1.1. Overview

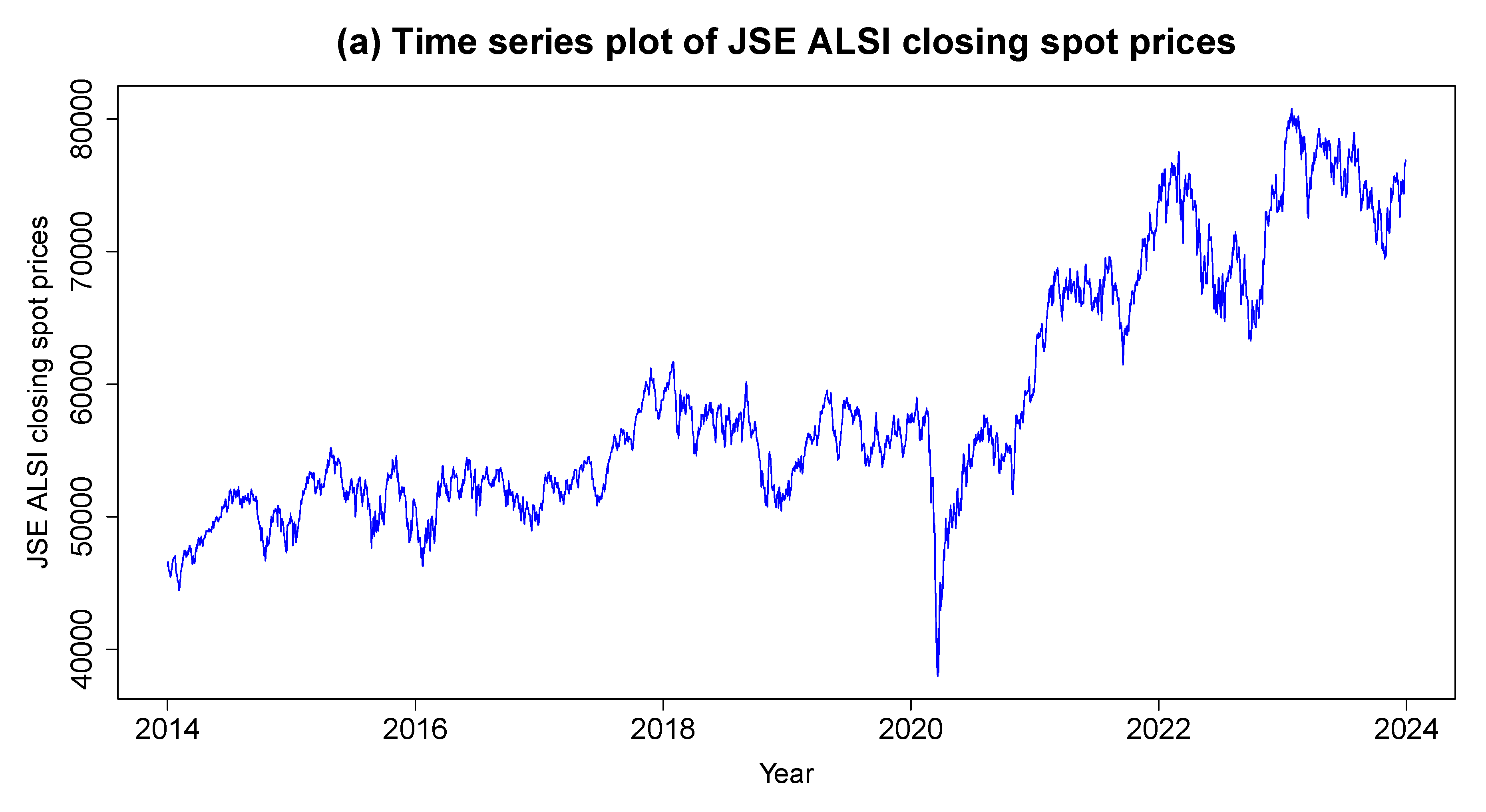

It is common knowledge that financial markets are incredibly unpredictable and erratic. Historical evidence indicates that financial markets have a significant influence on economies across the globe. In many economies, returns volatility serves as a gauge of the degree of uncertainty around short-term monetary policy, which can either stimulate or restrain economic activity in South African economy. Investors shifting their money in and out of the stock market or inside it but into other financial instruments is what causes the index’s fluctuation levels and, in turn, volatility [

