1. Introduction

The human condition has, for millennia, been fundamentally framed by its finitude. The inescapable reality of death has served as the ultimate horizon against which questions of meaning, value, and authenticity are projected. However, the nascent field of biogerontology is progressively challenging this most basic of biological imperatives. A confluence of advanced research trajectories is rendering the hypothetical achievement of radical life extension—or even biological immortality—an increasingly plausible scenario, moving it from the realm of science fiction into a tangible subject for scientific and philosophical inquiry.

The scientific foundation for this paradigm shift is being laid in laboratories worldwide. Cutting-edge interventions are targeting the very mechanisms of aging. For instance, research into in vitro gametogenesis and the derivation of safe, adult, rapidly-dividing young stem cells points to a future where a person’s own aged, quiescent stem cell population could be replenished (Hayashi et al., 2011; Saitou & Miyauchi, 2016). The transplantation of such youthful, potent stem cells into an aging organism is hypothesized to not only replace senescent and old, slowly-dividing cells but also to increase the overall rate of tissue regeneration, effectively rejuvenating the organism (López-Otín et al., 2013; Tkemaladze, 2023). Furthermore, targeted senolytics—therapies designed to clear the body of senescent “zombie” cells that contribute to inflammation and aging—are showing remarkable efficacy in preclinical and early human models, restoring function and extending healthspan (Kirkland & Tchkonia, 2020; Tkemaladze, 2022). The synergistic application of these approaches—clearing the old and introducing the new—suggests a future where the degenerative process of aging could be halted or even reversed (Tkemaladze, 2024).

This impending biological revolution necessitates a profound and parallel examination of its psychological and existential consequences. For traditional existential philosophy and psychology, the awareness of mortality is not merely a morbid fact but the very cornerstone of a meaningful life. The central, unsettling question thus arises: What becomes of the human psyche, culture, and the very experience of meaning if this foundational cornerstone—our finitude—is technologically removed?

The prevailing concern is that the removal of death’s chronological limit would lead to an existential catastrophe: a state of profound apathy, infinite procrastination, and a devaluation of all experience, a concept often termed “the tedium of immortality” (Williams, 1973).

This article proposes a counter-hypothesis. It argues that in the context of biological immortality, the psychological phenomenon of death awareness does not simply vanish but undergoes a critical transformation. It ceases to function primarily as a chronological limit and is reconstituted as an “existential alarm clock.” This internal mechanism would no longer signal the impending end of biological time but would instead serve to awaken the individual from states of existential slumber, spiritual stagnation, and the psychological torpor induced by the prospect of unlimited time.

2. Theoretical Framework: From Finitude to Perpetuity

2.1. Death Awareness as a Constitutive Force

Existential psychology and terror management theory (TMT) have empirically demonstrated that mortality salience—the conscious or subconscious awareness of death—profoundly influences human behavior, from reinforcing cultural worldviews to motivating achievements and prosocial acts (Pyszczynski et al., 2015; Greenberg et al., 2014). This awareness acts as a psychological imperative that pulls individuals out of complacency and toward a more engaged and meaningful mode of being.

2.2. Defining Hypothetical Biological Immortality

Biological immortality here refers specifically to the elimination of senescence—the biological process of aging—not invulnerability (Maier, 2019). This entails the successful neutralization of the hallmarks of aging (López-Otín et al., 2013), thereby abolishing death from natural causes. The central paradox is that the elimination of death as a biological fact does not annul the existential questions of meaning, identity, and value; it may exacerbate them to an unprecedented degree.

Table 1.

Contrasting the Functions of Death Awareness in Mortal vs. Immortal Frameworks.

Table 1.

