1. Introduction

In his book "The Computer and the Brain" von Neumann [

1] examined the working of the brain from an abstract standpoint and concluded that the logical rules followed by the brain are likely to be different from those of normal logic. In this paper we will show that the hidden combination rules of the brain’s information carrying signals rules that defines the logical system of the brain can found from the study of the combination rules of signals produced in a recently proposed topological brain model [

2]. The model can generate all observed brain-like excitations using a global unconventional method. We will show that whether the extract logical rules of brain signal combination include the law of excluded middle or not can be decided by observations. The observational evidence required is available and it shows that the law of excluded middle does not hold in the logical system of the brain. To present these results some background facts about the brain and the topological brain model are required which we summarise.

1.1. Facts About the Brain

The human brain weighs about 1.2 kg and is an organ of incredible complexity. About 20% of its volume is occupied by blood vessels which supply the oxygen and glucose to the brain to meet its high energy needs to function. The brain consumes 20% of the of the energy intake of the body. The brain also has a cooling system of ventricles that carry cerebral fluids that circulate it and prevent it from getting overheated.

The human brain has over one hundred billion nerve cells (neurons). Each neuron has a body, the soma, with several information receiving protrusions, dendrites, attached to it, and one nerve fibre, the axon, that carries away brain signals generated by the neuron to another neuron. These signals, known as action potentials, are voltage pulses. Individual neurons are linked together by axons that at the end of axon there is a gap, called a synapse. After the gap there is a receiving dendrite terminal of the linked neuron. The axon terminal end of one neuron is an enlarged bulb that contains a collection of vesicle sacs. Each sac can contain over one thousand molecules known as neurotransmitters. When a voltage pulse signal carried by the axon approaches a synapse gap that links it to another neuron, a stream of neurotransmitter molecules are released into the gap. These molecules cross the gap and connect with special receptor cells of the dendrite of the linked neuron. Different mix of neurotransmitters could be present in each vesicle. Depending on the nature of the neurotransmitters receptors, the voltage signals is either re-established, if the molecules are excitatory or is stopped from entering the linked neuron, if the molecules are inhibitory,. If the signal is allowed to enter the neuron, then complex chemical processes are initiated that can trigger the creation of additional connectivity links for signals of sufficient strength. Brain signals from sensory organs carry information but how this signal information is carried by a collection of neurotransmitter molecules is a mystery.

How does this vast assembly of individual units’ functioning on their own without intervention allow us to see, hear, feel emotions, have memories, learn skills, make discoveries compose music, dance and have consciousness? Patient and careful research has thrown light on many of these questions. But there is vast ignorance in our understanding. These are theoretical challenges.

We list some of these challenges, they are: to understand how the brain can produce all its observed electrical signals, how does it produces its own communication code, how is the information carried by signals recorded as memories, and how are memories retrieved. Currently answers to these questions are not known.

2. The Topological Surface Network

In a recent paper [

2] a special topological brain model (TBM), a surface network with surface spin-half particles, was constructed which could generate all observed brain-like excitations. The surface network had two layers of topology. One came from its connectivity and the other from its surface spin-half particles. These topological features could be represented by two topological numbers. Signals were produced by subunits in response to local topology changing surface deformations that reduced the topology of the subunit to that of a sphere. The surface deformations introduced were defined by a set of deformation parameter values. These unknow values represented the network’s self-generated information code. The signals produced in this way, carried information of how they were created as well as the topology numbers of the signal generating subunit that creates them.

The system’s response to such topology changing input signals is determined by a dynamical law of the network that show that a variety of responses, depending on the signal parameter values, are possible. They include one dimensional propagating voltage pulse signals of different types or localised transient excitations.

The network surface was represented by a Riemann surface with spin structure and the signals producedwere described in terms of the Riemann theta function with characteristics. Thus to describe the TBM some facts about Riemann surfaces and the Riemann theta function are required. The summary of facts that we give closely follow the account of these topics given in Sen [

2,

3].

