Abstract

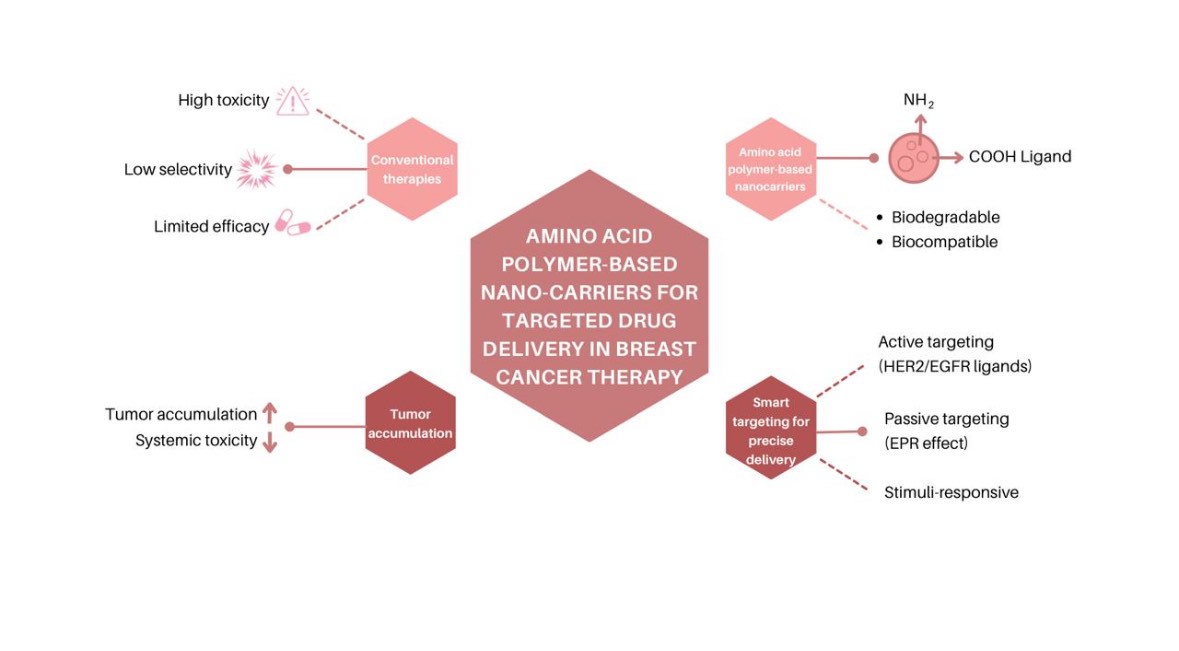

Breast cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality among women worldwide, despite remarkable advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Conventional treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy continue to face major challenges, including systemic toxicity, adverse side effects, and limited efficacy in advanced stages. Recent developments in nanomedicine have introduced amino acid polymer-based nano-carriers as innovative and promising platforms for targeted drug delivery in breast cancer therapy. These nano-carriers offer superior biocompatibility, controlled and sustained drug release, improved physicochemical stability, and selective targeting of tumor tissues, thereby minimizing off-target toxicity. This review comprehensively discusses the latest progress in amino acid polymer-based nano-carriers, with emphasis on their structural design, drug-loading mechanisms, tumor microenvironment responsiveness, and ligand-mediated targeting strategies. Moreover, it highlights current limitations, translational challenges, and research gaps that need to be addressed to achieve successful clinical implementation. Overall, amino acid polymer-based nano-carriers hold significant potential to revolutionize breast cancer treatment by enhancing therapeutic precision, improving patient outcomes, and contributing to the next generation of personalized nanomedicine.

1. Introduction

Cancer represents a major societal, public health, and economic challenge of the twenty-first century. It accounts for approximately one in every six deaths (16.8%) and nearly one in four deaths (22.8%) due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) worldwide. Furthermore, cancer is responsible for 30.3% of premature deaths caused by NCDs among individuals aged 30 to 69 years and ranks among the top three leading causes of death in this age group across 177 out of 183 countries (Bray et al., 2021).

Beyond its negative impact on life expectancy, cancer imposes substantial economic and societal burdens that vary in magnitude depending on the cancer type, geographic region, and sex (Chen et al., 2023). A recent study highlighted the disproportionate impact of cancer-related mortality on women, estimating that approximately one million children lost their mothers to cancer in 2020, with nearly half of these maternal deaths attributed to either breast cancer or cervical cancer (Guida et al., 2022).

According to the World Health Organization, malignant tumors constitute the greatest health burden among women globally, accounting for an estimated 107.8 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), of which 19.6 million DALYs are attributable specifically to breast cancer (World Health Organization, 2018). Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer among women worldwide, with 2.26 million new cases recorded [95% UI: 2.24–2.79 million] in 2020 (Ferlay, 2020). In the United States alone, breast cancer is projected to represent 29% of all new cancer cases among women (DeSantis et al., 2016). Moreover, data from GLOBOCAN 2018 indicate a strong positive correlation between age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR) of breast cancer and the Human Development Index (HDI) (Sharma, 2021) .

Despite advancements in early detection and therapeutic approaches, breast cancer remains significant global health concern Persistent challenges include late-stage diagnosis, genetic predisposition, and limited access to healthcare services in under-resourced areas Current treatment modalities follow a multidisciplinary approach, including surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy), radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy, depending on the tumor type and stage Although these interventions have substantially improved patient outcomes, they are not without limitations Chemotherapy and radiotherapy often induce debilitating side effects such as nausea and fatigue, while surgical procedures may carry risks of tissue damage and postoperative complications In addition, traditional therapies may show limited efficacy in advanced or metastatic cases and may inadvertently promote cancer cell resistance. Moreover, their invasive nature and high financial cost can significantly impact patients’ overall health and financial stability(Chaudhari, Patel and Kumar, 2024). These challenges underscore the need for developing more effective, targeted, and less toxic therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

To better understand the limitations of current cancer treatments, particularly chemotherapy, it is essential to examine its systemic nature in detail.

Chemotherapy remains one of the most widely used therapeutic strategies for a broad spectrum of cancer types. Most chemotherapeutic agents function as cytotoxic drugs that target rapidly dividing cells, exploiting the hallmark characteristic of cancer cells—their uncontrolled proliferation due to evasion of cell cycle checkpoints However, certain normal cells, including hematopoietic cells, gastrointestinal lining cells, and skin cells, also exhibit high proliferative activity. Consequently, systemic administration of chemotherapy often results in unintended damage to these healthy, rapidly dividing cells. Furthermore, the systemic distribution of chemotherapeutic agents necessitates high dosages to achieve therapeutic efficacy. This, combined with rapid drug clearance and widespread dissemination throughout various tissues, frequently leads to significant toxicities and adverse side effects. The severity of these effects varies depending on factors such as cancer type, specific drug, dosage, and individual patient genetics. Targeted drug delivery aims to overcome these limitations by directing therapeutic agents specifically to diseased tissues, particular cell types, or even subcellular compartments, based on the nature of the drug and disease ((Salari et al., 2021). Nanoparticles have emerged as promising carriers in such targeted delivery systems, demonstrating remarkable efficacy in enhancing drug accumulation within cancer cells, as supported by multiple studies (Wu et al., 2014; Qi et al., 2015; Zhuang Y, 2016; Yang et al., 2017).

These nano-carriers have effectively addressed several drawbacks associated with conventional systemic drug delivery in cancer therapy. Benefits include improved drug stability, sustained and controlled release, reduced systemic toxicity, enhanced penetration of biological barriers, and increased drug concentration at target sites. Consequently, nanoparticle-based targeted delivery systems are increasingly recognized as efficient and promising platforms for cancer treatment (Salari et al., 2021). These limitations underscore the urgent need for innovative strategies that enhance treatment specificity, minimize adverse effects, and improve patient outcomes—objectives that nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems aim to address.

Driven by extensive preclinical and clinical evidence, nano medicine has emerged as a powerful tool for early cancer detection and treatment. Various types of nano medicines have been explored in cancer therapy, including viral vectors, drug conjugates, lipid-based nano-carriers, and polymeric nanoparticles These nano-carriers offer several advantages, such as enhanced water solubility, improved chemical stability, and increased bioavailability of the delivered drugs. Furthermore, they protect anticancer compounds from biological degradation and can cross physiological barriers such as the blood-brain barrier to reach targeted sites, Nano medicine has repeatedly demonstrated its efficacy through multiple advantages—most notably, the selective targeting of cancer cells via appropriate ligands. This specificity not only enhances treatment outcomes but also minimizes damage to healthy tissues. Given the growing body of supporting evidence, nano medicine has firmly established its role in both cancer diagnosis and therapy, making it one of the fastest growing and most promising research fields in oncology Conventional drug development is hindered by poor solubility and bioavailability of therapeutics; nanotechnology-enabled carriers provide a precise strategy to enhance targeted delivery and overcome these limitations. New drug delivery systems are designed using polymers to modify the physicochemical and pharmacological properties of drug molecules, enabling controlled and effective delivery. Polymers have gained significant attention in drug delivery technologies for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs. The modification and application of various polymeric materials have undeniably proven beneficial in treating diseases where conventional therapies have failed to achieve adequate bioavailability. Over the past two decades, formulations such as controlled-release drugs that regulate the rate and duration of drug release have become widespread. With a deeper understanding of human physiology, novel polymeric formulations offering improved pharmacokinetics and enhanced patient adherence have become clinically feasible (Raj et al., 2021).

This review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of recent advances in the use of amino acid polymers as smart nano-carriers, with a particular focus on drug delivery for breast cancer treatment. It emphasizes the structural properties of the polymers and strategies for their modification to enhance targeting and therapeutic precision. Additionally, it highlights existing research gaps and challenges hindering progress in this field, while proposing future research directions aimed at accelerating nano medicine applications and developing innovative, more effective nano-drugs to improve breast cancer treatment outcomes.

2. Methodology

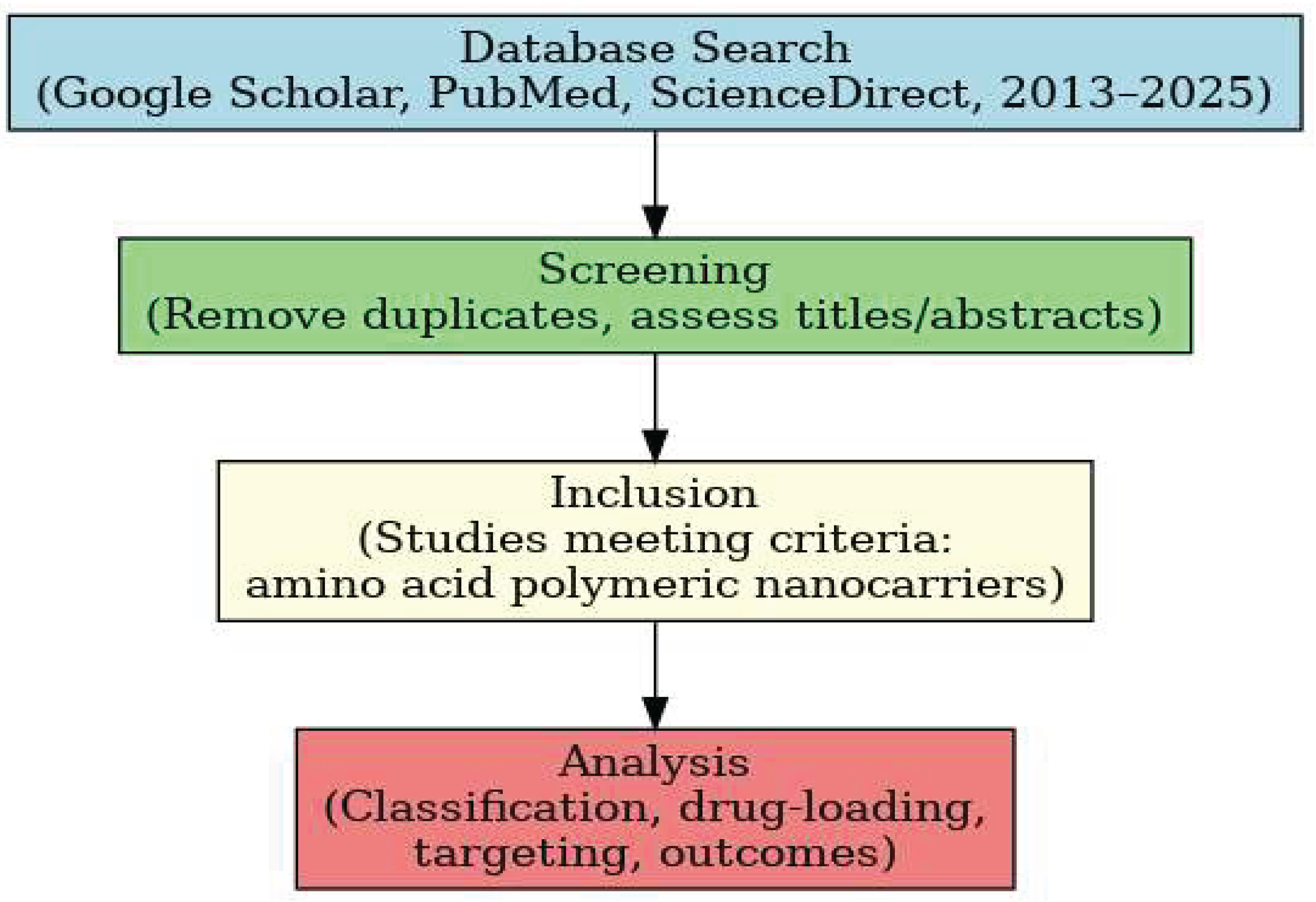

A comprehensive systematic review was conducted to assess the recent advances in amino acid polymer-based nanocarriers for targeted breast cancer therapy. Literature searches were systematically performed using Google Scholar, PubMed, and ScienceDirect, covering studies published between 2013 and 2025. The inclusion, and therapeutic evaluation of amino acid polymer-based nanocarriers in breast cancer treatment. Studies were excluded if they did not report relevant experimental findings, lacked sufficient methodological detail.

