Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. SWAN

2.3. Hydrodynamic Model: SOMA

2.4. Standalone SWAN Model Setup

2.4.1. Model Setup

2.4.2. Wind Input

2.4.3. Wave Conditions at the Boundary

2.4.4. Standalone SWAN Calibration and Validation

2.4.5. Experimental Design: Hydrodynamic Forcing on SWAN

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Standalone SWAN Calibration

3.2. Standalone SWAN Validation

3.3. Effects of Hydrdoynamic Forcing on Wave Propagation

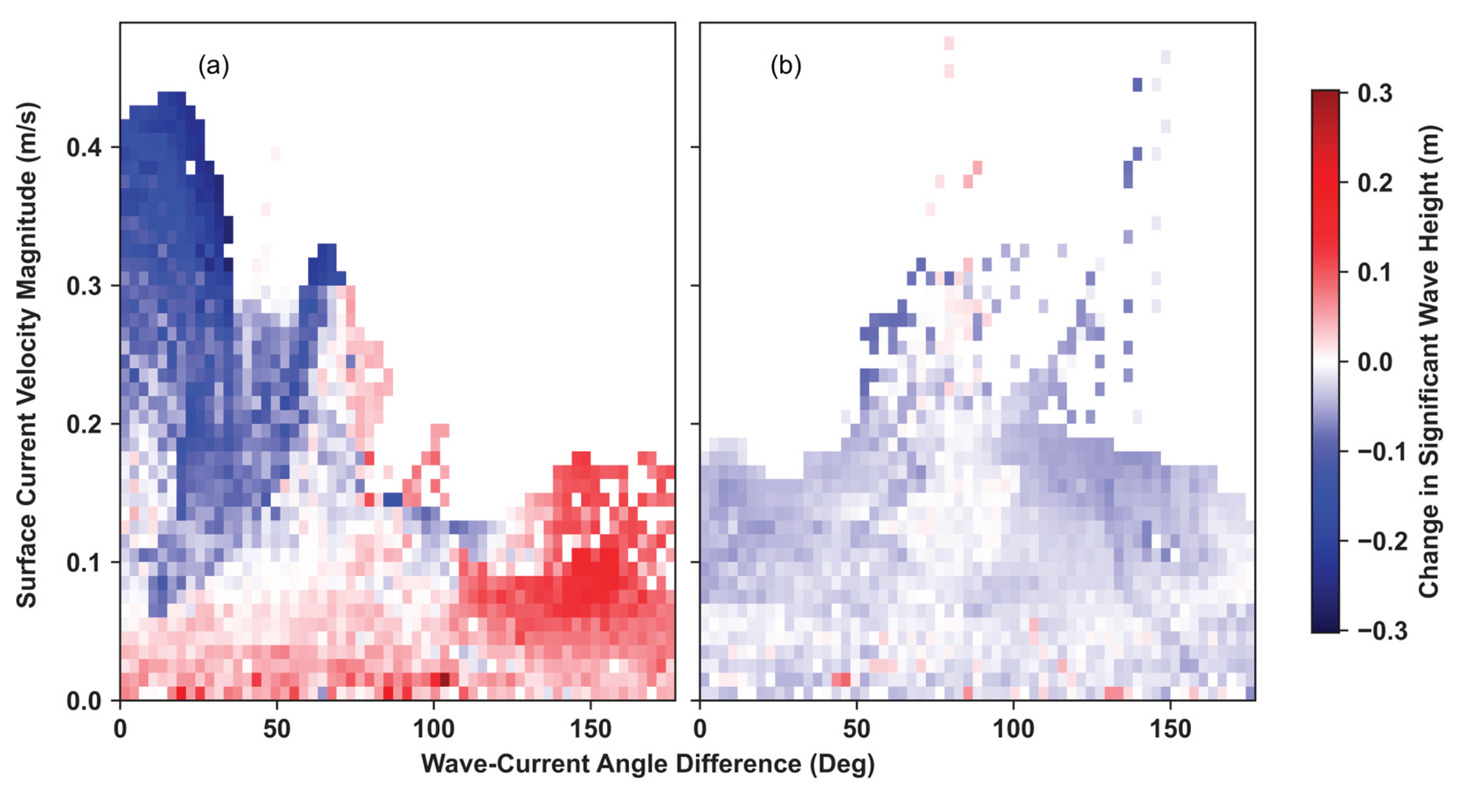

3.3.1. Waves Coming from W-SW

3.3.2. Waves Coming from E-SE

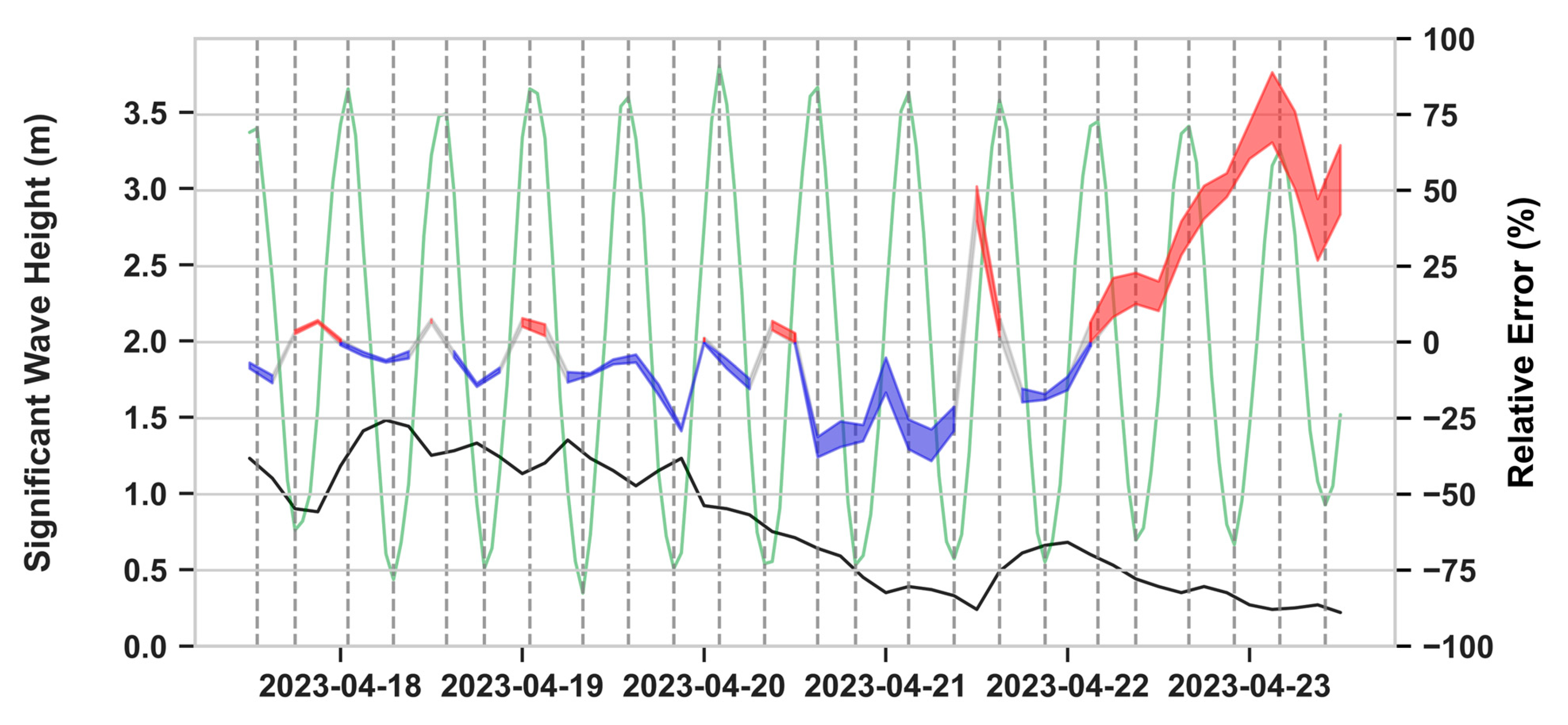

3.3.3. Wave Propagation in Shallow Waters

3.3.4. Main Findings of the Hydrodynamically Forced Simulations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Faro Ocean Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | Sines Buoy | ||||||||||

| RMSE (deg) | BIAS (deg) | MSS | R | RMSE (deg) | BIAS (deg) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | |

