Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Efficient Operation of an Aircraft for Fuel Saving and Emission Reduction

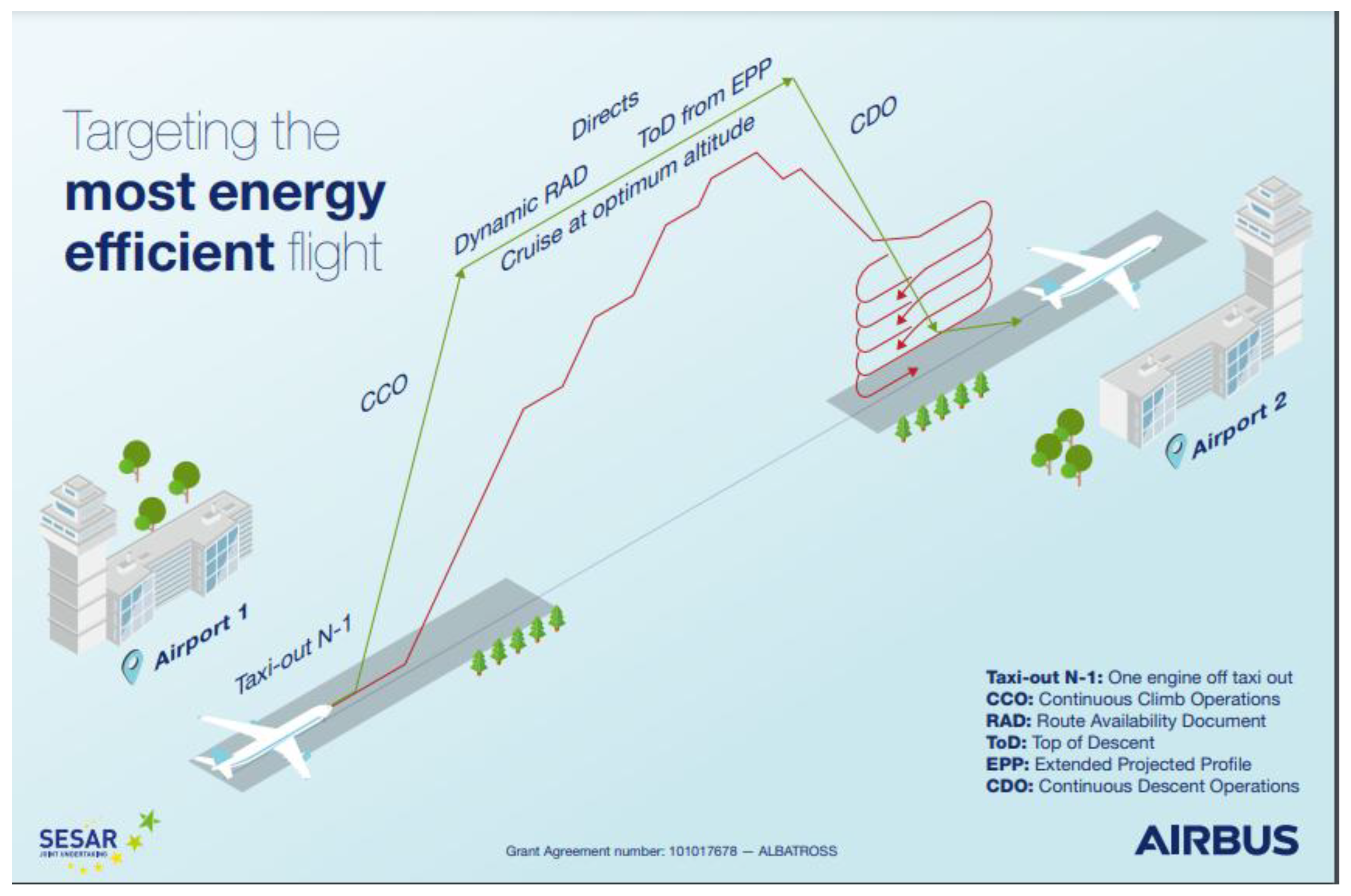

- Taxi on the airport: this is the fuel needed to start the engines and then taxi to the runway. This is a first opportunity to save fuel. Aircraft engines are designed to be efficient in flight, but not during idle on the ground. Airports and air traffic providers are working on projects to optimize the movements and flow of aircraft on the ground to minimize the time from gate to take-off.