Data extraction involved careful evaluation of each eligible study, with particular attention to nanocarrier classification, drug-loading mechanisms, tumor-targeting strategies, and reported therapeutic outcomes. Studies were further analyzed to identify patterns, comparative advantages, and limitations of different nanocarrier systems. The selection process and workflow for this systematic review are illustrated in (

Figure 1), providing a transparent overview of study identification, screening, and inclusion.

3. Amino Acid Polymers: Building Blocks for Smart Nano-carriers

3.1. Classification: Natural vs. Synthetic Amino Acid Polymers

Historically, active pharmaceutical ingredients were predominantly extracted from natural sources, such as plants and microorganisms. However, with the evolution of synthetic chemistry and the advent of high-throughput screening (HTS), modern drug discovery has increasingly relied on artificial compound libraries. Despite these advances, realizing the full therapeutic efficacy of drug molecules requires the development of sophisticated and precisely engineered drug delivery systems. One of the foremost challenges in pharmaceutical sciences is the design of novel and effective strategies to transport active compounds directly to their target sites. To address the delivery challenges posed by modern therapeutics, breakthroughs in polymer chemistry have enabled the controlled and localized release of therapeutic agents. Notably, during the early 1970s, polymers derived from lactic acid were first introduced as carriers for drug delivery. These polymers facilitate cyclic release patterns that can be modulated by physiological conditions at the target site. For biomedical use, polymers must demonstrate bioresorbability, biocompatibility, and the ability to degrade safely within the body. Nevertheless, certain biocompatible yet non-biodegradable polymers—such as ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA)—are also employed in drug delivery systems to provide extended-release profiles lasting up to a year (Boddu et al., 2021).

Polymers used in these systems can be broadly categorized based on their origin into:

(A) Natural polymers, which include proteins (e.g., gelatin, casein, silk, wool), polysaccharides (e.g., starch, cellulose), polyesters (e.g., polyhydroxyalkanoates), and others such as natural rubber, lignin, and shellac:

(B) Synthetic polymers, encompassing a wide range of materials such as polyethylene, polyurethane, polysiloxanes, polyalkylene esters, polyamides, polyacrylamide, poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate), polyamide esters, poly(methacrylic acid), polyvinyl esters, poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone), polyvinyl alcohols, polylactic acid and its copolymers, polydioxanone, polyethylene glycol, poly(bisphenol A iminocarbonate), poly(acrylic acid), polymethyl methacrylate, poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate), and polyanhydrides (

Table 1).

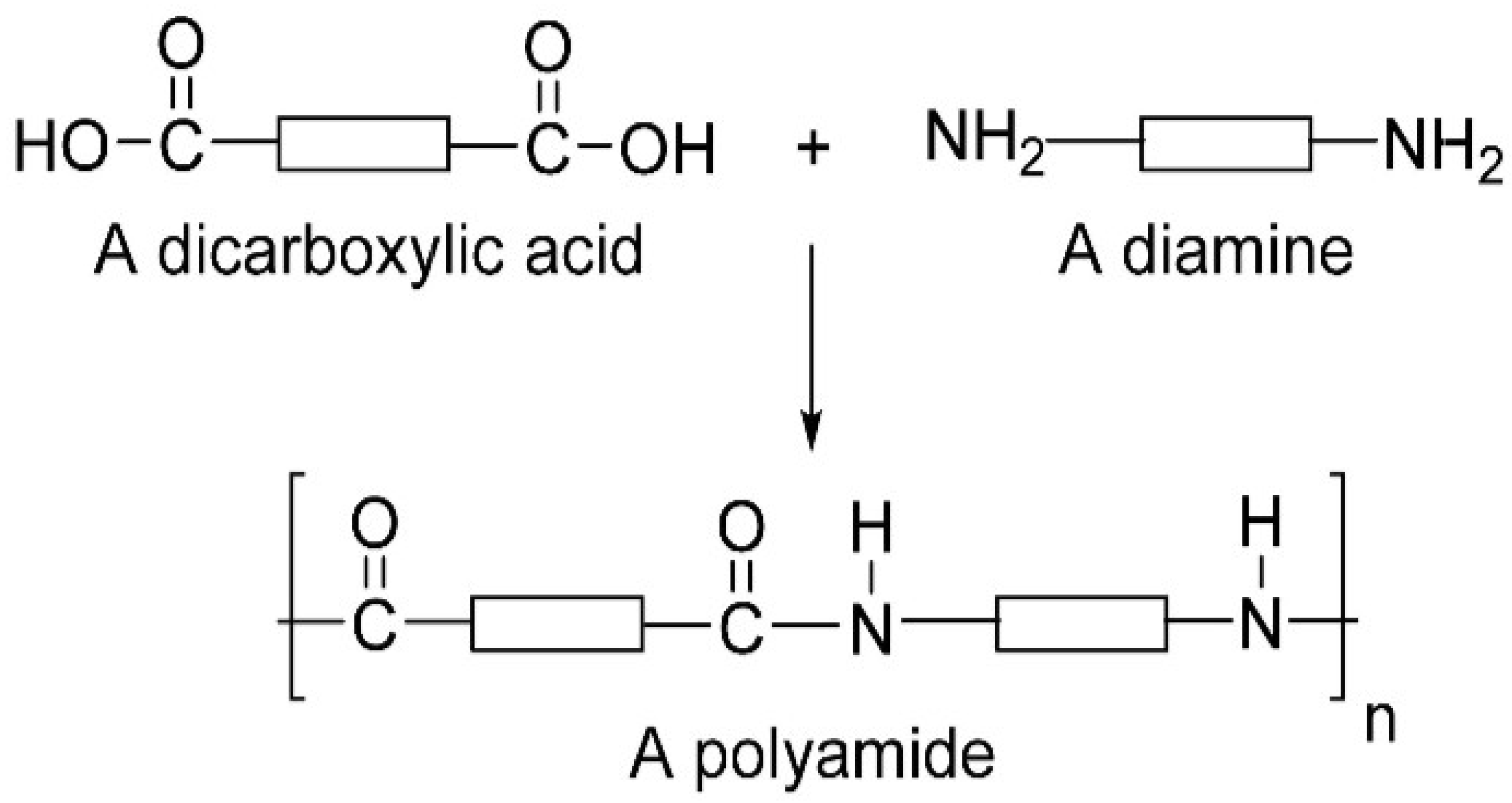

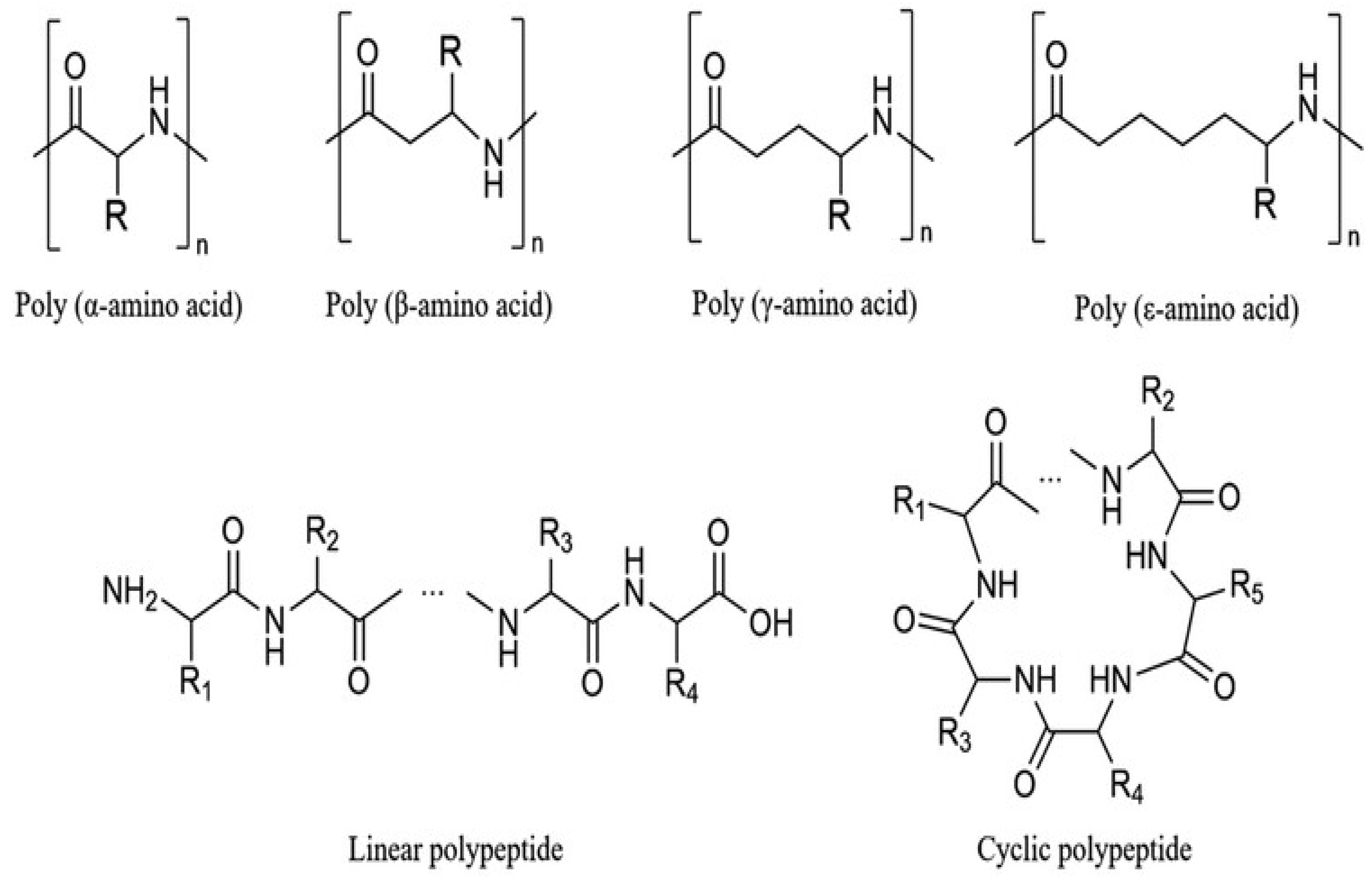

Polyamides are polymers composed of repeating units linked by amide bonds, and polyamides containing multiple amino acids of the same type connected by amide bonds are often referred to as poly (amino acids). Polyamides can occur naturally or be synthetically manufactured (

Figure 2). Natural polyamides include proteins such as silk and wool, while synthetic polyamides encompass materials like nylon, sodium poly(aspartate), and aramids. Polyamides are also classified into homogeneous polyamides, composed of a single type of monomer, and copolyamides consisting of different monomeric units. Polyamide was first introduced in 1938 by DuPont as nylon 6,6 toothbrush bristles. By the 1950s, it had expanded into the plastics industry due to its attractive thermal stability, chemical resistance, tensile strength, and rigidity. Polyamides exhibit excellent mechanical properties along with good wear and abrasion resistance. They can be differentiated based on mechanical characteristics—for instance, PA 66 is known for its rigidity and durability, while PA 12 is softer and more flexible. Commercially available polyamides include PA 4,6; PA 6; PA 6,6; PA 6,12; PA 11; and PA 12, most of which are used as thermoplastic materials. In the early 21st century, polyamide polymers began to be utilized for incorporating poorly water-soluble and metabolically unstable anticancer drugs. Their advantages as drug delivery systems include localized therapeutic effects, sustained drug release, and overall system stability. However, challenges such as microbial contamination, excessive hydration, and viscosity reduction during storage remain issues of concern (Boddu

et al., 2021).

