1. Introduction

Volatility modelling has been the focus in financial econometrics due to its importance for asset pricing, portfolio decisions, and financial stability. Financial series tend to exhibit stylised features such as volatility clustering, fat tails, and asymmetric shocks (

Bollerslev 1986;

Engle 1982;

Nelson 1991). Historical models such as Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH) and Generalised Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH) have been highly useful, but their restrictive assumptions prevent them from fully capturing the richness of return distributions. Developments such as Exponential GARCH (EGARCH) by

Nelson (

1991) and Glosten, Jagannathan & Runkle GARCH (GJR-GARCH) by

Glosten et al. (

1993) addressed asymmetries more effectively, and even multivariate GARCH forms have been introduced (

Bauwens et al. 2006). Emerging markets are generally characterised by higher volatility because of greater exposure to macroeconomic disturbances, institutional uncertainties, and fluctuations in global capital flows. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), being the largest stock market in Africa, offers an important setting for examining such dynamics. In particular, the JSE Top40 Index reflects the most liquid and capitalised businesses and hence serves as a benchmark for local and foreign investors (

Jefferis & Smith 2005). Modelling its volatility is therefore crucial for policy, risk management, and investment. Recent developments in machine learning have delivered alternatives to conventional econometric approaches. eXtreme Gadient Boosting (XGBoost) (

Chen & Guestrin 2016) is a robust gradient boosting method that has become very popular, and combination models of GARCH with XGBoost have been shown to improve the accuracy of short-term predictions (

Maingo et al. 2025). However, these hybrids often lack interpretability, limiting their utility in regulatory applications.

Creal et al. (

2013) proposed a promising alternative with the Generalised Autoregressive Score (GAS) model, which was later extended by

Harvey (

2013). GAS models learn parameters by iterating through the score of the conditional likelihood, making them highly sensitive to fresh data.

Empirical evidence indicates that the GAS models outperform conventional GARCH in density forecasting and risk measurement, particularly under heavy-tailed or asymmetric distributions (

Lazar & Xue 2020). Building on these theoretical results,

Ardia et al. (

2019) built the R package GAS that provides practical implementation tools and demonstrated its application using examples to financial asset returns, confirming the ability of the framework to model time-varying conditional densities. Implementations in African markets augment this affirmation further. For instance,

Babatunde et al. (

2021) compared GARCH and GAS models in the forecasting of daily stock prices on the Nigerian Stock Exchange and found that GAS under the Student-t as well as skewed Student-t distributions outperformed GARCH in volatility forecasting but that EGARCH was good under certain distributional assumptions. In parallel,

Yaya et al. (

2016) analysed the Nigerian All Share Index and showed that GAS-type models, including Beta-t-EGARCH, provided a superior explanation of jumps, outliers, and asymmetry relative to traditional GARCH models. Collectively, these papers show that GAS-based models provide better density forecasts and tail risk estimation than traditional GARCH, but their application to emerging markets remains relatively rare, and comparison studies with hybrid econometric and machine learning models remain scarce.

The study gap motivating the present work is that, while volatility modelling in South Africa has been heavily studied by using GARCH-type models (

Venter & Mare 2020;

Maingo et al. 2025), the Generalised Autoregressive Score (GAS) framework has received little attention, and very few studies have comparatively assessed its performance with hybrid econometric–machine learning methodologies such as GARCH–XGBoost. To address this gap, the present study employs the GAS framework to estimate and forecast the volatility of the JSE Top40 Index and compares its result with GARCH and ARMA–EGARCH–XGBoost models. The article makes four significant contributions to the literature. First, it offers one of the first comprehensive uses of GAS in South African equity markets, thereby extending its use to an important emerging market. First, it undertakes systematic benchmarking of GAS with respect to both standard econometric and hybrid machine learning approaches, yielding comparative results into the relative performance of the latter two. Second, it shows that GAS is superior in density calibration and tail risk prediction, whereas hybrid models exhibit superior performance in short-horizon point prediction. Finally, through simulation tests, the paper emphasises the central role played by heavy-tailed distributions in modelling South African equities’ extreme return dynamics. In total, these contributions enrich volatility modelling literature and provide recommendations for practitioners, such as investors, regulators, and policymakers who wish to pursue risk management in the emerging market setting.