- Take-off and climb to an optimum cruise level: each and every flight is different. The climb performance of an aircraft depends on the actual weight, the weather conditions and air traffic situation. The crew is able to calculate with the onboard systems the most efficient climb profile. The cruise altitude or flight level is not primarily the decision of the flight crew. The air traffic controller assigns a certain level, climb rate and speed based on capacity of airspace and trajectory of the aircraft.

- Cruise flight: with regards to efficiency, the cruise altitude needs to change during the flight. This is the result of burning fuel and losing weight. Fuel is 15-40% of the take-off mass of an aircraft. By burning fuel in cruise, the aircraft becomes lighter and able to climb to higher altitudes, where flight is more efficient. This, in turn, offers the opportunity to burn less fuel. Today, an aircraft climbs in steps. By improving the data-transmission between airplanes and air traffic control, the controller is able to assign the aircraft the most efficient flight level. In addition, the routing could be optimized during the flight. Depending on the air traffic situation, the controller could be looking for a direct routing being assigned to a certain flight; this avoids extra fuel burn.

- Descent: the so-called Continuous Descent is the most efficient way for the final phase of the flight. If the crew sets the thrust levers to idle and the aircraft then glides to the airport, fuel is saved and emissions are reduced. But, in many cases, aircraft today have to reduce the altitude through several steps (step-down descent) rather than in a continuous way (Continuous Descent Operations, CDO). This results in inefficient level flying at lower altitudes. The flight management system of the aircraft offers the crew the possibility to calculate the most efficient descent and define a certain point of top of descent for the flight. The air traffic controller then has to check if the traffic situation permits this approach. Consequentially, by jointly optimizing the flightpath, the resulting actual descent profile could be as close as possible to the optimum descent one.

- Holdings: one of the most inefficient flight phases in commercial aviation operations are holdings, i.e. the waiting in near-circular flight until a landing slot is available. For example, an A320-family aircraft burns approximately 100 kg of fuel in a four minutes standard holding.

- Movement to the parking position and ground power: similar to the situation on departure, an efficient surface movement guidance after landing helps saving fuel. The power supply during the turnaround of the aircraft is another opportunity to save fuel. The aircraft could be powered on the ground either by a connector and electricity from the airport or by running the so called APU, Auxiliary Power Unit onboard the aircraft, which is burning kerosene.

3. Terminal Maneuvering Area (TMA) Approaches to Fuel Saving and Emissions Reduction

4. CO2 and Non-CO2 Emission Modelling

Contrails Modelling

5. Emissions Reduction

5.1. Multi-Objective Optimization

5.2. Simulation-Based Evolutionary Optimization

5.3. Air Traffic Flow Mangaement with Emissions Considerations

6. Metrics for Evaluating Impact

- −

- Radiative Forcing (RF), which indicates the instantaneous change in the net (down minus up) radiative flux (W/m²) due to an atmospheric perturbation. The concept of radiative forcing is central to understanding how an emission perturbs the climate system. A common formulation for CO₂ is:

- −

- Global Warming Potential (GWP), which is the integrated radiative forcing over a specified time horizon normalized to the forcing of CO₂. GWP is defined over a time horizon τ as:

- −

- Global Temperature change Potential (GTP), which is the change in near-surface temperature at a given future time due to an emission pulse, relative to CO₂.

- −

- Average Temperature Response (ATR), referring to the time-averaged temperature change over a defined period following an emission pulse. ATR links the integrated temperature response to a pulse emission. It is often calculated as:

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masiol, M. and Harrison, R.M., 2014. Aircraft engine exhaust emissions and other airport-related contributions to ambient air pollution: A review. Atmospheric Environment, 95, pp.409-455.

- A. Errico and V. Di Vito, “Performance-based navigation (PBN) with continuous descent operations (CDO) for efficient approach over highly protected zones”, 24th Saint Petersburg International Conference on Integrated Navigation Systems (ICINS), St. Petersburg, Russia, pp. 1-8, 2017.