Contrasting the Functions of Death Awareness in Mortal vs. Immortal Frameworks.

| Aspect |

Mortality Framework (Current) |

Immortality Framework (Hypothetical) |

| Primary Function |

Chronological Limiter |

Qualitative Regulator (“Alarm Clock”) |

| Source of Urgency |

Scarcity of Time |

Poverty of Experience |

| Psychological Role |

Imposes finality, creates “being-toward-death” |

Prevents stagnation, enforces “becoming-within-life” |

| Cultural Manifestation |

Heroic projects of symbolic immortality (e.g., art, legacy) |

Narratives of identity transformation and perpetual meaning-making |

| Primary Existential Threat |

The reality of non-being |

The unreality of an “unlived” life |

3. The Existential Alarm Clock: Mechanism and Manifestations

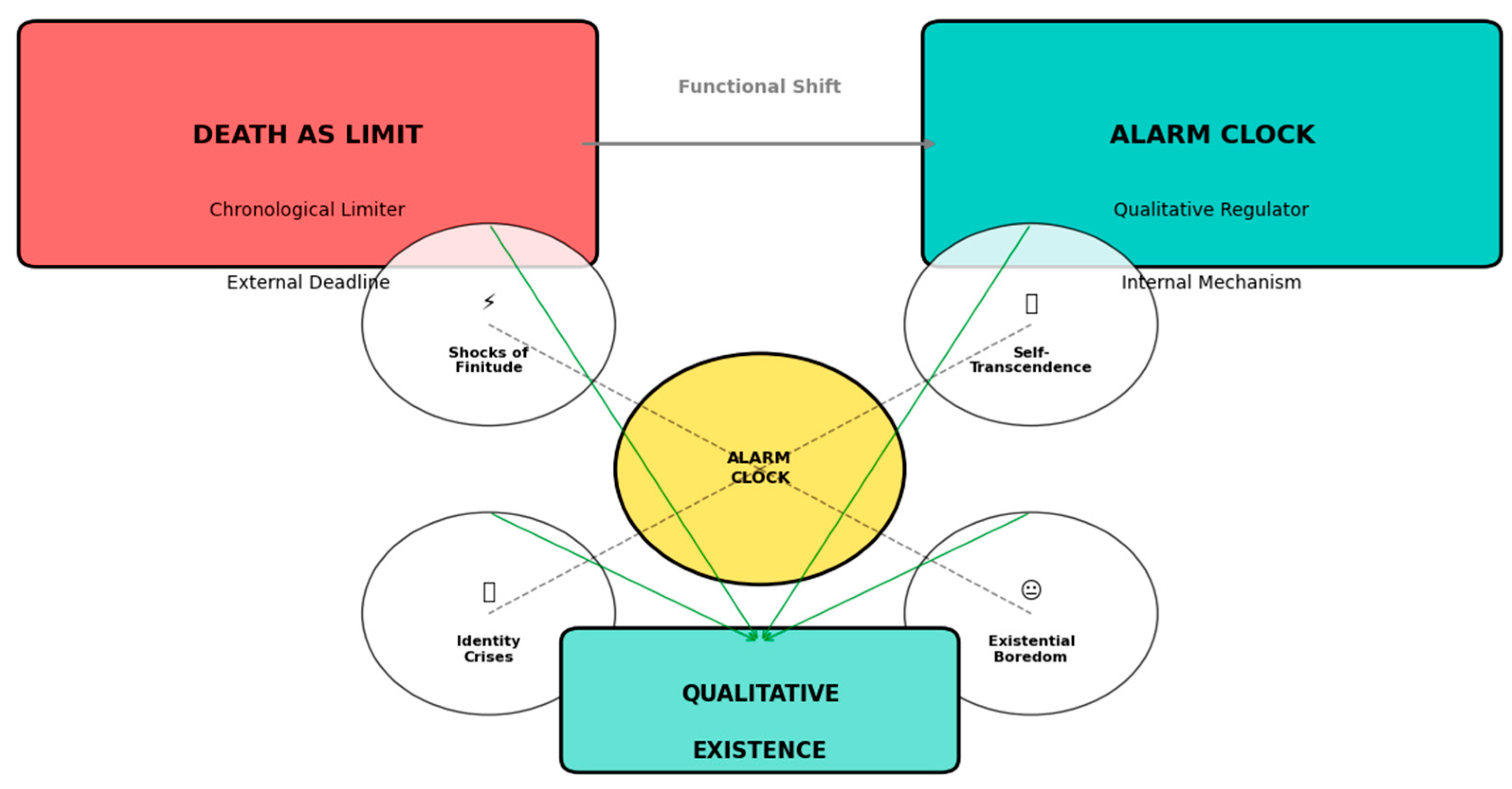

The proposed “existential alarm clock” is a cognitive-affective adaptation to the pathologies of perpetuity. Its mechanism is detailed in

Figure 1 and involves several key manifestations.