4. Discussion

The empirical results in

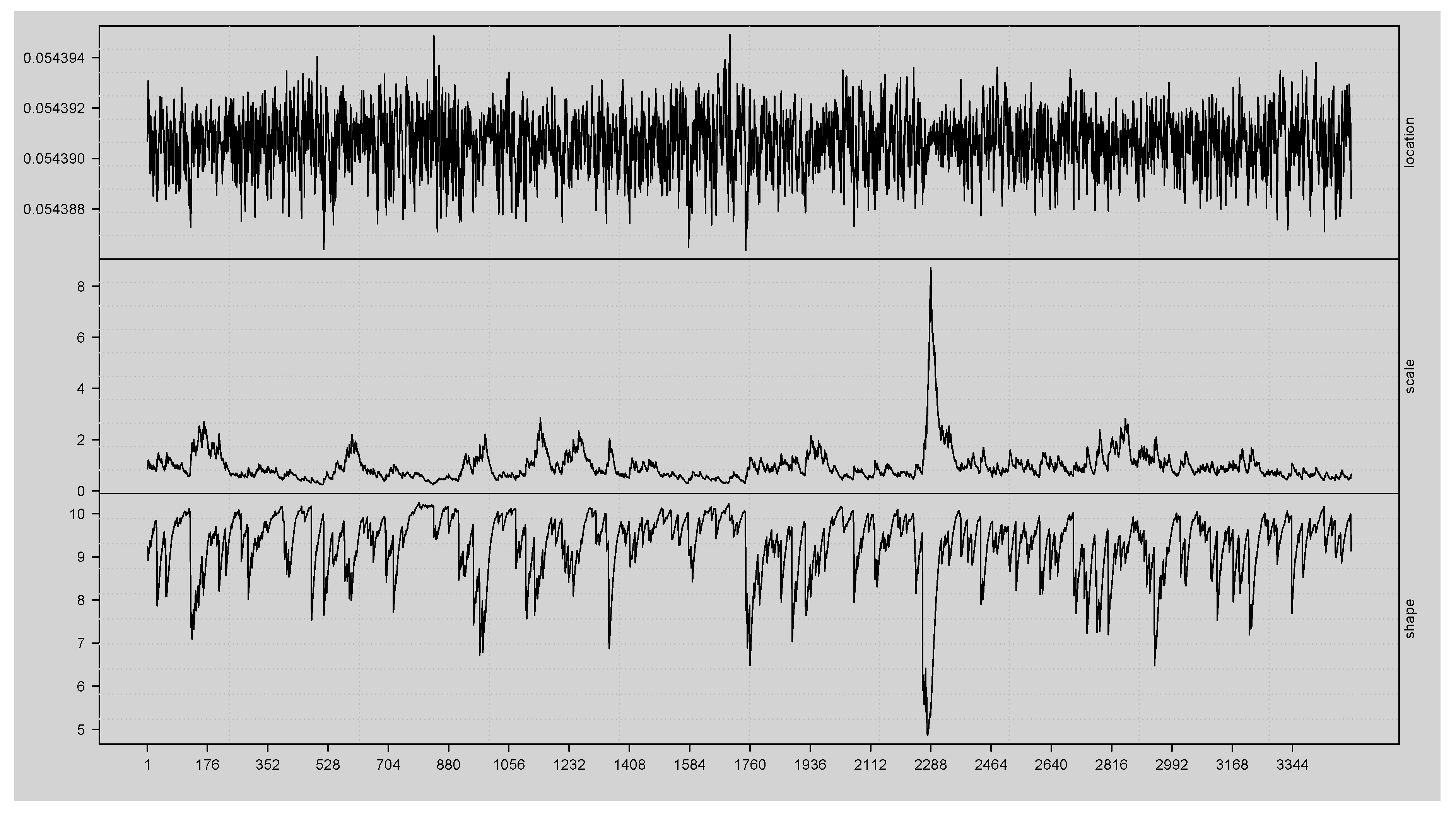

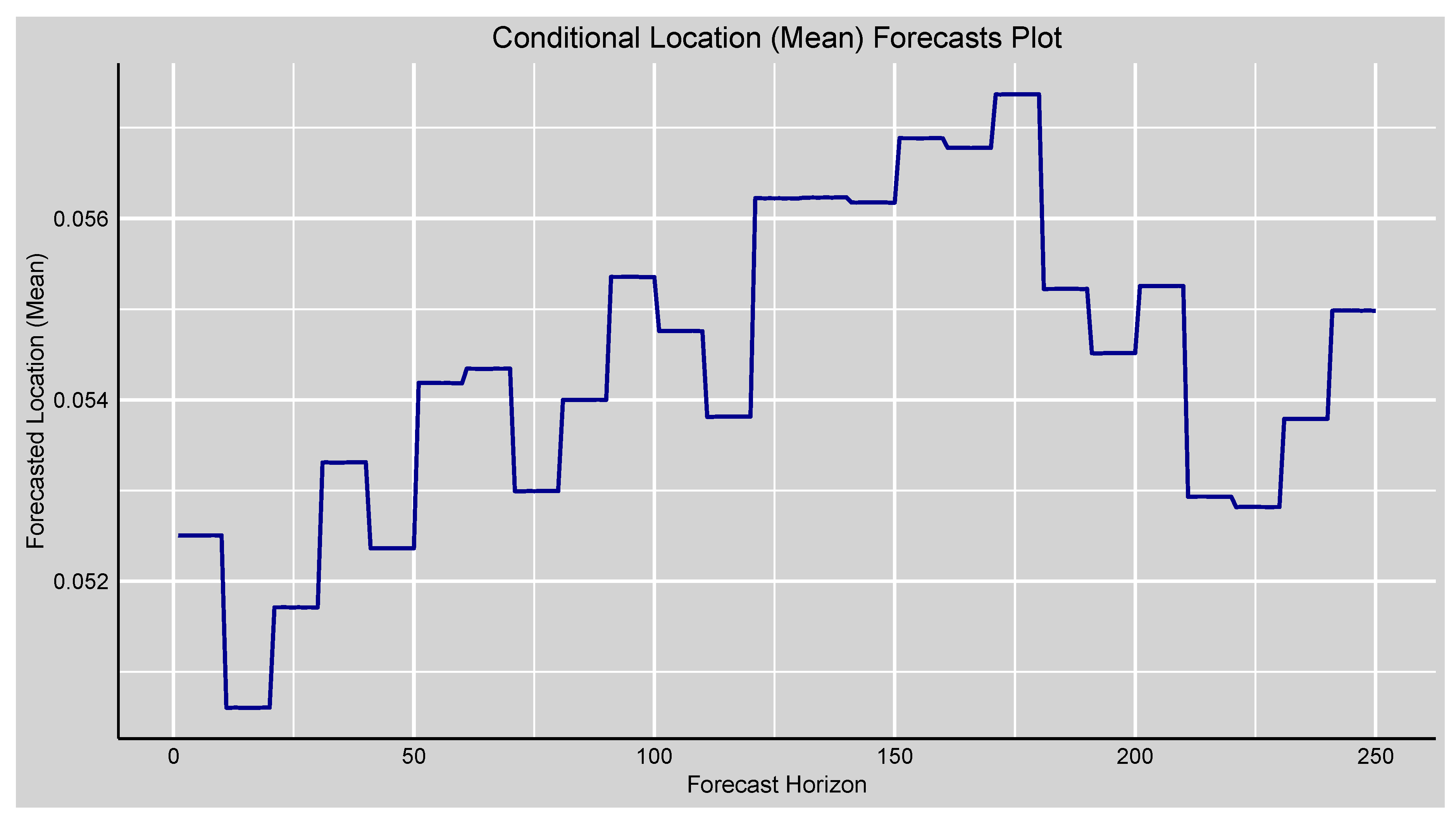

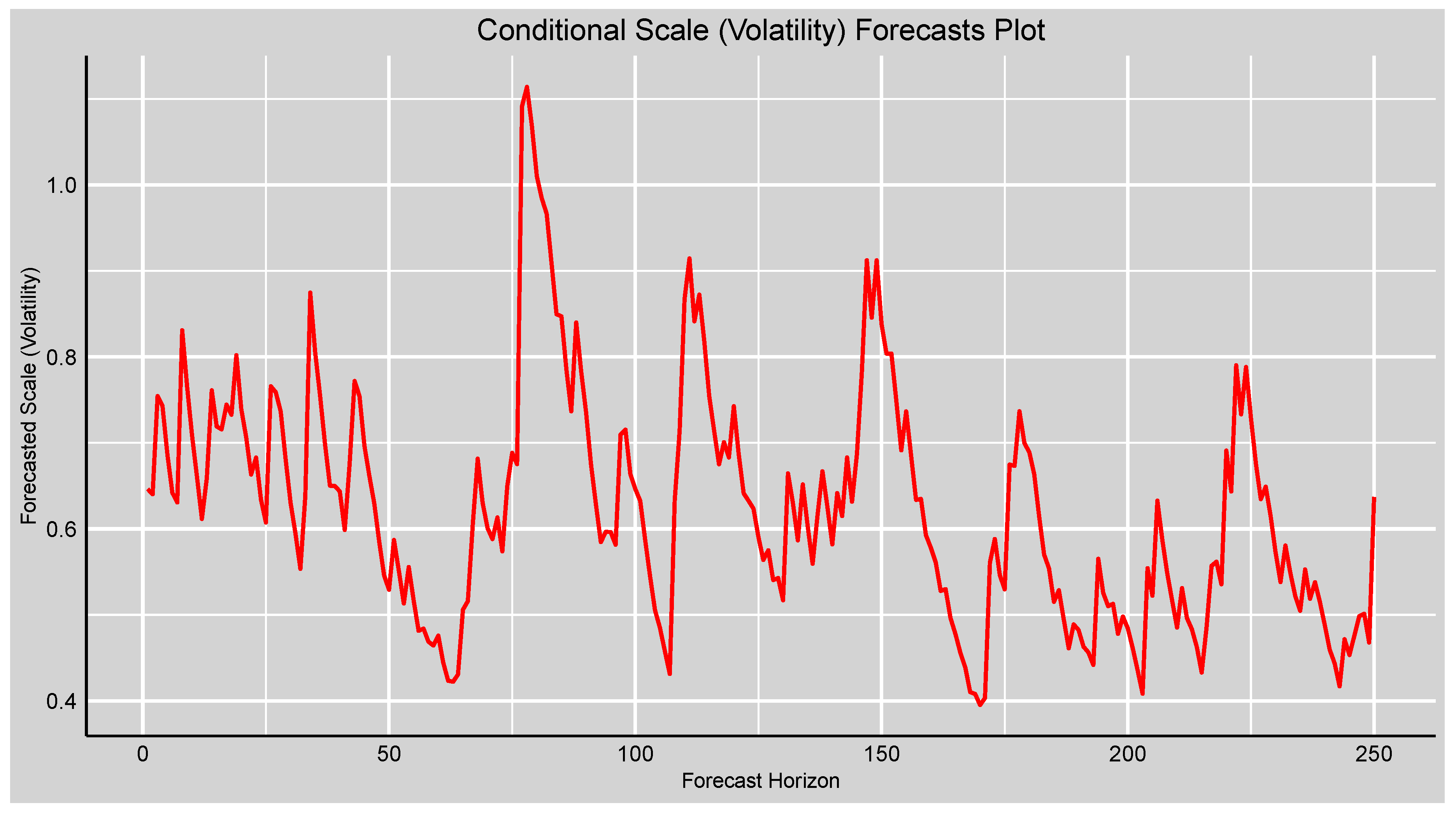

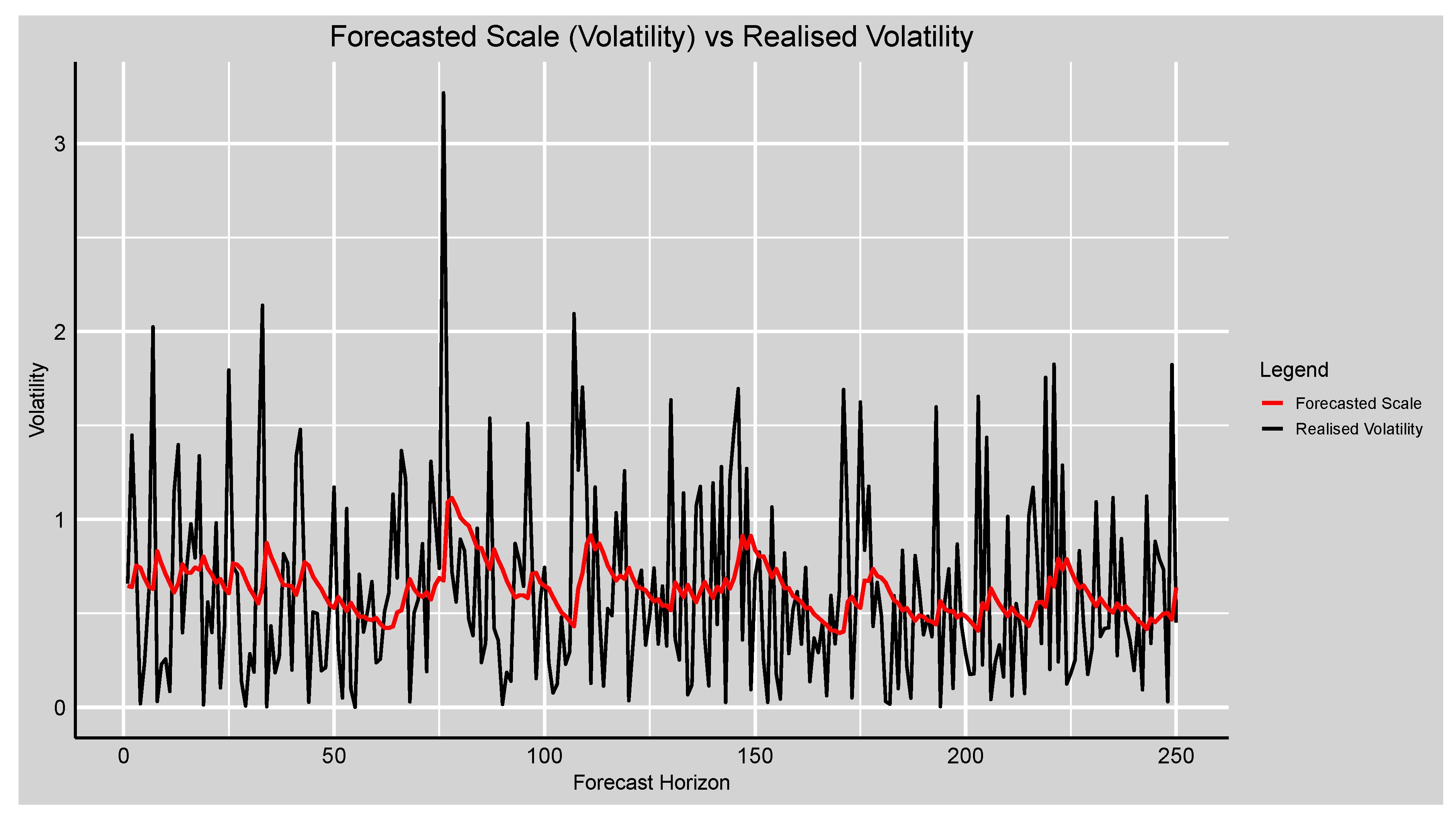

Section 3 demonstrate that the Student-t distribution of the GAS model (GAS-STD) provides the best fit for the JSE Top40 Index returns among the conditional distributions considered.