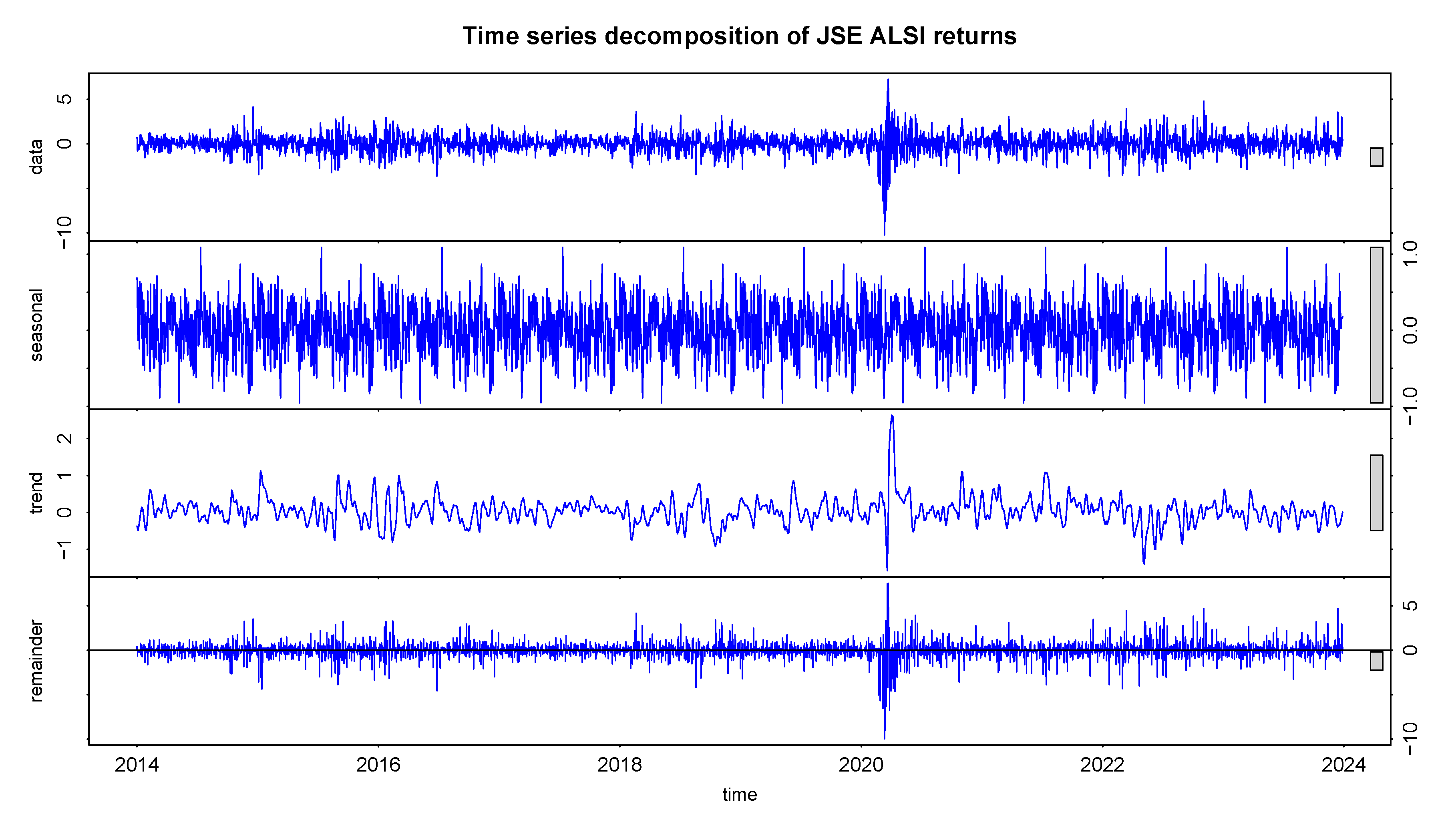

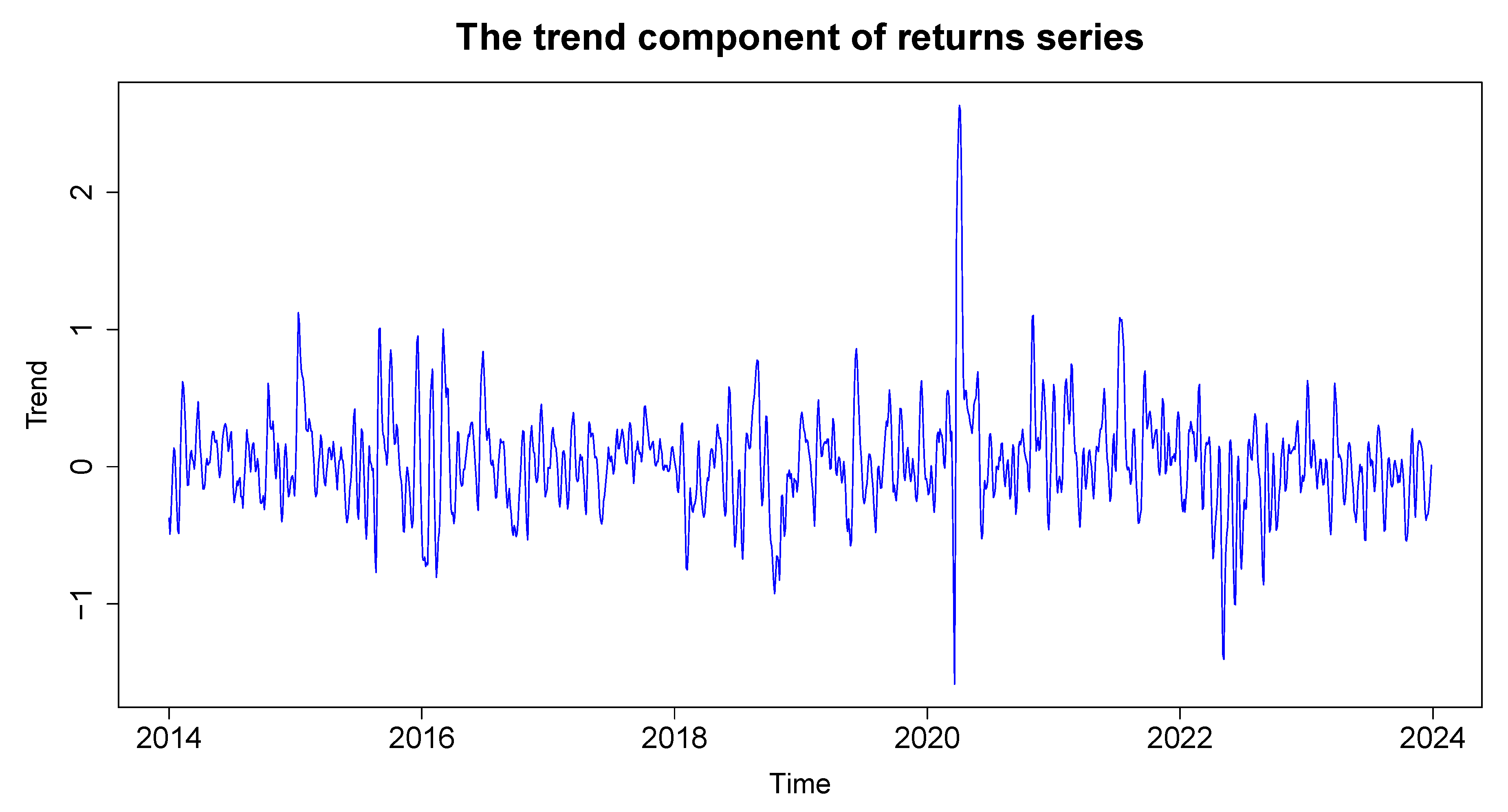

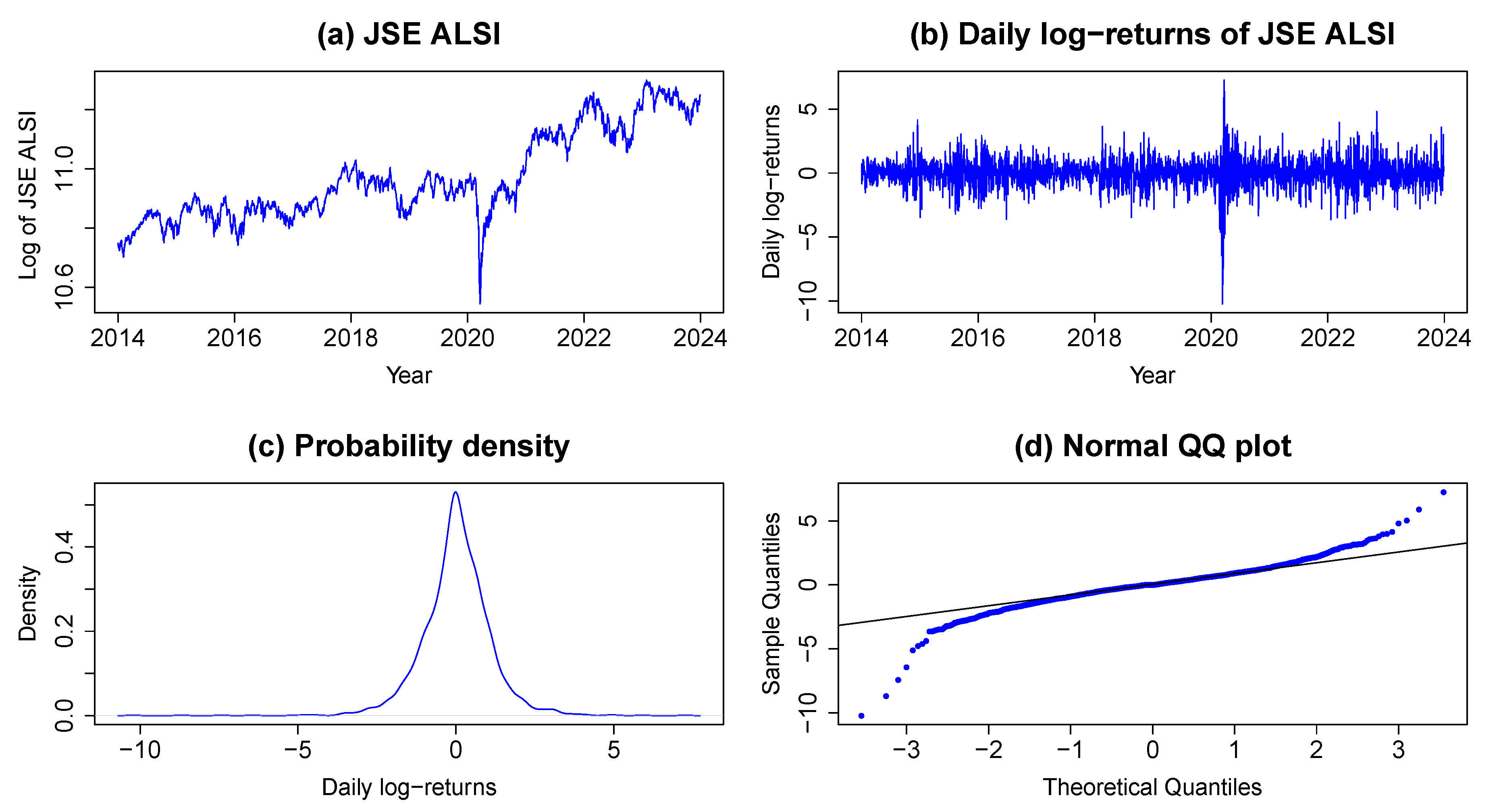

1]. The more the volatility of the market index, the greater the risk. Furthermore, volatility is a basic topic in financial analysis since there is vital demand in terms of forecasting and modelling volatility in capital markets, specifically in the context of investment strategies, techniques for managing risk, and the assessment of financial assets. The JSE ALSI is the primary market index in South Africa, assessing the