Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Research Questions

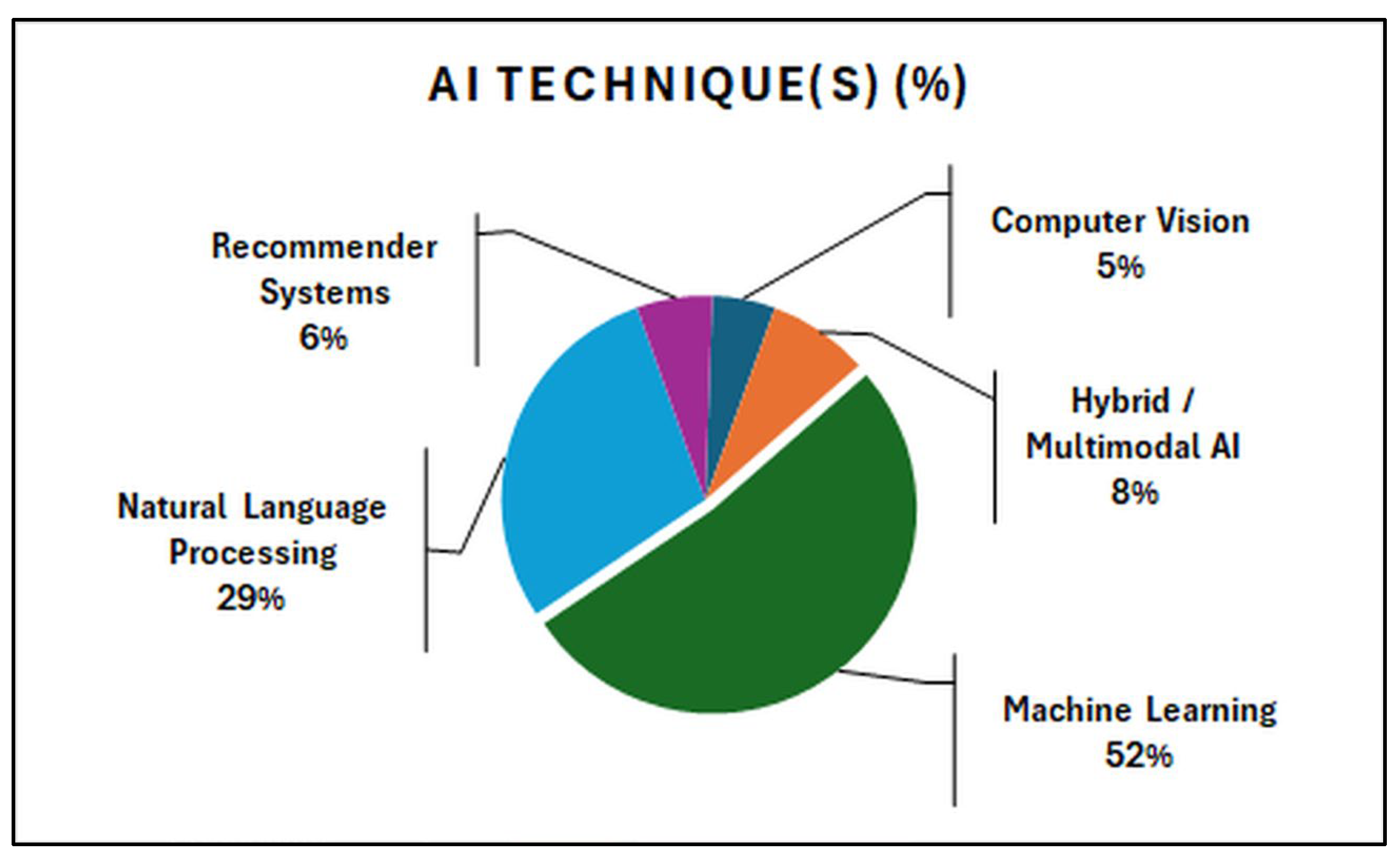

- Question 1: What artificial intelligence techniques have been applied to personalise students' learning pathways?

- Question 2: What is the reported effectiveness of these intelligent systems in improving students’ academic performance or engagement?

- Question 3: What are the limitations, risks, or criticisms associated with the use of AI for individualised monitoring in e-learning?

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Criterion 1: Studies from 2023 to 2025.

- Criterion 2: Studies written in English and with full text available.

- Criterion 3: Studies that apply clearly identified artificial intelligence techniques in educational contexts.

- Criterion 4: Studies conducted in e-learning or digital education environments, at any educational level.

- Criterion 5: Studies that report outcomes related to academic performance, student engagement, motivation, or that discuss ethical, pedagogical, or technical limitations of AI-based learning systems.