We begin our discussion by proving [

2,

3] that the surface of the surface network can be chosen to exactly represents the brain’s unknown complex topological connectivity and that it can be represented as a Riemann surface. We start the proof by considering a brain connectome. A connectome represents the connectivity architecture of a biological brain in which neurons are represented as points and axons as lines. If we replace each line of the connectome by a tube and each nodal point by a nodal region we will create a surface representation of the connectome: an enormously complex unknown surface embedded in three dimensions. The surface constructed is compact. At this point topological ideas can be used to simplify the system. The theorem of classifying surfaces [

4] tells us that any unknown compact surface no matter how complicated is topologically equivalent to an orderly set of an unknown number of connected doughnuts or a sphere with an unknown number of loop handles. If the surface is assumed to be smooth it can be represented by a Riemann surface. We use the doughnut representation for the Riemann surface of the network that we now known exactly captures the topological connectivity of the brain.

2.1. Riemann Surface Variables

A Riemann surface

of unknown genus

g is a geometric representation a algebraic polynomial equation

of two complex variables

. It can be represented as a collection of

g linked doughnut surfaces . The smoothness of the surface follows from the fact that the surface is constructed from a polynomial equation [

5].

A genus g Riemann surface has two properties:it has topological connectivity and it has smoothness. The topological connectivity property can be captured by loop coordinates round the surface of the g connected doughnuts. There is a set of of natural topological closed loop coordinates that are used to represent the system’s connectivity. The loops go round the tubes while the loops go round the central hole of the doughnut as shown in the figure. These loops reflect the multiple periodic nature of . The sets of loops shown in the figure are said to be orthogonal.

The smoothness of

is captured by

g mathematical objects called one-forms

. The existence of these

g oner-forms was proved by Riemann [

6]. A one-form is an object that can be integrated. Its smoothness is captured by the smoothness of the coefficients

, where

z is a point on

.

Thus

, as a mathematical Riemann surface, can be described by the choice of its

topological coordinates

that describe closed loops and its smoothness is described by a specific set of

g smooth one-forms.(

Figure 1)

2.2. The Riemann Theta Function

We next define the Riemann Theta function

. [

11]. Thisfunction is used to study responses of the surface network due to input pinch deforming signals. We first define its variables and then define the function. The variables and parameters of

are constructed from those of

and its spin structure. We start with the parameters. An important set of parameters of

are those present in a symmetric matrix

, with positive imaginary values, called the period matrix

which is defined by integrating the one forms

over the closed loop

. We have

. It is a set of

complex numbers.

The second set of parameters of are a set of positive or negative integers that can range between ). The integers can be interpreted as winding numbers that come from integrating one forms over closed the loops. These integrals are normalised to be one when and are zero otherwise. Thus they produce positive or negative integer values as they "wind" round the loops of the Riemann surface in the clockwise or anticlockwise directions. We next turn to the variables of the theta function.

has g complex variables that are generated from the one complex variable z used to define a point on . They are given by . In words are generated by integrating the one form between a fixed point 0 on to a variable point z on its surface.

Finally has, as stated before, discrete variables called its characteristics, , called characteristics that describe the spin structure of , in a precise way. Topologically distinct spin structures of correspond to different choices of characteristic values.We will make this link clear shortly. Each characteristic can take one of two values, namely zero or half.

We now define the Riemann theta function

,

Notice the characteristics are related to the loops of . A characteristic can now be given a geometric interpretation produces. A traversal round a loop adds to or variables of the Theta function. The integer numbers can be interpreted as the windings number of the one-forms round loops. The emergence of when an loop is completed means the system has spin-half surface particles as a spin-half particle is a quantum object which changes sign under rotation. This geometric result links characteristics of the theta function to spin structures on .

An important observation for our discussions of signals is that we can now properly write down the two topological numbers of

mentioned before. They are

where

g is the genus of

and

W is its spin topology number.

W is defined in terms of the characteristics of the Riemann theta function by the formula,

. A given set of characteristics is said to be even or odd depending on whether

. All signals have odd characteristics [

2].