3.2. Drug-Loading Functionalities and Structural Properties

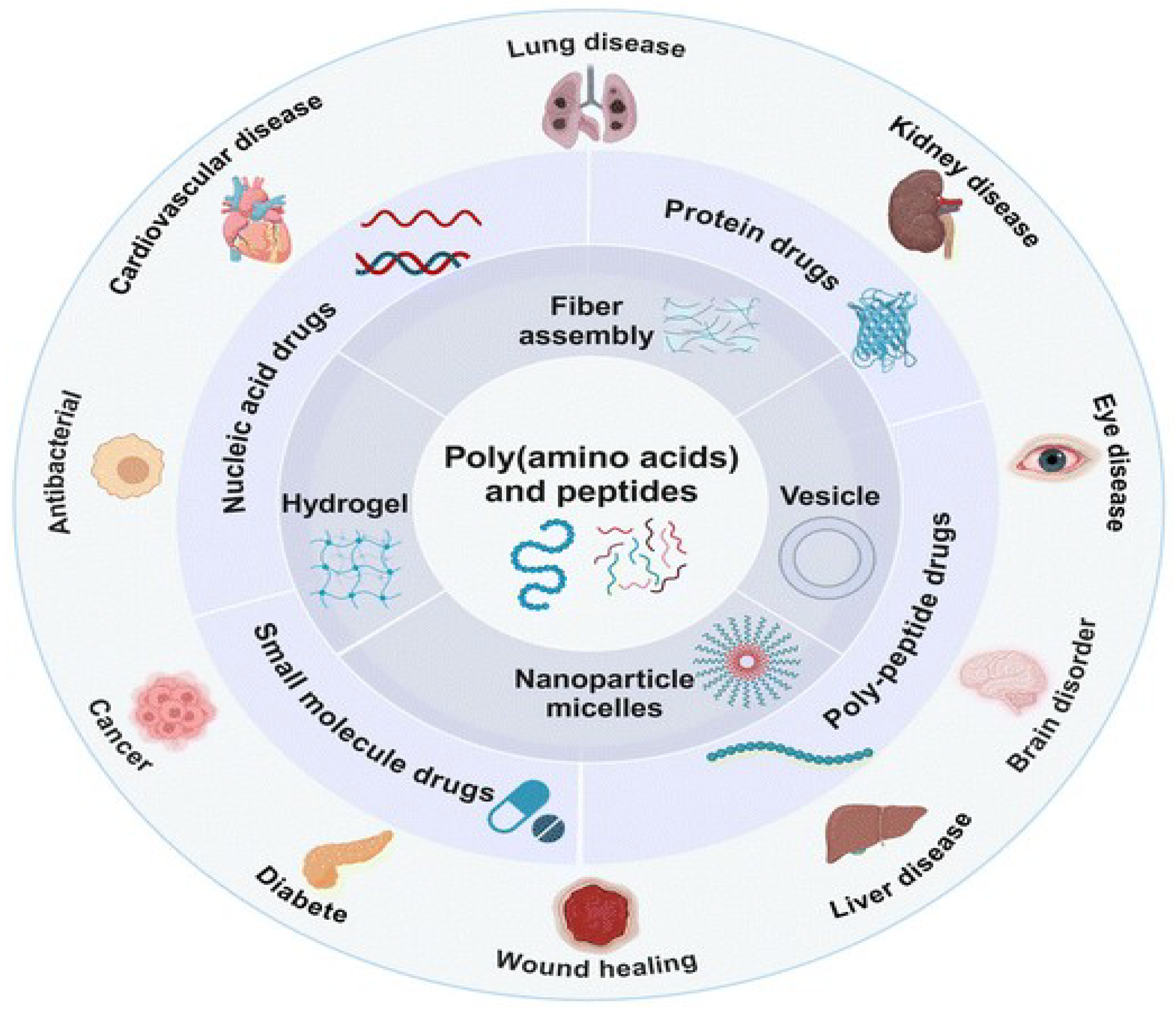

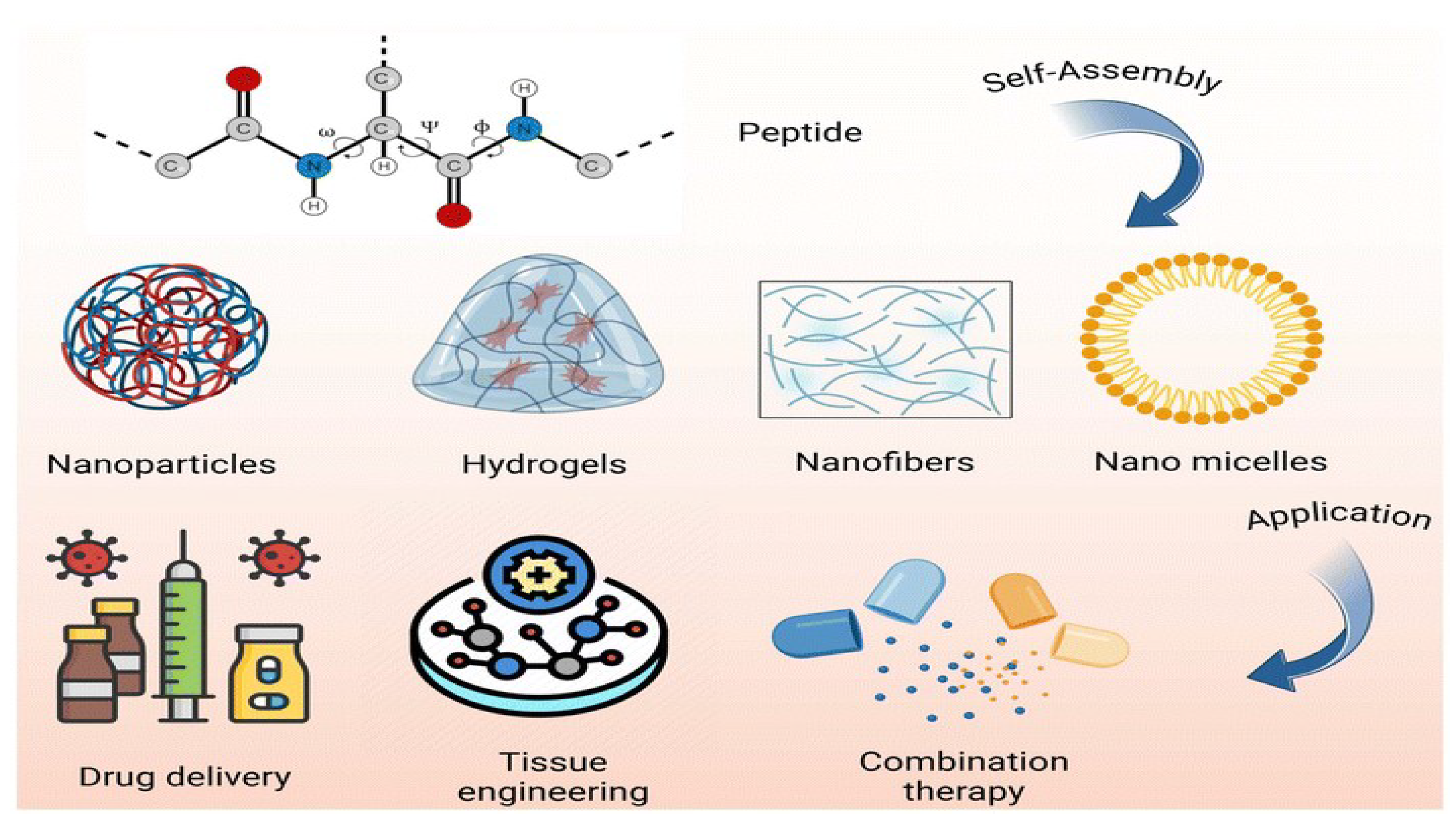

Poly (amino acids) and polypeptide-based materials have emerged as a central focus in drug delivery research due to their exc ellent biodegradability and in vivo safety. These materials are polymers or oligomers formed through the conjugation of amino acid monomers via peptide bonds. They are typically synthesized using various methods such as ring-opening polymerization of N-carboxyanhydride (NCA), amide condensation reactions of amino acids, microbial fermentation, and solid-phase peptide synthesis, these carriers are not only biocompatible and biodegradable, but they also offer structural and functional tun-ability through sequence design or chemical modifications. For instance, the types and ratios of hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids can be adjusted to form micelles, fibers, vesicles, or hydrogels, enabling a wide range of therapeutic applications (

Figure 3).