| Case1 | 38.067 | 1.631 | 0.893 | 0.801 | 20.933 | 0.729 | 0.957 | 0.932 | 6.857 | -1.781 | 0.985 | 0.976 |

| Case2 | 41.279 | 3.578 | 0.865 | 0.760 | 21.722 | 0.318 | 0.953 | 0.927 | 6.058 | -1.641 | 0.988 | 0.979 |

| Case3 | 31.859 | -0.904 | 0.930 | 0.866 | 20.648 | 1.005 | 0.959 | 0.932 | 7.607 | -1.882 | 0.982 | 0.972 |

| Case4 | 37.551 | 1.481 | 0.895 | 0.806 | 21.276 | 0.638 | 0.956 | 0.929 | 6.751 | -1.755 | 0.985 | 0.976 |

| Case5 | 30.589 | -2.218 | 0.936 | 0.878 | 20.394 | 1.202 | 0.961 | 0.934 | 8.232 | -1.953 | 0.979 | 0.968 |

| Case6 | 37.340 | 1.282 | 0.897 | 0.809 | 20.718 | 0.684 | 0.958 | 0.934 | 6.700 | -1.823 | 0.986 | 0.977 |

| Case7 | 41.633 | 3.735 | 0.861 | 0.755 | 21.500 | 0.249 | 0.954 | 0.930 | 5.974 | -1.684 | 0.988 | 0.979 |

| Faro Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | Sines Buoy | ||||||||||

| RMSE (s) | BIAS (s) | MSS | R | RMSE (s) | BIAS (s) | MSS | R | RMSE (s) | BIAS (s) | MSS | R | |

| Case1 | 2.812 | 1.020 | 0.780 | 0.635 | 3.955 | 1.976 | 0.702 | 0.540 | 1.948 | 0.142 | 0.869 | 0.754 |