The reconstitution of death awareness into an existential alarm clock. The mechanism creates a feedback loop where psychological distress signals (the “alarm”) prompt course-correction towards a more engaged and meaningful existence.

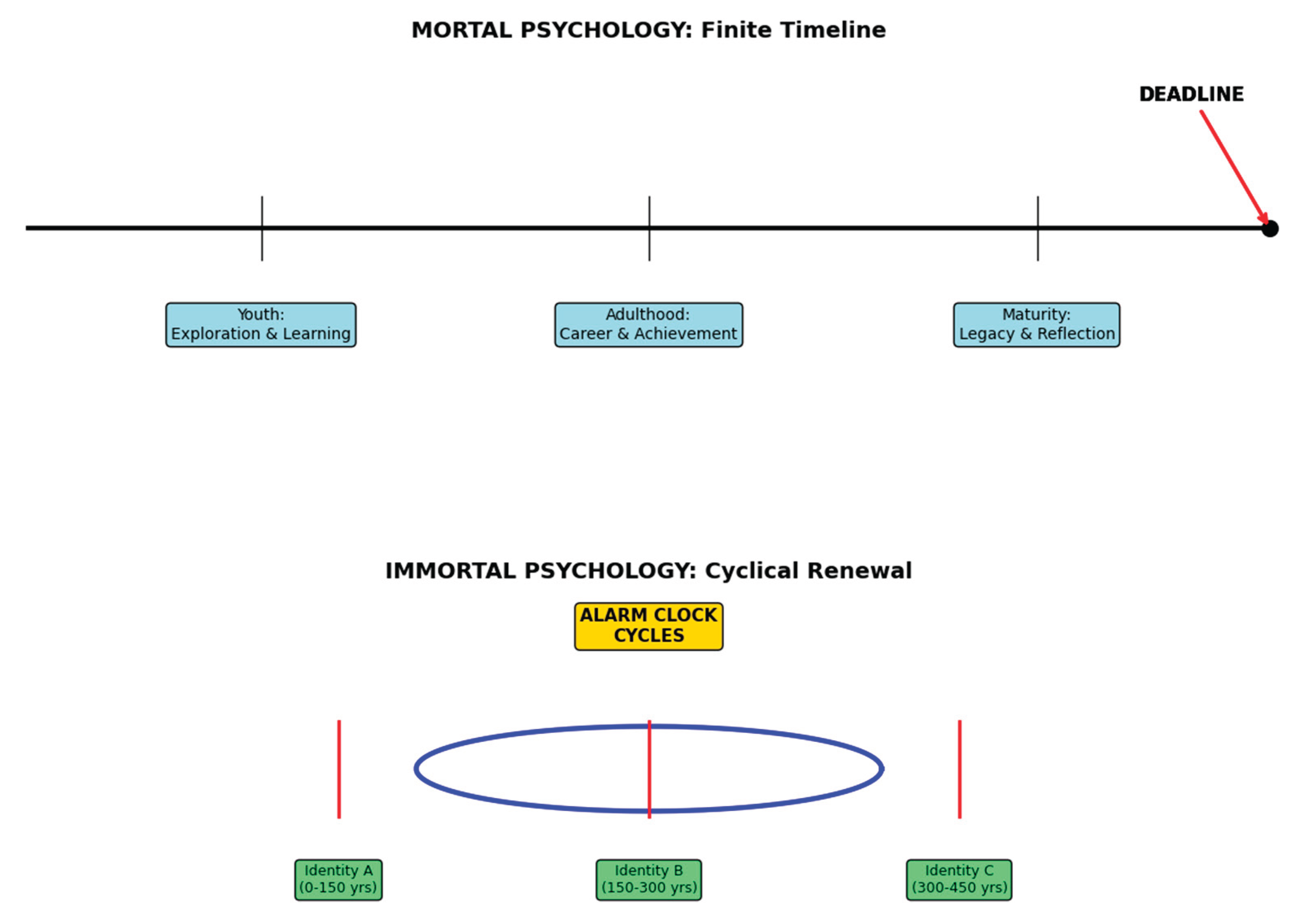

3.1. Identity Crises as a Catalyst for “Serial Selves”

In an immortal existence, the individual risks becoming trapped in a single, static identity. The existential alarm clock would sound through intense crises of identity, which would function as signals of the “death” of an outmoded self (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). This is a necessary catalyst for “serial selves” or “volitional re-identification,” a form of psychological rebirth essential for navigating an indefinitely long life (Sneed & Whitbourne, 2005). The alarm reminds one that while the body may persist, a self that does not evolve is, in a meaningful sense, already dead.