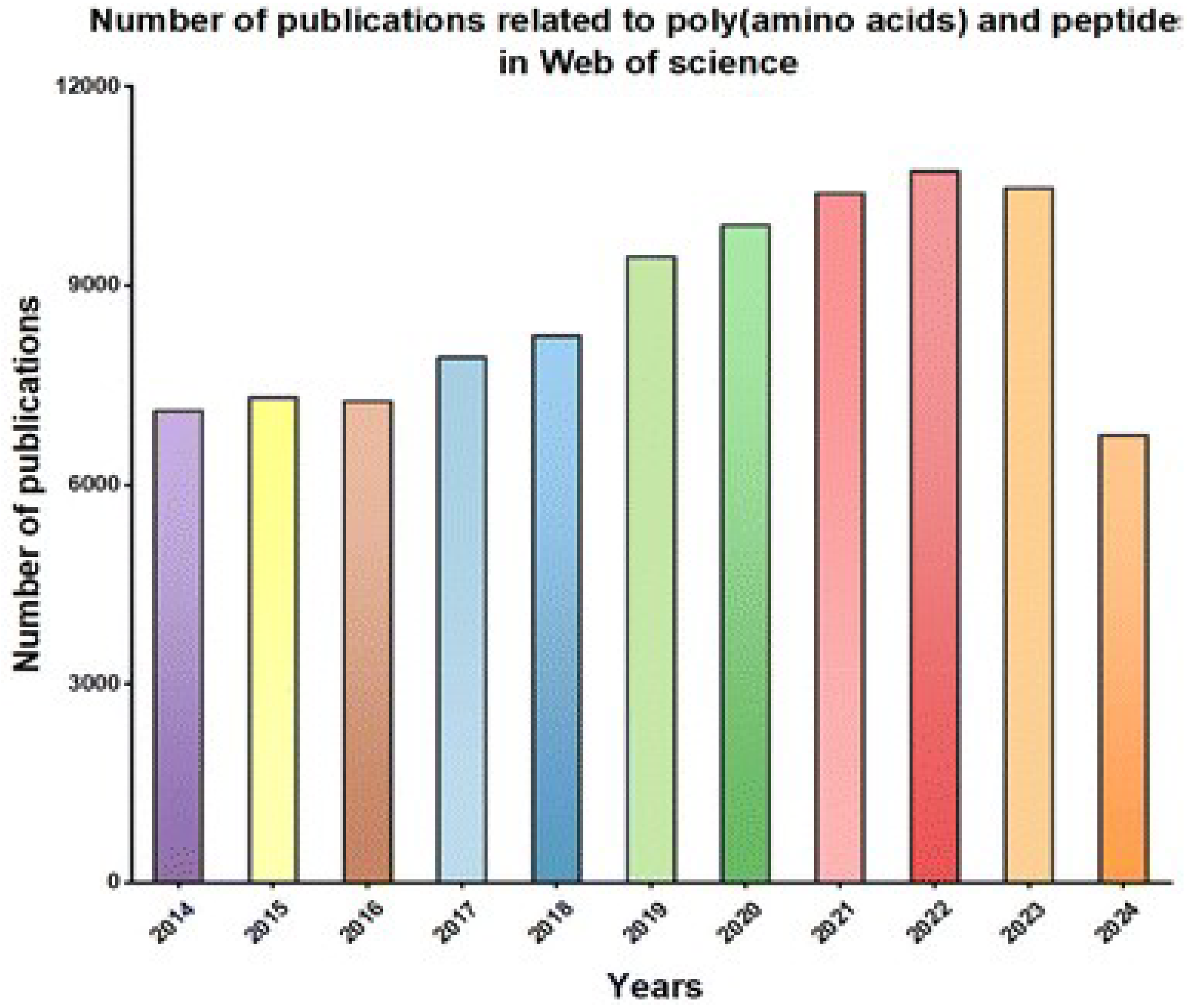

These polymers are often used to encapsulate hydrophobic small-molecule drugs via hydrophobic interactions to form nanoparticles (NPs), which enhance in vivo delivery efficiency. For hydrophilic drugs, they can be dynamically and chemically conjugated to poly (amino acids) to increase circulation time and improve accumulation in targeted tissues. With the growing attention on nucleic acid therapeutics—especially after the COVID-19 pandemic and the advancement of gene editing technologies—several challenges have emerged, including their instability, susceptibility to nuclease degradation, and negative charge, which hinders cellular uptake. These polymers can overcome such challenges by condensing nucleic acids into nanoparticles through electrostatic interactions, thereby enhancing their stability and delivery efficiency. Therapeutic proteins and peptides, although highly potent for treating diseases such as cancer and genetic disorders, face challenges like instability and enzymatic degradation in vivo, which limit their efficacy. Poly (amino acids) can provide a protective environment that maintains their bioactivity and improves their therapeutic performance , According to published data from 2014 to 2024, the number of studies on drug delivery applications of poly (amino acids)/polypeptides has exceeded 7,000 annually, showing a clear upward trend. This highlights the potential of these materials in addressing healthcare challenges and improving treatment outcomes (

Figure 4).

According to the nomenclature recommended by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a polypeptide is defined as a molecule composed of more than 20 amino acids linked by peptide bonds. and synthetic peptides are also referred to as poly (amino acids). These materials exhibit excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and unique self-assembly behavior, making them highly promising for biomedical applications.

Figure 5) shows the typical structural formula of poly (amino acids) and polypeptides. They consist of linear or branched polymers formed by amino acid monomers linked via amide bonds that resemble natural peptide bonds. Each monomer contains an amino group, a carboxyl group, and a side chain (R group). The repeated –NH–CO– peptide bonds form the backbone of poly (amino acids). The side chains of amino acids impart diverse physical and chemical properties such as hydrophilicity, hydrophobicity, acidity, and basicity. Moreover, the presence of reactive functional groups such as amino and carboxyl groups enables chemical modification of these polymers for loading various drugs or bioactive molecules. Furthermore, secondary structures such as α-helices and β-sheets distinguish these polymers from traditional macromolecules and endow them with unique physicochemical properties (Yuan

et al., 2024) .

3.3. Biodegradability and Compatibility with Tumor Environment

Poly (amino acids) and peptides demonstrate the ability to form stable complexes with drug molecules through both covalent and non-covalent interactions. This capacity facilitates their self-assembly into nanoscale structures such as micelles and nanoparticles, which serve as effective carriers for drug encapsulation and targeted delivery. The formation of these nano structures significantly enhances the solubility and stability of encapsulated drugs, addressing common challenges in pharmaceutical formulation. Nanoparticle (NP) systems represent an advanced class of drug delivery platforms, offering marked improvements in drug solubility, stability, and biodistribution. These improvements contribute directly to increased therapeutic efficacy in clinical applications. Amphiphilic polymers, by virtue of their chemical architecture, are capable of spontaneously organizing into diverse morphologies—including micelles and vesicles—when exposed to specific physiological conditions. Drugs can be incorporated into these polymeric assemblies either by physical entrapment or chemical conjugation, enabling controlled release profiles tailored to therapeutic requirements. Importantly, drug-loaded micelles exhibit both thermodynamic and kinetic stability, characterized by sustained drug release, prolonged therapeutic action, and an enhanced safety profile. A case in point is the self-assembly of paclitaxel dimers conjugated with glutamic acid (Glu–PTX2) into nanoparticles within aqueous environments. These nanoparticles form stable spherical structures with excellent structural integrity, which translates into potent cytotoxic effects and improved bioavailability of the drug Achieving precise delivery of therapeutic agents to designated organs, cellular populations, or even intracellular compartments is a critical objective in modern drug delivery research. Such targeted delivery strategies aim to maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing required dosages and systemic side effects. Poly (amino acids) and peptides are particularly well-suited for this role due to their intrinsic ability to recognize and selectively bind to specific molecular targets. This selectivity enhances drug accumulation at intended sites while concurrently reducing off-target toxicity Targeting peptides, in particular, have demonstrated remarkable specificity; peptides derived from cell surface proteins—such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), bombe-sin, and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1)—have been shown to facilitate highly selective binding to cellular receptors, thereby enabling precise therapeutic delivery (Yuan et al., 2024).

According to (Yuan et al., 2024), poly (amino acid)-based carriers can be optimized for targeted drug delivery through several strategies:

Ligand Functionalization: This strategy involves conjugating specific ligands onto the surface of poly (amino acid) carriers to enable active recognition and selective binding to target cells or tissues. Such functionalization mitigates nonspecific uptake, thereby minimizing off-target effects and enhancing therapeutic outcomes.

Passive Targeting: Leveraging the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, nanoparticles exploit the leaky vasculature and deficient lymphatic drainage characteristic of tumor tissues to accumulate preferentially at pathological sites.

Stimuli-Responsive Release: Poly (amino acid) carriers can be engineered to respond to local environmental stimuli—such as acidic pH within tumor microenvironments—triggering site-specific drug release. For instance, polyglutamic acid nanoparticles are designed to degrade under acidic conditions prevalent in tumors, ensuring localized therapeutic delivery.

Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs): CPPs, exemplified by TAT peptides, facilitate the translocation of therapeutic molecules across cellular membranes, significantly enhancing intracellular drug delivery and therapeutic efficacy.

These strategies may be deployed individually or in combination to optimize therapeutic index while minimizing adverse effects. For example, multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MEMSN) have been developed to achieve cancer-targeted, stimulus-responsive drug delivery. Surface modification with disulfide-linked β-cyclodextrin enables glutathione (GSH)-triggered intracellular drug release. Additional functionalization with peptide sequences such as RGD and the matrix metalloproteinase substrate Pro–Leu–Gly–Val–Arg (PLGVR) allows for selective targeting and enzymatic activation within the tumor microenvironment. The inclusion of polyaspartic acid (pAsp) provides a protective layer that prevents nonspecific uptake by healthy cells. Upon reaching tumor cells, enzymatic cleavage of the PLGVR sequence by metalloproteinases removes the pAsp shield, activating targeting ligands and facilitating nanoparticle uptake and drug release (

Figure 6) (J. Zhang, 2013).

From a biological perspective, amino acids constitute the fundamental building blocks of proteins, and peptides—composed of these amino acids—closely resemble endogenous proteins in structure. This resemblance imparts high biocompatibility and significantly reduces immunogenicity and toxicity risks. Peptides undergo enzymatic degradation into amino acids or smaller fragments, which are subsequently metabolized and excreted through natural physiological pathways, further supporting their safety profile. Through deliberate modification of peptide sequences and structures, degradation kinetics can be finely tuned, permitting precise control over the temporal and spatial release of therapeutic agents.

Table 2 provides a comparative overview of poly (amino acids) and polypeptides against other non-degradable biomaterials (Yuan

et al., 2024)

.

3.4. Strategies for Polymer Modification and Conjugation

3.4.1. Strategic Chemical Routes for Poly (amino acid) Fabrication

The synthesis of poly (amino acids) and polypeptides can be achieved through several methodologies, including chemical polymerization, enzymatic polymerization, biosynthesis, and self-assembly technologies. Among these, chemical polymerization remains the principal approach, widely adopted both in research laboratories and industrial applications. This method primarily comprises ring-opening polymerization, polycondensation reactions, and solid-phase synthesis. Ring-opening polymerization, in particular, is frequently employed using α-amino acid N-carboxylic anhydride (NCA) monomers. These polymers are typically produced via the ring-opening polymerization of various amino acid-derived anhydrides, with initiation by an amine compound. For instance, synthesized triblock copolymers using mPEG–NH₂ as the initiator, while Zhang et al. fabricated diblock copolymers via PEG–NH₂ macro-initiators. Given that NCAs are cyclic derivatives of amino acids, they readily undergo ring-opening, thus efficiently participating in polymerization—a feature that makes this method highly preferred. Polycondensation, on the other hand, involves the reaction between the carboxyl and amino groups of amino acids, resulting in poly (amino acid) formation along with by-products such as water or other small molecules. by adjusting reaction parameters like temperature and catalysts, polymers of varying chain lengths can be obtained. Solid-phase synthesis is another viable method characterized by stepwise assembly: the carboxyl group of an amino acid is first immobilized on a solid support, followed by sequential addition of amino acid units. Upon completion, the poly (amino acid) is cleaved from the solid support to yield the final product. One of the notable advantages of chemical polymerization is the ability to regulate the molecular weight of the resulting polymers In NCA ring-opening polymerization, molecular weight can be finely tuned by modifying the initiator-to-monomer ratio.When fewer initiator molecules are used relative to monomers, the resulting chains are longer, yielding higher molecular weights. Additionally, reaction parameters such as temperature and catalyst concentration directly influence polymerization kinetics and, consequently, molecular weight. Typically, increasing both factors accelerates the reaction and allows greater control within an optimal molecular weight range. Furthermore, the stereochemistry of the synthesized polymers can be modulated by selecting suitable monomers and fine-tuning the polymerization conditions. Despite the high efficiency and flexibility offered by chemical methods, the requirement for stringent reaction conditions and the use of organic solvents motivates the search for more sustainable alternatives. Chemical polymerization remains a preferred choice in both laboratory and industrial settings due to its precise control over polymer molecular weight and structure; however, challenges such as cost and environmental impact encourage the development of novel methods (Yuan et al., 2024).

3.4.2. Enzyme-Guided Approaches in Peptide Formation

Enzymatic polymerization of amino acid-based polymers and peptides is typically conducted under mild conditions—such as ambient temperature, atmospheric pressure, and near-neutral pH—using enzymes as biocatalysts. Compared to traditional chemical polymerization methods, these gentle conditions reduce the need for advanced equipment and eliminate the requirement for specialized apparatus capable of withstanding high temperatures and pressures. For instance, chemical synthesis of poly (amino acids) and polypeptides often necessitates temperatures ranging from 100 to 200 °C and the involvement of specific organic solvents. In contrast, enzymatic processes avoid such harsh parameters, resulting in lower energy consumption and reduced production costs. Additionally, the use of milder reaction environments helps preserve the structural integrity of both the reactants and products, as extreme conditions—such as strong acids, bases, or elevated heat—can lead to degradation or denaturation of amino acids and peptides, adversely impacting polymer quality and performance, Enzymatic polymerization also offers superior substrate specificity relative to conventional chemical techniques. Certain enzymes exhibit remarkable selectivity in recognizing and catalyzing the polymerization of specific amino acids. For example, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase selectively polymerizes L-glutamine and its derivatives due to a strong structural complementarity between the enzyme’s active site and the glutamine molecule. Similarly, papain demonstrates preferential activity towards peptide sequences containing particular residues, such as arginine or lysine, owing to its ability to specifically bind to corresponding peptide bonds. Moreover, enzymatic polymerization exhibits regioselectivity, guiding polymer growth at particular functional groups—such as α-amino, α-carboxyl, or side chain moieties—depending on the spatial structure of the enzyme’s active site In peptides like lysine, which possess multiple reactive amino groups, the enzyme can selectively target one site for polymerization, producing more structurally controlled polymers. Additionally, enzymes involved in this process show enantioselectivity, generally favoring L-amino acids while demonstrating negligible or reduced reactivity toward their D-isomers. This stereospecific behavior contributes further to the precision and functionality of the resulting biopolymers, The application of certain enzymes in the synthesis of poly (amino acids) and polypeptides is currently limited by their high cost, which significantly contributes to increased production expenses Moreover, these enzymes often suffer from limited stability and are susceptible to inactivation during storage and operational use. For example, some proteases may lose catalytic efficacy when exposed to elevated temperatures, extreme pH levels, or prolonged contact with inhibitory substances. To mitigate these issues and enhance enzyme stability, specialized preservation strategies—such as low-temperature storage or the addition of stabilizing agents—are typically required. As a result, the large-scale industrial implementation of enzymatic polymerization remains restricted, compared to chemical polymerization, enzymatic polymerization is generally characterized by slower reaction kinetics. Additionally, maintaining consistent enzyme distribution and ensuring sustained enzymatic activity throughout extended large-scale processes presents considerable technical challenges. Enzymatic methods offer an environmentally friendly solution due to their mild reaction conditions and high specificity, making them promising for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. Nonetheless, challenges related to enzyme cost and stability hinder industrial scale-up, highlighting the need for strategies to enhance enzyme efficiency and sustainability (Yuan et al., 2024).

