1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), or atypical antipsychotics, have become central to the pharmacological treatment of paediatric psychiatric disorders. Their indications now extend beyond psychotic illnesses to include disruptive behaviour disorders (DBDs), irritability linked to autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Tourette syndrome, and various other neurodevelopmental and behavioural conditions [

1,

2,

3]. Among these, risperidone stands out as one of the few antipsychotics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for managing irritability in ASD. It has also shown effectiveness in controlling aggression, conduct issues, and symptoms of severe attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [

1,

2,

4]. Its broad clinical utility, along with a relatively lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects compared to first-generation antipsychotics, has made it a commonly prescribed agent, often preferred over other SGAs like olanzapine and quetiapine in paediatric populations [

1,

3,

5].

However, the metabolic adverse effects associated with risperidone use in children are increasingly concerning. Numerous systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and observational studies have reported a heightened risk for rapid weight gain, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, and hyperprolactinaemia—often emerging within a few weeks of starting therapy and persisting even with lifestyle interventions [

1,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Weight gain is particularly common, with some studies reporting average increases exceeding 6% of baseline body weight within two months and nearly one-third of children experiencing clinically meaningful metabolic changes [

7,

9,

10]. These disturbances are alarming due to their potential long-term impact, including elevated risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in adulthood [

11,

12]. Importantly, these risks are not limited to older children or high-risk individuals; evidence suggests a broad vulnerability across various ages, diagnoses, and dosing patterns [

9,

12,

13].

Mechanistically, risperidone’s antagonism at histamine H₁ and serotonin 5-HT2C receptors is believed to increase appetite and caloric intake, partly by altering hypothalamic neuropeptide signalling [

14,

15,

16]. Additionally, dopamine receptor blockade and interference with insulin pathways may disrupt energy balance and contribute to both fat accumulation and metabolic abnormalities, even in the absence of overt weight changes [

14,

15,

17]. Recent studies have also implicated changes in the gut microbiota and reductions in non-aerobic resting metabolic rate as possible contributors to risperidone-induced weight gain [

17].

Although global trends in SGA use are reflected in India, there is a notable lack of region-specific data regarding metabolic effects and treatment outcomes in Indian children [

18]. This gap is significant, as genetic, dietary, and environmental factors may influence the safety and efficacy profile of risperidone in Indian populations. Moreover, while international guidelines recommend regular monitoring of BMI, fasting glucose, lipids, and other metabolic parameters, adherence to these protocols remains inconsistent, both globally and within Indian clinical settings [

9,

12,

19]. Studies repeatedly show poor compliance with such monitoring recommendations among Indian cohorts as well [

12,

19,

20].

In this context, it becomes crucial to evaluate both the metabolic impact and therapeutic outcomes of risperidone in Indian paediatric patients. Specifically, examining how early changes in weight and BMI correlate with behavioural improvements—such as those measured using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)—can support more balanced, evidence-based treatment planning. To contribute to this understanding, we conducted a prospective observational study assessing the short-term metabolic effects and behavioural outcomes associated with risperidone therapy in children at a tertiary-care hospital in India.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a single-centre, prospective observational study conducted in the Department of Paediatric Medicine at Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, India. The study period spanned from January to July 2025. Prior to study initiation, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from the caregivers of all participants, and assent was secured from children wherever appropriate, in accordance with institutional guidelines.

2.2. Participants

Children between the ages of 3 and 15 years were screened for eligibility. Inclusion criteria consisted of (i) antipsychotic-naïve children initiated on risperidone therapy for clinical diagnoses including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder, or other disruptive behaviour disorders. Exclusion criteria included: (i) presence of pre-existing metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes mellitus, familial hyperlipidaemia), (ii) current or recent use of medications known to affect weight or glucose–lipid metabolism (e.g., corticosteroids, metformin), and (iii) significant medical comorbidities that could confound metabolic outcomes or impede follow-up.

