Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Optimizing the Environmental Footprint of LLM Inference: A Literature Review

2.1. From Training to Inference: Why the Burden Has Shifted

2.2. Full Stack per Prompt Accounting: Energy, Carbon, Water, and Embodied Impacts

2.3. Measurement Boundaries: Why Scope Transparency Matters

2.4. Real-Time Orchestration: Carbon- and Water-Aware Routing Under SLOs

2.5. Phase-Aware Hardware Scheduling (Prefill vs. Decode)

2.6. Semantic-Level Interventions

2.7. Lifecycle and Circular Economy Strategies

2.8. Toward a Unified, Deployment-Aware Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Functional Unit and System Boundaries

3.2. Impact Accounting

3.3. Time Resolution, Traffic Mix and SLOs

3.4. Decision Variables, objEctive and Constraints

| Algorithm 1 -Scale (daily-coupled MILP; p95 SLOs, replicas, daily binaries) |

|

| Algorithm 2 Aggregation and scope-transparent reporting (post-solve) |

|

3.5. Parameterization from Public Sources

4. Results

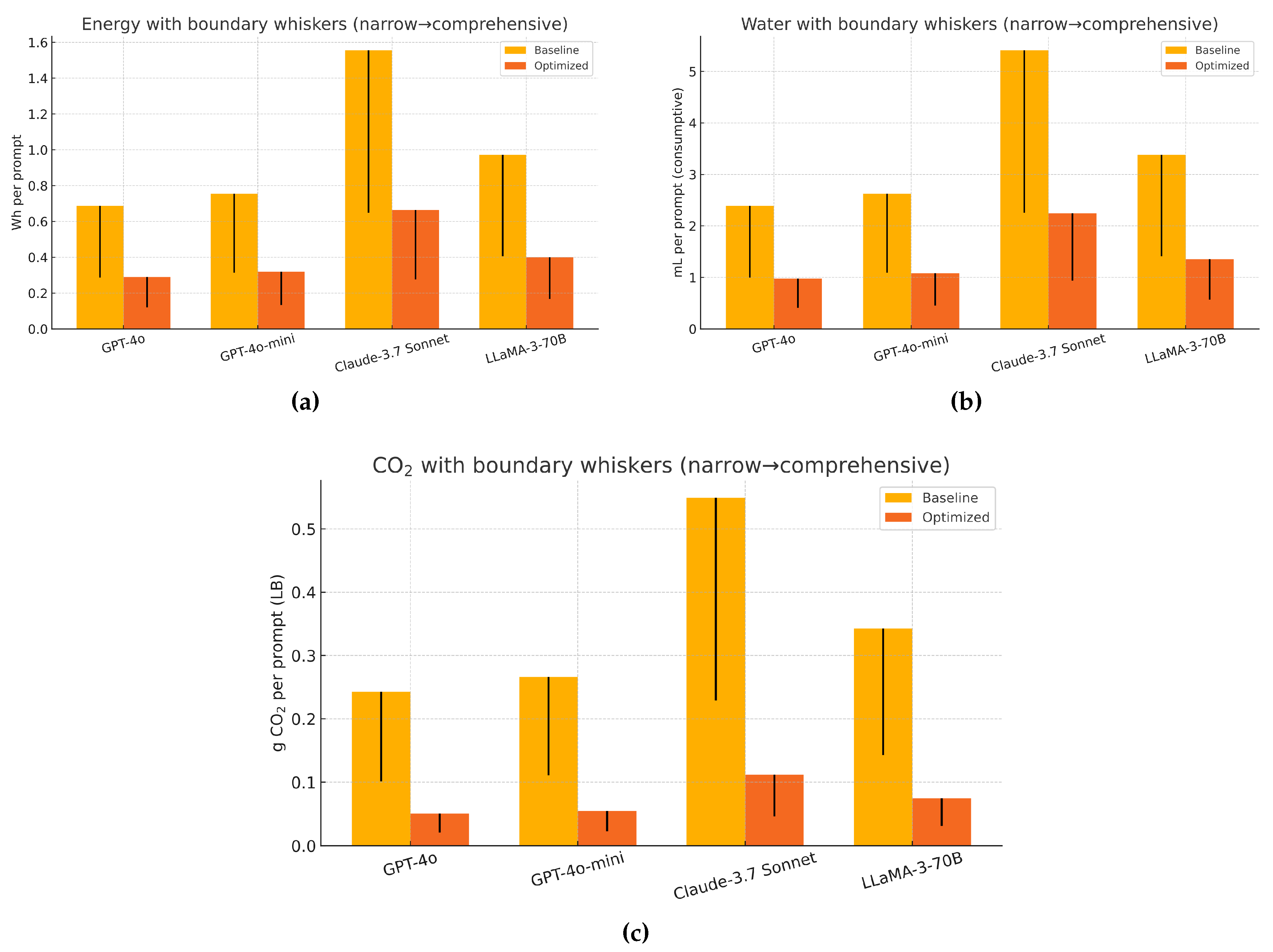

4.1. Comprehensive Boundary Medians and Daily Totals

4.2. Scope Reconciliation: Accelerator-Only vs. Comprehensive

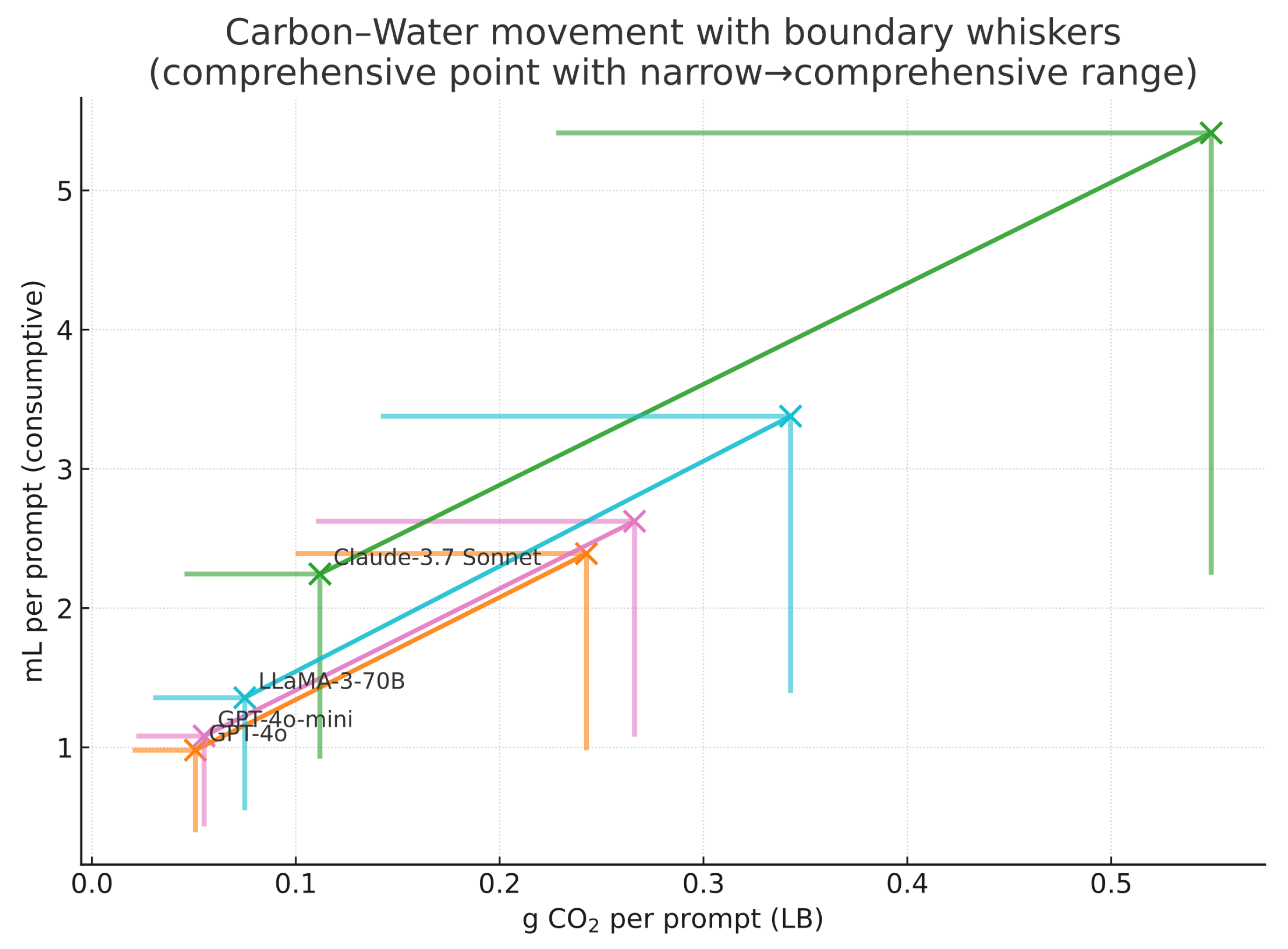

4.3. Carbon–Water Movement at Fixed QoS

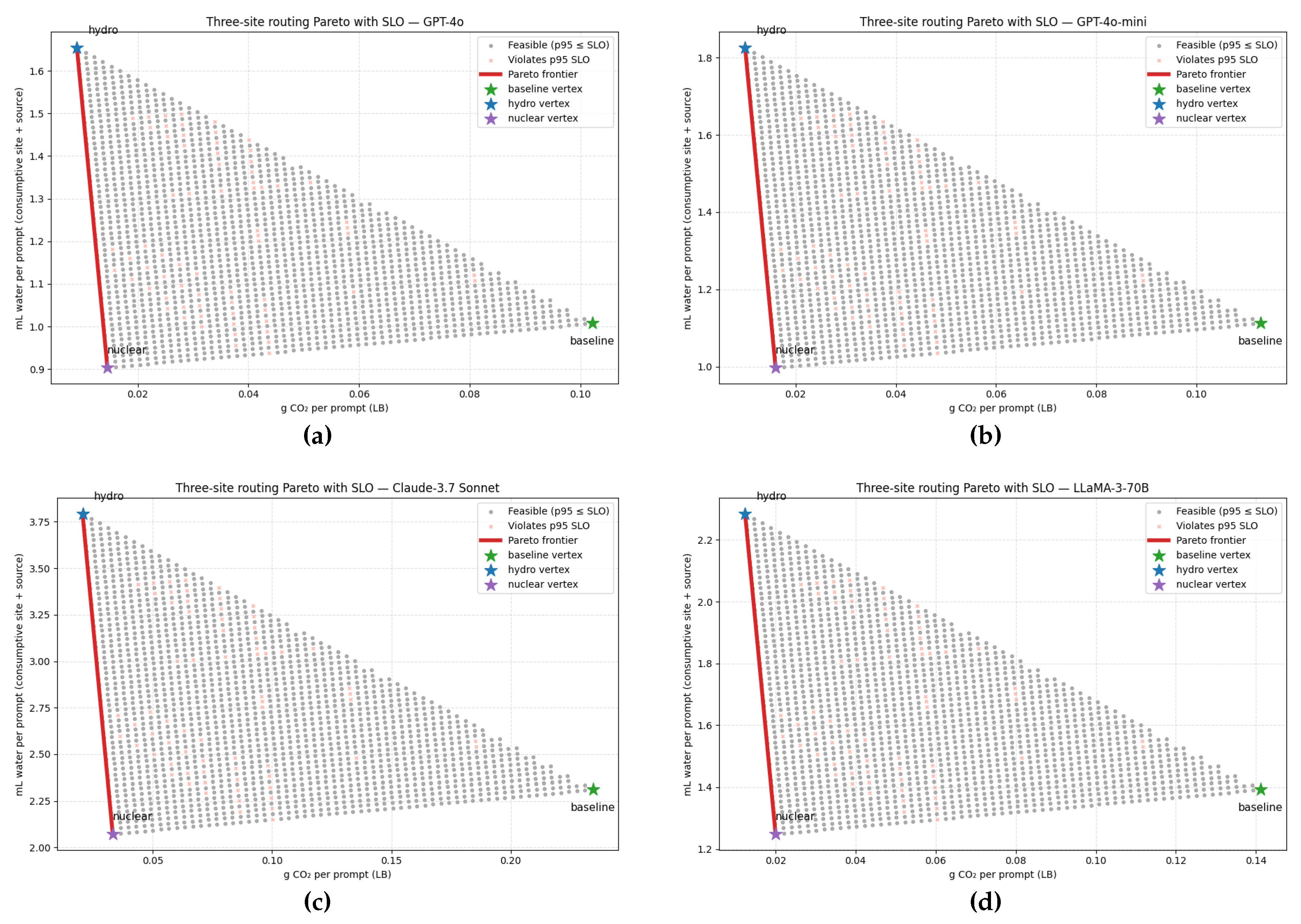

4.4. Routing-Only Carbon–Water Pareto Under SLOs

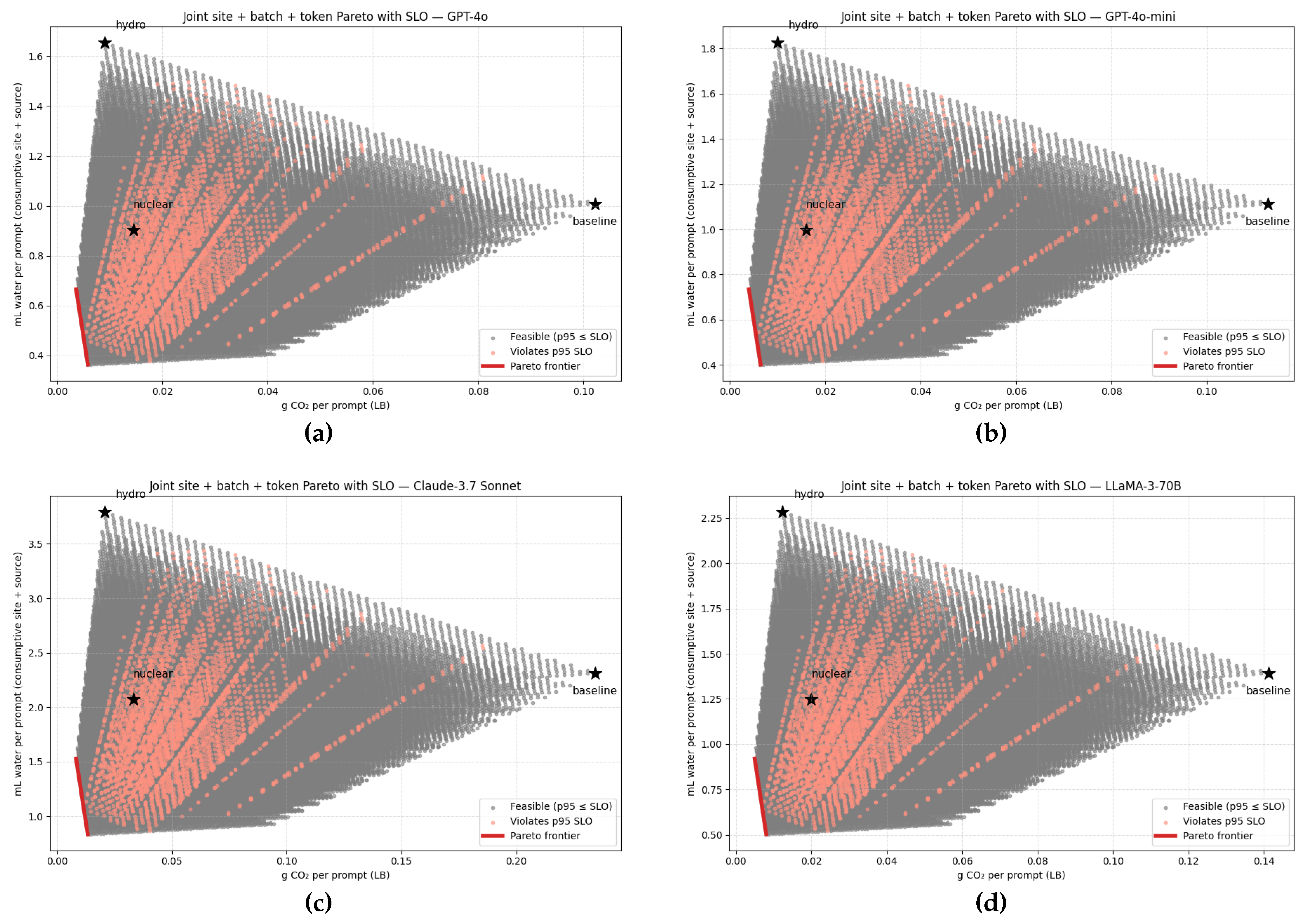

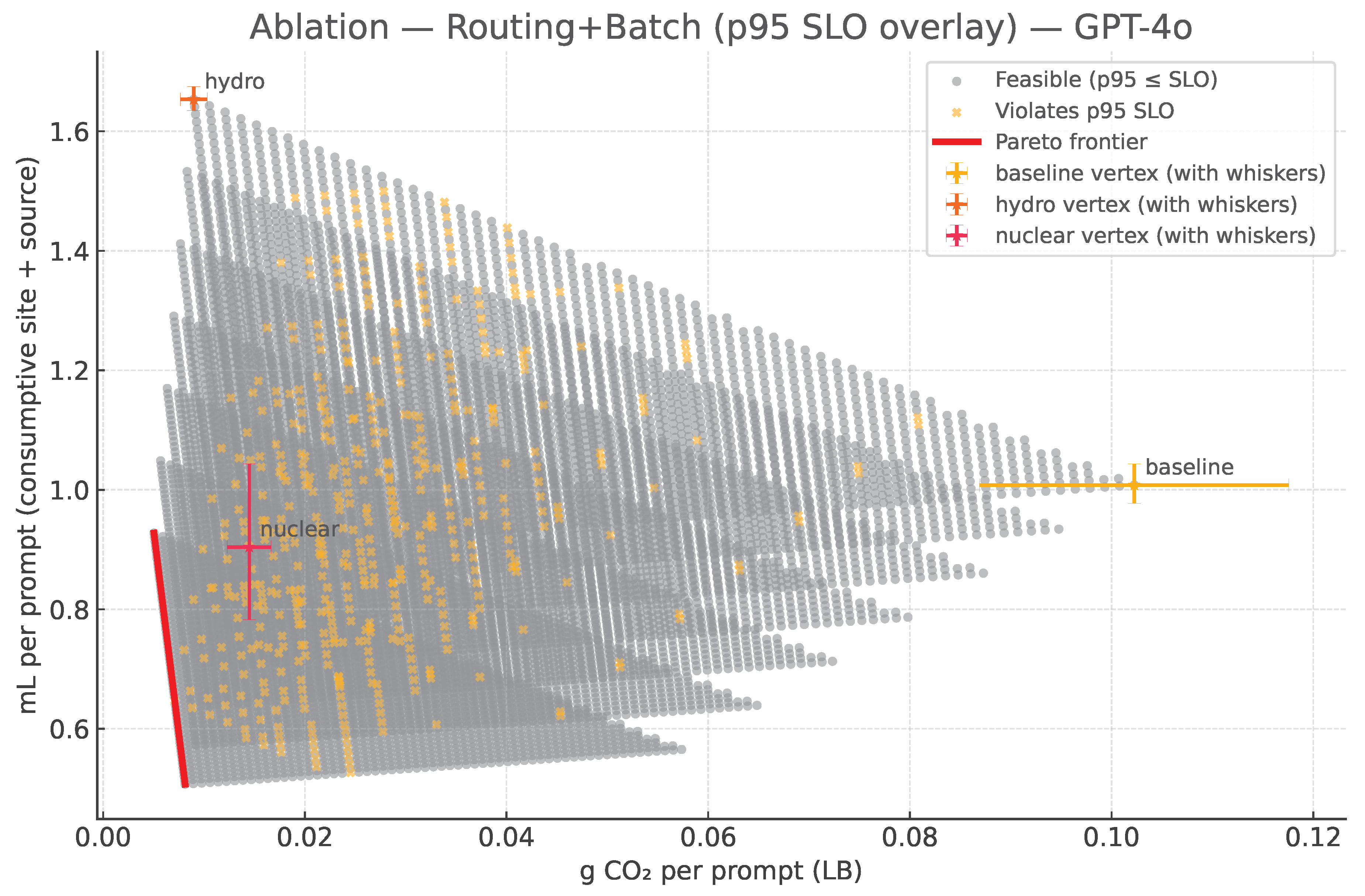

4.5. Joint Frontiers from Site + Batch + Token Sweeps Under the SLO

4.6. Ablation: Where the Gains Come from (Fixed p95 SLOs)