3.4.3. Biosynthetic Systems for Amino Acid Polymer Production

Biosynthesis refers to the endogenous production of poly (amino acids) and polypeptides through the metabolic pathways intrinsic to living organism, this approach primarily relies on the cellular machinery responsible for protein synthesis, which includes the processes of transcription and translation. Within the cell, genes encoded in the DNA are transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), which subsequently directs the assembly of amino acids into polypeptide chains in accordance with its codon sequence. Transfer RNA (tRNA) serves as an adaptor molecule, while ribosomes catalyze peptide bond formation to generate the polypeptide product. Genetic engineering techniques enable the biosynthesis of poly (amino acids) by introducing genes encoding the desired polymers into microbial hosts, thereby harnessing their cellular expression systemsThe target poly (amino acid) gene is incorporated into the microorganism’s genome or plasmid, facilitating the in vivo synthesis of specific poly (amino acid) sequences that are both scalable and biocompatible. This method is widely utilized for producing biomedical polymers such as poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) However, in prokaryotic expression systems like Escherichia coli, intracellular proteases may degrade short peptides, compromising production efficiency. Strategies to overcome this challenge include employing protease-deficient strains or expressing peptides as insoluble inclusion bodies The biosynthetic production of poly (amino acids) and polypeptides via transgenic organisms involves several key stages. Initially, gene design and synthesis are tailored to match the desired polypeptide sequence, with careful consideration given to codon usage bias, which varies among host organisms for example, optimizing codon selection to favor E. coli preferences enhances gene expression efficiency. The synthetic gene fragments can be chemically synthesized or assembled from gene libraries through recombinant DNA techniques. Subsequently, the engineered gene is introduced into the host cell using appropriate transformation methods. In E. coli, heat shock transformation is commonly employed, wherein recombinant plasmids are introduced to cells under low temperatures followed by brief heat pulses to facilitate uptake for yeast systems, electroporation methods apply high-voltage pulses to transiently permeabilize cell membranes, allowing foreign DNA entry. Finally, the expression and purification of the target polymer are conducted under optimal conditions. Genes controlled by inducible promoters may require the addition of specific inducers; for instance, IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside) is widely used to induce expression of genes under the control of the lactose operon in E. coli Biological synthesis enables the production of polymers with precise and consistent sequences using natural cellular machinery, providing scalability advantages. However, reliance on cellular expression systems introduces challenges in production control and protease activity, necessitating ongoing genetic and process optimization (Yuan et al., 2024).

3.4.4. Directed Self-Assembly of Functional Peptide Structures

Under specific environmental conditions, certain amino acids or peptides have the capacity to undergo self-assembly, resulting in the formation of polymeric structures, Molecular self-assembly can give rise to a variety of nano structures, including nanoparticles (NPs), hydrogels, nano fibers, and nano-micelles, contingent upon factors such as the peptide’s chemical composition, molecular weight, and hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic ratio (

Figure 7). This self-organization is primarily governed by intra- and intermolecular forces, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic effects, which occur between the side-chain functional groups of the constituent amino acids Furthermore, the secondary structural elements of polypeptides, such as β-sheets and α-helices, play a crucial role in determining the morphology and size distribution of peptide-based nanoparticles, Self-assembly harnesses intermolecular forces to form complex nanoscale structures, opening new avenues for designing functional biomaterials. This approach allows the creation of drug delivery systems with precise control over size and morphology, and high adaptability to environmental stimuli (Yuan

et al., 2024).

Collectively, these diverse polymer synthesis and modification strategies showcase significant advancements in balancing structural control, production efficiency, and environmental considerations, thereby expanding their potential applications in biomedicine and pharmaceutical engineering.

4. Targeted Drug Delivery Strategies in Breast Cancer

4.1. Understanding Breast Tumor Microenvironment

Breast tumors are highly heterogeneous and consist not only of malignant cells but also a diverse array of surrounding cellular and non-cellular components. The interactions between tumor cells and these neighboring elements play a central role in breast cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis. Collectively, these interactions form the tumor microenvironment (TME), which includes the extracellular matrix, cytokines, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immune cells, endothelial cells, and adipocytes. Each component actively contributes to tumor growth, resistance to therapy, and metastatic dissemination, Within the TME, immune cells exhibit dual roles. Anti-tumor immune cells, such as cytotoxic CD8⁺ T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells, interact with antigen-presenting cells to recognize and eliminate malignant breast cells. In contrast, tumor-promoting immune cells, including M2 macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, are recruited by inflammatory signals and support tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastatic potential, non-immune stromal cells also significantly influence breast cancer progression. CAFs secrete growth factors and pro-inflammatory mediators that enhance tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Adipocytes contribute to the link between obesity and postmenopausal breast cancer risk, releasing factors that promote cancer stem cell expansion, invasion, and metastasis. Endothelial cells facilitate vascularization, enabling breast cancer cells to migrate and colonize distant tissues Overall, the breast cancer microenvironment is an active participant in tumor progression, shaping the disease’s invasive and metastatic behavior. Understanding the complex interactions within this environment is essential for the development of targeted and effective therapeutic strategies against breast cancer (Park et al., 2022). These insights into the TME provide a foundation for exploring its therapeutic implications, which will be discussed in the following sections.

4.2. Passive vs. Active Targeting Using Polymer-Based Nano-carriers

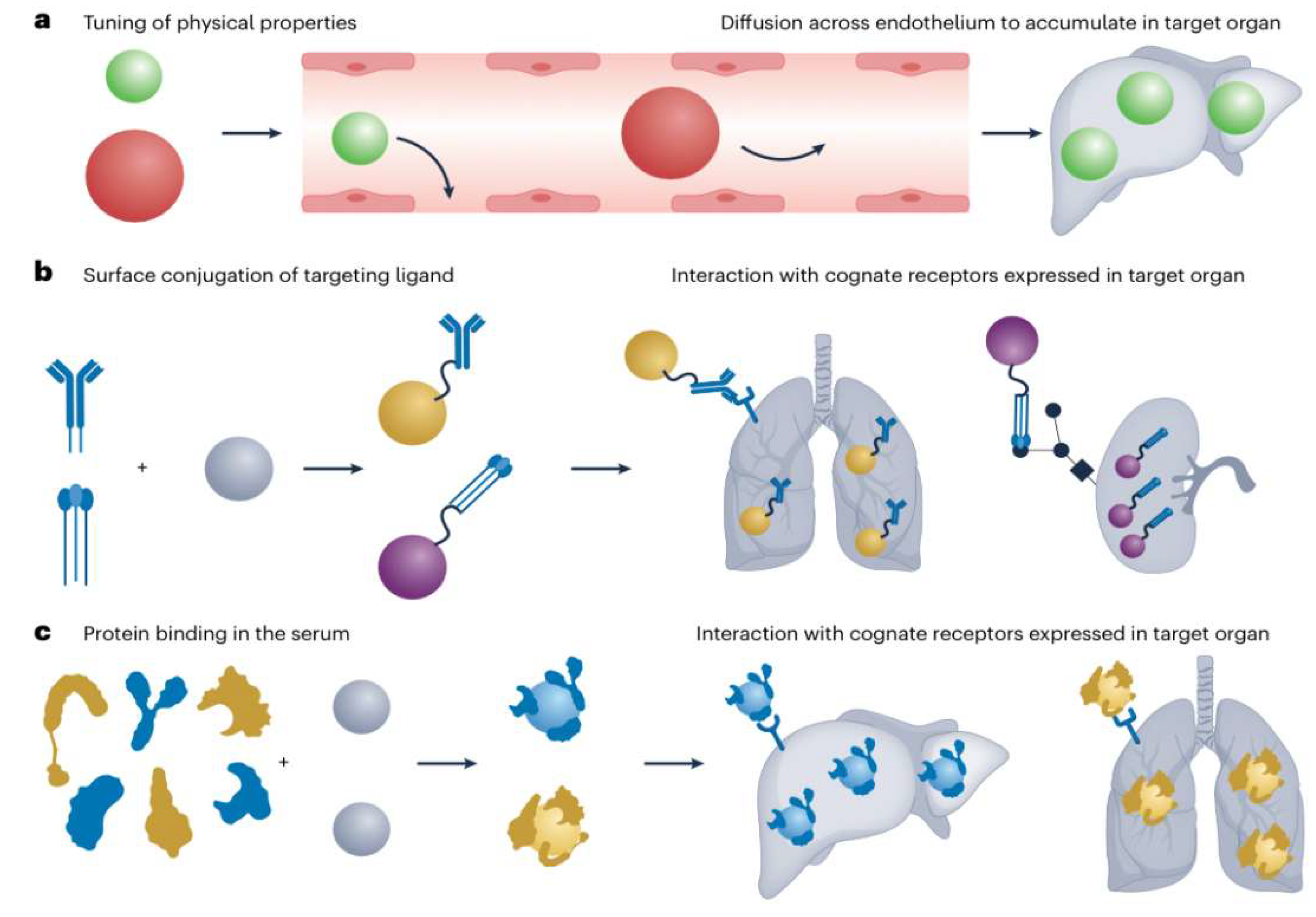

The precise delivery of therapeutic agents to targeted sites within the body has become a major focus in biomedical research, engaging experts across scientific, clinical, and engineering disciplines. For these systems to be effective, they must overcome inherent obstacles that often limit the efficacy of conventional pharmaceutical agents, including biological barriers and insufficient biodistribution to the desired tissue. Among the diverse delivery platforms now integrated into clinical practice—such as viral vectors, molecular conjugates, antibody–drug conjugates, and nanoparticles—nanoparticles stand out due to their ability to encapsulate various drug types, either individually or in combination, their minimal immunogenicity, and their highly tunable properties achieved through controlled chemical synthesis, One area that has seen remarkable progress is the delivery of nucleic acids for therapeutic and vaccine purposes. The rapid development and deployment of messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 by Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna exemplify the potential of nanoparticle-based delivery. These vaccines utilize lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to transport mRNA across multiple biological barriers that would otherwise compromise effectiveness. With over a billion doses administered globally, LNPs for nucleic acid delivery represent one of the most widely used drug modalities in history. Beyond vaccination, LNPs have been applied in numerous clinical trials for protein replacement therapy, cancer immunotherapy, RNA interference, and gene editing. Their high potency, biocompatibility, and suitability for repeated administration make them particularly favorable for clinical translation. Insights derived from LNP development offer critical guidance for designing next-generation nanoparticles with enhanced clinical translatability, Polymers constitute another class of promising materials for nucleic acid delivery. Many existing biomedical products, such as controlled-release depots and absorbable sutures, already incorporate polymers, providing a foundation for successful clinical translation. Through chemical design, the physicochemical properties of polymers can be finely tuned, enabling the development of efficient and versatile delivery systems. Collectively, lipid and polymer nanoparticles represent the dominant non-viral platforms currently explored for nucleic acid therapeutics, Advances in the engineering of lipid and polymer nanoparticles have significantly improved their ability to deliver genetic drugs to specific organs and cell types. These therapeutics must reach the cytosol of target cells while minimizing exposure to bystander cells, necessitating precisely engineered tissue-targeted delivery strategies. As in vitro assays often fail to predict in vivo outcomes, emphasis is placed on systems whose organ-targeting capabilities have been validated in animal models. While intravenous administration remains the primary route of focus, alternative administration methods can modulate the biological fate of nanoparticles, Multiple strategies—passive, active, and endogenous targeting (Box 1)—are utilized to direct nanoparticles to specific organs via the vascular network. Passive and active targeting have been extensively studied over decades, whereas endogenous targeting is an emerging paradigm, leveraging new insights into how the protein corona influences biodistribution. While these mechanisms are exemplified for genetic therapeutics, the principles are broadly applicable to other drug modalities, including small molecules and protein-based therapies (Dilliard and Siegwart, 2023).