2.3. The Topological Brain Model

We now define the Topological Brain Model by two postulates.

Postulate 1

The TBM surface network is represented by a charged Riemann surface with spin structure of unknown genus g associated with a hyperelliptic equation. The surface exactly captures the topological connectivity of any brain surface connectome

Postulate 2

The surface is dynamic and evolving. The response of the surface to input signals that are local topology changing pinch deformations that reduce the topology of a subunit to that of a sphere and can be initiated by mechanical, electrical or chemical means, is determined by a dynamical law that states that both input signals and responses to them must respect the Riemann surface structure of . Local pinch deformation signals reduce the circumference of a loop of to zero at a point.

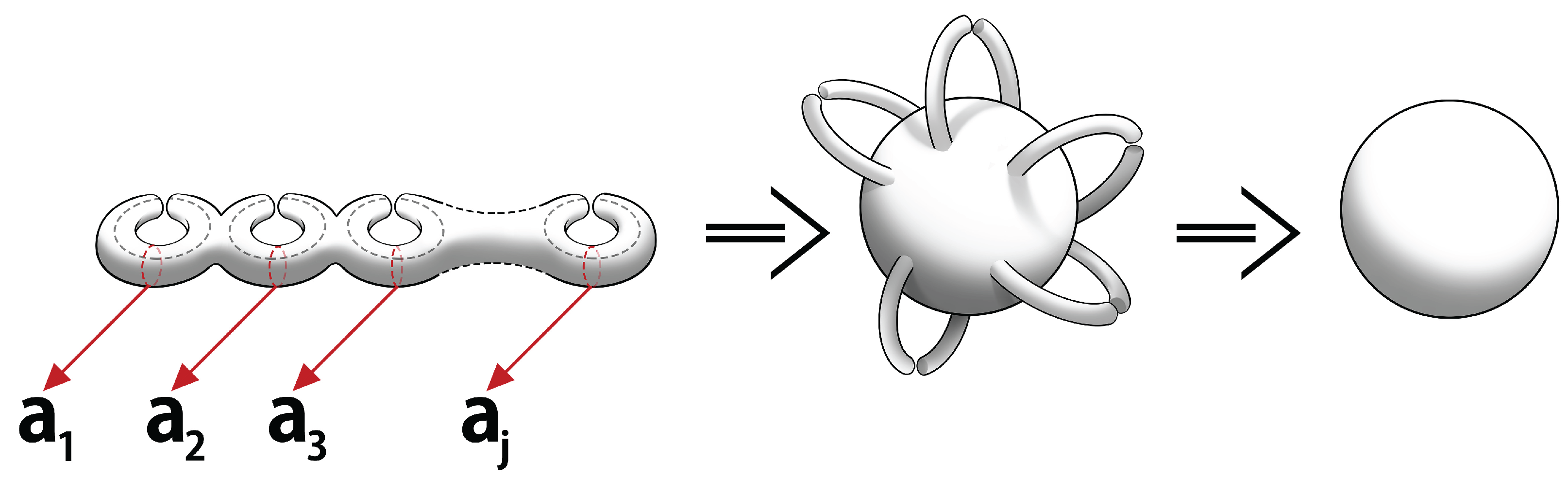

The way a pinch deformation reduces the topology is shown in the figure,

Figure 2.

Pinch Deformation reduce topology of subunit to that of a sphere.

Figure 2.

Pinch Deformation reduce topology of subunit to that of a sphere.

The dynamical law’s requirement that responses to pinch deformations and pinch deformations themselves must respect the Riemann surface structure is implemented by using the a non-linear algebraic Fay trisecant identity for Riemann theta functions .