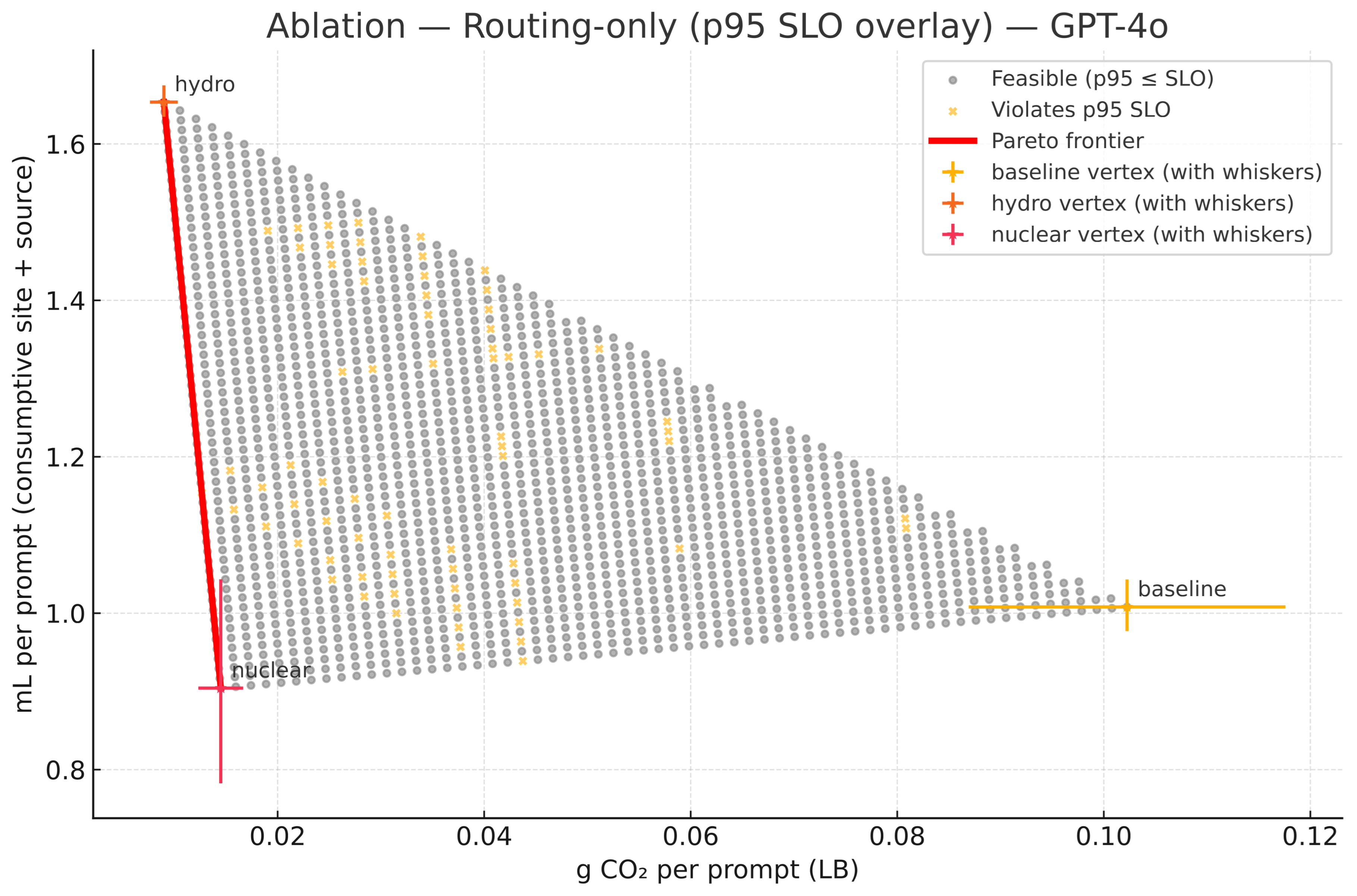

- A1 Routing-only. Holding fixed, let denote the shares across the three representative sites with and . Impacts are affine in s by (17), so the feasible set is the routing simplex and the efficient set is its lower-left envelope. For very low but higher for hydro, the efficient edge collapses to hydro↔nuclear and the baseline vertex is dominated (see Figure 5). Latency feasibility overlays follow the conservative p95 mix proxy in (21).