- Lee, D.S., Pitari, G., Grewe, V., Gierens, K., Penner, J.E., Petzold, A., Prather, M.J., Schumann, U., Bais, A., Berntsen, T. and Iachetti, D., 2010. Transport impacts on atmosphere and climate: Aviation. Atmospheric environment, 44(37), pp.4678-4734.

- Kinsey, J.S., 2009. Characterization of emissions from commercial aircraft engines during the Aircraft Particle Emissions eXperiment (APEX) 1 to 3. Office of Research and Development, US Environmental Protection Agency.

- Kinsey, J.S., Dong, Y., Williams, D.C. and Logan, R., 2010. Physical characterization of the fine particle emissions from commercial aircraft engines during the Aircraft Particle Emissions eXperiment (APEX) 1-3. Atmospheric Environment, 44(17), pp.2147-2156.

- Kinsey, J.S., Hays, M.D., Dong, Y., Williams, D.C. and Logan, R., 2011. Chemical characterization of the fine particle emissions from commercial aircraft engines during the Aircraft Particle Emissions eXperiment (APEX) 1 to 3. Environmental science & technology, 45(8).

- Mazaheri, M., Johnson, G.R. and Morawska, L., 2011. An inventory of particle and gaseous emissions from large aircraft thrust engine operations at an airport. Atmospheric Environment, 45(20), pp.3500-3507.

- Hudda, N., Simon, M.C., Zamore, W., Brugge, D. and Durant, J.L., 2016. Aviation emissions impact ambient ultrafine particle concentrations in the greater Boston area. Environmental science & technology, 50(16), pp.8514-8521.

- Anderson, B.E., Chen, G. and Blake, D.R., 2006. Hydrocarbon emissions from a modern commercial airliner. Atmospheric Environment, 40(19), pp.3601-3612.

- Bond, T.C., Streets, D.G., Yarber, K.F., Nelson, S.M., Woo, J.H. and Klimont, Z., 2004. A technology-based global inventory of black and organic carbon emissions from combustion. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 109(D14).

- Timko, M.T., Albo, S.E., Onasch, T.B., Fortner, E.C., Yu, Z., Miake-Lye, R.C., 641 Canagaratna, M.R., Ng, N.L. and Worsnop, D.R., 2014. Composition and sources of the organic particle emissions from aircraft engines. Aerosol Science and Technology, 48(1), pp.61-73.

- Ungeheuer, F., Caudillo, L., Ditas, F., Simon, M., van Pinxteren, D., Kılıç, D., Rose, D., Jacobi, S., Kürten, A., Curtius, J. and Vogel, A.L., 2022. Nucleation of jet engine oil vapours is a large source of aviation-related ultrafine particles. Communications Earth & Environment, 3(1), p.319.

- Yang, X., Cheng, S., Lang, J., Xu, R. and Lv, Z., 2018. Characterization of aircraft emissions and air quality impacts of an international airport. Journal of environmental sciences, 72, pp.198-207.

- https://mediacentre.airbus.com/home.

- JP. Clarke, NT. Ho, L. Ren, JA. Brown, KR. Elmer, K. Zou, C. Hunting, DL. McGregor, BN. Shivashankare, KO. Tong, AW. Warren, JK. Wat, “Continuous Descent Approach: Design and Flight Test for Louisville International Airport”, Journal of Aircraft, Vol. 41, No. 5, pp. 1054–1066, 2004.

- JP. Clarke, J. Brooks, G. Nagle, A. Scacchioli, W. White, SR. Liu, “Optimized Profile Descent Arrivals at Los Angeles International Airport”, Journal of Aircraft, 2015.

- D. Delahaye, S. Puechmorel, P. Tsiotras, E. Feron, “Mathematical Models for Aircraft Trajectory Design – A Survey”, Lecture notes in Electrical Engineering, Vol. 3, No. 12, pp. 205-247, 2014.

- A. Errico, V. Di Vito, C. Parente and G. Petruzzi, “Algorithms for Automatic Elaboration of Optimized Trajectories for Continuous Descent Operations”, International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, Vol. 6, Issue 6, June 2017.

