating the image of tourist destination: Romania. Geogr. Pol. 2019, 92, 443–454. [CrossRef]

- (Hornok, 2022) Hornok, M. Potenciál dane za ubytovanie na Slovensku. Potential of accommodation tax in Slovakia. Ekonomická revue cestovného ruchu 2019, 52, 78–90.

- (Hornok, 2019) Hornok, M. Analýza výnosu dane za ubytovanie. Analysis of accommodation tax revenue. Ekonomická revue cestovného ruchu 2022, 55, 205–217.

- (Hornok, 2021) Hornok, M. A. Analýza návštevnosti ubytovacích zariadení a výnosu dane za ubytovanie. Ekonomická revue cestovného ruchu 2021, 54, 216–238.

- (Hornok, 2021) Hornok, M.B. A.Výnos dane za ubytovanie na Slovensku v rokoch 2019 a 2020. Accommodation tax revenue in Slovakia 2019 and 2020. Ekonomická revue cestovného ruchu 2021, 54, 72–85.

- (Idisondjaja et al., 2023) Idisondjaja, B. B., Wahyuni, S., Turino, H. The role of resource structuring, marketing, and networking capabilities in forming DMO orchestration capability toward sustainable value creation. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- (Ikeji Yamada, 2020) Ikeji, T., Yamada, Y. How to gain accommodation managers’ support for accommodation tax? Exploring the mediating role of perceived fairness. Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/entities/publication/1cfc94b0-7d13-4892-8c4b-a22a36d83efe (accessed on 5.12.2024).

- Japan National Tourism Organization. (2019). Kyoto accommodation tax. Available online: https://www.jnto.org.au/kyoto-accommodation-tax/ (accessed on 21.06.2024).

- (Laesser et al., 2023) Laesser, C., Küng, B., Beritelli, P., Boetsch, T., Weilenmann, T. (2023). Tourismus-Destinationen: Strukturen und Aufgaben sowie Herausforderungen und Perspektiven. Bericht im Auftrag des Staatssekretariats für Wirtschaft SECO. Bern: SECO.

- (Lee, 2014) Lee, S. K. Revisiting the impact of bed tax with spatial panel approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- (Leimgruber, 2021) Leimgruber, W. Tourism in Switzerland – How can the future be? Res. Glob. 2021, 3, 100058–100058. [CrossRef]

- (Lusticky & Kincl, 2012) Lusticky, M., Kincl, T. Tourism Destination Benchmarking: Evaluation and Selection of the Benchmarking Partners. J. Competitiveness 2012, 4, 99–116. [CrossRef]

- (Madsen & Johanson, 2022) Madsen, D. Ø., & Johanson, D. (2022). Benchmarking destinations. In D. Buhalis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing (pp. 287-290).

- (Mak & Nishimura, 1979) Mak, J., Nishimura, E. The Economics of a Hotel Room Tax. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 2–6. [CrossRef]

- (Monroy-Rodríguez & Caro-Carretero, 2023) Monroy-Rodríguez, S., Caro-Carretero, R. Congress tourism: Characteristics and application to sustainable tourism to facilitate collective action towards achieving the SDGs. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- (Notaro, et al., 2018) Notaro, S., Grilli, G., Paletto, A. The role of emotions on tourists’ willingness to pay for the Alpine landscape: a latent class approach. Landsc. Res. 2018, 44, 743–756. [CrossRef]

- (Nunkoo, 2015) Nunkoo, R. Tourism development and trust in local government. Tourism Management 2015, 46, 623–634. [CrossRef]

- (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2011) Nunkoo, R., Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ Satisfaction With Community Attributes and Support for Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 35, 171–190. [CrossRef]

- (Ortega-Rodríguez et al., 2024) Ortega-Rodríguez, C., Vena-Oya, J., Barreal, J., Józefowicz, B. How to finance sustainable tourism: Factors influencing the attitude and willingness to pay green taxes among university students. Green Finance 2024, 6, 649–665. [CrossRef]

- (Palmer & Riera, 2003). Palmer, T., Riera, A. Tourism and environmental taxes. With special reference to the "Balearic ecotax". Tourism Management 2003, 24, 665–674.