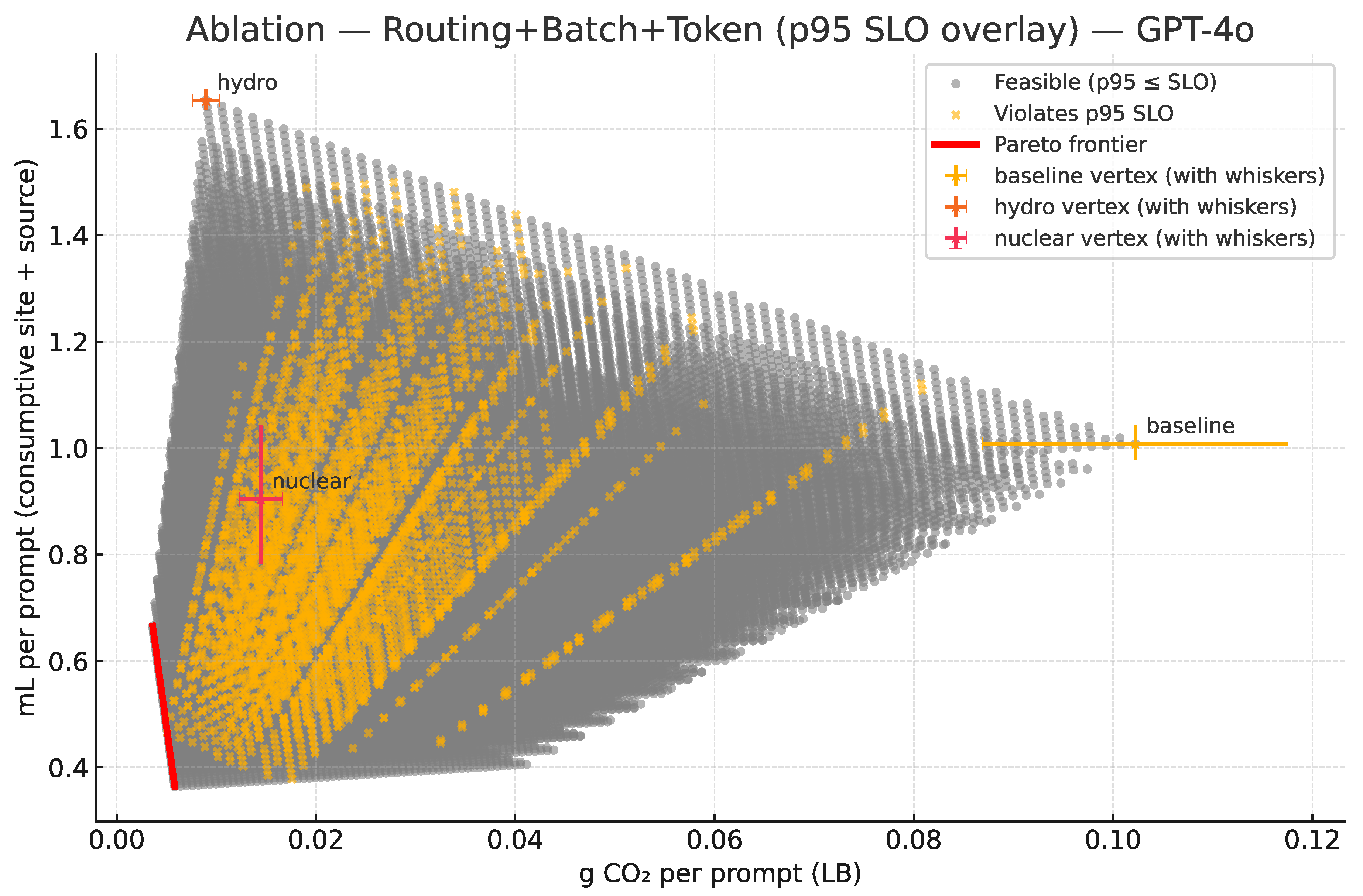

- A3 Routing + Batch + Token (wider wedge). We also sweep a token-length multiplier (default→brief). With , both axes contract by the same factor and the impacts follow the joint form already defined in (21a)–(21b). The feasible cloud thickens and the efficient frontier extends down and left relative to A2 (see Figure 7).