Box 1 Mechanisms of nanoparticle targeting

Nanoparticles can be directed to specific regions of the body using multiple mechanisms, either individually or in combination (

Figure 8). The overall design of a nanoparticle is determined by how these strategies are integrated to achieve the desired organ-targeting outcome. The mechanisms of nanoparticle targeting, as described below, are summarized in Box 1 adapted from (Dilliard and Siegwart, 2023).

Passive targeting

This approach relies on adjusting the physical characteristics of nanoparticles—including size, shape, stiffness, and surface charge—to optimize interactions with anatomical and physiological features. For instance, modulating nanoparticle size can influence its ability to exit discontinuous blood vessels, such as those present in the liver and spleen (

Figure 8.a).

Active targeting

Active targeting involves decorating the nanoparticle surface with chemical or biological ligands that specifically recognize and bind to receptors or cellular markers highly expressed on target organ cells (

Figure 8.b). For example, conjugation with monoclonal antibodies allows efficient delivery of nucleic acids into immune cells that are otherwise challenging to transfect.

Endogenous targeting

Endogenous targeting is based on designing nanoparticles to selectively bind certain plasma proteins upon administration, guiding them to specific organs and enhancing uptake by target cells (

Figure 8.c). A notable example is the role of cholesterol-transport-related proteins in facilitating effective delivery of lipid nanoparticles to hepatocytes in the liver.

4.3. Ligand-Mediated Targeting (e.g., HER2, EGFR)

The human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family, comprising HER1/EGFR, HER2, HER3, and HER4, together with their ligands, forms a critical signaling system that regulates cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Ligand engagement induces HER monomers to form homo- or heterodimers, activating their intrinsic autokinase activity and triggering phosphorylation of C-terminal tyrosine residues, which serve as docking sites for adaptor proteins that initiate downstream signaling pathways. HER2, the preferred dimerization partner for HER3 and EGFR, amplifies these signaling events, whereas HER3 is activated by its dimerization partner and uniquely possesses six phosphotyrosine binding sites for the p85 subunit of PI3K, the highest among HER family members. Consequently, HER2-HER3 dimers are potent activators of PI3K signaling, representing a key oncogenic unit in breast and other solid tumors. Dysregulation of HER signaling, via HER2 gene amplification or EGFR gain-of-function mutations, drives tumorigenesis in solid cancers. In breast and ovarian cancers, HER2 overexpression is associated with poor clinical outcomes, prompting the development of targeted therapies such as small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Lapatinib, a selective inhibitor of HER2 and EGFR kinases, is currently the only FDA-approved TKI for advanced HER2+ breast cancer. While in vitro data suggest equipotent inhibition of HER2 and EGFR, its clinical benefit has been largely confined to HER2+ tumors and is frequently limited by acquired therapeutic resistance. Unlike other kinase inhibitors, resistance to lapatinib does not appear to involve mutations in HER2 or reactivation of its phosphorylation, nor is it reversed by molecular knockdown of HER2, indicating that resistant cells become independent of HER2 signaling. The discontinuation of the lapatinib monotherapy arm in the ALTTO phase III trial due to increased disease recurrence highlights the urgent need to understand resistance mechanisms. Persistent activation of the PI3K pathway has been observed in models of acquired resistance, although the contributions of PI3KCA mutations or PTEN loss remain debated. Notably, resistance can be mediated by autocrine induction of membrane-bound heregulin (HRG), the HER3 ligand, which, together with incomplete inhibition of EGFR phosphorylation by lapatinib, establishes an HRG-HER3-EGFR-PI3K signaling axis. This axis not only underlies lapatinib resistance but also contributes to cross-resistance to FDA-approved EGFR TKIs, with significant implications for the treatment of HER2- and EGFR-dependent tumors and for kinase-driven malignancies more broadly (Park et al., 2022).

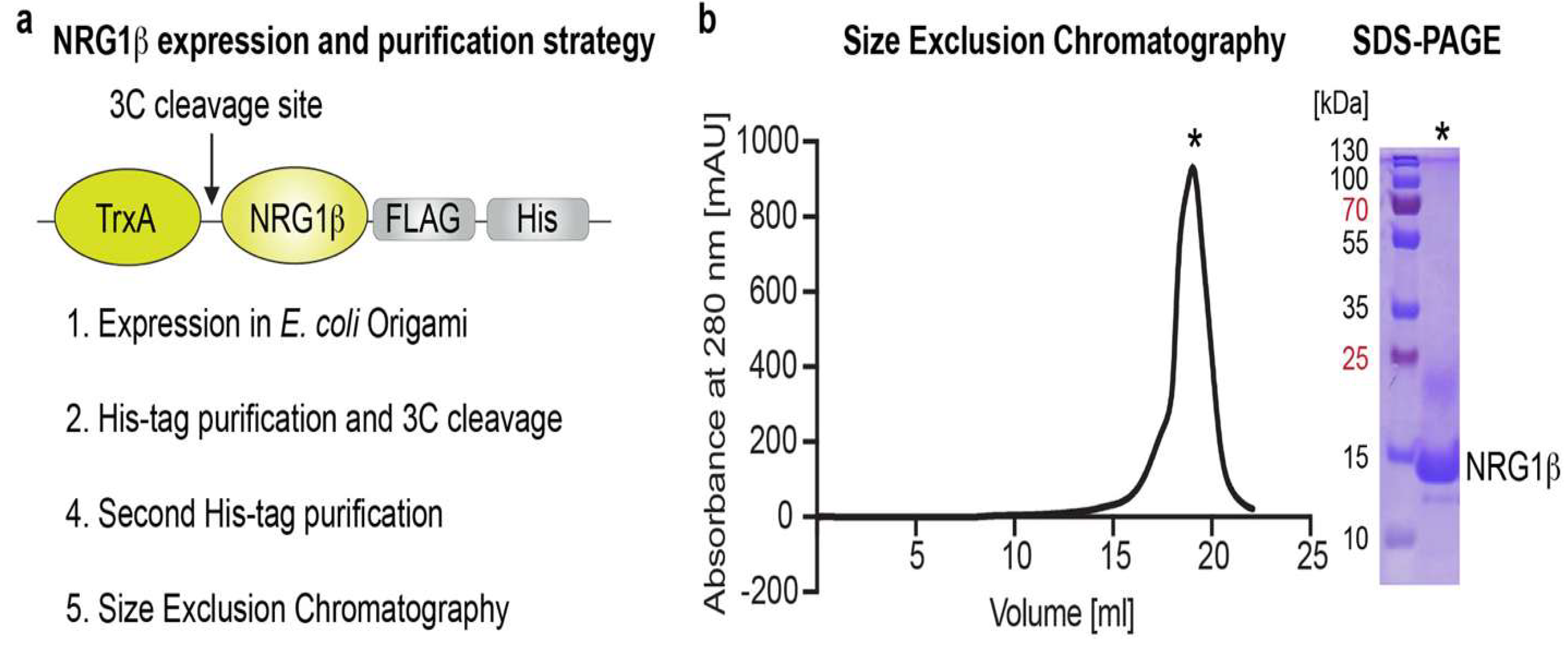

All ligands that interact with HER receptors contain an EGF-like domain, which is both necessary and sufficient for receptor binding. To reconstruct the HER2/HER3/NRG1β complex, a protocol was established for the expression and purification of the EGF-like domain of the HER3-specific ligand NRG1β. The domain is stabilized by three conserved disulfide bonds, presenting a significant challenge for producing correctly folded recombinant HER receptor ligands. Following established methods, the NRG1β EGF-like domain (residues 177–236) was expressed as a fusion protein with thioredoxin (TrxA) and C-terminal FLAG (DYKDDDDK) and 6× polyhistidine (His) tags in E. coli Origami B (DE3) pLysS cells. This bacterial strain carries mutations that reduce the cytoplasmic reducing environment, facilitating disulfide bond formation (

Figure 9a–b). The TrxA fusion additionally supports proper disulfide bond formation and enhances solubility of the recombinant protein. The construct includes a 3C protease cleavage site positioned between TrxA and NRG1β (Figure 9.a), while the His-tag enables affinity purification from E. coli Origami cells. Moreover, the FLAG-tag can be utilized to generate NRG1β-coated resin by incubating the purified protein with anti-FLAG resin, which subsequently allows pulldown of HER3 from lysates of HER3-expressing cells (Trenker

et al., 2022).

b. SEC analysis. The SEC chromatogram of NRG1β loaded onto a Superdex 200 Increase column reveals a single, homogeneous peak eluting at 18–19 ml. The corresponding Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel, loaded with 10 μl of sample, confirms the high purity of the eluted NRG1β protein. Adapted from (Trenker et al., 2022).