- (Ponjan & Thirawat, 2016) Ponjan, P., Thirawat, N. Impacts of Thailand’s tourism tax cut: A CGE analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 45–62. [CrossRef]

- (Piriyapada & Wang, 2015) Piriyapada, S., Wang, E. Modeling Willingness to Pay for Coastal Tourism Resource Protection in Ko Chang Marine National Park, Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 20, 515–540. [CrossRef]

- (Reinhold et al., 2018) Reinhold, S., Laesser, C., Beritelli, P. The 2016 St. Gallen Consensus on Advances in Destination Management. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 426–431. [CrossRef]

- Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 18 grudnia 2007 r. w sprawie warunków, jakie powinna spełniać miejscowość, w której można pobierać opłatę miejscową (Dz. U. z 2007 r., Nr 249, poz. 1851.

- (Safarov et al., 2023) Safarov, B., Taniev, A., Janzakov, B. THE IMPACT OF TAXES ON TOURISM BUSINESS (IN THE EXAMPLE OF SAMARKAND, UZBEKISTAN). Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2023, 48, 792–797. [CrossRef]

- (Sharma et al. , 2022) Sharma, A., Perdue, R. R., Nicolau, J. L. The Effect of Lodging Taxes on the Performance of US Hotels. J. Travel Res. 2020, 61, 108–119. [CrossRef]

- (Shao et al., 2021) Shao, Y., Hu, Z., Luo, M., Huo, T., Zhao, Q. What is the policy focus for tourism recovery after the outbreak of COVID-19? A co-word analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 899–904. [CrossRef]

- (Sheng & Tsui, 2009) Sheng, L., Tsui, Y. Taxing tourism: enhancing or reducing welfare? J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 627–635. [CrossRef]

- (Soares et al, 2022) Soares, J. R. R., Remoaldo, P., Perinotto, A. R. C., Gabriel, L. P. M. C., Lezcano-González, M.E., Sánchez-Fernández, M.-D. Residents’ Perceptions Regarding the Implementation of a Tourist Tax at a UNESCO World Heritage Site: A Cluster Analysis of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Land 2022, 11, 189. [CrossRef]

- (Sour & Arcos, 2024) Sour, L., Arcos, S. Comparative Analysis of Stochastic Frontier Efficiency in Payroll and Accommodation Tax Collection in Mexico (2010-2020). Apuntes del Cenes 2024, 43, 181–206.

- (Steffen et al., 2021); Steffen, A.; Stettler, J.; Huck, L. Feeling (un)welcome in Switzerland: The perception of commercial hospitality by domestic and international tourists. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 21, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Strydom et al., 2018); Strydom, A. J. , Mangope, D., & Henama, U. S. Lessons learned from successful community-based tourism case studies from the Global South. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 2018, 7. [Google Scholar]

- (Wszendybył-Skulska et al., 2024); Wszendybył-Skulska, E.; Najda-Janoszka, M.; Jezierski, A.; Kościółek, S.; Panasiuk, A. Exploring resilience of the hotel industry using the example of Polish regions: The case of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2024, 20, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Xiang et al., 2007); Xiang, Z. , Kothari, T., Hu, C., & Fesenmaier, D. R. Benchmarking as a strategic tool for destination management organizations: A proposed framework. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2007, 22, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- (Yu et al., 2023); Yu, J.; Safarov, B.; Yi, L.; Buzrukova, M.; Janzakov, B. The Adaptive Evolution of Cultural Ecosystems along the Silk Road and Cultural Tourism Heritage: A Case Study of 22 Cultural Sites on the Chinese Section of the Silk Road World Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).