performance of all listed companies. The JSE ALSI accounts for 98% of the total market capitalisation value. It is influenced by macroeconomic indicators like GDP growth, inflation, interest rates, commodity prices, market changes, liquidity, and sentiment.

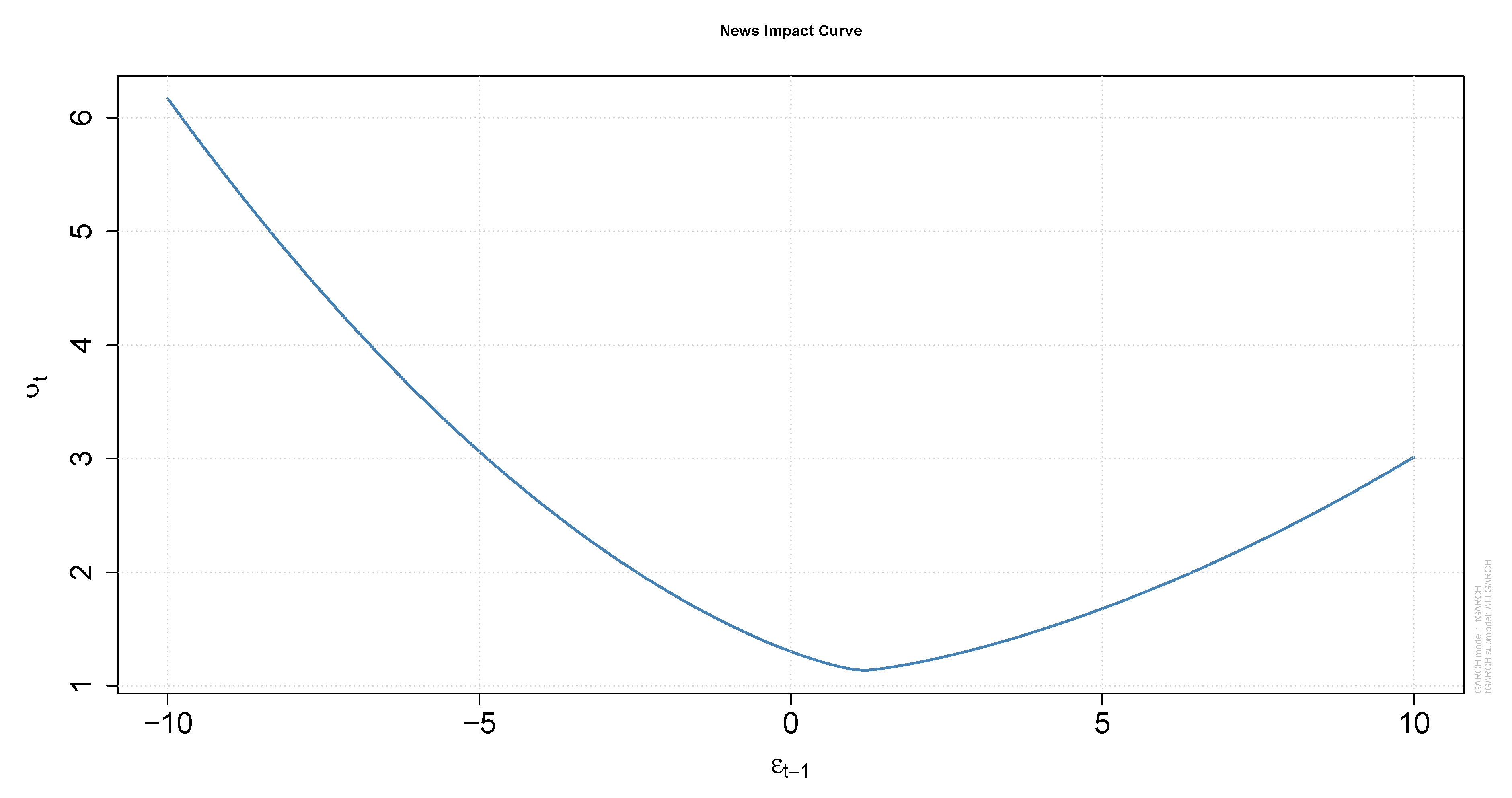

The leverage effect demonstrates how previous positive and negative values affect the prevailing stock market, with negative returns contribute to volatility more significantly than good returns [

2]. Modelling time series with different variances and heteroskedasticity was consistently hidden. Reference [

3] made an early attempt to address these issues using the family of models known as Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH). Reference [

4] introduced the family of models known as Generalised Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH), which is aimed to capture leptokurtic returns as well as volatility clustering. Despite their advances, GARCH models have come under criticism for failing to accurately account for the leverage effect found in the financial markets [