3.2. Combatting Existential Boredom and Apathy

A primary psychological threat of immortality is profound existential boredom—a pervasive sense of emptiness arising from perpetually available possibilities (Svendsen, 2005). The alarm clock would trigger in moments of deep, non-situational apathy, experienced as a crushing weight of insignificance. This feeling serves as a critical signal, mirroring the “awakening” experience described in terminal patients (Mogilner et al., 2018). It provokes the question: “If I have all the time in the world, why does none of it feel valuable?” This discomfort is the necessary impetus to seek out new challenges and re-engage with the world.

3.3. Shocks of Finitude in an Eternal Life

An immortal life could devolve into a “bad infinity”—a monotonous succession of days. The alarm clock would leverage residual finitude to break this cycle. Shocking events, such as the death of mortal loved ones, would take on a new symbolic function (O’Connell et al., 2021). For the immortal individual, these events become powerful, affective reminders of the fragility of connections and the irreplaceable uniqueness of each moment within the eternal flow.

3.4. The Stimulus for Self-Transcendence

Ultimately, the most critical function of the alarm clock is to propel the individual toward self-transcendence. In an immortal existence, the primary existential danger becomes a pathological self-absorption. The alarm would sound as a deep sense of existential guilt or emptiness arising from a life lived purely for oneself (Längle, 2016). This feeling catalyzes the dedication of one’s vast resources of time to a larger purpose: artistic or scientific creation, altruism, or cosmic exploration (Vos, 2018).

4. Projected Societal Transformations

The internal psychological shift would precipitate vast changes across society.