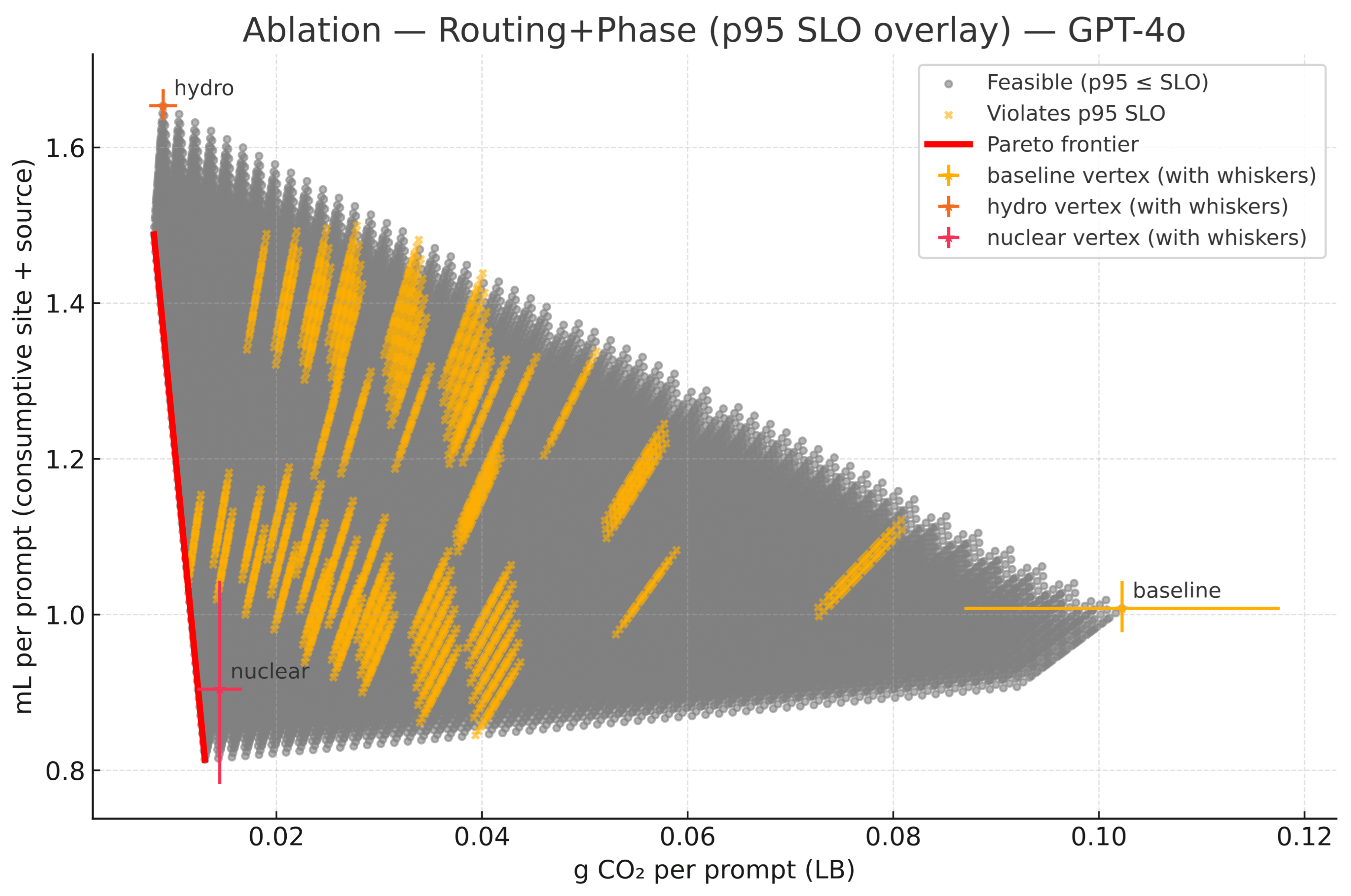

- A4 Routing + Phase split (prefill vs. decode). Using the phase-aware per-token energy models and the prefill and decode constructions in (10)–(11), we expose the energy-shaping effect of placing prefill and decode on different cohorts. For visualization we sweep phase multipliers with decode share and map subject to the same SLO guard. The frontier shifts further toward the origin. The hydro↔nuclear edge remains slope-setting with slope given by (20) (see Figure 8).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence. |

| API | Application Programming Interface (used when referring to cross-model API benchmarks). |

| CIF | Carbon Intensity of the Grid (typically kg CO2 kWh−1); used for location-based emissions. |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide; operational emissions are reported in grams per prompt and in tons per day. |

| CO2e | Carbon-dioxide equivalent (used when referring to greenhouse-gas accounting). |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit (host side of serving stack). |

| DRAM | Dynamic Random-Access Memory (host memory included in comprehensive boundary). |

| Market-Based portfolio emission factor (kg CO2e kWh−1) used as a sensitivity to LB. | |

| EWIF | Electricity–Water Intensity Factor (L kWh−1) capturing off-site, generation-mix water. |

| “Source” component of water from electricity generation in the site+source accounting. | |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas. |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit (accelerator). |

| GWh | Gigawatt-hour ( Wh). |

| IT | Information Technology load (accelerators + host CPU/DRAM + provisioned idle). |

| kWh | Kilowatt-hour ( Wh). |

| KV cache | Key–Value cache (used in decode optimizations). |

| LB | Location-Based (grid-average, point-of-consumption reporting for emissions; the default in this work). |

| LBNL | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (source for PUE/WUE context). |

| LLM | Large Language Model. |

| MB | Market-Based (portfolio accounting sensitivity for emissions). |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Program (optimization formulation). |

| mL | Milliliter ( L). |

| ML | Megaliter ( L); in results tables, ML day−1 is used for daily totals. |

| s | Second. |

| PUE | Power Usage Effectiveness (facility/IT energy ratio). |

| QoS | Quality of Service (used when discussing interactive service constraints). |

| SLO | Service Level Objective (latency/throughput targets enforced in the optimizer). |

| -Scale | The time-resolved, SLO-aware bi-objective orchestration loop proposed in the paper. |

| TPOT | Time Per Output Token (latency metric for decode). |

| TPS | Tokens Per Second (throughput metric used in capacity constraints). |

| TPU | Tensor Processing Unit (accelerator). |

| TTFT | Time To First Token (latency metric for prefill). |

| Wh | Watt-hour (unit for per-prompt energy). |

| WUE | Water Usage Effectiveness (L kWh−1 at the facility; site cooling). |

| Site-level WUE used in the site+source water formulation. | |

| 95th-percentile statistic (used for latency and throughput SLO enforcement). |

References

- Elsworth, C.; Huang, K.; Patterson, D.; Schneider, I.; Sedivy, R.; Goodman, S.; Manyika, J. Measuring the environmental impact of delivering AI at Google Scale, 2025, [arXiv:cs.DC/2508.15734].

- Huang, Y. Advancing industrial sustainability research: A domain-specific large language model perspective. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2025, 27, 1899–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Making AI less “thirsty”: Uncovering and addressing the secret water footprint of AI models, 2023, [2304.03271]. [CrossRef]

- Desislavov, R.; Martínez-Plumed, F.; Hernández-Orallo, J. Trends in AI inference energy consumption: Beyond the performance-vs-parameter laws of deep learning. Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems 2023, 38, 100857. [Google Scholar]

- Jegham, N.; Abdelatti, M.; Elmoubarki, L.; Hendawi, A. How hungry is AI? Benchmarking energy, water, and carbon footprint of LLM inference, 2025, [2505.09598]. [CrossRef]

- Jagannadharao, A.; Beckage, N.; Nafus, D.; Chamberlin, S. Time shifting strategies for carbon-efficient long-running large language model training. Innovations in Systems and Software Engineering 2025, 21, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Mian, A. A comprehensive overview of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2025, 16, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husom, E.J.; Goknil, A.; Shar, L.K.; Sen, S. The price of prompting: Profiling energy use in large language models inference, 2024, [2407.16893]. [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.; Qi, S.; Hogade, N.; Milojicic, D.; Bash, C.; Pasricha, S. Sustainable Carbon-Aware and Water-Efficient LLM Scheduling in Geo-Distributed Cloud Datacenters, 2025, [2505.23554]. [CrossRef]

- Chien, A.A.; Lin, L.; Nguyen, H.; Rao, V.; Sharma, T.; Wijayawardana, R. Reducing the Carbon Impact of Generative AI Inference (today and in 2035). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Sustainable Computer Systems, 2023, pp. 1–7.