Let us explain why the identity has to be satisfied and then explain how the identity it leads to Riemann theta function solutions of non-linear differential equations. The Fay identity was discovered while trying to find a way to resolve a mismatch of the number of parameters used to describe a Riemann surface in two different ways. In one description, the moduli space of a genus g Riemann surface has complex parameters while in the other description a Riemann theta function, defined as a holomorphic section over the Jacobian of the Riemann surface is used. In this description the theta function has complex parameters in its period matrix. Thus for the theta function period matrix has more parameters than required and hence an arbitrary theta function with an arbitrary period matrix will not be associated with a Riemann surface. The theta function parameters cannot be independently chosen but must satisfy constraints if it is to represent a Riemann surface.

A way to solve this mismatch problem was found. It was required the theta function to satisfied a non-linear algebraic identity called the Fay trisecant identity [

11,

15,

16]. If this constraint was satisfied by a Riemsnn theta function then it would represent a Riemann surface.

The law as stated is too general. In order to make it a practical an operational way to make sure that input and output responses respect the underlying Riemann surface with spin structure is required. This rule is provided by the Fay trisecant identity as it guarantees that if it is satisfied by a theta function then the theta function is associated with a Riemann surface. Thus the dynamical law is implemented by requiring that the theta function, with pinch deformed variables, must satisfy the pinch deformed Fay trisecant identity because then the theta function would continue to be associated with the deformed Riemann surface. The dynamical law also requires that input pinch deformations should be described using the properties of the Riemann surface. These remarks explain how a pinch deformation of a Riemann surface produce responses that are Riemann theta functions with deformed variables that satisfy the pinch deformed Fay trisecant identity.

The final step in this chain came from Mumford’s [

11] discovery that under pinch deformations the non-linear algebraic Fay identity becomes a one dimensional non-linear differential equation and that these solutions were multi-soliton solutions of the non-linear differential equation given by Riemann theta functions with pinch deformed variables. Thus we have the remarkable result that pinch deformations produce soliton signals that carry pinch deformation details with them.

In our case we would like the pinch deformed Fay identity to lead to the one dimensional non-linear Schroedinger equation. This is possible if the Riemann surface represents a hyperelliptic equation. The reason for this restriction on the nature of the Riemann surface is discussed in Arberello [

10]. It is remarkable that a series of steps has led us to a description of the topological surface connectivity features of the brain by a special Riemann surface defined by a specific algebraic equation.

2.3.1. Pinch Deformations

We now comment on pinch deformation as this will give us an insight regarding the nature of the deformation of the theta function variables expected that produce soliton solutions. We then display the explicit multi-soliton solution of Previato [

17] to clarify the dependence of signals on theta characteristics.

Pinch deformations corresponds to the reduction of the circumference of a tube of the Riemann surface, at a point, to zero. The dynamical law requires that we should define the pinch deformation using the mathematical structure of the Riemann surface. This is done by using the one forms of the Riemann surface and studying the effect of pinch deformations on integrals of the one form

of the Riemann surface. Consider the integral,

where 0 is a fixed point and

z a variable point on thre Riemann surface. The two points define an arc. We now allow

and also shrink the arc length to zero so that, in the limit, the arc collapses to central point of the Riemann surface tube at

z. This process defines a pinch deformation. Each pinch deformation is defined by a specific set of deformation parameter values that are given by a suitable Taylor expansion of

when

w approaches the centre of the pinched tube [

2].

There is another way to define a pinch deformation when the Riemann surface is defined by a hyperelliptic equation. Pinch deformations modify the variables of the Riemann theta function. Recall a real hyperelliptic equation for a genus

g surface is defined by the equation

, where the roots

are real or occur as conjugate pairs. One forms are

, branch cuts join neighbouring pair of roots and the

loops are contours that go round these branch cuts. In this case a pinch deformation corresponds to two neighbouring roots of the hyperelliptic equation coming together to create double roots and the surface degenerates to genus zero. Thus in this limit we the theta function variables become,

The terms represent windings round cycles but under pinching . This also means that the characteristics are now absent, and represents the double points that result when the genus g surface degenerates to genus zero and . Explicitly when then the two separate roots become . This is a double point. The real coefficients are signal specific pinch deformation parameters. The net result is the summations of the theta function disappear as do the characteristics. Only the characteristics remain.