5]. There are various research that focus on the stock market connectivity between countries. Reference [

6] examined the volatility levels in the stock markets of Singapore, Hong Kong, and India. According to this study, markets responded to information in a highly interconnected manner and had a significant GARCH impact, which affected both mean and volatility. Reference [

7] discovered an unbalanced association between South Korea and Japan’s stock price markets throughout the same period. Reference [

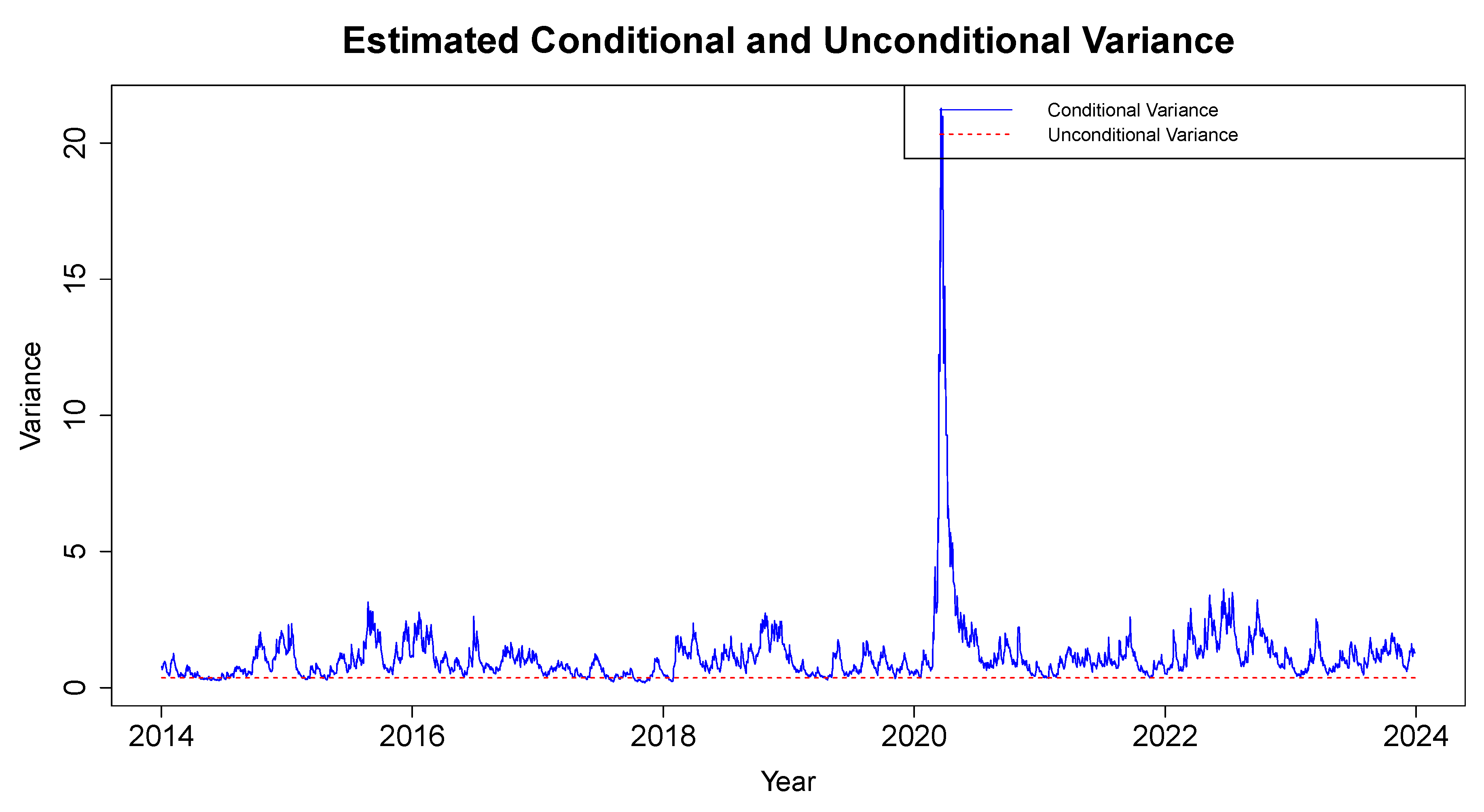

8] modelled the volatility of the JSE ALSI using Bayesian and frequentist methods. The empirical findings show that the conditional and unconditional volatility of the JSE ALSI are both reflected in the Bayesian Autoregressive Moving Average-Generalised Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (BARMA-GARCH-t) model.