- Argerich, M.F.; Patiño-Martínez, M. Measuring and improving the energy efficiency of large language models inference. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 80194–80207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, A. The growing energy footprint of artificial intelligence. Joule 2023, 7, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luccioni, A.S.; Viguier, S.; Ligozat, A.L. Estimating the carbon footprint of BLOOM, a 176B parameter language model. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Roy, R.B.; Kanakagiri, R.; Tiwari, D. WaterWise: Co-optimizing Carbon-and Water-Footprint Toward Environmentally Sustainable Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the PPoPP ’25: 30th ACM SIGPLAN Annual Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming, 2025, pp. 297–311.

- Islam, M.A.; Ren, S.; Quan, G.; Shakir, M.Z.; Vasilakos, A.V. Water-constrained geographic load balancing in data centers. IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing 2015, 5, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, I.; Xu, H.; Benecke, S.; Patterson, D.; Huang, K.; Ranganathan, P.; Elsworth, C. Life-cycle emissions of AI hardware: A cradle-to-grave approach and generational trends, 2025, [2502.01671]. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hua, I.; Ding, Y. Unveiling environmental impacts of large language model serving: A functional unit view, 2025, [2502.11256]. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Wang, Z.; Hu, W.; Yang, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, S. SCOOT: SLO-Oriented Performance Tuning for LLM Inference Engines. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The Web Conference 2025, 2025, pp. 829–839.

- Wu, C.J.; Raghavendra, R.; Gupta, U.; Acun, B.; Ardalani, N.; Maeng, K.; Hazelwood, K.; et al. Sustainable AI: Environmental implications, challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 2022, Vol. 4, pp. 795–813.

- Samsi, S.; Zhao, D.; McDonald, J.; Li, B.; Michaleas, A.; Jones, M.; Gadepally, V.; et al. From words to watts: Benchmarking the energy costs of large language model inference. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC), 2023, pp. 1–9.

- Wiesner, P.; Grinwald, D.; Weiß, P.; Wilhelm, P.; Khalili, R.; Kao, O. Carbon-Aware Quality Adaptation for Energy-Intensive Services. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Future and Sustainable Energy Systems, 2025, pp. 415–422.

- Nguyen, S.; Zhou, B.; Ding, Y.; Liu, S. Towards sustainable large language model serving. ACM SIGENERGY Energy Informatics Review 2024, 4, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, S.; Ekchajzer, D.; Pirson, T.; Lees-Perasso, E.; Wattiez, A.; Biber-Freudenberger, L.; van Wynsberghe, A. More than Carbon: Cradle-to-Grave environmental impacts of GenAI training on the Nvidia A100 GPU, 2025, [2509.00093]. [CrossRef]

- Mistral AI. Our contribution to a global environmental standard for AI. https://mistral.ai/news/ourcontribution-to-a-global-environmental-standard-for-ai, 2025.

- Soares, I.V.; Yarime, M.; Klemun, M.M. Estimating GHG emissions from cloud computing: sources of inaccuracy, opportunities and challenges in location-based and use-based approaches. Climate Policy 2025, pp. 1–19.

- Anquetin, T.; Coqueret, G.; Tavin, B.; Welgryn, L. Scopes of carbon emissions and their impact on green portfolios. Economic Modelling 2022, 115, 105951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różycki, R.; Solarska, D.A.; Waligóra, G. Energy-Aware Machine Learning Models—A Review of Recent Techniques and Perspectives. Energies 2025, 18, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhou, S.; Li, H.; Jiang, L. LLMCO2: Advancing accurate carbon footprint prediction for LLM inferences. ACM SIGENERGY Energy Informatics Review 2025, 5, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraghmeh, H.M.; Wang, C.C. A review of current status of free cooling in datacenters. Applied Thermal Engineering 2017, 114, 1224–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, K.; Jones, G.F.; Fleischer, A.S. A review of data center cooling technology, operating conditions and the corresponding low-grade waste heat recovery opportunities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 31, 622–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytton, D. Data centre water consumption. npj Clean Water 2021, 4.

- Sharma, N.; Mahapatra, S.S. A preliminary analysis of increase in water use with carbon capture and storage for Indian coal-fired power plants. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2018, 9, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlela, S.; Selosse, S. Water use in a sustainable net zero energy system: what are the implications of employing bioenergy with carbon capture and storage? International Journal of Sustainable Energy Planning and Management 2024, 40, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.W.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.J.; Wu, R.; Kweon, O.J.; Xia, Y.; Chowdhury, M.; et al. The ML.ENERGY Benchmark: Toward Automated Inference Energy Measurement and Optimization, 2025, [2505.06371]. [CrossRef]

- Luccioni, S.; Gamazaychikov, B. AI energy score leaderboard. https://huggingface.co/spaces/AIEnergyScore/Leaderboard, 2025.

- Sarkar, S.; Naug, A.; Luna, R.; Guillen, A.; Gundecha, V.; Ghorbanpour, S.; Babu, A.R. Carbon footprint reduction for sustainable data centers in real-time. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 22322–22330-time.

- Mondal, S.; Faruk, F.B.; Rajbongshi, D.; Efaz, M.M.K.; Islam, M.M. GEECO: Green data centers for energy optimization and carbon footprint reduction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepin, I.; Brown, T.; Zavala, V.M. Spatio-temporal load shifting for truly clean computing. Advances in Applied Energy 2025, 17, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Liu, X.; Kong, F. A survey on geographic load balancing based data center power management in the smart grid environment. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2013, 16, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, P.; Behnke, I.; Scheinert, D.; Gontarska, K.; Thamsen, L. Let’s wait awhile: How temporal workload shifting can reduce carbon emissions in the cloud. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd International Middleware Conference, 2021, pp. 260–272.