Table 1 comparison measures show that the GAS-STD produces the lowest AIC (10188.142) and BIC (10243.626) values, which means that it maximises goodness-of-fit and parsimony compared to the Gaussian, skew-Gaussian, or asymmetric forms. The parameter estimates also detect considerable persistence of location and scale dynamics with coefficients

and

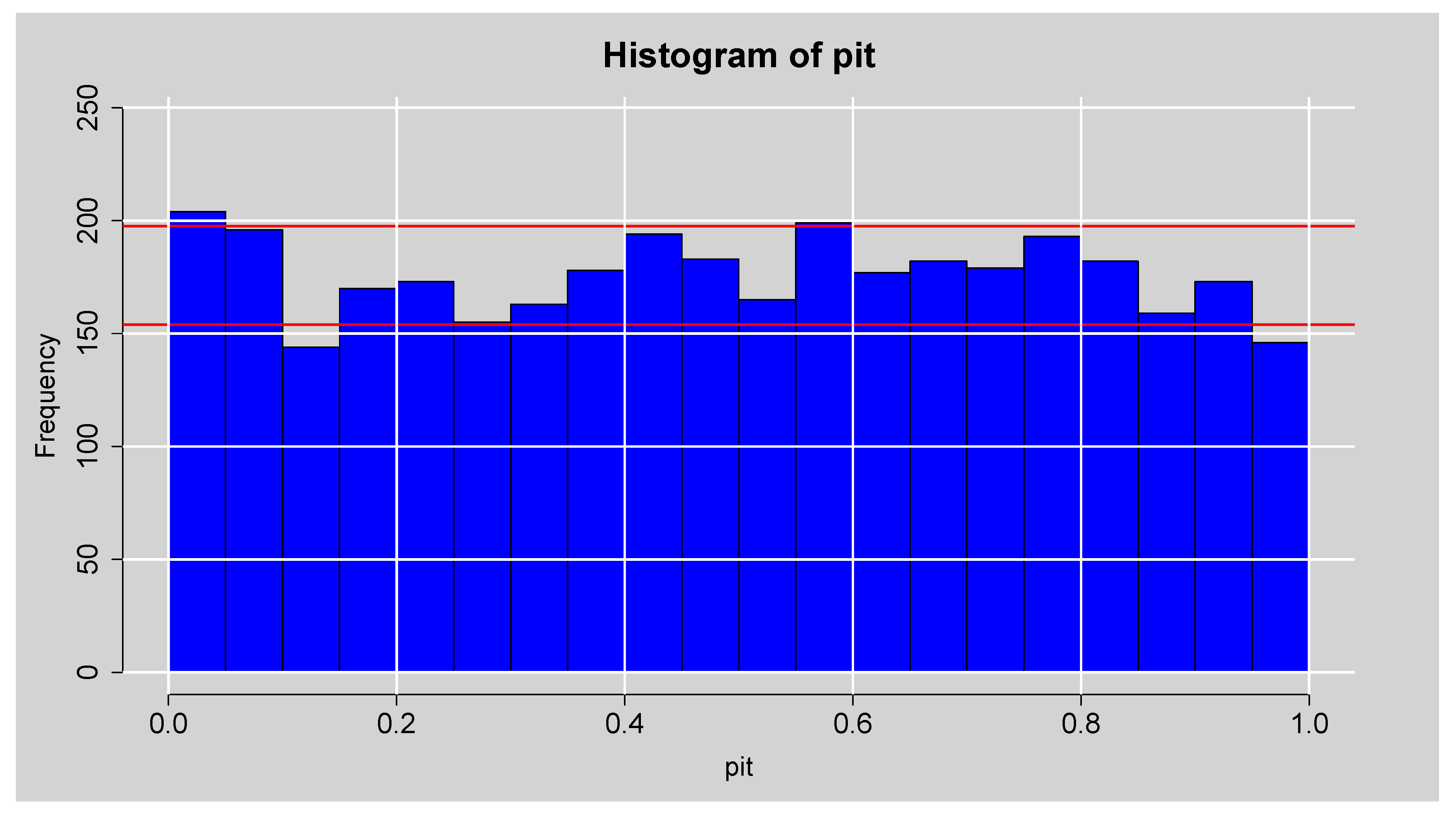

statistically significant at 1%. This confirms that past volatility has a strong effect on current volatility, a common feature of financial return series. The findings of the shape parameter are that the return distribution is time-varying in terms of tail heaviness and that there are indications of episodes of extreme kurtosis during times of market distress. A diagnostic examination of the estimated GAS-STD model also confirms that it is a density forecast. Both the PIT histogram in

Figure 1 and the uniform scores in

Table 3 indicate that the model produces well-calibrated predictive densities, although skewness tests do identify an unexplained residual asymmetry. Consequently, density backtests such as Normalised Log Score (1.1932) and uniform PIT score (0.4417) in

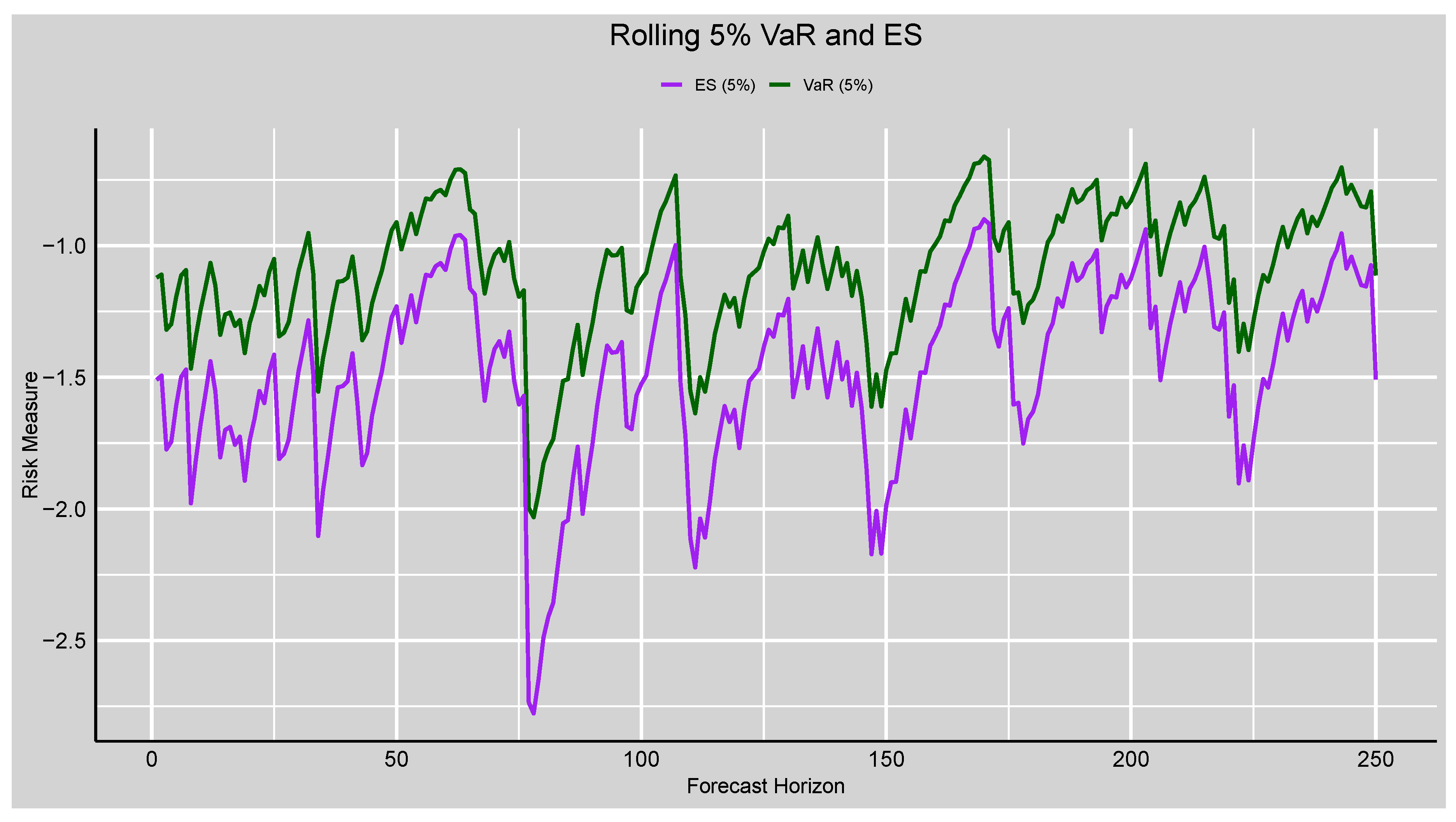

Table 3 attain good forecast accuracy through balanced performance in the centre and tails of the distribution. Forecasting evaluation further indicates that GAS-STD outperforms in the capture of volatility dynamics over mean returns. Rolling forecasts show the conditionalonal mean is generally level, such as in the martingalethe martingale property of asset returns, while forecast volatility shows clear clustering that tracks very closely with realised volatility. Accuracy measures for the forecasts verify that RMSE (0.5373) for volatility forecast is substantially lower than for mean return levels (which is 0.8055). These findings underscore that the GAS model works best when the modelling objective is forecasting volatility rather than mean returns prediction. Risk management analysis incorporating Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES) concludes that the GAS-STD yields plausible downside risk estimates. Both 5% VaR and ES forecasts dynamically adapt to clusters of volatility, and backtests confirm good performance: the Kupiec test for unconditional coverage (