2.3. Sample Size Estimation

Sample size was calculated using a two-tailed paired-means formula with an alpha level of 0.05, power of 80%, standard deviation of 5 kg, and a minimum detectable mean weight change of 3 kg. Based on this, a minimum of 23 participants was required. To account for an anticipated 20% attrition rate, a total of 27 children were enrolled.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality of data distribution. For within-subject comparisons of baseline and follow-up measurements, paired t-tests were employed for normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used for non-parametric data. Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients were computed to examine associations between percentage changes in metabolic parameters (e.g., weight and BMI) and risperidone dose (mg/kg), age, and duration of treatment. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

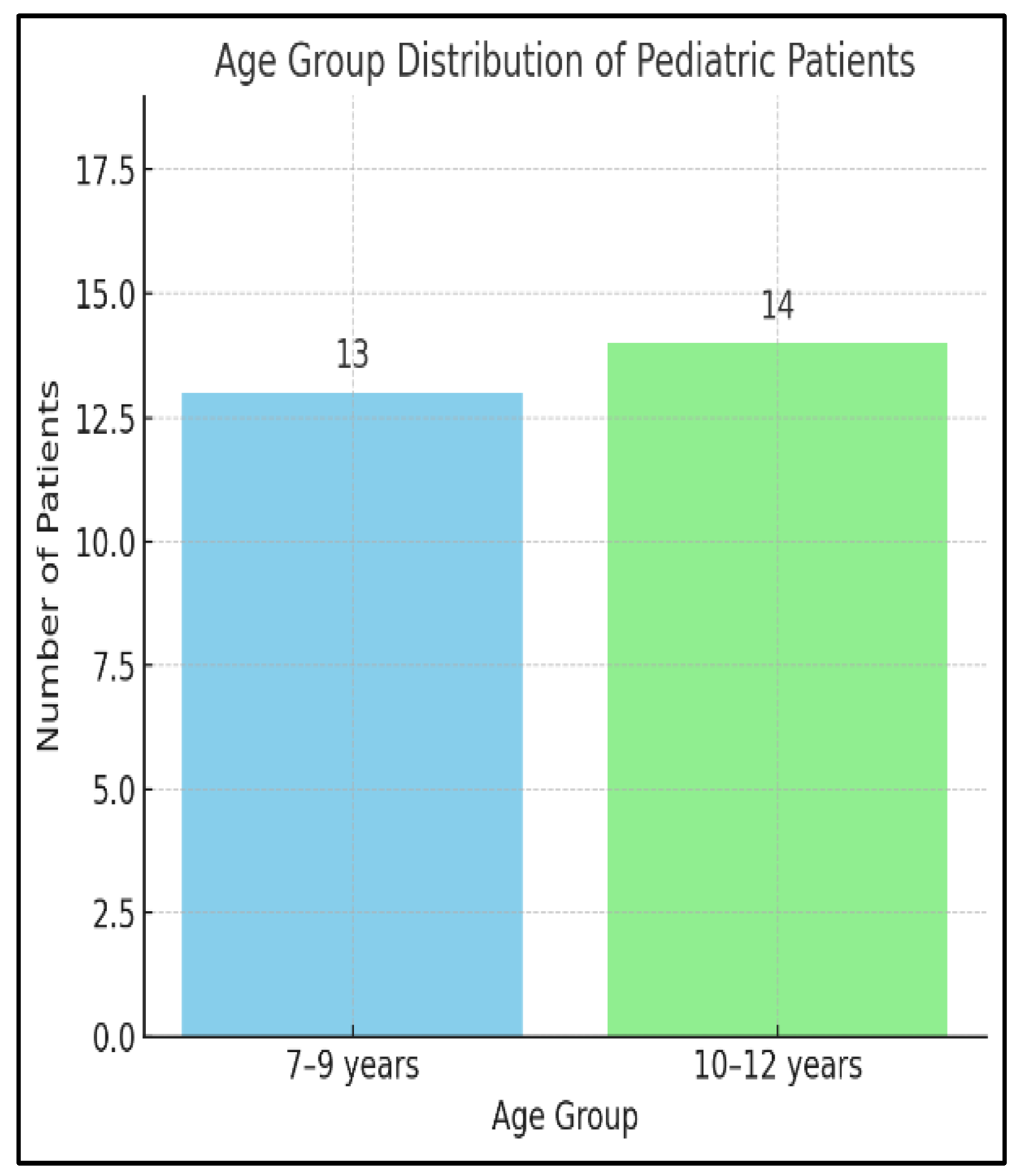

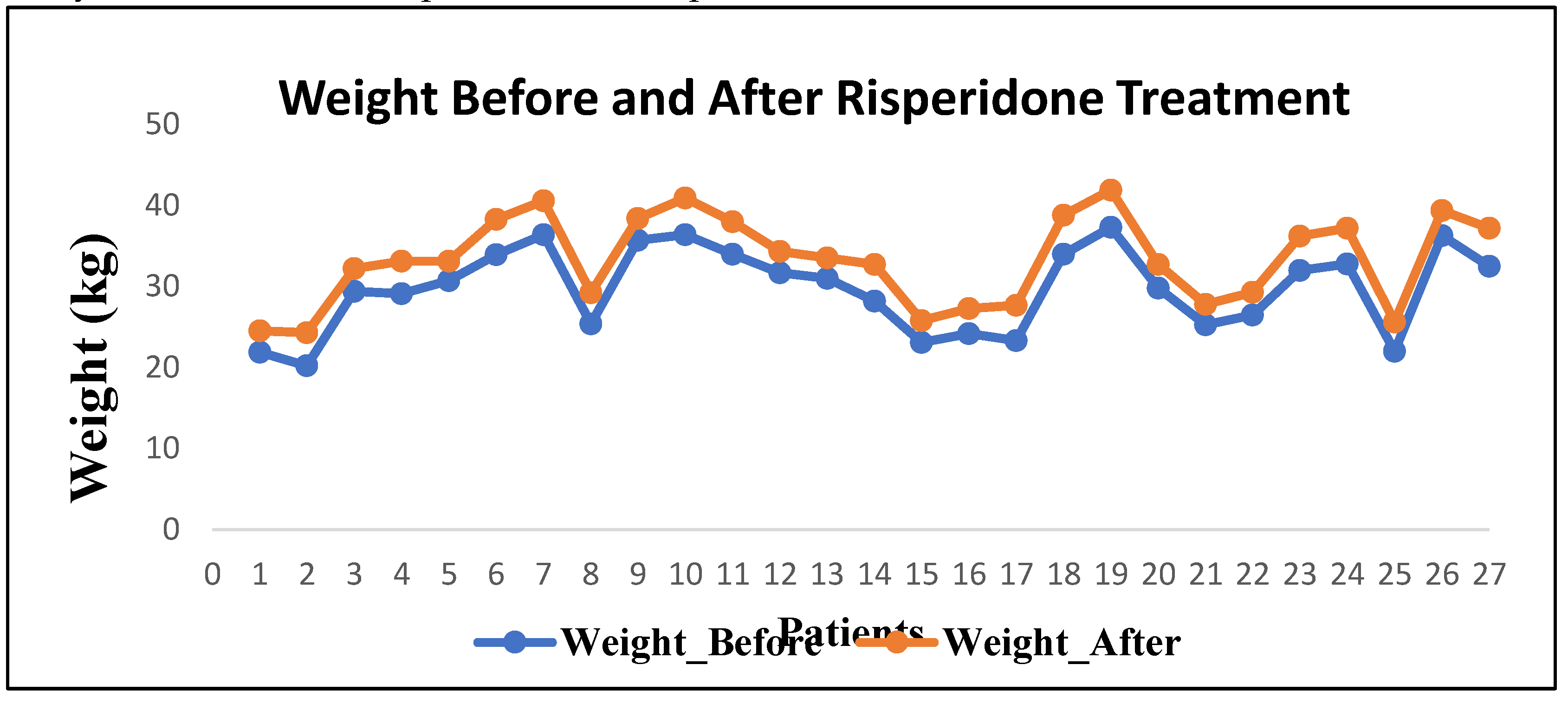

A total of 27 paediatric patients were enrolled, with 24 completing the 10-week follow-up period (11.1% attrition). The mean age was 9.6 ± 2.9 years, and the sample comprised 79% males. Indications for risperidone initiation included Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD, 50%), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD, 29%), and other disruptive behaviour disorders (21%). The mean baseline weight was 30.2 ± 9.1 kg, and the mean BMI was 17.3 ± 2.1 kg/m².