4.4. Stimuli-Responsive Release Systems (pH, enzymes, redox)

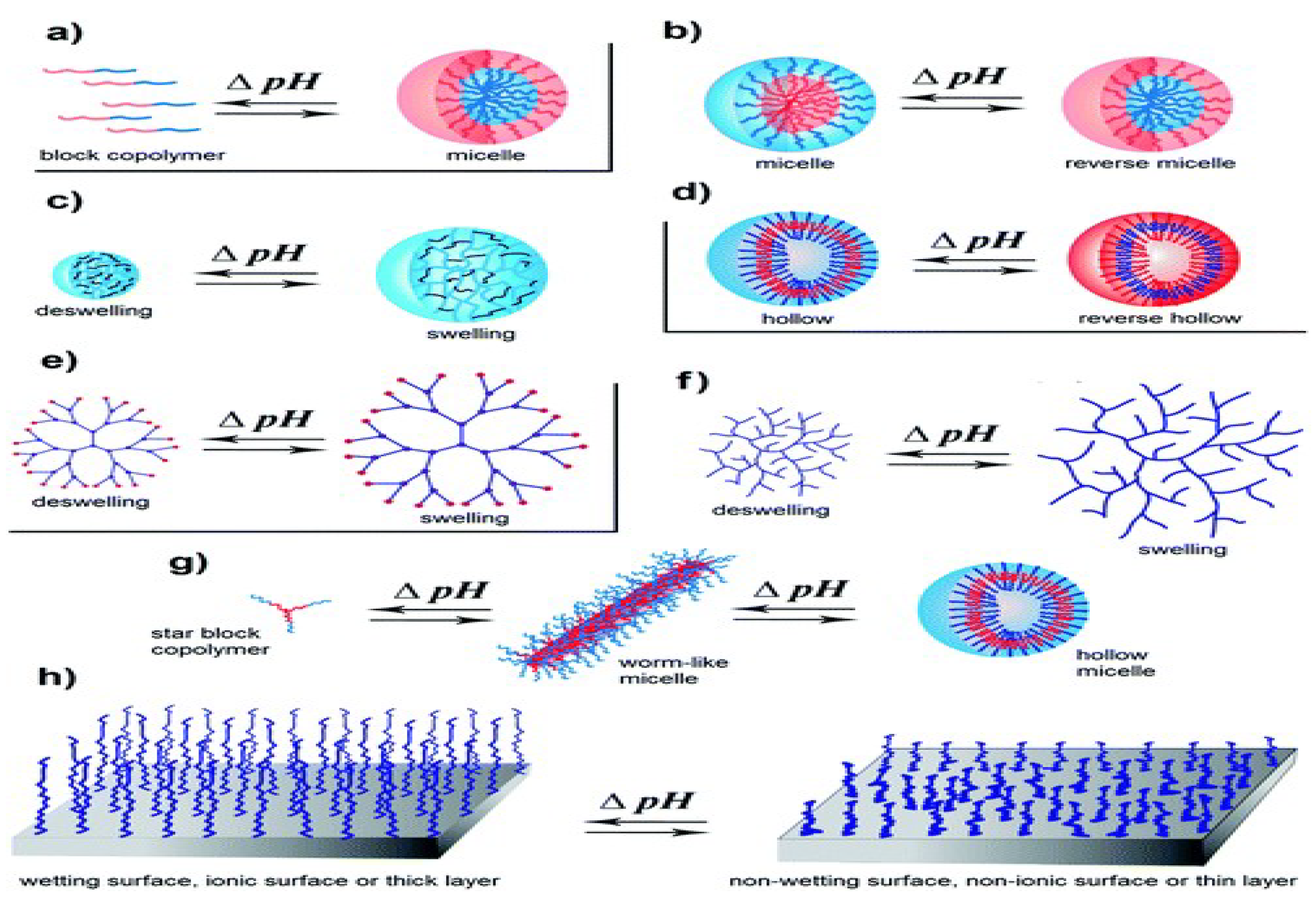

Researchers across multiple disciplines continue to investigate safer and more effective strategies for delivering drugs to specific sites of action, aiming to enhance both specificity and therapeutic efficacy. Over time, extensive studies on biomaterials have enabled the development of advanced controlled delivery systems, benefiting from interdisciplinary contributions spanning chemistry, biology, physics, pharmacology, and clinical practice. Modern biomaterials encompass diverse chemical structures, varied morphologies, and multiple physiological functions, including synthetic polymers, biomacromolecules, nano- and microparticles, biocompatible and biodegradable systems, targeted delivery capabilities, cargo protection, and bulk materials. Flexible and sophisticated designs have allowed drug carriers to adapt to complex physiological environments, enabling on-demand release and improved treatment outcomes. The evolution of smart biomaterials represents a further advancement, integrating stimuli-responsiveness to overcome limitations of conventional delivery systems. By responding to internal physiological cues such as pH, redox state, temperature, enzymes, and mechanical forces, or to external stimuli such as light, ultrasound, electric, and magnetic fields, these systems achieve precise spatiotemporal control over drug release, maximizing efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity. Stimuli-responsive polymeric systems can be categorized into chemical, physical, and biological types, with some platforms designed to respond to multiple or overlapping stimuli. Representative systems responsive to pH, acoustic, photo, magnetic, electric, and enzymatic triggers have been developed, offering distinct advantages and presenting opportunities for further optimization (

Table 3).

Smart biomaterials can be engineered to respond to changes in environmental conditions, enabling localized therapeutic delivery in regions where pH is either acidic or basic, and allowing drug release in specific organs or pathological conditions associated with pH fluctuations. For highly toxic chemotherapeutics, pH-sensitive delivery systems help limit systemic drug exposure, enhancing safety and efficacy. The acidic extracellular environment of solid tumors provides an opportunity for developing pH-responsive platforms that undergo chemical and/or physical transformations under low pH conditions. Beyond cancer therapy, such systems have been explored for other diseases, including gastric ulcers, osteomyelitis, and diabetes. Typically, polyelectrolyte polymeric systems contain weak acidic or basic groups within the polymer backbone, where environmental pH changes trigger proton acceptance or release, influencing bond cleavage, solubility, and polymer structure. Various materials with pH-responsiveness have been synthesized and studied in diverse formats, including hydrogels, nanoparticles, beads, hollow particles, and three-dimensional porous scaffolds. For example, N-carboxyethyl chitosan combined with dibenzaldehyde-terminated poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) has been encapsulated with doxorubicin (DOX) to form an injectable hydrogel for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy, where pH-induced swelling of the polymeric network promotes controlled drug release. Similarly, fluorescent boronate nanoparticles encapsulating DOX have been developed for intracellular imaging and targeted suppression of MCF-7 cancer cells; these nanoparticles exploit a boronic ester linkage between acid-cleavable PLA–PEI copolymer moieties, allowing a burst release of DOX upon a pH shift from 7.4 to Representative examples of polymeric systems and their pH-responsive behaviors are illustrated in (

Figure 10) (Wells

et al., 2019).

5. Literature-Based Applications in Breast Cancer Therapy

5.1. Summary of Preclinical Findings on Amino Acid Polymer Carriers

Amino acid-based polymers have emerged as highly promising carriers for preclinical drug delivery, owing to their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to achieve targeted release. These polymers are synthesized from naturally occurring amino acids, utilizing functional groups such as amines, carboxyls, hydroxyls, and thiols to create versatile polymeric architectures suitable for a wide range of therapeutic applications. Preclinical studies have shown that these polymers enhance drug solubility and stability, improve tumor targeting, and reduce systemic toxicity. A prominent example is cystine-derived polyamides, which incorporate disulfide bonds responsive to intracellular glutathione and carboxylic acid groups sensitive to acidic pH, enabling selective release of anticancer drugs within tumor cells while sparing normal tissues. Beyond their redox and pH responsiveness, amino acid-based polymeric nanoparticles can facilitate the co-delivery of multiple drugs for combination therapies, enhancing intracellular accumulation and therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. Polymeric nanoparticles are typically prepared either through direct polymerization of monomers or by dispersing preformed polymers, with ionic gelation being a widely used technique that leverages electrostatic interactions between cationic and anionic polymer chains to form stable nanoparticles with controlled size and drug loading. Overall, these polymers demonstrate versatile, safe, and stimuli-responsive characteristics, highlighting their potential to advance next-generation precision cancer treatments (Ali et al., 2022). This evidence collectively underscores the potential of amino acid-based polymeric nanoparticles to provide precise, safe, and efficient drug delivery in breast cancer therapy, addressing limitations of conventional treatments and enhancing therapeutic outcomes.

While preclinical studies highlight the versatility and targeted delivery capabilities of amino acid-based polymeric carriers, it is equally important to examine their release profiles, tumor penetration, and the limitations reported in experimental studies to understand their full therapeutic potential.

5.2. Release Profiles, Tumor Penetration, and Study Limitations

Chemotherapy, often combined with radiation therapy and surgical intervention, remains a primary treatment approach for breast cancer. However, conventional pharmacotherapy is limited by inadequate penetration of therapeutic agents into tumor tissues, leading to increased systemic toxicity and suboptimal pharmacokinetics. The integration of nanotechnology in breast cancer therapy enhances the efficiency and safety of chemotherapeutic regimens. Over recent years, hybrid polymeric nanoparticles have been developed not only for targeted drug delivery but also for in vivo cancer diagnostics and molecular screening of tumor biomarkers. These nanotechnology-based strategies show significant potential for treating a variety of malignant conditions, Existing breast cancer treatments face several critical limitations, including a lack of selective toxicity, which reduces therapeutic efficacy and compromises treatment outcomes. Healthy tissues are often damaged, necessitating dose reductions to mitigate toxicity. Additionally, poor drug biodistribution and limited penetration in solid tumors hinder therapeutic effectiveness. Tumor vasculature heterogeneity further restricts drug extravasation, with normal organs often receiving 10- to 20-fold higher drug accumulation than the tumor site. Many chemotherapeutic agents are unable to permeate more than 40–50 micrometers from blood vessels—roughly the combined diameter of three to five cells—contributing to multidrug resistance (MDR) and potential treatment failure. MDR may also develop across multiple drugs due to over-expression of efflux transport proteins. Nanotechnology, particularly polymeric nanoparticles, provides a more targeted approach to overcome these challenges by protecting drugs from premature degradation, enhancing tissue-specific delivery, controlling release kinetics, improving intracellular uptake, and reducing systemic toxicity (Grewal et al., 2021). This emphasizes the critical need for advanced delivery systems, such as amino acid-based polymeric nanoparticles, to enhance tumor penetration, minimize off-target toxicity, and overcome multidrug resistance.

A considerable body of research has focused on amino acid metabolism in breast cancer, examining both the levels of individual amino acids and their interactions with other metabolites as part of metabolomic profiling of biological fluids. Findings indicate that certain amino acids, such as threonine, arginine, methionine, and serine, tend to show elevated concentrations in breast cancer patients compared with healthy controls, while others, including aspartate, proline, tryptophan, and histidine, are often reduced. However, interpretation of these profiles requires careful consideration of the high heterogeneity of breast cancer, as well as patient-specific factors such as age and race. The diagnostic accuracy based on amino acid profiling varies widely, ranging from 52% to 98%, depending on the number of metabolites included in the algorithm. Amino acid levels in biological fluids are increasingly being used to estimate breast cancer risk, though these associations are influenced by sample characteristics, menopausal status, and age. Among the most significant indicators are glutamine/glutamate, aspartate, arginine, leucine/isoleucine, lysine, and ornithine. Investigating metabolic alterations in amino acids provides a promising avenue for developing novel therapeutic strategies, monitoring treatment responses, addressing treatment-related complications, and assessing survival outcomes, underscoring the critical importance of research in this field (Bel’skaya, Gundyrev and Solomatin, 2023). Collectively, these findings highlight both the therapeutic potential and current limitations of amino acid-based polymeric nano-carriers in breast cancer, emphasizing the need for optimized designs and further preclinical evaluation.

6. Challenges Highlighted in Existing Literature

Poly (amino acid) polymers have significantly contributed to the advancement of drug delivery systems, owing to their similarity to natural proteins, inherent biocompatibility, and biodegradable degradation products. Their hydrophilic nature allows for facile chemical modifications through reactive functional groups, including amines, hydroxyls, and thiols, which can be exploited to form diverse polymeric architectures suitable for various therapeutic applications. Despite these advantages, poly (amino acid) polymers face inherent challenges such as poor mechanical properties, potential immunogenicity arising from amide bonds, and charge-induced cytotoxicity. These limitations prompted the development of pseudo poly (amino acids), which are synthesized by linking synthetic polymers through non-amide bonds, such as esters, carbonates, and imino-carbonates, thereby enhancing their physical and mechanical stability. Tyrosine-derived poly (amino acids) are an example of such pseudo polymers, offering superior mechanical properties while maintaining biocompatibility, Drug delivery systems based on poly(amino acids), including polymeric micelles and dendrimers, continue to evolve; however, their clinical translation remains limited by challenges in maintaining micellar integrity in the bloodstream. Polymeric micelles, upon intravenous injection, may exist in an assembled state or as macromolecular unimers, with their stability affected by dilution, pH and salt fluctuations, and interactions with serum proteins. Such destabilization can result in premature release of the therapeutic payload before reaching the target site. The stability of micelles is governed by both kinetic and thermodynamic factors, with micelles exhibiting critical micelle concentrations (CMC) below 1–5 mg/L demonstrating improved in vivo stability. Considering an average blood volume of 6 liters, the corresponding minimum polymer dose ranges from 6–30 mg to maintain micellar integrity. Interactions with serum proteins, including albumin, globulins, apolipoproteins, fibrinogen, and immunoglobulin G, can further affect drug release. For instance, camptothecin’s carboxylate form interacts with human serum albumin, shifting the equilibrium and causing leakage from poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (benzyl aspartate) micelles. Similarly, amphiphilic block copolymers loaded with paclitaxel dissociated rapidly in the presence of serum proteins, emphasizing the importance of surface properties and protein adsorption in determining micellar stability (Boddu et al., 2021).

To address these limitations, several strategies have been explored to enhance micellar stability and drug retention. Hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions can improve in vivo stability, while covalent core cross-linking has been widely employed to produce robust polymeric micelles. For example, ionic cores of phenylalanine-linked poly (ethylene glycol)-b-poly (L-glutamic acid) were cross-linked with cyst-amine in the presence of calcium ions, resulting in controlled doxorubicin release at acidic lysosomal pH and enhanced antitumor efficacy in ovarian tumor xenograft models. Surface modifications with polyanionic agents, such as hyaluronic acid, further improve micelle stability and enable selective targeting, as demonstrated by PLys-b-PLLA micelles preferentially taken up by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells compared to heparin- or carboxymethyl-dextran-coated micelles, Overall, poly(amino acid) polymers offer a highly versatile platform for drug delivery, particularly in oncology, due to their tunable chemical structures, stimuli-responsive behavior, and biocompatibility. Their adaptability allows for modifications to micellar structures informed by preclinical and clinical insights, enabling the design of novel formulations with improved therapeutic performance. Although challenges remain, including control over drug release rates, potential immunogenicity, and enzymatic degradation requirements, poly (amino acid)-based systems continue to demonstrate significant promise for the development of high-performance, next-generation therapeutic agents (Boddu et al., 2021).

Despite these advances, further preclinical and clinical studies are essential to fully optimize poly (amino acid)-based drug delivery systems, ensuring enhanced stability, precise targeting, and maximal therapeutic efficacy in breast cancer treatment.