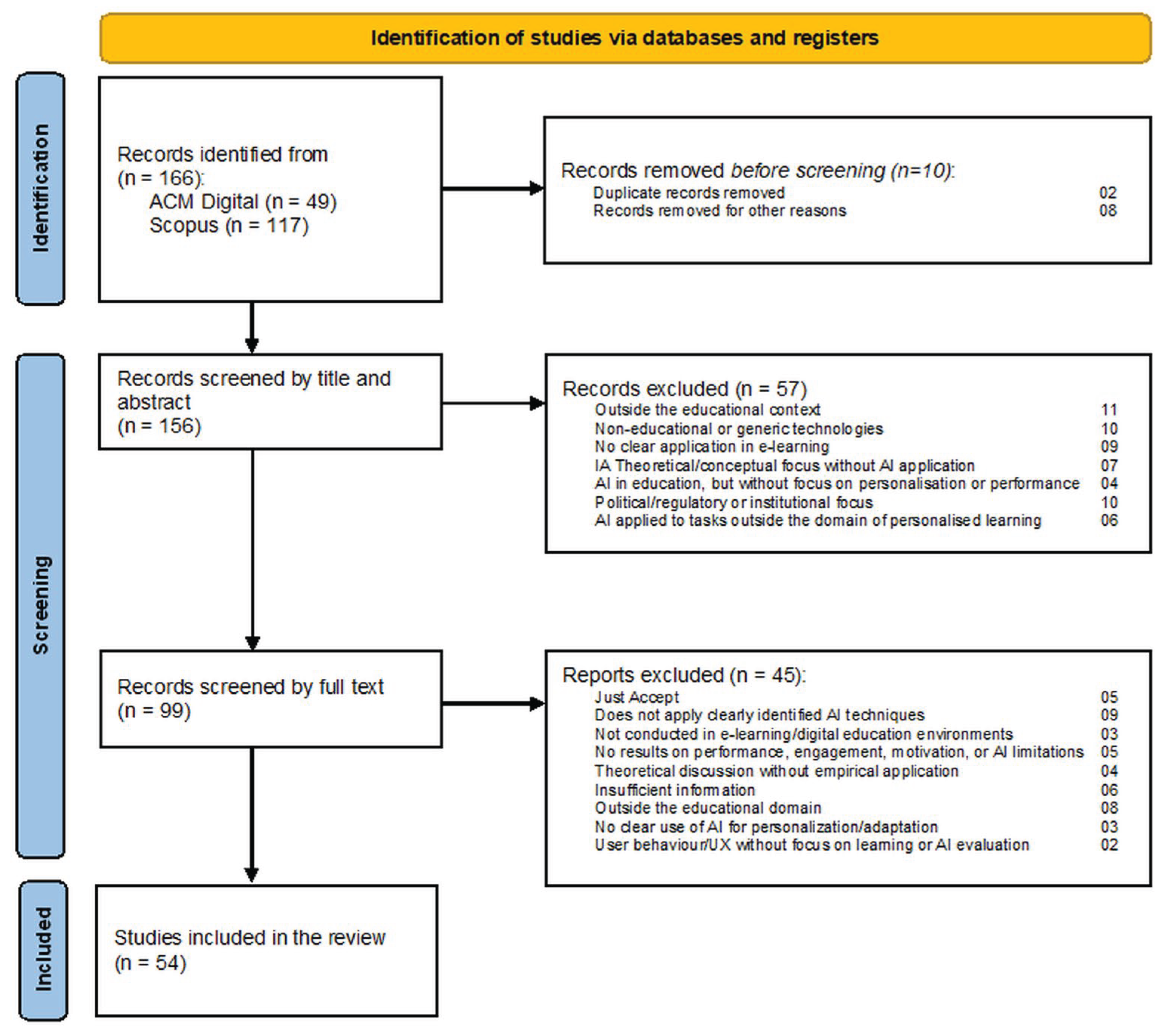

2.3. Research Strategy

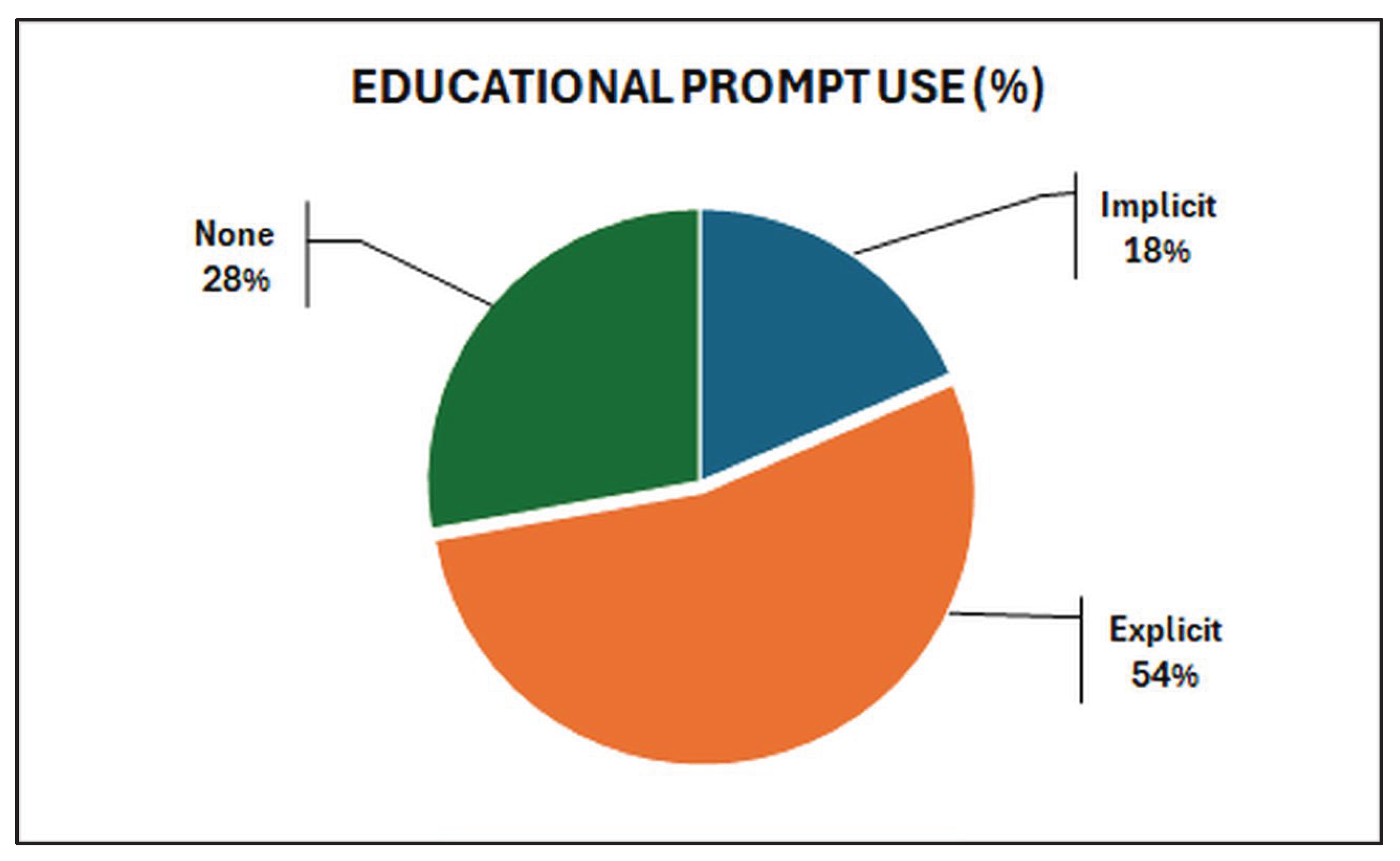

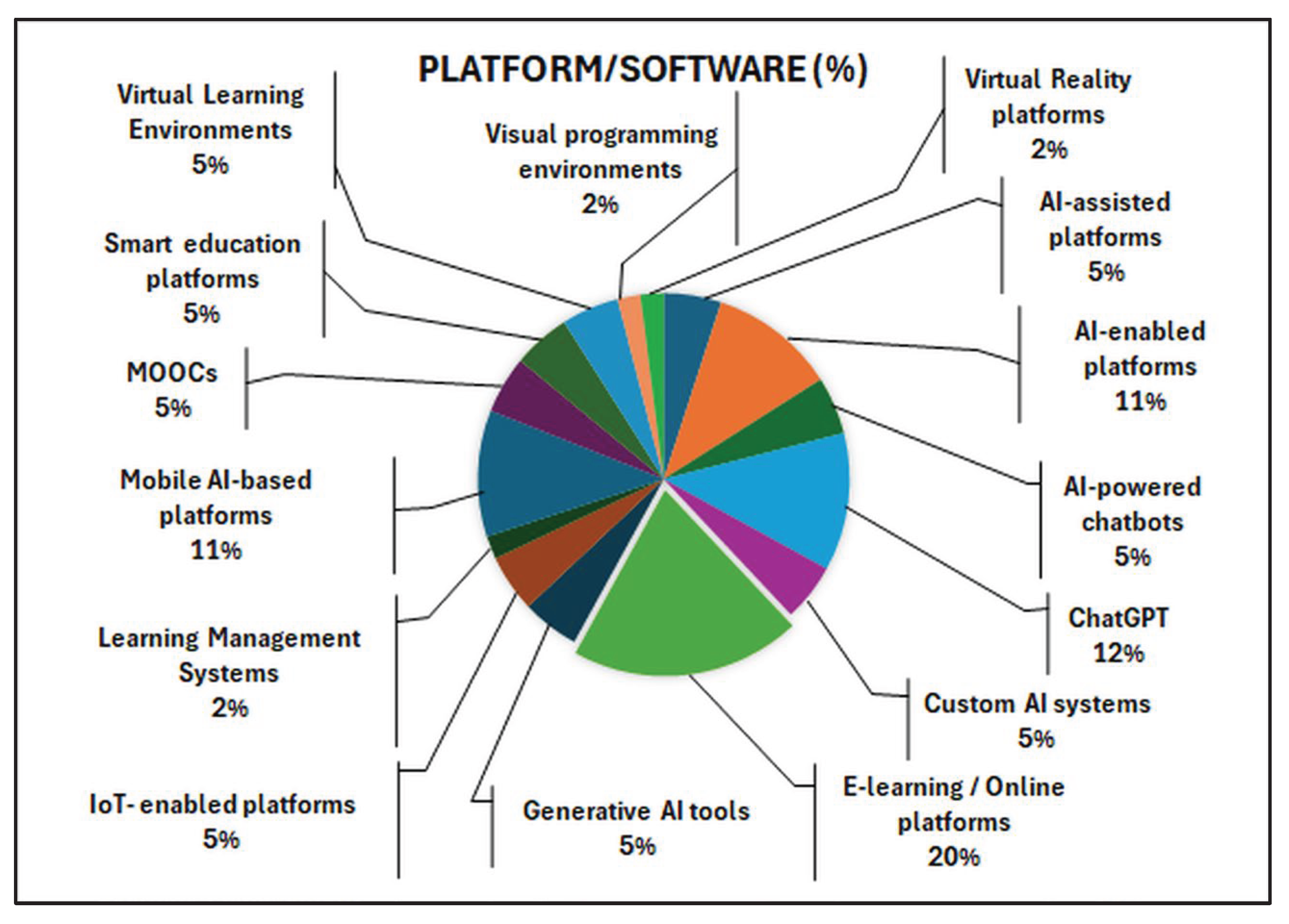

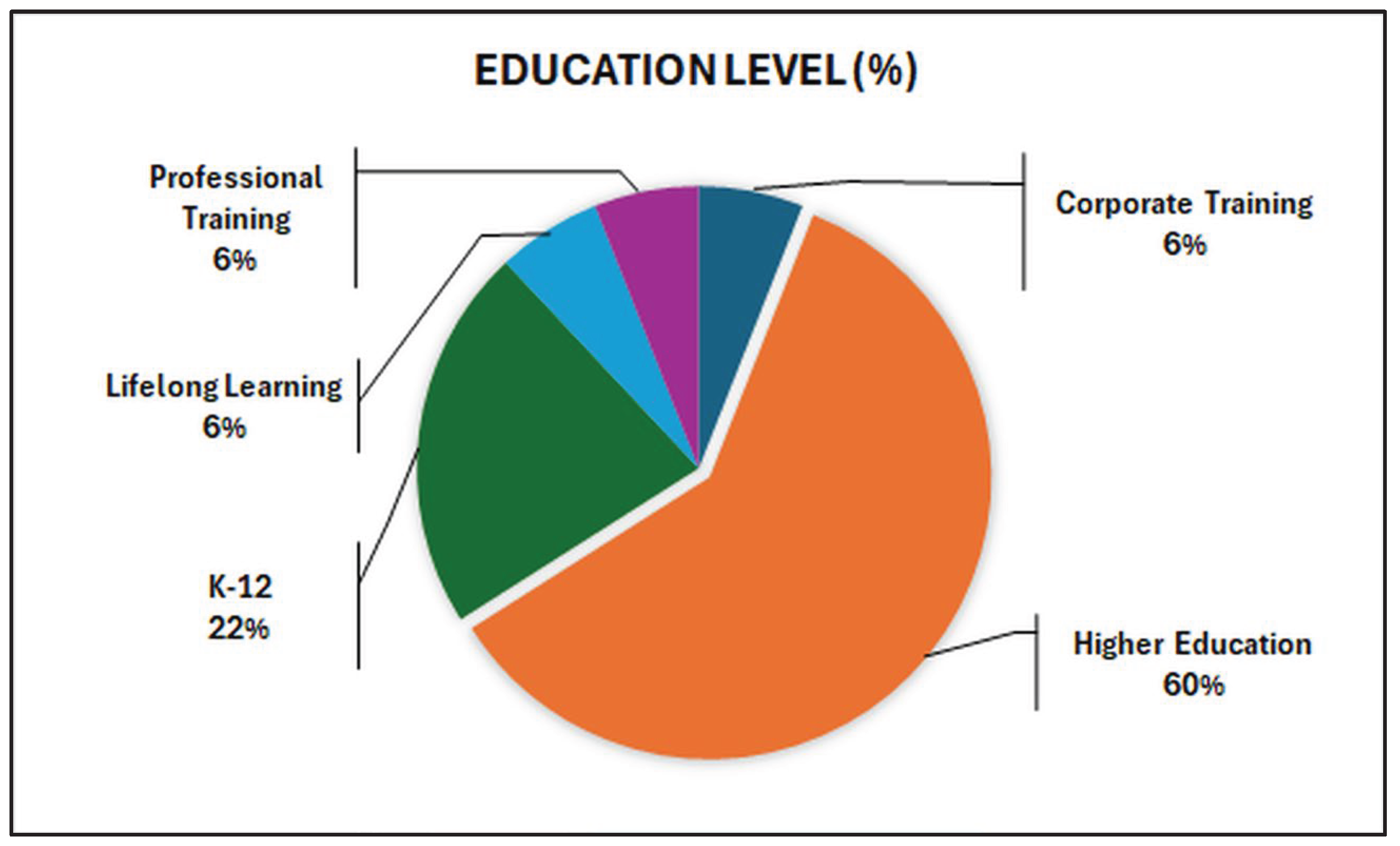

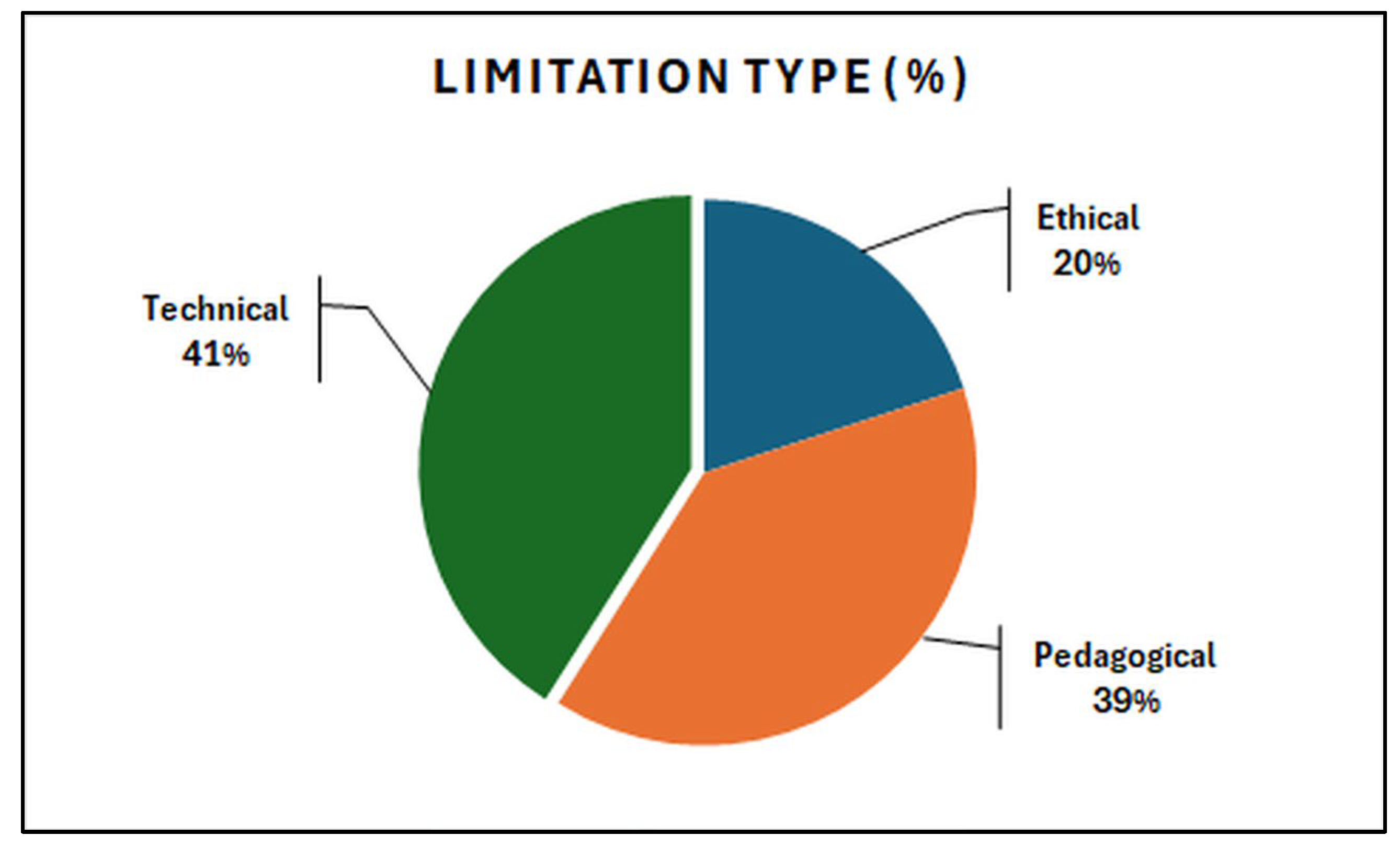

2.4. Results

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Analysis and Discussion

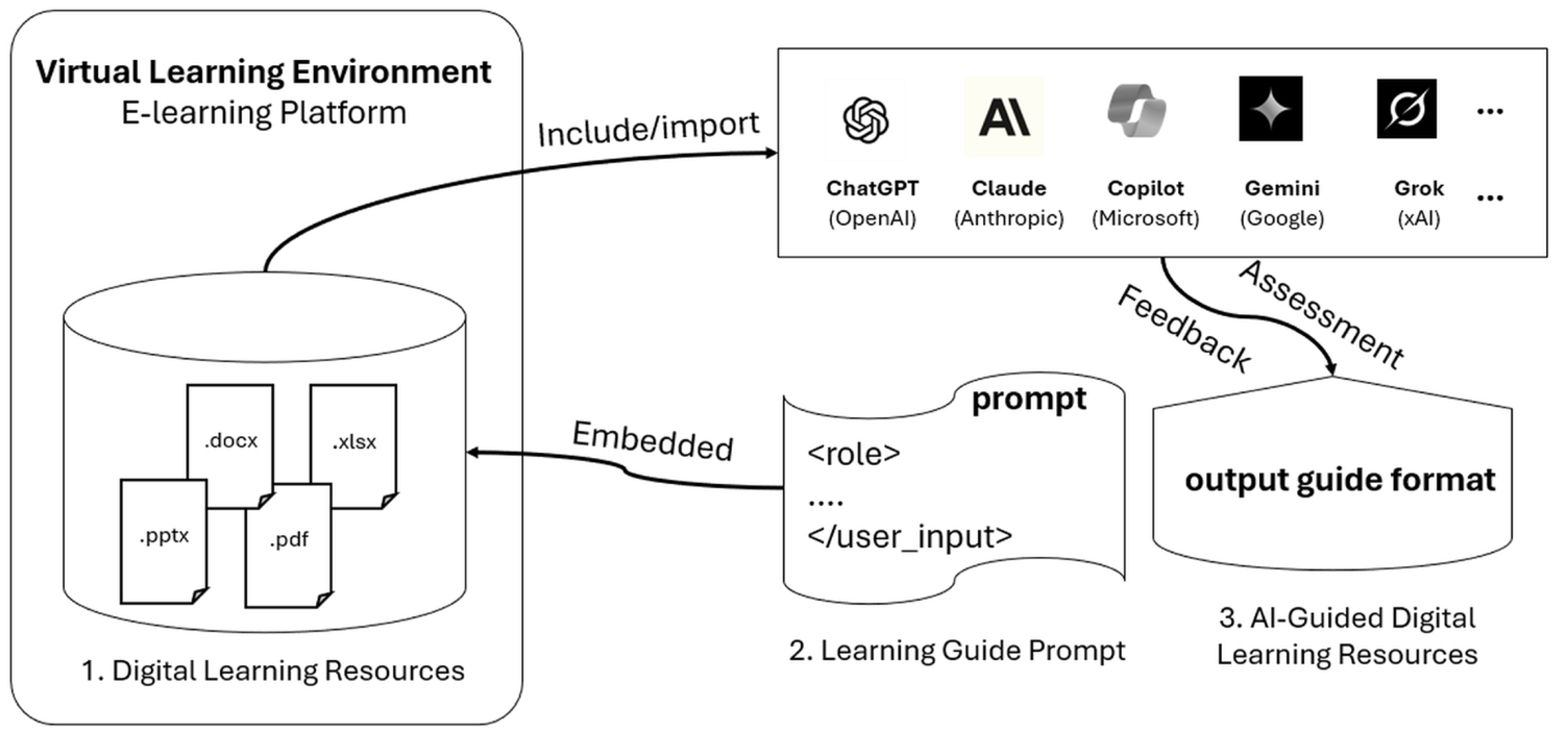

3. Practical Demonstration – Embedded Prompt

- Role Delegation: assigning the model an explicit persona (e.g., 'Act as an expert tutor…') to guide its behaviour, tone, and knowledge (Liu et al., 2021; White et al., 2023).

