1. Introduction

Parotid gland lesions have long posed diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to their histological diversity and close anatomical proximity to the facial nerve. They encompass a broad etiological spectrum, including benign and malignant neoplasms, inflammatory conditions, and obstructive pathologies such as sialolithiasis [

1]. Parotid tumors are rare entities, accounting for approximately 3% of all head and neck tumors [

2]. Clinically, they often present as preauricular masses, with approximately three-quarters being benign and less than one-quarter malignant [

3,

4].

The most common benign tumor of the parotid gland is pleomorphic adenoma, followed by Warthin tumor, while mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most frequent malignant entity. Among non-neoplastic lesions, inflammatory conditions are predominant [

5,

6].

Diagnostic evaluation typically involves imaging techniques such as ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT), complemented by fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). However, the sensitivity and specificity of these tools are limited, and definitive diagnosis relies on histopathological examination [

7].

Surgical excision is the cornerstone of treatment for parotid tumors. Nevertheless, parotidectomy poses considerable technical challenges due to the intricate anatomical relationship between the gland and the facial nerve. The branching of the nerve within the gland increases the risk of iatrogenic injury, potentially resulting in functional and aesthetic deficits such as facial paralysis.

This retrospective study seeks to provide insight into clinicopathological patterns and surgical outcomes following parotidectomy, emphasizing facial nerve complications and histopathological diversity.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective observational study included 314 patients who underwent parotidectomy between 2008 and 2024 at Izmir Tepecik Training and Research Hospital, a tertiary care center. All procedures were performed by a dedicated head and neck surgical team with substantial experience in parotid gland surgery.

Data were retrieved from electronic medical records and included demographic details (age, sex, country of birth), tumor characteristics (laterality and histopathological classification as non-neoplastic, benign, or malignant), and histological features such as necrosis, capsular invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion. Postoperative complications, with a focus on facial nerve paralysis, were also documented.

Histopathological diagnoses were based on postoperative tissue analyses conducted by experienced pathologists. In cases of diagnostic ambiguity, specimens were re-evaluated by a senior pathologist to ensure consistency and diagnostic accuracy.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), as well as minimum and maximum values. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. For categorical variables, the Chi-square test was applied. Continuous variables were compared using the independent t-test or one-way ANOVA, as appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval was obtained from the local institutional review board of Tepecik Education and Research Hospital (2025----), and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