2.4. Previato’s Solutions

Previato [

17] found one dimensional multi-soliton solutions of the non-linear one dimensional Schroedinger differential equation and showed it could be written down by summing a specific quadratic function of theta characteristics. The signal is multiplied by an overall phase factor

where

W is the spin topology number of the subunit.

W fixes the nature of the subunit while the the nature of the signal depends on the parameter values of the quadratic function. It is signal specific. We have used Prevaito’s two soliton solution to fit an observed two spike excitation [

3]. This fit demonstrates that the mathematical soliton excitations can represent observed brain excitations. Previato’s solution is given by,

where

. The parameter values for

depend on pinch deformation parameters. Note

is a pinch deformed period matrix

. The sum over

is for all values of the

that are either

with

and

. Thus this sum is a sum over a quadratic function of characteristics. The details of the coefficients are given in Previato’s paper [

17].

The important point to note is that the multi-soliton solutions carries an overall spin topology phase

which fixes the size of the signal generating subunit given by the number of terms in the summation formula for

W. The multi-soliton solution involves two sums. There is the sum of terms of an explicit quadratic function of just the one characteristic

,as expected from our discussion of the pinch deformation. This sum is over the genus of the subunit. In the case of Previato the genus was taken to be

g, and there is sum over all allowed characteristic values in the quadratic function of characteristics that defines the nature of the solution. The quadratic function is signal specific. It depends on the values of the pinch deformation parameters.

*. Thus the number of

terms summed over is fixed by the number of terms in

W the sum over characteristics range between

to

.

The key point to note is that our discussion show that all brain-like signals produced by pinch deformations are completely determined by spin characteristics. The spin topology number W fixes the genus of the signal producing subunit and different signals corresponding to different pinch deformation parameter values that define a specific quadratic function of characteristics that defines the signal and there is a sum over all allowed characteristic values. Thus different information carrying signals can be produced for any given value of W but when no signals exist.

We have briefly summarised key features of the topological brain model network relevant for our current discussion. The focus was on the way signals are produced and how they depend on spin characteristics. The TBM provides answers to the list of basic questions posed at the start. These are discussed in Sen [

2,

3]. We now turn to discuss Frobenius’s rules for combining signals.

2.5. Characteristics of Theta Functions

Frobenius found algebraic rules for combining characteristics [

12,

14]. We summarise his results. Frobenius found that there is a set of

g independent characteristics, for a Riemann theta function, called a fundamental system, from which all other characteristics can be constructed and members of the fundamental system obey certain rules of combination.

There are multiple sets of

g fundamental systems possible [

14]. In our discussions we will use the set constructed by Guardia for the hyperelliptic equation. We will now define and state a number of mathematical results without proving them. The details are in Guardia [

13]. We have,

2.6. Fundamental Systems

A characteristic is a set of of numbers, where each entry, can only take one of two values, namely . A characteristics is said to be even/odd depending on whether . Thus the odd or even property of a characteristic is fixed by the spin topology number W.

A fundamental system of characteristics exists in terms of which all other characteristics can be constructed. The fundamental system is a set

with three properties [

13]

are odd characteristics.

are even.

For every triple in S is azygetic

where the function A triple

of characteristics, is azygetic if

, for every pair

, where

and

. The fundamental system defined, has an important property. It consists of essentially independent elements which means that every sum of an even number of them is non-zero. There are many possible fundamental systems [

14].

Suppose a specific set of characteristic values is represented as , where . We next state the key property of the fundamental system that we will use. A fundamental system of characteristics has the property that any sum of of an even number of them, namely for cannot be zero. This is a general result valid for all Riemann surfaces.