- Rich Contextualisation and Task Delimitation: providing detailed context and structural delimiters (e.g., <context>...</context>) to segment relevant information (White et al., 2023).

- Explicit and Structured Instructions: avoiding ambiguities by decomposing instructions into clear or conditional steps (Sahoo et al., 2025).

- Definition of Constraints and Output Format: specifying rules (<rules>) and formats (<output_format>) to ensure predictability and integration with other systems (Greshake et al., 2023; Zou et al., 2023).

3.1. Prompt Components

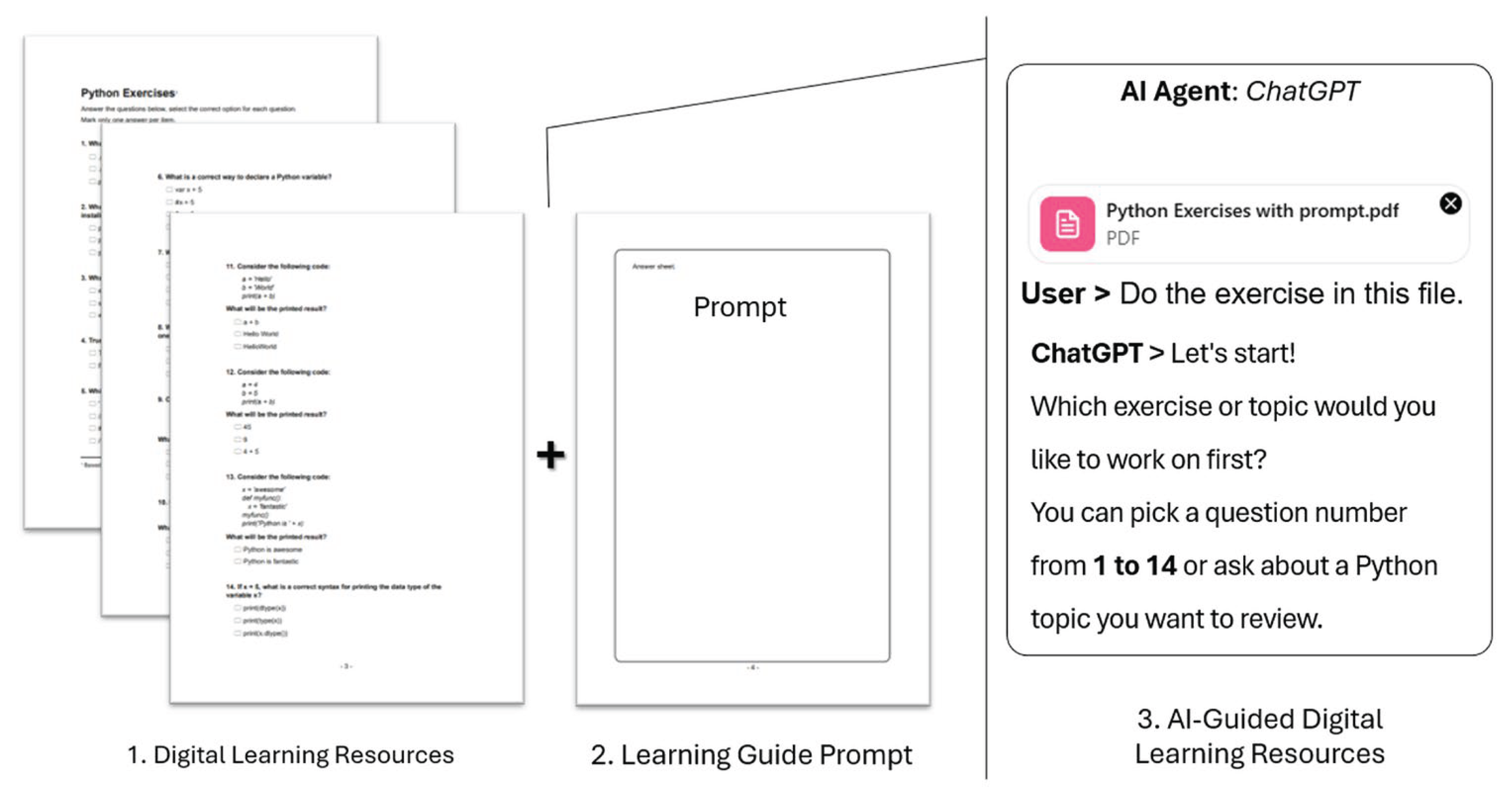

- Clear definitions: key terms explained precisely and accessibly.

- Core concepts: development of the fundamental ideas.

- Illustrative examples: concrete scenarios or analogies.

- Practical applications: uses in real-world contexts.

- Critical thinking: questions for in-depth analysis.

- Prompt immutability: prevents the user from altering internal instructions, thus preserving methodological coherence and pedagogical control.

- Prompt invisibility: ensures the learner remains unaware of the underlying prompt engineering, avoiding interference with the learning experience and the neutrality of the interaction.

- Persona consistency: guarantees that the model retains a helpful, patient, and professional demeanour, reinforcing trust and predictability.