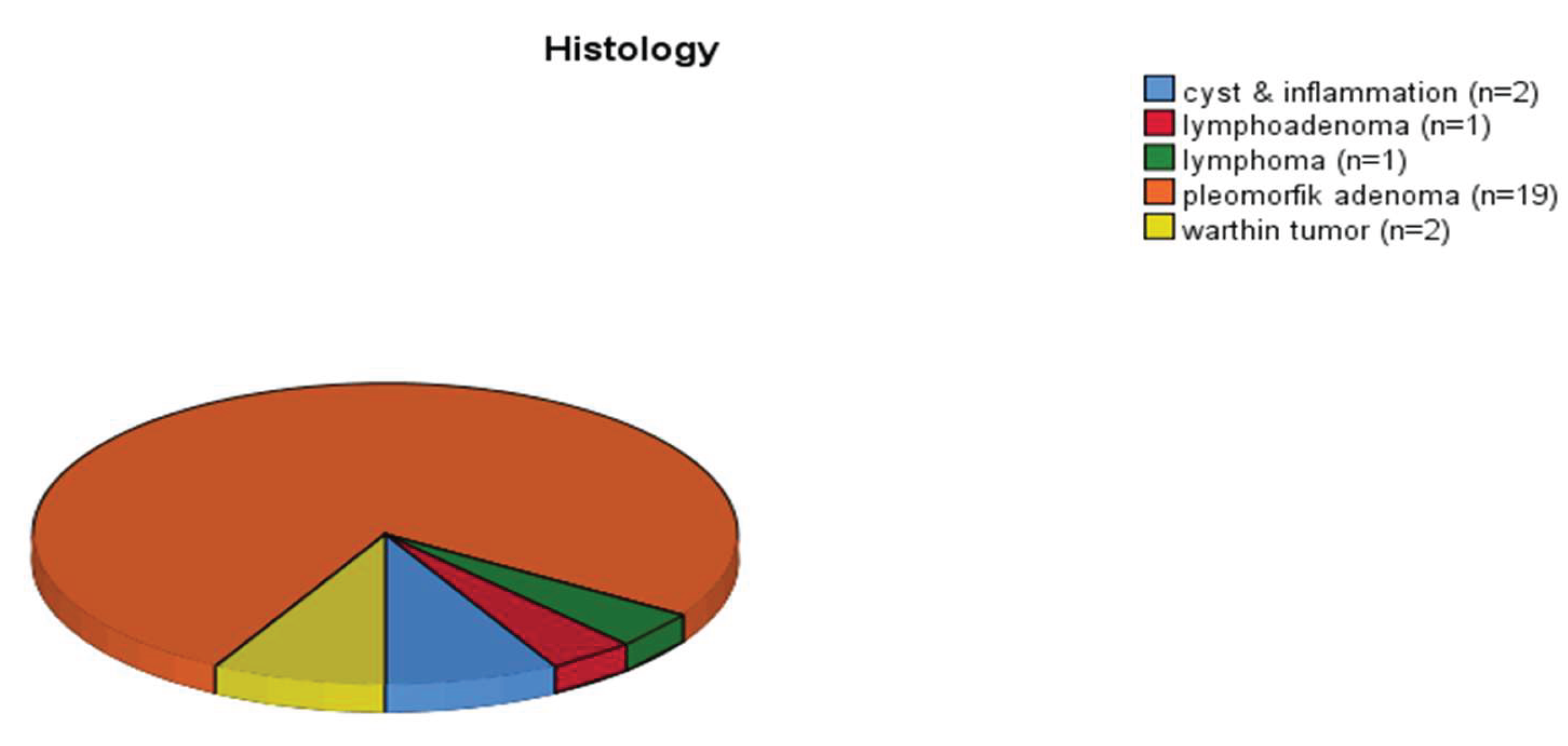

Of the 314 patients included in the study, 53% were male and 47% female, with a mean age of 55 ± 13.45 years (range: 10–88 years). The youngest patients were aged 10, 12, 12, 18, and 18, all diagnosed with pleomorphic adenoma following parotidectomy. Among patients under 35 years old (n=25), pleomorphic adenoma was the most frequently observed histological type.

Figure 1.

Pie chart illustrating the histopathological distribution of parotidectomy specimens in patients under the age of 35.

Figure 1.

Pie chart illustrating the histopathological distribution of parotidectomy specimens in patients under the age of 35.

Histopathological classification revealed that 79% of the parotid lesions were benign, 14.6% were malignant, and 6.4% were non-neoplastic. Among benign tumors, pleomorphic adenoma was the most common (n = 92), while mucoepidermoid carcinoma (n = 17; 11 low-grade, 6 high-grade) was the predominant malignant tumor. Pleomorphic adenoma, basal cell monomorphic adenoma, and low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma were more frequently observed in female patients, with female-to-male ratios of 3:2, 3:1, and 3:1, respectively. In contrast, Warthin tumor was more prevalent among males, with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1.

Postoperative facial paralysis was noted in 14 patients (4.4%), equally distributed by sex (7 males, 7 females).

The histopathological findings of parotidectomy specimens were categorized and presented in

Table 1, according to their benign, malignant, or non-neoplastic nature.

Most patients (93.3%) were born in Turkey, 5.7% were born in European countries, and 1% in Syria. Among those born in Europe, seven were from Macedonia, seven from Bulgaria, and one each from Croatia, Greece, Germany, and Montenegro. Evaluation based on place of birth showed no significant differences in tumor localization, laterality, or pathological classification (benign, malignant, non-neoplastic) (all the p values were > 0.05). (

Table 2)

The pathological diagnoses were classified into three groups: malignant, benign, and non-neoplastic, as summarized in

Table 3. There was no statistically significant difference in mean age between the malignant group and the benign (p=0.561) or non-neoplastic (p=0.193) groups. However, the mean age in the non-neoplastic group was significantly higher than that of the benign group (p=0.047). No significant differences were observed in terms of lesion laterality or sex distribution among the three groups (p=0.317 and p=0.871, respectively).

All non-neoplastic lesions were resected with clear (R0) surgical margins. In contrast, R1 resections were reported in 44.2% of malignant lesions and in 12.8% of benign lesions, a statistically significant difference (p<0.001). Among the patients with positive surgical margins (R1 resection), nine were diagnosed with mucoepidermoid carcinoma, two with adenoid cystic carcinoma, two with melanoma, two with carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, and the remaining with basal cell carcinoma, ductal-type carcinoma, epithelial carcinoma, and lymphoepithelial carcinoma (one case each). Among benign tumors with R1 resection, 20 were pleomorphic adenomas, 10 were Warthin tumors, and one was diagnosed as myoepithelioma. No R1 resections were identified in non-neoplastic lesions. Overall, the R1 resection rate in the study cohort was 16.3%.