) and the Christoffersen test for conditional coverage (

) fail to reject good coverage, and the Dynamic Quantile test (

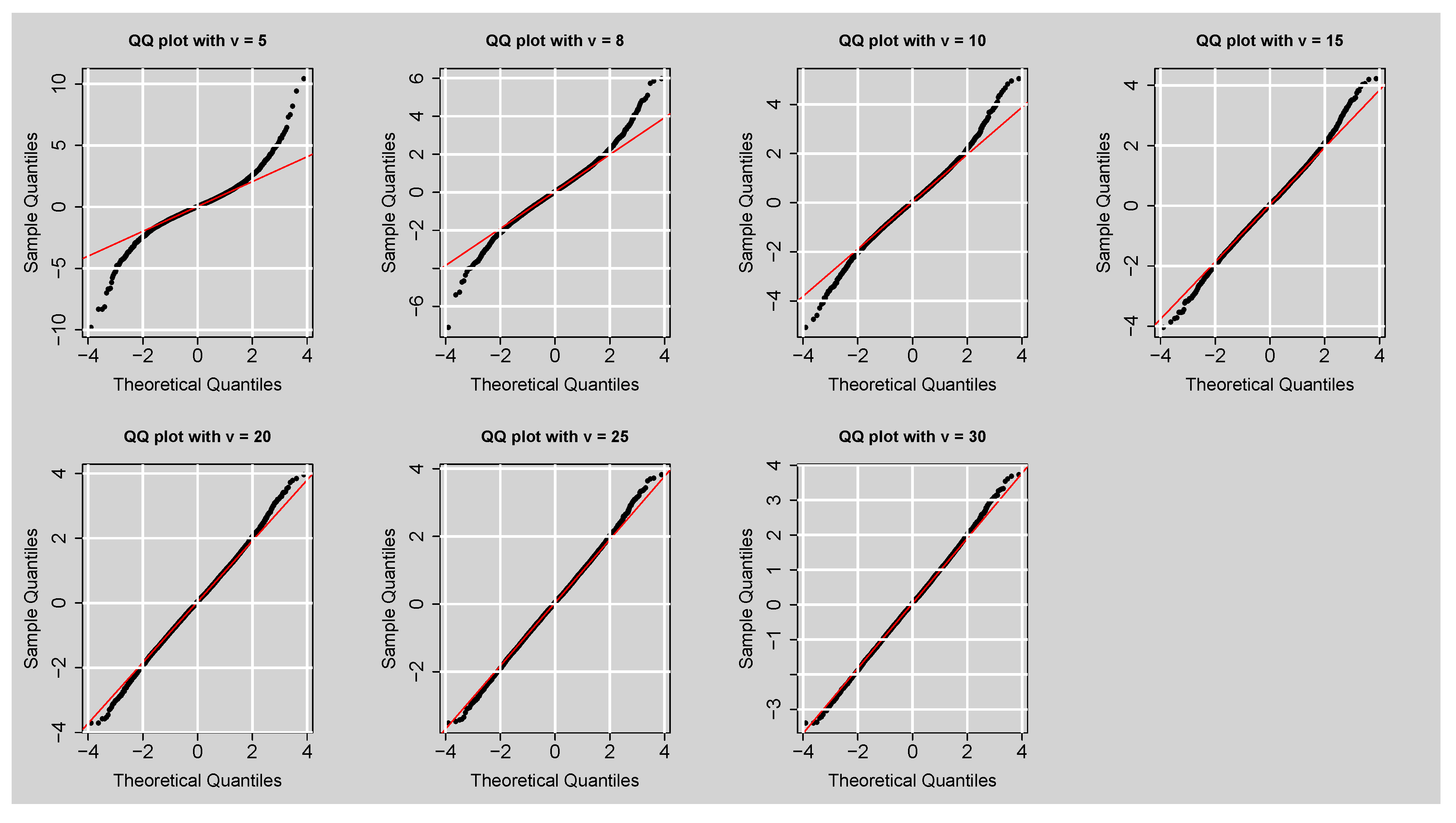

) further confirms good dynamic exceedance behaviour. Such findings demonstrate the GAS-STD to be an effective method of quantifying tail risk in equity indices. These are supported by simulation studies in demonstrating the impact of the shape parameter

on tail behaviour. Small values of

(

) yield levels of kurtosis greater than 7 that characterise heavy tails, whereas larger ones (

) converge towards the Gaussian benchmark point. This is the kind of behaviour that captures the leptokurtic nature of financial returns, an essential requirement when modelling extreme risk. Comparison with other models, however, shows that although GAS-STD is superior in density and risk forecasting, hybrid mpdel that include machine learning surpass it in point forecast accuracy. The ARMA(3,2)–EGARCH(1,1)–XGBoost model has much lower RMSE (0.1386) than GAS-STD, and DM tests in