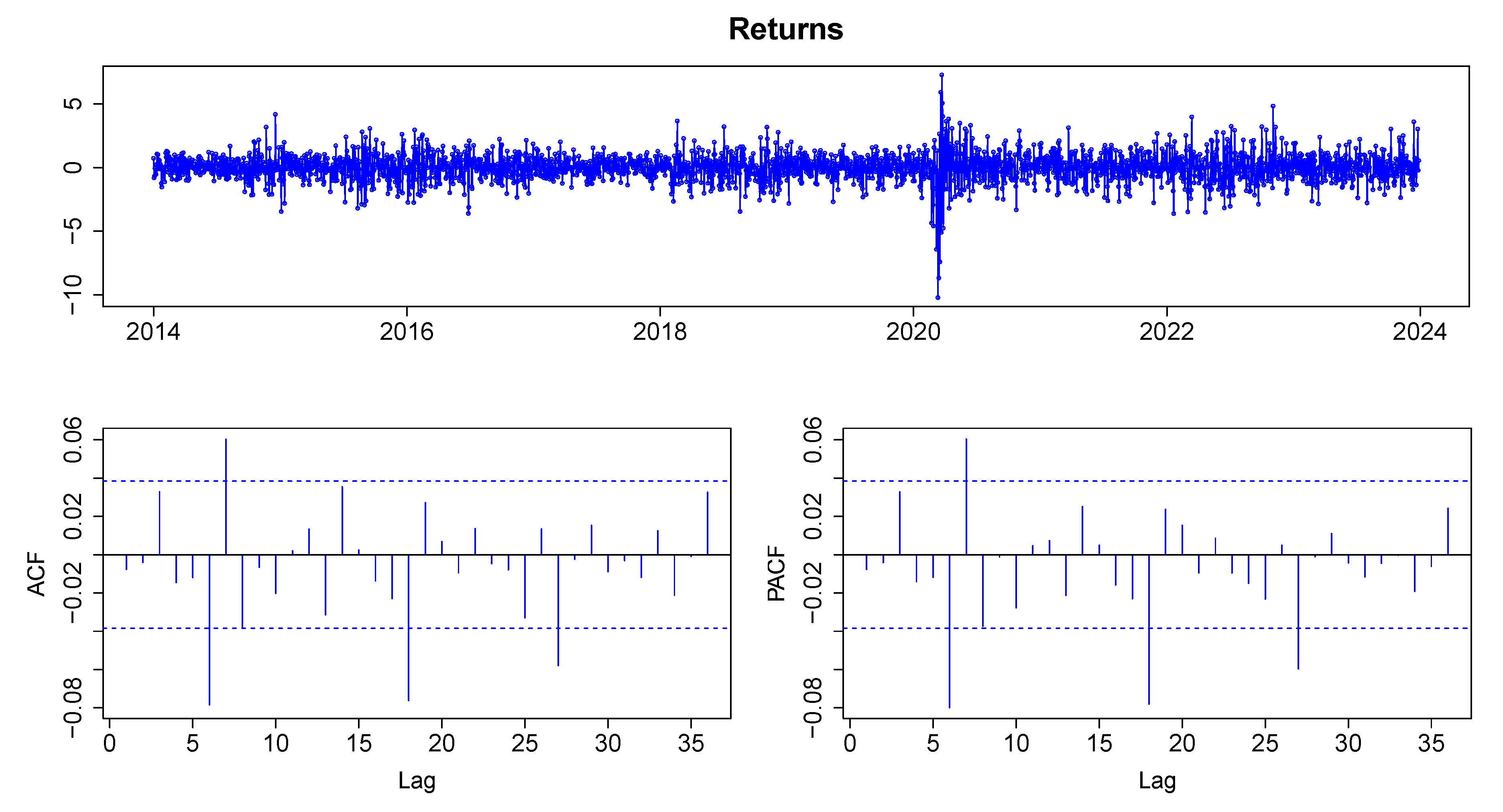

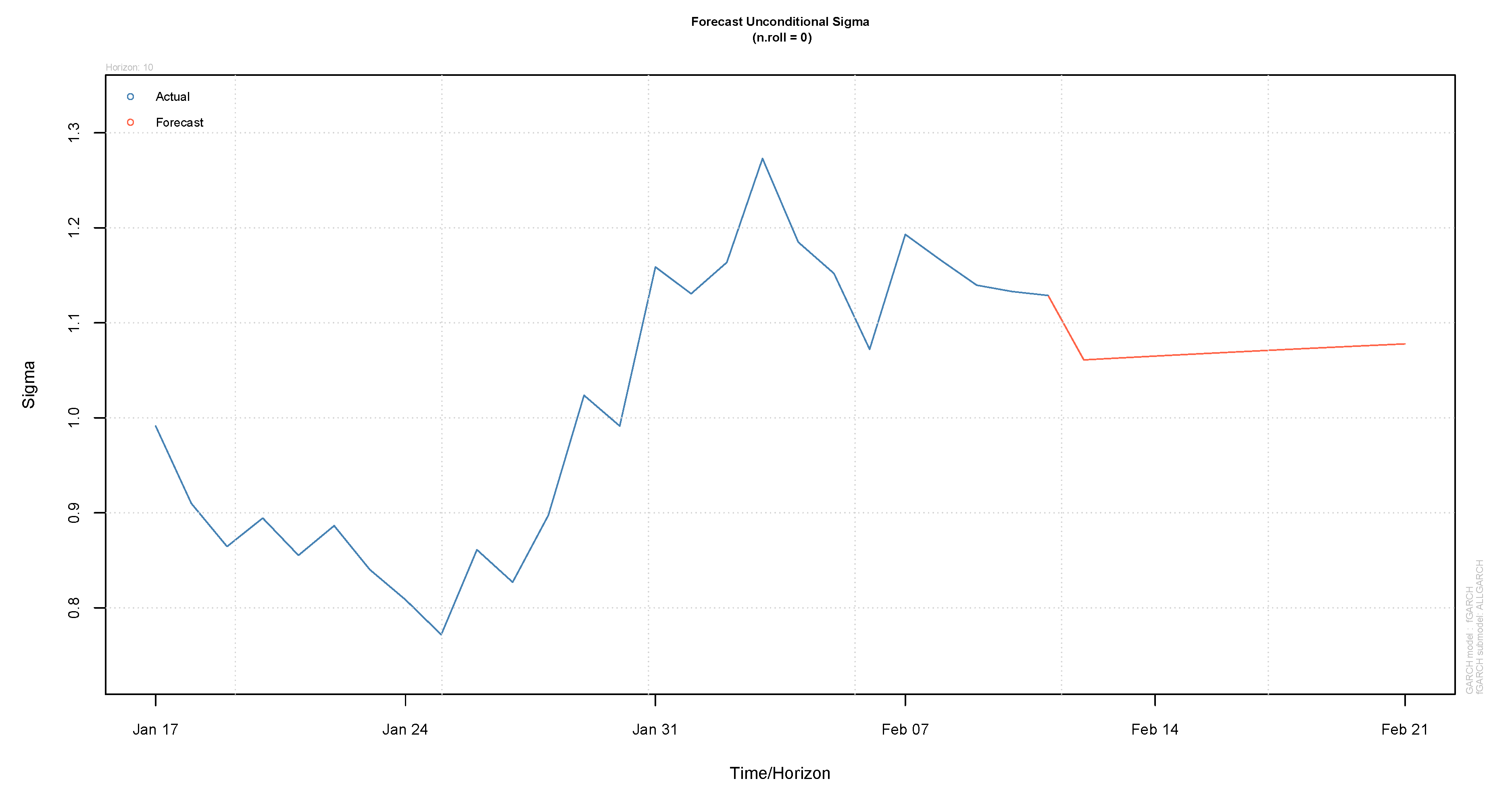

This study aims to model and analyse the volatility of the JSE ALSI from 2014 to 2023 using the family GARCH model. The JSE ALSI serves as a key indicator of market performance in South Africa, but its volatility presents significant challenges for investors, risk managers, and policymakers. Traditional models often fail to capture the complex dynamics of volatility, necessitating more advanced techniques like the family GARCH model, which offers the potential for accurate volatility projections. Despite its ability to model volatility, the application of GARCH models to the JSE ALSI remains limited, highlighting the need for this study. By investigating various GARCH models, this study seeks to enhance the understanding of volatility patterns in the South African equity markets, providing critical insights for informed decision-making and effective risk management. The findings of this study offers valuable contributions to improving financial stability and efficiency, enabling investors and policymakers to navigate market volatility more effectively. This study’s scope includes the collection of historical return data, preprocessing, and estimation of multiple GARCH models, with the goal of providing practical solutions for risk management and investment strategies.

1.2. Literature Review

Examining volatility in financial markets, especially by employing sophisticated econometric models like the GARCH model, is essential for effectively understanding and managing associated risks. The JSE ALSI, as a comprehensive indicator of the South African equity market, presents a compelling subject for volatility analysis due to its broad representation of diverse sectors within the economy. The purpose of this review is to examine how researchers have applied GARCH models to analyse and forecast volatility in the JSE ALSI. It outlines the models previously used in modelling volatility of JSE ALSI. Over the past two decades, financial data analysis, particularly in the area of volatility forecasting, has gained notable importance in the financial literature, particularly following the financial crisis. Numerous models have been introduced for predicting volatility within the field of financial modelling. Nonetheless, studies have yielded significantly varied outcomes regarding which models are most effective at forecasting volatility. The foundation of volatility modelling for financial time series data was laid by [

