Submitted:

12 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

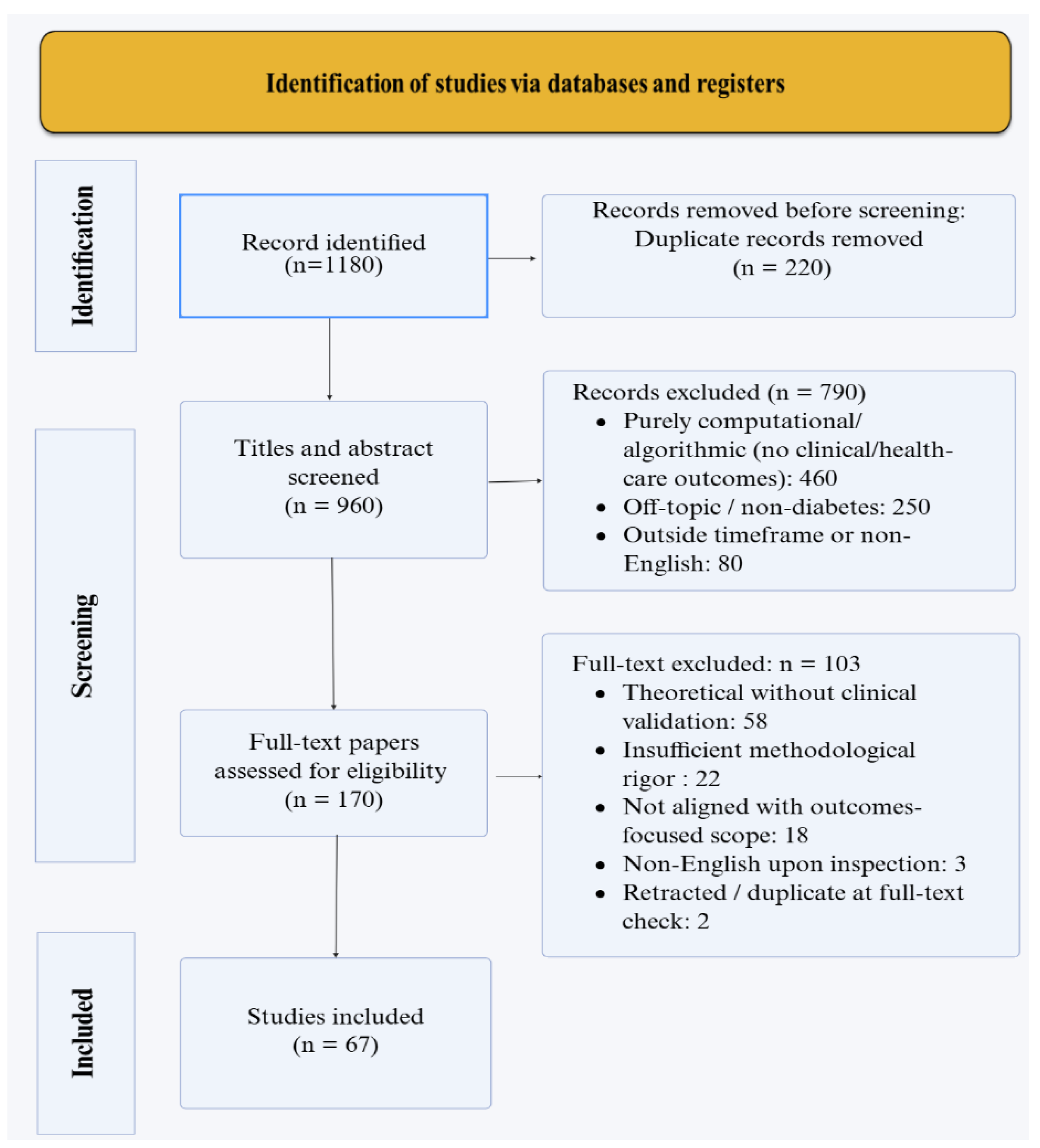

Methods

Results

Early Diagnosis and Risk Prediction

| AI Approach | Application | Data Source | Performance Metrics | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | T2DM risk prediction | Electronic health records (EHR) | AUC 0.85–0.90 | Outperformed traditional logistic regression; captured non-linear interactions in longitudinal data | Duan et al. 2025 [21] |

| Gradient Boosting Machine | T2DM incident prediction | EHR with routine clinical variables | AUC 0.80–0.90 | Consistently equaled or surpassed regression baselines across diverse populations | Lv et al. 2023 [13] |

| Deep CNN (fundus images) | DR screening | Retinal fundus photographs | Sensitivity 91%, Specificity comparable to expert graders | Autonomous diagnosis without clinician over-read; validated in primary care settings | Abràmoff et al. 2018 [17] |

| Machine Learning (wearable data) | Prediabetes/insulin resistance screening | Wrist-worn sensors + demographics + labs | AUC not specified; feasibility demonstrated | Non-invasive glucose dynamics estimation; enables scalable population screening | Huang et al. 2025 [19] |

| Gradient Boosting | Gestational diabetes risk | Clinical and anthropometric variables | AUC 0.87 | Early identification enables targeted prenatal interventions | Liu et al. 2022 [22] |

| Random Forest + ML | T2DM diagnosis and prognosis | Tailored heterogeneous feature subsets | High accuracy (specific values vary by subset) | Personalized feature selection improved model performance across populations | Navarro-Cerdán et al. 2025 [14] |