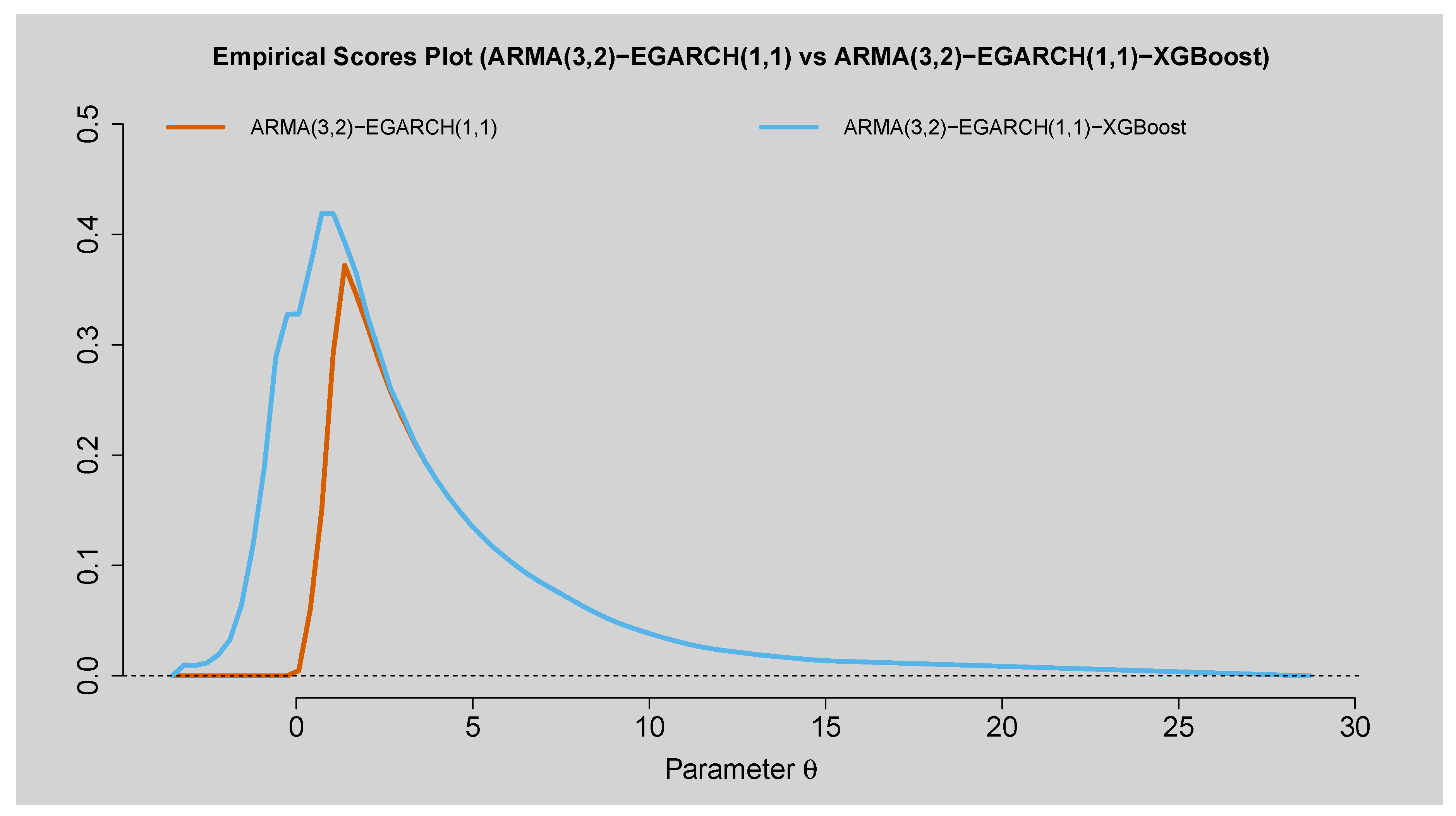

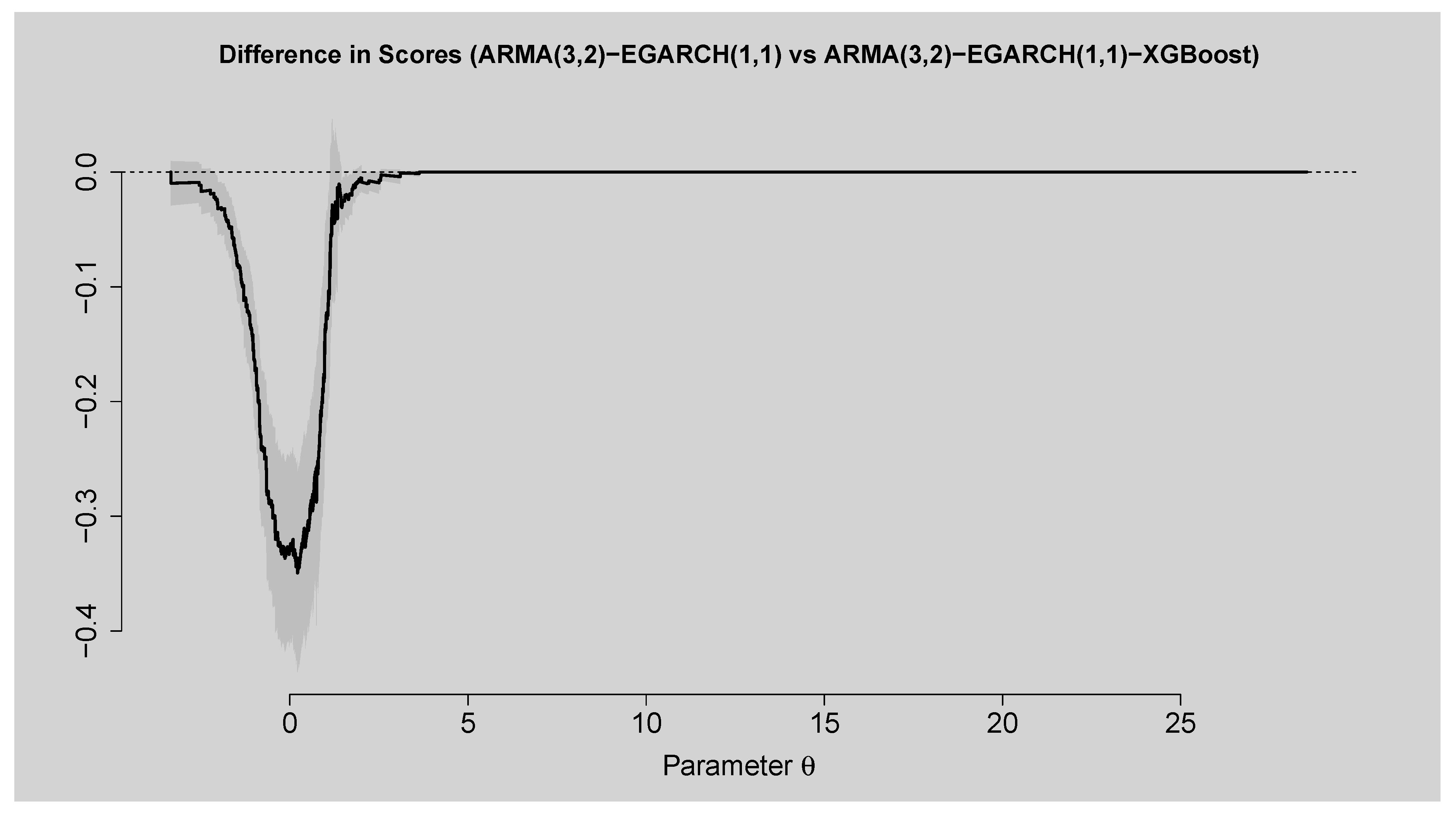

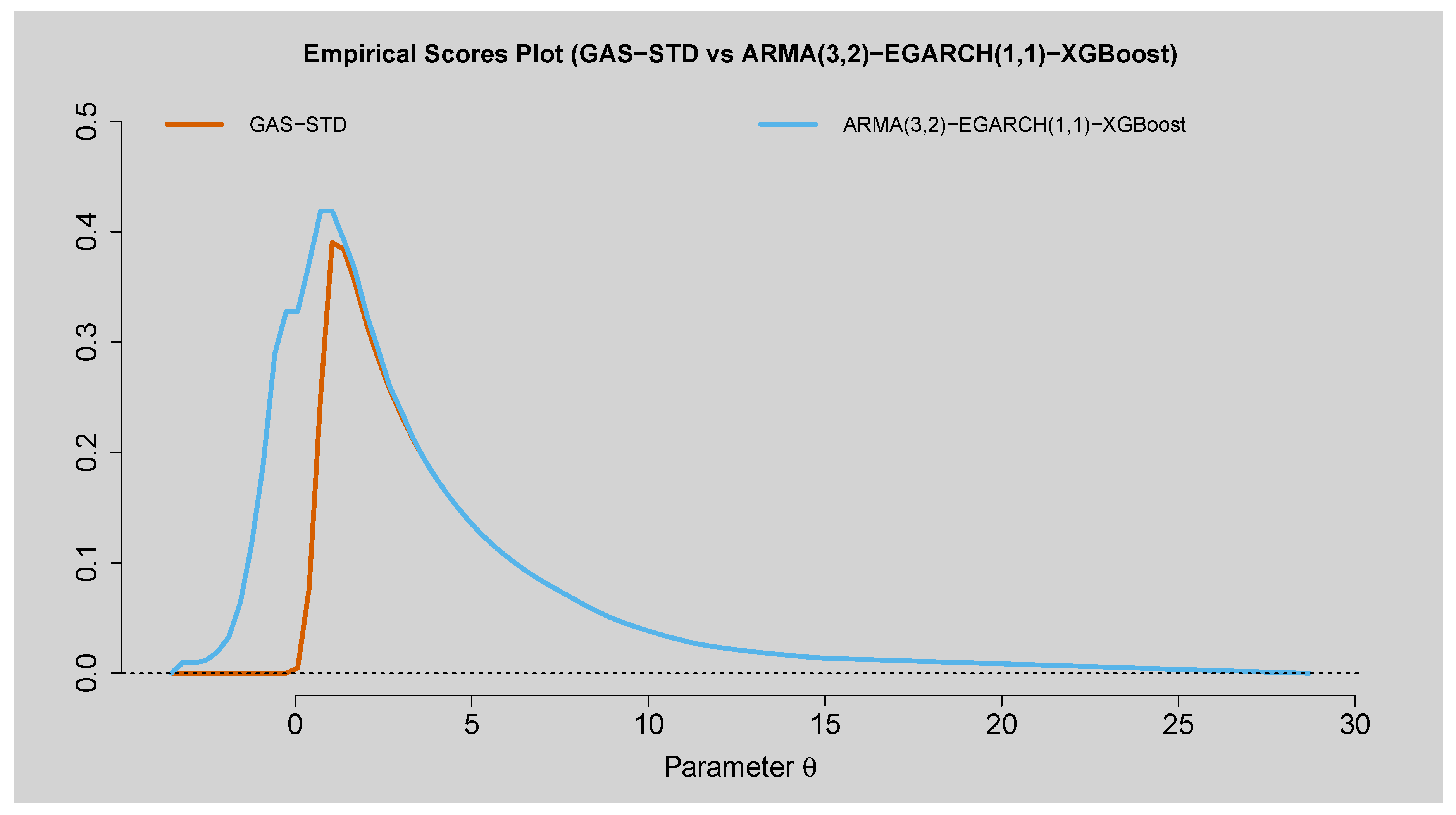

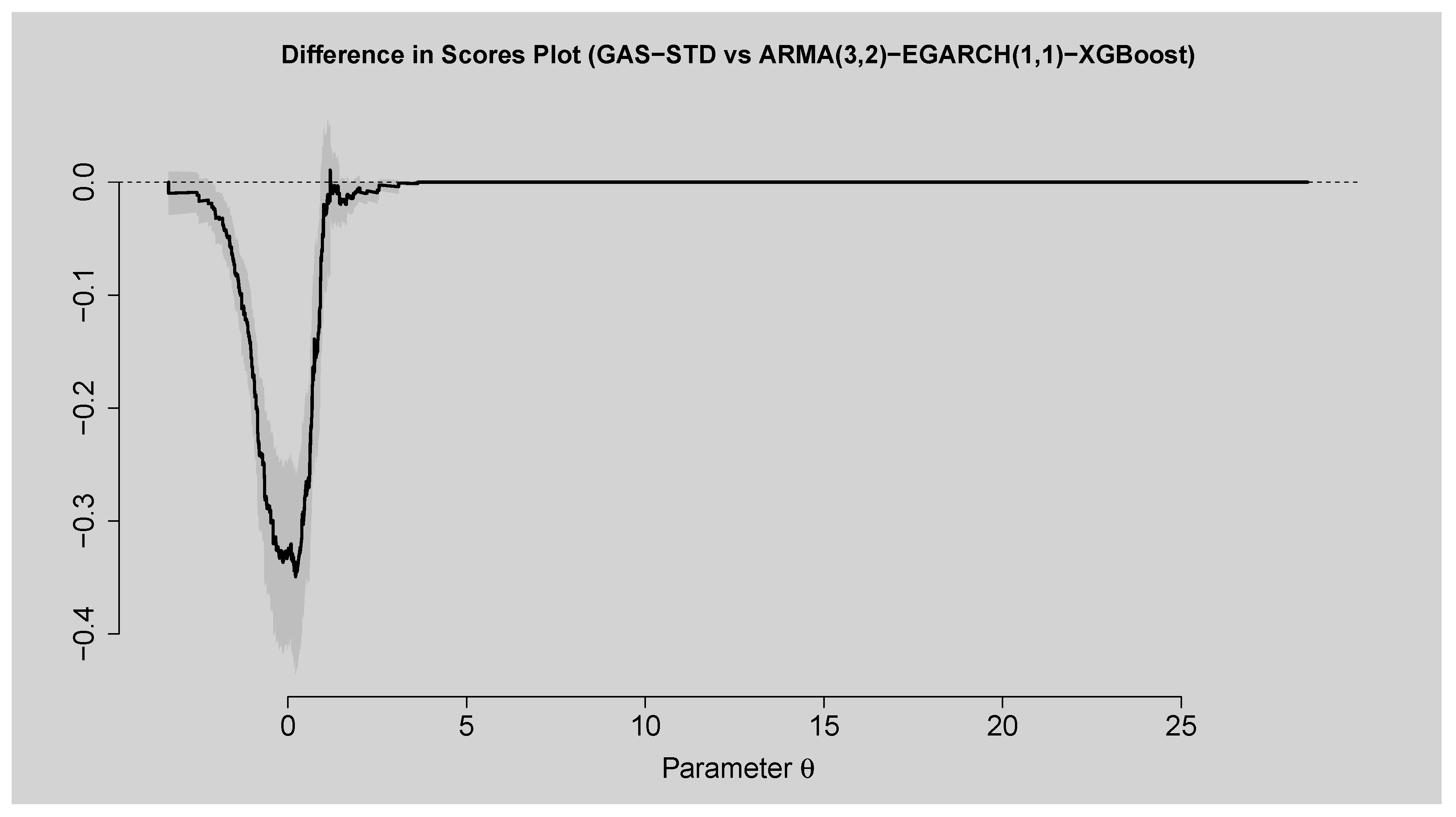

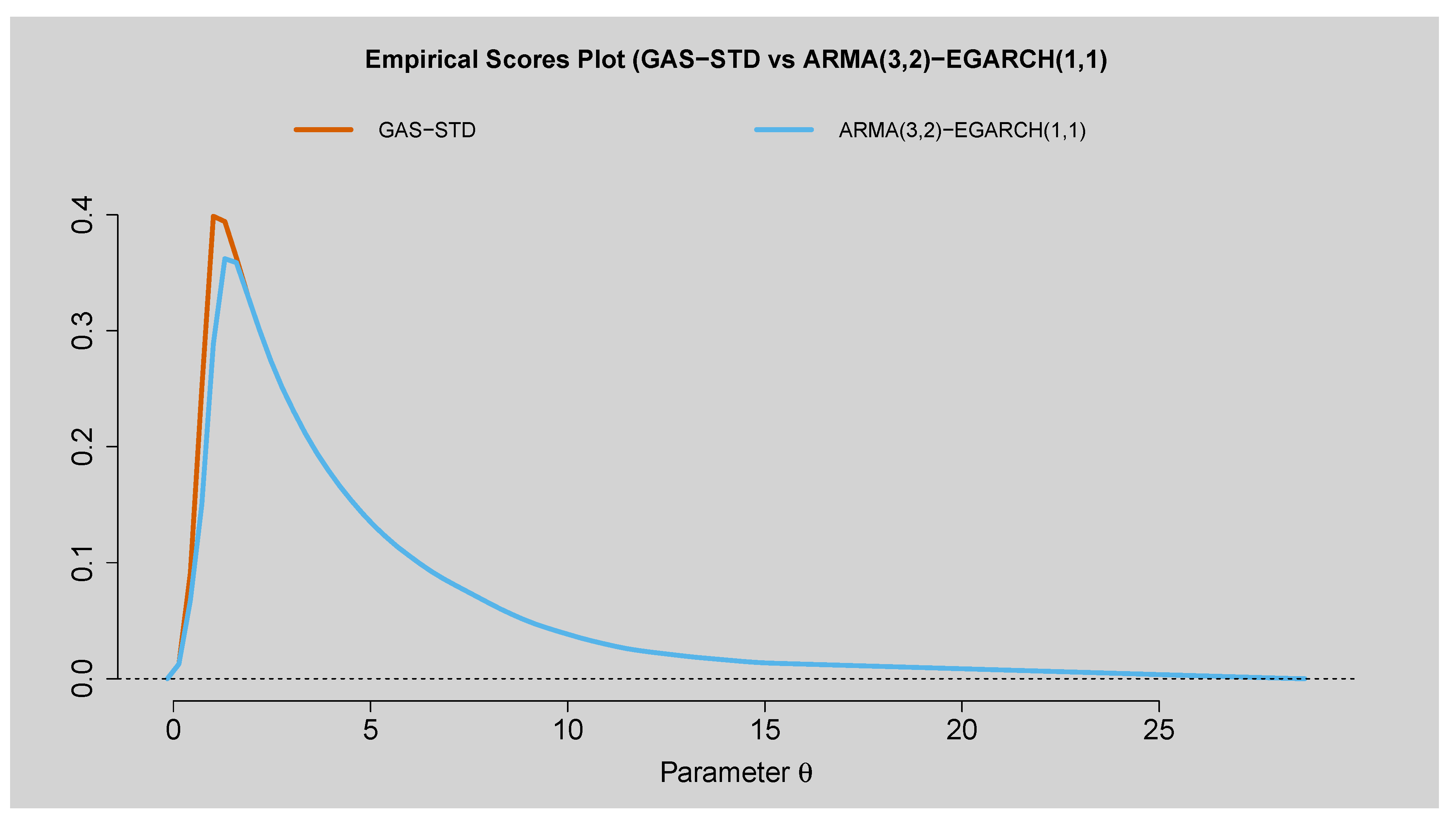

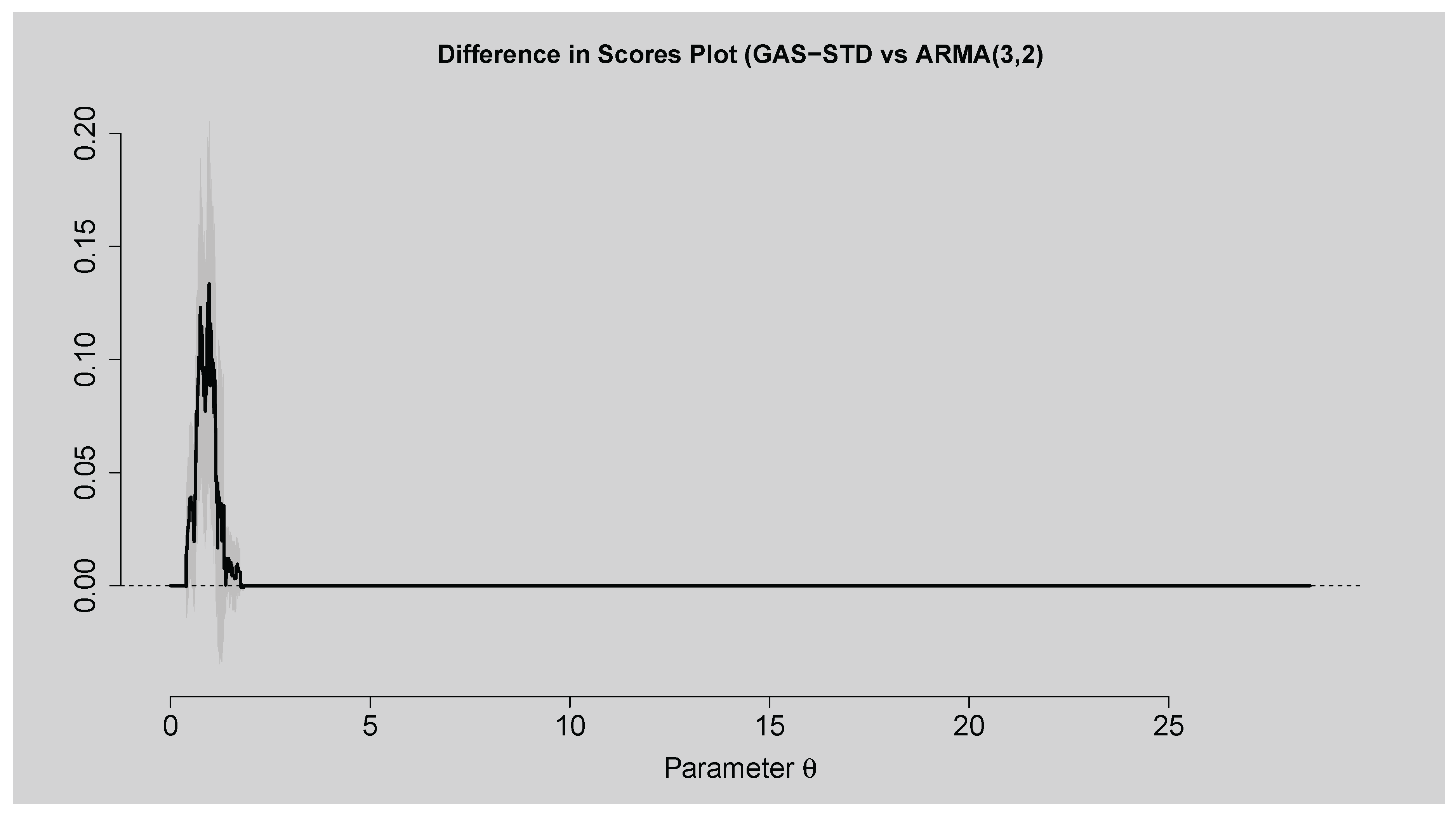

Table 11 confirm that the hybrid forecasts are better. Murphy diagrams in

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 15, and

Figure 16 also show that the hybrid model surpasses GAS-STD and standalone ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) at all forecast horizons. These results highlight that model choice depends on the purpose of forecasting: GAS-STD for risk measures and density, and hybrid model for short-horizon volatility forecasts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; methodology, I.M.; software, I.M.; validation, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; formal analysis, I.M.; investigation, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; data curation, I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.; writing—review and editing, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; visualization, I.M.; supervision, T.R. and C.S.; project administration, T.R. and C.S.; funding acquisition, I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Histogram plot of the PIT.