For a Riemann surface that represents a hyperelliptic equation the fundamental system was explicitly constructed by Guardoi [

13] as follows: first we define Weierstrass points,

, for the hyperelliptic equation,

. These are points where

. For a genus

g Riemann surface,

is a polynomial of degree

, there are

Weierstrass points. Explicitly we write,

The formal sum of all points,

, where

multiplied, at each zero point by the multiplicity of the corresponding zero, defines a divisor

D which can be given an abelian group structure. We next pick a set

of

g Weierstrass points and introduce the following divisors.

where

and

is the Riemann vector and

means transposing the row vector to a column vector. Then it can be shown that the system

is a fundamental system [

13]. It should be noted that each element of the fundamental system has a unique spin topology number given by the value of

k in

, so that

. All propagating signals must have odd characteristics. They labelled

. Thus

W values for signals are odd numbers. To make this clear we should write

and

, where

, but we will continue to write

as

k.

The order of the divisor, , of the Riemann theta function is , it counts the total number of zeros of the theta function and is called the semicanonincal divisor. There is a canonical divisor, , that represents the zeros of one forms on . The order of .

We have the following mathematical result [

13]

, for the Riemann theta divisor. Hence

, which means that the divisor

D represent terms that are zero

. Such terms are called two torsion elements. But this is precisely the property of characteristics. Thus the abstract geometrical way to study properties of theta characteristics of the Riemann theta function is equivalent to studying the properties of the divisor of the Riemann theta function. This approach shows that the

constructed are two torsion elements and hence characteristics. To show that they form a fundamental set requires proof [

13].

We end this section by stating two important results [

15]. For the two cases

and

, we have,

where

and

denotes the symmetric difference of the two sets

. These imply

and

where

gives the spin topology number of the joint characteristic. Thus for the sum of two different elements of the fundamental system, written symbolically is,

, where

are odd numbers, while when the two elements are the same

. We point out that each element of the fundamental system has an unique spin topology number

.

2.7. The Logical Rules of the Brain

We now have all the results we need to study the brain’s logical system, as reflected in the surface network, and study if the law of excluded middle holds for the brain. von Neumann in his book,"The Computer and the Brain." raised this possibility. He pointed out that just as language is a historical accident, as there is no logical necessity for the existence of a specific language such as Greek or Sanskrit, it is reasonable to assume that logics and mathematics are historical, accidental forms of expression

† They may have essential variants. von Neumann was led to this conclusion by

his discovery that the brain uses less arithmetical and logical depth than a computer. Arithmetic depth

reflects the accuracy of arithmetic operations required to make predictions while logical depth reflects

the number of logical operations required to come to a conclusion. From these observational facts von

Neumann suggested that "Thus logics and mathematics in the central nervous system, when viewed

as languages, must structurally be essentially different from those languages to which our common

experiences refer." We will now show how the logical system of the brain, as reflected in the network,

confirms von Neumann’s conjecture.

We start by clarifying a number of points. The first clarification is that the spin topology number of a given signal defined by an odd characteristic can be directly related to an element of the fundamental system as it is possible to find a unique member of the fundamental system with the required odd value for

W. Thus the rules of combing elements of the fundamental system can be used to define the logical rules followed by the brain since only odd characteristics are possible for signals [

2]. This is the doorway we use to study the logical system of the brain.

The next clarification is that only signals that traverse closed loop pathways have non-zero values of W, since is not zero only if the terms are non-zero. But represents a loop round the while a loop round . Thus only signals that traverse loops and have non-zero values for W can be built out of elements of the fundamental system.

However this restriction on signals is not a serious limitation as only signals that traverse loop pathways lead to long term memory structures [

2] and provide the feed back loops in the biological brain necessary to maintain the equilibrium properties of the body and carry out motor activities. Even the proposition: the grass is green involves a feedback loop between a signal and memory.

The final clarification is that the combination rules for characteristics found by Frobenius are for characteristics of the entire Riemann theta function. Thus to use the rules we must embed the characteristics associated with a subunit in the space of global characteristics of the theta function. The simplest way to do this has already been suggested. It is to map a signal with spin topology number W to a member of the fundamental system with the same value for W. Such a map exists as our summary of the properties of the fundamental system demonstrates. This step is enough to guarantee that all the signals of the network can be generated by using elements of the fundamental system.