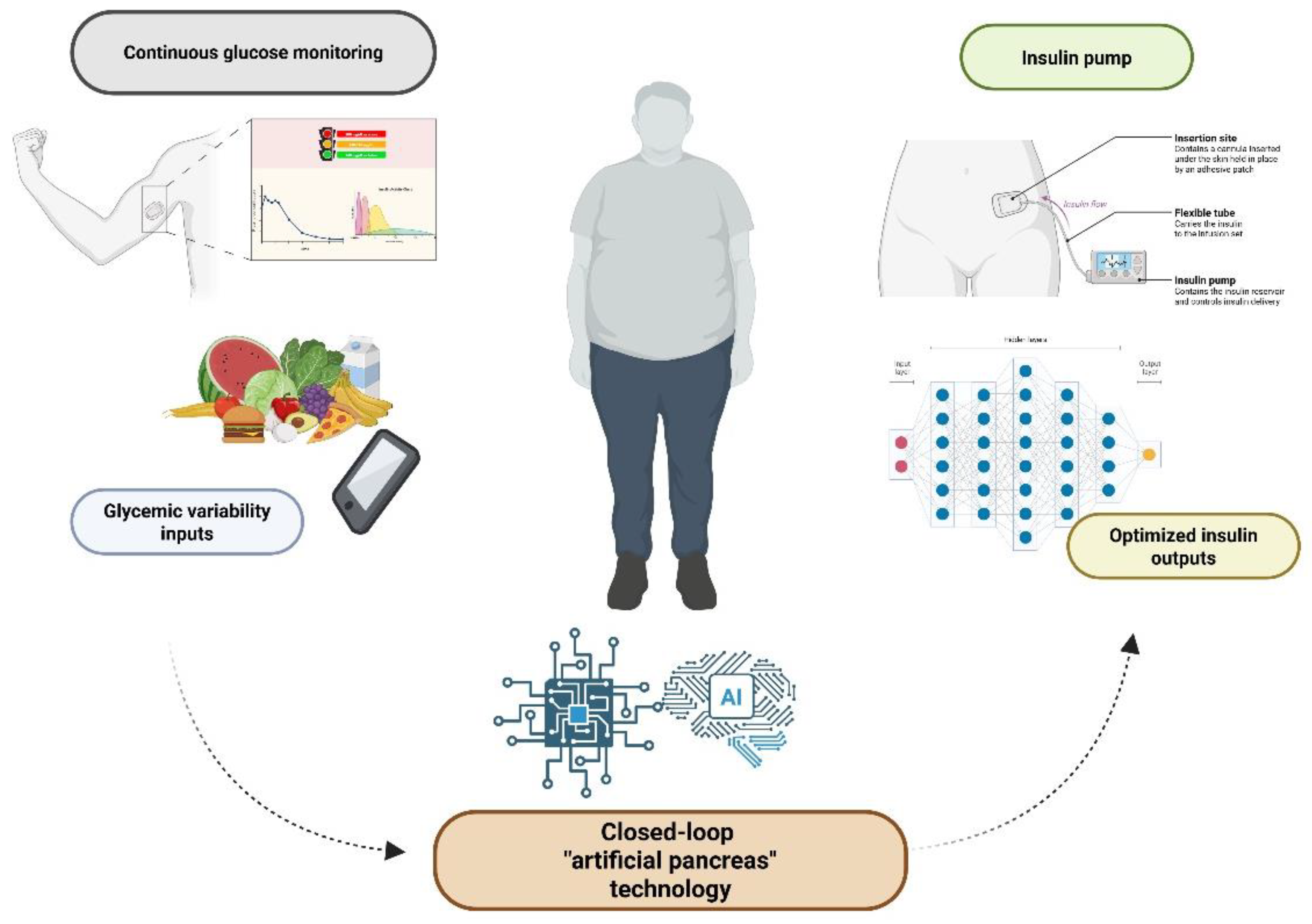

Glycemic Control and Insulin Delivery

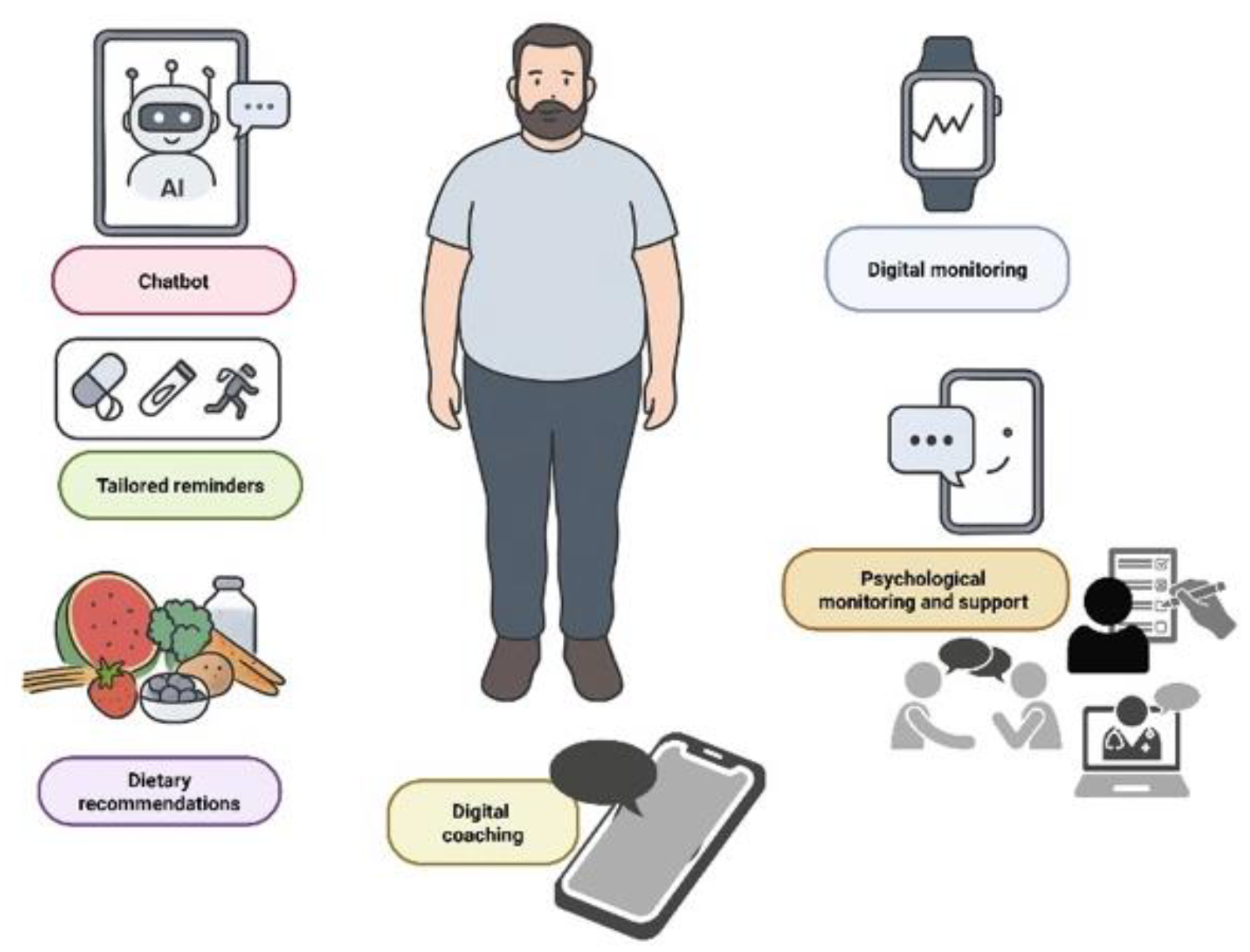

Patient Engagement and Treatment Adherence

Prediction and Prevention of Complications

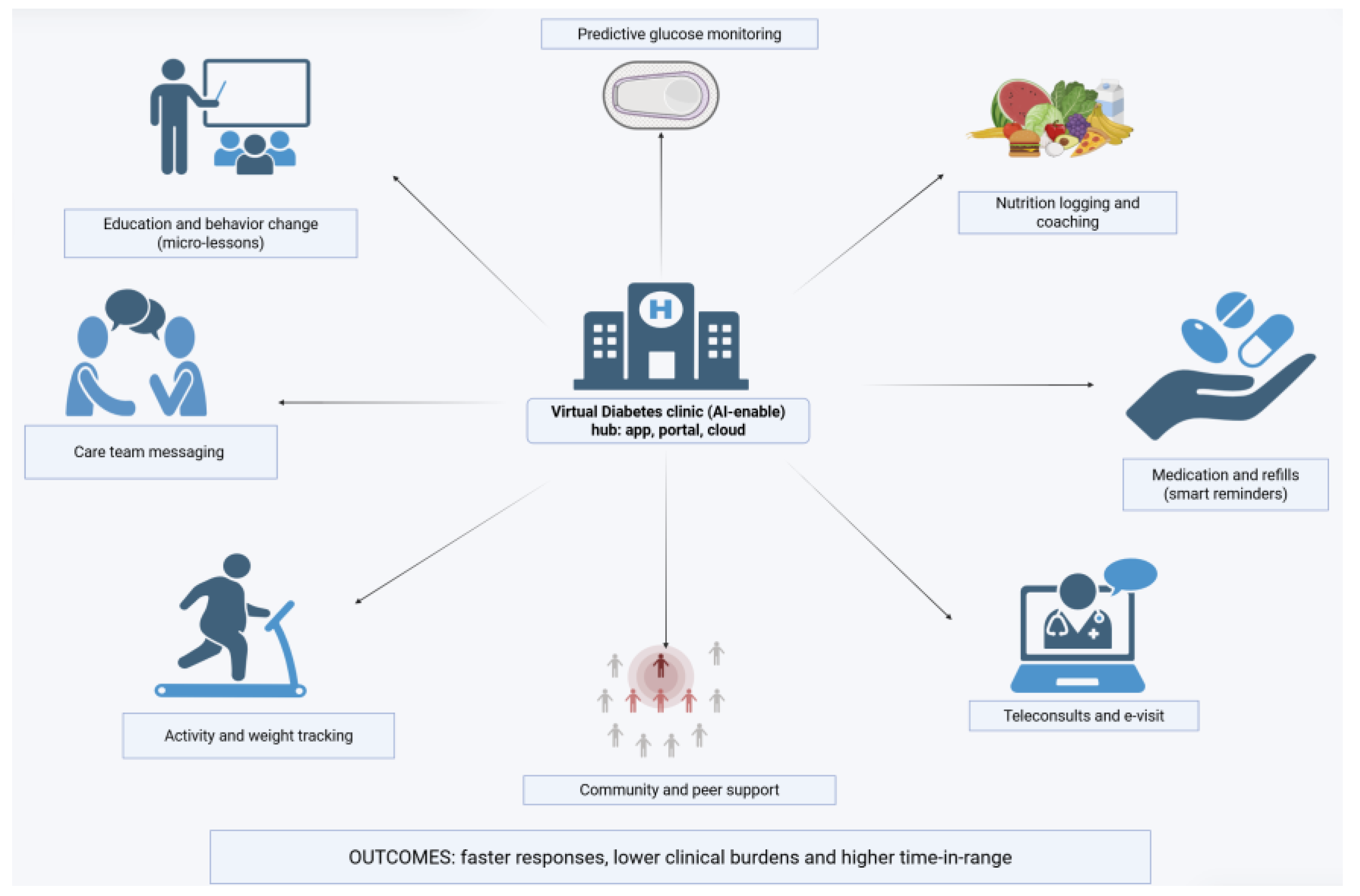

Health System Integration

Limitations, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the manuscript preparation process

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CDSS | Clinical Decision Support System |

| CGM | Continuous Glucose Monitoring |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DALY(s) | Disability-Adjusted Life Year(s) |

| DFU | Diabetic Foot Ulcer |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| DPN | Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy |

| DR | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| EASD | European Association for the Study of Diabetes |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| EHR(s) | Electronic Health Record(s) |

| FINDRISC | Finnish Diabetes Risk Score |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| GBDT / GBM | Gradient Boosted Decision Trees / Gradient Boosting Machine |

| GDM | Gestational Diabetes Mellitus |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HL7 FHIR | (Health Level Seven) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| IDF | International Diabetes Federation |

| mHealth | Mobile Health |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SANRA | Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles |

| T2D / T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes (Mellitus) |

| TIR | Time In Range |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Olanrewaju, O.A.; Sheeba, F.; Kumar, A.; Ahmad, S.; Blank, N.; Kumari, R.; Kumari, K.; Salame, T.; Khalid, A.; Yousef, N.; Varrassi, G.; Khatri, M.; Kumar, S.; Mohamad, T. Novel Therapies in Diabetes: A Comprehensive Narrative Review of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, SGLT2 Inhibitors, and Beyond. Cureus. 2023, 15, e51151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Diabetes around the world in 2024. Available at: https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/.