| Case2 | 2.839 | 1.034 | 0.776 | 0.628 | 3.958 | 1.998 | 0.700 | 0.540 | 1.947 | 0.144 | 0.869 | 0.754 |

| Case3 | 2.812 | 1.026 | 0.779 | 0.634 | 3.900 | 1.917 | 0.711 | 0.553 | 1.948 | 0.142 | 0.868 | 0.753 |

| Case4 | 2.812 | 1.021 | 0.780 | 0.635 | 3.955 | 1.978 | 0.701 | 0.540 | 1.948 | 0.142 | 0.869 | 0.754 |

| Case5 | 2.769 | 0.988 | 0.787 | 0.646 | 3.888 | 1.907 | 0.714 | 0.556 | 1.948 | 0.145 | 0.868 | 0.753 |

| Case6 | 2.806 | 1.033 | 0.781 | 0.637 | 3.985 | 2.025 | 0.697 | 0.535 | 1.945 | 0.150 | 0.869 | 0.755 |

| Case7 | 2.833 | 1.047 | 0.777 | 0.631 | 4.010 | 2.053 | 0.692 | 0.529 | 1.945 | 0.151 | 0.869 | 0.754 |

| Sensitivity Test | Directional Spreading | Simulation Timeframe |

| 1 | Degree E30 N30 S30 W40 | February 2024 |

| 2 | Degree E40 N40 S40 W40 | February 2024 |

| 3 | Power E2 N2 S3 W4 | February 2024 |

| 4 | Power E1.5 N1.5 S1.5 W1.5 | February 2024 |

| 5 | Power E2 N2 S3 W3 | February 2024 |

| 6 | Power E3 N3 S3 W3 | February 2024 |

| 7 | Power E15 N15 S15 W15 | February 2024 |

| 8 | Power E2 N4 S3 W4 | February 2024 |

| 9 | Power E4 N4 S4 W4 | February 2024 |

| 10 | Power E2 N2 S2 W4 | February 2024 |

| 11 | Power E2 N2 S2 W3 | February 2024 |

| 12 | Power E2 N2 S3 W4 | November 2023 |

| 13 | Power E2 N2 S2 W4 | November 2023 |

| 14 | Power E2 N2 S2 W3 | November 2023 |

| 15 | Power E2 N2 S2 W4 | 21-10-2023 – 07-11-2023 (westerly storm) |

| 16 | Power E2 N2 S2 W4 | 08-02-2023 – 22-02-2023 (easterly storm) |

| Faro Ocean Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | Sines Buoy | ||||||||||

| Directional Spreading | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R |

| Degree E30 N30 S30 W40 | 0.404 | -0.070 | 0.955 | 0.916 | 0.370 | 0.082 | 0.958 | 0.923 | 0.421 | -0.022 | 0.978 | 0.956 |

| Degree E40 N40 S40 W40 | 0.415 | -0.027 | 0.952 | 0.908 | 0.424 | 0.154 | 0.945 | 0.907 | 0.398 | -0.025 | 0.980 | 0.960 |

| Power E2 N2 S3 W4 | 0.348 | -0.107 | 0.966 | 0.941 | 0.280 | -0.032 | 0.976 | 0.954 | 0.387 | 0.007 | 0.981 | 0.962 |

| Power E1.5 N1.5 S1.5 W1.5 | 0.390 | -0.050 | 0.958 | 0.920 | 0.374 | 0.103 | 0.957 | 0.923 | 0.401 | -0.014 | 0.980 | 0.960 |

| Power E2 N2 S3 W3 | 0.359 | -0.104 | 0.964 | 0.936 | 0.292 | -0.015 | 0.974 | 0.950 | 0.394 | 0.001 | 0.980 | 0.961 |

| Power E3 N3 S3 W3 | 0.359 | -0.102 | 0.964 | 0.936 | 0.291 | -0.013 | 0.974 | 0.950 | 0.410 | -0.001 | 0.979 | 0.959 |

| Power E15 N15 S15 W15 | 0.515 | -0.346 | 0.926 | 0.920 | 0.434 | -0.302 | 0.940 | 0.939 | 0.447 | -0.004 | 0.975 | 0.951 |

| Power E2 N4 S3 W4 | 0.349 | -0.104 | 0.966 | 0.940 | 0.279 | -0.031 | 0.976 | 0.954 | 0.414 | 0.003 | 0.979 | 0.958 |

| Power E4 N4 S4 W4 | 0.355 | -0.125 | 0.965 | 0.940 | 0.276 | -0.066 | 0.977 | 0.957 | 0.414 | 0.001 | 0.979 | 0.958 |

| Power E2 N2 S2 W4 | 0.346 | -0.072 | 0.967 | 0.939 | 0.297 | 0.026 | 0.973 | 0.948 | 0.388 | 0.009 | 0.981 | 0.962 |

| Power E2 N2 S2 W3 | 0.354 | -0.068 | 0.965 | 0.935 | 0.314 | 0.041 | 0.970 | 0.943 | 0.394 | 0.003 | 0.980 | 0.961 |

| Faro Ocean Buoy | Faro Coast Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | Sines Buoy | |||||||||||||