3] with the introduction of Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH) models, intended to account for the significant volatility observed in the log returns of financial data. Reference [

4] further developed these ARCH models into GARCH models to account for asymmetric effects and long memory in variance observed in financial time series. Several variations of the GARCH model have been introduced, such as the Integrated GARCH (IGARCH) model by [

9], the Glosten-Jagannathan-Runkle GARCH (GJR-GARCH) model by [

10], the Asymmetric Power ARCH (APARCH) model developed by [

11], the Exponential GARCH (EGARCH) model proposed by [

12], and the family GARCH (fGARCH) model developed by [

13].

Subsequent to the recent national financial downturn, there has been an increased interest among academics and practitioners in analysing financial data, particularly regarding the uncertainties of the stock market. Consequently, significant research attention has been directed towards modelling and forecasting stock volatility, especially in developed countries. Reference [

14,

15] significantly contributed to understanding that the uncertainty associated with stock prices, as indicated by variance, fluctuates over time. Reference [

15] also identified that volatility clustering and leptokurtosis frequently occur in financial time series. Additionally, reference [

2] highlighted a phenomenon known as the leverage effect, where stock prices exhibit a negative correlation with changes in volatility. Reference [

16] further explored this leverage effect, suggesting that a decline in equity value results in an increased debt-to-equity ratio, which elevates the firm’s risk profile, thereby leading to heightened future volatility [

17]. As a result of these observations of volatility clustering, the assumption of homoscedasticity is rendered less applicable, prompting researchers to focus on modelling techniques that account for time-varying variance.