- Banday, M.Z.; Sameer, A.S.; Nissar, S. Pathophysiology of diabetes: An overview. Avicenna J Med. 2020, 10, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Cho, Y.; Seo, D.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Hong, S.; Suh, Y.J.; Chon, S.; Woo, J.T.; Baik, S.H.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, S.H. Impact of diabetes distress on glycemic control and diabetic complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bini, S.A. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Cognitive Computing: What Do These Terms Mean and How Will They Impact Health Care? J Arthroplasty. 2018, 33, 2358–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankwa-Mullan, I.; Rivo, M.; Sepulveda, M.; Park, Y.; Snowdon, J.; Rhee, K. Transforming Diabetes Care Through Artificial Intelligence: The Future Is Here. Popul Health Manag. 2019, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K.M.; Chan, J.; Mohan, V. Early identification of type 2 diabetes: policy should be aligned with health systems strengthening. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34, 244–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaro, A.E.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Franken, M.; Carvalho, J.A.M.; Bernardes, D.; Tuomilehto, J.; Santos, R.D. The Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC), incident diabetes and low-grade inflammation. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021, 171, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Reyes, J.; Rodríguez Garrido, D.P.; Vergara, T.A.; Aschner, P.; Fraga, C.A.; Vazquez-Fernandez, A.; Tuomilehto, J.; Gabriel, R. Finnish diabetes risk score (findrisc) for type 2 diabetes screening compared with the oral glucose tolerance test: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2025, 112480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jude, E.B.; Saluja, S.; Heald, A.; Widiatmoko, D.; Schaper, N.; Anderson, S.G. Improving Diabetes and Pre-Diabetes Detection in the UK: Insights From HbA1c Screening in an Acute Hospital's Emergency Department. Diabetes Ther. 2025, 16, 1917–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.M.; Lin, T.H.; Huang, H.T.; Yao, J.Y. Illuminating diabetes via multi-omics: Unraveling disease mechanisms and advancing personalized therapy. World J Diabetes. 2025, 16, 106218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Cui, C.; Fan, R.; Zha, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Ke, J.; Zhao, D.; Cui, Q.; Yang, L. Detection of diabetic patients in people with normal fasting glucose using machine learning. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Cerdán, J.R.; Pons-Suñer, P.; Arnal, L.; Arlandis, J.; Llobet, R.; Perez-Cortes, J.C.; Lara-Hernández, F.; Moya-Valera, C.; Quiroz-Rodriguez, M.E.; Rojo-Martinez, G.; Valdés, S.; Montanya, E.; Calle-Pascual, A.L.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Delgado, E.; Castaño, L.; García-García, A.B.; Chaves, F.J. A machine learning approach for type 2 diabetes diagnosis and prognosis using tailored heterogeneous feature subsets. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2025, 63, 2733–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deberneh, H.M.; Kim, I. Prediction of Type 2 Diabetes Based on Machine Learning Algorithm. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.; Amin, F.; Alabrah, A.; Choi, G.S.; Khan, S.; Bin Heyat, M.B.; Iqbal, M.S.; Chen, H. Diabetic retinopathy detection using adaptive deep convolutional neural networks on fundus images. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 24647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abràmoff, M.D.; Lavin, P.T.; Birch, M.; Shah, N.; Folk, J.C. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digit Med. 2018, 1, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.; Heni, M.; Tabák, A.G.; Machann, J.; Schick, F.; Randrianarisoa, E.; Hrabě de Angelis, M.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Stefan, N.; Peter, A.; Häring, H.U.; Fritsche, A. Pathophysiology-based subphenotyping of individuals at elevated risk for type 2 diabetes. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Schmelter, F.; Seitzer, C.; Martensen, L.; Otzen, H.; Piet, A.; Witt, O.; Schröder, T.; Günther, U.L.; Marshall, L.; Grzegorzek, M.; Sina, C. Digital biomarkers for interstitial glucose prediction in healthy individuals using wearables and machine learning. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 30164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Lei, L.; An, Y.; Guo, L.; Ren, L.; Chen, X. Improvement of Non-Invasive Glucose Estimation Accuracy Through Multi-Wavelength PPG. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2025, 29, 5465–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Nayan, N.M. Type 2 Diabetes Prediction Model in China: A Five-Year Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2025, 13, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Q.; He, Y.; Zou, J.; Guo, Y.; Yan, Y. Predicting the 2-Year Risk of Progression from Prediabetes to Diabetes Using Machine Learning among Chinese Elderly Adults. J Pers Med. 2022, 12, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevitt, S.; Simpson, S.; Wood, A. Artificial Pancreas Device Systems for the Closed-Loop Control of Type 1 Diabetes: What Systems Are in Development? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016, 10, 714–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenstal, R.M.; Nimri, R.; Beck, R.W.; Criego, A.; Laffel, L.; Schatz, D.; Battelino, T.; Danne, T.; Weinzimer, S.A.; Sibayan, J.; Johnson, M.L.; Bailey, R.J.; Calhoun, P.; Carlson, A.; Isganaitis, E.; Bello, R.; Albanese-O'Neill, A.; Dovc, K.; Biester, T.; Weyman, K.; Hood, K.; Phillip, M.; FLAIR Study Group. A comparison of two hybrid closed-loop systems in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes (FLAIR): a multicentre, randomised, crossover trial. Lancet. 2021, 397, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, N.; De Battista, H.; Garelli, F. Hypoglycemia prevention: PID-type controller adaptation for glucose rate limiting in Artificial Pancreas System. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 2022, 71, 103106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettoretti, M.; Cappon, G.; Facchinetti, A.; Sparacino, G. Advanced Diabetes Management Using Artificial Intelligence and Continuous Glucose Monitoring Sensors. Sensors (Basel). 2020, 20, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelino, T.; Danne, T.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Amiel, S.A.; Beck, R.; Biester, T.; Bosi, E.; Buckingham, B.A.; Cefalu, W.T.; Close, K.L.; Cobelli, C.; Dassau, E.; DeVries, J.H.; Donaghue, K.C.; Dovc, K.; Doyle FJ3rd Garg, S.; Grunberger, G.; Heller, S.; Heinemann, L.; Hirsch, I.B.; Hovorka, R.; Jia, W.; Kordonouri, O.; Kovatchev, B.; Kowalski, A.; Laffel, L.; Levine, B.; Mayorov, A.; Mathieu, C.; Murphy, H.R.; Nimri, R.; Nørgaard, K.; Parkin, C.G.; Renard, E.; Rodbard, D.; Saboo, B.; Schatz, D.; Stoner, K.; Urakami, T.; Weinzimer, S.A.; Phillip, M. Clinical Targets for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data Interpretation: Recommendations From the International Consensus on Time in Range. Diabetes Care. 2019, 42, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnanpillai, J.; Kesavadev, J.; Saboo, B. Harmony in Health: A Narrative Review Exploring the Interplay of Mind, Body, and Diabetes with a Special Emphasis on Emotional Stress. Journal of Diabetology. 2024, 15, 123–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.; Noctor, E.; Ryan, L.; van de Ven, P. The Effectiveness of a Custom AI Chatbot for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Health Literacy: Development and Evaluation Study. J Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e70131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Brinsley, J.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Matricciani, L.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; Eglitis, E.; Miatke, A.; Simpson, C.E.M.; Vandelanotte, C.; Maher, C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of chatbots on lifestyle behaviours. NPJ Digit Med. 2023, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantalone, K.M.; Xiao, H.; Bena, J.; Morrison, S.; Downie, S.; Boyd, A.M.; Shah, L.; Willis, B.; Beharry-Diaz, J.; Milinovich, A.; Joshi, S. Type 2 Diabetes Pharmacotherapy De-Escalation Through AI-Enabled Lifestyle Modifications: A Randomized Clinical Trial. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2025, 6, CAT–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shegal, M.; Hu, L.T.; Friesen, E.; Minian, N.; Maslej, M.; Rodak, T.; Whitmore, C.; Sherifali, D.; Selby, P.; Melamed, O.C. Conversational agent interventions in diabetes care: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2025, 228, 112429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijnes, M.; Kesteloo, M.; Brinkman, W.P. Reducing social diabetes distress with a conversational agent support system: a three-week technology feasibility evaluation. Front Digit Health. 2023, 5, 1149374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggiss, A.L.; Babbott, K.; Milford, Ā.; Ellett, S.; Consedine, N.; Reid, S.; Cao, N.; Cavadino, A.; Hopkins, S.; Jefferies, C.; de Bock, M.; Serlachius, A. The usability and feasibility of a self-compassion chatbot (COMPASS) for youth living with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2025, e70115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Irfan, M.; Khan, M.; Khan, M.K.; Awan, S.K.; Raza, S.S.; Adil, A.N.K.; Varrassi, G. From Glycemia to Grip: A Comprehensive Review of Musculoskeletal Complications in Diabetic Patients. Cureus. 2025, 17, e90838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Xie, M.; Liu, Q.; Li, S. Vascular complications of diabetes: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, e35285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massy, Z.A.; Lambert, O.; Metzger, M.; Sedki, M.; Chaubet, A.; Breuil, B.; Jaafar, A.; Tack, I.; Nguyen-Khoa, T.; Alves, M.; Siwy, J.; Mischak, H.; Verbeke, F.; Glorieux, G.; Herpe, Y.E.; Schanstra, J.P.; Stengel, B.; Klein, J.; CKD-REIN study group. Machine Learning-Based Urine Peptidome Analysis to Predict and Understand Mechanisms of Progression to Kidney Failure. Kidney Int Rep. 2022, 8, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liao, S.; Yang, X.; Zhao, N.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, S.; Wu, S.; Yuan, X.; Luo, Y.; Zeng, L. Identification of Potential Urine Biomarkers of Hypertensive Nephropathy for Predicting Disease Progression Based on Metabolomics and Peptidomics. J Proteome Res. 2025, 24, 4478–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; He, P.; Liu, M.; Zhou, C.; Gan, X.; Huang, Y.; Xiang, H.; Hou, F.F.; Qin, X. Large-Scale Proteomics Improve Prediction of Chronic Kidney Disease in People With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2024, 47, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.M.; Li, Y.; Xue, J.T.; Zong, G.W.; Fang, Z.Z.; Zou, L. Explainable Machine Learning-Based Prediction Model for Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2024, 2024, 8857453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tallawy, S.N.; Pergolizzi, J.V.; Vasiliu-Feltes, I.; Ahmed, R.S.; LeQuang, J.K.; El-Tallawy, H.N.; Varrassi, G.; Nagiub, M.S. Incorporation of "Artificial Intelligence" for Objective Pain Assessment: A Comprehensive Review. Pain Ther. 2024, 13, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriero, A.; Giglio, M.; Soloperto, R.; Preziosa, A.; Stefanelli, C.; Castaldo, M.; Gloria, F.; Paladini, A.; Guardamagna, V.A.; Puntillo, F. The Missing Link: Integrating Interventional Pain Management in the Era of Multimodal Oncology. Pain Ther. 2025, 14, 1223–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore, G.; Ragazzi, E.; Pegoraro, F.; Pagno, M.G.; Lapolla, A.; Piarulli, F. Artificial Intelligence Algorithm to Screen for Diabetic Neuropathy: A Pilot Study. Biomedicines. 2025, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, I.N.; Eftimov, F.; Wieske, L.; van Schaik, I.N.; Verhamme, C. Challenges in the Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy in Adults: Current Perspectives. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2024, 20, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammil, M.A.; Javid, S.; Afridi, A.K.; Siddineni, R.; Shahabi, M.; Haseeb, M.; Fariha, F.N.U.; Kumar, S.; Zaveri, S.; Nashwan, A.J. Artificial intelligence-enhanced electrocardiography for accurate diagnosis and management of cardiovascular diseases. J Electrocardiol. 2024, 83, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.S.; Tseng, Y.H.; Tsai, C.F.; Chen, J.J.; Yang, S.C.; Chiu, F.C.; Chen, Z.W.; Hwang, J.J.; Chuang, E.Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Tsai, C.T. An Artificial Intelligence-Enabled ECG Algorithm for the Prediction and Localization of Angiography-Proven Coronary Artery Disease. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.; Mohanasundaram, T.; Karunakaran, D.; Gunasekaran, M.; Tiwari, R. Physiological and Pathophysiological Aspects of Diabetic Foot Ulcer and its Treatment Strategies. Current Diabetes Reviews 19, 127–139. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017, 376, 2367–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Ray, S.; Garg, M.K.; Chowdhury, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S. The role of infrared dermal thermometry in the management of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetic Medicine. 2021, 38, e14368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, B.; Reeves, N.D.; Armstrong, D.G. Leveraging smart technologies to improve the management of diabetic foot ulcers and extend ulcer-free days in remission. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2020, 36, e3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.K.; Jongpinit, W.; Pojprapai, S.; Usaha, W.; Wattanapan, P.; Tangkanjanavelukul, P.; et al. Smart Insole-Based Plantar Pressure Analysis for Healthy and Diabetic Feet Classification: Statistical vs. Machine Learning Approaches. Technologies. 2024, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.S.W.; Pasquale, L.R.; Peng, L.; Campbell, J.P.; Lee, A.Y.; Raman, R.; Tan, G.S.W.; Schmetterer, L.; Keane, P.A.; Wong, T.Y. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, C.H.N.; Kronborg, T.; Hangaard, S.; Vestergaard, P.; Jensen, M.H. Developing an AI-Based clinical decision support system for basal insulin titration in type 2 diabetes in primary Care: A Mixed-Methods evaluation using heuristic Analysis, user Feedback, and eye tracking. Int J Med Inform. 2025, 195, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, W.R.; Ramos Silva, Y.; Soltero, E.G.; Krist, A.; Stotts, A.L. An Assessment of How Clinicians and Staff Members Use a Diabetes Artificial Intelligence Prediction Tool: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR AI. 2023, 2, e45032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutharasan, R.K.; Walradt, J. Population Health and Artificial Intelligence. JACC: Advances. 2024, 3, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.; Ahmed, M.; Basu, S.; Curtin, J.J.; Evans, B.J.; Matheny, M.E.; Nundy, S.; Sendak, M.P.; Shachar, C.; Shah, R.U.; Thadaney-Israni, S. Advancing Artificial Intelligence in Health Settings Outside the Hospital and Clinic. NAM Perspect. 2020, 2020, 10.31478/202011f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, F.; Al-Absi, H.R.H.; Yousri, N.A.; El Hajj, N.; Shah, Z. A scoping review of artificial intelligence-based methods for diabetes risk prediction. NPJ Digit Med. 2023, 6, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinta, S.V.; Wang, Z.; Palikhe, A.; Zhang, X.; Kashif, A.; Smith, M.A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W. AI-driven healthcare: Fairness in AI healthcare: A survey. PLOS Digit Health. 2025, 4, e0000864, Erratum in: PLOS Digit Health. 2025 Aug 21;4(8):e0000994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Kushniruk, A.; Borycki, E. Barriers to and Facilitators of Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Hum Factors. 2024, 11, e48633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Shariff, M.N.; Viswanath, O.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Varrassi, G. Ethical Considerations in the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Pain Medicine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025, 29, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, M.; Oakden-Rayner, L.; Beam, A.L. The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. Lancet Digit Health. 2021, 3, e745–e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolizzi JVJr LeQuang, J.A.K.; El-Tallawy, S.N.; Varrassi, G. What Clinicians Should Tell Patients About Wearable Devices and Data Privacy: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2025, 17, e81167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tong, J.; Chen, Y. Meta-Analysis and Federated Learning over Decentralized Distributed Research Networks. Annu Rev Biomed Data Sci. 2025, 8, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, B.D.; Ozyoruk, K.B.; Gelikman, D.G.; Harmon, S.A.; Türkbey, B. The future of multimodal artificial intelligence models for integrating imaging and clinical metadata: a narrative review. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2025, 31, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buess, L.; Keicher, M.; Navab, N.; Maier, A.; Tayebi Arasteh, S. From large language models to multimodal AI: a scoping review on the potential of generative AI in medicine. Biomed Eng Lett. 2025, 15, 845–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Lee, H.; Jung, H.; Kim, H. Essential properties and explanation effectiveness of explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: A systematic review. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e16110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leersum, C.M.; Maathuis, C. Human centred explainable AI decision-making in healthcare. J Respons Technol. 2025, 21, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complication | AI Technique | Data Modality | Performance | Clinical Utility | Validation Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic Nephropathy | Gradient Boosting on proteomic data | Urinary peptide patterns | AUC 0.88 | Predicts progressive kidney function loss more accurately than albuminuria or eGFR alone | Large-scale proteomic validation | Massy et al. 2022 [38] |