| Directional Spreading | RMSE | BIAS | MSS | R | RMSE | BIAS | MSS | R | RMSE | BIAS | MSS | R | RMSE | BIAS | MSS | R |

| E2 N2 S3 W4 | 0.341 | 0.058 | 0.956 | 0.93 | 0.217 | -0.145 | 0.950 | 0.947 | 0.251 | 0.054 | 0.957 | 0.942 | 0.335 | -0.024 | 0.989 | 0.982 |

| E2 N2 S2 W4 | 0.357 | 0.092 | 0.953 | 0.93 | 0.204 | -0.121 | 0.956 | 0.948 | 0.300 | 0.118 | 0.942 | 0.933 | 0.322 | -0.013 | 0.990 | 0.983 |

| E2 N2 S2 W3 | 0.368 | 0.101 | 0.950 | 0.922 | 0.183 | -0.093 | 0.964 | 0.951 | 0.328 | 0.149 | 0.931 | 0.925 | 0.328 | -0.022 | 0.990 | 0.983 |

| Level 1 SIMULATION 2023-10-21 12:00:00 - 2023-11-07 12:00:00 - WAVES COMING FROM WEST | ||||||||||||||||

| Faro Oceanic Buoy | Faro Coast Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | Sines Buoy | |||||||||||||

| RUN ID | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R |

| 1 | 0.539 | 0.426 | 0.898 | 0.922 | 0.283 | -0.127 | 0.945 | 0.933 | 0.517 | 0.417 | 0.890 | 0.927 | 0.406 | -0.046 | 0.981 | 0.967 |

| 2 | 0.540 | 0.426 | 0.898 | 0.922 | 0.284 | -0.127 | 0.945 | 0.932 | 0.516 | 0.417 | 0.890 | 0.927 | 0.406 | -0.046 | 0.981 | 0.967 |

| 3 | 0.459 | 0.339 | 0.921 | 0.927 | 0.255 | 0.011 | 0.952 | 0.919 | 0.375 | 0.250 | 0.937 | 0.935 | 0.390 | 0.019 | 0.983 | 0.968 |

| 4 | 0.461 | 0.341 | 0.921 | 0.928 | 0.256 | 0.018 | 0.952 | 0.920 | 0.381 | 0.258 | 0.935 | 0.935 | 0.394 | 0.020 | 0.983 | 0.967 |

| 5 | 0.462 | 0.343 | 0.921 | 0.928 | 0.257 | 0.020 | 0.952 | 0.921 | 0.385 | 0.262 | 0.935 | 0.936 | 0.391 | -0.165 | 0.983 | 0.975 |

| Faro Oceanic Buoy | Faro Coast Buoy | Sines Buoy | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUN ID | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R |

| 1 | 0.385 | -0.265 | 0.964 | 0.962 | 0.367 | -0.266 | 0.954 | 0.958 | 0.356 | 0.162 | 0.901 | 0.878 |

| 2 | 0.385 | -0.265 | 0.964 | 0.962 | 0.368 | -0.266 | 0.954 | 0.958 | 0.356 | 0.162 | 0.901 | 0.878 |

| 3 | 0.373 | -0.275 | 0.966 | 0.969 | 0.358 | -0.254 | 0.955 | 0.956 | 0.333 | 0.118 | 0.912 | 0.880 |

| 5 | 0.360 | -0.255 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.352 | -0.241 | 0.957 | 0.955 | 0.341 | 0.135 | 0.908 | 0.880 |

References

- Marsooli, R.; Orton, P.M.; Mellor, G.; Georgas, N.; Blumberg, A.F. A Coupled Circulation-Wave Model for Numerical Simulation of Storm Tides and Waves. J Atmos Ocean Technol 2017, 34, 1449–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino, C.; Dabrowski, T.; Dias, F. Current Interaction in Large-Scale Wave Models with an Application to Ireland. Cont Shelf Res 2022, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.A.; Rautenbach, C. Toward Operational Wave-Current Interactions Over the Agulhas Current System. J Geophys Res Oceans 2020, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causio, S.; Ciliberti, S.A.; Clementi, E.; Coppini, G.; Lionello, P. A Modelling Approach for the Assessment of Wave-Currents Interaction in the Black Sea. J Mar Sci Eng 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marechal, G.; Ardhuin, F. Surface Currents and Significant Wave Height Gradients: Matching Numerical Models and High-Resolution Altimeter Wave Heights in the Agulhas Current Region. J Geophys Res Oceans 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causio, S.; Ciliberti, S.A.; Clementi, E.; Coppini, G.; Lionello, P. A Modelling Approach for the Assessment of Wave-Currents Interaction in the Black Sea. J Mar Sci Eng 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementi, E.; Oddo, P.; Drudi, M.; Pinardi, N.; Korres, G.; Grandi, A. Coupling Hydrodynamic and Wave Models: First Step and Sensitivity Experiments in the Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Dyn 2017, 67, 1293–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.W.E.; Wang, X.H.; Salcedo-Castro, J.; Ritchie, E.A. Influence of Wave–Current Interaction on a Cyclone-Induced Storm Surge Event in the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna Delta: Part 1—Effects on Water Level. J Mar Sci Eng 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.A.; Rautenbach, C. Toward Operational Wave-Current Interactions Over the Agulhas Current System. J Geophys Res Oceans 2020, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longuet-Higgins, M.S.; Stewart, R.W. Changes in the Form of Short Gravity Waves on Long Waves and Tidal Currents. J Fluid Mech 1960, 8, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Prandle, D. Some Observations of Wave-Current Interaction; 1999; Vol. 37;