- ICAO, “Rules of Air”, International Civil Aviation Organisation, 2005.

- ICAO, “DOC 9613 – Performance-based Navigation Manual”, International Civil Aviation Organisation, 3rd edition, Montréal, Quebec (Canada), 2012.

- EUROCONTROL, “Continuous Descent Approach – Implementation Guidance Information”, May 2008; www.eurocontrol.int/environment.

- ICAO, “Doc 4444 – PANS-ATM, Procedures for Navigation Services and Air Traffic Management”, International Civil Aviation Organisation, 16th Edition, 2016.

- ICAO, “DOC 9905 – Required Navigation Performance Authorization Required (RNP AR) Procedure Design Manual”, International Civil Aviation Organisation, First Edition, 2009.

- A. Errico and V. Di Vito, “Algorithms and system for curved and continuous descent trajectories improving fuel efficiency in TMA”, 31st Congress of the International Council of Aeronautical Sciences, ICAS 2018, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, September 09-14, 2018.

- ICAO, “DOC 9931/AN/476 – Continuous Descent Operations Manual”, International Civil Aviation Organisation, Montreal, 1st edition, 2010.

- A. Errico and V. Di Vito, “Study of Point Merge technique for efficient Continuous Descent Operations in TMA”, IFAC-PapersOnLine, Volume 51, Issue 9, Pages 193-199, 2018.

- B. Favennec, E. Hoffman, A. Trzmiel, F. Vergne, K. Zeghal, “The Point Merge Arrival Flow Integration Technique: Towards More Complex Environments and Advanced Continuous Descent,” 9th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration and Operations Conference (ATIO), South Carolina, 2009.

- EUROCONTROL Experimental Centre (EEC), “Point Merge Integration of Arrival Flows Enabling Extensive RNAV Application and Continuous Descent”, Version 2.0, July 2010.

- User Manual for the Base of Aircraft Data (BADA) Revision 3.11, Eurocontrol Experimental Centre (EEC) Technical/Scientific Report No. 13/04/16-01, Brétigny-sur-Orge, France, 2013.

- ICAO Aircraft Engine Emissions Databank (http://easa.europa.eu/node/15672).

- ICAO, Annex 16 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation - Environmental Protection - Volume II: Aircraft Engine Emissions, The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2008.

- A. Wulff, J. Hourmouziadis, Technology review of aero engine pollutant emissions, Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 1 (1997) 557-572.

- A. Gardi, R. Sabatini, T. Kistan, Y. Lim, S. Ramasamy, 4-Dimensional trajectory functionalities for air traffic management systems, in: Proceedings of Integrated Communication, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS 2015), Herndon, VA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Hupe, B. Ferrier, T. Thrasher, C. Mustapha, N. Dickson, T. Tanaka, et al., ICAO Environmental Report 2013: Destination Green – Aviation and Climate Change, ICAO Environmental Branch, Montreal, Canada, 2013.

- R.L. Martin, et al., Appendix D. Boeing Method 2 Fuel Flow Methodology Description – Presentation to CAEP Working Group III Certification Subgroup, in: S.L. Baughcum, T.G. Tritz, S.C. Henderson, D.C. Pickett (Eds.), Scheduled Civil Aircraft Emission Inventories for 1992: Database Development and Analysis – NASA Contractor Report 4700, NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, VA, USA, 1996.

- D. Dubois, G. C. Paynter, “Fuel flow method 2” for estimating aircraft emissions, SAE Technical Paper 2006-01-1987, 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. J. J. Ruijgrok, D.M. van Paassen, Elements of Aircraft Pollution, 3rd ed., VSSD, Delft, Netherlands, 2012.

- C. Celis,V. Sethi,D. Zammit-Mangion, R. Singh, P. Pilidis, Theoretical optimal trajectories for reducing the environmental impact of commercial aircraft operations, J. Aerosp. Technol. Manag. 6 (2014) 29-42. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E. Die Entstehung von Eisnebel aus den Auspuffgasen von Flugmotoren; Verlag, R. Oldenbourg: München, Germany, 1941; Volume 44, pp. 1–15.