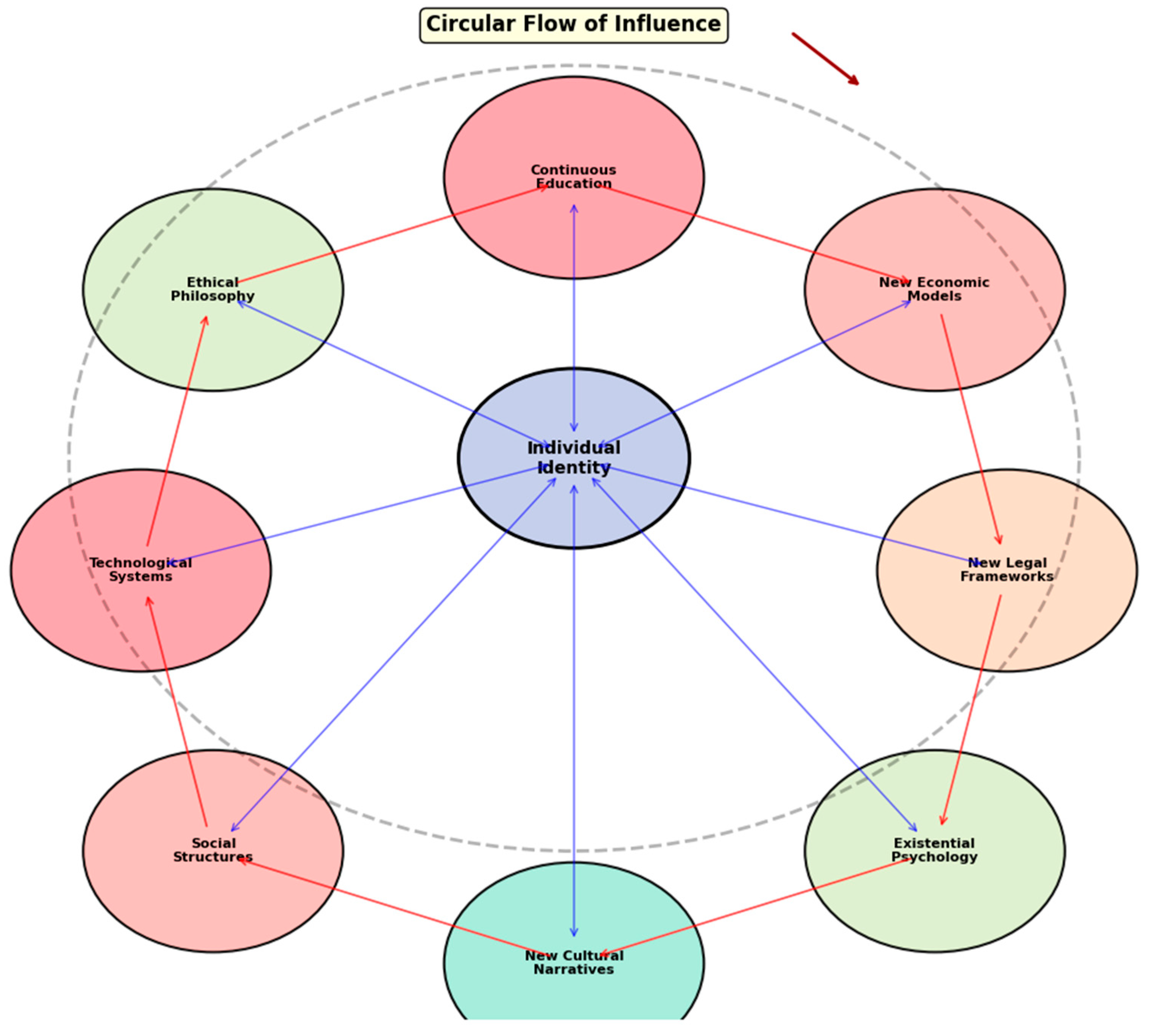

The societal transformations necessitated by biological immortality create an interconnected ecosystem where changes in one domain directly influence others, all centered on the psychological challenge of managing perpetual existence.

Figure 2.

The Interdisciplinary Ecosystem of an Immortal Society. A circular diagram showing the interconnectedness of transformed fields: Continuous Education feeding into New Economic Models, which are regulated by New Legal Frameworks, which are informed by Existential Psychology and Philosophy, which inspire New Cultural Narratives, which in turn influence individual identity and feed back into the education system.

Figure 2.

The Interdisciplinary Ecosystem of an Immortal Society. A circular diagram showing the interconnectedness of transformed fields: Continuous Education feeding into New Economic Models, which are regulated by New Legal Frameworks, which are informed by Existential Psychology and Philosophy, which inspire New Cultural Narratives, which in turn influence individual identity and feed back into the education system.

Table 2.

Projected Transformations of Social Institutions in an Immortal Society.

Table 2.

Projected Transformations of Social Institutions in an Immortal Society.

| Institution |

Current Model (Mortal) |

Future Model (Immortal) |

Key Driver |

| Education |

Front-loaded, for a finite career |

Continuous, cyclical, for identity renewal |

Need for “serial selves” (Kegan, 2018) |

| Psychology/Therapy |

Treats pathology, manages loss |

“Geronto-existential” practice for meaning-making |

Management of the existential alarm clock |

| Narrative Arts |

Conflict: “Human vs. Death” |

Conflict: “Identity vs. Stasis,” “Choice vs. Regret” |

Loss of death as a narrative driver (Schwartz, 2004) |

| Law & Ethics |

Right to life central |

Right to a self-determined death (“completion”) |

Ultimate autonomy in an endless life (Young & Earp, 2020) |

| Demographic Policy |

Models based on birth/death rates |

Strict reproduction regulation, static population models |

Resource sustainability (Maier, 2019) |

5. Limitations and Objections

The model faces significant challenges:

Diminished Salience: The alarm may lack the motivational power of a real, biological threat, as the neural systems for abstract versus concrete threats are distinct (LeDoux & Pine, 2016).

Adaptive Hedonism: The brain’s reward system could be perpetually satisfied through neurotechnology and virtual reality, anesthetizing the individual against the alarm entirely (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015; Savulescu & Persson, 2012).