- Kumar, A.; Hayatdavoodi, M. On Wave–Current Interaction in Deep and Finite Water Depths. J Ocean Eng Mar Energy 2023, 9, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Elahi, M.W.E. Influence of Wave–Current Interaction on a Cyclone-Induced Storm-Surge Event in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Delta: Part 2—Effects on Wave. J Mar Sci Eng 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruwatari, A.; Ingram, D.M.; Cradden, L. Wave-Current Interaction Effects on Marine Energy Converters. Ocean Engineering 2013, 73, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, J.C.; Tanaka, S.; Westerink, J.J.; Dawson, C.N.; Luettich, R.A.; Zijlema, M.; Holthuijsen, L.H.; Smith, J.M.; Westerink, L.G.; Westerink, H.J. Performance of the Unstructured-Mesh, SWAN+ ADCIRC Model in Computing Hurricane Waves and Surge. J Sci Comput 2012, 52, 468–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Bento, A.R.; Martinho, P.; Guedes Soares, C. High Resolution Local Wave Energy Modelling in the Iberian Peninsula. Energy 2015, 91, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, L.; Pilar, P.; Guedes Soares, C. Hindcast of the Wave Conditions along the West Iberian Coast. Coastal Engineering 2008, 55, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, J.; Oliveira, S.; Moura, D.; Ferreira, Ó. Nearshore Hydrodynamics at Pocket Beaches with Contrasting Wave Exposure in Southern Portugal. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 2018, 204, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, P.; Barton, E.D.; Dubert, J.; Oliveira, P.B.; Peliz, Á.; da Silva, J.C.B.; Santos, A.M.P. Physical Oceanography of the Western Iberia Ecosystem: Latest Views and Challenges. Prog Oceanogr 2007, 74, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peliz, Á.; Dubert, J.; Santos, A.M.P.; Oliveira, P.B.; Le Cann, B. Winter Upper Ocean Circulation in the Western Iberian Basin - Fronts, Eddies and Poleward Flows: An Overview. Deep Sea Res 1 Oceanogr Res Pap 2005, 52, 621–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, L.; Janeiro, J.; Martins, F. Baseline Climatology of the Canary Current Upwelling System and Evolution of Sea Surface Temperature. Remote Sens (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Salgado, X.A.; Figueiras, F.G.; Perez, F.F.; Groom, S.; Nogueira, E.; Borges, A. V.; Chou, L.; Castro, C.G.; Moncoiffé, G.; Rios, A.F.; et al. The Portugal Coastal Counter Current off NW Spain: New Insights on Its Biogeochemical Variability. Prog Oceanogr 2003, 56, 281–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, P.; Barton, E.D. Mesoscale Patterns in the Cape São Vicente (Iberian Peninsula) Upwelling Region. J Geophys Res Oceans 2002, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Ó.; Kupfer, S.; Costas, S. Implications of Sea-Level Rise for Overwash Enhancement at South Portugal. Natural Hazards 2021, 109, 2221–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; Fernandes, C.; Barroqueiro, T.; Agostinho, P.; Martins, ) N; Alonso-Martirena, A. Extreme Wave Height Events in Algarve (Portugal): Comparison between HF Radar Systems and Wave Buoys; 2018;

- Mota, P.; Pinto, J.P. Wave Energy Potential along the Western Portuguese Coast. Renew Energy 2014, 71, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Ó.; Matias, A.; Pacheco, A. The East Coast of Algarve: A Barrier Island Dominated Coast. Thalassas 2016, 32, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, N.; Ris, R.C.; Holthuijsen, L.H. A Third-Generation Wave Model for Coastal Regions, Part I, Model Description and Validation A Third-Generation Wave Model for Coastal Regions 1. Model Description and Validation; 1999; Vol. 894;

- Booij, N.; Holthuijsen, L.H.; Ris, R.C. THE “SWAN” WAVE MODEL FOR SHALLOW WATER; 1996;

- Rogers, E.W.; Babanin, A. V.; Wang, D.W. Observation-Consistent Input and Whitecapping Dissipation in a Model for Wind-Generated Surface Waves: Description and Simple Calculations. J Atmos Ocean Technol 2012, 29, 1329–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeiro, J.; Neves, A.; Martins, F.; Relvas, P. Integrating Technologies for Oil Spill Response in the SW Iberian Coast. Journal of Marine Systems 2017, 173, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Leitão, P.; Silva, A.; Neves, R. 3D Modelling in the Sado Estuary Using a New Generic Vertical Discretization Approach; 2001;

- Braunschweig, F.; Leitao, P.C.; Fernandes, L.; Pina, P.; Neves, R.J.J. The Object Oriented Design of the Integrated Water Modelling System MOHID; 2004;

- Mendonça, F.; Martins, F.; Janeiro, J. SMS-Coastal, a New Python Tool to Manage MOHID-Based Coastal Operational Models. J Mar Sci Eng 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallos, G.; Nickovic, S.; Papadopoulos, A.; Jovic, D.; Kakaliagou, O.; Misirlis, N.; Boukas, L.; Mitikou, N.; Sakellaridis, G.; Papageorgiou, J.; et al. The Regional Weather Forecasting System SKIRON: An Overview. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Symposium on Regional Weather Prediction on Parallel Computer Environments; Athens, Greece, October 1997; pp. 109–122.