- Appleman, H. The formation of exhaust condensation trails by jet aircraft. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1953, 34, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.S. Lee, G. Pitari, V. Grewe, K. Gierens, J.E. Penner, A. Petzold, et al., Transport impacts on atmosphere and climate: aviation, Atmos. Environ. 44 (2010) 4678–4734. [CrossRef]

- Schumann, U. On conditions for contrail formation from aircraft exhausts. Meteorol. Z. 1996, 5, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, R.; Shariff, K. Contrail modeling and simulation. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2016, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F.; Grewe, V.; Gierens, K. Impact of hybrid electric aircraft on contrail coverage. Aerospace 2020, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization), 2008. Environmental Protection (Annex 16). In: Aircraft Engine Emission, International Standards and Recommended Practices, vol. 2, ISBN 978-92-9231-123-0.

- ICAO Aircraft Engine Emissions Databank https://www.easa.europa.eu/domains/environment/icao-aircraft-engine-emissions-databank.

- Iribarne, J. V., & Godson, W. L. (Eds.). Atmospheric thermodynamics (Vol. 6), 1981. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Pruppacher, H. R., & Klett, J. D. Microphysics of Clouds and Precipitation: Reprinted 1980, 2012. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Lee, D.S., Fahey, D.W., Foster, P.M., Newton, P.J., Wit, R.C.N., et al. Aviation and global climate change in the 21th century. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43,3520 - 3537.

- Haywood, J.M.; Allan, R.P.; Bornemann, J.; Forster, P.M.; Francis, P.N.; Milton, S.; Rädel, G.; Rap, A.; Shine, K.P.; Thorpe, R. A case study of the radiative forcing of persistent contrails evolving into contrail-induced cirrus. J. Geophys. Res Atmos. 2009, 114, D24201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterstrasser, S.; Gierens, K.; Sölch, I.; Lainer, M. Numerical simulations of homogeneously nucleated natural cirrus and contrail-cirrus. Part 1: How different are they? Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2017, 26(6), 621–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterstrasser, S., Gierens, K., Sölch, I., & Wirth, M. Numerical simulations of homogeneously nucleated natural cirrus and contrail-cirrus. Part 2: Interaction on local scale. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2017, 26(6), 643-661.

- Sölch, I.; Kärcher, B. Process-oriented large-eddy simulations of a midlatitude cirrus cloud system based on observations. Q. J. Roy. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärcher, B. Formation and radiative forcing of contrail cirrus. Nature communications 2018, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U. Schumann, Formation, properties and climatic effects of contrails, C.R. Phys. 6 (2005) 549–565. [CrossRef]

- G. Penin, Formation of Contrails, TU Delft, Delft, Netherlands, 2012.

- Pellegrini, A., Di Sanzo, P., Bevilacqua, B., Duca, G., Pascarella, D., Palumbo, R et al. (2020). Simulation-based evolutionary optimization of air traffic management. IEEE access, 8, 161551-161570.

- Hamdan, S., Cheaitou, A., Jouini, O., Jemai, Z., Alsyouf, I., & Bettayeb, M. (2019, April). An environmental air traffic flow management model. In 2019 8th international conference on modeling simulation and applied optimization (icmsao) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- M. Ponater, S. Marquart, R. Sausen, Contrails in a comprehensive global climate model: Parameterization and radiative forcing results, J. Geophys. Res. (2002). [CrossRef]

- A.G. Detwiler, A. Jackson, Contrail formation and propulsion efficiency, J. Aircr. 39 (2002) 638–644.

- M.L. Schrader, Calculations of aircraft contrail formation critical temperatures, J. Appl. Meteorol. 36 (1997) 1725–1728.

- J.A. Sorensen, S.A. Morello, H. Erzberger, Application of trajectory optimization principles to minimize aircraft operating costs, in: Proceedings of the 18th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, vol. 1, 1979, pp. 415–421.

- Camilleri, W., et al., "Design and validation of a detailed aircraft performance model for trajectory optimization," AIAA Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference, 2012.

- Gu, W., et al., "Towards the development of a multi-disciplinary flight trajectory optimization tool - GATAC," ASME Turbo Expo 2012, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Sammut, M., et al., "Optimization of fuel consumption in climb trajectories using genetic algorithm techniques," AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, 2012.