Scope Limitation: The model is predicated on individual immortality and may not apply to a scenario where only the species is immortal through successive, mortal generations (Wade-Benzoni & Tost, 2009).

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

This analysis concludes that death awareness is an integral element of human consciousness whose biological elimination does not nullify its existential function. In hypothetical immortality, it reforms as an “existential alarm clock,” an internal regulator of qualitative existence. This mechanism awakens the individual from existential slumber, serving as a catalyst for continuous meaning-seeking, deep personal transformation, and self-transcendence.

The paradoxical, yet central, finding is that even under conditions of biological immortality, a dialogue with mortality remains a crucial precondition for a truly meaningful, authentic, and fulfilling life. The ultimate challenge of immortality may not be the extension of life, but the perpetual re-creation of a life worth extending. Future research must focus on empirical psychological simulations of extreme longevity and the development of ethical frameworks for a post-mortal society.

References

- Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron, 86(3), 646–664. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J., Vail, K., & Pyszczynski, T. (2014). Terror management theory and research: How the desire for death transcendence drives human behavior. In Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 35-53). Guilford Press.

- Hayashi, K., Ohta, H., Kurimoto, K., Aramaki, S., & Saitou, M. (2011). Reconstitution of the mouse germ cell specification pathway in culture by pluripotent stem cells. Cell, 146(4), 519–532. [CrossRef]

- Jaba, T. (2022). Dasatinib and quercetin: short-term simultaneous administration yields senolytic effect in humans. Issues and Developments in Medicine and Medical Research Vol. 2, 22-31.

- Kegan, R. (2018). What “form” transforms? A constructive-developmental approach to transformative learning. In Contemporary theories of learning (pp. 29-45). Routledge.

- Kirkland, J. L., & Tchkonia, T. (2020). Senolytic drugs: from discovery to translation. Journal of Internal Medicine, 288(5), 518–536. [CrossRef]

- Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 31-53). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Längle, A. (2016). The meaning of meaning-seeking in existential analysis. Existential Analysis, 27(1), 4-18.

- LeDoux, J. E., & Pine, D. S. (2016). Using neuroscience to help understand fear and anxiety: A two-system framework. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1083–1093. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194–1217. [CrossRef]

- Maier, B. (2019). How lifespan and healthspan are measured and the implications for biogerontology. Biogerontology, 20(5), 589–602. [CrossRef]

- Mogilner, C., Kamvar, S. D., & Aaker, J. (2018). The shifting meaning of happiness. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(4), 447–461. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, K., Berlant, E., & Przybylinski, E. (2021). Meaning making and death awareness: A systematic review. Death Studies, 45(10), 763-774. [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 1-70). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Saitou, M., & Miyauchi, H. (2016). Gametogenesis from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell, 18(6), 721–735. [CrossRef]

- Savulescu, J., & Persson, I. (2012). Moral enhancement, freedom and the God Machine. The Monist, 95(3), 399–421. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B. (2004). The paradox of choice: Why more is less. EClinicalMedicine, 15, 100-107. [CrossRef]

- Sneed, J. R., & Whitbourne, S. K. (2005). Models of the aging self. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 375-388. [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, L. (2005). A philosophy of boredom. Reaktion Books.

- Tkemaladze, J. (2022). Dasatinib and quercetin: short-term simultaneous administration yields senolytic effect in humans. Issues and Developments in Medicine and Medical Research Vol. 2, 22-31.

- Tkemaladze, J. (2023). Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: a consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells?. Molecular Biology Reports, 50(3), 2751-2761. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. (2024). Editorial: Molecular mechanism of ageing and therapeutic advances through targeting glycative and oxidative stress. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14, 1324446. [CrossRef]

- Vos, J. (2018). Meaning and meaning-making in cancer survivors: A meta-synthesis. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27(3), e1286. [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K. A., & Tost, L. P. (2009). The egoism and altruism of intergenerational behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(3), 165–193. [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. (1973). The Makropulos case: Reflections on the tedium of immortality. In Problems of the Self (pp. 82–100). Cambridge University Press.

- Young, M. J., & Earp, B. D. (2020). The meaning of “life” in the debate about assisted dying. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(4), 264-269. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).