Reference [

18] examined how news affects the volatility of the Nigerian stock market using ARCH class models. The findings suggested the existence of a leveraging effect, indicating that negative news affects volatility more than positive news. Reference [

19] investigated the influence of macroeconomic variables on volatility of the stock return at the Nairobi Securities Exchange in Kenya. Their research examined how fluctuations in foreign exchange rates, interest rates, and inflation affect stock return volatility over a decade, utilising monthly time series data spanning from January 2001 to December 2010. The study employed EGARCH and TGARCH models for analysis. The findings revealed that the stock returns exhibited leptokurtic characteristics and deviated from a normal distribution. Additionally, the results confirmed that foreign exchange rates, interest rates, and inflation significantly impact the volatility of stock returns in Nairobi.

Reference [

20] examined the fluctuations in the Naira/Dollar exchange rates in Nigeria, employing several models, including EGARCH(1,1), GJR-GARCH(1,1), GARCH(1,1), APARCH(1,1), TS-GARCH(1,1) and IGARCH(1,1). This analysis utilised monthly time series data spanning from January 1970 to December 2007. The findings indicated that the APARCH and TS-GARCH models provided the best fit for the observed data. Reference [

21] investigated the time-series characteristics of daily stock returns for four companies listed on the Nigerian Stock Market, focusing on data spanning from 2 January 2002, to 31 December 2006. They applied three heteroscedastic models: GJR-GARCH(1,1), EGARCH(1,1) and GARCH(1,1). The companies analysed in the study included Unilever, Mobil, UBA and Guinness. The return series exhibited several common traits of financial time series, such as leptokurtosis, leverage effects, negative skewness and volatility clustering. The analysis revealed that the GJR-GARCH(1,1) model yielded the best fit for the data examined.

Reference [

22] explored the efficacy of an asymmetric normal mixture generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (NM-GARCH) model using standard benchmark GARCH models. The results of the study revealed that the NM-GARCH model effectively captures the variations in kurtosis and skewness over time. Furthermore, the study illustrated that implementing the NM-GARCH(1,1) model with a skewed Student-t distribution enhances the predictive capabilities of volatility models. Reference [

23] conducted an analysis of volatility return and financial market risk on the JSE. The modelling process was executed in two phases: initially, the mean returns were estimated using ARMA(0, 1) model, followed by the application of several univariate GARCH models, including EGARCH(1, 1), GARCH-M(1, 1), TGARCH(1, 1), and GARCH(1, 1), to assess conditional volatility. The results indicated the presence of leverage effects, as well as GARCH and ARCH effects in the JSE returns during the study period. Their evaluation of forecasts revealed that the ARMA(0, 1)-GARCH(1, 1) model yielded the most accurate predictions for out-of-sample returns over a three-month horizon. Reference [

24] used both univariate and multivariate GARCH models to study the volatility of the JSE index. The leverage impact is clear in the log returns JSE index, according to the study’s empirical findings. Reference [

25] employed GARCH models to investigate the volatility of stock returns on the JSE. Their empirical findings revealed that leverage effects were absent and indicated that stock return volatility is persistent.

Reference [

26] illustrated the extension of the Beta-t-EGARCH model to a Skew-t model, demonstrating that this model provides a superior fit compared to the GJR-GARCH model, which served as a benchmark. Additionally, [

27] developed autoregressive models incorporating exogenous variables, power transformations, and threshold GARCH errors, referred to as ARX-PPTGARCH. The Bayesian method is used to estimate parameters. A model called ARX-GARCH is used to perform a comparative study. The study’s findings showed that the ARX-PPTGARCH model effectively represents key financial features including heteroscedasticity and asymmetry. In the study of Australian equities index data, [

28] concluded that the GJR-GARCH model, as established by [

10], yields superior results in forecasting volatility. Reference [

29] found similar outcomes in their investigation of daily stock returns in Japan. Reference [

30] examined the impact of the financial crisis on the Malaysian stock market during the period from 2007 to 2009. The outcomes contrasted by the authors with the volatility that persisted following the Asian Crisis. The findings showed a modest reduction in volatility persistence, accompanied by a notable increase in overall volatility and a slight uptick in the leverage effect. This study utilised GARCH, EGARCH, and GJR-GARCH models for the analysis. Nonetheless, reference [

31] examined volatility effects on the capital markets of the BRIC nations during the financial crisis of 2007 to 2009 using GJR-GARCH, GARCH and EGARCH models. The authors discovered that the market responds to volatility shocks more quickly, with asymmetry and less persistence. Reference [

32] conducted an analysis of South African stock market volatility surrounding the 2014 global oil crisis. They employed both symmetric and asymmetric GARCH models to assess conditional volatility, concluding that the asymmetric GARCH model best captured the behavior of equity returns, including during a crisis period.

This subsection reviewed empirical studies on volatility modelling using GARCH models, focusing on the JSE ALSI and other financial markets. The evolution of GARCH models, including variants like EGARCH, GJR-GARCH, and fGARCH, highlights their adaptability in capturing key features such as volatility clustering, leverage effects, and asymmetric responses to shocks. Applications in stock, commodity, and foreign exchange markets emphasize the models’ efficacy under diverse market conditions, including crises. The fGARCH model is an appropriate choice for this study due to its ability to capture both volatility clustering and asymmetric responses to shocks, which are characteristic features observed in financial time series, including the JSE ALSI.