Among the 16 benign cases showing capsular invasion, 13 were diagnosed as pleomorphic adenoma, three as Warthin tumor, and one as oncocytoma. None of these patients required additional treatment, and close clinical follow-up was scheduled. Conversely, adjuvant radiotherapy was administered to 11 patients with malignant tumors that demonstrated capsular invasion. The incidence of capsular invasion was significantly higher in malignant tumors compared to benign ones (25% vs. 7%, p<0.001).

Lymphovascular invasion was noted in a single benign tumor diagnosed as basal cell monomorphic adenoma, while perineural invasion was observed in one pleomorphic adenoma case.

Tumor necrosis was identified in 20 cases. Among these, one was observed in granulomatous inflammation of non-neoplastic parotid tissue, and another in a benign pleomorphic adenoma. Necrosis was reported in 10 malignant tumors, five of which were high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas. The remaining five consisted of adenoid cystic carcinoma, alveolar soft part sarcoma, basal cell carcinoma, ductal-type carcinoma, and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma—subtypes known for their aggressive clinical behavior. The presence of tumor necrosis was significantly more common in malignant tumors (p<0.001) and was interpreted as an indicator of their aggressive biological nature.

Facial paralysis within the first three months postoperatively was observed in 14 patients. Of these, 10 had malignant tumors and three had benign lesions. One notable case involved a 56-year-old woman with a prior history of breast cancer who underwent right parotidectomy following a fine needle aspiration biopsy suggestive of Warthin tumor. Postoperatively, she developed stage 4 facial paralysis. During lymph node dissection, 25 lymph nodes were removed, all of which were histopathologically reactive. Among patients without facial paralysis, the median number of lymph nodes removed was 0 (mean: 2.5), whereas in those with facial paralysis, the median was 17 (mean: 18). This difference was statistically significant (p<0.001).

A total of six patients underwent parotidectomy, and the pathological examination revealed only normal parotid tissue. Clinical details of these patients are summarized below:

• Patient 1: A 68-year-old male who underwent parotidectomy during evaluation of a cervical lymph node recurrence 19 months after excision of a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) from the left temporal region.

• Patient 2: A 71-year-old male who underwent parotidectomy during treatment for SCC of the right auricle.

• Patient 3: A 70-year-old female who had parotidectomy simultaneously with excision of SCC of the right external auditory canal.

• Patient 4: A 60-year-old male with two consecutive nondiagnostic FNAB of the parotid.

• Patient 5: A 45-year-old male whose FNAB was interpreted as favoring a low-grade salivary gland neoplasm.

• Patient 6: A 38-year-old female with an FNAB suggestive of pleomorphic adenoma.

Discussion

The clinical approach to parotid gland lesions fundamentally relies on distinguishing between benign and malignant tumors. However, this differentiation is often challenging based solely on clinical evaluation. Rapidly enlarging parotid masses may be attributable to inflammatory conditions such as parotitis, whereas long-standing, slow-growing swellings may suggest neoplastic processes. Although FNAC is widely used as an initial diagnostic tool, it may not always provide sufficient diagnostic accuracy. Therefore, histopathological examination remains the definitive diagnostic standard [

8].

Pleomorphic adenoma is the most frequently encountered benign parotid tumor, followed by Warthin tumor [

9,

10]. Among malignant tumors, mucoepidermoid carcinoma represents the most common subtype, although its prevalence may vary across geographic regions [

9,

11]. A cohort study from Poland reported a rising incidence of benign parotid tumors over the past decade [

12]. This increase may be attributed to improvements in diagnostic capabilities and greater public health awareness. However, no specific geographic areas within the country have been identified as having elevated risk.

Surgical excision remains the mainstay treatment for parotid masses, though radiation therapy and systemic treatments also play important roles in comprehensive disease management. Surgery is the preferred treatment even for benign lesions due to their high recurrence rates and potential for malignant transformation [

13]. Adjuvant treatments like radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy are considered when adverse pathological features—such as capsular invasion, perineural invasion, nodal metastasis, or positive margins—are present [

14,

15].

While chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy is well-supported in head and neck SCC, its role in parotid cancers is less clear and mainly extrapolated from SCC protocols. It is typically reserved for high-grade histology or metastatic disease, where systemic therapies including IO, ADCs, and TKIs are increasingly applied [

16].

Capsular invasion is not exclusive to malignancy; it can also be observed in benign parotid tumors such as Warthin tumor, basal cell adenoma, and myoepithelioma, in addition to pleomorphic adenoma. While capsular invasion is considered a risk factor for aggressive behavior in malignant tumors, it also increases recurrence risk in benign tumors. Therefore, parotid tumors exhibiting capsular invasion require more extensive surgical resection, and when such surgery is not feasible, aggressive adjuvant treatments like radiotherapy should be considered [

17,

18]. However, to our knowledge, the prevalence of capsular invasion in benign versus malignant parotid masses has not been clearly established.

Tumor necrosis represents tissue damage within the tumor and typically caused by hypoxia or dysregulated cellular and vascular processes. While necrosis is more commonly observed in malignant tumors, it can also rarely appear in benign lesions such as pleomorphic adenomas [

19]. Clinically, necrosis may be accompanied by rapid tumor growth, pain, hemorrhage, and infection. In our study, tumor necrosis was significantly more prevalent in malignant tumors (p=0.000), supporting its well-established association with aggressive tumor behavior.

Perineural invasion (PNI), an independent risk factor associated with poor survival outcomes, occurs in approximately 46% of malignant parotid tumors [

20]. The presence of PNI in parotid cancers increases both mortality and recurrence risk by approximately 3.5-fold [

21]. Although rare, PNI can occasionally be seen in benign parotid tumors.

The parotid gland contains numerous lymph nodes and contributes not only to salivary gland parenchymal function but also to lymphatic drainage of the facial region. It serves as a metastatic basin for cutaneous malignancies, such as squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma of the head and neck [

22,

23]. Parotid metastases from melanoma commonly originate from the ear, retroauricular area, cheeks, and lips, while "in-transit metastases" can be found on the temporal region, forehead, and scalp [

24].

Nodal involvement in parotid tumors dramatically reduces survival compared to node-negative cases [

25]. In this study, the mean number of lymph nodes removed was 18 in malignant cases, while benign lesions involved only a few nodes. These findings indicate the necessity for comprehensive lymph node evaluation in malignant parotid tumors with a high risk of nodal metastasis [

26]. Importantly, the risk of nodal metastasis varies significantly by histologic subtype. Tumors such as salivary duct carcinoma, high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and moderate-to-high-grade squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinomas are associated with a higher likelihood of occult nodal metastasis. Conversely, adenoid cystic carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, and low-to-moderate-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma rarely involve cervical lymph nodes [

27].

It should also be noted that even in clinically node-negative (cN0) malignant parotid tumors, postoperative nodal metastasis has been linked to poorer survival outcomes [

28]. Therefore, while comprehensive lymphadenectomy can be life-saving in selected cases, unnecessary dissection should be avoided to reduce surgical morbidity. Ultimately, the decision-making process must be individualized and based on tumor histology, patient factors, and multidisciplinary consultation.

Positive surgical margins (R1 resection) are well recognized as an adverse prognostic factor, particularly in malignant parotid tumors, where they significantly correlate with poorer survival outcomes. Morse et al. demonstrated that positive margins independently predict worse survival in parotid malignancies [

29]. Adjuvant radiotherapy administered in cases of malignant tumors with positive margins is thought to mitigate the negative impact on prognosis, consistent with findings reported by Lin et al. [

30]. However, positive margins may also occur in benign parotid tumors due to the need for meticulous dissection techniques employed to preserve the facial nerve [

31]. In these cases, positive margins typically reflect tumor fragmentation rather than true residual disease, particularly when lesions are located near critical anatomical structures. The variable intraparotid course of the facial nerve increases the technical complexity of surgery and risk of iatrogenic injury, further exacerbated by the challenges of preoperative nerve mapping [

32]. Unlike malignant tumors, the prognostic significance of positive margins in benign salivary gland tumors remains uncertain [

33]. In our study, the overall rate of positive surgical margins was approximately 16%, which may be attributable to the high proportion of benign lesions (80%) and the surgical expertise of the team. Radiotherapy was administered postoperatively in malignant cases with positive margins, aligning with standard oncologic practice.

