Rui-Yang Ju applied the YOLOv8 deep learning algorithm with data augmentation for pediatric wrist fracture detection. The model was trained and evaluated on the **GRAZPEDWRI-DX dataset** containing **20,327 X-ray images from 6,091 patients**. It achieved a state-of-the-art performance with **mAP50 of 0.638**, surpassing improved YOLOv7 (0.634) and original YOLOv8 (0.636). The main limitation is that the system is currently implemented only as a **macOS app**, requiring future expansion to iOS/Android and validation on other fracture types for broader clinical use [

5].Kosrat Dlshad Ahmed proposed a machine learning-based system for bone fracture detection using preprocessing, Canny edge detection, GLCM feature extraction, and classifiers (Naïve Bayes, Decision Tree, Nearest Neighbors, Random Forest, and SVM). The method was applied on a dataset of 270 X-ray images of broken and unbroken leg bones. The algorithms achieved accuracies ranging from 0.64 to 0.92, with SVM performing best. However, the study is limited by the small dataset size and potential generalization issues in real-world clinical use [

6]. Kritsasith Warin evaluated CNN-based models (DenseNet-169, ResNet-152, Faster R-CNN, and YOLOv5) for multiclass detection and classification of maxillofacial fractures. The study used a retrospective dataset of 3,407 CT maxillofacial bone window images collected from a trauma center between 2016–2020. DenseNet-169 achieved an overall classification accuracy of 0.70, and Faster R-CNN reached an mAP of 0.78, outperforming YOLOv5. The study’s limitations include reliance on retrospective data from only two institutions, single-view CT images, and limited resolution (512×512 pixels), which may restrict generalizability [

14].Jie Li R developed a YOLO deep learning model for automatic detection and classification of bone lesions on full-field radiographs. The model was trained on a retrospective dataset of 1,085 bone tumor radiographs and 345 normal radiographs collected from two centers (2009–2020). It achieved a detection accuracy of 86.36% (internal) and 85.37% (external), with Cohen’s kappa score up to 0.8187 for four-way classification. The main limitations include retrospective single-modality data, exclusion of spine/skull cases, lack of clinical factors (age, sex, lesion location), and reliance on 1024×1024 resolution requiring large GPU memory [

15].Mathieu Cohen evaluated a deep neural network–based AI model for wrist fracture detection on radiographs. The retrospective dataset included 637 patients (1,917 radiographs) with wrist trauma collected between 2017–2019. The AI achieved a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 96%, outperforming non-specialized radiologists (76% sensitivity), while AI+radiologist reports further improved sensitivity to 88%. Limitations include lack of patient demographic data, lower accuracy for non-scaphoid carpal fractures, and reliance on retrospective single-center data [

16].Young-Dae Jeon developed a YOLOv4-based AI system combined with 3D reconstructed CT images for fracture detection and visualization. The model was trained and tested on tibia and elbow CT image datasets, achieving average precision of 0.71 (tibia) and 0.81 (elbow) with IoU scores of 0.6327 and 0.6638. The system provided intuitive red mask overlays on 3D bone reconstructions to aid surgeons in diagnosis. Limitations include restricted evaluation to tibia and elbow data and the need for larger, multi-regional CT datasets and clinical trials for validation [

17].Amanpreet Singh developed a CNN-based deep learning model with Grad-CAM for detecting scaphoid fractures, including occult cases, from wrist radiographs. The dataset consisted of 525 X-ray images (250 normal, 219 fractured, 56 occult) collected from the Department of Orthopedics, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal. The model achieved 90% accuracy (AUC 0.95) for two-class and 90% accuracy (AUC 0.88) for three-class classification. Limitations include use of a relatively small, single-center dataset without segmentation, requiring further validation on larger, multi-center cohorts [

17].Cun Yang developed a deep-learning based AI algorithm to detect nasal bone fractures from CT images. The dataset included 252 patient CT scans collected between January 2020 and January 2021. The AI model achieved 84.78% sensitivity, 86.67% specificity, and 0.857 AUC, while also improving reader accuracy to 92% AUC when aided by AI. Limitations include reduced benefit for highly experienced radiologists and reliance on a single-center dataset requiring broader validation [

18].Huan-Chih Wang proposed a deep learning system combining YOLOv4 for fracture detection and ResUNet++ for cranial/facial bone segmentation. The dataset included 1,447 head CT studies (16,985 images) for detection and 1,538 CT images for segmentation, tested on 192 CT studies (5,890 images). The model achieved 88.66% sensitivity, 94.51% precision, and 0.9149 F1 score, with segmentation accuracy of 80.90%. Limitations include use of sparse data, lower sensitivity for facial fractures, and need for validation with broader, multi-center datasets [

19].Nils Hendrix developed a CNN-based AI algorithm to detect scaphoid fractures on multi-view radiographs and compared its performance with five musculoskeletal radiologists. The study used four datasets from two hospitals (total: 19,111 radiographs from 4,796 patients) for training and testing. The algorithm achieved 72% sensitivity, 93% specificity, 81% PPV, and 0.88 AUC, performing at the level of expert radiologists while reducing reading time. Limitations include possible selection bias due to lack of CT/MRI confirmation for all cases, simplified model architecture across views, and missed occult fractures [