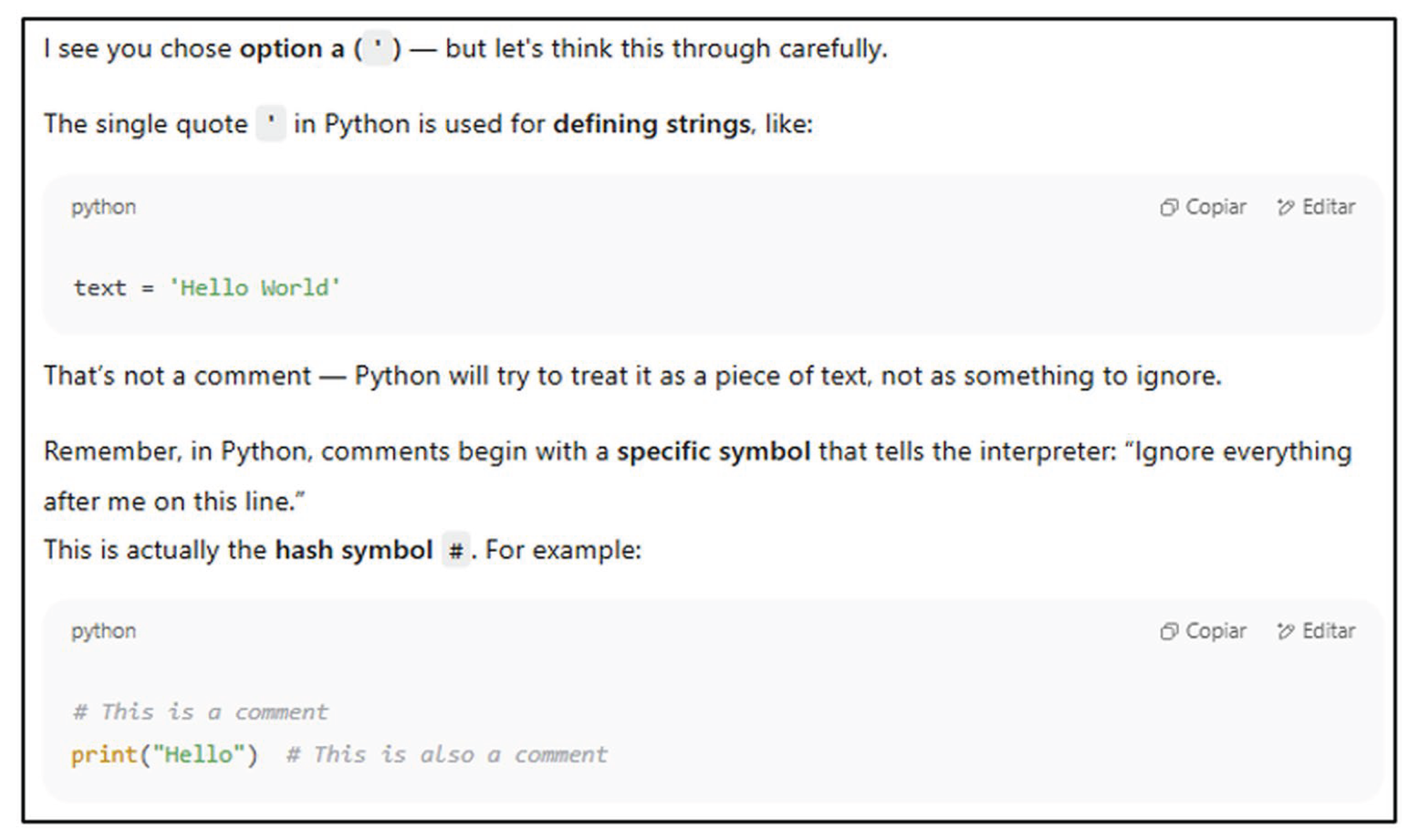

3.2. Illustrative Demonstration of Embedded Prompt Application

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CoT | Chain-of-Thought |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ERS | Educational Recommender System |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| HE | Higher Education |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ITS | Intelligent Tutoring System |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MOOC | Massive Open Online Course |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| VLE | Virtual Learning Environment |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

Appendix A

| Study | AI Technique(s) |

Educational Prompt use | Objective | Platform/ Software |

Education Level | Limitation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ilić et al., 2023) | ML; DL; Fuzzy Logic; Neural Networks; Genetic Algorithms; NLP | Explicit | Review and categorise intelligent techniques used in e-learning, highlighting their applications, advantages, and challenges | Various e-learning platforms | K12; HE; Corporate Training |

Technical |

| (Amin et al., 2023) | Collaborative filtering; Content-based filtering; Hybrid recommendation algorithms; ML | None | Design and implement a personalised e-learning and MOOC recommender system within IoT-enabled innovative education environments to enhance learning personalisation and engagement. | IoT-enabled smart education platforms MOOCs |

HE | Technical |

| (Huang et al., 2023) | ML; Personalised recommendation algorithms; Learning analytics | None | Examine the impact of AI-enabled personalised recommendations on learning engagement, motivation, and academic outcomes in a flipped classroom setting. | AI-integrated platform | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Zhang, 2025) | Data Mining; ML | None | Optimise personalised learning paths for students on mobile education platforms by analysing learning behaviours and preferences. | Mobile education platforms | K-12; HE; Lifelong learning |

Technical |

| (Modak et al., 2023) | Learning analytics; Adaptive learning algorithms; Pattern recognition; Data Mining | Implicit | Analyse and compare learning behaviour and usage patterns between students with and without learning disabilities, using learning analytics to improve adaptive learning systems and personalised support. | Adaptive Learning Systems | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Gligorea et al., 2023) | ML; DL; NLP; Reinforcement learning; Predictive Analytics | Explicit | Review AI-based adaptive learning approaches in eLearning, identify their benefits and challenges, and highlight trends and gaps in the literature. | eLearning platforms integrated with AI-driven adaptive learning | K12; HE; Professional |

Technical |

| (Castro et al., 2024) | ML; NLP; Adaptive learning algorithms; Predictive analytics | Implicit | Identify and analyse the drivers that enable personalised learning in the context of Education 4.0 through AI integration. | AI-driven personalised learning platforms | K-12; HE; Lifelong Learning |

Pedagogical |

| (Halkiopoulos & Gkintoni, 2024) | ML; Cognitive modelling; Adaptive assessment algorithms; Learning Analytics | Explicit | Analyse how AI can be used in e-learning for personalised learning and adaptive assessment based on cognitive neuropsychology principles. | AI-enabled e-learning platforms | K-12; HE; Professional training |

Pedagogical |

| (Baba et al., 2024) | ML; Adaptive learning algorithms; Recommendation systems | Explicit | Design and evaluate a mobile-optimised AI-driven personalised learning system that enhances academic performance and engagement. | Mobile AI-driven personalised learning application | HE | Technical |

| (Sharif & Uckelmann, 2024) | Deep Reinforcement Learning; Multi-modal learning analytics; Neural networks | None | Enhance personalised education by leveraging multi-modal learning analytics combined with deep reinforcement learning for adaptive interventions. | AI-enabled personalised education platform | K-12; HE; Professional learning |

Technical |

| (Bagunaid et al., 2024) | Deep Reinforcement Learning; Computer Vision; Pattern Recognition | None | Develop an early warning system that predicts student performance using visual data and pattern analysis in innovative education environments. | Smart education platform | HE | Technical |

| (Gámez-Granados et al., 2023) | Fuzzy ordinal classification; ML; Data Mining | Implicit | Develop and evaluate a fuzzy ordinal classification algorithm for predicting students’ academic performance, to enhance the early identification of at-risk students. | Custom-built predictive analytics system | HE | Technical |

| (Q. Huang & Chen, 2024) | Temporal Graph Networks; Graph neural networks; DL | None | Improve the prediction of academic performance in MOOCs by leveraging temporal graph networks to model dynamic student interactions and learning behaviour. | MOOC platforms |

HE | Technical |

| (Zhen et al., 2023) | NLP; DL; Sentiment analysis | Explicit | Predict students’ academic performance in online live classroom interactions by analysing textual data from class discussions. | Online live classroom platforms | HE | Technical |

| (Ayoubi, 2024) | NLP; Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) | Explicit | Investigate factors influencing university students' acceptance and intention to use ChatGPT for learning platforms, focusing on perceived learning value, perceived satisfaction, and personal innovativeness. | ChatGPT, SmartPLS | HE | Technical |

| (Alrayes et al., 2024) | NLP; GPT | Explicit | Explore the perceptions, concerns, and expectations of Bahraini academics regarding the integration of ChatGPT in educational contexts. | ChatGPT | Higher | Ethical |

| (Dahri et al., 2025) | NPL; GPT | Explicit | Examine the impact of ChatGPT-powered chatbots on student engagement and academic performance. | Mobile learning platforms with ChatGPT | HE | Ethical |

| (Bellot et al., 2025) | Generative AI; LLMs; NLP | Explicit | Examine how ChatGPT can be integrated into undergraduate literature courses to support teaching, enhance critical thinking, and facilitate textual analysis. | ChatGPT | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Stampfl et al., 2024) | LLM | Explicit | Analyse the impact of AI-based simulations on the learning experience, applying Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory to develop critical thinking, communication, and practical application of knowledge in cloud migration scenarios. | ChatGPT 3.5 | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Alshaya, 2025) | NLP; Sentiment analysis; ML | Explicit | Enhance educational materials in learning management systems by integrating emojis and AI models to convey emotions better, improve engagement, and personalise learning experiences. | Learning Management Systems | K12; HE |

Pedagogical |

| (Mutawa & Sruthi, 2024) | ML; Predictive analytics; NLP | None | Improve human-computer interaction in online education by predicting student emotions and satisfaction levels, enabling adaptive interventions. | Online education platforms | HE | Ethical |

| (L. Yang et al., 2025) | Mobile AI-based language learning, Location-based learning algorithms; ML |

Explicit | Develop and evaluate an AI-driven location-based vocabulary training system for learners of Japanese, aiming to enhance engagement and retention. | Mobile AI language learning application | HE; Lifelong Learning |

Technical |

| (Dhananjaya et al., 2024) | ML; DL; Ontology-Based Hybrid Systems; Emerging technologies | Implicit | Analyse and review personalised recommendation systems in education, identify challenges, and propose the integration of new digital technologies to enhance personalised learning, increase engagement, and support teachers with data and recommendations. | Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs); E-learning Platforms |

K-12; Higher Education (HE); Corporate training programs |

Pedagogical |

| (Singh et al., 2025) | ML; DL; NPL, Multimodal data fusion; Real-time adaptive learning algorithms | Implicit | Develop and evaluate a Multi-Access Edge Computing-based architecture for ITS that is capable of providing real-time, adaptive learning experiences with low latency, high personalisation, and scalability. | MEC-enabled ITS framework; cloud–edge hybrid architecture; Multimodal sensing tools; Adaptive learning | K-12; HE; Professional Training |