Although long-term follow-up data on recurrence and survival were not available for all patients, the observed histopathological features—such as capsular invasion, perineural invasion, and positive surgical margins—may serve as surrogate markers to identify high-risk cases that warrant closer surveillance and potentially adjuvant therapy. These findings emphasize the necessity of a tailored surgical approach in parotid tumors, where histopathological features should inform not only the extent of resection but also the need for adjuvant therapy. Early multidisciplinary evaluation remains essential to optimize oncological control while minimizing functional morbidity.

Epidemiological data from different countries consistently demonstrate a higher prevalence of malignant parotid tumors compared to benign ones: 69% vs. 31% in Turkey, 73% vs. 27% in India, and 71% vs. 29% in the USA [34-36]. These findings emphasize the predominance of malignancies within parotid gland neoplasms globally. The relatively close percentages across countries indicate a consistent global pattern, suggesting that geographical or ethnic differences may have limited influence on the overall malignancy rate in parotid tumors.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature may have introduced selection bias, particularly regarding the indication for surgery and the completeness of histopathological records. Second, the single-center design limits the generalizability of our findings to broader populations with different demographic or healthcare characteristics. Additionally, long-term follow-up data on recurrence and survival were not uniformly available for all patients, which may affect the accuracy of outcome measures and limits the ability to correlate histopathological risk factors with actual oncologic endpoints. Future prospective, multicenter studies with standardized protocols are necessary to validate these observations and refine treatment strategies.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of patients undergoing parotidectomy. The majority of cases were benign, with pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin tumor being the most common. Malignant tumors made up 14.6% of cases and showed more aggressive features such as higher rates of positive surgical margins, capsular invasion, and tumor necrosis.

Younger patients often had pleomorphic adenoma, while Warthin tumors were more common in men. Facial paralysis after surgery was more frequent in patients with malignant tumors and those who had extensive lymph node dissection. There were no significant differences in tumor features based on place of birth, suggesting that geographical factors had little impact on pathology.

Taken together, these findings support the implementation of risk-adapted follow-up strategies, where histopathological features such as tumor necrosis, perineural invasion, and capsular invasion guide the intensity and frequency of postoperative surveillance. This underscores the importance of thorough preoperative assessment and individualized surgical planning, particularly in cases with suspected malignancy.

Acknowledge

We thank the ethics committee of Tepecik Eduvation and Research Hospital for the approval of the study protocol and all other doctors of Medical Oncology and Head and Neck Department

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and O.Y.A.; methodology, S.A.; software, S.A.; validation, U.K., I.B.A. and I.C.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation, S.A.; resources, V.S.; data curation, S,A and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, I.C, O.U.U.; visualization, U.K.; supervision, O.U.U.; project administration, S.A. and O.Y.A; funding acquisition, no. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research has no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Tepecik Education and Research Hospital (protocol code is 2024/06-02 and date of approval is 02.07.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective design of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional privacy regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lewis AG, Tong T, Maghami E. Diagnosis and management of malignant salivary gland tumors of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49(2):343–380.

- Shah JP, Patel SG, Singh B. Jatin Shah's Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology e-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012.

- Chan WH, Lee KW, Chiang FY, et al. Features of parotid gland diseases and surgical results in Southern Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2010;26:483–492. [CrossRef]

- Ho K, Lin H, Ann DK, Chu PG, Yen Y. An overview of the rare parotid gland cancer. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3:40. [CrossRef]

- Carlson ER, Webb DE. The diagnosis and management of parotid disease. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2013;25(1):31–48. [CrossRef]

- Maahs GS, Oppermann Pde O, Maahs LG, Machado Filho G, Ronchi AD. Parotid gland tumors: a retrospective study of 154 patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81(3):301–306. [CrossRef]

- Bussu F, Parrilla C, Rizzo D, Almadori G, Paludetti G, Galli J. Clinical approach and treatment of benign and malignant parotid masses, personal experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:135–143.