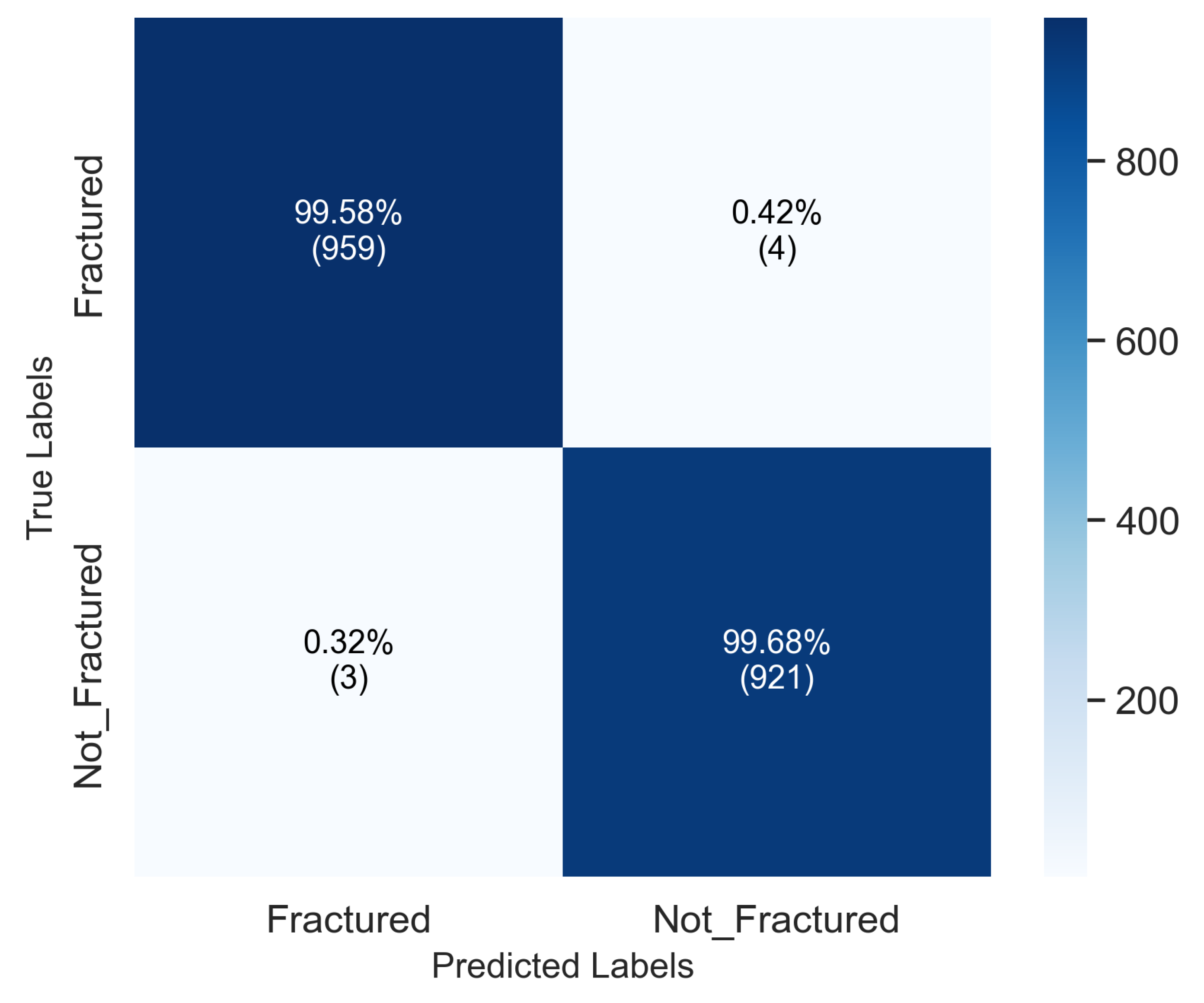

20]. Soaad M. Naguib proposed a deep learning–based computer-aided diagnosis system using AlexNet and GoogleNet to classify cervical spine injuries as fractures or dislocations. The model was trained on a dataset of 2009 X-ray images (530 dislocation, 772 fracture, 707 normal). It achieved 99.56% accuracy, 99.33% sensitivity, 99.67% specificity, and 99.33% precision. Limitations include lack of external validation, reliance on X-ray only without CT/MRI confirmation, and absence of fracture subtype classification [

21].Chun-Tse Chien applied the YOLOv9 algorithm for pediatric wrist fracture detection using the GRAZPEDWRI-DX dataset with data augmentation techniques. The model achieved a mAP 50–95 of 43.73%, improving by 3.7% over the prior state-of-the-art. Limitations include insufficient data for “bone anomaly” and “soft tissue” classes and restriction to pediatric wrist fractures only [

22].