The the law of exclude middle can now be stated in terms of combination rule for signals. Let us explain how. If the law of excluded middle holds it would imply that a signal carrying a proposition and its converse should not exist. We have shown that a given proposition can be carried by a signal, as signals carry information, and that such a signal must belong to a particular class of signals defined by W and thus is an element of the fundamental system. This will also be true for the signal that carries the converse proposition. It too will have a W value and will be associated with an element of the fundamental system. Hence a signal that carries both the proposition and its converse will the sum of these two signals and will thus be given by the sum of two elements of the fundamental system. For the law of excluded middle to be valid such a signal should not exist. This means that the sum of two elements of the fundamental system should be zero, producing a system with which means the non existence of a signal.

But Frobenius’s rules tells us that every sum of an even number of elements of the different elements of the fundamental system is non-zero. Hence the law of excluded middle does not hold for the logical system of the brain as reflected in the network model if the two signals belong to different elements of the fundamental system.

But there is still a way to rescue the law of excluded middle. This can happen if the two propositions have the same value for W since two signals carrying two different propositions can have the same spin topology number W, then as we saw in the previous section, their sum would give and the law of excluded middle would be valid. This result has an observational implication: it implies that the two signals must involve the same set of neurons . Once W is fixed it identifies a specific collection of neurons. Recall W fixes a collection of linked loops and these have specific neurons that are junction regions of the surface network. Thus whether the brain’s logic has or does not have the law of excluded middle can be experimentally determined by observing if the proposition signal and its converse involves the same or different neurons or not. Remember that there is only one member of the fundamental class with a given spin topology number.

Observationally it is found that the converse of a given proposition produces signals in which different neurons from those associated with the proposition are involved [

21]. This is found by means of multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) that can distinguish between brain activities for a proposition and its converse. The analysis reveals that the neurons involved for the two cases are different. Thus it follows that the law of excluded middle is absent in the brain’s logical system and confirms von Neumann’s intuition. We end with a quote from the conclusion section of the paper:

"The overall picture emerging from this set of results is largely compatible with the view that sentential negation polarity operates by modulating the neural activation patterns coding for concepts, to an extent that is sufficient to make the processing of affirmative and negative sentences with either an abstract or concrete content distinguishable by means of MVPA. We suggest that the negation polarity modulation occurs in distributed representational semantic networks, through the functional mediation of syntactic and cognitive control systems. [

21]." Thus negative propositions can be observationally distinguished from positive propositions. They do not use the same set of neurons.

2.8. Conclusions

It is remarkable that the logical rules followed by information carrying brain signals can be theoretically analysed by using properties of the TBM network and it is satisfying that observational evidence was used to conclude that the logical system of the brain does not include the law of excluded middle. It is also interesting that there is recent interest in logical systems that do not have the law of excluded middle in Artificial Intelligence [

22]and in addressing foundational questions of quantum mechanics [

23]

Besides the logical rule differences noted, there are very profound differences between the operating system of the brain and a computer. The brain is an autonomous open system that functions in a given environment, has flexible goals, has intents, is driven by it’s interpretation of the meaning of the information it receives and the specific environmental effects operational at any moment of time. The goal of the brain is to ensure survival of a person and help a person meet his needs, as understood by the brain. These aspirational goals are person specific and are likely to depend on many factors that include the environment and the interests, past history and values of the person. Logic ,as known, cannot handle these diverse requirements that often include contradictory input information.

A relevant structural property of the brain is worth memtioning. Our analyis was based on rules of combining elements of the fundamental system of Frobenius. But the elements of the fundamental system for the biological brain are time dependent as the connectivity properties of the brain that define the fundamental system change and evolve with time.

The results established in this paper depend entirely on a non-reductionist global approach to model brain functions in which a surface network is introduced that exactly captures the topological connectivity of the brain and signals are generated by subunits exploiting their topological structure.