- Toledano, C.; Ghantous, M.; Lorente, P.; Dalphinet, A.; Aouf, L.; Sotillo, M.G. Impacts of an Altimetric Wave Data Assimilation Scheme and Currents-Wave Coupling in an Operational Wave System: The New Copernicus Marine IBI Wave Forecast Service. J Mar Sci Eng 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, B.; Aouf, L.; Dalphinet, A.; Louis, L.; Alonso, A.; Garcia, M.; Valdecasas, J.M.; Ciliberti, S.; Aznar, R.; Sotillo, M.G. Atlantic-Iberian Biscay Irish-IBI Production Centre IBI_ANALYSISFORECAST_WAV_005_005;

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.; Chen, G.; Yang, J. Assessing the Performance of SWAN Model for Wave Simulations in the Bay of Bengal. Ocean Engineering 2023, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.L.; Rogers, W.E.; Siqueira, S.; Gay, P.; Wood, K. A Cost-Benefit Analysis of SWAN with Source Term Package ST6; 2018;

- SWAN Team Swanuse. 2020.

- Cavaleri, L.; Bertotti, L. The Miami 1981 Wave Model Intercomparison Test. Il Nuovo Cimento C 1982, 5, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardhuin, F.; Rogers, E.; Babanin, A. V.; Filipot, J.F.; Magne, R.; Roland, A.; van der Westhuysen, A.; Queffeulou, P.; Lefevre, J.M.; Aouf, L.; et al. Semiempirical Dissipation Source Functions for Ocean Waves. Part I: Definition, Calibration, and Validation. J Phys Oceanogr 2010, 40, 1917–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieger, S.; Babanin, A. V.; Erick Rogers, W.; Young, I.R. Observation-Based Source Terms in the Third-Generation Wave Model WAVEWATCH. Ocean Model (Oxf) 2015, 96, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehde, H.; Schuckmann, K. V; Pouliquen, S.; Grouazel, A.; Bartolome, T.; Tintore, J.; De, M.; Alonso-Munoyerro, A.; Carval, T.; Racapé, V. In Situ TAC Multiparameter Products: INSITU_GLO_PHYBGCWAV_DISCRETE_MYNRT_013_030 INSITU_ARC_PHYBGCWAV_DISCRETE_MYNRT_013_031 INSITU_BAL_PHYBGCWAV_DISCRETE_MYNRT_013_032 INSITU_IBI_PHYBGCWAV_DISCRETE_MYNRT_013_033 INSITU_BLK_PHYBGCWAV_DISCRETE_MYNRT_013_034 INSITU_MED_PHYBGCWAV_DISCRETE_MYNRT_013_035 INSITU_NWS_PHYBGCWAV_DISCRETE_MYNRT_013_036 Issue: 2.4; 2024;

- O’Donncha, F.; Hartnett, M.; Nash, S.; Ren, L.; Ragnoli, E. Characterizing Observed Circulation Patterns within a Bay Using HF Radar and Numerical Model Simulations. Journal of Marine Systems 2015, 142, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.I. ON THE VALIDATION OF MODELS. Phys Geogr 1981, 2, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, A.G.; Ramos, V.; Amarouche, K.; Rosa Santos, P.; das Neves, L.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Assessing the Impact of Wave Model Calibration in the Uncertainty of Wave Energy Estimation. Renew Energy 2023, 212, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, B.; Ayat, B. Performance Evaluation of SWAN ST6 Physics Forced by ERA5 Wind Fields for Wave Prediction in an Enclosed Basin. Ocean Engineering 2021, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiega, P.; Zalewska, T.; Struzik, P. Application of SWAN Model for Wave Forecasting in the Southern Baltic Sea Supplemented with Measurement and Satellite Data. Environmental Modelling and Software 2023, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ST6 Physics | SSWELL | |