| Diabetic Nephropathy | Explainable ML (metabolomics) | Serum metabolite profiles | AUC 0.966 | Flags high-risk individuals before overt clinical decline; interpretable predictions | Peer-reviewed screening study | Yin et al. 2024 [41] |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | Proteomic risk scoring | Large-scale plasma proteomics | Significantly enhanced prediction over clinical variables | Protein biomarkers improve risk stratification in diabetic populations | Large cohort validation | Ye et al. 2024 [40] |

| Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (DPN) | Optimized AI algorithm | Clinical + electrophysiological data | Screening capability demonstrated | Enables targeted early intervention before symptom onset | Pilot study phase | Sartore et al. 2025 [44] |

| Cardiovascular Disease | Deep Learning on ECG | 12-lead electrocardiogram + labs | AUC 0.85 | Detects silent ischemia and localizes obstructed vessels non-invasively | Retrospective validation with angiography correlation | Muzammil et al. 2024 [46]; Huang et al. 2022 [47] |

| Diabetic Retinopathy | Deep CNN | Fundus photography | Accuracy >90%, Sensitivity/Specificity match expert graders | Point-of-care autonomous screening; reduces n |

| Challenge/Barrier | Description/Risks | Proposed Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Data heterogeneity and limited generalizability | Many AI models are developed on homogeneous, single-center or demographically narrow datasets. Without external validation, their performance may degrade in new populations. | Use multicenter datasets and external validation cohorts. Adopt domain adaptation/transfer learning techniques to adjust models to new populations. Promote federated learning across institutions to preserve data privacy while diversifying training data |

| Algorithmic bias and equity | Underrepresentation of minority, socioeconomically disadvantaged, or rare subpopulations can lead to biased predictions and unequal outcomes. | Proactively oversample or include diverse populations in training. Use fairness-aware learning or debiasing techniques. Rigorous subgroup performance reporting and audits |

| Integration and interoperability barriers | AI tools often fail to harmonize with electronic health record (EHR) systems or existing clinical workflows; clinician adoption may be hindered by usability and alert fatigue. | Develop standards-based APIs and data models (e.g. HL7 FHIR). Co-design AI interfaces with clinicians to fit workflow. Implement human-centered design and usability testing |

| Regulation, accountability and ethics | Regulatory frameworks for AI medical tools are nascent. Questions of liability, auditability, and post-market monitoring remain unresolved. | Establish audit trails and transparent performance logging. Use explainability tools and model provenance records. Engage regulators, ethicists, and stakeholders early in development |

| Patient trust, explainability and privacy | Black-box AI and concerns over data misuse reduce patient and clinician acceptance. | Integrate explainable AI (XAI) approaches to provide interpretable insights. Use privacy-enhancing technologies (e.g. differential privacy, secure aggregation). Provide clear informed consent, transparent communication |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).