Figure 1.

Histogram plot of the PIT.

Figure 2.

Time-varying parameter estimates of the fitted univariate GAS model with STD, showing the evolution of the conditional location, scale, and shape parameters.

Figure 2.

Time-varying parameter estimates of the fitted univariate GAS model with STD, showing the evolution of the conditional location, scale, and shape parameters.

Figure 3.

Forecasts plot of the forecasted conditional location (mean) of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Figure 3.

Forecasts plot of the forecasted conditional location (mean) of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Figure 4.

Forecasts plot of the forecasted conditional scale (volatility) of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Figure 4.

Forecasts plot of the forecasted conditional scale (volatility) of the fitted GAS-STD model.

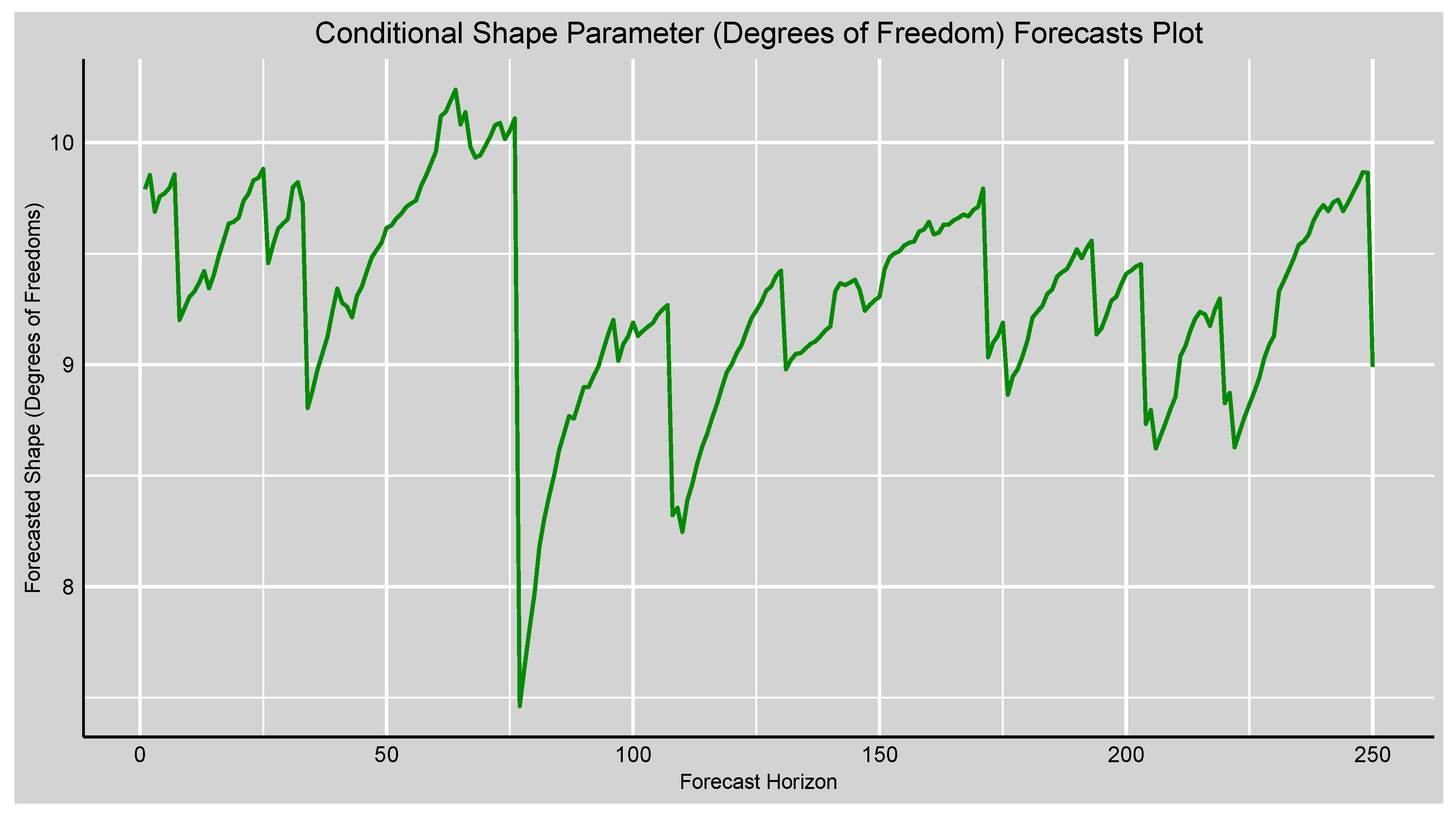

Figure 5.

Forecasts plot of the forecasted conditional scale (volatility) of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Figure 5.

Forecasts plot of the forecasted conditional scale (volatility) of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Figure 6.

Plot of the forecasted conditional scale (volatility) versus realised volatility of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Figure 6.

Plot of the forecasted conditional scale (volatility) versus realised volatility of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Figure 7.

Rolling Risk Forecasts plot from the 5% VaR and ES.

Figure 7.

Rolling Risk Forecasts plot from the 5% VaR and ES.

Figure 8.

QQ plots of simulated data from the GAS-STD model under fixed shape parameter or degrees of freedom values ().

Figure 8.

QQ plots of simulated data from the GAS-STD model under fixed shape parameter or degrees of freedom values ().

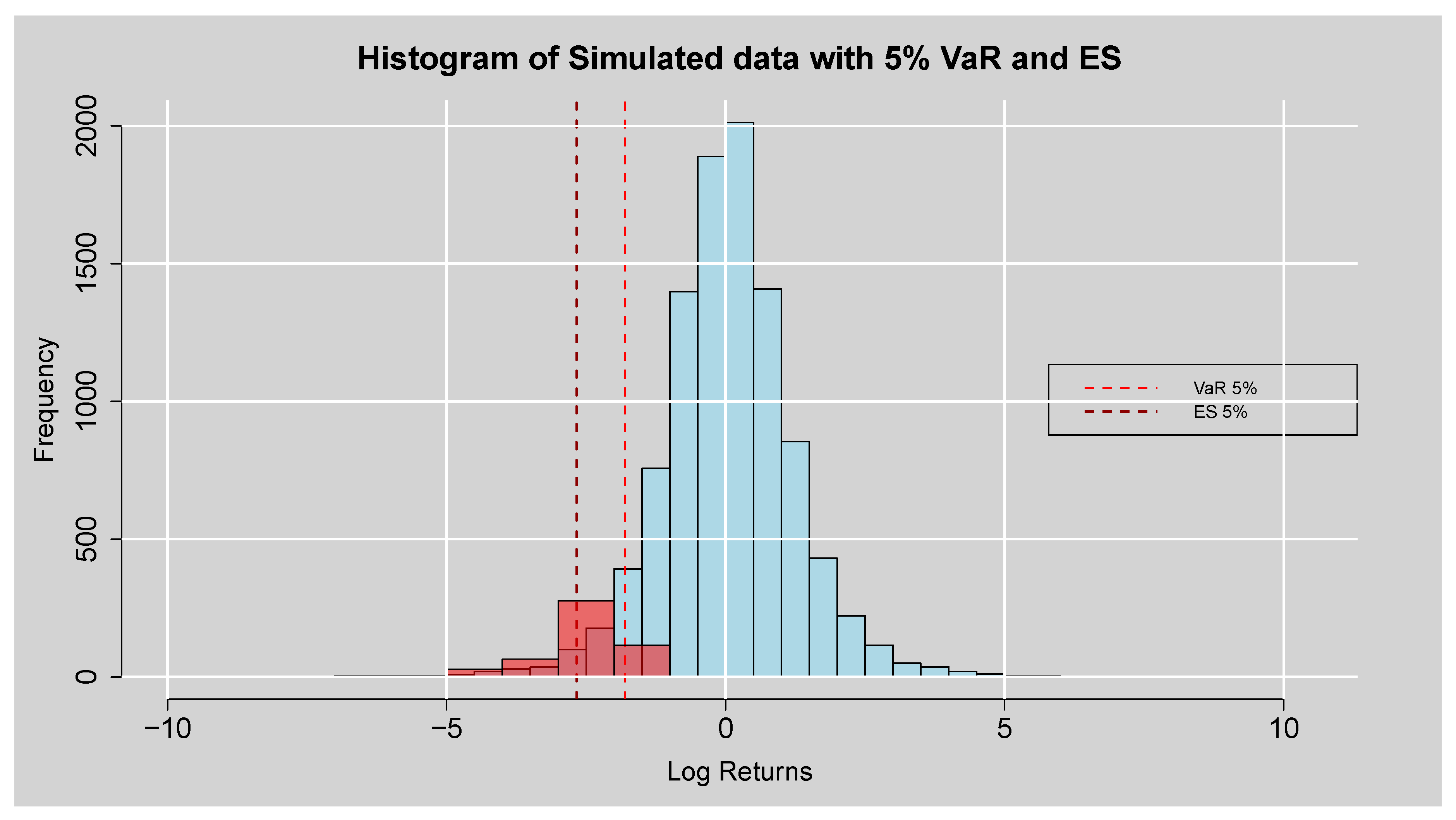

Figure 9.

Histogram plot of the simulated data with 5% Var and ES.

Figure 9.

Histogram plot of the simulated data with 5% Var and ES.