| Case 1 | GEN3 ST6 4.7E-7 6.6E-6 4.0 4.0 UP HWANG VECTAU U10PROXY 28.0 AGROW | ARDHUIN 1.2 |

| Case 2 | GEN3 ST6 4.7E-7 6.6E-6 4.0 4.0 UP FAN VECTAU U10PROXY 28.0 AGROW | ARDHUIN 1.2 |

| Case 3 | GEN3 ST6 2.8E-6 3.5E-5 4.0 4.0 UP HWANG VECTAU U10PROXY 32.0 AGROW | ARDHUIN 1.2 |

| Case 4 | GEN3 ST6 2.8E-6 3.5E-5 4.0 4.0 UP HWANG VECTAU U10PROXY 32.0 DEBIAS 0.89 AGROW | ARDHUIN 1.2 |

| Case 5 | GEN3 ST6 6.5E-6 8.5E-5 4.0 4.0 UP HWANG VECTAU U10PROXY 35.0 AGROW | ARDHUIN 1.2 |

| Case 6 | GEN3 ST6 4.7E-7 6.6E-6 4.0 4.0 UP HWANG VECTAU U10PROXY 28.0 AGROW | ZIEGER 0.00025 |

| Case 7 | GEN3 ST6 4.7E-7 6.6E-6 4.0 4.0 UP FAN VECTAU U10PROXY 28.0 AGROW | ZIEGER 0.00025 |

| Buoy | Location | Depth |

| Faro Ocean | 36.398°N, 8.068°W | 1334 m |

| Cadiz | 36.490°N, 6.960°W | 450 m |

| Sines | 37.675°N, 9.725°W | 1768 m |

| Faro Coast | 36.905°N, 7.898°W | 90 m |

| Armona | 37.011°N, 7.741°W | 21 m |

| Run | Hydrodynamic Input |

| 1 | No Hydrodynamic Input |

| 2 | SOMA Water Level Only |

| 3 | SOMA Surface Currents and Water Level |

| 4 | SOMA Currents (10 m Depth-Averaged Velocity) and Water Level |

| 5 | SOMA Currents (20 m Depth-Averaged Velocity) and Water Level |

| 6 | SOMA Currents (Full Water Column Depth-Averaged Velocity) and Water Level |

| Experiment | Timeframe | Dominant Wave Direction | Model Test |

| 1 | 2024-02-01 - 2024-02-29 | Westerly | Standalone SWAN calibration |

| 2 | 2023-11-01 - 2023-11-30 | Westerly | Standalone SWAN validation |

| 3 | 2023-10-21 - 2023-11-07 | Westerly | Hydrodynamic forcing |

| 4 | 2023-02-08 - 2023-02-22 | Easterly | Hydrodynamic forcing |

| 5 | 2023-04-17 - 2023-04-23 | Easterly | Hydrodynamic forcing (shallow waters) |

| Faro Ocean Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | Sines Buoy | ||||||||||

| RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | |

| Case 1 | 0.368 | -0.014 | 0.962 | 0.927 | 0.368 | 0.131 | 0.958 | 0.929 | 0.402 | 0.008 | 0.979 | 0.959 |

| Case 2 | 0.379 | -0.067 | 0.959 | 0.924 | 0.361 | 0.072 | 0.958 | 0.922 | 0.394 | -0.032 | 0.980 | 0.961 |

| Case 3 | 0.369 | 0.011 | 0.962 | 0.927 | 0.381 | 0.151 | 0.956 | 0.928 | 0.404 | 0.018 | 0.979 | 0.959 |

| Case 4 | 0.370 | -0.035 | 0.961 | 0.926 | 0.365 | 0.102 | 0.958 | 0.925 | 0.395 | -0.014 | 0.980 | 0.960 |

| Case 5 | 0.375 | 0.036 | 0.961 | 0.925 | 0.396 | 0.172 | 0.953 | 0.926 | 0.409 | 0.030 | 0.979 | 0.958 |

| Case 6 | 0.366 | -0.001 | 0.963 | 0.928 | 0.374 | 0.138 | 0.958 | 0.929 | 0.404 | 0.021 | 0.979 | 0.959 |

| Case 7 | 0.374 | -0.056 | 0.960 | 0.925 | 0.363 | 0.078 | 0.958 | 0.922 | 0.394 | -0.020 | 0.980 | 0.961 |

| Significant Wave Height (m) | ||||

| RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | |

| Faro Oceanic Buoy | 0.400 | 0.173 | 0.942 | 0.921 |

| Faro Coast Buoy | 0.156 | -0.016 | 0.973 | 0.951 |

| Cadiz Buoy | 0.407 | 0.255 | 0.900 | 0.914 |

| Sines Buoy | 0.335 | 0.016 | 0.989 | 0.983 |

| Mean Wave Direction (deg) | ||||

| RMSE (deg) | BIAS (deg) | MSS | R | |

| Faro Oceanic Buoy | 20.099 | -6.792 | 0.957 | 0.866 |

| Faro Coast Buoy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cadiz Buoy | 21.848 | -4.131 | 0.969 | 0.856 |

| Sines Buoy | 8.065 | -0.088 | 0.985 | 0.922 |

| Peak Period (s) | ||||

| RMSE (s) | BIAS (s) | MSS | R | |

| Faro Oceanic Buoy | 3.127 | 1.101 | 0.757 | 0.607 |

| Faro Coast Buoy | 2.878 | 0.559 | 0.806 | 0.670 |

| Cadiz Buoy | 3.522 | 1.546 | 0.760 | 0.625 |

| Sines Buoy | 1.554 | -0.093 | 0.900 | 0.813 |

| 2023-10-21 12:00:00 - 2023-11-07 12:00:00 – WESTERLY WAVES | ||||||||||||||||

| Faro Oceanic Buoy | Faro Coast Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | Sines Buoy | |||||||||||||