- Silva, C.A.; Vilaça, R.; Pereira, A.; Bessa, R.J. A review on the decarbonization of high-performance computing centers. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 189, 114019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, A.; Koningstein, R.; Schneider, I.; Chen, B.; Duarte, A.; Roy, B.; Cirne, W. Carbon-aware computing for datacenters. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2022, 38, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, A.; Kaneda, S.; Wang, R.; Osi, R.; Sharma, P.; Chen, F.; Jiang, L. LLMCarbon: Modeling the end-to-end carbon footprint of large language models, 2023, [2309.14393]. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Choukse, E.; Zhang, C.; Shah, A.; Goiri, Í.; Maleki, S.; Bianchini, R. Splitwise: Efficient Generative LLM Inference Using Phase Splitting. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE 51st Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), 2024, pp. 118–132.

- Fan, H.; Lin, Y.C.; Prasanna, V. ELLIE: Energy-Efficient LLM Inference at the Edge Via Prefill-Decode Splitting. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 36th International Conference on Application-specific Systems, Architectures and Processors (ASAP), 2025, pp. 139–146.

- Zhu, K.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zuo, G.; Gu, Y.; Kasikci, B. NanoFlow: Towards Optimal Large Language Model Serving Throughput. In Proceedings of the 19th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 25), 2025, pp. 749–765.

- Zhong, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. DistServe: Disaggregating prefill and decoding for goodput-optimized large language model serving. In Proceedings of the 18th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 24), 2024, pp. 193–210.

- Feng, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liang, S.; Yan, M.; Wu, J. WindServe: Efficient Phase-Disaggregated LLM Serving with Stream-based Dynamic Scheduling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 52nd Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, 2025, pp. 1283–1295.

- Svirschevski, R.; May, A.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Jia, Z.; Ryabinin, M. Specexec: Massively parallel speculative decoding for interactive LLM inference on consumer devices. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 16342–16368. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Liu, J.; Pan, Z.; He, Y.; Haffari, G.; Zhuang, B. MiniCache: KV cache compression in depth dimension for large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 139997–140031. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Roy, R.B.; Li, B.; Tiwari, D. Ecolife: Carbon-aware serverless function scheduling for sustainable computing. In Proceedings of the SC24: International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 2024, pp. 1–15.

- Li, B.; Jiang, Y.; Gadepally, V.; Tiwari, D. SPROUT: Green generative AI with carbon-efficient LLM inference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024, pp. 21799–21813.

- Jiang, P.; Sonne, C.; Li, W.; You, F.; You, S. Preventing the immense increase in the life-cycle energy and carbon footprints of LLM-powered intelligent chatbots. Engineering 2024, 40, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, M.; Znid, F.; Farraj, A. A critical review on improving and moving beyond the 2 nm horizon: Future directions and impacts in next-generation integrated circuit technologies. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2025, 190, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, L.Y.; Tzachor, A.; Chen, W.Q. E-waste challenges of generative artificial intelligence. Nature Computational Science 2024, 4, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehabi, A.; Smith, S.J.; Hubbard, A.; Newkirk, A.; Lei, N.; Siddik, M.A.B.; Holecek, B.; Koomey, J.G.; Masanet, E.; Sartor, D.A. 2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report (LBNL-2001637). Technical report, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yang, J.; Wierman, A.; Ren, S. Towards environmentally equitable AI via geographical load balancing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Future and Sustainable Energy Systems, 2024, pp. 291–307.

- Cao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Hu, H.; Wang, Z.; Wen, Y. Toward a systematic survey for carbon neutral data centers. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2022, 24, 895–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Mahmud, H.; Ren, S.; Wang, X. A carbon-aware incentive mechanism for greening colocation data centers. IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing 2017, 8, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Young, S.; Chen, X.; Gupta, U.; Hester, J. Slower is Greener: Acceptance of Eco-feedback Interventions on Carbon Heavy Internet Services. ACM Journal on Computing and Sustainable Societies 2025, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Tan, H.; Guo, K. Tabi: An efficient multi-level inference system for large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eighteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, 2023, pp. 233–248.

- Ahmadpanah, S.H.; Sobhanloo, S.; Afsharfarnia, P. Dynamic token pruning for LLMs: leveraging task-specific attention and adaptive thresholds. Knowledge and Information Systems 2025, pp. 1–20.

- Belhaouari, S.B.; Kraidia, I. Efficient self-attention with smart pruning for sustainable large language models. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 10171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | GPT 4o | GPT 4o mini | Claude 3.7 Sonnet | LLaMA 3 70B† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Wh/prompt | 0.6876 | 0.7545 | 1.55635 | 0.97145 |

| Optimized Wh/prompt | 0.289824 | 0.319896 | 0.664582 | 0.400321 |

| Energy % | ||||

| Baseline mL/prompt | 2.391473 | 2.624151 | 5.412985 | 3.378703 |

| Optimized mL/prompt | 0.980349 | 1.081547 | 2.245570 | 1.356734 |

| Water % | ||||

| Baseline g CO2/prompt (LB) | 0.242585 | 0.266188 | 0.549080 | 0.342728 |

| Optimized g CO2/prompt (LB) | 0.050739 | 0.055035 | 0.111840 | 0.074971 |

| CO2 % | ||||

| Baseline Energy (GWh/d) | 0.3438 | 0.37725 | 0.778175 | 0.485725 |

| Optimized Energy (GWh/d) | 0.144912 | 0.159948 | 0.332291 | 0.200160 |

| Baseline Water (ML/d) | 1.196 | 1.312 | 2.706 | 1.689 |

| Optimized Water (ML/d) | 0.490 | 0.541 | 1.123 | 0.678 |

| Baseline CO2 (t/d, LB) | 121.293 | 133.094 | 274.540 | 171.364 |

| Optimized CO2 (t/d, LB) | 25.370 | 27.517 | 55.920 | 37.485 |

| Metric | GPT 4o | GPT 4o mini | Claude 3.7 Sonnet | LLaMA 3 70B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Wh/prompt | 0.2865 | 0.314375 | 0.648479 | 0.404771 |

| Comprehensive Wh/prompt | 0.6876 | 0.7545 | 1.55635 | 0.97145 |

| Narrow/Comprehensive | 0.417 | 0.417 | 0.417 | 0.417 |

| Narrow mL/prompt | 0.996447 | 1.093396 | 2.255411 | 1.407793 |

| Comprehensive mL/prompt | 2.391473 | 2.624151 | 5.412985 | 3.378703 |

| Narrow g CO2/prompt (LB) | 0.101077 | 0.110911 | 0.228783 | 0.142803 |

| Comprehensive g CO2/prompt (LB) | 0.242585 | 0.266188 | 0.549080 | 0.342728 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).