- Tsotskas, C., et al., "Biobjective optimisation of preliminary aircraft trajectories," 7th International Conference on Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization, 2013.

- Rao, A. V., "Survey of Numerical Methods for Optimal Control," Advances in the Astronautical Sciences, vol. 135, pp. 497-528, 2010.

- H. Zolata, C. Celis, V. Sethi, R. Singh, and D. Zammit-Mangion, A multi-criteria simulation framework for civil aircraft trajectory optimisation, in: Proceedings of ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition 2010 (IMECE2010), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2010, pp. 95–105. [CrossRef]

- C. Fichter, S. Marquart, R. Sausen, D.S. Lee, The impact of cruise altitude on contrails and related radiative forcing, Meteorol. Z. 14 (2005) 563–572. [CrossRef]

- B. Sridhar, H. Ng, N. Chen, Aircraft trajectory optimization and contrails avoidance in the presence of winds, J. Guid. Control Dyn. 34 (2011). 1577–1584. [CrossRef]

- N.Y. Chen, B. Sridhar, H.K. Ng, Contrail reduction strategies using different weather resources, in: Proceedings of AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference 2011 (GNC2011), Portland, OR, USA, 2011. [CrossRef]

- O. Deuber, M. Sigrun, S. Robert, P. Michael, L. Ling, A physical metric-based framework for evaluating the climate trade-off between CO2 and contrails — the case of lowering aircraft flight trajectories, Environ. Sci. Policy 25 (2013) 176–185. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lim, A. Gardi, R. Sabatini, Modelling and evaluation of aircraft contrails for 4-dimensional trajectory optimisation, SAE Int. J. Aerosp. (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.4271/2015-01-2538 (pp. Technical Paper 2015-01-2538). [CrossRef]

- Y. Lim, A. Gardi, M. Marino, R. Sabatini, Modelling and evaluation of persistent contrail formation regions for offline and online strategic flight trajectory planning, in: Proceedings of International Symposium on Sustainable Aviation (ISSA2015), Istanbul, Turkey, 2015.

- Shindell, D. T. & Faluvegi, G. S. The net climate impact of coal-fired power plant emissions. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (2010), 10, 3247–3260.

- Teoh, R., Schumann, U., Majumdar, A., & Stettler, M. E. (2020). Mitigating the climate forcing of aircraft contrails by small-scale diversions and technology adoption. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(5), 2941-2950.

- Jabali, O., Van Woensel, T., & De Kok, A. G. (2012). Analysis of travel times and CO2 emissions in time-dependent vehicle routing. Production and Operations Management, 21(6), 1060-1074.

- Niklaß, M., Grewe, V., Gollnick, V., & Dahlmann, K. (2021). Concept of climate-charged airspaces: a potential policy instrument for internalizing aviation's climate impact of non-CO2 effects. Climate Policy, 21(8), 1066-1085.

- Dahlmann, K., Grewe, V., Matthes, S., & Yamashita, H. (2023). Climate assessment of single flights: Deduction of route specific equivalent CO2 emissions. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 17(1), 29-40.

- Simorgh, A., Soler, M., González-Arribas, D., Linke, F., Lührs, B., Meuser, M. M., Dietmüller, S., Matthes, S., Yamashita, H., Yin, F., Castino, F., Grewe, V., and Baumann, S.: Robust 4D climate-optimal flight planning in structured airspace using parallelized simulation on GPUs: ROOST V1.0, Geosci. Model Dev., 16, 3723–3748. [CrossRef]

- Gierens, K. M., Lim, L., and Eleftheratos, K.: A review of various strategies for contrail avoidance, Open Atmospheric Science Journal, 2, 1–7, 2008.