Most participants (87.5%) were antipsychotic-naïve at baseline, and none had significant comorbid medical conditions. All patients were treated in an outpatient setting, and medication adherence was confirmed through caregiver reports and follow-up assessments.

3.2. Metabolic Outcomes

Following approximately 10 weeks of risperidone therapy, a statistically significant increase in both weight and BMI was observed. The mean weight increased by 3.6 ± 1.9 kg (p < 0.001), and the mean BMI rose by 2.2 ± 1.1 kg/m² (13% increase; p < 0.001). Among participants, 91.7% (22/24) experienced clinically significant weight gain (>7% of baseline). Shapiro–Wilk testing confirmed normality of distribution for parametric comparisons.

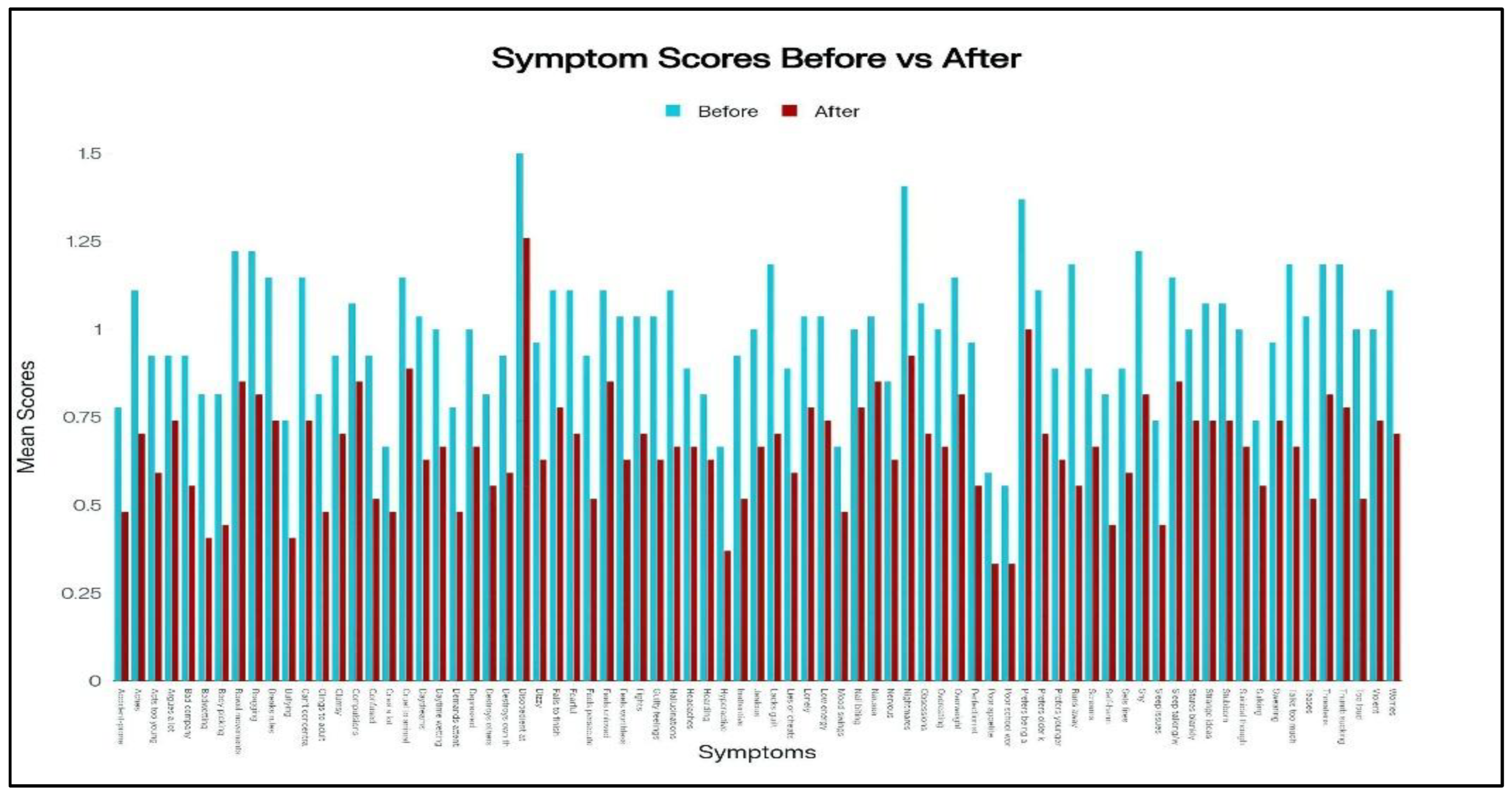

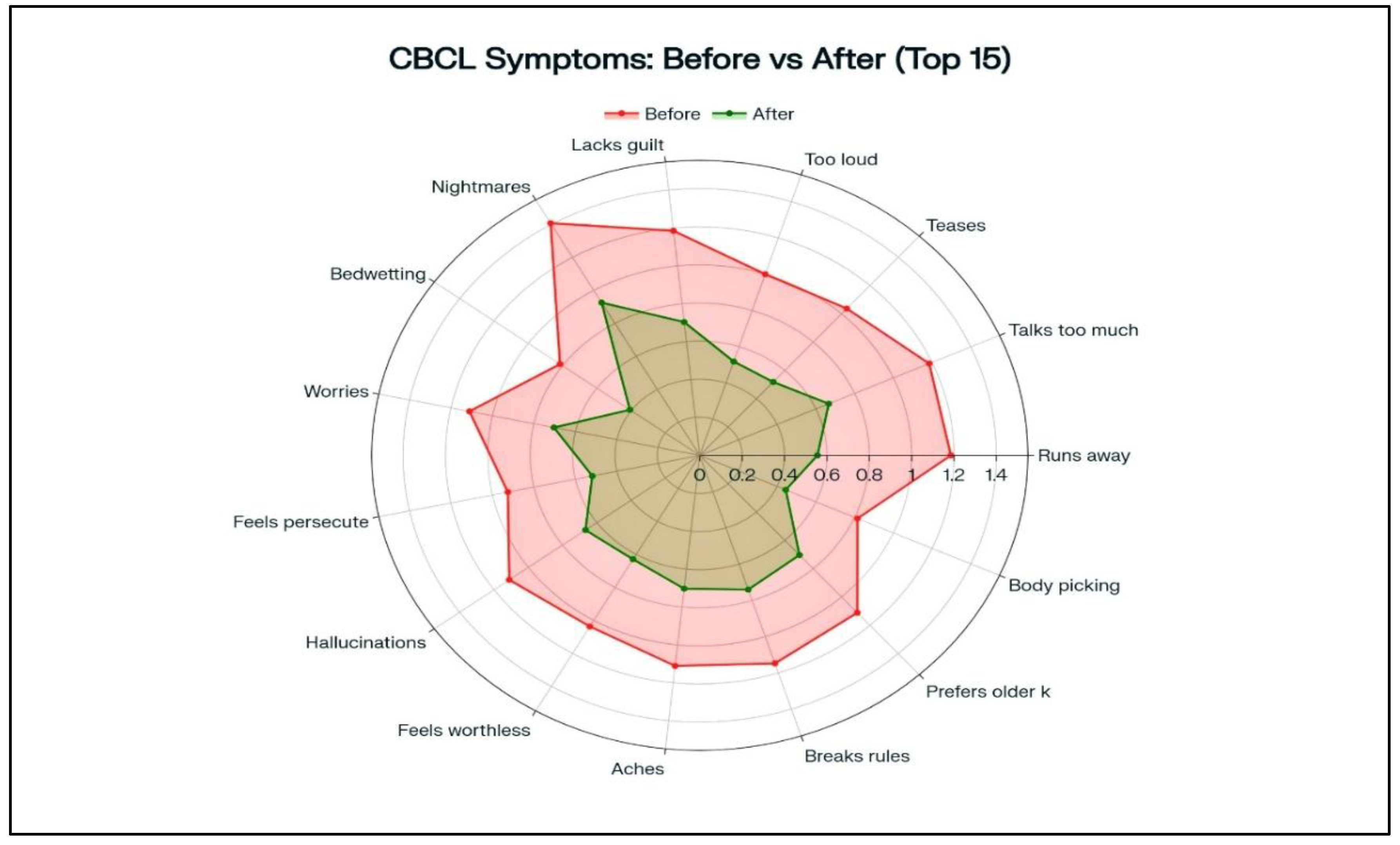

3.3. Behavioural Outcomes.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) total scores significantly improved from a baseline mean of 71.5 ± 8.3 to 47.2 ± 9.7 at follow-up, representing a 34% reduction (p < 0.001). Subscale improvements were most notable in externalizing behaviors such as aggression and rule breaking.