| RUN ID | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R |

| 1 | 0.526 | 0.407 | 0.905 | 0.926 | 0.246 | -0.025 | 0.957 | 0.933 | 0.594 | 0.502 | 0.862 | 0.922 | 0.427 | -0.112 | 0.979 | 0.966 |

| 2 | 0.525 | 0.407 | 0.905 | 0.926 | 0.242 | -0.034 | 0.958 | 0.933 | 0.593 | 0.501 | 0.862 | 0.921 | 0.421 | -0.111 | 0.980 | 0.967 |

| 3 | 0.472 | 0.356 | 0.920 | 0.931 | 0.256 | 0.058 | 0.952 | 0.923 | 0.430 | 0.323 | 0.919 | 0.933 | 0.398 | -0.048 | 0.982 | 0.967 |

| 4 | 0.474 | 0.358 | 0.919 | 0.931 | 0.258 | 0.065 | 0.951 | 0.924 | 0.436 | 0.330 | 0.918 | 0.934 | 0.402 | -0.047 | 0.982 | 0.967 |

| 5 | 0.475 | 0.360 | 0.919 | 0.931 | 0.258 | 0.064 | 0.951 | 0.925 | 0.439 | 0.334 | 0.917 | 0.934 | 0.402 | -0.048 | 0.982 | 0.967 |

| 6 | 0.569 | 0.455 | 0.892 | 0.924 | 0.252 | 0.005 | 0.956 | 0.934 | 0.580 | 0.485 | 0.868 | 0.922 | 0.398 | -0.026 | 0.982 | 0.968 |

| CMEMS MODEL | 0.365 | 0.125 | 0.940 | 0.902 | 0.186 | 0.001 | 0.966 | 0.943 | 0.265 | 0.104 | 0.959 | 0.939 | 0.391 | -0.165 | 0.983 | 0.975 |

| 2023-02-08 12:00:00 - 2023-02-22 12:00:00 – EASTERLY WAVES | ||||||||||||

| Faro Oceanic Buoy | Faro Coast Buoy | Sines Buoy | ||||||||||

| RUN ID | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R |

| 1 | 0.338 | -0.205 | 0.972 | 0.964 | 0.305 | -0.161 | 0.972 | 0.964 | 0.373 | 0.203 | 0.890 | 0.874 |

| 2 | 0.343 | -0.221 | 0.971 | 0.966 | 0.326 | -0.217 | 0.967 | 0.964 | 0.364 | 0.184 | 0.894 | 0.872 |

| 3 | 0.325 | -0.210 | 0.974 | 0.970 | 0.290 | -0.143 | 0.974 | 0.962 | 0.352 | 0.170 | 0.900 | 0.874 |

| 4 | 0.318 | -0.196 | 0.975 | 0.970 | 0.288 | -0.133 | 0.974 | 0.962 | 0.360 | 0.182 | 0.896 | 0.874 |

| 5 | 0.318 | -0.195 | 0.975 | 0.970 | 0.289 | -0.133 | 0.974 | 0.962 | 0.360 | 0.183 | 0.896 | 0.874 |

| 6 | 0.411 | -0.302 | 0.958 | 0.961 | 0.297 | -0.156 | 0.972 | 0.963 | 0.367 | 0.192 | 0.893 | 0.874 |

| CMEMS MODEL | 0.427 | -0.312 | 0.947 | 0.968 | 0.379 | -0.293 | 0.945 | 0.970 | 0.334 | 0.209 | 0.906 | 0.899 |

| Level 1 SIMULATION 2023-04-17T12:00 - 2023-04-23T12:00 | ||||||||||||

| Armona Buoy | Faro Coast Buoy | Cadiz Buoy | ||||||||||

| Run | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R | RMSE (m) | BIAS (m) | MSS | R |

| 1 | 0.124 | -0.039 | 0.973 | 0.957 | 0.148 | -0.083 | 0.944 | 0.925 | 0.137 | 0.035 | 0.972 | 0.957 |

| 2 | 0.125 | -0.023 | 0.972 | 0.954 | 0.144 | -0.076 | 0.947 | 0.925 | 0.137 | 0.035 | 0.972 | 0.957 |

| 3 | 0.123 | -0.015 | 0.972 | 0.955 | 0.134 | -0.068 | 0.952 | 0.929 | 0.129 | 0.015 | 0.976 | 0.958 |

| 4 | 0.126 | -0.015 | 0.971 | 0.954 | 0.133 | -0.065 | 0.952 | 0.928 | 0.130 | 0.022 | 0.976 | 0.957 |

| 5 | 0.125 | -0.016 | 0.971 | 0.954 | 0.134 | -0.066 | 0.952 | 0.928 | 0.130 | 0.023 | 0.976 | 0.957 |

| 6 | 0.124 | -0.019 | 0.972 | 0.954 | 0.135 | -0.079 | 0.952 | 0.938 | 0.141 | 0.051 | 0.971 | 0.956 |

| CMEMS MODEL | 0.153 | -0.010 | 0.950 | 0.945 | 0.163 | -0.059 | 0.898 | 0.899 | 0.217 | -0.151 | 0.923 | 0.955 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).