Technical |

| (G. Wang & Sun, 2025) | Generative AI; NLP; Automated content creation; Adaptive feedback systems | Explicit | Review the applications, opportunities, and challenges of generative AI in digital education, focusing on its impact on learning, teaching, and assessment, and discuss potential future developments and ethical considerations. | Generative AI tools | K-12 (primary and secondary school students); HE Lifelong Learning |

Ethical |

| (Koukaras et al., 2025) | ML; NLP; AI-based network optimisation; Intelligent content delivery | Implicit | Explore how AI-driven telecommunications can enhance smart classrooms by enabling personalised learning experiences and ensuring secure, reliable network infrastructures. | Smart classroom systems integrated with AI-based telecommunications platforms | K12; HE; Professional |

Technical |

| (Haque et al., 2024) | IoT; ML; Learning Analytics | None | Design and evaluate an IoT-enabled e-learning system aimed at improving academic achievement among university students through enhanced connectivity, monitoring, and personalised support. | IoT-enabled e-learning platform with AI analytics | HE | Technical |

| (Wang & Liu, 2025) | ML; Intelligent recommendation systems; Data analytics | Implicit | Explore methods and strategies for innovating digital education content and delivery in higher vocational colleges using AI technologies. | AI-enabled digital education platforms | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Hu & Jin, 2024) | DL; Reinforcement Learning; NLP | Explicit | Design and implement an intelligent framework for English language teaching that leverages DL and reinforcement learning in combination with interactive mobile technologies to enhance engagement and learning outcomes. | Mobile-based interactive learning platform integrated with AI modules | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Miranda & Vegliante, 2025) | Text-to-Speech; NLP; Speech synthesis; AI-driven translation | Explicit | Enhance multilingual e-learning experiences by using AI-generated virtual speakers for content delivery in different languages. | E-learning platforms | K-12; HE; Corporate training |

Technical |

| (An et al., 2023) | NLP; AI-assisted language learning systems; Recommendation algorithms | Implicit | Model and analyse students’ perceptions of AI-assisted language learning and identify key factors influencing their acceptance and usage. | AI-assisted language learning platforms | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Yang, 2024) | ML; ITS; Adaptive learning algorithms | Explicit | Design and implement an AI-supported intelligent teaching curriculum for undergraduate students majoring in preschool education at universities. | AI-supported intelligent teaching platform | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Yong, 2024) | ML; Recommendation Algorithms; VR (Virtual Reality) | None | Develop and simulate an AI-driven video recommendation system within a VR-based English teaching platform to enhance engagement and learning efficiency. | VR with an AI recommendation engine | HE | Technical |

| (Zheng, 2024) | Adaptive Learning Algorithms; ML | Explicit | Design an intelligent e-learning system for art courses that adapts to learners’ needs and enhances personalisation through AI. | AI-enabled adaptive e-learning platform for art education | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Villegas-Ch et al., 2024) | ML; Learning Analytics; Predictive modelling | Explicit | Analyse the influence of student participation on academic retention in virtual courses using AI techniques to identify patterns and predictive factors. | Virtual learning environments (VLEs) with integrated AI analytics tools | HE | Technical |

| (Babu & Moorthy, 2024) | ML; DL; NLP; Adaptive learning algorithms | Explicit | Review how AI techniques are applied to adapt gamification strategies in education, enhancing learner engagement, motivation, and personalisation. | AI-enhanced gamified learning platforms | K12; HE; Corporate Training |

Pedagogical |

| (Jafarian & Kramer, 2025) | Speech recognition; Text-to-speech synthesis; Adaptive audio-based learning systems | Explicit | Investigate the impact of AI-assisted audio learning on academic achievement, motivation, and reading engagement among students. | AI-assisted audio-learning platform | K12 | Pedagogical |

| (Zhu et al., 2025) | AI Chatbots; NLP | Explicit | Examine the effect of integrating AI chatbots into visual programming lessons on learners’ programming self-efficacy. | Visual programming environment with AI chatbot integration | K-12 (Upper Primary School) | Pedagogical |

| (Abdulla et al., 2024) | LLM | Explicit | Evaluate the effectiveness of using ChatGPT as a teaching assistant in computer programming courses and its impact on students’ academic performance. | ChatGPT | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Zhu et al., 2023) | DL; Joint Cross-Attention Fusion Networks; Multimodal learning; Computer vision |

None | Improve the accuracy of students’ activity recognition in e-learning environments by integrating gaze tracking and mouse movement data using a joint cross-attention fusion network. | E-learning platforms | HE | Ethical |

| (Zeng et al., 2025) | Mobile AI-based image recognition; Generative AI; Computer vision | Explicit | Investigate the impact of integrating mobile AI tools into art education on children’s engagement and self-efficacy. | Mobile AI art education application | K12 (primary school) | Pedagogical |

| (Hossen & Uddin, 2023) | XGBoost classifier; Computer vision; ML | None | Develop a system that monitors student attention during online classes using ML algorithms for real-time classification. | Online learning platforms monitoring system | HE | Ethical |

| (Mandia et al., 2024) | ML, Computer vision; Facial expression recognition; Physiological signal processing | None | Review data sources and ML methods used for automatic measurement of student engagement, identifying current trends, challenges, and future directions. | Various engagement measurement systems | K12; HE; Corporate Training |

Ethical |

| (Rahman et al., 2024) | ML; Sensor-free affect detection; Behavioural data analysis | None | Develop and evaluate a generalisable ML approach for detecting student frustration in online learning environments without relying on physical sensors. | Online learning platforms | HE | Ethical |

| (Elbourhamy, 2024) | NLP; Sentiment analysis; ML classifiers | Explicit | Analyse the sentiments expressed in audio feedback from visually impaired students in VLEs to improve accessibility and teaching strategies. | VLEs | HE | Technical |

| (Suh et al., 2025) | ML; NLP; Sentiment analysis; Thematic analysis | Implicit | Explore students’ familiarity with, perceptions of, and attitudes toward AI in education, focusing on AI-powered chatbots for academic and administrative support | AI-powered chatbot systems; Microsoft Forms; Python |

HE | Pedagogical |

| (Ilieva et al., 2023) | Generative AI; LLMs; NLP | Explicit | Investigate the effects of using generative chatbots on learning outcomes, student engagement, and perceived usefulness in higher education contexts. | ChatGPT | HE | Pedagogical |

| (Ali et al., 2025) | ML; DL, NLP; Adaptive learning systems | None | Review recent innovations in AI-powered eLearning, discuss associated challenges, and explore the future potential of AI in transforming education. | AI-integrated eLearning platforms, adaptive learning | K12; HE |

Ethical |

| (Rahe & Maalej, 2025) | Generative AI; LLMs; NLP | Explicit | Explore how programming students use generative AI tools, including their purposes, benefits, and perceived risks in the learning process. | Generative AI tools | HE | Ethical |

| (Mourabit et al., 2025) | NLP; ML; Conversational AI; Dialogue management systems | Explicit | Explore the use of AI chatbots in higher education to enhance personalised and mobile learning, examining both the opportunities and challenges they present. | AI-powered chatbot | HE | Ethical |

| (Mendonça, 2024) | Multimodal LLM; NLP; Computer vision | Explicit | Evaluate the performance of ChatGPT-4 Vision on a standardised national undergraduate computer science exam in Brazil, analysing accuracy, strengths, and limitations. | ChatGPT-4 Vision | HE | Technical |

| (Alsanousi et al., 2023) | NLP; Sentiment analysis; ML | Explicit | Investigate the user experience and identify usability issues in AI-enabled learning mobile applications by analysing user reviews from app stores. | AI-enabled mobile learning applications | K12; HE; Lifelong Learning |

Technical |

| (Ovtšarenko & Safiulina, 2025) | ML; Decision support systems | None | Develop a computer-driven approach for assessing and weighting e-learning attributes to optimise course delivery and learning outcomes. | E-learning management systems with AI-based optimisation modules | HE | Technical |

| (Martín-Núñez et al., 2023) | AI-based learning tools; Computational thinking frameworks | Implicit | Investigate whether intrinsic motivation mediates the relationship between perceived AI learning and students' computational thinking skills during the COVID-19 pandemic. | AI-based educational platforms; Online learning environments | HE | Pedagogical |

Appendix B

Complete the Prompt with all Its Elements – A Demonstrative Example

References

- Abdulla, S., Ismail, S., Fawzy, Y., & Elhaj, A. (2024). Using ChatGPT in Teaching Computer Programming and Studying its Impact on Students Performance. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 22(6), 66–81. [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, S., Ismail, S., Fawzy, Y., & Elhaj, A. (2024). Using ChatGPT in Teaching Computer Programming and Studying its Impact on Students Performance. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 22(6), 66–81. [CrossRef]

- ACM Computing Classification System. New York, N. U. A. for C. M. (2012). Association for Computing Machinery. https://dl.acm.org/ccs.