3.4. Dose–Response and Correlation Analyses

A positive correlation was identified between risperidone dose (mg/kg/day) and percentage change in weight (r = 0.46, p = 0.024), suggesting a dose-dependent metabolic response. No significant associations were found between weight/BMI change and participant age (r = 0.12, p = 0.53) or treatment duration (r = 0.09, p = 0.62). Similarly, no correlation was observed between dose and behavioural improvement (r = 0.18, p = 0.41).

4. Discussion

In this prospective observational study, risperidone treatment over an average duration of 9.5 weeks resulted in a significant mean weight gain of 3.6 kg and a 13% increase in BMI among paediatric participants, consistent with prior findings in similar cohorts [

6,

8,

11]. These metabolic changes appeared dose-dependent but not time-dependent, indicating that early shifts in energy balance are likely driven by pharmacodynamic appetite stimulation rather than cumulative drug exposure. Behavioural outcomes were notably improved, with a 34% reduction in total Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) scores, supporting risperidone’s efficacy in managing disruptive symptoms, a finding in line with previous studies comparing its performance to stimulant medications. The magnitude of weight gain observed in our study closely mirrors the 5.4 kg increase reported over 24 weeks in ASD clinical trials, and is comparable to 0.45 standard deviation increases in BMI z-scores found in preschool populations. Our moderate dose–response correlation aligns with mixed-model analyses suggesting greater weight gain at higher mg/kg exposures, while the lack of significant age-related differences in weight change is consistent with literature indicating that metabolic risk affects a broad paediatric age range. Behaviourally, our findings reaffirm risperidone’s superiority in reducing aggression, though its impact on core ADHD symptoms remains modest. Clinically, these results underscore the importance of early metabolic monitoring, recommending baseline anthropometric and laboratory assessments, review within 4–6 weeks, integration of weight-neutral strategies such as dietary counselling and physical activity, possible melatonin co-administration, and the use of the lowest effective dose. Pharmacogenetic testing for CYP2D6 poor metabolisers may further personalise therapy. The study’s strengths include its prospective design, consistent baseline characteristics, and combined assessment of behavioural and metabolic outcomes. Limitations include the small sample size, single-centre setting, absence of follow-up lipid and glucose data, and limited observation period that precludes evaluation of long-term cardiometabolic risk. Future research should focus on multicentre, longitudinal studies in Indian populations to assess the persistence of weight gain, progression of metabolic syndrome components, and the potential mitigating effects of lifestyle modifications or adjunctive pharmacological interventions.

5. Conclusions

This prospective observational study highlights the dual impact of risperidone therapy in children, demonstrating significant short-term behavioural improvement alongside rapid, dose-related weight and BMI gain. While risperidone effectively reduced disruptive symptoms within 10 weeks, the early onset of metabolic changes—largely independent of age or treatment duration—raises important concerns about long-term health risks. These findings reinforce the need for vigilant baseline and follow-up monitoring, judicious dosing, and integration of lifestyle counselling from the outset of treatment. Larger, long-term studies are essential to guide safer, individualised risperidone use in paediatric populations.

References

- Lambert C, Panagiotopoulos C, Davidson J, Goldman RD. Second-generation antipsychotics in children: risks and monitoring needs. Can Fam Physician. 2018, 64, 634–636. [PubMed Central]

- Cheng-Shannon J, McGough JJ, Pataki C, McCracken JT. Second-generation antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004, 14, 372–394. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokiranta-Olkoniemi, E. Clinical use of second-generation antipsychotics in children. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Psychol. 2017, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Kang L, Zou C. Efficacy and safety of risperidone interventions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2025, 35, 177–184. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chawath S, Ramdurg S, Badiger S, Chaukimath SP. Risperidone-induced anaemia. Natl Med J India. 2023, 36:22–23.