- Grewe, V., Frömming, C., Matthes, S., Brinkop, S., Ponater, M., Dietmüller, S., Jöckel, P., Garny, H., Tsati, E., Dahlmann, K., Søvde, O. A., Fuglestvedt, J., Berntsen, T. K., Shine, K. P., Irvine, E. A., Champougny, T., and Hullah, P.: Aircraft routing with minimal climate impact: the REACT4C climate cost function modelling approach (V1.0), Geosci. Model Dev., 7, 175–201. [CrossRef]

- van Manen, J. and Grewe, V.: Algorithmic climate change functions for the use in eco-efficient flight planning, Transport. Res. D-Tr. E., 67, 388–405, 2019.

- Matthes, S., Grewe, V., Dahlmann, K., Frömming, C., Irvine, E., Lim, L., Linke, F., Lührs, B., Owen, B., Shine, K., Stromatas, S., Yamashita, H., and Yin, F.: A concept for multi-criteria environmental assessment of aircraft trajectories, Aerospace, 4, 42. [CrossRef]

- Matthes, S., Dietmüller, S., Dahlmann, K., Frömming, C., Yamashita, H., Grewe, V., Yin, F., and Castino, F.: Algorithmic climate change functions (aCCFs) V1.0A: Consolidation of the approach and note for usage, Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss., submitted, 2023.

- Campbell, S., Neogi, N., and Bragg, M.: An optimal strategy for persistent contrail avoidance, in: AIAA Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference and Exhibit, 18–21 August 2008, Honolulu, Hawaii, 6515, 2008.

- Yamashita, H., Yin, F., Grewe, V., Jöckel, P., Matthes, S., Kern, B., Dahlmann, K., and Frömming, C.: Newly developed aircraft routing options for air traffic simulation in the chemistry–climate model EMAC 2.53: AirTraf 2.0, Geosci. Model Dev., 13, 4869–4890. [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, B., Ng, H. K., and Chen, N. Y.: Aircraft trajectory optimization and contrails avoidance in the presence of winds, J. Guid. Control, 34, 1577–1584, 2011.

- Lührs, B., Linke, F., Matthes, S., Grewe, V., and Yin, F.: Climate impact mitigation potential of European air traffic in a weather situation with strong contrail formation, Aerospace, 8, 50. [CrossRef]

- Hartjes, S., Hendriks, T., and Visser, D.: Contrail mitigation through 3D aircraft trajectory optimization, in: 16th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, 13–17 June 2016, Washington, D.C., USA, 3908, 2016.

- Vitali, A., Battipede, M., and Lerro, A.: Multi-Objective and Multi-Phase 4D Trajectory Optimization for Climate Mitigation-Oriented Flight Planning, Aerospace, 8, 395. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H., Yin, F., Grewe, V., Jöckel, P., Matthes, S., Kern, B., Dahlmann, K., and Frömming, C.: Newly developed aircraft routing options for air traffic simulation in the chemistry–climate model EMAC 2.53: AirTraf 2.0, Geosci. Model Dev., 13, 4869–4890. [CrossRef]

- Simorgh, A., Soler, M., González-Arribas, D., Matthes, S., Grewe, V., Dietmüller, S., Baumann, S., Yamashita, H., Yin, F., Castino, F., Linke, F., Lührs, B., and Meuser, M. M.: A Comprehensive Survey on Climate Optimal Aircraft Trajectory Planning, Aerospace, 9, 146. [CrossRef]

- WMO: Guidelines on ensemble prediction systems and forecasting, edited by: Svoboda, M., Hayes, M., and Wood, D. A., World Meteorological Organization Weather Climate and Water, 1091, ISBN 978-92-63-11091-6, 2012.

- AMS-Council: Enhancing weather information with probability forecasts, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 89, 1049–1053, 2008.

- Bauer, P., Thorpe, A., and Brunet, G.: The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction, Nature, 525, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Simorgh, A., Soler, M., González-Arribas, D., Matthes, S., Grewe, V., Dietmüller, S., ... & Meuser, M. M. (2022). A comprehensive survey on climate optimal aircraft trajectory planning. Aerospace, 9(3), 146.

- Morante, D.; Sanjurjo Rivo, M.; Soler, M. A Survey on Low-Thrust Trajectory Optimization Approaches. Aerospace 2021, 8, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D.E. Optimal Control Theory: An Introduction; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- González Arribas, D. Robust Aircraft Trajectory Optimization under Meteorological Uncertainty. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, July 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).