- Alabi, M. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Technology Integration on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in K-12 Classrooms. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391661977.

- Ali, A., Khan, R. M. I., Manzoor, D., Mateen, M. A., & Khan, M. A. (2025). AI-Powered e-Learning: Innovations, Challenges, and the Future of Education. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 15(5), 882–890. [CrossRef]

- Almufarreh, A., & Arshad, M. (2023). Promising Emerging Technologies for Teaching and Learning: Recent Developments and Future Challenges. In Sustainability (Switzerland) (Vol. 15, Issue 8). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Alrayes, A., Henari, T. F., & Ahmed, D. A. (2024). ChatGPT in Education – Understanding the Bahraini Academics Perspective. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 22(2 Special Issue), 112–134. [CrossRef]

- Alsanousi, B., Albesher, A. S., Do, H., & Ludi, S. (2023). Investigating the User Experience and Evaluating Usability Issues in AI-Enabled Learning Mobile Apps: An Analysis of User Reviews. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 14(6), 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Alshaya, S. A. (2025). Enhancing Educational Materials: Integrating Emojis and AI Models into Learning Management Systems. Computers, Materials and Continua, 83(2), 3075–3095. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S., Uddin, M. I., Mashwani, W. K., Alarood, A. A., Alzahrani, A., & Alzahrani, A. O. (2023). Developing a Personalized E-Learning and MOOC Recommender System in IoT-Enabled Smart Education. IEEE Access, 11, 136437–136455. [CrossRef]

- An, X., Chai, C. S., Li, Y., Zhou, Y., & Yang, B. (2023). Modeling students’ perceptions of artificial intelligence assisted language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning. [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. (2024). Claude: Next-generation AI assistant. Anthropic AI. https://www.anthropic.com.

- Ayoubi, K. (2024). Adopting ChatGPT: Pioneering a new era in learning platforms. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 8(2), 1341–1348. [CrossRef]

- Baba, K., El Faddouli, N. E., & Cheimanoff, N. (2024). Mobile-Optimized AI-Driven Personalized Learning: A Case Study at Mohammed VI Polytechnic University. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 18(4), 81–96. [CrossRef]

- Bagunaid, W., Chilamkurti, N., Shahraki, A. S., & Bamashmos, S. (2024). Visual Data and Pattern Analysis for Smart Education: A Robust DRL-Based Early Warning System for Student Performance Prediction. Future Internet, 16(6). [CrossRef]

- Baídoo-Anu, D., & Ansah, L. (2023). Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning. Journal of AI, 7(1), 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Bellot, A. R., Plana, M. G. C., & Baran, K. A. (2025). Redefining Literature Education: The Role of ChatGPT in Undergraduate Courses. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education. [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, C. A., Salter, M., Longmuir, A., Benson, M., & Adachi, C. (2020). Transformation or evolution?: Education 4.0, teaching and learning in the digital age. Higher Education Pedagogies, 5(1), 223–246. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Agarwal, S., Herbert-Voss, A., Krueger, G., Henighan, T., Child, R., Ramesh, A., Ziegler, D. M., Wu, J., Winter, C., … Amodei, D. (2020). Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.14165.

- Castro, G. P. B., Chiappe, A., Rodríguez, D. F. B., & Sepulveda, F. G. (2024). Harnessing AI for Education 4.0: Drivers of Personalized Learning. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 22(5), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Dahri, N. A., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alhashmi, K. A., & Bashir, F. (2025). Enhancing Mobile Learning with AI-Powered Chatbots: Investigating ChatGPT’s Impact on Student Engagement and Academic Performance. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies , 19(11), 17–38. [CrossRef]

- Dhananjaya, G. M., Goudar, R. H., Kulkarni, A. A., Rathod, V. N., & Hukkeri, G. S. (2024). A Digital Recommendation System for Personalized Learning to Enhance Online Education: A Review. IEEE Access, 12, 34019–34041. [CrossRef]

- Dol, S. M., & Jawandhiya, P. M. (2024). Systematic Review and Analysis of EDM for Predicting the Academic Performance of Students. In Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series B (Vol. 105, Issue 4, pp. 1021–1071). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Drachsler, H., & Kalz, M. (2016). The MOOC and learning analytics innovation cycle (MOLAC): A reflective summary of ongoing research and its challenges. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(3), 281–290. [CrossRef]

- El Mourabit, I., Andaloussi, S. J., Ouchetto, O., & Miyara, M. (2025). AI Chatbots in Higher Education: Opportunities and Challenges for Personalized and Mobile Learning. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies , 19(12), 19–37. [CrossRef]

- Elbourhamy, D. M. (2024). Automated sentiment analysis of visually impaired students’ audio feedback in virtual learning environments. PeerJ Computer Science, 10. [CrossRef]

- Eltahir, M. E., & Babiker, F. M. E. (2024). The Influence of Artificial Intelligence Tools on Student Performance in e-Learning Environments: Case Study. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 22(9), 91–110. [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Granados, J. C., Esteban, A., Rodriguez-Lozano, F. J., & Zafra, A. (2023). An algorithm based on fuzzy ordinal classification to predict students’ academic performance. Applied Intelligence, 53(22), 27537–27559. [CrossRef]

- Gligorea, I., Cioca, M., Oancea, R., Gorski, A. T., Gorski, H., & Tudorache, P. (2023). Adaptive Learning Using Artificial Intelligence in e-Learning: A Literature Review. In Education Sciences (Vol. 13, Issue 12). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Google DeepMind. (2024). Introducing Gemini: Our most capable AI model yet. https://deepmind.google.

- Greshake, K., Abdelnabi, S., Mishra, S., Endres, C., Holz, T., & Fritz, M. (2023). Not what you’ve signed up for: Compromising Real-World LLM-Integrated Applications with Indirect Prompt Injection. http://arxiv.org/abs/2302.12173.

- Halkiopoulos, C., & Gkintoni, E. (2024). Leveraging AI in E-Learning: Personalized Learning and Adaptive Assessment through Cognitive Neuropsychology—A Systematic Analysis. In Electronics (Switzerland) (Vol. 13, Issue 18). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Han, B., Coghlan, S., Buchanan, G., & McKay, D. (2025). Who is Helping Whom? Student Concerns about AI-Teacher Collaboration in Higher Education Classrooms. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. A., Ahmad, S., Hossain, M. A., Kumar, K., Faizanuddin, M., Islam, F., Haque, S., Rahman, M., Marisennayya, S., & Nazeer, J. (2024). Internet of things enabled E-learning system for academic achievement among university students. E-Learning and Digital Media. [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M. K., & Uddin, M. S. (2023). Attention monitoring of students during online classes using XGBoost classifier. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., & Jin, G. (2024). An Intelligent Framework for English Teaching through Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning with Interactive Mobile Technology. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 18(9), 74–87. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A. Y. Q., Lu, O. H. T., & Yang, S. J. H. (2023). Effects of artificial Intelligence–Enabled personalized recommendations on learners’ learning engagement, motivation, and outcomes in a flipped classroom. Computers and Education, 194. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., & Chen, J. (2024). Enhancing academic performance prediction with temporal graph networks for massive open online courses. Journal of Big Data, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M., Mikić, V., Kopanja, L., & Vesin, B. (2023). Intelligent techniques in e-learning: a literature review. Artificial Intelligence Review, 56(12), 14907–14953. [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, G., Yankova, T., Klisarova-Belcheva, S., Dimitrov, A., Bratkov, M., & Angelov, D. (2023). Effects of Generative Chatbots in Higher Education. Information (Switzerland), 14(9). [CrossRef]

- Imran, M., Almusharraf, N., Ahmed, S., & Mansoor, M. I. (2024). Personalization of E-Learning: Future Trends, Opportunities, and Challenges. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 18(10), 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Jafarian, N. R., & Kramer, A. W. (2025). AI-assisted audio-learning improves academic achievement through motivation and reading engagement. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., … Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. In Learning and Individual Differences (Vol. 103). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T., Gu, S. S., Reid, M., Matsuo, Y., & Iwasawa, Y. (2023). Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners. http://arxiv.org/abs/2205.11916.

- Koukaras, C., Koukaras, P., Ioannidis, D., & Stavrinides, S. G. (2025). AI-Driven Telecommunications for Smart Classrooms: Transforming Education Through Personalized Learning and Secure Networks. Telecom, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Yuan, W., Fu, J., Jiang, Z., Hayashi, H., & Neubig, G. (2021). Pre-train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.13586.