- Mezei T, Mocan S, Ormenisan A, Baróti B, Iacob A. The value of fine needle aspiration cytology in the clinical management of rare salivary gland tumors. J Appl Oral Sci. 2018;26:e20170267. [CrossRef]

- Thielker J, Grosheva M, Ihrler S, Wittig A, Guntinas-Lichius O. Contemporary management of benign and malignant parotid tumors. Front Surg. 2018;5:39. [CrossRef]

- Valstar MH, de Ridder M, van den Broek EC, et al. Salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma in the Netherlands: a nationwide observational study. Oral Oncol. 2017;66:93–99. [CrossRef]

- Xiao CC, Zhan KY, White-Gilbertson SJ, Day TA. Predictors of nodal metastasis in parotid malignancies: a national cancer data base study of 22,653 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(1):121–130. [CrossRef]

- Szymańska I, Szymański J, Sitarz R. The Epidemiology of Salivary Glands Pathologies in Adult Population over 10 Years in Poland—Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10247.

- Larian, B. Parotidectomy for Benign Parotid Tumors. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016 Apr;49(2):395-413. [CrossRef]

- Byrd S, Morris LGT. Neck dissection for salivary gland malignancies. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;29(3):157-161. [CrossRef]

- Ali S, Palmer FL, Yu C, et al. A predictive nomogram for recurrence of carcinoma of the major salivary glands. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 Jul;139(7):698-705.

- Steuer CE, Hanna GJ, Viswanathan K, et al. The evolving landscape of salivary gland tumors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(6):597-619. [CrossRef]

- Choi SY, Choi J, Hwang I, et al. Comparative longitudinal analysis of malignant transformation in pleomorphic adenoma and recurrent pleomorphic adenoma. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):1808. [CrossRef]

- Dulguerov P, Todic J, Pusztaszeri M, Alotaibi NH. Why do parotid pleomorphic adenomas recur? A systematic review of pathological and surgical variables. Front Surg. 2017;4:26. [CrossRef]

- Allen CM, Damm D, Neville B, et al. Necrosis in benign salivary gland neoplasms. Not necessarily a sign of malignant transformation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78(4):455-461. [CrossRef]

- Huyett P, Duvvuri U, Ferris RL, et al. Perineural invasion in parotid gland malignancies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(6):1035-1041.

- Kazemian E, Solinski M, Adams W, Moore M, Thorpe EJ. The role of perineural invasion in parotid malignancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2022;130:105937. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, PJ. Parotid lymph nodes in primary malignant salivary lymph nodes. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;30:99-106. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. The parotid gland as a metastatic basin for cutaneous cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;131:551-553. [CrossRef]

- Brougham NDLS, Dennett ER, Cameron R, Tan ST. The incidence of metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of its risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:811-815. [CrossRef]

- Erovic BM, Shah MD, Bruch G, et al. Outcome analysis of 215 patients with parotid gland tumors: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;44:43. [CrossRef]

- Voora RS, Panuganti B, Califano J, et al. Patterns of lymph node metastasis in parotid cancer and implications for extent of neck dissection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(5):1067-1078. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Yi S, An PG, et al. Patterns of lymph node metastasis and treatment outcomes of parotid gland malignancies. BMC Oral Health. 2025;25:286. [CrossRef]

- Chang L, Wang Y, Wang Z, et al. Number of positive lymph nodes affects oncologic outcomes in cN0 mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the major salivary gland. Sci Rep. 2024;14:9086. [CrossRef]

- Morse E, Fujiwara RJT, Judson B, Prasad ML, Mehra S. Positive surgical margins in parotid malignancies: institutional variation and survival association. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(1):129–137. [CrossRef]

- Lin YC, Chen KC, Lin CH, Kuo KT, Ko JY, Hong RL. Clinicopathological features of salivary and non-salivary adenoid cystic carcinomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(3):354–360.

- Witt, RL. The significance of the margin in parotid surgery for pleomorphic adenoma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(12):2141–2154. [CrossRef]

- El Sayed Ahmad Y, Winters R. Parotidectomy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed]

- Piwowarczyk K, Bartkowiak E, Kosikowski P, Chou JT, Wierzbicka M. Salivary gland pleomorphic adenomas presenting with extremely varied clinical courses: a single institution case-control study. Front Oncol. 2021;10:600707. [CrossRef]

- Kızıl Y, Aydil U, Ekinci O, et al. Salivary gland tumors in Turkey: demographic features and histopathological distribution of 510 patients. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65(Suppl 1):112–120. [CrossRef]

- Ramdass MJ, Maharaj K, Mooteeram J, et al. Parotid gland tumours in a West Indian population: comparison to world trends. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3(1):167–170. [CrossRef]

- Deschler DG, Kozin ED, Kanumuri V, et al. Single-surgeon parotidectomy outcomes in an academic center experience during a 15-year period. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1096–1103. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).