7. Research Gaps and Future Study Directions

7.1. Unexplored Polymers or Ligand Strategies

This study synthesizes evidence from 12 meticulously analyzed research investigations, spanning preclinical in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo models (including mice and rats), as well as clinical trials involving breast cancer patients and those experiencing relapse. Collectively, these studies underscore the significant potential of polymeric nanoparticles (P-NPs) as advanced drug delivery systems, demonstrating enhanced targeting of therapeutic agents to tumor tissues. The evidence indicates that P-NPs improve drug uptake, intracellular accumulation, and retention, enabling sustained and controlled release while potentially reducing the required drug dosage. These characteristics contribute to heightened therapeutic efficacy and decreased systemic toxicity, despite these promising outcomes, several critical knowledge gaps remain. First, while preclinical findings are compelling, there is a clear need for additional clinical validation to confirm the safety, pharmacokinetics, and long-term efficacy of P-NPs in diverse patient populations. Second, the variability in tumor biology and patient-specific factors highlights the necessity for personalized P-NP formulations, yet systematic strategies to tailor nanoparticles to individual breast cancer phenotypes remain underdeveloped. Third, the potential synergistic integration of P-NPs with complementary therapeutic modalities, including immunotherapy and gene therapy, is still largely unexplored, limiting the optimization of combinatorial treatment strategies Moreover, while P-NPs demonstrate improved tumor targeting and reduced off-target toxicity, the mechanisms governing precise intracellular delivery, controlled release dynamics, and long-term retention within heterogeneous tumor microenvironments are not fully elucidated. Addressing these mechanistic uncertainties is essential for maximizing therapeutic efficacy and overcoming challenges associated with multidrug resistance and treatment failure (Araújo et al., 2023) .

Future research should prioritize bridging these gaps through comprehensive clinical studies, systematic evaluation of patient-specific nanoparticle designs, and investigation of multi-modal therapeutic combinations. Such efforts are critical for translating the preclinical promise of P-NPs into practical, clinically effective interventions for breast cancer. By strategically addressing these unresolved questions, the field can advance toward more precise, safe, and effective treatment paradigms, ultimately improving patient outcomes and expanding access to next-generation therapeutic options (Araújo et al., 2023).

7.2. Combinational Drug Delivery Approaches

Breast carcinoma has long been the focus of extensive investigations. Depending on disease stage and prognosis, conventional treatment modalities—such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery—often prove insufficient. These therapies not only carry invasive characteristics but also induce significant toxicity, leading to adverse reactions and severe side effects that compromise patient outcomes. Consequently, the literature examined in this systematic review highlights the growing therapeutic promise of polymeric nano-formulations as carriers for antineoplastic agents. These nano-formulations enable more precise, controlled, and site-specific drug delivery, thereby offering a superior therapeutic profile compared to conventional approaches, In a study conducted by Abou-El-Naga et al. (2018), in vitro assays were designed using polymeric nanoparticles (P-NPs) loaded with docetaxel (DTX)—a chemotherapeutic agent already widely applied in the management of malignancies including lung, prostate, gastric, ovarian, vesical, craniofacial, and notably, breast cancers. For this purpose, poly (l-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) was employed as the nanoparticle base due to its recognized biocompatibility and biodegradability. The encapsulation of DTX within PLGA nanoparticles was shown to enhance its therapeutic performance. Over a two-week experimental period using the MTT assay, drug uptake was found to be dependent on the duration of cellular exposure, reaching maximum efficiency through endocytosis-mediated internalization. Importantly, concentration-dependent cytotoxicity was confirmed, with PLGA-DTX systems inducing a more significant apoptotic effect via the activation of key regulatory pathways involving Caspase-9, Caspase-3, and P53 genes. These findings suggest that PLGA-based nano-formulations of docetaxel hold substantial potential as effective drug delivery systems in breast cancer therapy (Araújo et al., 2023).

Further advancements were reported by Yap et al. (2020), who introduced donor–acceptor Stenhouse adducts (DASAs)—novel photosensitive molecules capable of overcoming the limited tissue penetration of ultraviolet (UV) light. Upon photoisomerization, DASAs undergo changes in solubility, polarity, and structural configuration, making them highly attractive for biomedical applications. In this investigation, ellipticine-loaded micelles were developed and tested against the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line under both irradiated and non-irradiated conditions. Although encapsulation of ellipticine within DASA-based polymers was successful, a limitation was identified in the drug-loading capacity, as higher concentrations destabilized the micellar serum structure. Nevertheless, the micelles demonstrated significantly enhanced cytotoxicity following irradiation, with a notable increase in toxicity persisting for up to 72 hours, suggesting sustained drug release. These outcomes confirmed that DASA-based micelles can effectively deliver ellipticine into MCF-7 breast cancer cells, particularly under light-activated conditions (Araújo et al., 2023).

Similarly, Oda et al. (2018) evaluated the therapeutic and diagnostic potential of polymeric nanoparticles by formulating a lyophilized kit containing diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)-functionalized 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] loaded with paclitaxel (PTX) (MP-DTPA/PTX). Designed as a theranostic tool, the system demonstrated excellent stability, preserving both physicochemical and radiochemical properties until administration to 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma cells. Moreover, freshly prepared PM formulations consistently retained their biological activity throughout delivery, thereby ensuring effective targeting of breast cancer cells (Araújo et al., 2023) .

7.3. Integration with Computational and AI-Guided Design

Amino acid metabolism constitutes a central component of breast cancer biology, profoundly affecting tumor progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Dysregulation of amino acid transporters and the resultant metabolic reprogramming within cancer cells present compelling therapeutic targets. However, a critical limitation in this domain is the capacity of cancer cells to employ compensatory mechanisms, such as upregulating alternative amino acid transporters to circumvent the inhibition of a specific pathway. Such adaptive responses may undermine the long-term efficacy of single-agent metabolic therapies. To overcome this challenge, future research must prioritize combination strategies that concurrently target multiple amino acid transporters or intersecting metabolic pathways. Integrating metabolic inhibitors with established modalities—immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy—could produce synergistic therapeutic effects by exploiting the inherent vulnerabilities of cancer cells while minimizing compensatory adaptations, Another pressing research direction involves elucidating the complex interplay between amino acid metabolism and the tumor microenvironment, including stromal cells and immune infiltrates. A thorough understanding of these interactions is essential for designing therapeutic strategies that address both metabolic dependencies and immune-mediated vulnerabilities. Furthermore, patient stratification and the implementation of personalized medicine approaches remain critical frontiers. Advanced methodologies, such as metabolomic profiling, functional imaging, and comprehensive genomic analyses, could facilitate precise patient classification according to individual metabolic phenotypes, thereby guiding tailored therapeutic interventions (Liu et al., 2025).

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers transformative potential in this context by integrating multidimensional datasets encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and imaging modalities to optimize patient stratification and treatment planning. AI-driven models can identify metabolic biomarkers, predict therapeutic responses, and simulate potential compensatory mechanisms in cancer cells. Moreover, AI-enabled monitoring tools could capture dynamic metabolic alterations during therapy, allowing real-time adjustments to enhance treatment efficacy, translating these insights into clinical practice necessitates several strategic actions. Amino acid profiling and metabolic phenotyping could be incorporated into diagnostic workflows to identify metabolic vulnerabilities in breast cancer patients at earlier stages. AI-assisted predictive frameworks may support the design of individualized metabolic therapies tailored to the heterogeneity of breast cancer subtypes. Clinical trials should emphasize combinatorial regimens that integrate metabolic inhibitors with immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy to rigorously evaluate their capacity to overcome resistance mechanisms. Additionally, therapeutic modulation of amino acid availability can directly influence mitochondrial function by restricting substrates essential for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Consequently, personalized rehabilitation strategies targeting mitochondrial health may be particularly relevant for patients receiving amino acid metabolism-targeted therapies. Holistic rehabilitation programs—including dietary modulation, structured physical activity, and mitochondrial-supportive nutraceuticals—merit systematic investigation as potential avenues to enhance metabolic resilience, therapeutic outcomes, and overall well-being in this patient population (Liu et al., 2025).

7.4. Recommendations Across Reviewed Papers

Since their discovery in the 1930s, fluorinated polymers have been extensively investigated due to their unique combination of chemical, thermal, and mechanical properties, as well as exceptional durability and weather stability. Polymers such as poly (vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) and its copolymers, with ferroelectric, pyroelectric, and piezoelectric properties, have been applied in biomedical fields including tissue engineering, artificial muscle actuators, drug delivery, and advanced devices. However, despite these promising features, critical gaps remain in tailoring their properties to meet specific biomedical requirements, particularly for in vivo applications where the interaction with complex biological systems may alter performance. Further research is necessary to optimize biocompatibility, mechanical integrity, and functional stability under physiological conditions (Cardoso et al., 2018b).

Similarly, pH-responsive polymers have demonstrated versatile applications in drug delivery and nanostructure design, including hydrogels, nanogels, hollow spheres, and cross-linked micelles. Although these systems show potential for controlled release and targeted therapy, there remain significant challenges in predicting their behavior in dynamic biological environments, such as variations in local pH, enzymatic degradation, and protein interactions. Additionally, their in vivo stability, scalability of synthesis, and long-term biocompatibility require further systematic investigation. These limitations highlight opportunities for designing smarter, more robust polymers that respond predictably under physiological conditions (Kocak, Tuncer and Bütün, 2017).

In the context of breast cancer therapy, conventional chemotherapeutics are hindered by poor selectivity, limited tumor penetration, systemic toxicity, and multidrug resistance. Polymeric nanoparticles (P-NPs) offer enhanced tumor targeting, intracellular delivery, and controlled drug release. Nevertheless, substantial gaps persist in translating preclinical success to clinical efficacy. Key challenges include understanding long-term biodistribution, interactions with serum proteins, and variability in tumor microenvironments that may compromise drug delivery efficiency. Moreover, the design of personalized or combination therapies using P-NPs remains largely unexplored, leaving room for future research to optimize therapeutic outcomes and minimize off-target effects (Grewal et al., 2021).

Collectively, while fluorinated and pH-responsive polymers, along with polymeric nanoparticles, demonstrate substantial promise in cancer therapy, critical knowledge gaps remain in predicting in vivo performance, achieving robust and reproducible responses, and integrating these systems into personalized treatment strategies. Addressing these gaps is essential to advance next-generation polymer-based therapeutics, enabling safer, more effective, and highly targeted interventions for breast cancer and other diseases.

8. Conclusion

Breast cancer therapy continues to face profound limitations stemming from the non-selective nature of conventional chemotherapy, poor biodistribution, and the emergence of multidrug resistance. The integration of nanotechnology, particularly amino acid–based polymeric carriers, offers a transformative strategy to overcome these barriers. Evidence from preclinical findings consistently demonstrates their superior biocompatibility, biodegradability, and capacity for stimuli-responsive, targeted delivery. These systems not only improve drug solubility and stability but also enable precise intracellular release and the potential for combinational therapies, thereby addressing several long-standing challenges in oncology.

Nonetheless, current literature highlights persistent obstacles in clinical translation, including nanoparticle stability, large-scale manufacturing, tumor heterogeneity, and patient variability. Moreover, discrepancies in release profiles and tumor penetration performance underscore the complexity of aligning laboratory outcomes with clinical efficacy. Metabolomic insights into amino acid dysregulation further enrich the therapeutic landscape, yet they also reveal the heterogeneity of breast cancer and the need for patient stratification strategies.

Future research must therefore prioritize the integration of polymer science with systems biology, computational modeling, and AI-guided design to tailor therapies to individual metabolic and genetic signatures. Furthermore, expanding preclinical validation into well-designed clinical trials is critical to bridge the gap between laboratory promise and patient benefit.

In conclusion, amino acid–based polymeric nanocarriers represent a promising frontier in precision medicine for breast cancer. While substantial progress has been achieved, their ultimate impact will depend on resolving translational challenges and harnessing multidisciplinary approaches. By addressing these gaps, the field can advance toward safer, more effective, and personalized cancer therapeutics.

Author Contributions

Ghina Al-Atef: Writing- original draft & editing. Hamad S Alyami: Review original draft, Conceptualization, Resources, project administration, Supervision.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for funding this work under the Easy Funding Program grant code (NU/EFP/4587/13/25).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Statement: Not applicable.

References