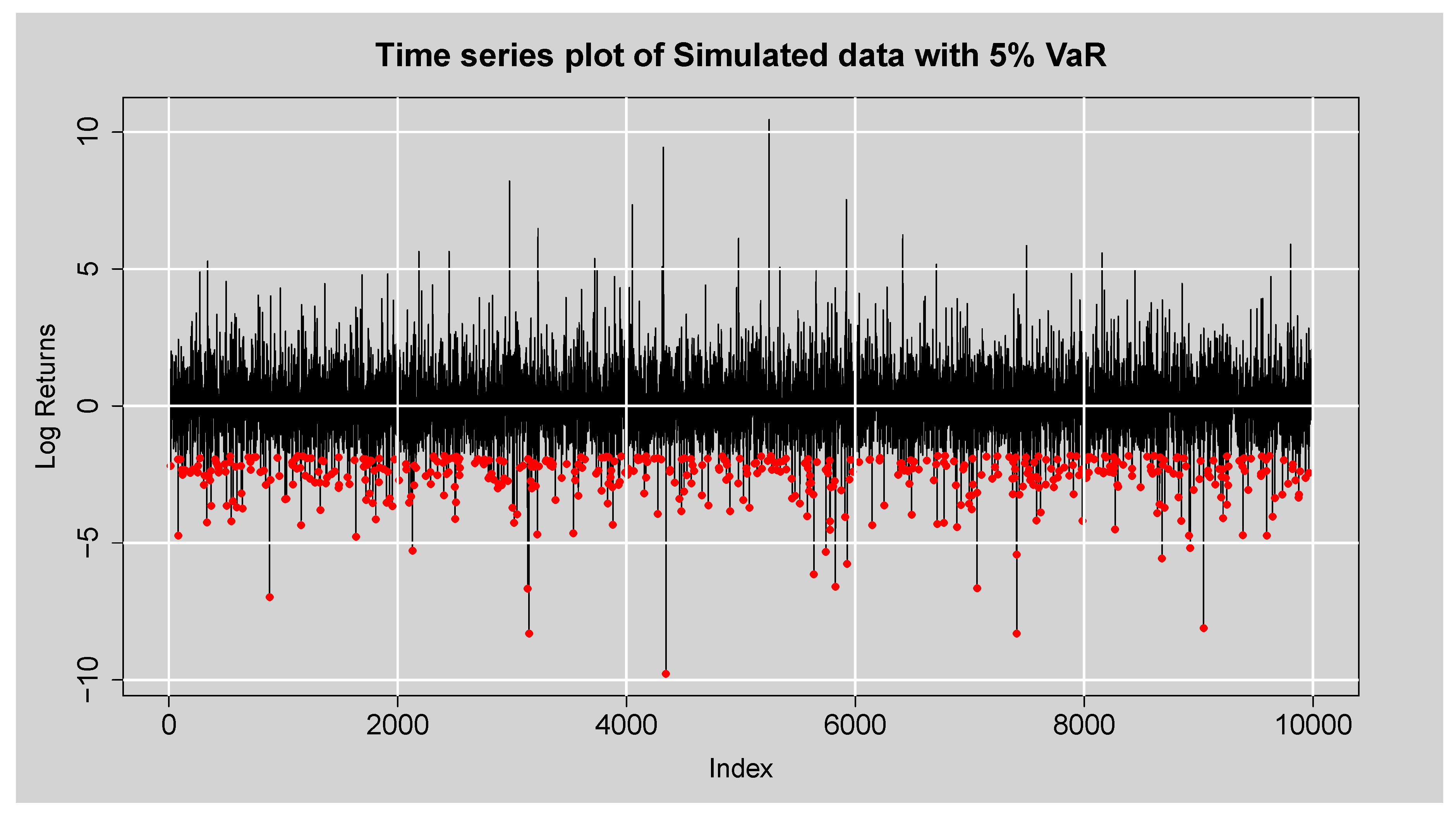

Figure 10.

Time series plot of the simulated data with 5% VaR.

Figure 10.

Time series plot of the simulated data with 5% VaR.

Figure 11.

Empirical Scores Plot of ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 11.

Empirical Scores Plot of ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 12.

Difference in Scores Plot of ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 12.

Difference in Scores Plot of ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 13.

Empirical Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 13.

Empirical Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 14.

Difference in Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 14.

Difference in Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost.

Figure 15.

Empirical Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1).

Figure 15.

Empirical Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1).

Figure 16.

Difference in Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1).

Figure 16.

Difference in Scores Plot of GAS-STD versus ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1).

Table 1.

Evaluation metrics for GAS model under seven different conditional distributions.

Table 1.

Evaluation metrics for GAS model under seven different conditional distributions.

| Evaluation Metrics |

|---|

| Model |

AIC |

BIC |

| GAS-STD |

|

|

| GAS-SSTD |

|

|

| GAS-Gaussian |

|

|

| GAS-skew-Gaussian |

|

|

| GAS-AST |

|

|

| GAS-AST1 |

|

|

| GAS-ALD |

|

|

Table 2.

Parameter estimates of the univariate GAS model with STD.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates of the univariate GAS model with STD.

| Parameter |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

t-value |

Pr() |

|

0.02733955 |

0.007908547 |

3.456962 |

0.0002731506 |

|

-0.003164797 |

0.002533474 |

-1.249193 |

0.1057973 |

|

-0.1470870 |

0.1623964 |

-0.9057283 |

0.1825398 |

|

|

|

|

0.0000000 |

|

0.1597487 |

0.02355320 |

6.782462 |

|

|

0.7711878 |

0.9345721 |

0.8251774 |

0.2046354 |

|

0.4973487 |

|

|

0.0000000 |

|

0.9782114 |

0.006412429 |

152.5493 |

0.0000000 |

|

0.9283452 |

0.07790056 |

11.91705 |

0.0000000 |

Table 3.

Average Backtest Scores for Density Forecast Evaluation of the GAS-STD Model.

Table 3.

Average Backtest Scores for Density Forecast Evaluation of the GAS-STD Model.

| Metric: |

NLS |

Uniform |

Center |

Tails |

Tail_L |

Tail_R |

| Value: |

1.1932 |

0.4417 |

0.1279 |

0.0744 |

0.2054 |

0.2363 |

Table 4.

Lagrange Multiplier (LM) Tests for the First Four Conditional Moments of the PITs.

Table 4.

Lagrange Multiplier (LM) Tests for the First Four Conditional Moments of the PITs.

| |

Test 1 |

Test 2 |

Test 3 |

Test 4 |

| Statistic |

31.32747 |

18.79682 |

36.51653 |

24.37492 |

| Critical Value |

31.41043 |

31.41043 |

31.41043 |

31.41043 |

| p-value |

0.0510 |

0.5351 |

0.0134 |

0.2264 |

Table 5.

First ten rolling forecasts of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Table 5.

First ten rolling forecasts of the fitted GAS-STD model.

| Horizon |

Location |

Scale |

Shape |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.

Rolling Risk Forecasts from the 5% VaR and ES.

Table 6.

Rolling Risk Forecasts from the 5% VaR and ES.

| VaR (5%) |

ES (5%) |

| -1.1215 |

-1.5098 |

| -1.1098 |

-1.4935 |

| -1.3192 |

-1.7742 |

| -1.2974 |

-1.7443 |

| -1.1943 |

-1.6069 |

| -1.1137 |

-1.4993 |

| -1.0925 |

-1.4704 |

| -1.4672 |

-1.9787 |

| -1.3460 |

-1.8160 |

| -1.2418 |

-1.6760 |

Table 7.

Forecast accuracy metrics for conditional location and scale of the fitted GAS-STD model.

Table 7.

Forecast accuracy metrics for conditional location and scale of the fitted GAS-STD model.

| Accuracy Measure |

Location |

Scale |

| MASE |

0.7026 |

0.7464 |

| RMSE |

0.8055 |

0.5373 |

| MAE |

0.6233 |

0.4197 |

Table 8.

Backtest Results for the 5% VaR Model.

Table 8.

Backtest Results for the 5% VaR Model.

| Test |

Statistic |

p-value |

| Kupiec Unconditional Coverage (LRuc) |

0.0400 |

0.8414 |

| Christoffersen Conditional Coverage (LRcc) |

3.5026 |

0.1735 |

| Actual/Expected (AE) Ratio |

0.9673 |

– |

| ADmean |

0.4723 |

– |

| ADmax |

1.6313 |

– |

| Dynamic Quantile (DQ) |

9.3557 |

0.2281 |

| Loss Function |

0.1097 |

– |

Table 9.

Kurtosis values of simulated data generated from the GAS-STD model under fixed shape parameter or degrees of freedom ().

Table 9.

Kurtosis values of simulated data generated from the GAS-STD model under fixed shape parameter or degrees of freedom ().

| Degrees of Freedom (): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| kurt value: |

7.3197 |

4.4795 |

3.9495 |

3.4740 |

3.3005 |

3.1968 |

3.1401 |

Table 10.

Forecast Accuracy Measures for ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1), GAS-STD, and ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Models.

Table 10.

Forecast Accuracy Measures for ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1), GAS-STD, and ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Models.

| Accuracy Measure |

ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) |

GAS-STD |

ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost |

| MASE |

0.6827 |

0.7464 |

0.0534 |

| RMSE |

1.0845 |

0.5373 |

0.1386 |

| MAE |

0.8176 |

0.4197 |

0.0595 |

Table 11.

Diebold–Mariano (DM) test results for pairwise model comparisons.

Table 11.

Diebold–Mariano (DM) test results for pairwise model comparisons.

| Comparison |

DM Statistic |

p-value |

Conclusion |

| Model A vs Model B |

|

|

Model A is significantly better than Model B |

| Model A vs Model C |

|

|

Model A is significantly better than Model C |

| Model B vs Model C |

|

|

Model C is significantly better than Model B |