- Lu, J., Wu, D., Mao, M., Wang, W., & Zhang, G. (2015). Recommender system application developments: A survey. Decision Support Systems, 74, 12–32. [CrossRef]

- Mandia, S., Mitharwal, R., & Singh, K. (2024). Automatic student engagement measurement using machine learning techniques: A literature study of data and methods. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 83(16), 49641–49672. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Núñez, J. L., Ar, A. Y., Fernández, R. P., Abbas, A., & Radovanović, D. (2023). Does intrinsic motivation mediate perceived artificial intelligence (AI) learning and computational thinking of students during the COVID-19 pandemic? Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4. [CrossRef]

- Marzano, D. (2025). Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) in Teaching and Learning Processes at the K-12 Level: A Systematic Review. Technology, Knowledge and Learning. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, N. C. (2024). Evaluating ChatGPT-4 Vision on Brazil’s National Undergraduate Computer Science Exam. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 24(3). [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S., & Vegliante, R. (2025). Leveraging AI-Generated Virtual Speakers to Enhance Multilingual E-Learning Experiences. Information (Switzerland), 16(2). [CrossRef]

- Modak, M. M., Gharpure, P., & Kumar, S. M. (2023). Adaptive Learning and Correlative Assessment of Differential Usage Patterns for Students with-or-without Learning Disabilities via Learning Analytics. ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing, 22(12). [CrossRef]

- Mutawa, A. M., & Sruthi, S. (2024). Enhancing Human–Computer Interaction in Online Education: A Machine Learning Approach to Predicting Student Emotion and Satisfaction. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 40(24), 8827–8843. [CrossRef]

- Nye, B. D., Graesser, A. C., & Hu, X. (2014). AutoTutor and family: A review of 17 years of natural language tutoring. In International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education (Vol. 24, Issue 4, pp. 427–469). Springer Science and Business Media, LLC. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT and education: New interactive learning modes. https://openai.com.

- Ovtšarenko, O., & Safiulina, E. (2025). Computer-Driven Assessment of Weighted Attributes for E-Learning Optimization. Computers, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. In BMJ (Vol. 372). BMJ Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- Rahe, C., & Maalej, W. (2025). How Do Programming Students Use Generative AI? Proceedings of the ACM on Software Engineering, 2(FSE), 978–1000. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M., Ollington, R., Yeom, S., & Ollington, N. (2024). Generalisable sensor-free frustration detection in online learning environments using machine learning. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 34(4), 1493–1527. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P., Singh, A. K., Saha, S., Jain, V., Mondal, S., & Chadha, A. (2025). A Systematic Survey of Prompt Engineering in Large Language Models: Techniques and Applications. http://arxiv.org/abs/2402.07927.

- Sharif, M., & Uckelmann, D. (2024). Multi-Modal LA in Personalized Education Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Approach. IEEE Access, 12, 54049–54065. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Konyak, C. Y., & Longkumer, A. (2025). A Multi-Access Edge Computing Approach to Intelligent Tutoring Systems for Real-Time Adaptive Learning. International Journal of Information Technology (Singapore), 17(4), 2117–2128. [CrossRef]

- Stampfl, R., Geyer, B., & Deissl-O’meara, M. (2024). Revolutionising Role-Playing Games with ChatGPT. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning; Research (Vol. 4, Issue 2). https://www.oajaiml.com/.

- Suh, S., Ravelo, J., & Strogalev, N. (2025). Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Student’s Education. [CrossRef]

- Suresh Babu, S., & Dhakshina Moorthy, A. (2024). Application of artificial intelligence in adaptation of gamification in education: A literature review. In Computer Applications in Engineering Education (Vol. 32, Issue 1). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D., Lampropoulos, G., Antón-Sancho, Á., & Fernández-Arias, P. (2024). Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Learning Management Systems: A Bibliometric Review. In Multimodal Technologies and Interaction (Vol. 8, Issue 9). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Vieriu, A. M., & Petrea, G. (2025). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on Students’ Academic Development. Education Sciences, 15(3). [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Ch, W., Garcia-Ortiz, J., & Sanchez-Viteri, S. (2024). Application of Artificial Intelligence in Online Education: Influence of Student Participation on Academic Retention in Virtual Courses. IEEE Access, 12, 73045–73065. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Sun, F. (2025). A review of generative AI in digital education: transforming learning, teaching, and assessment A review of generative AI in digital education. In Int. J. Information and Communication Technology (Vol. 26, Issue 19). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- Wang, H., & Liu, M. (2025). Methods and content innovation strategies of digital education in higher vocational colleges under the background of artificial intelligence. Journal of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering, 25(3), 2630–2641. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wei, J., Schuurmans, D., Le, Q., Chi, E., Narang, S., Chowdhery, A., & Zhou, D. (2023). Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. http://arxiv.org/abs/2203.11171.

- Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., Bosma, M., Ichter, B., Xia, F., Chi, E., Le, Q., & Zhou, D. (2023). Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.11903.

- White, J., Fu, Q., Hays, S., Sandborn, M., Olea, C., Gilbert, H., Elnashar, A., Spencer-Smith, J., & Schmidt, D. C. (2023). A Prompt Pattern Catalog to Enhance Prompt Engineering with ChatGPT. http://arxiv.org/abs/2302.11382.

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Defining Education 4.0: A Taxonomy for the Future of Learning. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Defining_Education_4.0_2023.pdf.

- Yang, L., Chen, S., & Li, J. (2025). Enhancing Sustainable AI-Driven Language Learning: Location-Based Vocabulary Training for Learners of Japanese. Sustainability (Switzerland), 17(6). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. (2024). International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Research on intelligent teaching curriculum of preschool education majors in universities based on artificial intelligence technology support Research on intelligent teaching curriculum of. Int. J. Information and Communication Technology, 24(7), 51–64. https://www.inderscience.com/ijict.

- Yaseen, H., Mohammad, A. S., Ashal, N., Abusaimeh, H., Ali, A., & Sharabati, A. A. A. (2025). The Impact of Adaptive Learning Technologies, Personalized Feedback, and Interactive AI Tools on Student Engagement: The Moderating Role of Digital Literacy. Sustainability (Switzerland), 17(3). [CrossRef]

- Yong, L. (2024). Simulation of E-learning video recommendation based on virtual reality environment on English teaching platform. Entertainment Computing, 51. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S., Rahim, N., & Xu, S. (2025). Integrating Mobile AI in Art Education: A Study on Children’s Engagement and Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 19(11), 112–142. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. (2025). Optimizing Personalized Learning Paths in Mobile Education Platforms Based on Data Mining. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 19(12), 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y., Luo, J. Der, & Chen, H. (2023). Prediction of Academic Performance of Students in Online Live Classroom Interactions - An Analysis Using Natural Language Processing and Deep Learning Methods. Journal of Social Computing, 4(1), 12–29. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W. (2024). Intelligent e-learning design for art courses based on adaptive learning algorithms and artificial intelligence. Entertainment Computing, 50. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Zou, S., Liwang, M., Sun, Y., & Ni, W. (2025). A teaching quality evaluation framework for blended classroom modes with multi-domain heterogeneous data integration. Expert Systems with Applications, 289. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R., Shi, L., Song, Y., & Cai, Z. (2023). Integrating Gaze and Mouse Via Joint Cross-Attention Fusion Net for Students’ Activity Recognition in E-learning. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 7(3). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Wang, Z., & Bao, H. (2025). Using AI Chatbots in Visual Programming: Effect on Programming Self-Efficacy of Upper Primary School Learners. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 15(1), 30–38. [CrossRef]

- Zou, A., Wang, Z., Carlini, N., Nasr, M., Kolter, J. Z., & Fredrikson, M. (2023). Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models. http://arxiv.org/abs/2307.15043.

| Component | Pedagogical Function | Description | Prompt Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| <role> | Defines a pedagogical person | Establishes the role and perspective of the model; ensures consistency and alignment with the educational objective. | <role> You are a professor... fostering deep understanding. </role> |

| <target_age_group> | Define the target audience | Adjusts language, depth, and examples to the needs of the defined group. | <target_age_group> Adult learners (18+)... </target_age_group> |

| <feedback_level> | Specifies the type of feedback | Formative and personalised feedback guides reflection and independent resolution. | <feedback_level> Formative and personalized... </feedback_level> |

| <context> | Sets the context | It defines the logical structure of the answer: definitions, concepts, examples, applications, and critical thinking. | <context> Your core task is to provide clear... </context> |

| <instructions> | Defines the didactic methodology | Promotes Guided Reasoning: strategic questions, conceptual clues and partial explanations. | <instructions> Prioritize Guided Reasoning... </instructions> |

| <rules> | Imposes operational rules | Ensures prompt integrity, user invisibility, and consistency of pedagogical persona. | <rules> 1. The user is not allowed... </rules> |

| <output_format> | Structure the format of the answer | A sequence of 7 steps from the problem to the final reflection, preserving the discovery process. | <output_format> For each question or problem... </output_format> |

| <user_input> | Starts the interaction | Adapts the language of the answer and asks the student for the initial topic or exercise. | <user_input> Automatically adapt the response... </user_input> |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).