- MedlinePlus. Risperidone. [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine; [updated 2024 Jul; cited 2025 Aug 1].

- Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009, 302, 1765–1773. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wiegand, S. Therapieüberwachung bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit atypischen Antipsychotika. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019, 62, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Buitelaar JK, Willemsen-Swinkels SH, Papanikolau K, Ravelli A, van Waardenburg D, van der Gaag RJ, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of behavioral disorders associated with autism and pervasive developmental disorders: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62, 636–647. [PubMed Central]

- Butler, DJ. Risperidone use in children with autism carries heavy risks. Spectrum News. 2022 May 19. Available from: https://www.thetransmitter.org/spectrum/risperidone-use-in-children-with-autism-carries-heavy-risks/.

- Child Mind Institute. What parents should know about Risperdal. [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://childmind.org/article/what-parents-should-know-about-risperdal/.

- Riquelme J, Ros S, Baeza I, et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic monitoring in children and adolescents treated with second generation antipsychotics and psychostimulants: an European consensus. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed). 2019, 12, 76–90.

- Shin JY, Roughead EE, Park BJ. Second-generation antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents: monitoring and adverse events in Korea and Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011, 47, 823–828.

- Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. Schizophrenia, "just the facts" 5. Treatment and prevention: past, present, and future. Schizophr Res. 2020, 216:44–54. PMCID: PMC7163792.

- Cueva JE, Sainz D, Ruiz P, Ravina I. Risperidone as a first-choice antipsychotic in childhood-onset schizophrenia: a long-term follow-up. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015, 24, 665–672.

- Jiang X, Shashikant B, Duan S, et al. Scientists identify source of weight gain from antipsychotics. UT Southwestern Newsroom. 2021 Sep 21. Available from: https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/newsroom/articles/year-2021/scientists-identify-source-of-weight-gai n-from-antipsychotics.html.

- Oswald DP, Sonenklar NA. Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007, 17, 348–355. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parikh H, Preeti C, Prasad P. Metabolic risks associated with atypical antipsychotics in children: a review. Acta Sci Pharm Sci. 2019, 3, 53–56.

- Bobo WV, Chandler S, Wilkes D, Smith G, et al. Antipsychotic prescribing in children: a 10-year analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2022, 73, 1292–1300. [CrossRef]

- Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 126–135.

- Tschoner A, Engl J, Laimer M, Kaser S, Rettenbacher M, Fleischhacker WW, et al. Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medication. Int J Clin Pract. 2007, 61, 1356–70.

- Sikich L, Frazier JA, McClellan J, Findling RL, Vitiello B, Ritz L, et al. Double-Blind Comparison of First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics in Early-Onset Schizophrenia and Schizo-affective Disorder: Findings From the Treatment of Early-Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders (TEOSS) Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008, 165, 1420–31.

- Chavez B, Rey JA, Chavez-Brown M. Role of Risperidone in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2006, 40, 909–16. [CrossRef]

- Calarge CA, Kuperman S, Schlechte JA, Acion L, Tansey M. Weight Gain and Metabolic Abnormalities During Extended Risperidone Treatment in Children and Adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009, 19, 101–9. [CrossRef]

- Ronsley R, Nguyen D, Davidson J, Panagiotopoulos C. Increased Risk of Obesity and Metabolic Dysregulation Following 12 Months of Second-Generation Antipsychotic Treatment in Children: A Prospective Cohort Study. Can J Psychiatry. 2015, 60, 441–50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scahill L, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Arnold LE, Feurer ID, Gadow KD, et al. Trial of risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016, 55, 415–23.

- Matera E, Moretti U, Vannacci A, Pugi A, Calugi S, Tuccori M. Risperidone in children: a focus on adverse effects. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017, 37, 302–9.

- Correll CU, Carlson HE. Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006, 45, 771–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim EY, Kim SH, Park RH, Kim H. Effects of risperidone on metabolism in children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92, 4118–25.

- Porfirio MC, Stornelli M, Masi G, Giovinazzo S, Purper-Ouakil D, Gomes De Almeida JP. Can melatonin prevent or improve metabolic side effects during antipsychotic treatments? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017, 13, 2167–74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).